Pergamene School on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Pergamon or Pergamum ( or ; ), also referred to by its modern Greek form Pergamos (), was a rich and powerful

MYSIA, Pergamon. Mid 5th century BCE.jpg, Possible coinage of the Greek ruler

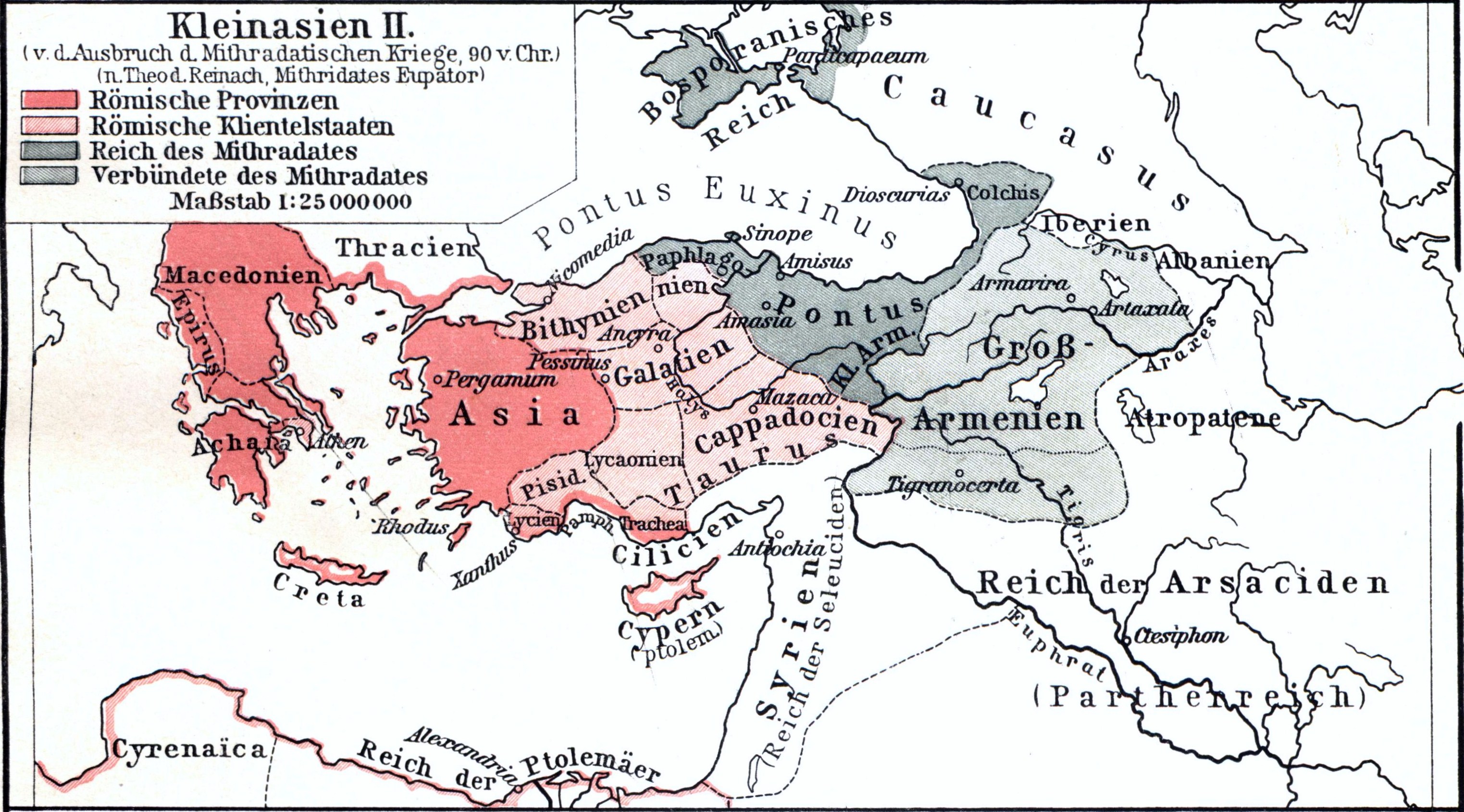

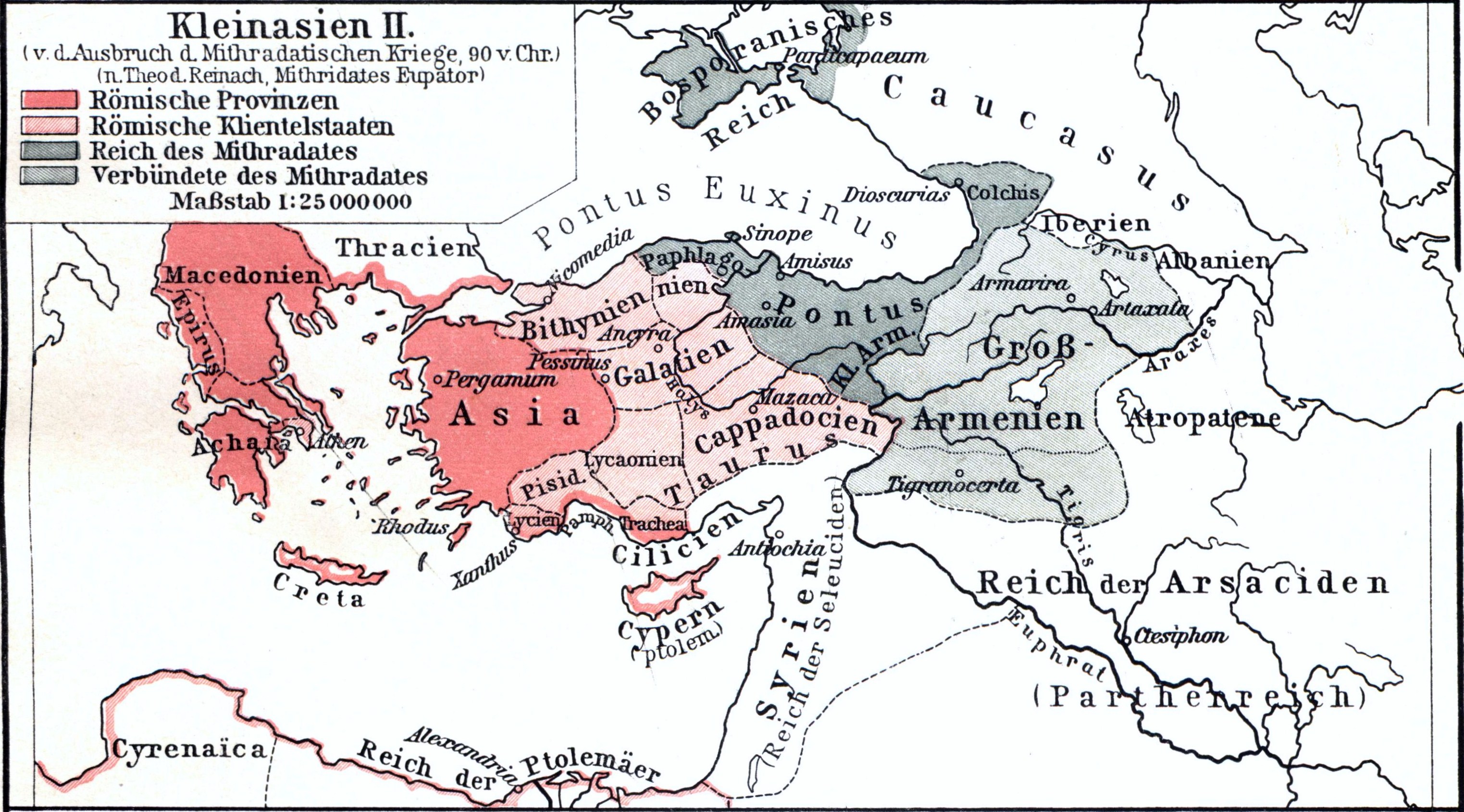

In 88 BC,

In 88 BC,  Yet it was only under

Yet it was only under  In the middle of the 2nd century Pergamon was one of the largest cities in the province, and had around 200,000 inhabitants.

In the middle of the 2nd century Pergamon was one of the largest cities in the province, and had around 200,000 inhabitants.

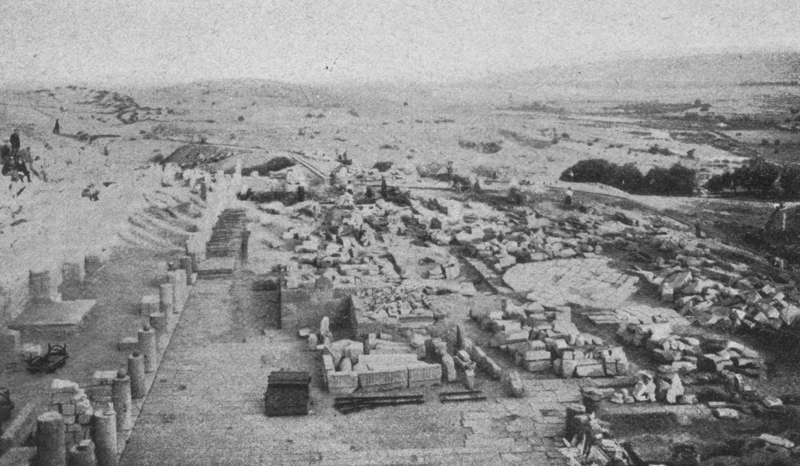

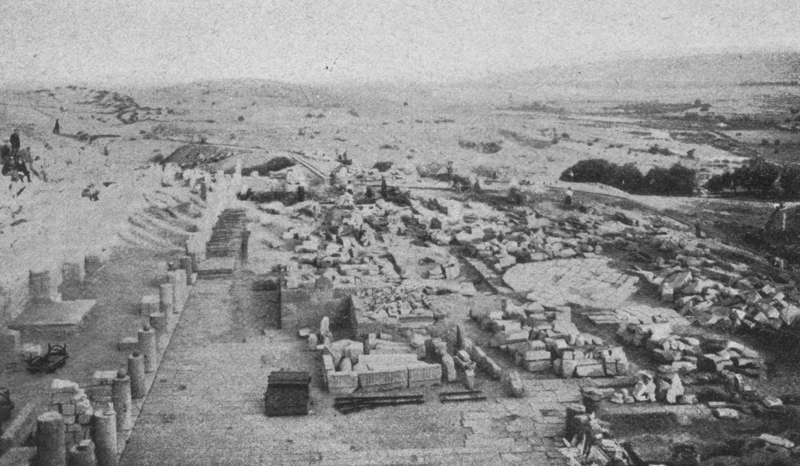

As a result of these efforts, Carl Humann, who had been carrying out low-level excavations at Pergamon for the previous few years and had discovered for example the architrave inscription of the Temple of Demeter in 1875, was entrusted with carry out work in the area of the altar of Zeus in 1878, where he continued to work until 1886. With the approval of the

As a result of these efforts, Carl Humann, who had been carrying out low-level excavations at Pergamon for the previous few years and had discovered for example the architrave inscription of the Temple of Demeter in 1875, was entrusted with carry out work in the area of the altar of Zeus in 1878, where he continued to work until 1886. With the approval of the

The most famous structure from the city is the monumental altar, sometimes called the Great Altar, which was probably dedicated to Zeus and Athena. The foundations are still located in the Upper city, but the remains of the Pergamon frieze, which originally decorated it, are displayed in the Pergamon museum in Berlin, where the parts of the frieze taken to Germany have been installed in a partial reconstruction.

The most famous structure from the city is the monumental altar, sometimes called the Great Altar, which was probably dedicated to Zeus and Athena. The foundations are still located in the Upper city, but the remains of the Pergamon frieze, which originally decorated it, are displayed in the Pergamon museum in Berlin, where the parts of the frieze taken to Germany have been installed in a partial reconstruction.

For the altar's construction, the required flat area was skillfully created through terracing, in order to allow it to be oriented in relation to the neighbouring Temple of Athena. The base of the altar measured around 36 x 33 metres and was decorated on the outside with a detailed depiction in

For the altar's construction, the required flat area was skillfully created through terracing, in order to allow it to be oriented in relation to the neighbouring Temple of Athena. The base of the altar measured around 36 x 33 metres and was decorated on the outside with a detailed depiction in

The well-preserved dates from the Hellenistic period and had space for around 10,000 people, in 78 rows of seats. At a height of 36 metres, it is the steepest of all ancient theatres. The seating area (''koilon'') is divided horizontally by two walkways, called ''diazomata'', and vertically by stairways into seven sections in the lowest part of the theatre and six in the middle and upper sections. Below the theatre is a and up to terrace, which rested on a high retaining wall and was framed on the long side by a

The well-preserved dates from the Hellenistic period and had space for around 10,000 people, in 78 rows of seats. At a height of 36 metres, it is the steepest of all ancient theatres. The seating area (''koilon'') is divided horizontally by two walkways, called ''diazomata'', and vertically by stairways into seven sections in the lowest part of the theatre and six in the middle and upper sections. Below the theatre is a and up to terrace, which rested on a high retaining wall and was framed on the long side by a

On the highest point of the citadel is the Temple of

On the highest point of the citadel is the Temple of

Pergamon's oldest temple is a sanctuary of Athena from the 4th century BC. It was a north-facing Doric

Pergamon's oldest temple is a sanctuary of Athena from the 4th century BC. It was a north-facing Doric

Other notable structures still in existence on the upper part of the Acropolis include:

*The Royal palaces

*The Heroön – a shrine where the kings of Pergamon, particularly Attalus I and Eumenes II, were worshipped.

*The Upper Agora

*The Roman baths complex

*Diodorus Pasporos heroon

*Arsenals

The site is today easily accessible by the

Other notable structures still in existence on the upper part of the Acropolis include:

*The Royal palaces

*The Heroön – a shrine where the kings of Pergamon, particularly Attalus I and Eumenes II, were worshipped.

*The Upper Agora

*The Roman baths complex

*Diodorus Pasporos heroon

*Arsenals

The site is today easily accessible by the

A large gymnasium area was built in the 2nd century BC on the south side of the Acropolis. It consisted of three terraces, with the main entrance at the southeast corner of the lowest terrace. The lowest and southernmost terrace is small and almost free of buildings. It is known as the Lower Gymnasium and has been identified as the boys' gymnasium. The middle terrace was around 250 metres long and 70 metres wide at the centre. On its north side there was a two-story hall. In the east part of the terrace there was a small

A large gymnasium area was built in the 2nd century BC on the south side of the Acropolis. It consisted of three terraces, with the main entrance at the southeast corner of the lowest terrace. The lowest and southernmost terrace is small and almost free of buildings. It is known as the Lower Gymnasium and has been identified as the boys' gymnasium. The middle terrace was around 250 metres long and 70 metres wide at the centre. On its north side there was a two-story hall. In the east part of the terrace there was a small

The sanctuary of Hera Basileia ('the Queen') lay north of the upper terrace of the gymnasium. Its structure sits on two parallel terraces, the south one about 107.4 metres above sea level and the north one about 109.8 metres above sea level. The Temple of Hera sat in the middle of the upper terrace, facing to the south, with a

The sanctuary of Hera Basileia ('the Queen') lay north of the upper terrace of the gymnasium. Its structure sits on two parallel terraces, the south one about 107.4 metres above sea level and the north one about 109.8 metres above sea level. The Temple of Hera sat in the middle of the upper terrace, facing to the south, with a

The Sanctuary of Demeter occupied an area of 50 x 110 metres on the middle level of the south slope of the citadel. The sanctuary was old; its activity can be traced back to the fourth century BC.

The sanctuary was entered through a Propylon from the east, which led to a courtyard surrounded by stoas on three sides. In the centre of the western half of this courtyard, stood the Ionic temple of

The Sanctuary of Demeter occupied an area of 50 x 110 metres on the middle level of the south slope of the citadel. The sanctuary was old; its activity can be traced back to the fourth century BC.

The sanctuary was entered through a Propylon from the east, which led to a courtyard surrounded by stoas on three sides. In the centre of the western half of this courtyard, stood the Ionic temple of

south of the Acropolis (at 39° 7′ 9″ N, 27° 9′ 56″ E), down in the valley, is the Sanctuary of

south of the Acropolis (at 39° 7′ 9″ N, 27° 9′ 56″ E), down in the valley, is the Sanctuary of

Pergamon's other notable structure is the great temple of the Egyptian gods

Pergamon's other notable structure is the great temple of the Egyptian gods

message

sent to the Pergamon Church in the

Philetairos' design of the city was shaped above all by circumstantial considerations. Only under Eumenes II was this approach discarded and the city plan begins to show signs of an overall plan. Contrary to earlier attempts at an orthogonal street system, a fan-shaped design seems to have been adopted for the area around the gymnasium, with streets up to four metres wide, apparently intended to enable effective traffic flow. In contrast to it, Philetairos' system of alleys was created unsystematically, although the topic is still under investigation. Where the lay of the land prevented the laying of a street, small alleys were installed as connections instead. In general, therefore, there are large, broad streets (''plateiai'') and small, narrow connecting streets (''stenopoi'').

The nearly 200 metre wide

Philetairos' design of the city was shaped above all by circumstantial considerations. Only under Eumenes II was this approach discarded and the city plan begins to show signs of an overall plan. Contrary to earlier attempts at an orthogonal street system, a fan-shaped design seems to have been adopted for the area around the gymnasium, with streets up to four metres wide, apparently intended to enable effective traffic flow. In contrast to it, Philetairos' system of alleys was created unsystematically, although the topic is still under investigation. Where the lay of the land prevented the laying of a street, small alleys were installed as connections instead. In general, therefore, there are large, broad streets (''plateiai'') and small, narrow connecting streets (''stenopoi'').

The nearly 200 metre wide

Digitisation

* Volume I 3: Alexander Conze (ed.): ''Stadt und Landschaft''

DigitisationDigitisation of the tables for I, 1–3

* Volume I 4:

Digitisation Digitisation of the tables

* Volume III 1:

DigitisationDigitisation of the tables

* Volume III 2:

DigitisationDigitisation of the tables

* Volume IV: Richard Bohn: ''Die Theater-Terrasse'' he Theatre Terrace(1896

DigitisationDigitisation of the tables

* Volume V 1:

DigitisationDigitisation of the tables

* Volume V 2:

DigitisationDigitisation of the tables

* Volume VI: Paul Schazmann: ''Das Gymnasion. Der Tempelbezirk der Hera Basileia''

DigitisationDigitisation of the tables

* Volume VII 1:

Digitisation

* Volume VII 2: Franz Winter: ''Die Skulpturen mit Ausnahme der Altarreliefs'' he Sculpture, aside from the Altar Reliefs(1908

DigitisationDigitisation of the tables

* Volume VIII 1:

Digitisation

* Volume VIII 2: Max Fränkel (ed.): ''Die Inschriften von Pergamon ''

Digitisation

* Volume VIII 3: Christian Habicht,

Rosa Valderrama, "Pergamum"

brief history

Photographic tour of old and new Pergamon, including the museum

* ttp://www.pergamon.secondpage.de/index_en.html 3D-visualization and photos of Pergamon* {{Authority control Ancient Greek archaeological sites in Turkey Archaeological sites in the Aegean region Buildings and structures in İzmir Province Former populated places in Turkey History of İzmir Province New Testament cities Tourist attractions in İzmir Province Asia (Roman province) Populated places in ancient Aeolis Populated places in ancient Mysia Bergama District Former kingdoms

ancient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

city in Aeolis

Aeolis (; ), or Aeolia (; ), was an area that comprised the west and northwestern region of Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey), mostly along the coast, and also several offshore islands (particularly Lesbos), where the Aeolian Greek city-states w ...

. It is located from the modern coastline of the Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Asia. It is located between the Balkans and Anatolia, and covers an area of some . In the north, the Aegean is connected to the Marmara Sea, which in turn con ...

on a promontory

A promontory is a raised mass of land that projects into a lowland or a body of water (in which case it is a peninsula). Most promontories either are formed from a hard ridge of rock that has resisted the erosive forces that have removed the s ...

on the north side of the river Caicus (modern-day Bakırçay

Bakırçay (, ) is a river in Turkey. It rises in the Gölcük Dağları mountains and debouches into the Gulf of Çandarlı.

In antiquity, the Bakırçay was or formed part of the ''Kaikos'' or ''Caicus'' River which flowed near the city of ...

) and northwest of the modern city of Bergama

Bergama is a municipality and district of İzmir Province, Turkey. Its area is 1,544 km2, and its population is 105,754 (2022). By excluding İzmir's metropolitan area, it is one of the prominent districts of the province in terms of populatio ...

, Turkey.

During the Hellenistic period

In classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Greek history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the death of Cleopatra VII in 30 BC, which was followed by the ascendancy of the R ...

, it became the capital of the Kingdom of Pergamon

The Kingdom of Pergamon, Pergamene Kingdom, or Attalid kingdom was a Greek state during the Hellenistic period that ruled much of the Western part of Asia Minor from its capital city of Pergamon. It was ruled by the Attalid dynasty (; ).

The k ...

in 281–133 BC under the Attalid dynasty, who transformed it into one of the major cultural centres of the Greek world. Many remains of its monuments can still be seen and especially the masterpiece of the Pergamon Altar

The Pergamon Altar () was a monumental construction built during the reign of the Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek King Eumenes II of the Kingdom of Pergamon, Pergamon Empire in the first half of the 2nd century BC on one of the terraces of the ac ...

. Pergamon was the northernmost of the seven churches of Asia

The Seven Churches of Revelation, also known as the Seven Churches of the Apocalypse and the Seven Churches of Asia, are seven churches of early Christianity mentioned in the New Testament Book of Revelation. All of them were located in Asia Min ...

cited in the New Testament

The New Testament (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus, as well as events relating to Christianity in the 1st century, first-century Christianit ...

Book of Revelation

The Book of Revelation, also known as the Book of the Apocalypse or the Apocalypse of John, is the final book of the New Testament, and therefore the final book of the Bible#Christian Bible, Christian Bible. Written in Greek language, Greek, ...

.

The city is centered on a mesa

A mesa is an isolated, flat-topped elevation, ridge, or hill, bounded from all sides by steep escarpments and standing distinctly above a surrounding plain. Mesas consist of flat-lying soft sedimentary rocks, such as shales, capped by a ...

of andesite

Andesite () is a volcanic rock of intermediate composition. In a general sense, it is the intermediate type between silica-poor basalt and silica-rich rhyolite. It is fine-grained (aphanitic) to porphyritic in texture, and is composed predomina ...

, which formed its acropolis

An acropolis was the settlement of an upper part of an ancient Greek city, especially a citadel, and frequently a hill with precipitous sides, mainly chosen for purposes of defense. The term is typically used to refer to the Acropolis of Athens ...

. This mesa falls away sharply on the north, west, and east sides, but three natural terraces on the south side provide a route up to the top. To the west of the acropolis, the Selinus River (modern Bergamaçay) flows through the city, while the Cetius river (modern Kestelçay) passes by to the east.

Pergamon was added to the UNESCO World Heritage

World Heritage Sites are landmarks and areas with legal protection under an international treaty

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between sovereign states and/or international organizations that is governed by int ...

List in 2014.

Location

Pergamon lies on the north edge of the Caicus plain in the historic region ofMysia

Mysia (UK , US or ; ; ; ) was a region in the northwest of ancient Asia Minor (Anatolia, Asian part of modern Turkey). It was located on the south coast of the Sea of Marmara. It was bounded by Bithynia on the east, Phrygia on the southeast, Lyd ...

in the northwest of Turkey. The Caicus river breaks through the surrounding mountains and hills at this point and flows in a wide arc to the southwest. At the foot of the mountain range to the north, between the rivers Selinus and Cetius, there is the massif of Pergamon which rises above sea level. The site is only 26 km from the sea, but the Caicus plain is not open to the sea, since the way is blocked by the Karadağ massif. As a result, the area has a strongly inland character. In Hellenistic times, the town of Elaia at the mouth of the Caicus served as the port of Pergamon. The climate is Mediterranean with a dry period from May to August, as is common along the west coast of Asia Minor.

The Caicus valley is mostly composed of volcanic rock, particularly andesite, and the Pergamon massif is also an intrusive stock

Stocks (also capital stock, or sometimes interchangeably, shares) consist of all the Share (finance), shares by which ownership of a corporation or company is divided. A single share of the stock means fractional ownership of the corporatio ...

of andesite. The massif is about one kilometre wide and around 5.5 km long from north to south. It consists of a broad, elongated base and a relatively small peak - the upper city. The side facing the Cetius river is a sharp cliff, while the side facing the Selinus is a little rough. On the north side, the rock forms a wide spur of rock. To the southeast of this spur, which is known as the 'Garden of the Queen', the massif reaches its greatest height and breaks off suddenly immediately to the east. The upper city extends for another to the south, but it remains very narrow, with a width of only . At its south end the massif falls gradually to the east and south, widening to around and then descends to the plain towards the southwest.

History

Pre-Hellenistic period

Earlier habitation in theBronze Age

The Bronze Age () was a historical period characterised principally by the use of bronze tools and the development of complex urban societies, as well as the adoption of writing in some areas. The Bronze Age is the middle principal period of ...

cannot be demonstrated, although Bronze Age stone tool

Stone tools have been used throughout human history but are most closely associated with prehistoric cultures and in particular those of the Stone Age. Stone tools may be made of either ground stone or knapped stone, the latter fashioned by a ...

s are found in the surrounding area.

Settlement of Pergamon can be detected as far back as the Archaic period, thanks to modest archaeological finds, especially fragments of pottery imported from the west, particularly eastern Greece and Corinth

Corinth ( ; , ) is a municipality in Corinthia in Greece. The successor to the ancient Corinth, ancient city of Corinth, it is a former municipality in Corinthia, Peloponnese (region), Peloponnese, which is located in south-central Greece. Sin ...

, which date to the late 8th century BC.

The earliest mention of Pergamon in literary sources comes from Xenophon

Xenophon of Athens (; ; 355/354 BC) was a Greek military leader, philosopher, and historian. At the age of 30, he was elected as one of the leaders of the retreating Ancient Greek mercenaries, Greek mercenaries, the Ten Thousand, who had been ...

's ''Anabasis

Anabasis (from Greek ''ana'' = "upward", ''bainein'' = "to step or march") is an expedition from a coastline into the interior of a country. Anabase and Anabasis may also refer to:

History

* '' Anabasis Alexandri'' (''Anabasis of Alexander''), ...

'', since the march of the Ten Thousand

The Ten Thousand (, ''hoi Myrioi'') were a force of mercenary units, mainly Greeks, employed by Cyrus the Younger to attempt to wrest the throne of the Persian Empire from his brother, Artaxerxes II. Their march to the Battle of Cunaxa and bac ...

under Xenophon's command ended at Pergamon in 400/399 BC. Xenophon, who calls the city Pergamos, handed over the rest of his Greek troops (some 5,000 men according to Diodorus

Diodorus Siculus or Diodorus of Sicily (; 1st century BC) was an ancient Greek historian from Sicily. He is known for writing the monumental universal history '' Bibliotheca historica'', in forty books, fifteen of which survive intact, b ...

) to Thibron, who was planning an expedition against the Persian satrap

A satrap () was a governor of the provinces of the ancient Median kingdom, Median and Achaemenid Empire, Persian (Achaemenid) Empires and in several of their successors, such as in the Sasanian Empire and the Hellenistic period, Hellenistic empi ...

s Tissaphernes

Tissaphernes (; ; , ; 445395 BC) was a Persian commander and statesman, Satrap of Lydia and Ionia. His life is mostly known from the works of Thucydides and Xenophon. According to Ctesias, he was the son of Hidarnes III and therefore, the gre ...

and Pharnabazus, at this location in March 399 BC. At this time Pergamon was in the possession of the family of Gongylos

Gongylos (), from Eretria in Euboea, was a 5th-century BCE (9500s HE) Greek statesman who served as an intermediary between the Spartans and Xerxes I of the Achaemenid Empire, and was a supporter of the latter.

After the defeat of the Second ...

from Eretria

Eretria (; , , , , literally 'city of the rowers') is a town in Euboea, Greece, facing the coast of Attica across the narrow South Euboean Gulf. It was an important Greek polis in the 6th and 5th century BC, mentioned by many famous writers ...

, a Greek favourable to the Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire, also known as the Persian Empire or First Persian Empire (; , , ), was an Iranian peoples, Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great of the Achaemenid dynasty in 550 BC. Based in modern-day Iran, i ...

who had taken refuge in Asia Minor and obtained the territory of Pergamon from Xerxes I

Xerxes I ( – August 465 BC), commonly known as Xerxes the Great, was a List of monarchs of Persia, Persian ruler who served as the fourth King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, reigning from 486 BC until his assassination in 465 BC. He was ...

, and Xenophon was hosted by his widow Hellas.

In 362 BC, Orontes, satrap of Mysia, used Pergamon as his base for an unsuccessful revolt against the Persian Empire. Only with Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon (; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), most commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip ...

were Pergamon and the surrounding area removed from Persian control. There are few traces of the pre-Hellenistic city, since in the following period the terrain was profoundly changed and the construction of broad terraces involved the removal of almost all earlier structures. Parts of the temple of Athena

Athena or Athene, often given the epithet Pallas, is an ancient Greek religion, ancient Greek goddess associated with wisdom, warfare, and handicraft who was later syncretism, syncretized with the Roman goddess Minerva. Athena was regarde ...

, as well as the walls and foundations of the altar in the sanctuary of Demeter

In ancient Greek religion and Greek mythology, mythology, Demeter (; Attic Greek, Attic: ''Dēmḗtēr'' ; Doric Greek, Doric: ''Dāmā́tēr'') is the Twelve Olympians, Olympian goddess of the harvest and agriculture, presiding over cro ...

, go back to the fourth century.

Gongylos

Gongylos (), from Eretria in Euboea, was a 5th-century BCE (9500s HE) Greek statesman who served as an intermediary between the Spartans and Xerxes I of the Achaemenid Empire, and was a supporter of the latter.

After the defeat of the Second ...

, wearing the Persian cap on the reverse, as ruler of Pergamon for the Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire, also known as the Persian Empire or First Persian Empire (; , , ), was an Iranian peoples, Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great of the Achaemenid dynasty in 550 BC. Based in modern-day Iran, i ...

. Pergamon, Mysia

Mysia (UK , US or ; ; ; ) was a region in the northwest of ancient Asia Minor (Anatolia, Asian part of modern Turkey). It was located on the south coast of the Sea of Marmara. It was bounded by Bithynia on the east, Phrygia on the southeast, Lyd ...

, circa 450 BC. The name of the city ΠΕΡΓ ("PERG"), appears for the first on this coinage, and is the first evidence for the name of the city.

MYSIA, Adramyteion. Orontes, Satrap of Mysia. Circa 357-352 BC.jpg, Coin of Orontes, Achaemenid Satrap of Mysia

Mysia (UK , US or ; ; ; ) was a region in the northwest of ancient Asia Minor (Anatolia, Asian part of modern Turkey). It was located on the south coast of the Sea of Marmara. It was bounded by Bithynia on the east, Phrygia on the southeast, Lyd ...

(including Pergamon), Adramyteion. Circa 357-352 BC

Hellenistic period

Lysimachus

Lysimachus (; Greek language, Greek: Λυσίμαχος, ''Lysimachos''; c. 360 BC – 281 BC) was a Thessaly, Thessalian officer and Diadochi, successor of Alexander the Great, who in 306 BC, became king of Thrace, Anatolia, Asia Minor and Mace ...

, King of Thrace

Thrace (, ; ; ; ) is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe roughly corresponding to the province of Thrace in the Roman Empire. Bounded by the Balkan Mountains to the north, the Aegean Sea to the south, and the Black Se ...

, took possession in 301 BC, and the town was enlarged by his lieutenant Philetaerus

Philetaerus (; , ''Philétairos'', c. 343 –263 BC) was the founder of the Attalid dynasty of Pergamon in Anatolia.

Early life and career under Lysimachus

Philetaerus was born in Tieium (Greek: ''Tieion''), a small town on the Black Sea co ...

. In 281 BC the kingdom of Thrace collapsed and Philetaerus became an independent ruler, founding the Attalid dynasty

The Kingdom of Pergamon, Pergamene Kingdom, or Attalid kingdom was a Greek state during the Hellenistic period that ruled much of the Western part of Asia Minor from its capital city of Pergamon. It was ruled by the Attalid dynasty (; ).

The ...

. His family ruled Pergamon from 281 until 133 BC: Philetaerus 281–263; Eumenes I

Eumenes I () was dynast (ruler) of the city of Pergamon in Asia Minor from 263 BC until his death in 241 BC. He was the son of Eumenes, the brother of Philetaerus, the founder of the Attalid dynasty, and Satyra, daughter of Poseidonius. As he h ...

263–241; Attalus I

Attalus I ( ), surnamed ''Soter'' (, ; 269–197 BC), was the ruler of the Greek polis of Pergamon (modern-day Bergama, Turkey) and the larger Pergamene Kingdom from 241 BC to 197 BC. He was the adopted son of King Eumenes I ...

241–197; Eumenes II

Eumenes II Soter (; ; ruled 197–159 BC) was a ruler of Pergamon, and a son of Attalus I Soter and queen Apollonis and a member of the Attalid dynasty of Pergamon.

Biography

The eldest son of king Attalus I and queen Apollonis, Eumenes was pr ...

197–159; Attalus II

Attalus II Philadelphus (Greek: Ἄτταλος ὁ Φιλάδελφος, ''Attalos II Philadelphos'', which means "Attalus the brother-loving"; 220–138 BC) was a ruler of the Attalid kingdom of Pergamon and the founder of the city of Att ...

159–138; and Attalus III

Attalus III () Philometor Euergetes ( – 133 BC) was the last Attalid king of Pergamon, ruling from 138 BC to 133 BC.

Biography

Attalus III was the son of king Eumenes II and his queen Stratonice of Pergamon, and he was the nephew of A ...

138–133. Philetaerus controlled only Pergamon and its immediate environs, but the city acquired much new territory under Eumenes I. In particular, after the Battle of Sardis

Sardis ( ) or Sardes ( ; Lydian language, Lydian: , romanized: ; ; ) was an ancient city best known as the capital of the Lydian Empire. After the fall of the Lydian Empire, it became the capital of the Achaemenid Empire, Persian Lydia (satrapy) ...

in 261 BC against Antiochus I

Antiochus I Soter (, ''Antíochos Sōtér''; "Antiochus the Savior"; 2 June 261 BC) was a Greek king of the Seleucid Empire. Antiochus succeeded his father Seleucus I Nicator in 281 BC and reigned during a period of instability which he mostly ...

, Eumenes was able to appropriate the area down to the coast and some way inland. Despite this increase of his domain, Eumenes did not take a royal title. In 238 his successor Attalus I defeated the Galatians Galatians may refer to:

* Galatians (people)

* Epistle to the Galatians, a book of the New Testament

* English translation of the Greek ''Galatai'' or Latin ''Galatae'', ''Galli,'' or ''Gallograeci'' to refer to either the Galatians or the Gauls in ...

, to whom Pergamon had paid tribute under Eumenes I. Attalus thereafter declared himself leader of an entirely independent Pergamene kingdom.

The Attalids became some of the most loyal supporters of Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

in the Hellenistic world. Attalus I allied with Rome against Philip V of Macedon

Philip V (; 238–179 BC) was king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedon from 221 to 179 BC. Philip's reign was principally marked by the Social War (220–217 BC), Social War in Greece (220-217 BC) ...

, during the first

First most commonly refers to:

* First, the ordinal form of the number 1

First or 1st may also refer to:

Acronyms

* Faint Images of the Radio Sky at Twenty-Centimeters, an astronomical survey carried out by the Very Large Array

* Far Infrared a ...

and second

The second (symbol: s) is a unit of time derived from the division of the day first into 24 hours, then to 60 minutes, and finally to 60 seconds each (24 × 60 × 60 = 86400). The current and formal definition in the International System of U ...

Macedonian Wars

The Macedonian Wars (214–148 BC) were a series of conflicts fought by the Roman Republic and its Greek allies in the eastern Mediterranean against several different major Greek kingdoms. They resulted in Roman control or influence over Ancient ...

. In the Roman–Seleucid War

The Roman–Seleucid war (192–188 BC), also called the Aetolian war, Antiochene war, Syrian war, and Syrian-Aetolian war was a military conflict between two coalitions, one led by the Roman Republic and the other led by the Seleucid Empi ...

, Pergamon joined the Romans' coalition against Antiochus III

Antiochus III the Great (; , ; 3 July 187 BC) was the sixth ruler of the Seleucid Empire, reigning from 223 to 187 BC. He ruled over the region of Syria and large parts of the rest of West Asia towards the end of the 3rd century BC. Rising to th ...

, and was rewarded with almost all the former Seleucid

The Seleucid Empire ( ) was a Greek state in West Asia during the Hellenistic period. It was founded in 312 BC by the Macedonian general Seleucus I Nicator, following the division of the Macedonian Empire founded by Alexander the Great, a ...

domains in Asia Minor

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

at the Peace of Apamea

The Treaty of Apamea was a peace treaty conducted in 188 BC between the Roman Republic and Antiochus III, ruler of the Seleucid Empire. It ended the Roman–Seleucid War. The treaty took place after Roman victories at the Battle of Thermopylae ( ...

in 188 BC. The kingdom's territories thus reached their greatest extent. Eumenes II supported Rome again in the Third Macedonian War

The Third Macedonian War (171–168 BC) was a war fought between the Roman Republic and King Perseus of Macedon. In 179 BC, King Philip V of Macedon died and was succeeded by his ambitious son Perseus. He was anti-Roman and stirred anti-Roman fe ...

, but the Romans heard rumours of his conducting secret negotiations with their opponent Perseus of Macedon

Perseus (; – 166 BC) was king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedon from 179 until 168BC. He is widely regarded as the last List of kings of Macedonia, king of Macedonia and the last ruler from th ...

. On this basis, Rome denied any reward to Pergamon and attempted to replace Eumenes with the future Attalus II, who refused to cooperate. These incidents cost Pergamon its privileged status with the Romans, who granted it no further territory.

Nevertheless, under the brothers Eumenes II and Attalus II, Pergamon reached its apex and was rebuilt on a monumental scale. It had retained the same dimensions for a long interval after its founding by Philetaerus, covering c. . After 188 BC a massive new city wall was constructed, long and enclosing an area of approximately . The Attalids' goal was to create a second Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

, a cultural and artistic hub of the Greek world. They remodeled their Acropolis after the Acropolis

An acropolis was the settlement of an upper part of an ancient Greek city, especially a citadel, and frequently a hill with precipitous sides, mainly chosen for purposes of defense. The term is typically used to refer to the Acropolis of Athens ...

in Athens, and the Library of Pergamon was renowned as second only to the Library of Alexandria

The Great Library of Alexandria in Alexandria, Egypt, was one of the largest and most significant libraries of the ancient world. The library was part of a larger research institution called the Mouseion, which was dedicated to the Muses, ...

. Pergamon was also a flourishing center for the production of parchment

Parchment is a writing material made from specially prepared Tanning (leather), untanned skins of animals—primarily sheep, calves and goats. It has been used as a writing medium in West Asia and Europe for more than two millennia. By AD 400 ...

, whose name is a corruption of ''pergamenos'', meaning "from Pergamon". Despite this etymology, parchment had been used in Asia Minor long before the rise of the city; the story that it was invented by the Pergamenes, to circumvent the Ptolemies

The Ptolemaic dynasty (; , ''Ptolemaioi''), also known as the Lagid dynasty (, ''Lagidai''; after Ptolemy I's father, Lagus), was a Macedonian Greek royal house which ruled the Ptolemaic Kingdom in Ancient Egypt during the Hellenistic period. ...

' monopoly on papyrus

Papyrus ( ) is a material similar to thick paper that was used in ancient times as a writing surface. It was made from the pith of the papyrus plant, ''Cyperus papyrus'', a wetland sedge. ''Papyrus'' (plural: ''papyri'' or ''papyruses'') can a ...

production, is not true. In fact, parchment had been in use in Anatolia and elsewhere long before the rise of Pergamon.

Surviving epigraphic documents show how the Attalids supported the growth of towns by sending in skilled artisans and by remitting taxes. They allowed the Greek cities in their domains to maintain nominal independence, and sent gifts to Greek cultural sites like Delphi

Delphi (; ), in legend previously called Pytho (Πυθώ), was an ancient sacred precinct and the seat of Pythia, the major oracle who was consulted about important decisions throughout the ancient Classical antiquity, classical world. The A ...

, Delos

Delos (; ; ''Dêlos'', ''Dâlos''), is a small Greek island near Mykonos, close to the centre of the Cyclades archipelago. Though only in area, it is one of the most important mythological, historical, and archaeological sites in Greece. ...

, and Athens. The two brothers Eumenes II and Attalus II displayed the most distinctive trait of the Attalids: a pronounced sense of family without rivalry or intrigue - rare amongst the Hellenistic dynasties. Attalus II bore the epithet 'Philadelphos', 'he who loves his brother', and his relations with Eumenes II were compared to the harmony between the mythical brothers Cleobis and Biton

Kleobis (Cleobis) and Biton (Ancient Greek language, Ancient Greek: , gen.: ; , gen.: ) are two Archaic Greek Kouros brothers from Ancient Argos, Argos, whose stories date back to about 580 BCE. Two statues, discovered in Delphi, represent th ...

.

When Attalus III died without an heir in 133 BC, he bequeathed the whole of Pergamon to Rome. This was challenged by Aristonicus, who claimed to be Attalus III's brother and led an armed uprising against the Romans with the help of Blossius

Gaius Blossius (; 2nd century BC) was, according to Plutarch, a philosopher and student of the Stoic philosopher Antipater of Tarsus, from the city of Cumae in Campania, Italy, who (along with the Greek rhetorician, Diophanes) instigated Roman tr ...

, a famous Stoic philosopher. For a period he enjoyed success, defeating and killing the Roman consul P. Licinius Crassus and his army, but he was defeated in 129 BC by the consul M. Perperna. The Attalid kingdom was divided between Rome, Pontus

Pontus or Pontos may refer to:

* Short Latin name for the Pontus Euxinus, the Greek name for the Black Sea (aka the Euxine sea)

* Pontus (mythology), a sea god in Greek mythology

* Pontus (region), on the southern coast of the Black Sea, in modern ...

, and Cappadocia

Cappadocia (; , from ) is a historical region in Central Anatolia region, Turkey. It is largely in the provinces of Nevşehir, Kayseri, Aksaray, Kırşehir, Sivas and Niğde. Today, the touristic Cappadocia Region is located in Nevşehir ...

, with the bulk of its territory becoming the new Roman province

The Roman provinces (, pl. ) were the administrative regions of Ancient Rome outside Roman Italy that were controlled by the Romans under the Roman Republic and later the Roman Empire. Each province was ruled by a Roman appointed as Roman g ...

of Asia

Asia ( , ) is the largest continent in the world by both land area and population. It covers an area of more than 44 million square kilometres, about 30% of Earth's total land area and 8% of Earth's total surface area. The continent, which ...

. The city itself was declared free and served briefly as capital of the province, before this distinction was transferred to Ephesus

Ephesus (; ; ; may ultimately derive from ) was an Ancient Greece, ancient Greek city on the coast of Ionia, in present-day Selçuk in İzmir Province, Turkey. It was built in the 10th century BC on the site of Apasa, the former Arzawan capital ...

.

Roman period

In 88 BC,

In 88 BC, Mithridates VI Eupator

Mithridates or Mithradates VI Eupator (; 135–63 BC) was the ruler of the Kingdom of Pontus in northern Anatolia from 120 to 63 BC, and one of the Roman Republic's most formidable and determined opponents. He was an effective, ambitious, and ...

made Pergamon his headquarters in his first war against Rome, in which he was defeated. The victorious Romans deprived Pergamon of all its benefits and of its status as a free city. Henceforth the city was required to pay tribute and accommodate and supply Roman troops, and the property of many of the inhabitants was confiscated. Imported Pergamene goods were among the luxuries enjoyed by Lucullus

Lucius Licinius Lucullus (; 118–57/56 BC) was a Ancient Romans, Roman List of Roman generals, general and Politician, statesman, closely connected with Lucius Cornelius Sulla. In culmination of over 20 years of almost continuous military and ...

. The members of the Pergamene aristocracy, especially Diodorus Pasparus

Diodorus Pasparus (, fl. 85-69 BC), son of Heroides, was the leading statesman and benefactor at Pergamon, in the period of the Mithridatic Wars, when the city's place within the Roman province of Asia was contested. He is known solely from a serie ...

in the 70s BC, used their own possessions to maintain good relationships with Rome, by acting as donors for the development of the city. Numerous honorific inscriptions indicate Pasparus' work and his exceptional position in Pergamon at this time.

Pergamon still remained a famous city, and was the seat of a ''conventus

In Ancient Rome territorial organization, a ''conventus iuridicus'' was the capital city of a subdivision of some provinces (Dalmatia, Hispania, Asia

Asia ( , ) is the largest continent in the world by both land area and population. It c ...

'' (regional assembly). Its neocorate

(), plural (), was a sacral office in Ancient Greece associated with the custody of a temple. Under the Roman Empire, the neocorate became a distinction awarded to cities that had built temples to the emperors or had established cults of members ...

, granted by Augustus

Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian (), was the founder of the Roman Empire, who reigned as the first Roman emperor from 27 BC until his death in A ...

, was the first manifestation of the imperial cult

An imperial cult is a form of state religion in which an emperor or a dynasty of emperors (or rulers of another title) are worshipped as demigods or deities. "Cult (religious practice), Cult" here is used to mean "worship", not in the modern pejor ...

in the province of Asia. Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/24 79), known in English as Pliny the Elder ( ), was a Roman Empire, Roman author, Natural history, naturalist, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the Roman emperor, emperor Vesp ...

refers to the city as the most important in the province and the local aristocracy continued to reach the highest circles of power in the 1st century AD, like Aulus Julius Quadratus who was consul

Consul (abbrev. ''cos.''; Latin plural ''consules'') was the title of one of the two chief magistrates of the Roman Republic, and subsequently also an important title under the Roman Empire. The title was used in other European city-states thro ...

in 94 and 105.

Yet it was only under

Yet it was only under Trajan

Trajan ( ; born Marcus Ulpius Traianus, 18 September 53) was a Roman emperor from AD 98 to 117, remembered as the second of the Five Good Emperors of the Nerva–Antonine dynasty. He was a philanthropic ruler and a successful soldier ...

and his successors that a comprehensive redesign and remodelling took place, with the construction of a Roman 'new city' at the base of the Acropolis. The city was the first in the province to receive a second neocorate, from Trajan in AD 113/4. Hadrian

Hadrian ( ; ; 24 January 76 – 10 July 138) was Roman emperor from 117 to 138. Hadrian was born in Italica, close to modern Seville in Spain, an Italic peoples, Italic settlement in Hispania Baetica; his branch of the Aelia gens, Aelia '' ...

raised the city to the rank of metropolis

A metropolis () is a large city or conurbation which is a significant economic, political, and cultural area for a country or region, and an important hub for regional or international connections, commerce, and communications.

A big city b ...

in 123 and thereby elevated it above its local rivals, Ephesus

Ephesus (; ; ; may ultimately derive from ) was an Ancient Greece, ancient Greek city on the coast of Ionia, in present-day Selçuk in İzmir Province, Turkey. It was built in the 10th century BC on the site of Apasa, the former Arzawan capital ...

and Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; , or ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean Sea, Aegean coast of Anatolia, Turkey. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna ...

. An ambitious building programme was carried out: massive temples, a stadium, a theatre

Theatre or theater is a collaborative form of performing art that uses live performers, usually actors to present experiences of a real or imagined event before a live audience in a specific place, often a Stage (theatre), stage. The performe ...

, a huge forum and an amphitheatre

An amphitheatre (American English, U.S. English: amphitheater) is an open-air venue used for entertainment, performances, and sports. The term derives from the ancient Greek ('), from ('), meaning "on both sides" or "around" and ('), meani ...

were constructed. In addition, at the city limits the shrine to Asclepius

Asclepius (; ''Asklēpiós'' ; ) is a hero and god of medicine in ancient Religion in ancient Greece, Greek religion and Greek mythology, mythology. He is the son of Apollo and Coronis (lover of Apollo), Coronis, or Arsinoe (Greek myth), Ars ...

(the god of healing) was expanded into a lavish spa. This sanctuary grew in fame and was considered one of the most famous healing centers of the Roman world.

In the middle of the 2nd century Pergamon was one of the largest cities in the province, and had around 200,000 inhabitants.

In the middle of the 2nd century Pergamon was one of the largest cities in the province, and had around 200,000 inhabitants. Galen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus (; September 129 – AD), often Anglicization, anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Ancient Rome, Roman and Greeks, Greek physician, surgeon, and Philosophy, philosopher. Considered to be one o ...

, the most famous physician of antiquity aside from Hippocrates

Hippocrates of Kos (; ; ), also known as Hippocrates II, was a Greek physician and philosopher of the Classical Greece, classical period who is considered one of the most outstanding figures in the history of medicine. He is traditionally referr ...

, was born at Pergamon and received his early training at the Asclepieion. At the beginning of the 3rd century Caracalla

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (born Lucius Septimius Bassianus, 4 April 188 – 8 April 217), better known by his nickname Caracalla (; ), was Roman emperor from 198 to 217 AD, first serving as nominal co-emperor under his father and then r ...

granted the city a third neocorate, but a decline had already set in. The economic strength of Pergamon collapsed during the crisis of the Third Century

The Crisis of the Third Century, also known as the Military Anarchy or the Imperial Crisis, was a period in History of Rome, Roman history during which the Roman Empire nearly collapsed under the combined pressure of repeated Barbarian invasions ...

, as the city was badly damaged in an earthquake in 262 and was sacked by the Goths

The Goths were a Germanic people who played a major role in the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the emergence of medieval Europe. They were first reported by Graeco-Roman authors in the 3rd century AD, living north of the Danube in what is ...

shortly thereafter. In late antiquity

Late antiquity marks the period that comes after the end of classical antiquity and stretches into the onset of the Early Middle Ages. Late antiquity as a period was popularized by Peter Brown (historian), Peter Brown in 1971, and this periodiza ...

, it experienced a limited economic recovery.

Byzantine period

In AD 663/4, Pergamon was captured by raidingArabs

Arabs (, , ; , , ) are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in West Asia and North Africa. A significant Arab diaspora is present in various parts of the world.

Arabs have been in the Fertile Crescent for thousands of yea ...

for the first time. As a result of the ongoing Arab threat, the area of settlement retracted to the acropolis

An acropolis was the settlement of an upper part of an ancient Greek city, especially a citadel, and frequently a hill with precipitous sides, mainly chosen for purposes of defense. The term is typically used to refer to the Acropolis of Athens ...

, which the Emperor Constans II

Constans II (; 7 November 630 – 15 July 668), also called "the Bearded" (), was the Byzantine emperor from 641 to 668. Constans was the last attested emperor to serve as Roman consul, consul, in 642, although the office continued to exist unti ...

() fortified with a wall built of spolia

''Spolia'' (Latin for 'spoils'; : ''spolium'') are stones taken from an old structure and repurposed for new construction or decorative purposes. It is the result of an ancient and widespread practice (spoliation) whereby stone that has been quar ...

.

During the middle Byzantine period, the city was part of the Thracesian Theme

The Thracesian Theme (, ''Thrakēsion thema''), more properly known as the Theme of the Thracesians (, ''thema Thrakēsiōn'', often simply , ''Thrakēsioi''), was a Byzantine theme (a military-civilian province) in western Asia Minor (modern Tu ...

, and from the time of Leo VI the Wise

Leo VI, also known as Leo the Wise (; 19 September 866 – 11 May 912), was Byzantine Emperor from 886 to 912. The second ruler of the Macedonian dynasty (although his parentage is unclear), he was very well read, leading to his epithet. During ...

() of the Theme of Samos. 7th-century sources attest an Armenian

Armenian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Armenia, a country in the South Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Armenians, the national people of Armenia, or people of Armenian descent

** Armenian diaspora, Armenian communities around the ...

community in Pergamon, probably formed of refugees from the Muslim conquests The Muslim conquests, Muslim invasions, Islamic conquests, including Arab conquests, Arab Islamic conquests, also Iranian Muslim conquests, Turkic Muslim conquests etc.

*Early Muslim conquests

** Ridda Wars

**Muslim conquest of Persia

*** Muslim co ...

; this community produced the emperor Philippicus

Philippicus (; ), born Bardanes (; ) was Byzantine emperor from 711 to 713. He took power in a coup against the unpopular emperor Justinian II, and was deposed in a similarly violent manner nineteen months later. During his brief reign, Philippi ...

(). In 716, Pergamon was sacked again by the armies of Maslama ibn Abd al-Malik

Maslama ibn Abd al-Malik (, in Greek sources , ''Masalmas''; – 24 December 738) was an Umayyad prince and one of the most prominent Arab generals of the early decades of the 8th century, leading several campaigns against the Byzantine Empire ...

. It was again rebuilt and refortified after the Arabs abandoned their Siege of Constantinople

Constantinople (part of modern Istanbul, Turkey) was built on the land that links Europe to Asia through Bosporus and connects the Sea of Marmara and the Black Sea. As a transcontinental city within the Silk Road, Constantinople had a strategic ...

in 717–718.

Pergamon suffered from the Seljuk Seljuk (, ''Selcuk'') or Saljuq (, ''Saljūq'') may refer to:

* Seljuk Empire (1051–1153), a medieval empire in the Middle East and central Asia

* Seljuk dynasty (c. 950–1307), the ruling dynasty of the Seljuk Empire and subsequent polities

* S ...

invasion of western Anatolia after the Battle of Manzikert

The Battle of Manzikert or Malazgirt was fought between the Byzantine Empire and the Seljuk Empire on 26 August 1071 near Manzikert, Iberia (theme), Iberia (modern Malazgirt in Muş Province, Turkey). The decisive defeat of the Byzantine army ...

in 1071. Attacks in 1109 and 1113 largely destroyed the city, which was only rebuilt, by Emperor Manuel I Komnenos

Manuel I Komnenos (; 28 November 1118 – 24 September 1180), Latinized as Comnenus, also called Porphyrogenitus (; " born in the purple"), was a Byzantine emperor of the 12th century who reigned over a crucial turning point in the history o ...

(), around 1170. It likely became the capital of the new theme of Neokastra

Neokastra (, "new fortresses", formally θέμα Νεοκάστρων; in Latin sources ''Neocastri'' or ''Neochastron'') was a Byzantine province (theme) of the 12th–13th centuries in north-western Asia Minor (modern Turkey).

Its origin and ext ...

, established by Manuel. Under Isaac II Angelos

Isaac II Angelos or Angelus (; September 1156 – 28 January 1204) was Byzantine Emperor from 1185 to 1195, and co-Emperor with his son Alexios IV Angelos from 1203 to 1204. In a 1185 revolt against the Emperor Andronikos Komnenos, Isaac ...

(), the local see was promoted to a metropolitan bishopric

A metropolis, metropolitanate or metropolitan diocese is an episcopal see whose bishop is the metropolitan bishop or archbishop of an ecclesiastical province. Metropolises, historically, have been important cities in their provinces.

Eastern Ortho ...

, having previously been a suffragan diocese

A suffragan diocese is one of the dioceses other than the metropolitan archdiocese that constitute an ecclesiastical province. It exists in some Christian denominations, in particular the Catholic Church, the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandr ...

of the Metropolis of Ephesus

The Metropolis of Ephesus () was an ecclesiastical territory (metropolis) of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople in western Asia Minor, modern Turkey. Christianity was introduced already in the city of Ephesus in the 1st century AD by Pau ...

.

After the Sack of Constantinople

The sack of Constantinople occurred in April 1204 and marked the culmination of the Fourth Crusade. Crusaders sacked and destroyed most of Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire. After the capture of the city, the Latin Empire ( ...

in 1204 during the Fourth Crusade

The Fourth Crusade (1202–1204) was a Latin Christian armed expedition called by Pope Innocent III. The stated intent of the expedition was to recapture the Muslim-controlled city of Jerusalem, by first defeating the powerful Egyptian Ayyubid S ...

, Pergamon became part of the Empire of Nicaea

The Empire of Nicaea (), also known as the Nicene Empire, was the largest of the three Byzantine Greeks, Byzantine Greek''A Short history of Greece from early times to 1964'' by Walter Abel Heurtley, W. A. Heurtley, H. C. Darby, C. W. Crawley, C ...

. When Emperor Theodore II Laskaris

Theodore II Laskaris or Ducas Lascaris (; November 1221/1222 – 16 August 1258) was Emperor of Nicaea from 1254 to 1258. He was the only child of Emperor John III Doukas Vatatzes and Empress Irene Laskarina. His mother was the eldest da ...

() visited Pergamon in 1250, he was shown the house of Galen, but he saw that the theatre had been destroyed and, except for the walls which he paid some attention to, only the vaults over the Selinus seemed noteworthy to him. The monuments of the Attalids and the Romans were only plundered ruins by this time.

With the expansion of the Anatolian beyliks

Anatolian beyliks (, Ottoman Turkish: ''Tavâif-i mülûk'', ''Beylik''; ) were Turkish principalities (or petty kingdoms) in Anatolia governed by ''beys'', the first of which were founded at the end of the 11th century. A second and more exte ...

, Pergamon was absorbed into the beylik of Karasids

The Karasids or Karasid dynasty (; ), also known as the Principality of Karasi and Beylik of Karasi (''Karasi Beyliği'' or ''Karesi Beyliği'' ), was a Turkish Anatolian beylik (principality) in the area of classical Mysia (modern Balıkesir and ...

shortly after 1300, and then conquered by the Ottoman beylik

The rise of the Ottoman Empire is a period of history that started with the emergence of the Ottoman principality ( Turkish: ''Osmanlı Beyliği'') in , and ended . This period witnessed the foundation of a political entity ruled by the Ottoman ...

. The Ottoman Sultan Murad III

Murad III (; ; 4 July 1546 – 16 January 1595) was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1574 until his death in 1595. His rule saw battles with the Habsburg monarchy, Habsburgs and exhausting wars with the Safavid Iran, Safavids. The long-inde ...

had two large alabaster

Alabaster is a mineral and a soft Rock (geology), rock used for carvings and as a source of plaster powder. Archaeologists, geologists, and the stone industry have different definitions for the word ''alabaster''. In archaeology, the term ''alab ...

urns transported from the ruins of Pergamon and placed on two sides of the nave in the Hagia Sophia

Hagia Sophia (; ; ; ; ), officially the Hagia Sophia Grand Mosque (; ), is a mosque and former Church (building), church serving as a major cultural and historical site in Istanbul, Turkey. The last of three church buildings to be successively ...

in Istanbul

Istanbul is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, largest city in Turkey, constituting the country's economic, cultural, and historical heart. With Demographics of Istanbul, a population over , it is home to 18% of the Demographics ...

.

Pergamon in myth

Pergamon, which traced its founding back toTelephus

In Greek mythology, Telephus (; , ''Tēlephos'', "far-shining") was the son of Heracles and Auge, who was the daughter of king Aleus of Tegea. He was adopted by Teuthras, the king of Mysia, in Asia Minor, whom he succeeded as king. Telephus was ...

, the son of Heracles

Heracles ( ; ), born Alcaeus (, ''Alkaios'') or Alcides (, ''Alkeidēs''), was a Divinity, divine hero in Greek mythology, the son of ZeusApollodorus1.9.16/ref> and Alcmene, and the foster son of Amphitryon.By his adoptive descent through ...

, is not mentioned in Greek myth or epic of the archaic or classical periods. However, in the Epic Cycle

The Epic Cycle () was a collection of Ancient Greek epic poems, composed in dactylic hexameter and related to the story of the Trojan War, including the '' Cypria'', the ''Aethiopis'', the so-called '' Little Iliad'', the '' Iliupersis'', the ' ...

the Telephus myth is already connected with the area of Mysia. Searching for his mother, Telephus visits Mysia on the advice of an oracle. There he becomes Teuthras

In Greek mythology, Teuthras (Ancient Greek: Τεύθρας, gen. Τεύθραντος) was a king of Mysia, and mythological eponym of the town of Teuthrania.

Mythology

Teuthras received Auge, the ill-fated mother of Telephus, and either ...

' son-in-law or foster-son and inherits his kingdom of Teuthrania

Teuthrania () was a town in the western part of ancient Mysia, and the name of its district about the river Caicus, which was believed to be derived from a legendary Mysian king Teuthras. This king is said to have adopted, as his son and succe ...

, encompassing the area between Pergamon and the mouth of the Caicus. Telephus refuses to participate in the Trojan War

The Trojan War was a legendary conflict in Greek mythology that took place around the twelfth or thirteenth century BC. The war was waged by the Achaeans (Homer), Achaeans (Ancient Greece, Greeks) against the city of Troy after Paris (mytho ...

, but his son Eurypylus In Greek mythology, Eurypylus (; ) was the name of several different people:

* Eurypylus, was a Thessalian king, son of Euaemon and Ops. He was a former suitor of Helen thus he led the Thessalians during Trojan War.

* Eurypylus, was son of T ...

fights on the side of the Trojans

Trojan or Trojans may refer to:

* Of or from the ancient city of Troy

* Trojan language, the language of the historical Trojans

Arts and entertainment Music

* ''Les Troyens'' ('The Trojans'), an opera by Berlioz, premiered part 1863, part 1890 ...

. This material was dealt with in a number of tragedies, such as Aeschylus

Aeschylus (, ; ; /524 – /455 BC) was an ancient Greece, ancient Greek Greek tragedy, tragedian often described as the father of tragedy. Academic knowledge of the genre begins with his work, and understanding of earlier Greek tragedy is large ...

' ''Mysi'', Sophocles

Sophocles ( 497/496 – winter 406/405 BC)Sommerstein (2002), p. 41. was an ancient Greek tragedian known as one of three from whom at least two plays have survived in full. His first plays were written later than, or contemporary with, those ...

' ''Aleadae'', and Euripides

Euripides () was a Greek tragedy, tragedian of classical Athens. Along with Aeschylus and Sophocles, he is one of the three ancient Greek tragedians for whom any plays have survived in full. Some ancient scholars attributed ninety-five plays to ...

' ''Telephus'' and ''Auge'', but Pergamon does not seem to have played any role in any of them. The adaptation of the myth is not entirely smooth.

Thus, on the one hand, Eurypylus who must have been part of the dynastic line as a result of the appropriation of the myth, was not mentioned in the hymn sung in honour of Telephus in the Asclepieion. Otherwise he does not seem to have been paid any heed. But the Pergamenes made offerings to Telephus and the grave of his mother Auge

In Greek mythology, Auge (; ; Modern Greek: "av-YEE"), was the daughter of Aleus the king of Tegea in Arcadia, and the virgin priestess of Athena Alea. She was also the mother of the hero Telephus by Heracles.

Auge had sex with Heracles (ei ...

was located in Pergamon near the Caicus. Pergamon thus entered the Trojan epic cycle, with its ruler said to have been an Arcadian who had fought with Telephus against Agamemnon

In Greek mythology, Agamemnon (; ''Agamémnōn'') was a king of Mycenae who commanded the Achaeans (Homer), Achaeans during the Trojan War. He was the son (or grandson) of King Atreus and Queen Aerope, the brother of Menelaus, the husband of C ...

when he landed at the Caicus, mistook it for Troy and began to ravage the land.

On the other hand, the story was linked to the foundation of the city with another myth – that of Pergamus

In Greek mythology, Pergamus (; Ancient Greek: Πέργαμος) was the son of the warrior Neoptolemus and Andromache. Pergamus's parents both figure in the Trojan War, described in Homer's ''The Iliad'': Neoptolemus was the son of Achilles and ...

, the eponymous

An eponym is a noun after which or for which someone or something is, or is believed to be, named. Adjectives derived from the word ''eponym'' include ''eponymous'' and ''eponymic''.

Eponyms are commonly used for time periods, places, innovati ...

hero of the city. He also belonged to the broader cycle of myths related to the Trojan War as the grandson of Achilles

In Greek mythology, Achilles ( ) or Achilleus () was a hero of the Trojan War who was known as being the greatest of all the Greek warriors. The central character in Homer's ''Iliad'', he was the son of the Nereids, Nereid Thetis and Peleus, ...

through his father Neoptolemus

In Greek mythology, Neoptolemus (; ), originally called Pyrrhus at birth (; ), was the son of the mythical warrior Achilles and the princess Deidamia, and the brother of Oneiros. He became the progenitor of the ruling dynasty of the Molossian ...

and of Eetion

In Greek mythology, Eëtion or Eetion (; ) is the king of the Anatolian city of Cilician Thebe. He is said to be the father of Andromache, the wife of the Trojan prince Hector. In the sixth book of the ''Iliad'', Andromache tells her husband t ...

of Thebe through his mother Andromache

In Greek mythology, Andromache (; , ) was the wife of Hector, daughter of Eetion, and sister to Podes. She was born and raised in the city of Cilician Thebe, over which her father ruled. The name means "man battler", "fighter of men" or "m ...

(concubine to Neoptolemus after the death of Hector

In Greek mythology, Hector (; , ) was a Trojan prince, a hero and the greatest warrior for Troy during the Trojan War. He is a major character in Homer's ''Iliad'', where he leads the Trojans and their allies in the defense of Troy, killing c ...

of Troy

Troy (/; ; ) or Ilion (; ) was an ancient city located in present-day Hisarlik, Turkey. It is best known as the setting for the Greek mythology, Greek myth of the Trojan War. The archaeological site is open to the public as a tourist destina ...

). With his mother, he was said to have fled to Mysia where he killed the ruler of Teuthrania and gave the city his own name. There he built a heroon for his mother after her death. In a less heroic version, Grynos the son of Eurypylus named a city after him in gratitude for a favour. These mythic connections seem to be late and are not attested before the 3rd century BC. Pergamus' role remained subordinate, although he did receive some cult worship. Beginning in the Roman period, his image appears on civic coinage and he is said to have had a heroon in the city. Even so, he provided a further, deliberately crafted link to the world of Homer

Homer (; , ; possibly born ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Despite doubts about his autho ...

ic epic. Mithridates VI was celebrated in the city as a new Pergamus.

However, for the Attalids, it was apparently the genealogical connection to Heracles that was crucial, since all the other Hellenistic dynasties had long established such links: the Ptolemies

The Ptolemaic dynasty (; , ''Ptolemaioi''), also known as the Lagid dynasty (, ''Lagidai''; after Ptolemy I's father, Lagus), was a Macedonian Greek royal house which ruled the Ptolemaic Kingdom in Ancient Egypt during the Hellenistic period. ...

derived themselves directly from Heracles, the Antigonids inserted Heracles into their family tree in the reign of Philip V Philip V may refer to:

* Philip V of Macedon (221–179 BC)

* Philip V of France (1293–1322)

* Philip II of Spain, also Philip V, Duke of Burgundy (1526–1598)

* Philip V of Spain

Philip V (; 19 December 1683 – 9 July 1746) was List of Sp ...

at the end of the 3rd century BC at the latest, and the Seleucids

The Seleucid Empire ( ) was a Greek state in West Asia during the Hellenistic period. It was founded in 312 BC by the Macedonian general Seleucus I Nicator, following the division of the Macedonian Empire founded by Alexander the Great, ...

claimed descent from Apollo

Apollo is one of the Twelve Olympians, Olympian deities in Ancient Greek religion, ancient Greek and Ancient Roman religion, Roman religion and Greek mythology, Greek and Roman mythology. Apollo has been recognized as a god of archery, mu ...

. All of these claims derive their significance from Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon (; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), most commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip ...

, who claimed descent from Heracles, through his father Philip II.

In their constructive adaptation of the myth, the Attalids stood within the tradition of the other, older Hellenistic dynasties, who legitimized themselves through divine descent, and sought to increase their own prestige. The inhabitants of Pergamon enthusiastically followed their lead and took to calling themselves ''Telephidai'' () and referring to Pergamon itself in poetic registers as the 'Telephian city' ().

History of research and excavation

The first mention of Pergamon in written records after ancient times comes from the 13th century. Beginning withCiriaco de' Pizzicolli Ciriaco is a male given name in Italian language, Italian () and Spanish language, Spanish (). In Portuguese, it's spelled Ciríaco ().

It derives from the Greeks, Greek given name Κυριακός (also Κυριάκος) which means ''of the Lord ...

in the 15th century, ever more travellers visited the place and published their accounts of it. The key description is that of Thomas Smith, who visited the Levant in 1668 and transmitted a detailed description of Pergamon, to which the great 17th century travellers Jacob Spon

Jacob Spon (or Jacques; in English dictionaries given as James; 1647 – 25 December 1685) was a French doctor and archaeologist. He was a pioneer in the exploration of the monuments of Greece, and a scholar of international reputation in the dev ...

and George Wheler George Wheler may refer to:

* Sir George Wheler (travel writer) (1651–1724), English clergyman and travel writer

* George Wheler (politician)

George Wheler (September 2, 1836 – July 6, 1908) was a mill owner and political figure in Ontar ...

were able to add nothing significant in their own accounts.

In the late 18th century, these visits were reinforced by a scholarly (especially ancient historical) desire for research, epitomised by Marie-Gabriel-Florent-Auguste de Choiseul-Gouffier

Marie-Gabriel-Florent-Auguste de Choiseul (27 September 1752, Paris – 20 June 1817, Aix-la-Chapelle), called Auguste de Choiseul-Gouffier (), was a French diplomat and aristocrat from the Gouffier branch of the Choiseul family. A member of t ...

, a traveller in Asia Minor and French ambassador to the Sublime Porte

The Sublime Porte, also known as the Ottoman Porte or High Porte ( or ''Babıali''; ), was a synecdoche or metaphor used to refer collectively to the central government of the Ottoman Empire in Istanbul. It is particularly referred to the buildi ...

in Istanbul

Istanbul is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, largest city in Turkey, constituting the country's economic, cultural, and historical heart. With Demographics of Istanbul, a population over , it is home to 18% of the Demographics ...

from 1784 to 1791. At the beginning of the 19th century, Charles Robert Cockerell

Charles Robert Cockerell (27 April 1788 – 17 September 1863) was an England, English architect, archaeologist, and writer. He studied architecture under Robert Smirke (architect), Robert Smirke. He went on an extended Grand Tour lasting sev ...

produced a detailed account and Otto Magnus von Stackelberg made important sketches. A proper, multi-page description with plans, elevations, and views of the city and its ruins was first produced by Charles Texier

Félix Marie Charles Texier (22 August 1802, Versailles – 1 July 1871, Paris) was a French historian, architect and archaeologist. Texier published a number of significant works involving personal travels throughout Asia Minor and the Middle Eas ...

when he published the second volume of his ''Description de l'Asie mineure''.

In 1864–5, the German engineer Carl Humann

Carl Humann (first name also ''Karl''; 4 January 1839 – 12 April 1896) was a German engineer, architect and archaeologist. He discovered the Pergamon Altar.

Biography

Early years

Humann was born in Steele, part of today's Essen - German ...

visited Pergamon for the first time. For the construction of the road from Pergamon to Dikili

Dikili is a municipality and district of İzmir Province, Turkey. Its area is 534 km2, and its population is 47,360 (2022).

The district is quite picturesque both along its Aegean shoreline and in its inland parts, and is a popular summer r ...

for which he had undertaken planning work and topographical studies, he returned in 1869 and began to focus intensively on the legacy of the city. In 1871, he organised a small expedition there under the leadership of Ernst Curtius

Ernst Curtius (; 2 September 181411 July 1896) was a German archaeologist, historian and museum director.

Biography

He was born in Lübeck. On completing his university studies he was chosen by Christian August Brandis, C. A. Brandis to acco ...

. As a result of this short but intensive investigation, two fragments of a great frieze were discovered and transported to Berlin

Berlin ( ; ) is the Capital of Germany, capital and largest city of Germany, by both area and List of cities in Germany by population, population. With 3.7 million inhabitants, it has the List of cities in the European Union by population withi ...

for detailed analysis, where they received some interest, but not a lot. It is not clear who connected these fragments with the Great Altar in Pergamon mentioned by Lucius Ampelius

The ''Liber Memorialis'' is an ancient book in Latin featuring an extremely concise summary—a kind of index—of universal history from earliest times to the reign of Trajan. It was written by Lucius Ampelius, who was possibly a tutor o ...

. However, when the archaeologist Alexander Conze

Alexander Christian Leopold Conze (10 December 1831 – 19 July 1914) was a German archaeologist, who specialized in ancient Greek art.

He was a native of Hanover, and studied at the universities of Göttingen and Berlin. In 1855 he obtained his ...

took over direction of the department of ancient sculpture at the Royal Museums of Berlin, he quickly initiated a programme for the excavation and protection of the monuments connected to the sculpture, which were widely suspected to include the Great Altar.

As a result of these efforts, Carl Humann, who had been carrying out low-level excavations at Pergamon for the previous few years and had discovered for example the architrave inscription of the Temple of Demeter in 1875, was entrusted with carry out work in the area of the altar of Zeus in 1878, where he continued to work until 1886. With the approval of the

As a result of these efforts, Carl Humann, who had been carrying out low-level excavations at Pergamon for the previous few years and had discovered for example the architrave inscription of the Temple of Demeter in 1875, was entrusted with carry out work in the area of the altar of Zeus in 1878, where he continued to work until 1886. With the approval of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

, the reliefs discovered there were transported to Berlin, where the Pergamon Museum

The Pergamon Museum (; ) is a Kulturdenkmal , listed building on the Museum Island in the Mitte (locality), historic centre of Berlin, Germany. It was built from 1910 to 1930 by order of Emperor Wilhelm II, German Emperor, Wilhelm II and accordi ...

was opened for them in 1907. The work was continued by Conze, who aimed for the most complete possible exposure and investigation of the historic city and citadel that was possible. He was followed by the architectural historian Wilhelm Dörpfeld

Wilhelm Dörpfeld (26 December 1853 – 25 April 1940) was a German architect and archaeologist, a pioneer of stratigraphy, stratigraphic excavation and precise graphical documentation of archaeological projects. He is famous for his work on B ...

from 1900 to 1911, who was responsible for the most important discoveries. Under his leadership the Lower Agora, the House of Attalos, the Gymnasion, and the Sanctuary of Demeter were brought to light.

The excavations were interrupted by the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

and were only resumed in 1927 under the leadership of Theodor Wiegand

Theodor Wiegand (30 October 1864 – 19 December 1936) was a German archaeologist.

Wiegand was born in Bendorf, Rhenish Prussia. He studied at the universities of Munich, Berlin, and Freiburg. In 1894 he worked under Wilhelm Dörpfeld at th ...

, who remained in this post until 1939. He concentrated on further excavation of the upper city, the Asklepieion, and the Red Basilica

The "Red Basilica" (), also called variously the Red Hall and Red Courtyard, is a monumental ruined temple in the ancient city of Pergamon, now Bergama, in western Turkey. The temple was built during the Roman Empire, probably in the time of Hadr ...

. The Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

also caused a break in work at Pergamon, which lasted until 1957. From 1957 to 1968, Erich Boehringer

The given name Eric, Erich, Erikk, Erik, Erick, Eirik, or Eiríkur is derived from the Old Norse name ''Eiríkr'' (or ''Eríkr'' in Old East Norse due to monophthongization).

The first element, ''ei-'' may be derived from the older Proto-Nor ...

worked on the Asklepieion in particular, but also carried out important work on the lower city as a whole and performed survey work, which increased knowledge of the countryside surrounding the city. In 1971, after a short pause, Wolfgang Radt succeeded him as leader of excavations and directed the focus of research on the residential buildings of Pergamon, but also on technical issues, like the water management system of the city which supported a population of 200,000 at its height. He also carried out conservation projects which were of vital importance for maintaining the material remains of Pergamon. Since 2006, the excavations have been led by Felix Pirson

Felix may refer to:

* Felix (name), people and fictional characters with the name

Places