Neo-Jacobite Revival on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Neo-Jacobite Revival was a political movement active during the 25 years before the

In 1889, the New Gallery in London put on a major exhibition of works related to the House of Stuart. Queen Victoria lent a number of items to the exhibition, as did the wife of her son

In 1889, the New Gallery in London put on a major exhibition of works related to the House of Stuart. Queen Victoria lent a number of items to the exhibition, as did the wife of her son

The continuing Order of the White Rose focused on a romantic ideal of a Jacobite past, expressed through the arts. Art dealer

The continuing Order of the White Rose focused on a romantic ideal of a Jacobite past, expressed through the arts. Art dealer

First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

. The movement was monarchist

Monarchism is the advocacy of the system of monarchy or monarchical rule. A monarchist is an individual who supports this form of government independently of any specific monarch, whereas one who supports a particular monarch is a royalist. C ...

, and had the specific aim of replacing British parliamentary democracy

A parliamentary system, or parliamentary democracy, is a form of government where the head of government (chief executive) derives their democratic legitimacy from their ability to command the support ("confidence") of a majority of the legisl ...

with a restored monarch from the deposed House of Stuart

The House of Stuart, originally spelled Stewart, also known as the Stuart dynasty, was a dynasty, royal house of Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland, Kingdom of England, England, Kingdom of Ireland, Ireland and later Kingdom of Great Britain, Great ...

.

The reign of the House of Stuart

TheHouse of Stuart

The House of Stuart, originally spelled Stewart, also known as the Stuart dynasty, was a dynasty, royal house of Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland, Kingdom of England, England, Kingdom of Ireland, Ireland and later Kingdom of Great Britain, Great ...

was a European royal house

A dynasty is a sequence of rulers from the same family, usually in the context of a monarchy, monarchical system, but sometimes also appearing in republics. A dynasty may also be referred to as a "house", "family" or "clan", among others.

H ...

that originated in Scotland. Nine Stuart monarchs ruled Scotland alone from 1371 until 1603. The last of these, King James VI

James VI and I (James Charles Stuart; 19 June 1566 – 27 March 1625) was King of Scotland as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the Scottish and English crowns on 24 March 1603 until ...

of Scotland became King James I of England and Ireland after the death of Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was List of English monarchs, Queen of England and List of Irish monarchs, Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. She was the last and longest reigning monarch of the House of Tudo ...

in the Union of the Crowns

The Union of the Crowns (; ) was the accession of James VI of Scotland to the throne of the Kingdom of England as James I and the practical unification of some functions (such as overseas diplomacy) of the two separate realms under a single ...

. The Stuarts ruled the United Kingdom until 1714, when Queen Anne died. Parliament had passed the Act of Settlement 1701

The Act of Settlement ( 12 & 13 Will. 3. c. 2) is an act of the Parliament of England that settled the succession to the English and Irish crowns to only Protestants, which passed in 1701. More specifically, anyone who became a Roman Catho ...

and the Act of Security 1704

The Act of Security 1704 (c. 3), also referred to as the Act for the Security of the Kingdom, was a response by the Parliament of Scotland to the Parliament of England's Act of Settlement 1701. Anne, Queen of Great Britain, Queen Anne's last su ...

, which transferred the Crown

The Crown is a political concept used in Commonwealth realms. Depending on the context used, it generally refers to the entirety of the State (polity), state (or in federal realms, the relevant level of government in that state), the executive ...

to the House of Hanover

The House of Hanover ( ) is a European royal house with roots tracing back to the 17th century. Its members, known as Hanoverians, ruled Hanover, Great Britain, Ireland, and the British Empire at various times during the 17th to 20th centurie ...

, ending the line of Stuart monarchs.

James claimed the Divine right of kings – meaning that he believed his authority to rule was divinely inspired. He considered his decisions were not subject to 'interference' by either Parliament or the Church, a political view that would remain remarkably consistent among his Stuart successors. When Parliament passed the acts that ended the rule of the House of Stuart, they effectively claimed that the monarch's power was derived from Parliament, not God.

Jacobitism

The core Jacobite belief was in the divine right of kings, and the restoration of the House of Stuart to the throne. However, Jacobitism was a complex mix of ideas; in Ireland, it was associated with tolerance for Catholicism and the reversal of the land settlements of the 17th century. After 1707, many Scottish Jacobites wanted to undo the Acts of Union that created Great Britain but opposed the idea of Divine right.Ideology

Although Jacobite ideology was varied, it broadly held to four main tenets: * The divine right of kings and the "accountability of Kings to God alone", * The inalienable hereditary right of succession. * The "unequivocal scriptural injunction of non-resistance and passive obedience", * ThatJames II of England

James II and VII (14 October 1633 – 16 September 1701) was King of England and Monarchy of Ireland, Ireland as James II and King of Scotland as James VII from the death of his elder brother, Charles II of England, Charles II, on 6 February 1 ...

had been illegally deprived of his throne, therefore the House of Stuart should be restored to the throne.

The majority of Irish people supported James II due to his 1687 Declaration for the Liberty of Conscience, which granted religious freedom to all denominations in England and Scotland, and also due to James II's promise to the Irish Parliament of an eventual right to self-determination.

Religion

Jacobitism was closely linked withCatholicism

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

, particularly in Ireland where Catholics formed about 75% of the population. In Britain, Catholics were a small minority by 1689 and the bulk of Jacobite support came from High Church Anglicans. In Scotland (excluding the Highlands and the Isles), it is estimated that about 2% of the population were Catholic, in addition to an Episcopalian minority.

Jacobite rebellions: 1680 to 1750

Various groups of Jacobites attempted to overthrow Parliament during the 17th and 18th centuries. Significant uprisings included the 1689–1691Williamite War in Ireland

The Williamite War in Ireland took place from March 1689 to October 1691. Fought between Jacobitism, Jacobite supporters of James II of England, James II and those of his successor, William III of England, William III, it resulted in a Williamit ...

, a number of Jacobite revolts in Scotland and England between 1689 and 1746, and a number of unsuccessful minor plots. The collapse of the 1745 rising

The Jacobite rising of 1745 was an attempt by Charles Edward Stuart to regain the Monarchy of Great Britain, British throne for his father, James Francis Edward Stuart. It took place during the War of the Austrian Succession, when the bulk of t ...

in Scotland ended Jacobitism as a serious political movement.

However, the planned French invasion of Britain (1759)

France planned to invade Great Britain in 1759 during the Seven Years' War. 100,000 French soldiers were to land in Britain to end British involvement in the war. Due to various factors, including naval defeats at the Battle of Lagos and the B ...

was to destroy British power overseas and to restore the Jacobite claimants. It drew in a large part of French military resources, but was never launched because the Royal Navy kept control of the mouth of the Channel. As a result, French forces in Canada and India lacked resources and shipping, and were lost. Without the Jacobite need for support, arguably France could have expanded its empire in India and North America in the 1750s. Instead, the British had a " Year of Victories" in 1759.

Underground Jacobitism: 1750 to 1880

In the years immediately after 1745, Jacobitism was rigorously suppressed. Jacobite sympathisers moved underground, forming secret clubs and societies to discuss their ideas in private, especially in certain areas of the United Kingdom. John Shaw's Club, in Manchester was founded in 1735 and had several prominent members who had Jacobite sympathies, including its founder John Shaw,John Byrom

John Byrom, John Byrom of Kersal, or John Byrom of Manchester (29 February 1692 – 26 September 1763) was an English poet, the inventor of a revolutionary system of shorthand and later a significant landowner. He is most remembered as the wr ...

(who may have been a "double agent" reporting on Jacobite activity) and Thomas Gaskell.

North Wales

North Wales ( ) is a Regions of Wales, region of Wales, encompassing its northernmost areas. It borders mid Wales to the south, England to the east, and the Irish Sea to the north and west. The area is highly mountainous and rural, with Snowdon ...

was particularly known for its Jacobite sympathies. In the 18th century a group called the "Cycle Club" met to discuss Jacobite ideas – the full name of the club, rarely used in public was the "Cycle of the White Rose". The club was founded in 1710, and was closely associated with the Williams-Wynn family, though a number of prominent families in the Wrexham area were members. Charlotte Williams-Wynn was a member of the club, and Lady Watkin Wynne (the wife of Robert Watkin Wynne) was their patron from 1780 onwards. The Cycle Club continued in various forms until around 1860.

The Neo-Jacobite Revival: 1886 to 1920

The emergence of the Neo-Jacobites

In 1886, Bertram Ashburnham circulated a leaflet seeking Jacobite sympathisers, and amongst those who replied wasMelville Henry Massue

Melville Amadeus Henry Douglas Heddle de la Caillemotte de Massue de Ruvigny (26 April 1868 – 6 October 1921) was a British genealogist and author who was twice president of the Legitimist Jacobite League of Great Britain and Ireland. He styled ...

. Together they founded the Order of the White Rose

The Order of the White Rose of Finland (; ) is one of three official Order (decoration), orders in Finland, along with the Order of the Cross of Liberty, and the Order of the Lion of Finland. The President of Finland is the Grand Master of all ...

, a Jacobite group that was the spiritual successor to the Cycle Club. The Order was officially founded on 10 June 1886.

The Order attracted Irish and Scottish Nationalists to its ranks. While these various interests gathered under the banner of restoring the House of Stuart, they also had a common streak against the scientific and secular democratic norms of the time. Some even planned (but did not execute) a military overthrow of the Hanoverian monarchy, with the aim of putting Princess Maria Theresa on the British throne. See ''Jacobite succession

The Jacobite succession is the line through which Jacobites believed that the crowns of England, Scotland, and Ireland should have descended, applying male preference primogeniture, since the deposition of James II and VII in 1688 and his deat ...

''.

In parallel the Anglo-Catholic Oxford Movement

The Oxford Movement was a theological movement of high-church members of the Church of England which began in the 1830s and eventually developed into Anglo-Catholicism. The movement, whose original devotees were mostly associated with the Un ...

had revived sympathy for Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

and revered him as a martyr. This certainly played into the Jacobite narrative, and this thread of near-Jacobite thought was kept alive by men such as Hurrell Froude and James Yeowell who was known as 'the last Jacobite in England".

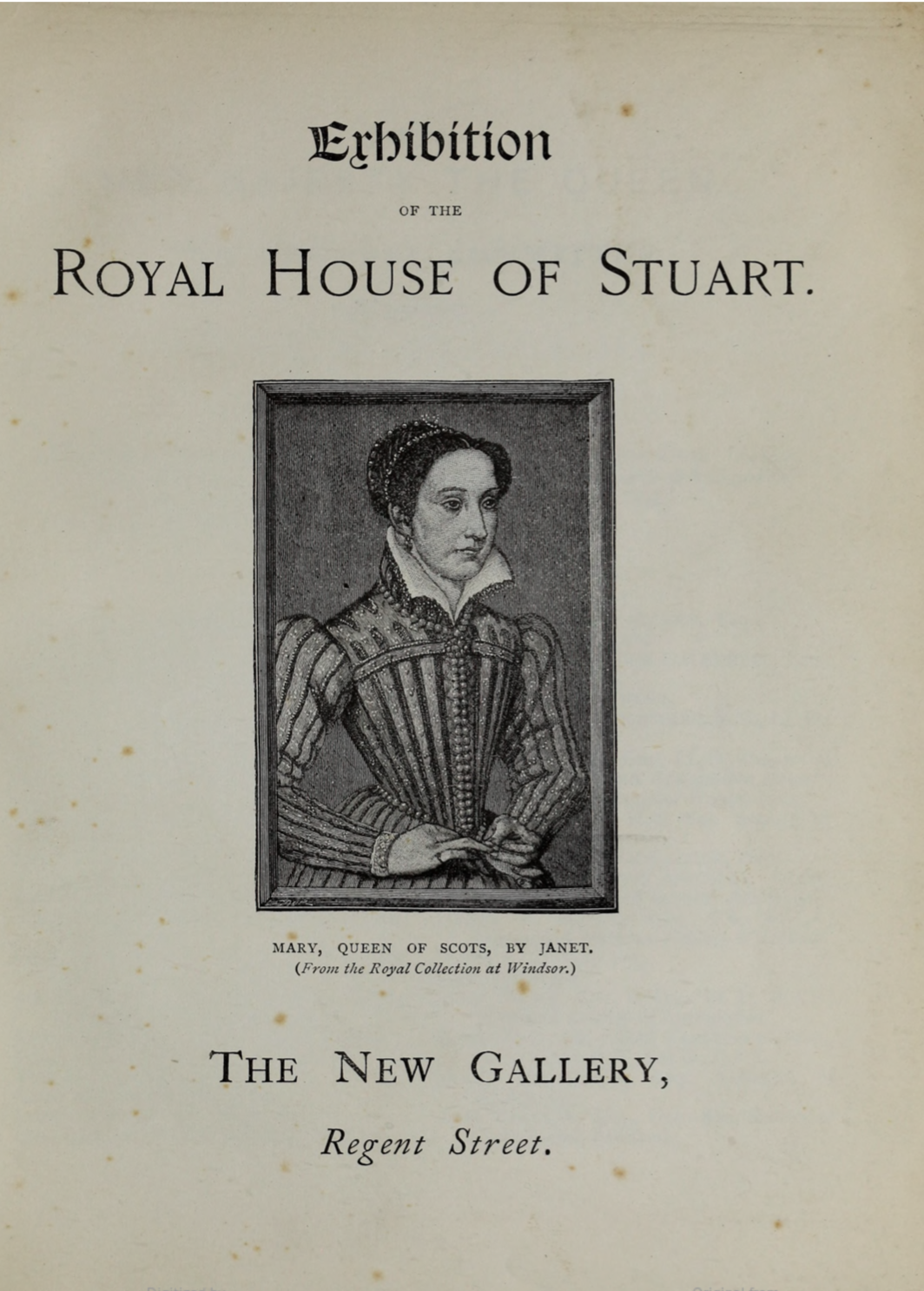

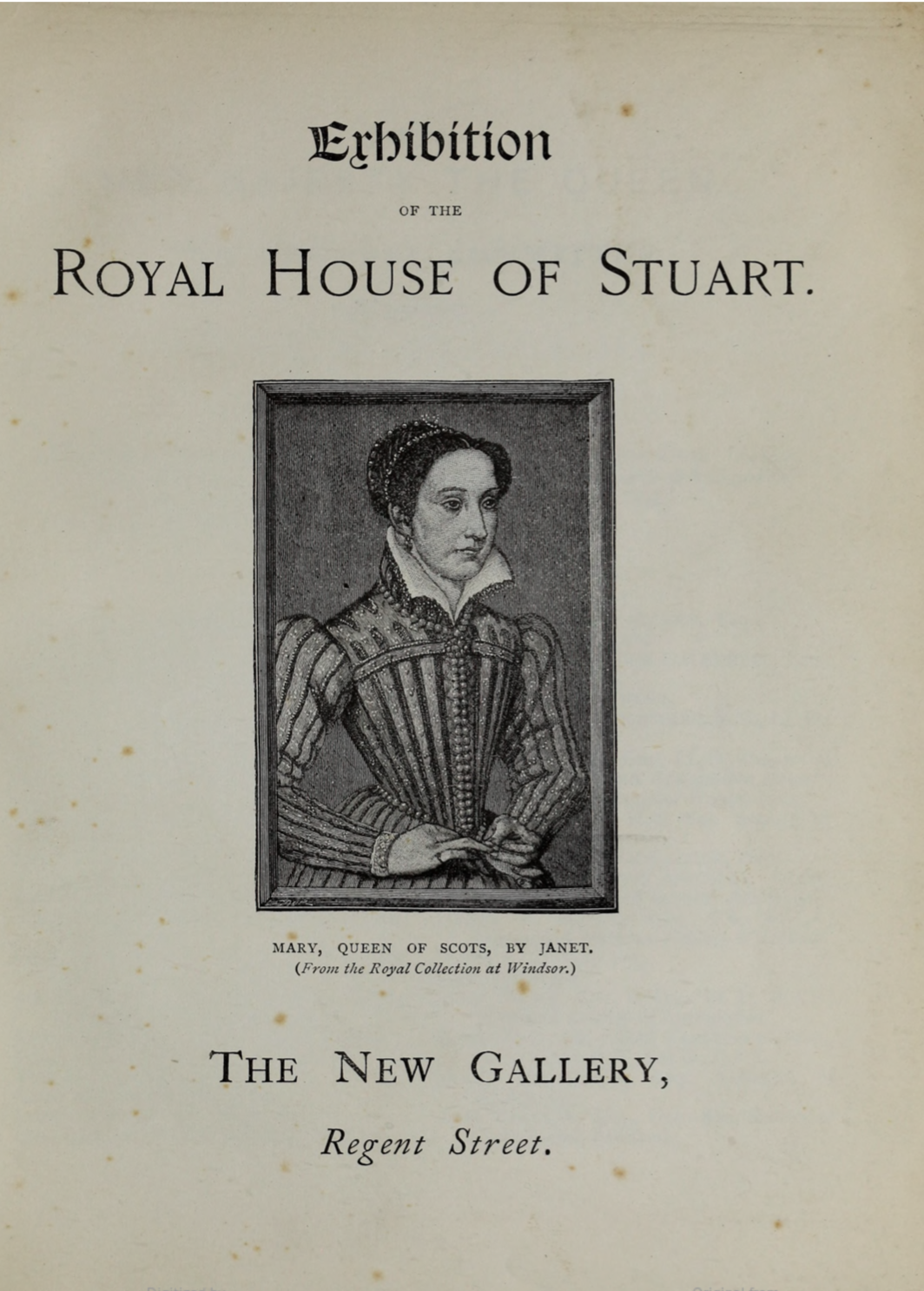

The Stuarts Exhibition

In 1889, the New Gallery in London put on a major exhibition of works related to the House of Stuart. Queen Victoria lent a number of items to the exhibition, as did the wife of her son

In 1889, the New Gallery in London put on a major exhibition of works related to the House of Stuart. Queen Victoria lent a number of items to the exhibition, as did the wife of her son Prince Leopold, Duke of Albany

Prince Leopold, Duke of Albany (Leopold George Duncan Albert; 7 April 185328 March 1884) was the eighth child and youngest son of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. Leopold was later created Duke of Albany, Earl of Clarence, and Baron Arklow. He ...

; Jacobite families from England and Scotland donated items. The exhibition was hugely popular and provoked a widespread new interest in the Stuart monarchs. The exhibition itself showed some distinctive Jacobite tendencies, as Guthrie points out in his book:It is clear that the point of the whole exhibition in the New Gallery ... was a Stuart restoration and to bring the Jacobite fact and the modern succession to the Stuart claim to the attention of the British public.However, the fact of Queen Victoria having actively contributed to the exhibition clearly indicates that she did not regard the Neo-Jacobites as significantly threatening her throne.

The Legitimist Jacobite League and other organizations

The new popularity sparked a renewed fervour for the Jacobite cause. In opposition to this, and coupled with the approaching tricentenary ofOliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English statesman, politician and soldier, widely regarded as one of the most important figures in British history. He came to prominence during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, initially ...

's birth in 1899, Cromwell also became a popular figure. Immediately following the exhibition, new Jacobite groups began to form. In 1890, Herbert Vivian

Herbert Vivian (3 April 1865 – 18 April 1940) was an English journalist, author and newspaper owner, who befriended Lord Randolph Churchill, Charles Russell, Baron Russell of Killowen, Charles Russell, Leopold Maxse and others in the 1880s. H ...

and Ruaraidh Erskine

Ruaraidh Erskine of Marr (15 January 1869 – 5 January 1960) (Scottish Gaelic: Ruaraidh Arascain is Mhàirr) was a Scottish nationalist political activist, writer and Scottish Gaelic language revival campaigner.

Early life

Ruaraidh Erskin ...

co-founded a weekly newspaper, '' The Whirlwind'', that espoused a Jacobite political view.

The Order of the White Rose split in 1891, when Vivian, Erskine and Melville Henry Massue

Melville Amadeus Henry Douglas Heddle de la Caillemotte de Massue de Ruvigny (26 April 1868 – 6 October 1921) was a British genealogist and author who was twice president of the Legitimist Jacobite League of Great Britain and Ireland. He styled ...

formed the Legitimist Jacobite League of Great Britain and Ireland

The Legitimist Jacobite League of Great Britain and Ireland was a Jacobite society founded in 1891 by Herbert Vivian, Melville Henry Massue and Ruaraidh Erskine following a split from the earlier Order of the White Rose. The League was conside ...

. Vivian and Massue were leading members of the neo-Jacobite revival, while Erskine soon focused his political endeavours on the related cause of Scottish Nationalism

Scottish nationalism promotes the idea that the Scottish people form a cohesive nation and Scottish national identity, national identity.

Scottish nationalism began to shape from 1853 with the National Association for the Vindication of Scottis ...

. The League was a "publicist for Jacobitism on a scale unwitnessed since the eighteenth century".

The Neo-Jacobites in the political arena

The continuing Order of the White Rose focused on a romantic ideal of a Jacobite past, expressed through the arts. Art dealer

The continuing Order of the White Rose focused on a romantic ideal of a Jacobite past, expressed through the arts. Art dealer Charles Augustus Howell

Charles Augustus Howell (10 March 1840 – 21 April 1890) was an art dealer and alleged blackmailer who is best known for persuading the poet Dante Gabriel Rossetti to dig up the poems he buried with his wife Elizabeth Siddal. His reputation as ...

and journalist Sebastian Evans were members of the Order, while poets W. B. Yeats

William Butler Yeats (, 13 June 186528 January 1939), popularly known as W. B. Yeats, was an Irish poet, dramatist, writer, and literary critic who was one of the foremost figures of 20th-century literature. He was a driving force behind the ...

and Andrew Lang

Andrew Lang (31 March 1844 – 20 July 1912) was a Scottish poet, novelist, literary critic, and contributor to the field of anthropology. He is best known as a folkloristics, collector of folklore, folk and fairy tales. The Andrew Lang lectur ...

were drawn to the cause.

The Legitimist Jacobite League was a decidedly more militant, political organisation. They organised a series of protests and events, often centred on statues of Jacobite heroes. In January 1893, the League attempted to lay a wreath at the statue of Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

at Charing Cross

Charing Cross ( ) is a junction in Westminster, London, England, where six routes meet. Since the early 19th century, Charing Cross has been the notional "centre of London" and became the point from which distances from London are measured. ...

, but were thwarted by a "considerable detachment of police" sent on the personal order of Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British politican, starting as Conservative MP for Newark and later becoming the leader of the Liberal Party (UK), Liberal Party.

In a career lasting over 60 years, he ...

.

They also found supporters within Parliament. In 1891, Irish Nationalist Sir John Pope Hennessy, MP for North Kilkenny, attempted to extend Gladstone's Bill to remove limitations on Catholics to cover the Royal Family. This was an outcome devoutly wished for by the Neo-Jacobites as a step towards the restoration of the Stuarts.

Jacobites started to stand as candidates for parliament. In 1891, artist Gilbert Baird Fraser stood, as did Vivian, as a candidate in East Bradford for the "Individualist Party" on a thoroughly Jacobite platform, and Walter Clifford Mellor (the son of John James Mellor MP), as a Jacobite in the North Huntingdonshire constituency. All three candidates lost. In 1895, Vivian stood in North Huntingdonshire as a Jacobite and lost again. In 1906, he was the Liberal candidate for Deptford

Deptford is an area on the south bank of the River Thames in southeast London, in the Royal Borough of Greenwich and London Borough of Lewisham. It is named after a Ford (crossing), ford of the River Ravensbourne. From the mid 16th century ...

and lost badly despite the support of his friend Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

. Finally, in 1907 he explored a candidacy in Stirling Burghs as a Legitimist; this time he withdrew before the election.

In Scotland, a number of Scottish Nationalists were drawn to the cause. Theodore Napier, the Scottish secretary of the Jacobite League, wrote a polemic titled "The Royal House of Stuart: A Plea for its Restoration. An Appeal to Loyal Scotsmen" in 1898, which was published by the Legitimist Jacobite League. It was one amongst a large number of publications put out by the League.

The end of the revival

The revival largely came to an end with the advent of theFirst World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

; by this time the heiress to the Jacobite claim was the elderly Queen of Bavaria and her son and heir-apparent, Crown Prince Rupprecht

Rupprecht, Crown Prince of Bavaria, Duke of Bavaria, Franconia and in Swabia, Count Palatine by the Rhine (''Rupprecht Maria Luitpold Ferdinand''; English: ''Rupert Maria Leopold Ferdinand''; 18 May 1869 – 2 August 1955), was the last heir ...

, was commanding German troops against the British on the Western Front. The various Neo-Jacobite societies are now represented by the Royal Stuart Society

The Royal Stuart Society, founded in 1926, is the largest extant Jacobite organisation in the United Kingdom. Its full name is The Royal Stuart Society and Royalist League, although it is best known simply as the "Royal Stuart Society". It acknow ...

, which acknowledges Francis, Duke of Bavaria as head of the House of Stuart, while refraining from making any claim on his behalf.

See also

*Whig history

Whig history (or Whig historiography) is an approach to historiography that presents history as a journey from an oppressive and benighted past to a "glorious present". The present described is generally one with modern forms of liberal democracy ...

References

{{Jacobitism Monarchism in the United Kingdom Political theories Social movements in the United Kingdom