Mushin (mental state) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

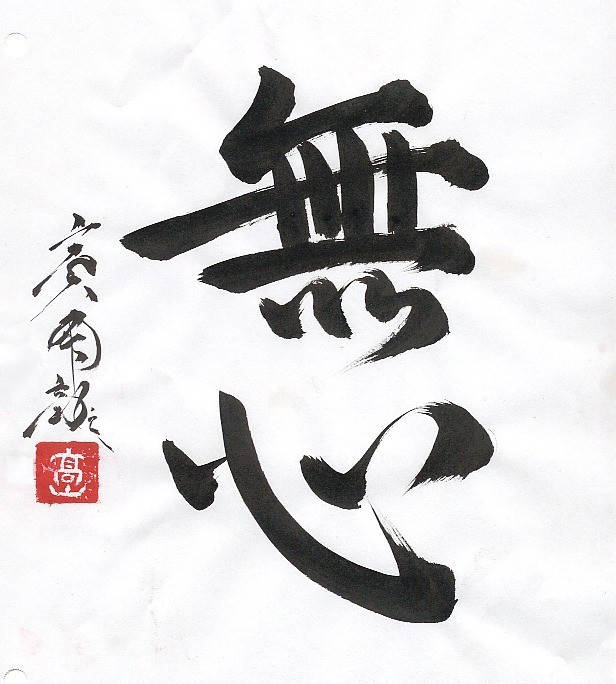

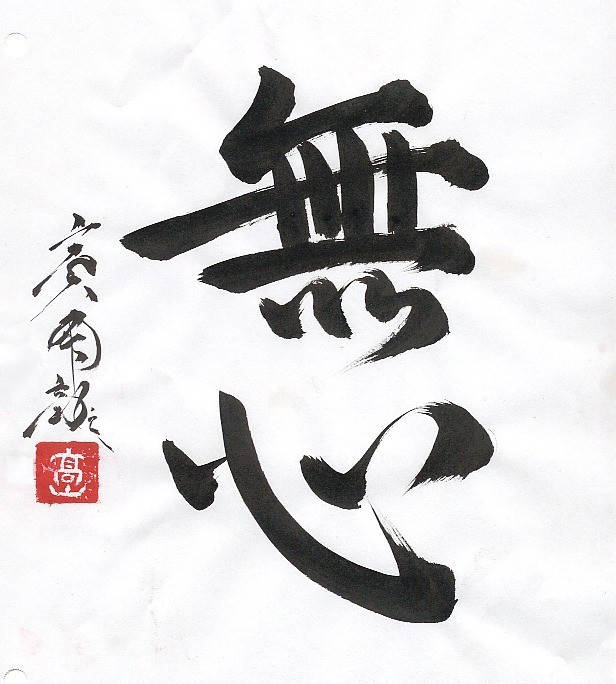

No-mind (Chinese: , pinyin: ''wuxin''; Japanese: ''mushin'';

No-mind (Chinese: , pinyin: ''wuxin''; Japanese: ''mushin'';

The term no mind (wuxin) was first discussed by Chinese exegetes of the Prajñaparamita sutras, who understood the term as a gloss on emptiness. These commentators were known as "the school of no-mind" (, xinwu zong) and included figures like Zhi Mindu (fl. 326).

The influential '' Mahayana Awakening of Faith'' also mentions no-mind or no-thought (though it uses the term ''wu-nien'', ) in relation to its doctrine of the ultimate One Mind, which is pure, without thought, immutable, and unchanging:

The term no mind (wuxin) was first discussed by Chinese exegetes of the Prajñaparamita sutras, who understood the term as a gloss on emptiness. These commentators were known as "the school of no-mind" (, xinwu zong) and included figures like Zhi Mindu (fl. 326).

The influential '' Mahayana Awakening of Faith'' also mentions no-mind or no-thought (though it uses the term ''wu-nien'', ) in relation to its doctrine of the ultimate One Mind, which is pure, without thought, immutable, and unchanging:

How Do You Think Not Thinking? Just Think

Barry Magid Japanese martial arts terminology Zen

No-mind (Chinese: , pinyin: ''wuxin''; Japanese: ''mushin'';

No-mind (Chinese: , pinyin: ''wuxin''; Japanese: ''mushin''; Sanskrit

Sanskrit (; stem form ; nominal singular , ,) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan languages, Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in northwest South Asia after its predecessor languages had Trans-cultural ...

: ''acitta, acittika,'' ''acintya''; ''nirvikalpa'') is a mental state

A mental state, or a mental property, is a state of mind of a person. Mental states comprise a diverse class, including perception, pain/pleasure experience, belief, desire, intention, emotion, and memory. There is controversy concerning the exact ...

that is important in East Asian religions, Asian culture

The culture of Asia encompasses the collective and diverse customs and traditions of art, architecture, music, literature, lifestyle, philosophy, food, politics and religion that have been practiced and maintained by the numerous ethnic g ...

, and the arts

The arts or creative arts are a vast range of human practices involving creativity, creative expression, storytelling, and cultural participation. The arts encompass diverse and plural modes of thought, deeds, and existence in an extensive ...

. The idea is discussed in classic Zen Buddhist texts and has been described as "the experience of an instantaneous severing of thought that occurs in the course of a thoroughgoing pursuit of a Buddhist meditative exercise". It is not necessarily a total absence of thinking however, instead, it can refer to an absence of clinging, conceptual proliferation, or being stuck in thought. Chinese Buddhist texts also link this experience with Buddhist metaphysical concepts, like buddha-nature and Dharmakaya. The term is also found in Daoist literature, including the ''Zhuangzi''.

This idea eventually influenced other aspects of Asian culture and the arts. Thus, the effortless state of "no mind" is one which is cultivated by artists, poets, craftsmen, performers, and trained martial artists, who may or may not be associated with Buddhism or Daoism.Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki, Manual Of Zen Buddhism, p. 80, http://www.buddhanet.net/pdf_file/manual_zen.pdf In this context, the term may have no religious connotations (or it may retain it, depending on the artist's own context), and is used to mean "the state at which a master is so at one with his art that his body naturally and spontaneously responds to all challenges without thought". This has been compared to the psychological concept of flow and "being in the zone".

Terminology

The term contains theChinese character

Chinese characters are logographs used to write the Chinese languages and others from regions historically influenced by Chinese culture. Of the four independently invented writing systems accepted by scholars, they represent the only on ...

for negation, "not" or "without" (), along with the character for heart-mind (). Likewise, in Sanskrit, the term is a compound of the prefix

A prefix is an affix which is placed before the stem of a word. Particularly in the study of languages, a prefix is also called a preformative, because it alters the form of the word to which it is affixed.

Prefixes, like other affixes, can b ...

a- (for negation) and the word citta (mind, thought, consciousness, heart). In China, the term came to mean a state in which there was no mental activity, or a mind free of all discrimination and conceptualization, making it similar to the Buddhist Sanskrit term nis prapañca and the Sanskrit term nirvikalpa. Another similar Sanskrit term is amanasikāra (non-thinking, mental non-engagement), which is found in the works of the 11th century tantric yogi Maitripa.

Some scholars like D.T. Suzuki see the term ''wu-nien'' (, without thought, without recollection, with ''nien'' possibly rendering ''smṛti

' (, , ), also spelled ' or ', is a body of Hindu texts representing the remembered, written tradition in Hinduism, rooted in or inspired by the Vedas. works are generally attributed to a named author and were transmitted through manuscripts, ...

'', "mindfulness") as being synonymous to ''wu-xin''. Furthermore, while wunien is common in the texts of the Southern school of Zen, the texts of the Northern school prefer the term "freedom from thought" or "freedom from conceptualization" (離念). Some scholars also offer other Sanskrit terms as being the source of the Chinese term ''wunien'', including: ''a-cintya, a- vikalpa'' or ''a-saṃjñā

''Saṃjñā'' (Sanskrit; Pali: ''sañña'') is a Buddhist term that is typically translated as "perception" or "cognition." It can be defined as grasping at distinguishing features or characteristics. ''Samjñā'' has multiple meanings dependi ...

''.

Regarding terms which negate "vikalpa" (conceptualization, discrimination, imagination), such as avikalpa and nirvikalpa, these are also widely used in Buddhist sources. The type of knowledge known as nirvikalpa- jñāna is an important term used in Mahayana Buddhist sources to refer to a transcendent type of knowledge. Furthermore, the term nirvikalpa is also sometimes applied to other concepts, such as Buddha nature. The '' Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra'' for example, states that the buddha-nature is ''nirvikalpa'' and ''nirbhāsa'' (without appearance). Other Mahayana sources use nirvikalpa as a description of the Buddha's Dharmakaya (Dharma-body).

Another related Sanskrit term is anupalabdhi / anupalambha (non-perception, non-apprehension) which is found in the ''Prajñaparamita sutras'' as a description of Prajñaparamita (the perfection of wisdom). For example, in the ''Diamond Sutra

The ''Diamond Sutra'' (Sanskrit: ) is a Mahayana, Mahāyāna Buddhism, Buddhist sutra from the genre of ('perfection of wisdom') sutras. Translated into a variety of languages over a broad geographic range, the ''Diamond Sūtra'' is one of th ...

'', the Buddha states: "there is nothing whatsoever for me to ''apprehend'' in unexcelled complete perfect enlightenment." The '' Aṣṭasāhasrikā prajñāpāramitā sutra'' even equates the two, stating: "the non-perception (anupalambha) of all principles (dharmas) is called the perfection of wisdom".

The term no-mind is also found in the Japanese phrase , a Zen

Zen (; from Chinese: ''Chán''; in Korean: ''Sŏn'', and Vietnamese: ''Thiền'') is a Mahayana Buddhist tradition that developed in China during the Tang dynasty by blending Indian Mahayana Buddhism, particularly Yogacara and Madhyamaka phil ...

expression meaning ''the mind without mind''. That is, a mind not fixed or occupied by thought or emotion and thus open to everything. It is translated by D.T. Suzuki as "being free from mind-attachment".

In Indian Buddhism

TheSanskrit

Sanskrit (; stem form ; nominal singular , ,) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan languages, Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in northwest South Asia after its predecessor languages had Trans-cultural ...

term ''acitta'' (no-mind, no-thought, unconceived, inconceivable, from a+ citta) is found in several Mahayana sutras

The Mahayana sutras are Buddhist texts that are accepted as wikt:canon, canonical and authentic Buddhist texts, ''buddhavacana'' in Mahayana, Mahayana Buddhist sanghas. These include three types of sutras: Those spoken by the Buddha; those spoke ...

, and it is often related to an absence of conceptualization ( vikalpa), clinging and negative mental states or thoughts. In some of these texts, the term is associated with another important term in Mahayana

Mahāyāna ( ; , , ; ) is a term for a broad group of Buddhist traditions, Buddhist texts#Mahāyāna texts, texts, Buddhist philosophy, philosophies, and practices developed in ancient India ( onwards). It is considered one of the three main ex ...

Buddhism, the naturally luminous mind (''cittasya prabhāsvarā''). For example, the ''Pañcavimsati Prajñaparamita sutra'' states'':''This mind (citta) is no-mind (acitta), because its natural character is luminous. What is this state of the mind’s luminosity (prabhāsvaratā)? When the mind is neither associated with nor dissociated from greed, hatred, delusion, proclivities (anusaya), fetters ( samyojana), or false views ( drsti), then this constitutes its luminosity. Does the mind exist as no-mind? In the state of no-mind (acittat), the states of existence or non-existence can be neither found nor established... What is this state of no-mind? The state of no-mind, which is immutable (avikra) and undifferentiated (avikalpa), constitutes the ultimate reality ( dharmata) of all dharmas henomena Such is the state of no-mind.As such, this is a state which is beyond all craving or attachment, beyond all views, conceptualization, or dualities (such as being and non-being, birth and death). The term also appears in the ''Gaganagañjaparipṛcchā sutra,'' which states:

Strive for awakening (bodhi) freed from false view (darśana), and for essential nature (svabhāva) which is like an illusion (māya) and mirage (marīci). Strive to attain non-thought (acitta), even though the thought does not exist in reality, and to teach unchanging dharmas.The Indian Buddhist philosopher

Vasubandhu

Vasubandhu (; Tibetan: དབྱིག་གཉེན་ ; floruit, fl. 4th to 5th century CE) was an influential Indian bhikkhu, Buddhist monk and scholar. He was a philosopher who wrote commentary on the Abhidharma, from the perspectives of th ...

also mentions the term in his '' Thirty Verses on Consciousness Only.'' He associates it with a kind of non-conceptual knowledge (nirvikalpa- jñana) of ultimate reality ( paramartha) which does not rely on or grasp any cognitive object (anupalambha) or thought (acintya), indeed it is totally beyond all cognition or thinking. According to Vasubandhu:When the mind no longer seizes on any object ( alambana) whatever, then the mind is established in the nature of consciousness only. When there is nothing that is grasped, that is mind only, because there is no grasping. That is the supreme, world-transcending knowledge (jñana), without mind (acitta) and without support or object (anupalambha).In his commentary on this passage, the later Indian philosopher Sthiramati states that this kind of supramundane knowledge refers to a non-discriminative experience beyond subject-object duality.

In Chinese sources

Taoism

The term no-mind (wu-xin) is also found in the ''Zhuangzi'' as well as in the commentary of Guo Xiang, as was thus also discussed by Chinese Daoist thinkers. This would entail that the term existed in Chinese sources which pre-date the introduction of Buddhism to China. As such, many scholars like Fukunaga Mitsuji have suggested that this Daoist idea also influenced the Chinese Buddhist understanding of no-mind. In Daoist philosophy, the term no-mind was associated with the inner state of a Daoist sage (shengren ), "one who has no-mind and accords with things" (Guo Xiang), as well as with other Daoist concepts likevirtue

A virtue () is a trait of excellence, including traits that may be morality, moral, social, or intellectual. The cultivation and refinement of virtue is held to be the "good of humanity" and thus is Value (ethics), valued as an Telos, end purpos ...

(de), wu wei (non-action) and self-forgetting (wu-chi). It is a state of being carefree and ease which the sage has achieved through the pursuit of Daoist self-cultivation practices such as fasting the mind (, xīn zhāi) and sitting and forgetting (; zuòwàng).

Chinese Buddhism

The term no mind (wuxin) was first discussed by Chinese exegetes of the Prajñaparamita sutras, who understood the term as a gloss on emptiness. These commentators were known as "the school of no-mind" (, xinwu zong) and included figures like Zhi Mindu (fl. 326).

The influential '' Mahayana Awakening of Faith'' also mentions no-mind or no-thought (though it uses the term ''wu-nien'', ) in relation to its doctrine of the ultimate One Mind, which is pure, without thought, immutable, and unchanging:

The term no mind (wuxin) was first discussed by Chinese exegetes of the Prajñaparamita sutras, who understood the term as a gloss on emptiness. These commentators were known as "the school of no-mind" (, xinwu zong) and included figures like Zhi Mindu (fl. 326).

The influential '' Mahayana Awakening of Faith'' also mentions no-mind or no-thought (though it uses the term ''wu-nien'', ) in relation to its doctrine of the ultimate One Mind, which is pure, without thought, immutable, and unchanging:The object-realms of the five senses and the mind are ultimately wu-nien ... Sentient beings ... deluded by ignorance mistake the mind as thought (nien) but the mind itself never moves (tung). If a person can so examine it and realize that the mind itself is wu-nien, he would smoothly and in due accord enter the gate of Suchness.The idea of no-mind is thus originally connected to a Buddhist practice which allows one to be aware of the originally enlightened buddha-nature in all beings, which is the ultimate reality and the nature of mind''.'' In the ''Awakening of Faith'', this ultimate reality is the "One Mind", the Dharmakaya, which is without thought (wu-nien).

Chan

The term no-mind quickly became a central teaching of the Chan schools. It is the key topic of a short Chan text among the Dunhuang manuscripts called ''Treatise on No-Mind (Wuxin lun)'' which is attributed to Bodhidharma''.'' This text bears many similarities to another text, the ''Jueguanlun'' (''Treatise on Cutting off Contemplation''). Some scholars also see Daoist influence on these as well as the influence of the works of Sengzhao. The ''Treatise on No-Mind'' is considered to summarize the teachings of the Southern school tradition. Huangbo Xiyun (died 850 CE) mentions the concept several times, writing that "if one could only achieve no-mind right at this moment, the fundamental essence () will appear of itself". He also writes:The Mind is Buddha; no-mind is the Way ao Just be without mind and stop your thinking. Just be of that Mind where there is no existence or non-existence, no long and no short, no self and no others, neither negative nor positive, and neither within nor without. Just know, above all, that non-differentiating Mind is the Buddha, that Buddha is the Mind and that the Mind is emptiness. Therefore, the real Dharmakaya is just emptiness. It is not necessary to seek anything whatsoever, and all who do continue to seek for something only prolong their suffering in samsara...Hold neither a concept of holy nor of worldliness; think neither of emptiness nor tranquility in the Dharma. Since originally there is no non-existent Dharma, it is, therefore, not necessary to have a view of existence as such. Furthermore, concepts of existence and non-existence are all perverted views just like the illusion created by a film spread over diseased eyes. Analogously, the perceptions of seeing and hearing, just like the film that creates the illusion for diseased eyes, cause the errors and delusions of all sentient beings. Being without motive, desire or view, and without compromise, is the way of the patriarchs.As such, the state of no-mind is a state in which the workings of the intrinsically pure original mind (), which is the Buddha-mind, are known and allowed to function without obstruction, desire, or calculation. This original mind which is free and spontaneous is also not separate from the everyday working of the mind, even though it does not belong to the worldly functions of mind. The teaching of no-mind is also reflected in the works of later Chan masters like Linji and Dongshan. According to Muller, some scholars and practitioners have made the error of thinking that the term "no-mind" or "no-thought" refers to "some kind of permanent, or ongoing absence of thought" or to "a permanent incapacitation of the thinking faculty or the permanent cessation of all conceptual activity"''.'' However, this assumption is mistaken and it is not what is taught in the classic Chan / Zen texts like the ''Platform Sutra,'' or the '' Sutra of Perfect Enlightenment.'' Likewise, Japanese philosopher Izutsu Toshihiko argues that no-mind is not unconsciousness, mental torpor, lethargy or absent-mindedness. Instead, it is a state of intense clarity and lucidity and compares it to the state of a master musician. Muller explains the classic Zen Buddhist understanding of no-mind as follows:

...the interruption of the discursive process at a sufficiently deep level allows for an experiential vision of a different aspect of the mind, a vision that allows for a change in the nature of the mental function. But it is not that thought no longer occurs--the conceptualizing faculty still functions quite well--in fact, even better than before, since, now, under the influence of the deeper dimension of the mind it no longer has to operate in a rigid, constricted, and clinging manner. It is now possible to see things more clearly, unfiltered by one's personal depository of presuppositions. This is what is meant by seeing the " suchness" of things''.'' When the Ch'an writers talk about no-thought, or no-mind, it is this state of non-clinging or freedom from mistaken conceptualization to which they are referring, rather than the permanent cessation of thinking that some imagine. The deeper, immeasurably more clear aspect of the mind that they experience in the course of this irruption of the discursive flow, they call "enlightenment." Realizing now, that this potential of the mind was always with them, they call it "innate."''''Thus, ''no-mind'' is a pure experience achieved when a person's mind is free from thoughts, concepts, clinging and discrimination. In this state, one is totally free to act effortlessly and spontaneously from their deepest nature (the buddha-nature). It is thus not a kind of sleepiness or stupefaction, but a state of clarity. The mind remains clear and awake, but with no intention, plan or direction. According to John Visvader and William Doub, the Chan idea of acting with no-mind, or no-thought, resembles the Daoist notion of "everything being accomplished by non-action" (無為而無不為, ''wúwéi ér wú bù wéi,'' literally: "nothing done, yet nothing not done"). Zen teachers state that one should cultivate the state of no-mind in daily life, not just in formal meditation. In this context, the Zen student trains to live in the state of no-mind in every aspect of their daily routine, eventually achieving a kind of effortlessness in all activities. This is sometimes expressed by the phrase "The everyday mind is the way." A similar term, no-thought (''wunian''), is found in the influential Chinese Chan text called the '' Platform Sutra'', which states:

"No-thought" means "no-thought within thought." Non-abiding is man's original nature. Thoughts do not stop from moment to moment. The prior thought is succeeded in each moment by the subsequent thought, and thoughts continue one after another without cease. If, for one thought-moment, there is a break, the dharma-body separates from the physical body, and in the midst of successive thoughts there will be no attachment to any kind of matter. If, for one thought-moment, there is abiding, then there will be abiding in all successive thoughts, and this is called clinging. If, in regard to all matters there is no abiding from thought-moment to thought-moment, then there is no clinging. Non-abiding is the basis''.''The ''Platform Sutra'' further breaks down the term ''non-thought'' as follows: "‘Non’ means to be without the characteristic of duality, to be without the mind of the enervating defilements. ‘Thought’ is to think of the fundamental nature of suchness. Suchness is the essence of thought, thought is the function of suchness." The term ''wunian'' was widely adopted and used by Chinese Chan masters like Shenhui, who compared no-thought to a clear mirror that is not reflecting any objects but retains its reflective capacity.

In Japanese Zen

A similar term, the Japanese term ''hishiryō'' (, "non-thinking", "without thinking", "beyond thinking"), is used by the Soto Zen founderDōgen

was a Japanese people, Japanese Zen Buddhism, Buddhist Bhikkhu, monk, writer, poet, philosopher, and founder of the Sōtō school of Zen in Japan. He is also known as Dōgen Kigen (), Eihei Dōgen (), Kōso Jōyō Daishi (), and Busshō Dent� ...

in his key work on zazen (seated meditation), the '' Fukan zazengi''. The key passage, which became the paradigmatic description of zazen in the Soto school, first describes the preliminaries of zazen posture and other preparations, and then states:

...settle into a steady, immobile sitting position. Think of not thinking (''fushiryō''). How do you think of not-thinking? Without thinking (''hishiryō''). This in itself is the essential art of zazen. The zazen I speak of is not learning meditation. It is simply the Dharma-gate of repose and bliss, the cultivation-authentication of totally culminated enlightenment. It is the presence of things as they are.This passage is actually based on a traditional zen dialogue about master Yakusan Gudo (Chinese: Yueh-shan Hung-tao c. 745-828) which also contains phrases like non-thinking. According to Cleary, it refers to ''ekō henshō'', turning the light around, in which awareness illuminates awareness itself. According to Dogen scholar Masanobu Takahashi, the term ''hishiryō'' is not a state in which there is no mental activity whatsoever nor a cutting off of all thinking. Instead, it refers to a state "beyond thinking and not-thinking" which Thomas Kasulis glosses as "merely accepting the presence of ideation without either affirmation or denial." Other Japanese Dogen scholars link the term with the realization of emptiness. Kasulis understands the term phenomenologically as "pure presence of things as they are", "without affirming nor negating", without accepting nor rejecting, without believing nor disbelieving. In short, it is a non-conceptual, non-intentional and "prereflective mode of consciousness" which does not imply that it is an experience without content. Similarly, Hee-Jin Kim describes this state as "not just to transcend both thinking and not-thinking, but to realize both, in the absolutely simple and singular act of resolute sitting itself", which is "objectless, subjectless, formless, goalless and purposeless" and yet it is not "void of intellectual content as in a vacuum". Kim further emphasizes that nonthinking is used synonymously with emptiness by Dogen, and that it is also a kind of samadhi that is rooted in the body.

In martial arts

In Asia, the Buddhist idea of no-mind became widely applied to various arts, especiallymartial arts

Martial arts are codified systems and traditions of combat practiced for a number of reasons such as self-defence; military and law enforcement applications; combat sport, competition; physical, mental, and spiritual development; entertainment; ...

, as Buddhist spirituality was seen as a useful addition to physical training. Some Buddhist teachers encouraged this application of Buddhist thought to the martial arts. For example, Zen Master Takuan Sōhō (1573–1645) was known to teach Zen to samurai. He wrote an influential letter to a master swordsman, Yagyū Munenori, called ''The Mysterious Record of Immovable Wisdom''. In this letter, Takuan described no-mind as follows:

The No-Mind … neither congeals nor fixes itself in one place. It is called No-Mind when the mind has neither discrimination nor thought but travels about the entire body and extends throughout the entire self. The No-Mind is placed nowhere. Yet it is not like wood or stone. Where there is no stopping place, it is called No-Mind.Takuan thus sees "the mind of no-mind" (Japanese: mushin no shin) as a free and open mind, which he contrasts with the fixed and stuck "mind of having-mind". In ''The Mysterious Record of Immovable Wisdom'', Takuan compares the mind of no mind to flowing water. He warns Munenori not to "place his mind" or fixate it anywhere (not on your sword, your body, you opponent's sword, etc). Since "there is no place to put the mind", it must remain free and able to permeate everywhere. As such, Takuan writes, "Placed nowhere, it will be everywhere!". On page 84 of his 1979 book ''Zen in the Martial Arts'', Joe Hyams wrote that

Bruce Lee

Bruce Lee (born Lee Jun-fan; November 27, 1940 – July 20, 1973) was an American-born Hong Kong martial artist, actor, filmmaker, and philosopher. He was the founder of Jeet Kune Do, a hybrid martial arts philosophy which was formed from ...

had read the following quote to him, attributed to the legendary Zen master Takuan Sōhō:

The mind must always be in the state of 'flowing,' for when it stops anywhere that means the flow is interrupted and it is this interruption that is injurious to the well-being of the mind. In the case of the swordsman, it means death. When the swordsman stands against his opponent, he is not to think of the opponent, nor of himself, nor of his enemy's sword movements. He just stands there with his sword which, regardless of all technique, is ready only to follow the dictates of the subconscious. The man has effaced himself as the wielder of the sword. When he strikes, it is not the man but the sword in the hand of the man's subconscious that strikes.Some martial arts masters believe that ''mushin'' is the state where a person finally understands the uselessness of techniques and becomes truly free to move. In fact, those people will no longer even consider themselves as "fighters" but move spontaneously without any self-conceptions. However, ''mushin'' is not just a state of mind that can be achieved during combat. Many martial artists train to achieve this state of mind during

kata

''Kata'' is a Japanese word ( 型 or 形) meaning "form". It refers to a detailed choreographed pattern of martial arts movements. It can also be reviewed within groups and in unison when training. It is practiced in Japanese martial arts ...

so that a flawless execution of moves is learned and may be repeated at any other time. Once ''mushin'' is attained through the practice or study of martial arts (although it can be accomplished through other arts or practices that refine the mind and body), the objective is to then attain this same level of complete awareness in other aspects of the practitioner's life. Dr Robert Akita claims it helps him "listen to my wife and children more closely...especially when I disagree with them, ndin my business it has helped when I am faced with difficult decisions...."

Modern views

The topic of no-mind was taken up by the modern Japanese Zen scholar D.T. Suzuki (1870–1966), who saw the idea as the central teaching of Zen. In his ''The Zen Doctrine of No-Mind'' (1949), which is also a study of the ''Platform Sutra'', Suzuki defines the term no-mind as the realization of non-duality, the overcoming of all dualism and discrimination''.'' Suzuki held that a key aspect of no-mind was “receptivity” (judōsei ), a state of acceptance, openness, letting go, and non-resistance. In Buddhist terms, Suzuki also held that in this state, the Buddha begins working through you. Thus, Suzuki writes "abandon both the body and the mind, and throw it all into the Buddha. And let the Buddha work for you." For Suzuki, the attainment of no-mind is achieved through entrusting oneself to the Buddha, which is the “original purity” (honshō shōjō ) at heart of all beings. Indeed, Suzuki held that the pure no-mind was also at the heart of all religions. Suzuki also emphasized the theme of “naturalness” (jinenhōni ) as a key feature of no-mind. He saw the state as one which was dynamic, not static. This was a natural dynamism, not a calculated one. Tadashi Nishihira compares these ideas to Dogen's concept of the “pliant mind” (nyūnanshin ), which is achieved when one has "cast off body and mind" in zazen.See also

* Fudōshin * Mokuso * Sahaja * Samyama *Shoshin

''Shoshin'' () is a concept from Zen Buddhism meaning beginner's mind. It refers to having an attitude of openness, eagerness, and lack of preconceptions when studying, even at an advanced level, just as a beginner would. The term is especial ...

* Unconscious mind

In psychoanalysis and other psychological theories, the unconscious mind (or the unconscious) is the part of the psyche that is not available to introspection. Although these processes exist beneath the surface of conscious awareness, they are t ...

* Zanshin

References

Works cited

* * * * {{refendExternal links

How Do You Think Not Thinking? Just Think

Barry Magid Japanese martial arts terminology Zen