Orange Riots on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Orange Riots took place in

The Orange Riots took place in

The crowd began to pelt the paraders with stones, bricks, bottles, and shoes. Militiamen responded with musket fire, which brought pistol fire from some in the crowd. The police managed to get the parade moving again by charging the crowd and liberally using their clubs. The parade progressed another block but came under fire from thrown missiles again, once again provoking militia shots.

The crush of the crowds prevented more forward motion, and police used their clubs and the militia used their bayonets. Rocks and crockery pelted down on them from the rooftops along the avenue. Troops started firing volleys into the crowd, without being ordered to do so, and the police followed up with mounted charges.

The parade managed to get to 23rd Street, where it turned left and proceeded to

The crowd began to pelt the paraders with stones, bricks, bottles, and shoes. Militiamen responded with musket fire, which brought pistol fire from some in the crowd. The police managed to get the parade moving again by charging the crowd and liberally using their clubs. The parade progressed another block but came under fire from thrown missiles again, once again provoking militia shots.

The crush of the crowds prevented more forward motion, and police used their clubs and the militia used their bayonets. Rocks and crockery pelted down on them from the rooftops along the avenue. Troops started firing volleys into the crowd, without being ordered to do so, and the police followed up with mounted charges.

The parade managed to get to 23rd Street, where it turned left and proceeded to

The Orange Riots took place in

The Orange Riots took place in Manhattan

Manhattan ( ) is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the Boroughs of New York City, five boroughs of New York City. Coextensive with New York County, Manhattan is the County statistics of the United States#Smallest, larg ...

, New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

, in 1870 and 1871, and they involved violent conflict between Irish Protestants who were members of the Orange Order

The Loyal Orange Institution, commonly known as the Orange Order, is an international Protestant fraternal order based in Northern Ireland and primarily associated with Ulster Protestants. It also has lodges in England, Grand Orange Lodge of ...

and hence called "Orangemen", and Irish Catholics

Irish Catholics () are an ethnoreligious group native to Ireland, defined by their adherence to Catholic Christianity and their shared Irish ethnic, linguistic, and cultural heritage.The term distinguishes Catholics of Irish descent, particul ...

, along with the New York City Police Department

The City of New York Police Department, also referred to as New York City Police Department (NYPD), is the primary law enforcement agency within New York City. Established on May 23, 1845, the NYPD is the largest, and one of the oldest, munic ...

and the New York State National Guard. The riot caused the deaths of over 60 civilians – mostly Irish laborers – and three guardsmen.

Background

On July 12, 1870, a parade was held in Manhattan byIrish Protestant

Protestantism is a Christianity, Christian community on the island of Ireland. In the 2011 census of Northern Ireland, 48% (883,768) described themselves as Protestant, which was a decline of approximately 5% from the 2001 census. In the 2011 ...

s celebrating the victory at the Battle of the Boyne

The Battle of the Boyne ( ) took place in 1690 between the forces of the deposed King James II, and those of King William III who, with his wife Queen Mary II (his cousin and James's daughter), had acceded to the Crowns of England and Sc ...

(1689) of King William III (also Prince of Orange), over the former King James II of England

James II and VII (14 October 1633 – 16 September 1701) was King of England and Monarchy of Ireland, Ireland as James II and King of Scotland as James VII from the death of his elder brother, Charles II of England, Charles II, on 6 February 1 ...

(a Catholic, who had been deposed by William III).

The parade route was up Eighth Avenue to Elm Park at 92nd Street. The Orangemen marching through the Irish-Catholic neighborhood of Hell's Kitchen

Hell's Kitchen, also known as Clinton, or Midtown West on real estate listings, is a neighborhood on the West Side of Midtown Manhattan in New York City, New York. It is considered to be bordered by 34th Street (or 41st Street) to the south, ...

were viewed by the Irish-Catholic residents as a recurring reminder of past and current class oppression. Many of the Irish-Catholic protesters followed the parade and according to statements later made by police, the violence that would follow was premeditated. At the park, the crowd of 200 Irish-Catholic protesters was joined by a group of 300 Irish-Catholic laborers working in the neighborhood, and the parade erupted into violence. Although the police intervened to quell the fighting, 8 people died as a result of the riot.Burrows & Wallace, pp.1003-1008Gilmore, p.866

The following year, the Loyal Order of Orange requested police permission to march again. Fearing another violent incident, the parade was banned by City Police Commissioner James J. Kelso, with the support of William M. Tweed, the head of Tammany Hall

Tammany Hall, also known as the Society of St. Tammany, the Sons of St. Tammany, or the Columbian Order, was an American political organization founded in 1786 and incorporated on May 12, 1789, as the Tammany Society. It became the main local ...

, the Democratic Party political machine

In the politics of representative democracies, a political machine is a party organization that recruits its members by the use of tangible incentives (such as money or political jobs) and that is characterized by a high degree of leadership c ...

which controlled the city and the state. Catholic Archbishop John McCloskey

John McCloskey (March 10, 1810 – October 10, 1885) was an Catholic Church in the United States, American Catholic prelate who served as the first American-born Roman Catholic Archdiocese of New York, Archbishop of New York from 1864 until his ...

applauded the decision.

Protestants objected, as did newspaper editorials in the ''Herald

A herald, or a herald of arms, is an officer of arms, ranking between pursuivant and king of arms. The title is commonly applied more broadly to all officers of arms.

Heralds were originally messengers sent by monarchs or noblemen ...

'' and '' Times'', a petition signed by Wall Street

Wall Street is a street in the Financial District, Manhattan, Financial District of Lower Manhattan in New York City. It runs eight city blocks between Broadway (Manhattan), Broadway in the west and South Street (Manhattan), South Str ...

businessmen, and a cartoon by Thomas Nast

Thomas Nast (; ; September 26, 1840December 7, 1902) was a German-born American caricaturist and editorial cartoonist often considered to be the "Father of the American Cartoon".

He was a sharp critic of William M. Tweed, "Boss" Tweed and the T ...

in ''Harper's

''Harper's Magazine'' is a monthly magazine of literature, politics, culture, finance, and the arts. Launched in New York City in June 1850, it is the oldest continuously published monthly magazine in the United States. ''Harper's Magazine'' has ...

''. Not only was the ban felt to be giving in to the bad behavior of a Catholic mob, but fears were voiced about the growing political power of Irish Catholics, the increasing visibility of Irish nationalism

Irish nationalism is a nationalist political movement which, in its broadest sense, asserts that the people of Ireland should govern Ireland as a sovereign state. Since the mid-19th century, Irish nationalism has largely taken the form of cult ...

in the city, and the possibility of a radical political action such as occurred in Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

with the Commune.

The pressure generated by these concerns among the city's elite, on top of pressure from good-government reformers against Tweed's regime in general, caused Tammany

Tamanend ("the Affable"; ), historically also known as Taminent, Tammany, Saint Tammany or King Tammany, was the Chief of Chiefs and Chief of the Turtle Clan of the Lenape, Lenni-Lenape nation in the Delaware Valley signing the founding peace t ...

to reverse course and allow the march; Tammany needed to show that it could control the immigrant Irish population which formed a major part of its electoral power. Governor John T. Hoffman, a Tammany man, rescinded the police commissioner's ban and ordered that the paraders be protected by the city police and the state militia, including cavalry

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from ''cheval'' meaning "horse") are groups of soldiers or warriors who Horses in warfare, fight mounted on horseback. Until the 20th century, cavalry were the most mob ...

.

1871 riot

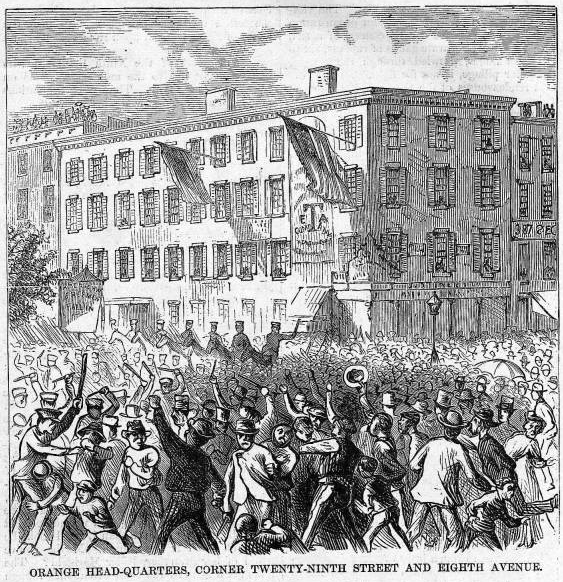

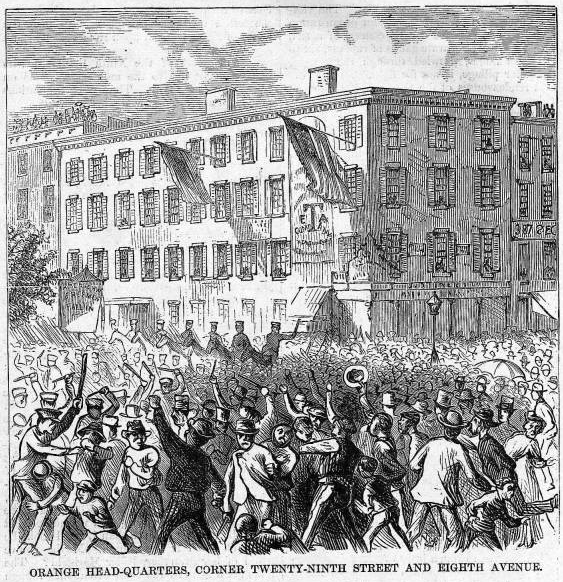

On July 12, 1871, the parade proceeded with protection from 1,500 policemen and 5 regiments of the National Guard, about 5,000 men. It was to begin at the Orangemen's headquarters at Lamartine Hall, located at Eighth Avenue and 29th Street. By 1:30 pm, the streets from 21st to 33rd were full of people, mostly Catholic, and mostly laborers, and both sides of the avenue were jammed. The police and militia arrived, to the disapproval of the crowd. The small contingent of Orangemen began their parade down the avenue at 2:00 pm, surrounded by regimental units. The crowd began to pelt the paraders with stones, bricks, bottles, and shoes. Militiamen responded with musket fire, which brought pistol fire from some in the crowd. The police managed to get the parade moving again by charging the crowd and liberally using their clubs. The parade progressed another block but came under fire from thrown missiles again, once again provoking militia shots.

The crush of the crowds prevented more forward motion, and police used their clubs and the militia used their bayonets. Rocks and crockery pelted down on them from the rooftops along the avenue. Troops started firing volleys into the crowd, without being ordered to do so, and the police followed up with mounted charges.

The parade managed to get to 23rd Street, where it turned left and proceeded to

The crowd began to pelt the paraders with stones, bricks, bottles, and shoes. Militiamen responded with musket fire, which brought pistol fire from some in the crowd. The police managed to get the parade moving again by charging the crowd and liberally using their clubs. The parade progressed another block but came under fire from thrown missiles again, once again provoking militia shots.

The crush of the crowds prevented more forward motion, and police used their clubs and the militia used their bayonets. Rocks and crockery pelted down on them from the rooftops along the avenue. Troops started firing volleys into the crowd, without being ordered to do so, and the police followed up with mounted charges.

The parade managed to get to 23rd Street, where it turned left and proceeded to Fifth Avenue

Fifth Avenue is a major thoroughfare in the borough (New York City), borough of Manhattan in New York City. The avenue runs south from 143rd Street (Manhattan), West 143rd Street in Harlem to Washington Square Park in Greenwich Village. The se ...

, where the crowds were supportive of the Orangemen. This changed again when the parade continued south down Fifth and reached the entertainment district below 14th Street, where the crowds were once again hostile. The parade then continued across town to Cooper Union

The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art, commonly known as Cooper Union, is a private college on Cooper Square in Lower Manhattan, New York City. Peter Cooper founded the institution in 1859 after learning about the government-s ...

, where the paraders dispersed.

The riot caused the deaths of over 60 civilians – mostly Ulster Scots Protestant and Irish Catholic laborers – and three Guardsmen. Over 150 people were wounded, including 22 militiamen, around 20 policemen injured by thrown missiles, and 4 who were shot, but not fatally. Eighth Avenue was devastated, with one reporter from the New York Herald

The ''New York Herald'' was a large-distribution newspaper based in New York City that existed between 1835 and 1924. At that point it was acquired by its smaller rival the '' New-York Tribune'' to form the '' New York Herald Tribune''.

Hi ...

describing the street as "smeared and slippery with human blood and brains while the land beneath was covered two inches deep with clotted gore, pieces of brain, and the half digested contents of a human stomach and intestines." About 100 people were arrested.

The following day, on July 13, 20,000 mourners paid their respects to the dead outside the morgue at Bellevue Hospital, and funeral processions made their way to Calvary Cemetery in Queens

Queens is the largest by area of the Boroughs of New York City, five boroughs of New York City, coextensive with Queens County, in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York. Located near the western end of Long Island, it is bordered by the ...

by way of ferries. Governor Hoffman was hanged in effigy

An effigy is a sculptural representation, often life-size, of a specific person or a prototypical figure. The term is mostly used for the makeshift dummies used for symbolic punishment in political protests and for the figures burned in certain ...

by Irish Catholics in Brooklyn, and the events began to be referred to as the "Slaughter on Eighth Avenue."

Effects

Despite their attempt to protect their political power by allowing the parade to go forward, Tammany Hall did not benefit from the outcome, instead coming under increased criticism from newspapers and the city's elite. Tweed fell from power shortly afterwards.One of the reasons many in the upper and middle classes had grudingly acquiesced in Tammany's hold on power was its presumed ability to maintain political stability. That saving grace was gone: Tweed could not keep the Irish in line. The time had come, said Congregationalist minister Merrill Richardson from the pulpit of his fashionable Madison Avenue church, to take back New York City, for if "the higher classes will ''not'' govern, the lower classes ''will''."Burrows & Wallace, p.1008Banker Henry Smith told the ''

New York Tribune

The ''New-York Tribune'' (from 1914: ''New York Tribune'') was an American newspaper founded in 1841 by editor Horace Greeley. It bore the moniker ''New-York Daily Tribune'' from 1842 to 1866 before returning to its original name. From the 1840s ...

'' that "such a lesson was needed every few years. Had one thousand of the rioters been killed, it would have had the effect of completely cowing the remainder."

See also

* Drumcree conflict * List of incidents of civil unrest in New York City *List of incidents of civil unrest in the United States

Listed are major episodes of civil unrest in the United States. This list does not include the numerous incidents of destruction and violence associated with various sporting events.

18th century

*1783 – Pennsylvania Mutiny of 1783, June ...

* New York City draft riots

Notes

Further reading

*Gilmore, Russell S. "Orange riots" in * * Gordon, Michael A. ''The Orange Riots: Irish Political Violence in New York City, 1870 and 1871'' (Cornell UP, 2018) * White, Richard (2017). ''The Republic for Which It Stands: The United States during Reconstruction and the Gilded Age, 1865–1896.'' Stanford:Stanford University Press

Stanford University Press (SUP) is the publishing house of Stanford University. It is one of the oldest academic presses in the United States and the first university press to be established on the West Coast. It is currently a member of the Ass ...

. ISBN 0199735816

External links

* {{Riots in the United States (1865–1918) 1870 crimes in the United States 1871 crimes in the United States 1870 riots 1871 riots 1870 in New York City 1871 in New York City July 1870 July 1871 19th century in Manhattan Riots and civil disorder in New York City Orange Order Tammany Hall William M. Tweed