Music hall on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Music hall is a type of British theatrical entertainment that was most popular from the early

accessed 1 November 2007

The establishment often regarded as the first true music hall was the

The establishment often regarded as the first true music hall was the  The construction of Weston's Music Hall,

The construction of Weston's Music Hall,

accessed 31 March 2007 Significant West End music halls include: * The Oxford Music Hall, 14/16 * The Bedford, 93–95 High Street,

* The Bedford, 93–95 High Street,

The development of syndicates controlling a number of theatres, such as the Stoll circuit, increased tensions between employees and employers. On 22 January 1907, a dispute between artists, stage hands and managers of the Holborn Empire worsened. Strikes in other London and suburban halls followed, organised by the Variety Artistes' Federation. The strike lasted for almost two weeks and was known as the ''Music Hall War''. It became extremely well known, and was advocated enthusiastically by the main spokesmen of the trade union and Labour movement –

The development of syndicates controlling a number of theatres, such as the Stoll circuit, increased tensions between employees and employers. On 22 January 1907, a dispute between artists, stage hands and managers of the Holborn Empire worsened. Strikes in other London and suburban halls followed, organised by the Variety Artistes' Federation. The strike lasted for almost two weeks and was known as the ''Music Hall War''. It became extremely well known, and was advocated enthusiastically by the main spokesmen of the trade union and Labour movement –

1914

, "Pack up Your Troubles"

1915

, " It's a Long Way to Tipperary"

1914

and " We Don't Want to Lose You (But We Think You Ought To Go)"

1914

, were sung by music hall audiences, and sometimes by soldiers in the trenches. Many songs promoted recruitment ("All the boys in khaki get the nice girls", 1915); others satirised particular elements of the war experience. "What did you do in the Great war, Daddy"

1919

criticised profiteers and slackers; Vesta Tilley's "I've got a bit of a blighty one"

1916

showed a soldier delighted to have a wound just serious enough to be sent home. The rhymes give a sense of grim humour ("When they wipe my face with sponges / and they feed me on

1917

, popularised by male impersonator Ella Shields.

Paris music halls all faced stiff competition in the

Paris music halls all faced stiff competition in the  One of the most popular entertainers in Paris during the period was the American singer

One of the most popular entertainers in Paris during the period was the American singer  The music-halls suffered growing hardships in the 1930s. The Olympia was converted into a movie theater, and others closed. Others however continued to thrive. In 1937 and 1930, the Casino de Paris presented shows with Maurice Chevalier, who had already achieved success as an actor and singer in Hollywood.

In 1935, a twenty-year old singer named Édith Piaf was discovered in the Pigalle by nightclub owner Louis Leplée, whose club, Le Gerny, off the

The music-halls suffered growing hardships in the 1930s. The Olympia was converted into a movie theater, and others closed. Others however continued to thrive. In 1937 and 1930, the Casino de Paris presented shows with Maurice Chevalier, who had already achieved success as an actor and singer in Hollywood.

In 1935, a twenty-year old singer named Édith Piaf was discovered in the Pigalle by nightclub owner Louis Leplée, whose club, Le Gerny, off the

accessed 2 November 2007 Music halls were originally tavern rooms which provided entertainment, in the form of music and speciality acts, for their patrons. By the middle years of the nineteenth century, the first purpose-built music halls were being built in London. The halls created a demand for new and catchy popular songs, that could no longer be met from the traditional In Britain, the first music hall songs often promoted the alcoholic wares of the owners of the halls in which they were performed. Songs like "Glorious Beer", and the first major music hall success, " Champagne Charlie" (1867) had a major influence in establishing the new art form. The tune of "Champagne Charlie" became used for

In Britain, the first music hall songs often promoted the alcoholic wares of the owners of the halls in which they were performed. Songs like "Glorious Beer", and the first major music hall success, " Champagne Charlie" (1867) had a major influence in establishing the new art form. The tune of "Champagne Charlie" became used for

* " A Little of What You Fancy Does You Good* ( George Arthurs, Fred W. Leigh), sung by Marie Lloyd

* " Any Old Iron" ( Charles Collins; Terry Sheppard) sung by Harry Champion in 1911.

* " Ask a P'liceman" (

* " A Little of What You Fancy Does You Good* ( George Arthurs, Fred W. Leigh), sung by Marie Lloyd

* " Any Old Iron" ( Charles Collins; Terry Sheppard) sung by Harry Champion in 1911.

* " Ask a P'liceman" ( * " I Do Like to Be Beside the Seaside" (John A. Glover-Kind) sung by Mark Sheridan.

* " I'm Henery the Eighth, I Am" (1910) (Fred Murray and R. P. Weston) sung by Harry Champion.

* " It's a Long Way to Tipperary" (1912) ( Jack Judge and Harry Williams) sung by John McCormack.

* " Let's All Go Down the Strand" (

* " I Do Like to Be Beside the Seaside" (John A. Glover-Kind) sung by Mark Sheridan.

* " I'm Henery the Eighth, I Am" (1910) (Fred Murray and R. P. Weston) sung by Harry Champion.

* " It's a Long Way to Tipperary" (1912) ( Jack Judge and Harry Williams) sung by John McCormack.

* " Let's All Go Down the Strand" (

* Fred Albert (1843–1886)

* Fred Barnes (1885–1938)

* Ida Barr (1882–1967)

* Bessie Bellwood (1856–1896)

* Herbert Campbell (1844–1904)

* Aimée Campton (1882–1930)

* Kate Carney (1869–1950)

* Harry Champion (1866–1942)

* Charles Chaplin Sr. (1863–1901)

*

* Fred Albert (1843–1886)

* Fred Barnes (1885–1938)

* Ida Barr (1882–1967)

* Bessie Bellwood (1856–1896)

* Herbert Campbell (1844–1904)

* Aimée Campton (1882–1930)

* Kate Carney (1869–1950)

* Harry Champion (1866–1942)

* Charles Chaplin Sr. (1863–1901)

*

Gaston & Andre

G. H. Elliott, Sam Curtis, and Frank Boston & Betty. * A music hall with a 'memory man' act provides a pivotal plot device in the classic 1935

London was the centre of music hall with hundreds of venues, often in the entertainment rooms of public houses. With the decline in popularity of music hall, many were abandoned, or converted to other uses such as cinemas, and their interiors lost. There are a number of purpose-built survivors, including the Hackney Empire, an outstanding example of the late music hall period ( Frank Matcham 1901). This has been restored to its Moorish splendour and now provides an eclectic programme of events from opera to "Black Variety Nights". The architectural writer

London was the centre of music hall with hundreds of venues, often in the entertainment rooms of public houses. With the decline in popularity of music hall, many were abandoned, or converted to other uses such as cinemas, and their interiors lost. There are a number of purpose-built survivors, including the Hackney Empire, an outstanding example of the late music hall period ( Frank Matcham 1901). This has been restored to its Moorish splendour and now provides an eclectic programme of events from opera to "Black Variety Nights". The architectural writer  In the nondescript Grace's Alley, off Cable Street,

In the nondescript Grace's Alley, off Cable Street,

''Early Music Hall in Bristol''

(Bristol Historical Association pamphlets, no. 44, 1979), 20 pp. * Beeching, Christopher,''The Heaviest of Swells – A life and times in the Music Halls'', (DCG Publications, 2010) * Bratton, J.S., ed., ''Music Hall: Performance & Style'' (Milton Keynes, Open University Press, 1986) * Bruce, Frank, ''More Variety Days: Fairs, Fit-ups, Music hall, Variety Theatre, Clubs, Cruises and

Theatre and performance reading lists – Music Hall and Variety

The British Music Hall Society

The Music Hall Guild of Great Britain and America

links to transcriptions of historical sources on performances and venues

University lecture on women in the British music hall during the Great War 1914–1918

{{DEFAULTSORT:Music Hall British popular music British styles of music Theatre of the United Kingdom Theatrical genres

Victorian era

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the reign of Queen Victoria, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. Slightly different definitions are sometimes used. The era followed the ...

, beginning around 1850, through the Great War. It faded away after 1918 as the halls rebranded their entertainment as variety. Perceptions of a distinction in Britain between bold and scandalous music hall entertainment and subsequent, more respectable variety entertainment differ. Music hall involved a mixture of popular songs, comedy, speciality acts, and variety entertainment. The term is derived from a type of theatre or venue in which such entertainment took place. In North America vaudeville

Vaudeville (; ) is a theatrical genre of variety entertainment which began in France in the middle of the 19th century. A ''vaudeville'' was originally a comedy without psychological or moral intentions, based on a comical situation: a drama ...

was in some ways analogous to British music hall, featuring rousing songs and comic acts.

Originating in saloon bars within pubs during the 1830s, music hall entertainment became increasingly popular with audiences. So much so, that during the 1850s some public houses were demolished, and specialised music hall theatres developed in their place. These theatres were designed chiefly so that people could consume food and alcohol and smoke tobacco in the auditorium while the entertainment took place, with the cheapest seats located in the gallery. This differed from the conventional type of theatre, which seats the audience in stalls with a separate bar-room. Major music halls were based around London. Early examples included: the Canterbury Music Hall in Lambeth

Lambeth () is a district in South London, England, which today also gives its name to the (much larger) London Borough of Lambeth. Lambeth itself was an ancient parish in the county of Surrey. It is situated 1 mile (1.6 km) south of Charin ...

, Wilton's Music Hall in Tower Hamlets, and The Middlesex in Drury Lane

Drury Lane is a street on the boundary between the Covent Garden and Holborn areas of London, running between Aldwych and High Holborn. The northern part is in the borough of London Borough of Camden, Camden and the southern part in the City o ...

, otherwise known as the Old Mo. By the mid-19th century, the halls cried out for many new and catchy songs. As a result professional songwriters were enlisted to provide the music for a plethora of star performers, such as Marie Lloyd, Dan Leno, Little Tich, and George Leybourne. All manner of other entertainment was performed: male and female impersonators, lions comiques, mime artists and impressionists, trampoline acts, and comic pianists (such as John Orlando Parry and George Grossmith) were just a few of the many types of entertainments the audiences could expect to find over the next forty years.

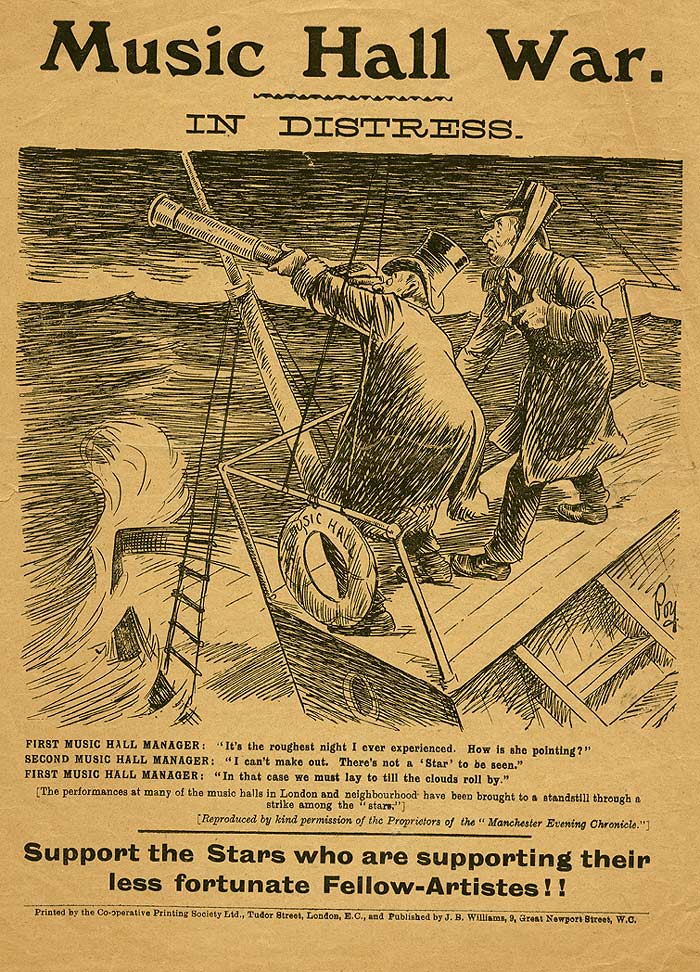

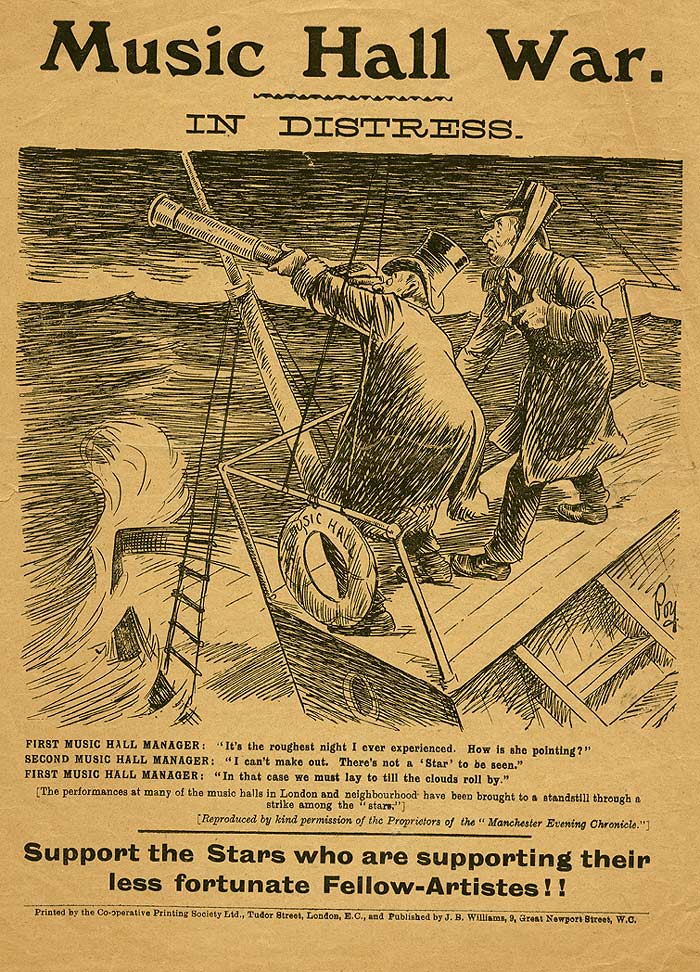

The Music Hall Strike of 1907 was an important industrial conflict. It was a dispute between artists and stage hands on one hand, and theatre managers on the other. The halls had recovered by the start of the First World War and were used to stage charity events in aid of the war effort. Music hall entertainment continued after the war, but became less popular due to upcoming jazz

Jazz is a music genre that originated in the African-American communities of New Orleans, Louisiana, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Its roots are in blues, ragtime, European harmony, African rhythmic rituals, spirituals, h ...

, swing, and big-band dance music acts. Licensing restrictions had also changed, and drinking was banned from the auditorium. A new type of music hall entertainment had arrived, in the form of variety, and many music hall performers failed to make the transition. They were deemed old-fashioned, and with the closure of many halls, music hall entertainment ceased and modern-day variety began.

Origins and development

Music-halls had their origins in 18th century London. They grew with the entertainment provided in the new style saloon bars of pubs during the 1830s. These venues replaced earlier semi-rural amusements provided by fairs and suburbanpleasure garden

A pleasure garden is a park or garden that is open to the public for recreation and entertainment. Pleasure gardens differ from other public gardens by serving as venues for entertainment, variously featuring such attractions as concert halls, b ...

s such as Vauxhall Gardens and the Cremorne Gardens. These latter became subject to urban development and became fewer and less popular.Diana Howard ''London Theatres and Music Halls 1850–1950'' (1970)

From the mid-19th century music halls spread to the provincial cities, such as Bristol.

The saloon was a room where for an admission fee or a greater price at the bar, singing, dancing, drama or comedy was performed. The most famous London saloon of the early days was the Grecian Saloon, established in 1825, at The Eagle (a former tea-garden), 2 Shepherdess Walk, off the City Road in east London. According to John Hollingshead, proprietor of the Gaiety Theatre, London (originally the Strand Music Hall), this establishment was "the father and mother, the dry and wet nurse of the Music Hall". Later known as the Grecian Theatre, it was here that Marie Lloyd made her début at the age of 14 in 1884. It is still famous because of an English nursery rhyme, with the somewhat mysterious lyrics:

Up and down the City RoadAnother famous "song and supper" room of this period was Evans Music-and-Supper Rooms, 43 King Street,

In and out The Eagle

That's the way the money goes

Pop goes the weasel.

Covent Garden

Covent Garden is a district in London, on the eastern fringes of the West End, between St Martin's Lane and Drury Lane. It is associated with the former fruit-and-vegetable market in the central square, now a popular shopping and tourist sit ...

, established in the 1840s by W.H. Evans. This venue was also known as 'Evans Late Joys' – Joy being the name of the previous owner. Other song and supper rooms included the Coal Hole in The Strand, the Cyder Cellars in Maiden Lane, Covent Garden and the Mogul Saloon in Drury Lane

Drury Lane is a street on the boundary between the Covent Garden and Holborn areas of London, running between Aldwych and High Holborn. The northern part is in the borough of London Borough of Camden, Camden and the southern part in the City o ...

.

The music hall as we know it developed from such establishments during the 1850s and were built in and on the grounds of public houses. Such establishments were distinguished from theatres by the fact that in a music hall you would be seated at a table in the auditorium and could drink alcohol and smoke tobacco whilst watching the show. In a theatre, by contrast, the audience was seated in stalls and there was a separate bar-room. An exception to this rule was the Britannia Theatre, Hoxton

Hoxton is an area in the London Borough of Hackney, England. It was Historic counties of England, historically in the county of Middlesex until 1889. Hoxton lies north-east of the City of London, is considered to be a part of London's East End ...

(1841) which somehow managed to evade this regulation and served drinks to its customers. Though a theatre rather than a music hall, this establishment later hosted music-hall variety acts.The Making of the Britannia Theatre – Alan D. Craxford and Reg Mooreaccessed 1 November 2007

Early music halls

The establishment often regarded as the first true music hall was the

The establishment often regarded as the first true music hall was the Canterbury

Canterbury (, ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and UNESCO World Heritage Site, in the county of Kent, England; it was a county borough until 1974. It lies on the River Stour, Kent, River Stour. The city has a mild oceanic climat ...

, 143 Westminster Bridge Road, Lambeth

Lambeth () is a district in South London, England, which today also gives its name to the (much larger) London Borough of Lambeth. Lambeth itself was an ancient parish in the county of Surrey. It is situated 1 mile (1.6 km) south of Charin ...

built by Charles Morton, afterwards dubbed "the Father of the Halls", on the site of a skittle alley next to his pub, the Canterbury Tavern. It opened on 17 May 1852 and was described by the musician and author Benny Green as being "the most significant date in all the history of music hall". The hall looked like most contemporary pub concert rooms, but its replacement in 1854 was of then unprecedented size. It was further extended in 1859, later rebuilt as a variety theatre and finally destroyed by German bombing in 1942. The Canterbury Hall became a model for music halls in other cities too, such as the Bristol

Bristol () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city, unitary authority area and ceremonial county in South West England, the most populous city in the region. Built around the River Avon, Bristol, River Avon, it is bordered by t ...

Canterbury, which was built in 1850s as the first purpose-built music hall in the city.

Another early music hall was The Middlesex, Drury Lane

Drury Lane is a street on the boundary between the Covent Garden and Holborn areas of London, running between Aldwych and High Holborn. The northern part is in the borough of London Borough of Camden, Camden and the southern part in the City o ...

(1851). Popularly known as the 'Old Mo', it was built on the site of the Mogul Saloon. Later converted into a theatre it was demolished in 1965. The New London Theatre stands on its site.

Several large music halls were built in the East End. These included the London Music Hall, otherwise known as The Shoreditch Empire, 95–99 Shoreditch High Street, (1856–1935). This theatre was rebuilt during 1894 by Frank Matcham, the architect of the Hackney Empire. Another in this area was the Royal Cambridge Music Hall, 136 Commercial Street (1864–1936). Designed by William Finch Hill (the designer of the Britannia theatre in nearby Hoxton), it was rebuilt after a fire in 1898.

The construction of Weston's Music Hall,

The construction of Weston's Music Hall, High Holborn

High Holborn ( ) is a street in Holborn and Farringdon Without, Central London, which forms a part of the A40 route from London to Fishguard. It starts in the west at the eastern end of St Giles High Street and runs past the Kingsway and ...

(1857), built up on the site of the Six Cans and Punch Bowl Tavern by the licensed victualler of the premises, Henry Weston, signalled that the West End was fruitful territory for the music hall. During 1906 it was rebuilt as a variety theatre and renamed as the Holborn Empire. It was closed as a result of German action in the Blitz

The Blitz (English: "flash") was a Nazi Germany, German bombing campaign against the United Kingdom, for eight months, from 7 September 1940 to 11 May 1941, during the Second World War.

Towards the end of the Battle of Britain in 1940, a co ...

on the night of 11–12 May 1941 and the building was pulled down in 1960.''British Library on Weston's''accessed 31 March 2007 Significant West End music halls include: * The Oxford Music Hall, 14/16

Oxford Street

Oxford Street is a major road in the City of Westminster in the West End of London, running between Marble Arch and Tottenham Court Road via Oxford Circus. It marks the notional boundary between the areas of Fitzrovia and Marylebone to t ...

(1861) – built on the site of an old coaching inn called the Boar and Castle by Charles Morton, the pioneer music hall developer of The Canterbury, who with this development brought music hall to the West End. Demolished in 1926.

* The London Pavilion (1861). Facade of 1885 rebuild still extant.

* The Alhambra Theatre of Variety (1860) in London, which became a model for Parisian music halls. Some years before the Folies-Bergere it staged circus attractions alongside popular ballets in 55 new productions between 1864 and 1870.

Other large suburban music halls included:

* The Bedford, 93–95 High Street,

* The Bedford, 93–95 High Street, Camden Town

Camden Town () is an area in the London Borough of Camden, around north-northwest of Charing Cross. Historically in Middlesex, it is identified in the London Plan as one of 34 major centres in Greater London.

Laid out as a residential distri ...

, constructed on the site of the tea gardens of a pub called the Bedford Arms. The first building, the Bedford Music Hall (“The Old Bedford”), opened in 1861 and closed in 1898. It was demolished and rebuilt as the larger Bedford Palace of Varieties also known as the Bedford Theatre (“The New Bedford”), which opened in 1899 and operated until 1959. The Bedford was a favourite haunt of the artist Walter Sickert, who featured interior scenes of music halls in many of his paintings, including one entitled '' Little Dot Hetherington at the Old Bedford''. The Bedford was derelict from 1959 and finally demolished in 1969.

* Collins's or Collins', Islington Green (1863). Opened by Sam Collins on 4 November 1863 after he had converted the pre-existing Lansdowne Arms and Music Hall public house. It was colloquially known as 'The Chapel on the Green'. Collins was a star of his own theatre, singing mostly Irish songs specially composed for him. It closed in 1956, after a fire, but the street front of the building still survives (see below).

* Deacons in Clerkenwell

Clerkenwell ( ) is an area of central London, England.

Clerkenwell was an Civil Parish#Ancient parishes, ancient parish from the medieval period onwards, and now forms the south-western part of the London Borough of Islington. The St James's C ...

(1862).

A noted music hall entrepreneur of this time was Carlo Gatti who built a music hall, known as Gatti's, at Hungerford Market in 1857. He sold the music hall to South Eastern Railway in 1862, and the site became Charing Cross railway station. With the proceeds from selling his first music hall, Gatti acquired a restaurant in Westminster Bridge Road, opposite The Canterbury music hall. He converted the restaurant into a second Gatti's music hall, known as "Gatti's-in-the-Road", in 1865. It later became a cinema. The building was badly damaged in the Second World War, and was demolished in 1950. In 1867, he acquired a public house

A pub (short for public house) is in several countries a drinking establishment licensed to serve alcoholic drinks for consumption Licensing laws of the United Kingdom#On-licence, on the premises. The term first appeared in England in the ...

in Villiers Street named "The Arches", under the arches of the elevated railway line leading to Charing Cross station. He opened it as another music hall, known as " Gatti's-in-The-Arches". After his death his family continued to operate the music hall, known for a period as the Hungerford or Gatti's Hungerford Palace of Varieties. It became a cinema in 1910, and the Players' Theatre

The Players' Theatre was a London theatre which opened at 43 King Street, Covent Garden, on 18 October 1936. The club originally mounted period-style musical comedies, introducing Victorian-style music hall in December 1937. The threat of Worl ...

in 1946.

By 1865, there were 32 music halls in London seating between 500 and 5,000 people plus an unknown, but large, number of smaller venues. Numbers peaked in 1878, with 78 large music halls in the metropolis and 300 smaller venues. Thereafter numbers declined due to stricter licensing restrictions imposed by the Metropolitan Board of Works

The Metropolitan Board of Works (MBW) was the upper tier of local government for London between 1856 and 1889, primarily responsible for upgrading infrastructure. It also had a parks and open spaces committee which set aside and opened up severa ...

and London County Council

The London County Council (LCC) was the principal local government body for the County of London throughout its existence from 1889 to 1965, and the first London-wide general municipal authority to be directly elected. It covered the area today ...

, and because of commercial competition between popular large suburban halls and the smaller venues, which put the latter out of business.

A few of the UK's music halls have survived and have retained many of their original features. Among the best examples are:

* Victoria Hall, Settle is a Grade II

In the United Kingdom, a listed building is a structure of particular architectural or historic interest deserving of special protection. Such buildings are placed on one of the four statutory lists maintained by Historic England in England, Hi ...

listed concert hall in Kirkgate, Settle, North Yorkshire

Settle is a market town and civil parishes in England, civil parish in North Yorkshire, England. Historic counties of England, Historically in the West Riding of Yorkshire, the town had a population of 2,421 in the 2001 United Kingdom census, 20 ...

, England. It is the UK's oldest surviving music hall having opened as Settle Music Hall on 11 October 1853. The Music Hall was renamed 'The Victoria Hall' around November 1892.

* Wilton's Music Hall is a Grade II

In the United Kingdom, a listed building is a structure of particular architectural or historic interest deserving of special protection. Such buildings are placed on one of the four statutory lists maintained by Historic England in England, Hi ...

listed building

In the United Kingdom, a listed building is a structure of particular architectural or historic interest deserving of special protection. Such buildings are placed on one of the four statutory lists maintained by Historic England in England, Hi ...

in Shadwell, built by John Wilton in 1859 as a music hall and now run as a multi-arts performance space in Graces Alley, off Cable Street in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets.

*The Britannia Music Hall (later known as The Panopticon or The Britannia Panopticon) in Trongate, Glasgow

Glasgow is the Cities of Scotland, most populous city in Scotland, located on the banks of the River Clyde in Strathclyde, west central Scotland. It is the List of cities in the United Kingdom, third-most-populous city in the United Kingdom ...

, Scotland was built in 1857/58 and is located above an amusement arcade at 113-117 Trongate.

Variety theatre

A new era of variety theatre was developed by the rebuilding of the London Pavilion in 1885. Contemporary accounts noted: One of the most famous of these new palaces of pleasure in the West End was the Empire Leicester Square, built as a theatre in 1884 but acquiring a music hall licence in 1887. Like the nearby Alhambra this theatre appealed to the men of leisure by featuring alluring ballet dancers, and had a notorious promenade which was the resort of courtesans. Another spectacular example of the new variety theatre was the Tivoli in the Strand built 1888–90 in an eclectic neo-Romanesque style with Baroque and Moorish-Indian embellishments. " The Tivoli" became a brand name for music-halls all over the British Empire. During 1892, the Royal English Opera House, which had been a financial failure in Shaftesbury Avenue, applied for a music hall licence and was converted by Walter Emden into a grand music hall and renamed the Palace Theatre of Varieties, managed by Charles Morton. Denied by the newly created LCC permission to construct the promenade, which was such a popular feature of the Empire and Alhambra, the Palace compensated in the way of adult entertainment by featuring apparently nude women intableaux vivants

A (; often shortened to ; ; ) is a static scene (performing arts), scene containing one or more actors or models. They are stationary and silent, usually in costume, carefully posed, with props and/or theatrical scenery, scenery, and may be s ...

, though the concerned LCC hastened to reassure patrons that the girls who featured in these displays were actually wearing flesh-toned body stockings and were not naked at all.

One of the grandest of these new halls was the Coliseum Theatre built by Oswald Stoll

Sir Oswald Stoll (né Gray; 20 January 1866 – 9 January 1942) was an Australian-born British theatre manager and the co-founder of the Stoll Moss Group theatre company. He also owned Cricklewood Studios and film production company Stoll Pi ...

in 1904 at the bottom of St Martin's Lane

St Martin's Lane is a street in the City of Westminster, which runs from the church of St Martin-in-the-Fields, after which it is named, near Trafalgar Square northwards to Long Acre. At its northern end, it becomes Monmouth Street, London, Mo ...

. This was followed by the London Palladium

The London Palladium () is a Grade II* West End theatre located on Argyll Street, London, in Soho. The theatre was designed by Frank Matcham and opened in 1910. The auditorium holds 2,286 people. Hundreds of stars have played there, many wit ...

(1910) in Argyll Street

Argyll Street is a street in the Soho district of Central London. It links Great Marlborough Street to the south to Oxford Street in the north and is connected to Regent Street to the west by Little Argyll Street. Historically it was sometimes w ...

. Both were designed by the prolific Frank Matcham. As music hall grew in popularity and respectability, and as the licensing authorities exercised ever firmer regulation, the original arrangement of a large hall with tables at which drink was served, changed to that of a drink-free auditorium

An auditorium is a room built to enable an audience to hear and watch performances. For movie theaters, the number of auditoriums is expressed as the number of screens. Auditoriums can be found in entertainment venues, community halls, and t ...

. The acceptance of music hall as a legitimate cultural form was established by the first ''Royal Variety Performance

The ''Royal Variety Performance'' is a televised variety show held annually in the United Kingdom to raise money for the Royal Variety Charity (of which King Charles III is life-patron). It is attended by senior members of the British royal ...

'' before King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until Death and state funeral of George V, his death in 1936.

George w ...

during 1912 at the Palace Theatre. However, consistent with this new respectability the best-known music hall entertainer of the time, Marie Lloyd, was not invited, being deemed too "saucy" for presentation to the monarchy.

'Music Hall War' of 1907

The development of syndicates controlling a number of theatres, such as the Stoll circuit, increased tensions between employees and employers. On 22 January 1907, a dispute between artists, stage hands and managers of the Holborn Empire worsened. Strikes in other London and suburban halls followed, organised by the Variety Artistes' Federation. The strike lasted for almost two weeks and was known as the ''Music Hall War''. It became extremely well known, and was advocated enthusiastically by the main spokesmen of the trade union and Labour movement –

The development of syndicates controlling a number of theatres, such as the Stoll circuit, increased tensions between employees and employers. On 22 January 1907, a dispute between artists, stage hands and managers of the Holborn Empire worsened. Strikes in other London and suburban halls followed, organised by the Variety Artistes' Federation. The strike lasted for almost two weeks and was known as the ''Music Hall War''. It became extremely well known, and was advocated enthusiastically by the main spokesmen of the trade union and Labour movement – Ben Tillett

Benjamin Tillett (11 September 1860 – 27 January 1943) was a British socialist, trade union leader and politician. He was a leader of the "new unionism" of 1889, that focused on organizing unskilled workers. He played a major role in foundin ...

and Keir Hardie for example. Picket lines were organized outside the theatres by the artistes, while in the provinces theatre management attempted to oblige artistes to sign a document promising never to join a trade union.

The strike ended in arbitration, which satisfied most of the main demands, including a minimum wage and maximum working week for musicians.

Several music hall entertainers such as Marie Dainton, Marie Lloyd, Arthur Roberts, Joe Elvin and Gus Elen were strong advocates of the strike, though they themselves earned enough not to be concerned personally in a material sense. Lloyd explained her advocacy:

Recruiting

World War I may have been the high-water mark of music hall popularity. The artists and composers threw themselves into rallying public support and enthusiasm for the war effort. Patriotic music hall compositions such as "Keep the Home Fires Burning"1914

, "Pack up Your Troubles"

1915

, " It's a Long Way to Tipperary"

1914

and " We Don't Want to Lose You (But We Think You Ought To Go)"

1914

, were sung by music hall audiences, and sometimes by soldiers in the trenches. Many songs promoted recruitment ("All the boys in khaki get the nice girls", 1915); others satirised particular elements of the war experience. "What did you do in the Great war, Daddy"

1919

criticised profiteers and slackers; Vesta Tilley's "I've got a bit of a blighty one"

1916

showed a soldier delighted to have a wound just serious enough to be sent home. The rhymes give a sense of grim humour ("When they wipe my face with sponges / and they feed me on

blancmange

Blancmange (, from , ) is a sweet dessert popular throughout Europe commonly made with milk or cream, and sugar, thickened with rice flour, gelatin, corn starch, or Chondrus crispus, Irish moss (a source of carrageenan), and often flavoured wit ...

s / I'm glad I've got a bit of a blighty one").

Tilley became more popular than ever during this time, when she and her husband, Walter de Frece

Sir Abraham Walter de Frece (7 October 1870 – 7 January 1935) was a British theatre impresario, and later Conservative Party politician, who served as a Member of Parliament (MP) from 1920 to 1931. His wife was the celebrated male impersonat ...

, managed a military recruitment drive. In the guise of characters like 'Tommy in the Trench' and 'Jack Tar Home from Sea', Tilley performed songs such as "The army of today's all right" and "Jolly Good Luck to the Girl who Loves a Soldier". This is how she got the nickname ''Britain's best recruiting sergeant'' – young men were sometimes asked to join the army on stage during her show. She also performed in hospitals and sold war bond

War bonds (sometimes referred to as victory bonds, particularly in propaganda) are Security (finance)#Debt, debt securities issued by a government to finance military operations and other expenditure in times of war without raising taxes to an un ...

s. Her husband was knight

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of a knighthood by a head of state (including the pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church, or the country, especially in a military capacity.

The concept of a knighthood ...

ed in 1919 for his own services to the war effort, and Tilley became Lady de Frece.

Once the reality of war began to sink home, the recruiting songs all but disappeared – the Greatest Hits collection for 1915 published by top music publisher Francis and Day contains no recruitment songs. After conscription was brought in 1916, songs dealing with the war spoke mostly of the desire to return home. Many also expressed anxiety about the new roles women were taking in society.

Possibly the most notorious of music hall songs from the First World War was " Oh! It's a lovely war"1917

, popularised by male impersonator Ella Shields.

Decline

Music hall continued during theinterwar period

In the history of the 20th century, the interwar period, also known as the interbellum (), lasted from 11 November 1918 to 1 September 1939 (20 years, 9 months, 21 days) – from the end of World War I (WWI) to the beginning of World War II ( ...

, no longer the single dominant form of popular entertainment in Britain. The improvement of cinema, the development of radio, and the cheapening of the gramophone damaged its popularity greatly. It now had to compete with jazz

Jazz is a music genre that originated in the African-American communities of New Orleans, Louisiana, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Its roots are in blues, ragtime, European harmony, African rhythmic rituals, spirituals, h ...

, swing and big band

A big band or jazz orchestra is a type of musical ensemble of jazz music that usually consists of ten or more musicians with four sections: saxophones, trumpets, trombones, and a rhythm section. Big bands originated during the early 1910s and ...

dance music.

In 1914, the London County Council

The London County Council (LCC) was the principal local government body for the County of London throughout its existence from 1889 to 1965, and the first London-wide general municipal authority to be directly elected. It covered the area today ...

(LCC) enacted that drinking be banished from the auditorium into a separate bar and, during 1923, the separate bar was abolished by parliamentary decree. The exemption of the theatres from this latter act prompted some critics to denounce this legislation as an attempt to deprive the working classes of their pleasures, as a form of social control, whilst sparing the supposedly more responsible upper classes who patronised the theatres (though this could be due to the licensing restrictions brought about due to the Defence of the Realm Act 1914, which also applied to public houses). Even so, the music hall gave rise to such major stars as George Formby

George Formby, (born George Hoy Booth; 26 May 1904 – 6 March 1961), was an English actor, singer-songwriter and comedian who became known to a worldwide audience through his films of the 1930s and 1940s. On stage, screen and record he ...

, Gracie Fields

Dame Gracie Fields (born Grace Stansfield; 9 January 189827 September 1979) was a British actress, singer and comedian. A star of cinema and music hall, she was one of the top ten film stars in Britain during the 1930s and was considered the h ...

, Max Miller, Will Hay, and Flanagan and Allen during this period.

In the mid-1950s, rock and roll

Rock and roll (often written as rock & roll, rock-n-roll, and rock 'n' roll) is a Genre (music), genre of popular music that evolved in the United States during the late 1940s and early 1950s. It Origins of rock and roll, originated from African ...

, whose performers initially topped music hall bills, attracted a young audience who had little interest in the music hall acts, while driving the older audience away. The final demise was competition from television, which grew popular after the Queen's coronation was televised. Some music halls tried to retain an audience by putting on striptease

A striptease is an erotic or exotic dance in which the performer gradually undresses, either partly or completely, in a seductive and sexually suggestive manner. The person who performs a striptease is commonly known as a "stripper", "exotic d ...

acts. In 1957, the playwright John Osborne

John James Osborne (12 December 1929 – 24 December 1994) was an English playwright, screenwriter, actor, and entrepreneur, who is regarded as one of the most influential figures in post-war theatre. Born in London, he briefly worked as a jo ...

delivered this elegy:

Moss Empires

Moss Empires was a company formed in Edinburgh in 1899, from the merger of the theatre companies owned by Sir Edward Moss, Richard Thornton and Sir Oswald Stoll. This created the largest chain of variety theatres and music halls in the United ...

, the largest British music hall chain, closed the majority of its theatres in 1960, closely followed by the death of music hall stalwart Max Miller in 1963, prompting one contemporary to write that: "Music-halls ... died this afternoon when they buried Max Miller". Miller himself had sometimes said that the genre would die with him. Many music hall performers, unable to find work, fell into poverty; some did not even have a home, having spent their working lives living in digs between performances.

Stage and film musicals, however, continued to be influenced by the music hall idiom, including '' Oliver!'', '' Dr Dolittle'' and ''My Fair Lady

''My Fair Lady'' is a musical theatre, musical with a book and lyrics by Alan Jay Lerner and music by Frederick Loewe. The story, based on George Bernard Shaw's 1913 play ''Pygmalion (play), Pygmalion'' and on the Pygmalion (1938 film), 1938 film ...

''. The BBC

The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is a British public service broadcaster headquartered at Broadcasting House in London, England. Originally established in 1922 as the British Broadcasting Company, it evolved into its current sta ...

series '' The Good Old Days'', which ran for thirty years, recreated the music hall for the modern audience, and the '' Paul Daniels Magic Show'' allowed several speciality acts a television presence from 1979 to 1994. Aimed at a younger audience, but still owing a lot to the music hall heritage, was the late-1970s’ television series, ''The Muppet Show

''The Muppet Show'' is a variety sketch comedy television series created by Jim Henson and starring the Muppets. It is presented as a variety show, featuring recurring sketches and musical numbers interspersed with ongoing plot-lines with ru ...

''.

Music halls of Paris

The music hall was first imported into France in its British form in 1862, but under the French law protecting the state theatres, performers could not wear costumes or recite dialogue, something only allowed in theaters. When the law changed in 1867, the Paris music hall flourished, and a half-dozen new halls opened, offering acrobats, singers, dancers, magicians, and trained animals. The first Paris music hall built specially for that purpose was the Folies-Bergere (1869); it was followed by theMoulin Rouge

Moulin Rouge (, ; ) is a cabaret in Paris, on Boulevard de Clichy, at Place Blanche, the intersection of, and terminus of Rue Blanche.

In 1889, the Moulin Rouge was co-founded by Charles Zidler and Joseph Oller, who also owned the Olympia (Par ...

(1889), the Alhambra

The Alhambra (, ; ) is a palace and fortress complex located in Granada, Spain. It is one of the most famous monuments of Islamic architecture and one of the best-preserved palaces of the historic Muslim world, Islamic world. Additionally, the ...

(1866), the first to be called a music hall, and the Olympia (1893). The ''Printania'' (1903) was a music-garden, open only in summer, with a theater, restaurant, circus, and horse-racing. Older theaters also transformed themselves into music halls, including the Bobino (1873), the Bataclan (1864), and the Alcazar (1858). At the beginning, music halls offered dance reviews, theater and songs, but gradually songs and singers became the main attraction.

Paris music halls all faced stiff competition in the

Paris music halls all faced stiff competition in the interwar period

In the history of the 20th century, the interwar period, also known as the interbellum (), lasted from 11 November 1918 to 1 September 1939 (20 years, 9 months, 21 days) – from the end of World War I (WWI) to the beginning of World War II ( ...

from the most popular new form of entertainment, the cinema. They responded by offering more complex and lavish shows. In 1911, the Olympia had introduced the giant stairway as a set for its productions, an idea copied by other music halls. Gaby Deslys rose in popularity and created, with her dance partner Harry Pilcer, her most famous dance ''The Gaby Glide''. The singer Mistinguett made her debut the Casino de Paris in 1895, and continued to appear regularly in the 1920s and 1930s at the Folies Bergère, Moulin Rouge

Moulin Rouge (, ; ) is a cabaret in Paris, on Boulevard de Clichy, at Place Blanche, the intersection of, and terminus of Rue Blanche.

In 1889, the Moulin Rouge was co-founded by Charles Zidler and Joseph Oller, who also owned the Olympia (Par ...

and Eldorado. Her risqué routines captivated Paris, and she became one of the most highly-paid and popular French entertainers of her time.

One of the most popular entertainers in Paris during the period was the American singer

One of the most popular entertainers in Paris during the period was the American singer Josephine Baker

Freda Josephine Baker (; June 3, 1906 – April 12, 1975), naturalized as Joséphine Baker, was an American and French dancer, singer, and actress. Her career was centered primarily in Europe, mostly in France. She was the first Black woman to s ...

. Baker sailed to Paris, France. She first arrived in Paris in 1925 to perform in a show called '' La Revue Nègre'' at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées. She became an immediate success for her erotic dancing

Eroticism () is a quality that causes sexual feelings, as well as a philosophical contemplation concerning the aesthetics of sexual desire, sensuality, and romantic love. That quality may be found in any form of artwork, including painting, sculp ...

, and for appearing practically nude on stage. After a successful tour of Europe, she returned to France to star at the Folies Bergère. Baker performed the 'Danse sauvage,' wearing a costume consisting of a skirt made of a string of artificial bananas.

The music-halls suffered growing hardships in the 1930s. The Olympia was converted into a movie theater, and others closed. Others however continued to thrive. In 1937 and 1930, the Casino de Paris presented shows with Maurice Chevalier, who had already achieved success as an actor and singer in Hollywood.

In 1935, a twenty-year old singer named Édith Piaf was discovered in the Pigalle by nightclub owner Louis Leplée, whose club, Le Gerny, off the

The music-halls suffered growing hardships in the 1930s. The Olympia was converted into a movie theater, and others closed. Others however continued to thrive. In 1937 and 1930, the Casino de Paris presented shows with Maurice Chevalier, who had already achieved success as an actor and singer in Hollywood.

In 1935, a twenty-year old singer named Édith Piaf was discovered in the Pigalle by nightclub owner Louis Leplée, whose club, Le Gerny, off the Champs-Élysées

The Avenue des Champs-Élysées (, ; ) is an Avenue (landscape), avenue in the 8th arrondissement of Paris, France, long and wide, running between the Place de la Concorde in the east and the Place Charles de Gaulle in the west, where the Arc ...

, was frequented by the upper and lower classes alike. He persuaded her to sing despite her extreme nervousness. Leplée taught her the basics of stage presence and told her to wear a black dress, which became her trademark apparel. Leplée ran an intense publicity campaign leading up to her opening night, attracting the presence of many celebrities, including Maurice Chevalier. Her nightclub appearance led to her first two records produced that same year, and the beginning of her career.

Competition from movies and television largely brought an end to the Paris music hall. However, a few still flourish, with tourists as their primary audience. Major music halls include the Folies-Bergere, Crazy Horse Saloon, Casino de Paris, Olympia, and Moulin Rouge

Moulin Rouge (, ; ) is a cabaret in Paris, on Boulevard de Clichy, at Place Blanche, the intersection of, and terminus of Rue Blanche.

In 1889, the Moulin Rouge was co-founded by Charles Zidler and Joseph Oller, who also owned the Olympia (Par ...

.

History of the songs

The musical forms most associated with music hall evolved in part from traditional folk song and songs written for popular drama, becoming by the 1850s a distinct musical style. Subject matter became more contemporary and humorous, and accompaniment was provided by larger house-orchestras, as increasing affluence gave the lower classes more access to commercial entertainment, and to a wider range of musical instruments, including the piano. The consequent change in musical taste from traditional to more professional forms of entertainment, arose in response to the rapid industrialisation andurbanisation

Urbanization (or urbanisation in British English) is the population shift from rural to urban areas, the corresponding decrease in the proportion of people living in rural areas, and the ways in which societies adapt to this change. It can also ...

of previously rural populations in Britain during the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution, sometimes divided into the First Industrial Revolution and Second Industrial Revolution, was a transitional period of the global economy toward more widespread, efficient and stable manufacturing processes, succee ...

. The newly created urban communities, cut off from their cultural roots, required new and readily accessible forms of entertainment.''The Songs of the Music Hall'' (Music Hall CDs)accessed 2 November 2007 Music halls were originally tavern rooms which provided entertainment, in the form of music and speciality acts, for their patrons. By the middle years of the nineteenth century, the first purpose-built music halls were being built in London. The halls created a demand for new and catchy popular songs, that could no longer be met from the traditional

folk song

Folk music is a music genre that includes #Traditional folk music, traditional folk music and the Contemporary folk music, contemporary genre that evolved from the former during the 20th-century folk revival. Some types of folk music may be ca ...

repertoire. Professional songwriters were enlisted to fill the gap.

The emergence of a distinct music hall style can be credited to a fusion of musical influences. Music hall songs needed to gain and hold the attention of an often jaded and unruly urban audience. In America, from the 1840s, Stephen Foster

Stephen Collins Foster (July 4, 1826January 13, 1864), known as "the father of American music", was an American composer known primarily for his parlour music, parlour and Folk music, folk music during the Romantic music, Romantic period. He wr ...

had reinvigorated folk song with the admixture of Negro spiritual to produce a new type of popular song. Songs like "Old Folks at Home

"Old Folks at Home" (also known as " Swanee River") is a folk song written by Stephen Foster in 1851. Since 1935, it has been the official state song of Florida, although in 2008 the original lyrics were revised. It is Roud Folk Song Index ...

" (1851) and " Oh, Dem Golden Slippers" (James Bland, 1879]) spread round the globe, taking with them the idiom and appurtenances of the minstrel show, minstrel song. Typically, a music hall song consists of a series of verses sung by the performer alone, and a repeated chorus which carries the principal melody, and in which the audience is encouraged to join.

In Britain, the first music hall songs often promoted the alcoholic wares of the owners of the halls in which they were performed. Songs like "Glorious Beer", and the first major music hall success, " Champagne Charlie" (1867) had a major influence in establishing the new art form. The tune of "Champagne Charlie" became used for

In Britain, the first music hall songs often promoted the alcoholic wares of the owners of the halls in which they were performed. Songs like "Glorious Beer", and the first major music hall success, " Champagne Charlie" (1867) had a major influence in establishing the new art form. The tune of "Champagne Charlie" became used for The Salvation Army

The Salvation Army (TSA) is a Protestantism, Protestant Christian church and an international charitable organisation headquartered in London, England. It is aligned with the Wesleyan-Holiness movement. The organisation reports a worldwide m ...

hymn "Bless His Name, He Sets Me Free" (1881). When asked why the tune should be used like this, William Booth is said to have replied "Why should the devil have all the good tunes?" According to The Salvation Army, "The adoption of such music was soon put to full use. On Saturday afternoon, May 13, 1882, the congregation at the opening of the Clapton Congress Hall joined heartily in the chorus of Gipsy Smith's solo, 'O the Blood of Jesus cleanses white as snow' to the music of 'I traced her little footsteps in the snow'. There were no qualms of conscience. Many people gathered there knew none of the hymn tunes

A hymn tune is the melody of a musical composition to which a hymn text is sung. Musically speaking, a hymn is generally understood to have four-part harmony, four-part (or more) harmony, a fast harmonic rhythm (chords change frequently), with o ...

or gospel melodies used in the churches; the music hall had been their melody school."

Music hall songs were often composed with their working class audiences in mind. Songs like " My Old Man (Said Follow the Van)", " Wot Cher! Knocked 'em in the Old Kent Road", and " Waiting at the Church", expressed in melodic form situations with which the urban poor were familiar. Music hall songs could be romantic, patriotic, humorous or sentimental, as the need arose. The most popular music hall songs became the basis for the pub songs of the typical Cockney

Cockney is a dialect of the English language, mainly spoken in London and its environs, particularly by Londoners with working-class and lower middle class roots. The term ''Cockney'' is also used as a demonym for a person from the East End, ...

" knees up". Although a number of songs show a sharply ironic and knowing view of working-class life, there were, too, those which were repetitive, derivative, written quickly and sung to make a living rather than a work of art.

Famous music hall songs

* " A Little of What You Fancy Does You Good* ( George Arthurs, Fred W. Leigh), sung by Marie Lloyd

* " Any Old Iron" ( Charles Collins; Terry Sheppard) sung by Harry Champion in 1911.

* " Ask a P'liceman" (

* " A Little of What You Fancy Does You Good* ( George Arthurs, Fred W. Leigh), sung by Marie Lloyd

* " Any Old Iron" ( Charles Collins; Terry Sheppard) sung by Harry Champion in 1911.

* " Ask a P'liceman" (E. W. Rogers

Edward William Rogers (1864– 21 February 1913) was an English songwriter for music hall performers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Biography

He was born in Newington, London, and in the 1880s started appearing on the music hall stage ...

and A. E. Durandeau) sung by James Fawn

* " Belgium Put the Kibosh on the Kaiser" (Alf Ellerton) sung by Mark Sheridan.

* " Boiled Beef and Carrots" (Charles Collins and Fred Murray) sung by Harry Champion.

* " The Boy I Love is Up in the Gallery" ( George Ware) sung by Nelly Power, and Marie Lloyd.

* " Burlington Bertie from Bow" ( William Hargreaves) sung by Ella Shields.

* " Daddy Wouldn't Buy Me a Bow Wow" ( Joseph Tabrar) sung by Vesta Victoria.

* " Daisy Bell (Bicycle Built for Two)" ( Harry Dacre) sung by Katie Lawrence.

* " Don't Dilly Dally on the Way" (Charles Collins and Fred W. Leigh) sung by Marie Lloyd.

* " Down at the Old Bull and Bush" ( Harry von Tilzer; Andrew B. Sterling) sung by Florrie Forde.

* " Every Little Movement (Has a Meaning All Its Own)" (J. C. Moore; Fred E. Cliffe) sung by Marie Lloyd.

* " Good-bye-ee!" ( R. P. Weston; Bert Lee) sung by Florrie Forde and Daisy Wood.

* " Has Anybody Here Seen Kelly?" ( C. W. Murphy and Will Letters) sung by Florrie Forde.

* " Hello, Hello, Who's Your Lady Friend?" ( Harry Fragson; Worton David; Bert Lee) sung by Harry Fragson, Mark Sheridan, etc.

* " I Belong to Glasgow", written and performed by Will Fyffe.

* " I Do Like to Be Beside the Seaside" (John A. Glover-Kind) sung by Mark Sheridan.

* " I'm Henery the Eighth, I Am" (1910) (Fred Murray and R. P. Weston) sung by Harry Champion.

* " It's a Long Way to Tipperary" (1912) ( Jack Judge and Harry Williams) sung by John McCormack.

* " Let's All Go Down the Strand" (

* " I Do Like to Be Beside the Seaside" (John A. Glover-Kind) sung by Mark Sheridan.

* " I'm Henery the Eighth, I Am" (1910) (Fred Murray and R. P. Weston) sung by Harry Champion.

* " It's a Long Way to Tipperary" (1912) ( Jack Judge and Harry Williams) sung by John McCormack.

* " Let's All Go Down the Strand" (Harry Castling

Henry Castling (19 April 1865 – 26 December 1933) was an English lyricist of music hall songs.

Biography

Castling was born in Newington, London, the son of a street musician. He began writing songs in the 1890s, often collaborating on both ...

and C. W. Murphy) sung by Charles R. Whittle.

* " Lily of Laguna" (Leslie Stuart) sung by Eugene Stratton, and later G. H. Elliott.

* " The Daring Young Man on the Flying Trapeze" ( George Leybourne; Gaston Lyle; arr. Alfred Lee) sung by George Leybourne.

* " The Man Who Broke the Bank at Monte Carlo" (1891) ( Fred Gilbert) sung by Charles Coborn.

* " My Old Dutch" ( Albert Chevalier; Charles Ingle) sung by Albert Chevalier.

* " Nellie Dean" ( Henry W. Armstrong) sung by Gertie Gitana.

* " Oh! Mr Porter" ( George Le Brunn and Thomas Le Brunn) sung by Marie Lloyd, and Norah Blaney.

* " Pack Up Your Troubles in Your Old Kit-Bag" ( Felix Powell) sung by Florrie Forde.

* " Ship Ahoy! (All the Nice Girls Love a Sailor)", performed by Hetty King

* " Ta-ra-ra Boom-de-ay" (Harry J. Sayers) sung by Lottie Collins.

* " Waiting at the Church" ( Henry E. Pether; Fred W. Leigh) sung by Vesta Victoria.

* " Where Did You Get That Hat?" ( Joseph J. Sullivan, 1888; words rewritten 1901 by James Rolmaz) sung by J. C. Heffron (1857–1934)

Music hall songwriters

* Fred Albert (1844–1886), "topical vocalist" who wrote his own material; titles included "Bradshaw's Guide" and "The Mad Butcher"; popular in the 1870s. *Harry Castling

Henry Castling (19 April 1865 – 26 December 1933) was an English lyricist of music hall songs.

Biography

Castling was born in Newington, London, the son of a street musician. He began writing songs in the 1890s, often collaborating on both ...

(1865–1933), lyricist of "Let's All Go Down The Strand" sung by Charles R. Whittle and "Don't Have Any More, Mrs More" sung by Lily Morris.

* Harry Clifton (1832–1872), prolific singer-songwriter whose titles include " Polly Perkins of Paddingion Green".

* Charles Collins (1874–1923), composer of songs including " Boiled Beef and Carrots", " Any Old Iron", and " Don't Dilly Dally on the Way".

* Harry Dacre (1857–1922), composer of " Daisy Bell (Bicycle Built for Two)" (1892) and "I'll Be Your Sweetheart" (1899).

* Stephen Collins Foster (1826–1864), American parlour music and minstrel

A minstrel was an entertainer, initially in medieval Europe. The term originally described any type of entertainer such as a musician, juggler, acrobat, singer or fool; later, from the sixteenth century, it came to mean a specialist enter ...

composer.

* Noel Gay

Reginald Moxon Armitage (15 July 1898 – 4 March 1954) known professionally as Noel Gay. was a British composer of popular music of the 1930s and 1940s whose output comprised 45 songs as well as the music for 28 films and 26 London shows. She ...

(1898–1954), composer of "The Lambeth Walk

"The Lambeth Walk" is a song from the 1937 musical theater, musical ''Me and My Girl'' (with book and lyrics by Douglas Furber and L. Arthur Rose and music by Noel Gay). The song takes its name from a local street, Lambeth Walk, once notable for i ...

" (1937) and " Leaning on a Lamp-post" (1937).

* Fred Godfrey (1880–1953), composer of "Who Were You With Last Night?" sung by Mark Sheridan, and "Now I Have To Call Him Father" sung by Vesta Victoria.

* William Hargreaves (1880–1941), wrote the 1915 parody " Burlington Bertie from Bow" for his wife Ella Shields.

* F. Clifford Harris (1875-1949), lyricist (working often with James W. Tate

James William Tate (30 July 1875 – 5 February 1922) was an English songwriter, accompanist, composer and producer of revues and pantomimes in the early years of the 20th century.

After working in the for five years, in 1897 Tate became Musi ...

) of "I Was A Good Little Girl" and "A Broken Doll", both sung by Clarice Mayne and That.

* Tom Hudson (1791–1844), writer and performer of comic songs

* G. W. Hunt (c.1837–1904), prolific composer and lyricist best known for G. H. MacDermott's "War Song" ("By Jingo if we do...")

* Harry Lauder (1870–1950), writer of his own popular songs, "I Love A Lassie" and "Stop yer Tickling, Jock".

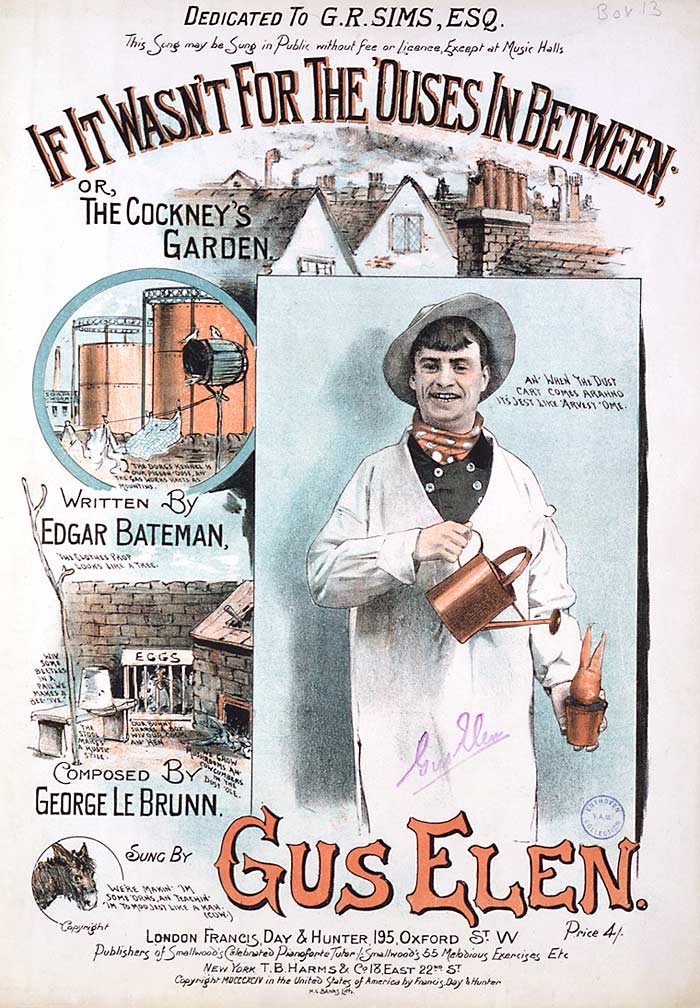

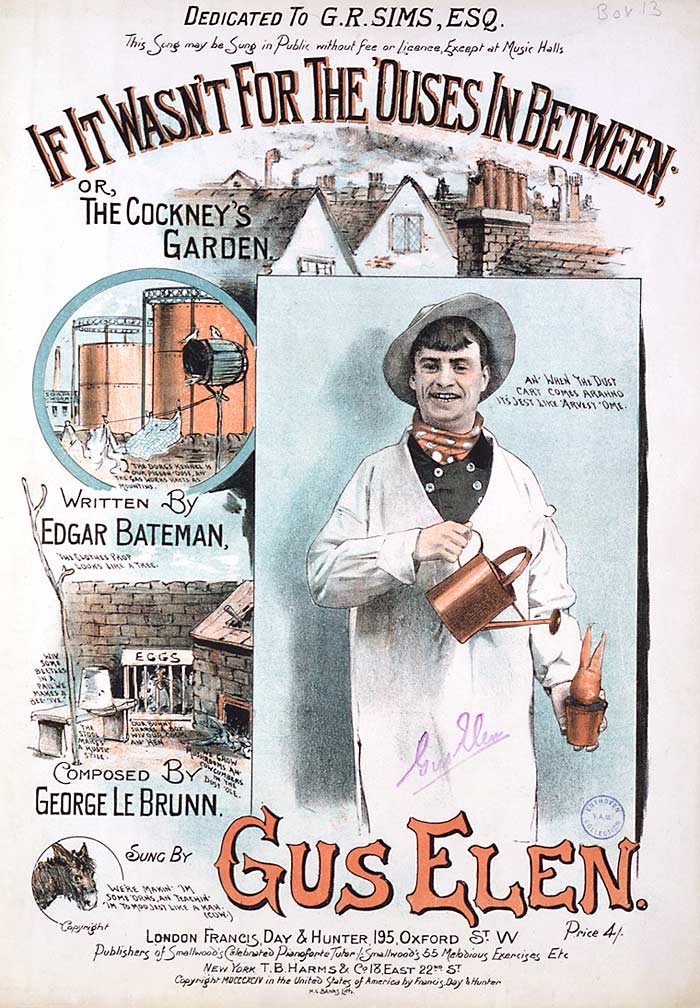

* George Le Brunn (1864–1905), composer of " Oh! Mr Porter" sung by Marie Lloyd, and "If It Wasn't for the 'Ouses in Between" and "It's a Great Big Shame" sung by Gus Elen.

* Bert Lee (1880–1946), composer of " Good-bye-ee!" sung by Florrie Forde and Daisy Wood, and "Hello Hello, Who’s Your Lady Friend?" sung by Mark Sheridan.

* Fred W. Leigh (1871–1924), lyricist of " The Galloping Major", " Waiting at the Church", " A Little of What You Fancy Does You Good" and " Don't Dilly Dally on the Way", among others.Richard Anthony Baker, ''British Music Hall: an illustrated history'', Pen & Sword, 2014, , pp.138-140

* Arthur Lloyd (1839–1904), music hall's first prolific singer-songwriter.

* Arthur J. Mills (1872–1919), lyricist of "When I Take My Morning Promenade" sung by Marie Lloyd, and "Ship Ahoy! (All The Nice Girls Love A Sailor)" sung by Hetty King.

* C. W. Murphy (1875–1913), composer of " Has Anybody Here Seen Kelly?" sung by Florrie Forde and "Hello Hello, Who’s Your Lady Friend?" sung by Mark Sheridan.

* Edward W. Rogers (1864–1913), lyricist of " Ask a P'liceman" sung by James Fawn, and composer of Alec Hurley's original "The Lambeth Walk" (1899).

* George Alex Stevens (1875–1954), composer of "On Mother Kelly's Doorstep" sung by Randolph Sutton.

* Bennett Scott (1875–1930), composer of "When I Take My Morning Promenade" sung by Marie Lloyd, and "Ship Ahoy! All the Nice Girls Love a Sailor" sung by Ella Retford.

* Leslie Stuart (1863–1928), composer of " Lily of Laguna" and "Little Dolly Daydream" sung by Eugene Stratton.

* Joseph Tabrar (1857–1931), prolific composer whose titles included " Daddy Wouldn't Buy Me a Bow Wow" sung by Vesta Victoria.

* James W. Tate

James William Tate (30 July 1875 – 5 February 1922) was an English songwriter, accompanist, composer and producer of revues and pantomimes in the early years of the 20th century.

After working in the for five years, in 1897 Tate became Musi ...

(1875–1922) composer of "I Was A Good Little Girl" and "A Broken Doll", both sung by Clarice Mayne and That.

* R. P. Weston (1878–1936), composer of " Good-bye-ee!" sung by Florrie Forde and Daisy Wood, and " I'm Henery the Eighth, I Am" sung by Harry Champion.

* Harry Wincott (1867–1947), composer of "When The Old Dun Cow Caught Fire" sung by Harry Champion, and (arguably) " Mademoiselle from Armentières".

Music hall comedy

The typical music hall comedian was a man or woman, usually dressed in character to suit the subject of the song, or sometimes attired in absurd and eccentric style. Until well into the twentieth century, the acts were essentially vocal, with songs telling a story, accompanied by a minimum of patter. They included a variety of genres, including: * Lion comiques: essentially, men dressed as "toffs", who sang songs about drinking champagne, going to the races, going to the ball, womanising and gambling, and living the life of an aristocrat. * Male and female impersonators, the latter more in the style of a pantomime dame than a moderndrag queen

A drag queen is a person, usually male, who uses Drag (entertainment), drag clothing and makeup to imitate and often exaggerate Femininity, female gender signifiers and gender roles for entertainment purposes. Historically, drag queens have ...

. Nevertheless, these included some more sophisticated performers such as Vesta Tilley and Ella Shields, whose male impersonations communicated real social commentary.

Music hall impresario Fred Karno developed a form of sketch comedy without dialogue in the 1890s, and in 1904, Karno's Komics produced a new sketch for the Hackney Empire in London called ''Mumming Birds'', which included the pie in the face gag among other new innovations. Immensely popular, it became the longest-running sketch the music halls produced. Charlie Chaplin and Stan Laurel

Stan Laurel ( ; born Arthur Stanley Jefferson; 16 June 1890 – 23 February 1965) was an English comic actor, director and writer who was in the comedy double act, duo Laurel and Hardy. He appeared with his comedy partner Oliver Hardy in 107 sh ...

were among the music hall comedians who worked for Karno, and on the latter Simon Louvish writes, "Chaplin remained the great observer of the absurdity of life's endless struggles, an actor trained with Karno's "Speechless Comedians" to express each thought and attitude in mime."

Speciality acts

The vocal content of the music hall bills, was, from the beginning, accompanied by many other kinds of act, some of them quite weird and wonderful. These were known collectively as ''speciality acts'' (abbreviated to "spesh"), which, over time, have included: * Adagio: essentially a sort of cross between a dance act and ajuggling

Juggling is a physical skill, performed by a juggler, involving the manipulation of objects for recreation, entertainment, art or sport. The most recognizable form of juggling is toss juggling. Juggling can be the manipulation of one object o ...

act, consisting usually of a male dancer who threw a slim, pretty young girl around. Some aspects of modern dance choreography evolved from Adagio acts.

* Aerial acts, of the sort usually seen at the circus

* Animal acts: Talking dogs, flea circuses, and all manner of animals doing tricks.

* Cycling acts: again, a development of a circus act, consisting of either a solo or a troupe of trick cyclists. There was even a seven-piece cycling band called Seven Musical Savonas, who played fifty instruments between them, and Kaufmann's Cycling Beauties, a troupe of girls in Victorian swim wear.

* Drag artists: female entertainers dressed as men, such as Vesta Tilley, Ella Shields, and Hetty King; or male entertainers dressed as women, such as Bert Erroll, Julian Eltinge, Danny La Rue, and Rex Jameson in the character of Mrs Shufflewick

* Electric acts, using the newly discovered phenomenon of static electricity

Static electricity is an imbalance of electric charges within or on the surface of a material. The charge remains until it can move away by an electric current or electrical discharge. The word "static" is used to differentiate it from electric ...

to produce tricks such as lighting gas jets and setting fire to handkerchiefs through the performers fingertips. Dr Walford Bodie (1869/70-1939) was the most notable.

* Escapologists, such as Harry Houdini

Erik Weisz (March 24, 1874 – October 31, 1926), known professionally as Harry Houdini ( ), was a Hungarian-American escapologist, illusionist, and stunt performer noted for his escape acts.

Houdini first attracted notice in vaudeville in ...

.

* Fire eaters and other eating acts, such as eating glass, razor blades, goldfish

The goldfish (''Carassius auratus'') is a freshwater fish in the family Cyprinidae of the order Cypriniformes. It is commonly kept as a pet in indoor aquariums, and is one of the most popular aquarium fish. Goldfish released into the w ...

, etc.

* Juggling

Juggling is a physical skill, performed by a juggler, involving the manipulation of objects for recreation, entertainment, art or sport. The most recognizable form of juggling is toss juggling. Juggling can be the manipulation of one object o ...

and plate spinning acts. Another variation was the Diabolo

The diabolo ( ; commonly misspelled ''diablo'') is a juggling or circus skills, circus juggling prop, prop consisting of an axle () and two cone, cups (hourglass/egg timer shaped) or cylinder, discs derived from the Chinese yo-yo. This object i ...

.

* Knife throwing and sword swallowing. The most spectacular of its time was the Victorina Troupe, who swallowed a sword fired from a rifle.

* Magic acts, such as David Devant.

* A memory act of the type performed by Datas, "the Living Encyclopaedia" (1875–1956).

* Mentalism acts. Commonly a male mentalist, blindfolded on stage, and an attractive female assistant passing among the audience. The assistant would collect objects from the audience, and the mentalist would identify each by "reading" the assistants mind. This was usually accomplished by a clever system of codes and clues from the assistant.

* Mime artist

A mime artist, or simply mime (from Greek language, Greek , , "imitator, actor"), is a person who uses ''mime'' (also called ''pantomime'' outside of Britain), the acting out of a story through body motions without the use of speech, as a the ...

s and impressionists.

* Comic pianist

A pianist ( , ) is a musician who plays the piano. A pianist's repertoire may include music from a diverse variety of styles, such as traditional classical music, jazz piano, jazz, blues piano, blues, and popular music, including rock music, ...

s, such as John Orlando Parry and George Grossmith.

* Puppet

A puppet is an object, often resembling a human, animal or Legendary creature, mythical figure, that is animated or manipulated by a person called a puppeteer. Puppetry is an ancient form of theatre which dates back to the 5th century BC in anci ...

acts, including human puppets and living doll acts.

* Shadow puppet acts.

* Stilt

Stilt is a common name for several species of birds in the family Recurvirostridae, which also includes those known as avocets. They are found in brackish or saline wetlands in warm or hot climates.

They have extremely long legs, hence the grou ...

walkers.

* Strongmen such as Eugen Sandow, and strongwomen such as Joan Rhodes, performing feats of strength.

* Trampoline acts.

* Ventriloquists, or ''Vent'' acts as they were called in the business, such as Fred Russell, Arthur Prince, Frank Travis, Coram (Thomas Mitchell).

* Wild West/Cowboy

A cowboy is an animal herder who tends cattle on ranches in North America, traditionally on horseback, and often performs a multitude of other ranch-related tasks. The historic American cowboy of the late 19th century arose from the ''vaquero'' ...

acts.

* Wrestling

Wrestling is a martial art, combat sport, and form of entertainment that involves grappling with an opponent and striving to obtain a position of advantage through different throws or techniques, within a given ruleset. Wrestling involves di ...

and jujitsu exhibitions were both popular speciality acts, forming the basis of modern professional wrestling

Professional wrestling, often shortened to either pro wrestling or wrestling,The term "wrestling" is most often widely used to specifically refer to modern scripted professional wrestling, though it is also used to refer to Real life, real- ...

.

Music hall performers

* Fred Albert (1843–1886)

* Fred Barnes (1885–1938)

* Ida Barr (1882–1967)

* Bessie Bellwood (1856–1896)

* Herbert Campbell (1844–1904)

* Aimée Campton (1882–1930)

* Kate Carney (1869–1950)

* Harry Champion (1866–1942)

* Charles Chaplin Sr. (1863–1901)

*

* Fred Albert (1843–1886)

* Fred Barnes (1885–1938)

* Ida Barr (1882–1967)

* Bessie Bellwood (1856–1896)

* Herbert Campbell (1844–1904)

* Aimée Campton (1882–1930)

* Kate Carney (1869–1950)

* Harry Champion (1866–1942)

* Charles Chaplin Sr. (1863–1901)

* Charlie Chaplin

Sir Charles Spencer Chaplin (16 April 188925 December 1977) was an English comic actor, filmmaker, and composer who rose to fame in the era of silent film. He became a worldwide icon through his screen persona, the Tramp, and is considered o ...

(1889–1977)

* Sydney Chaplin (1885–1965)

* Albert Chevalier (1861–1923)

* George H. Chirgwin (1854–1922)

* Charles Coborn (1852–1945)

* Cullen and Carthy Johnnie Cullen (1868–1929) and Arthur Carthy (1868–1943)

* Johnny Danvers (1860-1939)

* Daisy Dormer (1883–1947)

* Leo Dryden (1864–1939)

* T. E. Dunville (1867–1924)

* Gus Elen (1862–1940)

* Joe Elvin (1862–1935)

* G. H. Elliott (1882–1962)

* Will Evans (1866–1931)

* Florrie Forde (1875–1940)

* George Formby, Sr. (1876–1921)

* Harry Fragson (1869–1913)

* Will Fyffe (1885–1947)

* Charles Godfrey (1851–1900)

* Will Hay (1888–1949)

* Jenny Hill (1848–1896)

* Stanley Holloway (1890–1982)

* Fred Karno (1866–1941)

* Marie Kendall (1873–1964)

* Hetty King (1883–1972)

* R. G. Knowles (1858–1919)

* Lillie Langtry

Emilie Charlotte, Lady de Bathe (née Le Breton, formerly Langtry; 13 October 1853 – 12 February 1929), known as Lillie (or Lily) Langtry and nicknamed "The Jersey Lily", was a British socialite, stage actress and producer.

Born on the isla ...

(1853–1929)

* George Lashwood (1863–1942)

* Sir Harry Lauder (1870–1950)

* Stan Laurel

Stan Laurel ( ; born Arthur Stanley Jefferson; 16 June 1890 – 23 February 1965) was an English comic actor, director and writer who was in the comedy double act, duo Laurel and Hardy. He appeared with his comedy partner Oliver Hardy in 107 sh ...

(1890–1965)

* Katie Lawrence (1868–1913)

* Tom Leamore (1866–1939)

* Dan Leno (1860–1904)

* George Leybourne (1842–1884)

* Marie Loftus (1857–1940)

* Cecilia Loftus (1876–1943)

* Jack Lotto (1857–1944)

* Little Tich (1867–1928)

* Arthur Lloyd (1839–1904)

* Marie Lloyd (1870–1922)

* Adelaide Macarte (1879–1908)

* Cecilia Macarte (1880–)

* Julia Macarte (1878–1958)

* Tom Major-Ball (1879–1962)

* Ernie Mayne (1871–1937)

* Mark Melford (1850–1914)

* George Mozart (1864–1947)

* Jolly John Nash (1828–1901)

* Denise Orme (1885–1960)

* Edmund Payne (1864–1914)

* Jack Pleasants (1875–1924)

* Nelly Power (1854–1887)

* Peggy Pryde (1869–1943)

* Ella Retford (1885–1962)

* Arthur Roberts (1852–1933)

* George Robey

Sir George Edward Wade, Commander of the Order of the British Empire, CBE (20 September 1869 – 29 November 1954),James Harding (music writer), Harding, James"Robey, George" ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University P ...

(1869–1954)

* Malcolm Scott (1872–1929)

* Truly Shattuck (1875–1954)

* Ella Shields (1879–1952)

* Mark Sheridan (1864–1918)

* J. H. Stead (c.1826–1886)

* Eugene Stratton (1861–1918)

* Harry Tate (1872–1940)

* Sam Torr (1849–1923)

* Vesta Tilley (1864–1952)

* Arthur Tracy

Arthur Tracy (born Abba Avrom Tracovutsky; June 25, 1899 – October 5, 1997) was an American vocalist and actor, billed as The Street Singer. His performances in theatre, films and radio, along with his recordings, brought him international f ...

(1899–1997)

* Alfred Vance

Alfred Glanville Vance (born Alfred Peck Stevens; 1839 – 26 December 1888), often known as The Great Vance, was an English music hall singer, regarded as "one of the most important of the early music-hall performers".

Biography

Vance was born ...

(1839–1888)

* Vesta Victoria (1873–1951)

* Fawdon Vokes (1844–1904)

* Fred Vokes (1846–1888)

* Jessie Vokes (1848–1884)

* Rosina Vokes (1854–1894)

* Victoria Vokes (1853–1894)

* Vulcana (1874–1946)

* Harry Weldon (1881–1930)

* Daisy Wood (1877–1961) (and the ''Sisters Lloyd'')

* Billy Williams (1878–1915)

Cultural influences of music hall: Literature, drama, screen, and later music

The music hall has been evoked in many films, plays, TV series, and books. * InJames Joyce

James Augustine Aloysius Joyce (born James Augusta Joyce; 2 February 1882 – 13 January 1941) was an Irish novelist, poet, and literary critic. He contributed to the modernist avant-garde movement and is regarded as one of the most influentia ...

's short story " The Boarding House" (1914), Mrs Mooney's boarding-house in Hardwicke Street accommodates "occasionally (...) ''artistes'' from the music halls". The Sunday night "reunions" with Jack Mooney in the drawing-room create a certain atmosphere.

* About half of the film '' Those Were the Days'' (1934) is set in a music hall. It was based on a farce by Pinero and features the music hall acts of Lily Morris, Harry Bedford, the gymnastGaston & Andre

G. H. Elliott, Sam Curtis, and Frank Boston & Betty. * A music hall with a 'memory man' act provides a pivotal plot device in the classic 1935

Alfred Hitchcock