Moncure Conway on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

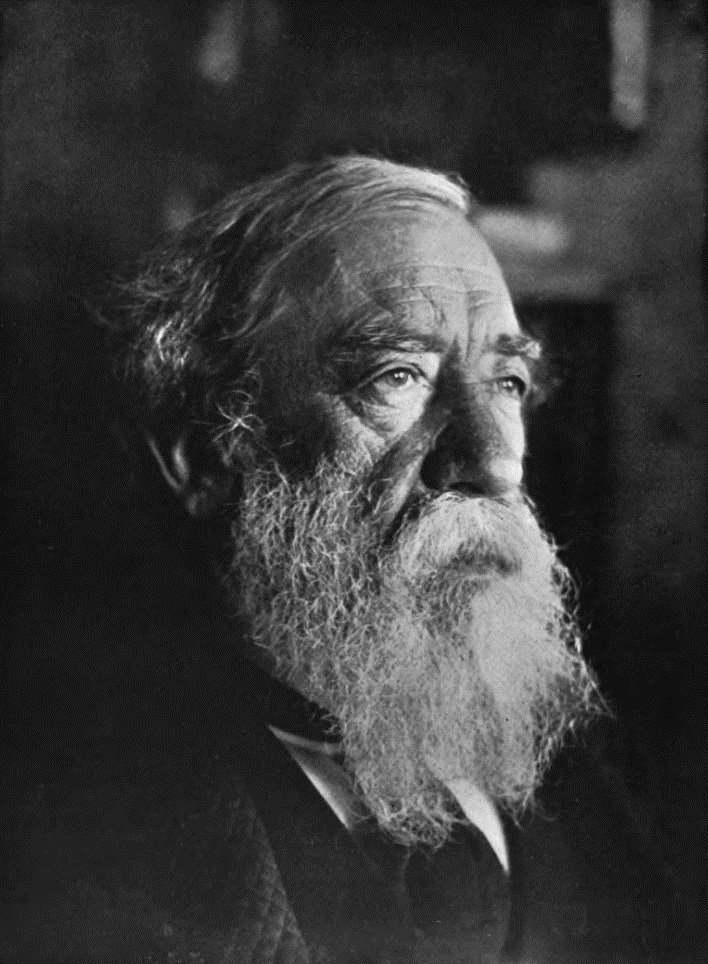

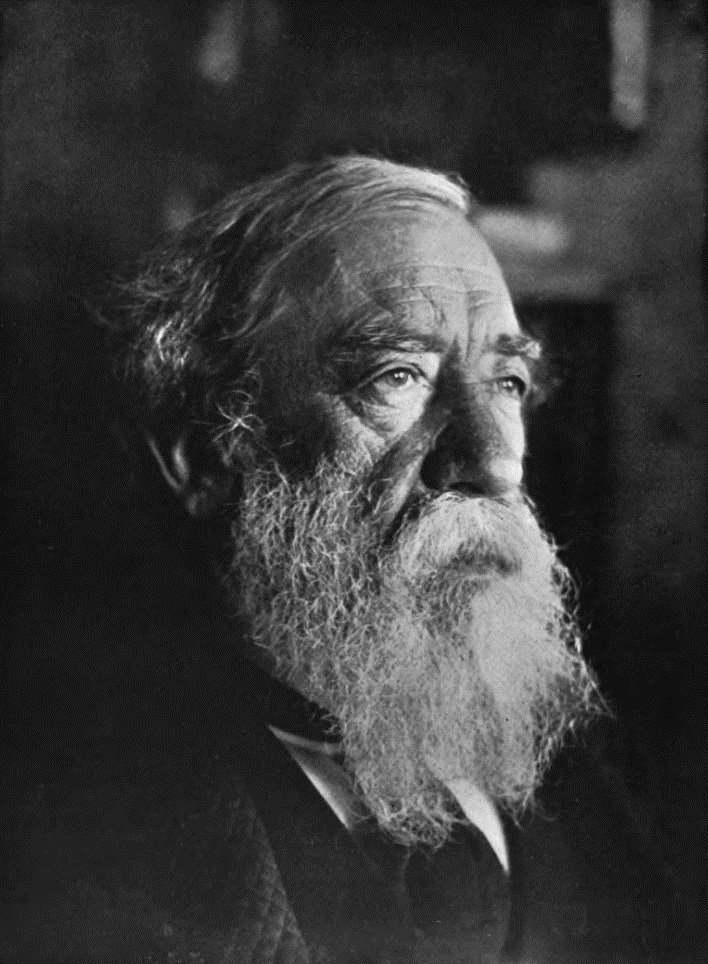

Moncure Daniel Conway (March 17, 1832 – November 15, 1907) was an American

Rather than go back to America, where Conway no longer felt welcome as a suspected traitor to his childhood Virginia friends and neighbors and he paid someone to take his place after being drafted to serve in the Union army, Conway traveled to Italy. There, he reunited with his wife and children in

Rather than go back to America, where Conway no longer felt welcome as a suspected traitor to his childhood Virginia friends and neighbors and he paid someone to take his place after being drafted to serve in the Union army, Conway traveled to Italy. There, he reunited with his wife and children in

online edition

*''The Natural History of the Devil'' (1859) *''The Rejected Stone: or, Insurrection vs. Resurrection in America, By a Native of Virginia'' (1861

online edition

*''The Golden Hour'' (1862

online edition

*''Testimonies Concerning Slavery'' (1864

online edition

*''The Earthward Pilgrimage'' (1870

online edition

*''Republican Superstitions as Illustrated in the Political History of America'' (1872

online edition

*''Christianity'' (1876

online edition

*''Idols and Ideals, with an Essay on Christianity'' (1877

online edition

*''Demonology and Devil Lore'' (2 vols., 1878

*''A Necklace of Stories'' (1880

online edition

*''Thomas Carlyle'' (1881

online edition

*''The Wandering Jew'' (1881

online edition

*''Emerson at Home and Abroad'' (1882

online edition

*''Travels in South Kensington: with Notes on Decorative Art and Rrchitecture in England'' (1882

online edition

*''Lessons for the Day'' (1882

online edition

*''The Saint Patrick Myth (1883)'' *''Pine and Palm: A Novel'' (2 vols., 1887

online edition

*''Life and Papers of Edmund Randolph'' (1888

online edition

*''Life of Nathaniel Hawthorne'' (1890

online edition

*''George Washington's Rules of Civility: Traced to their Sources and Restored'' (1890

online edition

*''The Life of Thomas Paine'' with an unpublished sketch of Paine by

online edition

*''The Writings of Thomas Paine'' (1894

online edition

*''Solomon and Solomonic Literature'' (1899

online edition

*''Autobiography, Memories and Experiences'' (2 vols., 1904

online edition

*''My Pilgrimage to the Wise Men of the East'' (1906

online edition

Dictionary of Unitarian & Universalist Biography

- Article by Charles A. Howe *Burtis, Mary Elizabeth. ''Moncure Conway, 1832-1907.'' New Brunswick, Rutgers University Press, 1952. *d'Entremont, John. ''Southern Emancipator: Moncure Conway: The American Years, 1832-1865.'' Oxford University Press, 1987. *Easton, Loyd D. ''Hegel's First American Followers: The Ohio Hegelians: J.D. Stallo, Peter Kaufmann, Moncure Conway, August Willich.'' Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 1966. *Good, James A., ed. ''Moncure Daniel Conway: Autobiography and Miscellaneous Writings.'' 3 volumes. Bristol, UK: Thoemmes Press, 2003. *Good, James A., ed. ''The Ohio Hegelians.'' 3 volumes. Bristol, UK: Thoemmes Press, 2004. *Walker, Peter. ''Moral Choices: Memory, Desire, and Imagination in Nineteenth-Century American Abolition.'' Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1978. *

Moncure Conway Foundation

Moncure Conway in ''Encyclopedia Virginia''

* * *

''Wandering Jew and Wandering Jeweess''

screenplays {{DEFAULTSORT:Conway, Moncure Daniel 1832 births 1907 deaths 19th-century American philosophers American abolitionists American Methodist clergy American Unitarian clergy Critics of Theosophy Dickinson College alumni Ethical movement Freethought writers Harvard Divinity School alumni Hegelian philosophers Moncure family People associated with Conway Hall Ethical Society People from Falmouth, Virginia Burials at Kensico Cemetery Members of the American Academy of Arts and Letters

abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was Kingdom of France, France in 1315, but it was later used ...

minister and radical writer. At various times Methodist

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a Protestant Christianity, Christian Christian tradition, tradition whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's brother ...

, Unitarian, and a Freethinker, he descended from patriotic and patrician families of Virginia and Maryland but spent most of the final four decades of his life abroad in England and France, where he wrote biographies of Edmund Randolph

Edmund Jennings Randolph (August 10, 1753 September 12, 1813) was a Founding Father of the United States, attorney, and the seventh Governor of Virginia. As a delegate from Virginia, he attended the Constitutional Convention and helped to cre ...

, Nathaniel Hawthorne

Nathaniel Hawthorne (né Hathorne; July 4, 1804 – May 19, 1864) was an American novelist and short story writer. His works often focus on history, morality, and religion.

He was born in 1804 in Salem, Massachusetts, from a family long associat ...

and Thomas Paine

Thomas Paine (born Thomas Pain; – In the contemporary record as noted by Conway, Paine's birth date is given as January 29, 1736–37. Common practice was to use a dash or a slash to separate the old-style year from the new-style year. In ...

and his own autobiography. He led freethinkers in London's South Place Chapel, now Conway Hall

Conway Hall in Red Lion Square, London, is the headquarters of the Conway Hall Ethical Society. It is a Grade II listed building.

History

The building was commissioned by the South Place Ethical Society, which had previously been accommodated ...

.

Family

Conway's parents descended from theFirst Families of Virginia

The First Families of Virginia, or FFV, are a group of early settler families who became a socially and politically dominant group in the British Colony of Virginia and later the Commonwealth of Virginia. They descend from European colonists who ...

. His father, Walker Peyton Conway, was a wealthy slave-holding gentleman farmer, county judge, and state representative; his home, known as the Conway House, still stands at 305 King Street (also known as River Road), along the Rappahannock River

The Rappahannock River is a river in eastern Virginia, in the United States, approximately in length.U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed April 1, 2011 It traverses the enti ...

. Conway's mother, Margaret Stone Daniel Conway, was the granddaughter of Thomas Stone

Thomas Stone (1743 – October 5, 1787) was an American Founding Father, planter, politician, and lawyer who signed the United States Declaration of Independence as a delegate for Maryland. He later worked on the committee that formed the Arti ...

of Maryland (a signer of the Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of the territory of another state or failed state, or are breaka ...

), and in addition to running the household, also practiced homeopathy

Homeopathy or homoeopathy is a pseudoscientific system of alternative medicine. It was conceived in 1796 by the German physician Samuel Hahnemann. Its practitioners, called homeopaths or homeopathic physicians, believe that a substance that ...

, learned from her doctor father. Both parents were Methodists, his father having left the Episcopal church, his mother the Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a historically Reformed Protestant tradition named for its form of church government by representative assemblies of elders, known as "presbyters". Though other Reformed churches are structurally similar, the word ''Pr ...

, and they hosted Methodist meetings in their home until a suitable church was finally built in Fredericksburg. An uncle, Judge Eustace Conway, advocated states' rights in Virginia's General Assembly (as did Walter Conway). Another uncle, Richard C.L. Moncure, served on what later became the Virginia Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of Virginia is the highest court in the Commonwealth of Virginia. It primarily hears direct appeals in civil cases from the trial-level city and county circuit courts, as well as the criminal law, family law and administrativ ...

, was a layman in the Episcopal Church, and became known for his integrity and hatred of intolerance. His great-uncle, Peter Vivian Daniel

Peter Vivian Daniel (April 24, 1784 – May 31, 1860) was an American jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States.

Early life and education

Peter Vivian Daniel was born in 1784 at "Crow's Nest", a p ...

, served on the United States Supreme Court, where he upheld slavery and the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850

The Fugitive Slave Act or Fugitive Slave Law was a law passed by the 31st United States Congress on September 18, 1850, as part of the Compromise of 1850 between Southern interests in slavery and Northern Free-Soilers.

The Act was one ...

, including in the Dred Scott Decision

''Dred Scott v. Sandford'', 60 U.S. (19 How.) 393 (1857), was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court that held the U.S. Constitution did not extend American citizenship to people of black African descent, and therefore they ...

of 1857.

Two of his three brothers later fought for the Confederacy. His opposition to slavery reportedly came from his mother's side of the family, including his great-grandfather Travers Daniel (justice of the Stafford Court, died 1824) and his mother herself (who fled to Easton, Pennsylvania

Easton is a city in and the county seat of Northampton County, Pennsylvania, United States. The city's population was 28,127 as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. Easton is located at the confluence of the Lehigh River and the Delawa ...

, and lived with her daughter and son-in-law Professor Marsh after the Civil War broke out) as well as from his boyhood experiences. Nonetheless, during his youth, Moncure Conway briefly took a pro-slavery position under the influence of a cousin, Richmond editor John Moncure Daniel

John Moncure Daniel (October 24, 1825 – March 30, 1865) was the US minister to the Kingdom of Sardinia in 1854-1861. However, he is best known for his role as the executive editor of the '' Richmond Examiner'', one of the chief newspapers of th ...

, himself a protege of Justice Daniel.

Early life

Conway was born inFalmouth, Virginia

Falmouth is a census-designated place (CDP) in Stafford County, Virginia, Stafford County, Virginia, United States. Situated on the north bank of the Rappahannock River at the falls, the community is north of and opposite the city of Fredericksb ...

.

After attending the Fredericksburg Classical and Mathematical Academy (alma mater of George Washington

George Washington (, 1799) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the first president of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797. As commander of the Continental Army, Washington led Patriot (American Revoluti ...

and other famous Virginians), Conway followed his elder brother to Methodist-affiliated Dickinson College

Dickinson College is a Private college, private Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, United States. Founded in 1773 as Carlisle Grammar School, Dickinson was chartered on September 9, 1783, ...

in Carlisle, Pennsylvania

Carlisle is a Borough (Pennsylvania), borough in and the county seat of Cumberland County, Pennsylvania, United States. Carlisle is located within the Cumberland Valley, a highly productive agricultural region. As of the 2020 United States census ...

, graduating in 1849. During his time at Dickinson, Conway helped found the college's first student publication and was influenced by Professor John McClintock, which caused him to embrace Methodism as well as an anti-slavery position, although that controversy was starting to split the denomination. In Fredericksburg, uncle Eustace funded the pro-slavery Southern Conference faction and his father the at-least-theoretically anti-slavery Baltimore Conference faction.

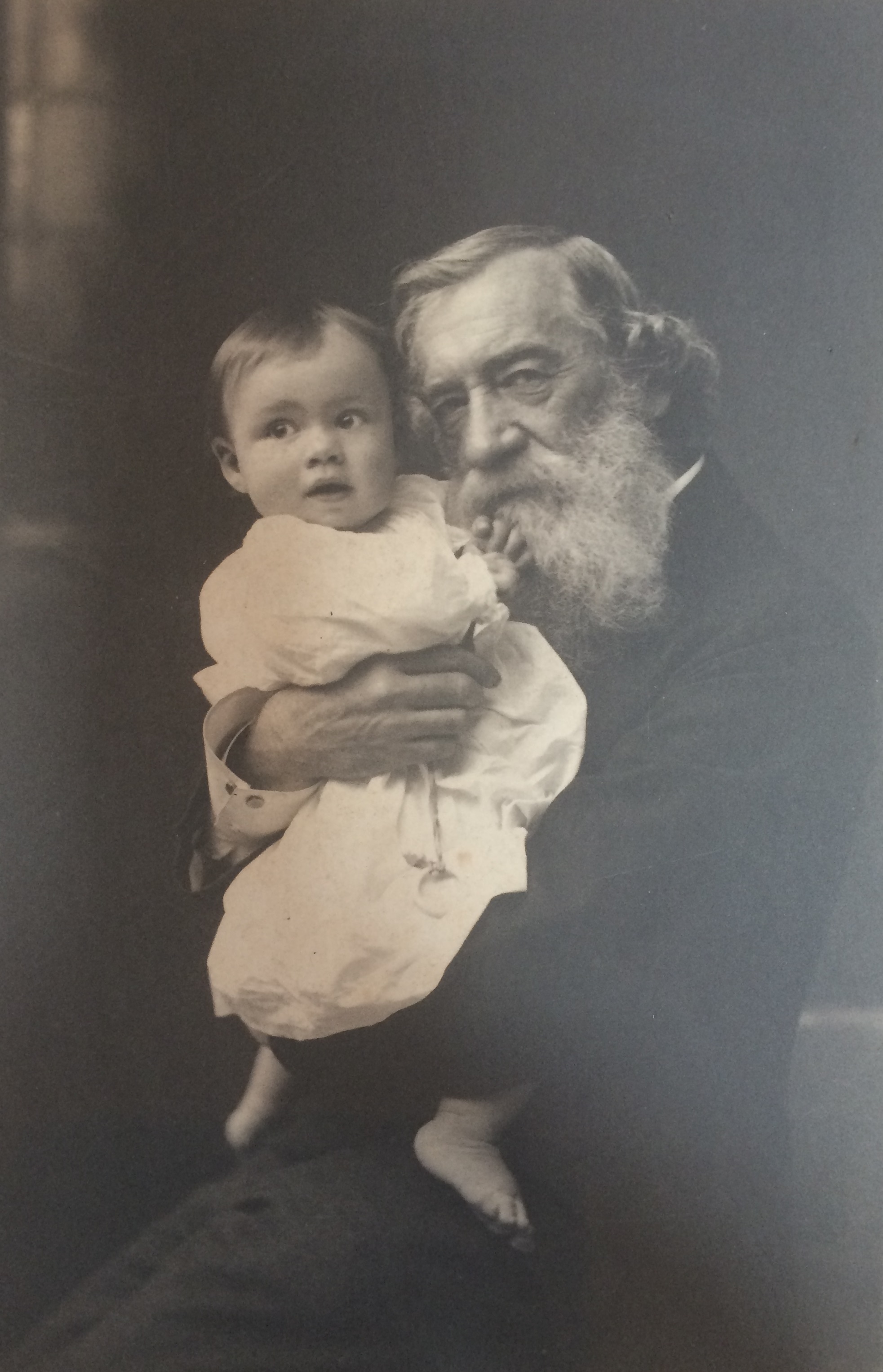

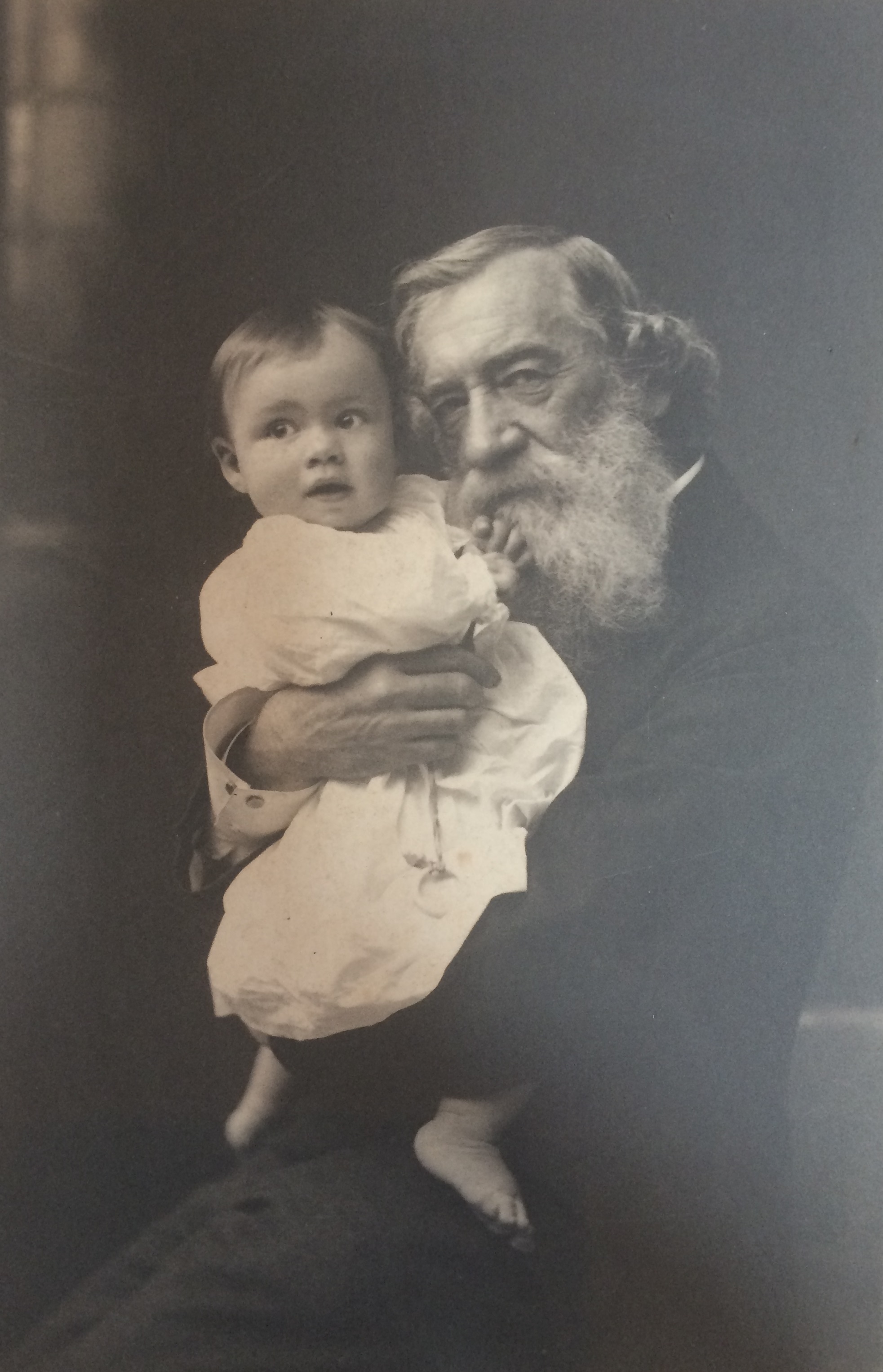

While in Cincinnati

Cincinnati ( ; colloquially nicknamed Cincy) is a city in Hamilton County, Ohio, United States, and its county seat. Settled in 1788, the city is located on the northern side of the confluence of the Licking River (Kentucky), Licking and Ohio Ri ...

as discussed below, Conway married Ellen Davis Dana. She was a fellow Unitarian, feminist

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideology, ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social gender equality, equality of the sexes. Feminism holds the position that modern soci ...

, and abolitionist. The couple had three sons (two of whom survived childhood) and a daughter during their long marriage, which ended with her death from cancer in 1898. Despite the previous tension with his own family over his opposition to slavery, Moncure Conway nevertheless brought his bride to meet them, during which Ellen broke a Southern social constraint by hugging and kissing a young slave girl in front of family members; after this, it would take 17 years before Conway reconciled with his family.

Career

After studying law for a year inWarrenton, Virginia

Warrenton is a town in Fauquier County, Virginia, United States. It is the county seat. The population was 10,057 as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, an increase from 9,611 at the 2010 United States Census, 2010 census and 6,670 at ...

, partly out of a moral crisis caused by seeing a lynching of a Black man whose retrial had been ordered by the Court of Appeals, Conway became a circuit-riding Methodist

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a Protestant Christianity, Christian Christian tradition, tradition whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's brother ...

minister. Conway had self-published his first pamphlet in 1850, "Free Schools in Virginia: A Plea of Education, Virtue and Thrift, vs. Ignorance, Vice and Poverty", but had been unable to convince local politicians to follow his recommendations, particularly as the pro-slavery faction believed such universal education influenced by Northern mores. His Rockville Circuit included his native state and Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

, through Rockville, Maryland

Rockville is a city in and the county seat of Montgomery County, Maryland, United States, and is part of the Washington metropolitan area. The 2020 United States census, 2020 census tabulated Rockville's population at 67,117, making it the fourth ...

, where he became acquainted with the Quaker Roger Brooke, whom he considered his first avowed abolitionist, despite his familial relation to the jurist Roger Brooke Taney. In 1853, after being reassigned to a circuit around Frederick, Maryland

Frederick is a city in, and the county seat of, Frederick County, Maryland, United States. Frederick's population was 78,171 people as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, making it the List of municipalities in Maryland, second-largest ...

, and shortly after his beloved elder brother Peyton died of typhoid fever

Typhoid fever, also known simply as typhoid, is a disease caused by '' Salmonella enterica'' serotype Typhi bacteria, also called ''Salmonella'' Typhi. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often th ...

and his assistant Becky of another, Moncure Conway left the Methodist church and entered the Harvard University

Harvard University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the History of the Puritans in North America, Puritan clergyma ...

school of divinity to continue his spiritual journey. Before graduating in 1854, he met Ralph Waldo Emerson

Ralph Waldo Emerson (May 25, 1803April 27, 1882), who went by his middle name Waldo, was an American essayist, lecturer, philosopher, minister, abolitionism, abolitionist, and poet who led the Transcendentalism, Transcendentalist movement of th ...

and fell under the influence of Transcendentalism

Transcendentalism is a philosophical, spiritual, and literary movement that developed in the late 1820s and 1830s in the New England region of the United States. "Transcendentalism is an American literary, political, and philosophical movement of ...

, as well as became an outspoken abolitionist after discussions with Theodore Parker, William Lloyd Garrison

William Lloyd Garrison (December , 1805 – May 24, 1879) was an Abolitionism in the United States, American abolitionist, journalist, and reformism (historical), social reformer. He is best known for his widely read anti-slavery newspaper ''The ...

, Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Elizabeth Cady Stanton ( Cady; November 12, 1815 – October 26, 1902) was an American writer and activist who was a leader of the women's rights movement in the U.S. during the mid- to late-19th century. She was the main force behind the 1848 ...

and Wendell Phillips.

In America

After graduating from Harvard, Conway accepted a call to the First Unitarian Church ofWashington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

, but he was invited to seek another position after enunciating abolitionist views. Moreover, when Conway returned to his native Virginia, his rumored connection with an attempt to rescue the fugitive slave Anthony Burns in Boston, Massachusetts

Boston is the capital and most populous city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. The city serves as the cultural and Financial centre, financial center of New England, a region of the Northeas ...

(whose master Conway had known in Stafford, Virginia, before their move to Alexandria and was ultimately purchased by an abolitionist and set free) aroused bitter hostility among his old neighbors and friends and family. Conway fled being tarred and feathered in 1854.

Nonetheless, almost at once, Conway was invited to preach sermons at the Unitarian congregation in Cincinnati, Ohio

Cincinnati ( ; colloquially nicknamed Cincy) is a city in Hamilton County, Ohio, United States, and its county seat. Settled in 1788, the city is located on the northern side of the confluence of the Licking River (Kentucky), Licking and Ohio Ri ...

. He served as minister at that anti-slavery congregation from late 1855 until after the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861. However, when in 1859, he announced to the congregation that he no longer believed in miracles or Christ's divinity, a third of the congregation left, but the "Free Church" survived. Conway also edited a short-lived liberal periodical, ''The Dial'', in 1860-1861, linking his emerging spiritual views to his Transcendentalist background. In Cincinnati, he became more acquainted with Jews and Catholics, and counseled against discriminating against them because of their religions. A story he published in ''The Dial'' was grounded in Arthurian legend

The Matter of Britain (; ; ; ) is the body of medieval literature and legendary material associated with Great Britain and Brittany and the legendary kings and heroes associated with it, particularly King Arthur. The 12th-century writer Geoffr ...

, and explained how Arthur's sword Excalibur

Excalibur is the mythical sword of King Arthur that may possess magical powers or be associated with the rightful sovereignty of Britain. Its first reliably datable appearance is found in Geoffrey of Monmouth's ''Historia Regum Britanniae''. E ...

came into George Washington

George Washington (, 1799) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the first president of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797. As commander of the Continental Army, Washington led Patriot (American Revoluti ...

's possession, and then was passed on to John Brown, who used it in his raid on Harpers Ferry.

Civil War

Conway had become editor of the anti-slavery weekly ''Commonwealth'' inBoston

Boston is the capital and most populous city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. The city serves as the cultural and Financial centre, financial center of New England, a region of the Northeas ...

, and in 1861, Conway published semi-anonymously ''The Rejected Stone; or Insurrection vs. Resurrection in America'', identifying himself only as a "Native of Virginia". The book was published in three editions and ultimately handed out to Union soldiers after the start of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

. During the next year, Conway advocated abolition, including in a Smithsonian lecture series in Washington, D.C., which earned him and the more moderate Unitarian minister William Henry Channing

William Henry Channing (May 25, 1810 – December 23, 1884) was an American Unitarian clergyman, writer and philosopher.

Early life

William Henry Channing was born in Boston, Massachusetts. Channing's father, Francis Dana Channing, died when he w ...

a meeting with President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

to discuss his argument that announcing abolition would weaken the Confederacy. While in Washington, DC, Conway located thirty-one of his father's slaves who had fled from Virginia into Georgetown. Conway secured train tickets and safe-conduct passes for them and escorted them on a dangerous trip through Maryland to safety in Yellow Springs, Ohio

Yellow Springs is a Village (Ohio), village in northern Greene County, Ohio, United States. The population was 3,697 at the United States Census, 2020, 2020 census. It is part of the Greater Dayton, Dayton metropolitan area and is home to Antioch ...

, where he believed they would be safe because of the town's accepting culture.

In 1862, during the Union occupation before the devastating Battle of Fredericksburg

The Battle of Fredericksburg was fought December 11–15, 1862, in and around Fredericksburg, Virginia, in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. The combat between the Union Army, Union Army of the Potomac commanded by Major general ( ...

in December of that year, Conway returned home to Falmouth and learned that his family's house had been spared from destruction because of its association with him, although it was commandeered for use as a hospital for wounded soldiers (at which Walt Whitman

Walter Whitman Jr. (; May 31, 1819 – March 26, 1892) was an American poet, essayist, and journalist; he also wrote two novels. He is considered one of the most influential poets in American literature and world literature. Whitman incor ...

would work as a nurse). That year, Conway published another powerful plea for emancipation, ''The Golden Hour'' (1862). On New Year's Day, 1863 (also called Emancipation Day, because President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation

The Emancipation Proclamation, officially Proclamation 95, was a presidential proclamation and executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the American Civil War. The Proclamation had the eff ...

, news of which reached Boston by telegraph), Conway with fellow abolitionists Julia Ward Howe

Julia Ward Howe ( ; May 27, 1819 – October 17, 1910) was an American author and poet, known for writing the "Battle Hymn of the Republic" as new lyrics to an existing song, and the original 1870 pacifist Mothers' Day Proclamation. She w ...

, Amos Bronson Alcott

Amos Bronson Alcott (; November 29, 1799 – March 4, 1888) was an American teacher, writer, philosopher, and reformer. As an educator, Alcott pioneered new ways of interacting with young students, focusing on a conversational style, and av ...

, Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr., George Luther Stearns and Wendell Phillips unveiled a marble bust of John Brown at Stearns' home.

Also in 1862, after spending more and more time away from his church advancing the abolitionist cause, and growing dissatisfied with the theological, liturgical, and social conservatism

Social conservatism is a political philosophy and a variety of conservatism which places emphasis on Tradition#In political and religious discourse, traditional social structures over Cultural pluralism, social pluralism. Social conservatives ...

of mainstream Unitarianism, Conway left that denomination's ministry, and he maintained an uneasy and uncertain relationship with Unitarianism in America and subsequently in England until he and Ellen made a clean break.

London

In April 1863, fellow American abolitionists sent Conway to London to convince theUnited Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

that the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

was primarily a war of abolition and to not support the Confederacy. Under English influence, Conway eventually contacted James Murray Mason, representative of the Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America (CSA), also known as the Confederate States (C.S.), the Confederacy, or Dixieland, was an List of historical unrecognized states and dependencies, unrecognized breakaway republic in the Southern United State ...

to Britain "on behalf of the leading antislavery men of America," offering withdrawal of support for prosecution of the war in exchange for emancipation of the slaves. Mason publicly rejected the overture, embarrassing Conway's sponsors, who quickly and angrily withdrew support. Moreover, Conway had to apologize to US Secretary of State William H. Seward, who could have caused revocation of his passport for attempting to speak as a private citizen for the US government.

Rather than go back to America, where Conway no longer felt welcome as a suspected traitor to his childhood Virginia friends and neighbors and he paid someone to take his place after being drafted to serve in the Union army, Conway traveled to Italy. There, he reunited with his wife and children in

Rather than go back to America, where Conway no longer felt welcome as a suspected traitor to his childhood Virginia friends and neighbors and he paid someone to take his place after being drafted to serve in the Union army, Conway traveled to Italy. There, he reunited with his wife and children in Venice

Venice ( ; ; , formerly ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 islands that are separated by expanses of open water and by canals; portions of the city are li ...

before moving back to London. There, in 1864, he became minister of the South Place Chapel (serving in 1864–65 and 1893–97) as well as leader of the then named South Place Religious Society in Finsbury, London. Conway continued writing and publishing, including articles in both British and American magazines and traveled to Paris and even Russia.Goolrick p. 100 He also served as a war correspondent during the Franco-Prussian War

The Franco-Prussian War or Franco-German War, often referred to in France as the War of 1870, was a conflict between the Second French Empire and the North German Confederation led by the Kingdom of Prussia. Lasting from 19 July 1870 to 28 Janua ...

of 1870–71. Conway published biographies of Edmund Randolph

Edmund Jennings Randolph (August 10, 1753 September 12, 1813) was a Founding Father of the United States, attorney, and the seventh Governor of Virginia. As a delegate from Virginia, he attended the Constitutional Convention and helped to cre ...

, Nathaniel Hawthorne

Nathaniel Hawthorne (né Hathorne; July 4, 1804 – May 19, 1864) was an American novelist and short story writer. His works often focus on history, morality, and religion.

He was born in 1804 in Salem, Massachusetts, from a family long associat ...

and Thomas Paine

Thomas Paine (born Thomas Pain; – In the contemporary record as noted by Conway, Paine's birth date is given as January 29, 1736–37. Common practice was to use a dash or a slash to separate the old-style year from the new-style year. In ...

, as well as acted as the American agent for Robert Browning

Robert Browning (7 May 1812 – 12 December 1889) was an English poet and playwright whose dramatic monologues put him high among the Victorian literature, Victorian poets. He was noted for irony, characterization, dark humour, social commentar ...

and the London literary agent for Walt Whitman

Walter Whitman Jr. (; May 31, 1819 – March 26, 1892) was an American poet, essayist, and journalist; he also wrote two novels. He is considered one of the most influential poets in American literature and world literature. Whitman incor ...

, Mark Twain

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (November 30, 1835 – April 21, 1910), known by the pen name Mark Twain, was an American writer, humorist, and essayist. He was praised as the "greatest humorist the United States has produced," with William Fau ...

, Louisa May Alcott

Louisa May Alcott (; November 29, 1832March 6, 1888) was an American novelist, short story writer, and poet best known for writing the novel ''Little Women'' (1868) and its sequels ''Good Wives'' (1869), ''Little Men'' (1871), and ''Jo's Boys'' ...

, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Elizabeth Cady Stanton ( Cady; November 12, 1815 – October 26, 1902) was an American writer and activist who was a leader of the women's rights movement in the U.S. during the mid- to late-19th century. She was the main force behind the 1848 ...

.

Conway also abandoned theism

Theism is broadly defined as the belief in the existence of at least one deity. In common parlance, or when contrasted with '' deism'', the term often describes the philosophical conception of God that is found in classical theism—or the co ...

after his son Emerson died in 1864. His thinking continued to move from Emersonian transcendentalism

Transcendentalism is a philosophical, spiritual, and literary movement that developed in the late 1820s and 1830s in the New England region of the United States. "Transcendentalism is an American literary, political, and philosophical movement of ...

toward a more humanistic

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential, and agency of human beings, whom it considers the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "humanism" ha ...

Freethought

Freethought (sometimes spelled free thought) is an unorthodox attitude or belief.

A freethinker holds that beliefs should not be formed on the basis of authority, tradition, revelation, or dogma, and should instead be reached by other meth ...

. He conducted funeral services for his friend Artemus Ward

Charles Farrar Browne (April 26, 1834 – March 6, 1867) was an American humor writer, better known under his ''pen name, nom de plume'', Artemus Ward, which as a character, an illiterate rube with "Yankee common sense", Browne also played in pu ...

and preached memorial at memorial services for many other famous literary figures. Moreover, women were allowed to preach at South Place Chapel, among them Annie Besant

Annie Besant (; Wood; 1 October 1847 – 20 September 1933) was an English socialist, Theosophy (Blavatskian), theosophist, freemason, women's rights and Home Rule activist, educationist and campaigner for Indian nationalism. She was an arden ...

, whom Mrs. Conway had befriended. However, the South Place congregation and Conway soon left fellowship with the Unitarian Church. For a year from November 1865 Cleveland Hall was leased for Sunday evenings so Conway could "address the working classes." However, the audience consisted of well-dressed lower-middle-class people.

Conway remained the leader of South Place until 1886, when Stanton Coit took his place. Under Coit's leadership, South Place was renamed to the South Place Ethical Society

The Conway Hall Ethical Society, formerly the South Place Ethical Society, based in London at Conway Hall, is thought to be the oldest surviving freethought organisation in the world and is the only remaining ethical society in the United King ...

. However Coit's tenure ended in 1892 in a losing power struggle, and Conway resumed leadership until his death.

Conway attended the salon

Salon may refer to:

Common meanings

* Beauty salon

A beauty salon or beauty parlor is an establishment that provides Cosmetics, cosmetic treatments for people. Other variations of this type of business include hair salons, spas, day spas, ...

of radicals Peter

Peter may refer to:

People

* List of people named Peter, a list of people and fictional characters with the given name

* Peter (given name)

** Saint Peter (died 60s), apostle of Jesus, leader of the early Christian Church

* Peter (surname), a su ...

and Clementia Taylor at Aubrey House in Campden Hill

Campden Hill is a hill in Kensington, West London, bounded by Holland Park Avenue on the north, Kensington High Street on the south, Kensington Palace Gardens on the east and Abbotsbury Road on the west. The name derives from the former ''Camp ...

, West London. He also was a member of Clementia's "Pen and Pencil Club", at which young writers and artists read and exhibited their works. Conway moved to Notting Hill to be near the Taylors at Aubrey House.

In 1868, Conway was one of four speakers at the first open public meeting in support of women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the women's rights, right of women to Suffrage, vote in elections. Several instances occurred in recent centuries where women were selectively given, then stripped of, the right to vote. In Sweden, conditional women's suffra ...

in Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-west coast of continental Europe, consisting of the countries England, Scotland, and Wales. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the List of European ...

. His many literary and intellectual friends included Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English novelist, journalist, short story writer and Social criticism, social critic. He created some of literature's best-known fictional characters, and is regarded by ...

, Robert Browning

Robert Browning (7 May 1812 – 12 December 1889) was an English poet and playwright whose dramatic monologues put him high among the Victorian literature, Victorian poets. He was noted for irony, characterization, dark humour, social commentar ...

, Thomas Carlyle

Thomas Carlyle (4 December 17955 February 1881) was a Scottish essayist, historian, and philosopher. Known as the "Sage writing, sage of Chelsea, London, Chelsea", his writings strongly influenced the intellectual and artistic culture of the V ...

, Charles Lyell

Sir Charles Lyell, 1st Baronet, (14 November 1797 – 22 February 1875) was a Scottish geologist who demonstrated the power of known natural causes in explaining the earth's history. He is best known today for his association with Charles ...

, and Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

. In 1878, he attempted to personally endow a new, non-denominational women's college at the University of Oxford

The University of Oxford is a collegiate university, collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the List of oldest un ...

; frightened at this prospect, Anglicans made haste to instead create Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford

Lady Margaret Hall (LMH) is a Colleges of the University of Oxford, constituent college of the University of Oxford in England, located on a bank of the River Cherwell at Norham Gardens in north Oxford and adjacent to the University Parks. The ...

, which was the first women's college at Oxford.

In the 1870s and the 1880s, Conway returned occasionally to the United States, where he reconciled with his Virginia family in 1875 and toured in the West about Demonology and the famous Englishmen he knew. In 1897 Conway and his terminally-ill (from cancer) wife Ellen returned from London to New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

to fulfill her wish of dying on American soil; she died on Christmas Day; their son Dana also died that year. As the Spanish–American War

The Spanish–American War (April 21 – August 13, 1898) was fought between Restoration (Spain), Spain and the United States in 1898. It began with the sinking of the USS Maine (1889), USS ''Maine'' in Havana Harbor in Cuba, and resulted in the ...

approached, Conway turned toward pacifism and became disaffected with his countrymen, moving to France to devote much of the rest of his life to the peace movement and writing. However, he occasionally returned to Fredericksburg, which had come to admire his cultural accomplishments. Conway also traveled to India and wrote about it shortly before his death.

India

Conway visitedIndia

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

and described his experiences in ''My Pilgrimage to the Wise Men of the East'', 1906.

He visited Helena Blavatsky

Helena Petrovna Blavatsky (; – 8 May 1891), often known as Madame Blavatsky, was a Russian-born Mysticism, mystic and writer who emigrated to the United States where she co-founded the Theosophical Society in 1875. She gained an internat ...

in 1884 and denounced the Mahatma letters as fraudulent. He suggested that Koot Hoomi was a fictitious creation of Blavatsky. Conway wrote that Blavatsky "created the imaginary Koothoomi (originally Kothume) by piecing together parts of the names of her two chief disciples, Olcott and Hume." Versluis, Arthur. (1993). ''American Transcendentalism and Asian Religions''. Oxford University Press. p. 291.

Death

Conway died alone, at 75, in his apartment inParis

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

. His corpse was found on November 15, 1907, and was ultimately returned to Westchester County, New York

Westchester County is a County (United States), county located in the southeastern portion of the U.S. state of New York (state), New York, bordering the Long Island Sound and the Byram River to its east and the Hudson River on its west. The c ...

, for burial in Kensico cemetery.

Legacy

Conway Hall

Conway Hall in Red Lion Square, London, is the headquarters of the Conway Hall Ethical Society. It is a Grade II listed building.

History

The building was commissioned by the South Place Ethical Society, which had previously been accommodated ...

in Holborn, London is named in his honor. In 2004, Virginia Governor Mark R. Warner proclaimed Conway the only descendant of a Founding Father of the nation to physically lead slaves to freedom. Both Ohio and Virginia have erected historical markers in his honor, and Conway's childhood home was designated a U.S. and Virginia landmark.

Works

*''Tracts for To-day'' (1858online edition

*''The Natural History of the Devil'' (1859) *''The Rejected Stone: or, Insurrection vs. Resurrection in America, By a Native of Virginia'' (1861

online edition

*''The Golden Hour'' (1862

online edition

*''Testimonies Concerning Slavery'' (1864

online edition

*''The Earthward Pilgrimage'' (1870

online edition

*''Republican Superstitions as Illustrated in the Political History of America'' (1872

online edition

*''Christianity'' (1876

online edition

*''Idols and Ideals, with an Essay on Christianity'' (1877

online edition

*''Demonology and Devil Lore'' (2 vols., 1878

*''A Necklace of Stories'' (1880

online edition

*''Thomas Carlyle'' (1881

online edition

*''The Wandering Jew'' (1881

online edition

*''Emerson at Home and Abroad'' (1882

online edition

*''Travels in South Kensington: with Notes on Decorative Art and Rrchitecture in England'' (1882

online edition

*''Lessons for the Day'' (1882

online edition

*''The Saint Patrick Myth (1883)'' *''Pine and Palm: A Novel'' (2 vols., 1887

online edition

*''Life and Papers of Edmund Randolph'' (1888

online edition

*''Life of Nathaniel Hawthorne'' (1890

online edition

*''George Washington's Rules of Civility: Traced to their Sources and Restored'' (1890

online edition

*''The Life of Thomas Paine'' with an unpublished sketch of Paine by

William Cobbett

William Cobbett (9 March 1763 – 18 June 1835) was an English pamphleteer, journalist, politician, and farmer born in Farnham, Surrey. He was one of an Agrarianism, agrarian faction seeking to reform Parliament, abolish "rotten boroughs", restr ...

(2 vols., 1892online edition

*''The Writings of Thomas Paine'' (1894

online edition

*''Solomon and Solomonic Literature'' (1899

online edition

*''Autobiography, Memories and Experiences'' (2 vols., 1904

online edition

*''My Pilgrimage to the Wise Men of the East'' (1906

online edition

See also

*American philosophy

American philosophy is the activity, corpus, and tradition of philosophers affiliated with the United States. The ''Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' notes that while it lacks a "core of defining features, American Philosophy can neverthe ...

* List of American philosophers

American philosophy is the activity, corpus, and tradition of philosophers affiliated with the United States. The ''Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' notes that while it lacks a "core of defining features, American Philosophy can neverthe ...

References

Sources

*Dictionary of Unitarian & Universalist Biography

- Article by Charles A. Howe *Burtis, Mary Elizabeth. ''Moncure Conway, 1832-1907.'' New Brunswick, Rutgers University Press, 1952. *d'Entremont, John. ''Southern Emancipator: Moncure Conway: The American Years, 1832-1865.'' Oxford University Press, 1987. *Easton, Loyd D. ''Hegel's First American Followers: The Ohio Hegelians: J.D. Stallo, Peter Kaufmann, Moncure Conway, August Willich.'' Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 1966. *Good, James A., ed. ''Moncure Daniel Conway: Autobiography and Miscellaneous Writings.'' 3 volumes. Bristol, UK: Thoemmes Press, 2003. *Good, James A., ed. ''The Ohio Hegelians.'' 3 volumes. Bristol, UK: Thoemmes Press, 2004. *Walker, Peter. ''Moral Choices: Memory, Desire, and Imagination in Nineteenth-Century American Abolition.'' Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1978. *

External links

Moncure Conway Foundation

Moncure Conway in ''Encyclopedia Virginia''

* * *

''Wandering Jew and Wandering Jeweess''

screenplays {{DEFAULTSORT:Conway, Moncure Daniel 1832 births 1907 deaths 19th-century American philosophers American abolitionists American Methodist clergy American Unitarian clergy Critics of Theosophy Dickinson College alumni Ethical movement Freethought writers Harvard Divinity School alumni Hegelian philosophers Moncure family People associated with Conway Hall Ethical Society People from Falmouth, Virginia Burials at Kensico Cemetery Members of the American Academy of Arts and Letters