Maxime Weygand on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

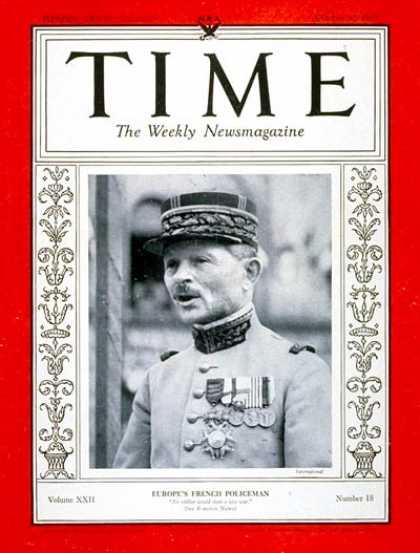

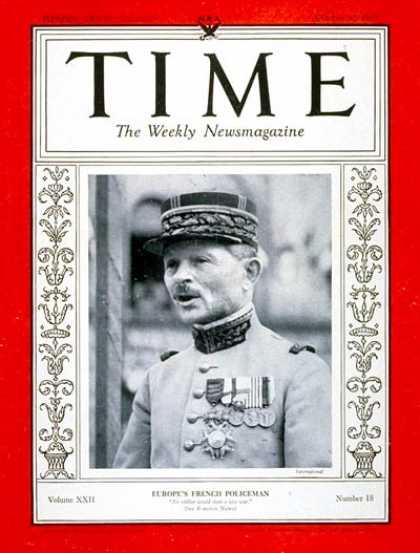

Maxime Weygand (; 21 January 1867 – 28 January 1965) was a French military commander in

Weygand was born on 21 January 1867 at 39 Boulevard de Waterloo in

Weygand was born on 21 January 1867 at 39 Boulevard de Waterloo in

During the Dreyfus affair, Weygand was one of the most anti-Dreyfusard officers of his regiment, supporting the widow of Colonel Hubert-Joseph Henry, who had committed suicide after the discovery of the falsification of the charges against Captain

During the Dreyfus affair, Weygand was one of the most anti-Dreyfusard officers of his regiment, supporting the widow of Colonel Hubert-Joseph Henry, who had committed suicide after the discovery of the falsification of the charges against Captain

Weygand returned from Poland to his duties with the interallied council overseeing the implementation of the Versailles treaty and the renegotiation of peace with

Weygand returned from Poland to his duties with the interallied council overseeing the implementation of the Versailles treaty and the renegotiation of peace with  Weygand returned to France in 1925 embittered, seeing his recall as the product of political machinations and intra-army rivalries. Regardless, he was awarded the

Weygand returned to France in 1925 embittered, seeing his recall as the product of political machinations and intra-army rivalries. Regardless, he was awarded the

Immediately after the German army arrived in France, Weygand feared a Paris Commune-like event might happen.

Weygand's service during the Second World War is controversial and debated. His reputation came under substantial criticism from

Immediately after the German army arrived in France, Weygand feared a Paris Commune-like event might happen.

Weygand's service during the Second World War is controversial and debated. His reputation came under substantial criticism from

Generals of World War II

{{DEFAULTSORT:Weygand, Maxime 1867 births 1965 deaths Chiefs of the Staff of the French Army Military personnel from Brussels French generals 19th-century French military personnel French Army generals of World War I French Army generals of World War II Generalissimos Jewish French history Members of the Académie Française Lycée Louis-le-Grand alumni École Spéciale Militaire de Saint-Cyr alumni High commissioners of the Levant Order of the Francisque recipients Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour Commanders of the Order of the Crown (Belgium) Recipients of the Order of Lāčplēsis, 2nd class Recipients of the Virtuti Militari Recipients of the Croix de Guerre 1939–1945 (France) Recipients of the Croix de guerre des théâtres d'opérations extérieures Recipients of the Croix de guerre (Belgium) Recipients of the Distinguished Service Medal (US Army) Honorary companions of the Order of the Bath Honorary Knights Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George French anti-communists People of Vichy France French collaborators with Nazi Germany Ministers of war and national defence of France 20th-century French military personnel Foreign recipients of the Distinguished Service Medal (United States) Governors general of Algeria Belgian emigrants to France Prisoners and detainees of France French people imprisoned in Germany

World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

and World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, as well as a high ranking member of the Vichy regime

Vichy France (; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was a French rump state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II, established as a result of the French capitulation after the defeat against ...

.

Born in Belgium, Weygand was raised in France and educated at the Saint-Cyr military academy in Paris. After graduating in 1887, he went on to become an instructor at the Saumur Cavalry School. During World War I, Weygand served as a staff officer

A military staff or general staff (also referred to as army staff, navy staff, or air staff within the individual services) is a group of officers, enlisted, and civilian staff who serve the commander of a division or other large milita ...

to General (later Marshal) Ferdinand Foch

Ferdinand Foch ( , ; 2 October 1851 – 20 March 1929) was a French general, Marshal of France and a member of the Académie Française and French Academy of Sciences, Académie des Sciences. He distinguished himself as Supreme Allied Commander ...

. He then served as an advisor to Poland in the Polish–Soviet War

The Polish–Soviet War (14 February 1919 – 18 March 1921) was fought primarily between the Second Polish Republic and the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, following World War I and the Russian Revolution.

After the collapse ...

and later High Commissioner of the Levant

The high commissioner of France in the Levant (; ), named after 1941 the general delegate of Free France in the Levant (), was the highest ranking authority representing France (and Free France during World War II) in the Mandate for Syria and t ...

. In 1931, Weygand was appointed Chief of Staff of the French Army

Chief may refer to:

Title or rank

Military and law enforcement

* Chief master sergeant, the ninth, and highest, enlisted rank in the U.S. Air Force and U.S. Space Force

* Chief of police, the head of a police department

* Chief of the bo ...

, a position he served until his retirement in 1935 at the age of 68.

In May 1940, Weygand was recalled for active duty and assumed command of the French Army

The French Army, officially known as the Land Army (, , ), is the principal Army, land warfare force of France, and the largest component of the French Armed Forces; it is responsible to the Government of France, alongside the French Navy, Fren ...

during the German invasion. Following a series of military setbacks, Weygand advised armistice and France subsequently capitulated. He joined Philippe Pétain

Henri Philippe Bénoni Omer Joseph Pétain (; 24 April 1856 – 23 July 1951), better known as Marshal Pétain (, ), was a French marshal who commanded the French Army in World War I and later became the head of the Collaboration with Nazi Ger ...

's Vichy regime as Minister for Defence and served until September 1940, when he was appointed Delegate-General in French North Africa

French North Africa (, sometimes abbreviated to ANF) is a term often applied to the three territories that were controlled by France in the North African Maghreb during the colonial era, namely Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia. In contrast to French ...

. He was noted for exceptionally harsh implementation of German Anti-Semitic policies while in this position. Despite this, Weygand favoured only limited collaboration

Collaboration (from Latin ''com-'' "with" + ''laborare'' "to labor", "to work") is the process of two or more people, entities or organizations working together to complete a task or achieve a goal. Collaboration is similar to cooperation. The ...

with Germany and was dismissed from his post in November 1941 on Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

's demand. Following the Allied invasion of North Africa in November 1942, Weygand was arrested by the Germans and imprisoned at Itter Castle in Austria until May 1945. After returning to France, he was held as a collaborator at the Val-de-Grâce

The Val-de-Grâce (; Hôpital d'instruction des armées du Val-de-Grâce or HIA Val-de-Grâce) was a military hospital located at 74 boulevard de Port-Royal in the 5th arrondissement of Paris, France. It was closed as a hospital in 2016.

History

...

but was released in 1946 and cleared of charges in 1948. He died in January 1965 in Paris at the age of 98.

Early years

Weygand was born on 21 January 1867 at 39 Boulevard de Waterloo in

Weygand was born on 21 January 1867 at 39 Boulevard de Waterloo in Brussels

Brussels, officially the Brussels-Capital Region, (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) is a Communities, regions and language areas of Belgium#Regions, region of Belgium comprising #Municipalit ...

of unknown parents. The biographer Bernard Destremau gave five possible sets of parents: Leopold II with either the wife of the Austrian diplomat Count Zichy or an anonymous Mexican woman (dismissed as doubtful); Charlotte, wife of then-Archduke Maximilian of Austria, and the Belgian officer Alfred van der Smissen (dismissed as impossible); a tutor named David Cohen and a French woman named Thérèse Denimal ("lacks credibility"); Charlotte and a Mexican Colonel Lopez ("difficult to hide"); and, according to Antony Clayton most likely, Maximilian of Austria and a Mexican dancer called Lupe. The various theories of Mexican extraction, however, require some kind of record forgery; regardless, Weygand's short stature and appearance may suggest a partially-European antecedence with a connection to the Austrian court suggested by the funds provided for his education in youth. In 2003, the French journalist Dominique Paoli claimed to have found evidence that Weygand's father was indeed van der Smissen, but the mother was Mélanie Zichy-Metternich, lady-in-waiting to Charlotte (and daughter of Prince Klemens von Metternich

Klemens Wenzel Nepomuk Lothar, Prince of Metternich-Winneburg zu Beilstein ( ; 15 May 1773 – 11 June 1859), known as Klemens von Metternich () or Prince Metternich, was a German statesman and diplomat in the service of the Austrian Empire. ...

, Austrian Chancellor). Paoli further claimed that Weygand had been born in mid-1865, not January 1867 as is generally claimed.

Regardless, throughout his life, Weygand maintained he did not know his true parentage. While an infant he was sent to Marseille

Marseille (; ; see #Name, below) is a city in southern France, the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Bouches-du-Rhône and of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur Regions of France, region. Situated in the ...

to be raised by a widow named Virginie Saget, whom he originally took to be his mother. At the age of seven, he was transferred to the household of David Cohen, an Italo-Belgian leather merchant in Marseille, with partner Thérèse Denimal (later de Nimal). Then-called Maxime de Nimal, he attended schools in Cannes and then Asniéres, fees likely paid by the Belgian royal household or government, where his scholastic accomplishment were recognised. He was transferred to a boarding school in Paris and thence to the Lycée Louis-le-Grand

The Lycée Louis-le-Grand (), also referred to simply as Louis-le-Grand or by its acronym LLG, is a public Lycée (French secondary school, also known as sixth form college) located on Rue Saint-Jacques (Paris), rue Saint-Jacques in central Par ...

where Maxime was baptised Catholic. After a disciplinary issue he was expelled and barred from Parisian schools, ending up at schools in Toulon and then Aix-en-Provence

Aix-en-Provence, or simply Aix, is a List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, city and Communes of France, commune in southern France, about north of Marseille. A former capital of Provence, it is the Subprefectures in France, s ...

. Returning to Paris some years later, he was rejected from the French Navy and decided to seek admission to the École spéciale militaire de Saint-Cyr

The École spéciale militaire de Saint-Cyr (, , abbr. ESM) is a French military academy, and is often referred to as Saint-Cyr (). It is located in Coëtquidan in Guer, Morbihan, Brittany. Its motto is ''Ils s'instruisent pour vaincre'', litera ...

. Admitted in the top half of the class, he was denied a full French uniform due to his unclear heritage, but the slight ignored he graduated in the top ten of his class. Highly competent at fencing and horsemanship, he was accepted as a junior cavalry officer at Saumur – connecting him to a network of upper-class officers – but again rejected as a non-citizen. After some payments by David Cohen, Maxime was adopted by an accountant in Arras called Francis-Joseph Weygand. Taking the name Maxime Weygand, he was posted to a French cavalry regiment in October 1888.

He says little about his youth in his memoirs, devoting to it only four pages out of 651. He mentions the ''gouvernante'' and the ''aumônier'' of his college, who instilled in him a strong Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

faith. His memoirs essentially begin with his entry into the preparatory class of Saint-Cyr Military School in Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

.

Military career

During the Dreyfus affair, Weygand was one of the most anti-Dreyfusard officers of his regiment, supporting the widow of Colonel Hubert-Joseph Henry, who had committed suicide after the discovery of the falsification of the charges against Captain

During the Dreyfus affair, Weygand was one of the most anti-Dreyfusard officers of his regiment, supporting the widow of Colonel Hubert-Joseph Henry, who had committed suicide after the discovery of the falsification of the charges against Captain Alfred Dreyfus

Alfred Dreyfus (9 October 1859 – 12 July 1935) was a French Army officer best known for his central role in the Dreyfus affair. In 1894, Dreyfus fell victim to a judicial conspiracy that eventually sparked a major political crisis in the Fre ...

.

He was promoted to captain in 1896. Weygand chose not to attempt the difficult preparation to the ''École Supérieure de Guerre

École or Ecole may refer to:

* an elementary school in the French educational stages normally followed by secondary education establishments (collège and lycée)

* École (river), a tributary of the Seine flowing in région Île-de-France

* Éco ...

'' (the French staff college) because of his desire, he said, to keep contact with the troops. This did not prevent him from later becoming an instructor at the cavalry school at Saumur. Along with Joseph Joffre

Joseph Jacques Césaire Joffre , (; 12 January 1852 – 3 January 1931) was a French general who served as Commander-in-Chief of French forces on the Western Front (World War I), Western Front from the start of World War I until the end of 19 ...

and Ferdinand Foch

Ferdinand Foch ( , ; 2 October 1851 – 20 March 1929) was a French general, Marshal of France and a member of the Académie Française and French Academy of Sciences, Académie des Sciences. He distinguished himself as Supreme Allied Commander ...

, Weygand attended the Imperial Russian Army

The Imperial Russian Army () was the army of the Russian Empire, active from 1721 until the Russian Revolution of 1917. It was organized into a standing army and a state militia. The standing army consisted of Regular army, regular troops and ...

manoeuvres in 1910; his account mentions a great deal of pomp and many gala dinners, but also records Russian reluctance to discuss military details. Promoted with unusual rapidity to lieutenant colonel in 1912, he attended in 1913 the ''Centre des Hautes Etudes Militaires'', set up in January 1911 to teach combined arms

Combined arms is an approach to warfare that seeks to integrate different combat arms of a military to achieve mutually complementary effects—for example, using infantry and armoured warfare, armour in an Urban warfare, urban environment in ...

operations and staff work, despite not having been ''"breveté"'' (passed staff college). During his studies, he was noticed for his brilliance in staff work by Joffre and Foch. Weygand attended the last pre-war French grand manoeuvres in 1913 and commented that it had revealed "intolerable insufficiencies" such as two divisions becoming mixed up.

First World War

Early war

At the outbreak of the war, he was posted as a staff officer with the 5ème Hussars. His regiment was deployed to the Franco-German border on 28 July 1914 and later fought at the Battle of Morhange. On 17 August, he became chief of staff toFerdinand Foch

Ferdinand Foch ( , ; 2 October 1851 – 20 March 1929) was a French general, Marshal of France and a member of the Académie Française and French Academy of Sciences, Académie des Sciences. He distinguished himself as Supreme Allied Commander ...

, the commander of the new Ninth Army. Weygand served under Foch for much of the rest of the war.

The professional partnership between Foch and Weygand was close and fruitful, with Weygand operating as a highly competent subordinate able to translate Foch's instructions into clearer orders, analyse ideas, and collate information. Foch referred to Weygand with praise, believing that their views were practically identical. Weygand finalised the plans for the 9th Army's attack at the First Battle of the Marne

The First Battle of the Marne or known in France as the Miracle on the Marne () was a battle of the First World War fought from the 5th to the 12th September 1914. The German army invaded France with a plan for winning the war in 40 days by oc ...

and, in doing so, became one of the first staff officers to reconnoitre the battlefield from the air. Weygand supported Foch, who was appointed to coordinate the Belgian, British, and French forces in the northern sector, during the Race to the Sea

The Race to the Sea (; , ) took place from 17 September to 19 October 1914 during the First World War, after the Battle of the Frontiers () and the German Empire, German advance into France. The invasion had been stopped at the First Battle of ...

and First Ypres. Weygand was promoted to full colonel in early 1915.

The mounting French casualties over the course of 1915 were reflected in Weygand's campaign notes; the need for further cooperation between French and British armies utilised Weygand's communicative skills and he developed a working relationship with some British counterparts. Weygand was promoted to général de brigade in 1916. He later wrote of the Anglo-French Somme Offensive in 1916, at which Foch commanded French Army Group North, that it had seen "constant mix-ups with an ally he Britishlearning how to run a large operation and whose doctrines and methods were not yet in accordance with ours". At a meeting on 3 July 1916 where Joffre and Haig came to non-speaking terms, Weygand, Foch, and Henry Wilson

Henry Wilson (born Jeremiah Jones Colbath; February 16, 1812 – November 22, 1875) was the 18th vice president of the United States, serving from 1873 until his death in 1875, and a United States Senate, senator from Massachusetts from 1855 to ...

were able to restore a working relationship between the armies. He also took effective command of the army group as alternate when Foch was in ill health; during tensions between Foch and subordinates, Weygand helped to mediate disputes.

After Joffre was replaced by Robert Nivelle

Robert Georges Nivelle (15 October 1856 – 22 March 1924) was a French artillery general officer who served in the Boxer Rebellion and the First World War. In May 1916, he succeeded Philippe Pétain as commander of the French Second Army in the ...

in late 1916, criticism of Foch also intensified, leading to Foch being relieved of his northern command; Weygand saw the politician's treatment of Foch as intolerable. At Foch's suggestion, Weygand's name was submitted for command of an infantry brigade, but after Foch was assigned out of inactivity to instead create a contingency plan for a German invasion of France via Switzerland, Weygand decided to stay with Foch. As part of this planning, Weygand served as head of a mission to Switzerland to discuss Anglo-French support if Switzerland were breached by German troops. Weygand later accompanied the British Chief of the Imperial General Staff

Chief of the General Staff (CGS) has been the title of the professional head of the British Army since 1964. The CGS is a member of both the Chiefs of Staff Committee and the Army Board; he is also the Chair of the Executive Committee of the A ...

, General Sir William Robertson, on an inspection of the Italian front in early 1917 to discuss Anglo-French support for Italy's Isonzo campaign. When Weygand and Foch were briefed on the Nivelle offensive, the two men expressed misgivings. After its failure, Nivelle was removed as French commander-in-chief and replaced with Philippe Petain. Foch was appointed chief of the army general staff in 19 May 1917; writing to his wife, Weygand expressed his loyalty to Foch and gave up his applications for a field command.

Supreme War Council

British prime ministerDavid Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. A Liberal Party (United Kingdom), Liberal Party politician from Wales, he was known for leadi ...

pushed for the creation of a Supreme War Council, which was formally established on 7 November 1917. Keen to sideline the British Chief of the Imperial General Staff

Chief of the General Staff (CGS) has been the title of the professional head of the British Army since 1964. The CGS is a member of both the Chiefs of Staff Committee and the Army Board; he is also the Chair of the Executive Committee of the A ...

, General Sir William Robertson, he insisted that, as French Army chief of the General Staff, Foch could not also be French permanent military representative (PMR) on the SWC. Paul Painlevé

Paul Painlevé (; 5 December 1863 – 29 October 1933) was a French mathematician and statesman. He served twice as Prime Minister of France, Prime Minister of the French Third Republic, Third Republic: 12 September – 13 November 1917 and 17 A ...

, French prime minister

The prime minister of France (), officially the prime minister of the French Republic (''Premier ministre de la République française''), is the head of government of the French Republic and the leader of its Council of Ministers.

The prime m ...

until 13 November, believed that Lloyd George was already pushing for Foch to be Supreme Allied Commander so wanted him as PMR not French Chief of Staff.

The new prime minister, Georges Clemenceau

Georges Benjamin Clemenceau (28 September 1841 – 24 November 1929) was a French statesman who was Prime Minister of France from 1906 to 1909 and again from 1917 until 1920. A physician turned journalist, he played a central role in the poli ...

, wanted Foch as PMR to increase French control over the Western Front, but was persuaded to appoint Weygand, seen very much as Foch's sidekick, instead. Clemenceau told US President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

's envoy, Colonel Edward M. House that he would put in a "second- or third-rate man" as PMR and "let the thing drift where it will".

Weygand was the most junior of the PMRs (the others being the Italian Luigi Cadorna

Marshal of Italy Luigi Cadorna, (4 September 1850 – 21 December 1928) was an Italian people, Italian general, Marshal of Italy and Count, most famous for being the Chief of Staff of the Italian Army from 1914 until 1917 during World War I ...

, the American Tasker H. Bliss

Tasker Howard Bliss (December 31, 1853 – November 9, 1930) was a United States Army officer who served as Chief of Staff of the United States Army during World War I, from September 22, 1917, until May 18, 1918. He was also a diplomat involved i ...

, and the British Henry Wilson

Henry Wilson (born Jeremiah Jones Colbath; February 16, 1812 – November 22, 1875) was the 18th vice president of the United States, serving from 1873 until his death in 1875, and a United States Senate, senator from Massachusetts from 1855 to ...

, later replaced by Henry Rawlinson). He was promoted général de division

Divisional general is a general officer rank who commands an army division. The rank originates from the French Revolutionary System, and is used by a number of countries. The rank is above a brigade general, and normally below an army corps ...

(equivalent to the Anglophone rank of major general) in 1918. This promotion was specifically because of his appointment as a PMR.

However, Clemenceau only agreed to set up an Allied General Reserve if Foch rather than Weygand were earmarked to command it. The Reserve was shelved for the time being at a SWC Meeting in London (14–15 March 1918) as the national commanders in chief, Philippe Pétain

Henri Philippe Bénoni Omer Joseph Pétain (; 24 April 1856 – 23 July 1951), better known as Marshal Pétain (, ), was a French marshal who commanded the French Army in World War I and later became the head of the Collaboration with Nazi Ger ...

and Sir Douglas Haig, were reluctant to release divisions.

Supreme Allied Command Staff

Weygand was in charge of Foch's staff when his patron was appointedSupreme Allied Commander

Supreme Allied Commander is the title held by the most senior commander within certain multinational military alliances. It originated as a term used by the Allies during World War I, and is currently used only within NATO for Supreme Allied Co ...

in the spring of 1918, and was Foch's right-hand man throughout his victories in the late summer and until the end of the war.

Weygand initially headed a small staff of 25–30 officers, with Brigadier General Pierre Desticker as his deputy. There was a separate head for each of the departments, e.g. Operations, Intelligence, Q (Quartermaster). From June 1918 onwards, under British pressure, Foch and Weygand poached staff officers from the French Commander-in-Chief Philippe Pétain

Henri Philippe Bénoni Omer Joseph Pétain (; 24 April 1856 – 23 July 1951), better known as Marshal Pétain (, ), was a French marshal who commanded the French Army in World War I and later became the head of the Collaboration with Nazi Ger ...

(Lloyd George's tentative suggestion of a multinational Allied staff was vetoed by President Wilson). By early August Colonel Payot (responsible for supply and transport) had moved to Foch's HQ, as had the Military Missions from the other Allied HQs; in Greenhalgh's words this "put real as opposed to nominal power into Foch's hands". From early July onwards, British military and political leaders came to regret Foch's increased power, but Weygand later recorded that they had only themselves to blame as they had pushed for the change.

Like Foch and most French leaders of his era (Clemenceau, who had lived in the US as a young man, was a rare exception), Weygand could not speak enough English to "sustain a conversation" (German, not English, was the most common second language in which French officers were qualified). Competent interpreters were therefore vital.

Weygand drew up the memorandum for the meeting of Foch with the national commanders-in-chief (Haig, Pétain and John J. Pershing) on 24 July 1918, the only such meeting before the autumn, in which Foch urged (successfully) the liberation of the Marne salient captured by the Germans in May (this offensive would become the Second Battle of the Marne, for which Foch was promoted Marshal of France), along with further offensives by the British and by the Americans at St Mihiel. Weygand personally delivered the directive for the Amiens attack to Haig. Foch and Weygand were shown around the liberated St. Mihiel sector by Pershing on 20 September.

Weygand later (in 1922) questioned whether Pétain's planned offensive by twenty-five divisions in Lorraine in November 1918 could have been supplied through a "zone of destruction" through which the Germans were retreating; his own and Foch's doubts about the feasibility of the plans were another factor in the seeking of an armistice. In 1918 Weygand served on the armistice negotiations, and it was Weygand who read out the armistice conditions to the Germans at Compiègne

Compiègne (; ) is a Communes of France, commune in the Oise Departments of France, department of northern France. It is located on the river Oise (river), Oise, and its inhabitants are called ''Compiégnois'' ().

Administration

Compiègne is t ...

, in the railway carriage. He can be spotted in photographs of the armistice delegates, and also standing behind Foch's shoulder at Pétain's investiture as Marshal of France

Marshal of France (, plural ') is a French military distinction, rather than a military rank, that is awarded to General officer, generals for exceptional achievements. The title has been awarded since 1185, though briefly abolished (1793–1804) ...

at the end of 1918.

Paris Peace Conference

Weygand agreed with Foch that French security – the consequences of which were impressed during a tour of the liberated German-occupied zones in late 1918 – required territorial expansion to theRiver Rhine

The Rhine ( ) is one of the major rivers in Europe. The river begins in the Swiss canton of Graubünden in the southeastern Swiss Alps. It forms part of the Swiss-Liechtenstein border, then part of the Swiss-Austrian border. From Lake Const ...

as a buffer zone

A buffer zone, also historically known as a march, is a neutral area that lies between two or more bodies of land; usually, between countries. Depending on the type of buffer zone, it may serve to separate regions or conjoin them.

Common types o ...

. Their dislike of politicians, who they viewed as having little understanding of war realities or military issues, intensified when the French political class ruled out creating a French client state in the Rhineland

The Rhineland ( ; ; ; ) is a loosely defined area of Western Germany along the Rhine, chiefly Middle Rhine, its middle section. It is the main industrial heartland of Germany because of its many factories, and it has historic ties to the Holy ...

. They similarly agreed that the then-proposed League of Nations

The League of Nations (LN or LoN; , SdN) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace ...

would do little to ensure peace and that the planned alliances between France, Britain, and the United States would be insufficient to guarantee French security.

Foch's untactful expression of his views unnerved the Big Four civilian leaders at the peace conference: American president Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

, British prime minister David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. A Liberal Party (United Kingdom), Liberal Party politician from Wales, he was known for leadi ...

, French president Georges Clemenceau

Georges Benjamin Clemenceau (28 September 1841 – 24 November 1929) was a French statesman who was Prime Minister of France from 1906 to 1909 and again from 1917 until 1920. A physician turned journalist, he played a central role in the poli ...

, and Italian prime minister Vittorio Emanuele Orlando

Vittorio Emanuele Orlando (; 19 May 1860 – 1 December 1952) was an Italian statesman, who served as the prime minister of Italy from October 1917 to June 1919. Orlando is best known for representing Italy in the 1919 Paris Peace Conference with ...

. Weygand harboured similar disdain, calling them in a diary "the four old men". Because of Foch's popularity as victor of the war, he could not be easily criticised. Attacks therefore fell on Weygand who was conspiratorially accused, by among others Woodrow Wilson and Lloyd George, as driving Foch's radical positions.

Interwar

Poland

During thePolish–Soviet War

The Polish–Soviet War (14 February 1919 – 18 March 1921) was fought primarily between the Second Polish Republic and the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, following World War I and the Russian Revolution.

After the collapse ...

, Weygand was a member of the Interallied Mission to Poland of July and August 1920, supporting the infant Second Polish Republic

The Second Polish Republic, at the time officially known as the Republic of Poland, was a country in Central and Eastern Europe that existed between 7 October 1918 and 6 October 1939. The state was established in the final stage of World War I ...

against the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (Russian SFSR or RSFSR), previously known as the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic and the Russian Soviet Republic, and unofficially as Soviet Russia,Declaration of Rights of the labo ...

. (He had not been on the 1919 French Military Mission to Poland headed by General Paul Prosper Henrys.) The Interallied Mission, which also included French diplomat Jean Jules Jusserand and the British diplomat Lord Edgar Vincent D'Abernon, achieved little: its report was submitted after the Polish Armed Forces

The Armed Forces of the Republic of Poland (, ; abbreviated SZ RP), also called the Polish Armed Forces and popularly called in Poland (, roughly "the Polish Military"—abbreviated ''WP''), are the national Military, armed forces of the Poland, ...

had won the crucial Battle of Warsaw. Nonetheless, the presence of the Allied missions in Poland gave rise to a myth that the timely arrival of Allied forces saved Poland.

Weygand travelled to Warsaw

Warsaw, officially the Capital City of Warsaw, is the capital and List of cities and towns in Poland, largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the Vistula, River Vistula in east-central Poland. Its population is officially estimated at ...

expecting to assume command of the Polish army

The Land Forces () are the Army, land forces of the Polish Armed Forces. They currently contain some 110,000 active personnel and form many components of the European Union and NATO deployments around the world. Poland's recorded military histor ...

, yet those expectations were quickly dashed. He had no good reply for Józef Piłsudski

Józef Klemens Piłsudski (; 5 December 1867 – 12 May 1935) was a Polish statesman who served as the Chief of State (Poland), Chief of State (1918–1922) and first Marshal of Poland (from 1920). In the aftermath of World War I, he beca ...

, who on 24 July during their first meeting asked "How many divisions do you bring?" Weygand had none to offer. From 27 July Weygand was an adviser to the Polish Chief of Staff, Tadeusz Rozwadowski. It was a difficult position; most Polish officers regarded him as an interloper, and spoke only Polish, which he did not understand. At the end of July he proposed that the Poles hold the length of the Bug River

The Bug or Western Bug is a major river in Central Europe that flows through Belarus (border), Poland, and Ukraine, with a total length of .Vistula

The Vistula (; ) is the longest river in Poland and the ninth-longest in Europe, at in length. Its drainage basin, extending into three other countries apart from Poland, covers , of which is in Poland.

The Vistula rises at Barania Góra i ...

river; both plans were rejected. One of his few lasting contributions was to insist on replacing the existing system of spoken orders by written documents; he also provided advice on logistics and construction of modern entrenchments. Norman Davies

Ivor Norman Richard Davies (born 8 June 1939) is a British and Polish historian, known for his publications on the history of Europe, Poland and the United Kingdom. He has a special interest in Central and Eastern Europe and is UNESCO Profes ...

writes: "on the whole he was quite out of his element, a man trained to give orders yet placed among people without the inclination to obey, a proponent of defence in the company of enthusiasts for the attack". During another meeting with Piłsudski on 18 August, Weygand became offended and threatened to leave, depressed by his failure and dismayed by Poland's disregard for the Allied powers.

At the station at Warsaw on 25 August he was consoled by the award of the Virtuti Militari

The War Order of Virtuti Militari (Latin: ''"For Military Virtue"'', ) is Poland's highest military decoration for heroism and courage in the face of the enemy at war. It was established in 1792 by the last King of Poland Stanislaus II of Poland, ...

, 2nd class; at Paris on the 28th he was cheered by crowds lining the platform of the Gare de l'Est

The Gare de l'Est (; English: "Station of the East" or "East station"), officially Paris Est, is one of the seven large mainline railway station termini in Paris, France. It is located in the 10th arrondissement, not far southeast from the Ga ...

, kissed on both cheeks by the premier, Alexandre Millerand. Promoted to ''général corps d'armée'' and advanced to ''Commandeur'' in the Legion of Honour

The National Order of the Legion of Honour ( ), formerly the Imperial Order of the Legion of Honour (), is the highest and most prestigious French national order of merit, both military and Civil society, civil. Currently consisting of five cl ...

, Weygand could not understand what had happened and admitted in his memoirs what he said to a French journalist already on 21 August 1920: "the victory was Polish, the plan was Polish, the army was Polish"., as cited in: , also reprinted in: As Norman Davies notes: "He was the first uncomprehending victim, as well as the chief beneficiary, of a legend already in circulation that he, Weygand, was the victor of Warsaw. This legend persisted for more than forty years even in academic circles".

Levant and ''CHEM'' directorship

Turkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

after they rejected the Treaty of Sèvres

The Treaty of Sèvres () was a 1920 treaty signed between some of the Allies of World War I and the Ottoman Empire, but not ratified. The treaty would have required the cession of large parts of Ottoman territory to France, the United Kingdom, ...

. Weygand declined to serve on a proposed French occupation force to occupy the Ruhr valley after Germany refused to meet reparation payments; he similarly refused appointment to Poland.

In 1922, the Poincaré ministry appointed Weygand High Commissioner of the Levant

The high commissioner of France in the Levant (; ), named after 1941 the general delegate of Free France in the Levant (), was the highest ranking authority representing France (and Free France during World War II) in the Mandate for Syria and t ...

to govern the French mandate in Lebanon and Syria, replacing Henri Gouraud. Putting an end of Gouraud's coercive pacification campaigns, Weygand was largely conciliatory and devolved most policing responsibilities to local gendarmes. He also supervised infrastructure projects to support export of cotton and silk, reformed the school system, and established Damascus University

Damascus University () is the largest and oldest university in Syria, located in the capital Damascus, with campuses in other Syrian cities. It was founded in 1923 as the Syrian University () through the merger of the Faculty of Medicine of Dama ...

in June 1923. Administration in the mandate was also reformed and the basis for the modern borders of Syria and Lebanon established. Weygand's wife Renée joined him there and they enjoyed their time in Beirut. However, with the left-wing victory in the May 1924 elections, Weygand was recalled in place of Maurice Sarrail that December.

Weygand returned to France in 1925 embittered, seeing his recall as the product of political machinations and intra-army rivalries. Regardless, he was awarded the

Weygand returned to France in 1925 embittered, seeing his recall as the product of political machinations and intra-army rivalries. Regardless, he was awarded the Grand Cross of the Legion of Honor

The National Order of the Legion of Honour ( ), formerly the Imperial Order of the Legion of Honour (), is the highest and most prestigious French national order of merit, both military and Civil society, civil. Currently consisting of five cl ...

. Denied command in Morocco against the Rif War

The Rif War (, , ) was an armed conflict fought from 1921 to 1926 between Spain (joined by France in 1924) and the Berber tribes of the mountainous Rif region of northern Morocco.

Led by Abd el-Krim, the Riffians at first inflicted several ...

out of fear for his success, command in Syria since it would embarrass the government, and command in Germany due to his closeness with Foch, he was made director of the ''Centre de Hautes Etudes Militaries'' (Center for Higher Military Studies) from 1925 to 1930. While Weygand supported development of a doctrine of rapid armoured assault with close air support, the government's view – which feared professionalisation of the army as a threat to regime stability and saw investment in tanks as financially ruinous – prevailed. The further programme to shorten conscripts' service was voted through in the late 1920s to Weygand's disapproval: he feared that the left was intending to replace the professional army with a purely defensive national guard while drowning units in basic training, making it impossible to train for large unit operations. Settling at Morlaix

Morlaix (; , ) is a commune in the Finistère department of Brittany in northwestern France. It is a sub-prefecture of the department.

History

The Battle of Morlaix, part of the Hundred Years' War, was fought near the town on 30 Septembe ...

in Brittany

Brittany ( ) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the north-west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica in Roman Gaul. It became an Kingdom of Brittany, independent kingdom and then a Duch ...

near Foch, the five years at the ''Centre'' also gave him time to write two books, biographies of French marshals Foch and Turenne.

Head of the army

The opening of the question of succession as chief of the general staff from 1927 placed Weygand again in the spotlight: Foch, for his part, supported his protégé and made his views clear before his death in 1929. The left-wing war ministerPaul Painlevé

Paul Painlevé (; 5 December 1863 – 29 October 1933) was a French mathematician and statesman. He served twice as Prime Minister of France, Prime Minister of the French Third Republic, Third Republic: 12 September – 13 November 1917 and 17 A ...

supported Louis Maurin

Louis Félix Thomas Maurin (; 5 January 1869 – 6 June 1956) was a French army general who was twice Minister of the Armed Forces (France), Minister of War in the 1930s.

Before and during World War I (1914–18) he was a strong advocate of motor ...

. But after Petain's announced his support for Weygand and buttressed it with the recommendation that Weygand should be further appointed inspector-general on Petain's retirement (designating Weygand as commander-in-chief on mobilisation), the topic of the appointment became thoroughly politicised. The end of Briand's government in November 1929 led to a right-wing government under André Tardieu

André Pierre Gabriel Amédée Tardieu (; 22 September 1876 – 15 September 1945) was three times Prime Minister of France (3 November 1929 – 17 February 1930; 2 March – 4 December 1930; 20 February – 10 May 1932) and a dominant figure of ...

until February 1930 that made André Maginot war minister. Attacked as a right-wing Catholic cavalry officer with aristocratic haughtiness and designs against the Third Republic with profligate plans for military expenditure in a time of austerity, Weygand was forced to disavow in a statement to Parliament any political activities and affirm his loyalty to the republican regime. The eventual compromise saw Weygand made chief of staff with the more politically-safe Maurice Gamelin

Maurice Gustave Gamelin (; 20 September 1872 – 18 April 1958) was a French general. He is remembered for his disastrous command (until 17 May 1940) of the French military during the Battle of France in World War II and his steadfast defence of ...

as deputy; Weygand was appointed chief of staff on 3 January 1930 at the age of 63. On Petain's retirement to the post of air defence inspector on 10 February 1931, Weygand took up the vice presidency of the ''Conseil supérieur de la guerre The Conseil supérieur de la guerre (, ''Superior War Council'', abbr. CSG) was the highest military body in France under the Third French Republic, Third Republic. It was under the presidency of the Minister of War (France), Minister of War, althou ...

'' as well as inspector-general of the army; Gamelin was appointed chief of staff in his place.

Weygand's remained as vice president of the ''Conseil'' until his mandatory requirement at the age of 68 in February 1935. During his years in charge of the military, he attempted to push for military modernisation and increased service requirements to match the threat posed by Germany. However, the Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

came with substantial political instability, including street violence, and fourteen prime ministers between January 1930 and 1935. Attempts to broker international disarmament agreements were collapsed and the politicians were unwilling in depressed economic conditions to invest in new equipment or expand military pay. Amid the breakdown in French civil-military relations in the 1930s, Weygand was neutral and "never indicated any support for any such projects" to replace the republican system with a military dictatorship. He was, however, able to successfully lobby for creation of a light mechanised division as well as creation of a seven motorised infantry division in the early 1930s; he was also able to lobby for extension of conscripts' service to two years in 1934.

Retirement and return to the Levant

From 1931 he had been admitted to theAcadémie Française

An academy (Attic Greek: Ἀκαδήμεια; Koine Greek Ἀκαδημία) is an institution of tertiary education. The name traces back to Plato's school of philosophy, founded approximately 386 BC at Akademia, a sanctuary of Athena, the go ...

as Seat 35 in place of Joffre, deceased. On his retirement he was retained on the active list at full pay but was unassigned. This allowed him leave to travel: as an administrator of the Suez Canal Company

Suez (, , , ) is a seaport city with a population of about 800,000 in north-eastern Egypt, located on the north coast of the Gulf of Suez on the Red Sea, near the southern terminus of the Suez Canal. It is the capital and largest city of the ...

he visited Egypt and the court of Fuad I

Fuad I ( ''Fu’ād al-Awwal''; 26 March 1868 – 28 April 1936) was the Sultan and later King of Egypt and the Sudan. The ninth ruler of Egypt and Sudan from the Muhammad Ali dynasty, he became Sultan in 1917, succeeding his elder brother Hus ...

; he travelled also to eastern Europe and Britain on military matters. He spent some of this time writing articles in military journals on the state of the army, arguing that the now-superior German army could be held back by a well-equipped defence before motorised units would be eventually able to start a counteroffensive. However, he disagreed with Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French general and statesman who led the Free France, Free French Forces against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Government of the French Re ...

's arguments for a centralised armour force on the grounds that it would undermine troop cohesion and greatly stress French industrial capacity. While he never criticised his successor Gamelin, he published a short book ''La france, est-elle défendue?'' 'France, is it defended?''in 1937 warning of German military superiority and the possibility of a sudden attack. His thoughts in the years before Hitler's invasion of Poland saw him again press for further material rearmament even as his views on the need for a fully-professional army softened; he also wrote a book called ''Histoire de l'armée française'' in 1938 arguing against the prevailing defensive strategy and expressing fear over the reliability of colonial troops in metropolitan France.

Weygand was recalled for active service in August 1939 by Édouard Daladier

Édouard Daladier (; 18 June 1884 – 10 October 1970) was a French Radical Party (France), Radical-Socialist (centre-left) politician, who was the Prime Minister of France in 1933, 1934 and again from 1938 to 1940. he signed the Munich Agreeme ...

's government and appointed again to the Levant, resigning his position in the Suez Canal Company. The government may have sought to keep him away from Gamelin's command. Regardless, he was officially dispatched to negotiate with Turkey, Greece, and Romania for French security interests. He also was tasked with inspecting and training the colonial garrisons.

Second World War

Immediately after the German army arrived in France, Weygand feared a Paris Commune-like event might happen.

Weygand's service during the Second World War is controversial and debated. His reputation came under substantial criticism from

Immediately after the German army arrived in France, Weygand feared a Paris Commune-like event might happen.

Weygand's service during the Second World War is controversial and debated. His reputation came under substantial criticism from Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French general and statesman who led the Free France, Free French Forces against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Government of the French Re ...

and his allies after the war. Much of this criticism related to claims that Weygand was negligent in rearming France while head of the army, was defeatist or incompetent during the Battle of France

The Battle of France (; 10 May – 25 June 1940), also known as the Western Campaign (), the French Campaign (, ) and the Fall of France, during the Second World War was the Nazi Germany, German invasion of the Low Countries (Belgium, Luxembour ...

thereby leading to France's defeat in 1940, and was a German collaborator in the Vichy regime

Vichy France (; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was a French rump state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II, established as a result of the French capitulation after the defeat against ...

.

Recall to service

By late May 1940 the military disaster in France after the German invasion was such that the Supreme Commander—and political neutral—Maurice Gamelin

Maurice Gustave Gamelin (; 20 September 1872 – 18 April 1958) was a French general. He is remembered for his disastrous command (until 17 May 1940) of the French military during the Battle of France in World War II and his steadfast defence of ...

, was dismissed, and Weygand—a figurehead of the right—was recalled from Syria to replace him.

Weygand arrived on 17 May and started by cancelling the flank counter-offensive ordered by Gamelin, to cut off the enemy armoured columns which had punched through the French front at the Ardennes. Thus he lost two crucial days before finally adopting the solution, however obvious, of his predecessor. But it was by then a failed manoeuvre, because during the 48 lost hours, the German Army

The German Army (, 'army') is the land component of the armed forces of Federal Republic of Germany, Germany. The present-day German Army was founded in 1955 as part of the newly formed West German together with the German Navy, ''Marine'' (G ...

infantry had caught up behind their tanks in the breakthrough and had consolidated their gains.

Weygand then oversaw the creation of the Weygand Line, an early application of the hedgehog tactic; however, by this point the situation was untenable, with most of the Allied forces trapped in Belgium. Weygand complained that he had been summoned two weeks too late to halt the invasion.

Armistice

On 5 June the German second offensive (''Fall Rot

''Fall Rot'' (Case Red) was the plan for a German military operation after the success of (Case Yellow), the Battle of France, an invasion of the Benelux countries and northern France. The Allied armies had been defeated and pushed back in t ...

'') began. On 8 June Weygand was visited by de Gaulle, newly appointed to the government as Under-Secretary for War. According to de Gaulle's memoirs Weygand believed it was "the end" and gave a "despairing laugh" when de Gaulle suggested fighting on. He believed that after France was defeated Britain would also soon sue for peace, and hoped that after an armistice the Germans would allow him to retain enough of a French Army to "maintain order" in France. Weygand later disputed the accuracy of de Gaulle's account of this conversation, and remarked on its similarity to a dialogue by Pierre Corneille

Pierre Corneille (; ; 6 June 1606 – 1 October 1684) was a French tragedian. He is generally considered one of the three great 17th-century French dramatists, along with Molière and Racine.

As a young man, he earned the valuable patronage ...

. De Gaulle's biographer Jean Lacouture suggests that de Gaulle's account is consistent with other evidence of Weygand's beliefs at the time and is therefore, allowing perhaps for a little literary embellishment, broadly plausible.

Fascist Italy

Fascist Italy () is a term which is used in historiography to describe the Kingdom of Italy between 1922 and 1943, when Benito Mussolini and the National Fascist Party controlled the country, transforming it into a totalitarian dictatorship. Th ...

entered the war and invaded France on 10 June. That day Weygand barged into the office of Prime Minister Paul Reynaud and demanded an armistice. Weygand was present at the Anglo-French Conference at the Château du Muguet at Briare on 11 June, at which the option was discussed of continuing the French war effort from Brittany

Brittany ( ) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the north-west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica in Roman Gaul. It became an Kingdom of Brittany, independent kingdom and then a Duch ...

or French North Africa

French North Africa (, sometimes abbreviated to ANF) is a term often applied to the three territories that were controlled by France in the North African Maghreb during the colonial era, namely Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia. In contrast to French ...

. The transcript shows Weygand to have been somewhat less defeatist than de Gaulle's memoirs would suggest. At the Cabinet meeting on the evening of 13 June, after another Anglo-French conference at Tours, Marshal Pétain, Deputy Prime Minister, strongly supported Weygand's demand for an armistice. On June 14 Weygand warned General Alan Brooke

Field Marshal Alan Francis Brooke, 1st Viscount Alanbrooke (23 July 1883 – 17 June 1963), was a senior officer of the British Army. He was Chief of the Imperial General Staff (CIGS), the professional head of the British Army, during the Secon ...

, the new commander-in-chief of the British forces in France, that the French Army was collapsing and incapable of fighting further, leading him to evacuate the final British Expeditionary Force contingents remaining on the Western Front.

The French government moved to Bordeaux

Bordeaux ( ; ; Gascon language, Gascon ; ) is a city on the river Garonne in the Gironde Departments of France, department, southwestern France. A port city, it is the capital of the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region, as well as the Prefectures in F ...

on 14 June. At Cabinet on 15 June Reynaud urged that they should follow the Dutch example, that the Army should lay down its arms so that the fight could be continued from abroad. Pétain was sympathetic, but he was sent to speak to Weygand (who was waiting outside, as he was not a member of the Cabinet). After no more than fifteen minutes Weygand persuaded him that this would be a shameful surrender. Camille Chautemps

Camille Chautemps (; 1 February 1885 – 1 July 1963) was a French Radical politician of the Third Republic, three times President of the Council of Ministers (Prime Minister).

He was the father-in-law of U.S. politician and statesman Howar ...

then proposed a compromise proposal, that the Germans be approached about possible armistice terms. The Cabinet voted 13–6 for the Chautemps proposal.

After Reynaud's resignation as Prime Minister on 16 June, President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

Albert Lebrun

Albert François Lebrun (; 29 August 1871 – 6 March 1950) was a French politician who served as President of France from 1932 to 1940. He was the last president of the Third Republic. He was a member of the centre-right Democratic Republica ...

felt he had little choice but to appoint Pétain, who already had a ministerial team ready, as prime minister. Weygand joined the new government as Minister for Defence, and was briefly able to veto the appointment of Pierre Laval

Pierre Jean Marie Laval (; 28 June 1883 – 15 October 1945) was a French politician. He served as Prime Minister of France three times: 1931–1932 and 1935–1936 during the Third Republic (France), Third Republic, and 1942–1944 during Vich ...

as minister of foreign affairs.

Vichy regime

TheVichy regime

Vichy France (; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was a French rump state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II, established as a result of the French capitulation after the defeat against ...

was set up in July 1940. Weygand continued to serve in Pétain's cabinet as Minister for National Defence until September 1940. He was then appointed Delegate-General in French North Africa.

In North Africa, he persuaded young officers, tempted to join the French Resistance

The French Resistance ( ) was a collection of groups that fought the German military administration in occupied France during World War II, Nazi occupation and the Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy#France, collaborationist Vic ...

against the German occupation, to go along with the armistice for the present, by letting them hope for a later resumption of combat. With the complicity of Admiral Jean-Marie Charles Abrial, he deported opponents of Vichy to concentration camp

A concentration camp is a prison or other facility used for the internment of political prisoners or politically targeted demographics, such as members of national or ethnic minority groups, on the grounds of national security, or for exploitati ...

s in Southern Algeria

Algeria, officially the People's Democratic Republic of Algeria, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It is bordered to Algeria–Tunisia border, the northeast by Tunisia; to Algeria–Libya border, the east by Libya; to Alger ...

and Morocco

Morocco, officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It has coastlines on the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to Algeria–Morocc ...

. Those imprisoned included Gaullists, Freemasons

Freemasonry (sometimes spelled Free-Masonry) consists of fraternal groups that trace their origins to the medieval guilds of stonemasons. Freemasonry is the oldest secular fraternity in the world and among the oldest still-existing organizati ...

, and Jews

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

, and also communists

Communism () is a sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology within the socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a socioeconomic order centered on common ownership of the means of production, d ...

, despite their obedience at the time to the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

's orders not to support the resistance. He also arrested the foreign volunteers of the '' Légion Etrangère'', foreign refugees who were in France legally but were without employment, and others. He applied Vichy anti-Jewish legislation very harshly. With the complicity of the ''Recteur'' (University chancellor) Georges Hardy, Weygand instituted, on his own authority, by a mere ''"note de service"'' (n°343QJ of 30 September 1941), a school ''numerus clausus'' (quota). This drove out most Jewish students from the colleges and the primary schools, including children aged 5 to 11. Weygand did this without any order from Pétain, "by analogy", he said, "to the law about Higher Education".

Weygand acquired a reputation as an opponent of collaboration when he protested in Vichy against the Paris Protocols of 28 May 1941, signed by Admiral François Darlan. These agreements authorized the Axis powers

The Axis powers, originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis and also Rome–Berlin–Tokyo Axis, was the military coalition which initiated World War II and fought against the Allies of World War II, Allies. Its principal members were Nazi Ge ...

to establish bases in French colonies: at Aleppo

Aleppo is a city in Syria, which serves as the capital of the Aleppo Governorate, the most populous Governorates of Syria, governorate of Syria. With an estimated population of 2,098,000 residents it is Syria's largest city by urban area, and ...

, Syria

Syria, officially the Syrian Arab Republic, is a country in West Asia located in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Levant. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the west, Turkey to Syria–Turkey border, the north, Iraq to Iraq–Syria border, t ...

; Bizerte

Bizerte (, ) is the capital and largest city of Bizerte Governorate in northern Tunisia. It is the List of northernmost items, northernmost city in Africa, located north of the capital Tunis. It is also known as the last town to remain under Fr ...

, Tunisia

Tunisia, officially the Republic of Tunisia, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It is bordered by Algeria to the west and southwest, Libya to the southeast, and the Mediterranean Sea to the north and east. Tunisia also shares m ...

; and Dakar

Dakar ( ; ; ) is the capital city, capital and List of cities in Senegal, largest city of Senegal. The Departments of Senegal, department of Dakar has a population of 1,278,469, and the population of the Dakar metropolitan area was at 4.0 mill ...

, Senegal

Senegal, officially the Republic of Senegal, is the westernmost country in West Africa, situated on the Atlantic Ocean coastline. It borders Mauritania to Mauritania–Senegal border, the north, Mali to Mali–Senegal border, the east, Guinea t ...

. The Protocols also envisaged extensive French military collaboration with Axis forces in the event of Allied attacks against such bases. Weygand remained outspoken in his criticism of Germany.

Weygand opposed Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the German Army (1935–1945), ''Heer'' (army), the ''Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmac ...

bases in French territory not to help the Allies or even to keep France neutral, but rather to preserve the integrity of the French Empire and maintain prestige in the eyes of the natives. Weygand apparently favoured limited collaboration with Germany. The Weygand General Delegation (4th Office) delivered military equipment to the Panzer Armee Afrika: 1,200 French trucks and other Armistice Army vehicles (Dankworth contract of 1941), and also heavy artillery with 1,000 shells per gun. However, Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

demanded full unconditional collaboration and pressured the Vichy government

Vichy France (; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was a French rump state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II, established as a result of the French capitulation after the defeat against ...

to dismiss Weygand in November 1941 and recall him from North Africa. A year later, in November 1942, following the Allied invasion of North Africa, the Germans arrested Weygand. He remained in custody in Germany and then in the Itter Castle in North Tyrol with General Gamelin and a few other French Third Republic

The French Third Republic (, sometimes written as ) was the system of government adopted in France from 4 September 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed during the Franco-Prussian War, until 10 July 1940, after the Fall of France durin ...

personalities until May 1945. He was liberated by United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary Land warfare, land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of th ...

troops after the Battle of Castle Itter.

Last years

After returning to France, Weygand was held as a collaborator at theVal-de-Grâce

The Val-de-Grâce (; Hôpital d'instruction des armées du Val-de-Grâce or HIA Val-de-Grâce) was a military hospital located at 74 boulevard de Port-Royal in the 5th arrondissement of Paris, France. It was closed as a hospital in 2016.

History

...

but was released in May 1946 and cleared in 1948. He died on 28 January 1965 in Paris at the age of 98. He had married Marie-Renée-Joséphine de Forsanz (1876-1961), the daughter of Brigadier General Raoul de Forsanz (1845-1914), on 12 November 1900. They had two sons, Édouard (1901-1987) and Jacques (1905-1970).

Beirut still holds his name on one of its major streets, Rue Weygand

Rue Weygand is a street in Beirut's Beirut Central District, Central Business District. Originally, the street was named Rue Nouvelle as it was a new thoroughfare constructed as part of a modernization plan in 1915. Upon its completion, the s ...

.

Decorations

*France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

:

** Légion d'honneur

The National Order of the Legion of Honour ( ), formerly the Imperial Order of the Legion of Honour (), is the highest and most prestigious French national order of merit, both military and Civil society, civil. Currently consisting of five cl ...

*** Knight (10 July 191?)

*** Officer (10 December 1914)

*** Commander (28 December 1918)

*** Grand Officer (1 September 1920)

*** Grand Cross (6 December 1924)

** Médaille militaire

The ''Médaille militaire'' (, "Military Medal") is a military decoration of the French Republic for other ranks for meritorious service and acts of bravery in action against an enemy force. It is the third highest award of the French Republic, ...

(8 July 1930)

** Croix de Guerre 1914–1918

Croix (French for "cross") may refer to:

Belgium

* Croix-lez-Rouveroy, a village in municipality of Estinnes in the province of Hainaut

France

* Croix, Nord, in the Nord department

* Croix, Territoire de Belfort, in the Territoire de Belfort depa ...

with 3 palms

** Croix de Guerre 1939–1945

Croix (French for "cross") may refer to:

Belgium

* Croix-lez-Rouveroy, a village in municipality of Estinnes in the province of Hainaut

France

* Croix, Nord, in the Nord department

* Croix, Territoire de Belfort, in the Territoire de Belfort d ...

with 2 palms

** Croix de guerre des théâtres d'opérations extérieures

The (; "War Cross for Foreign Operational Theatres"), also called the for short, is a French military award denoting citations earned in combat in foreign countries. The Armistice of November 11, 1918 ended the war between France and Germa ...

with 1 palm

** Médaille Interalliée de la Victoire

** Médaille Commémorative de la Grande Guerre

* :

** Commander of the Order of the Crown

** Croix de guerre

The (, ''Cross of War'') is a military decoration of France. It was first created in 1915 and consists of a square-cross medal on two crossed swords, hanging from a ribbon with various degree pins. The decoration was first awarded during World ...

* : Distinguished Service Medal

* : Grand Cross of the Ouissam Alaouite Chérifien

* :

** Companion of the Order of the Bath

Companion may refer to:

Relationships Currently

* Any of several interpersonal relationships such as friend or acquaintance

* A domestic partner, akin to a spouse

* Sober companion, an addiction treatment coach

* Companion (caregiving), a caregi ...

** Knight Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George

The Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George is a British order of chivalry founded on 28 April 1818 by George, Prince of Wales (the future King George IV), while he was acting as prince regent for his father, King George III ...

* : Grand Cross of the Order of the Sword (1939)

* : Order of Lāčplēsis

The Order of Lāčplēsis (also Lāčplēsis Military Order, ), the first and the highest Latvian military award, was established in 1919 on the initiative of Jānis Balodis, the Commander of the Latvian Army during the Latvian War of Independ ...

, 2nd class.

* : Order of the White Eagle

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

Memoirs

* * * *Polish period

* * *Second World War

* * * * * * * * *External links

*Generals of World War II

{{DEFAULTSORT:Weygand, Maxime 1867 births 1965 deaths Chiefs of the Staff of the French Army Military personnel from Brussels French generals 19th-century French military personnel French Army generals of World War I French Army generals of World War II Generalissimos Jewish French history Members of the Académie Française Lycée Louis-le-Grand alumni École Spéciale Militaire de Saint-Cyr alumni High commissioners of the Levant Order of the Francisque recipients Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour Commanders of the Order of the Crown (Belgium) Recipients of the Order of Lāčplēsis, 2nd class Recipients of the Virtuti Militari Recipients of the Croix de Guerre 1939–1945 (France) Recipients of the Croix de guerre des théâtres d'opérations extérieures Recipients of the Croix de guerre (Belgium) Recipients of the Distinguished Service Medal (US Army) Honorary companions of the Order of the Bath Honorary Knights Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George French anti-communists People of Vichy France French collaborators with Nazi Germany Ministers of war and national defence of France 20th-century French military personnel Foreign recipients of the Distinguished Service Medal (United States) Governors general of Algeria Belgian emigrants to France Prisoners and detainees of France French people imprisoned in Germany