Munir Ahmad Khan on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Munir Ahmad Khan (; 20 May 1926 – 22 April 1999), , was a Pakistani nuclear engineer who is credited, among others, with being the "father of the atomic bomb program" of Pakistan for their leading role in developing their nation's

While studying at the Government College University in Lahore in the 1940s, Khan had acquainted with Abdus Salam and was supportive of Salam's efforts for his vision to put his country engaged towards scientific education and literacy as an adviser in the Ayub administration in the 1960s. While working at IAEA, Khan recognized the importance of

While studying at the Government College University in Lahore in the 1940s, Khan had acquainted with Abdus Salam and was supportive of Salam's efforts for his vision to put his country engaged towards scientific education and literacy as an adviser in the Ayub administration in the 1960s. While working at IAEA, Khan recognized the importance of

In 1972, the earlier efforts were directed to a plutonium boosted fission implosion-type device whose design was codenamed: '' Kirana-I''. In March 1974, Khan, together with Salam, held a meeting at the Institute of Nuclear Science and Technology with Hafeez Qureshi, a mechanical engineer with an expertise in radiation heat transfer, and Dr. Zaman Shaikh, a chemical engineer from the Defense Science and Technology Organization (DESTO).Alt URL

In 1972, the earlier efforts were directed to a plutonium boosted fission implosion-type device whose design was codenamed: '' Kirana-I''. In March 1974, Khan, together with Salam, held a meeting at the Institute of Nuclear Science and Technology with Hafeez Qureshi, a mechanical engineer with an expertise in radiation heat transfer, and Dr. Zaman Shaikh, a chemical engineer from the Defense Science and Technology Organization (DESTO).Alt URL

At that meeting, the word " ''bomb''" was never used but it was understood the need for the development of explosive lenses, a sub-critical sphere of fissile material could be squeezed into a smaller and denser form, and the reflective tamper, the metal needed to scatter only very short distances, so the critical mass would be assembled in much less time. This project required manufacturing and machining of key parts that necessitated another laboratory site, leading Khan, assisted by Salam, to meet with

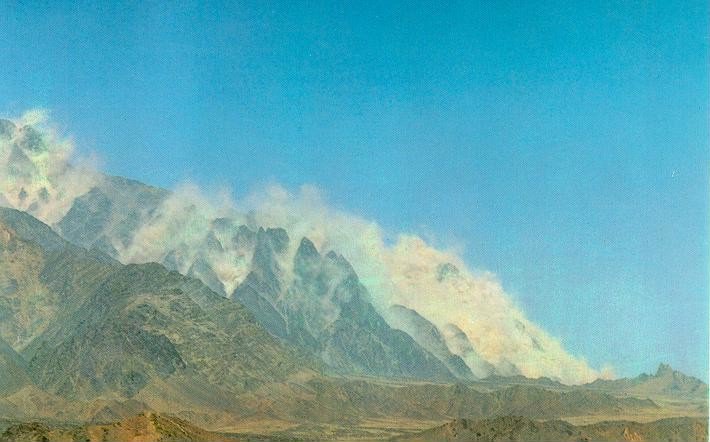

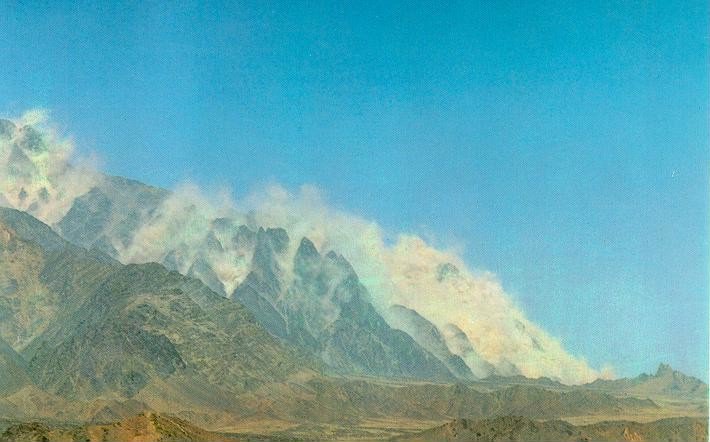

In 1975, AQ Khan, in discussion with the Corps of Engineers, had selected the mountain ranges in Balochistan for the isolation needed to maintain security and secrecy. He tasked Ishfaq Ahmad and Ahsan Mubarak, a

In 1975, AQ Khan, in discussion with the Corps of Engineers, had selected the mountain ranges in Balochistan for the isolation needed to maintain security and secrecy. He tasked Ishfaq Ahmad and Ahsan Mubarak, a

In 1972, Khan bought an estate in Islamabad and then died following complications from heart surgery, aged 72, on 22 April 1999. He is survived by his wife, Thera, three children and four grandchildren.

When Abdus Salam was ejected from his position in 1974, Khan symbolized of many scientists thinking they could control how other peers would use their research. During the timeline of atomic bomb program, Khan was seen as a symbol of both

In 1972, Khan bought an estate in Islamabad and then died following complications from heart surgery, aged 72, on 22 April 1999. He is survived by his wife, Thera, three children and four grandchildren.

When Abdus Salam was ejected from his position in 1974, Khan symbolized of many scientists thinking they could control how other peers would use their research. During the timeline of atomic bomb program, Khan was seen as a symbol of both

Biographical sketch

Scientist dr. Munir Ahmad

Who's the father of the atomic bomb- IISS

IN Memoriam: Munir Ahmad Khan, IAEA

The Nuclear Supremo Munir Khan

Mineral Research Laboratories

PAEC official page

, - {{DEFAULTSORT:Khan, Munir Ahmad 1926 births 1999 deaths Pashtun scientists People from Kasur District Scientists from Lahore Government College University, Lahore alumni University of the Punjab alumni 20th-century Pakistani engineers Pakistani electrical engineers Academic staff of the University of Engineering and Technology, Lahore Pakistani expatriates in the United States North Carolina State University alumni Pakistani physicists Illinois Institute of Technology alumni Pakistani nuclear engineers International Atomic Energy Agency officials Pakistani expatriates in Austria Chairpersons of the Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission Pakistani nuclear physicists Weapons scientists and engineers Quantum physicists Theoretical physicists Scientists from Islamabad Academic staff of Pakistan Institute of Engineering and Applied Sciences Founders of Pakistani schools and colleges Fellows of Pakistan Academy of Sciences Recipients of Hilal-i-Imtiaz Recipients of Nishan-e-Imtiaz Members of the Pakistan Philosophical Congress Nuclear weapons scientists and engineers People from Punjab Province (British India)

nuclear weapon

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission or atomic bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear weapon), producing a nuclear exp ...

s during the successive years after the war with India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

in 1971.

From 1972 to 1991, Khan served as the chairman of the Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission (PAEC) who directed and oversaw the completion of the clandestine bomb program from its earliest efforts to develop the atomic weapons to their ultimate nuclear testings in May 1998. His early career was mostly spent in the International Atomic Energy Agency

The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) is an intergovernmental organization that seeks to promote the peaceful use of nuclear technology, nuclear energy and to inhibit its use for any military purpose, including nuclear weapons. It was ...

and he used his position to help establish the International Centre for Theoretical Physics in Italy and an annual conference on physics in Pakistan. As chair of PAEC, Khan was a proponent of the nuclear arms race

The nuclear arms race was an arms race competition for supremacy in nuclear warfare between the United States, the Soviet Union, and their respective allies during the Cold War. During this same period, in addition to the American and Soviet nuc ...

with India whose efforts were directed towards concentrated production of reactor-grade to weapon-grade plutonium

Plutonium is a chemical element; it has symbol Pu and atomic number 94. It is a silvery-gray actinide metal that tarnishes when exposed to air, and forms a dull coating when oxidized. The element normally exhibits six allotropes and four ...

while remained associated with nation's key national security programs.

After retiring from the Atomic Energy Commission in 1991, Khan provided the public advocacy for nuclear power generation as a substitute for hydroelectricity consumption in Pakistan

Pakistan, officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of over 241.5 million, having the Islam by country# ...

and briefly tenured as the visiting professor of physics at the Institute of Applied Sciences in Islamabad

Islamabad (; , ; ) is the capital city of Pakistan. It is the country's tenth-most populous city with a population of over 1.1 million and is federally administered by the Pakistani government as part of the Islamabad Capital Territory. Bu ...

. Throughout his life, Khan was subjected to political ostracization due to his advocacy for averting nuclear proliferation

Nuclear proliferation is the spread of nuclear weapons to additional countries, particularly those not recognized as List of states with nuclear weapons, nuclear-weapon states by the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, commonl ...

and was rehabilitated when he was honored with the '' Nishan-i-Imtiaz'' (Order of Excellence) by the President of Pakistan in 2012— thirteen years after his death in 1999.

Youth and early life

Munir Ahmad Khan was born in Kasur,Punjab

Punjab (; ; also romanised as Panjāb or Panj-Āb) is a geopolitical, cultural, and historical region in South Asia. It is located in the northwestern part of the Indian subcontinent, comprising areas of modern-day eastern Pakistan and no ...

in the British Indian Empire

The British Raj ( ; from Hindustani language, Hindustani , 'reign', 'rule' or 'government') was the colonial rule of the British The Crown, Crown on the Indian subcontinent,

*

* lasting from 1858 to 1947.

*

* It is also called Crown rule ...

on 20 May 1926 into a Kakazai family that had long been settled in Punjab. After completing his matriculation

Matriculation is the formal process of entering a university, or of becoming eligible to enter by fulfilling certain academic requirements such as a matriculation examination.

Australia

In Australia, the term ''matriculation'' is seldom used no ...

in 1942 in Kasur, Khan enrolled at the Government College University in Lahore

Lahore ( ; ; ) is the capital and largest city of the Administrative units of Pakistan, Pakistani province of Punjab, Pakistan, Punjab. It is the List of cities in Pakistan by population, second-largest city in Pakistan, after Karachi, and ...

and was a contemporary of Abdus Salam— the Nobel Laureate in Physics in 1978

Events January

* January 1 – Air India Flight 855, a Boeing 747 passenger jet, crashes off the coast of Bombay, killing 213.

* January 5 – Bülent Ecevit, of Republican People's Party, CHP, forms the new government of Turkey (42nd ...

. In 1946, Khan graduated with a Bachelor of Arts

A Bachelor of Arts (abbreviated B.A., BA, A.B. or AB; from the Latin ', ', or ') is the holder of a bachelor's degree awarded for an undergraduate program in the liberal arts, or, in some cases, other disciplines. A Bachelor of Arts deg ...

(BA) in mathematics and enrolled at the Punjab University to study engineering in 1949.

In 1951, Khan graduated with a Bachelor of Science in Engineering (BSE) in electrical engineering

Electrical engineering is an engineering discipline concerned with the study, design, and application of equipment, devices, and systems that use electricity, electronics, and electromagnetism. It emerged as an identifiable occupation in the l ...

and was noted for his academic standing when he was named to the Roll of Honor for his class of 1951. After graduation, Khan served on an engineering faculty of the University of Engineering and Technology (UET) in Lahore, and earned a Fulbright Scholarship to study engineering in the United States.Haris N. Khan, "Pakistan's Nuclear Development: Setting the Record Straight," Defence Journal, August 2010"Munir Khan Passes Away," Business Recorder, 23 April 1999.

Under the Fulbright Scholarship program, Khan attended North Carolina State University

North Carolina State University (NC State, North Carolina State, NC State University, or NCSU) is a public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Raleigh, North Carolina, United States. Founded in 1887 and p ...

to resume his graduate studies in electrical engineering and graduated with a Master of Science

A Master of Science (; abbreviated MS, M.S., MSc, M.Sc., SM, S.M., ScM or Sc.M.) is a master's degree. In contrast to the Master of Arts degree, the Master of Science degree is typically granted for studies in sciences, engineering and medici ...

(MS) in electrical engineering in 1953. His master's thesis, titled: ''Investigation on Model Surge Generator'' contained fundamental work on applications of the impulse generator.

In the United States, Khan gradually lost interest in electrical engineering and took an interest in physics when he started taking graduate courses on topics involving the thermodynamics

Thermodynamics is a branch of physics that deals with heat, Work (thermodynamics), work, and temperature, and their relation to energy, entropy, and the physical properties of matter and radiation. The behavior of these quantities is governed b ...

and kinetic theory of gases at the Illinois Institute of Technology

The Illinois Institute of Technology, commonly referred to as Illinois Tech and IIT, is a Private university, private research university in Chicago, Illinois, United States. Tracing its history to 1890, the present name was adopted upon the m ...

. In 1953, Khan left his graduate studies in physics at the Illinois Institute of Technology when he accepted to be a participant in the Atoms for Peace policy of the United States and started his training program in nuclear engineering offered by the North Carolina State University

North Carolina State University (NC State, North Carolina State, NC State University, or NCSU) is a public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Raleigh, North Carolina, United States. Founded in 1887 and p ...

in cooperation with the Argonne National Laboratory

Argonne National Laboratory is a Federally funded research and development centers, federally funded research and development center in Lemont, Illinois, Lemont, Illinois, United States. Founded in 1946, the laboratory is owned by the United Sta ...

in Illinois in 1953.20 Years VIC (1979–1999), ECHO, Journal of the IAEA Staff- No. 202, pp. 24–25

In 1957, Khan completed his training at the Argonne National Laboratory, and college classes in nuclear engineering, that allowed him to graduate with an MS degree in nuclear engineering, with strong emphasis on nuclear reactor physics, from North Carolina State University.

Early professional work

After graduating from North Carolina State University (NCSU) in 1953, Khan found employment with Allis-Chalmers inWisconsin

Wisconsin ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Great Lakes region, Great Lakes region of the Upper Midwest of the United States. It borders Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake Michigan to the east, Michig ...

before joining the Commonwealth Edison company in Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. It borders on Lake Michigan to its northeast, the Mississippi River to its west, and the Wabash River, Wabash and Ohio River, Ohio rivers to its ...

. At both engineering firms, Khan worked on power generation equipment such as generators and mechanical pumps and participated in a federal contract awarded to Commonwealth Edison to design and construct the Experimental Breeder Reactor I

Experimental Breeder Reactor I (EBR-I) is a decommissioned research reactor and U.S. National Historic Landmark located in the desert about southeast of Arco, Idaho. It was the world's first breeder reactor. At 1:50 p.m. on December 2 ...

(EBR-I) which built up his interests in practical applications of physics that led him to attend the Illinois Institute of Technology, and to attend the training program in nuclear engineering offered by NCSU.

In 1957, Khan served as a Resident Research Associate in the Nuclear Engineering Division at the Argonne National Laboratory where he was trained as a nuclear reactor physicist and worked on design modifications of the Chicago Pile-5 (CP-5) reactor before working for a brief time at American Machine and Foundry as a consultant until 1958.

International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA)

In 1958, Khan left the United States after accepting employment with theInternational Atomic Energy Agency

The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) is an intergovernmental organization that seeks to promote the peaceful use of nuclear technology, nuclear energy and to inhibit its use for any military purpose, including nuclear weapons. It was ...

(IAEA) in Austria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

, joining the nuclear power division at a senior technical position, and was noted as the first Asian person from any developing country

A developing country is a sovereign state with a less-developed industrial base and a lower Human Development Index (HDI) relative to developed countries. However, this definition is not universally agreed upon. There is also no clear agreeme ...

to be appointed to a senior position there. During this time, Khan was taken as an advisor on energy issues by the Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission (PAEC) and represented his country at various energy-based conferences and seminars for nuclear power generation. At IAEA, Khan's work was mostly based on reactor technology and he worked on the application of nuclear reactor physics to the utilization factor of nuclear reactors, overseeing technical aspects of the nuclear reactors as well as conducting a geological survey for the construction of commercial nuclear power plants.

His work on nuclear reactor physics, specifically determining neutron transport and the interaction of neutrons within the reactor, was widely recognized and he was often known as "''Reactor Khan''" among his peers at the nuclear power division of the IAEA. Khan was also known to have gained expertise in producing isotopic reactor-grade plutonium, deriving it from neutron capture

Neutron capture is a nuclear reaction in which an atomic nucleus and one or more neutrons collide and merge to form a heavier nucleus. Since neutrons have no electric charge, they can enter a nucleus more easily than positively charged protons, wh ...

, that is frequently found alongside the uranium-235

Uranium-235 ( or U-235) is an isotope of uranium making up about 0.72% of natural uranium. Unlike the predominant isotope uranium-238, it is fissile, i.e., it can sustain a nuclear chain reaction. It is the only fissile isotope that exists in nat ...

(U235) civilian reactors, in the form of low enriched uranium.

At IAEA, Khan organized more than 20 international technical and scientific conferences and seminars on the topics of constructing deuterium-based (heavy water

Heavy water (deuterium oxide, , ) is a form of water (molecule), water in which hydrogen atoms are all deuterium ( or D, also known as ''heavy hydrogen'') rather than the common hydrogen-1 isotope (, also called ''protium'') that makes up most o ...

) reactors, gas-cooled reactor systems, efficiency and performance of nuclear power plants, the fuel extraction of uranium, and production of plutonium. In 1961, he prepared a technical feasibility report on behalf of the IAEA on small nuclear power reactor projects of the United States Atomic Energy Commission

The United States Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) was an agency of the United States government established after World War II by the U.S. Congress to foster and control the peacetime development of atomic science and technology. President Harry ...

.

In 1964 and 1971, Khan served as scientific secretary to the third and fourth United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

International Geneva Conferences on the Peaceful Uses of Atomic Energy. Between 1986 and 1987, Khan also served as Chairman of the IAEA Board of Governors and headed Pakistan's delegations to IAEA General Conferences from 1972 to 1990. He served as a Member of the IAEA Board of Governors for 12 years.

International Centre for Theoretical Physics

While studying at the Government College University in Lahore in the 1940s, Khan had acquainted with Abdus Salam and was supportive of Salam's efforts for his vision to put his country engaged towards scientific education and literacy as an adviser in the Ayub administration in the 1960s. While working at IAEA, Khan recognized the importance of

While studying at the Government College University in Lahore in the 1940s, Khan had acquainted with Abdus Salam and was supportive of Salam's efforts for his vision to put his country engaged towards scientific education and literacy as an adviser in the Ayub administration in the 1960s. While working at IAEA, Khan recognized the importance of Theoretical physics

Theoretical physics is a branch of physics that employs mathematical models and abstractions of physical objects and systems to rationalize, explain, and predict List of natural phenomena, natural phenomena. This is in contrast to experimental p ...

but was more interested in studying its "real world" applications that related to the field of physics of nuclear reaction in a confined nuclear reactor

A nuclear reactor is a device used to initiate and control a Nuclear fission, fission nuclear chain reaction. They are used for Nuclear power, commercial electricity, nuclear marine propulsion, marine propulsion, Weapons-grade plutonium, weapons ...

.

In September 1960, Salam confided Khan about establishing a research institute dedicated towards advancement of mathematical sciences

The Mathematical Sciences are a group of areas of study that includes, in addition to mathematics, those academic disciplines that are primarily mathematical in nature but may not be universally considered subfields of mathematics proper.

Statisti ...

under IAEA which Khan immediately supported the idea by lobbying at IAEA for financial funding and sponsorship– thus founding of the International Center for Theoretical Physics (ICTP). The idea mostly met with favorable views from the member countries of the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

's scientific committee though one of its influential member— Isidor Rabi from the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

— opposed the idea of establishment of ICTP. It was Khan who convinced Sigvard Eklund, Director of the International Atomic Energy Agency, to intervene in this matter that ultimately led to the establishment of the International Center for Theoretical Physics in Trieste

Trieste ( , ; ) is a city and seaport in northeastern Italy. It is the capital and largest city of the Regions of Italy#Autonomous regions with special statute, autonomous region of Friuli-Venezia Giulia, as well as of the Province of Trieste, ...

in Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

. The IAEA eventually entrusted Khan to oversee the construction of the ICTP in 1967, and played an instrumental role in establishing the annual summer conference on science in 1976 on Salam's advice.

Even after his retirement from the PAEC, Khan remained concern with the physics education in his country, joining the faculty of the Institute of Engineering and Applied Sciences to instruct courses on physics in 1997— the university that he oversaw its academic programs in 1976 as Center for Nuclear Studies. In 1999, Khan was invited as a guest speaker at the opening ceremony of the National Center for Physics— the national laboratory site— that works in close proximity with the ICTP in Italy. In 1967, Khan and Salam had prepared a proposal for setting up a fuel cycle facility and plutonium reprocessing plant to address the energy consumption demand— the proposal was deferred by Ayub administration on economic grounds.

Zulfikar Ali Bhutto's trusted aide

After his visit to the Bhabha Atomic Research Centre in Trombay as part of the IAEA inspection in 1964 and the second war with India in 1965, Khan became increasingly concerned about politics and international affairs. Eventually, Khan voiced his concerns to theGovernment of Pakistan

The Government of Pakistan () (abbreviated as GoP), constitutionally known as the Federal Government, commonly known as the Centre, is the national authority of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, a federal republic located in South Asia, con ...

when he met with Zulfikar Ali Bhutto

Zulfikar Ali Bhutto (5 January 1928 – 4 April 1979) was a Pakistani barrister and politician who served as the fourth president of Pakistan from 1971 to 1973 and later as the ninth Prime Minister of Pakistan, prime minister of Pakistan from 19 ...

(Foreign Minister

In many countries, the ministry of foreign affairs (abbreviated as MFA or MOFA) is the highest government department exclusively or primarily responsible for the state's foreign policy and relations, diplomacy, bilateral, and multilateral r ...

in Ayub administration at that time) in Vienna about the possible acquisition of nuclear deterrent to address the nuclear threat from India.

On 11 December 1965, Bhutto arranged a meeting between Khan and President Ayub Khan at the Dorchester Hotel in London where Khan made unsuccessful attempt in try convincing the President to pursue nuclear deterrent despite pointing out cheap cost estimates for the acquiring the nuclear capability. At the meeting, President Ayub Khan downplayed the warnings and swiftly dismissed the offer while believing that Pakistan "was too poor to spend" so much money and ended the meeting saying that, if needed, Pakistan would "somehow buy it off the shelf". After the meeting, Khan met with Bhutto and informed him about meeting with Bhutto later quoting: "''Don't worry. Our turn will come''".

Throughout the 1970s and onwards, Khan was very sympathetic to Pakistan Peoples Party's political cause and President Bhutto had spoken highly of his services while promising to ensure federal funding of the national programs of nuclear weapons at the inauguration ceremony of Karachi Nuclear Power Plant– the first milestone towards the goal of making Pakistan a nuclear power on 28 November 1972.In 1978, Khan told them that the design process of the bomb was completed and Bhutto expected the nuclear test in August 1978. Khan then told Murtaza and Benazir that the tests were moved to December 1978, but delayed indefinitely due to political and diplomatic considerations of the country. Benazir Bhutto, however, continued her ties with Khan and awarded him the Hilal-i-Imtiaz in 1989 for his services to Pakistan's nuclear program in developing nuclear fuel cycle technology.S.K. Pasha, "Solar Energy and the Guests at KANUPP Opening", Morning News (Karachi), 29 November 1972. His left-wing association with the Peoples Party continue even after turnover of federal government by the Pakistani military in 1977 as Khan visited Bhutto various times in Adiala State Prison to inform him about the status of the program.

Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission (PAEC)

In 1972, Khan officially resigned from his directorship of the IAEA's reactor division when he was appointed as chairman of the Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission, replacing I. H. Usmani who was appointed secretary at the Ministry of Science in the Bhutto administration. By March 1972, Khan submitted a detailed roadmap to the Ministry of Energy (MoE) that envisioned linking the country's entire energy infrastructure to nuclear power sources as a substitute for energy consumption dependent on hydroelectricity. Mahmood, S. Bashiruddin, ''Speeches delivered on Munir Ahmad Khan Memorial Reference'', Institute of Nuclear Science and Technology in Islamabad, 28 April 2007. On 28 November 1972, Khan, together with Salam, accompanied President Bhutto to the inauguration ceremony for the Karachi Nuclear Power Plant (KANUPP)–the first milestone towards the goal of making Pakistan a nuclear power. Khan played a crucial role in keeping grid operations running for the Karachi Nuclear Power Plant after its chief scientist, Wazed Miah, had hissecurity clearance

A security clearance is a status granted to individuals allowing them access to classified information (state or organizational secrets) or to restricted areas, after completion of a thorough background check. The term "security clearance" is ...

revoked, and was forced to migrate to Bangladesh

Bangladesh, officially the People's Republic of Bangladesh, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by population, eighth-most populous country in the world and among the List of countries and dependencies by ...

. Khan then established a training facility in cooperation with the Karachi University to fill the void created by Bengali engineers. When Canadian General Electric stopped the supply of uranium and machine components for the Karachi Nuclear Power Plant in 1976, Khan worked on developing the nuclear fuel cycle without foreign assistance to make sure that the plant kept generating power for the nation's electricity grid by establishing the fuel cycle facility near the power plant in cooperation with the Karachi University.

In 1975–76, Khan entered into diplomacy with France's Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy Commission (CEA) for acquiring a reprocessing plant for production of reactor-grade plutonium, and a commercial nuclear power plant in Chashma, advising the federal government on key matters regarding the operations of these plants. Negotiations with France over the reprocessing plant was extremely controversial at home with the United States later intervening in the matter between Pakistan and France over fears of nuclear proliferation. Khan's relations with the Bhutto administration often soured because Khan wanted to engage the CEA long enough until PAEC was able to learn to design and construct the plants itself, while Bhutto administration officials wanted the plants based solely on imports from France. In 1973–77, Khan entered in negotiation with CEA for Chashma Nuclear Power Plant, having advised the MoE to sign the IAEA safeguard agreement with France to ensure the foreign funding of the plant, which the PAEC was designing but the CEA left the project with PAEC taking control of the entire project despite Khan's urging to French CEA to fulfill its contractual obligations. With France's offing, Khan eventually negotiated with China over this project's foreign funding in 1985–86.

In 1977, Khan fiercely opposed the French CEA's proposal to alter the design of the reprocessing plant so that it would produce a mixed reactor-grade plutonium with natural uranium, which would stop the production of military-grade plutonium. Khan advised the federal government to refuse the modification plan as the PAEC had already build the plant itself and manufactured components from local industry— this plant was built by PAEC and is now known as Khushab Nuclear Complex.

In 1982, Khan expanded the scope of nuclear technology for harnessing the agriculture and food irradiation process by establishing the Nuclear Institute for Food and Agriculture (NIAB) in Peshawar while moving PAEC's scope towards medical physics

Medical physics deals with the application of the concepts and methods of physics to the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of human diseases with a specific goal of improving human health and well-being. Since 2008, medical physics has been incl ...

research by securing federal funding for various cancer research hospitals in Pakistan in 1983–91.

1971 war and atomic bomb project

On 16 December 1971, Pakistan ultimately called for a unilateral ceasefire to end their third war with India when the Yahya Khan administration acceded to the unconditional surrender of the Pakistani military on the eastern front of the war, resulting in thesecession

Secession is the formal withdrawal of a group from a Polity, political entity. The process begins once a group proclaims an act of secession (such as a declaration of independence). A secession attempt might be violent or peaceful, but the goal i ...

of East Pakistan as the independent country Bangladesh

Bangladesh, officially the People's Republic of Bangladesh, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by population, eighth-most populous country in the world and among the List of countries and dependencies by ...

, from the Federation of Pakistan.

Upon learning the news, Khan returned to Pakistan from Austria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

, landing in Quetta

Quetta is the capital and largest city of the Pakistani province of Balochistan. It is the ninth largest city in Pakistan, with an estimated population of over 1.6 million in 2024. It is situated in the south-west of the country, lying in a ...

to initially attend the winter session to meet with PAEC's scientists before being flown to Multan

Multan is the List of cities in Punjab, Pakistan by population, fifth-most populous city in the Punjab, Pakistan, Punjab province of Pakistan. Located along the eastern bank of the Chenab River, it is the List of cities in Pakistan by populatio ...

. This winter session, known as the ''"Multan meeting"'', was arranged by Abdus Salam for scientists to meet with President Bhutto who, on 20 January 1972, authorized the crash program to develop an atomic bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission or atomic bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear weapon), producing a nuclear expl ...

for the sake of "national survival". President Bhutto invited Khan to take over the weapons program work—a task that Khan threw himself into with full vigor. In spite of having been unknown to many senior scientists, Khan busied himself on development of the program, initially assisting in complicated fast neutron calculations. Although Khan was not a doctorate holder, his extensive experience as a nuclear engineer at the reactor physics division at IAEA enabled him to direct senior scientists working under him on classified projects. Mehmud, Salim, ''Remembering Unsung Heroes: Munir Ahmed Khan'', Institute of Nuclear Science and Technology, 28 April 2007 In a short time, Khan impressed the conservatively-aligned Pakistani military with the breadth of his knowledge, and grasp of engineering, ordnance, metallurgy, chemistry, and interdisciplinary projects that would distinguish from the field of physics.

In December 1972, Abdus Salam directed two theoretical physicists, Riazuddin and Masud Ahmad, at the International Center for Theoretical Physics to report to Khan on their return to Pakistan where they formed the "Theoretical Physics Group" (TPG) in PAEC— this division eventually went to commit itself to perform tedious mathematical calculations on fast neutron temperatures. Salam, who saw this program as an opportunity to ensure federal government's interest and funding to promote scientific activities in his country, took over the TPG's directorship with Khan assisting in the solutions

Solution may refer to:

* Solution (chemistry), a mixture where one substance is dissolved in another

* Solution (equation), in mathematics

** Numerical solution, in numerical analysis, approximate solutions within specified error bounds

* Solutio ...

for fast neutron calculations and binding energy measurements of the atomic bomb.

The research operational scope of the Pakistan Institute of Nuclear Science and Technology, the national laboratory site, was well expanded from a school building to several buildings, which were erected in great haste, in Nilore.Rehman, Inam-ur, ''Remembering Unsung Heroes: Munir Ahmed Khan'', Institute of Nuclear Science and Technology, 28 April 2007 At this laboratory site, Khan assembled a large group of the top physicists of the time from the Quaid-e-Azam University

Quaid-i-Azam University (QAU), founded as the University of Islamabad, is a Public university, public research university in Islamabad, Pakistan. Founded as the University of Islamabad in 1967, it was initially dedicated to postgraduate educat ...

, where he invited them to conduct classified research with federal funding rather than teaching the fields of physics in the university classrooms.

At that meeting, the word " ''bomb''" was never used but it was understood the need for the development of explosive lenses, a sub-critical sphere of fissile material could be squeezed into a smaller and denser form, and the reflective tamper, the metal needed to scatter only very short distances, so the critical mass would be assembled in much less time. This project required manufacturing and machining of key parts that necessitated another laboratory site, leading Khan, assisted by Salam, to meet with

Lieutenant-General

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the battlefield, who was normall ...

Qamar Ali Mirza, Engineer-in-Chief of the Corps of Engineers. Ensuring the Corps would handle its part in the atomic bomb project, Khan requested the construction of the Metallurgical Laboratory (ML) near the Pakistan Ordnance Factories

The Pakistan Ordnance Factories (POF) is a major firearms and a defence contractor headquartered in Wah Cantt, Punjab, Pakistan. Described as "the largest defence industrial complex under the Ministry of Defence Production, producing convent ...

in Wah. Eventually, the project was relocated to the ML with Qureshi and Zaman moving their staff and machine shops from the Institute of Nuclear Science and Technology with assistance from the military.

In March 1974, Khan took over the work of TPG from Salam when Salam left the country in protest over a constitutional amendment

A constitutional amendment (or constitutional alteration) is a modification of the constitution of a polity, organization or other type of entity. Amendments are often interwoven into the relevant sections of an existing constitution, directly alt ...

, with Riazuddin leading the studies. During this time, Khan launched a uranium enrichment program which was seen as a backup for fissile material production, delegating this project to Bashiruddin Mahmood who focused on gaseous diffusion and Shaukat Hameed Khan, who pioneered the laser isotope separation method. The uranium enrichment project accelerated when India announced "Smiling Buddha

Smiling Buddha (Ministry of External Affairs (India), MEA designation: Pokhran-I) was the code name of India's first successful Nuclear weapons testing, nuclear weapon test on 18 May 1974. The nuclear fission bomb was detonated in the Pokhran#P ...

", a surprise weapons test, with Khan confirming the test's radiation emission through data provided by I. H. Qureshi on 18 May 1974. Sensing the importance of this test, Khan called a meeting between Hameed Khan and Mahmood who analyzed different methods but finally agreed on gaseous diffusion over laser isotope separation, that continued at its own pace under Hameed Khan in October 1974. In 1975, Khalil Qureshi, a physical chemist, was asked to join the uranium project under Mehmood who did most of the calculations on military-grade uranium. In 1976, Dr. Abdul Qadeer Khan

Abdul Qadeer Khan (1 April 1936 – 10 October 2021) was a Pakistani Nuclear physics, nuclear physicist and metallurgist, metallurgical engineer. He is colloquially known as the "father of Pakistan and weapons of mass destruction, Pakistan's ...

, a nuclear metallurgist, joined the program but was given the task to build the task pf developing nuclear capability due to his indepth knwowldge of advance nuclear technology, that led to the program being moved to the independent self-sufficient Khan Research Laboratories in Kahuta with A. Q. Khan being its chief scientist under the Corps of Engineers.

By 1976–77, the entire atomic bomb program was quickly transferred from the civilian Ministry of Science, to military control with Khan, as chief scientist, remaining the technical director of the overall bomb program.

Nuclear tests: Chagai-II

In 1975, AQ Khan, in discussion with the Corps of Engineers, had selected the mountain ranges in Balochistan for the isolation needed to maintain security and secrecy. He tasked Ishfaq Ahmad and Ahsan Mubarak, a

In 1975, AQ Khan, in discussion with the Corps of Engineers, had selected the mountain ranges in Balochistan for the isolation needed to maintain security and secrecy. He tasked Ishfaq Ahmad and Ahsan Mubarak, a seismologist

Seismology (; from Ancient Greek σεισμός (''seismós'') meaning "earthquake" and -λογία (''-logía'') meaning "study of") is the scientific study of earthquakes (or generally, quakes) and the generation and propagation of elastic ...

, to conduct a geological survey of mountain ranges with help from the Corps of Engineers and Geological Survey of Pakistan. Scouting for a test site in 1976, the team searched for a high altitude and rocky granite

Granite ( ) is a coarse-grained (phanerite, phaneritic) intrusive rock, intrusive igneous rock composed mostly of quartz, alkali feldspar, and plagioclase. It forms from magma with a high content of silica and alkali metal oxides that slowly coo ...

mountain that would be suitable to take more than ~40 kn of nuclear blast yield, ultimately candidating the remote, isolated, and unpopulated ranges at Chagai, Kala-Chitta, Kharan, and Kirana in 1977–78.

The joint work of the various groups at the Institute of Nuclear Science and Technology led to the first cold-test of their atomic bomb design on 11 March 1983, codenamed: '' Kirana-I''. A "''cold test''" is a subcritical test of a nuclear weapon design without the fissile material

In nuclear engineering, fissile material is material that can undergo nuclear fission when struck by a neutron of low energy. A self-sustaining thermal chain reaction can only be achieved with fissile material. The predominant neutron energy i ...

inserted to prevent any nuclear fission

Nuclear fission is a reaction in which the nucleus of an atom splits into two or more smaller nuclei. The fission process often produces gamma photons, and releases a very large amount of energy even by the energetic standards of radioactiv ...

."Pakistan Became a Nuclear State in 1983-Dr. Samar", The Nation,(Islamabad) 2 May 2003 Retrieved 6 August 2009. Preparations for the tests and engineering calculations were validated by Khan with Ahmad leading the team of scientists; other invitees to witness the test included Ghulam Ishaq Khan, Major-General Michael O'Brian from the Pakistan Air Force (PAF), General K. M. Arif, Chief of Army Staff at that time, and other senior military officers.

Khan recalled to his biographer, decades later, that while witnessing the test:

Despite many difficulties and political opposition, Khan lobbied and emphasized the importance of plutonium and countered scientific opposition led by fellow scientist Abdul Qadeer Khan

Abdul Qadeer Khan (1 April 1936 – 10 October 2021) was a Pakistani Nuclear physics, nuclear physicist and metallurgist, metallurgical engineer. He is colloquially known as the "father of Pakistan and weapons of mass destruction, Pakistan's ...

, who opposed the plutonium route, favoring the uranium atomic bomb. From the start, studies were concentrated towards feasibility of the plutonium " implosion-type" design, a device known as the Chagai-II in 1998. Khan, together with Abdul Qadeer, worked on his proposal for viability of " gun-type" designs— a simpler mechanism that only had to work with U235, but there was a possibility for that weapon's chain reaction to be a " nuclear fizzle", therefore they abandoned gun-type studies in favor of the implosion-type. Khan's advocacy for the plutonium implosion-type design was validated with the test of a plutonium device that was called '' Chagai-II'' to artificially produce nuclear fission— this nuclear device had the largest yield of all the boosted fission uranium devices.

President Zia, despite Khan's political orientation, widely respected Khan for his knowledge and understanding of national security issues when he spoke highly of him during a visit to the Institute of Nuclear Science and Technology in November 1986:

Arms race and diplomacy with India

Despite the issuance of public statements by Pakistani politicians, the atomic bomb program was, nonetheless, kept top secret from their public and Khan became a national spokesman for science in the federal government with a new type of technocratic role. He lobbied for independence of the Space Research Commission from the PAEC and provided narrative for launching the nation's first satellite to meet and compete with India in the space race in Asia. Unlike his predecessor, Khan advocated for anarms race

An arms race occurs when two or more groups compete in military superiority. It consists of a competition between two or more State (polity), states to have superior armed forces, concerning production of weapons, the growth of a military, and ...

with India to ensure the balance of power by securing funding for military "black" projects and national security programs. By 1979, Khan removed PAEC's role in defense production moving the Wah Group, that designed the tactical nuclear weapons in 1986, from ML to KRL, and also founded the National Defence Complex (NDC) in 1991.

At various international conferences, Khan was very critical of the Indian nuclear program as he perceived that it had military purposes, and viewed it as a threat to the region's stability, while he defended Pakistan's non-nuclear weapon policy as well as their nuclear tests when he summed up his thoughts:

When Israel's Operation Opera surprise airstrike destroyed the Osirak Nuclear Plant in Iraq

Iraq, officially the Republic of Iraq, is a country in West Asia. It is bordered by Saudi Arabia to Iraq–Saudi Arabia border, the south, Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq border, the east, the Persian Gulf and ...

in 1981, the Pakistani intelligence community learned of the Indian plans to attack Pakistan's national laboratory sites. Khan was confided in by diplomat Abdul Sattar over this intelligence report in 1983. Sattar, A., ''Munir Ahmad Khan Memorial Reference'', Institute of Nuclear Science and Technology, 28 April 2007 While attending a conference on nuclear safety in Austria, Khan became acquainted with Indian physicist Raja Ramanna when discussing topics in nuclear physics, briefly inviting the latter for a dinner at the Imperial Hotel where Ramanna confirmed the veracity of the information.

At this dinner, Khan reportedly warned Ramanna about a possible retaliatory nuclear strike at Trombay if the Indian plans were to go ahead and urged Ramanna to relay this message to Indira Gandhi

Indira Priyadarshini Gandhi (Given name, ''née'' Nehru; 19 November 1917 – 31 October 1984) was an Indian politician and stateswoman who served as the Prime Minister of India, prime minister of India from 1966 to 1977 and again from 1980 un ...

, the Indian Prime Minister at that time. The message was delivered to the Indian Prime Minister's Office, and the Non-Nuclear Aggression Agreement treaty was signed to prevent nuclear accidents and accidental detonations between India and Pakistan in 1987.

Government work, academia and advocacy

In the 1980s, Khan emblemed in the federal government with a new type of technocratic role, a science adviser, becoming the spokesman of national science policy and advised the federal government to sign an agreement to ensure federal funding from China to commission the Chashma Nuclear Power Plant in 1987. In 1990, Khan advised the Benazir's administration to entered in negotiation with France over construction of nuclear power plant in Chashma. As chairing the PAEC in 1972, Khan played a crucial role in expanding the "''Reactor School''" which was housed in a lecture room located at the Institute of Nuclear Science and Technology in Nilore and had only one faculty member, Dr. Inam-ur-Rehman, who often traveled to the United States to teach engineering at theMississippi State University

Mississippi State University for Agriculture and Applied Science, commonly known as Mississippi State University (MSU), is a Public university, public land-grant university, land-grant research university in Mississippi State, Mississippi, Un ...

. In 1976, Khan moved the ''Reactor School'' in Islamabad, renaming it as " Centre for Nuclear Studies (CNS)" and took the professorship in physics, as an unpaid part-time employment, alongside Dr. Inam-ur-Rehman.

After his retirement from PAEC in 1991, Khan went to academia when he joined the faculty at the center for nuclear studies as a full-time professor to teach courses on physics while continuing to push for the CNS to be granted as university by the Higher Education Commission. In 1997, his dream was fulfilled when the federal government accepted his recommendation by granting the status of center for nuclear studies as a public university

A public university, state university, or public college is a university or college that is State ownership, owned by the state or receives significant funding from a government. Whether a national university is considered public varies from o ...

and renaming it as the Institute of Engineering and Applied Sciences (PIEAS).

Final years

Death and legacy

In 1972, Khan bought an estate in Islamabad and then died following complications from heart surgery, aged 72, on 22 April 1999. He is survived by his wife, Thera, three children and four grandchildren.

When Abdus Salam was ejected from his position in 1974, Khan symbolized of many scientists thinking they could control how other peers would use their research. During the timeline of atomic bomb program, Khan was seen as a symbol of both

In 1972, Khan bought an estate in Islamabad and then died following complications from heart surgery, aged 72, on 22 April 1999. He is survived by his wife, Thera, three children and four grandchildren.

When Abdus Salam was ejected from his position in 1974, Khan symbolized of many scientists thinking they could control how other peers would use their research. During the timeline of atomic bomb program, Khan was seen as a symbol of both moral responsibility

In philosophy, moral responsibility is the status of morality, morally desert (philosophy), deserving praise, blame, reward (psychology), reward, or punishment for an act or omission in accordance with one's moral obligations. Deciding what (if ...

of scientists, and to the contribution to the rise of Pakistan's science while preventing the politicization of the project. Popular depiction of Khan's views on nuclear proliferation as a confrontation between right-wing militarists who viewed that security interests with Western world

The Western world, also known as the West, primarily refers to various nations and state (polity), states in Western Europe, Northern America, and Australasia; with some debate as to whether those in Eastern Europe and Latin America also const ...

incompatible (symbolized by Abdul Qadeer Khan

Abdul Qadeer Khan (1 April 1936 – 10 October 2021) was a Pakistani Nuclear physics, nuclear physicist and metallurgist, metallurgical engineer. He is colloquially known as the "father of Pakistan and weapons of mass destruction, Pakistan's ...

) and left-wing intellectuals who viewed maintaining alliances with Western world (symbolized by Munir Khan) over the moral question of weapons of mass destruction

A weapon of mass destruction (WMD) is a Biological agent, biological, chemical weapon, chemical, Radiological weapon, radiological, nuclear weapon, nuclear, or any other weapon that can kill or significantly harm many people or cause great dam ...

.

In the 1990s, Khan was increasingly concerned about the potential danger that scientific inventions in nuclear applications could pose to humanity and stressed the difficulty of managing the power of scientific knowledge between scientists and lawmakers in an atmosphere in which the exchange of scientific ideas was hobbled by political concerns. During his time working in atomic bomb program, Khan was obsessed with secrecy and refused to meet with many journalists while he encouraged several scientists working on the classified projects to stay away from televised press and public to due to the sensitivity of their job.

As a scientist, Khan is remembered by his peers as brilliant researcher and engaging teacher, the founder of applied physics

Applied physics is the application of physics to solve scientific or engineering problems. It is usually considered a bridge or a connection between physics and engineering.

"Applied" is distinguished from "pure" by a subtle combination of fac ...

in Pakistan. In 2007, Farhatullah Babar portrayed Khan as "tragic fate but consciously genius". Babar, F., ''Remembering Unsung Heroes: Munir Ahmed Khan'', Institute of Nuclear Science and Technology, 28 April 2007 After years of urging of many of Khan's colleagues in PAEC and his powerful political friends who had ascended to power in the government, President Asif Ali Zardari bestowed and honored Khan with the prestigious and highest civilian state award, Nishan-e-Imtiaz

The Nishan-e-Imtiaz (; ) is one of the state organized Civil decorations of Pakistan, civil decorations of Pakistan.

It is awarded for achievements towards world recognition for Pakistan or outstanding service for the country. However, the awa ...

in 2012 as a gesture of political rehabilitation.

One of Khan's achievements is his technical leadership of the atomic bomb program, roughly modelled on the ''Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development program undertaken during World War II to produce the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States in collaboration with the United Kingdom and Canada.

From 1942 to 1946, the ...

'' that prevented the exploitation and politicization of the program in the hands of politicians, lawmakers, and military officials. The national project under Khan's technical directorship focused on developing his nation's atomic weapons and a diversified the nuclear technology for medical usage while he regarded this clandestine atomic bomb project as "building science and technology for Pakistan".

As military and public policy maker, Khan was a technocrat leader in a shift between science and military, and the emergence of the concept of the big science in Pakistan. During the Cold war, scientists became involved in military research on unprecedented degree, because of the threat communism

Communism () is a political sociology, sociopolitical, political philosophy, philosophical, and economic ideology, economic ideology within the history of socialism, socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a ...

from Afghanistan and Indian integration posed to Pakistan, scientists volunteered in great numbers both for technological and organizational assistance to Pakistan's efforts that resulted in powerful tools such as laser science

Laser science or laser physics is a branch of optics that describes the theory and practice of lasers.

Laser science is principally concerned with quantum electronics, laser construction, optical cavity design, the physics of producing a popula ...

, the proximity fuse and operations research. As a cultured and intellectual physicist

A physicist is a scientist who specializes in the field of physics, which encompasses the interactions of matter and energy at all length and time scales in the physical universe. Physicists generally are interested in the root or ultimate cau ...

who became a disciplined military organizer, Khan represented the shift away from the idea that scientists had their "head in the clouds" and that knowledge on such previously esoteric subjects as the composition of the atomic nucleus had no "real-world" applications.

Throughout his life, Khan was honored with his nation's awards and honors:

* Nishan-e-Imtiaz

The Nishan-e-Imtiaz (; ) is one of the state organized Civil decorations of Pakistan, civil decorations of Pakistan.

It is awarded for achievements towards world recognition for Pakistan or outstanding service for the country. However, the awa ...

(2012; Posthumous)

* Hilal-e-Imtiaz (1989)

* Gold medal

A gold medal is a medal awarded for highest achievement in a non-military field. Its name derives from the use of at least a fraction of gold in form of plating or alloying in its manufacture.

Since the eighteenth century, gold medals have b ...

, PAS (1992)

* Fulbright Award (1951)

* Roll of Honor, GCU (1946)

* Fellowship, Pakistan Nuclear Society (1999)

* Fellowship, American Nuclear Society (1999)

* Fellowship, Pakistan Institute of Electrical Engineers (1992)

* Fellowship, Sigma Xi

Sigma Xi, The Scientific Research Honor Society () is an international non-profit honor society for scientists and engineers. Sigma Xi was founded at Cornell University by a faculty member and graduate students in 1886 and is one of the oldest ...

Society (1953–1956)

* Fellowship Rotary International

Rotary International is one of the largest service organizations in the world. The self-declared mission of Rotary, as stated on its website, is to "provide service to others, promote integrity, and advance world understanding, goodwill, and p ...

(1951)

Quotes by Khan

* ''"We have to understand that nuclear weapons are not a play thing to be bandied publicly. They have to be treated with respect and responsibility. While they can destroy the enemy, they can also invite self destruction."'' * ''"While we were building capabilities in the nuclear fuel cycle, we started in parallel the design of a nuclear device, with its trigger mechanism, physics calculations, production of metal, making precision mechanical components, high-speed electronics, diagnostics, and testing facilities. For each one of them, we established different laboratories".'' * ''"Many sources were tapped after the decision to go nuclear. We were simultaneously working on 20 labs and projects under the administrative control of PAEC, every one the size of Khan Research Laboratories."'' * ''"On 11 March 1983, we successfully conducted the first cold test of a working nuclear device. That evening, I went to General Zia with the news that Pakistan was now ready to make a nuclear device."''References

;Notes ;CitationsAnecdotes

Biographical sketch

Scientist dr. Munir Ahmad

Who's the father of the atomic bomb- IISS

IN Memoriam: Munir Ahmad Khan, IAEA

The Nuclear Supremo Munir Khan

Mineral Research Laboratories

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * *External links

PAEC official page

, - {{DEFAULTSORT:Khan, Munir Ahmad 1926 births 1999 deaths Pashtun scientists People from Kasur District Scientists from Lahore Government College University, Lahore alumni University of the Punjab alumni 20th-century Pakistani engineers Pakistani electrical engineers Academic staff of the University of Engineering and Technology, Lahore Pakistani expatriates in the United States North Carolina State University alumni Pakistani physicists Illinois Institute of Technology alumni Pakistani nuclear engineers International Atomic Energy Agency officials Pakistani expatriates in Austria Chairpersons of the Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission Pakistani nuclear physicists Weapons scientists and engineers Quantum physicists Theoretical physicists Scientists from Islamabad Academic staff of Pakistan Institute of Engineering and Applied Sciences Founders of Pakistani schools and colleges Fellows of Pakistan Academy of Sciences Recipients of Hilal-i-Imtiaz Recipients of Nishan-e-Imtiaz Members of the Pakistan Philosophical Congress Nuclear weapons scientists and engineers People from Punjab Province (British India)