obscurantist on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In

In

In restricting education and knowledge to a ruling class, obscurantism is anti-democratic in its components of

In restricting education and knowledge to a ruling class, obscurantism is anti-democratic in its components of

"Selective Intelligence"

''The New Yorker'', 12 May 2003, accessed 29 April 2016. Brian Doherty

"Origin of the Specious: Why Do Neoconservatives Doubt Darwin?"

, ''Reason Online'' July 1997, accessed 16 February 2007. In 18th century monarchic France, the political scientist

In the essay "Why I Am Not a Conservative" (1960), the economist

In the essay "Why I Am Not a Conservative" (1960), the economist

Aristotle divided his own works into two classifications: " exoteric" and "

Aristotle divided his own works into two classifications: " exoteric" and "

In his early works, Karl Marx criticized German and French philosophy, especially

In his early works, Karl Marx criticized German and French philosophy, especially

Obscurantism in religion – Islamic Research Foundation International

{{Authority control Obfuscation Anti-intellectualism Knowledge Philosophical theories Propaganda techniques

In

In philosophy

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

, obscurantism or obscurationism is the anti-intellectual practice of deliberately presenting information in an abstruse

In philosophy, obscurantism or obscurationism is the Anti-intellectualism, anti-intellectual practice of deliberately presenting information in an wikt:abstruse, abstruse and imprecise manner that limits further inquiry and understanding of a subj ...

and imprecise manner that limits further inquiry and understanding of a subject. ''Obscurantism'' has been defined as opposition to the dissemination of knowledge and as writing characterized by deliberate vagueness.

In the 18th century, Enlightenment philosophers applied the term ''obscurantist'' to any enemy of intellectual enlightenment and the liberal diffusion of knowledge. In the 19th century, in distinguishing the varieties of obscurantism found in metaphysics

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that examines the basic structure of reality. It is traditionally seen as the study of mind-independent features of the world, but some theorists view it as an inquiry into the conceptual framework of ...

and theology

Theology is the study of religious belief from a Religion, religious perspective, with a focus on the nature of divinity. It is taught as an Discipline (academia), academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itse ...

, from the "more subtle" obscurantism of the critical philosophy

Critical philosophy () is a movement inaugurated by Immanuel Kant (1724–1804). It is dedicated to the self-examination of reason with the aim of exposing its inherent limitations, that is, to defining the possibilities of knowledge as a prere ...

of Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant (born Emanuel Kant; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German Philosophy, philosopher and one of the central Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works ...

and of modern philosophical skepticism

Philosophical skepticism (UK spelling: scepticism; from Ancient Greek, Greek σκέψις ''skepsis'', "inquiry") is a family of philosophical views that question the possibility of knowledge. It differs from other forms of skepticism in that ...

, Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher. He began his career as a classical philology, classical philologist, turning to philosophy early in his academic career. In 1869, aged 24, Nietzsche bec ...

said that: "The essential element in the black art of obscurantism is not that it wants to darken individual understanding, but that it wants to blacken our picture of the world, and darken our idea of existence."

Restricting knowledge

In restricting education and knowledge to a ruling class, obscurantism is anti-democratic in its components of

In restricting education and knowledge to a ruling class, obscurantism is anti-democratic in its components of anti-intellectualism

Anti-intellectualism is hostility to and mistrust of intellect, intellectuals, and intellectualism, commonly expressed as deprecation of education and philosophy and the dismissal of art, literature, history, and science as impractical, politica ...

and social elitism

Elitism is the notion that individuals who form an elite — a select group with desirable qualities such as intellect, wealth, power, physical attractiveness, notability, special skills, experience, lineage — are more likely to be construc ...

, which exclude the majority of the people, deemed unworthy of knowing the facts about their government and the political and economic affairs of their city-state

A city-state is an independent sovereign city which serves as the center of political, economic, and cultural life over its contiguous territory. They have existed in many parts of the world throughout history, including cities such as Rome, ...

.Hersh, Seymour"Selective Intelligence"

''The New Yorker'', 12 May 2003, accessed 29 April 2016. Brian Doherty

"Origin of the Specious: Why Do Neoconservatives Doubt Darwin?"

, ''Reason Online'' July 1997, accessed 16 February 2007. In 18th century monarchic France, the political scientist

Marquis de Condorcet

Marie Jean Antoine Nicolas de Caritat, Marquis of Condorcet (; ; 17 September 1743 – 29 March 1794), known as Nicolas de Condorcet, was a French Philosophy, philosopher, Political economy, political economist, Politics, politician, and m ...

documented the obscurantism of the aristocracy

Aristocracy (; ) is a form of government that places power in the hands of a small, privileged ruling class, the aristocracy (class), aristocrats.

Across Europe, the aristocracy exercised immense Economy, economic, Politics, political, and soc ...

and their indifference to the social problems that provoked the French Revolution (1789–1799), which violently overthrew the aristocracy and deposed the monarch, King Louis XVI of France

Louis XVI (Louis-Auguste; ; 23 August 1754 – 21 January 1793) was the last king of France before the fall of the monarchy during the French Revolution. The son of Louis, Dauphin of France (1729–1765), Louis, Dauphin of France (son and heir- ...

(r. 1774–1792).

In the 19th century, the mathematician William Kingdon Clifford

William Kingdon Clifford (4 May 18453 March 1879) was a British mathematician and philosopher. Building on the work of Hermann Grassmann, he introduced what is now termed geometric algebra, a special case of the Clifford algebra named in his ...

, who was an early proponent of Darwinism

''Darwinism'' is a term used to describe a theory of biological evolution developed by the English naturalist Charles Darwin (1809–1882) and others. The theory states that all species of organisms arise and develop through the natural sel ...

, worked to eliminate obscurantism in England after hearing clerics—who privately agreed with him about evolution

Evolution is the change in the heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. It occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, re ...

—publicly denounce evolution as un-Christian heresy. Leo Strauss

Political philosophy

In the 20th century, the American conservativepolitical philosopher

Political philosophy studies the theoretical and conceptual foundations of politics. It examines the nature, scope, and legitimacy of political institutions, such as states. This field investigates different forms of government, ranging from de ...

Leo Strauss

Leo Strauss (September 20, 1899 – October 18, 1973) was an American scholar of political philosophy. He spent much of his career as a professor of political science at the University of Chicago, where he taught several generations of students an ...

and his neo-conservative adherents adopted the notion of government by the enlightened few as political strategy. He noted that intellectuals

An intellectual is a person who engages in critical thinking, research, and Human self-reflection, reflection about the nature of reality, especially the nature of society and proposed solutions for its normative problems. Coming from the wor ...

, dating from Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

, confronted the dilemma of either an informed populace "interfering" with government, or whether it were possible for good

In most contexts, the concept of good denotes the conduct that should be preferred when posed with a choice between possible actions. Good is generally considered to be the opposite of evil. The specific meaning and etymology of the term and its ...

politicians to be truthful and still govern to maintain a stable society—hence the noble lie necessary in securing public acquiescence. In ''The City and Man'' (1964), he discusses the myths in '' The Republic'' that Plato proposes effective governing requires, among them, the belief that the country (land) ruled by the state belongs to it (despite some having been conquered from others), and that citizenship derives from more than the accident of birth in the city-state. Thus, in the ''New Yorker'' magazine article "Selective Intelligence", Seymour Hersh

Seymour Myron Hersh (born April 8, 1937) is an American investigative journalist and political writer. He gained recognition in 1969 for exposing the My Lai massacre and its cover-up during the Vietnam War, for which he received the 1970 Pulitzer ...

observes that Strauss endorsed the " noble lie" concept: the myths politicians use in maintaining a cohesive society.

Shadia Drury

Shadia B. Drury (born 1950) is a Canadian academic and political commentator. She is a professor emerita at the University of Regina. In 2005, she was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada.

Early life and education

Drury was born in ...

criticized Strauss's acceptance of dissembling and deception of the populace as "the peculiar justice of the wise", whereas Plato proposed the noble lie as based upon moral

A moral (from Latin ''morālis'') is a message that is conveyed or a lesson to be learned from a story or event. The moral may be left to the hearer, reader, or viewer to determine for themselves, or may be explicitly encapsulated in a maxim. ...

good. In criticizing ''Natural Right and History'' (1953), she said that "Strauss thinks that the superiority of the ruling philosophers is an intellectual superiority and not a moral one ... eis the only interpreter who gives a sinister reading to Plato, and then celebrates him."

Esoteric texts

Leo Strauss also was criticized for proposing the notion of "esoteric" meanings to ancient texts, obscure knowledge inaccessible to the "ordinary" intellect. In ''Persecution and the Art of Writing'' (1952), he proposes that some philosophers write esoterically to avert persecution by the political or religious authorities, and, per his knowledge ofMaimonides

Moses ben Maimon (1138–1204), commonly known as Maimonides (, ) and also referred to by the Hebrew acronym Rambam (), was a Sephardic rabbi and Jewish philosophy, philosopher who became one of the most prolific and influential Torah schola ...

, Al Farabi, and Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

, proposed that an esoteric writing style is proper for the philosophic text. Rather than explicitly presenting his thoughts, the philosopher's esoteric writing compels the reader to think independently of the text, and so learn. In the , Socrates notes that writing does not reply to questions, but invites dialogue with the reader, thereby minimizing the problems of grasping the written word. Strauss noted that one of writing's political dangers is students' too-readily accepting dangerous ideas—as in the trial of Socrates

Socrates (; ; – 399 BC) was a Ancient Greek philosophy, Greek philosopher from Classical Athens, Athens who is credited as the founder of Western philosophy and as among the first moral philosophers of the Ethics, ethical tradition ...

, wherein the relationship with Alcibiades

Alcibiades (; 450–404 BC) was an Athenian statesman and general. The last of the Alcmaeonidae, he played a major role in the second half of the Peloponnesian War as a strategic advisor, military commander, and politician, but subsequently ...

was used to prosecute him.

For Leo Strauss, philosophers' texts offered the reader lucid "exoteric" (salutary) and obscure "esoteric" (true) teachings, which are concealed to the reader of ordinary intellect; emphasizing that writers often left contradictions and other errors to encourage the reader's more scrupulous (re-)reading of the text. In observing and maintaining the " exoteric—esoteric

Western esotericism, also known as the Western mystery tradition, is a wide range of loosely related ideas and movements that developed within Western society. These ideas and currents are united since they are largely distinct both from orthod ...

" dichotomy, Strauss was accused of obscurantism, and for writing esoterically.

Bill Joy

In the article " Why the Future Doesn't Need Us" (April 2000), the computer scientistBill Joy

William Nelson Joy (born November 8, 1954) is an American computer engineer and venture capitalist. He co-founded Sun Microsystems in 1982 along with Scott McNealy, Vinod Khosla, and Andy Bechtolsheim, and served as Chief Scientist and CTO ...

, then chief scientist at Sun Microsystems, in the sub-title of the article proposed that: "Our most powerful twenty-first-century technologies—robotics, genetic engineering, and nanotech—are threatening to make humans an endangered species", and said that:

Critics readily noted the obscurantism in Joy's elitist proposal for limiting the dissemination of "certain knowledge" in order to preserve society. A year later, in the ''Science and Technology Policy Yearbook 2001'', the American Association for the Advancement of Science

The American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) is a United States–based international nonprofit with the stated mission of promoting cooperation among scientists, defending scientific freedom, encouraging scientific responsib ...

answered Joy's propositions with the article "A Response to Bill Joy and the Doom-and-Gloom Technofuturists", wherein the computer scientists John Seely Brown and Paul Duguid said that Joy's proposal was a form of technological tunnel vision, and that the technologically derived problems are infeasible, for disregarding the influence of non-scientists upon such societal problems.

Appeal to emotion

In the essay "Why I Am Not a Conservative" (1960), the economist

In the essay "Why I Am Not a Conservative" (1960), the economist Friedrich von Hayek

Friedrich August von Hayek (8 May 1899 – 23 March 1992) was an Austrian-born British academic and philosopher. He is known for his contributions to political economy, political philosophy and intellectual history. Hayek shared the 1974 Nobe ...

said that political conservatism

Conservatism is a Philosophy of culture, cultural, Social philosophy, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, Convention (norm), customs, and Value (ethics and social science ...

is ideologically unrealistic, because of the conservative person's inability to adapt to changing human realities and refusal to offer a positive political program that benefits everyone in a society. In that context, Hayek used the term ''obscurantism'' differently, to denote and describe the denial

Denial, in colloquial English usage, has at least three meanings:

* the assertion that any particular statement or allegation, whose truth is uncertain, is not true;

* the refusal of a request; and

* the assertion that a true statement is fal ...

of the empirical truth of scientific theory, because of the disagreeable moral

A moral (from Latin ''morālis'') is a message that is conveyed or a lesson to be learned from a story or event. The moral may be left to the hearer, reader, or viewer to determine for themselves, or may be explicitly encapsulated in a maxim. ...

consequences that might arise from acceptance of fact.

Deliberate obscurity

The second sense of ''obscurantism'' denotes making knowledge abstruse, that is, difficult to grasp. In the 19th and 20th centuries obscurantism became a polemical term for accusing an author of deliberately writing obscurely, in order to hide his or herintellectual

An intellectual is a person who engages in critical thinking, research, and Human self-reflection, reflection about the nature of reality, especially the nature of society and proposed solutions for its normative problems. Coming from the wor ...

vacuousness. From that perspective, obscure (clouded, vague, abstruse) writing does not necessarily indicate that the writer has a poor grasp of the subject, because unintelligible writing sometimes is purposeful.Rorty, Richard (1989) ''Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, Ch. 6: "From Ironist Theory to Private Allusions: Derrida". .

Aristotle

Aristotle divided his own works into two classifications: " exoteric" and "

Aristotle divided his own works into two classifications: " exoteric" and "esoteric

Western esotericism, also known as the Western mystery tradition, is a wide range of loosely related ideas and movements that developed within Western society. These ideas and currents are united since they are largely distinct both from orthod ...

". Most scholars have understood this as a distinction of intended audience, where exoteric works were written for the public, and the esoteric works were more technical works intended for use within the Lyceum

The lyceum is a category of educational institution defined within the education system of many countries, mainly in Europe. The definition varies among countries; usually it is a type of secondary school. Basic science and some introduction to ...

. Modern scholars commonly assume these latter to be Aristotle's own (unpolished) lecture notes or, in some cases, possible notes by his students. However, the 5th-century neoplatonist

Neoplatonism is a version of Platonic philosophy that emerged in the 3rd century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and religion. The term does not encapsulate a set of ideas as much as a series of thinkers. Among the common id ...

Ammonius Hermiae writes that Aristotle's writing style is deliberately obscurantist so that "good people may for that reason stretch their mind even more, whereas empty minds that are lost through carelessness will be put to flight by the obscurity when they encounter sentences like these".

In contemporary discussions of virtue ethics

Virtue ethics (also aretaic ethics, from Greek []) is a philosophical approach that treats virtue and moral character, character as the primary subjects of ethics, in contrast to other ethical systems that put consequences of voluntary acts, pri ...

, Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

's ''Nicomachean Ethics

The ''Nicomachean Ethics'' (; , ) is Aristotle's best-known work on ethics: the science of the good for human life, that which is the goal or end at which all our actions aim. () It consists of ten sections, referred to as books, and is closely ...

'' (''The Ethics'') stands accused of ethical obscurantism, because of the technical, philosophic language and writing style, and their purpose being the education

Education is the transmission of knowledge and skills and the development of character traits. Formal education occurs within a structured institutional framework, such as public schools, following a curriculum. Non-formal education als ...

of a cultured governing elite

In political and sociological theory, the elite (, from , to select or to sort out) are a small group of powerful or wealthy people who hold a disproportionate amount of wealth, privilege, political power, or skill in a group. Defined by the ...

.Lisa van Alstyne, "Aristotle's Alleged Ethical Obscurantism". ''Philosophy''. Vol. 73, No. 285 (July, 1998), pp. 429–452.

Kant

Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant (born Emanuel Kant; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German Philosophy, philosopher and one of the central Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works ...

employed technical terms that were not commonly understood by the layman. Arthur Schopenhauer

Arthur Schopenhauer ( ; ; 22 February 1788 – 21 September 1860) was a German philosopher. He is known for his 1818 work ''The World as Will and Representation'' (expanded in 1844), which characterizes the Phenomenon, phenomenal world as ...

contended that post-Kantian philosophers such as Johann Gottlieb Fichte

Johann Gottlieb Fichte (; ; 19 May 1762 – 29 January 1814) was a German philosopher who became a founding figure of the philosophical movement known as German idealism, which developed from the theoretical and ethical writings of Immanuel Ka ...

, Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling

Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling (; 27 January 1775 – 20 August 1854), later (after 1812) von Schelling, was a German philosopher. Standard histories of philosophy make him the midpoint in the development of German idealism, situating him be ...

, and Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (27 August 1770 – 14 November 1831) was a 19th-century German idealist. His influence extends across a wide range of topics from metaphysical issues in epistemology and ontology, to political philosophy and t ...

deliberately imitated the abstruse style of writing practiced by Kant.

Hegel

G. W. F. Hegel

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (27 August 1770 – 14 November 1831) was a 19th-century German idealism, German idealist. His influence extends across a wide range of topics from metaphysical issues in epistemology and ontology, to political phi ...

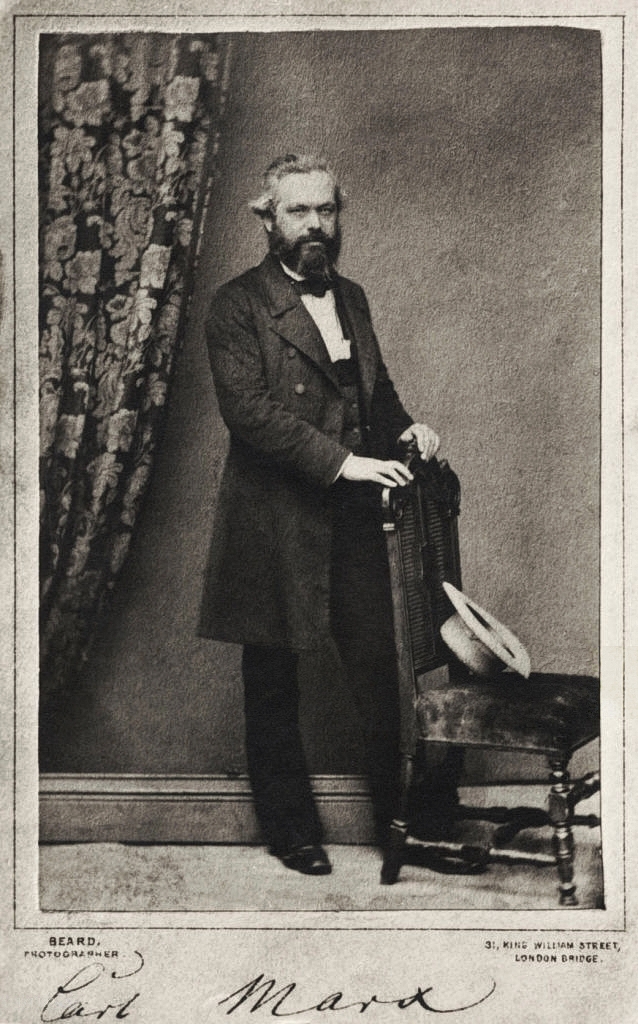

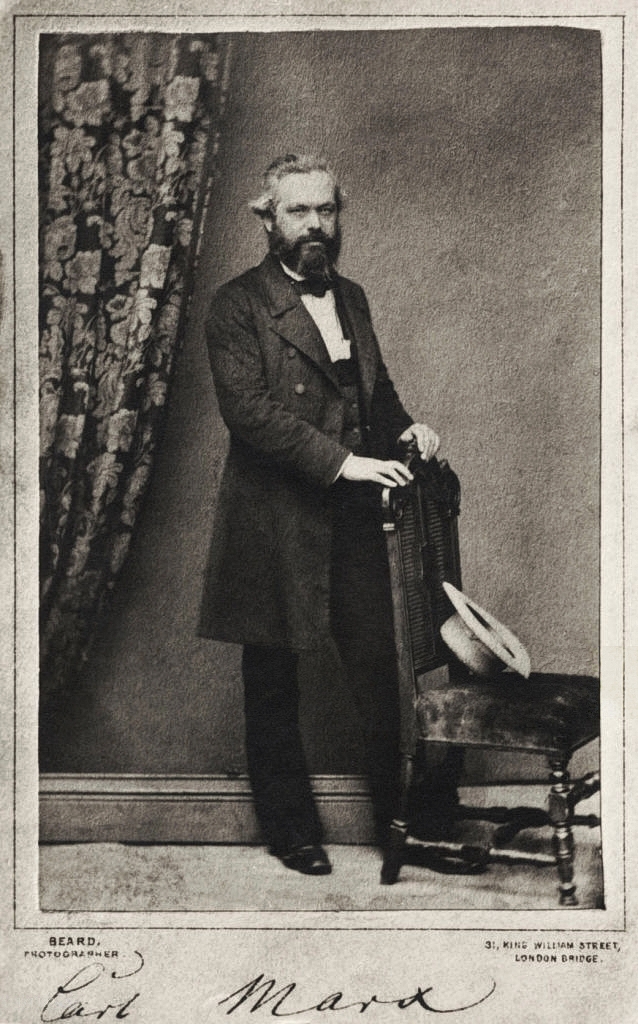

's philosophy, and the philosophies of those he influenced, especially Karl Marx

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

, have been accused of obscurantism. Analytic and positivistic philosophers, such as A. J. Ayer, Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British philosopher, logician, mathematician, and public intellectual. He had influence on mathematics, logic, set theory, and various areas of analytic ...

, and the critical-rationalist Karl Popper

Sir Karl Raimund Popper (28 July 1902 – 17 September 1994) was an Austrian–British philosopher, academic and social commentator. One of the 20th century's most influential philosophers of science, Popper is known for his rejection of the ...

, accused Hegel and Hegelianism

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (27 August 1770 – 14 November 1831) was a 19th-century German idealism, German idealist. His influence extends across a wide range of topics from metaphysical issues in epistemology and ontology, to political phi ...

of being obscure. About Hegel's philosophy, Schopenhauer wrote that it is "a colossal piece of mystification, which will yet provide posterity with an inexhaustible theme for laughter at our times, that it is a pseudo-philosophy paralyzing all mental powers, stifling all real thinking, and, by the most outrageous misuse of language, putting in its place the hollowest, most senseless, thoughtless, and, as is confirmed by its success, most stupefying verbiage".

Nevertheless, biographer Terry Pinkard notes: "Hegel has refused to go away, even in analytic philosophy, itself." Hegel was aware of his perceived obscurantism and perceived it as part of philosophical thinking: to accept and transcend the limitations of quotidian (everyday) thought and its concepts. In the essay "Who Thinks Abstractly?", he said that it is not the philosopher who thinks abstractly, but the layman, who uses concepts as givens

Givens is a surname.

Notable people

* Adele Givens, American comedy actress

* Bob Givens (1918–2017), American animator, character designer, and layout artist

* Charles J. Givens (1941–1998), American "get-rich-quick" author

* David G ...

that are immutable, without context. It is the philosopher who thinks concretely, because he transcends the limits of quotidian concept

A concept is an abstract idea that serves as a foundation for more concrete principles, thoughts, and beliefs.

Concepts play an important role in all aspects of cognition. As such, concepts are studied within such disciplines as linguistics, ...

s, in order to understand their broader context. This makes philosophical thought and language appear obscure, esoteric, and mysterious to the layman.

Marx

In his early works, Karl Marx criticized German and French philosophy, especially

In his early works, Karl Marx criticized German and French philosophy, especially German Idealism

German idealism is a philosophical movement that emerged in Germany in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. It developed out of the work of Immanuel Kant in the 1780s and 1790s, and was closely linked both with Romanticism and the revolutionary ...

, for its traditions of German irrationalism and ideologically motivated obscurantism. Later thinkers whom he influenced, such as the philosopher György Lukács

György Lukács (born Bernát György Löwinger; ; ; 13 April 1885 – 4 June 1971) was a Hungarian Marxist philosopher, literary historian, literary critic, and Aesthetics, aesthetician. He was one of the founders of Western Marxism, an inter ...

and social theorist Jürgen Habermas

Jürgen Habermas ( , ; ; born 18 June 1929) is a German philosopher and social theorist in the tradition of critical theory and pragmatism. His work addresses communicative rationality and the public sphere.

Associated with the Frankfurt S ...

, followed with similar arguments of their own. However, philosophers such as Karl Popper and Friedrich Hayek in turn criticized Marx and Marxist

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflic ...

philosophy as obscurantist (however, see above for Hayek's particular interpretation of the term).

Heidegger

Martin Heidegger

Martin Heidegger (; 26 September 1889 – 26 May 1976) was a German philosopher known for contributions to Phenomenology (philosophy), phenomenology, hermeneutics, and existentialism. His work covers a range of topics including metaphysics, art ...

, and those influenced by him, such as Jacques Derrida

Jacques Derrida (; ; born Jackie Élie Derrida;Peeters (2013), pp. 12–13. See also 15 July 1930 – 9 October 2004) was a French Algerian philosopher. He developed the philosophy of deconstruction, which he utilized in a number of his texts, ...

and Emmanuel Levinas

Emmanuel Levinas (born Emanuelis Levinas ; ; 12 January 1906 – 25 December 1995) was a French philosopher of Lithuanian Jewish ancestry who is known for his work within Jewish philosophy, existentialism, and phenomenology, focusing on the rel ...

, have been labeled obscurantists by critics from analytic philosophy and the Frankfurt School of critical theory. Of Heidegger, Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British philosopher, logician, mathematician, and public intellectual. He had influence on mathematics, logic, set theory, and various areas of analytic ...

wrote: "his philosophy is extremely obscure. One cannot help suspecting that language is here running riot. An interesting point in his speculations is the insistence that nothingness is something positive. As with much else in Existentialism, this is a psychological observation made to pass for logic." That is Russell's complete entry on Heidegger, and it expresses the sentiments of many 20th-century analytic philosophers concerning Heidegger.

Derrida

In their obituaries "Jacques Derrida

Jacques Derrida (; ; born Jackie Élie Derrida;Peeters (2013), pp. 12–13. See also 15 July 1930 – 9 October 2004) was a French Algerian philosopher. He developed the philosophy of deconstruction, which he utilized in a number of his texts, ...

, Abstruse Theorist, Dies at 74" (10 October 2004) and "Obituary of Jacques Derrida, French intellectual" (21 October 2004), ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'' newspaper and ''The Economist

''The Economist'' is a British newspaper published weekly in printed magazine format and daily on Electronic publishing, digital platforms. It publishes stories on topics that include economics, business, geopolitics, technology and culture. M ...

'' magazine described Derrida as a deliberately obscure philosopher.

In '' Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity'' (1989), Richard Rorty

Richard McKay Rorty (October 4, 1931 – June 8, 2007) was an American philosopher, historian of ideas, and public intellectual. Educated at the University of Chicago and Yale University, Rorty's academic career included appointments as the Stu ...

proposed that in ''The Post Card: From Socrates to Freud and Beyond'' (1978), Jacques Derrida purposefully used undefinable words (e.g. différance) and used defined words in contexts so diverse that they render the words unintelligible, hence, the reader is unable to establish a context for his literary self. In that way, the philosopher Derrida escapes metaphysical accounts of his work. Since the work ostensibly contains no metaphysics, Derrida has, consequently, escaped metaphysics.

Derrida's philosophic work is especially controversial among American and British academics, as when the University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a Public university, public collegiate university, collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209, the University of Cambridge is the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, wo ...

awarded him an honorary doctorate, despite opposition from among the Cambridge philosophy faculty and analytical philosophers worldwide. In opposing the decision, philosophers including Barry Smith, W. V. O. Quine, David Armstrong, Ruth Barcan Marcus, René Thom, and twelve others, published a letter of protestation in ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British Newspaper#Daily, daily Newspaper#National, national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its modern name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its si ...

'' of London, arguing that "his works employ a written style that defies comprehension ... husAcademic status based on what seems to us to be little more than semi-intelligible attacks upon the values of reason, truth, and scholarship is not, we submit, sufficient grounds for the awarding of an honorary degree in a distinguished university."

In the ''New York Review of Books'' article "An Exchange on Deconstruction" (February 1984), John Searle

John Rogers Searle (; born July 31, 1932) is an American philosopher widely noted for contributions to the philosophy of language, philosophy of mind, and social philosophy. He began teaching at UC Berkeley in 1959 and was Willis S. and Mario ...

comments on Deconstruction

In philosophy, deconstruction is a loosely-defined set of approaches to understand the relationship between text and meaning. The concept of deconstruction was introduced by the philosopher Jacques Derrida, who described it as a turn away from ...

: "anyone who reads deconstructive texts with an open mind is likely to be struck by the same phenomena that initially surprised me: the low level of philosophical argumentation, the deliberate obscurantism of the prose, the wildly exaggerated claims, and the constant striving to give the appearance of profundity, by making claims that seem paradoxical, but under analysis often turn out to be silly or trivial".

Lacan

Jacques Lacan

Jacques Marie Émile Lacan (, ; ; 13 April 1901 – 9 September 1981) was a French psychoanalyst and psychiatrist. Described as "the most controversial psycho-analyst since Sigmund Freud, Freud", Lacan gave The Seminars of Jacques Lacan, year ...

was an intellectual

An intellectual is a person who engages in critical thinking, research, and Human self-reflection, reflection about the nature of reality, especially the nature of society and proposed solutions for its normative problems. Coming from the wor ...

who defended obscurantism to a degree. To his students' complaint about the deliberate obscurity of his lectures, he replied: "The less you understand, the better you listen." In the 1973 seminar ''Encore'', he said that his (''Writings'') were not to be understood, but would effect a meaning in the reader, like that induced by mystical texts. The obscurity is not in his writing style, but in the repeated allusions to Hegel, derived from Alexandre Kojève

Alexandre Kojève (born Aleksandr Vladimirovich Kozhevnikov; 28 April 1902 – 4 June 1968) was a Russian-born French philosopher and international civil service, civil servant whose philosophical seminars had some influence on 20th-century Frenc ...

's lectures on Hegel, and similar theoretic divergences.

Sokal affair

The Sokal affair (1996) was a publishinghoax

A hoax (plural: hoaxes) is a widely publicised falsehood created to deceive its audience with false and often astonishing information, with the either malicious or humorous intent of causing shock and interest in as many people as possible.

S ...

that the professor of physics Alan Sokal

Alan David Sokal ( ; born January 24, 1955) is an American professor of mathematics at University College London and professor emeritus of physics at New York University. He works with statistical mechanics and combinatorics.

Sokal is a critic o ...

perpetrated on the editors and readers of ''Social Text

''Social Text'' is a peer-reviewed academic journal published by Duke University Press. Since its inception by an independent editorial collective in 1979, ''Social Text'' has addressed a wide range of social and cultural phenomena, covering ques ...

'', an academic journal

An academic journal (or scholarly journal or scientific journal) is a periodical publication in which Scholarly method, scholarship relating to a particular academic discipline is published. They serve as permanent and transparent forums for the ...

of post-modern

Postmodernism encompasses a variety of artistic, cultural, and philosophical movements that claim to mark a break from modernism

Modernism was an early 20th-century movement in literature, visual arts, and music that emphasized experi ...

cultural studies

Cultural studies is an academic field that explores the dynamics of contemporary culture (including the politics of popular culture) and its social and historical foundations. Cultural studies researchers investigate how cultural practices rel ...

that was not then a peer-reviewed

Peer review is the evaluation of work by one or more people with similar competencies as the producers of the work ( peers). It functions as a form of self-regulation by qualified members of a profession within the relevant field. Peer review ...

publication. In 1996, as an experiment testing editorial

An editorial, or leading article (UK) or leader (UK), is an article or any other written document, often unsigned, written by the senior editorial people or publisher of a newspaper or magazine, that expresses the publication's opinion about ...

integrity (fact-checking

Fact-checking is the process of verifying the factual accuracy of questioned reporting and statements. Fact-checking can be conducted before or after the text or content is published or otherwise disseminated. Internal fact-checking is such che ...

, verification, peer review, etc.), Sokal submitted "Transgressing the Boundaries: Towards a Transformative Hermeneutics of Quantum Gravity", a pseudoscientific

Pseudoscience consists of statements, beliefs, or practices that claim to be both scientific and factual but are incompatible with the scientific method. Pseudoscience is often characterized by contradictory, exaggerated or unfalsifiable cl ...

article proposing that physical reality is a social construct, in order to learn whether ''Social Text'' would "publish an article liberally salted with nonsense if: (a) it sounded good, and, (b) it flattered the editors' ideological preconceptions". Sokal's fake article was published in the spring/summer 1996 issue of ''Social Text'', which was dedicated to the science wars about the conceptual validity of scientific objectivity and the nature of scientific theory, among scientific realists and postmodern critics in American universities.

Sokal's reason for publication of a false article was that postmodernist critics questioned the objectivity of science, by criticising the scientific method

The scientific method is an Empirical evidence, empirical method for acquiring knowledge that has been referred to while doing science since at least the 17th century. Historically, it was developed through the centuries from the ancient and ...

and the nature of knowledge, usually in the disciplines of cultural studies, cultural anthropology

Cultural anthropology is a branch of anthropology focused on the study of cultural variation among humans. It is in contrast to social anthropology, which perceives cultural variation as a subset of a posited anthropological constant. The term ...

, feminist studies, comparative literature

Comparative literature studies is an academic field dealing with the study of literature and cultural expression across language, linguistic, national, geographic, and discipline, disciplinary boundaries. Comparative literature "performs a role ...

, media studies

Media studies is a discipline and field of study that deals with the content, history, and effects of various media; in particular, the mass media. Media studies may draw on traditions from both the social sciences and the humanities, but it mos ...

, and science and technology studies

Science and technology studies (STS) or science, technology, and society is an interdisciplinary field that examines the creation, development, and consequences of science and technology in their historical, cultural, and social contexts.

Histo ...

. Whereas the scientific realists countered that objective scientific knowledge exists, riposting that postmodernist critics almost knew nothing of the science they criticized. In the event, editorial deference to " academic authority" (the author-professor) prompted the editors of ''Social Text'' not to fact-check Sokal's manuscript by submitting it to peer review by a scientist.

Concerning the lack of editorial integrity shown by the publication of his fake article in ''Social Text'' magazine, Sokal addressed the matter in the May 1996 edition of the ''Lingua Franca

A lingua franca (; ; for plurals see ), also known as a bridge language, common language, trade language, auxiliary language, link language or language of wider communication (LWC), is a Natural language, language systematically used to make co ...

'' journal, in the article "A Physicist Experiments With Cultural Studies", in which he revealed that his transformative hermeneutics article was a parody

A parody is a creative work designed to imitate, comment on, and/or mock its subject by means of satire, satirical or irony, ironic imitation. Often its subject is an Originality, original work or some aspect of it (theme/content, author, style, e ...

, submitted "to test the prevailing intellectual standards", and concluded that, as an academic publication, ''Social Text'' ignored the requisite intellectual rigor

Rigour (British English) or rigor (American English; American and British English spelling differences#-our, -or, see spelling differences) describes a condition of stiffness or strictness. These constraints may be environmentally imposed, such ...

of verification and "felt comfortable publishing an article on quantum physics

Quantum mechanics is the fundamental physical Scientific theory, theory that describes the behavior of matter and of light; its unusual characteristics typically occur at and below the scale of atoms. Reprinted, Addison-Wesley, 1989, It is ...

without bothering to consult anyone knowledgeable in the subject".

Moreover, as a public intellectual

An intellectual is a person who engages in critical thinking, research, and Human self-reflection, reflection about the nature of reality, especially the nature of society and proposed solutions for its normative problems. Coming from the wor ...

, Sokal said that his hoax was an action protesting against the contemporary tendency towards obscurantism—abstruse, esoteric, and vague writing in the social sciences

Social science (often rendered in the plural as the social sciences) is one of the branches of science, devoted to the study of society, societies and the Social relation, relationships among members within those societies. The term was former ...

:

In short, my concern over the spread of subjectivist thinking is both intellectual and political. Intellectually, the problem with such doctrines is that they are false (when not simply meaningless). There is a real world; its properties are not merely social constructions; facts and evidence do matter. What sane person would contend otherwise? And yet, much contemporary academic theorizing consists precisely of attempts to blur these obvious truths—the utter absurdity of it all being concealed through obscure and pretentious language.As a pseudoscientific opus, the article "Transgressing the Boundaries: Towards a Transformative Hermeneutics of Quantum Gravity" is described as an exemplar "

pastiche

A pastiche () is a work of visual art, literature, theatre, music, or architecture that imitates the style or character of the work of one or more other artists. Unlike parody, pastiche pays homage to the work it imitates, rather than mocking ...

of left-wing

Left-wing politics describes the range of Ideology#Political ideologies, political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy either as a whole or of certain social ...

cant, fawning references, grandiose quotations, and outright nonsense, centered on the claim that physical reality is merely a social construct".

See also

*Anti-intellectualism

Anti-intellectualism is hostility to and mistrust of intellect, intellectuals, and intellectualism, commonly expressed as deprecation of education and philosophy and the dismissal of art, literature, history, and science as impractical, politica ...

* Cover-up

* Cult

Cults are social groups which have unusual, and often extreme, religious, spiritual, or philosophical beliefs and rituals. Extreme devotion to a particular person, object, or goal is another characteristic often ascribed to cults. The term ...

* Disinformation

Disinformation is misleading content deliberately spread to deceive people, or to secure economic or political gain and which may cause public harm. Disinformation is an orchestrated adversarial activity in which actors employ strategic dece ...

* Doublespeak

* Dumbing down

Dumbing down is the deliberate oversimplification of intellectual content in education, literature, cinema, news, video games, and culture. Originating in 1933, the term "dumbing down" was movie-business slang, used by screenplay writers, meanin ...

* Fundamentalism

Fundamentalism is a tendency among certain groups and individuals that are characterized by the application of a strict literal interpretation to scriptures, dogmas, or ideologies, along with a strong belief in the importance of distinguis ...

* Greenspeak

* Paternalism

* Paywall

A paywall is a method of restricting access to content (media), content, with a purchase or a subscription business model, paid subscription, especially news. Beginning in the mid-2010s, newspapers started implementing paywalls on their website ...

* Perception management

* Philosopher king

The philosopher king is a hypothetical ruler in whom political skill is combined with philosophical knowledge. The concept of a city-state ruled by philosophers is first explored in Plato's ''Republic'', written around 375 BC. Plato argued that ...

* Politicization of science

* Pseudophilosophy

* Psychological manipulation

In psychology, manipulation is defined as an action designed to influence or control another person, usually in an underhanded or subtle manner which facilitates one's personal aims. Methods someone may use to manipulate another person may includ ...

* Positivism

Positivism is a philosophical school that holds that all genuine knowledge is either true by definition or positivemeaning '' a posteriori'' facts derived by reason and logic from sensory experience.John J. Macionis, Linda M. Gerber, ''Soci ...

* Scientism

Scientism is the belief that science and the scientific method are the best or only way to render truth about the world and reality.

While the term was defined originally to mean "methods and attitudes typical of or attributed to natural scientis ...

* Whataboutism

Notes

References

External links

*Obscurantism in religion – Islamic Research Foundation International

{{Authority control Obfuscation Anti-intellectualism Knowledge Philosophical theories Propaganda techniques