Nazi Army on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified

The German Army was managed through mission-based tactics (rather than order-based tactics) which was intended to give commanders greater freedom to act on events and exploit opportunities. In public opinion, the German Army was, and sometimes still is, seen as a high-tech army. However, such modern equipment, while featured much in propaganda, was often only available in relatively small numbers. Only 40% to 60% of all units in the Eastern Front were motorized, baggage trains often relied on horse-drawn trailers due to poor roads and weather conditions in the Soviet Union, and for the same reasons many soldiers marched on foot or used bicycles as

The German Army was managed through mission-based tactics (rather than order-based tactics) which was intended to give commanders greater freedom to act on events and exploit opportunities. In public opinion, the German Army was, and sometimes still is, seen as a high-tech army. However, such modern equipment, while featured much in propaganda, was often only available in relatively small numbers. Only 40% to 60% of all units in the Eastern Front were motorized, baggage trains often relied on horse-drawn trailers due to poor roads and weather conditions in the Soviet Union, and for the same reasons many soldiers marched on foot or used bicycles as

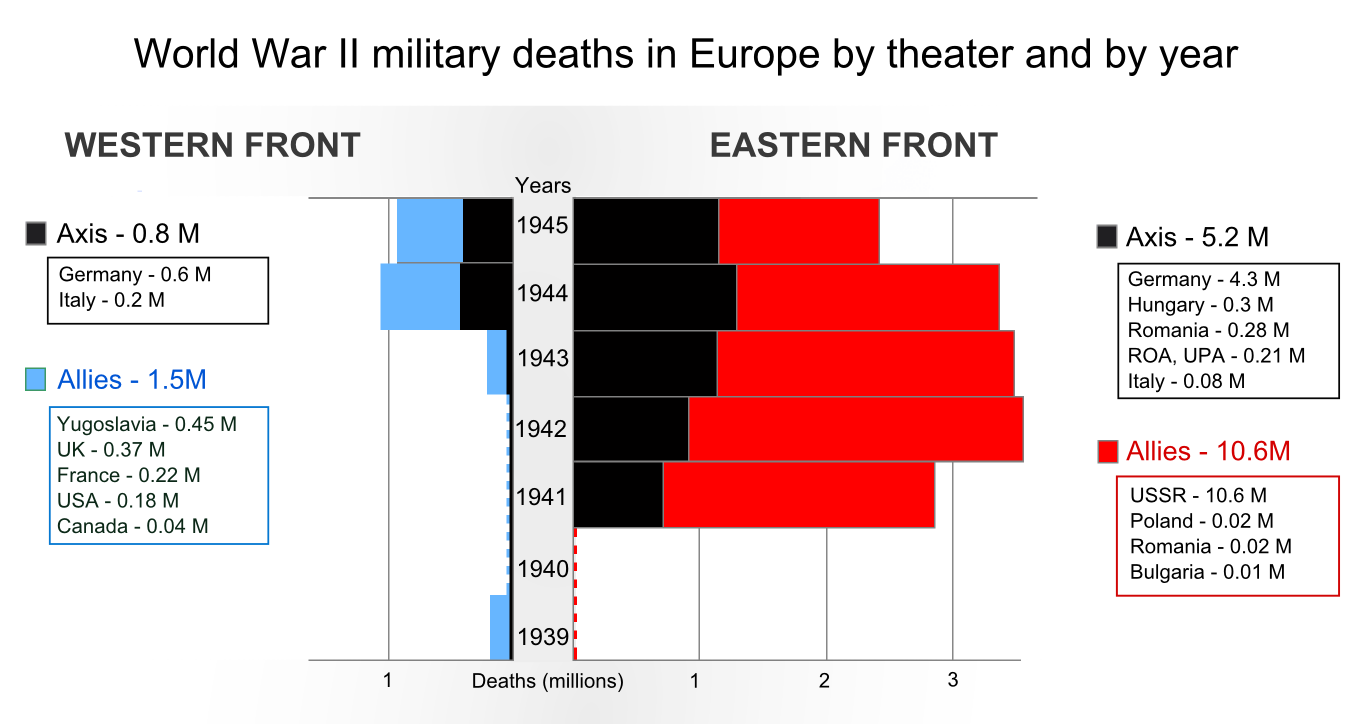

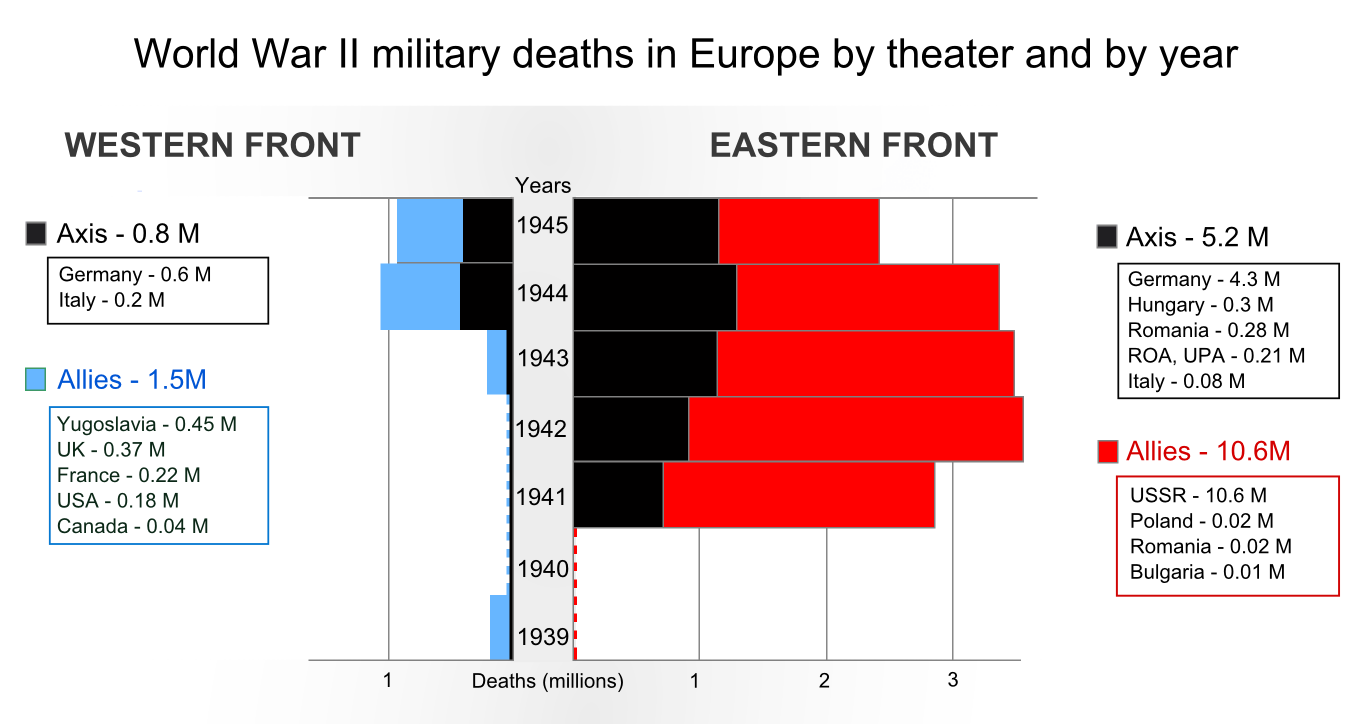

More than 6,000,000 soldiers were wounded during the conflict, while more than 11,000,000 became prisoners. In all, approximately 5,318,000 soldiers from Germany and other nationalities fighting for the German armed forces—including the ''Waffen-SS'', ''Volkssturm'' and foreign collaborationist units—are estimated to have been killed in action, died of wounds, died in custody or gone missing in World War II. Included in this number are 215,000 Soviet citizens conscripted by Germany.

According to Frank Biess,

More than 6,000,000 soldiers were wounded during the conflict, while more than 11,000,000 became prisoners. In all, approximately 5,318,000 soldiers from Germany and other nationalities fighting for the German armed forces—including the ''Waffen-SS'', ''Volkssturm'' and foreign collaborationist units—are estimated to have been killed in action, died of wounds, died in custody or gone missing in World War II. Included in this number are 215,000 Soviet citizens conscripted by Germany.

According to Frank Biess,

While the ''Wehrmacht''s prisoner-of-war camps for inmates from the west generally satisfied the humanitarian requirement prescribed by international law, prisoners from Poland and the USSR were incarcerated under significantly worse conditions. Between the launching of Operation Barbarossa in the summer of 1941 and the following spring, 2.8 million of the 3.2 million Soviet prisoners taken died while in German hands.

While the ''Wehrmacht''s prisoner-of-war camps for inmates from the west generally satisfied the humanitarian requirement prescribed by international law, prisoners from Poland and the USSR were incarcerated under significantly worse conditions. Between the launching of Operation Barbarossa in the summer of 1941 and the following spring, 2.8 million of the 3.2 million Soviet prisoners taken died while in German hands.

''The Wehrmacht: A Criminal Organization?''

Review of

''Wehrmacht Propaganda Troops and the Jews''

– an article by Daniel Uziel

The Nazi German Army 1935–1945

"A Blind Eye and Dirty Hands: The Wehrmacht's Crimes"

– lecture by the historian Geoffrey P. Megargee, via the YouTube channel of the

armed forces

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. Militaries are typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with their members identifiable by a ...

of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the ''Heer'' (army), the ''Kriegsmarine

The (, ) was the navy of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It superseded the Imperial German Navy of the German Empire (1871–1918) and the inter-war (1919–1935) of the Weimar Republic. The was one of three official military branch, branche ...

'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe

The Luftwaffe () was the aerial warfare, aerial-warfare branch of the before and during World War II. German Empire, Germany's military air arms during World War I, the of the Imperial German Army, Imperial Army and the of the Imperial Ge ...

'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmacht''" replaced the previously used term (''Reich Defence'') and was the manifestation of the Nazi regime's efforts to rearm Germany to a greater extent than the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles was a peace treaty signed on 28 June 1919. As the most important treaty of World War I, it ended the state of war between Germany and most of the Allies of World War I, Allied Powers. It was signed in the Palace ...

permitted.

After the Nazi rise to power in 1933, one of Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

's most overt and bellicose moves was to establish the ''Wehrmacht'', a modern offensively-capable armed force, fulfilling the Nazi regime's long-term goals of regaining lost territory as well as gaining new territory and dominating its neighbours. This required the reinstatement of conscription and massive investment and defence spending on the arms industry.

The ''Wehrmacht'' formed the heart of Germany's politico-military power. In the early part of the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, the ''Wehrmacht'' employed combined arms

Combined arms is an approach to warfare that seeks to integrate different combat arms of a military to achieve mutually complementary effects—for example, using infantry and armoured warfare, armour in an Urban warfare, urban environment in ...

tactics (close-cover air-support, tanks and infantry) to devastating effect in what became known as ''Blitzkrieg

''Blitzkrieg'(Lightning/Flash Warfare)'' is a word used to describe a combined arms surprise attack, using a rapid, overwhelming force concentration that may consist of armored and motorized or mechanized infantry formations, together with ...

'' (lightning war). Its campaigns in France (1940), the Soviet Union (1941) and North Africa (1941/42) are regarded by historians as acts of boldness. At the same time, the extent of advances strained the ''Wehrmacht's'' capacity to the breaking point, culminating in its first major defeat in the Battle of Moscow

The Battle of Moscow was a military campaign that consisted of two periods of strategically significant fighting on a sector of the Eastern Front during World War II, between October 1941 and January 1942. The Soviet defensive effort frustrated H ...

(1941); by late 1942, Germany was losing the initiative in all theatres. The German operational art

In the field of military theory, the operational level of war (also called operational art, as derived from , or operational warfare) represents the level of command that connects the details of tactics with the goals of strategy.

In U.S. J ...

proved no match to that of the Allied coalition, making the ''Wehrmacht's'' weaknesses in strategy, doctrine, and logistics apparent.

Closely cooperating with the ''SS'' and their death squads, the German armed forces committed numerous war crimes

A war crime is a violation of the laws of war that gives rise to individual criminal responsibility for actions by combatants in action, such as intentionally killing civilians or intentionally killing prisoners of war, torture, taking hos ...

(despite later denials and promotion of the myth of the clean ''Wehrmacht''). The majority of the war crimes took place in the Soviet Union, Poland, Yugoslavia, Greece, and Italy, as part of the war of annihilation

A war of annihilation () or war of extermination is a type of war in which the goal is the complete annihilation of a state, a people or an ethnic minority through genocide or through the destruction of their livelihood. The goal can be outwar ...

against the Soviet Union, the Holocaust

The Holocaust (), known in Hebrew language, Hebrew as the (), was the genocide of History of the Jews in Europe, European Jews during World War II. From 1941 to 1945, Nazi Germany and Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy ...

and Nazi security warfare

Nazism (), formally named National Socialism (NS; , ), is the far-right totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During Hitler's rise to power, it was frequen ...

.

During World War II about 18 million men served in the ''Wehrmacht''. By the time the war ended in Europe in May 1945, German forces (consisting of the ''Heer'', the ''Kriegsmarine'', the ''Luftwaffe'', the ''Waffen-SS

The (; ) was the military branch, combat branch of the Nazi Party's paramilitary ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS) organisation. Its formations included men from Nazi Germany, along with Waffen-SS foreign volunteers and conscripts, volunteers and conscr ...

'', the ''Volkssturm

The (, ) was a ''levée en masse'' national militia established by Nazi Germany during the last months of World War II. It was set up by the Nazi Party on the orders of Adolf Hitler and established on 25 September 1944. It was staffed by conscri ...

'', and foreign collaborator units) had lost approximately 11,300,000 men, about 5,318,000 of whom were missing, killed or died in captivity. Only a few of the ''Wehrmacht''s upper leadership went on trial for war crimes, despite evidence suggesting that more were involved in illegal actions. According to Ian Kershaw

Sir Ian Kershaw (born 29 April 1943) is an English historian whose work has chiefly focused on the social history of 20th-century Germany. He is regarded by many as one of the world's foremost experts on Adolf Hitler and Nazi Germany, and is ...

, most of the three million ''Wehrmacht'' soldiers who invaded the USSR participated in war crimes.

Origin

Etymology

The German term ''"Wehrmacht''" stems from the compound word of , "to defend" and , "power, force". It has been used to describe any nation's armed forces; for example, meaning "British Armed Forces". TheFrankfurt Constitution

The Frankfurt Constitution () or Constitution of St. Paul's Church (), officially named the Constitution of the German Empire () of 28 March 1849, was an unsuccessful attempt to create a unified German nation from the states of the German Confe ...

of 1849 designated all German military forces as the "German ''Wehrmacht''", consisting of the (sea force) and the (land force). In 1919, the term ''Wehrmacht'' also appears in Article 47 of the Weimar Constitution

The Constitution of the German Reich (), usually known as the Weimar Constitution (), was the constitution that governed Germany during the Weimar Republic era. The constitution created a federal semi-presidential republic with a parliament whose ...

, establishing that: "The Reich's President holds supreme command of all armed forces .e. the ''Wehrmacht''of the Reich". From 1919, Germany's national defense force was known as the , a name that was dropped in favor of ''Wehrmacht'' on 21 May 1935.

While the term ''Wehrmacht'' has been associated, both in the German and English languages, with the German armed forces of 1933–45 since the Second World War, before 1945 the term was used in the German language in a more general sense for a national defense force. For instance, the German-aligned formations of Poles raised during the First World War were known as the '' Polnische Wehrmacht'' ('Polish Wehrmacht', 'Polish Defense Force') in German.

Background

In January 1919, afterWorld War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

ended with the signing of the armistice of 11 November 1918

The Armistice of 11 November 1918 was the armistice signed in a railroad car, in the Compiègne Forest near the town of Compiègne, that ended fighting on land, at sea, and in the air in World War I between the Entente and their las ...

, the armed forces were dubbed (peace army). In March 1919, the national assembly passed a law founding a 420,000-strong preliminary army, the . The terms of the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles was a peace treaty signed on 28 June 1919. As the most important treaty of World War I, it ended the state of war between Germany and most of the Allies of World War I, Allied Powers. It was signed in the Palace ...

were announced in May, and in June, Germany signed the treaty that, among other terms, imposed severe constraints on the size of Germany's armed forces. The army was limited to one hundred thousand men with an additional fifteen thousand in the navy. The fleet was to consist of at most six battleship

A battleship is a large, heavily naval armour, armored warship with a main battery consisting of large naval gun, guns, designed to serve as a capital ship. From their advent in the late 1880s, battleships were among the largest and most form ...

s, six cruiser

A cruiser is a type of warship. Modern cruisers are generally the largest ships in a fleet after aircraft carriers and amphibious assault ships, and can usually perform several operational roles from search-and-destroy to ocean escort to sea ...

s, and twelve destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, maneuverable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy, or carrier battle group and defend them against a wide range of general threats. They were conceived i ...

s. Submarine

A submarine (often shortened to sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. (It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability.) The term "submarine" is also sometimes used historically or infor ...

s, tank

A tank is an armoured fighting vehicle intended as a primary offensive weapon in front-line ground combat. Tank designs are a balance of heavy firepower, strong armour, and battlefield mobility provided by tracks and a powerful engine; ...

s and heavy artillery

Artillery consists of ranged weapons that launch Ammunition, munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during sieges, and l ...

were forbidden and the air-force was dissolved. A new post-war military, the ''Reichswehr

''Reichswehr'' (; ) was the official name of the German armed forces during the Weimar Republic and the first two years of Nazi Germany. After Germany was defeated in World War I, the Imperial German Army () was dissolved in order to be reshaped ...

'', was established on 23 March 1921. General conscription was abolished under another mandate of the Versailles treaty.

The ''Reichswehr'' was limited to 115,000 men, and thus the armed forces, under the leadership of Hans von Seeckt

Johannes "Hans" Friedrich Leopold von Seeckt (22 April 1866 – 27 December 1936) was a German military officer who served as Chief of Staff to August von Mackensen and was a central figure in planning the victories Mackensen achieved for German ...

, retained only the most capable officers. The American historians Alan Millet and Williamson Murray

Williamson "Wick" Murray (November 23, 1941 – August 1, 2023) was an American historian and author. He authored numerous works on history and strategic studies, and served as an editor on other projects extensively. He was professor emeritus o ...

wrote "In reducing the officers corps, Seeckt chose the new leadership from the best men of the general staff with ruthless disregard for other constituencies, such as war heroes and the nobility." Seeckt's determination that the ''Reichswehr'' be an elite cadre force that would serve as the nucleus of an expanded military when the chance for restoring conscription came essentially led to the creation of a new army, based upon, but very different from, the army that existed in World War I. In the 1920s, Seeckt and his officers developed new doctrines that emphasized speed, aggression, combined arms and initiative on the part of lower officers to take advantage of momentary opportunities. Though Seeckt retired in 1926, his influence on the army was still apparent when it went to war in 1939.

Germany was forbidden to have an air force by the Versailles treaty; nonetheless, Seeckt created a clandestine cadre of air force officers in the early 1920s. These officers saw the role of an air force as winning air superiority, strategic bombing, and close air support. That the ''Luftwaffe'' did not develop a strategic bombing force in the 1930s was not due to a lack of interest, but because of economic limitations. The leadership of the Navy led by Grand Admiral Erich Raeder

Erich Johann Albert Raeder (24 April 1876 – 6 November 1960) was a German admiral who played a major role in the naval history of World War II and was convicted of war crimes after the war. He attained the highest possible naval rank, that of ...

, a close protégé of Alfred von Tirpitz

Alfred Peter Friedrich von Tirpitz (; born Alfred Peter Friedrich Tirpitz; 19 March 1849 – 6 March 1930) was a German grand admiral and State Secretary of the German Imperial Naval Office, the powerful administrative branch of the German Imperi ...

, was dedicated to the idea of reviving Tirpitz's High Seas Fleet. Officers who believed in submarine warfare led by Admiral Karl Dönitz

Karl Dönitz (; 16 September 1891 – 24 December 1980) was a German grand admiral and convicted war criminal who, following Adolf Hitler's Death of Adolf Hitler, suicide, succeeded him as head of state of Nazi Germany during the Second World ...

were in a minority before 1939.

By 1922, Germany had begun covertly circumventing the conditions of the Versailles treaty. A secret collaboration with the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

began after the Treaty of Rapallo Following World War I there were two Treaties of Rapallo, both named after Rapallo, a resort on the Ligurian coast of Italy:

* Treaty of Rapallo, 1920, an agreement between Italy and the Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (the later Yugoslav ...

. Major-General Otto Hasse traveled to Moscow in 1923 to further negotiate the terms. Germany helped the Soviet Union with industrialization and Soviet officers were to be trained in Germany. German tank and air-force specialists could exercise in the Soviet Union and German chemical weapons research and manufacture would be carried out there along with other projects. In 1924 a fighter-pilot school was established at Lipetsk

Lipetsk (, ), also Romanization of Russian, romanized as Lipeck, is a types of inhabited localities in Russia, city and the administrative center of Lipetsk Oblast, Russia, located on the banks of the Voronezh (river), Voronezh River in the Do ...

, where several hundred German air force personnel received instruction in operational maintenance, navigation, and aerial combat training over the next decade until the Germans finally left in September 1933. However, the arms buildup was done in secrecy, until Hitler came to power and it received broad political support.

Nazi rise to power

After the death of PresidentPaul von Hindenburg

Paul Ludwig Hans Anton von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg (2 October 1847 – 2 August 1934) was a German military and political leader who led the Imperial German Army during the First World War and later became President of Germany (1919� ...

on 2 August 1934, Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

assumed the office of President of Germany

The president of Germany, officially titled the Federal President of the Federal Republic of Germany (),The official title within Germany is ', with ' being added in international correspondence; the official English title is President of the F ...

, and thus became commander in chief. In February 1934, the Defence Minister Werner von Blomberg

Werner Eduard Fritz von Blomberg (2 September 1878 – 13 March 1946) was a German general and politician who served as the first Minister of War in Nazi Germany from 1933 to 1938. Blomberg had served as Chief of the ''Truppenamt'', equivalent ...

, acting on his own initiative, had all of the Jews serving in the ''Reichswehr'' given an automatic and immediate dishonorable discharge

A military discharge is given when a member of the armed forces is released from their obligation to serve. Each country's military has different types of discharge. They are generally based on whether the persons completed their training and the ...

. Again, on his own initiative Blomberg had the armed forces adopt Nazi symbols into their uniforms in May 1934. In August of the same year, on Blomberg's initiative and that of the ''Ministeramt'' chief General Walther von Reichenau

Walter Karl Gustav August Ernst von Reichenau (8 October 1884 – 17 January 1942) was a German Generalfeldmarschall (Field Marshal) in the '' Heer'' (Army) of Nazi Germany during World War II. He was nicknamed "The Bull" ( German: ''Der Bulle) ...

, the entire military took the Hitler oath

The Hitler Oath (German: or ''Führer'' Oath)—also referred in English as the Soldier's Oath—refers to the oaths of allegiance sworn by officers and soldiers of the ''Wehrmacht'' and civil servants of Nazi Germany between the years 1934 and ...

, an oath of personal loyalty to Hitler. Hitler was most surprised at the offer; the popular view that Hitler imposed the oath on the military is false. The oath read: "I swear by God this sacred oath that to the Leader of the German empire and people, Adolf Hitler, supreme commander of the armed forces, I shall render unconditional obedience

Corpse-like obedience (, also translated as corpse obedience, cadaver obedience, cadaver-like obedience, zombie-like obedience, slavish obedience, unquestioning obedience, absolute obedience or blind obedience) refers to an obedience in which the ...

and that as a brave soldier I shall at all times be prepared to give my life for this oath".

By 1935, Germany was openly flouting the military restrictions set forth in the Versailles Treaty: German rearmament

German rearmament (''Aufrüstung'', ) was a policy and practice of rearmament carried out by Germany from 1918 to 1939 in violation of the Treaty of Versailles, which required German disarmament after World War I to prevent it from starting an ...

was announced on 16 March with the "Edict for the Buildup of the ''Wehrmacht''" () and the reintroduction of conscription. While the size of the standing army was to remain at about the 100,000-man mark decreed by the treaty, a new group of conscripts equal to this size would receive training each year. The conscription law introduced the name "''Wehrmacht''"; the ''Reichswehr'' was officially renamed the ''Wehrmacht'' on 21 May 1935. Hitler's proclamation of the ''Wehrmacht''s existence included a total of no less than 36 divisions in its original projection, contravening the Treaty of Versailles in grandiose fashion. In December 1935, General Ludwig Beck

Ludwig August Theodor Beck (; 29 June 1880 – 20 July 1944) was a German general who served as Chief of the German General Staff from 1933 to 1938. Beck was one of the main conspirators of the 20 July plot to assassinate Adolf Hitler.

...

added 48 tank battalions to the planned rearmament program. Hitler originally set a time frame of 10 years for remilitarization, but soon shortened it to four years. With the remilitarization of the Rhineland

The remilitarisation of the Rhineland (, ) began on 7 March 1936, when military forces of Nazi Germany entered the Rhineland, which directly contravened the Treaty of Versailles and the Locarno Treaties. Neither France nor Britain was prepared f ...

and the ''Anschluss

The (, or , ), also known as the (, ), was the annexation of the Federal State of Austria into Nazi Germany on 12 March 1938.

The idea of an (a united Austria and Germany that would form a "German Question, Greater Germany") arose after t ...

'', the German Reich's territory increased significantly, providing a larger population pool for conscription.

Personnel and recruitment

Recruitment for the ''Wehrmacht'' was accomplished through voluntary enlistment and conscription, with 1.3 million being drafted and 2.4 million volunteering in the period 1935–1939. The total number of soldiers who served in the ''Wehrmacht'' during its existence from 1935 to 1945 is believed to have approached 18.2 million. The German military leadership originally aimed at a homogeneous military, possessing traditional Prussian military values. However, with Hitler's constant wishes to increase the ''Wehrmacht''s size, the Army was forced to accept citizens of lower class and education, decreasing internal cohesion and appointing officers who lacked real-war experience from previous conflicts, especiallyWorld War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

and the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War () was a military conflict fought from 1936 to 1939 between the Republican faction (Spanish Civil War), Republicans and the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalists. Republicans were loyal to the Left-wing p ...

.

The effectiveness of officer training and recruitment by the ''Wehrmacht'' has been identified as a major factor in its early victories as well as its ability to keep the war going as long as it did even as the war turned against Germany.

As the Second World War intensified, ''Kriegsmarine

The (, ) was the navy of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It superseded the Imperial German Navy of the German Empire (1871–1918) and the inter-war (1919–1935) of the Weimar Republic. The was one of three official military branch, branche ...

'' and ''Luftwaffe

The Luftwaffe () was the aerial warfare, aerial-warfare branch of the before and during World War II. German Empire, Germany's military air arms during World War I, the of the Imperial German Army, Imperial Army and the of the Imperial Ge ...

'' personnel were increasingly transferred to the army, and "voluntary" enlistments in the ''SS'' were stepped up as well. Following the Battle of Stalingrad

The Battle of Stalingrad ; see . rus, links=on, Сталинградская битва, r=Stalingradskaya bitva, p=stəlʲɪnˈɡratskəjə ˈbʲitvə. (17 July 19422 February 1943) was a major battle on the Eastern Front of World War II, ...

in 1943, fitness and physical health standards for ''Wehrmacht'' recruits were drastically lowered, with the regime going so far as to create "special diet" battalions for men with severe stomach ailments. Rear-echelon personnel were more often sent to front-line duty wherever possible, especially during the final two years of the war where, inspired by constant propaganda, the oldest and youngest were being recruited and driven by instilled fear and fanaticism to serve on the fronts and, often, to fight to the death, whether judged to be cannon fodder or elite troops.

Prior to World War II, the ''Wehrmacht'' strove to remain a purely ethnic German force; as such, minorities within and outside of Germany, such as the Czechs in annexed Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia ( ; Czech language, Czech and , ''Česko-Slovensko'') was a landlocked country in Central Europe, created in 1918, when it declared its independence from Austria-Hungary. In 1938, after the Munich Agreement, the Sudetenland beca ...

, were exempted from military service after Hitler's takeover in 1938. Foreign volunteers were generally not accepted in the German armed forces prior to 1941. With the invasion of the Soviet Union

Operation Barbarossa was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and several of its European Axis allies starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during World War II. More than 3.8 million Axis troops invaded the western Soviet Union along a ...

in 1941, the government's positions changed. German propagandists wanted to present the war not as a purely German concern, but as a multi-national crusade

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and at times directed by the Papacy during the Middle Ages. The most prominent of these were the campaigns to the Holy Land aimed at reclaiming Jerusalem and its surrounding t ...

against the so-called Jewish Bolshevism

Jewish Bolshevism, also Judeo–Bolshevism, is an antisemitic and anti-communist conspiracy theory that claims that the Russian Revolution of 1917 was a Jewish plot and that Jews controlled the Soviet Union and international communist moveme ...

. Hence, the ''Wehrmacht'' and the ''SS'' began to seek out recruits from occupied and neutral countries across Europe: the Germanic populations of the Netherlands and Norway were recruited largely into the ''SS'', while "non-Germanic" people were recruited into the ''Wehrmacht''. The "voluntary" nature of such recruitment was often dubious, especially in the later years of the war when even Poles living in the Polish Corridor

The Polish Corridor (; ), also known as the Pomeranian Corridor, was a territory located in the region of Pomerelia (Pomeranian Voivodeship, Eastern Pomerania), which provided the Second Polish Republic with access to the Baltic Sea, thus d ...

were declared "ethnic Germans" and drafted.

After Germany's defeat in the Battle of Stalingrad

The Battle of Stalingrad ; see . rus, links=on, Сталинградская битва, r=Stalingradskaya bitva, p=stəlʲɪnˈɡratskəjə ˈbʲitvə. (17 July 19422 February 1943) was a major battle on the Eastern Front of World War II, ...

, the ''Wehrmacht'' also made substantial use of personnel from the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

, including the Caucasian Muslim Legion, Turkestan Legion

The Turkestan Legion () was the name of the military units composed of Turkic peoples who served in the ''Wehrmacht'' during World War II. Most of these troops were Red Army prisoners of war who formed a common cause with the Germans (cf. Turkic ...

, Crimean Tatars, ethnic Ukrainians and Russians, Cossack

The Cossacks are a predominantly East Slavic Eastern Christian people originating in the Pontic–Caspian steppe of eastern Ukraine and southern Russia. Cossacks played an important role in defending the southern borders of Ukraine and Rus ...

s, and others who wished to fight against the Soviet regime or who were otherwise induced to join. Between 15,000 and 20,000 anti-communist White émigrés

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no chroma). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully (or almost fully) reflect and scatter all the visible wavelen ...

who had left Russia after the Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of Political revolution (Trotskyism), political and social revolution, social change in Russian Empire, Russia, starting in 1917. This period saw Russia Dissolution of the Russian Empire, abolish its mona ...

joined the ranks of the ''Wehrmacht'' and ''Waffen-SS'', with 1,500 acting as interpreters

Interpreting is translation from a spoken or signed language into another language, usually in real time to facilitate live communication. It is distinguished from the translation of a written text, which can be more deliberative and make use o ...

and more than 10,000 serving in the guard force of the Russian Protective Corps.

Women in the ''Wehrmacht''

In the beginning, women in Nazi Germany were not involved in the ''Wehrmacht'', as Hitler ideologically opposed conscription for women, stating that Germany would "''not form any section of women grenade throwers or any corps of women elite snipers.''" However, with many men going to the front, women were placed in auxiliary positions within the ''Wehrmacht'', called ''Wehrmachtshelferinnen'' (), participating in tasks as: * telephone, telegraph and transmission operators, * administrative clerks, typists and messengers, * operators of listening equipment, in anti-aircraft defense, operating projectors for anti-aircraft defense, employees withinmeteorology

Meteorology is the scientific study of the Earth's atmosphere and short-term atmospheric phenomena (i.e. weather), with a focus on weather forecasting. It has applications in the military, aviation, energy production, transport, agricultur ...

services, and auxiliary civil defense personnel

* volunteer nurses in military health service, as the German Red Cross

The German Red Cross (GRC) ( ; DRK) is the national Red Cross Society in Germany.

During the Nazi era, the German Red Cross was under the control of the Nazi Party and played a role in supporting the regime's policies, including the exclusion ...

or other voluntary organizations.

They were placed under the same authority as ( Hiwis), auxiliary personnel of the army () and they were assigned to duties within the Reich, and to a lesser extent, in the occupied territories, for example in the general government of occupied Poland, in France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

, and later in Yugoslavia

, common_name = Yugoslavia

, life_span = 1918–19921941–1945: World War II in Yugoslavia#Axis invasion and dismemberment of Yugoslavia, Axis occupation

, p1 = Kingdom of SerbiaSerbia

, flag_p ...

, in Greece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

and in Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to ...

.

By 1945, 500,000 women were serving as ''Wehrmachtshelferinnen'', half of whom were volunteers, while the other half performed obligatory services connected to the war effort ().

Command structure

Legally, the commander-in-chief of the ''Wehrmacht'' was Adolf Hitler in his capacity as Germany's head of state, a position he gained after the death of PresidentPaul von Hindenburg

Paul Ludwig Hans Anton von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg (2 October 1847 – 2 August 1934) was a German military and political leader who led the Imperial German Army during the First World War and later became President of Germany (1919� ...

in August 1934. With the creation of the ''Wehrmacht'' in 1935, Hitler elevated himself to Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces, retaining the position until his suicide on 30 April 1945. The title of Commander-in-Chief was given to the Minister of the ''Reichswehr'' Werner von Blomberg

Werner Eduard Fritz von Blomberg (2 September 1878 – 13 March 1946) was a German general and politician who served as the first Minister of War in Nazi Germany from 1933 to 1938. Blomberg had served as Chief of the ''Truppenamt'', equivalent ...

, who was simultaneously renamed the Reich Minister of War. Following the Blomberg-Fritsch Affair, Blomberg resigned and Hitler abolished the Ministry of War. As a replacement for the ministry, the ''Wehrmacht'' High Command ''Oberkommando der Wehrmacht

The (; abbreviated OKW

'' (OKW), under Field Marshal ː kaːˈve

The colon alphabetic letter is used in a number of languages and phonetic transcription systems, for vowel length in Americanist Phonetic Notation, for the vowels and in a number of languages of Papua New Guinea, and for grammatical tone in s ...

Armed Forces High Command) was the Command (military formation), supreme military command and control Staff (military), staff of Nazi Germany during World War II, that was directly subordinated to Adolf ...Wilhelm Keitel

Wilhelm Bodewin Johann Gustav Keitel (; 22 September 188216 October 1946) was a German field marshal who held office as chief of the (OKW), the high command of Nazi Germany's armed forces, during World War II. He signed a number of criminal ...

, was put in its place.

Placed under the OKW were the three branch High Commands: ''Oberkommando des Heeres

The (; abbreviated OKH) was the high command of the Army of Nazi Germany. It was founded in 1935 as part of Adolf Hitler's rearmament of Germany. OKH was ''de facto'' the most important unit within the German war planning until the defeat ...

'' (OKH), ''Oberkommando der Marine

The (; abbreviated OKM) was the high command and the highest administrative and command authority of the ''Kriegsmarine'', a branch of the ''Wehrmacht''. It was officially formed from the ''Marineleitung'' ("Naval Command") of the ''Reichswe ...

'' (OKM), and ''Oberkommando der Luftwaffe

The (; abbreviated OKL) was the high command of the air force () of Nazi Germany.

History

The was organized in a large and diverse structure led by Reich minister and supreme commander of the Air force () Hermann Göring. Through the Mini ...

'' (OKL). The OKW was intended to serve as a joint command and coordinate all military activities, with Hitler at the top. Though many senior officers, such as von Manstein, had advocated for a real tri-service Joint Command, or appointment of a single Joint Chief of Staff, Hitler refused. Even after the defeat at Stalingrad, Hitler refused, stating that Göring as ''Reichsmarschall

(; ) was an honorary military rank, specially created for Hermann Göring during World War II, and the highest rank in the . It was senior to the rank of (, equivalent to field marshal, which was previously the highest rank in the ), but ...

'' and Hitler's deputy, would not submit to someone else or see himself as an equal to other service commanders. However, a more likely reason was Hitler feared it would break his image of having the "Midas touch" concerning military strategy.

With the creation of the OKW, Hitler solidified his control over the ''Wehrmacht''. Showing restraint at the beginning of the war, Hitler also became increasingly involved in military operations at every scale.

Additionally, there was a clear lack of cohesion between the three High Commands and the OKW, as senior generals were unaware of the needs, capabilities and limitations of the other branches. With Hitler serving as Supreme Commander, branch commands were often forced to fight for influence with Hitler. However, influence with Hitler not only came from rank and merit but also who Hitler perceived as loyal, leading to inter-service rivalry, rather than cohesion between his military advisers.

Branches

Army

The German Army furthered concepts pioneered duringWorld War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, combining ground (''Heer'') and air force (''Luftwaffe'') assets into combined arms

Combined arms is an approach to warfare that seeks to integrate different combat arms of a military to achieve mutually complementary effects—for example, using infantry and armoured warfare, armour in an Urban warfare, urban environment in ...

teams. Coupled with traditional war fighting methods such as encirclement

Encirclement is a military term for the situation when a force or target is isolated and surrounded by enemy forces. The situation is highly dangerous for the encircled force. At the military strategy, strategic level, it cannot receive Milit ...

s and the "battle of annihilation

Annihilation is a military strategy in which an attacking army seeks to entirely destroy the military capacity of the opposing army. This strategy can be executed in a single planned pivotal battle, called a "battle of annihilation". A succ ...

", the ''Wehrmacht'' managed many lightning quick victories in the first year of World War II, prompting foreign journalists to create a new word for what they witnessed: ''Blitzkrieg

''Blitzkrieg'(Lightning/Flash Warfare)'' is a word used to describe a combined arms surprise attack, using a rapid, overwhelming force concentration that may consist of armored and motorized or mechanized infantry formations, together with ...

''. Germany's immediate military success on the field at the start of the Second World War coincides the favorable beginning they achieved during the First World War, a fact which some attribute to their superior officer corps.

The ''Heer'' entered the war with a minority of its formations motorized; infantry remained approximately 90% foot-borne throughout the war, and artillery was primarily horse-drawn. The motorized formations received much attention in the world press in the opening years of the war, and were cited as the reason for the success of the invasions of Poland (September 1939), Denmark and Norway (April 1940), Belgium, France, and Netherlands (May 1940), Yugoslavia and Greece (April 1941) and the early stage of Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and several of its European Axis allies starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during World War II. More than 3.8 million Axis troops invaded the western Soviet Union along ...

in the Soviet Union (June 1941).

After Hitler declared war on the United States in December 1941, the Axis powers

The Axis powers, originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis and also Rome–Berlin–Tokyo Axis, was the military coalition which initiated World War II and fought against the Allies of World War II, Allies. Its principal members were Nazi Ge ...

found themselves engaged in campaigns against several major industrial powers while Germany was still in transition to a war economy. German units were then overextended, undersupplied, outmaneuvered, outnumbered and defeated by its enemies in decisive battles during 1941, 1942, and 1943 at the Battle of Moscow

The Battle of Moscow was a military campaign that consisted of two periods of strategically significant fighting on a sector of the Eastern Front during World War II, between October 1941 and January 1942. The Soviet defensive effort frustrated H ...

, the Siege of Leningrad

The siege of Leningrad was a Siege, military blockade undertaken by the Axis powers against the city of Leningrad (present-day Saint Petersburg) in the Soviet Union on the Eastern Front (World War II), Eastern Front of World War II from 1941 t ...

, Stalingrad

Volgograd,. geographical renaming, formerly Tsaritsyn. (1589–1925) and Stalingrad. (1925–1961), is the largest city and the administrative centre of Volgograd Oblast, Russia. The city lies on the western bank of the Volga, covering an area o ...

, Tunis

Tunis (, ') is the capital city, capital and largest city of Tunisia. The greater metropolitan area of Tunis, often referred to as "Grand Tunis", has about 2,700,000 inhabitants. , it is the third-largest city in the Maghreb region (after Casabl ...

in North Africa

North Africa (sometimes Northern Africa) is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region. However, it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of t ...

, and the Battle of Kursk

The Battle of Kursk, also called the Battle of the Kursk Salient, was a major World War II Eastern Front battle between the forces of Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union near Kursk in southwestern Russia during the summer of 1943, resulting in ...

.

The German Army was managed through mission-based tactics (rather than order-based tactics) which was intended to give commanders greater freedom to act on events and exploit opportunities. In public opinion, the German Army was, and sometimes still is, seen as a high-tech army. However, such modern equipment, while featured much in propaganda, was often only available in relatively small numbers. Only 40% to 60% of all units in the Eastern Front were motorized, baggage trains often relied on horse-drawn trailers due to poor roads and weather conditions in the Soviet Union, and for the same reasons many soldiers marched on foot or used bicycles as

The German Army was managed through mission-based tactics (rather than order-based tactics) which was intended to give commanders greater freedom to act on events and exploit opportunities. In public opinion, the German Army was, and sometimes still is, seen as a high-tech army. However, such modern equipment, while featured much in propaganda, was often only available in relatively small numbers. Only 40% to 60% of all units in the Eastern Front were motorized, baggage trains often relied on horse-drawn trailers due to poor roads and weather conditions in the Soviet Union, and for the same reasons many soldiers marched on foot or used bicycles as bicycle infantry

Bicycle infantry are infantry soldiers who maneuver on (or, more often, between) battlefields using military bicycles. The term dates from the late 19th century, when the "safety bicycle" became popular in Europe, the United States, and Austra ...

. As the fortunes of war turned against them, the Germans were in constant retreat from 1943 and onward.

The Panzer division

A Panzer division was one of the Division (military)#Armored division, armored (tank) divisions in the German Army (1935–1945), army of Nazi Germany during World War II. Panzer divisions were the key element of German success in the Blitzkrieg, ...

s were vital to the German army's early success. In the strategies of the ''Blitzkrieg'', the ''Wehrmacht'' combined the mobility of light tanks with airborne assault to quickly progress through weak enemy lines, enabling the German army to quickly take over Poland and France. These tanks were used to break through enemy lines, isolating regiments from the main force so that the infantry behind the tanks could quickly kill or capture the enemy troops.

Air Force

Originally outlawed by the Treaty of Versailles, the ''Luftwaffe

The Luftwaffe () was the aerial warfare, aerial-warfare branch of the before and during World War II. German Empire, Germany's military air arms during World War I, the of the Imperial German Army, Imperial Army and the of the Imperial Ge ...

'' was officially established in 1935, under the leadership of Hermann Göring

Hermann Wilhelm Göring (or Goering; ; 12 January 1893 – 15 October 1946) was a German Nazism, Nazi politician, aviator, military leader, and convicted war criminal. He was one of the most powerful figures in the Nazi Party, which gov ...

. First gaining experience in the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War () was a military conflict fought from 1936 to 1939 between the Republican faction (Spanish Civil War), Republicans and the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalists. Republicans were loyal to the Left-wing p ...

, it was a key element in the early ''Blitzkrieg'' campaigns (Poland, France 1940, USSR 1941). The ''Luftwaffe'' concentrated production on fighters and (small) tactical bombers, like the Messerschmitt Bf 109

The Messerschmitt Bf 109 is a monoplane fighter aircraft that was designed and initially produced by the Nazi Germany, German aircraft manufacturer Messerschmitt#History, Bayerische Flugzeugwerke (BFW). Together with the Focke-Wulf Fw 190, the ...

fighter and the Junkers Ju 87

The Junkers Ju 87, popularly known as the "Stuka", is a German dive bomber and ground-attack aircraft. Designed by Hermann Pohlmann, it first flew in 1935. The Ju 87 made its combat debut in 1937 with the Luftwaffe's Condor Legion during the ...

''Stuka'' dive bomber. The planes cooperated closely with the ground forces. Overwhelming numbers of fighters assured air-supremacy, and the bombers would attack command- and supply-lines, depots, and other support targets close to the front. The ''Luftwaffe'' would also be used to transport paratroopers, as first used during Operation Weserübung

Operation Weserübung ( , , 9 April – 10 June 1940) was the invasion of Denmark and Norway by Nazi Germany during World War II. It was the opening operation of the Norwegian Campaign.

In the early morning of 9 April 1940 (, "Weser Day"), Ge ...

. Due to the Army's sway with Hitler, the ''Luftwaffe'' was often subordinated to the Army, resulting in it being used as a tactical support role and losing its strategic capabilities.

The Western Allies' strategic bombing campaign against German industrial targets (particularly the round-the-clock Combined Bomber Offensive

The Combined Bomber Offensive (CBO) was an Allied offensive of strategic bombing during World War II in Europe. The primary portion of the CBO was directed against Luftwaffe targets which were the highest priority from June 1943 to 1 April 1944. ...

) and Germany's Defence of the Reich

The Defence of the Reich () is the name given to the military strategy, strategic defensive aerial campaign fought by the Luftwaffe of Nazi Germany over German-occupied Europe and Germany during World War II against the Allied Strategic bombing ...

deliberately forced the ''Luftwaffe'' into a war of attrition. With German fighter force destroyed, the Western Allies had air supremacy over the battlefield, denying support to German forces on the ground and using its own fighter-bombers to attack and disrupt. Following the losses in Operation Bodenplatte

Operation Bodenplatte (; "Baseplate"), launched on 1 January 1945, was an attempt by the German Luftwaffe to cripple Allies of World War II, Allied air forces in the Low Countries during the World War II, Second World War. The goal of ''Bodenpl ...

in 1945, the ''Luftwaffe'' was no longer an effective force.

Navy

The Treaty of Versailles disallowed submarines, while limiting the size of the ''Reichsmarine

The () was the name of the German Navy during the Weimar Republic and first two years of Nazi Germany. It was the naval branch of the , existing from 1919 to 1935. In 1935, it became known as the ''Kriegsmarine'' (War Navy), a branch of the '' ...

'' to six battleships, six cruisers, and twelve destroyers. Following the creation of the ''Wehrmacht'', the navy was renamed the ''Kriegsmarine''.

With the signing of the Anglo-German Naval Agreement

The Anglo-German Naval Agreement (AGNA) of 18 June 1935 was a naval agreement between the United Kingdom and Germany regulating the size of the ''Kriegsmarine'' in relation to the Royal Navy.

The Anglo-German Naval Agreement fixed a ratio where ...

, Germany was allowed to increase its navy's size to be 35:100 tonnage of the Royal Navy, and allowed for the construction of U-boats. This was partly done to appease Germany, and because Britain believed the ''Kriegsmarine'' would not be able to reach the 35% limit until 1942. The navy was also prioritized last in the German rearmament scheme, making it the smallest of the branches.

In the Battle of the Atlantic

The Battle of the Atlantic, the longest continuous military campaign in World War II, ran from 1939 to the defeat of Nazi Germany in 1945, covering a major part of the naval history of World War II. At its core was the Allies of World War II, ...

, the initially successful German U-boat

U-boats are Submarine#Military, naval submarines operated by Germany, including during the World War I, First and Second World Wars. The term is an Anglicization#Loanwords, anglicized form of the German word , a shortening of (), though the G ...

fleet arm was eventually defeated due to Allied technological innovations like sonar

Sonar (sound navigation and ranging or sonic navigation and ranging) is a technique that uses sound propagation (usually underwater, as in submarine navigation) to navigate, measure distances ( ranging), communicate with or detect objects o ...

, radar

Radar is a system that uses radio waves to determine the distance ('' ranging''), direction ( azimuth and elevation angles), and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It is a radiodetermination method used to detect and track ...

, and the breaking of the Enigma code.

Large surface vessels were few in number due to construction limitations by international treaties prior to 1935. The "pocket battleships" and were important as commerce raiders only in the opening year of the war. No aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and hangar facilities for supporting, arming, deploying and recovering carrier-based aircraft, shipborne aircraft. Typically it is the ...

was operational, as German leadership lost interest in the which had been launched in 1938.

Following the loss of the in 1941, with Allied air-superiority threatening the remaining battle-cruisers in French Atlantic harbors, the ships were ordered to make the Channel Dash

The Channel Dash (, Operation Cerberus) was a German naval operation during the Second World War. A (German Navy) squadron comprising two s, and , the heavy cruiser and their escorts was evacuated from Brest in Brittany to German ports. '' ...

back to German ports. Operating from fjords along the coast of Norway, which had been occupied since 1940, convoys from North America to the Soviet port of Murmansk could be intercepted though the spent most of her career as fleet in being

In naval warfare, a "fleet-in-being" is a term used to describe a naval force that extends a controlling influence without ever leaving port. Were the fleet to leave port and face the enemy, it might lose in battle and no longer influence the ...

. After the appointment of Karl Dönitz as Grand Admiral of the ''Kriegsmarine'' (in the aftermath of the Battle of the Barents Sea

The Battle of the Barents Sea was a World War II naval engagement on 31 December 1942 between warships of the German Navy (''Kriegsmarine'') and British ships escorting Convoy JW 51B to Kola Inlet in the USSR. The action took place in the Bar ...

), Germany stopped constructing battleships and cruisers in favor of U-boats. Though by 1941, the navy had already lost a number of its large surface ships, which could not be replenished during the war.

The ''Kriegsmarine''s most significant contribution to the German war effort was the deployment of its nearly 1,000 U-boats to strike at Allied convoys. The German naval strategy was to attack the convoys in an attempt to prevent the United States from interfering in Europe and to starve out the British. Karl Doenitz, the U-Boat Chief, began unrestricted submarine warfare which cost the Allies 22,898 men and 1,315 ships. The U-boat war remained costly for the Allies until early spring of 1943 when the Allies began to use countermeasures against U-Boats such as the use of Hunter-Killer groups, airborne radar, torpedoes and mines like the FIDO. The submarine war cost the ''Kriegsmarine'' 757 U-boats, with more than 30,000 U-boat crewmen killed.

Coexistence with the Waffen-SS

In the beginning, there was friction between the ''SS'' and the army. The army feared the ''SS'' would attempt to become a legitimate part of the armed forces of Nazi Germany, and the two groups disagreed about how the limited supply of armaments should be divided. However, on 17 August 1938, Hitler codified the role of the ''SS'' and the army in order to end the feud between the two. The arming of the ''SS'' was to be "procured from the ''Wehrmacht'' upon payment", however "in peacetime, no organizational connection with the ''Wehrmacht'' exists." The army was however allowed to check the budget of the ''SS'' and inspect the combat readiness of the ''SS'' troops. In the event of mobilization, the ''Waffen-SS'' field units could be placed under the operational control of the OKW or the OKH. All decisions regarding this would be at Hitler's personal discretion. Though there existed conflict between the ''SS'' and ''Wehrmacht'', many ''SS'' officers were former army officers, which ensured continuity and understanding between the two. Throughout the war, army and ''SS'' soldiers worked together in various combat situations, creating bonds between the two groups.Guderian

Heinz Wilhelm Guderian (; 17 June 1888 – 14 May 1954) was a German general during World War II who later became a successful memoirist. A pioneer and advocate of the "blitzkrieg" approach, he played a central role in the development of ...

noted that every day the war continued the Army and the ''SS'' became closer together. Towards the end of the war, army units would even be placed under the command of the ''SS'', in Italy and the Netherlands. The relationship between the ''Wehrmacht'' and the ''SS'' improved; however, the ''Waffen-SS'' was never considered "the fourth branch of the ''Wehrmacht''."

Theatres and campaigns

The ''Wehrmacht'' directed combat operations during World War II (from 1 September 19398 May 1945) as theGerman Reich

German ''Reich'' (, from ) was the constitutional name for the German nation state that existed from 1871 to 1945. The ''Reich'' became understood as deriving its authority and sovereignty entirely from a continuing unitary German ''Volk'' ("na ...

's armed forces umbrella command-organization. After 1941 the OKH

The (; abbreviated OKH) was the high command of the Army of Nazi Germany. It was founded in 1935 as part of Adolf Hitler's rearmament of Germany. OKH was ''de facto'' the most important unit within the German war planning until the defeat ...

became the ''de facto'' Eastern Theatre higher-echelon command-organization for the ''Wehrmacht'', excluding ''Waffen-SS

The (; ) was the military branch, combat branch of the Nazi Party's paramilitary ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS) organisation. Its formations included men from Nazi Germany, along with Waffen-SS foreign volunteers and conscripts, volunteers and conscr ...

'' except for operational and tactical combat purposes. The OKW

The (; abbreviated OKW ː kaːˈveArmed Forces High Command) was the supreme military command and control staff of Nazi Germany during World War II, that was directly subordinated to Adolf Hitler. Created in 1938, the OKW replaced the Re ...

conducted operations in the Western Theatre. The operations by the ''Kriegsmarine'' in the North and Mid-Atlantic can also be considered as separate theatres, considering the size of the area of operations In U.S. armed forces parlance, an area of operations (AO) is an operational area defined by the force commander for land, air, and naval forces' conduct of combat and non-combat activities. Areas of operations do not typically encompass the entire ...

and their remoteness from other theatres.

The ''Wehrmacht'' fought on other fronts, sometimes three simultaneously; redeploying troops from the intensifying theatre in the East to the West after the Normandy landings

The Normandy landings were the landing operations and associated airborne operations on 6 June 1944 of the Allies of World War II, Allied invasion of Normandy in Operation Overlord during the Second World War. Codenamed Operation Neptune and ...

caused tensions between the General Staffs of both the OKW and the OKHas Germany lacked sufficient materiel and manpower for a two-front war of such magnitude.

Eastern theatre

Major campaigns and battles in Eastern and Central Europe included: * Czechoslovakian campaign (1938–1945) *Invasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland, also known as the September Campaign, Polish Campaign, and Polish Defensive War of 1939 (1 September – 6 October 1939), was a joint attack on the Second Polish Republic, Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany, the Slovak R ...

(''Fall Weiss'') (1939)

* Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and several of its European Axis allies starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during World War II. More than 3.8 million Axis troops invaded the western Soviet Union along ...

(1941), conducted by Army Group North

Army Group North () was the name of three separate army groups of the Wehrmacht during World War II. Its rear area operations were organized by the Army Group North Rear Area.

The first Army Group North was deployed during the invasion of Pol ...

, Army Group Centre

Army Group Centre () was the name of two distinct strategic German Army Groups that fought on the Eastern Front in World War II. The first Army Group Centre was created during the planning of Operation Barbarossa, Germany's invasion of the So ...

, and Army Group South

Army Group South () was the name of one of three German Army Groups during World War II.

It was first used in the 1939 September Campaign, along with Army Group North to invade Poland. In the invasion of Poland, Army Group South was led by Ge ...

* Battle of Moscow

The Battle of Moscow was a military campaign that consisted of two periods of strategically significant fighting on a sector of the Eastern Front during World War II, between October 1941 and January 1942. The Soviet defensive effort frustrated H ...

(1941)

* Battles of Rzhev

The Battles of Rzhev () were a series of Red Army offensives against the Wehrmacht between 8 January 1942 and 31 March 1943, on the Eastern Front of World War II. The battles took place in the northeast of Smolensk Oblast and the south of Tve ...

(1942–1943)

* Battle of Stalingrad

The Battle of Stalingrad ; see . rus, links=on, Сталинградская битва, r=Stalingradskaya bitva, p=stəlʲɪnˈɡratskəjə ˈbʲitvə. (17 July 19422 February 1943) was a major battle on the Eastern Front of World War II, ...

(1942–1943)

* Battle of the Caucasus

The Battle of the Caucasus was a series of Axis and Soviet operations in the Caucasus as part of the Eastern Front of World War II. On 25 July 1942, German troops captured Rostov-on-Don, opening the Caucasus region of the southern Soviet ...

(1942–1943)

* Battle of Kursk

The Battle of Kursk, also called the Battle of the Kursk Salient, was a major World War II Eastern Front battle between the forces of Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union near Kursk in southwestern Russia during the summer of 1943, resulting in ...

(Operation Citadel) (1943)

* Battle of Kiev (1943)

* Operation Bagration

Operation Bagration () was the codename for the 1944 Soviet Byelorussian strategic offensive operation (), a military campaign fought between 22 June and 19 August 1944 in Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic, Soviet Byelorussia in the Eastern ...

(1944)

* Nazi security warfare

Nazism (), formally named National Socialism (NS; , ), is the far-right totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During Hitler's rise to power, it was frequen ...

– largely carried out by security divisions of the ''Wehrmacht'', Order Police

The ''Ordnungspolizei'' (''Orpo'', , meaning "Order Police") were the uniformed police force in Nazi Germany from 1936 to 1945. The Orpo was absorbed into the Nazi monopoly of power after regional police jurisdiction was removed in favour of t ...

and ''Waffen-SS'' units in the occupied territories behind Axis frontlines.

Western theatre

*Phoney War

The Phoney War (; ; ) was an eight-month period at the outset of World War II during which there were virtually no Allied military land operations on the Western Front from roughly September 1939 to May 1940. World War II began on 3 Septembe ...

(''Sitzkrieg'', September 1939 to May 1940) between the invasion of Poland and the Battle of France

* Operation Weserübung

Operation Weserübung ( , , 9 April – 10 June 1940) was the invasion of Denmark and Norway by Nazi Germany during World War II. It was the opening operation of the Norwegian Campaign.

In the early morning of 9 April 1940 (, "Weser Day"), Ge ...

** German invasion of Denmark German invasion of Denmark may refer to:

*German invasion during the First Schleswig War (1848–1852)

*German invasion during the Second Schleswig War (1864)

*German invasion of Denmark (1940)

The German invasion of Denmark (), was the German ...

– 9 April 1940

** The Norwegian Campaign – 9 April to 10 June 1940

* ''Fall Gelb''

**Battle of Belgium

The invasion of Belgium or Belgian campaign (10–28 May 1940), often referred to within Belgium as the 18 Days' Campaign (; ), formed part of the larger Battle of France, an Military offensive, offensive campaign by Nazi Germany, Germany during ...

10 to 28 May 1940

**German invasion of Luxembourg

The German invasion of Luxembourg was part of Case Yellow (), the German invasion of the Low Countries—Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands—and France during World War II. The battle began on 10 May 1940 and lasted just one day. Facing ...

10 May 1940

**Battle of the Netherlands

The German invasion of the Netherlands (), otherwise known as the Battle of the Netherlands (), was a military campaign, part of Battle of France, Case Yellow (), the Nazi German invasion of the Low Countries (Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Neth ...

– 10 to 17 May 1940

**Battle of France

The Battle of France (; 10 May – 25 June 1940), also known as the Western Campaign (), the French Campaign (, ) and the Fall of France, during the Second World War was the Nazi Germany, German invasion of the Low Countries (Belgium, Luxembour ...

– 10 May to 25 June 1940

* Battle of Britain

The Battle of Britain () was a military campaign of the Second World War, in which the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) of the Royal Navy defended the United Kingdom (UK) against large-scale attacks by Nazi Germany's air force ...

(1940)

* Battle of the Atlantic

The Battle of the Atlantic, the longest continuous military campaign in World War II, ran from 1939 to the defeat of Nazi Germany in 1945, covering a major part of the naval history of World War II. At its core was the Allies of World War II, ...

(1939–1945)

* Battle of Normandy

Operation Overlord was the codename for the Battle of Normandy, the Allied operation that launched the successful liberation of German-occupied Western Europe during World War II. The operation was launched on 6 June 1944 (D-Day) with the N ...

(1944)

* Allied invasion of southern France (1944)

* Ardennes Offensive

The Ardennes ( ; ; ; ; ), also known as the Ardennes Forest or Forest of Ardennes, is a region of extensive forests, rough terrain, rolling hills and ridges primarily in Belgium and Luxembourg, extending into Germany and France.

Geological ...

(1944–1945)

* Defense of the Reich

The Defence of the Reich () is the name given to the strategic defensive aerial campaign fought by the Luftwaffe of Nazi Germany over German-occupied Europe and Germany during World War II against the Allied strategic bombing campaign. Its aim ...

air-campaign, 1939 to 1945

Mediterranean theatre

For a time, the Axis Mediterranean Theatre and theNorth African Campaign

The North African campaign of World War II took place in North Africa from 10 June 1940 to 13 May 1943, fought between the Allies and the Axis Powers. It included campaigns in the Libyan and Egyptian deserts (Western Desert campaign, Desert Wa ...

were conducted as a joint campaign with the Italian Army

The Italian Army ( []) is the Army, land force branch of the Italian Armed Forces. The army's history dates back to the Italian unification in the 1850s and 1860s. The army fought in colonial engagements in China and Italo-Turkish War, Libya. It ...

, and may be considered a separate theatre

Theatre or theater is a collaborative form of performing art that uses live performers, usually actors to present experiences of a real or imagined event before a live audience in a specific place, often a Stage (theatre), stage. The performe ...

.

* Invasion of the Balkans and Greece (Operation Marita) (1940–1941)

* Battle of Crete

The Battle of Crete (, ), codenamed Operation Mercury (), was a major Axis Powers, Axis Airborne forces, airborne and amphibious assault, amphibious operation during World War II to capture the island of Crete. It began on the morning of 20 May ...

(1941)

* The North African Campaign

The North African campaign of World War II took place in North Africa from 10 June 1940 to 13 May 1943, fought between the Allies and the Axis Powers. It included campaigns in the Libyan and Egyptian deserts (Western Desert campaign, Desert Wa ...

in Libya, Tunisia and Egypt between the UK and Commonwealth (and later, U.S.) forces and the Axis forces

* The Italian Theatre

The theatre of Italy originates from the Middle Ages, with its background dating back to the times of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek colonies of Magna Graecia, in southern Italy, the theatre of the Italic peoples and the theatre of ancient R ...

was a continuation of the Axis defeat in North Africa, and was a campaign for defence of Italy

Casualties

More than 6,000,000 soldiers were wounded during the conflict, while more than 11,000,000 became prisoners. In all, approximately 5,318,000 soldiers from Germany and other nationalities fighting for the German armed forces—including the ''Waffen-SS'', ''Volkssturm'' and foreign collaborationist units—are estimated to have been killed in action, died of wounds, died in custody or gone missing in World War II. Included in this number are 215,000 Soviet citizens conscripted by Germany.

According to Frank Biess,

More than 6,000,000 soldiers were wounded during the conflict, while more than 11,000,000 became prisoners. In all, approximately 5,318,000 soldiers from Germany and other nationalities fighting for the German armed forces—including the ''Waffen-SS'', ''Volkssturm'' and foreign collaborationist units—are estimated to have been killed in action, died of wounds, died in custody or gone missing in World War II. Included in this number are 215,000 Soviet citizens conscripted by Germany.

According to Frank Biess,

Jeffrey Herf

Jeffrey C. Herf (born April 24, 1947) is an American historian of modern Europe, particularly modern Germany. He is Distinguished University Professor, of modern European history, Emeritus at the University of Maryland, College Park.

Biography

H ...

wrote that:

In addition to the losses, at the hands of the elements and enemy fighting, at least 20,000 soldiers were executed as sentences by the military court. In comparison, the Red Army executed 135,000, France 102, the US 146 and the UK 40.

War crimes

Nazi propaganda had told ''Wehrmacht'' soldiers to wipe out what were variously called Jewish Bolshevik subhumans, the Mongol hordes, the Asiatic flood and the red beast. While the principal perpetrators of the civil suppression behind the front lines amongst German armed forces were the Nazi German "political" armies (the ''SS-Totenkopfverbände

(SS-TV; or 'SS Death's Head Battalions') was a major branch of the Nazi Party's paramilitary (SS) organisation. It was responsible for administering the Nazi concentration camps, concentration camps and extermination camps of Nazi Germany ...

'', the ''Waffen-SS

The (; ) was the military branch, combat branch of the Nazi Party's paramilitary ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS) organisation. Its formations included men from Nazi Germany, along with Waffen-SS foreign volunteers and conscripts, volunteers and conscr ...

'', and the ''Einsatzgruppen

(, ; also 'task forces') were (SS) paramilitary death squads of Nazi Germany that were responsible for mass murder, primarily by shooting, during World War II (1939–1945) in German-occupied Europe. The had an integral role in the imp ...

'', which were responsible for mass-murders, primarily by implementation of the so-called Final Solution of the Jewish Question

The Final Solution or the Final Solution to the Jewish Question was a plan orchestrated by Nazi Germany during World War II for the genocide of individuals they defined as Jews. The "Final Solution to the Jewish question" was the official ...

in occupied territories), the traditional armed forces represented by the ''Wehrmacht'' committed and ordered war crimes of their own (e.g. the Commissar Order

The Commissar Order () was an order issued by the German High Command ( OKW) on 6 June 1941 before Operation Barbarossa. Its official name was Guidelines for the Treatment of Political Commissars (''Richtlinien für die Behandlung politischer Ko ...

), particularly during the invasion of Poland in 1939 and later in the war against the Soviet Union.

Cooperation with the ''SS''

Prior to the outbreak of war, Hitler informed senior ''Wehrmacht'' officers that actions "which would not be in the taste of German generals", would take place in occupied areas and ordered them that they "should not interfere in such matters but restrict themselves to their military duties". Some ''Wehrmacht'' officers initially showed a strong dislike for the ''SS'' and objected to the army committing war crimes with the ''SS'', though these objections were not against the idea of the atrocities themselves. Later during the war, relations between the ''SS'' and ''Wehrmacht'' improved significantly. The common soldier had no qualms with the ''SS'', and often assisted them in rounding up civilians for executions. The Army's Chief of Staff GeneralFranz Halder

Franz Halder (30 June 1884 – 2 April 1972) was a German general and the chief of staff of the Oberkommando des Heeres, Army High Command (OKH) in Nazi Germany from 1938 until September 1942. During World War II, he directed the planning and i ...

in a directive declared that in the event of guerrilla attacks, German troops were to impose "collective measures of force" by massacring entire villages. Cooperation between the ''SS Einsatzgruppen'' and the ''Wehrmacht'' involved supplying the death squads with weapons, ammunition, equipment, transport, and even housing. Partisan fighters, Jews, and Communists became synonymous enemies of the Nazi regime and were hunted down and exterminated by the ''Einsatzgruppen'' and ''Wehrmacht'' alike, something revealed in numerous field journal entries from German soldiers. With the implementation of the Hunger Plan

The Hunger Plan () was a partially implemented plan developed by Nazi Germany, Nazi bureaucrats during World War II to seize food from the Soviet Union and give it to German soldiers and civilians. The plan entailed the genocide by Starvation (cri ...

, hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions, of Soviet civilians were deliberately starved to death, as the Germans seized food for their armies and fodder for their draft horses. According to Thomas Kühne: "an estimated 300,000–500,000 people were killed during the ''Wehrmacht''s Nazi security warfare

Nazism (), formally named National Socialism (NS; , ), is the far-right totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During Hitler's rise to power, it was frequen ...

in the Soviet Union."

While secretly listening to conversations of captured German generals, British officials became aware that the German Army had taken part in the atrocities and mass-murder of Jews and were guilty of war crimes. American officials learned of the ''Wehrmacht''s atrocities in much the same way. Taped conversations of soldiers detained as POWs revealed how some of them voluntarily participated in mass executions.

Crimes against civilians