Basics

Verb conjugation in Proto-Indo-European involves the interplay of six dimensions (number, person, voice, mood, aspect and tense) with the following variables identified under the ''Cowgill-Rix'' system, which is one of the methodologies proposed and applies only to certain subfamilies: Further, participles can be considered part of the verbal systems although they are not verbs themselves, and as with other PIE nouns, they can be declined across seven or eight cases, for threeBuilding blocks

Roots

The starting point for the morphological analysis of the PIE verb is theStems and stem formation

Before the final endings — to denote number, person, etc., can be applied, additional elements () may be added to the root (). The resulting component here after any such affixion is the stem, to which the final endings () can then be added to obtain the conjugated forms. :Athematic and thematic stems

Verbs, like nominals, made a basic distinction based on whether a short, ablauting vowel ''-e-'' or ''-o-'', called the thematic vowel was affixed to the root before the final endings added.Fortson, 2nd Ed. §4.22. In the case of the thematic conjugations, some of the endings differed depending on whether this vowel was present or absent, but by and large the endings were the same for both types. The athematic system is much older and exhibitsProposed endings

At least the following sets of endings existed: * Primary ("present") endings used for: ** Present tense of the indicative mood of imperfective verbs. ** Subjunctive mood * Secondary ("past" or "tenseless") endings used for: ** Past tense of the indicative mood of imperfective verbs. ** Indicative mood of perfective verbs. ** Optative mood * Stative endings used for ** Indicative mood of stative verbs. * Imperative endings used for ** Imperative mood of all verbs. Note that, from a diachronic perspective, the secondary endings were actually the more basic ones, while the primary endings were formed from them by adding a suffix, originally ''-i'' in the active voice and ''-r'' in the middle voice. The more central subfamilies of Indo-European have innovated by replacing the middle-voice ''-r'' with the ''-i'' of the active voice. Traditional accounts say that the first-person singular primary ending is the only form where athematic verbs used a different ending from thematic verbs. Newer accounts by , and are similar, with the proto-forms modernized using laryngeal notation. Sihler, however, notes that many of the most archaic languages have third-person singular forms missing a ''t'' and proposes an alternative ''t''-less thematic ending along with the standard ending.Active eventive endings

Middle eventive endings

Stative endings

A second conjugation has been proposed in Jay Jasanoff'sVerb aspects

Proto-Indo-European verbs belonged to one of three aspect classes: * Stative verbs depicted a state of being. * Eventive verbs expressed events. These could be further divided between: ** Perfective verbs depicting actions viewed as punctual, an entire process without attention to internal details, completed as a whole or not completed at all. No distinction in tense was made. ** Imperfective verbs depicting durative, ongoing or repeated action, with attention to internal details. This included the time of speaking; separate endings were used for present or future events in contrast to past events. The terminology around the stative, perfective and imperfective aspects can be confusing. The use of these terms here is based on the reconstructed meanings of the corresponding forms in PIE and the terms used broadly in linguistics to refer to aspects with these meanings. In traditional PIE terminology, the forms described here as stative, perfective and imperfective are known as the ''perfect'', ''aorist'' and ''present'' systems: * Stative = ''Perfect'' * Perfective = ''Aorist'' * Imperfective = ''Present'' The present/imperfective system in turn can be conjugated in two tenses, described here as present and past but traditionally known as ''present'' and ''imperfect''. The traditional terms are based on the names of the corresponding forms inEventive verbs

The perfective ("aorist") and imperfective ("present") aspect classes are together known as ''eventive'', or verbs that depict events, to distinguish them from ''stative'' (verbs that depict a state of being). Both shared the same conjugation, with some small differences. The main difference was that imperfective verbs allowed the use of special present-tense (primary) endings, while perfective verbs only allowed the default tenseless (secondary) endings. The present tense used the primary eventive endings, and was used specifically to refer to present events, although it could also refer to future events. The past tense referred to past events, and used the secondary eventive endings. Perfective verbs always used the secondary endings, but did not necessarily have a past-tense meaning. The secondary endings were, strictly speaking, tenseless, even in imperfective verbs. This meant that past endings could also be used with a present meaning, if it was obvious from context in some way. This use still occurred in Vedic Sanskrit, where in a sequence of verbs only the first might be marked for present tense (with primary endings), while the remainder was unmarked (secondary endings). If the verbs were subjunctive or optative, the mood markings might likewise be only present on the first verb, with the others not marked for mood (i.e. indicative). In Ancient Greek, Armenian and Indo-Iranian, the secondary endings came to be accompanied by a prefixing particle known as the '' augment'', reconstructed as ''*e-'' or ''*h₁e-''. The function of the augment is unclear (it is usually thought to be connected to the meaning of 'past'), but it was not a fixed part of the inflection as it was in the later languages. In Homeric Greek and Vedic Sanskrit, many imperfect (past imperfective) and aorist verbs are still found lacking the augment; its use became mandatory only in later Greek and Sanskrit. Morphologically, the indicative of perfective verbs was indistinguishable from the past indicative of imperfective verbs, and it is likely that in early stages of PIE, these were the same verb formation. At some point in the history of PIE, the present tense was created by developing the primary endings out of the secondary endings. Not all verbs came to be embellished with these new endings; for semantic reasons, some verbs never had a present tense. These verbs were the perfective verbs, while the ones that did receive a present tense were imperfective.Stative verbs

Stative verbs signified a current state of being rather than events. It was traditionally known as ''perfect'', a name which was assigned based upon the Latin tense before the stative nature of the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) form was fully known. While Latin conflated the static aspect concept with tense, in PIE there was no association with any particular tense. The stative aspect was marked formally with its own personal endings, which differed from the eventives by a root in the singular in ''o''-grade, but elsewhere in zero-grade, and typically by reduplication. Like the perfective verbs, stative verbs were tenseless, and described a state without reference to time. This did not mean that stative verbs referred to permanent states (as in Spanish ''ser'' versus temporary ''estar''), but rather that there was no way to express, within the verbal morphology, whether the state was applicable in the present moment, in the past, or in the future. These nuances were, presumably, expressed using adverbs. In many daughter languages, the stative took on a meaning that implied a previous action that had caused the current state, a meaning which resulted in the Greek perfect. Eventually, by shifting emphasis to the inchoative action, an action that was just started or a state that was just begun prior to the resulting state, the stative generally developed into a past tense (as in Germanic, Latin, and later, Greek). The original ''present'' sense of the IE stative is seen in the Germanic preterite-present verbs such as Gothic ''wait'' "I know" (< PIE *', originally "I am in a state resulting from having seen/found"; cf. Latin ''vidēre'' "to see", Sanskrit ''vinátti'' "he finds"), with exact cognates in Sanskrit ''véda'', Ancient Greek ''oĩda'', and Old Church Slavonic ''vědě'', all of which retain their essentially present tense meaning "I know".Other verbal categories

Voice

Verbs originally had two voices: active andMood

The moods of PIE included indicative, imperative, subjunctive, optative and perhaps injunctive.Indicative

TheImperative

TheSubjunctive

TheOptative

The optative mood was used for wishes or hopes, like the English "may I sleep well". It was formed with an athematic ablauting suffix ''-yéh₁-'' ~ ''-ih₁-'' attached to the zero-grade of the stem. In Vedic Sanskrit, optatives were very rarely found for characterised stems (primary and secondary derivations); most occurrences of the optative are in root verbs. This is taken by Sihler to indicate that the optative was not really a ''mood'' in PIE, but a separate ''verb'', and was thus restricted to being derived directly from roots only, not from already-derived verbs. In addition, it appears that in PIE itself, stative verbs did not have the optative mood; it was limited to eventive verbs. Early Indo-Iranian texts mostly lack attestations of stative optative forms.Injunctive

The place of the injunctive mood, of obscure function, is debated. It takes the form of the bare root in ''e''-grade with secondary endings, without the prefixed augment that was common to forms with secondary endings in these languages. The injunctive was thus entirely without tense marking. This causes Fortson (among others) to suggest that the use of the injunctive was for gnomic expressions (as in Homer) or in otherwise timeless statements (as in Vedic).Verb formation

From any particular root, verbs could be derived in a variety of means. In the most conservative Indo-European languages (e.g. Ancient Greek, Sanskrit, Tocharian, Old Irish), there is a separate set of conjugational classes for each of the tense/aspect categories, with no general relationship obtaining between the class of a given verb in one category relative to another. The oldest stages of these languages (especiallyRoot verbs

The most basic verb formation was derived directly from the root, with no suffix, and expressed the meaning of the root itself. Such "root verbs" could be either athematic or thematic; it was not predictable which type was used. The aspect of a root verb was determined by the root itself, which had its own "root aspect" inherent in the basic meaning of the root. Thus, there were verbal roots whose default meaning was durative, ongoing, or iterative, and verbs derived from them were generally imperfective in aspect. Roots whose meaning was punctiliar or discrete created perfective-aspect verbs. Stative roots were rare; perhaps the only reconstructible stative root verb was "know". There are numerous unexplained surprises in this system, however. The common root meant "to be", which is an archetypically stative notion. Yet, aspect-wise, it was an imperfective root, and thus formed an imperfective root verb , rather than a stative verb.Primary derivations

In early PIE, the aspect system was less well-developed, and root verbs were simply used in their root aspects, with various derivational formations available for expressing more specific nuances. By late PIE, however, as the aspect system evolved, the need had arisen for verbs of a different aspect than that of the root. Several of the formations, which originally formed distinct verbs, gradually came to be used as "aspect switching" derivations, whose primary purpose was to create a verb of one aspect from a root of another aspect. This led to a fundamental distinction in PIE verb formations, between ''primary'' and ''secondary'' formations. Primary formations included the root verbs and the derivational formations that came to be used as aspect switching devices, while secondary formations remained strictly derivational and retained significant semantic value. For example, the secondary suffix derivedSecondary derivations

Secondary verbs were formed either from primary verb roots (so-called ''deverbal verbs'') or from nouns (''denominal verbs'' or ''denominative verbs'') or adjectives (''deadjectival verbs''). (In practice, the term ''denominative verb'' is often used to incorporate formations based on both nouns and adjectives because PIE nouns and adjectives had the same suffixes and endings, and the same processes were used to form verbs from both nouns and adjectives.) Deverbal formations included causative ("I had someone do something"), iterative/inceptive ("I did something repeatedly"/"I began to do something"), desiderative ("I want to do something"). The formation of secondary verbs remained part of the derivational system and did not necessarily have completely predictable meanings (compare the remnants of causative constructions in English — ''to fall'' vs. ''to fell'', ''to sit'' vs. ''to set'', ''to rise'' vs. ''to raise'' and ''to rear''). They are distinguished from the primary formations by the fact that they generally are part of the derivational rather than inflectional morphology system in the daughter languages. However, as mentioned above, this distinction was only beginning to develop in PIE. Not surprisingly, some of these formations have become part of the inflectional system in particular daughter languages. Probably the most common example is the future tense, which exists in many daughter languages but in forms that are not cognate, and tend to reflect either the PIE subjunctive or a PIE desiderative formation. Secondary verbs were always imperfective, and had no corresponding perfective or stative verbs, nor was it possible (at least within PIE) to derive such verbs from them. This was a basic constraint in the verbal system that prohibited applying a derived form to an already-derived form. Evidence from theFormation types

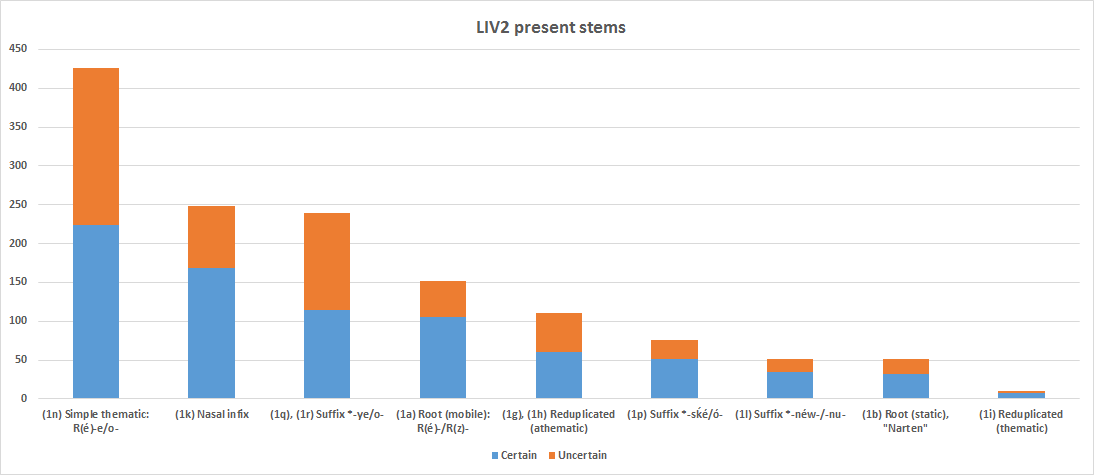

The following gives a list of the most common verb types reconstructed for (late) PIE.Primary imperfective

Root athematic

Also called "simple athematic", this formation derived imperfective verbs directly from a root. It can be divided into two subtypes: # Normal type: ''*(é)-ti'' ~ ''*(∅)-énti''. Alternating between accented ''e''-grade root, and zero-grade root with accent on the endings. # Narten type: ''*(ḗ/é)-ti'' ~ ''*(é)-nti''. Mostly root accent and alternating lengthened/normal grade, or, according to an alternative view, fixed normal grade throughout. The normal type is the most common by far. Examples: '' *h₁ésti''.Root thematic

Also called "simple thematic", it functioned the same as the root athematic verbs. There were also two types: # normal type: ''*(é)-eti'' ~ ''*(é)-onti''. Accented ''e''-grade root. # "''tudati''" type: ''*(∅)-éti'' ~ ''*(∅)-ónti''. Zero-grade root, accent on theme vowel. The "''tudati''" type is named after the Sanskrit verb that typifies this formation. It is much rarer than the normal type. Examples: '' *bʰéreti''.Reduplicated athematic

The root is prefixed with a copy of the initial consonant(s) of the root, separated by a vowel. The accent is fixed on this prefix, but the root grade alternates as in root athematic verbs. The vowel can be either ''e'' or ''i'': # ''e''-reduplication: ''*(é)-(e)-ti'' ~ ''*(é)-(∅)-nti'' # ''i''-reduplication: ''*(í)-(e)-ti'' ~ ''*(í)-(∅)-nti'' Examples: '' *dʰédʰeh₁ti'', '' *stísteh₂ti''.Reduplicated thematic

''*(í)-(∅)-eti'' ~ ''*(í)-(∅)-onti''. Like the athematic equivalent, but the vowel is always ''i'' and the root is always in zero-grade (like in the "''tudati''" type). Examples: '' *sísdeti''.Nasal infix

''*(né)-ti'' ~ ''*(n)-énti''. This peculiar formation consists of an infix ''-né-'' ~ ''-n-'' that is ''inserted'' before final consonant of the zero-grade root, and inflected with athematic inflection. The infix itself ablauts like root athematic verbs. This formation is limited to roots ending in a stop or laryngeal, and containing a non-initial sonorant. This sonorant is always syllabified in the zero-grade, the infix is never syllabic. Examples: '' *linékʷti'', '' *tl̥néh₂ti''.''nu''-suffix

''*(∅)-néw-ti'' ~ ''*(∅)-nu-énti''. Formed with an ablauting athematic suffix ''*-néw-'' ~ ''*-nu-'' attached to the root. These are sometimes considered to be a special case of the nasal-infix type. Examples: '' *tn̥néwti''.''ye''-suffix

This thematic formation exists in two types: # ''*(é)-y-eti'' ~ ''*(é)-y-onti''. Accented root in ''e''-grade. This type was primarily used to form transitive imperfective verbs from intransitive perfective verbs. # ''*(∅)-y-éti'' ~ ''*(∅)-y-ónti''. Zero-grade root with accent on the thematic vowel. This type formed mostly intransitive imperfective verbs, often deponent (occurring only in middle voice). Examples: '' *wr̥ǵyéti'', '' *gʷʰédʰyeti'', '' *spéḱyeti''.''sḱe''-suffix

''*(∅)-sḱ-éti'' ~ ''*(∅)-sḱ-ónti''. Thematic, with zero-grade root and accent on the thematic vowel. This type formed durative, iterative or perhaps inchoative verbs. Examples: '' *gʷm̥sḱéti'', '' *pr̥sḱéti''.''se''-suffix

''*(é)-s-eti'' ~ ''*(é)-s-onti''. Thematic, with accented ''e''-grade root. Examples: '' *h₂lékseti''.Secondary imperfective

''eh₁''-stative

''*(∅)-éh₁-ti'' ~ ''*(∅)-éh₁-n̥ti''. This formed ''secondary'' stative verbs from adjectival roots, perhaps also from adjective stems. The verbs thus created were, nonetheless, imperfective verbs. This suffix was thematicised in most descendants with a ''-ye-'' extension, thus ''-éh₁ye-'' as attested in most daughter languages. It is unclear if the verb ablauted; most indications are that it did not, but there are some hints that the zero-grade did occur in a few places (Latin past participle, Germanic class 3 weak verbs). Some scholars, including the editors of the '' Lexikon der indogermanischen Verben'', believe that the ''eh₁''-stem was originally an aorist stem with 'fientive' meaning ('to become X'), whereas the ''-ye-'' extension created the present with ' essive' meaning, 'to be x'. Examples: '' *h₁rudʰéh₁ti''.''éye''-causative/iterative

''*(o)-éy-eti'' ~ ''*(o)-éy-onti''. Thematic, affixed to the ''o''-grade of the root, with accent on the suffix. This formed''(h₁)se''-desiderative

This thematic suffix formed desiderative verbs, meaning "to want to do". Two formations are attested: # ''*(é)-(h₁)s-eti'' ~ ''*(é)-(h₁)s-onti''. Accented full grade of the root. # ''*(í)-(∅)-(h₁)s-eti'' ~ ''*(í)-(∅)-(h₁)s-onti''. Reduplicated with ''i'', accent on the reduplicated prefix, zero-grade root. Examples: '' *wéydseti'', '' *ḱíḱl̥h₁seti''.''sye''-desiderative

''*(∅)-sy-éti'' ~ ''*(∅)-sy-ónti''. Similar to above, but with an accented thematic vowel and zero-grade root. Examples: '' *bʰuHsyéti''.''ye''-denominative

''*-y-éti'' ~ ''*-y-ónti''. Affixed to noun and adjective stems for a variety of meanings; accent is on the thematic vowel. The thematic vowel of the nominal stem, if any, is retained as ''e'', as is any possible ''-eh₂'' suffix, thus creating the variants ''-eyé-'' and ''-eh₂yé-'', which developed into independent suffixes in many daughter languages.''h₂''-factitive

''*-h₂-ti'' ~ ''*-h₂-n̥ti''. This formed factitive verbs from adjective stems. As above, the thematic vowel was retained, as ''e''. Like the ''eh₁''-stative, this suffix was often extended with ''-ye-'' in the daughter languages, giving ''-h₂ye-''. Examples: '' *néweh₂ti''.''ye''-factitive

''*-y-éti'' ~ ''*-y-ónti''. Very similar to the denominative, but formed from adjectives only. The thematic vowel is retained, but this time as ''o''. The existence of this type in PIE is uncertain.Perfective

Root athematic

''*(é)-t'' ~ ''*(∅)-ént''. The same as root athematic imperfective verbs. Most perfective verbs appear to have been of this type. Examples: '' *gʷémt'', '' *léykʷt'', '' *bʰúHt''.Root thematic

''*(∅)-ét'' ~ ''*(∅)-ónt''. The same as root thematic imperfective verbs. This formation was very rare in PIE, barely any are reconstructable, but became more widespread in the later languages. The formation seemed to have zero-grade of the root and accent on the thematic vowel, like the "''tudati''" type. Examples: '' *h₁ludʰét''.Reduplicated thematic

''*(é)-(∅)-et'' ~ ''*(é)-(∅)-ont''. This formation was maybe even rarer than the root thematic type, only one verb is reconstructable. Examples: '' *wéwket''.''s''-suffix

''*(ḗ)-s-t'' ~ ''*(é)-s-n̥t''. Inflected as the "Narten" athematic type, with lengthened grade in the singular and fixed accent. This suffix was the primary means of deriving perfective verbs from imperfective roots, though it appears that there were not many verbs created that way. The suffix became very productive in many of the descendants. Examples: '' *dḗyḱst'', '' *wḗǵʰst''.Stative

Root

''*(ó)-e'' ~ ''*(∅)-ḗr''. Owing to the rarity of stative roots, this formation was correspondingly rare. Only one verb can be reconstructed. Examples: '' *wóyde''.Reduplicated

''*(e)-(ó)-e'' ~ ''*(e)-(∅)-ḗr''. This was the only way to form new stative verbs. Examples: '' *memóne'', '' *lelóykʷe''.Examples

The following is an example paradigm, based on , of the verb , "leave behind" (athematic nasal-infixed present, root aorist, reduplicated perfect). Two sets of endings are provided for the primary medio-passive forms (subjunctive and primary indicative) — the ''central'' dialects (Indo-Iranian, Greek, Germanic, Balto-Slavic, Albanian, and Armenian) use forms ending in , while the ''peripheral'' dialects (Italic, Celtic, Hittite, and Tocharian) use forms ending in , which are generally considered the original forms. Ringe makes certain assumptions about synchronic PIE phonology that are not universally accepted: # Sievers' Law applies in all positions and to all resonants, including . #Word-final becomes when adjacent to a voiced segment (i.e. vowel or voiced consonant). The effects of the generally accepted synchronic boukólos rule whereby becomes next to or are shown.

The following is an example paradigm, based on , of the verb "carry" in the simple thematic present tense. Two sets of endings are provided for the primary middle forms, as described above. The above assumptions about PIE phonology apply, in addition to a rule that deletes laryngeals which occur in the sequence ''-oRHC'' or ''-oRH#'', where ''R'' stands for any resonant, ''H'' any laryngeal, ''C'' any consonant and ''#'' the end of a word. The most important effect of this rule is to delete most occurrences of in the thematic optative.

Post-PIE developments

The various verb formations came to be reorganised in the daughter languages. The tendency was for various forms to become integrated into a single "paradigm" which combined verbs of different aspects into a coherent whole. This process proceeded in steps: # Combining different forms with similar meanings into a system of three major aspects. The result of this was the so-called "Cowgill–Rix" system described above, which was completed in late PIE, shortly after Tocharian had split off and well after the Anatolian split. At this stage, formations that originally had various purposes had their semantics largely harmonized into one of the aspect classes, with a clear distinction between primary and secondary derivations. These formations, however, were still separate lexical verbs, still sometimes with idiosyncratic meanings, and for a given aspect a root could still form multiple verbs or no verbs in that particular aspect. This is the stage visible in early Vedic Sanskrit. # Combining the various aspects under a single unified verb, with a clear distinction between inflectional and derivational forms. This involved pruning multiple verbs formed from the same root with the same aspect, and creating new verbs for aspects that were missing for certain roots. At this stage a single verb was defined by a set of principal parts, each of which (approximately) defined the type of formation used in each of its aspects. This stage was in process in Vedic Sanskrit and was largely completed in Ancient Greek, although even in this language there are still verbs lacking some of the aspects, as well as occasional multiple formations for the same aspect, with distinct and idiosyncratic meanings. Many remnants of this stage are also found inIn

In the Romance languages, these developments have also occurred, but to a lesser degree. The classes ''-āre'' ''-ēre'' ''-ere'' ''-īre'' remain productive; the fourth (''-īre'') though is generally only marginally productive. The gradual tendency in all of the daughter languages was to proceed through the stages just described, creating a single conjugational system that applied to all tenses and aspects and allowing all verbs, including secondary verbs, to be conjugated in all inflectional categories. Generally, the primary verbs were largely all lumped together into a single conjugation (e.g. the Latin ''-ere'' conjugation), while different secondary-verb formations produced all other conjugations; for the most part, only these latter conjugations were productive in the daughter languages. In most languages, the original distinction between primary and secondary verbs was obscured to some extent, with some primary verbs scattered among the nominally secondary/productive conjugations. Germanic is perhaps the family with the clearest primary/secondary distinction: Nearly all "strong verbs" are primary in origin while nearly all "weak verbs" are secondary, with the two classes clearly distinguished in their past-tense and past-participle formations. In Greek, the difference between the present, aorist, and perfect, when used outside of the indicative (i.e. in the subjunctive, optative, imperative, infinitive, and participles) is almost entirely one of

Developments of the various verb classes

NOTE: A blank space means theGermanic

In Germanic, all eventive verbs acquired primary indicative endings, regardless of the original aspectual distinction. These became the "present tense" of Germanic. Almost all presents were converted to the thematic inflection, using the singular (''e''-grade) stem as the basis. A few "''tudati''"-type thematic verbs survived (''*wiganą'' "to battle", ''*knudaną'' "to knead"), but these were usually regularised by the daughter languages. Of the athematic verbs, only three verbs are reconstructable: * ''*wesaną'' "to be" (present ''*immi'', ''*isti'', from imperfective ''*h₁ésmi'', ''*h₁ésti''), * ''*beuną'' "to be, to become" (present ''*biumi'', ''*biuþi'', from perfective ''**bʰewHm'', ''**bʰewHt'') * ''*dōną'' "to do, to put" (present ''*dōmi'', ''*dōþi'', from perfective ''*dʰéh₁m̥'', ''*dʰéh₁t''). The merger of perfective and imperfective verbs brought root verbs in competition with characterised verbs, and the latter were generally lost. Consequently, Germanic has no trace of the ''s''-suffix perfectives, and very few characterised primary imperfectives; by far the most primary verbs were simple root verbs. Some imperfectives with the ''ye''-suffix survived into Proto-Germanic, as did one nasal-infix verb (''*standaną'' "to stand" ~ ''*stōþ''), but these were irregular relics. Other characterised presents were preserved only as relic formations and generally got converted to other verbal formations. For example, the present ''*pr̥skéti'' "to ask, to question" was preserved as Germanic ''*furskōną'', which was no longer a simple thematic verb, but had been extended with the class 2 weak suffix ''-ō-''. Stative verbs became the "past tense" or "preterite tense" in Germanic, and new statives were generally formed to accompany the primary eventives, forming a single paradigm. A dozen or so primary statives survived, in the form of the " preterite-present verbs". These retained their stative (in Germanic, past or preterite) inflection, but did not have a past-tense meaning. The past tense ("imperfect") of the eventive verbs was entirely lost, having become redundant in function to the old statives. Only one single eventive past survives, namely of ''*dōną'': ''*dedǭ'', ''*dedē'', from the past reduplicated imperfective ''*dʰédʰeh₁m̥'', ''*dʰédʰeh₁t''. Secondary eventives (causatives, denominatives etc.) did not have any corresponding stative in PIE and did not acquire one in Germanic. Instead, an entirely novel formation, the so-called "dental past", was formed to them (e.g. ''*satjaną'' "to set" ~ ''*satidē''). Thus, a clear distinction arose between "strong verbs" or primary verbs, which had a past tense originating from the statives, and "weak verbs" or secondary verbs, whose past tense used the new dental suffix. The original primary statives (preterite-presents) also used the dental suffix, and a few primary ''ye''-suffix presents also came to use the weak past rather than the strong past, such as ''*wurkijaną'' "to work" ~ ''*wurhtē'' and ''*þunkijaną'' "to think, to consider" ~ ''*þunhtē''. However, these verbs, having no secondary derivational suffix, attached the dental suffix directly to the root with no intervening vowel, causing irregular changes through the Germanic spirant law. Ending-wise, the strong and weak pasts converged on each other; the weak past used descendants of the secondary eventive endings, while the strong past preserved the stative endings only in the singular, and used secondary eventive endings in the dual and plural.Balto-Slavic

The stative aspect was reduced to relics already in the Balto-Slavic, with very little of it reconstructable. The aorist and indicative past tense merged, creating the Slavic aorist. Baltic lost the aorist, while it survived in Proto-Slavic. Modern Slavic languages have since mostly lost the aorist, but it survives in Bulgarian, Macedonian, Serbo-Croatian and Sorbian. Slavic innovated a new imperfect tense, which appeared in Old Church Slavonic and still exists in the same languages as the aorist. A new past tense was also created in the modern languages to replace or complement the aorist and imperfect, using a periphrastic combination of the copula and the so-called "l-participle", originally a deverbal adjective. In many languages today, the copula was dropped in this formation, turning the participle itself into the past tense. The Slavic languages innovated an entirely new aspectual distinction between imperfective and perfective verbs, based on derivational formations.See also

* Sanskrit verbs *Notes

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Proto-Indo-European Verb