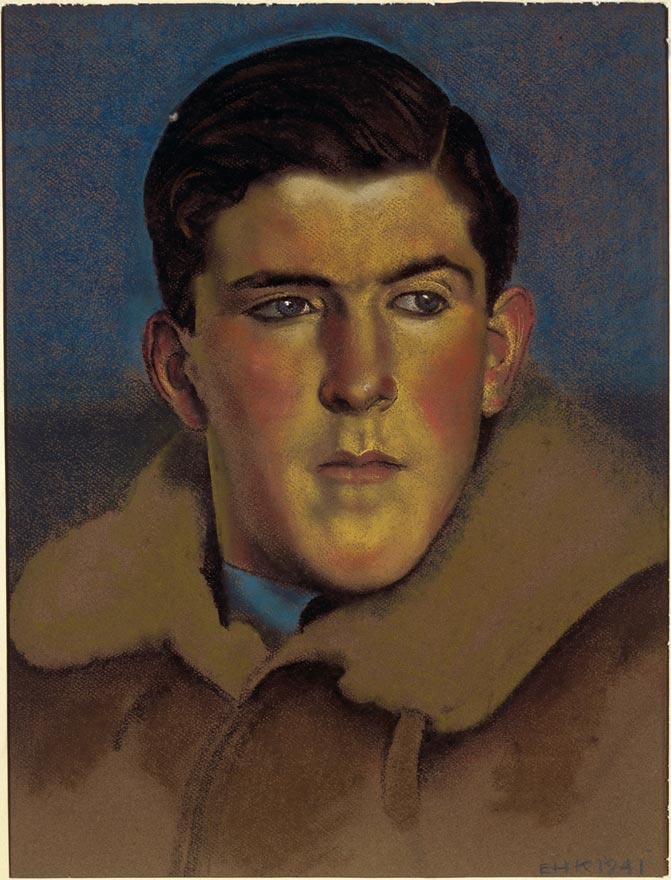

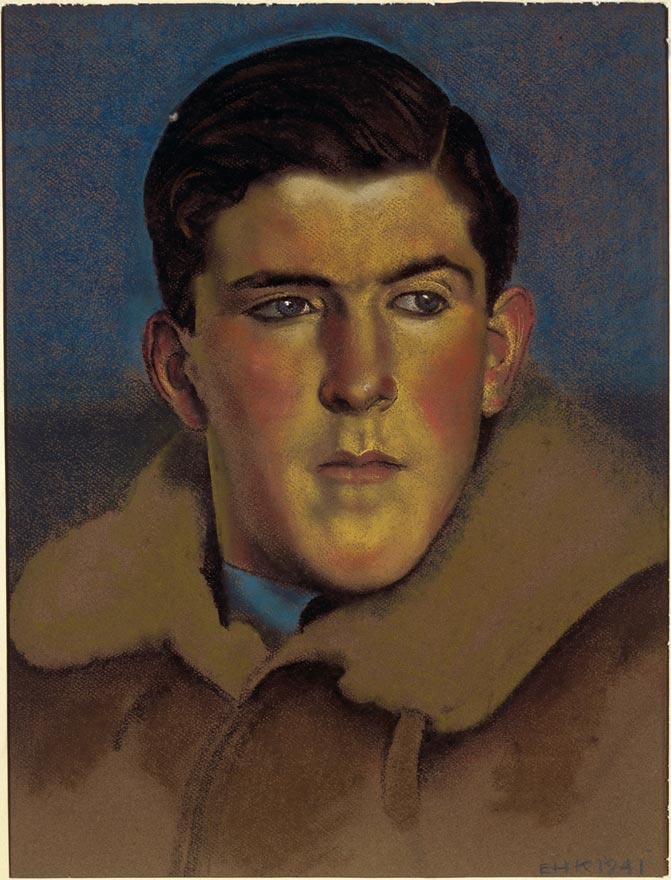

Michael Herrick on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Michael James Herrick, (5 May 1921 – 16 June 1944) was a New Zealand

Although No. 25 Squadron's aircraft had been intended for light bombing, in June it was moved to

Although No. 25 Squadron's aircraft had been intended for light bombing, in June it was moved to

At the time he joined the squadron, it operated

At the time he joined the squadron, it operated

flying ace

A flying ace, fighter ace or air ace is a military aviation, military aviator credited with shooting down a certain minimum number of enemy aircraft during aerial combat; the exact number of aerial victories required to officially qualify as an ...

of the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the Air force, air and space force of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies. It was formed towards the end of the World War I, First World War on 1 April 1918, on the merger of t ...

(RAF) during the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. He is credited with having shot down at least six enemy aircraft.

Born in Hastings

Hastings ( ) is a seaside town and Borough status in the United Kingdom, borough in East Sussex on the south coast of England,

east of Lewes and south east of London. The town gives its name to the Battle of Hastings, which took place to th ...

, Herrick joined the RAF in 1939. During the Battle of Britain

The Battle of Britain () was a military campaign of the Second World War, in which the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) of the Royal Navy defended the United Kingdom (UK) against large-scale attacks by Nazi Germany's air force ...

he flew Bristol Blenheim

The Bristol Blenheim is a British light bomber designed and built by the Bristol Aeroplane Company, which was used extensively in the first two years of the Second World War, with examples still being used as trainers until the end of the war. ...

s on night operations with No. 25 Squadron, destroying three German bombers. He was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) for his actions during the battle. In late 1941, Herrick was sent to New Zealand on secondment

Secondment is the temporary assignment of a member of one organization to another organization. In some jurisdictions, .g., Indiasuch temporary transfer of employees is called "on deputation".

Job rotation

The employee typically retains their s ...

to the Royal New Zealand Air Force

The Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF; ) is the aerial warfare, aerial military service, service branch of the New Zealand Defence Force. It was formed initially in 1923 as a branch of the New Zealand Army, being known as the New Zealand Perm ...

to take command of its new No. 15 Squadron. With the squadron he flew two operational tours in the Pacific, including several missions around Guadalcanal

Guadalcanal (; indigenous name: ''Isatabu'') is the principal island in Guadalcanal Province of Solomon Islands, located in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, northeast of Australia. It is the largest island in the Solomons by area and the second- ...

, and destroyed a number of Japanese aircraft. In 1944, having been awarded a bar

Bar or BAR may refer to:

Food and drink

* Bar (establishment), selling alcoholic beverages

* Candy bar

** Chocolate bar

* Protein bar

Science and technology

* Bar (river morphology), a deposit of sediment

* Bar (tropical cyclone), a laye ...

to his DFC, he returned to England to resume service with the RAF and was posted to No. 305 Polish Bomber Squadron, which operated the de Havilland Mosquito

The de Havilland DH.98 Mosquito is a British twin-engined, multirole combat aircraft, introduced during the World War II, Second World War. Unusual in that its airframe was constructed mostly of wood, it was nicknamed the "Wooden Wonder", or " ...

fighter-bomber, as one of its flight commander

A flight commander is the leader of a constituent portion of an aerial squadron in aerial operations, often into combat. That constituent portion is known as a flight, and usually contains six or fewer aircraft, with three or four being a common ...

s. Herrick was killed during a daylight raid on a German airfield at Aalborg

Aalborg or Ålborg ( , , ) is Denmark's List of cities and towns in Denmark, fourth largest urban settlement (behind Copenhagen, Aarhus, and Odense) with a population of 119,862 (1 July 2022) in the town proper and an Urban area, urban populati ...

in Denmark. In recognition of his services in the Pacific, he was posthumously awarded the United States Air Medal

The Air Medal (AM) is a military decoration of the United States Armed Forces. It was created in 1942 and is awarded for single acts of heroism or meritorious achievement while participating in aerial flight.

Criteria

The Air Medal was establi ...

.

Early life

Michael James Herrick was born inHastings, New Zealand

Hastings (; , ) is an inland city of New Zealand and is one of the two major urban areas of New Zealand, urban areas in Hawke's Bay Region, Hawke's Bay, on the east coast of the North Island. The population of Hastings (including Flaxmere) is ...

, on 5 May 1921, one of five sons of Edward Herrick and his wife, Ethne Rose Smith. He was first educated at Hurworth School in Wanganui

Whanganui, also spelt Wanganui, is a list of cities in New Zealand, city in the Manawatū-Whanganui region of New Zealand. The city is located on the west coast of the North Island at the mouth of the Whanganui River, New Zealand's longest nav ...

before going onto Wanganui Collegiate School

Whanganui Collegiate School is a state-integrated, coeducational, day and boarding secondary school located in Whanganui, in the Manawatū-Whanganui region of New Zealand. Affiliated with the Anglican Church, it is the third oldest school in ...

. While still at school, he took flying lessons and soon earned his pilot's licence

Pilot licensing or certification refers to permits for operating aircraft. Flight crew licences are issued by the civil aviation authority of each country, which must establish that the holder has met minimum knowledge and experience before issui ...

from the Hawke's Bay and East Coast Aero Club. In 1938, he gained a cadetship for the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the Air force, air and space force of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies. It was formed towards the end of the World War I, First World War on 1 April 1918, on the merger of t ...

(RAF). This involved attending its college at Cranwell, and he travelled to England on RMS ''Rangitiki'' the following year to commence his training.

Second World War

The outbreak of the Second World War forced Herrick's cadetship, originally scheduled to run for two years, to be consolidated by the RAF. He was commissioned as apilot officer

Pilot officer (Plt Off or P/O) is a junior officer rank used by some air forces, with origins from the Royal Air Force. The rank is used by air forces of many countries that have historical British influence.

Pilot officer is the lowest ran ...

on 7 March 1940 and was posted to No. 25 Squadron, which was stationed at North Weald

North Weald Bassett, or simply North Weald ( ), is a village and civil parish in the Epping Forest district of Essex, England. The village is within the North Weald Ridges and Valleys landscape area.

A market is held every Saturday and Bank Ho ...

and operated Bristol Blenheim

The Bristol Blenheim is a British light bomber designed and built by the Bristol Aeroplane Company, which was used extensively in the first two years of the Second World War, with examples still being used as trainers until the end of the war. ...

s. At the time he joined the squadron, it was involved in patrols over the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Denmark, Norway, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France. A sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian Se ...

, providing protection for convoys transiting the British coast. During Operation Dynamo

Operation or Operations may refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media

* ''Operation'' (game), a battery-operated board game that challenges dexterity

* Operation (music), a term used in musical set theory

* ''Operations'' (magazine), Multi-Man ...

, it helped escort the evacuation fleet to and from Dunkirk

Dunkirk ( ; ; ; Picard language, Picard: ''Dunkèke''; ; or ) is a major port city in the Departments of France, department of Nord (French department), Nord in northern France. It lies from the Belgium, Belgian border. It has the third-larg ...

and carried out patrols along the Dutch and Belgian coast.

Battle of Britain

Although No. 25 Squadron's aircraft had been intended for light bombing, in June it was moved to

Although No. 25 Squadron's aircraft had been intended for light bombing, in June it was moved to Martlesham Heath

Martlesham Heath is a village in Suffolk, England. It is east of Ipswich, This was an ancient area of heathland and latterly the site of Martlesham Heath Airfield. A "new village" was established there in the mid-1970s and this has developed in ...

to operate in a night fighting role. The Blenheims were equipped with airborne radar

Radar is a system that uses radio waves to determine the distance ('' ranging''), direction ( azimuth and elevation angles), and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It is a radiodetermination method used to detect and track ...

, which Herrick helped to test. The squadron's switch in role coincided with an increase in the ''Luftwaffe

The Luftwaffe () was the aerial warfare, aerial-warfare branch of the before and during World War II. German Empire, Germany's military air arms during World War I, the of the Imperial German Army, Imperial Army and the of the Imperial Ge ...

s nightly bombing raids on London. On the night of 4/5 September 1940, despite his aircraft's radar set malfunctioning, Herrick spotted a Heinkel He 111

The Heinkel He 111 is a German airliner and medium bomber designed by Siegfried and Walter Günter at Heinkel Flugzeugwerke in 1934. Through development, it was described as a wolf in sheep's clothing. Due to restrictions placed on Germany a ...

bomber caught in some of Anti-Aircraft Command

Anti-Aircraft Command (AA Command, or "Ack-Ack Command") was a British Army command of the Second World War that controlled the Territorial Army anti-aircraft artillery and searchlight formations and units defending the United Kingdom.

Origin

...

's searchlight

A searchlight (or spotlight) is an apparatus that combines an extremely luminosity, bright source (traditionally a carbon arc lamp) with a mirrored parabolic reflector to project a powerful beam of light of approximately parallel rays in a part ...

s and shot it down. Within minutes he located and destroyed another bomber, a Dornier Do 17

The Dornier Do 17 is a twin-engined light bomber designed and produced by the German aircraft manufacturer Dornier Flugzeugwerke. Large numbers were operated by the ''Luftwaffe'' throughout the Second World War.

The Do 17 was designed during ...

, exhausting his ammunition in doing so. These destroyed aircraft were the first aerial victories of the war to be credited to one of the squadron's pilots. In recognition of his successes, he was later awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC). The published citation read:

On the night of 13/14 September, while flying a patrol north of London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

, he was directed by his radar to a He 111. Climbing up behind the bomber he opened fire, prompting its crew to jettison its bombload. He continued his attack and the German aircraft went down out of control and exploded, but not before its rear gunner caused minor damage to Herrick's aircraft. He had accounted for three of the four German aircraft destroyed by Fighter Command

RAF Fighter Command was one of the commands of the Royal Air Force. It was formed in 1936 to allow more specialised control of fighter aircraft. It operated throughout the Second World War, winning fame during the Battle of Britain in 1940. The ...

on night operations during September. No. 25 Squadron soon began converting to Bristol Beaufighter

The Bristol Type 156 Beaufighter (often called the Beau) is a British multi-role aircraft developed during the Second World War by the Bristol Aeroplane Company. It was originally conceived as a heavy fighter variant of the Bristol Beaufor ...

s, and in one of these aircraft, operating from Wittering, Herrick possibly destroyed a bomber in December.

In March 1941 Herrick was promoted to flying officer

Flying officer (Fg Offr or F/O) is a junior officer rank used by some air forces, with origins from the Royal Air Force. The rank is used by air forces of many countries that have historical British influence.

Flying officer is immediately ...

and two months later was credited with damaging a Junkers Ju 88

The Junkers Ju 88 is a twin-engined multirole combat aircraft designed and produced by the German aircraft manufacturer Junkers Aircraft and Motor Works. It was used extensively during the Second World War by the ''Luftwaffe'' and became one o ...

bomber near Hull

Hull may refer to:

Structures

* The hull of an armored fighting vehicle, housing the chassis

* Fuselage, of an aircraft

* Hull (botany), the outer covering of seeds

* Hull (watercraft), the body or frame of a sea-going craft

* Submarine hull

Ma ...

. He destroyed a Ju 88 on 22 June while on patrol over the Midlands

The Midlands is the central region of England, to the south of Northern England, to the north of southern England, to the east of Wales, and to the west of the North Sea. The Midlands comprises the ceremonial counties of Derbyshire, Herefor ...

. He was guided in its general direction by ground control and then picked it up on his onboard radar. Spotting the German bomber below him, he opened fire with his guns, setting the Ju 88 ablaze. It dived into the ground and exploded.

Secondment

In October 1941, Herrick was seconded to theRoyal New Zealand Air Force

The Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF; ) is the aerial warfare, aerial military service, service branch of the New Zealand Defence Force. It was formed initially in 1923 as a branch of the New Zealand Army, being known as the New Zealand Perm ...

(RNZAF) and by the end of the year was back in the country of his birth. He spent a period of time as an instructor at the No. 2 Flying Training School

No.2 Flying Training School is a Flying Training School (FTS) of the Royal Air Force (RAF). It is part of No. 22 (Training) Group that delivers glider flying training to the Royal Air Force Air Cadets. Its headquarters is located at RAF Syers ...

at Woodbourne and then Ohakea

RNZAF Base Ohakea is an operational base of the Royal New Zealand Air Force. Opened in 1939, it is located near Bulls, New Zealand, Bulls, 25 km north-west of Palmerston North in the Manawatū District, Manawatū. It is also used as an alter ...

. Promoted to flight lieutenant in March 1942, he was posted to the RNZAF's No. 15 Squadron three months later. The squadron had just been formed and, based at Whenuapai

Whenuapai is a suburb and aerodrome located in northwestern Auckland, in the North Island of New Zealand. It is located on the shore of the Upper Waitematā Harbour, 15 kilometres to the northwest of Auckland's city centre. It is one of the l ...

, was training with P-40 Kittyhawks. After a few months it was sent to Tonga

Tonga, officially the Kingdom of Tonga, is an island country in Polynesia, part of Oceania. The country has 171 islands, of which 45 are inhabited. Its total surface area is about , scattered over in the southern Pacific Ocean. accordin ...

and began operating P-40s that had been recently used by the United States Army Air Force

The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF or AAF) was the major land-based aerial warfare service component of the United States Army and ''de facto'' aerial warfare service branch of the United States during and immediately after World War II ...

's No. 68 Pursuit Squadron, with responsibility for the air defence of the island. In February 1943, the squadron moved to Espiritu Santo

Espiritu Santo (, ; ) is the largest island in the nation of Vanuatu, with an area of and a population of around 40,000 according to the 2009 census.

Geography

The island belongs to the archipelago of the New Hebrides in the Pacific region ...

, the main island of Vanuatu

Vanuatu ( or ; ), officially the Republic of Vanuatu (; ), is an island country in Melanesia located in the South Pacific Ocean. The archipelago, which is of volcanic origin, is east of northern Australia, northeast of New Caledonia, east o ...

, assuming a similar defence role there for a few weeks before, in April, being dispatched to Guadalcanal

Guadalcanal (; indigenous name: ''Isatabu'') is the principal island in Guadalcanal Province of Solomon Islands, located in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, northeast of Australia. It is the largest island in the Solomons by area and the second- ...

in the Solomon Islands

Solomon Islands, also known simply as the Solomons,John Prados, ''Islands of Destiny'', Dutton Caliber, 2012, p,20 and passim is an island country consisting of six major islands and over 1000 smaller islands in Melanesia, part of Oceania, t ...

. Its role there was to carry out local patrols, fly as escorts for bombers, and provide cover for American shipping convoys. By this time Herrick had been promoted squadron leader

Squadron leader (Sqn Ldr or S/L) is a senior officer rank used by some air forces, with origins from the Royal Air Force. The rank is used by air forces of many countries that have historical British influence.

Squadron leader is immediatel ...

and was in charge of the unit; the original commanding officer had been killed in a flying accident.

The squadron's initial encounter with the Japanese took place while escorting a Lockheed Hudson

The Lockheed Hudson is a light bomber and coastal reconnaissance aircraft built by the American Lockheed Aircraft Corporation. It was initially put into service by the Royal Air Force shortly before the outbreak of the Second World War and ...

on 6 May, when Herrick and his wingman shared in the destruction of a Nakajima A6M2-N "Rufe" floatplane

A floatplane is a type of seaplane with one or more slender floats mounted under the fuselage to provide buoyancy. By contrast, a flying boat uses its fuselage for buoyancy. Either type of seaplane may also have landing gear suitable for land, ...

. This is acknowledged to be the first Japanese aircraft shot down in the Pacific by fighters of the RNZAF. A few days later he took part in an escort mission, leading a flight

Flight or flying is the motion (physics), motion of an Physical object, object through an atmosphere, or through the vacuum of Outer space, space, without contacting any planetary surface. This can be achieved by generating aerodynamic lift ass ...

of eight P-40s accompanying a force of Douglas SBD Dauntless

The Douglas SBD Dauntless is a World War II American naval scout plane and dive bomber that was manufactured by Douglas Aircraft from 1940 through 1944. The SBD ("Scout Bomber Douglas") was the United States Navy's main Carrier-based aircraft, ...

light bombers. The P-40s made an initial strafing attack on a Japanese destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, maneuverable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy, or carrier battle group and defend them against a wide range of general threats. They were conceived i ...

and, leaving it to the SBDs to finish off, then attacked landing craft

Landing craft are small and medium seagoing watercraft, such as boats and barges, used to convey a landing force (infantry and vehicles) from the sea to the shore during an amphibious assault. The term excludes landing ships, which are larger. ...

disembarking soldiers onto a nearby island. On 7 June, he was involved in a large dogfight that took place when a force of over 100 Allied fighters, including twelve P-40s from No. 15 Squadron, encountered around 50 Japanese Mitsubishi A6M Zero

The Mitsubishi A6M "Zero" is a long-range carrier-capable fighter aircraft formerly manufactured by Mitsubishi Aircraft Company, a part of Mitsubishi Heavy Industries. It was operated by the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) from 1940 to 1945. The ...

es near the Russell Islands

:''See also Russell Island (disambiguation).''

The Russell Islands are two small islands ( Pavuvu and Mbanika), as well as several islets, of volcanic origin, in the Central Province of Solomon Islands. They are located approximately northwe ...

. On this occasion, Herrick shot down a Zero.

In late June, No. 15 Squadron completed its first operational tour and returned to New Zealand for a rest. It was back in Guadalcanal to commence its second tour in September, again flying as escorts for bombing missions and covering convoys. On 1 October, Herrick shared in the destruction of an Aichi D3A "Val" dive bomber that was attacking a convoy transporting troops of the 3rd New Zealand Division

The 3rd New Zealand Division was a Division (military unit), division of the New Zealand Military Forces. Formed in 1942, it saw action against the Japanese in the Pacific Ocean Areas during the Second World War. The division saw action in the Sol ...

to Vella Lavella

Vella Lavella is an island in the Western Province (Solomon Islands), Western Province of Solomon Islands. It lies to the west of New Georgia, but is considered one of the New Georgia Islands, New Georgia Group. To its west are the Treasury Isla ...

. Herrick's kill was one of seven Japanese aircraft shot down by the squadron that day. He also damaged a second Val. In late October, No. 15 Squadron moved to Ondonga in New Georgia

New Georgia, with an area of , is the largest of the islands in Western Province (Solomon Islands), Western Province, Solomon Islands, and the List of islands by area, 203rd-largest island in the world. Since July 1978, the island has been par ...

; it was to support operations against the Treasury Islands

Treasury Islands () are a small group of islands a few kilometres to the south of Bougainville and from the Shortland Islands. They form part of the Western Province of the country of Solomon Islands. The two largest islands in the Treasurie ...

and Bougainville.

On 27 October, during the landings at the Treasury Islands by New Zealand infantry and supporting troops, the squadron flew covering missions throughout the day. In doing so, they intercepted a force of around 80 Japanese aircraft attempting to attack barges landing supplies and shot down four fighters, with Herrick accounting for one of them, a Zero. The squadron also flew missions protecting the beachhead on Bougainville throughout November. The following month and with his secondment to the RNZAF nearing its end, Herrick relinquished command of the squadron and left to return to New Zealand. He was subsequently awarded a bar

Bar or BAR may refer to:

Food and drink

* Bar (establishment), selling alcoholic beverages

* Candy bar

** Chocolate bar

* Protein bar

Science and technology

* Bar (river morphology), a deposit of sediment

* Bar (tropical cyclone), a laye ...

to his DFC; this was announced in the ''London Gazette'' on 22 February 1944. The citation noted that it was for "gallantry displayed in flying operations against the enemy in the Solomon Islands".

Return to the RAF

In January 1944, Herrick, returning to service with the RAF, embarked for England, via Canada, travelling on a troopship while in charge of 300 RNZAF personnel who were proceeding toEdmonton

Edmonton is the capital city of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Alberta. It is situated on the North Saskatchewan River and is the centre of the Edmonton Metropolitan Region, which is surrounded by Central Alberta ...

for flight training. Once in England, Herrick was posted to No. 305 Polish Bomber Squadron, based at Lasham

Lasham is a village and civil parish in the East Hampshire district of Hampshire, England. It is northwest of Alton, Hampshire, Alton and north of Bentworth, just off the A339 road. The parish covers an area of and has an average elevation o ...

, where he took command of one of its flights.

At the time he joined the squadron, it operated

At the time he joined the squadron, it operated de Havilland Mosquito

The de Havilland DH.98 Mosquito is a British twin-engined, multirole combat aircraft, introduced during the World War II, Second World War. Unusual in that its airframe was constructed mostly of wood, it was nicknamed the "Wooden Wonder", or " ...

fighter-bombers on nighttime missions to mainland Europe, targeting enemy airfields and launching sites for V-1 rockets, but by the middle of the year it was also flying daytime operations. On 16 June 1944, Herrick and his Polish navigator flew a mission during the day to German-occupied Denmark, targeting a ''Luftwaffe'' airfield at Aalborg

Aalborg or Ålborg ( , , ) is Denmark's List of cities and towns in Denmark, fourth largest urban settlement (behind Copenhagen, Aarhus, and Odense) with a population of 119,862 (1 July 2022) in the town proper and an Urban area, urban populati ...

. They were accompanied by Wing Commander

Wing commander (Wg Cdr or W/C) is a senior officer rank used by some air forces, with origins from the Royal Air Force. The rank is used by air forces of many countries that have historical British influence.

Wing commander is immediately se ...

John Braham in his own Mosquito, flying as a pair until Braham separated to proceed to his objective. As Herrick approached the Jutland

Jutland (; , ''Jyske Halvø'' or ''Cimbriske Halvø''; , ''Kimbrische Halbinsel'' or ''Jütische Halbinsel'') is a peninsula of Northern Europe that forms the continental portion of Denmark and part of northern Germany (Schleswig-Holstein). It ...

coast, his Mosquito was attacked by a Focke-Wulf Fw 190

The Focke-Wulf Fw 190, nicknamed ''Würger'' (Shrike) is a German single-seat, single-engine fighter aircraft designed by Kurt Tank at Focke-Wulf in the late 1930s and widely used during World War II. Along with its well-known counterpart, the ...

flown by ''Leutnant

() is the lowest junior officer rank in the armed forces of Germany ( Bundeswehr), the Austrian Armed Forces, and the military of Switzerland.

History

The German noun (with the meaning "" (in English "deputy") from Middle High German «locum ...

'' Robert Spreckels. Although Herrick and his navigator bailed out when their aircraft was shot down, they were too low for their parachutes to open and were killed. Herrick landed in the sea and his body washed ashore two weeks later. Spreckels later shot down Braham, who became a prisoner of war. Interrogated by Spreckels, he was reportedly advised that Herrick had made a good account of himself before being shot down.

Herrick is credited with shooting down six aircraft and sharing in two other aircraft destroyed and two damaged. He is buried in the Commonwealth War Graves Commission

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) is an intergovernmental organisation of six independent member states whose principal function is to mark, record and maintain the graves and places of commemoration of Commonwealth of Nations mil ...

's section of the Frederikshavn Cemetery in Denmark.

The month after Herrick's death, it was announced that he was to be awarded the United States Air Medal

The Air Medal (AM) is a military decoration of the United States Armed Forces. It was created in 1942 and is awarded for single acts of heroism or meritorious achievement while participating in aerial flight.

Criteria

The Air Medal was establi ...

for his services in the Solomon Islands; the medal was formally presented to his parents at Wellington

Wellington is the capital city of New Zealand. It is located at the south-western tip of the North Island, between Cook Strait and the Remutaka Range. Wellington is the third-largest city in New Zealand (second largest in the North Island ...

in June 1945 by Captain Lloyd Gray, the naval attache at the United States Embassy

The United States has the second largest number of active diplomatic posts of any country in the world after the People's Republic of China, including 272 bilateral posts (embassies and consulates) in 174 countries, as well as 11 permanent miss ...

. The citation specifically noted his exploits in the Solomon Islands area during the period of May to June 1943. Two of his brothers also served in the RAF; both died on flying operations in the early years of the war. An aunt, Ruth Herrick

Hermione Ruth Herrick (19 January 1889 – 21 January 1983) was the Chief Commissioner for the New Zealand Girl Guides and the first director of the Women's Royal New Zealand Naval Service.

Biography

Herrick was born in Ruataniwha, Centra ...

, played a key role in the establishment of the Women's Royal New Zealand Naval Service

The Women's Royal New Zealand Naval Service (WRNZNS) was the female auxiliary of the Royal New Zealand Navy (RNZN). Raised during the Second World War, most of its personnel, known as Wrens, served as signallers and operators of naval equipment o ...

.

Notes

References

* * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Herrick, Michael 1921 births 1944 deaths People from Hastings, New Zealand New Zealand World War II flying aces New Zealand World War II pilots Royal Air Force squadron leaders The Few New Zealand military personnel killed in World War II New Zealand recipients of the Distinguished Flying Cross (United Kingdom) Foreign recipients of the Air Medal Aviators killed by being shot down