Nonjuring on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Nonjuring schism refers to a split in the established churches of England, Scotland and Ireland, following the deposition and exile of

In modern usage,

In modern usage,

Regular clergy were largely undisturbed and although the Non-Juring bishops were suspended in February 1690, William kept them in office as he tried to negotiate a compromise. When this failed, in May 1691

Regular clergy were largely undisturbed and although the Non-Juring bishops were suspended in February 1690, William kept them in office as he tried to negotiate a compromise. When this failed, in May 1691

As a result, Stuart Catholicism was an insuperable barrier to their restoration, although attempts were made to convert James and his successors; when

As a result, Stuart Catholicism was an insuperable barrier to their restoration, although attempts were made to convert James and his successors; when

English Non Juring was largely a split ''within'' Episcopalianism, but this was not the case in Scotland, where the religious conflicts of the 17th century normalised the eviction of defeated opponents. In 1688, Scots were divided roughly equally into Presbyterians and Episcopalians, the latter concentrated in the

English Non Juring was largely a split ''within'' Episcopalianism, but this was not the case in Scotland, where the religious conflicts of the 17th century normalised the eviction of defeated opponents. In 1688, Scots were divided roughly equally into Presbyterians and Episcopalians, the latter concentrated in the

The political conflicts of the 1688 Glorious Revolution were reflected to a lesser degree in British North America and the Caribbean. The proximity of Catholic

The political conflicts of the 1688 Glorious Revolution were reflected to a lesser degree in British North America and the Caribbean. The proximity of Catholic

James II and VII

James VII and II (14 October 1633 16 September 1701) was King of England and King of Ireland as James II, and King of Scotland as James VII from the death of his elder brother, Charles II, on 6 February 1685. He was deposed in the Glorious ...

in the 1688 Glorious Revolution. As a condition of office, clergy were required to swear allegiance to the ruling monarch; for various reasons, some refused to take the oath to his successors William III and II and Mary II

Mary II (30 April 166228 December 1694) was List of English monarchs, Queen of England, List of Scottish monarchs, Scotland, and Monarchy of Ireland, Ireland, co-reigning with her husband, William III of England, William III & II, from 1689 unt ...

. These individuals were referred to as ''Non-juring'', from the Latin verb ''iūrō'', or ''jūrō'', meaning "to swear an oath".

In the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britai ...

, an estimated 2% of priests refused to swear allegiance in 1689, including nine bishop

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ...

s. Ordinary clergy were allowed to keep their positions but after efforts to compromise failed, the six surviving bishops were removed in 1691. The schismatic Non-Juror Church was formed in 1693 when Bishop Lloyd appointed his own bishops. His action was opposed by the majority of English Non-Jurors, who remained within the Church of England and are sometimes referred to as "crypto-Non-Jurors". Never large in numbers, the Non-Juror Church rapidly declined after 1715, although minor congregations remained in existence until the 1770s.

In Scotland, the 1690 religious settlement removed High Church

The term ''high church'' refers to beliefs and practices of Christian ecclesiology, liturgy, and theology that emphasize formality and resistance to modernisation. Although used in connection with various Christian traditions, the term originat ...

practices, Episcopal bishops and restored a Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their na ...

-structured Church of Scotland

The Church of Scotland ( sco, The Kirk o Scotland; gd, Eaglais na h-Alba) is the national church in Scotland.

The Church of Scotland was principally shaped by John Knox, in the Scottish Reformation, Reformation of 1560, when it split from t ...

, popularly known as the kirk. Those ministers who refused to accept these changes were expelled, leading to a divide recognised by the Scottish Episcopalians Act 1711, which created a separate Scottish Episcopal Church

The Scottish Episcopal Church ( gd, Eaglais Easbaigeach na h-Alba; sco, Scots Episcopal(ian) Kirk) is the ecclesiastical province of the Anglican Communion in Scotland.

A continuation of the Church of Scotland as intended by King James VI, and ...

. When George I became king in 1714, most Scottish Episcopalians refused to swear allegiance to the Hanoverian

The adjective Hanoverian is used to describe:

* British monarchs or supporters of the House of Hanover, the dynasty which ruled the United Kingdom from 1714 to 1901

* things relating to;

** Electorate of Hanover

** Kingdom of Hanover

** Province o ...

regime, creating a split that lasted until the death of Charles Stuart in 1788.

The Non-Juring movement in the Church of Ireland

The Church of Ireland ( ga, Eaglais na hÉireann, ; sco, label=Ulster-Scots, Kirk o Airlann, ) is a Christian church in Ireland and an autonomous province of the Anglican Communion. It is organised on an all-Ireland basis and is the second l ...

was insignificant, although it produced the Jacobite

Jacobite means follower of Jacob or James. Jacobite may refer to:

Religion

* Jacobites, followers of Saint Jacob Baradaeus (died 578). Churches in the Jacobite tradition and sometimes called Jacobite include:

** Syriac Orthodox Church, sometimes ...

propagandist Charles Leslie. The Episcopal church in North America was then part of the Church of England, but largely unaffected until after the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revolu ...

when the Scottish non-juror liturgy influenced that of the new U.S. Episcopal Church.

Origins

In modern usage,

In modern usage, Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their na ...

and Episcopalian implies differences in both governance and doctrine but this was not the case in the 17th and 18th centuries. ''Episcopalian'' structures were governed by bishops, appointed by the monarch; ''Presbyterian'' implied rule by Elder

An elder is someone with a degree of seniority or authority.

Elder or elders may refer to:

Positions Administrative

* Elder (administrative title), a position of authority

Cultural

* North American Indigenous elder, a person who has and tr ...

s, nominated by congregations. In an era when "true religion" and "true government" were assumed to be the same thing, arguments over church governance and practice often reflected political differences, not simply religious ones.

In 1688, all three established churches were Episcopalian in structure and Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

in doctrine, but faced different challenges. In England, over 90% belonged to the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britai ...

, while the majority of those excluded were Protestant Nonconformists who wanted to reverse the Act of Uniformity 1662

The Act of Uniformity 1662 (14 Car 2 c 4) is an Act of the Parliament of England. (It was formerly cited as 13 & 14 Ch.2 c. 4, by reference to the regnal year when it was passed on 19 May 1662.) It prescribed the form of public prayers, adm ...

and be allowed to rejoin the Church. In Ireland, over 75% of the population were Catholic, while the Church of Ireland

The Church of Ireland ( ga, Eaglais na hÉireann, ; sco, label=Ulster-Scots, Kirk o Airlann, ) is a Christian church in Ireland and an autonomous province of the Anglican Communion. It is organised on an all-Ireland basis and is the second l ...

was a minority even among Irish Protestants, the majority of whom were Nonconformists concentrated in Ulster

Ulster (; ga, Ulaidh or ''Cúige Uladh'' ; sco, label=Ulster Scots, Ulstèr or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional Irish provinces. It is made up of nine counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United Kin ...

. Nearly 98% of Scots were members of the Church of Scotland

The Church of Scotland ( sco, The Kirk o Scotland; gd, Eaglais na h-Alba) is the national church in Scotland.

The Church of Scotland was principally shaped by John Knox, in the Scottish Reformation, Reformation of 1560, when it split from t ...

, or kirk, far closer in doctrine to Irish Noncomformists than the Church of England and an organisational hybrid, with bishops presiding over Presbyterian structures.

James became king in 1685 with widespread support in all three kingdoms but this changed when his policies seemed to move beyond tolerance for Catholicism and into an attack on the established church. The 1638 to 1652 Wars of the Three Kingdoms

The Wars of the Three Kingdoms were a series of related conflicts fought between 1639 and 1653 in the kingdoms of Kingdom of England, England, Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland and Kingdom of Ireland, Ireland, then separate entities united in a pers ...

highlighted the dangers of religious division and moderates on both sides wanted to avoid a schism

A schism ( , , or, less commonly, ) is a division between people, usually belonging to an organization, movement, or religious denomination. The word is most frequently applied to a split in what had previously been a single religious body, suc ...

. Many supported James in 1685 from fear of civil war if he were bypassed; by 1688, it seemed only his deposition could prevent one. His prosecution of the Seven Bishops for seditious libel in June 1688 alienated the Tories

A Tory () is a person who holds a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalism and conservatism, which upholds the supremacy of social order as it has evolved in the English culture throughout history. Th ...

who formed his main English support base. Many viewed this as a violation of his coronation oath promising to maintain the primacy of the Church of England, making compliance with oaths a key issue.

English Non-Juring movement

"Non-Juror" generally means those who refused to take theOath of Allegiance

An oath of allegiance is an oath whereby a subject or citizen acknowledges a duty of allegiance and swears loyalty to a monarch or a country. In modern republics, oaths are sworn to the country in general, or to the country's constitution. Fo ...

to the new monarchs, William III and Mary II

Mary II (30 April 166228 December 1694) was List of English monarchs, Queen of England, List of Scottish monarchs, Scotland, and Monarchy of Ireland, Ireland, co-reigning with her husband, William III of England, William III & II, from 1689 unt ...

. It includes "Non-Abjurors", those who refused to swear the Oath of Abjuration

Abjuration is the solemn repudiation, abandonment, or renunciation by or upon oath, often the renunciation of citizenship or some other right or privilege. The term comes from the Latin ''abjurare'', "to forswear".

Abjuration of the realm

Abju ...

in 1701 and 1714, requiring them to deny the Stuart claim. Nine bishops became Non-Jurors, including the Archbishop of Canterbury, William Sancroft

William Sancroft (30 January 161724 November 1693) was the 79th Archbishop of Canterbury, and was one of the Seven Bishops imprisoned in 1688 for seditious libel against King James II, over his opposition to the king's Declaration of Indu ...

, along with five of the seven bishops prosecuted by James in June 1688. One study estimates that 339 members of the clergy became Non Jurors, around 2% of the total; of these, 80 subsequently conformed, offset by another 130 who refused the Oath of Abjuration in either 1701 or 1714. This ignores natural decline, so the actual number at any time would have been lower, while the majority were concentrated in areas like London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

and Newcastle, implying large parts of England were untouched by the controversy.

Identifying lay members is more complex, since only those holding a public office were required to swear. One source identifies a total of 584 clergy, schoolmasters and university dons as Non Jurors, but this almost certainly understates their numbers. The reasons for non-compliance varied; some, like Bishop Thomas Ken

Thomas Ken (July 1637 – 19 March 1711) was an English cleric who was considered the most eminent of the English non-juring bishops, and one of the fathers of modern English hymnody.

Early life

Ken was born in 1637 at Little Berkhampstead ...

, considered themselves bound by their oath to James, but did not oppose the new government and continued to attend church services. Others argued the new regime was illegitimate, since divine right and inheritance meant kings could not be removed, the so-called "state point". A more fundamental issue was the 'church point', the belief Parliament had no right to intervene in ecclesiastical affairs, whether appointing or removing bishops and clergy, or changes to church policies.

History

Regular clergy were largely undisturbed and although the Non-Juring bishops were suspended in February 1690, William kept them in office as he tried to negotiate a compromise. When this failed, in May 1691

Regular clergy were largely undisturbed and although the Non-Juring bishops were suspended in February 1690, William kept them in office as he tried to negotiate a compromise. When this failed, in May 1691 Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. ...

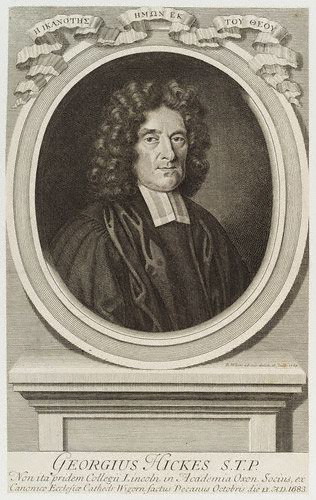

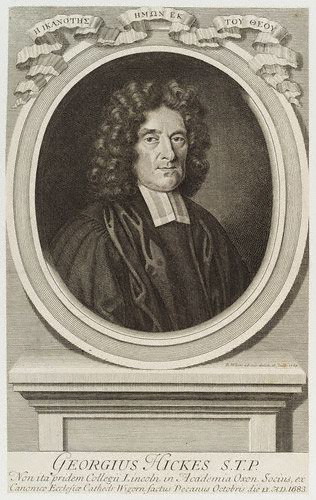

appointed six new bishops, three of the original nine having since died. In May 1692, Sancroft delegated his powers to Bishop Lloyd, who in May 1693 appointed Thomas Wagstaffe (1645–1712) and George Hickes (1642–1715) as new Non-Juring bishops. Lloyd argued he simply wanted to establish the principle Parliament had no right to deprive or appoint bishops, but it created a formal schism; the vast majority remained within the established church, while Wagstaffe refused to exercise his powers.

Some prominent Non-Jurors returned to the church in 1710, including Henry Dodwell

Henry Dodwell (October 16417 June 1711) was an Anglo-Irish scholar, theologian and controversial writer.

Life

Dodwell was born in Dublin in 1641. His father, William Dodwell, who lost his property in Connacht during the Irish rebellion, was ...

(1641–1711), and Robert Nelson (1656–1715). Hickes, whose hardline views on divine right and the primacy of Stuart authority led to his appointment as Charles II's chaplain in 1683, was the main driver behind the Non Juror church; it sharply declined after his death in 1715. The death of Thomas Wagstaffe in October 1712 left Hickes as the last surviving Non-Juring bishop. To ensure the survival of the church, Hickes and two bishops from the Scottish Episcopalian Church

The Scottish Episcopal Church ( gd, Eaglais Easbaigeach na h-Alba; sco, Scots Episcopal(ian) Kirk) is the ecclesiastical province of the Anglican Communion in Scotland.

A continuation of the Church of Scotland as intended by King James VI, and ...

, Archibald Campbell and James Gadderar, consecrated Jeremy Collier, Nathaniel Spinckes and Samuel Hawes as bishops in June 1713.

In 1719, the Non-Juring church split into "Usager" and "Non-Usager" factions, with both sides consecrating their own bishops. Effectively, Non-Usagers wanted an eventual reconciliation with the main Church of England, while Usagers wanted to restore traditional liturgies, including use of the long defunct 1549 Book of Common Prayer

The ''Book of Common Prayer'' (BCP) is the name given to a number of related prayer books used in the Anglican Communion and by other Christianity, Christian churches historically related to Anglicanism. The original book, published in 1549 ...

. In 1716, the Usagers initiated discussions with the Greek Orthodox Church

The term Greek Orthodox Church (Greek: Ἑλληνορθόδοξη Ἐκκλησία, ''Ellinorthódoxi Ekklisía'', ) has two meanings. The broader meaning designates "the entire body of Orthodox (Chalcedonian) Christianity, sometimes also call ...

on union, which continued until 1725 before both sides admitted failure. Despite the two factions agreeing to re-unite in 1732, divisions continued with a Usager contingent led by Bishop Archibald Campbell and a small London-based Non-Usager grouping under Bishop John Blackbourne.

By the early 1740s, significant Non-Juring congregations were restricted to Newcastle, London and Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of City of Salford, Salford to ...

. In 1741, Robert Gordon became the last regular Non-Juring bishop, his consecration being agreed by the ''de jure'' James III; he died in 1779 and his congregation in London was absorbed by the Scottish Episcopal church. This left a small congregation in Holborn

Holborn ( or ) is a district in central London, which covers the south-eastern part of the London Borough of Camden and a part (St Andrew Holborn (parish), St Andrew Holborn Below the Bars) of the Wards of the City of London, Ward of Farringdon ...

, which was strongly Jacobite and in 1788 refused to acknowledge George III, before disappearing in the 1790s. Bishop Campbell was succeeded by the Usager Thomas Deacon, who led a separate group in Manchester known as the Orthodox British Church, or "OBC". It strayed further away from the Church of England, investigating primitive liturgies and insisting on no State control and was Jacobite in sympathy; several members, including three of Deacon's sons, joined the Manchester Regiment

The Manchester Regiment was a line infantry regiment of the British Army in existence from 1881 until 1958. The regiment was created during the 1881 Childers Reforms by the amalgamation of the 63rd (West Suffolk) Regiment of Foot and the 96t ...

that participated in the 1745 Rising

The Jacobite rising of 1745, also known as the Forty-five Rebellion or simply the '45 ( gd, Bliadhna Theàrlaich, , ), was an attempt by Charles Edward Stuart to regain the British throne for his father, James Francis Edward Stuart. It took pl ...

. The OBC limped on into the early nineteenth century, but was wound up within a decade after the death of Bishop William Cartwright of Shrewsbury in 1799. There are suggestions elements of its theology resurfaced in the 1830s Oxford Movement

The Oxford Movement was a movement of high church members of the Church of England which began in the 1830s and eventually developed into Anglo-Catholicism. The movement, whose original devotees were mostly associated with the University of O ...

.

Numbers and significance

Membership of the schismatic church was initially confined to clerics, then later expanded into the lay population. Largely restricted to urban areas, its congregations continually shifted, making it difficult to assess numbers; it is suggested these were negligible, certainly fewer than Catholics, who were around 1% of the population. Many more were so-called 'crypto-Non Jurors', those who remained with the established church after 1693, but shared some Non Juror concerns; while sympathetic to the Stuarts, only a few were active Jacobites. Typical of thisHigh Church

The term ''high church'' refers to beliefs and practices of Christian ecclesiology, liturgy, and theology that emphasize formality and resistance to modernisation. Although used in connection with various Christian traditions, the term originat ...

, Tory

A Tory () is a person who holds a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalism and conservatism, which upholds the supremacy of social order as it has evolved in the English culture throughout history. The ...

group was Lady Elizabeth Hastings

Lady Elizabeth Hastings (19 April 1682 – 21 December 1739), also known as Lady Betty, was an English philanthropist, religious devotee and supporter of women's education. She was an intelligent and energetic woman, with a wide circle of conn ...

, daughter of the Earl of Huntingdon

Earl of Huntingdon is a title which has been created several times in the Peerage of England. The medieval title (1065 creation) was associated with the ruling house of Scotland ( David of Scotland).

The seventh and most recent creation dates ...

, a Stuart loyalist. Their support was based on the 'church point', and they opposed measures seen as diminishing the primacy of the Church of England. These included the 1689 Toleration Act, and 'occasional conformity', allowing Catholics and Nonconformists limited freedom of worship.

As a result, Stuart Catholicism was an insuperable barrier to their restoration, although attempts were made to convert James and his successors; when

As a result, Stuart Catholicism was an insuperable barrier to their restoration, although attempts were made to convert James and his successors; when Prince Charles

Charles III (Charles Philip Arthur George; born 14 November 1948) is King of the United Kingdom and the 14 other Commonwealth realms. He was the longest-serving heir apparent and Prince of Wales and, at age 73, became the oldest person to ...

visited London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

in 1750, he was inducted into the Non-Juring church, probably by Bishop Robert Gordon. Despite their limited numbers, Non Juror clergy exercised significant influence over church policy. Many opposed post 1689 changes that moved the Church of England away from Laudian principles of authority, and allowed greater tolerance of different practices. This led to demands for Convocation

A convocation (from the Latin '' convocare'' meaning "to call/come together", a translation of the Greek ἐκκλησία ''ekklēsia'') is a group of people formally assembled for a special purpose, mostly ecclesiastical or academic.

In ac ...

, or church assembly, to have a greater say over policy; it is suggested this was a contest between a largely Tory, High Church clerical body, and Whig bishops. Francis Atterbury

Francis Atterbury (6 March 1663 – 22 February 1732) was an English man of letters, politician and bishop. A High Church Tory and Jacobite, he gained patronage under Queen Anne, but was mistrusted by the Hanoverian Whig ministries, and bani ...

, later associated with a 1722 Jacobite plot, was a prominent supporter of Convocation, although not a Non Juror himself.

Outside politics, the Non Juror movement had an impact far greater than often appreciated, which continues today. Lady Elizabeth was part of a network of wealthy High Church philanthropists, linked by Non-Jurors like Robert Nelson, who supported measures intended to eliminate 'un-Christian behaviour', including the conversion of Catholics and Nonconformists. In 1698, this group established the Society for the Propagation of Christian Knowledge, or SPCK, followed in 1701 by the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts

A society is a group of individuals involved in persistent social interaction, or a large social group sharing the same spatial or social territory, typically subject to the same political authority and dominant cultural expectations. Socie ...

, or SPG, which are still in existence. Other members included Joseph Smith

Joseph Smith Jr. (December 23, 1805June 27, 1844) was an American religious leader and founder of Mormonism and the Latter Day Saint movement. When he was 24, Smith published the Book of Mormon. By the time of his death, 14 years later, h ...

, renowned for converting English Catholics; in 1701, the SPG sent George Keith to New Jersey

New Jersey is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic States, Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern United States, Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York (state), New York; on the ea ...

to do the same with Quakers

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belief in each human's abil ...

.

Some later became early advocates of Methodism

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a group of historically related Christian denomination, denominations of Protestantism, Protestant Christianity whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John W ...

, which began as a reform movement within the Church of England. One of these was Lady Elizabeth Hastings' daughter-in-law, Selina Hastings (1707–1791), founder of the evangelical Methodist sect known as the Countess of Huntingdon's Connexion. Methodists were often accused of Jacobitism, because they rejected existing structures and practices; conversely, many "Jacobite" demonstrations during the 1730s were led by Tories hostile to the Welsh Methodist revival

The Welsh Methodist revival was an evangelical revival that revitalised Christianity in Wales during the 18th century. Methodist preachers such as Daniel Rowland, William Williams and Howell Harris were heavily influential in the movement. The ...

. Although associated with social conservatism, crypto Non-Jurors included Mary Astell

Mary Astell (12 November 1666 – 11 May 1731) was an English protofeminist writer, philosopher, and rhetorician. Her advocacy of equal educational opportunities for women has earned her the title "the first English feminist."Batchelor, Jennie, ...

(1666–1731), an educationalist sometimes called the first English feminist. Daughter of a wealthy, upper-class Non-Juror merchant, in 1709, she set up a girls' school in Chelsea, London

Chelsea is an affluent area in west London, England, due south-west of Charing Cross by approximately 2.5 miles. It lies on the north bank of the River Thames and for postal purposes is part of the south-western postal area.

Chelsea histori ...

. Supported by the SPCK, Nelson, Dodwell, Lady Elizabeth and Lady Catherine Jones, it is thought to be the first in England with an all-women Board of Governors.

Irish Non-Juring movement

TheChurch of Ireland

The Church of Ireland ( ga, Eaglais na hÉireann, ; sco, label=Ulster-Scots, Kirk o Airlann, ) is a Christian church in Ireland and an autonomous province of the Anglican Communion. It is organised on an all-Ireland basis and is the second l ...

was a minority, even among Irish Protestants, and during the 1689 Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. ...

called by James, four bishops sat in the Lords

Lords may refer to:

* The plural of Lord

Places

*Lords Creek, a stream in New Hanover County, North Carolina

* Lord's, English Cricket Ground and home of Marylebone Cricket Club and Middlesex County Cricket Club

People

*Traci Lords (born 1 ...

, with Anthony Dopping, Bishop of Meath acting as leader of the opposition. Non Juror Henry Dodwell was born and educated in Ireland, but spent his career in England, making William Sheridan, Bishop of Kilmore and Ardagh the most significant Irish Non Juror. Son of a Catholic convert, he lost office as a result, and later died in poverty in London. Only a handful of Irish clergy followed his example, the most notable being Jacobite

Jacobite means follower of Jacob or James. Jacobite may refer to:

Religion

* Jacobites, followers of Saint Jacob Baradaeus (died 578). Churches in the Jacobite tradition and sometimes called Jacobite include:

** Syriac Orthodox Church, sometimes ...

propagandist Charles Leslie.

As in England, many sympathised with aspects of Non Juror policy; John Pooley, Bishop of Raphoe, avoided taking the Oath of Abjuration until 1710, while Bishop Palliser was a long time correspondent of Dodwell and Non Juror historian Thomas Smith. Bishop Lindsay, later Archbishop of Armagh, was a close friend of Jacobite plotter Francis Atterbury, and himself accused of Jacobitism in 1714. However, most of these links appear to have been driven by friendship, rather than political belief.

Scottish Non Jurors and the Scottish Episcopal Church

English Non Juring was largely a split ''within'' Episcopalianism, but this was not the case in Scotland, where the religious conflicts of the 17th century normalised the eviction of defeated opponents. In 1688, Scots were divided roughly equally into Presbyterians and Episcopalians, the latter concentrated in the

English Non Juring was largely a split ''within'' Episcopalianism, but this was not the case in Scotland, where the religious conflicts of the 17th century normalised the eviction of defeated opponents. In 1688, Scots were divided roughly equally into Presbyterians and Episcopalians, the latter concentrated in the Highlands

Highland is a broad term for areas of higher elevation, such as a mountain range or mountainous plateau.

Highland, Highlands, or The Highlands, may also refer to:

Places Albania

* Dukagjin Highlands

Armenia

* Armenian Highlands

Australia

* So ...

, Banffshire

Banffshire ; sco, Coontie o Banffshire; gd, Siorrachd Bhanbh) is a historic county, registration county and lieutenancy area of Scotland. The county town is Banff, although the largest settlement is Buckie to the west. It borders the Mora ...

, Perthshire

Perthshire ( locally: ; gd, Siorrachd Pheairt), officially the County of Perth, is a historic county and registration county in central Scotland. Geographically it extends from Strathmore in the east, to the Pass of Drumochter in the nor ...

, Angus

Angus may refer to:

Media

* ''Angus'' (film), a 1995 film

* ''Angus Og'' (comics), in the ''Daily Record''

Places Australia

* Angus, New South Wales

Canada

* Angus, Ontario, a community in Essa, Ontario

* East Angus, Quebec

Scotland

* Angu ...

and Aberdeenshire

Aberdeenshire ( sco, Aiberdeenshire; gd, Siorrachd Obar Dheathain) is one of the 32 council areas of Scotland.

It takes its name from the County of Aberdeen which has substantially different boundaries. The Aberdeenshire Council area incl ...

. The 1690 General Assembly of the Church of Scotland

The General Assembly of the Church of Scotland is the sovereign and highest court of the Church of Scotland, and is thus the Church's governing body.''An Introduction to Practice and Procedure in the Church of Scotland'' by A. Gordon McGillivra ...

abolished bishops and expelled 200 ministers who refused to accept these changes.

As in England, many remained in place; Michael Fraser served as minister of Daviot and Dunlichty continuously from 1673 to 1726, despite being evicted in 1694 and joining both the 1715

Events

For dates within Great Britain and the British Empire, as well as in the Russian Empire, the "old style" Julian calendar was used in 1715, and can be converted to the "new style" Gregorian calendar (adopted in the British Empire i ...

and 1719 Risings. Moderates within the kirk facilitated the readmission of deprived ministers; from 1690 to 1693, 70 of the 200 returned after taking the Oath of Allegiance, plus another 116 after the 1695 Act of Toleration. In 1702, a contemporary estimated 200 of 796 parishes were held by Episcopalian ministers, but the numbers above suggest many were not Non Jurors.

Before 1690, differences were largely about governance, but as they dwindled in numbers, Scottish Episcopalians increasingly focused on doctrine. They saw the 1707 Union as an opportunity to regain power via a unified British church, and began using English liturgy to help this process. The 1711 Scottish Episcopalians Act gave a legal basis for the Scottish Episcopal Church

The Scottish Episcopal Church ( gd, Eaglais Easbaigeach na h-Alba; sco, Scots Episcopal(ian) Kirk) is the ecclesiastical province of the Anglican Communion in Scotland.

A continuation of the Church of Scotland as intended by King James VI, and ...

, while the 1712 Toleration Act provided legal protection for use of the Book of Common Prayer

The ''Book of Common Prayer'' (BCP) is the name given to a number of related prayer books used in the Anglican Communion and by other Christianity, Christian churches historically related to Anglicanism. The original book, published in 1549 ...

, whose rejection in 1637 sparked the Bishops' Wars

The 1639 and 1640 Bishops' Wars () were the first of the conflicts known collectively as the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Three Kingdoms, which took place in Scotland, England and Ireland. Others include the Irish Confederate Wars, the First ...

.

When George I succeeded Queen Anne in 1714, the church split into a majority Non-Juror element and Qualified Chapels, those willing to swear allegiance to the Hanoverian regime. Non-Juring Episcopalianism became a mark of Jacobite commitment and a high percentage of both Lowlanders and Highlanders who participated in the 1745 Rising came from this element of Scottish society.

Post 1745, many Non-Juror meeting houses were closed or destroyed, and further restrictions placed on their clergy and congregants. When Prince Charles died in 1788, he was succeeded by his brother Henry, a Catholic Cardinal, and the Episcopal Church now swore allegiance to George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Br ...

, ending the schism with the Qualified Chapels, although the Qualified Chapel in Montrose remained independent until 1920.

In 1788 Bishop Charles Rose of Dunblane, and one presbyter, James Brown of Montrose, refused to acknowledge George III and his family, forming a breakaway nonjuring church based in Edinburgh that acknowledged Henry Stuart. However, the church finally ended in 1808 with the death of their last clergyman Donald Macintosh, a noted Gaelic scholar. When the penal laws were finally lifted in 1792, the Church had fewer than 15,000 members, less than one percent of the Scottish population. Today, the Scottish Episcopal Church is sometimes pejorative

A pejorative or slur is a word or grammatical form expressing a negative or a disrespectful connotation, a low opinion, or a lack of respect toward someone or something. It is also used to express criticism, hostility, or disregard. Sometimes, a ...

ly referred to as the "English Kirk".

Non Jurors in North America

The political conflicts of the 1688 Glorious Revolution were reflected to a lesser degree in British North America and the Caribbean. The proximity of Catholic

The political conflicts of the 1688 Glorious Revolution were reflected to a lesser degree in British North America and the Caribbean. The proximity of Catholic New France

New France (french: Nouvelle-France) was the area colonized by Kingdom of France, France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to King ...

meant limited sympathy for James; in 1700, New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

banned Catholic priests from the state. However, Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the East Coast of the United States, Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography an ...

removed several Non Jurors from office in 1691.

Richard Welton became a Non Juror in 1714, losing his parish in Whitechapel

Whitechapel is a district in East London and the future administrative centre of the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It is a part of the East End of London, east of Charing Cross. Part of the historic county of Middlesex, the area formed a c ...

as a result; in 1724, he was ordained a bishop by Non-Usager Ralph Taylor, and moved to North America. He replaced John Urmiston as Rector

Rector (Latin for the member of a vessel's crew who steers) may refer to:

Style or title

*Rector (ecclesiastical), a cleric who functions as an administrative leader in some Christian denominations

*Rector (academia), a senior official in an edu ...

of Christ Church, Philadelphia

Christ Church is an Episcopal church in the Old City neighborhood of Philadelphia. Founded in 1695 as a parish of the Church of England, it played an integral role in the founding of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States. In 1785 ...

; Urmiston demanded he be reinstated, and the dispute drew in John Talbot, rector of St. Mary's Episcopal Church, Burlington, New Jersey since April 1704.

Episcopalian ministers were in short supply in North America, one reason being delays caused by the need for London to approve appointments; between 1712 and 1720, Talbot presented numerous petitions requesting the appointment of a bishop. On a visit to England in 1722, Taylor made him a Non Juror bishop, and when Pennsylvania Governor Sir William Keith informed the church authorities, Talbot and Welton were suspended. Talbot remained in North America, where he died in 1727; Welton returned to England in 1726, dying shortly afterwards in Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic, In recognized minority languages of Portugal:

:* mwl, República Pertuesa is a country located on the Iberian Peninsula, in Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Macaronesian ...

.

Failure to establish a colonial episcopate was partly due to opposition by American Nonconformists; combined with the activities of the SPG, they viewed it as an attempt to impose a state church. In 1815, John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, attorney, diplomat, writer, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Befor ...

claimed a key element in mobilising popular support for the 1773 American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revolu ...

was the "apprehension of Episcopacy”.

After the outbreak of the Revolution, many Episcopal ministers remained loyal to the London government, and were removed. In Pennsylvania, most supported the Patriots, including William White, who set out principles establishing the American Episcopal Church

The Episcopal Church, based in the United States with additional dioceses elsewhere, is a member church of the worldwide Anglican Communion. It is a mainline Protestant denomination and is divided into nine provinces. The presiding bishop of ...

. These were accepted by all the states, apart from Connecticut

Connecticut () is the southernmost state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. Its cap ...

, which insisted each state must be controlled by its own bishop.

Connecticut sent Loyalist Samuel Seabury to England to be made a bishop, but since he could not take the required Oath of Allegiance to George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Br ...

, he was consecrated instead by the Scottish church in November 1784. Concerned at the prospect of another schism, Parliament agreed to waive the oath, and on 4 February 1787, White was consecrated Bishop of Pennsylvania by the Archbishop of Canterbury.

Prominent Nonjurors

*Hilkiah Bedford

Hilkiah Bedford (1663–1724) was an English clergyman, a nonjuror and writer, imprisoned as the author of a book really by George Harbin.

Life

He was born in Hosier Lane, near West Smithfield, London, where his father was a mathematical instrum ...

(1663–1724), chaplain to Bishop Ken, author of ''Vindication of the Church of England'' (1710)

* John Blackbourne (1681–1741), Non-Usager Bishop

* Charles Booth (d. c. 1810), last consecrated irregular Non-juring bishop

* William Bowyer the Younger (1699–1777), "the learned printer"

* Thomas Brett (1667–1743), of Spring Garden, liturgical scholar, Nonjuring bishop

* Archibald Campbell (d. 1744), Scottish bishop, usager bishop, author of ''The Middle State''

* William Cartwright (1730–99), Nonjuring Bishop in Shrewsbury

Shrewsbury ( , also ) is a market town, civil parish, and the county town of Shropshire, England, on the River Severn, north-west of London; at the 2021 census, it had a population of 76,782. The town's name can be pronounced as either 'S ...

* Jeremy Collier

Jeremy Collier (; 23 September 1650 – 26 April 1726) was an English theatre critic, non-juror bishop and theologian.

Life

Born Jeremiah Collier, in Stow cum Quy, Cambridgeshire, Collier was educated at Caius College, University of Cambrid ...

(1650–1726), Nonjuring primus, ecclesiastical historian, writer, and critic

* Thomas Deacon (1697–1753), stepson of Jeremy Collier, liturgical scholar, bishop of Manchester;

* Henry Dodwell

Henry Dodwell (October 16417 June 1711) was an Anglo-Irish scholar, theologian and controversial writer.

Life

Dodwell was born in Dublin in 1641. His father, William Dodwell, who lost his property in Connacht during the Irish rebellion, was ...

(1641–1711), Anglo-Irish patristic scholar, Oxford don, author of ''The Case in View''

* Elijah Fenton (1683–1730), poet

* Robert Forbes (1708–1775), Bishop of Ross and Caithness

Caithness ( gd, Gallaibh ; sco, Caitnes; non, Katanes) is a historic county, registration county and lieutenancy area of Scotland.

Caithness has a land boundary with the historic county of Sutherland to the west and is otherwise bounded b ...

and historian of the Jacobite Rising of 1745

The Jacobite rising of 1745, also known as the Forty-five Rebellion or simply the '45 ( gd, Bliadhna Theàrlaich, , ), was an attempt by Charles Edward Stuart to regain the British throne for his father, James Francis Edward Stuart. It took ...

* Marmaduke Fothergill

The Reverend Marmaduke Fothergill (1652 – 1731) was a Yorkshire clergyman, a scholar of Christian liturgy and collector of books. His donated collection is held as the Fothergill Collection at York Minster Library. It includes some titles which ...

(1652–1731), Vicar of Skipwith and antiquarian

* Henry Gandy

Henry Gandy (1649–1734) was an English non-juring bishop.

Life

The son of John Gandy of South Brent, Devon, he was born on 14 October 1649; his father was a priest of the Church of England who had been deprived of his living during the English ...

(1649–1734), bishop in Non-Usager succession

* Thomas Garnett (d. 1818), of Manchester, bishop in irregular usager line

* Robert Gordon (1703–1779), last bishop in the regular Nonjuring succession. Also called Gordoun.

* Lady Elizabeth Hastings

Lady Elizabeth Hastings (19 April 1682 – 21 December 1739), also known as Lady Betty, was an English philanthropist, religious devotee and supporter of women's education. She was an intelligent and energetic woman, with a wide circle of conn ...

(1682–1739); philanthropist, early supporter of Methodism

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a group of historically related Christian denomination, denominations of Protestantism, Protestant Christianity whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John W ...

* Thomas Hearne (1678 – 1735), antiquarian and diarist

* Charles Jennens

Charles Jennens (1700 – 20 November 1773) was an English landowner and patron of the arts. As a friend of Handel, he helped author the libretti of several of his oratorios, most notably ''Messiah''.

Life

Jennens was brought up at Gopsall H ...

(1700–73), librettist for Handel's ''Messiah'', S''aul'', ''Belshazzar

Belshazzar ( Babylonian cuneiform: ''Bēl-šar-uṣur'', meaning "Bel, protect the king"; ''Bēlšaʾṣṣar'') was the son and crown prince of Nabonidus (556–539 BC), the last king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire. Through his mother he might ...

,'' and other oratorios

* Charles Leslie (1650–1721), Jacobite propagandist, author of ''The Rehearsal'' and ''Short and Easy Method with the Deists''

* Robert Nelson (1656–1715), founding member of the Society for the Propagation of Christian Knowledge;

* Samuel Pepys

Samuel Pepys (; 23 February 1633 – 26 May 1703) was an English diarist and naval administrator. He served as administrator of the Royal Navy and Member of Parliament and is most famous for the diary he kept for a decade. Pepys had no marit ...

(1633–1703), Secretary to the Admiralty under Charles II and James II, diarist.

* Thomas Podmore (1705–84), nonjuring Deacon in Shrewsbury. Author of 'The Layman's Apology etc.'

* Joseph Smith

Joseph Smith Jr. (December 23, 1805June 27, 1844) was an American religious leader and founder of Mormonism and the Latter Day Saint movement. When he was 24, Smith published the Book of Mormon. By the time of his death, 14 years later, h ...

(1670–1756), Provost of The Queen's College, Oxford

The Queen's College is a constituent college of the University of Oxford, England. The college was founded in 1341 by Robert de Eglesfield in honour of Philippa of Hainault. It is distinguished by its predominantly neoclassical architecture, ...

* Thomas Smith (1638–1710), historian and librarian

* Richard Rawlinson

Richard Rawlinson FRS (3 January 1690 – 6 April 1755) was an English clergyman and antiquarian collector of books and manuscripts, which he bequeathed to the Bodleian Library, Oxford.

Life

Richard Rawlinson was a younger son of Sir Thomas ...

(1690–1755) clergyman, book collector, antiquarian, and nonjuring bishop

* Ralph Taylor (1647–1722), nonjuring bishop in Non-Usager line

* John Urry (1666–1715), literary scholar, editor of Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer (; – 25 October 1400) was an English poet, author, and civil servant best known for '' The Canterbury Tales''. He has been called the "father of English literature", or, alternatively, the "father of English poetry". He w ...

* Thomas Wagstaffe the Elder (1645–1712), nonjuring bishop and vindicator of Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

* Thomas Wagstaffe the Younger (1692–1770), usager controversialist, later Anglican Chaplain at the Stuart court in Rome

Notes

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

* {{Authority control Anglicanism History of the Church of England History of the British Isles Schisms in Christianity Jacobitism James II of England Glorious Revolution Oaths of allegiance