People From Cornwall on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Cornish people or the Cornish (, ) are an

and a recognised national minority in the

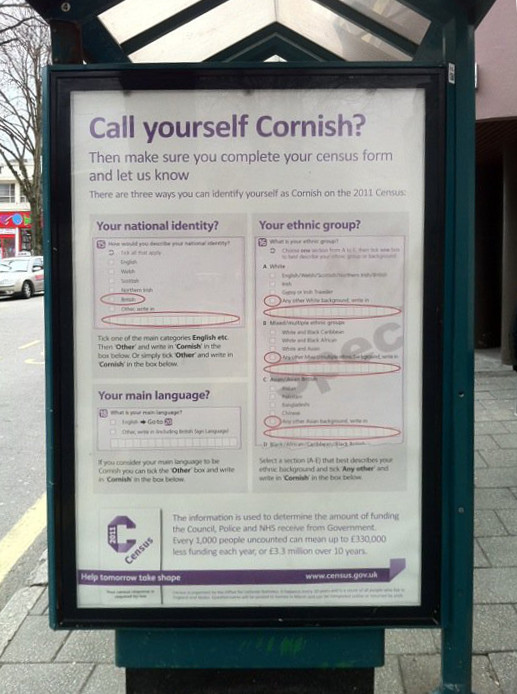

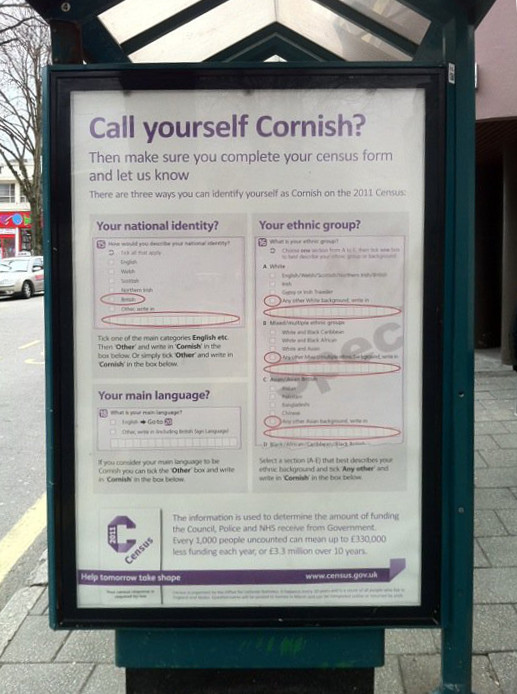

A campaign for the inclusion of a Cornish tick-box in the nationality section of the 2011 census failed to win the support of Parliament in 2009. As a consequence, posters were created by the census organisation and

A campaign for the inclusion of a Cornish tick-box in the nationality section of the 2011 census failed to win the support of Parliament in 2009. As a consequence, posters were created by the census organisation and

Traditionally, the Cornish are thought to have been descended from the Iron Age

Traditionally, the Cornish are thought to have been descended from the Iron Age  Throughout

Throughout

The

The

The

The

The Cornish people are concentrated in Cornwall, but after the

The Cornish people are concentrated in Cornwall, but after the

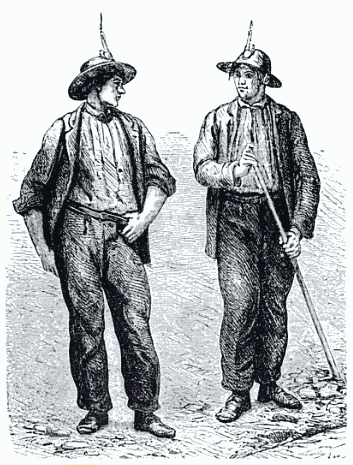

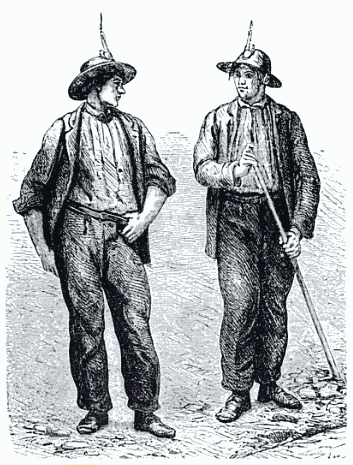

From the beginning of Australia's colonial period until after the Second World War, people from the United Kingdom made up a large majority of people coming to Australia, meaning that many Australian-born people can trace their origins to Britain. The Cornish people in particular were actively encouraged to emigrate to Australia following the demise of Cornish mining in the 19th century. A "vigorous recruiting campaign" was launched to encourage the Cornish to aid with

From the beginning of Australia's colonial period until after the Second World War, people from the United Kingdom made up a large majority of people coming to Australia, meaning that many Australian-born people can trace their origins to Britain. The Cornish people in particular were actively encouraged to emigrate to Australia following the demise of Cornish mining in the 19th century. A "vigorous recruiting campaign" was launched to encourage the Cornish to aid with

In 1825 a band of 60 Cornishmen left Falmouth for

In 1825 a band of 60 Cornishmen left Falmouth for

The survival of a distinct Cornish culture has been attributed to Cornwall's geographic isolation. Contemporaneously, the underlying notion of Cornish culture is that it is distinct from the

The survival of a distinct Cornish culture has been attributed to Cornwall's geographic isolation. Contemporaneously, the underlying notion of Cornish culture is that it is distinct from the

The

The

ethnic group

An ethnicity or ethnic group is a group of people with shared attributes, which they collectively believe to have, and long-term endogamy. Ethnicities share attributes like language, culture, common sets of ancestry, traditions, society, re ...

native to, or associated with Cornwall

Cornwall (; or ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is also one of the Celtic nations and the homeland of the Cornish people. The county is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, ...

:and a recognised national minority in the

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

, which (like the Welsh and Bretons

The Bretons (; or , ) are an ethnic group native to Brittany, north-western France. Originally, the demonym designated groups of Common Brittonic, Brittonic speakers who emigrated from Dumnonia, southwestern Great Britain, particularly Cornwal ...

) can trace its roots to the ancient Britons

The Britons (Linguistic reconstruction, *''Pritanī'', , ), also known as Celtic Britons or Ancient Britons, were the Celts, Celtic people who inhabited Great Britain from at least the British Iron Age until the High Middle Ages, at which point ...

who inhabited Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-west coast of continental Europe, consisting of the countries England, Scotland, and Wales. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the List of European ...

from somewhere between the 11th and 7th centuries BC and inhabited Britain at the time of the Roman conquest. Many in Cornwall today continue to assert a distinct identity separate from or in addition to English or British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and culture ...

identities. Cornish identity has also been adopted by some migrants into Cornwall, as well as by emigrant and descendant communities from Cornwall, the latter sometimes referred to as the Cornish diaspora. Although not included as a tick-box option in the UK census, the numbers of those writing in a Cornish ethnic and national identity are officially recognised and recorded.

Throughout classical antiquity

Classical antiquity, also known as the classical era, classical period, classical age, or simply antiquity, is the period of cultural History of Europe, European history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD comprising the inter ...

, the ancient Celtic Britons

The Britons ( *''Pritanī'', , ), also known as Celtic Britons or Ancient Britons, were the Celtic people who inhabited Great Britain from at least the British Iron Age until the High Middle Ages, at which point they diverged into the Welsh, ...

formed a series of tribes

The term tribe is used in many different contexts to refer to a category of human social group. The predominant worldwide use of the term in English is in the discipline of anthropology. The definition is contested, in part due to conflict ...

, kingdoms, cultures and identities throughout Great Britain; the Dumnonii

The Dumnonii or Dumnones were a Britons (historical), British List of ancient Celtic peoples and tribes, tribe who inhabited Dumnonia, the area now known as Cornwall and Devon (and some areas of present-day Dorset and Somerset) in the further pa ...

and Cornovii were the Celtic tribes

This is a list of ancient Celts, Celtic peoples and tribes.

Continental Celts

Continental Celts were the Celtic peoples that inhabited mainland Europe and Anatolia (also known as Asia Minor). In the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC, Celts inhabited a la ...

who inhabited what was to become Cornwall during the Iron Age

The Iron Age () is the final epoch of the three historical Metal Ages, after the Chalcolithic and Bronze Age. It has also been considered as the final age of the three-age division starting with prehistory (before recorded history) and progre ...

, Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of Roman civilization

*Epistle to the Romans, shortened to Romans, a letter w ...

and post-Roman periods. The name Cornwall and its demonym

A demonym (; ) or 'gentilic' () is a word that identifies a group of people ( inhabitants, residents, natives) in relation to a particular place. Demonyms are usually derived from the name of the place ( hamlet, village, town, city, region, ...

Cornish are derived from the Celtic Cornovii tribe. The Anglo-Saxon invasion and settlement of Britain starting from the late 5th and early 6th centuries and the arrival of Scots from Ireland during the same period gradually restricted the Romano-British culture and Brittonic language into parts of the north and west of Great Britain by the 10th century, whilst the inhabitants of southern, central and eastern Britain became English and much of the north became Scottish. The Cornish people, who shared the Brythonic language with the Welsh, Cumbrics and Picts

The Picts were a group of peoples in what is now Scotland north of the Firth of Forth, in the Scotland in the early Middle Ages, Early Middle Ages. Where they lived and details of their culture can be gleaned from early medieval texts and Pic ...

, and also the Bretons who had migrated across the sea to escape the Anglo-Saxon invasions, were referred to in the Old English

Old English ( or , or ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the Early Middle Ages. It developed from the languages brought to Great Britain by Anglo-S ...

language as the "Westwalas" meaning West Welsh. The Battle of Deorham between the Britons and Anglo-Saxons

The Anglo-Saxons, in some contexts simply called Saxons or the English, were a Cultural identity, cultural group who spoke Old English and inhabited much of what is now England and south-eastern Scotland in the Early Middle Ages. They traced t ...

is thought to have resulted in a loss of land links with the people of Wales.

The Cornish people and their Brythonic Cornish language

Cornish (Standard Written Form: or , ) is a Southwestern Brittonic language, Southwestern Brittonic language of the Celtic language family. Along with Welsh language, Welsh and Breton language, Breton, Cornish descends from Common Brittonic, ...

experienced a slow process of anglicisation

Anglicisation or anglicization is a form of cultural assimilation whereby something non-English becomes assimilated into or influenced by the culture of England. It can be sociocultural, in which a non-English place adopts the English language ...

and attrition during the medieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of World history (field), global history. It began with the fall of the West ...

and early modern period

The early modern period is a Periodization, historical period that is defined either as part of or as immediately preceding the modern period, with divisions based primarily on the history of Europe and the broader concept of modernity. There i ...

s. By the 18th century, and following the creation of the Kingdom of Great Britain

Great Britain, also known as the Kingdom of Great Britain, was a sovereign state in Western Europe from 1707 to the end of 1800. The state was created by the 1706 Treaty of Union and ratified by the Acts of Union 1707, which united the Kingd ...

, the Cornish language and to some degree identity had faded, largely replaced by the English language

English is a West Germanic language that developed in early medieval England and has since become a English as a lingua franca, global lingua franca. The namesake of the language is the Angles (tribe), Angles, one of the Germanic peoples th ...

(albeit Cornish-influenced West Country dialects and Anglo-Cornish

The Cornish dialect (also known as Cornish English, Anglo-Cornish or Cornu-English) is a dialect of English spoken in Cornwall by Cornish people. Dialectal English spoken in Cornwall is to some extent influenced by Cornish language, Cornish gra ...

) or British identity. A Celtic revival

The Celtic Revival (also referred to as the Celtic Twilight) is a variety of movements and trends in the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries that see a renewed interest in aspects of Celtic culture. Artists and writers drew on the traditions of Gae ...

during the early-20th century enabled a cultural self-consciousness in Cornwall that revitalised the Cornish language and roused the Cornish to express a distinctly Brittonic Celtic heritage. The Cornish language was granted official recognition under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages

The European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages (ECRML) is a European treaty (CETS 148) adopted in 1992 under the auspices of the Council of Europe to protect and promote historical regional and minority languages in Europe. However, t ...

in 2002, and in 2014 the Cornish people were recognised and afforded protection by the UK Government under the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities

The Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities (FCNM) is a multilateral treaty of the Council of Europe aimed at protecting the minority rights, rights of minorities. It came into effect in 1998 and by 2009 it had been ratif ...

.

In the 2021 census, the population of Cornwall, including the Isles of Scilly

The Isles of Scilly ( ; ) are a small archipelago off the southwestern tip of Cornwall, England. One of the islands, St Agnes, Isles of Scilly, St Agnes, is over farther south than the most southerly point of the Great Britain, British mainla ...

, was recorded as 570,300. The Cornish self-government movement has called for greater recognition of Cornish culture, politics, and language, and urged that Cornish people be accorded greater status, exemplified by the call for them to be one of the listed ethnic groups in the United Kingdom Census 2011

A Census in the United Kingdom, census of the population of the United Kingdom is taken every ten years. The 2011 census was held in all countries of the UK on 27 March 2011. It was the first UK census which could be completed online via the Inter ...

form.

Classification

Both geographic and historical factors distinguish the Cornish as an ethnic group further supported by identifiable genetic variance between the populations of Cornwall, neighbouring Devon and England as published in a 2012 Oxford University study. Throughout medieval andEarly Modern Britain

Early modern Britain is the history of the island of Great Britain roughly corresponding to the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries. Major historical events in early modern British history include numerous wars, especially with France, along with the ...

, the Cornish were at some points accorded the same status as the English and Welsh and considered a separate race or nation, distinct from their neighbours, with their own language, society and customs. A process of Anglicisation

Anglicisation or anglicization is a form of cultural assimilation whereby something non-English becomes assimilated into or influenced by the culture of England. It can be sociocultural, in which a non-English place adopts the English language ...

between 1485 and 1700 led to the Cornish adopting English language, culture and civic identity, a view reinforced by Cornish historian A. L. Rowse

Alfred Leslie Rowse (4 December 1903 – 3 October 1997) was a British historian and writer, best known for his work on Elizabethan England and books relating to Cornwall.

Born in Cornwall and raised in modest circumstances, he was encourag ...

who said they were gradually "absorbed into the mainstream of English life". Although "decidedly modern" and "largely retrospective" in its identity politics

Identity politics is politics based on a particular identity, such as ethnicity, Race (human categorization), race, nationality, religion, Religious denomination, denomination, gender, sexual orientation, Socioeconomic status, social background ...

, Cornish and Celtic associations have advanced the notion of a distinct Cornish national and ethnic identity since the late 20th century. In the United Kingdom Census 2001

A nationwide census, known as Census 2001, was conducted in the United Kingdom on Sunday, 29 April 2001. This was the 20th Census in the United Kingdom, UK census and recorded a resident population of 58,789,194.

The 2001 UK census was organise ...

, despite no explicit "Cornish" option being available, approximately 34,000 people in Cornwall and 3,500 people elsewhere in the UK—a combined total equal to nearly 7 per cent of the population of Cornwall—identified themselves as ethnic Cornish by writing this in under the "other" ethnicity option. The census figures show a change in identity from West to East, in Penwith

Penwith (; ) is an area of Cornwall, England, located on the peninsula of the same name. It is also the name of a former Non-metropolitan district, local government district, whose council was based in Penzance. The area is named after one ...

9.2 per cent identified as ethnically Cornish, in Kerrier it was 7.5 per cent, in Carrick 6.6 per cent, Restormel 6.3 per cent, North Cornwall 6 per cent, and Caradon 5.6 per cent. Weighting of the 2001 Census data gives a figure of 154,791 people with Cornish ethnicity living in Cornwall.

The Cornish have been described as "a special case" in England, with an "ethnic rather than regional identity". Structural changes to the politics of the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom is a constitutional monarchy which, by legislation and convention, operates as a unitary parliamentary democracy. A hereditary monarch, currently King Charles III, serves as head of state while the Prime Minister of th ...

, particularly the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational union, supranational political union, political and economic union of Member state of the European Union, member states that are Geography of the European Union, located primarily in Europe. The u ...

and devolution

Devolution is the statutory delegation of powers from the central government of a sovereign state to govern at a subnational level, such as a regional or local level. It is a form of administrative decentralization. Devolved territori ...

, have been cited as the main stimulus to "a growing interest in Cornish identity and distinctiveness" in late-20th century Britain. The British are the citizens of the United Kingdom, a people who by convention consist of four national groups: the English, Northern Irish

The people of Northern Ireland are all people born in Northern Ireland and having, at the time of their birth, at least one parent who is a British Nationality Law, British citizen, an Irish nationality law, Irish citizen or is otherwis ...

, Scots and Welsh. In the 1990s it was said that the notion that the Cornish are to be classified as a nation comparable to the English, Irish, Scots and Welsh, "has practically vanished from the popular consciousness" outside Cornwall, and that, despite a "real and substantive" identity, the Cornish "struggle for recognition as a national group distinct from the English". However, in 2014, after a 15-year campaign, the UK government officially recognised the Cornish as a national minority under the Council of Europe

The Council of Europe (CoE; , CdE) is an international organisation with the goal of upholding human rights, democracy and the Law in Europe, rule of law in Europe. Founded in 1949, it is Europe's oldest intergovernmental organisation, represe ...

's Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities

The Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities (FCNM) is a multilateral treaty of the Council of Europe aimed at protecting the minority rights, rights of minorities. It came into effect in 1998 and by 2009 it had been ratif ...

, giving the Cornish the same status as the Welsh, Scots and Irish within the UK.

Inhabitants of Cornwall may have multiple political

Politics () is the set of activities that are associated with decision-making, making decisions in social group, groups, or other forms of power (social and political), power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of Social sta ...

allegiances, adopting mixed, dual or hyphenated identities such as "Cornish first and British second", "Cornish and British and European", or, like Phil Vickery (a rugby union

Rugby union football, commonly known simply as rugby union in English-speaking countries and rugby 15/XV in non-English-speaking world, Anglophone Europe, or often just rugby, is a Contact sport#Terminology, close-contact team sport that orig ...

prop for the England national rugby union team

The England national rugby union team represents the Rugby Football Union (RFU) in international rugby union. They compete in the annual Six Nations Championship with France national rugby union team, France, Ireland national rugby union team, ...

and British and Irish Lions

The British & Irish Lions is a rugby union team selected from players eligible for the national teams of England national rugby union team, England, Ireland national rugby union team, Ireland, Scotland national rugby union team, Scotland, and ...

), describe themselves as "Cornish" and "English". Meanwhile, another international rugby union player, Josh Matavesi, describes himself as Cornish- Fijian and Cornish not English.

A survey by Plymouth University

The University of Plymouth is a public research university based predominantly in Plymouth, England, where the main campus is located, but the university has campuses and affiliated colleges across South West England. With students, it is the ...

in 2000 found that 30% of children in Cornwall felt "Cornish, not English". A 2004 survey on national identity by the finance firm Morgan Stanley

Morgan Stanley is an American multinational investment bank and financial services company headquartered at 1585 Broadway in Midtown Manhattan, New York City. With offices in 42 countries and more than 80,000 employees, the firm's clients in ...

found that 44% of respondents in Cornwall saw themselves as Cornish rather than British or English. A 2008 University of Exeter

The University of Exeter is a research university in the West Country of England, with its main campus in Exeter, Devon. Its predecessor institutions, St Luke's College, Exeter School of Science, Exeter School of Art, and the Camborne School of ...

study conducted in 16 towns across Cornwall found that 59% felt themselves to be Cornish and 41% felt "More Cornish than English", while for over a third of respondents the Cornish identity formed their primary ''national'' identity. Genealogy and family history were considered to be the chief criteria for 'being' Cornish, particularly among those who possessed such ties, while being born in Cornwall was also held to be important.

A 2008 study by the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh (, ; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in Post-nominal letters, post-nominals) is a Public university, public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Founded by the City of Edinburgh Council, town council under th ...

of 15- and 16-year-old schoolchildren in Cornwall found that 58% of respondents felt themselves to be either 'Fairly' or 'Very much' Cornish. The other 42% may be the result of in-migration to the area during the second half of the twentieth century.

A 2010 study by the University of Exeter

The University of Exeter is a research university in the West Country of England, with its main campus in Exeter, Devon. Its predecessor institutions, St Luke's College, Exeter School of Science, Exeter School of Art, and the Camborne School of ...

into the meaning of contemporary Cornish identity across Cornwall found that there was a "west-east distance decay in the strength of the Cornish identity." The study was conducted amongst the farming community as they were deemed to be the socio-professional group most objectively representative of Cornishness. All participants categorised themselves as Cornish and identified Cornish as their primary ethnic group orientation. Those in the west primarily thought of themselves as Cornish and British/Celtic, while those in the east tended to think of themselves as Cornish and English. All participants in West Cornwall who identified as Cornish and not English described people in East Cornwall, without hesitation, as equally Cornish as themselves. Those who identified as Cornish and English stressed the primacy of their Cornishness and a capacity to distance themselves from their Englishness. Ancestry was seen as the most important criterion for being categorised as Cornish, above place of birth or growing up in Cornwall. This study supports a 1988 study by Mary McArthur that had found that the meanings of Cornishness varied substantially, from local to national identity. Both studies also observed that the Cornish were less materialistic than the English. The Cornish generally saw the English, or city people, as being "less friendly and more aggressively self-promoting and insensitive". The Cornish saw themselves as friendly, welcoming and caring.

In November 2010 British Prime Minister, David Cameron

David William Donald Cameron, Baron Cameron of Chipping Norton (born 9 October 1966) is a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 2010 to 2016. Until 2015, he led the first coalition government in the UK s ...

, said "I think Cornish national identity is very powerful" and that his government would "devolve a lot of power to Cornwall – that will go to the Cornish unitary authority."

2011 and 2021 UK Census

A campaign for the inclusion of a Cornish tick-box in the nationality section of the 2011 census failed to win the support of Parliament in 2009. As a consequence, posters were created by the census organisation and

A campaign for the inclusion of a Cornish tick-box in the nationality section of the 2011 census failed to win the support of Parliament in 2009. As a consequence, posters were created by the census organisation and Cornwall Council

Cornwall Council ( ), known between 1889 and 2009 as Cornwall County Council (), is the local authority which governs the non-metropolitan county of Cornwall in South West England. Since 2009 it has been a Unitary authorities of England, unitary ...

which advised residents how they could identify themselves as Cornish by writing it in the national identity and ethnicity sections and record Cornish in the main language section. Additionally, people could record Cornwall as their country of birth.

Like other identities, Cornish has an allocated census code, (06), the same as for 2001, which applied and was counted throughout Britain. People were first able to record their ethnicity as Cornish in the 2001 UK Census, and some 37,000 people did so by writing it in.

A total of 83,499 people in England and Wales were described as having a Cornish national identity. 59,456 of these were described as Cornish only, 6,261 as Cornish and British, and 17,782 as Cornish and at least one other identity, with or without British. Within Cornwall the total was 73,220 (14% of the population) with 52,793 (9.9%) as Cornish only, 5,185 (1%) as Cornish and British, and 15,242 (2.9%) as Cornish and at least one other identity, with or without British.

In Scotland 467 people described themselves as having Cornish national identity. 254 with Cornish identity only, 39 as Scottish and Cornish, and 174 having Cornish identity and at least one other UK identity (excluding Scottish).

In the 2021 census, 89,084 people in England and Wales described their national identity as Cornish only and 10,670 as Cornish and British. Within Cornwall, 79,938 people (14.0% of the population) specified a Cornish only identity and 9,146 (1.6%) Cornish in combination with British.

Schools census (PLASC)

Since 2006 school children in Cornwall have been able to record themselves as ethnically Cornish on the annual Schools Census (PLASC). Since then the number identifying as Cornish has risen from 24% to 51% in 2017. The Department for Education recommends that parents and guardians determine the ethnicity of children at primary schools whilst pupils at secondary schools can decide their own ethnicity. *2006: 23.7 percent – 17,218 pupils out of 72,571 *2007: 27.3 percent – 19,988 pupils out of 72,842 *2008: 30.3 percent – 21,610 pupils out of 71,302 *2009: 33.9 percent – 23,808 pupils out of 70,275 *2010: 37.2 percent – 26,140 pupils out of 69,950 *2011: 40.9 percent – 28,584 pupils out of 69,811 *2012: 43.0 percent – 30,181 pupils out of 69,909 *2013: 46.0 percent – 32,254 pupils out of 70,097''Ethnicity breakdown from the schools census, Table: Summary of Pupils Ethnic Background in Cornwall taken at January in 2011, 2012 and 2013'', Cornwall Council *2014: 48.0 percent *2017: 51.1 percent *2020: 45.9 percent - due to an error in the management system of a number of schools, pupils identifying as ''White Cornish'' were inadvertently changed to ''Any Other White'' resulting in a reduced figure for the year 2020.History

Ancestral roots

Traditionally, the Cornish are thought to have been descended from the Iron Age

Traditionally, the Cornish are thought to have been descended from the Iron Age Celts

The Celts ( , see Names of the Celts#Pronunciation, pronunciation for different usages) or Celtic peoples ( ) were a collection of Indo-European languages, Indo-European peoples. "The Celts, an ancient Indo-European people, reached the apoge ...

, making them distinct from the English, many (but not all) of whom are descended from the Anglo-Saxons

The Anglo-Saxons, in some contexts simply called Saxons or the English, were a Cultural identity, cultural group who spoke Old English and inhabited much of what is now England and south-eastern Scotland in the Early Middle Ages. They traced t ...

who colonised Great Britain from their homelands in northern Europe and drove the Celts to Britain's western and northern fringes. Recent genetic studies based on ancient DNA have complicated this picture, however. During the Bronze Age

The Bronze Age () was a historical period characterised principally by the use of bronze tools and the development of complex urban societies, as well as the adoption of writing in some areas. The Bronze Age is the middle principal period of ...

, most of the people that had inhabited Britain since the Neolithic era were replaced by Beaker People

The Bell Beaker culture, also known as the Bell Beaker complex or Bell Beaker phenomenon, is an archaeological culture named after the inverted-bell beaker drinking vessel used at the beginning of the European Bronze Age, arising from around ...

, while scholars have argued that the introduction of the Celtic languages and material culture into Britain and Ireland was by means of cultural diffusion, rather than any substantial migration. Genetic evidence has also suggested that while ancestry inherited from the Anglo-Saxons makes up a significant part of the modern English gene pool (one study suggested an average 38% contribution in eastern England), they did not displace all of the previous inhabitants. A 2015 study found that modern Cornish populations had less Anglo-Saxon ancestry than people from central and southern England, and that they were genetically distinct from their neighbors in Devon

Devon ( ; historically also known as Devonshire , ) is a ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by the Bristol Channel to the north, Somerset and Dorset to the east, the English Channel to the south, and Cornwall to the west ...

. The study also suggested that populations traditionally labelled as "Celtic" showed significant diversity, rather than a unified genetic identity.

Throughout

Throughout classical antiquity

Classical antiquity, also known as the classical era, classical period, classical age, or simply antiquity, is the period of cultural History of Europe, European history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD comprising the inter ...

the Celts spoke Celtic languages

The Celtic languages ( ) are a branch of the Indo-European language family, descended from the hypothetical Proto-Celtic language. The term "Celtic" was first used to describe this language group by Edward Lhuyd in 1707, following Paul-Yve ...

, and formed a series of tribes, cultures and identities, notably the Picts

The Picts were a group of peoples in what is now Scotland north of the Firth of Forth, in the Scotland in the early Middle Ages, Early Middle Ages. Where they lived and details of their culture can be gleaned from early medieval texts and Pic ...

and Gaels

The Gaels ( ; ; ; ) are an Insular Celts, Insular Celtic ethnolinguistic group native to Ireland, Scotland, and the Isle of Man. They are associated with the Goidelic languages, Gaelic languages: a branch of the Celtic languages comprising ...

in the north and the Britons

British people or Britons, also known colloquially as Brits, are the citizens of the United Kingdom, the British Overseas Territories, and the Crown dependencies.: British nationality law governs modern British citizenship and nationality, w ...

in the south. The Britons were themselves a divided people; although they shared the Brythonic languages

The Brittonic languages (also Brythonic or British Celtic; ; ; and ) form one of the two branches of the Insular Celtic languages; the other is Goidelic. It comprises the extant languages Breton, Cornish, and Welsh. The name ''Brythonic'' ...

, they were tribal, and divided into regional societies, and within them sub-groups. Examples of these tribal societies were the Brigantes

The Brigantes were Ancient Britons who in pre-Roman times controlled the largest section of what would become Northern England. Their territory, often referred to as Brigantia, was centred in what was later known as Yorkshire. The Greek geog ...

in the north, and the Ordovices

The Ordovīcēs (Common Brittonic: *''Ordowīces'') were one of the Celtic tribes living in Great Britain before the Roman invasion. Their tribal lands were located in present-day North Wales and England, between the Silures to the south and the ...

, the Demetae

The Demetae were a Celtic people of Iron Age and Roman period, who inhabited modern Pembrokeshire and Carmarthenshire in south-west Wales. The tribe also gave their name to the medieval Kingdom of Dyfed, the modern area and county of Dyfed and ...

, the Silures

The Silures ( , ) were a powerful and warlike tribe or tribal confederation of ancient Britain, occupying what is now south east Wales and perhaps some adjoining areas. They were bordered to the north by the Ordovices; to the east by the Do ...

and the Deceangli

The Deceangli or Deceangi (Welsh: Tegeingl) were one of the Celtic tribes living in Britain, prior to the Roman invasion of the island. The tribe lived in the region near the modern city of Chester but it is uncertain whether their territory c ...

in the west. In the extreme southwest, what was to become Cornwall, were the Dumnonii

The Dumnonii or Dumnones were a Britons (historical), British List of ancient Celtic peoples and tribes, tribe who inhabited Dumnonia, the area now known as Cornwall and Devon (and some areas of present-day Dorset and Somerset) in the further pa ...

and Cornovii, who lived in the Kingdom of Dumnonia

Dumnonia is the Latinised name for a Brythonic kingdom that existed in Sub-Roman Britain between the late 4th and late 8th centuries CE in the more westerly parts of present-day South West England. It was centred in the area of modern Devon, ...

. The Roman conquest of Britain

The Roman conquest of Britain was the Roman Empire's conquest of most of the island of Great Britain, Britain, which was inhabited by the Celtic Britons. It began in earnest in AD 43 under Emperor Claudius, and was largely completed in the ...

in the 1st century introduced Romans to Britain, who upon their arrival initially recorded the Dumnonii, but later reported on the Cornovii, who were possibly a sub-group of the Dumnonii. Although the Romans colonised much of central and southern Britain, Dumnonia was "virtually unaffected" by the conquest; Roman rule had little or no impact on the region, meaning it could flourish as a semi- or fully independent kingdom which evidence shows was sometimes under the dominion of the kings of the Britons, and sometimes to have been governed by its own Dumnonian monarchy, either by the title of duke or king. This petty kingdom

A petty kingdom is a kingdom described as minor or "petty" (from the French 'petit' meaning small) by contrast to an empire or unified kingdom that either preceded or succeeded it (e.g. the numerous kingdoms of Anglo-Saxon England unified into t ...

shared strong linguistic, political and cultural links with Brittany

Brittany ( ) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the north-west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica in Roman Gaul. It became an Kingdom of Brittany, independent kingdom and then a Duch ...

, a peninsula on continental Europe

Continental Europe or mainland Europe is the contiguous mainland of Europe, excluding its surrounding islands. It can also be referred to ambiguously as the European continent, – which can conversely mean the whole of Europe – and, by som ...

south of Cornwall inhabited by Britons; the Cornish and Breton language

Breton (, , ; or in Morbihan) is a Southwestern Brittonic language of the Celtic languages, Celtic language group spoken in Brittany, part of modern-day France. It is the only Celtic language still widely in use on the European mainland, albei ...

s were nearly indistinguishable in this period, and both Cornwall and Brittany remain dotted with dedications to the same Celtic saint

In Christianity, Christian belief, a saint is a person who is recognized as having an exceptional degree of sanctification in Christianity, holiness, imitation of God, likeness, or closeness to God in Christianity, God. However, the use of the ...

s.

The Sack of Rome in the year 410 prompted a complete Roman departure from Britain, and Cornwall then experienced an influx of Celtic Christian missionaries from Ireland who had a profound effect upon the early Cornish people, their culture, faith and architecture. The ensuing decline of the Roman Empire

The fall of the Western Roman Empire, also called the fall of the Roman Empire or the fall of Rome, was the loss of central political control in the Western Roman Empire, a process in which the Empire failed to enforce its rule, and its vast ...

encouraged the Anglo-Saxon invasion of Britain

The settlement of Great Britain by Germanic peoples from continental Europe led to the development of an Anglo-Saxons, Anglo-Saxon cultural identity and a shared Germanic language—Old English—whose closest known relative is Old Frisian, s ...

. The Angles, Jutes

The Jutes ( ) were one of the Germanic people, Germanic tribes who settled in Great Britain after the end of Roman rule in Britain, departure of the Roman Britain, Romans. According to Bede, they were one of the three most powerful Germanic na ...

, Frisii

The Frisii were an ancient tribe, who were neighbours of the Roman empire in the low-lying coastal region between the Rhine and the Ems (river), Ems rivers, in what what is now the northern Netherlands. They are not mentioned in Roman records af ...

and Saxons

The Saxons, sometimes called the Old Saxons or Continental Saxons, were a Germanic people of early medieval "Old" Saxony () which became a Carolingian " stem duchy" in 804, in what is now northern Germany. Many of their neighbours were, like th ...

, Germanic peoples

The Germanic peoples were tribal groups who lived in Northern Europe in Classical antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. In modern scholarship, they typically include not only the Roman-era ''Germani'' who lived in both ''Germania'' and parts of ...

from northern Europe, established petty kingdoms and settled in different regions of what was to become England, and parts of southern Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

, progressively defeating the Britons in battle. The Saxons of the Kingdom of Wessex

The Kingdom of the West Saxons, also known as the Kingdom of Wessex, was an Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy, kingdom in the south of Great Britain, from around 519 until Alfred the Great declared himself as King of the Anglo-Saxons in 886.

The Anglo-Sa ...

in particular were expanding their territory westwards towards Cornwall. The Cornish were frequently embattled with the West Saxons, who used their Germanic word ''walha

*''Walhaz'' is a reconstructed Proto-Germanic language, Proto-Germanic word meaning 'foreigner', or more specifically 'Roman', 'Romance-speaker' or '(romanized) Celt', and survives in the English words of 'Wales/Welsh people, Welsh' and 'Corn ...

'' (modern English: Welsh) meaning "stranger" or "foreigner", to describe their opponents, later specifying them as the ''Westwalas'' (West Welsh) or ''Cornwalas'' (the Cornish). Conflict continued until King Athelstan of England determined that the River Tamar

The Tamar (; ) is a river in south west England that forms most of the border between Devon (to the east) and Cornwall (to the west). A large part of the valley of the Tamar is protected as the Tamar Valley National Landscape (an Area of Outsta ...

be the formal boundary between the West Saxons and the Cornish in the year 936, making Cornwall one of the last retreats of the Britons encouraging the development of a distinct Cornish identity; Brittonic culture in Britain became confined to Cornwall, parts of Devon

Devon ( ; historically also known as Devonshire , ) is a ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by the Bristol Channel to the north, Somerset and Dorset to the east, the English Channel to the south, and Cornwall to the west ...

, North West England

North West England is one of nine official regions of England and consists of the ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial counties of Cheshire, Cumbria, Greater Manchester, Lancashire and Merseyside. The North West had a population of 7,4 ...

, South West Scotland and Wales

Wales ( ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by the Irish Sea to the north and west, England to the England–Wales border, east, the Bristol Channel to the south, and the Celtic ...

. Although a treaty was agreed, Anglo-Saxon political influence stretched westwards until some time in the late 10th century when "Cornwall was definitively incorporated into the Kingdom of England

The Kingdom of England was a sovereign state on the island of Great Britain from the late 9th century, when it was unified from various Heptarchy, Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, until 1 May 1707, when it united with Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland to f ...

".

Anglicisation and rebellion

Norman conquest of England

The Norman Conquest (or the Conquest) was the 11th-century invasion and occupation of England by an army made up of thousands of Normans, Norman, French people, French, Flemish people, Flemish, and Bretons, Breton troops, all led by the Du ...

, which began with an invasion by the troops of William, Duke of Normandy (later, King William I of England

William the Conqueror (Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 33– 9 September 1087), sometimes called William the Bastard, was the first Norman king of England (as William I), reigning from 1066 until his death. A descendant of Rollo, he was ...

) in 1066, resulted in the removal of the Anglo-Saxon derived monarchy, aristocracy, and clerical hierarchy and its replacement by Normans

The Normans (Norman language, Norman: ''Normaunds''; ; ) were a population arising in the medieval Duchy of Normandy from the intermingling between Norsemen, Norse Viking settlers and locals of West Francia. The Norse settlements in West Franc ...

, Scandinavian Vikings from northern France. and their Breton allies, who, in many cases, maintained rule in the Brittonic-speaking parts of the conquered lands. The shire

Shire () is a traditional term for an administrative division of land in Great Britain and some other English-speaking countries. It is generally synonymous with county (such as Cheshire and Worcestershire). British counties are among the oldes ...

s of England were progressively divided amongst the companions of William I of England, who served as England's new nobility. The English would come to absorb the Normans, but the Cornish vigorously resisted their influence. At the time of the conquest, legend has it that Cornwall was under the governance of Condor

Condor is the common name for two species of New World vultures, each in a monotypic genus. The name derives from the Quechua language, Quechua ''kuntur''. They are the largest flying land birds in the Western Hemisphere.

One species, the And ...

, reported by later antiquarian

An antiquarian or antiquary () is an aficionado or student of antiquities or things of the past. More specifically, the term is used for those who study history with particular attention to ancient artefacts, archaeological and historic si ...

s to be the last Earl of Cornwall to be directly descended from the ancient monarchy of Cornwall. The Earldom of Cornwall

The title of Earl of Cornwall was created several times in the Peerage of England before 1337, when it was superseded by the title Duke of Cornwall, which became attached to heirs-apparent to the throne.

Condor of Cornwall

*Condor of Cornwall, ...

had held devolved

Devolution is the statutory delegation of powers from the central government of a sovereign state to govern at a subnational level, such as a regional or local level. It is a form of administrative decentralization. Devolved territories ...

semi-sovereignty

Sovereignty can generally be defined as supreme authority. Sovereignty entails hierarchy within a state as well as external autonomy for states. In any state, sovereignty is assigned to the person, body or institution that has the ultimate au ...

from England, but in 1067 was granted to Robert, Count of Mortain

Robert, Count of Mortain, first Earl of Cornwall of 2nd creation (–) was a Norman nobleman and the half-brother (on their mother's side) of King William the Conqueror. He was one of the very few proven companions of William the Conqueror at t ...

, King William I's half-brother, and ruled thereafter by an Anglo-Norman aristocracy; in the ''Domesday Book

Domesday Book ( ; the Middle English spelling of "Doomsday Book") is a manuscript record of the Great Survey of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086 at the behest of William the Conqueror. The manuscript was originally known by ...

'', the record of the great survey of England completed in 1086, "virtually all" landowners in Cornwall "had English names, making it impossible to be sure who was Cornish and who was English by race".. However, there was a persistent and "continuing differentiation" between the English and Cornish peoples during the Middle Ages, as evidenced by documents such as the 1173 charter

A charter is the grant of authority or rights, stating that the granter formally recognizes the prerogative of the recipient to exercise the rights specified. It is implicit that the granter retains superiority (or sovereignty), and that the ...

of Truro

Truro (; ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and civil parish in Cornwall, England; it is the southernmost city in the United Kingdom, just under west-south-west of Charing Cross in London. It is Cornwall's county town, s ...

which made explicit mention of both peoples as distinct.

The Earldom of Cornwall passed to various English nobles

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy. It is normally appointed by and ranked immediately below royalty. Nobility has often been an estate of the realm with many exclusive functions and characteristics. T ...

throughout the High Middle Ages

The High Middle Ages, or High Medieval Period, was the periodization, period of European history between and ; it was preceded by the Early Middle Ages and followed by the Late Middle Ages, which ended according to historiographical convention ...

, but in 1337 the earldom was given the status of a duchy

A duchy, also called a dukedom, is a country, territory, fiefdom, fief, or domain ruled by a duke or duchess, a ruler hierarchically second to the king or Queen regnant, queen in Western European tradition.

There once existed an important differe ...

, and Edward, the Black Prince

Edward of Woodstock (15 June 1330 – 8 June 1376), known as the Black Prince, was the eldest son and heir apparent of King Edward III of England. He died before his father and so his son, Richard II of England, Richard II, succession to the Br ...

, the first son and heir of King Edward III of England

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring royal authority after t ...

, became the first Duke of Cornwall

Duke of Cornwall () is a title in the Peerage of England, traditionally held by the eldest son of the reigning Monarchy of the United Kingdom, British monarch, previously the English monarch. The Duchy of Cornwall was the first duchy created i ...

as a means for the prince to raise his own capital. Large parts of Cornwall were owned by Edward, 1st Duke of Cornwall, and successive English Dukes of Cornwall became the largest landowners in Cornwall; The monarchy of England

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the form of government used by the United Kingdom by which a hereditary monarch reigns as the head of state, with their powers regulated by the British cons ...

established two special administrative institutions in Cornwall, the first being the Duchy of Cornwall

A duchy, also called a dukedom, is a country, territory, fief, or domain ruled by a duke or duchess, a ruler hierarchically second to the king or queen in Western European tradition.

There once existed an important difference between "sovereign ...

(one of only two in the Kingdom of England) and the second being the Cornish Stannary Courts and Parliaments (which governed Cornwall's tin industry). These two institutions allowed "ordinary Cornish people to believe that they had been granted a unique constitutional status to reflect their unique cultural identity". However, the Duchy of Cornwall gradually lost its political autonomy from England, a state which became increasingly centralised in London, and by the early-Tudor period

In England and Wales, the Tudor period occurred between 1485 and 1603, including the Elizabethan era during the reign of Elizabeth I (1558–1603). The Tudor period coincides with the dynasty of the House of Tudor in England, which began with ...

the Cornish had begun to see themselves as "a conquered people whose culture, liberties, and prosperity had been downgraded by the English". This view was exacerbated in the 1490s by heavy taxation imposed by King Henry VII of England

Henry VII (28 January 1457 – 21 April 1509), also known as Henry Tudor, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from his seizure of the crown on 22 August 1485 until his death in 1509. He was the first monarch of the House of Tudor.

Henr ...

upon the impoverished Cornish to raise funds for his military campaigns against King James IV of Scotland

James IV (17 March 1473 – 9 September 1513) was List of Scottish monarchs, King of Scotland from 11 June 1488 until his death at the Battle of Flodden in 1513. He inherited the throne at the age of fifteen on the death of his father, James I ...

and Perkin Warbeck

Perkin Warbeck ( – 23 November 1499) was a pretender to the English throne claiming to be Richard of Shrewsbury, Duke of York, who was the second son of Edward IV and one of the so-called "Princes in the Tower". Richard, were he alive, would ...

,. as well as Henry VII's suspension of the privileges of the Cornish Stannaries. Having provided "more than their fair share of soldiers and sailors" for the conflict in northern England

Northern England, or the North of England, refers to the northern part of England and mainly corresponds to the Historic counties of England, historic counties of Cheshire, Cumberland, County Durham, Durham, Lancashire, Northumberland, Westmo ...

, and feeling aggrieved at "Cornwall's status as England's poorest county", a popular uprising out of Cornwall ensued—the Cornish rebellion of 1497. The rebellion was initially a political march from St Keverne

St Keverne () is a civil parishes in England, civil parish and village on The Lizard in Cornwall, England, United Kingdom.

In addition to the parish, an electoral ward exists called ''St Keverne and Meneage''. This stretches to the western Liz ...

to London led by Thomas Flamank and Michael An Gof, motivated by a "mixture of reasons"; to raise money for charity; to celebrate their community; to present their grievances to the Parliament of England

The Parliament of England was the legislature of the Kingdom of England from the 13th century until 1707 when it was replaced by the Parliament of Great Britain. Parliament evolved from the Great Council of England, great council of Lords Spi ...

, but gathered pace across the West Country

The West Country is a loosely defined area within southwest England, usually taken to include the counties of Cornwall, Devon, Dorset, Somerset and Bristol, with some considering it to extend to all or parts of Wiltshire, Gloucestershire and ...

as a revolt against the king.

Cornish was the most widely spoken language west of the River Tamar until around the mid-1300s, when Middle English

Middle English (abbreviated to ME) is a form of the English language that was spoken after the Norman Conquest of 1066, until the late 15th century. The English language underwent distinct variations and developments following the Old English pe ...

began to be adopted as a common language of the Cornish people. As late as 1542 Andrew Boorde, an English traveller, physician and writer, wrote that in Cornwall there were two languages, "Cornysshe" and "Englysshe", but that "there may be many men and women" in Cornwall who could not understand English. While the Norman language

Norman or Norman French (, , Guernésiais: , Jèrriais: ) is a ''Langues d'oïl, langue d'oïl'' spoken in the historical region, historical and Cultural area, cultural region of Normandy.

The name "Norman French" is sometimes also used to des ...

was in use by much of the English aristocracy, Cornish was used as a ''lingua franca

A lingua franca (; ; for plurals see ), also known as a bridge language, common language, trade language, auxiliary language, link language or language of wider communication (LWC), is a Natural language, language systematically used to make co ...

'', particularly in the remote far west of Cornwall. Many Cornish landed gentry

The landed gentry, or the gentry (sometimes collectively known as the squirearchy), is a largely historical Irish and British social class of landowners who could live entirely from rental income, or at least had a country estate. It is t ...

chose mottos in the Cornish language for their coat of arms

A coat of arms is a heraldry, heraldic communication design, visual design on an escutcheon (heraldry), escutcheon (i.e., shield), surcoat, or tabard (the last two being outer garments), originating in Europe. The coat of arms on an escutcheon f ...

, highlighting its socially high status.. However, in 1549 and following the English Reformation

The English Reformation began in 16th-century England when the Church of England broke away first from the authority of the pope and bishops Oath_of_Supremacy, over the King and then from some doctrines and practices of the Catholic Church ...

, King Edward VI of England

Edward VI (12 October 1537 – 6 July 1553) was King of England and King of Ireland, Ireland from 28 January 1547 until his death in 1553. He was crowned on 20 February 1547 at the age of nine. The only surviving son of Henry VIII by his thi ...

commanded that the Book of Common Prayer

The ''Book of Common Prayer'' (BCP) is the title given to a number of related prayer books used in the Anglican Communion and by other Christianity, Christian churches historically related to Anglicanism. The Book of Common Prayer (1549), fi ...

, an Anglican

Anglicanism, also known as Episcopalianism in some countries, is a Western Christianity, Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the ...

liturgical text in the English language, should be introduced to all churches in his kingdom, meaning that Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

and Celtic customs and services should be discontinued. The Prayer Book Rebellion

The Prayer Book Rebellion or Western Rising was a popular revolt in Cornwall and Devon in 1549. In that year, the Book of Common Prayer (1549), first ''Book of Common Prayer'', presenting the theology of the English Reformation, was introduce ...

was a militant revolt in Cornwall and parts of neighbouring Devon

Devon ( ; historically also known as Devonshire , ) is a ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by the Bristol Channel to the north, Somerset and Dorset to the east, the English Channel to the south, and Cornwall to the west ...

against the Act of Uniformity 1549, which outlawed all languages from church services apart from English,. and is specified as a testament to the affection and loyalty the Cornish people held for the Cornish language. In the rebellion, separate risings occurred simultaneously in Bodmin

Bodmin () is a town and civil parish in Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. It is situated south-west of Bodmin Moor.

The extent of the civil parish corresponds fairly closely to that of the town so is mostly urban in character. It is bordered ...

in Cornwall, and Sampford Courtenay in Devon—which would both converge at Exeter

Exeter ( ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and the county town of Devon in South West England. It is situated on the River Exe, approximately northeast of Plymouth and southwest of Bristol.

In Roman Britain, Exeter w ...

, laying siege to the region's largest Protestant city. However, the rebellion was suppressed, thanks largely to the aid of foreign mercenaries in a series of battles in which "hundreds were killed", effectively ending Cornish as the common language of the Cornish people. The Anglicanism of the Reformation served as a vehicle for Anglicisation in Cornwall; Protestantism had a lasting cultural effect upon the Cornish by way of linking Cornwall more closely with England, while lessening political and linguistic ties with the Bretons

The Bretons (; or , ) are an ethnic group native to Brittany, north-western France. Originally, the demonym designated groups of Common Brittonic, Brittonic speakers who emigrated from Dumnonia, southwestern Great Britain, particularly Cornwal ...

of Brittany..

The English Civil War

The English Civil War or Great Rebellion was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Cavaliers, Royalists and Roundhead, Parliamentarians in the Kingdom of England from 1642 to 1651. Part of the wider 1639 to 1653 Wars of th ...

, a series of armed conflicts and political machinations between Parliamentarians and Royalists, polarised the populations of England and Wales. However, Cornwall in the English Civil War was a staunchly Royalist enclave, an "important focus of support for the Royalist cause".. Cornish soldiers were used as scouts and spies during the war, for their language was not understood by English Parliamentarians. The peace that followed the close of the war led to a further shift to the English language by the Cornish people, which encouraged an influx of English people to Cornwall. By the mid-17th century the use of the Cornish language had retreated far enough west to prompt concern and investigation by antiquarian

An antiquarian or antiquary () is an aficionado or student of antiquities or things of the past. More specifically, the term is used for those who study history with particular attention to ancient artefacts, archaeological and historic si ...

s, such as William Scawen. As the Cornish language diminished the people of Cornwall underwent a process of English enculturation

Enculturation is the process by which people learn the dynamics of their surrounding culture and acquire values and norms appropriate or necessary to that culture and its worldviews.

Definition and history of research

The term enculturation ...

and assimilation, becoming "absorbed into the mainstream of English life".

Industry, revival and the modern period

The

The Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution, sometimes divided into the First Industrial Revolution and Second Industrial Revolution, was a transitional period of the global economy toward more widespread, efficient and stable manufacturing processes, succee ...

had a major impact upon the Cornish people. Cornwall's economy was fully integrated into England's,. and mining in Cornwall

Mining in Cornwall and Devon, in the southwest of Britain, is thought to have begun in the early-middle Bronze Age with the exploitation of cassiterite. Tin, and later copper, were the most commonly extracted metals. Some tin mining continued ...

, always an important source of employment and stability of the Cornish, experienced a process of industrialisation resulting in 30 per cent of Cornwall's adult population being employed by its mines. During this period, efforts were made by Cornish engineers to design steam engine

A steam engine is a heat engine that performs Work (physics), mechanical work using steam as its working fluid. The steam engine uses the force produced by steam pressure to push a piston back and forth inside a Cylinder (locomotive), cyl ...

s with which to power water pumps for Cornish mines thus aiding the extraction of mineral ore. Industrial scale tin and copper mining operations in Cornwall melded Cornish identity with engines and heavy industry,. and Cornwall's leading mining engineer

Mining engineering is the extraction of minerals from the ground. It is associated with many other disciplines, such as mineral processing, exploration, excavation, geology, metallurgy, geotechnical engineering and surveying. A mining engineer m ...

, Richard Trevithick

Richard Trevithick (13 April 1771 – 22 April 1833) was a British inventor and mining engineer. The son of a mining captain, and born in the mining heartland of Cornwall, Trevithick was immersed in mining and engineering from an early age. He ...

, became "as much a part of Cornwall's heritage as any legendary giant from its Celtic past". Trevithick's most significant success was a high-pressure steam engine used to pump water and refuse from mines, but he was also the builder of the first full-scale working railway steam locomotive

A steam locomotive is a locomotive that provides the force to move itself and other vehicles by means of the expansion of steam. It is fuelled by burning combustible material (usually coal, Fuel oil, oil or, rarely, Wood fuel, wood) to heat ...

. On 21 February 1804, the world's first locomotive-hauled railway journey took place as Trevithick's unnamed steam locomotive hauled a train along the tramway of the Penydarren

: ''For Trevithick's Pen-y-darren locomotive, see Richard Trevithick#"Pen-y-Darren" locomotive, Richard Trevithick.''

Penydarren is a Community (Wales), community and electoral ward in Merthyr Tydfil County Borough in Wales.

Description

The area ...

ironworks, near Merthyr Tydfil

Merthyr Tydfil () is the main town in Merthyr Tydfil County Borough, Wales, administered by Merthyr Tydfil County Borough Council. It is about north of Cardiff. Often called just Merthyr, it is said to be named after Tydfil, daughter of K ...

in Wales.

The construction of the Great Western Railway

The Great Western Railway (GWR) was a History of rail transport in Great Britain, British railway company that linked London with the southwest, west and West Midlands (region), West Midlands of England and most of Wales. It was founded in 1833, ...

during the Victorian era

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the reign of Queen Victoria, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. Slightly different definitions are sometimes used. The era followed the ...

allowed for an influx of tourists to Cornwall from across Great Britain. Well into the Edwardian era

In the United Kingdom, the Edwardian era was a period in the early 20th century that spanned the reign of King Edward VII from 1901 to 1910. It is commonly extended to the start of the First World War in 1914, during the early reign of King Ge ...

and interwar period

In the history of the 20th century, the interwar period, also known as the interbellum (), lasted from 11 November 1918 to 1 September 1939 (20 years, 9 months, 21 days) – from the end of World War I (WWI) to the beginning of World War II ( ...

, Cornwall was branded as a rural retreat, a "primitive land of magic and romance", and as an "earlier incarnation of Englishness, a place more English than an England ravaged by modernity".. Cornwall, the United Kingdom's only region with a subtropical-like climate, became a centre for English tourism, its coastline dominated by resort town

A resort town, resort city or resort destination is an urban area where tourism or vacationing is the primary component of the local culture and economy. A typical resort town has one or more actual resorts in the surrounding area. Sometimes ...

s increasingly composed of bungalow

A bungalow is a small house or cottage that is typically single or one and a half storey, if a smaller upper storey exists it is frequently set in the roof and Roof window, windows that come out from the roof, and may be surrounded by wide ve ...

s and villa

A villa is a type of house that was originally an ancient Roman upper class country house that provided an escape from urban life. Since its origins in the Roman villa, the idea and function of a villa have evolved considerably. After the f ...

s. John Nichols Thom, or Mad Tom, (1799 – 31 May 1838) was a Cornishman self-declared messiah who, in the 19th century led the last battle to be fought on English soil, known as the Battle of Bossenden Wood. While not akin to the Cornish rebellions of the past, he did attract some Cornish support as well as mostly Kentish labourers, although his support was primarily of religious followers.

In the latter half of the 19th century Cornwall experienced rapid deindustrialisation, with the closure of mines in particular considered by the Cornish to be both an economic and cultural disaster. This, coupled with the rise of Romantic nationalism

Romantic nationalism (also national romanticism, organic nationalism, identity nationalism) is the form of nationalism in which the state claims its political legitimacy as an organic consequence of the unity of those it governs. This includes ...

in Europe inspired and influenced a Celtic Revival

The Celtic Revival (also referred to as the Celtic Twilight) is a variety of movements and trends in the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries that see a renewed interest in aspects of Celtic culture. Artists and writers drew on the traditions of Gae ...

in Cornwall, a social, linguistic and artistic movement interested in Cornish medieval ethnology

Ethnology (from the , meaning 'nation') is an academic field and discipline that compares and analyzes the characteristics of different peoples and the relationships between them (compare cultural, social, or sociocultural anthropology).

Sci ...

. This Revivalist upsurge investigated Cornwall's pre-industrial culture, using the Cornish language as the "principal badge of ornishnationality and ethnic kinship". The first effective revival of Cornish began in 1904 when Henry Jenner

Henry Jenner (8 August 1848 – 8 May 1934) was a British scholar of the Celtic languages, a Cornwall, Cornish cultural activist, and the chief originator of the Cornish language revival.

Jenner was born at St Columb Major on 8 August 1848. H ...

, a Celtic language enthusiast, published his book ''Handbook of the Cornish Language''. His orthography

An orthography is a set of convention (norm), conventions for writing a language, including norms of spelling, punctuation, Word#Word boundaries, word boundaries, capitalization, hyphenation, and Emphasis (typography), emphasis.

Most national ...

, Unified Cornish

Unified Cornish (UC) (''Kernewek Uny '', ''KU'') is a variety of the Cornish language

Cornish (Standard Written Form: or , ) is a Southwestern Brittonic language, Southwestern Brittonic language of the Celtic language family. Along with We ...

, was based on Cornish as it was spoken in the 18th century, although his pupil Robert Morton Nance later steered the revival more towards the Middle Cornish that had been used in the 16th century, before the language became influenced by English.

The visit of King George IV to Scotland

George IV's visit to Scotland in 1822 was the first visit of a reigning monarch to Scotland in nearly two centuries, the last being by Charles II of England, Charles II for Scottish coronation of Charles II, his Scottish coronation in 1651. Gove ...

in 1822 reinvigorated Scottish national identity

Scottish national identity, including Scottish nationalism, are terms referring to the sense of national identity as embodied in the shared and characteristic culture of Scotland, culture, Languages of Scotland, languages, and :Scottish traditi ...

, melding it with romanticist notions of tartan

Tartan or plaid ( ) is a patterned cloth consisting of crossing horizontal and vertical bands in multiple colours, forming repeating symmetrical patterns known as ''setts''. Originating in woven wool, tartan is most strongly associated wi ...

, kilt

A kilt ( ) is a garment resembling a wrap-around knee-length skirt, made of twill-woven worsted wool with heavy pleats at the sides and back and traditionally a tartan pattern. Originating in the Scottish Highland dress for men, it is first r ...

s and the Scottish Highlands

The Highlands (; , ) is a historical region of Scotland. Culturally, the Highlands and the Scottish Lowlands, Lowlands diverged from the Late Middle Ages into the modern period, when Scots language, Lowland Scots language replaced Scottish Gae ...

.. As Pan-Celticism gathered pace in the early 20th century, Cornishman L. C. R. Duncombe-Jewell and the Cowethas Kelto-Kernuak (a Cornish language interest group) asserted the use of Cornish kilts and tartans as a "national dress ... common to all Celtic countries". In 1924 the Federation of Old Cornwall Societies

The Federation of Old Cornwall Societies (FOCS) was formed in 1924, on the initiative of Robert Morton Nance, with the objective of collecting and maintaining "all those ancient things that make the spirit of Cornwall — its traditions, its old ...

was formed to facilitate, preserve and maintain Celticity in Cornwall, followed by the similar Gorseth Kernow in 1928, and the formation of the Cornish nationalist political party Mebyon Kernow

Mebyon Kernow – The Party for Cornwall (, MK; Cornish language, Cornish for ''Sons of Cornwall'') is a Cornish nationalism, Cornish nationalist, Left-wing politics, centre-left political party in Cornwall, in southwestern Britain. It currentl ...

in 1951. Increased interest and communication across the Celtic nations

The Celtic nations or Celtic countries are a cultural area and collection of geographical regions in Northwestern Europe where the Celtic languages and cultural traits have survived. The term ''nation'' is used in its original sense to mean a ...

in Celtic languages and culture during the 1960s and 1970s spurred on the popularisation of the Cornish self-government movement. Since devolution

Devolution is the statutory delegation of powers from the central government of a sovereign state to govern at a subnational level, such as a regional or local level. It is a form of administrative decentralization. Devolved territori ...

in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, enthusiasts for Cornish culture have pressed for the Cornish language to be taught formally in Cornish schools, while Cornish nationalists have demanded greater political autonomy for Cornwall, for example that it be constituted as the United Kingdom's fifth constituent country with its own Cornish Assembly

A Cornish Assembly () is a proposed devolved law-making assembly for Cornwall along the lines of the Scottish Parliament, the Senedd (Welsh Parliament) and the Northern Ireland Assembly in the United Kingdom.

The campaign for Cornish devolut ...

.

Geographic distribution

The Cornish people are concentrated in Cornwall, but after the

The Cornish people are concentrated in Cornwall, but after the Age of Discovery

The Age of Discovery (), also known as the Age of Exploration, was part of the early modern period and overlapped with the Age of Sail. It was a period from approximately the 15th to the 17th century, during which Seamanship, seafarers fro ...

in the early modern period were involved in the British colonisation of the Americas

The British colonization of the Americas is the history of establishment of control, settlement, and colonization of the continents of the Americas by England, Scotland, and, after 1707, Great Britain. Colonization efforts began in the late 16 ...

and other transcontinental and transatlantic migrations. Initially, the number of migrants was comparatively small, with those who left Cornwall typically settling in North America or else amongst the ports and plantation

Plantations are farms specializing in cash crops, usually mainly planting a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. Plantations, centered on a plantation house, grow crops including cotton, cannabis, tob ...

s of the Caribbean

The Caribbean ( , ; ; ; ) is a region in the middle of the Americas centered around the Caribbean Sea in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, mostly overlapping with the West Indies. Bordered by North America to the north, Central America ...

.

In the first half of the 19th century, the Cornish people were leaders in tin

Tin is a chemical element; it has symbol Sn () and atomic number 50. A silvery-colored metal, tin is soft enough to be cut with little force, and a bar of tin can be bent by hand with little effort. When bent, a bar of tin makes a sound, the ...

and copper smelting, while mining in Cornwall

Mining in Cornwall and Devon, in the southwest of Britain, is thought to have begun in the early-middle Bronze Age with the exploitation of cassiterite. Tin, and later copper, were the most commonly extracted metals. Some tin mining continued ...

was the people's major occupation. Increased competition from Australia, British Malaya

The term "British Malaya" (; ) loosely describes a set of states on the Malay Peninsula and the island of Singapore that were brought under British Empire, British hegemony or control between the late 18th and the mid-20th century. Unlike the ...

and Bolivia

Bolivia, officially the Plurinational State of Bolivia, is a landlocked country located in central South America. The country features diverse geography, including vast Amazonian plains, tropical lowlands, mountains, the Gran Chaco Province, w ...

, coupled with the depletion of mineral deposits brought about an economic decline for Cornish mining lasting half a century, and prompting mass human migration

Human migration is the movement of people from one place to another, with intentions of settling, permanently or temporarily, at a new location (geographic region). The movement often occurs over long distances and from one country to another ( ...

from Cornwall. In each decade from 1861 to 1901, "around 20% of the Cornish male population migrated abroad"—three times that of the average of England and Wales

England and Wales () is one of the Law of the United Kingdom#Legal jurisdictions, three legal jurisdictions of the United Kingdom. It covers the constituent countries England and Wales and was formed by the Laws in Wales Acts 1535 and 1542. Th ...

—and totalling over a quarter of a million people lost to emigration between 1841 and 1901. There was a displacement of skilled Cornish engineers, farmers, merchants, miners and tradesmen, but their commercial and occupational expertise, particularly in hard rock mining, was highly valued by the communities they met. Within Great Britain, Cornish families were attracted from Cornwall to North East England

North East England, commonly referred to simply as the North East within England, is one of nine official regions of England. It consists of County DurhamNorthumberland, , Northumberland, Tyne and Wear and part of northern North Yorkshire. ...

—particularly on Teesside

Teesside () is an urban area around the River Tees in North East England. Straddling the border between County Durham and North Yorkshire, it spans the boroughs of Borough of Middlesbrough, Middlesbrough, Borough of Stockton-on-Tees, Stockton ...

—to partake in coal mining as a means to earn wealth by using their mining skill. This has resulted in a concentration of Cornish names on and around Teesside that persists into the 21st century.