Mass Strike on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A general strike is a

The idea of the general strike was first formulated by

The idea of the general strike was first formulated by

In 1864, the

In 1864, the

In 1881, a

In 1881, a  Some of the general strikes of this period reached revolutionary levels: the

Some of the general strikes of this period reached revolutionary levels: the

In 1889, the

In 1889, the  Having been completely frozen out of the International, the anarchists resolved to hold their own International Anarchist Congress, which met in

Having been completely frozen out of the International, the anarchists resolved to hold their own International Anarchist Congress, which met in

The largest general strike that ever stopped the economy of an advanced industrial country—and the first general

The largest general strike that ever stopped the economy of an advanced industrial country—and the first general

The Beginning of an Era

'', from ''

Chronology of general strikes

by

General Strike 1842

From chartists.net, downloaded 5 June 2006.

Strike! Famous Worker Uprisings

—slideshow by ''

Strikes and You from the National Alliance for Worker and Employer Rights

Seattle General Strike Project

Oakland 1946! Project

{{Authority control Industrial Workers of the World culture Protest tactics

strike action

Strike action, also called labor strike, labour strike in British English, or simply strike, is a work stoppage caused by the mass refusal of employees to Working class, work. A strike usually takes place in response to employee grievances. Str ...

in which participants cease all economic activity, such as working, to strengthen the bargaining position of a trade union or achieve a common social or political goal. They are organised by large coalitions of political, social, and labour organizations and may also include rallies, marches, boycotts, civil disobedience, non-payment of taxes, and other forms of direct or indirect action. Additionally, general strikes might exclude care workers, such as teachers, doctors, and nurses.

Historically, the term general strike has referred primarily to solidarity action

Solidarity action (also known as secondary action, a secondary boycott, a solidarity strike, or a sympathy strike) is industrial action by a trade union in support of a strike initiated by workers in a separate corporation, but often the same ...

, which is a multi-sector strike that is organised by trade unions who strike together in order to force pressure on employers

Employment is a relationship between two parties regulating the provision of paid labour services. Usually based on a contract, one party, the employer, which might be a corporation, a not-for-profit organization, a co-operative, or any other ...

to begin negotiations or offer more favourable terms to the strikers; though not all strikers may have a material interest in each other's negotiations, they all have a material interest in maintaining and strengthening the collective efficacy of strikes as a bargaining tool.

History

Precursors

An early predecessor of the general strike were the Jewish traditions of theSabbatical

A sabbatical (from the Hebrew: (i.e., Sabbath); in Latin ; Greek: ) is a rest or break from work; "an extended period of time intentionally spent on something that’s not your routine job."

The concept of the sabbatical is based on the Bi ...

and Jubilee years, the latter of which involves widespread debt relief and land redistribution

Land, also known as dry land, ground, or earth, is the solid terrestrial surface of Earth not submerged by the ocean or another body of water. It makes up 29.2% of Earth's surface and includes all continents and islands. Earth's land surface ...

. The ''secessio plebis

''Secessio plebis'' (''withdrawal of the commoners'', or ''secession of the plebs'') was an informal exercise of power by Rome's plebeian citizens between the 5th century BC and 3rd century BC., similar in concept to the general strike. During ...

'', during the times of the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( ) was the era of Ancient Rome, classical Roman civilisation beginning with Overthrow of the Roman monarchy, the overthrow of the Roman Kingdom (traditionally dated to 509 BC) and ending in 27 BC with the establis ...

, has also been noted as a precursor to the general strike.

Early conceptions of the general strike were proposed during the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

by Étienne de La Boétie

Étienne or Estienne de La Boétie (; ; 1 November 1530 – 18 August 1563) was a French magistrate, classicist, writer, poet and political theorist, best remembered for his friendship with essayist Michel de Montaigne. His early political trea ...

, and during the Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment (also the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment) was a Europe, European Intellect, intellectual and Philosophy, philosophical movement active from the late 17th to early 19th century. Chiefly valuing knowledge gained th ...

by Jean Meslier

Jean Meslier (; also Mellier; 15 June 1664 – 17 June 1729) was a French Catholic priest (abbé) who was discovered, upon his death, to have written a book-length philosophical essay promoting atheism and materialism. Described by the author as ...

and Honoré Gabriel Riqueti

Honoré is a name of French origin and may refer to several people or places:

Given name

Sovereigns of Monaco

Lords of Monaco

* Honoré I of Monaco

Princes of Monaco

* Honoré II of Monaco

*Honoré III of Monaco

* Honoré IV of Monaco

* Honoré ...

. With the outbreak of the French Revolution, the idea was taken up by radicals such as Jean-Paul Marat

Jean-Paul Marat (, , ; born Jean-Paul Mara; 24 May 1743 – 13 July 1793) was a French political theorist, physician, and scientist. A journalist and politician during the French Revolution, he was a vigorous defender of the ''sans-culottes ...

, Sylvain Maréchal

Sylvain Maréchal (; 15 August 1750 – 18 January 1803) was a French essayist, poet, philosopher and political theorist, whose views presaged utopian socialism and communism. His views on a future golden age are occasionally described as ''uto ...

and Constantin François de Chassebœuf

Constantin is an Aromanian, Megleno-Romanian and Romanian male given name. It can also be a surname.

For a list of notable people called Constantin, see Constantine (name).

See also

* Constantine (name)

* Konstantin

The first name Konstant ...

, who proposed a strike that included merchant

A merchant is a person who trades in goods produced by other people, especially one who trades with foreign countries. Merchants have been known for as long as humans have engaged in trade and commerce. Merchants and merchant networks operated i ...

s and industrialists

A business magnate, also known as an industrialist or tycoon, is a person who is a powerful entrepreneur and investor who controls, through personal enterprise ownership or a dominant shareholding position, a firm or industry whose goods or ser ...

alongside industrial workers and farmworker

A farmworker, farmhand or agricultural worker is someone employed for labor in agriculture. In labor law, the term "farmworker" is sometimes used more narrowly, applying only to a hired worker involved in agricultural production, including har ...

s. In his essay , Chassebœuf proposed a general strike by "every profession useful to society" against the "civil, military, or religious agents of government", contrasting "the People" against the "men who do nothing". Chassebœuf's work held a great influence in Great Britain, where it was distributed throughout the country by the London Corresponding Society

The London Corresponding Society (LCS) was a federation of local reading and debating clubs that in the decade following the French Revolution agitated for the democratic reform of the British Parliament. In contrast to other reform associatio ...

, while his chapter on the general strike was reprinted for decades after its initial publication. The idea was later taken up by the British economist Thomas Attwood and the French communist Louis Auguste Blanqui

Louis Auguste Blanqui (; 8 February 1805 – 1 January 1881) was a French socialist, political philosopher and political activist, notable for his revolutionary theory of Blanquism.

Biography Early life, political activity and first impris ...

.

During the early years of the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution, sometimes divided into the First Industrial Revolution and Second Industrial Revolution, was a transitional period of the global economy toward more widespread, efficient and stable manufacturing processes, succee ...

, an ill-defined conception of a general strike was expressed by workers in Nottingham

Nottingham ( , East Midlands English, locally ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and Unitary authorities of England, unitary authority area in Nottinghamshire, East Midlands, England. It is located south-east of Sheffield and nor ...

and Manchester

Manchester () is a city and the metropolitan borough of Greater Manchester, England. It had an estimated population of in . Greater Manchester is the third-most populous metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, with a population of 2.92&nbs ...

, but it lacked a systematic formulation. There were periodic strikes throughout the early 19th century that could loosely be considered as 'general strikes'. In the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

, the 1835 Philadelphia General Strike lasted for three weeks, after which the striking workers won their goal of a ten-hour workday and an increase in wages.

Conception

William Benbow

William Benbow (1787 – 1864) was a nonconformist preacher, pamphleteer, pornographer and publisher, and a prominent figure of the Reform Movement in Manchester and London.Quaker

Quakers are people who belong to the Religious Society of Friends, a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations. Members refer to each other as Friends after in the Bible, and originally, others referred to them as Quakers ...

and shoemaker

Shoemaking is the process of making footwear.

Originally, shoes were made one at a time by hand, often by groups of shoemakers, or '' cordwainers'' (sometimes misidentified as cobblers, who repair shoes rather than make them). In the 18th cen ...

that became involved in the British radical movement of the early 19th century. After he was arrested for his political activities, Benbow turned away from reformism

Reformism is a political tendency advocating the reform of an existing system or institution – often a political or religious establishment – as opposed to its abolition and replacement via revolution.

Within the socialist movement, ref ...

and began to publish a number of anti-authoritarian

Anti-authoritarianism is opposition to authoritarianism. Anti-authoritarians usually believe in full equality before the law and strong civil liberties. Sometimes the term is used interchangeably with anarchism, an ideology which entails opposing a ...

and anti-clerical

Anti-clericalism is opposition to religious authority, typically in social or political matters. Historically, anti-clericalism in Christian traditions has been opposed to the influence of Catholicism. Anti-clericalism is related to secularism, ...

polemics. At meetings of the National Union of the Working Classes

The Rotunda radicals, known at the time as Rotundists or Rotundanists, were a diverse group of social, political and religious radical reformers who gathered around the Blackfriars Rotunda, London, between 1830 and 1832, while it was under the mana ...

, Benbow expressed impatience with the progress of the Reform Bill

The Reform Acts (or Reform Bills, before they were passed) are legislation enacted in the United Kingdom in the 19th and 20th century to enfranchise new groups of voters and to redistribute seats in the House of Commons of the Parliament of the U ...

and called for armed resistance against the government.

In January 1832, Benbow published a pamphlet titled ''Grand National Holiday and Congress of the Productive Classes'', in which he outlined his proposals for a general strike. Benbow called for workers themselves to declare a month-long "holiday", which would be financially supported first by workers' savings and then by exacting "contributions" from the wealthy. He also proposed the formation of workers' council

A workers' council, also called labour council, is a type of council in a workplace or a locality made up of workers or of temporary and instantly revocable delegates elected by the workers in a locality's workplaces. In such a system of polit ...

s to keep the peace, distribute food and elect delegates to a congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

, which would itself carry out wide-reaching societal reforms. Months after the pamphlet's publication, Benbow was arrested for leading a 100,000-strong demonstration, which he had intended as a "dress rehearsal" for his proposed "national holiday".

The passage of the Reform Act brought with it the collapse of the radical movement, including Benbow's National Union. But six years later, in an atmosphere of rising disillusionment with the progress of political reform, the nascent Chartist movement

Chartism was a working-class movement for political reform in the United Kingdom that erupted from 1838 to 1857 and was strongest in 1839, 1842 and 1848. It took its name from the People's Charter of 1838 and was a national protest movement, wi ...

adopted Benbow's platform for a "national holiday". The Chartists planned to carry out their month-long national holiday in August 1839, but following Benbow's arrest, the campaign was abandoned. Benbow was tried and found guilty of sedition. Although he attempted to continue his Chartist activities from prison, after being excommunicated from the movement by Feargus O'Connor

Feargus Edward O'Connor (18 July 1796 – 30 August 1855) was an Irish Chartism, Chartist leader and advocate of the Land Plan, which sought to provide smallholdings for the labouring classes. A highly charismatic figure, O'Connor was admired ...

, Benbow ceased his political activities.

Early expressions

In April 1842, after the second Chartist Petition was rejected by the British Parliament, demands for fairer wages and conditions across many different industries finally exploded into the first general strike in a capitalist country. The strike began in thecoal mine

Coal mining is the process of resource extraction, extracting coal from the ground or from a mine. Coal is valued for its Energy value of coal, energy content and since the 1880s has been widely used to Electricity generation, generate electr ...

s of Staffordshire

Staffordshire (; postal abbreviation ''Staffs''.) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the West Midlands (region), West Midlands of England. It borders Cheshire to the north-west, Derbyshire and Leicestershire to the east, ...

and soon spread throughout Britain, affecting factories

A factory, manufacturing plant or production plant is an industrial facility, often a complex consisting of several buildings filled with machinery, where workers manufacture items or operate machines which process each item into another. Th ...

, mills

Mills is the plural form of mill, but may also refer to:

As a name

* Mills (surname), a common family name of English or Gaelic origin

* Mills (given name)

*Mills, a fictional British secret agent in a trilogy by writer Manning O'Brine

Places U ...

and mines from Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

to South Wales

South Wales ( ) is a Regions of Wales, loosely defined region of Wales bordered by England to the east and mid Wales to the north. Generally considered to include the Historic counties of Wales, historic counties of Glamorgan and Monmouthshire ( ...

. Although the general strike started as an apolitical demand for better working conditions, by August 1842, it became directly associated with the Chartists and took on a revolutionary character. But government forces intervened, cracking down on the protests and arresting its leaders, eventually forcing a return to work.

Strike actions by workers in Barcelona played a prominent role in the Spanish Revolution of 1854

The Spanish Revolution of 1854, also known by the name ''Vicalvarada'', started with a confrontation between rebel troops under General Leopoldo O'Donnell, 1st Duke of Tetuan and government troops near the village of Vicálvaro.

This incident ...

, which gave way to a progressive period that extended a number of civil liberties

Civil liberties are guarantees and freedoms that governments commit not to abridge, either by constitution, legislation, or judicial interpretation, without due process. Though the scope of the term differs between countries, civil liberties of ...

to Spanish workers. But labour unrest grew as the new authorities again prohibited freedom of association

Freedom of association encompasses both an individual's right to join or leave groups voluntarily, the right of the group to take collective action to pursue the interests of its members, and the right of an association to accept or decline membe ...

and work stoppages, leading to the outbreak of the 1855 Catalan general strike

The 1855 Catalan general strike was a general strike that took place in 1855 after the execution of . It was the first general strike in Spanish history, resulting in mass demonstrations and the death of a factory manager in Sants, Barcelona. ...

, the first in Spanish history. After months of strike action and attempted negotitations, the general strike was suppressed and the draft constitution suspended in a coup by Leopoldo O'Donnell

Leopoldo O'Donnell y Jorris, 1st Duke of Tetuán, GE (12 January 1809 – 5 November 1867), was a Spanish general and Grandee who was Prime Minister of Spain on several occasions.

Early life

He was born at Santa Cruz de Tenerife in the Cana ...

.

During the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

, millions of black slaves

The Atlantic slave trade or transatlantic slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of enslaved African people to the Americas. European slave ships regularly used the triangular trade route and its Middle Passage. Europeans est ...

escaped southern plantations and fled to Union territory, depriving the Confederacy of its main source of labour in what W. E. B. Du Bois

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois ( ; February 23, 1868 – August 27, 1963) was an American sociologist, socialist, historian, and Pan-Africanist civil rights activist.

Born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, Du Bois grew up in a relativel ...

described as a "general strike" in his book ''Black Reconstruction in America

''Black Reconstruction in America: An Essay Toward a History of the Part Which Black Folk Played in the Attempt to Reconstruct Democracy in America, 1860–1880'' is a history of the Reconstruction Era, Reconstruction era by W. E. B. Du Bois, f ...

''. However, this conception were rebuffed by African-American economist Abram Lincoln Harris

Abram Lincoln Harris Jr. (January 17, 1899 – November 6, 1963) was an American economist, academic, anthropologist and a social critic of the condition of black people in the United States. He was considered by many as the first African Americ ...

, who dismissed Du Bois' claims of a general strike as fantastical. A. A. Taylor also rejected Du Bois' interpretation, noting that the flight from the plantations did not constitute an organised movement to achieve economic or political concessions. And American historian Arthur Charles Cole criticised what he described as "discrepancies between well established facts and extravagant generalization" in Du Bois' claims of a general strike.

Debate in the First International

In 1864, the

In 1864, the International Workingmen's Association

The International Workingmen's Association (IWA; 1864–1876), often called the First International, was a political international which aimed at uniting a variety of different left-wing socialist, social democratic, communist, and anarchist g ...

(IWA) was established as a federation of trade unions by delegates from England and France. The French trade union delegates, such as Eugene Varlin, saw the nascent International as a means to coordinate support for strike action

Strike action, also called labor strike, labour strike in British English, or simply strike, is a work stoppage caused by the mass refusal of employees to Working class, work. A strike usually takes place in response to employee grievances. Str ...

s by its members. In the first volume of ''Das Kapital

''Capital: A Critique of Political Economy'' (), also known as ''Capital'' or (), is the most significant work by Karl Marx and the cornerstone of Marxian economics, published in three volumes in 1867, 1885, and 1894. The culmination of his ...

'', published in 1867, Karl Marx

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

conceived of the general strike as a means by which to build class consciousness

In Marxism, class consciousness is the set of beliefs that persons hold regarding their social class or economic rank in society, the structure of their class, and their common class interests. According to Karl Marx, class consciousness is an awa ...

.

At the International's Brussels Congress of 1868, the Belgian delegate CĂ©sar De Paepe

César De Paepe (12 July 1841 in Ostend, Belgium – 1890 in Cannes, France) was a Belgian medical doctor, socialist activist and a prominent proponent of syndicalism whose work strongly influenced the Industrial Workers of the World and the synd ...

proposed that a general strike could be used to prevent the outbreak of war, which he considered to be a means for the ruling class to subordinate working people. He further declared that trade unions themselves constituted the mechanism for replacing capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by ...

with socialism

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

, the establishment of which would put a final end to all wars. In a letter to Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels ( ;"Engels"

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''.Mikhail Bakunin Mikhail Alexandrovich Bakunin. Sometimes anglicized to Michael Bakunin. ( ; – 1 July 1876) was a Russian revolutionary anarchist. He is among the most influential figures of anarchism and a major figure in the revolutionary socialist, s ...

joined the International the following year, he declared his own support for these proposals. Bakunin rejected political participation, instead advocating for workers to take strike actions to improve their working conditions. He argued that the International could be the organisation through which trade unions could build such strike actions into a revolutionary general strike, which would abolish capitalism and institute socialism.

The proposals for a revolutionary general strike to overthrow the state were rejected by the Marxist faction, who instead proposed the creation of political parties to take state power. Through the General Council, which had centralised control over the International, Marx moved to expel Bakunin's anti-authoritarian faction at the Hague Congress of 1872. In response, the expelled sections established the ''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''.Mikhail Bakunin Mikhail Alexandrovich Bakunin. Sometimes anglicized to Michael Bakunin. ( ; – 1 July 1876) was a Russian revolutionary anarchist. He is among the most influential figures of anarchism and a major figure in the revolutionary socialist, s ...

Anti-Authoritarian International

The Anti-Authoritarian International (also known as the Anarchist International of St. Imier) was an international workers' organization formed in 1872 after the split in the First International between the anarchists and the Marxists. This follo ...

, which was designed to operate according to a federal structure. The anti-authoritarians upheld the syndicalist view of using the International as a coordinating body to support strike actions and build them towards a revolutionary general strike, which would overthrow the state and establish workers' control

Workers' control is participation in the management of factories and other commercial enterprises by the people who work there. It has been variously advocated by anarchists, socialists, communists, social democrats, distributists and Christi ...

over the means of production

In political philosophy, the means of production refers to the generally necessary assets and resources that enable a society to engage in production. While the exact resources encompassed in the term may vary, it is widely agreed to include the ...

. This view was particularly supported by the Spanish Regional Federation, which itself organised a general strike

A general strike is a strike action in which participants cease all economic activity, such as working, to strengthen the bargaining position of a trade union or achieve a common social or political goal. They are organised by large coalitions ...

in Alcoy

Alcoy (; ; officially: / ) is an industrial and university city, region and municipality located in the Valencian Community, Spain. The Serpis river crosses the municipal boundary of Alcoy. The local authority reported a population of 61,135 r ...

, although it was quickly put down by Spanish government

The government of Spain () is the central government which leads the executive branch and the General State Administration of the Kingdom of Spain.

The Government consists of the Prime Minister and the Ministers; the prime minister has the o ...

forces.

At the Geneva Congress of 1873, Belgian delegates proposed the adoption of the general strike as a tactic for social revolution

Social revolutions are sudden changes in the structure and nature of society. These revolutions are usually recognized as having transformed society, economy, culture, philosophy, and technology along with but more than just the political system ...

. This motion was supported by the Jura Federation

The Jura Federation () represented the anarchist, Bakuninist faction of the First International during the anti-statist split from the organization. The Canton of Jura, a Swiss area, was known for its watchmaker artisans in La Chaux-de-Fonds, w ...

, which additionally stressed the need for smaller strikes as a means to achieve wage increases. The discussions over strike action at the Geneva Congress lay the foundations for what was to become known as anarcho-syndicalism

Anarcho-syndicalism is an anarchism, anarchist organisational model that centres trade unions as a vehicle for class conflict. Drawing from the theory of libertarian socialism and the practice of syndicalism, anarcho-syndicalism sees trade uni ...

. But before long, the anti-authoritarians began to move away from the anarcho-syndicalist model. Members of the Belgian section began to advocate for a dictatorship of the proletariat and electoralism

Electoralism is a term first used by Terry Karl, professor of political science at Stanford University, to describe a "half-way" transition from authoritarian rule toward democratic rule.

As a topic in the dominant party system political scien ...

, while the French and Italian sections moved towards anarcho-communism

Anarchist communism is a far-left political ideology and anarchist school of thought that advocates communism. It calls for the abolition of private real property but retention of personal property and collectively-owned items, goods, and se ...

and proposed the theory of propaganda of the deed

Propaganda of the deed, or propaganda by the deed, is a type of direct action intended to influence public opinion. The action itself is meant to serve as an example for others to follow, acting as a catalyst for social revolution.

It is primari ...

. By 1880, the debates within the International had led to its collapse.

Rise of revolutionary syndicalism

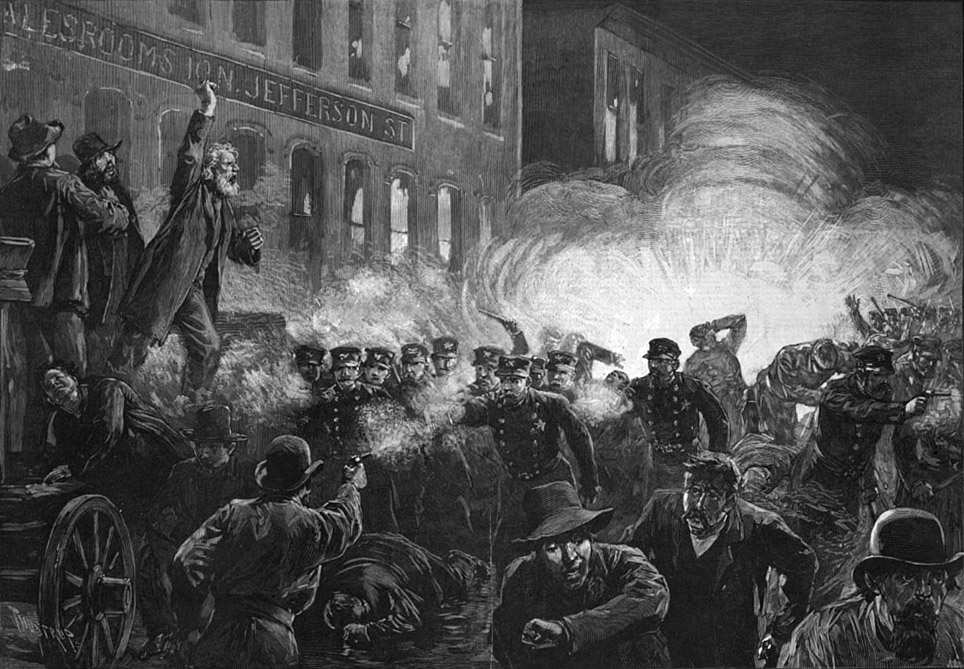

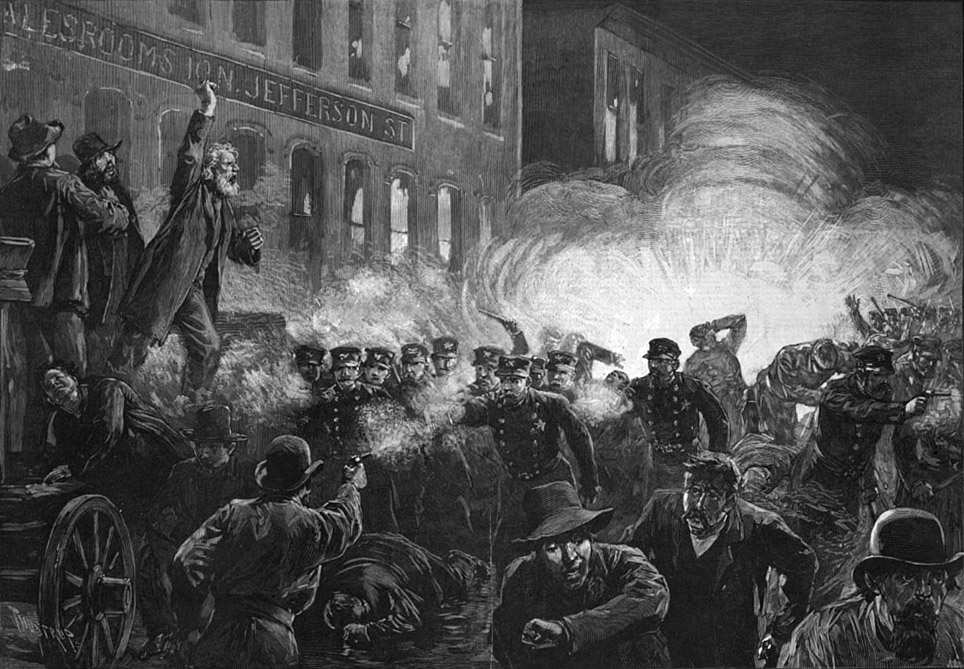

In 1881, a

In 1881, a revolutionary socialist

Revolutionary socialism is a political philosophy, doctrine, and tradition within socialism that stresses the idea that a social revolution is necessary to bring about structural changes in society. More specifically, it is the view that revolu ...

faction of the Socialist Labor Party of America

The Socialist Labor Party (SLP)"The name of this organization shall be Socialist Labor Party". Art. I, Sec. 1 of thadopted at the Eleventh National Convention (New York, July 1904; amended at the National Conventions 1908, 1912, 1916, 1920, 192 ...

(SLPA) split off and established the International Working People's Association

The International Working People's Association (IWPA), sometimes known as the "Black International," and originally named the "International Revolutionary Socialists", was an international anarchist political organization established in 1881 at a ...

(IWPA), which developed anarchist tendencies and held itself to be a continuation of the defunct IWA. Inspired by the example of the Paris Commune

The Paris Commune (, ) was a French revolutionary government that seized power in Paris on 18 March 1871 and controlled parts of the city until 28 May 1871. During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, the French National Guard (France), Nation ...

, IWPA members such as the Chicago anarchist Albert Parsons

Albert Richard Parsons (June 20, 1848 – November 11, 1887) was a pioneering American socialist and later Anarchism in the United States, anarchist newspaper editor, orator, and labor activist. As a teenager, he served in the military force of ...

formulated a kind of revolutionary syndicalism that eschewed the general strike in favour of popular insurrection. In response to the repression of the Great Railroad Strike of 1877

The Great Railroad Strike of 1877, sometimes referred to as the Great Upheaval, began on July 14 in Martinsburg, West Virginia, after the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) cut wages for the third time in a year. The Great Railroad Strike of 187 ...

, the IWPA armed and drilled its members into workers' militias, seeing violent action as a necessary complement to strike action. On 1 May 1886, the IWPA organised a nationwide general strike for the eight-hour day

The eight-hour day movement (also known as the 40-hour week movement or the short-time movement) was a social movement to regulate the length of a working day, preventing excesses and abuses of working time.

The modern movement originated i ...

, which had been a focus of demands for Parsons and the Chicago anarchists. Throughout the United States, hundreds of thousands of workers went on strike. The general strike's epicenter was in Chicago, where protests against the police repression of striking workers escalated into a riot

A riot or mob violence is a form of civil disorder commonly characterized by a group lashing out in a violent public disturbance against authority, property, or people.

Riots typically involve destruction of property, public or private. The p ...

. Eight of the protest's organisers, including Parsons, were executed by hanging on charges of conspiracy. In the wake of their execution, the IWPA demand for the eight-hour day spread around the world and 1 May was declared International Workers' Day

International Workers' Day, also called Labour Day in some countries and often referred to as May Day, is a celebration of Wage labour, labourers and the working classes that is promoted by the international labour movement and occurs every yea ...

.

Inspired by the IWPA's general strike, European anarchists began to reconsider the general strike as a revolutionary instrument, with the French anarchist Joseph Tortelier taking up the idea of the revolutionary general strike, which then spread to Italian and Spanish anarchists. Albert Parsons' wife Lucy Parsons

Lucy E. Parsons ( – March 7, 1942) was a US social anarchist and later anarcho-communist, well-known throughout her long life for her fiery speeches and writings. She was a founding member of the Industrial Workers of the World. There are d ...

also adopted the revolutionary general strike in her own platform, which became a founding precept of the Industrial Workers of the World

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), whose members are nicknamed "Wobblies", is an international labor union founded in Chicago, United States in 1905. The nickname's origin is uncertain. Its ideology combines general unionism with indu ...

(IWW). The first trade union to adopt the revolutionary general strike into its platform was the French General Confederation of Labour (CGT). The CGT launched its own campaign for workers themselves to institute the eight-hour day, culminating in a general strike which secured French workers a reduction in working time and workload, an increase in wages and the introduction of the weekend

The weekdays and weekend are the complementary parts of the week, devoted to labour and rest, respectively. The legal weekdays (British English), or workweek (American English), is the part of the seven-day week devoted to working. In most o ...

.

The CGT's example accelerated the spread of revolutionary syndicalism throughout the world, bringing with it a wave of general strikes at the turn of the 20th century, to mixed results. Although the Belgian general strike of 1893

The general strike of 1893 (, ) was a major general strike in Belgium in April 1893 called by the Belgian Labour Party (POB–BWP) to pressure the government of Auguste Beernaert to introduce universal manhood suffrage, universal male suffrage in ...

was halted in order to prevent damage to the workers' movement, it eventually won its demand of universal manhood suffrage

Universal manhood suffrage is a form of voting rights in which all adult male citizens within a political system are allowed to vote, regardless of income, property, religion, race, or any other qualification. It is sometimes summarized by the s ...

. Following the Cuban War of Independence

The Cuban War of Independence (), also known in Cuba as the Necessary War (), fought from 1895 to 1898, was the last of three liberation wars that Cuba fought against Spain, the other two being the Ten Years' War (1868–1878) and the Litt ...

, in 1902, anarcho-syndicalists organised the country's first general strike against the government of the new Republic of Cuba

Cuba, officially the Republic of Cuba, is an island country, comprising the island of Cuba (largest island), Isla de la Juventud, and List of islands of Cuba, 4,195 islands, islets and cays surrounding the main island. It is located where the ...

. In the Netherlands

, Terminology of the Low Countries, informally Holland, is a country in Northwestern Europe, with Caribbean Netherlands, overseas territories in the Caribbean. It is the largest of the four constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Nether ...

, the railroad strikes of 1903 resulted in harsh repression against the Dutch workers' movement. The Swedish general strike of 1909 was broken up without achieving its demands, accelerating the split of syndicalists from the social-democratic unions and the formation of the Central Organisation of the Workers of Sweden

The Central Organisation of Swedish Workers (; SAC) is a Sweden, Swedish syndicalist National trade union center, trade union federation. The SAC organises people from all occupations and industries in one single federation, including the Unempl ...

(SAC).

Some of the general strikes of this period reached revolutionary levels: the

Some of the general strikes of this period reached revolutionary levels: the Russian Revolution of 1905

The Russian Revolution of 1905, also known as the First Russian Revolution, was a revolution in the Russian Empire which began on 22 January 1905 and led to the establishment of a constitutional monarchy under the Russian Constitution of 1906, t ...

demonstrated the efficacy of the general strike as a revolutionary instrument, but was ultimately suppressed; in 1909, the Catalan syndicalist union Solidaridad Obrera called a general strike

A general strike is a strike action in which participants cease all economic activity, such as working, to strengthen the bargaining position of a trade union or achieve a common social or political goal. They are organised by large coalitions ...

against conscription

Conscription, also known as the draft in the United States and Israel, is the practice in which the compulsory enlistment in a national service, mainly a military service, is enforced by law. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it conti ...

for the Spanish invasion of Morocco, briefly bringing Barcelona

Barcelona ( ; ; ) is a city on the northeastern coast of Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second-most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within c ...

under workers' control before the revolt's suppression by government forces; and following the Revolution of 1910 in Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic, is a country on the Iberian Peninsula in Southwestern Europe. Featuring Cabo da Roca, the westernmost point in continental Europe, Portugal borders Spain to its north and east, with which it share ...

, a syndicalist-led general strike briefly brought Lisbon

Lisbon ( ; ) is the capital and largest city of Portugal, with an estimated population of 567,131, as of 2023, within its administrative limits and 3,028,000 within the Lisbon Metropolitan Area, metropolis, as of 2025. Lisbon is mainlan ...

under workers' control before being repressed, resulting in the formation of the by Portuguese socialists

Portuguese may refer to:

* anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Portugal

** Portuguese cuisine, traditional foods

** Portuguese language, a Romance language

*** Portuguese dialects, variants of the Portuguese language

** Portu ...

and anarchists

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that seeks to abolish all institutions that perpetuate authority, coercion, or hierarchy, primarily targeting the state and capitalism. Anarchism advocates for the replacement of the state w ...

.

In Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

, there was a particularly large wave of general strikes during this period: the general strike of 1904 resulted in no political reforms but strengthened the social movement; in 1908, syndicalists led a two-month general strike in Parma

Parma (; ) is a city in the northern Italian region of Emilia-Romagna known for its architecture, Giuseppe Verdi, music, art, prosciutto (ham), Parmesan, cheese and surrounding countryside. With a population of 198,986 inhabitants as of 2025, ...

, but were likewise defeated; and in 1911, anarcho-syndicalists mobilised a general strike against the Italian invasion of Libya

The Italian invasion of Libya occurred in 1911, when Italian troops invaded the Turkish province of Libya (then part of the Ottoman Empire) and started the Italo-Turkish War. As result, Italian Tripolitania and Italian Cyrenaica were establishe ...

, blocking troop trains and even assassinating an army officer. This series of syndicalist-led general strikes brought about the establishment of the Italian Syndicalist Union

The Italian Syndicalist Union (; USI) is an Italian anarcho-syndicalist trade union. Established in 1912 by a confederation of " houses of labour", the USI led a series of general strikes throughout its early years, culminating with the Red W ...

(USI), which itself led a further series of general strikes that culminated in the Red Week of 1914.

Debate in the Second International

In 1889, the

In 1889, the Labour and Socialist International

The Labour and Socialist International (LSI) was an international organization of socialist and labourist parties, active between 1923 and 1940. The group was established through a merger of the rival Vienna International and the Berne Intern ...

was established by classical Marxists and social democrats

Social democracy is a social, economic, and political philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy and a gradualist, reformist, and democratic approach toward achieving social equality. In modern practice, s ...

, such as those of the Social Democratic Party of Germany

The Social Democratic Party of Germany ( , SPD ) is a social democratic political party in Germany. It is one of the major parties of contemporary Germany. Saskia Esken has been the party's leader since the 2019 leadership election together w ...

(SPD). At the Brussels Congress of 1891, it became clear that the International was already divided over two main tactical issues: electoral politics

An electoral or voting system is a set of rules used to determine the results of an election. Electoral systems are used in politics to elect governments, while non-political elections may take place in business, nonprofit organizations and inf ...

, which the socialists embraced, but anarchists generally opposed; and, the general strike as a mechanism to prevent war, which anarchists supported, but socialists refused to endorse. As a result, at the ZĂĽrich Congress of 1893, anarchists were ejected from the International and banned from attending future congresses. Anarchist trade union delegates from the French CGT and Dutch NAS

Nas (born 1973) is the stage name of American rapper Nasir Jones.

Nas, NaS, or NAS may also refer to:

Aviation

* Nasair, a low-cost airline carrier and subsidiary based in Eritrea

* National Air Services, an airline in Saudi Arabia

** Nas Air (S ...

attempted to continue participation, but after being physically attacked while trying to join the London Congress of 1896, the anarchists finally abandoned the International.

Nevertheless, the anarchist defense of the general strike left a lasting legacy within the International. At the Paris Congress of 1900, the French socialist

The French Left () refers to Communism, communist, Socialism, socialist, Social democracy, social democratic, Democratic socialism, democratic socialist, and Anarchism, anarchist political forces in France. The term originates from the Nationa ...

politician Aristide Briand

Aristide Pierre Henri Briand (; 28 March 18627 March 1932) was a French statesman who served eleven terms as Prime Minister of France during the French Third Republic. He is mainly remembered for his focus on international issues and reconciliat ...

adopted the idea of the revolutionary general strike in order to boost his popularity with the syndicalists. At the Amsterdam Congress of 1904, another French socialist politician defended the general strike as a means to convince socialist voters that they were not merely supporting career politicians. At the Stuttgart Congress of 1907, the anarchist calls for a general strike to prevent war were taken up by Gustave Hervé

Gustave Hervé (; Brest, January 2, 1871 – Paris, October 25, 1944) was a French politician. At first, he was a fervent antimilitarist socialist and pacifist, but he later turned to equally zealous ultranationalism, declaring his ''patriotisme' ...

, but these were ardently opposed by the German delegates, who feared repression by the authorities. Finally, at the Copenhagen Congress of 1910, a proposal for a general strike to prevent war was put forward by the French socialist Édouard Vaillant

Marie Édouard Vaillant (26 January 1840 – 18 December 1915) was a French politician.

Born in Vierzon, Cher, son of a lawyer, Édouard Vaillant studied engineering at the École Centrale des Arts et Manufactures, graduating in 1862, and then l ...

and the Scottish labour leader Keir Hardie

James Keir Hardie (15 August 185626 September 1915) was a Scottish trade unionist and politician. He was a founder of the Labour Party (UK), Labour Party, and was its first Leader of the Labour Party (UK), parliamentary leader from 1906 to 1908. ...

, but this too was voted down by the other delegates. While it was consistently defeated by the social democrats, the anarchist proposal for a general strike was taken up by members of the far-left

Far-left politics, also known as extreme left politics or left-wing extremism, are politics further to the left on the left–right political spectrum than the standard political left. The term does not have a single, coherent definition; some ...

, such as Karl Liebknecht

Karl Paul August Friedrich Liebknecht (; ; 13 August 1871 – 15 January 1919) was a German politician and revolutionary socialist. A leader of the far-left wing of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), Liebknecht was a co-founder of both ...

and Rosa Luxemburg

Rosa Luxemburg ( ; ; ; born Rozalia Luksenburg; 5 March 1871 – 15 January 1919) was a Polish and naturalised-German revolutionary and Marxist theorist. She was a key figure of the socialist movements in Poland and Germany in the early 20t ...

, who saw it as an instrument for obtaining political concessions.

Having been completely frozen out of the International, the anarchists resolved to hold their own International Anarchist Congress, which met in

Having been completely frozen out of the International, the anarchists resolved to hold their own International Anarchist Congress, which met in Amsterdam

Amsterdam ( , ; ; ) is the capital of the Netherlands, capital and Municipalities of the Netherlands, largest city of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. It has a population of 933,680 in June 2024 within the city proper, 1,457,018 in the City Re ...

in 1907. The Congress played host to a fierce debate between Errico Malatesta

Errico Malatesta (4 December 1853 – 22 July 1932) was an Italian anarchist propagandist, theorist and revolutionary socialist. He edited several radical newspapers and spent much of his life exiled and imprisoned, having been jailed and expel ...

, a proponent of classical anarcho-communism

Anarchist communism is a far-left political ideology and anarchist school of thought that advocates communism. It calls for the abolition of private real property but retention of personal property and collectively-owned items, goods, and se ...

, and Pierre Monatte

Pierre Monatte (15 January 188127 June 1960) was a French trade unionist, a founder of the '' Confédération générale du travail'' (CGT, General Confederation of Labour) at the beginning of the 20th century, and founder of its journal '' La V ...

, a disciple of the new current of anarcho-syndicalism

Anarcho-syndicalism is an anarchism, anarchist organisational model that centres trade unions as a vehicle for class conflict. Drawing from the theory of libertarian socialism and the practice of syndicalism, anarcho-syndicalism sees trade uni ...

. The latter upheld the central role of the trade union in organising a revolutionary general strike to overthrow capitalism, after which the unions would form the basis for the construction of a new stateless society

A stateless society is a society that is not governed by a state. In stateless societies, there is little concentration of authority. Most positions of authority that do exist are very limited in power, and they are generally not perman ...

with a socialist economy

Socialist economics comprises the economic theories, practices and norms of hypothetical and existing socialist economic systems. A socialist economic system is characterized by social ownership and operation of the means of production that m ...

. But the advancement of syndicalism was blocked chiefly by Malatesta, who objected to the class reductionism of the syndicalists. Malatesta was particularly critical of the general strike, which he dismissed as a "magic weapon" that was incapable of fighting a violent conflict with state militaries, which had the ability to starve out workers in the event of such an industrial dispute. Although the anarcho-syndicalists had seen the Amsterdam Congress as a means to establish an international anarchist organisation, efforts in this direction were sabotaged by the conflict between the two factions.

Despite all the calls for a general strike to prevent war, by the outbreak of World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, many socialists dropped their anti-militarism

Antimilitarism (also spelt anti-militarism) is a doctrine that opposes war, relying heavily on a critical theory of imperialism and was an explicit goal of the First and Second International. Whereas pacifism is the doctrine that disputes (especi ...

and instead threw their support behind the Allied war effort. The Second International itself collapsed, leaving only anarcho-syndicalists and Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

to rally an anti-war opposition.

20th century

The1926 United Kingdom general strike

The 1926 general strike in the United Kingdom was a general strike that lasted nine days, from 4 to 12 May 1926. It was called by the General Council of the Trades Union Congress (TUC) in an unsuccessful attempt to force the British government ...

started in the coal industry and rapidly escalated; the unions called out 1,750,000 workers, mainly in the transport and steel sectors, although the strike was successfully suppressed by the government.

The year 1919 saw a number of general strikes throughout the United States and Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its Provinces and territories of Canada, ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, making it the world's List of coun ...

, including two that were considered significant—the Seattle General Strike

The Seattle General Strike was a five-day general work stoppage by 65,000 workers in the city of Seattle, Washington from February 6 to 11, 1919. The goal was to support shipyard workers in several unions who were locked out of their jobs when ...

, and the Winnipeg General Strike

The Winnipeg General Strike of 1919 was one of the most famous and influential strikes in Canadian history. For six weeks, May 15 to June 26, more than 30,000 strikers brought economic activity to a standstill in Winnipeg, Manitoba, which at the ...

. While the IWW participated in the Seattle General Strike, that action was called by the Seattle Central Labor Union, affiliated with the American Federation of Labor

The American Federation of Labor (A.F. of L.) was a national federation of labor unions in the United States that continues today as the AFL-CIO. It was founded in Columbus, Ohio, in 1886 by an alliance of craft unions eager to provide mutual ...

(AFL, predecessor of the AFL–CIO

The American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO) is a national trade union center that is the largest federation of unions in the United States. It is made up of 61 national and international unions, together r ...

).

In June 1919, the AFL national organisation, in session in Atlantic City, New Jersey

Atlantic City, sometimes referred to by its initials A.C., is a Jersey Shore seaside resort city (New Jersey), city in Atlantic County, New Jersey, Atlantic County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey.

Atlantic City comprises the second half of ...

, passed resolutions in opposition to the general strike. The official report of these proceedings described the convention as the "largest and in all probability the most important Convention ever held" by the organisation, in part for having engineered the "overwhelming defeat of the so-called Radical element" via crushing a " One Big Union proposition", and also for defeating a proposal for a nationwide general strike, both "by a vote of more than 20 to 1".''Sheet Metal Workers' Journal'', Amalgamated Sheet Metal Workers' International Alliance, Volumes 24-25, Chicago, Illinois, 1919, pages 265-267 The AFL amended its constitution to disallow any central labour union (i.e., regional labour councils) from "taking a strike vote without prior authorization of the national officers of the union concerned". The change was intended to "check the spread of general strike sentiment and prevent recurrences of what happened at Seattle and is now going on at Winnipeg". The penalty for any unauthorised strike vote was revocation of that body's charter.

As part of the fight for the Indian independence movement

The Indian independence movement was a series of historic events in South Asia with the ultimate aim of ending British Raj, British colonial rule. It lasted until 1947, when the Indian Independence Act 1947 was passed.

The first nationalistic ...

, leader Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (2October 186930January 1948) was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalism, anti-colonial nationalist, and political ethics, political ethicist who employed nonviolent resistance to lead the successful Indian ...

promoted the use of what is called Hartal

Hartal () is a term in many Languages of India, Indian languages for a strike action that was first used during the Indian independence movement (also known as the nationalist movement) of the early 20th century. A hartal is a mass protest, often ...

, a mass protest and a form of civil disobedience that often involved a total shutdown of workplaces, offices, shops, and courts of law.

Legality

In America, after the passage of the anti-unionTaft–Hartley Act

The Labor Management Relations Act, 1947, better known as the Taft–Hartley Act, is a Law of the United States, United States federal law that restricts the activities and power of trade union, labor unions. It was enacted by the 80th United S ...

in 1947, the general strike changed from a tool of labor strike solidarity into a general form of social, political, and economic protest. US Congress passed the law in the wake of the women-led 1946 Oakland General Strike. It outlawed actions taken by unionized workers in support of workers at other companies, effectively rendering both solidarity actions and the general strike itself illegal. Before 1947 and the passage of the Taft–Hartley Act the term general strike meant when various unions would officially go on strike in solidarity with other striking unions. The act made it illegal for one union to go on strike to support another. Hence, the definition and practice of a general strike changed in modern times to mean periodic days of mass action coordinated, often, by unions, but not an official or prolonged strike.

Since then, in the US and Europe the general strike has become a tool of mass economic protest often in conjunction with other forms of electoral action and direct civil action.

Forms

Two of the main forms of general strike are: the political strike, which aims to achieve political and economic reform; and the revolutionary strike, which aims to overthrowcapitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by ...

and the state

State most commonly refers to:

* State (polity), a centralized political organization that regulates law and society within a territory

**Sovereign state, a sovereign polity in international law, commonly referred to as a country

**Nation state, a ...

in a social revolution

Social revolutions are sudden changes in the structure and nature of society. These revolutions are usually recognized as having transformed society, economy, culture, philosophy, and technology along with but more than just the political system ...

. Other forms, identified by Gerhart Niemeyer, include: the general strike as a "revolutionary exercise" which would eventually lead to a transformation of society; a one-day demonstration on International Workers' Day

International Workers' Day, also called Labour Day in some countries and often referred to as May Day, is a celebration of Wage labour, labourers and the working classes that is promoted by the international labour movement and occurs every yea ...

, aimed at identifying a " worldwide proletariat"; and a theoretical mechanism by which to stop wars between nation states.

Industrial unionists such as Ralph Chaplin

Ralph Hosea Chaplin (1887–1961) was an American writer, artist and labor activist.

Background

Chaplin was born in 1887. At the age of seven, he saw a worker shot dead during the Pullman Strike in Chicago, Illinois. He had moved with his f ...

and Stephen Naft also identified four different levels of general strike, rising from a localised strike, to an industry-wide strike, to a nationwide strike, and finally to a revolutionary strike.

Debates on general strikes

Socialists versus anarchists

In his study of the debates within theSecond International

The Second International, also called the Socialist International, was a political international of Labour movement, socialist and labour parties and Trade union, trade unions which existed from 1889 to 1916. It included representatives from mo ...

, Niemeyer perceived the socialist-friendly general strike for political rights within the system and the general strike as a revolutionary mechanism to overthrow the existing order—which he associated with a "rising anarcho-syndicalist movement"—as mutually exclusive. Niemeyer believed that the difficulty arose from the fact that the general strike was "one instrument", but was frequently considered "without distinction of underlying motives".

Syndicalism and general strikes

TheIndustrial Workers of the World

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), whose members are nicknamed "Wobblies", is an international labor union founded in Chicago, United States in 1905. The nickname's origin is uncertain. Its ideology combines general unionism with indu ...

(IWW) began to fully embrace the general strike in 1910–1911. The ultimate goal of the general strike, according to Industrial Workers of the World theory, is to displace capitalists and give control over the means of production to workers. In a 1911 speech in New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

, IWW organiser Bill Haywood

William Dudley Haywood (February 4, 1869 – May 18, 1928), nicknamed "Big Bill", was an American labor organizer and founding member and leader of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and a member of the executive committee of the Socia ...

explained his view of the economic situation, and why he believed a general strike was justified,

Bill Haywood

William Dudley Haywood (February 4, 1869 – May 18, 1928), nicknamed "Big Bill", was an American labor organizer and founding member and leader of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and a member of the executive committee of the Socia ...

believed that industrial unionism

Industrial unionism is a trade union organising method through which all workers in the same industry are organized into the same union, regardless of skill or trade, thus giving workers in one industry, or in all industries, more leverage in b ...

made possible the general strike, and the general strike made possible industrial democracy. According to Wobbly theory, the conventional strike is an important (but not the only) weapon for improving wages, hours, and working conditions for working people. These strikes are also good training to help workers educate themselves about the class struggle, and about what it will take to execute an eventual general strike for the purpose of achieving industrial democracy. During the final general strike, workers would not walk out of their shops, factories, mines, and mills, but would rather occupy their workplaces and take them over. Prior to taking action to initiate industrial democracy, workers would need to educate themselves with technical and managerial knowledge in order to operate industry.

According to labor historian Philip S. Foner

Philip Sheldon Foner (December 14, 1910 – December 13, 1994) was an American labor historian and teacher. Foner was a prolific author and editor of more than 100 books. He is considered a pioneer in his extensive works on the role of radical ...

, the Wobbly conception of industrial democracy is intentionally not presented in detail by IWW theorists; in that sense, the details are left to the "future development of society". However, certain concepts are implicit. Industrial democracy will be "a new society uiltwithin the shell of the old". Members of the industrial union educate themselves to operate industry according to democratic principles, and without the current hierarchical ownership/management structure. Issues such as production and distribution would be managed by the workers themselves.

In 1927 the IWW called for a three-day nationwide walkout to protest the execution of anarchists Ferdinando Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti. The most notable response to the call was in the Walsenburg

Walsenburg is the statutory city that is the county seat of and the most populous municipality in Huerfano County, Colorado, United States. The city population was 3,049 at the 2020 census, down from 3,068 in 2010.

History

Walsenburg was or ...

coal district of Colorado

Colorado is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States. It is one of the Mountain states, sharing the Four Corners region with Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah. It is also bordered by Wyoming to the north, Nebraska to the northeast, Kansas ...

, where 1,132 miners stayed off the job, and only 35 went to work, a participation rate which led directly to the Colorado coal strike of 1927.

On 18 March 2011, the Industrial Workers of the World supported an endorsement of a general strike as a follow-up to protests against Governor Scott Walker's proposed labour legislation in Wisconsin

Wisconsin ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Great Lakes region, Great Lakes region of the Upper Midwest of the United States. It borders Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake Michigan to the east, Michig ...

, following a motion passed by the South Central Federation of Labor (SCFL) of Wisconsin endorsing a statewide general strike as a response to those legislative proposals. The SCFL website states,

Notable general strikes

The largest general strike that ever stopped the economy of an advanced industrial country—and the first general

The largest general strike that ever stopped the economy of an advanced industrial country—and the first general wildcat strike

A wildcat strike is a strike action undertaken by unionised workers without union leadership's authorization, support, or approval; this is sometimes termed an unofficial industrial action. The legality of wildcat strikes varies between countries ...

in history—was May 1968 in France

May 68 () was a period of widespread protests, strikes, and civil unrest in France that began in May 1968 and became one of the most significant social uprisings in modern European history. Initially sparked by student demonstrations agains ...

.The Beginning of an Era

'', from ''

Situationist International

The Situationist International (SI) was an international organization of social revolutionaries made up of avant-garde artists, intellectuals, and political theorists. It was prominent in Europe from its formation in 1957 to its dissolution ...

'' No 12 (September 1969). Translated by Ken Knabb

Ken Knabb (born 1945) is an American writer, translator, and radical theorist, known for his translations of Guy Debord and the Situationist International. His own English-language writings, many of which were anthologized in ''Public Secrets'' ...

. The prolonged strike involved eleven million workers for two weeks in a row, and its impact was such that it almost caused the collapse of the de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French general and statesman who led the Free France, Free French Forces against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Government of the French Re ...

government. Other notable general strikes include:

* In Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic, is a country on the Iberian Peninsula in Southwestern Europe. Featuring Cabo da Roca, the westernmost point in continental Europe, Portugal borders Spain to its north and east, with which it share ...

, a general strike was called in 2011 by the federation of public labour unions to avert austerity measures.

* In Honduras

Honduras, officially the Republic of Honduras, is a country in Central America. It is bordered to the west by Guatemala, to the southwest by El Salvador, to the southeast by Nicaragua, to the south by the Pacific Ocean at the Gulf of Fonseca, ...

, a general strike was called in 2011 by union workers, farmers and other organisations demanding better education, an increase in the minimum wage and against fuel price hikes.

* In Yemen

Yemen, officially the Republic of Yemen, is a country in West Asia. Located in South Arabia, southern Arabia, it borders Saudi Arabia to Saudi Arabia–Yemen border, the north, Oman to Oman–Yemen border, the northeast, the south-eastern part ...

, thousands of people took the streets in a general strike in 2011 to protest President Ali Abdullah Saleh

Ali Abdullah Saleh Affash (21 March 1947There is a dispute as to Saleh's date of birth, some saying that it was on 21 March 1942. See: However, by Saleh's own confession (an interview recorded in a YouTube video), he was born in 1947.4 Decembe ...

.

* In Algeria

Algeria, officially the People's Democratic Republic of Algeria, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It is bordered to Algeria–Tunisia border, the northeast by Tunisia; to Algeria–Libya border, the east by Libya; to Alger ...

, public sector workers in 2011 mounted a general strike for higher wages and improved working conditions.

* In February 1947, General Douglas MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur (26 January 18805 April 1964) was an American general who served as a top commander during World War II and the Korean War, achieving the rank of General of the Army. He served with distinction in World War I; as chief of ...

, as Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers

The Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (), or SCAP, was the title held by General Douglas MacArthur during the United States-led Allied occupation of Japan following World War II. It issued SCAP Directives (alias SCAPIN, SCAP Index Number) ...

in Japan, banned a planned general strike of 2,400,000 government workers, stating that "so deadly a social weapon" as a general strike should not be used in the impoverished and emaciated condition of Japan so soon after World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. Japan's labour leaders complied with his ban.The Sydney Morning Herald, 1 February 1947, page 1

* In June 2022, Tunisian workers initiated a general strike that halted all transportation.

* In Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia ( ; Czech language, Czech and , ''ÄŚesko-Slovensko'') was a landlocked country in Central Europe, created in 1918, when it declared its independence from Austria-Hungary. In 1938, after the Munich Agreement, the Sudetenland beca ...

, a 1989 general strike helped topple the communist government.

See also

*Civil disobedience

Civil disobedience is the active and professed refusal of a citizenship, citizen to obey certain laws, demands, orders, or commands of a government (or any other authority). By some definitions, civil disobedience has to be nonviolent to be cal ...

* Civil resistance

Civil resistance is a form of political action that relies on the use of nonviolent resistance by ordinary people to challenge a particular power, force, policy or regime. Civil resistance operates through appeals to the adversary, pressure and co ...

* Critique of work

Critique of work or critique of labour is the critique of, or wish to abolish, work ''as such'', and to critique what the critics of works deem wage slavery.

Critique of work can be existential, and focus on how labour can be and/or feel meani ...

* Demonstration (political)

A political demonstration is an action by a mass group or collection of groups of people in favor of a political or other cause or people partaking in a protest against a cause of concern; it often consists of walking in a mass march formati ...

* Direct action

Direct action is a term for economic and political behavior in which participants use agency—for example economic or physical power—to achieve their goals. The aim of direct action is to either obstruct a certain practice (such as a governm ...

* Earth Strike

* Georges Sorel

Georges Eugène Sorel (; ; 2 November 1847 – 29 August 1922) was a French social thinker, political theorist, historian, and later journalist. He has inspired theories and movements grouped under the name of Sorelianism. His social and ...

* Hartal

Hartal () is a term in many Languages of India, Indian languages for a strike action that was first used during the Indian independence movement (also known as the nationalist movement) of the early 20th century. A hartal is a mass protest, often ...

* Industrial Workers of the World

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), whose members are nicknamed "Wobblies", is an international labor union founded in Chicago, United States in 1905. The nickname's origin is uncertain. Its ideology combines general unionism with indu ...

* Industrial unionism

Industrial unionism is a trade union organising method through which all workers in the same industry are organized into the same union, regardless of skill or trade, thus giving workers in one industry, or in all industries, more leverage in b ...

* List of strikes

The following is a list of specific strikes (workers refusing to work, seeking to change their conditions in a particular industry or an individual workplace, or striking in solidarity with those in another particular workplace) and general str ...

* Nonviolent resistance

Nonviolent resistance, or nonviolent action, sometimes called civil resistance, is the practice of achieving goals such as social change through symbolic protests, civil disobedience, economic or political noncooperation, satyagraha, construct ...

* Occupation of factories

Occupation of factories is a method of the workers' movement used to prevent lock outs. They may sometimes lead to "recovered factories", in which the workers self-manage the factories.

They have been used in many strike actions, including:

*t ...

* Protest

A protest (also called a demonstration, remonstration, or remonstrance) is a public act of objection, disapproval or dissent against political advantage. Protests can be thought of as acts of cooperation in which numerous people cooperate ...

* Secessio plebis

''Secessio plebis'' (''withdrawal of the commoners'', or ''secession of the plebs'') was an informal exercise of power by Rome's plebeian citizens between the 5th century BC and 3rd century BC., similar in concept to the general strike. During ...

* Stay away

A stay away, also known as a ''stay-away'' or ''stayaway'', is a form of general strike where people are told to "stay away" from work. This term has often been used in local communications when organizing various strike actions in Zimbabwe betwee ...

* Syndicalism

Syndicalism is a labour movement within society that, through industrial unionism, seeks to unionize workers according to industry and advance their demands through Strike action, strikes and other forms of direct action, with the eventual goa ...

* Workers' self-management

Workers' self-management, also referred to as labor management and organizational self-management, is a form of organizational management based on self-directed work processes on the part of an organization's workforce. Self-managed economy, ...

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

Chronology of general strikes

by

Rosa Luxemburg

Rosa Luxemburg ( ; ; ; born Rozalia Luksenburg; 5 March 1871 – 15 January 1919) was a Polish and naturalised-German revolutionary and Marxist theorist. She was a key figure of the socialist movements in Poland and Germany in the early 20t ...

(1906).

General Strike 1842

From chartists.net, downloaded 5 June 2006.

Strike! Famous Worker Uprisings

—slideshow by ''

Life

Life, also known as biota, refers to matter that has biological processes, such as Cell signaling, signaling and self-sustaining processes. It is defined descriptively by the capacity for homeostasis, Structure#Biological, organisation, met ...

'' magazine.

Strikes and You from the National Alliance for Worker and Employer Rights

Seattle General Strike Project

Oakland 1946! Project

{{Authority control Industrial Workers of the World culture Protest tactics