P.K. Van Der Byl on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Pieter Kenyon Fleming-Voltelyn van der Byl (11 November 1923 – 15 November 1999) was a

Pieter Kenyon Fleming-Voltelyn van der Byl but his studies were interrupted by war in 1941.Obituary: Pieter van der Byl: Rich, white aristocrat behind Rhodesia's bid to stop black rule

Rhodesian personalities Whitehead was of the opinion that Van der Byl had "adopted" this accent, in common with others who heard him like Denis Hills, who wrote of Van der Byl having "a flow of mannered phrases which he delivers in a flawed Guards officer accent".''Rebel People''

Denis Hills, George Allen and Unwin, 1978, page 204 Thi

Rhodesian newspaper cartoon

shows another reaction. This personal characteristic was intensely irritating to many people including South African government ministers, but Van der Byl's aristocratic mannerisms appeared uncontentious to many Rhodesian whites. They believed that his "nasal drawl" was the product of his time as an officer in the

James P. Barber, Institute of Race Relations, 1967, page 291 By the end of 1964, Van der Byl and his Ministry had control of broadcasting in Rhodesia.Robert Blake, "A History of Rhodesia", Eyre Methuen, 1977, p. 367 Speaking in Parliament he described the aims of his Department as "not merely to disseminate information from an interesting point of view but to play its part in fighting the propaganda battle on behalf of the country". He defined propaganda as "simply the propagation of the faith and the belief in any particular ideology or thing", and also stated that the department would seek the "resuscitation of the determination of the European to survive and fight for his rights".

" Michael Hartnack, ''

BBC News online 'On this day'

The propaganda circulated by his Ministry (typically including references to "happy, smiling natives") was considered laughable. Visiting British journalist

/ref> His propaganda strategy became increasingly unsuccessful abroad, where Van der Byl alienated many of the foreign journalists and politicians that he came into contact with.

Max Hastings, Macmillan, 2000, pages 185-189 While still popular with the Rhodesian Front members, he was criticised at the 1972 Party Congress for his lack of success in improving Rhodesia's image around the world; however, he retained the confidence of Ian Smith and was kept on in a government reshuffle on 24 May 1973. That winter saw him promote a new Broadcasting Bill to transfer control of the monopoly

Gradually the South Africans grew unwilling to help Rhodesia. The remaining 200 South African policemen transferred to help in the guerilla war were removed suddenly in August 1975, a move which appeared to precede even more disengagement. Van der Byl responded in a speech on 8 August which asserted that "The terrorists who are trained and equipped outside our border and who invade our country with the willing help of other governments are here for a much wider purpose than the overthrow of Rhodesia. They are here to represent a force which sees Rhodesia as just one more stepping stone to victory over South Africa because they see South Africa as a vital key to the security of America, Europe and the rest of the western world.""Relations under strain at Pretoria meeting", ''The Times'', Saturday, 9 August 1975, p. 1

When the Rhodesian government held talks with the African National Council on the railway bridge across the

Gradually the South Africans grew unwilling to help Rhodesia. The remaining 200 South African policemen transferred to help in the guerilla war were removed suddenly in August 1975, a move which appeared to precede even more disengagement. Van der Byl responded in a speech on 8 August which asserted that "The terrorists who are trained and equipped outside our border and who invade our country with the willing help of other governments are here for a much wider purpose than the overthrow of Rhodesia. They are here to represent a force which sees Rhodesia as just one more stepping stone to victory over South Africa because they see South Africa as a vital key to the security of America, Europe and the rest of the western world.""Relations under strain at Pretoria meeting", ''The Times'', Saturday, 9 August 1975, p. 1

When the Rhodesian government held talks with the African National Council on the railway bridge across the

''The Times'', Monday, 20 October 1975, p. 4) led to extreme unpopularity with the South African government, and he did not attend talks with South African Prime Minister

Issues 393-407; Issues 409-418, 1977, page 4 When, on 26 August 1976, the South African government announced the withdrawal of all its military helicopter crews from Rhodesia, Van der Byl was outspoken in his criticism and Vorster was reported to have refused to have anything to do with "that dreadful man Van der Byl." Smith decided that he "clearly ... had no option" and on 9 September 1976 executed a sudden cabinet reshuffle that ended Van der Byl's tenure as Defence Minister. Smith claimed the South African dislike of Van der Byl was partly motivated by the memory of his father, who had been in opposition to the National Party.

/ref> for resisting ZANU-PF taking power by force if it lost the election. Walls insisted that ZANU-PF would not win the election, and that ZANU's illegal and massive intimidation of voters showed it would continue this behavior if it lost. When ZANU won, both Smith and Van der Byl believed ZANU's atrocities had invalidated its victory, and that the Army should step in to prevent Mugabe taking over. Walls took the view that it was already too late, and while the others wished for some move, they were forced to concede to this view.

Rhodesia

Rhodesia ( , ; ), officially the Republic of Rhodesia from 1970, was an unrecognised state, unrecognised state in Southern Africa that existed from 1965 to 1979. Rhodesia served as the ''de facto'' Succession of states, successor state to the ...

n politician who served as his country's Foreign Minister from 1974 to 1979 as a member of the Rhodesian Front

The Rhodesian Front (RF) was a conservative political party in Southern Rhodesia, subsequently known as Rhodesia. Formed in March 1962 by white Rhodesians opposed to decolonisation and majority rule, it won that December's general election and s ...

(RF). A close associate of Prime Minister Ian Smith

Ian Douglas Smith (8 April 191920 November 2007) was a Rhodesian politician, farmer, and fighter pilot who served as Prime Minister of Rhodesia (known as Southern Rhodesia until October 1964 and now known as Zimbabwe) from 1964 to 1979. He w ...

, Van der Byl opposed attempts to compromise with the British government and domestic black nationalist opposition on the issue of majority rule throughout most of his time in government. However, in the late 1970s he supported the moves which led to majority rule and internationally recognised independence for Zimbabwe

file:Zimbabwe, relief map.jpg, upright=1.22, Zimbabwe, relief map

Zimbabwe, officially the Republic of Zimbabwe, is a landlocked country in Southeast Africa, between the Zambezi and Limpopo Rivers, bordered by South Africa to the south, Bots ...

.

Van der Byl was born and raised in Cape Town

Cape Town is the legislature, legislative capital city, capital of South Africa. It is the country's oldest city and the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. Cape Town is the country's List of municipalities in South Africa, second-largest ...

, the son of the South African politician P V van der Byl, and served in the Middle East and Europe during the Second World War. After a high-flying international education, he moved to the self-governing

Self-governance, self-government, self-sovereignty or self-rule is the ability of a person or group to exercise all necessary functions of regulation without intervention from an external authority. It may refer to personal conduct or to any ...

British colony of Southern Rhodesia

Southern Rhodesia was a self-governing British Crown colony in Southern Africa, established in 1923 and consisting of British South Africa Company (BSAC) territories lying south of the Zambezi River. The region was informally known as South ...

in 1950 to manage family farms. He went into politics in the early 1960s through his involvement with farming trade bodies, and became a government minister responsible for propaganda. One of the leading agitators for Rhodesia's Unilateral Declaration of Independence

Rhodesia's Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) was a statement adopted by the Cabinet of Rhodesia on 11 November 1965, announcing that Rhodesia (previously Southern Rhodesia), a British crown colony in southern Africa that had respon ...

in 1965, Van der Byl was afterwards responsible for introducing press censorship. He was unsuccessful in his attempt to persuade international opinion to recognise Rhodesia, but was popular among members of his own party.

Promoted to the cabinet

Cabinet or The Cabinet may refer to:

Furniture

* Cabinetry, a box-shaped piece of furniture with doors and/or drawers

* Display cabinet, a piece of furniture with one or more transparent glass sheets or transparent polycarbonate sheets

* Filin ...

in 1968, Van der Byl became a spokesman for the Rhodesian government and crafted a public image as a die-hard supporter of continued white minority rule. In 1974 he was made Minister of Foreign Affairs and Defence at a time when Rhodesia's only remaining ally, South Africa, was supplying military aid. His extreme views and brusque manner made him a surprising choice for a diplomat (a November 1976 profile in ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British Newspaper#Daily, daily Newspaper#National, national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its modern name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its si ...

'' described him as "a man calculated to give offence"David Spanier, "Rhodesia's Foreign Minister a man calculated to give offence", ''The Times'', Thursday 4 November 1976, page 7). After offending the South African government, Van der Byl was removed from the Defence Ministry.

In the late 1970s Van der Byl was willing to endorse the Smith government's negotiations with moderate black nationalist leaders and rejected attempts by international missions to broker an agreement. He served in the short-lived government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a State (polity), state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive (government), execu ...

of Zimbabwe Rhodesia

Zimbabwe Rhodesia (), alternatively known as Zimbabwe-Rhodesia, also informally known as Zimbabwe or Rhodesia, was a short-lived unrecognised sovereign state that existed from 1 June 1979 to 18 April 1980, though it lacked international recog ...

in 1979, following the Internal Settlement

The Internal Settlement (also called the Salisbury Agreement HC Deb 04 May 1978 vol 949 cc 455–592) was an agreement which was signed on 3 March 1978 between Prime Minister of Rhodesia Ian Smith and the moderate African nationalist leaders comp ...

. After the country's reconstitution as Zimbabwe in 1980, Van der Byl remained in politics and close to Ian Smith; he loudly attacked former RF colleagues who had gone over to support Robert Mugabe

Robert Gabriel Mugabe (; ; 21 February 1924 – 6 September 2019) was a Zimbabwean revolutionary and politician who served as Prime Minister of Zimbabwe from 1980 to 1987 and then as President from 1987 to 2017. He served as Leader of th ...

. He retired to South Africa after the Mugabe government abolished the parliamentary seats reserved for whites in 1987, and died in 1999 at the age of 76.

Family and early life

Van der Byl was born inCape Town

Cape Town is the legislature, legislative capital city, capital of South Africa. It is the country's oldest city and the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. Cape Town is the country's List of municipalities in South Africa, second-largest ...

, the son of Joyce Clare Fleming, a Scot, and Dutch-descended Major Pieter Voltelyn Graham van der Byl

Major Pieter Voltelyn Graham "P. V." van der Byl MC (21 February 1889 – 21 January 1975) was a South African soldier and statesman. In South African politics, he was a member of the liberal South African Party and then the United Party from ...

, a member of Jan Smuts

Field Marshal Jan Christian Smuts, (baptismal name Jan Christiaan Smuts, 24 May 1870 11 September 1950) was a South African statesman, military leader and philosopher. In addition to holding various military and cabinet posts, he served as P ...

' South African cabinet during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. Like his father, Van der Byl was educated at the Diocesan College

The Diocesan College (commonly known as Bishops) is a private, English medium, boarding and day high school for boys situated in the suburb of Rondebosch in Cape Town in the Western Cape province of South Africa. The school was established o ...

in RondeboschRhodesian PersonalitiesPieter Kenyon Fleming-Voltelyn van der Byl but his studies were interrupted by war in 1941.Obituary: Pieter van der Byl: Rich, white aristocrat behind Rhodesia's bid to stop black rule

Dan van der Vat

Daniel Francis Jeroen van der Vat (28 October 1939 – 9 May 2019) was a journalist, writer and military historian, with a focus on naval history.

Born in Alkmaar, North Holland, Van der Vat grew up in the German- occupied Netherlands. He attended ...

, ''The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in Manchester in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'' and changed its name in 1959, followed by a move to London. Along with its sister paper, ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardi ...

'', 30 November 1999, p. 22 He served with the South African Army

The South African Army is the principal Army, land warfare force of South Africa, a part of the South African National Defence Force (SANDF), along with the South African Air Force, South African Navy and South African Military Health Servi ...

during the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

and served with the British 7th Queen's Own Hussars

The 7th Queen's Own Hussars was a cavalry regiment in the British Army, first formed in 1689. It saw service for three centuries, including the First World War and the Second World War. The regiment survived the immediate post-war reduction in ...

; he saw active service in the Middle East, Italy and Austria.

After being demobilised

Demobilization or demobilisation (see American and British English spelling differences, spelling differences) is the process of standing down a nation's armed forces from combat-ready status. This may be as a result of victory in war, or becaus ...

, Van der Byl studied law at Pembroke College, Cambridge

Pembroke College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge, England. The college is the third-oldest college of the university and has over 700 students and fellows. It is one of the university's larger colleges, with buildings from ...

,List of Members of Cambridge University where his aristocratic manner stood out. "P. K." was always elegantly dressed and coiffured, and acquired the nickname "the Piccadilly

Piccadilly () is a road in the City of Westminster, London, England, to the south of Mayfair, between Hyde Park Corner in the west and Piccadilly Circus in the east. It is part of the A4 road (England), A4 road that connects central London to ...

Dutchman". He obtained a Third-class degree in his Part II Law examinations in 1947,Historical Register of Cambridge University, supplement 1941–1950 (Cambridge University Press, 1952), p. 208 and went on from Cambridge to study at Harvard University

Harvard University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the History of the Puritans in North America, Puritan clergyma ...

Graduate School of Business Administration from 1947 to 1948 (although he did not obtain a degree at the latter).Harvard Alumni Directory 1986, p. 1256. Van der Byl is counted in the Class of 1949. He also studied at the University of the Witwatersrand

The University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg (), commonly known as Wits University or Wits, is a multi-campus Public university, public research university situated in the northern areas of central Johannesburg, South Africa. The universit ...

in South Africa.: The main players

One of the most conspicuous features of Van der Byl was his manner of speech: although his ancestry was Cape Dutch and his early life was in Cape Town, South Africa, he had what were described (by Chris Whitehead, editor of '' Rhodesians Worldwide'') as "what he thought was an aristocratic English nasal drawl and imperial English mannerisms".PK, Chris WhiteheadRhodesian personalities Whitehead was of the opinion that Van der Byl had "adopted" this accent, in common with others who heard him like Denis Hills, who wrote of Van der Byl having "a flow of mannered phrases which he delivers in a flawed Guards officer accent".''Rebel People''

Denis Hills, George Allen and Unwin, 1978, page 204 Thi

Rhodesian newspaper cartoon

shows another reaction. This personal characteristic was intensely irritating to many people including South African government ministers, but Van der Byl's aristocratic mannerisms appeared uncontentious to many Rhodesian whites. They believed that his "nasal drawl" was the product of his time as an officer in the

Hussars

A hussar, ; ; ; ; . was a member of a class of light cavalry, originally from the Kingdom of Hungary during the 15th and 16th centuries. The title and distinctive dress of these horsemen were subsequently widely adopted by light cavalry ...

and his Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a List of cities in the United Kingdom, city and non-metropolitan district in the county of Cambridgeshire, England. It is the county town of Cambridgeshire and is located on the River Cam, north of London. As of the 2021 Unit ...

education: William Higham described him as "a popular Minister of Defence who, despite his British upper crust accent – undoubtedly honed during his swashbuckling career as an officer in the hussars – hailed from a noble Cape family."

Move to Rhodesia

Van der Byl moved toSouthern Rhodesia

Southern Rhodesia was a self-governing British Crown colony in Southern Africa, established in 1923 and consisting of British South Africa Company (BSAC) territories lying south of the Zambezi River. The region was informally known as South ...

in 1950 to manage some of his family's tobacco farming interests, hoping to make his own fortune. Having visited the country many times as a youth, he remarked that after reading about the profits to be made from tobacco he "suddenly got a rush of blood to the crotch about the tobacco boom and decided I was going to go up there and make the family fortune in a place I liked and wanted to be in." He welcomed the move as it allowed him to indulge his hobby of big game hunting

Big-game hunting is the hunting of large game animals for Trophy hunting, trophies, taxidermy, meat, and commercially valuable animal product, animal by-products (such as horn (anatomy), horns, antlers, tusks, bones, fur, body fat, or special o ...

: in that year in Angola

Angola, officially the Republic of Angola, is a country on the west-Central Africa, central coast of Southern Africa. It is the second-largest Portuguese-speaking world, Portuguese-speaking (Lusophone) country in both total area and List of c ...

, then under Portuguese rule, he set a world record for the biggest elephant shot, which stood until 1955."Pieter van der Byl" (obituary), ''The Times'', 10 January 2000, p. 19

In 1957 Van der Byl was made a Director of the United Dominions Corporation (Rhodesia) Ltd, having already become an active member of the Rhodesia Tobacco Association. In 1956, he was elected by the members of the Selous–Gadzema

Gadzema is a village in the province of Mashonaland West, Zimbabwe. It is located about 110 km south-west of Harare on the main Harare-Bulawayo railway line. The village grew up around the railway station that was built on the line. It was na ...

district to represent them on the Tobacco Association council. He was also Deputy Chair of the Selous Farmers' Association in 1957. His first involvement in government was in 1960 when the Rhodesia Tobacco Association made him one of their representatives on the National Native Labour Commission, on which he served for two years. In 1961, he also represented the Rhodesia Tobacco Association on the council of the Rhodesian National Farmers' Union."Who's Who of Southern Africa 1971", Rhodesia, Central and East Africa Section, Combined Publishers (Pty.) Ltd, Johannesburg 1971, p. 1286–154 He was recognised as a leading spokesman for Rhodesian tobacco farmers.

Dominion Party politician Winston Field

Winston Joseph Field (6 June 1904 – 17 March 1969) was a British politician who served as the seventh Prime Minister of Southern Rhodesia. Field was a former Dominion Party MP who founded the Rhodesian Front political party with Ian Smith. ...

had also led the Rhodesia Tobacco Association, and Van der Byl agreed with him on politics in general. He joined the Rhodesian Front

The Rhodesian Front (RF) was a conservative political party in Southern Rhodesia, subsequently known as Rhodesia. Formed in March 1962 by white Rhodesians opposed to decolonisation and majority rule, it won that December's general election and s ...

when it was set up under Field's leadership. At the 1962 general election, Van der Byl was elected comfortably to the Legislative Assembly for the Hartley constituency, a rural area to the south-west of Salisbury

Salisbury ( , ) is a city status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and civil parish in Wiltshire, England with a population of 41,820, at the confluence of the rivers River Avon, Hampshire, Avon, River Nadder, Nadder and River Bourne, Wi ...

.''Source Book of Parliamentary Elections and Referenda in Southern Rhodesia 1898–1962'' ed. by F.M.G. Willson (Department of Government, University College of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, Salisbury, 1963), p. 197

Political career

Ministerial office

In 1963,Winston Field

Winston Joseph Field (6 June 1904 – 17 March 1969) was a British politician who served as the seventh Prime Minister of Southern Rhodesia. Field was a former Dominion Party MP who founded the Rhodesian Front political party with Ian Smith. ...

appointed Van der Byl as a junior government whip

A whip is a blunt weapon or implement used in a striking motion to create sound or pain. Whips can be used for flagellation against humans or animals to exert control through pain compliance or fear of pain, or be used as an audible cue thro ...

, and on 16 March 1964 he was made Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Justice with responsibility for the Information Service."Holders of Administrative and Ministerial Office 1894–1964 and Members of the Legislative Council 1899–1923 and the Legislative Assembly 1924–1964" by F.M.G. Willson and G.C. Passmore, University College of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, 1965. Although the Van der Byl family were identified as strongly liberal in South African politics, he became identified with the right wing of the party and helped to depose Field from the premiership in early April 1964, when Field failed to persuade the British government to grant Southern Rhodesia its independence. The new Prime Minister, Ian Smith

Ian Douglas Smith (8 April 191920 November 2007) was a Rhodesian politician, farmer, and fighter pilot who served as Prime Minister of Rhodesia (known as Southern Rhodesia until October 1964 and now known as Zimbabwe) from 1964 to 1979. He w ...

, appointed him Deputy Minister for Information. At this time, Van der Byl's chief adviser was a South African called Ivor Benson

Ivor Benson (November 1907 – January 1993) was a journalist, right-wing essayist, anti-communist and racist conspiracy theorist. From 1964 to 1966 he was a Rhodesian government official and censor. He strongly supported apartheid in South Afric ...

, who also served as press censor. Benson believed that an international communist conspiracy was plotting to overthrow white rule in Rhodesia.

Speaking in the Legislative Assembly on 12 August 1964 he attacked proposals for greater independence for broadcasters by referring to what he perceived to be the social effect in Britain:

:To suggest that the BBC

The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is a British public service broadcaster headquartered at Broadcasting House in London, England. Originally established in 1922 as the British Broadcasting Company, it evolved into its current sta ...

, forming opinion in the minds of the people of England, has been an influence for good in any way, when you consider the criminality of large areas of London; when you consider the Mods and Rockers

Mods and rockers were two conflicting British youth subcultures of the late 1950s to mid 1960s. Media coverage of the two groups fighting in 1964 sparked a moral panic about British youth, and they became widely perceived as violent, unruly ...

, and all those other things; when you consider the total moral underminings which have been taking place in England, much to all our distress, in the last fifteen to twenty years, the Hon. Member can hardly bring that up as an argument in favour of the freedom of broadcasting. ''Rhodesia: The Road to Rebellion''"> ''Rhodesia: The Road to Rebellion''James P. Barber, Institute of Race Relations, 1967, page 291 By the end of 1964, Van der Byl and his Ministry had control of broadcasting in Rhodesia.Robert Blake, "A History of Rhodesia", Eyre Methuen, 1977, p. 367 Speaking in Parliament he described the aims of his Department as "not merely to disseminate information from an interesting point of view but to play its part in fighting the propaganda battle on behalf of the country". He defined propaganda as "simply the propagation of the faith and the belief in any particular ideology or thing", and also stated that the department would seek the "resuscitation of the determination of the European to survive and fight for his rights".

1965 election

In May 1965 the Rhodesian Front government went to the country in ageneral election

A general election is an electoral process to choose most or all members of a governing body at the same time. They are distinct from By-election, by-elections, which fill individual seats that have become vacant between general elections. Gener ...

with Van der Byl one of the leading campaigners. Discussion of unilaterally declaring independence had already begun. Van der Byl argued that only a small fraction of Rhodesian business opposed it; however, his campaign speeches typically included an argument against business involvement in politics. He cited Johannesburg

Johannesburg ( , , ; Zulu language, Zulu and Xhosa language, Xhosa: eGoli ) (colloquially known as Jozi, Joburg, Jo'burg or "The City of Gold") is the most populous city in South Africa. With 5,538,596 people in the City of Johannesburg alon ...

mining interests' support for the Progressive Party in South Africa, big business support for the Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party ( or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported the ideology of Nazism. Its precursor ...

in Germany, and the Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

revolution in Russia being financed by United States big business.Larry W. Bowman, "Politics in Rhodesia: White Power in an African State", Harvard University Press, 1973, p. 80, citing ''Rhodesia Herald'', 30 April 1965 and 5 May 1965

The Rhodesian Front won a landslide victory, winning every single one of the 50 constituencies which had predominantly European voters. At the Rhodesian Front Congress of August 1965, party members strongly attacked the press for failing to support the government. A demand for it to be made compulsory for all political articles to be signed by the author met with Van der Byl's approval.''Rhodesia: The Road to Rebellion'' by James Barber (Oxford University Press, 1967), p. 283

UDI

Within the government, Van der Byl was one of the loudest voices urging Ian Smith to proceed to aUnilateral Declaration of Independence

A unilateral declaration of independence (UDI) or "unilateral secession" is a formal process leading to the establishment of a new state by a subnational entity which declares itself independent and sovereign without a formal agreement with the ...

. He angrily denounced the threat of sanctions from Britain, saying on 4 May 1965 that economic destruction of Rhodesia would mean total economic destruction of Zambia

Zambia, officially the Republic of Zambia, is a landlocked country at the crossroads of Central Africa, Central, Southern Africa, Southern and East Africa. It is typically referred to being in South-Central Africa or Southern Africa. It is bor ...

, formerly Northern Rhodesia. This statement was interpreted as a military threat by David Butler, the Leader of the Opposition."New warning by Smith on independence", ''The Times'', Wednesday 5 May 1965, p. 9 Van der Byl was given the task of selling the UDI to Rhodesian whites and to world opinion. In September 1965, it was announced that he would tour the United Kingdom to promote Rhodesian independence. According to David Steel

David Martin Scott Steel, Baron Steel of Aikwood (born 31 March 1938) is a retired Scottish politician. Elected as Member of Parliament (United Kingdom), Member of Parliament for Roxburgh, Selkirk and Peebles (UK Parliament constituency), Roxb ...

, he claimed then that France and the United States would lead the international recognition of the UDI government.David Steel, "I told you so from the start", ''The Times'', Thursday 6 March 1980, p. 16 He was appointed Deputy Minister of Information on 22 OctoberRhodesia Government Gazette, vol. 43 (1965) and so was present at, but did not sign, the Unilateral Declaration of Independence

A unilateral declaration of independence (UDI) or "unilateral secession" is a formal process leading to the establishment of a new state by a subnational entity which declares itself independent and sovereign without a formal agreement with the ...

on 11 November 1965.

Van der Byl was greeted by a speech strongly critical of the Rhodesian government from the Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the Primus inter pares, ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the bishop of the diocese of Canterbury. The first archbishop ...

, Michael Ramsey

Arthur Michael Ramsey, Baron Ramsey of Canterbury (14 November 1904 – 23 April 1988), was a British Anglican bishop and life peer. He served as the 100th Archbishop of Canterbury in the Church of England. He was appointed on 31 May 1961 and ...

, who supported the use of armed force to bring the Rhodesians in line with United Kingdom policy on decolonisation. He responded by comparing the speech to "the tragic connivance at the destruction of Czechoslovakia in exchange for the useless appeasement at Munich in 1938"."Speech deplored by Minister", ''The Times'', Thursday 28 October 1965, p. 12 Van der Byl's response used the phrase "kith and kin" to refer to the ethnic links between the white Rhodesians and the people of the United Kingdom. He saw no contradiction between signing a letter declaring "constant loyalty" to the Queen and declaring independence a few days later; the Rhodesian Government was careful at the time of UDI to state its continued loyalty to the British Crown, though it later declared Rhodesia a republic.

Despite his enthusiasm for propaganda, Van der Byl was outraged when the BBC subsequently set up a radio station at Francistown

Francistown is the second-largest city in Botswana, with a population of about 103,417 inhabitants and 147,122 inhabitants in its agglomeration at the 2022 census. It is located in eastern Botswana, about north-northeast from the capital, Gabo ...

in Botswana which broadcast for 27 months, criticising UDI and urging Rhodesians to revoke it. He was later to claim the station was inciting violence,Letter from P.K. van der Byl to ''The Times'' published on Wednesday, 25 January 1978, p. 17 although this was denied by some who had been regular listeners.Letter from H.C. Norwood to ''The Times'' published on Monday, 20 February 1978, p. 15 On 26 January 1966, two months after the UDI, Van der Byl was willing to be quoted as saying that Rhodesian Army troops would follow a "scorched earth" policy should the United Kingdom send in troops, comparing their position to that of the Red Army when Nazi forces invaded the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

in 1941. He was highly critical of Harold Wilson

James Harold Wilson, Baron Wilson of Rievaulx (11 March 1916 – 23 May 1995) was a British statesman and Labour Party (UK), Labour Party politician who twice served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, from 1964 to 1970 and again from 197 ...

, describing him as a "highly dangerous, uninformed and conceited little man.""'Scorched Earth' in Rhodesia if Britain sends troops", ''The Times'', Thursday, 27 January 1966, p. 10

Censorship

Internally, his policy was enforced through Ministry control of TV and radio and through censorship of newspapers. From 31 December 1965, the Ministry of Information expanded its brief and was renamed the Ministry of Information, Immigration and Tourism, which meant that it was also responsible for deciding whether to grant or revoke permits to visit Rhodesia. Several foreign journalists were expelled: John Worrall, correspondent for ''The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in Manchester in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'' and changed its name in 1959, followed by a move to London. Along with its sister paper, ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardi ...

'', went in January 1969. '' The Rhodesia Herald'', then in opposition to both the Rhodesian Front and UDI, frequently appeared with large white spaces on its news pages where censored stories had been placed. Stories and editorials personally critical of Van der Byl were immediately removed.

Censorship was tightened still further on 8 February 1966 when it was made illegal to indicate where material had been removed. The censor was also given the power to alter existing material or to move it around the newspaper. Dr Ahrn Palley

Ahrn Palley (13 February 1914 – 6 May 1993) was an Independent (politician), independent politician in Rhodesia who criticised the Ian Smith, Smith administration and the Unilateral Declaration of Independence (Rhodesia), Unilateral Declarati ...

, the lone white opposition MP, described the powers as "censorship gone mad", and insisted that there would no longer be any guarantee that anything published in the newspapers was authentic. Van der Byl responded by saying that the new measures were a reflection on the newspapers which had made such powers necessary."Drastic powers for the Rhodesian Censor", ''The Times'', Wednesday, 9 February 1966, p. 10 In 1967 Van der Byl was reported by Malcolm Smith, the former editor of the ''Herald'', as remarking that a high degree of self-censorship Self-censorship is the act of censoring or classifying one's own discourse, typically out of fear or deference to the perceived preferences, sensibilities, or infallibility of others, and often without overt external pressure. Self-censorship is c ...

was required, and support for the government was essential.Malcolm Smith, "How censorship has affected the Rhodesian press", ''The Times'', Tuesday, 7 November 1967, p. 11

''The Herald'' (and the ''Bulawayo Chronicle'') defied the restrictions, boldly printing blank spaces which identified removed material. Van der Byl personally visited the newspaper offices on the day the new regulations came in to warn the staff that if the paper was printed as proposed, they would "publish at your peril." However the papers continued to appear with identifiable censorship in defiance of the government, and in 1968 the regulations were scrapped.

Deportation

Shortly after UDI, 46 academics working at University College, a racially non-segregated institution, in Rhodesia wrote to ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British Newspaper#Daily, daily Newspaper#National, national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its modern name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its si ...

'' in London, denouncing the move. Officers of the British South Africa Police

The British South Africa Police (BSAP) was, for most of its existence, the police force of Southern Rhodesia and Rhodesia (renamed Zimbabwe in 1980). It was formed as a paramilitary force of mounted infantrymen in 1889 by Cecil Rhodes' Britis ...

visited many of those who had signed to search their houses. Shortly afterwards, the residence permit of one of the academics came up for renewal, which would normally be automatic. In fact, it was revoked and the academic was deported. Van der Byl was the responsible minister and all but admitted that the reason was his opposition to UDI.Christopher Hill, "The crisis facing Rhodesia's non-racial university", ''The Times'', Monday, 8 August 1966, p. 9

Van der Byl's strategy seemed to work at home, with many Rhodesians remaining unaware until the end just how much was their country's vulnerability and isolation. ''The Times'' was later to describe him as a "skilled propagandist who believed his own propaganda." When sanctions on Rhodesia were confirmed in January 1967, Van der Byl compared their situation with Spain following World War II, saying that the isolation of Spain had not stopped it from becoming one of the most advanced and economically successful countries in Europe. However, when Van der Byl made informal approaches in April 1966 to see if he might visit Britain "for social reasons" during a tour of Europe, the Commonwealth Relations Office

The secretary of state for Commonwealth relations was a secretary of state in the Government of the United Kingdom, responsible for dealing with the United Kingdom's relations with members of the Commonwealth of Nations (its former colonies). The ...

replied that he would not be recognised as enjoying any form of recognition or immunity."Rebuff to a Rhodesian Minister", ''The Times'', Tuesday, 3 May 1966, p. 1 Other European governments refused to recognise his passport and expelled him from the country.Hansard, 5 December 1966, vol. 737, col. 1065

Wider role in politics

On 13 September 1968 he was promoted to be the full Minister of Information, Immigration and Tourism. Van der Byl's aristocratic background, military experience and academic credentials combined to give him an almost iconic status within the Rhodesian Front. Many were impressed by his exploits as a big-game hunter, which began when he shot his first lion in a garden in Northern Rhodesia at the age of 15. Writing in South Africa's ''Daily Dispatch

The ''Daily Dispatch'' is a South African newspaper published in East London in the province of Eastern Cape.

The weekend edition is titled ''Daily Dispatch Weekend Edition''.

Founded in 1872 as the ''East London Dispatch and Shipping and Mer ...

'', Michael Hartnack remarked that many in the Rhodesian Front believed him to be "a 19th century-style connoisseur, a man of culture and an aristocrat-statesman", adding that "poseurs are an incipient hazard in any unsophisticated society.""White seal, Black messiah" Michael Hartnack, ''

Daily Dispatch

The ''Daily Dispatch'' is a South African newspaper published in East London in the province of Eastern Cape.

The weekend edition is titled ''Daily Dispatch Weekend Edition''.

Founded in 1872 as the ''East London Dispatch and Shipping and Mer ...

'', Tuesday, 6 November 2001 Within the somewhat claustrophobic confines of white Rhodesian society outside the RF, Van der Byl was achieving some degree of respect.

In politics he assumed the position of hard-line opponent of any form of compromise with domestic opponents or the international community. He made little secret of his willingness to succeed Ian Smith as Prime Minister if Smith showed even "the least whiff of surrender," and did his best to discourage attempts to get the Rhodesians to compromise. When Abel Muzorewa

Abel Tendekayi Muzorewa (14 April 1925 – 8 April 2010), also commonly referred to as Bishop Muzorewa, was a Zimbabwean bishop and politician who served as the first and only Prime Minister of Zimbabwe Rhodesia from the Internal Settlement t ...

had his passport withdrawn in September 1972 after returning from a successful visit to London, the government did not attempt to counter the rumour that its action was taken following Van der Byl's personal order."Bishop Muzorewa has his passport taken away", ''The Times'', Monday, 11 September 1972, p. 5

In April 1972 Van der Byl sparked a row over the agreement which Rhodesia and the United Kingdom had made in November 1971. Under this agreement, Rhodesia had agreed to certain concessions to African nationalism in return for the prospect of recognition of its independence; however, implementation of the agreement was to be delayed until the Pearce Commission The Commission on Rhodesian Opinion, also known as the Pearce Commission, was a British commission set up in 1971 to test the acceptability of a proposed constitutional settlement in Rhodesia. It was created by the Foreign and Commonwealth Secretar ...

reported on whether the settlement proposals would be approved by the people of Rhodesia. Van der Byl insisted that Rhodesia would not implement any part of the agreement unless Rhodesia's independence was first acknowledged, regardless of the answer from the Pearce Commission. When the Pearce Commission reported that the European

European, or Europeans, may refer to:

In general

* ''European'', an adjective referring to something of, from, or related to Europe

** Ethnic groups in Europe

** Demographics of Europe

** European cuisine, the cuisines of Europe and other West ...

, Asian and Coloured

Coloureds () are multiracial people in South Africa, Namibia and, to a smaller extent, Zimbabwe and Zambia. Their ancestry descends from the interracial mixing that occurred between Europeans, Africans and Asians. Interracial mixing in South ...

(mixed race) populations of Rhodesia were in support but the African population were opposed, the agreement was ditched. Many outside and inside Rhodesia had hoped that the government would implement some of the agreement even if Pearce reported against it."Tougher Rhodesian line on settlement proposals", ''The Times'', Monday, 10 April 1972, p. 5

His derision of working class British Labour politicians also caused problems. When, in January 1966, three visiting Labour MPs were manhandled, kicked and punched while attempting to address 400 supporters of the Rhodesian Front, Van der Byl blamed the three for refusing an offer from his Ministry to co-ordinate the visit, and pointed out that they were breaking the law which required government permission for any political meeting of more than 12 people."British M.P.s manhandled by Mr. Smith's supporters", ''The Times'', Thursday, 13 January 1966, p. 10. See alsBBC News online 'On this day'

The propaganda circulated by his Ministry (typically including references to "happy, smiling natives") was considered laughable. Visiting British journalist

Peregrine Worsthorne

Sir Peregrine Gerard Worsthorne (22 December 1923 – 4 October 2020) was a British journalist, writer, and broadcaster. He spent the largest part of his career at the ''Telegraph'' newspaper titles, eventually becoming editor of ''The Sunday ...

, who knew Van der Byl socially, reported seeing a copy of ''Mein Kampf

(; ) is a 1925 Autobiography, autobiographical manifesto by Nazi Party leader Adolf Hitler. The book outlines many of Political views of Adolf Hitler, Hitler's political beliefs, his political ideology and future plans for Nazi Germany, Ge ...

'' on his coffee table.Interview for Centre for Contemporary British History witness seminars. ("I remember being shocked to find open on the coffee table in PK's house, who was then Minister of Information (I am not sure even if he had such a grand title, he ultimately of course became Foreign Minister, war minister to all intents and purposes) a recently perused copy of Mein Kampf. This bears out your comment about the fascist element, which cannot be overlooked. I was fond of PK, but he was a racial supremacist admirer of Hitler.")/ref> His propaganda strategy became increasingly unsuccessful abroad, where Van der Byl alienated many of the foreign journalists and politicians that he came into contact with.

Max Hastings

Sir Max Hugh Macdonald Hastings (; born 28 December 1945) is a British journalist and military historian, who has worked as a foreign correspondent for the BBC, editor-in-chief of ''The Daily Telegraph'', and editor of the ''Evening Standard''. ...

, then reporting for the ''Evening Standard

The ''London Standard'', formerly the ''Evening Standard'' (1904–2024) and originally ''The Standard'' (1827–1904), is a long-established regional newspaper published weekly and distributed free newspaper, free of charge in London, Engl ...

'', described him as "that grotesque parody of a Dornford Yates

Cecil William Mercer (7 August 1885 – 5 March 1960), known by his pen name Dornford Yates, was an English writer and novelist whose novels and short stories, some humorous (the ''Berry'' books), some Thriller (genre), thrillers (the ''Chandos ...

English gentleman" and said that he and Smith "would have seemed ludicrous figures, had they not possessed the power of life and death over millions of people"; Van der Byl had him deported.''Going to the Wars''Max Hastings, Macmillan, 2000, pages 185-189 While still popular with the Rhodesian Front members, he was criticised at the 1972 Party Congress for his lack of success in improving Rhodesia's image around the world; however, he retained the confidence of Ian Smith and was kept on in a government reshuffle on 24 May 1973. That winter saw him promote a new Broadcasting Bill to transfer control of the monopoly

Rhodesian Broadcasting Corporation

The Zimbabwe Broadcasting Corporation (ZBC) is the state-owned broadcaster in Zimbabwe. It was established as the Rhodesian Broadcasting Corporation (RBC), taking its current name in 1980. Like the RBC before it, the ZBC has been accused of bein ...

. Allan Savory

Clifford Allan Redin Savory (born 15 September 1935) is a Zimbabwean livestock farmer and former Rhodesian politician. He is the president and co-founder of the Savory Institute. He originated Holistic management (agriculture), holistic managem ...

, then the lone white opposition MP, criticised the Bill for the composition of the proposed board, which was dominated by strong supporters of the Rhodesian Front. Van der Byl insisted, somewhat unsuccessfully to foreign observers, that the government was not trying to take over broadcasting."Sect members accused of evading conscription", ''The Times'', Thursday, 6 December 1973, p. 7

Minister of Defence

Van der Byl was appointed Minister of Foreign Affairs and Defence on 2 August 1974. These were two distinct portfolios, the first of which (Foreign Affairs) did not amount to much in a state which lacked any form of international recognition. The Defence portfolio, at a time when Rhodesia was drifting into civil war, was an important post; although his previous political experience had been largely in the area of public relations, he was now charged with responsibilities which were central to the survival of Rhodesia. He promoted aggressive measures against the insurgents, and in so doing, he also sought to raise his own political profile. Clad in immaculately tailored battledress, he would fly by helicopter to a beleaguered army outpost; wearing dark glasses and sporting a swagger stick, deliver a rousing speech for the benefit of the troops and the TV cameras – then return to Salisbury in time for dinner. He drew heavily onWinston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

's oratory style for some of his inspiring speeches. As Minister of Defence, Van der Byl was known to join army counter-insurgency operations while armed with a hunting rifle (with the words "I'd like to bag one of these chaps ..."), and would regularly visit army positions and entertain the troops with his own generous supply of "scotch whisky and fine wines." Such behaviour endeared him to many in Rhodesia: he was far more popular with the troops than his predecessor as Minister of Defence, Jack Howman. However, this popularity did not extend to senior members of the South African and Rhodesian governments.

Rhodesia's strategic position underwent a fundamental change in June 1975 when the Portuguese government suddenly withdrew from Mozambique

Mozambique, officially the Republic of Mozambique, is a country located in Southeast Africa bordered by the Indian Ocean to the east, Tanzania to the north, Malawi and Zambia to the northwest, Zimbabwe to the west, and Eswatini and South Afr ...

which bordered Rhodesia on the east. Mozambique now came under the control of a Soviet-allied government which was supportive of black nationalist forces in both South Africa and Rhodesia. This created a delicate situation since Rhodesia's main road and rail links to the outside world were via the Mozambican ports of Beira and Maputo. Initially, the new Mozambican government allowed the Rhodesians continued use of these links. This was so even while ZANU guerrillas were allowed to base themselves in Tete province adjoining north eastern Rhodesia.

There were rumours in February 1976 that Soviet tanks were being unloaded in Mozambique to help in the war. Unluckily for Van der Byl, the British Foreign Office minister was David Ennals

David Hedley Ennals, Baron Ennals, (19 August 1922 – 17 June 1995) was a British Labour Party politician and campaigner for human rights. He served as Secretary of State for Social Services from 1976 to 1979.

Early life and military career

B ...

, one of those who had received rough treatment in 1966. Ennals announced that in the event of a racial war breaking out in Rhodesia, there would be no British help. Van der Byl responded by claiming this indicated Britain accepting Rhodesia's independence."Rhodesia says any Soviet interference would be 'naked aggression'", ''The Times'', Tuesday, 17 February 1976, p. 6 He attacked Abel Muzorewa for supporting President Machel, saying that "being a good churchman and a Bishop there is a very strong possibility he might be a communist".Nicholas Ashford, "Rhodesia admits 1,000 guerillas are operating inside border", ''The Times'', Saturday, 6 March 1976, p. 4

Following the example of Mozambique, the Zambian and Botswana governments permitted guerrillas to establish bases from which they could threaten and infiltrate Rhodesia. Van der Byl told a newspaper reporter that this had to be expected.Michael Knipe, "Rebels open third front against Rhodesia", ''The Times'', Friday, 11 June 1976, p. 7 As infiltration grew, he declared at the beginning of July that the Rhodesian Army would not hesitate to bomb and destroy villages that harboured guerillas.Michael Knipe, "Smith Cabinet rejects plan to open white farm areas to blacks", ''The Times'', Saturday, 3 July 1976. Page 5

In 1975 and 1976, the South African government conducted delicate negotiations with neighbouring states: the South Africans wanted to encourage those states to maintain economic relations with South Africa and Rhodesia while limiting the activities of the ANC, ZANU and ZAPU. However, increasingly aggressive actions by the Rhodesian army outside its own borders resulted in the failure of this conciliatory approach.

A cross-border Selous Scouts

The Selous Scouts was a special forces unit of the Rhodesian Army that operated during the Rhodesian Bush War from 1973 until the reconstitution of the country as Zimbabwe in 1980. It was mainly responsible for infiltrating the black majority ...

raid into Mozambique on 9 August 1976 (dubbed " the Nyadzonya Raid") killed over 1,000 people without Rhodesian fatalities, with Van der Byl insisting that the government had irrefutable proof that the raid had targeted a guerrilla training camp. He was unwilling to disclose the nature of the proof, though he invited the UN to conduct its own investigation into the raid.Michael Knipe, "Rhodesians ask UN to investigate camp raid", ''The Times'', Wednesday, 25 August 1976. Page 1 The raid produced a high body count and a major haul of intelligence and captured arms; according to ZANLA's own figures, which were not publicly circulated, most of those present in the camp had been armed guerrillas, though there were some civilians present. In a successful attempt to win global sympathy, ZANU clamoured that Nyadzonya had been full of unarmed refugees, leading most international opinion to condemn the Rhodesian raid as a massacre. Although cross-border raids into Mozambique had been approved by the Rhodesian cabinet, the depth and severity of the August incursion was greater than had been intended. Van der Byl had sanctioned the incursion largely on his own initiative. Although a tactical success, the incursion caused a final break with Zambia and Mozambique. The South African government was greatly displeased that its earlier diplomatic efforts were compromised and made this clear to Ian Smith. Smith appeared to consider this "the final straw" as far as Van der Byl's defence portfolio was concerned.

Foreign affairs

Van der Byl took over at a time when South Africa was putting increasing pressure on the Rhodesians to make an agreement on majority rule. In March 1975, he had to fly urgently to Cape Town to explain why the Rhodesian government had detained Rev.Ndabaningi Sithole

Ndabaningi Sithole (21 July 1920 – 12 December 2000) was a Zimbabwean politician and statesman who was the founder of the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU), a militant, nationalist organisation that opposed the government of Rhodesia, in ...

of the Zimbabwe African National Union

The Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU) was a militant socialist organisation that fought against white-minority rule in Rhodesia, formed as a split from the Zimbabwe African People's Union (ZAPU) in 1963. ZANU split in 1975 into wings l ...

, who was accused of plotting against other black nationalist leaders. The South Africans were extremely displeased with this action and suspected that the real reason was that the Rhodesians objected to Sithole and preferred to negotiate with Joshua Nkomo

Joshua Mqabuko Nyongolo Nkomo (19 June 1917 – 1 July 1999) was a Zimbabwean revolutionary and politician who served as Vice-President of Zimbabwe from 1990 until his death in 1999. He founded and led the Zimbabwe African People's Union (ZAPU) ...

.Michael Knipe, "Sithole arrest linked with death list", ''The Times'', Friday, 7 March 1975, p. 8 Van der Byl was unsuccessful in reassuring the South Africans and Ian Smith was forced to follow him.

Gradually the South Africans grew unwilling to help Rhodesia. The remaining 200 South African policemen transferred to help in the guerilla war were removed suddenly in August 1975, a move which appeared to precede even more disengagement. Van der Byl responded in a speech on 8 August which asserted that "The terrorists who are trained and equipped outside our border and who invade our country with the willing help of other governments are here for a much wider purpose than the overthrow of Rhodesia. They are here to represent a force which sees Rhodesia as just one more stepping stone to victory over South Africa because they see South Africa as a vital key to the security of America, Europe and the rest of the western world.""Relations under strain at Pretoria meeting", ''The Times'', Saturday, 9 August 1975, p. 1

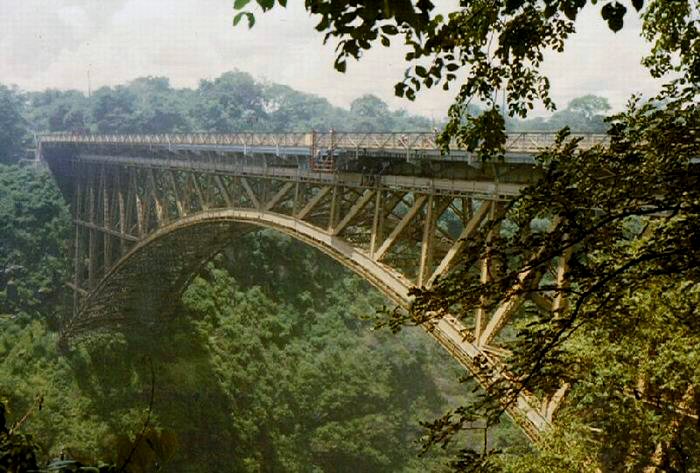

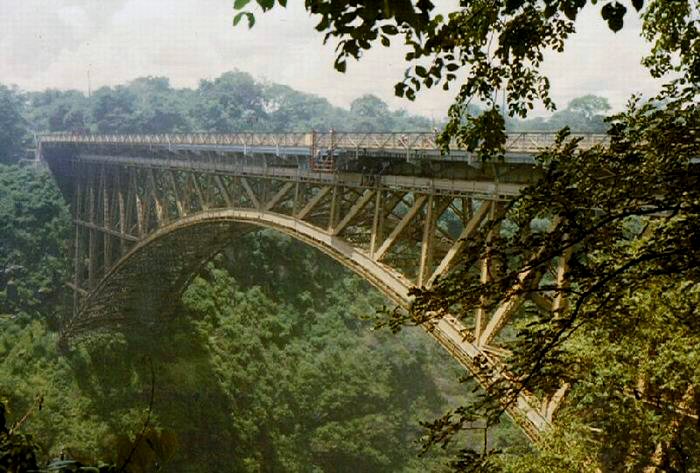

When the Rhodesian government held talks with the African National Council on the railway bridge across the

Gradually the South Africans grew unwilling to help Rhodesia. The remaining 200 South African policemen transferred to help in the guerilla war were removed suddenly in August 1975, a move which appeared to precede even more disengagement. Van der Byl responded in a speech on 8 August which asserted that "The terrorists who are trained and equipped outside our border and who invade our country with the willing help of other governments are here for a much wider purpose than the overthrow of Rhodesia. They are here to represent a force which sees Rhodesia as just one more stepping stone to victory over South Africa because they see South Africa as a vital key to the security of America, Europe and the rest of the western world.""Relations under strain at Pretoria meeting", ''The Times'', Saturday, 9 August 1975, p. 1

When the Rhodesian government held talks with the African National Council on the railway bridge across the Victoria Falls

Victoria Falls (Lozi language, Lozi: ''Mosi-oa-Tunya'', "Thundering Smoke/Smoke that Rises"; Tonga language (Zambia and Zimbabwe), Tonga: ''Shungu Namutitima'', "Boiling Water") is a waterfall on the Zambezi River, located on the border betwe ...

in August 1975 (the train in which the talks took place was strategically in the middle of the bridge so that the ANC were in Zambia while the Rhodesians remained in Rhodesia), Van der Byl was not a member of the Rhodesian delegation. This was a curious omission given his position. He did however participate in talks with Joshua Nkomo that December.

Van der Byl's habit of referring to the African population as "munts" (he asserted that "Rhodesia is able to handle the munts""Chilly reception awaits Rhodesian leader after television remark"''The Times'', Monday, 20 October 1975, p. 4) led to extreme unpopularity with the South African government, and he did not attend talks with South African Prime Minister

John Vorster

Balthazar Johannes "B. J." Vorster (; 13 December 1915 – 10 September 1983), better known as John Vorster, was a South African politician who served as the prime minister of South Africa from 1966 to 1978 and the fourth state president of So ...

in October 1975. This was interpreted as being connected to Vorster's dislike of Van der Byl who, despite being of Afrikaner origin, had adopted English mannerisms.''Private Eye''Issues 393-407; Issues 409-418, 1977, page 4 When, on 26 August 1976, the South African government announced the withdrawal of all its military helicopter crews from Rhodesia, Van der Byl was outspoken in his criticism and Vorster was reported to have refused to have anything to do with "that dreadful man Van der Byl." Smith decided that he "clearly ... had no option" and on 9 September 1976 executed a sudden cabinet reshuffle that ended Van der Byl's tenure as Defence Minister. Smith claimed the South African dislike of Van der Byl was partly motivated by the memory of his father, who had been in opposition to the National Party.

Contribution to diplomacy

As the prominence of the issue of Rhodesia increased in the late 1970s, attention on Van der Byl increased. Reporters noted his impressively quotable lines at press conferences (such as his explanation for why the Rhodesian government did not usually give the names of guerrillas which it had hanged: "Why should we? Anyway, it's academic because they're normally dead after it"). While negotiating with the Patriotic Front put together by ZANU and ZAPU at the Geneva Conference in November 1976, he described ZANU leader Robert Mugabe as "this bloodthirsty Marxist puppet" and the Patriotic Front proposals as "almost a parody, a music hall caricature of communist invective". Mugabe repeatedly arrived late to the meetings held during the conference, and on one occasion Van der Byl tersely reprimanded the ZANU leader for his tardiness. Mugabe flew into a rage and shouted across the table at Van der Byl, calling the Rhodesian minister a "foul-mouthed bloody fool!" At this conference, which was organised by Britain with American support, Van der Byl rejected the idea of an interim British presence in Rhodesia during a transition to majority rule, which was identified as one of the few ways of persuading the Patriotic Front to endorse a settlement."'British presence' idea rebuffed by Mr Smith", ''The Times'', Saturday, 4 December 1976, p. 4 The conference was adjourned by the British foreign minister,Anthony Crosland

Charles Anthony Raven Crosland (29 August 191819 February 1977) was a British Labour Party (UK), Labour Party politician and author. A social democrat on the right wing of the Labour Party, he was a prominent socialist intellectual. His influe ...

, on 14 December 1976, and ultimately never reconvened. The nationalist leaders said they would not return to Geneva or take part in any further talks unless immediate black rule were made the only topic for discussion. Soon after, on 7 January 1977, Van der Byl announced the Rhodesian government's rejection of every proposal made in Geneva."Rhodesia rejects all proposals", ''The Times'', Saturday, 8 January 1977, p. 1

Later that month, Van der Byl was finding pressure put on him by more moderate voices within Rhodesia and hinted that the government might amend the Land Tenure Act, which effectively split the country into sections reserved for each racial group. He also remarked that Bishop Abel Muzorewa "can be said to represent the African in this country",Michael Knipe, "Mr Richard warns Salisbury not to reject peace plan", ''The Times'', Friday, 21 January 1977, p. 6 which indicated the direction in which the Smith government was hoping to travel: an accommodation with moderate voices within Rhodesia was likely to be a better end than a capitulation to the Patriotic Front. Van der Byl was prepared to support this strategy and did not go along with the 12 Rhodesian Front MPs who formed the Rhodesian Action Party in early 1977 claiming that the Front had not adhered to party principles.

Although Van der Byl was now prepared to say that he supported the transition to majority rule, he was quick to put restrictions on it when interviewed in April 1977. He insisted that majority rule would only be possible on a "very qualified franchise—that's what the whole thing is about", and also said that any settlement must be endorsed by a two-thirds majority of the existing House of Assembly (which was largely elected by white Rhodesians).Michael Knipe, "Mr Van der Byl demands guerrillas scale down war before Rhodesia settlement", ''The Times'', Monday, 25 April 1977, p. 5 In mid 1977 he continued to warn that insistence on capitulation to the Patriotic Front would produce a white backlash and put negotiations back."Warning of 'white backlash'", ''The Times'', Wednesday, 29 June 1977, p. 6

However, the Rhodesian government was forced to put its internal settlement negotiations on hold during a joint US-UK initiative in late 1977. Van der Byl's public comments seemed to be aimed at ensuring this mission did not succeed, as he insisted that it had no chance of negotiating a ceasefire, described the Carter

Carter(s), or Carter's, Tha Carter, or The Carter(s), may refer to:

Geography United States

* Carter, Arkansas, an unincorporated community

* Carter, Mississippi, an unincorporated community

* Carter, Montana, a census-designated place

* Carter ...

administration as "mindless", and the joint mission as being "Anglo-American-Russian".Nicholas Ashford, "Rhodesian doubts on Carver mission", ''The Times'', Wednesday, 2 November 1977; p. 8 When a plan was published, he described it as "totally outrageous" and involving "the imposition of unconditional surrender on an undefeated people who are not enemies"."Lord Carver denies he was given 'brush off' by leaders in Africa", ''The Times'', Friday, 11 November 1977, p. 8

Internal settlement

The mission did fail and the internal settlement talks were resurrected, resulting in a deal on 4 March 1978. A transitional joint Council of Ministers was set up, with Van der Byl having to work with Dr Elliott Gabellah as his co-Minister of Foreign Affairs. The Patriotic Front took no notice of this accord and the guerrilla war continued;Lord Richard Cecil

Lord Richard Valentine Gascoyne-Cecil (26 January 1948 – 20 April 1978) was a British soldier, Conservative politician and freelance journalist who was killed in Rhodesia whilst covering the country's Bush War. The second son of the 6th Ma ...

, a close family friend working as a photo-journalist, was killed by guerrillas on 20 April 1978 after Van der Byl had ensured he had full access to military areas denied to other reporters."Lord Richard Cecil" (obituary), ''The Times'', Saturday, 22 April 1978, p. 16

In May Van der Byl greeted news of massacres in Zaire

Zaire, officially the Republic of Zaire, was the name of the Democratic Republic of the Congo from 1971 to 18 May 1997. Located in Central Africa, it was, by area, the third-largest country in Africa after Sudan and Algeria, and the 11th-la ...

as "a blessing in disguise" because they might ensure that warnings about Soviet penetration in Africa were heeded."Kolwezi 'a blessing in disguise'", ''The Times'', Monday, 29 May 1978, p. 5 He denounced the British government the following month for refusing to recognise that a massacre of Elim missionaries was perpetrated by the Patriotic Front.Frederick Cleary, "Call from Salisbury for Owen explanation", ''The Times'', Wednesday, 28 June 1978, p. 8 As the date for the full implementation of the internal settlement grew nearer, Van der Byl's profile decreased, but he remained active in politics: he was elected unopposed for the whites-only Gatooma/Hartley seat to the Zimbabwe-Rhodesia House of Assembly. He handed over power to his African successor on 1 June 1979, and became instead Minister of Transport and Power and Minister of Posts in the new government.

Lancaster House

When "the wheels came off the wagon" (as he put it) atLancaster House

Lancaster House (originally known as York House and then Stafford House) is a mansion on The Mall, London, The Mall in the St James's district in the West End of London. Adjacent to The Green Park, it is next to Clarence House and St James ...

in 1979, Van der Byl greeted the event with amused detachment. He was not a member of any delegation at the conference and did not attend. The weekend after the agreement, he called on the Rhodesian Front to revitalise itself as the only true representative of Europeans in Rhodesia,Nicholas Ashford, "Future looks doubtful for Smith party", ''The Times'', Saturday, 17 November 1979, p. 5 and he ascribed the result of the conference to "a succession of perfidious British governments".David Spanier, "Ceasefire accord sought this week", ''The Times'', Monday, 19 November 1979, p. 5

According to Ian Smith's memoirs, Van der Byl organised a meeting between Ian Smith and Lieutenant-General Peter Walls

Lieutenant General George Peter Walls (1927-201Walls: "We will make it work" Time magazine and CNN20 July 2010) was a Rhodesian soldier. He served as the Head of the Armed Forces of Rhodesia during the Rhodesian Bush War from 1977 until his ...

, Commander of the Rhodesian Army, shortly before the first Zimbabwean elections in February 1980, where they agreed a strategy to prevent Robert Mugabe winning. They met again on 26 February the day before polling began in the Common Roll election. The consensus at this meeting was that Abel Muzorewa's interim government would win enough seats, when put together with the 20 seats reserved for whites which were all Rhodesian Front, to deny Mugabe victory. However, the early election results in March dented this confidence.

Smith asked Walls for details of his plan ("Operation Quartz")Operation Quartz – Rhodesia 1980/ref> for resisting ZANU-PF taking power by force if it lost the election. Walls insisted that ZANU-PF would not win the election, and that ZANU's illegal and massive intimidation of voters showed it would continue this behavior if it lost. When ZANU won, both Smith and Van der Byl believed ZANU's atrocities had invalidated its victory, and that the Army should step in to prevent Mugabe taking over. Walls took the view that it was already too late, and while the others wished for some move, they were forced to concede to this view.

In Zimbabwe

Van der Byl had been elected unopposed to the newHouse of Assembly

House of Assembly is a name given to the legislature or lower house of a bicameral parliament. In some countries this may be at a subnational level.

Historically, in British Crown colonies as the colony gained more internal responsible g ...

for Gatooma/Hartley

Hartley may refer to:

Places Australia

*Hartley, New South Wales

* Hartley, South Australia

** Electoral district of Hartley, a state electoral district

Canada

* Hartley Bay, British Columbia

United Kingdom

* Hartley, Cumbria

* Hartley, P ...

and remained a close associate of Smith, becoming vice-president of the 'Republican Front' (later renamed the Conservative Alliance of Zimbabwe

The Conservative Alliance of Zimbabwe (CAZ) was the final incarnation of a party formerly called the Republican Front, and prior to that it was called the Rhodesian Front (RF). In the immediate post-independence period, the party sought to pro ...

). At the 1985 general election the boundaries for the White Roll seats were altered and Van der Byl fought in Mount Pleasant, opposing Chris Andersen.Jan Raath, "Time stands still for Smith as whites face up to reality", ''The Times'', Thursday, 27 June 1985, p. 5 Andersen had broken with the Rhodesian Front to sit as an Independent and became Minister of State for the Public Service in Robert Mugabe's government. Van der Byl lost the election heavily,Jan Raath, "Smith wins battle in Bulawayo", ''The Times'', Friday, 28 June 1985, p. 5 polling only 544 votes to 1,017 for Andersen and 466 for a third candidate. The Conservative Alliance of Zimbabwe still controlled the election of ten white Senators and Smith agreed to elect Van der Byl to one of the Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

seats.

Parliamentary seats reserved for whites were abolished in 1987. Van der Byl made his last speech in Parliament on 10 September, in which he praised Robert Mugabe for the "absolute courtesy" he had shown since independence. He noted that he was the last surviving member of the 1965 government remaining in Parliament, and declared he hoped "I would have been cherished .. as a sort of national monument, and not flung into the political wilderness". His speech loudly denounced the former Republican Front and Conservative Alliance of Zimbabwe members who had gone over to the government, describing them as "dreadful souls screaming in agony". The government minister Dr Edson Zvobgo

Eddison Jonasi Mudadirwa Zvobgo (2 October 1935 – 22 August 2004) was a revolutionary Zimbabwean politician and the founder of Zimbabwe's ruling party, ZANU–PF. He was the ZANU-PF's spokesman at the Lancaster House in late 1979,

responded with a poem referring to the number of rebels killed fighting troops under Van der Byl's command.Jan Raath, "Zimbabwe prize-fighters don kid gloves", ''The Times'', Saturday, 12 September 1987, p. 7

Marriage, issue and retirement

On 31 August 1979 at Schloss Waldstein inDeutschfeistritz

Deutschfeistritz () is a municipality in the district of Graz-Umgebung in the Austrian state of Styria. It is the site of , one of the homes of the Princes of Liechtenstein

There have been 16 monarchs of the Principality of Liechtenstein since 16 ...

, Austria, Van der Byl married Princess Charlotte Maria Benedikte Eleonore Adelheid of Liechtenstein. She was thirty years his junior, the daughter of Prince Heinrich of Liechtenstein and granddaughter of Karl I

Charles I (, ; 17 August 1887 – 1 April 1922) was Emperor of Austria, King of Hungary (as Charles IV), and the ruler of the other states of the Habsburg monarchy from November 1916 until the monarchy was abolished in November 1918. He was the ...

, the last emperor of Austria. The couple had three sons: Pieter Vincenz, Valerian, and Casimir.

In 1983 Van der Byl had inherited from his mother a property described as "the magnificent estate .. near Caledon in the Western Cape," and following the end of his political career had no need to keep a home in Zimbabwe, so he quit the place. He left as a rich man, with an attractive young wife, and enjoyed his retirement. He frequently visited London, where he was a good friend of Viscount Cranborne

A viscount ( , for male) or viscountess (, for female) is a title used in certain European countries for a noble of varying status. The status and any domain held by a viscount is a viscounty.

In the case of French viscounts, the title is so ...

, who put him up for membership of the Turf Club.Paul Vallely and John Rentoul, "A Lordly plot to save their place", ''The Independent

''The Independent'' is a British online newspaper. It was established in 1986 as a national morning printed paper. Nicknamed the ''Indy'', it began as a broadsheet and changed to tabloid format in 2003. The last printed edition was publis ...

'', 4 December 1996, p. 16 Both were members of White's Club

White's is a gentlemen's club in St James's, London. Founded in 1693 as a hot chocolate shop in Mayfair, it is London's oldest club and therefore the oldest private members' club in the world. It moved to its current premises on St James's St ...

and were often seen there when Van der Byl was in town.

Four days after his 76th birthday, Van der Byl died at Fairfield, in Caledon, Western Cape

Caledon, originally named ''Swartberg'', is a town in the Overberg region in the Western Cape province of South Africa, located about east of Cape Town next to mineral-rich hot springs. it had a population of 13,020. It is located in, and the se ...

. In his obituary, Dan van der Vat

Daniel Francis Jeroen van der Vat (28 October 1939 – 9 May 2019) was a journalist, writer and military historian, with a focus on naval history.

Born in Alkmaar, North Holland, Van der Vat grew up in the German- occupied Netherlands. He attended ...

wrote "The arrival of majority rule in South Africa made no difference, and he died a very wealthy man."

Awards

* *References

Notes References Bibliography * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Byl, P. K. van der 20th-century Zimbabwean politicians 1923 births 1999 deaths Afrikaner people Alumni of Diocesan College, Cape Town Alumni of Pembroke College, Cambridge Businesspeople in the tobacco industry Foreign ministers of Rhodesia Harvard Business School alumni Members of the National Assembly of Zimbabwe Members of the Parliament of Rhodesia Politicians from Cape Town Rhodesian anti-communists Rhodesian businesspeople Rhodesian farmers Rhodesian Front politicians South African anti-communists South African emigrants to Rhodesia South African military personnel of World War II South African people of Scottish descent South African white supremacists White Rhodesian people 20th-century Zimbabwean businesspeople White Zimbabwean politicians Zimbabwean exiles Zimbabwean farmers South African expatriates in the United Kingdom South African expatriates in the United States Defence ministers of Rhodesia