The maritime republics (), also called merchant republics (), were Italian

thalassocratic port cities which, starting from the

Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

, enjoyed political autonomy and economic prosperity brought about by their maritime activities. The term, coined during the 19th century, generally refers to four Italian cities, whose coats of arms have been shown since 1947 on the flags of the

Italian Navy

The Italian Navy (; abbreviated as MM) is one of the four branches of Italian Armed Forces and was formed in 1946 from what remained of the ''Regia Marina'' (Royal Navy) after World War II. , the Italian Navy had a strength of 30,923 active per ...

and the Italian Merchant Navy:

Amalfi

Amalfi (, , ) is a town and ''comune'' in the province of Salerno, in the region of Campania, Italy, on the Gulf of Salerno. It lies at the mouth of a deep ravine, at the foot of Monte Cerreto (1,315 metres, 4,314 feet), surrounded by dramatic c ...

,

Genoa

Genoa ( ; ; ) is a city in and the capital of the Italian region of Liguria, and the sixth-largest city in Italy. As of 2025, 563,947 people live within the city's administrative limits. While its metropolitan city has 818,651 inhabitan ...

,

Pisa

Pisa ( ; ) is a city and ''comune'' (municipality) in Tuscany, Central Italy, straddling the Arno just before it empties into the Ligurian Sea. It is the capital city of the Province of Pisa. Although Pisa is known worldwide for the Leaning Tow ...

, and

Venice

Venice ( ; ; , formerly ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 islands that are separated by expanses of open water and by canals; portions of the city are li ...

. In addition to the four best known cities,

Ancona

Ancona (, also ; ) is a city and a seaport in the Marche region of central Italy, with a population of around 101,997 . Ancona is the capital of the province of Ancona, homonymous province and of the region. The city is located northeast of Ro ...

,

[Peris Persi, in ''Conoscere l'Italia'', vol. Marche, Istituto Geografico De Agostini, Novara 1982 (p. 74); AA.VV. ''Meravigliosa Italia, Enciclopedia delle regioni'', edited by Valerio Lugoni, Aristea, Milano; Guido Piovene, in ''Tuttitalia'', Casa Editrice Sansoni, Firenze & Istituto Geografico De Agostini, Novara (p. 31); Pietro Zampetti, in ''Itinerari dell'Espresso'', vol. Marche, edited by Neri Pozza, Editrice L'Espresso, Rome, 1980] Gaeta

Gaeta (; ; Southern Latian dialect, Southern Laziale: ''Gaieta'') is a seaside resort in the province of Latina in Lazio, Italy. Set on a promontory stretching towards the Gulf of Gaeta, it is from Rome and from Naples.

The city has played ...

,

Noli, and, in

Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; ; ) is a historical region located in modern-day Croatia and Montenegro, on the eastern shore of the Adriatic Sea. Through time it formed part of several historical states, most notably the Roman Empire, the Kingdom of Croatia (925 ...

,

Ragusa, are also considered maritime republics; in certain historical periods, they had no secondary importance compared to some of the better known cities.

Uniformly scattered across the Italian peninsula, the maritime republics were important not only for the history of navigation and commerce: in addition to precious goods otherwise unobtainable in Europe, new artistic ideas and news concerning distant countries also spread. From the 10th century, they built fleets of ships both for their own protection and to support extensive trade networks across the Mediterranean, giving them an essential role in reestablishing contacts between

Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

,

Asia

Asia ( , ) is the largest continent in the world by both land area and population. It covers an area of more than 44 million square kilometres, about 30% of Earth's total land area and 8% of Earth's total surface area. The continent, which ...

, and

Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent after Asia. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 20% of Earth's land area and 6% of its total surfac ...

, which had been interrupted during the early Middle Ages. They also had an essential role in the

Crusades

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and at times directed by the Papacy during the Middle Ages. The most prominent of these were the campaigns to the Holy Land aimed at reclaiming Jerusalem and its surrounding t ...

and produced renowned explorers and navigators such as

Marco Polo

Marco Polo (; ; ; 8 January 1324) was a Republic of Venice, Venetian merchant, explorer and writer who travelled through Asia along the Silk Road between 1271 and 1295. His travels are recorded in ''The Travels of Marco Polo'' (also known a ...

and

Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus (; between 25 August and 31 October 1451 – 20 May 1506) was an Italians, Italian explorer and navigator from the Republic of Genoa who completed Voyages of Christopher Columbus, four Spanish-based voyages across the At ...

.

Over the centuries, the maritime republics — both the best known and the lesser known but not always less important — experienced fluctuating fortunes. In the 9th and 10th centuries, this phenomenon began with Amalfi and Gaeta, which soon reached their heyday. Meanwhile, Venice began its gradual ascent, while the other cities were still experiencing the long gestation that would lead them to their autonomy and to follow up on their seafaring vocation. After the 11th century, Amalfi and Gaeta declined rapidly, while Genoa and Venice became the most powerful republics. Pisa followed and experienced its most flourishing period in the 13th century, and Ancona and Ragusa allied to resist Venetian power. Following the 14th century, while Pisa declined to the point of losing its autonomy, Venice and Genoa continued to dominate navigation, followed by Ragusa and Ancona, which experienced their golden age in the 15th century. In the 16th century, with Ancona's loss of autonomy, only the republics of Venice, Genoa, and Ragusa remained, which still experienced great moments of splendor until the mid-17th century, followed by over a century of slow decline that ended with the

Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

ic invasion.

Periodization of the history of the maritime republics

The table below shows the periods of activity of the various maritime republics over the centuries.

Conceptualization of maritime republics

Pre-unification

The expression ''maritime republics'' was coined by nineteenth-century historiography, almost coinciding with the end of the last of them: none of these states had ever defined itself as a maritime republic. Swiss historian

Jean Charles Léonard de Sismondi

Jean Charles Léonard de Sismondi, also known as Jean Charles Leonard Simonde de Sismondi (; 9 May 1773 – 25 June 1842), whose real surname was Simonde, was a Swiss historian and political economist, who is best known for his works on French ...

introduced the expression and focused on the corresponding concept in his 1807 work ''History of the Italian Republics of the Middle Centuries''. In Sismondi's text, the maritime republics were seen as cities dedicated above all to fighting each other over issues related to their commercial expansion, unlike the

medieval commune

Medieval communes in the European Middle Ages had sworn allegiances of mutual defense (both physical defense and of traditional freedoms) among the citizens of a town or city. These took many forms and varied widely in organization and makeup.

C ...

s, which instead fought together against the Empire courageously defending their freedom.

In Italy, up until the unification, this determined a negative judgment on the maritime cities, because their history of mutual struggles appeared in stark contrast to the spirit of the ''

Risorgimento

The unification of Italy ( ), also known as the Risorgimento (; ), was the 19th century political and social movement that in 1861 ended in the annexation of various states of the Italian peninsula and its outlying isles to the Kingdom of ...

''. The only exception was considered the very difficult and finally victorious resistance of

Ancona

Ancona (, also ; ) is a city and a seaport in the Marche region of central Italy, with a population of around 101,997 . Ancona is the capital of the province of Ancona, homonymous province and of the region. The city is located northeast of Ro ...

in the siege of 1173, which the city obtained against the imperial troops of Federico Barbarossa; that victory entered the national imagination as an anticipation of the struggles of Italian patriots against foreign rulers. The episode, however, was included in the municipal epic and not in the seafaring one.

Post-unification

In the first decades after Italian unification, post-''Risorgimento'' patriotism fueled a

rediscovery of the Middle Ages linked to a

romantic nationalism

Romantic nationalism (also national romanticism, organic nationalism, identity nationalism) is the form of nationalism in which the state claims its political legitimacy as an organic consequence of the unity of those it governs. This includes ...

, in particular to those aspects that seemed to prefigure national glory and the struggle for independence. The phenomenon of the "maritime republics" was then reinterpreted, freed from negative prejudice and placed side by side with the glorious history of the medieval communes; thus it also established itself on a popular level. Celebrating history, the Italian maritime cities did not consider their mutual struggles so much as their common seafaring enterprise. In fact, in the post-unification cultural climate, it was considered essential for the formation of the modern Italian people to remember that within the maritime republics and municipalities arose the industriousness that inaugurated the new civilization.

In the ''

Regia Marina'', established immediately after the achievement of national unity and therefore only in 1861, there were heated contrasts between the various pre-unification navies: Sardinian, Tuscan, papal and Neapolitan. The exaltation of the seafaring spirit that united the maritime republics made it possible to highlight a common historical basis and overcome divisions. This necessitated the removal of ancient rivalries; in this regard, of great significance was the return of chains that had closed Pisa's port, which had been stolen by Genoa during the medieval fights. Their return in 1860 was a sign of fraternal affection and of the now indissoluble union between the two cities, as can be read on the plaque affixed after the return.

In 1860, the study of the maritime republics as a unitary phenomenon was introduced in the school curriculum, further popularizing the concept. From that year forward, the high school program required students to address the "causes of the rapid resurgence of Italian maritime trade - Amalfi, Venice, Genoa, Ancona, Pisa" and the "Settlement of the great Italian Navy". For the second class, at the beginning of the year, the teacher was arranged to recall the period in which the maritime republics grew and flourished. Every time the school programs were renewed, the study of the phenomenon of the maritime republics was always confirmed. In 1875, the ministerial indication was also followed up in the history program for technical institutes. That year, Carlo O. Galli claimed in a scholastic textbook that "among all the peoples of Europe, the one who in the Middle Ages rose first to great power" in navigation was the Italian people, and he attributed this to the independence enjoyed by "the maritime republics of Italy, among which Amalfi, Pisa, Genoa, Ancona, Venice, Naples and Gaeta deserve more mention".

In 1895, the sailor

Augusto Vittorio Vecchi, founder of the Italian Naval League and better known as a writer under the pseudonym Jack la Bolina, wrote ''General History of the Navy'', which was widely circulated and described the military exploits of the maritime cities in chronological order of origin and decay, from Amalfi to Pisa, Genoa and Ancona to Venice. In 1899, historian Camillo Manfroni wrote on Italy's maritime history, identifying the period of the maritime republics as that history's most glorious phase. At the end of the 19th century, the history of the maritime republics was thus consolidated and consigned to the 20th century.

20th century

The number "four", which still often occurs today associated with maritime republics, is, as can be seen, not original: the short list of maritime republics was limited to two (Genoa and Venice) or three cities (Genoa, Venice and Pisa); the long list included Genoa, Venice, Pisa, Ancona, Amalfi and Gaeta.

Crucial for the diffusion of the list of four maritime republics was a publication by Captain Umberto Moretti, who was tasked by the Royal Navy in 1904 with documenting the maritime history of Amalfi. The volume was released under the significant title ''The First Maritime Republic of Italy''. From that moment on, the name of Amalfi definitively joined that of the other republics in the short list, shifting the imbalance towards the centre-north of the country with its presence.

In the 1930s, a list made up of four names was consolidated: Amalfi, Pisa, Genoa and Venice. This finally led to the inclusion of the symbols of the four cities in the Italian Navy's flag. The flag, approved in 1941, would not be adopted until 1947 due to

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. In 1955, the four cities represented in the navy flag inspired the

Regatta of the Historical Marine Republics.

Armando Lodolini's 1967 book ''The Republics of the Sea'' resumed the previous long list of maritime republics: Venice, Genoa, Pisa, Ancona, Gaeta, and the Dalmatian Ragusa. Noli's status as a small maritime republic would only come into focus in later decades after previously being affirmed only at an academic level.

In 2000, Italian president

Carlo Azeglio Ciampi

Carlo Azeglio Ciampi (; 9 December 1920 – 16 September 2016) was an Italian politician, statesman and banker who was the President of Italy from 1999 to 2006 and the Prime Minister of Italy from 1993 to 1994.

A World War II veteran, C ...

summed up the maritime republics' historic role with these words:

Description

Characteristics

Elements that characterized a maritime republic were:

*

Independence

Independence is a condition of a nation, country, or state, in which residents and population, or some portion thereof, exercise self-government, and usually sovereignty, over its territory. The opposite of independence is the status of ...

(''

de jure

In law and government, ''de jure'' (; ; ) describes practices that are officially recognized by laws or other formal norms, regardless of whether the practice exists in reality. The phrase is often used in contrast with '' de facto'' ('from fa ...

'' or ''

de facto'')

*Autonomy, economics, politics, and culture essentially based on navigation and maritime trade

*Possession of a fleet of ships, built in its own

arsenal

An arsenal is a place where arms and ammunition are made, maintained and repaired, stored, or issued, in any combination, whether privately or publicly owned. Arsenal and armoury (British English) or armory (American English) are mostly ...

*Establishment of a city-state that would eventually expand further

*Presence of warehouses and

consuls

A consul is an official representative of a government who resides in a foreign country to assist and protect citizens of the consul's country, and to promote and facilitate commercial and diplomatic relations between the two countries.

A consu ...

in Mediterranean ports

*Presence of foreign warehouses and consuls in its own port

*Use of its own currency accepted throughout the Mediterranean and its own

maritime laws

*

Republic

A republic, based on the Latin phrase ''res publica'' ('public affair' or 'people's affair'), is a State (polity), state in which Power (social and political), political power rests with the public (people), typically through their Representat ...

an government

*Participation in the

Crusades

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and at times directed by the Papacy during the Middle Ages. The most prominent of these were the campaigns to the Holy Land aimed at reclaiming Jerusalem and its surrounding t ...

and/or the crackdown on

piracy

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence by ship or boat-borne attackers upon another ship or a coastal area, typically with the goal of stealing cargo and valuable goods, or taking hostages. Those who conduct acts of piracy are call ...

Origins, affirmation and duration

The economic recovery that took place in

Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

starting with the

9th century, combined with hazardous mainland trading routes, enabled the development of major commercial routes along the Mediterranean coast. The growing autonomy acquired by some coastal cities gave them a leading role in this development. As many as six of these cities — Amalfi, Venice, Gaeta, Genoa, Ancona, and Ragusa — began their own history of autonomy and trade after being almost destroyed by terrible looting, or were founded by refugees from devastated lands. These cities, exposed to

pirate

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence by ship or boat-borne attackers upon another ship or a coastal area, typically with the goal of stealing cargo and valuable goods, or taking hostages. Those who conduct acts of piracy are call ...

raids and neglected by central powers, organized their own

defence autonomously, coupling the exercise of maritime trade with that of their armed protection. Thus, in the 9th, 10th, and 11th centuries, they were able to go on the offensive, obtaining numerous victories over the

Saracen

upright 1.5, Late 15th-century German woodcut depicting Saracens

''Saracen'' ( ) was a term used both in Greek and Latin writings between the 5th and 15th centuries to refer to the people who lived in and near what was designated by the Rom ...

s, starting with the historic

Battle of Ostia

The naval Battle of Ostia took place in 849 in the Tyrrhenian Sea between a Muslim fleet and an Italian league of Papal States, Papal, Duchy of Naples, Neapolitan, Duchy of Amalfi, Amalfitan, and Duchy of Gaeta, Gaetan ships. The battle ended in ...

in 849. The traffic of these cities reached Africa and Asia, effectively inserting itself between the

Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived the events that caused the fall of the Western Roman E ...

and

Islamic

Islam is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the Quran, and the teachings of Muhammad. Adherents of Islam are called Muslims, who are estimated to number Islam by country, 2 billion worldwide and are the world ...

maritime powers, with which a complex relationship of competition and collaboration was established for the control of the Mediterranean routes.

Each of the cities was favored by its geographical position, far from the main routes of passage of the armies and protected by mountains or

lagoon

A lagoon is a shallow body of water separated from a larger body of water by a narrow landform, such as reefs, barrier islands, barrier peninsulas, or isthmuses. Lagoons are commonly divided into ''coastal lagoons'' (or ''barrier lagoons'') an ...

s, which isolated it and allowed it to devote itself undisturbed to maritime traffic. This led to a gradual administrative autonomy and, in some cases, to total independence from the central powers, which for some time were no longer able to control the peripheral provinces: the Byzantine Empire, the

Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire, also known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation after 1512, was a polity in Central and Western Europe, usually headed by the Holy Roman Emperor. It developed in the Early Middle Ages, and lasted for a millennium ...

, and the

Papal States

The Papal States ( ; ; ), officially the State of the Church, were a conglomeration of territories on the Italian peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope from 756 to 1870. They were among the major states of Italy from the 8th c ...

. The forms of independence that were created in these cities were varied, and the modern approach to considering political relations, which clearly distinguishes between administrative autonomy and political freedom, makes it difficult to orient itself among them. For this reason, in the table below there are two dates relating to independence: one refers to the ''de facto'' freedom acquired, the other to that of law.

From an institutional point of view, in line with their municipal origins, the maritime cities were

oligarchic republics, generally governed, in a more or less declared manner, by the main

merchant

A merchant is a person who trades in goods produced by other people, especially one who trades with foreign countries. Merchants have been known for as long as humans have engaged in trade and commerce. Merchants and merchant networks operated i ...

families. The governments were therefore an expression of the merchant class, which constituted the backbone of their power. For this reason, these cities are sometimes referred to with the more generic term of "merchant republic". They were endowed with an articulated system of magistracies, with sometimes complementary, sometimes overlapping competences, which over the centuries showed a decided tendency to change - not without a certain degree of instability - and to centralize power. Thus the government became the privilege of the merchant nobility in Venice (from 1297) and the duke in Amalfi (from 945). However, even Gaeta, which never had a republican order, and Amalfi, which became a duchy in 945, are also called maritime republics, as the term republic should not be understood in its modern meaning: until

Machiavelli and

Kant

Immanuel Kant (born Emanuel Kant; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German philosopher and one of the central Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works in epistemology, metaphysics, et ...

, "republic" was synonymous with "State", and was not opposed to monarchy.

The

Crusades

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and at times directed by the Papacy during the Middle Ages. The most prominent of these were the campaigns to the Holy Land aimed at reclaiming Jerusalem and its surrounding t ...

offered the opportunity to expand trade. Amalfi, Genoa, Venice, Pisa, Ancona and Ragusa were already engaged in trade with the

Levant

The Levant ( ) is the subregion that borders the Eastern Mediterranean, Eastern Mediterranean sea to the west, and forms the core of West Asia and the political term, Middle East, ''Middle East''. In its narrowest sense, which is in use toda ...

, but with the Crusades thousands of inhabitants of the seaside cities poured into the East, creating warehouses, colonies and commercial establishments. They exercised great political influence at the local level: Italian merchants set up trade associations in their business centers with the aim of obtaining jurisdictional, fiscal and customs privileges from foreign governments.

[

Only Venice, Genoa and Pisa had territorial expansion overseas, i.e. they possessed large regions and numerous islands along the Mediterranean coasts. Genoa and Venice also came to dominate their entire region and part of the neighboring ones, becoming capitals of regional states. Venice was then the only one to dominate territories very far from the coast, up to occupying eastern Lombardy. Amalfi, Gaeta, Ancona, Ragusa and Noli, on the other hand, extended their dominion only to a part of the territory of their region, configuring themselves as city-states; however, all the republics had their own colonies and warehouses in the main Mediterranean ports, except Noli, which used those of the Genoese.

If the absence of a strong central authority had been the premise for the birth of the merchant republics, their end was vice versa due to the affirmation of a powerful centralized state. Usually independence could last as long as trade was able to ensure prosperity and wealth, but when these ceased, an economic decline was triggered, ending with the annexation, not necessarily violent, to a strong and organized state.

The longevity of the various maritime republics was quite varied: Venice had the longest life, from the ]High Middle Ages

The High Middle Ages, or High Medieval Period, was the periodization, period of European history between and ; it was preceded by the Early Middle Ages and followed by the Late Middle Ages, which ended according to historiographical convention ...

to the Napoleonic era

The Napoleonic era is a period in the history of France and history of Europe, Europe. It is generally classified as including the fourth and final stage of the French Revolution, the first being the National Assembly (French Revoluti ...

; Genoa and Ragusa also had a very long history, from the 1000s to the Napoleonic Age; Noli lasted as long, but stopped trading as early as the 15th century. However, Pisa and Ancona had a long life, remaining independent until the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

.[ Amalfi and Gaeta were instead the first to fall, having been conquered by the Normans in the 12th century.

]

Number of maritime republics over the centuries

As highlighted in the following chronological table, the number of maritime republics has changed over the centuries, as follows:

*9th–10th century: There are only three maritime republics, namely Amalfi, Gaeta and Venice.

*11th century: By adding Ancona, Genoa, Pisa and Ragusa in the first decades, there are seven maritime republics; however, the century also saw the end of Amalfi's independence (1031) and the beginning of Noli's maritime history.

*12th–14th century: With the end of Gaeta's independence (1137), there are six active maritime republics.

*15th century: With Pisa's loss of independence and the end of Noli's maritime activity, four maritime republics remain, namely Ancona, Genoa, Ragusa, and Venice.

*16th–18th century: With Ancona's loss of autonomy, the three longest-lived maritime republics remain active: Genoa, Ragusa and Venice.

ImageSize = width:1100 height:auto barincrement:20

PlotArea = top:10 bottom:50 right:130 left:20

AlignBars = late

DateFormat = yyyy

Period = from:800 till:1850

TimeAxis = orientation:horizontal

ScaleMajor = unit:year increment:100 start:800

Colors =

id:Amalfi value:rgb(0.4,0,1) legend: Amalfi

id:Ancona value:rgb(1,0.9,0.1) legend: Ancona

id:Gaeta value:rgb(0.3,1,0.3) legend: Gaeta

id:Genoa value:rgb(1,0.6,0) legend: Genoa

id:Pisa value:rgb(0.3,0.8,1) legend: Pisa

id:Ragusa value:rgb(0.7,0.2,1) legend: Ragusa

id:Venice value:rgb(1,0.1,0.1) legend: Venice

id:Noli value:rgb(0.2,0.5,0) legend: Noli

Legend = columns:4 left:150 top:24 columnwidth:200

TextData =

pos:(20,27) textcolor:black fontsize:M

text:

BarData =

barset:PM

PlotData=

width:5 align:left fontsize:S shift:(5,-4) anchor:till

barset:PM

from:839 till:1131 color:Amalfi text:"Amalfi

Amalfi (, , ) is a town and ''comune'' in the province of Salerno, in the region of Campania, Italy, on the Gulf of Salerno. It lies at the mouth of a deep ravine, at the foot of Monte Cerreto (1,315 metres, 4,314 feet), surrounded by dramatic c ...

" fontsize:10

from:1050 till:1532 color:Ancona text:"Ancona

Ancona (, also ; ) is a city and a seaport in the Marche region of central Italy, with a population of around 101,997 . Ancona is the capital of the province of Ancona, homonymous province and of the region. The city is located northeast of Ro ...

" fontsize:10

from:839 till:1137 color:Gaeta text:"Gaeta

Gaeta (; ; Southern Latian dialect, Southern Laziale: ''Gaieta'') is a seaside resort in the province of Latina in Lazio, Italy. Set on a promontory stretching towards the Gulf of Gaeta, it is from Rome and from Naples.

The city has played ...

" fontsize:10

from:1005 till:1797 color:Genoa text:"Genoa

Genoa ( ; ; ) is a city in and the capital of the Italian region of Liguria, and the sixth-largest city in Italy. As of 2025, 563,947 people live within the city's administrative limits. While its metropolitan city has 818,651 inhabitan ...

" fontsize:10

from:1050 till:1406 color:Pisa text:"Pisa

Pisa ( ; ) is a city and ''comune'' (municipality) in Tuscany, Central Italy, straddling the Arno just before it empties into the Ligurian Sea. It is the capital city of the Province of Pisa. Although Pisa is known worldwide for the Leaning Tow ...

" fontsize:10

from:1050 till:1808 color:Ragusa text:" Ragusa" fontsize:10

from:840 till:1797 color:Venice text:"Venice

Venice ( ; ; , formerly ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 islands that are separated by expanses of open water and by canals; portions of the city are li ...

" fontsize:10

from:1192 till:1500 color:Noli text:" Noli" fontsize:10

Rises, golden periods, and declines

The following table compares the different duration of the maritime republics, their golden periods (indicated with more intense colours), and the periods of rise and decline (more or less light colours), determined by the wars won or lost, the commercial colonies in the Mediterranean, economic power, territorial possessions, and periods of temporary subjection to foreign powers. A different colour has been used for Noli to indicate the period of its incomplete independence. The dates placed at the beginning and at the end of each time line respectively indicate the year in which autonomy began and ended; any intermediate date indicates the year in which ''de facto'' independence passed to ''de jure'' independence. The notes refer to periods of temporary loss of freedom.

Importance of the maritime republics

The maritime republics reestablished contacts between Europe, Asia and Africa, which were almost interrupted after the fall of the Western Roman Empire

The fall of the Western Roman Empire, also called the fall of the Roman Empire or the fall of Rome, was the loss of central political control in the Western Roman Empire, a process in which the Empire failed to enforce its rule, and its vast ...

; their history is intertwined both with the launch of European expansion towards the East and with the origins of modern capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by ...

as a mercantile and financial system. In these cities, gold coin

A gold coin is a coin that is made mostly or entirely of gold. Most gold coins minted since 1800 are 90–92% gold (22fineness#Karat, karat), while most of today's gold bullion coins are pure gold, such as the Britannia (coin), Britannia, Canad ...

s, which had not been used for centuries, were minted, new exchange and accounting practices were developed, and thus international finance and commercial law

Commercial law (or business law), which is also known by other names such as mercantile law or trade law depending on jurisdiction; is the body of law that applies to the rights, relations, and conduct of Legal person, persons and organizations ...

were born.

Technological advances in navigation

Navigation is a field of study that focuses on the process of monitoring and controlling the motion, movement of a craft or vehicle from one place to another.Bowditch, 2003:799. The field of navigation includes four general categories: land navig ...

were also encouraged; important in this regard was the improvement and diffusion of the compass

A compass is a device that shows the cardinal directions used for navigation and geographic orientation. It commonly consists of a magnetized needle or other element, such as a compass card or compass rose, which can pivot to align itself with No ...

by the Amalfi people and the Venetian invention of the great galley. Navigation owes much to the maritime republics as regards nautical cartography: the maps of the 14th and 15th centuries that are still in use today all belong to the schools of Genoa, Venice, and Ancona.

From the East, the maritime republics imported a vast range of goods unobtainable in Europe, which they then resold in other cities of Italy and central and northern Europe, creating a commercial triangle between the Arab East, the Byzantine Empire, and Italy. Until the discovery of America they were therefore essential nodes of trade between Europe and the other continents.

Among the most important products were:

*Medicines: aloe vera

''Aloe vera'' () is a succulent plant species of the genus ''Aloe''. It is widely distributed, and is considered an invasive species in many world regions.

An evergreen perennial plant, perennial, it originates from the Arabian Peninsula, but ...

, balsam, ginger

Ginger (''Zingiber officinale'') is a flowering plant whose rhizome, ginger root or ginger, is widely used as a spice and a folk medicine. It is an herbaceous perennial that grows annual pseudostems (false stems made of the rolled bases of l ...

, camphor

Camphor () is a waxy, colorless solid with a strong aroma. It is classified as a terpenoid and a cyclic ketone. It is found in the wood of the camphor laurel (''Cinnamomum camphora''), a large evergreen tree found in East Asia; and in the kapu ...

, laudanum, cardamom

Cardamom (), sometimes cardamon or cardamum, is a spice made from the seeds of several plants in the genus (biology), genera ''Elettaria'' and ''Amomum'' in the family Zingiberaceae. Both genera are native to the Indian subcontinent and Indon ...

, rhubarb, astragalus

Astragalus may refer to:

* ''Astragalus'' (plant), a large genus of herbs and small shrubs

*Astragalus (bone)

The talus (; Latin for ankle or ankle bone; : tali), talus bone, astragalus (), or ankle bone is one of the group of foot bones known ...

*Spice

In the culinary arts, a spice is any seed, fruit, root, Bark (botany), bark, or other plant substance in a form primarily used for flavoring or coloring food. Spices are distinguished from herbs, which are the leaves, flowers, or stems of pl ...

s: black pepper

Black pepper (''Piper nigrum'') is a flowering vine in the family Piperaceae, cultivated for its fruit (the peppercorn), which is usually dried and used as a spice and seasoning. The fruit is a drupe (stonefruit) which is about in diameter ...

, clove

Cloves are the aromatic flower buds of a tree in the family Myrtaceae, ''Syzygium aromaticum'' (). They are native to the Maluku Islands, or Moluccas, in Indonesia, and are commonly used as a spice, flavoring, or Aroma compound, fragrance in fin ...

s, nutmeg

Nutmeg is the seed, or the ground spice derived from the seed, of several tree species of the genus '' Myristica''; fragrant nutmeg or true nutmeg ('' M. fragrans'') is a dark-leaved evergreen tree cultivated for two spices derived from its fru ...

, cinnamon

Cinnamon is a spice obtained from the inner bark of several tree species from the genus ''Cinnamomum''. Cinnamon is used mainly as an aromatic condiment and flavouring additive in a wide variety of cuisines, sweet and savoury dishes, biscuits, b ...

, white sugar

White sugar, also called table sugar, granulated sugar, or regular sugar, is a commonly used type of sugar, made either of beet sugar or cane sugar, which has undergone a refining process. It is nearly pure sucrose.

Description

The refini ...

*Perfumes and odorous substances to burn: musk, mastic, sandalwood

Sandalwood is a class of woods from trees in the genus ''Santalum''. The woods are heavy, yellow, and fine-grained, and, unlike many other aromatic woods, they retain their fragrance for decades. Sandalwood oil is extracted from the woods. Sanda ...

, incense

Incense is an aromatic biotic material that releases fragrant smoke when burnt. The term is used for either the material or the aroma. Incense is used for aesthetic reasons, religious worship, aromatherapy, meditation, and ceremonial reasons. It ...

, ambergris

*Dyes: indigo

InterGlobe Aviation Limited (d/b/a IndiGo), is an India, Indian airline headquartered in Gurgaon, Haryana, India. It is the largest List of airlines of India, airline in India by passengers carried and fleet size, with a 64.1% domestic market ...

, alum

An alum () is a type of chemical compound, usually a hydrated double salt, double sulfate salt (chemistry), salt of aluminium with the general chemical formula, formula , such that is a valence (chemistry), monovalent cation such as potassium ...

, carmine

Carmine ()also called cochineal (when it is extracted from the Cochineal, cochineal insect), cochineal extract, crimson Lake pigment, lake, or carmine lake is a pigment of a bright-red color obtained from the aluminium coordination complex, compl ...

, varnish

Varnish is a clear Transparency (optics), transparent hard protective coating or film. It is not to be confused with wood stain. It usually has a yellowish shade due to the manufacturing process and materials used, but it may also be pigmente ...

*Textiles: silk

Silk is a natural fiber, natural protein fiber, some forms of which can be weaving, woven into textiles. The protein fiber of silk is composed mainly of fibroin and is most commonly produced by certain insect larvae to form cocoon (silk), c ...

, Egyptian linen

Linen () is a textile made from the fibers of the flax plant.

Linen is very strong and absorbent, and it dries faster than cotton. Because of these properties, linen is comfortable to wear in hot weather and is valued for use in garments. Lin ...

, sambe, brocade

Brocade () is a class of richly decorative shuttle (weaving), shuttle-woven fabrics, often made in coloured silks and sometimes with gold and silver threads. The name, related to the same root as the word "broccoli", comes from Italian langua ...

, velvet

Velvet is a type of woven fabric with a dense, even pile (textile), pile that gives it a distinctive soft feel. Historically, velvet was typically made from silk. Modern velvet can be made from silk, linen, cotton, wool, synthetic fibers, silk ...

, damask

Damask (; ) is a woven, Reversible garment, reversible patterned Textile, fabric. Damasks are woven by periodically reversing the action of the warp and weft threads. The pattern is most commonly created with a warp-faced satin weave and the gro ...

, carpet

A carpet is a textile floor covering typically consisting of an upper layer of Pile (textile), pile attached to a backing. The pile was traditionally made from wool, but since the 20th century synthetic fiber, synthetic fibres such as polyprop ...

s

*Luxury products: gemstone

A gemstone (also called a fine gem, jewel, precious stone, semiprecious stone, or simply gem) is a piece of mineral crystal which, when cut or polished, is used to make jewellery, jewelry or other adornments. Certain Rock (geology), rocks (such ...

s, precious coral, pearl

A pearl is a hard, glistening object produced within the soft tissue (specifically the mantle (mollusc), mantle) of a living Exoskeleton, shelled mollusk or another animal, such as fossil conulariids. Just like the shell of a mollusk, a pear ...

s, ivory

Ivory is a hard, white material from the tusks (traditionally from elephants) and Tooth, teeth of animals, that consists mainly of dentine, one of the physical structures of teeth and tusks. The chemical structure of the teeth and tusks of mamm ...

, porcelain

Porcelain (), also called china, is a ceramic material made by heating Industrial mineral, raw materials, generally including kaolinite, in a kiln to temperatures between . The greater strength and translucence of porcelain, relative to oth ...

, gold and silver threads

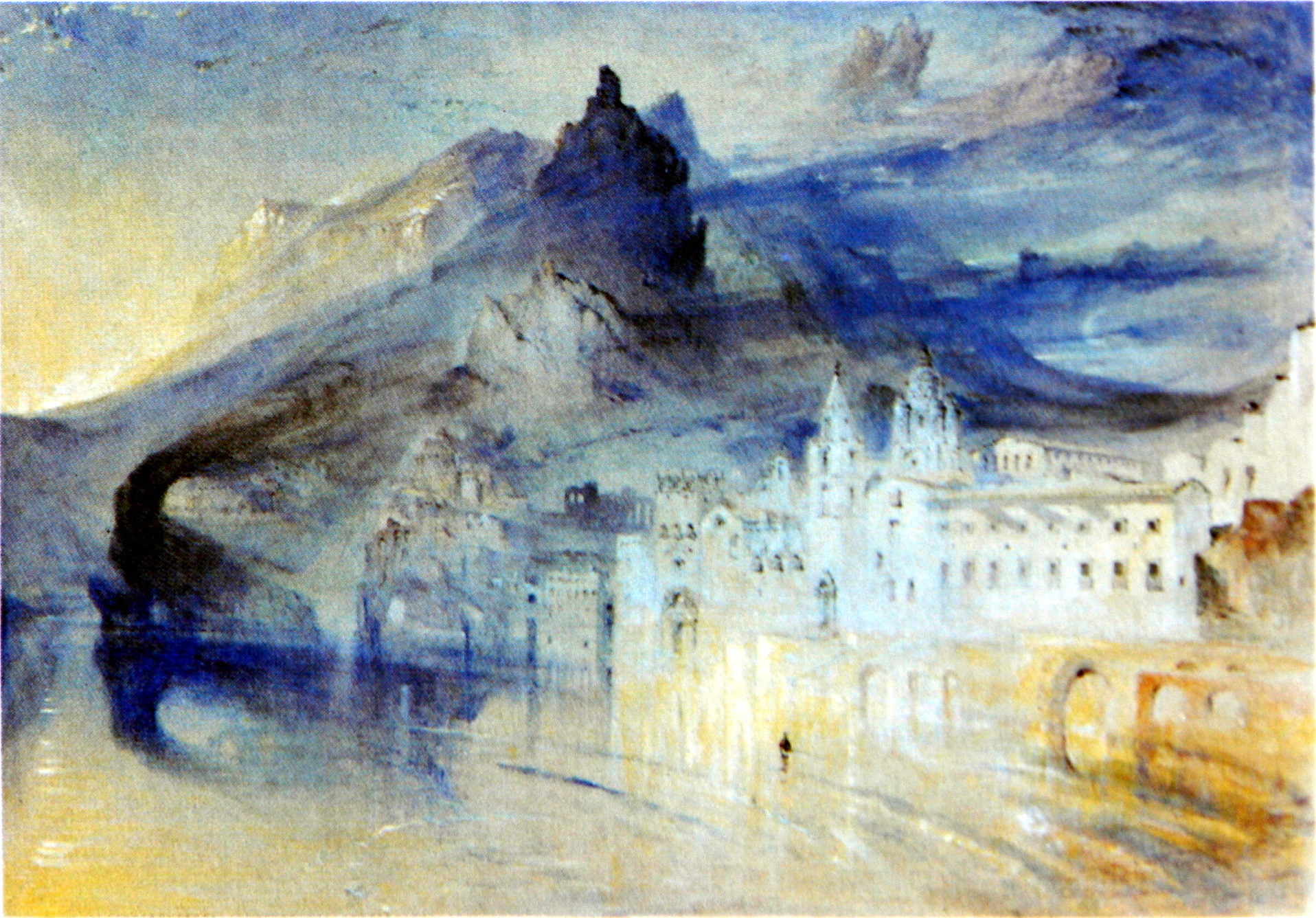

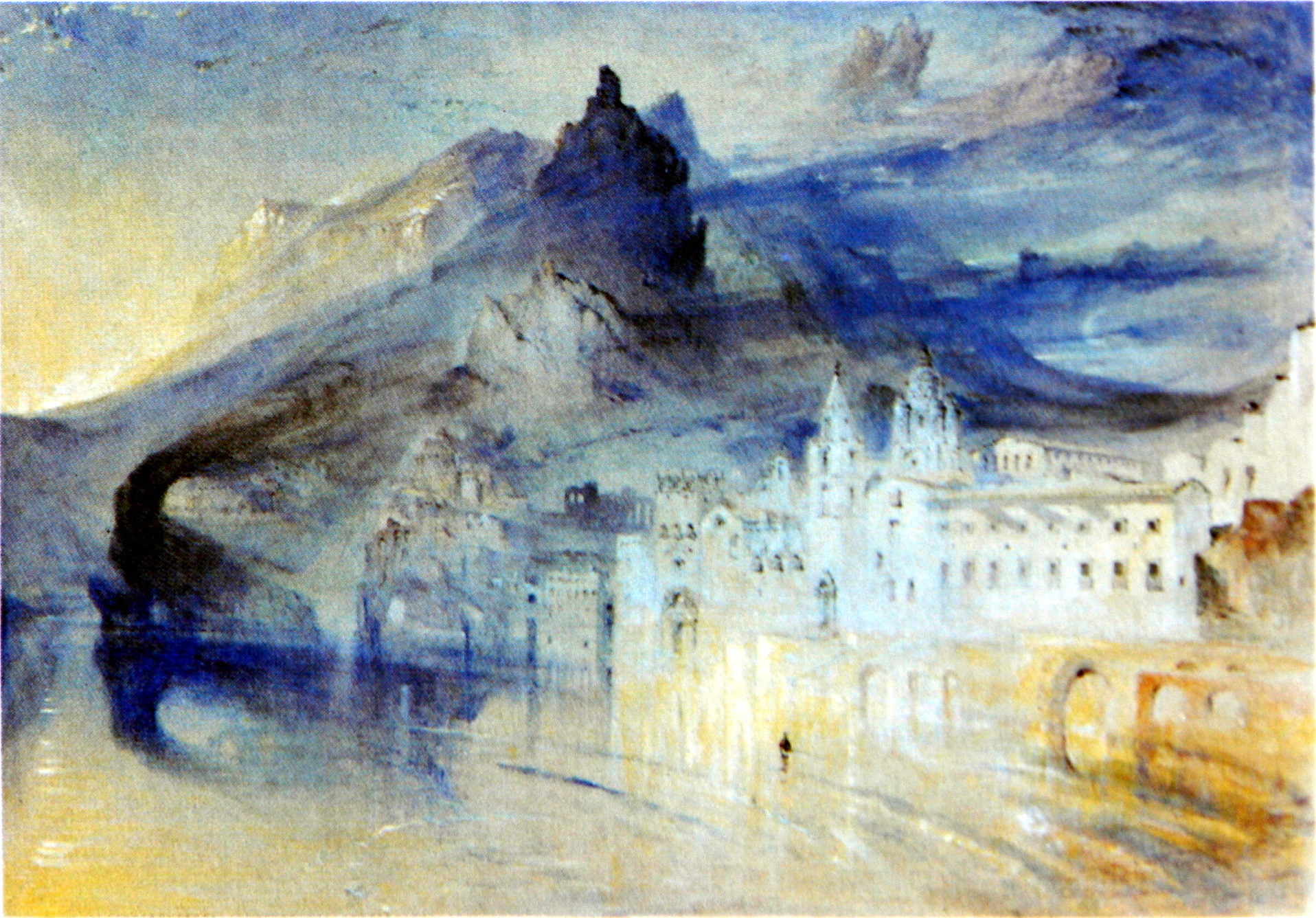

The maritime republics' great prosperity deriving from trade had a significant impact on the history of art, to the point that five of them (Amalfi, Genoa, Venice, Pisa and Ragusa) are today included in UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO ) is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) with the aim of promoting world peace and International secur ...

's list of World Heritage Site

World Heritage Sites are landmarks and areas with legal protection under an treaty, international treaty administered by UNESCO for having cultural, historical, or scientific significance. The sites are judged to contain "cultural and natural ...

s. Although an artistic current common to all of them and exclusive to them cannot be described, a characterizing trait was the mixture of elements of the various Mediterranean artistic traditions, mainly Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived the events that caused the fall of the Western Roman E ...

, Islamic

Islam is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the Quran, and the teachings of Muhammad. Adherents of Islam are called Muslims, who are estimated to number Islam by country, 2 billion worldwide and are the world ...

and Romanesque elements.

The modern Italian communities living in Greece, Turkey, Lebanon

Lebanon, officially the Republic of Lebanon, is a country in the Levant region of West Asia. Situated at the crossroads of the Mediterranean Basin and the Arabian Peninsula, it is bordered by Syria to the north and east, Israel to the south ...

, Gibraltar

Gibraltar ( , ) is a British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory and British overseas cities, city located at the southern tip of the Iberian Peninsula, on the Bay of Gibraltar, near the exit of the Mediterranean Sea into the A ...

, and Crimea

Crimea ( ) is a peninsula in Eastern Europe, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, almost entirely surrounded by the Black Sea and the smaller Sea of Azov. The Isthmus of Perekop connects the peninsula to Kherson Oblast in mainland Ukrain ...

descend, at least in part, from the colonies of the maritime republics, as well as the language island of the Tabarchino dialect in Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; ; ) is the Mediterranean islands#By area, second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, and one of the Regions of Italy, twenty regions of Italy. It is located west of the Italian Peninsula, north of Tunisia an ...

and the extinct Italian community of Odesa.

History of individual republics

Amalfi

Amalfi

Amalfi (, , ) is a town and ''comune'' in the province of Salerno, in the region of Campania, Italy, on the Gulf of Salerno. It lies at the mouth of a deep ravine, at the foot of Monte Cerreto (1,315 metres, 4,314 feet), surrounded by dramatic c ...

, the first maritime republic to reach a leading importance, acquired ''de facto'' independence from the Duchy of Naples

The Duchy of Naples (, ) began as a Byzantine province that was constituted in the seventh century, in the lands roughly corresponding to the current province of Naples that the Lombards had not conquered during their invasion of Italy in the si ...

in 839

__NOTOC__

Year 839 ( DCCCXXXIX) was a common year starting on Wednesday of the Julian calendar.

Events

By place Europe

* Prince Sicard of Benevento is assassinated by a conspiracy among the nobility. He is succeeded by Radelchis I, c ...

. That year, Sicard of Benevento

Sicard (died 839) was the Prince of Benevento from 832. He was the last prince of a united Benevento which covered most of the Mezzogiorno. On his death, the principality descended into civil war which split it permanently (except for very bri ...

, during a war against the Byzantines, conquered the city, and deported the population. When he died in a palace conspiracy, the Amalfi people rebelled, drove out the Lombard garrison and formed the free republic of Amalfi. The people of Amalfi were governed by a republican order governed by '' comites'', under which the ''praefecturii'' were in charge until 945, when Mastalus II assumed power and proclaimed himself duke

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of Royal family, royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and above sovereign princes. As royalty or nobi ...

.

As early as the end of the 9th century, the duchy developed extensive trade with the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived History of the Roman Empire, the events that caused the ...

and Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

. Amalfitan merchants wrested the Mediterranean trade monopoly from the Arabs and founded mercantile bases in Southern Italy

Southern Italy (, , or , ; ; ), also known as () or (; ; ; ), is a macroregion of Italy consisting of its southern Regions of Italy, regions.

The term "" today mostly refers to the regions that are associated with the people, lands or cultu ...

, North Africa

North Africa (sometimes Northern Africa) is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region. However, it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of t ...

and the Middle East

The Middle East (term originally coined in English language) is a geopolitical region encompassing the Arabian Peninsula, the Levant, Turkey, Egypt, Iran, and Iraq.

The term came into widespread usage by the United Kingdom and western Eur ...

in the 10th century. In the 11th century, Amalfi reached the height of its maritime power and had warehouses in Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

, Laodicea, Beirut

Beirut ( ; ) is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Lebanon. , Greater Beirut has a population of 2.5 million, just under half of Lebanon's population, which makes it the List of largest cities in the Levant region by populatio ...

, Jaffa

Jaffa (, ; , ), also called Japho, Joppa or Joppe in English, is an ancient Levantine Sea, Levantine port city which is part of Tel Aviv, Tel Aviv-Yafo, Israel, located in its southern part. The city sits atop a naturally elevated outcrop on ...

, Tripoli of Syria, Cyprus

Cyprus (), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Situated in West Asia, its cultural identity and geopolitical orientation are overwhelmingly Southeast European. Cyprus is the List of isl ...

, Alexandria

Alexandria ( ; ) is the List of cities and towns in Egypt#Largest cities, second largest city in Egypt and the List of coastal settlements of the Mediterranean Sea, largest city on the Mediterranean coast. It lies at the western edge of the Nile ...

, Ptolemais, Baghdad

Baghdad ( or ; , ) is the capital and List of largest cities of Iraq, largest city of Iraq, located along the Tigris in the central part of the country. With a population exceeding 7 million, it ranks among the List of largest cities in the A ...

, and India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

.

Amalfi's land borders extended from the Sarno River to Vietri sul Mare, while to the west it bordered the Duchy of Sorrento

The Duchy of Sorrento was a small peninsular duchy of the Early Middle Ages centred on the Italian city of Sorrento.

Established in the 7th century as a fief of the Duchy of Naples, at the time still part of the Byzantine Empire.

Subsequently ...

; it also owned Capri

Capri ( , ; ) is an island located in the Tyrrhenian Sea off the Sorrento Peninsula, on the south side of the Gulf of Naples in the Campania region of Italy. A popular resort destination since the time of the Roman Republic, its natural beauty ...

, donated by the Byzantines as a reward for having defeated the Saracen

upright 1.5, Late 15th-century German woodcut depicting Saracens

''Saracen'' ( ) was a term used both in Greek and Latin writings between the 5th and 15th centuries to refer to the people who lived in and near what was designated by the Rom ...

s at San Salvatore in 872. Furthermore, for only three years (from 831 to 833), the dukes Manso I and John I John I may refer to:

People

Religious figures

* John I (bishop of Jerusalem)

* John Chrysostom (349 – c. 407), Patriarch of Constantinople

* John I of Antioch (died 441)

* Pope John I of Alexandria, Coptic Pope from 496 to 505

* Pope John I, P ...

also had control of the Principality of Salerno

The Principality of Salerno () was a Middle Ages, medieval Mezzogiorno, Southern Italian state, formed in 851 out of the Principality of Benevento after a decade-long civil war. It was centred on the port city of Salerno. Although it owed alle ...

, including the whole of Lucania

Lucania was a historical region of Southern Italy, corresponding to the modern-day region of Basilicata. It was the land of the Lucani, an Oscan people. It extended from the Tyrrhenian Sea to the Gulf of Taranto. It bordered with Samnium and ...

. The Amalfi fleet helped to free the Tyrrhenian Sea

The Tyrrhenian Sea (, ; or ) , , , , is part of the Mediterranean Sea off the western coast of Italy. It is named for the Tyrrhenians, Tyrrhenian people identified with the Etruscans of Italy.

Geography

The sea is bounded by the islands of C ...

from Saracen pirates, defeating them at Licosa (846), at Ostia (849), and on the Garigliano (915).

At the dawn of AD 1000, Amalfi was the most prosperous city of Longobardia, and in terms of population (probably 80,000 inhabitants) and prosperity, the only one able to compete with the great Arab metropolises: it minted its own gold coin, the tarì, which was current in all the main Mediterranean ports; the Amalfian Laws

The Amalfian Laws are a code of maritime laws compiled in the 12th century in Amalfi, a town in Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Ita ...

, a code of maritime law which remained in force throughout the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

, date back to that time; in Jerusalem, the noble merchant Mauro Pantaleone built the hospital from which the Knights Hospitaller

The Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem, commonly known as the Knights Hospitaller (), is a Catholic military order. It was founded in the crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem in the 12th century and had headquarters there ...

would originate.

The far-sighted dukes of Amalfi were able to safeguard their power over the centuries, allying themselves, depending on the circumstances, with the Byzantines, the Pope, or the Muslims.

On the basis of an erroneous reading of a passage by the humanist Flavio Biondo, the invention of the compass

A compass is a device that shows the cardinal directions used for navigation and geographic orientation. It commonly consists of a magnetized needle or other element, such as a compass card or compass rose, which can pivot to align itself with No ...

was long attributed to Flavio Gioja from Amalfi. Despite the tenacious tradition that originated, a correct reading of Biondo's passage reveals that Flavio Gioia never existed, and that the glory of the Amalfi people was not that of inventing the compass (actually imported from China), but of having been the first to spread its use in Europe.

The close bond that tied the city of Amalfi to the East is also testified by the art that flourished in the centuries of independence and in which Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived the events that caused the fall of the Western Roman E ...

and Arab-Norman influences harmoniously merged.

Towards the middle of the 11th century, the power of the duchy began to fade: in 1039, due to internal strife, it was conquered by Guaimar IV of Salerno

Guaimar IV (c. 1013 – 2, 3 or 4 June 1052) was Prince of Salerno (1027–1052), Duke of Amalfi (1039–1052), Duke of Gaeta (1040–1041), and Prince of Capua (1038–1047) in Southern Italy over the period from 1027 to 1052. ...

, who would be expelled in 1052 by his brother John II. In 1073, Robert Guiscard

Robert Guiscard ( , ; – 17 July 1085), also referred to as Robert de Hauteville, was a Normans, Norman adventurer remembered for his Norman conquest of southern Italy, conquest of southern Italy and Sicily in the 11th century.

Robert was born ...

, summoned by the Amalfi people against Salerno, conquered the duchy. Amalfi remained substantially autonomous and often rebelled against the regents until 1100, when the last duke Marinus Sebastus was deposed by the Normans. This left Amalfi only an administrative autonomy, later revoked in 1131 by Roger II of Sicily

Roger II or Roger the Great (, , Greek language, Greek: Ρογέριος; 22 December 1095 – 26 February 1154) was King of Kingdom of Sicily, Sicily and Kingdom of Africa, Africa, son of Roger I of Sicily and successor to his brother Simon, C ...

. After the Norman conquest, the decline was not immediate, becoming in the meantime a seaport of the Norman-Swabian state. However, the commercial basin of Amalfi was reduced to the western Mediterranean and gradually the city was supplanted, locally by Naples and Salerno, and at the Mediterranean level by Pisa, Venice and Genoa.

Genoa

Genoa

Genoa ( ; ; ) is a city in and the capital of the Italian region of Liguria, and the sixth-largest city in Italy. As of 2025, 563,947 people live within the city's administrative limits. While its metropolitan city has 818,651 inhabitan ...

had revived at the dawn of the 10th century when, following the city's destruction by the Saracens, its inhabitants returned to the sea. In the mid-10th century, entering the dispute between Berengar II and Otto the Great

Otto I (23 November 912 – 7 May 973), known as Otto the Great ( ) or Otto of Saxony ( ), was East Frankish ( German) king from 936 and Holy Roman Emperor from 962 until his death in 973. He was the eldest son of Henry the Fowler and Matilda ...

, it obtained ''de facto'' independence in 958, which was then made official in 1096 with the creation of the ''Compagna Communis'', a union of merchants and feudal lords of the area.

Meanwhile, its alliance with Pisa allowed the liberation of the western Mediterranean from Saracen pirates. The fortunes of the municipality increased considerably thanks to its participation in the First Crusade

The First Crusade (1096–1099) was the first of a series of religious wars, or Crusades, initiated, supported and at times directed by the Latin Church in the Middle Ages. The objective was the recovery of the Holy Land from Muslim conquest ...

, which procured great privileges for the Genoese colonists in the Holy Land

The term "Holy Land" is used to collectively denote areas of the Southern Levant that hold great significance in the Abrahamic religions, primarily because of their association with people and events featured in the Bible. It is traditionall ...

.

The apogee of Genoese fortunes came in the 13th century, following the Treaty of Nymphaeum (1261) and the double victory over Pisa ( Battle of Meloria (1284)) and Venice (Battle of Curzola

The Battle of Curzola (today Korčula, southern Dalmatia, now in Croatia) was a naval battle fought on 9 September 1298 between the Genoese navy, Genoese and Venetian navy, Venetian navies. It was a disaster for Venice, a major setback among the ...

(1298)). "The Superb", a name for the city derived from Petrarch

Francis Petrarch (; 20 July 1304 – 19 July 1374; ; modern ), born Francesco di Petracco, was a scholar from Arezzo and poet of the early Italian Renaissance, as well as one of the earliest Renaissance humanism, humanists.

Petrarch's redis ...

's work ''Itinerarium breve de Ianua ad Ierusalem'' (1358) in which he described it, dominated the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern Eur ...

and the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal sea, marginal Mediterranean sea (oceanography), mediterranean sea lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bound ...

and controlled a large part of Liguria

Liguria (; ; , ) is a Regions of Italy, region of north-western Italy; its Capital city, capital is Genoa. Its territory is crossed by the Alps and the Apennine Mountains, Apennines Mountain chain, mountain range and is roughly coextensive with ...

, Corsica

Corsica ( , , ; ; ) is an island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the Regions of France, 18 regions of France. It is the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fourth-largest island in the Mediterranean and lies southeast of the Metro ...

, the Sardinian Judicate of Logudoro

The Judicate of Logudoro or Torres ( or ''Torres'', ''Rennu de Logudoro'' or ''Logu de Torres'') was one of the Sardinian medieval kingdoms, four kingdoms or ''iudicati'' into which Sardinia was divided during the Middle Ages. It occupied the nor ...

, the North Aegean

The North Aegean Region (, ) is one of the thirteen administrative regions of Greece, and the smallest of the thirteen by population. It comprises the islands of the north-eastern Aegean Sea, called the North Aegean islands, except for Thasos an ...

, and southern Crimea

Crimea ( ) is a peninsula in Eastern Europe, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, almost entirely surrounded by the Black Sea and the smaller Sea of Azov. The Isthmus of Perekop connects the peninsula to Kherson Oblast in mainland Ukrain ...

.

The 14th century marked a serious economic, political and social crisis for Genoa, which, weakened by internal strife, lost Sardinia to the Aragonese, was defeated by Venice at Alghero

Alghero (; ; ; ) is a city of about 45,000 inhabitants in the Italian province of Sassari in the north west of the island of Sardinia, next to the Mediterranean Sea. The city's name comes from ''Aleguerium'', which is a mediaeval Latin word m ...

(1353) and Chioggia (1379) and subjected several times to France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

and to the Duchy of Milan

The Duchy of Milan (; ) was a state in Northern Italy, created in 1395 by Gian Galeazzo Visconti, then the lord of Milan, and a member of the important Visconti of Milan, Visconti family, which had been ruling the city since 1277. At that time, ...

. The republic was weakened by the state's own arrangement, which, based on private agreements between the main families, led to incredibly short and unstable governments and very frequent factional strife.

Following the plagues and foreign dominations of the 14th and 15th centuries, the city experienced a second apogee upon regaining self-government in 1528 through the efforts of Andrea Doria

Andrea Doria, Prince of Melfi (; ; 30 November 146625 November 1560) was an Italian statesman, ', and admiral, who played a key role in the Republic of Genoa during his lifetime.

From 1528 until his death, Doria exercised a predominant influe ...

, to the point that the following century was called ''El siglo de los Genoveses''. This definition was not due to maritime trade, but to the impressive banking penetration lent by the Bank of Saint George

The Bank of Saint George ( or informally as ''Ufficio di San Giorgio'' or ''Banco'') was a financial institution of the Republic of Genoa. It was founded on 23 April 1407 to consolidate the public debt, which had been escalating due to the war ...

, which made it an authentic world economic power: several European monarchies, such as Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

, were tied to loans from Genoese bankers and its currency, the genovino, became one of the most important in the world.

However, the republic was then only independent ''de jure'', because it found itself under the influence of the main neighboring powers, first the French and the Spanish, then the Austrians and the Savoys. The republic collapsed following Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

's first Italian campaign: becoming the Ligurian Republic in 1797, it was annexed to France in 1805 with the second Italian campaign. In 1815, the Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon, Napol ...

decreed Genoa's annexation to the Kingdom of Sardinia

The Kingdom of Sardinia, also referred to as the Kingdom of Sardinia and Corsica among other names, was a State (polity), country in Southern Europe from the late 13th until the mid-19th century, and from 1297 to 1768 for the Corsican part of ...

.

The artistic importance of Genoa has been recognized by UNESCO by listing the ''Strade Nuove'' and the complex of the ''Palazzi dei Rolli'' among the World Heritage Site

World Heritage Sites are landmarks and areas with legal protection under an treaty, international treaty administered by UNESCO for having cultural, historical, or scientific significance. The sites are judged to contain "cultural and natural ...

s. The indissoluble link between Genoa and navigation is testified by Lancelotto Malocello, by Vandino and Ugolino Vivaldi, and most prominently by Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus (; between 25 August and 31 October 1451 – 20 May 1506) was an Italians, Italian explorer and navigator from the Republic of Genoa who completed Voyages of Christopher Columbus, four Spanish-based voyages across the At ...

.

Pisa

The Republic of Pisa was born in the 11th century. In this historical period, Pisa intensified its trade in the Mediterranean Sea, allied itself with the

The Republic of Pisa was born in the 11th century. In this historical period, Pisa intensified its trade in the Mediterranean Sea, allied itself with the Kingdom of Sicily

The Kingdom of Sicily (; ; ) was a state that existed in Sicily and the southern Italian peninsula, Italian Peninsula as well as, for a time, in Kingdom of Africa, Northern Africa, from its founding by Roger II of Sicily in 1130 until 1816. It was ...

's nascent power, and clashed several times with the Saracen ships, defeating them in Reggio Calabria

Reggio di Calabria (; ), commonly and officially referred to as Reggio Calabria, or simply Reggio by its inhabitants, is the List of cities in Italy, largest city in Calabria as well as the seat of the Metropolitan City of Reggio Calabria. As ...

(1005), in Bona (1034), in Palermo

Palermo ( ; ; , locally also or ) is a city in southern Italy, the capital (political), capital of both the autonomous area, autonomous region of Sicily and the Metropolitan City of Palermo, the city's surrounding metropolitan province. The ...

(1064), and in Mahdia

Mahdia ( ') is a Tunisian coastal city with 76,513 inhabitants, south of Monastir, Tunisia, Monastir and southeast of Sousse.

Mahdia is a provincial centre north of Sfax. It is important for the associated fish-processing industry, as well as w ...

(1087).

Originally, Pisa was governed by a Viscount, whose power was limited by the Bishop. In the 11th century, entering into the struggles between these two powers, the city, governed by a Council of Elders, acquired a ''de facto'' autonomy, which was then made official by Henry IV in 1081.

In 1016, an alliance of Pisa and Genoa defeated the Saracens, conquered Corsica and the Sardinian judicates of Cagliari

Cagliari (, , ; ; ; Latin: ''Caralis'') is an Comune, Italian municipality and the capital and largest city of the island of Sardinia, an Regions of Italy#Autonomous regions with special statute, autonomous region of Italy. It has about 146,62 ...

and Gallura, and acquired control of the Tyrrhenian Sea

The Tyrrhenian Sea (, ; or ) , , , , is part of the Mediterranean Sea off the western coast of Italy. It is named for the Tyrrhenians, Tyrrhenian people identified with the Etruscans of Italy.

Geography

The sea is bounded by the islands of C ...

; a century later they took the Balearic Islands

The Balearic Islands are an archipelago in the western Mediterranean Sea, near the eastern coast of the Iberian Peninsula. The archipelago forms a Provinces of Spain, province and Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Spain, ...

. At the same time, Pisa's economic and political power increased considerably with the commercial rights acquired with the Crusades

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and at times directed by the Papacy during the Middle Ages. The most prominent of these were the campaigns to the Holy Land aimed at reclaiming Jerusalem and its surrounding t ...

, thanks to which it was able to establish numerous warehouses in the Holy Land. Pisa was always the most fervent supporter of the Ghibelline cause, thus opposing the Guelphs Genoa, Noli, Lucca

Città di Lucca ( ; ) is a city and ''comune'' in Tuscany, Central Italy, on the Serchio River, in a fertile plain near the Ligurian Sea. The city has a population of about 89,000, while its Province of Lucca, province has a population of 383,9 ...

and Florence

Florence ( ; ) is the capital city of the Italy, Italian region of Tuscany. It is also the most populated city in Tuscany, with 362,353 inhabitants, and 989,460 in Metropolitan City of Florence, its metropolitan province as of 2025.

Florence ...

: its currency, the aquiline, always bore the name of the emperor

The word ''emperor'' (from , via ) can mean the male ruler of an empire. ''Empress'', the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife (empress consort), mother/grandmother (empress dowager/grand empress dowager), or a woman who rules ...

.

Pisa reached the peak of its splendor between the 12th and 13th centuries, when its ships controlled the western Mediterranean and was able to express Pisan Romanesque

Pisan Romanesque style is a variant of the Romanesque architectural style that developed in Pisa at the end of the 10th century and which influenced a wide geographical area at the time when the city was a powerful maritime republic (from the s ...

in the field of art, a mixture of Western, Eastern, Islamic and classical elements.

Pisa's rivalry with Genoa sharpened in the 13th century and led to the naval Battle of Meloria (1284), which marked the beginning of Pisan decline; Pisa ceded Corsica to Genoa in 1299, and in 1324, the Battle of Lucocisterna saw Sardinia ceded to Aragon

Aragon ( , ; Spanish and ; ) is an autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community in Spain, coextensive with the medieval Kingdom of Aragon. In northeastern Spain, the Aragonese autonomous community comprises three provinces of Spain, ...

. Unlike Genoa, Pisa needed to control a hinterland, which saw the rival cities of Lucca and Florence nearby: this subtracted forces from their navy and brought the republic to ruin.

In the fourteenth century, Pisa passed from a municipality to a lordship

A lordship is a territory held by a lord. It was a landed estate that served as the lowest administrative and judicial unit in rural areas. It originated as a unit under the feudal system during the Middle Ages. In a lordship, the functions of eco ...

, maintaining its independence and essentially the dominion of the Tuscan coast, and made peace with Genoa. However, in 1406, the city was besieged by the Milanese, Florentines, Genoese and French and annexed to the Republic of Florence. During Florence's crisis in the Italian Wars

The Italian Wars were a series of conflicts fought between 1494 and 1559, mostly in the Italian Peninsula, but later expanding into Flanders, the Rhineland and Mediterranean Sea. The primary belligerents were the House of Valois, Valois kings o ...

, Pisa revolted against Piero the Unfortunate and in 1494 reconstituted itself as an autonomous republic, restoring its own currency and magistracy. However, after 16 years of serious war, Florence managed to reconquer it definitively in 1509.

The ancient Porto Pisano, now filled in by the Arno floods, was located north of the current city of Livorno. The life of Fibonacci

Leonardo Bonacci ( – ), commonly known as Fibonacci, was an Italians, Italian mathematician from the Republic of Pisa, considered to be "the most talented Western mathematician of the Middle Ages".

The name he is commonly called, ''Fibonacci ...

, a mathematician from Pisa, well expresses the profitable relationship between commerce, navigation and culture typical of the maritime republics; he reworked and disseminated Arab scientific knowledge in Europe, including ten-digit numbering, and the use of zero.

Venice

Venice, founded by the Veneti fleeing the

Venice, founded by the Veneti fleeing the Huns

The Huns were a nomadic people who lived in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Eastern Europe between the 4th and 6th centuries AD. According to European tradition, they were first reported living east of the Volga River, in an area that was par ...

in the 5th century, began a gradual process of independence from the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived History of the Roman Empire, the events that caused the ...

starting with the Exarchate of Ravenna

The Exarchate of Ravenna (; ), also known as the Exarchate of Italy, was an administrative district of the Byzantine Empire comprising, between the 6th and 8th centuries, the territories under the jurisdiction of the exarch of Italy (''exarchus ...

's collapse in 751. Progress was made in 840 with the stipulation of the '' Pactum Lotharii'' between the doge Pietro Tradonico and the Germanic emperor Lothair I

Lothair I (9th. C. Frankish: ''Ludher'' and Medieval Latin: ''Lodharius''; Dutch and Medieval Latin: ''Lotharius''; German: ''Lothar''; French: ''Lothaire''; Italian: ''Lotario''; 795 – 29 September 855) was a 9th-century emperor of the ...

, without the Byzantine sovereign being called into question. Venice acquired power from the development of commercial relations with the Byzantine Empire, of which it was formally still part, to remain even later on as an ally in the fight against the Arabs and Normans. The definitive break with Constantinople came only with the war of 1122-1126, when the doge Domenico Michiel declared war on the Eastern Empire following his refusal to renew the commercial privileges already guaranteed to his Venetian vassal as a reward for the help offered in the war against the Normans in 1082. This war led to complete independence, in law and in fact, institutionalized in 1143 with the Commune of Venice.

Around the year 1000, Venice began its expansion in the Adriatic Sea

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkans, Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Se ...

, defeating the pirates who occupied the coasts of Istria

Istria ( ; Croatian language, Croatian and Slovene language, Slovene: ; Italian language, Italian and Venetian language, Venetian: ; ; Istro-Romanian language, Istro-Romanian: ; ; ) is the largest peninsula within the Adriatic Sea. Located at th ...

and Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; ; ) is a historical region located in modern-day Croatia and Montenegro, on the eastern shore of the Adriatic Sea. Through time it formed part of several historical states, most notably the Roman Empire, the Kingdom of Croatia (925 ...

and placing those regions and their principal townships under Venetian dominion.

Institutionally, Venice was governed by an oligarchy of the main merchant families, under the presidency of the doge and numerous articulated magistracies, including the Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

; notable was the Serrata del Maggior Consiglio (1297), with which those who did not belong to the most important merchant families were excluded from the government. In Venice, the ''Capitulare nauticum'', one of the first navigation codes, was written in 1256.

The Fourth Crusade

The Fourth Crusade (1202–1204) was a Latin Christian armed expedition called by Pope Innocent III. The stated intent of the expedition was to recapture the Muslim-controlled city of Jerusalem, by first defeating the powerful Egyptian Ayyubid S ...

(1202-1204) allowed Venice to conquer the most commercially important seaside resorts of the Byzantine Empire, including Corfu

Corfu ( , ) or Kerkyra (, ) is a Greece, Greek island in the Ionian Sea, of the Ionian Islands; including its Greek islands, small satellite islands, it forms the margin of Greece's northwestern frontier. The island is part of the Corfu (regio ...

(1207) and Crete