Max Stephan on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Max Stephan (July 10, 1892 – January 13, 1952) was a German-born American citizen convicted of treason for aiding Peter Krug, a German pilot who had escaped from a

On August 6, 1942, Judge Tuttle sentenced Stephan to be hanged by the neck until dead, setting an execution date of November 13, 1942. In explaining his decision, Tuttle stated:

In his comments from the bench, Judge Tuttle also reported that he had learned that the Stephans obtained their American citizenship by lying about residing in Detroit when they had actually been living in Windsor, Ontario (across the river in Canada) and operating a saloon and bed-house for unmarried couples. Tuttle also criticized Stephan's wife for disloyal statements and urged that proceedings be launched to revoke her citizenship and to have her interned. Tuttle further offered his belief that there was a well-established "underground railway" of German loyalists to aid escaped prisoners with Stephan as an essential link.

Stephan's wife, Agnes, collapsed outside the courtroom when the verdict was explained by a bailiff. On his return to prison from the sentencing, Stephan reportedly told a deputy U.S. marshall who was guarding him, "I'll bet all the tea in China I won't hang."

On August 6, 1942, Judge Tuttle sentenced Stephan to be hanged by the neck until dead, setting an execution date of November 13, 1942. In explaining his decision, Tuttle stated:

In his comments from the bench, Judge Tuttle also reported that he had learned that the Stephans obtained their American citizenship by lying about residing in Detroit when they had actually been living in Windsor, Ontario (across the river in Canada) and operating a saloon and bed-house for unmarried couples. Tuttle also criticized Stephan's wife for disloyal statements and urged that proceedings be launched to revoke her citizenship and to have her interned. Tuttle further offered his belief that there was a well-established "underground railway" of German loyalists to aid escaped prisoners with Stephan as an essential link.

Stephan's wife, Agnes, collapsed outside the courtroom when the verdict was explained by a bailiff. On his return to prison from the sentencing, Stephan reportedly told a deputy U.S. marshall who was guarding him, "I'll bet all the tea in China I won't hang."

prisoner of war camp

A prisoner-of-war camp (often abbreviated as POW camp) is a site for the containment of enemy fighters captured by a belligerent power in time of war.

There are significant differences among POW camps, internment camps, and military prisons. ...

in Canada. Stephan was initially sentenced to death by hanging. However, President Franklin D. Roosevelt commuted his sentence to life imprisonment just nine hours before he was scheduled to be executed. Stephan died in prison in 1952.

Stephan became the first person to be convicted of federal treason charges in a civilian court since the 1790s’ Whiskey Rebellion.

Background

Germany

Stephan's biographical details were chronicled at length in the August 1942 court judgment sentencing him to death. Except where other sourcing is noted, the following summary is based on the details set forth in that judgment. Stephan was born in Cologne, Germany, in 1892. He entered theImperial German Army

The Imperial German Army (1871–1919), officially referred to as the German Army (german: Deutsches Heer), was the unified ground and air force of the German Empire. It was established in 1871 with the political unification of Germany under the l ...

at age 20 for two years of compulsory military service. When World War I began, he held the rank of lance corporal ('' Gefreiter'') and was promoted to sergeant. He was injured in battle in 1915. Out of 120 men in his infantry unit, only six survived.

After recovering from his injuries, Stephan served until 1917 as a guard at a military prison camp for deserters. During the final year of the war, he was assigned to a military post office where he was tasked with reading and censoring soldiers' mail.

After the war, Stephan worked as a police officer in Cologne. He was married in 1922. In 1924, he completed 12 years of national service (six in the army, six with the police) and became eligible for a reward of 6,000 German marks. He then retired from the police service and used the reward money to open a saloon in Cologne.

Windsor, Ontario

In 1928, Stephan left Germany for Canada, arriving in Quebec and moving three months later to Windsor, Ontario. In a letter to the court, Stephan described his emigration from Germany: "In 1928, business was getting bad in Germany so that I decided to sell my saloon there and move to America to start one. Oct. 1928 I moved to Windsor, Canada. In November 1928 I started to work for General Motors, Windsor, as a repairman, till about July 1929. I did my work to their satisfaction and quit to start a restaurant." Stephan's wife, Agnes, joined him in Windsor in 1929. They operated a restaurant at 620 Langlois Street in Windsor. According to the judgment written by Judge Tuttle, Stephan also sold "moonshine liquor" and operated "a disreputable house for the accommodation of unmarried couples." Stephan and his wife later relocated their restaurant business to the corner of Sandwich and Windsor Streets in Windsor. Judge Tuttle found that Stephan also sold liquor and operated a "disreputable bedhouse" at the second location.Detroit

In 1933, Stephan and his wife moved to Detroit. He purchased a restaurant at 7209 E. Jefferson Avenue in Detroit, an area with a large concentration of recent German immigrants that became known as "Sauerkraut Row". Stephan and his wife applied for and received American citizenship in 1935. Judge Tuttle concluded that, in their citizenship applications, both Stephan and his wife had misrepresented the length of their residence in the United States. Stephan contended that he was going back and forth to Detroit and felt at home there. From 1935 to 1941, Stephan's restaurant was known as "German Restaurant". (The word "German" was crudely painted over following Germany's declaration of war against the United States in December 1941.) Stephan expanded the restaurant in 1936 by adding a meeting hall. The '' Detroit Free Press'' published a story in August 1939 exposing the restaurant as a regular meeting place for theGerman American Bund

The German American Bund, or the German American Federation (german: Amerikadeutscher Bund; Amerikadeutscher Volksbund, AV), was a German-American Nazi organization which was established in 1936 as a successor to the Friends of New Germany (FoN ...

, an organization promoting a favorable view of Nazi Germany. At the time, Stephan denied any connection to the Bund and stated that he rented the restaurant's hall, which had seating for 150 persons, to several German societies. Stephan claimed that the restaurant's meeting hall was used by numerous organizations for banquets, weddings, birthday parties and other events. He denied being a member of the Bund and told the Bund there was to be "no uniforms, no swastika and no heil in my place, otherwise, no hall." He told the ''Free Press'': "There is no fuss or noise. If there were, I wouldn't let them meet here any longer. The men do not wear uniforms, and there is never any drilling."

Stephan also claimed that, during the time he lived in the United States, he never communicated with anyone in Germany and completely cut off his connections with Germany. As proof of his loyalty, Stephan noted that, after the war with Germany began, he purchased two $50 War Bonds on December 17, 1941.

Krug affair

Escape from Bowmanville

Lieutenant Hans Peter Krug was a bomber pilot in Germany's Luftwaffe. During the Battle of Britain, he was shot down over the English Channel in 1941 during a bombing mission. He was captured and sent to theBowmanville POW camp

The Bowmanville POW camp also known as ''Camp 30'' was a Canadian-run POW camp for German soldiers during World War II located in the community of Bowmanville, Ontario in Clarington, Ontario, Canada (2020 Lambs Road). In September 2013, the camp ...

, located east of Toronto, Canada.

Krug escaped from Bowmanville on April 16, 1942. He made his way to Toronto where he was stopped by military police. He satisfied their suspicion by showing them a forged document identifying him as "Jean Etiat", a carpenter

Carpentry is a skilled trade and a craft in which the primary work performed is the cutting, shaping and installation of building materials during the construction of buildings, Shipbuilding, ships, timber bridges, concrete formwork, etc. ...

on the crew of the French ocean liner SS ''Normandie''. The police introduced him to a Catholic priest, Father McGrath, who bought him a bus ticket to Windsor, Ontario. From Windsor, he rowed across the Detroit River in a stolen rowboat, arriving on Detroit's Belle Isle at approximately 9 p.m. He spent the night of April 17 sleeping in a doorway and inside a vegetable cart.

April 18–19, 1942: Stephan assists Krug

On the morning of Saturday, April 18, 1942, Krug went to the home of Margareta Bertelmann, a German citizen who had sent Red Cross packages of cookies and clothing to the German prisoners of war in Bowmanville. Krug had memorized her address from the packages she sent. Unsure how she could help Krug, Bertelmann called Stephan whom she knew from his restaurant. Stephan arrived a short time later and told Krug he didn't have a chance and that he should turn himself in. Krug refused to turn himself in, and Stephan drove Krug to his restaurant. Stephan fed Krug, and they later visited several bars. Stephan then took Krug to a prostitute, as it was the eve of Krug's 22nd birthday. Stephan also took Krug to a shop operated by Theodore Donay, a German veteran of World War I. Donay gave Krug twenty dollars. A store clerk and fellow German immigrant, Dietrick Rinterlen, reported the incident to theFederal Bureau of Investigation

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic intelligence and security service of the United States and its principal federal law enforcement agency. Operating under the jurisdiction of the United States Department of Justice, t ...

(FBI).

After showing Krug "a good time" for his birthday, Stephan sent Krug to the Field Hotel to sleep.

On the night of April 18, William J. Nagel visited Stephan's restaurant. Nagel was a prominent member of Detroit's German-American community; he had served as Detroit postmaster (1913–22), Detroit city controller (1923–24), managing director of the Michigan Liquor Control Commission (1933), and president of the Grosse Pointe Savings Bank. Stephan claimed that he had told Nagel about Krug and sought advice from Nagel. According to Stephan, Nagel advised that the war was over for Krug, that it was impossible for Krug to leave the country, and that if Nagel had the time he would personally drive him to Chicago to enjoy a couple days more of freedom. As Nagel was busy, he advised Stephan to take Krug to the bus station where the first bus for Chicago left at 10 a.m. Nagel advised that the bus was preferable to the train. According to Stephan, Nagel also gave him three dollars for Krug, a sum Stephan used to purchase Krug's bus ticket. When questioned by the FBI, Nagel denied having spoken to Stephan or knowing anything about Krug.

On Sunday morning, April 19, Stephan picked up Krug from the Field Hotel and drove him to the bus station, where he bought Krug a bus ticket to Chicago.

Arrest of Stephan and capture of Krug

Following the tip from Rinterlen, Stephan was arrested by FBI agents on Monday morning, April 20, 1942. In the days following his arrest, Stephan granted interviews to reporters. In a jailhouse interview with James Melton of the ''Detroit Times'', Stephan reportedly admitted that he was aware that Krug sought to escape in order to return to the fight and help Germany win the war. Stephan was quoted as saying:All he wants to do is to get a stick in his hands again. And he'll do it, too. . . . Krug plans to go to South America and get on a Spanish boat for Germany. . . . He says the Germans will win the war next fall, so he has to get back in the fight fast.Following Stephan's arrest a manhunt was launched to capture Krug before he could reach neutral territory in Mexico. Krug was arrested on May 1, 1942, in San Antonio, Texas. Krug was returned to Detroit as a witness in the Stephan case.

Prosecution of Stephan

Push for a treason charge

Stephan was initially charged with harboring an alien fugitive, butJohn C. Lehr

John Camillus Lehr (November 18, 1878 – February 17, 1958) was a politician from the U.S. state of Michigan.

Lehr was born in Monroe, Michigan and attended St. Mary's private school and graduated from Monroe High School in 1897. He graduated ...

, the United States Attorney for the Eastern District of Michigan, sought permission to charge Stephan with treason. The local press also advocated for the higher charge, the ''Detroit Free Press'' stating in an editorial:

There is but one charge that can be sensibly made against this man and that is treason. . . . azi sympathizers and Hitler toolsare laughing at us! Stephan is charged with the panty-waist accusation that he 'harbored' an alien. . . . Yes, this is a free country; but freedom does not include treason according to the Constitution – contrary to a lot of soft-headed parlor-pink theorizing. We are at war.Through mid-May, the U.S. Attorney General had refused to charge Stephan with treason. The ''Detroit Free Press'' repeated its cry for the heightened charge: "The police authorities, on the other hand, say that what Detroit needs more than anything else just now, is a trial for treason which will show that the Government means business. This alone, they say, would do more to discourage friends of the Axis powers here – and they figure Detroit alone has several thousand – than anything else." The ''Detroit Times'' described Stephan as "an insignificant pawn" and called his specific act to be "negligible in consequence." Nevertheless, the ''Times'' urged that Stephan be given "short shrift" in order to demonstrate to Nazi and Japanese followers that Americans are not "softies and dilettantes in the war business" and to deliver "a severe blow to the entire fraternity" of "phoney naturalized citizens of German birth." On June 2, 1942, a federal grand jury was impaneled in Detroit to consider treason charges against Stephan. The grand jury heard from 17 witnesses, including Krug. On June 17, the grand jury indicted Stephan for treason. The indictment charged Stephan with 11 overt acts of treason as follows: # Driving to Margareta Bertelmann's home for the purpose of taking Krug under his protection; # Obtaining money from Bertelmann for Krug's benefit; # Escorting Krug from Bertelmann's home to his restaurant; # Providing Krug with food, drink, personal effects and clothing; # Making inquiry regarding Detroit-Chicago train schedules with intent to aid Krug; # Escorting Krug to Haller's Cafe, 1407 Randolph Street, and buying drinks for Krug and concealing Krug's identity by introducing him as "one of the Meyer boys"; # Taking Krug to the Progressive Club, 3003 Elmwood Avenue, buying him drinks, and introducing him as a friend from Milwaukee; # Taking Krug to Theodore Donay's business, 3152 Gratiot Avenue, and obtaining money which was given to Krug; # Escorting Krug to a disorderly house; # Taking Krug back to Stephan's restaurant, feeding him, and introducing him as a friend from Milwaukee; and # Taking Krug to the bus terminal and buying him a ticket to Chicago, the start of a journey intended to return Krug to active status with the German army. Stephan was arraigned on June 20, and the trial was set to occur nine days later.

Trial

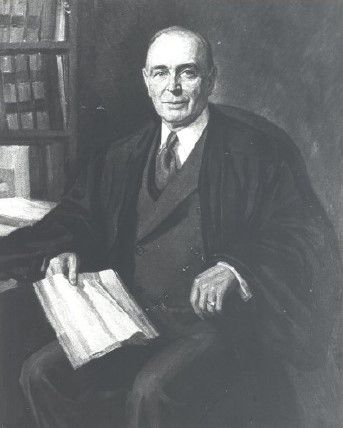

On June 29, 1942, Stephan's trial began in the courtroom of U.S. District Court JudgeArthur J. Tuttle

Arthur J. Tuttle (November 8, 1868 – December 2, 1944) was a United States federal judge, United States district judge of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Michigan.

Education and career

Born in Leslie, Michigan, Les ...

, a federal judge since 1912. It was the first treason trial to be held in the United States since World War I.

Krug as the star witness

The trial began with testimony from Krug. Appearing in a dress uniform with gold epaulets and Nazi Luftwaffe wings, Krug was escorted into court by six FBI agents and a Canadian army officer. Krug was described as smiling, "debonair and obviously enjoying the spotlight." As a prisoner of war, Krug was under no obligation to testify, but agreed to do so voluntarily. He described Stephan's acts of kindness, including buying him a bag, a necktie, and a billfold and a "birthday trip" through Detroit that included multiple stops for food and drinks. After testifying at length about Stephan's acts, Krug realized on questioning from the defense that his testimony might be intended to harm Stephan. When questioning then returned to the prosecutor, Krug "suddenly balked" and demanded to know whether his testimony was to be used against Stephan and asked the judge to be relieved from further questioning. Krug said, "It was not my intention to testify against him. I was told by the FBI to clear things up. I never wanted to testify against the man who helped me. The FBI said it was just a statement of facts already known." In response to Krug's inquiry, Judge Tuttle folded his arms and shook his head, saying, "I can't help who you are testifying against. All I can do is try to get the truth and all I can say is to tell the truth." The damage already having been done, the prosecutor excused Krug without further questions. As he left the courtroom, Krug delivered a Nazi salute and "clicked his heels together in best Nazi fashion." The following day, Jack Weeks of the ''Detroit Free Press'' taunted Krug for so naively betraying Stephan, describing Krug as an example of Hitler's so-called "race" and as a "creature from another world." Another writer noted that Krug's presence as "the swashbuckling luftwaffe oberleutnant" dominated the proceeding while Stephan, "the pudgy little tavern keeper" on trial for his life, was "playing a minor supporting role" in his own trial.Additional evidence of overt acts

Under the U.S. Constitution, conviction for treason requires "the testimony of two Witnesses to the same overt Act, or on Confession in open court." In an attempt to meet its constitutional burden, on June 30 and July 1 the government called other witnesses to confirm Stephan's overt acts. These witnesses included: * William Lens testified to seeing Stephan and Krug together and that Stephan asked Lens about trains to Chicago. * John W. McGuire testified to seeing Stephan and Krug together at a Detroit bar. * August Haller, a tavern owner, testified that Stephan took Krug to his tavern and introduced him as "one of the Meyers boys". * Carl Erhardt, a restaurant owner, testified that Stephan and Krug visited his restaurant during Krug's birthday tour, that Stephan introduced the young man as a friend from Milwaukee, and that Stephan asked Erhardt to sit with them. Erhardt did not remember details of the conversation, noting that some of it was in German. * Eva Erhardt, wife of Carl, confirmed her husband's testimony. * Margareta Bertelmann, the woman on whose doorstep Krug had arrived, testified that she introduced Krug to Stephan and that the two men then left her home together. Bertelmann also testified that Stephan had tried to discourage Krug from fleeing, testifying that Stephan had stated: "Why don't you give yourself up? You haven't a chance." The government also presented testimony by FBI agent John Bugas that Stephan had admitted following his arrest to having arranged Krug's shelter, purchased him gifts and a bus ticket, and taken him to the bus. No indication appears in the press accounts as to whether Stephan's lawyer objected to Bugas' testimony on grounds that the Constitution provides for conviction of treason based on a confession only if the confession is made "in open court". The use and weight to be given to such out-of-court confessions in treason trials was later the subject of two United States Supreme Court decisions. ''See Cramer v. United States'', 325 U.S. 1 (1945) ("Another class of evidence consists of admissions to agents of the Federal Bureau of Investigation. They are, of course, not 'confession in open court.' The Government does not contend, and could not well contend, that admissions made out of court, if otherwise admissible, can supply a deficiency in proof of the overt act itself."); ''Haupt v. United States'', 330 U.S. 631 (1947) (the constitutional requirement of two witnesses to the same overt act or confession in open court does not operate to exclude confessions or admissions made out of court, where a legal basis for the conviction has been laid by the testimony of two witnesses of which such confessions or admissions are merely corroborative).Intent to aid Germany

The crime of treason required proof that Stephan acted with an intent to aid Germany. Stephan's defense counsel focused on this issue, arguing that Stephan simply intended to help a young German in need rather than having an intent to assist Germany in its war efforts. Stephan's trial attorney, Verne Amberson, characterized Stephan's actions as "wrong and silly", but argued there was no intent to aid the German government. In his closing argument to the jury, Amberson compared Stephan to theGood Samaritan

In most contexts, the concept of good denotes the conduct that should be preferred when posed with a choice between possible actions. Good is generally considered to be the opposite of evil and is of interest in the study of ethics, morality, ph ...

: "The Samaritan was an enemy of the race from which the wounded traveler came. If the FBI had been operating in Palestine then they would have had the Good Samaritan in the high court at Jerusalem, charged with treason."

The prosecutor, John Lehr, countered Amberson's argument:

Was Krug playing hockey? Was poor Max—dumb Max—good, generous Max, only helping this boy get home to his mother and father? Remember who and what Krug was. He was a member of the German Air Corps since 1938, an officer in Hitler's Army. He was shot down over England while piloting a plane to bomb innocent men and women. His purpose in coming to Detroit was to get back to Germany, get into a bomber and bomb, if he could, the United States. It was Stephan who tried to help him to do this and that is why he is a traitor—a black-hearted traitor.

Guilty verdict

The jury deliberated for an hour and twenty-three minutes, finding Stephan guilty of treason at 5:39 p.m. on July 2. The verdict was announced by the jury foreman, Jerry H. Armstrong, ofEmmett, Michigan

Emmett is a village in St. Clair County of the U.S. state of Michigan. The population was 269 at the 2010 census. The village is located within Emmett Township.

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the village has a total ar ...

. According to jurors, the first vote was 11 to 1 for conviction with one juror questioning Stephan's intent to aid the German government. On a second vote, the jury of six men and six women (several of German ancestry) was unanimous. Juror Marion B. Williams explained that the only discussion turned on whether Stephan intended to help the German government, saying "We decided that he had plenty of time to realize what he was doing and that he intended to help Germany." The full jury posed for a group portrait outside the courtroom following the verdict.

With the conviction, Stephan became the first person convicted of treason through a trial in a federal court since the Whiskey Rebellion in the 1790s.

Death sentence

On August 6, 1942, Judge Tuttle sentenced Stephan to be hanged by the neck until dead, setting an execution date of November 13, 1942. In explaining his decision, Tuttle stated:

In his comments from the bench, Judge Tuttle also reported that he had learned that the Stephans obtained their American citizenship by lying about residing in Detroit when they had actually been living in Windsor, Ontario (across the river in Canada) and operating a saloon and bed-house for unmarried couples. Tuttle also criticized Stephan's wife for disloyal statements and urged that proceedings be launched to revoke her citizenship and to have her interned. Tuttle further offered his belief that there was a well-established "underground railway" of German loyalists to aid escaped prisoners with Stephan as an essential link.

Stephan's wife, Agnes, collapsed outside the courtroom when the verdict was explained by a bailiff. On his return to prison from the sentencing, Stephan reportedly told a deputy U.S. marshall who was guarding him, "I'll bet all the tea in China I won't hang."

On August 6, 1942, Judge Tuttle sentenced Stephan to be hanged by the neck until dead, setting an execution date of November 13, 1942. In explaining his decision, Tuttle stated:

In his comments from the bench, Judge Tuttle also reported that he had learned that the Stephans obtained their American citizenship by lying about residing in Detroit when they had actually been living in Windsor, Ontario (across the river in Canada) and operating a saloon and bed-house for unmarried couples. Tuttle also criticized Stephan's wife for disloyal statements and urged that proceedings be launched to revoke her citizenship and to have her interned. Tuttle further offered his belief that there was a well-established "underground railway" of German loyalists to aid escaped prisoners with Stephan as an essential link.

Stephan's wife, Agnes, collapsed outside the courtroom when the verdict was explained by a bailiff. On his return to prison from the sentencing, Stephan reportedly told a deputy U.S. marshall who was guarding him, "I'll bet all the tea in China I won't hang."

Appeals and commutation

Due to appeals, Stephan's execution was moved on several occasions. After the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed the judgment and the Supreme Court declined to intercede, Tuttle reset the execution date for April 27 during a hearing at which the ''Detroit Times'' described Stephan as "a cringing, sobbing, whimpering treasonist." After the Sixth Circuit rejected his appeal, Stephan's appellate attorneys, Nicholas Salowich and James E. McCabe, in April 1943 filed an appeal with President Franklin D. Roosevelt for executive clemency. They also filed a further petition for review to the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court rejected the petition for review in late May. On June 5, 1943, after the petition for rehearing was rejected, Judge Tuttle reset the execution date for July 2, 1943, between the hours of 1 and 2 a.m. at theFederal Correctional Institution, Milan

The Federal Correctional Institution, Milan (FCI Milan) is a U.S. federal prison in Michigan, with most of the prison in York Township, and a portion in Milan. It is operated by the Federal Bureau of Prisons.

This prison is a low-security facil ...

, in Washtenaw County, Michigan. At the time, Judge Tuttle rebuked those petitioning President Roosevelt for clemency on Stephan's behalf. He rejected the uninformed opinion being advanced that Stephan had not intended to help Germany win the war. He noted that thousands of American boys had given their lives while Stephan's execution was postponed and questioned the judgment of those who would hesitate to take the life of a traitor.

A temporary scaffold was installed at the prison for use in the execution. As the execution approached, Stephan was described in the press as "a broken sobbing man." He told the prison chaplain that: he had nightmares of the scaffold every night, a vision that haunted him; he awakened each night with a start; and "I've died a hundred deaths upon it."

At 4:55 p.m. on July 1, nine hours before the scheduled execution, word was received by the warden that President Roosevelt had commuted Stephan's sentence to life imprisonment. The White House issued a statement providing the basis for the commutation as follows:

Aftermath

After his sentence was commuted, Stephan was sent to the United States Penitentiary, Atlanta. He remained there for eight years, at which time he was transferred to the United States Medical Center for Federal Prisoners in Springfield, Missouri. He died of intestinal cancer at the Springfield Medical Center in January 1952. Krug was returned to the Canadian POW camp. He escaped again in August 1943 and was captured three days later. He was transferred to a POW camp in Great Britain where he remained until he was released in 1946. After his release, he worked as a steel salesman in West Germany. He was the subject of a feature story in the '' Detroit Free Press'' in April 1992, 50 years after his weekend in Detroit. Stephan's wife, Agnes Junger Stephan, had her citizenship revoked and was interned in September 1942 as a dangerous enemy alien for the duration of the war. She was deported to Germany at the end of the war. Theodore Donay, born Thaddeus Donaj, the shopkeeper whom Stephan visited with Krug, spent six-and-a-half years in prison and had his citizenship revoked. In April 1950, Donay disappeared after renting a boat on Catalina Island in California. He had purchased 10 feet of galvanized chain, 10 spools of soldering wire, and a pair of pliers. A suicide note was found in his hotel room. In it, he explained his decision with the fact that his nerves had been wrecked by the "constant fear of deportation", which he saw as "a very dark outlook for isfuture" and didn't have the financial means to appeal. He also asserted that he hadn't believed Krug to be a real soldier, that he had told Dietrick Rinterlen so and that Rinterlen had perjured himself by testifying otherwise in order to please the prosecution. Bertelmann, the woman who called on Stephan to help Krug, was imprisoned for six years. Upon her release, she filed for divorce on the grounds that her husband did not visit her while she was in prison.References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Stephan, Max 1892 births 1952 deaths American collaborators with Nazi Germany American prisoners sentenced to death 1942 crimes in the United States German Army personnel of World War I German emigrants to Canada German people imprisoned abroad German prisoners sentenced to death Nazis convicted of crimes Nazis who died in prison custody People convicted of treason against the United States People from Cologne Prisoners sentenced to death by the United States federal government Prisoners who died in United States federal government detention Prussian emigrants to the United States Recipients of American presidential clemency United States home front during World War II