Paul Kruger (actor) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

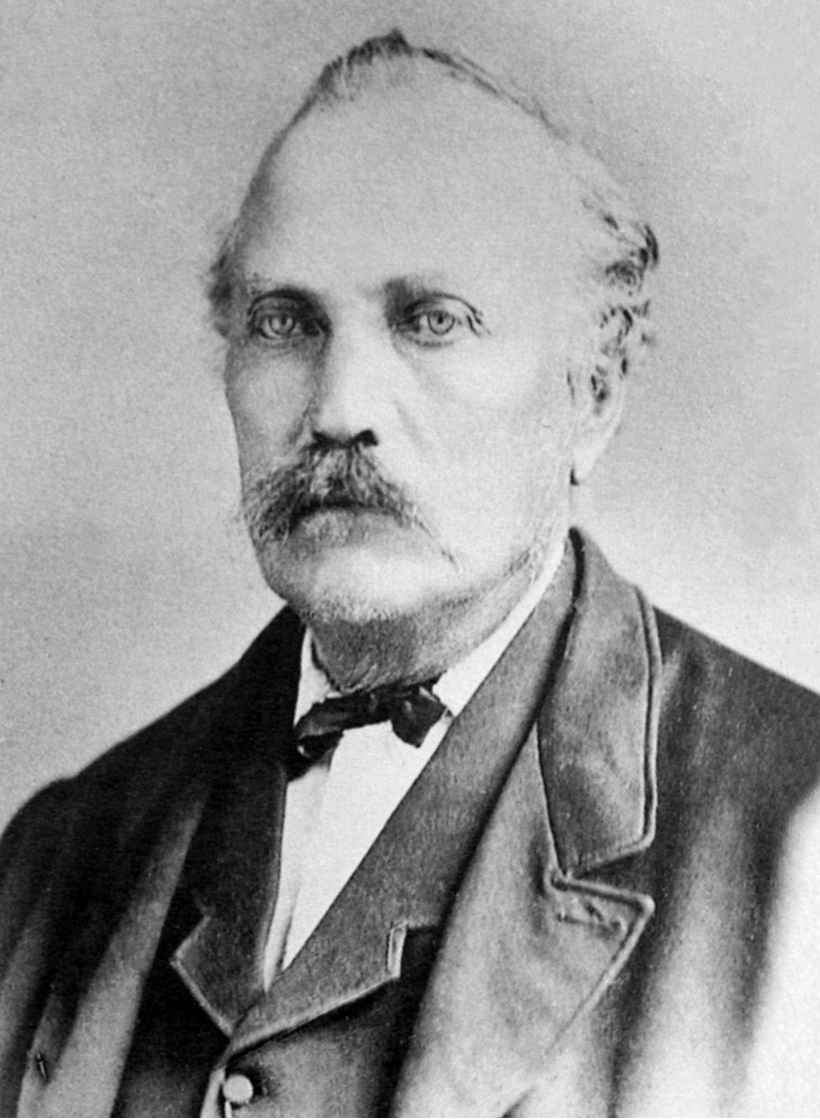

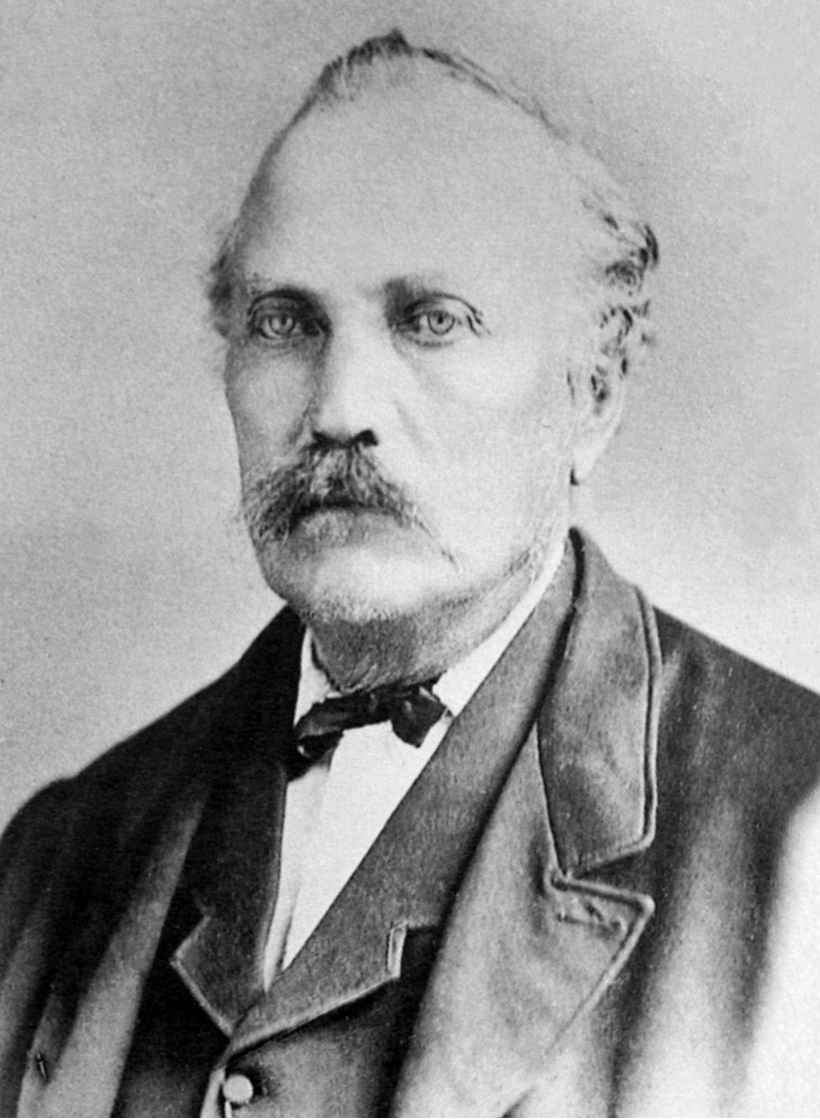

Stephanus Johannes Paulus Kruger (; 10 October 1825 – 14 July 1904), better known as Paul Kruger, was a South African politician. He was one of the dominant political and military figures in 19th-century

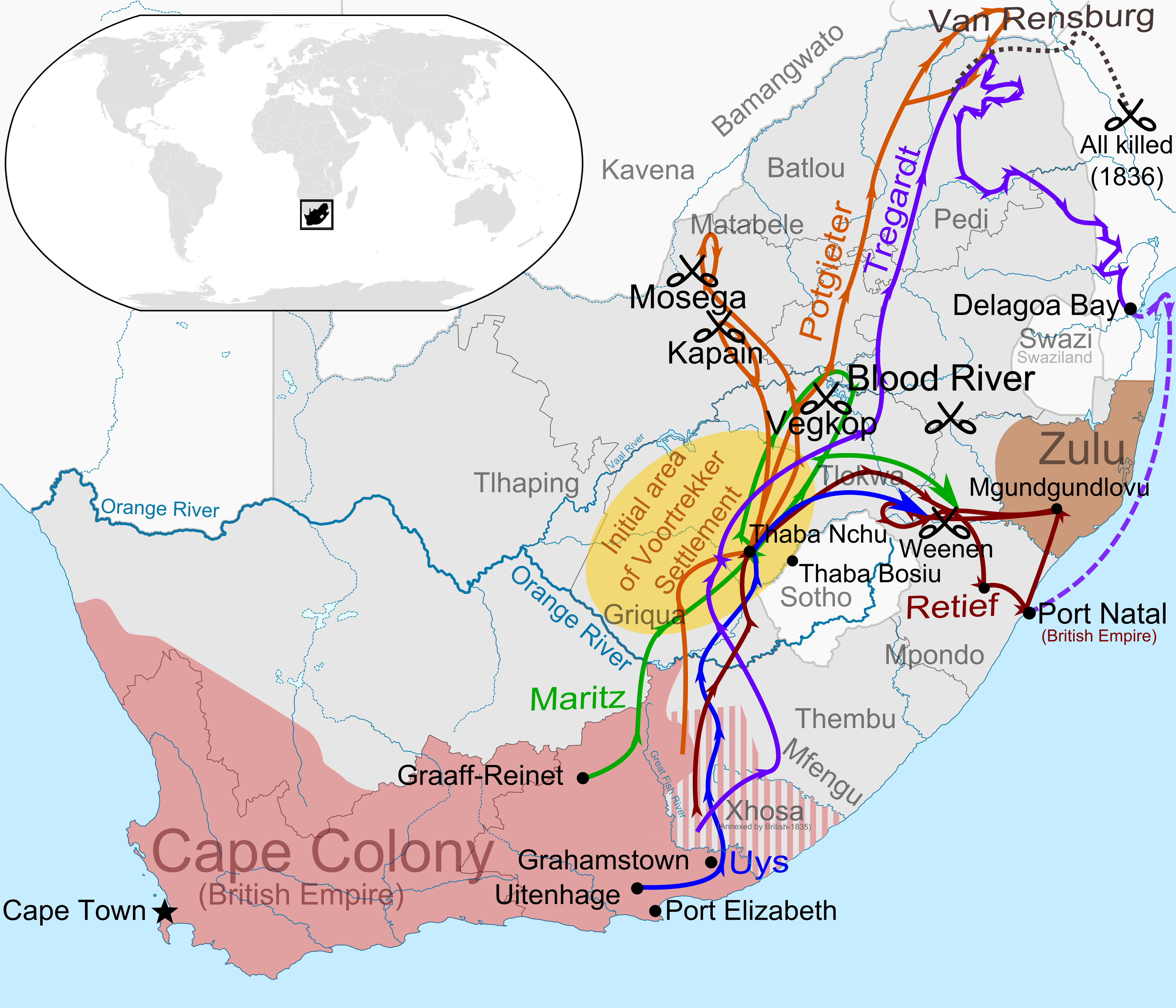

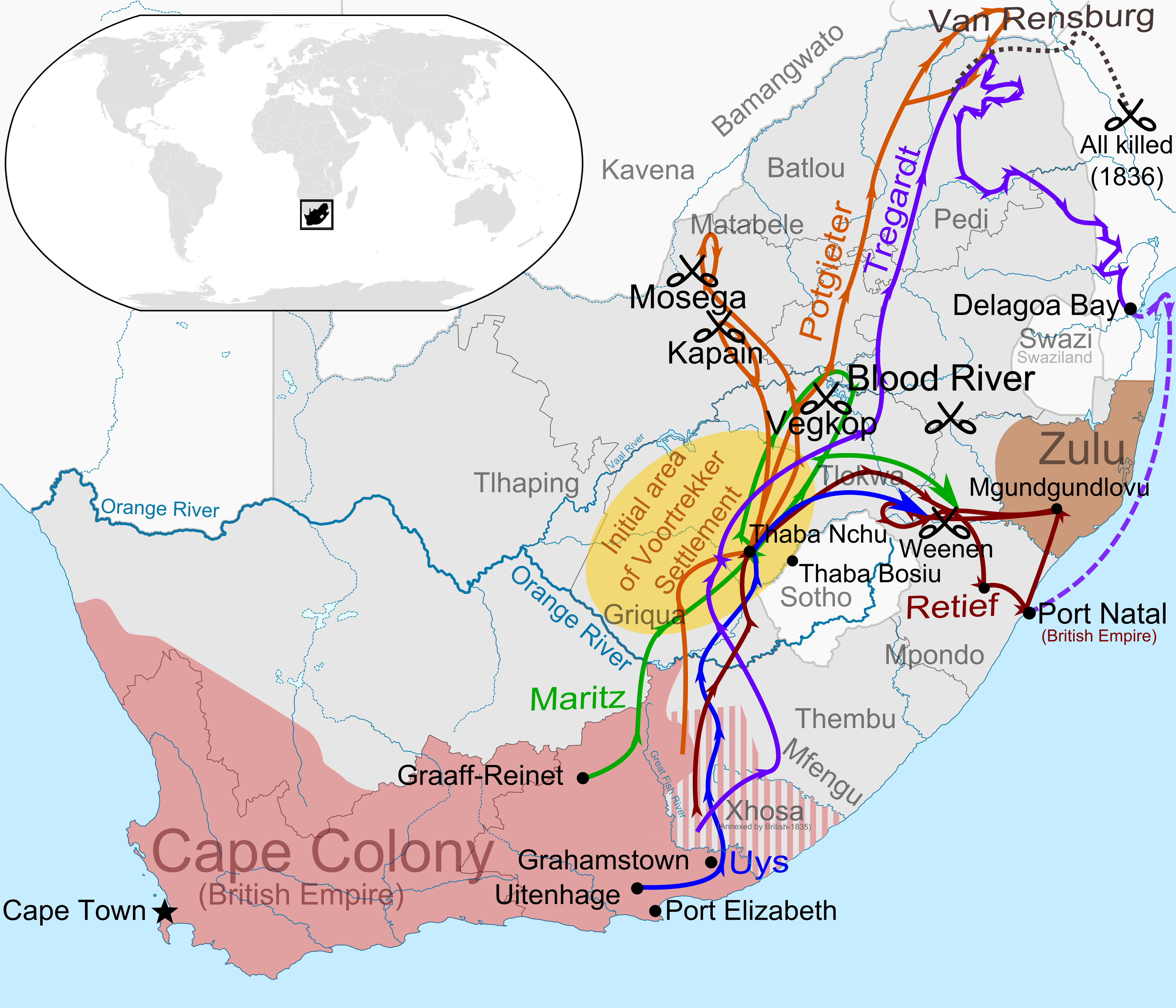

In 1834 Casper Kruger, his father, and his brothers Gert and Theuns moved their families east and set up farms near the

In 1834 Casper Kruger, his father, and his brothers Gert and Theuns moved their families east and set up farms near the

Britain annexed the Voortrekkers' short-lived

Britain annexed the Voortrekkers' short-lived

The Boer colonists and the local

The Boer colonists and the local

Marthinus Pretorius hoped to achieve either federation or amalgamation with the Orange Free State, but before he could contemplate this he would have to unite the Transvaal. In 1855 he appointed an eight-man constitutional commission, including Kruger, which presented a draft constitution in September that year. Lydenburg and Zoutpansberg rejected the proposals, calling for a less centralised government. Pretorius tried again during 1856, holding meetings with eight-man commissions in Rustenburg, Potchefstroom and Pretoria, but

Marthinus Pretorius hoped to achieve either federation or amalgamation with the Orange Free State, but before he could contemplate this he would have to unite the Transvaal. In 1855 he appointed an eight-man constitutional commission, including Kruger, which presented a draft constitution in September that year. Lydenburg and Zoutpansberg rejected the proposals, calling for a less centralised government. Pretorius tried again during 1856, holding meetings with eight-man commissions in Rustenburg, Potchefstroom and Pretoria, but

Kruger and others in the Transvaal government disliked Pretorius's unconstitutional dual presidency, and worried that Britain might declare the Sand River and Orange River Conventions void if the republics joined. Pretorius was told by the Transvaal volksraad on 10 September 1860 to choose between his two posts—to the surprise of both supporters and detractors he resigned as President of the Transvaal and continued in the Free State. After Schoeman unsuccessfully attempted to forcibly supplant Grobler as Acting President, Kruger persuaded him to submit to a volksraad hearing, where Schoeman was censured and relieved of his post.

Kruger and others in the Transvaal government disliked Pretorius's unconstitutional dual presidency, and worried that Britain might declare the Sand River and Orange River Conventions void if the republics joined. Pretorius was told by the Transvaal volksraad on 10 September 1860 to choose between his two posts—to the surprise of both supporters and detractors he resigned as President of the Transvaal and continued in the Free State. After Schoeman unsuccessfully attempted to forcibly supplant Grobler as Acting President, Kruger persuaded him to submit to a volksraad hearing, where Schoeman was censured and relieved of his post.  Schoeman mustered a commando at Potchefstroom, but was routed by Kruger on the night of 9 October 1862. After Schoeman returned with a larger force Kruger and Pretorius held negotiations where it was agreed to hold a special court on the disturbances in January 1863, and soon thereafter fresh elections for president and commandant-general. Schoeman was found guilty of rebellion against the state and banished. In May the election results were announced—Van Rensburg became president, with Kruger as commandant-general. Both expressed disappointment at the low turnout and resolved to hold another set of elections. Van Rensburg's opponent this time was Pretorius, who had resigned his office in the Orange Free State and returned to the Transvaal. Turnout was higher and on 12 October the volksraad announced another Van Rensburg victory. Kruger was returned as commandant-general with a large majority. The

Schoeman mustered a commando at Potchefstroom, but was routed by Kruger on the night of 9 October 1862. After Schoeman returned with a larger force Kruger and Pretorius held negotiations where it was agreed to hold a special court on the disturbances in January 1863, and soon thereafter fresh elections for president and commandant-general. Schoeman was found guilty of rebellion against the state and banished. In May the election results were announced—Van Rensburg became president, with Kruger as commandant-general. Both expressed disappointment at the low turnout and resolved to hold another set of elections. Van Rensburg's opponent this time was Pretorius, who had resigned his office in the Orange Free State and returned to the Transvaal. Turnout was higher and on 12 October the volksraad announced another Van Rensburg victory. Kruger was returned as commandant-general with a large majority. The  In 1867, Pretoria sent Kruger to restore law and order in Zoutpansberg. He had around 500 men but very low reserves of ammunition, and discipline in the ranks was poor. On reaching Schoemansdal, which was under threat by the chief Katlakter, Kruger and his officers resolved that holding the town was impossible and ordered a general evacuation, following which Katlakter razed the town. The loss of Schoemansdal, once a prosperous settlement by Boer standards, was considered a great humiliation by many burghers. The Transvaal government formally exonerated Kruger over the matter, ruling that he had been forced to evacuate Schoemansdal by factors beyond his control, but some still argued that he had given the town up too readily. Peace returned to Zoutpansberg in 1869, following the intervention of the republic's

In 1867, Pretoria sent Kruger to restore law and order in Zoutpansberg. He had around 500 men but very low reserves of ammunition, and discipline in the ranks was poor. On reaching Schoemansdal, which was under threat by the chief Katlakter, Kruger and his officers resolved that holding the town was impossible and ordered a general evacuation, following which Katlakter razed the town. The loss of Schoemansdal, once a prosperous settlement by Boer standards, was considered a great humiliation by many burghers. The Transvaal government formally exonerated Kruger over the matter, ruling that he had been forced to evacuate Schoemansdal by factors beyond his control, but some still argued that he had given the town up too readily. Peace returned to Zoutpansberg in 1869, following the intervention of the republic's

Burgers busied himself attempting to modernise the South African Republic along European lines, hoping to set in motion a process that would lead to a united, independent South Africa. Finding Boer officialdom inadequate, he imported ministers and civil servants en masse from the Netherlands. His ascent to the presidency came shortly after the realisation that the Boer republics might stand on land of immense mineral wealth. Diamonds had been discovered in

Burgers busied himself attempting to modernise the South African Republic along European lines, hoping to set in motion a process that would lead to a united, independent South Africa. Finding Boer officialdom inadequate, he imported ministers and civil servants en masse from the Netherlands. His ascent to the presidency came shortly after the realisation that the Boer republics might stand on land of immense mineral wealth. Diamonds had been discovered in

According to Meintjes, Kruger was still not particularly anti-British; he thought the British had made a mistake and would rectify the situation if this could be proven to them. After conducting a poll through the former republican infrastructure—587 signed in favour of the annexation, 6,591 against—he organised a second deputation to London, made up of himself and Joubert with Bok again serving as secretary. The envoys met the British High Commissioner in Cape Town,

According to Meintjes, Kruger was still not particularly anti-British; he thought the British had made a mistake and would rectify the situation if this could be proven to them. After conducting a poll through the former republican infrastructure—587 signed in favour of the annexation, 6,591 against—he organised a second deputation to London, made up of himself and Joubert with Bok again serving as secretary. The envoys met the British High Commissioner in Cape Town,

In the last months of 1880, Lanyon began to pursue tax payments from burghers who were in arrears.

In the last months of 1880, Lanyon began to pursue tax payments from burghers who were in arrears.

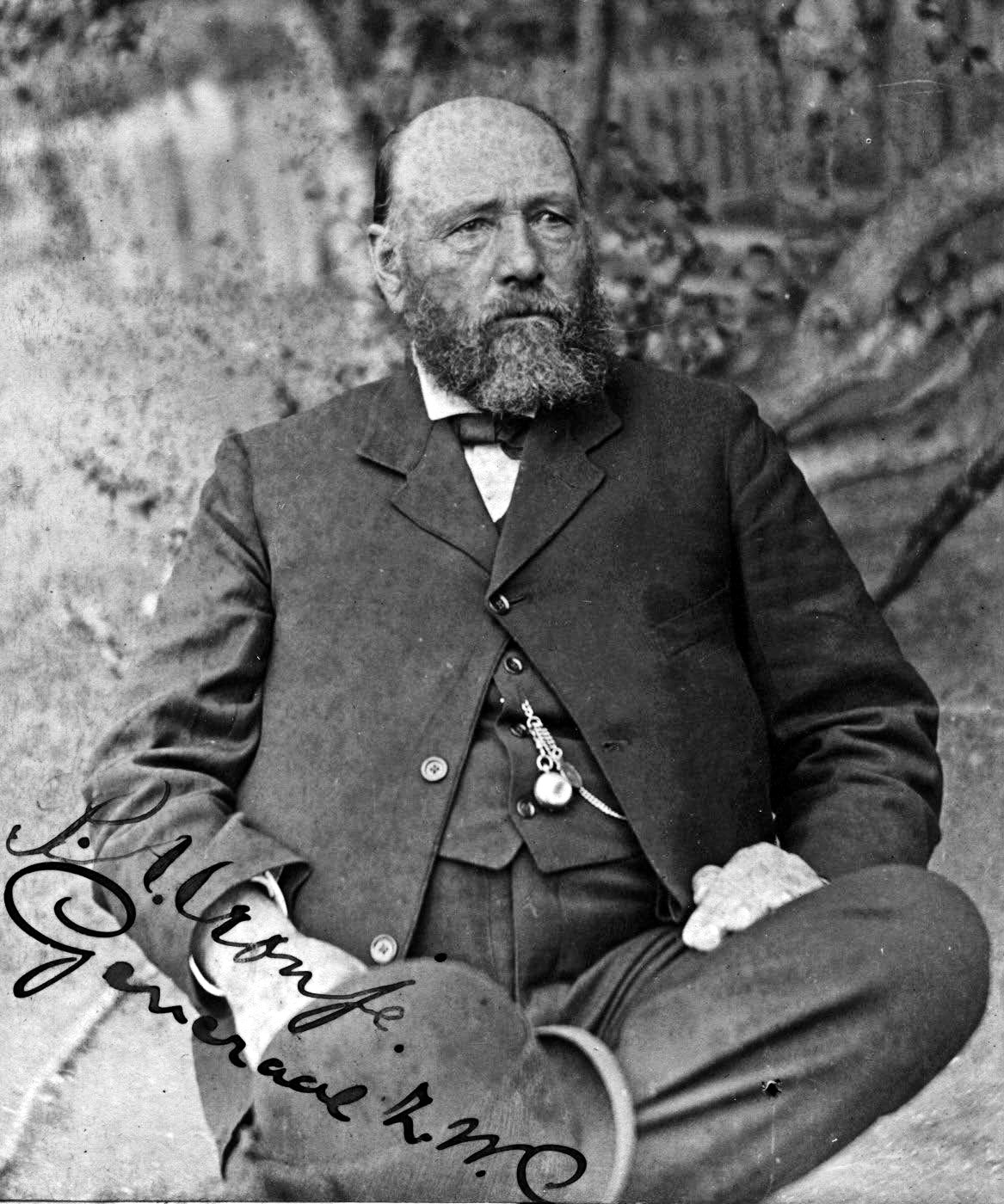

At Kruger's suggestion Joubert was elected Commandant-General of the restored republic, though he had little military experience and protested he was not suited to the position. The provisional government set up a temporary capital at

At Kruger's suggestion Joubert was elected Commandant-General of the restored republic, though he had little military experience and protested he was not suited to the position. The provisional government set up a temporary capital at

By now aged nearly 56, Kruger resolved that he could no longer travel constantly between Boekenhoutfontein and the capital, and in August 1881 he and Gezina moved to Church Street, Pretoria, from where he could easily walk to the government offices on Church Square. Also around this time he shaved off his moustache and most of his facial hair, leaving the chinstrap beard he kept thereafter. His and Gezina's permanent home on Church Street, what is now called Kruger House, would be completed in 1884.

A direct consequence of the end of British rule was an economic slump; the Transvaal government almost immediately found itself again on the verge of bankruptcy. The triumvirate spent two months discussing the terms of the Pretoria Convention with the new volksraad—approve it or go back to Laing's Nek, said Kruger—before it was finally ratified on 25 October 1881. During this time Kruger introduced tax reforms, announced the triumvirate's decision to grant industrial

By now aged nearly 56, Kruger resolved that he could no longer travel constantly between Boekenhoutfontein and the capital, and in August 1881 he and Gezina moved to Church Street, Pretoria, from where he could easily walk to the government offices on Church Square. Also around this time he shaved off his moustache and most of his facial hair, leaving the chinstrap beard he kept thereafter. His and Gezina's permanent home on Church Street, what is now called Kruger House, would be completed in 1884.

A direct consequence of the end of British rule was an economic slump; the Transvaal government almost immediately found itself again on the verge of bankruptcy. The triumvirate spent two months discussing the terms of the Pretoria Convention with the new volksraad—approve it or go back to Laing's Nek, said Kruger—before it was finally ratified on 25 October 1881. During this time Kruger introduced tax reforms, announced the triumvirate's decision to grant industrial

The deputation went on from London to mainland Europe, where according to Meintjes their reception "was beyond all expectations ... one banquet followed the other, the stand of a handful of Boers against the British Empire having caused a sensation". During a grand tour Kruger met

The deputation went on from London to mainland Europe, where according to Meintjes their reception "was beyond all expectations ... one banquet followed the other, the stand of a handful of Boers against the British Empire having caused a sensation". During a grand tour Kruger met

Much of Kruger's efforts over the next year were dedicated to attempts to acquire a sea outlet for the South African Republic. In July Pieter Grobler, who had just negotiated a treaty with King

Much of Kruger's efforts over the next year were dedicated to attempts to acquire a sea outlet for the South African Republic. In July Pieter Grobler, who had just negotiated a treaty with King

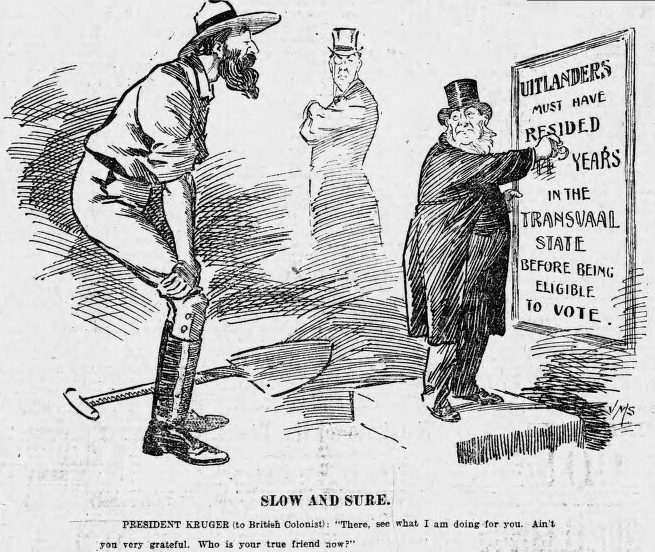

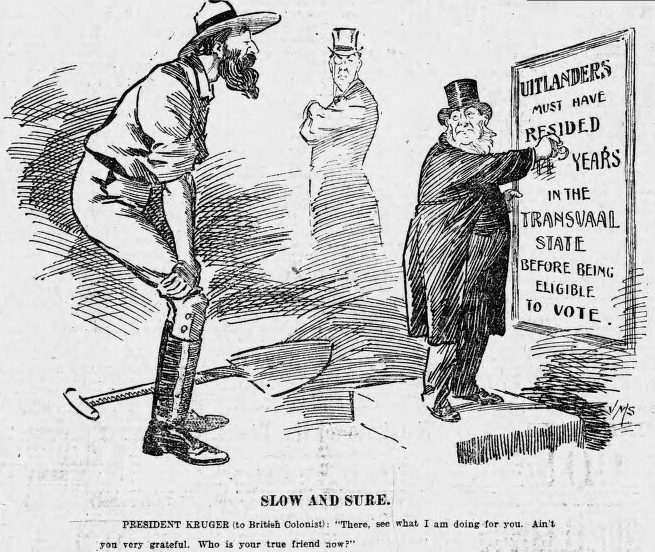

Kruger's second volksraad sat for the first time in 1891. Any resolution it passed had to be ratified by the first volksraad; its role was in effect largely advisory. Uitlanders could vote in elections for the second volksraad after two years' residency on the condition they were

Kruger's second volksraad sat for the first time in 1891. Any resolution it passed had to be ratified by the first volksraad; its role was in effect largely advisory. Uitlanders could vote in elections for the second volksraad after two years' residency on the condition they were  Kruger was by this time widely perceived as a personification of Afrikanerdom both at home and abroad. When he stopped going to the government offices at the Raadsaal by foot and began to be conveyed there by a presidential

Kruger was by this time widely perceived as a personification of Afrikanerdom both at home and abroad. When he stopped going to the government offices at the Raadsaal by foot and began to be conveyed there by a presidential

The following year the National Union sent Kruger a petition bearing 38,500 signatures requesting electoral reform. Kruger dismissed all such entreaties with the assertion that enfranchising "these new-comers, these disobedient persons" might imperil the republic's independence. "Protest!" he shouted at one uitlander deputation; "What is the use of protesting? I have the guns, you haven't." The Johannesburg press became intensely hostile to the President personally, using the term "Krugerism" to encapsulate all the republic's perceived injustices. In August 1895, after gauging burghers' views from across the country, the first volksraad rejected the opposition's bill to give all uitlanders the vote by 14 ballots to 10. Kruger said this did not extend to those who had "proved their trustworthiness", and conferred burgher rights on all uitlanders who had served in Transvaal commandos.

The Delagoa Bay railway line was completed in December 1894—the realisation of a great personal ambition for Kruger, who tightened the final bolt of "our national railway" personally. The formal opening in July 1895 was a gala affair with leading figures from all the neighbouring territories present, including Loch's successor Sir Hercules Robinson. "This railway changed the whole internal situation in the Transvaal", Kruger wrote in his autobiography. "Until that time, the Cape railway had enjoyed a monopoly, so to speak, of the Johannesburg traffic." Difference of opinion between Kruger and Rhodes over the distribution of the profits from customs duties led to the Drifts Crisis of September–October 1895: the Cape Colony avoided the Transvaal railway fees by using wagons instead. Kruger's closure of the drifts ( fords) in the Vaal River where the wagons crossed prompted Rhodes to call for support from Britain on the grounds that the London Convention was being breached. The Colonial Secretary

The following year the National Union sent Kruger a petition bearing 38,500 signatures requesting electoral reform. Kruger dismissed all such entreaties with the assertion that enfranchising "these new-comers, these disobedient persons" might imperil the republic's independence. "Protest!" he shouted at one uitlander deputation; "What is the use of protesting? I have the guns, you haven't." The Johannesburg press became intensely hostile to the President personally, using the term "Krugerism" to encapsulate all the republic's perceived injustices. In August 1895, after gauging burghers' views from across the country, the first volksraad rejected the opposition's bill to give all uitlanders the vote by 14 ballots to 10. Kruger said this did not extend to those who had "proved their trustworthiness", and conferred burgher rights on all uitlanders who had served in Transvaal commandos.

The Delagoa Bay railway line was completed in December 1894—the realisation of a great personal ambition for Kruger, who tightened the final bolt of "our national railway" personally. The formal opening in July 1895 was a gala affair with leading figures from all the neighbouring territories present, including Loch's successor Sir Hercules Robinson. "This railway changed the whole internal situation in the Transvaal", Kruger wrote in his autobiography. "Until that time, the Cape railway had enjoyed a monopoly, so to speak, of the Johannesburg traffic." Difference of opinion between Kruger and Rhodes over the distribution of the profits from customs duties led to the Drifts Crisis of September–October 1895: the Cape Colony avoided the Transvaal railway fees by using wagons instead. Kruger's closure of the drifts ( fords) in the Vaal River where the wagons crossed prompted Rhodes to call for support from Britain on the grounds that the London Convention was being breached. The Colonial Secretary  Understanding that renewed hostilities with Britain were now a real possibility, Kruger began to pursue armament. Relations with Germany had been warming for some time; when Leyds went there for medical treatment in late 1895, he took with him an order from the Transvaal government for rifles and munitions. Conferring with the Colonial Office, Rhodes pondered the co-ordination of an uitlander revolt in Johannesburg with British military intervention, and had a force of about 500 marshalled on the Bechuanaland–Transvaal frontier under

Understanding that renewed hostilities with Britain were now a real possibility, Kruger began to pursue armament. Relations with Germany had been warming for some time; when Leyds went there for medical treatment in late 1895, he took with him an order from the Transvaal government for rifles and munitions. Conferring with the Colonial Office, Rhodes pondered the co-ordination of an uitlander revolt in Johannesburg with British military intervention, and had a force of about 500 marshalled on the Bechuanaland–Transvaal frontier under

In March 1896 Marthinus Theunis Steyn, the young lawyer Kruger had encountered on the ship to England two decades earlier, became President of the Orange Free State. They quickly won each other's confidence; each man's memoirs would describe the other in glowing terms. Chamberlain began to take exception to the South African Republic's diplomatic actions, such as joining the

In March 1896 Marthinus Theunis Steyn, the young lawyer Kruger had encountered on the ship to England two decades earlier, became President of the Orange Free State. They quickly won each other's confidence; each man's memoirs would describe the other in glowing terms. Chamberlain began to take exception to the South African Republic's diplomatic actions, such as joining the  Kruger was never more popular domestically than during the 1897–98

Kruger was never more popular domestically than during the 1897–98

Anglo-German relations warmed during late 1898, with Berlin disavowing any interest in the Transvaal; this opened the way for Milner and Chamberlain to take a firmer line against Kruger. The so-called "Edgar case" of early 1899, in which a South African Republic Policeman was acquitted of

Anglo-German relations warmed during late 1898, with Berlin disavowing any interest in the Transvaal; this opened the way for Milner and Chamberlain to take a firmer line against Kruger. The so-called "Edgar case" of early 1899, in which a South African Republic Policeman was acquitted of  Milner wanted full voting rights after five years' residence, a revised naturalisation oath and increased legislative representation for the new burghers. Kruger offered naturalisation after two years' residence and full franchise after five more (seven years, effectively) along with increased representation and a new oath similar to that of the Free State. The High Commissioner declared his original request an "irreducible minimum" and said he would discuss nothing else until the franchise question was resolved. On 5 June Milner proposed an advisory council of non-burghers to represent the uitlanders, prompting Kruger to cry: "How can strangers rule my state? How is it possible!" When Milner said he did not foresee this council taking on any governing role, Kruger burst into tears, saying "It is our country you want". Milner ended the conference that evening, saying the further meetings Steyn and Kruger wanted were unnecessary.

Back in Pretoria Kruger introduced a draft law to give the mining regions four more seats in each volksraad and fix a seven-year residency period for voting rights. This would not be retroactive, but up to two years' prior residence would be counted towards the seven, and uitlanders already in the country for nine years or more would get the vote immediately. Jan Hendrik Hofmeyr of the Afrikaner Bond persuaded Kruger to make this fully retrospective (to immediately enfranchise all white men in the country seven years or more), but Milner and the South African League deemed this insufficient. After Kruger rejected the British proposal of a joint commission on the franchise law, Smuts and Reitz proposed a five-year retroactive franchise and the extension of a quarter of the volksraad seats to the Witwatersrand region, on the condition that Britain drop any claim to suzerainty. Chamberlain issued an ultimatum in September 1899 in which he insisted on five years without conditions, else the British would "formulate their own proposals for a final settlement".

Kruger resolved that war was inevitable, comparing the Boers' position to that of a man attacked by a lion with only a pocketknife for defence. "Would you be such a coward as not to defend yourself with your pocketknife?" he posited. Aware of the deployment of British troops from elsewhere in the Empire, Kruger and Smuts surmised that from a military standpoint the Boers' only chance was a swift

Milner wanted full voting rights after five years' residence, a revised naturalisation oath and increased legislative representation for the new burghers. Kruger offered naturalisation after two years' residence and full franchise after five more (seven years, effectively) along with increased representation and a new oath similar to that of the Free State. The High Commissioner declared his original request an "irreducible minimum" and said he would discuss nothing else until the franchise question was resolved. On 5 June Milner proposed an advisory council of non-burghers to represent the uitlanders, prompting Kruger to cry: "How can strangers rule my state? How is it possible!" When Milner said he did not foresee this council taking on any governing role, Kruger burst into tears, saying "It is our country you want". Milner ended the conference that evening, saying the further meetings Steyn and Kruger wanted were unnecessary.

Back in Pretoria Kruger introduced a draft law to give the mining regions four more seats in each volksraad and fix a seven-year residency period for voting rights. This would not be retroactive, but up to two years' prior residence would be counted towards the seven, and uitlanders already in the country for nine years or more would get the vote immediately. Jan Hendrik Hofmeyr of the Afrikaner Bond persuaded Kruger to make this fully retrospective (to immediately enfranchise all white men in the country seven years or more), but Milner and the South African League deemed this insufficient. After Kruger rejected the British proposal of a joint commission on the franchise law, Smuts and Reitz proposed a five-year retroactive franchise and the extension of a quarter of the volksraad seats to the Witwatersrand region, on the condition that Britain drop any claim to suzerainty. Chamberlain issued an ultimatum in September 1899 in which he insisted on five years without conditions, else the British would "formulate their own proposals for a final settlement".

Kruger resolved that war was inevitable, comparing the Boers' position to that of a man attacked by a lion with only a pocketknife for defence. "Would you be such a coward as not to defend yourself with your pocketknife?" he posited. Aware of the deployment of British troops from elsewhere in the Empire, Kruger and Smuts surmised that from a military standpoint the Boers' only chance was a swift

The outbreak of war raised Kruger's international profile even further. In countries antagonistic to Britain he was idolised; Kruger expressed high hopes of German, French or Russian military intervention, despite the repeated despatches from Leyds telling him this was a fantasy. Kruger took no part in the fighting, partly because of his age and poor health—he turned 74 the week war broke out—but perhaps primarily to prevent his being killed or captured. His personal contributions to the military campaign were mostly from his office in Pretoria, where he oversaw the war effort and advised his officers by telegram. The Boer commandos, including four of Kruger's sons, six sons-in-law and 33 of his grandsons, advanced quickly into the Cape and Natal, won a series of victories and by the end of October were besieging Siege of Kimberley, Kimberley, Siege of Ladysmith, Ladysmith and Siege of Mafeking, Mafeking. Soon thereafter, following a serious injury to Joubert, Kruger appointed Louis Botha to be acting commandant-general.

The British relief of Kimberley and Ladysmith in February 1900 marked the turning of the war against the Boers. Morale plummeted among the commandos over the following months, with many burghers simply going home; Kruger toured the front in response and asserted that any man who deserted in this time of need should be shot. He had hoped for large numbers of Cape Afrikaners to rally to the republican cause, but only small bands did so, along with a few thousand Boer foreign volunteers, foreign volunteers (principally Dutchmen, Germans and Scandinavians). When British troops entered Bloemfontein on 13 March 1900 Reitz and others urged Kruger to destroy the gold mines, but he refused on the grounds that this would obstruct rehabilitation after the war. Mafeking was relieved two months later and on 30 May Frederick Roberts, 1st Earl Roberts, Lord Roberts took Johannesburg. Kruger left Pretoria on 29 May, travelling by train to Machadodorp, and on 2 June the government abandoned the capital. Roberts entered three days later.

With the major towns and the railways under British control, the conventional phase of the war ended; Kruger wired Steyn pondering surrender, but the Free State President insisted they fight "to the bitter end". Kruger found new strength in Steyn and telegrammed all Transvaal officers forbidding the laying down of arms. ''Bittereinders'' ("bitter-enders") under Botha, Christiaan de Wet and Koos de la Rey took to the veld and waged a guerrilla campaign. British forces under Herbert Kitchener, 1st Earl Kitchener, Lord Kitchener applied a scorched earth policy in response, destroying the farmsteads owned by Boer guerillas still active in the field; non-combatants (mostly women and children) were put into what the British dubbed "Second Boer War concentration camps, concentration camps". Kruger moved to Waterval Onder, where his small house became the "Krugerhof", in late June. After Roberts announced the annexation of the South African Republic to the British Empire on 1 September 1900—the Free State had been annexed on 24 May—Kruger proclaimed on 3 September that this was "not recognised" and "declared null and void". It was decided in the following days that to prevent his capture Kruger would leave for Maputo, Lourenço Marques and there board ship for Europe. Officially he was to tour the continent, and perhaps America too, to raise support for the Boer cause.

The outbreak of war raised Kruger's international profile even further. In countries antagonistic to Britain he was idolised; Kruger expressed high hopes of German, French or Russian military intervention, despite the repeated despatches from Leyds telling him this was a fantasy. Kruger took no part in the fighting, partly because of his age and poor health—he turned 74 the week war broke out—but perhaps primarily to prevent his being killed or captured. His personal contributions to the military campaign were mostly from his office in Pretoria, where he oversaw the war effort and advised his officers by telegram. The Boer commandos, including four of Kruger's sons, six sons-in-law and 33 of his grandsons, advanced quickly into the Cape and Natal, won a series of victories and by the end of October were besieging Siege of Kimberley, Kimberley, Siege of Ladysmith, Ladysmith and Siege of Mafeking, Mafeking. Soon thereafter, following a serious injury to Joubert, Kruger appointed Louis Botha to be acting commandant-general.

The British relief of Kimberley and Ladysmith in February 1900 marked the turning of the war against the Boers. Morale plummeted among the commandos over the following months, with many burghers simply going home; Kruger toured the front in response and asserted that any man who deserted in this time of need should be shot. He had hoped for large numbers of Cape Afrikaners to rally to the republican cause, but only small bands did so, along with a few thousand Boer foreign volunteers, foreign volunteers (principally Dutchmen, Germans and Scandinavians). When British troops entered Bloemfontein on 13 March 1900 Reitz and others urged Kruger to destroy the gold mines, but he refused on the grounds that this would obstruct rehabilitation after the war. Mafeking was relieved two months later and on 30 May Frederick Roberts, 1st Earl Roberts, Lord Roberts took Johannesburg. Kruger left Pretoria on 29 May, travelling by train to Machadodorp, and on 2 June the government abandoned the capital. Roberts entered three days later.

With the major towns and the railways under British control, the conventional phase of the war ended; Kruger wired Steyn pondering surrender, but the Free State President insisted they fight "to the bitter end". Kruger found new strength in Steyn and telegrammed all Transvaal officers forbidding the laying down of arms. ''Bittereinders'' ("bitter-enders") under Botha, Christiaan de Wet and Koos de la Rey took to the veld and waged a guerrilla campaign. British forces under Herbert Kitchener, 1st Earl Kitchener, Lord Kitchener applied a scorched earth policy in response, destroying the farmsteads owned by Boer guerillas still active in the field; non-combatants (mostly women and children) were put into what the British dubbed "Second Boer War concentration camps, concentration camps". Kruger moved to Waterval Onder, where his small house became the "Krugerhof", in late June. After Roberts announced the annexation of the South African Republic to the British Empire on 1 September 1900—the Free State had been annexed on 24 May—Kruger proclaimed on 3 September that this was "not recognised" and "declared null and void". It was decided in the following days that to prevent his capture Kruger would leave for Maputo, Lourenço Marques and there board ship for Europe. Officially he was to tour the continent, and perhaps America too, to raise support for the Boer cause.

Rhodes died in March 1902, bequeathing Groote Schuur to be the official residence for future premiers of a unified South Africa. Kruger quipped to Bredell: "Perhaps I'll be the first." The war formally ended on 31 May 1902 with the signing of the Treaty of Vereeniging; the Boer republics became the Orange River Colony, Orange River and Transvaal Colony, Transvaal Colonies. Kruger accepted it was all over only when Bredell had the flags of the South African Republic and the Orange Free State removed from outside Oranjelust two weeks later. In reply to condolences from Germany, Kruger would only say: "My grief is beyond expression."

Kruger would not countenance the idea of returning home, partly because of personal reluctance to become a British subject again, and partly because he thought he could better serve his people by remaining in exile. Steyn similarly refused to accept the Boer defeat and joined Kruger in Europe, though he did later return to Southern Africa. Botha, De Wet and De la Rey visited Oranjelust in August 1902 and, according to hearsay, were berated by Kruger for "signing away independence"—rumours of such a scene were widespread enough that the generals issued a statement denying them.

After passing from October 1902 to May 1903 at Menton on the French Riviera, Kruger moved back to Hilversum, then returned to Menton in October 1903. In early 1904 he moved to Clarens, Switzerland, Clarens, a small village in the canton of Vaud in western Switzerland where he spent the rest of his days looking over Lake Geneva and the Alps from his balcony. "He who wishes to create a future must not lose track of the past", he wrote in his final letter, addressed to the people of the Transvaal. "Thus; seek all that is to be found good and fair in the past, shape your ideal accordingly and try to realise that ideal for the future. It is true: much that has been built is now destroyed, damaged, and levelled. But with unity of purpose and unity of strength that which has been pulled down can be built again." After contracting pneumonia, Paul Kruger died in Clarens on 14 July 1904 at the age of 78. His Bible lay open on a table beside him.

Kruger's body was initially buried in The Hague but was soon repatriated with British permission. After ceremonial lying in state, he was accorded a state funeral in Pretoria on 16 December 1904, the ''vierkleur'' of the South African Republic draped over his coffin, and buried in what is now called the Heroes' Acre in the Church Street Cemetery.

Rhodes died in March 1902, bequeathing Groote Schuur to be the official residence for future premiers of a unified South Africa. Kruger quipped to Bredell: "Perhaps I'll be the first." The war formally ended on 31 May 1902 with the signing of the Treaty of Vereeniging; the Boer republics became the Orange River Colony, Orange River and Transvaal Colony, Transvaal Colonies. Kruger accepted it was all over only when Bredell had the flags of the South African Republic and the Orange Free State removed from outside Oranjelust two weeks later. In reply to condolences from Germany, Kruger would only say: "My grief is beyond expression."

Kruger would not countenance the idea of returning home, partly because of personal reluctance to become a British subject again, and partly because he thought he could better serve his people by remaining in exile. Steyn similarly refused to accept the Boer defeat and joined Kruger in Europe, though he did later return to Southern Africa. Botha, De Wet and De la Rey visited Oranjelust in August 1902 and, according to hearsay, were berated by Kruger for "signing away independence"—rumours of such a scene were widespread enough that the generals issued a statement denying them.

After passing from October 1902 to May 1903 at Menton on the French Riviera, Kruger moved back to Hilversum, then returned to Menton in October 1903. In early 1904 he moved to Clarens, Switzerland, Clarens, a small village in the canton of Vaud in western Switzerland where he spent the rest of his days looking over Lake Geneva and the Alps from his balcony. "He who wishes to create a future must not lose track of the past", he wrote in his final letter, addressed to the people of the Transvaal. "Thus; seek all that is to be found good and fair in the past, shape your ideal accordingly and try to realise that ideal for the future. It is true: much that has been built is now destroyed, damaged, and levelled. But with unity of purpose and unity of strength that which has been pulled down can be built again." After contracting pneumonia, Paul Kruger died in Clarens on 14 July 1904 at the age of 78. His Bible lay open on a table beside him.

Kruger's body was initially buried in The Hague but was soon repatriated with British permission. After ceremonial lying in state, he was accorded a state funeral in Pretoria on 16 December 1904, the ''vierkleur'' of the South African Republic draped over his coffin, and buried in what is now called the Heroes' Acre in the Church Street Cemetery.

''The Memoirs of Paul Kruger: Four Times President of The South African Republic''

New York: Century, 1902 * {{DEFAULTSORT:Kruger, Paul Paul Kruger, 1825 births 1904 deaths People from Walter Sisulu Local Municipality Cape Colony politicians Afrikaner nationalists South African people of German descent Members of the Reformed Churches in South Africa Presidents of the South African Republic Vice presidents of the South African Republic Members of the Volksraad of the South African Republic South African Republic generals People of the First Boer War People of the Second Boer War South African amputees South African exiles South African memoirists South African people of Dutch descent South African people of French descent South African white supremacists Flat Earth proponents 1880s in the South African Republic 1890s in the South African Republic Deaths from pneumonia in Switzerland 19th-century memoirists

South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. Its Provinces of South Africa, nine provinces are bounded to the south by of coastline that stretches along the Atlantic O ...

, and State President of the South African Republic

The state president of the South African Republic had the executive authority in the South African Republic. According to the constitution of 1871, executive power was vested in the president, who was responsible to the Volksraad. The presiden ...

(or Transvaal) from 1883 to 1900. Nicknamed , he came to international prominence as the face of the Boer

Boers ( ; ; ) are the descendants of the proto Afrikaans-speaking Free Burghers of the eastern Cape frontier in Southern Africa during the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. From 1652 to 1795, the Dutch East India Company controlled the Dutch ...

cause—that of the Transvaal and its neighbour the Orange Free State

The Orange Free State ( ; ) was an independent Boer-ruled sovereign republic under British suzerainty in Southern Africa during the second half of the 19th century, which ceased to exist after it was defeated and surrendered to the British Em ...

—against Britain during the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War (, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, Transvaal War, Anglo–Boer War, or South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer republics (the South African Republic and ...

of 1899–1902. He has been called a personification of Afrikaner

Afrikaners () are a Southern African ethnic group descended from predominantly Dutch settlers who first arrived at the Cape of Good Hope in 1652.Entry: Cape Colony. ''Encyclopædia Britannica Volume 4 Part 2: Brain to Casting''. Encyclopæd ...

dom and admirers venerate him as a tragic folk hero.

Born near the eastern edge of the Cape Colony

The Cape Colony (), also known as the Cape of Good Hope, was a British Empire, British colony in present-day South Africa named after the Cape of Good Hope. It existed from 1795 to 1802, and again from 1806 to 1910, when it united with three ...

, Kruger took part in the Great Trek

The Great Trek (, ) was a northward migration of Dutch-speaking settlers who travelled by wagon trains from the Cape Colony into the interior of modern South Africa from 1836 onwards, seeking to live beyond the Cape's British colonial adminis ...

as a child during the late 1830s. He had almost no education apart from the Bible. A protégé of the Voortrekker leader Andries Pretorius

Andries Wilhelmus Jacobus Pretorius (27 November 179823 July 1853) was a leader of the Boers who was instrumental in the creation of the South African Republic, as well as the earlier but short-lived Natalia Republic, in present-day South Africa ...

, he witnessed the signing of the Sand River Convention

The Sand River Convention () of 17 January 1852 was a Treaty, convention whereby the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland formally recognised the independence of the Boers north of the Vaal River.

Background

The convention was signed o ...

with Britain in 1852 and over the next decade played a prominent role in the forging of the South African Republic, leading its commandos

A commando is a combatant, or operative of an elite light infantry or special operations force, specially trained for carrying out raids and operating in small teams behind enemy lines.

Originally, "a commando" was a type of combat unit, as opp ...

and resolving disputes between the rival Boer leaders and factions. In 1863 he was elected Commandant-General

Commandant-general is a military rank in several countries and is generally equivalent to that of major-general.

Argentina

Commandant general is the highest rank in the Argentine National Gendarmerie, and is held by the national director of the ...

, a post he held for a decade before he resigned soon after the election of President Thomas François Burgers

Thomas François Burgers (15 April 1834 – 9 December 1881) was a South African politician and minister who served as the 4th president of the South African Republic from 1872 to 1877. He was the youngest child of Barend and Elizabeth Burger of ...

.

Kruger was appointed vice president

A vice president or vice-president, also director in British English, is an officer in government or business who is below the president (chief executive officer) in rank. It can also refer to executive vice presidents, signifying that the vi ...

in March 1877, shortly before the South African Republic was annexed by Britain as the Transvaal. Over the next three years he headed two deputations to London to try to have this overturned. He became the leading figure in the movement to restore the South African Republic's independence, culminating in the Boers' victory in the First Boer War

The First Boer War (, ), was fought from 16 December 1880 until 23 March 1881 between the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom and Boers of the Transvaal (as the South African Republic was known while under British ad ...

of 1880–1881. Kruger served until 1883 as a member of an executive triumvirate

A triumvirate () or a triarchy is a political institution ruled or dominated by three individuals, known as triumvirs (). The arrangement can be formal or informal. Though the three leaders in a triumvirate are notionally equal, the actual distr ...

, then was elected president. In 1884 he headed a third deputation that brokered the London Convention, under which Britain recognised the South African Republic as a completely independent state.

Following the influx of thousands of predominantly British settlers with the Witwatersrand Gold Rush

The Witwatersrand Gold Rush was a gold rush that began in 1886 and led to the establishment of Johannesburg, South Africa. It was a part of the Mineral Revolution.

Origins

In the modern-day province of Mpumalanga, gold miners in the alluvial ...

of 1886, "s" (foreigners) provided almost all of the South African Republic's tax revenues but lacked civic representation; Boer burghers retained control of the government. The problem and the associated tensions with Britain dominated Kruger's attention for the rest of his presidency, to which he was re-elected in 1888

Events January

* January 3 – The great telescope (with an objective lens of diameter) at Lick Observatory in California is first used.

* January 12 – The Schoolhouse Blizzard hits Dakota Territory and the states of Montana, M ...

, 1893

Events

January

* January 2 – Webb C. Ball introduces railroad chronometers, which become the general railroad timepiece standards in North America.

* January 6 – The Washington National Cathedral is chartered by Congress; th ...

and 1898

Events

January

* January 1 – New York City annexes land from surrounding counties, creating the City of Greater New York as the world's second largest. The city is geographically divided into five boroughs: Manhattan, Brooklyn, Queen ...

, and led to the Jameson Raid

The Jameson Raid (Afrikaans: ''Jameson-inval'', , 29 December 1895 – 2 January 1896) was a botched raid against the South African Republic (commonly known as the Transvaal) carried out by British colonial administrator Leander Starr Jameson ...

of 1895–1896 and ultimately the Second Boer War. Kruger left for Europe as the war turned against the Boers in 1900 and spent the rest of his life in exile, refusing to return home following the British victory. After he died in Switzerland at the age of 78 in 1904, his body was returned to South Africa for a state funeral, and buried in the Heroes' Acre in Pretoria

Pretoria ( ; ) is the Capital of South Africa, administrative capital of South Africa, serving as the seat of the Executive (government), executive branch of government, and as the host to all foreign embassies to the country.

Pretoria strad ...

.

Early life

Family and childhood

Stephanus Johannes Paulus Kruger was born on 10 October 1825 at Bulhoek, a farm in theSteynsburg

Steynsburg is a small town in the Walter Sisulu Local Municipality of the Joe Gqabi District Municipality, Eastern Cape province of South Africa. Steynsburg is located on the intersection of the R56 and R390.

The town lies south-west of Bur ...

area of the Cape Colony

The Cape Colony (), also known as the Cape of Good Hope, was a British Empire, British colony in present-day South Africa named after the Cape of Good Hope. It existed from 1795 to 1802, and again from 1806 to 1910, when it united with three ...

, the third child and second son of Casper Jan Hendrik Kruger (1801–1852), a farmer, and his wife Elsje (Elisa; ''née'' Steyn; 1806–1834). The family was of Dutch-speaking Afrikaner

Afrikaners () are a Southern African ethnic group descended from predominantly Dutch settlers who first arrived at the Cape of Good Hope in 1652.Entry: Cape Colony. ''Encyclopædia Britannica Volume 4 Part 2: Brain to Casting''. Encyclopæd ...

background, and of German, French Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , ; ) are a Religious denomination, religious group of French people, French Protestants who held to the Reformed (Calvinist) tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, ...

and Dutch stock. Kruger also had some Khoi

Khoikhoi ( /ˈkɔɪkɔɪ/ ''KOY-koy'') (or Khoekhoe in Namibian orthography) are the traditionally nomadic pastoralist indigenous population of South Africa. They are often grouped with the hunter-gatherer San (literally "foragers") peop ...

ancestry, which came down to him from his ancestress Krotoa

The "!Oroǀõas" ("Ward (law), Ward-girl"), spelled in Dutch language, Dutch as Krotoa or Kroket, otherwise known by her Christian name Eva (c. 1643 – 29 July 1674), was a Strandloper peoples, !Uriǁ'aeǀona translator who worked for the Dutch ...

. The Kruger family’s paternal ancestors had lived in South Africa since 1713, when Jacob Krüger, from Berlin

Berlin ( ; ) is the Capital of Germany, capital and largest city of Germany, by both area and List of cities in Germany by population, population. With 3.7 million inhabitants, it has the List of cities in the European Union by population withi ...

, arrived in Cape Town

Cape Town is the legislature, legislative capital city, capital of South Africa. It is the country's oldest city and the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. Cape Town is the country's List of municipalities in South Africa, second-largest ...

as a 17-year-old soldier in the Dutch East India Company

The United East India Company ( ; VOC ), commonly known as the Dutch East India Company, was a chartered company, chartered trading company and one of the first joint-stock companies in the world. Established on 20 March 1602 by the States Ge ...

's service. Jacob's children dropped the umlaut from the family name, a common practice among South Africans of German origin. Over the following generations, Kruger's paternal forebears moved into the interior. His mother's family, the Steyns, had lived in South Africa since 1668 and were relatively affluent and cultured by Cape standards. Kruger's great-grand-uncle Hermanus Steyn had been president of the self-declared Republic of Swellendam that revolted against Company rule in 1795.

Bulhoek, Kruger's birthplace, was the Steyn family farm and had been Elsie's home since early childhood; her father Douw Gerbrand Steyn had settled there in 1809. The Kruger and Steyn families were acquainted and Casper occasionally visited Bulhoek as a young man. He and Elsie married in Cradock in 1820, when he was 19 and she was 14. A girl, Sophia, and a boy, Douw Gerbrand, were born before Paul was born in 1825. His first two names, Stephanus Johannes, were chosen after his paternal grandfather, but rarely used. The provenance of the third given name, Paulus, "was to remain rather a mystery", Johannes Meintjes wrote in his 1974 biography of Kruger, "and yet the boy was always called Paul."

Paul Kruger was baptised at Cradock on 19 March 1826. Soon thereafter his parents acquired a farm of their own to the north-west at Vaalbank, near Colesberg

Colesberg is a town with 17,354 inhabitants in the Northern Cape province of South Africa, located on the main N1 road from Cape Town to Johannesburg.

In a sheep-farming area spread over half-a-million hectares, greater Colesberg breeds ma ...

, in the remote north-east of the Cape Colony. His mother died when he was eight; his father Casper soon remarried and had more children with his second wife, Heiletje (''née'' du Plessis). Beyond reading and writing, which he learned from relatives, the only education Kruger received was three months of study under a travelling tutor, Tielman Roos, and Calvinist

Reformed Christianity, also called Calvinism, is a major branch of Protestantism that began during the 16th-century Protestant Reformation. In the modern day, it is largely represented by the Continental Reformed Protestantism, Continenta ...

religious instruction from his father. In adulthood, Kruger would claim to have never read any book apart from the Bible.

Great Trek

In 1834 Casper Kruger, his father, and his brothers Gert and Theuns moved their families east and set up farms near the

In 1834 Casper Kruger, his father, and his brothers Gert and Theuns moved their families east and set up farms near the Caledon River

The Caledon River () is a major river located in central South Africa. Its total length is , rising in the Drakensberg Mountains on the Lesotho border, flowing southwestward and then westward before joining the Orange River near Bethulie in the ...

, on the Cape Colony's far north-eastern frontier. The Cape had been under British sovereignty since 1814 when the Netherlands ceded it to Britain with the Convention of London. Boer discontent with aspects of British rule, such as the institution of English as the sole official language and the abolition of slavery in 1834, led to the Great Trek

The Great Trek (, ) was a northward migration of Dutch-speaking settlers who travelled by wagon trains from the Cape Colony into the interior of modern South Africa from 1836 onwards, seeking to live beyond the Cape's British colonial adminis ...

—a mass migration by Dutch-speaking " Voortrekkers" north-east from the Cape to the land on the far side of the Orange

Orange most often refers to:

*Orange (fruit), the fruit of the tree species '' Citrus'' × ''sinensis''

** Orange blossom, its fragrant flower

** Orange juice

*Orange (colour), the color of an orange fruit, occurs between red and yellow in the vi ...

and Vaal

The Vaal River ( ; Khoemana: ) is the largest tributary of the Orange River in South Africa. The river has its source near Breyten in Mpumalanga province, east of Johannesburg and about north of Ermelo and only about from the Indian Oce ...

rivers. Many Boers had been expressing displeasure with the British Cape administration for some time, but the Krugers were comparatively content. They had always co-operated with the British, and had not owned slaves. They had given little thought to the idea of leaving the Cape.

A group of emigrants under Hendrik Potgieter

Andries Hendrik Potgieter, known as Hendrik Potgieter (19 December 1792 – 16 December 1852) was a Voortrekker leader. He served as the first head of state of Potchefstroom from 1840 and 1845 and also as the first head of state of Zoutpansberg ...

passed through the Krugers' Caledon encampments in early 1836. Potgieter envisioned a Boer republic with himself in a prominent role; he sufficiently impressed the Krugers that they joined his party of Voortrekkers. Kruger's father continued to give the children religious education in the Boer fashion during the trek, having them recite or write down biblical passages from memory each day after lunch and dinner. At stops along the journey, the trekkers made improvised classrooms, marking them with reeds and grass. The more educated emigrants took turns in teaching.

The Voortrekkers faced indigenous competition for the area they were entering from Mzilikazi

Mzilikazi Moselekatse, Khumalo ( 1790 – 9 September 1868) was a Southern African king who founded the Ndebele Kingdom now called Matebeleland which is now part of Zimbabwe. His name means "the great river of blood". He was born the son of M ...

and his Ndebele

Ndebele may refer to:

*Southern Ndebele people, located in South Africa

*Northern Ndebele people, located in Zimbabwe

* Sumayela Ndebele (Northern Transvaal Ndebele), located in South Africa

Languages

*Southern Ndebele language, the language of ...

(or Matabele) people, a branch from the Zulu Kingdom

The Zulu Kingdom ( ; ), sometimes referred to as the Zulu Empire, was a monarchy in Southern Africa. During the 1810s, Shaka established a standing army that consolidated rival clans and built a large following which ruled a wide expanse of So ...

to the south-east. On 16 October 1836, the 11-year-old Kruger took part in the Battle of Vegkop, where Potgieter's laager

A wagon fort, wagon fortress, wagenburg or corral, often referred to as circling the wagons, is a temporary fortification made of wagons arranged into a rectangle, circle, or other shape and possibly joined with each other to produce an improvis ...

, a circle of wagons chained together, was unsuccessfully attacked by Mzilikazi and around 4,000–6,000 Matabele warriors. Kruger and the other small children assisted in tasks such as bullet-casting, while the women and larger boys helped the fighting men, of whom there were about 40. Kruger could recall the battle in great detail and give a vivid account well into old age.

During 1837 and 1838 Kruger's family was part of the Voortrekker group under Potgieter that trekked further east into Natal. Here they met the American missionary Daniel Lindley, who gave young Paul much spiritual invigoration. The Zulu King Dingane

Dingane ka Senzangakhona Zulu (–29 January 1840), commonly referred to as Dingane, Dingarn or Dingaan, was a Zulu prince who became king of the Zulu Kingdom in 1828, after assassinating his half-brother Shaka Zulu. He set up his royal capita ...

concluded a land treaty with Potgieter. But he reconsidered and massacred first Piet Retief

Pieter Mauritz Retief (12 November 1780 – 6 February 1838) was a '' Voortrekker'' leader. Settling in 1814 in the frontier region of the Cape Colony, he later assumed command of punitive expeditions during the sixth Xhosa War. He became a s ...

's party of settlers, then others at Weenen. Kruger later recounted his family's group coming under attack from Zulus soon after the Retief massacre, describing "children pinioned to their mothers' breasts by spears, or with their brains dashed out on waggon wheels". But "God heard our prayer", he recalled, and "we followed them and shot them down as they fled, until more of them were dead than those of us they had killed in their attack ... I could shoot moderately well for we lived, so to speak, among the game."

Because of the attacks, the Krugers returned to the highveld, where they took part in Potgieter's campaign that forced Mzilikazi to move his people north, across the Limpopo River

The Limpopo River () rises in South Africa and flows generally eastward through Mozambique to the Indian Ocean. The term Limpopo is derived from Rivombo (Livombo/Lebombo), a group of Tsonga settlers led by Hosi Rivombo who settled in the mou ...

, to what became Matabeleland

Matabeleland is a region located in southwestern Zimbabwe that is divided into three provinces: Matabeleland North, Bulawayo, and Matabeleland South. These provinces are in the west and south-west of Zimbabwe, between the Limpopo and Zambezi ...

. Kruger and his father settled at the foot of the Magaliesberg

The Magaliesberg (historically also known as ''Macalisberg'' or ''Cashan Mountains'') of northern South Africa, is a modest but well-defined mountain range composed mainly of quartzites. It rises at a point south of the Pilanesberg (and the ...

mountains in the Transvaal. In Natal Andries Pretorius

Andries Wilhelmus Jacobus Pretorius (27 November 179823 July 1853) was a leader of the Boers who was instrumental in the creation of the South African Republic, as well as the earlier but short-lived Natalia Republic, in present-day South Africa ...

defeated more than 10,000 of Dingane's Zulus at the Battle of Blood River

The Battle of Blood River or Voortrekker-Zulu War (16 December 1838) was fought on the bank of the Blood River, Ncome River, in what is today KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa between 464 Voortrekkers ("Pioneers"), led by Andries Pretorius, and an es ...

on 16 December 1838, a date subsequently marked by the Boers as the Day of the Vow

The Day of the Vow () is a religious public holiday in South Africa. It is an important day for Afrikaners, originating from the Battle of Blood River on 16 December 1838, before which 464 Voortrekkers made a promise to God that if he rescued th ...

.Burgher

Boer tradition of the time dictated that men were entitled to choose two farms—one for crops and one for grazing—upon becoming enfranchised burghers at the age of 16. Kruger set up his home at the farm Boekenhoutfontein, near Rustenburg in the Magaliesberg area. Kruger later became the owner of a piece of farmland named Waterkloof, on 30 September 1842. This concluded, he wasted little time in pursuing the hand of Maria du Plessis, the daughter of a fellow Voortrekker south of the Vaal; she was only 14 years old when they married inPotchefstroom

Potchefstroom ( ; ), colloquially known as Potch, is an college town, academic city in the North West (South African province), North West Province of South Africa. It hosts the Potchefstroom Campus of the North-West University. Potchefstro ...

in 1842. The same year Kruger was elected a deputy field cornet

Field cornet () is a term formerly used in South Africa for either a local government official or a military officer.

The office had its origins in the position of ''veldwachtmeester'' in the Dutch Cape colony, and was regarded as being equivalent ...

—"a singular honour at seventeen", Meintjes comments. This role combined the civilian duties of a local magistrate with a military rank equivalent to that of a junior commissioned officer

An officer is a person who holds a position of authority as a member of an armed force or uniformed service.

Broadly speaking, "officer" means a commissioned officer, a non-commissioned officer (NCO), or a warrant officer. However, absent ...

.

Kruger was already an accomplished frontiersman, horseman, and guerrilla

Guerrilla warfare is a form of unconventional warfare in which small groups of irregular military, such as rebels, Partisan (military), partisans, paramilitary personnel or armed civilians, which may include Children in the military, recruite ...

fighter. In addition to his native Dutch, he could speak basic English and several African languages, some fluently. He had shot a lion for the first time when he was a boy—in old age he recalled being 14, but Meintjes suggests he may have been as young as 11. During his many hunting excursions, Kruger was nearly killed on several occasions. In 1845, while he was hunting rhinoceros along the Steelpoort River, his four-bore elephant gun

An elephant gun is a large caliber gun, rifled or smoothbore, originally developed for use by big-game hunters for elephant and other large game. Elephant guns were black powder muzzle-loaders at first, then black powder express rifles, t ...

exploded in his hands and blew off most of his left thumb. Kruger wrapped the wound in a handkerchief and retreated to camp, where he treated it with turpentine

Turpentine (which is also called spirit of turpentine, oil of turpentine, terebenthine, terebenthene, terebinthine and, colloquially, turps) is a fluid obtainable by the distillation of resin harvested from living trees, mainly pines. Principall ...

. He refused calls to have the hand amputated by a doctor, and instead cut off the remains of the injured thumb himself with a pocketknife. When gangrenous marks appeared on his arm up to his shoulder, he placed the hand in the stomach of a freshly killed goat, a traditional Boer remedy. He considered this a success—"when it came to the turn of the second goat, my hand was already easier and the danger much less." The wound took more than six months to heal, but he did not wait that long to start hunting again.

Britain annexed the Voortrekkers' short-lived

Britain annexed the Voortrekkers' short-lived Natalia Republic

The Natalia Republic was a short-lived Boer republic founded in 1839 after a Voortrekker victory against the Zulus at the Battle of Blood River. The area was previously named ''Natália'' by Portuguese sailors, due to its discovery on Christm ...

in 1843 as the Colony of Natal

The Colony of Natal was a British colony in south-eastern Africa. It was proclaimed a British colony on 4 May 1843 after the British government had annexed the Boer Republic of Natalia, and on 31 May 1910 combined with three other colonies t ...

. Pretorius briefly led Boer resistance to this, but before long most of the Boers in Natal had trekked back north-west to the area around the Orange and Vaal rivers. In 1845 Kruger was a member of Potgieter's expedition to Delagoa Bay

Delagoa is a marine ecoregion along the eastern coast of Africa. It extends along the coast of Mozambique and South Africa from the Bazaruto Archipelago (21°14’ S) to Lake St. Lucia in South Africa (28° 10' S) in South Africa's Kwazulu-Nat ...

in Mozambique

Mozambique, officially the Republic of Mozambique, is a country located in Southeast Africa bordered by the Indian Ocean to the east, Tanzania to the north, Malawi and Zambia to the northwest, Zimbabwe to the west, and Eswatini and South Afr ...

to negotiate a frontier with Portugal; the Lebombo Mountains

The Lebombo Mountains, also called Lubombo Mountains, Rivombo Mountains (), are an , narrow range of mountains in Southern Africa. They stretch from Hluhluwe in KwaZulu-Natal in the south to Punda Maria in the Limpopo Province in South Africa ...

was settled upon as the border between Boer and Portuguese lands. Maria and their first child died of fever in January 1846. In 1847 Kruger married her cousin, Gezina du Plessis, from the Colesberg area. Their first child, Casper Jan Hendrik, was born on 22 December that year.

Concerned by the exodus of so many whites from the Cape and Natal, and taking the view that the Boers remained British subject

The term "British subject" has several different meanings depending on the time period. Before 1949, it referred to almost all subjects of the British Empire (including the United Kingdom, Dominions, and colonies, but excluding protectorates ...

s, the British Governor Sir Harry Smith

Lieutenant-General Sir Henry George Wakelyn Smith, 1st Baronet, GCB (28 June 1787 – 12 October 1860) was a notable English soldier and military commander in the British Army of the early 19th century. A veteran of the Napoleonic Wars, he is a ...

in 1848 annexed the area between the Orange and Vaal rivers as the "Orange River Sovereignty

The Orange River Sovereignty (1848–1854; ) was a short-lived political entity between the Orange River, Orange and Vaal rivers in Southern Africa, a region known informally as Transorangia. In 1854, it became the Orange Free State, and is now ...

". Pretorius led a Boer commando raid against this, and they were defeated by Smith at the Battle of Boomplaats

The Battle of Boomplaats (also referred to as the Battle of Boomplaas) was fought near Jagersfontein at on 29 August 1848 between the British and the Voortrekkers. The British were led by Sir Harry Smith, while the Boers were led by Andries Pre ...

. Like the Krugers, Pretorius lived in the Magaliesberg mountains and often hosted the young Kruger, who greatly admired the elder man's resolve, sophistication, and piety. A warm relationship developed. "Kruger's political awareness can be dated from 1850", Meintjes writes, "and it was in no small measure given to him by Pretorius." Like Pretorius, Kruger wanted to centralise the emigrants under a single authority and win British recognition for their territory as an independent state. This last point was not due to hostility to Britain—neither Pretorius nor Kruger was particularly anti-British—but because they perceived the emigrants' unity as under threat if the Cape administration continued to regard them as British subjects.

Henry Douglas Warden, the British Resident

Resident may refer to:

People and functions

* Resident minister, a representative of a government in a foreign country

* Resident (medicine), a stage of postgraduate medical training

* Resident (pharmacy), a stage of postgraduate pharmaceut ...

in the Orange River area, advised Smith in 1851 that he thought a compromise should be attempted with Pretorius. Smith sent representatives to meet him at the Sand River. Kruger, aged 26, accompanied Pretorius and on 17 January 1852 was present at the conclusion of the Sand River Convention

The Sand River Convention () of 17 January 1852 was a Treaty, convention whereby the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland formally recognised the independence of the Boers north of the Vaal River.

Background

The convention was signed o ...

, under which Britain recognised "the Emigrant Farmers" in the Transvaal as independent: they called themselves the ''Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek

The South African Republic (, abbreviated ZAR; ), also known as the Transvaal Republic, was an independent Boer republic in Southern Africa which existed from 1852 to 1902, when it was annexed into the British Empire as a result of the Second ...

'' ("South African Republic"). In exchange for the Boers' pledge not to introduce slavery in the Transvaal, the British agreed not to make an alliance with any "coloured nations" there. Kruger's uncle Gert was also present; his father Casper would have been as well but he was ill and unable to attend.

Field cornet

The Boer colonists and the local

The Boer colonists and the local Tswana

Tswana may refer to:

* Tswana people, the Bantu languages, Bantu speaking people in Botswana, South Africa, Namibia, Zimbabwe, Zambia, and other Southern Africa regions

* Tswana language, the language spoken by the (Ba)Tswana people

* Tswanaland, ...

and Basotho

The Sotho (), also known as the Basotho (), are a Sotho-Tswana ethnic group indigenous to Southern Africa. They primarily inhabit the regions of Lesotho, South Africa, Botswana and Namibia.

The ancestors of the Sotho people are believed to h ...

chiefdoms were in near-constant conflict, mainly over land. Kruger was elected field cornet of his district in 1852,; . and in August that year he took part in the Battle of Dimawe, a raid against the Tswana chief Sechele I

Sechele I a Motswasele "Rra Mokonopi" (1812–1892), also known as Setshele, was the ruler of the Kwêna people of Botswana. He was converted to Christianity by David Livingstone and in his role as ruler served as a missionary among his own ...

. The Boer commando was headed by Pretorius, but in practice he did not take much part as he was suffering from dropsy

Edema (American English), also spelled oedema (British English), and also known as fluid retention, swelling, dropsy and hydropsy, is the build-up of fluid in the body's tissue. Most commonly, the legs or arms are affected. Symptoms may inclu ...

(edema). Kruger narrowly escaped death twice—first a piece of shrapnel hit him in the head but knocked him out without cutting him; later a Tswana bullet swiped across his chest, tearing his jacket but not wounding him. The commando wrecked David Livingstone

David Livingstone (; 19 March 1813 – 1 May 1873) was a Scottish physician, Congregationalist, pioneer Christian missionary with the London Missionary Society, and an explorer in Africa. Livingstone was married to Mary Moffat Livings ...

's mission station at Kolobeng, destroying his medicines and books. Livingstone was away at the time. Kruger's version of the story was that the Boers found an armoury and a workshop for repairing firearms in Livingstone's house and, interpreting this as a breach of Britain's promise at the Sand River not to arm tribal chiefs, confiscated them. Whatever the truth, Livingstone wrote about the Boers in strongly condemnatory terms thereafter, depicting them as mindless barbarians.

Livingstone and many others criticised the Boers for abducting women and children from tribal settlements and taking them home to work as slaves. The Boers argued that they did not keep these captives as slaves but as '' inboekelings''—indentured

An indenture is a legal contract that reflects an agreement between two parties. Although the term is most familiarly used to refer to a labor contract between an employer and a laborer with an indentured servant status, historically indentures we ...

"apprentices" who, having lost their families, were given bed, board and training in a Boer household until reaching adulthood. Modern scholarship widely dismisses this as a technical ruse by the Boers to enforce a means of inexpensive labour for them while avoiding overt slavery. Gezina Kruger had an ''inboekeling'' maid for whom she eventually arranged marriage, and paid her a dowry

A dowry is a payment such as land, property, money, livestock, or a commercial asset that is paid by the bride's (woman's) family to the groom (man) or his family at the time of marriage.

Dowry contrasts with the related concepts of bride price ...

.

Having been promoted to the rank of lieutenant (between field cornet and commandant

Commandant ( or ; ) is a title often given to the officer in charge of a military (or other uniformed service) training establishment or academy. This usage is common in English-speaking nations. In some countries it may be a military or police ...

), Kruger formed part of a commando sent against the chief Montshiwa in December 1852 to recover some stolen cattle. Pretorius was still sick, and only nominally in command. Seven months later, on 23 July 1853, Pretorius died, aged 54. Just before the end he sent for Kruger, but the young man arrived too late. Meintjes says that Pretorius "was perhaps the first person to recognise that behind ruger'srough exterior was a most singular person with an intellect all the more remarkable for being almost entirely self-developed".

Commandant

Pretorius did not name a successor asCommandant-General

Commandant-general is a military rank in several countries and is generally equivalent to that of major-general.

Argentina

Commandant general is the highest rank in the Argentine National Gendarmerie, and is held by the national director of the ...

; his eldest son, Marthinus Wessel Pretorius

Marthinus Wessel Pretorius (17 September 1819 – 19 May 1901) was a South African political leader. An Afrikaners, Afrikaner (or "Boer"), he helped establish the South African Republic (''Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek'' or ZAR; also referred to ...

, was appointed in his stead. The younger Pretorius elevated Kruger to the rank of commandant. Pretorius, the son, claimed power over not just the Transvaal but also the Orange River area—he said the British had promised it to his father—but virtually nobody, not even supporters like Kruger, accepted this. Following Sir George Cathcart

Major-General Sir George Cathcart (12 May 1794 – 5 November 1854) was a Scottish general and diplomat. He was killed in action at the Battle of Inkerman during the Crimean War.

Military career

Cathcart was born in Renfrewshire, a younger ...

's replacement of Smith as governor in Cape Town, the British policy towards the Orange River Sovereignty changed to the extent that the British were willing to pull out and grant independence to a second Boer republic there. This was in spite of the fact that in addition to the Boer settlers, there were many English-speaking colonists who wanted rule from the Cape to continue. On 23 February 1854 Sir George Russell Clerk signed the Orange River Convention

The Orange River Convention (sometimes also called the Bloemfontein Convention; ) was a Treaty, convention whereby the British Empire, British formally recognised the independence of the Boers in the area between the Orange River, Orange and Vaal ...

, ending the sovereignty and recognising what the Boers dubbed the '' Oranje-Vrijstaat'' ("Orange Free State").

Bloemfontein

Bloemfontein ( ; ), also known as Bloem, is the capital and the largest city of the Free State (province), Free State province in South Africa. It is often, and has been traditionally, referred to as the country's "judicial capital", alongsi ...

, the former British garrison town, became the Free State's capital; the Transvaal seat of government became Pretoria

Pretoria ( ; ) is the Capital of South Africa, administrative capital of South Africa, serving as the seat of the Executive (government), executive branch of government, and as the host to all foreign embassies to the country.

Pretoria strad ...

, named after the elder Pretorius. The South African Republic was in practice split between the south-west and central Transvaal, where most of Pretorius' supporters were, and regionalist factions in the Zoutpansberg

Zoutpansberg was the north-eastern division of the Transvaal, South Africa, encompassing an area of 25,654 square miles. The chief towns at the time were Pietersburg and Leydsdorp. It was divided into two districts (west and east) prior to the ...

, Lydenburg

Lydenburg, also known as Mashishing, is a town in Thaba Chweu Local Municipality, on the Mpumalanga highveld, South Africa. It is situated on the Sterkspruit/Dorps River tributary of the Lepelle River at the summit of the Long Tom Pass. It h ...

and Utrecht

Utrecht ( ; ; ) is the List of cities in the Netherlands by province, fourth-largest city of the Netherlands, as well as the capital and the most populous city of the Provinces of the Netherlands, province of Utrecht (province), Utrecht. The ...

districts that viewed any central authority with suspicion. Kruger's first campaign as a commandant was in the latter part of 1854, against the chiefs Mapela and Makapan near the Waterberg. The chiefs retreated into what became called the Caves of Makapan ("Makapansgat") with many of their people and cattle, and a siege ensued in which thousands of the defenders died, mainly from starvation. When Commandant-General Piet Potgieter of Zoutpansberg was shot dead, Kruger advanced under heavy fire to retrieve the body and was almost killed himself.

Mediator

Marthinus Pretorius hoped to achieve either federation or amalgamation with the Orange Free State, but before he could contemplate this he would have to unite the Transvaal. In 1855 he appointed an eight-man constitutional commission, including Kruger, which presented a draft constitution in September that year. Lydenburg and Zoutpansberg rejected the proposals, calling for a less centralised government. Pretorius tried again during 1856, holding meetings with eight-man commissions in Rustenburg, Potchefstroom and Pretoria, but

Marthinus Pretorius hoped to achieve either federation or amalgamation with the Orange Free State, but before he could contemplate this he would have to unite the Transvaal. In 1855 he appointed an eight-man constitutional commission, including Kruger, which presented a draft constitution in September that year. Lydenburg and Zoutpansberg rejected the proposals, calling for a less centralised government. Pretorius tried again during 1856, holding meetings with eight-man commissions in Rustenburg, Potchefstroom and Pretoria, but Stephanus Schoeman

Stephanus Schoeman (14 March 1810 – 19 June 1890) was President of the South African Republic from 6 December 1860 until 17 April 1862. His red hair, fiery temperament and vehement disputes with other Boer leaders earned him th ...

, Zoutpansberg's new Commandant-General, repudiated these efforts.

The constitution settled upon formalised a national Volksraad The Volksraad was a people's assembly or legislature in Dutch or Afrikaans speaking government.

Assembly South Africa

* Volksraad (South African Republic) (1840–1902)

* Volksraad (Natalia Republic), a similar assembly that existed in the Natalia ...

(parliament) and created an executive council, headed by a president. Pretorius was sworn in as the first president of the South African Republic on 6 January 1857. Kruger successfully proposed Schoeman for the post of national Commandant-General, hoping to thereby end the factional disputes and foster unity, but Schoeman categorically refused to serve under this constitution or Pretorius. With the Transvaal on the verge of civil war, tensions also rose with the Orange Free State after Pretorius's ambitions of absorbing it became widely known. Kruger had strong personal reservations about Pretorius, not considering him his father's equal, but nevertheless remained steadfastly loyal to him.