Maria Nikiforova on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Maria Hryhorivna Nikiforova (; 1885–1919) was a Ukrainian anarchist

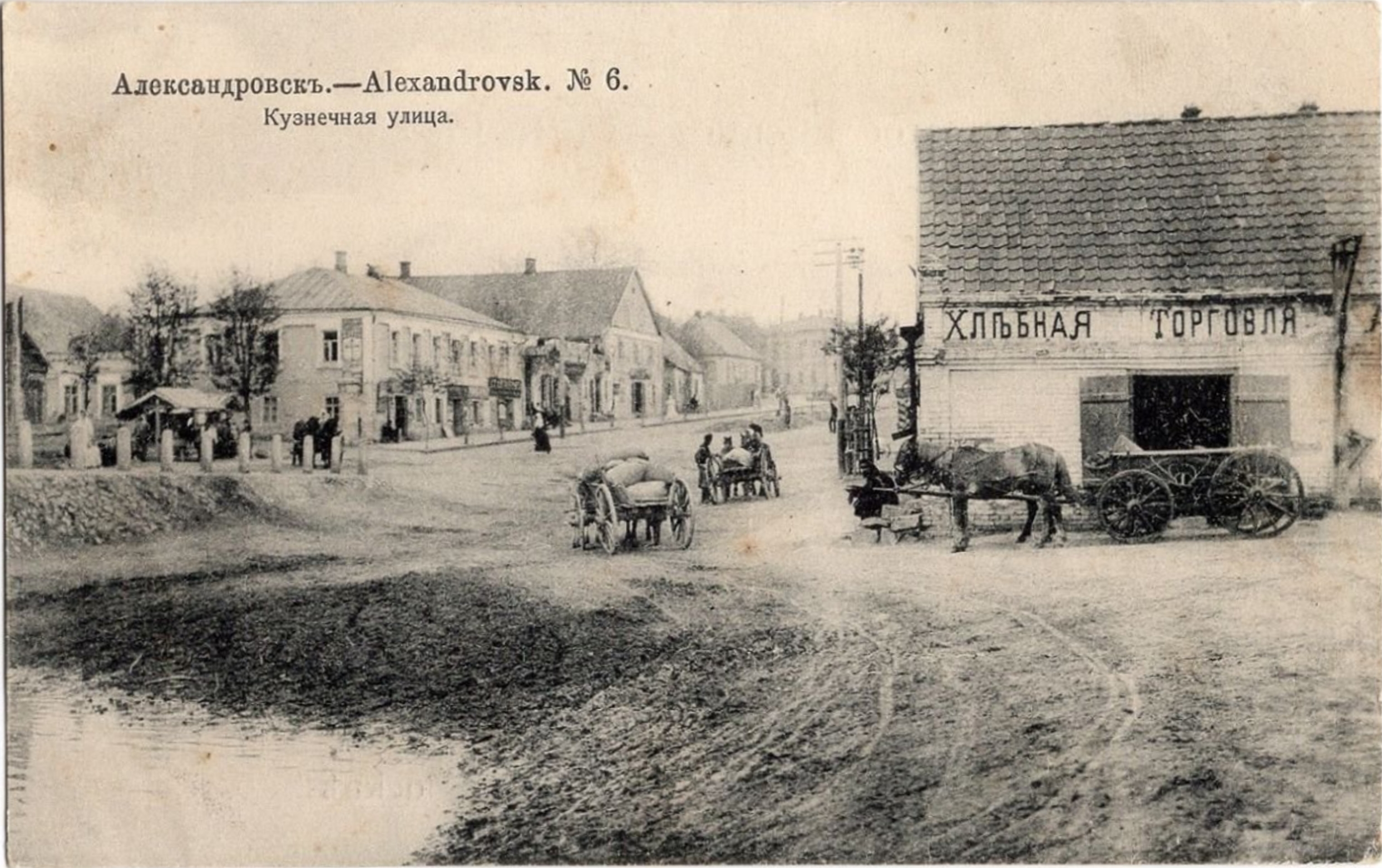

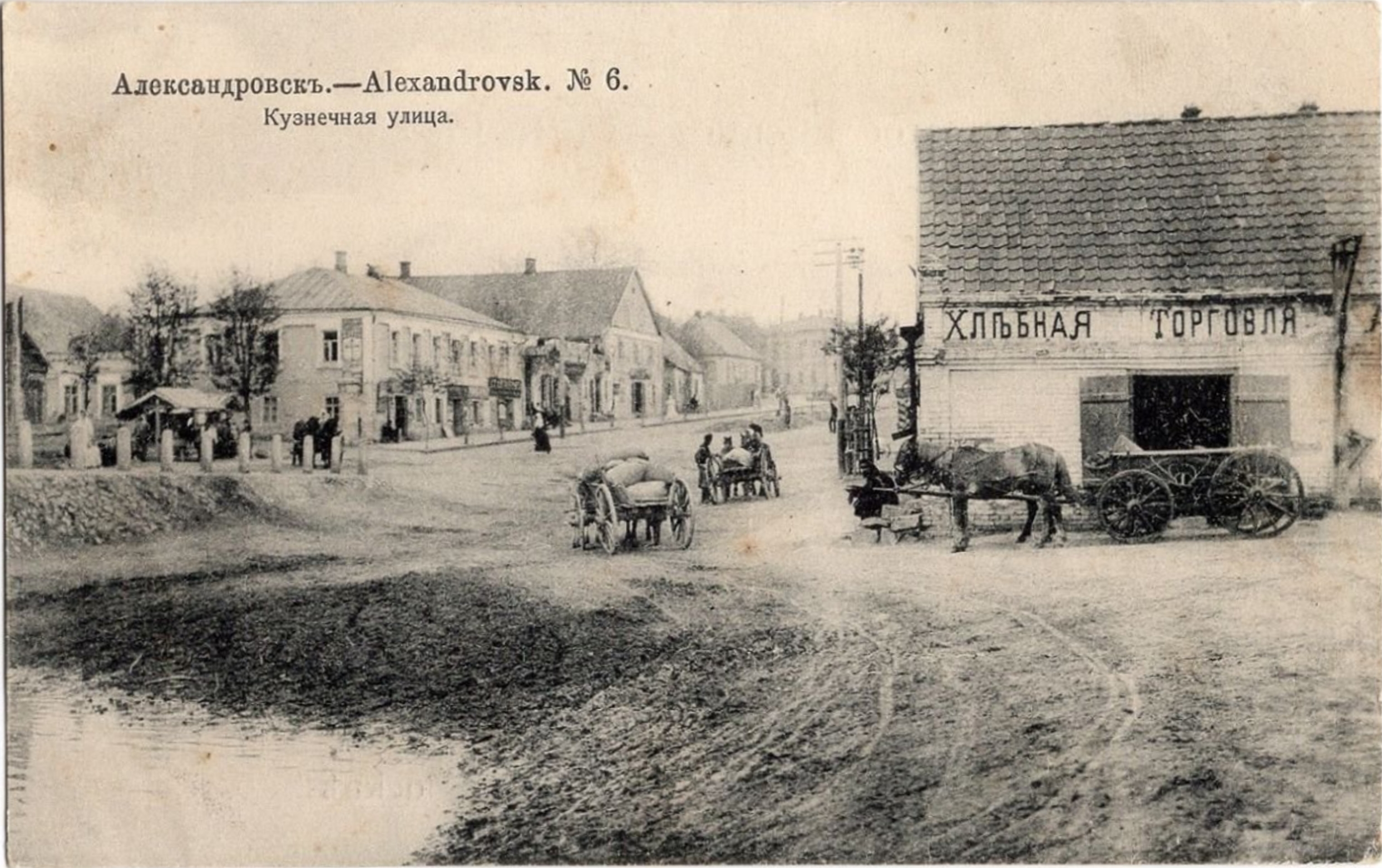

Born in Oleksandrivsk in 1885, Nikiforova's father had been an officer during the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878. She left home at the age of 16, having fallen in love with an "adventurer" who quickly abandoned her in the slums of Oleksandrivsk. To make ends meet, she became a

Born in Oleksandrivsk in 1885, Nikiforova's father had been an officer during the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878. She left home at the age of 16, having fallen in love with an "adventurer" who quickly abandoned her in the slums of Oleksandrivsk. To make ends meet, she became a  In the cafes of the French capital, Nikiforova met a number of exiled Russian artists and politicians, one of which was the Ukrainian Social-Democrat

In the cafes of the French capital, Nikiforova met a number of exiled Russian artists and politicians, one of which was the Ukrainian Social-Democrat

Nikiforova welcomed the outbreak of the

Nikiforova welcomed the outbreak of the

In a joint operation together with the Huliaipole anarchists, Nikiforova launched another raid against the garrison in Orikhiv, seizing a cache of arms and sending them on to Huliaipole, rather than handing them over to her nominal commander Semyon Bogdanov. As Nikiforova's Black Guards had helped to establish Soviet power in the eastern Ukrainian cities of Kharkiv, Katerynoslav and Oleksandrivsk, she enjoyed the unqualified support of the Ukrainian Soviet commander-in-chief,

In a joint operation together with the Huliaipole anarchists, Nikiforova launched another raid against the garrison in Orikhiv, seizing a cache of arms and sending them on to Huliaipole, rather than handing them over to her nominal commander Semyon Bogdanov. As Nikiforova's Black Guards had helped to establish Soviet power in the eastern Ukrainian cities of Kharkiv, Katerynoslav and Oleksandrivsk, she enjoyed the unqualified support of the Ukrainian Soviet commander-in-chief,

partisan

Partisan(s) or The Partisan(s) may refer to:

Military

* Partisan (military), paramilitary forces engaged behind the front line

** Francs-tireurs et partisans, communist-led French anti-fascist resistance against Nazi Germany during WWII

** Ital ...

leader who led the Black Guards during the Ukrainian War of Independence

The Ukrainian War of Independence, also referred to as the Ukrainian–Soviet War in Ukraine, lasted from March 1917 to November 1921 and was part of the wider Russian Civil War. It saw the establishment and development of an independent Ukr ...

, becoming widely renowned as an ataman

Ataman (variants: ''otaman'', ''wataman'', ''vataman''; ; ) was a title of Cossack and haidamak leaders of various kinds. In the Russian Empire, the term was the official title of the supreme military commanders of the Cossack armies. The Ukra ...

sha. A self-described terrorist from the age of 16, she was imprisoned for her activities in Russia before managing to escape to western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's extent varies depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the Western half of the ancient Mediterranean ...

. With the outbreak of World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, she took up the defencist line and joined the French Foreign Legion

The French Foreign Legion (, also known simply as , "the Legion") is a corps of the French Army created to allow List of militaries that recruit foreigners, foreign nationals into French service. The Legion was founded in 1831 and today consis ...

on the Macedonian front

The Macedonian front, also known as the Salonica front (after Thessaloniki), was a military theatre of World War I formed as a result of an attempt by the Allied Powers to aid Serbia, in the autumn of 1915, against the combined attack of Germa ...

before returning to Ukraine with the outbreak of the 1917 Revolution.

In her home city of Oleksandrivsk (today Zaporizhzhia

Zaporizhzhia, formerly known as Aleksandrovsk or Oleksandrivsk until 1921, is a city in southeast Ukraine, situated on the banks of the Dnieper, Dnieper River. It is the Capital city, administrative centre of Zaporizhzhia Oblast. Zaporizhzhia ...

), she established an anarchist combat detachment and subsequently attacked the forces of the Russian Provisional Government

The Russian Provisional Government was a provisional government of the Russian Empire and Russian Republic, announced two days before and established immediately after the abdication of Nicholas II on 2 March, O.S. New_Style.html" ;"title="5 ...

and the Ukrainian People's Republic

The Ukrainian People's Republic (UPR) was a short-lived state in Eastern Europe. Prior to its proclamation, the Central Council of Ukraine was elected in March 1917 Ukraine after the Russian Revolution, as a result of the February Revolution, ...

. After the October Revolution

The October Revolution, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (in Historiography in the Soviet Union, Soviet historiography), October coup, Bolshevik coup, or Bolshevik revolution, was the second of Russian Revolution, two r ...

escalated into a civil war

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

, she joined the side of the Ukrainian Soviet Republic, leading her ''druzhina

A druzhina is the Slavonic word for a retinue in service of a chieftain, also called a ''knyaz'' (prince).

Kievan Rus'

''Druzhina'' was flexible both as a term and as an institution. At its core, it referred to the prince's permanent perso ...

'' in capturing Taurida

The recorded history of the Crimean Peninsula, historically known as ''Tauris'', ''Taurica'' (), and the ''Tauric Chersonese'' (, "Tauric Peninsula"), begins around the 5th century BCE when several Greek colonies were established along its coast ...

and Yelysavethrad (today Kropyvnytskyi

Kropyvnytskyi (, ) is a city in central Ukraine, situated on the Inhul, Inhul River. It serves as the administrative center of Kirovohrad Oblast. Population:

Over its history, Kropyvnytskyi has changed its name several times. The settlement ...

) from the Ukrainian People's Army

The Ukrainian People's Army (), also known as the Ukrainian National Army (UNA) or by the derogatory term Petliurivtsi (, ), was the army of the Ukrainian People's Republic (1917–1921). They were often quickly reorganized units of the former I ...

.

When Ukraine was invaded by the Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,; ; , ; were one of the two main coalitions that fought in World War I (1914–1918). It consisted of the German Empire, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Bulga ...

, she was forced to flee to Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

, where she was prosecuted for insubordination by the nascent Bolshevik government. When she returned to Ukraine, she briefly participated in the civilian activities of the Makhnovshchina

The Makhnovshchina (, ) was a Political movement#Mass movements, mass movement to establish anarchist communism in southern Ukraine, southern and eastern Ukraine during the Ukrainian War of Independence of 1917–1921. Named after Nestor Makhno, ...

before returning to terrorism. She aimed to assassinate the leaders of the White movement

The White movement,. The old spelling was retained by the Whites to differentiate from the Reds. also known as the Whites, was one of the main factions of the Russian Civil War of 1917–1922. It was led mainly by the Right-wing politics, right- ...

(Anton Denikin

Anton Ivanovich Denikin (, ; – 7 August 1947) was a Russian military leader who served as the Supreme Ruler of Russia, acting supreme ruler of the Russian State and the commander-in-chief of the White movement–aligned armed forces of Sout ...

and Alexander Kolchak

Admiral Alexander Vasilyevich Kolchak (; – 7 February 1920) was a Russian navy officer and polar explorer who led the White movement in the Russian Civil War. As he assumed the title of Supreme Ruler of Russia in 1918, Kolchak headed a mili ...

) but was caught and executed.

Biography

Early life and exile

Born in Oleksandrivsk in 1885, Nikiforova's father had been an officer during the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878. She left home at the age of 16, having fallen in love with an "adventurer" who quickly abandoned her in the slums of Oleksandrivsk. To make ends meet, she became a

Born in Oleksandrivsk in 1885, Nikiforova's father had been an officer during the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878. She left home at the age of 16, having fallen in love with an "adventurer" who quickly abandoned her in the slums of Oleksandrivsk. To make ends meet, she became a wage labor

Wage labour (also wage labor in American English), usually referred to as paid work, paid employment, or paid labour, refers to the socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer in which the worker sells their labour power under ...

er, working first as babysitter

Babysitting is temporarily caring for a child. Babysitting can be a paid job for all ages; however, it is best known as a temporary activity for early teenagers who are not yet eligible for employment in the general economy. It provides auto ...

, then as a retail clerk

A retail clerk, also known as a sales clerk, shop clerk, retail associate, or (in the United Kingdom and Ireland) shop assistant, sales assistant or customer service assistant, is a service role in a retail business.

A retail clerk obtains or re ...

, and ultimately as a factory worker, washing bottles in a vodka distillery.

Shortly after starting work, she joined a local anarchist communist group, which had been established in the lead up to the 1905 Revolution

The Russian Revolution of 1905, also known as the First Russian Revolution, was a revolution in the Russian Empire which began on 22 January 1905 and led to the establishment of a constitutional monarchy under the Russian Constitution of 1906, t ...

. Following a period of political probation, Nikiforova became involved in the group's campaign of "motiveless terrorism", during which she staged a number of bombings and expropriation missions, including armed robberies. When Nikiforova was captured, she attempted to commit suicide by blowing herself up, but the bomb failed and she was imprisoned. In 1908, her trial for murder and armed robbery resulted in Nikiforova being sentenced to capital punishment

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty and formerly called judicial homicide, is the state-sanctioned killing of a person as punishment for actual or supposed misconduct. The sentence (law), sentence ordering that an offender b ...

, although this was later commuted to life imprisonment

Life imprisonment is any sentence (law), sentence of imprisonment under which the convicted individual is to remain incarcerated for the rest of their natural life (or until pardoned or commuted to a fixed term). Crimes that result in life impr ...

with hard labor, due to her young age. She served part of her sentence in solitary confinement

Solitary confinement (also shortened to solitary) is a form of imprisonment in which an incarcerated person lives in a single Prison cell, cell with little or no contact with other people. It is a punitive tool used within the prison system to ...

in St. Petersburg

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland on the Baltic Sea. The city had a population of 5,601, ...

's Petropavlovsk prison, before being exiled to Siberia

Siberia ( ; , ) is an extensive geographical region comprising all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has formed a part of the sovereign territory of Russia and its predecessor states ...

in 1910.

After staging a prison riot, she escaped via the Trans-Siberian Railway

The Trans-Siberian Railway, historically known as the Great Siberian Route and often shortened to Transsib, is a large railway system that connects European Russia to the Russian Far East. Spanning a length of over , it is the longest railway ...

to Vladivostok

Vladivostok ( ; , ) is the largest city and the administrative center of Primorsky Krai and the capital of the Far Eastern Federal District of Russia. It is located around the Zolotoy Rog, Golden Horn Bay on the Sea of Japan, covering an area o ...

and subsequently went on to Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

. A group of Chinese anarchists secured her passage to the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

, where she briefly stayed with other exiled Russian anarchists and published articles in their Russian language

Russian is an East Slavic languages, East Slavic language belonging to the Balto-Slavic languages, Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European languages, Indo-European language family. It is one of the four extant East Slavic languages, and is ...

newspapers. In 1912, she joined the anarchist movement in Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

and participated in a bank robbery in Barcelona

Barcelona ( ; ; ) is a city on the northeastern coast of Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second-most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within c ...

during which she was wounded and forced to clandestinely seek treatment in Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

. Herself an intersex

Intersex people are those born with any of several sex characteristics, including chromosome patterns, gonads, or genitals that, according to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, "do not fit typical binar ...

woman, Nikiforova also reportedly underwent a medical intervention while being treated.

In the cafes of the French capital, Nikiforova met a number of exiled Russian artists and politicians, one of which was the Ukrainian Social-Democrat

In the cafes of the French capital, Nikiforova met a number of exiled Russian artists and politicians, one of which was the Ukrainian Social-Democrat Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko

Vladimir Alexandrovich Antonov-Ovseenko (; ; 9 March 1883 – 10 February 1938), real surname Ovseenko, party aliases 'Bayonet' () and 'Nikita' (), literary pseudonym A. Galsky (), was a prominent Bolshevik leader, Soviet statesman, mili ...

, and even became an artist herself, specializing in painting and sculpting. During this time, she also entered into a marriage of convenience with a Polish anarchist named Witold Brozstek, retaining her last name. Towards the end of 1913, she attended an anarchist conference in London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

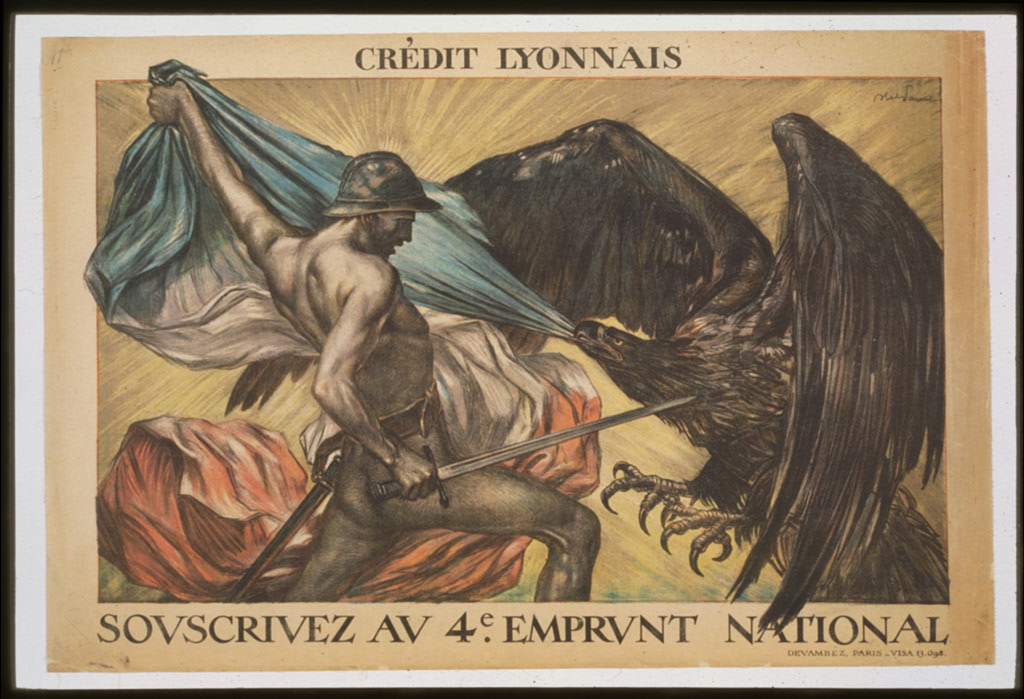

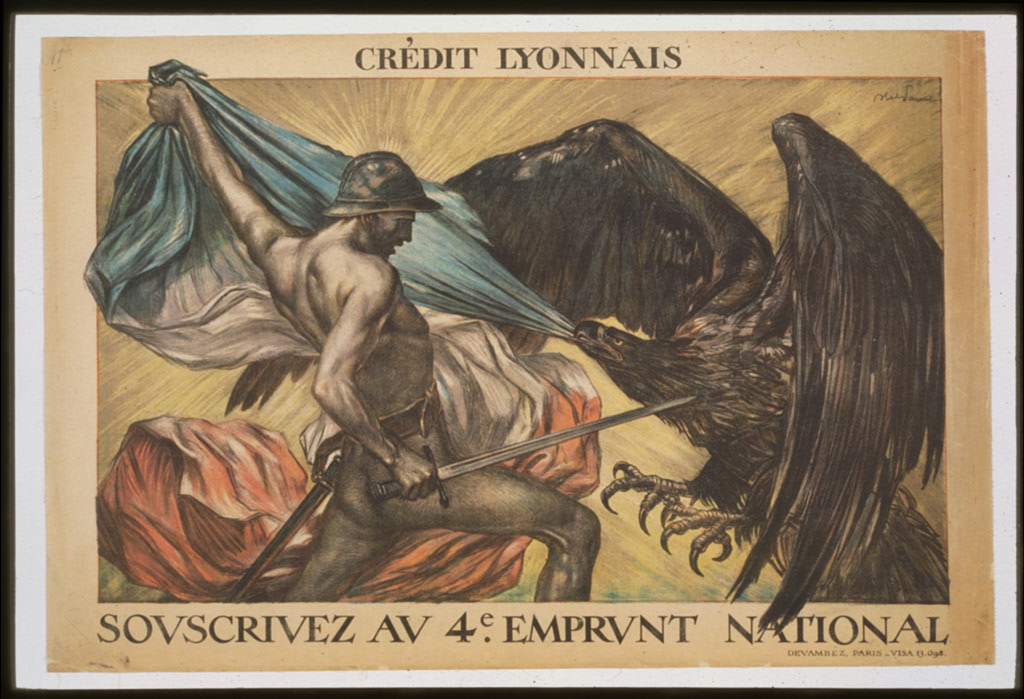

, signing her name as "Marusya", a Slavic diminutive form of "Maria". With the outbreak of World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, she sided with Peter Kropotkin

Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin (9 December 1842 – 8 February 1921) was a Russian anarchist and geographer known as a proponent of anarchist communism.

Born into an aristocratic land-owning family, Kropotkin attended the Page Corps and later s ...

's anti-German position, in favor of the Allied powers. She joined up with the French Foreign Legion

The French Foreign Legion (, also known simply as , "the Legion") is a corps of the French Army created to allow List of militaries that recruit foreigners, foreign nationals into French service. The Legion was founded in 1831 and today consis ...

and subsequently graduated as an officer from a military college. Nikiforova served on the Macedonian front

The Macedonian front, also known as the Salonica front (after Thessaloniki), was a military theatre of World War I formed as a result of an attempt by the Allied Powers to aid Serbia, in the autumn of 1915, against the combined attack of Germa ...

before the outbreak of the 1917 Revolution convinced her to quit the front and return home.

Return to Oleksandrivsk

When Nikiforova arrived inPetrograd

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland on the Baltic Sea. The city had a population of 5,601, ...

, she found the city in a situation of "dual power

Dual power, sometimes referred to as counterpower, refers to a strategy in which alternative institutions coexist with and seek to ultimately replace existing authority.

The term was first used by the communist Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin ...

", with both the Provisional Government

A provisional government, also called an interim government, an emergency government, a transitional government or provisional leadership, is a temporary government formed to manage a period of transition, often following state collapse, revoluti ...

and the local soviet vying for control while the anarchists mostly acted as shock troops

Shock troops, assault troops, or storm troops are special formations created to lead military attacks. They are often better trained and equipped than other military units and are expected to take heavier casualties even in successful operations. ...

of anti-government unrest. Nikiforova organized and spoke at pro-anarchist rallies in Kronstadt

Kronstadt (, ) is a Russian administrative divisions of Saint Petersburg, port city in Kronshtadtsky District of the federal cities of Russia, federal city of Saint Petersburg, located on Kotlin Island, west of Saint Petersburg, near the head ...

, where she convinced thousands of sailors to participate in an uprising against the Provisional Government. As the Bolsheviks withheld their support from the uprising, it was ultimately suppressed. Nikiforova narrowly escaped the subsequent government crackdown in Petrograd and fled back to her home city of Oleksandrivsk, finally arriving in July 1917 after eight years in exile. Shortly after arrival, together with the city's 300-strong Anarchist Federation and supported by local factory workers, Nikiforova carried out the expropriation of the local distillery, donating part of the seized money to the local soviet

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

. She soon established a 60-strong anarchist combat detachment and started accumulating armaments

A weapon, arm, or armament is any implement or device that is used to deter, threaten, inflict physical damage, harm, or kill. Weapons are used to increase the efficacy and efficiency of activities such as hunting, crime (e.g., murder), law ...

procured from attacks on police stations and warehouses, with which she hunted down and executed many of the city's army officers and landlords.

On 29 August 1917, she met with the peasant leader Nestor Makhno

Nestor Ivanovych Makhno (, ; 7 November 1888 – 25 July 1934), also known as Bat'ko Makhno ( , ), was a Ukrainians, Ukrainian anarchist revolutionary and the commander of the Revolutionary Insurgent Army of Ukraine during the Ukrainian War o ...

in the anarchist-controlled town of Huliaipole

Huliaipole ( ; ) is a small city in Polohy Raion, Zaporizhzhia Oblast, Ukraine. It is known as the birthplace of Ukrainian anarchist revolutionary Nestor Makhno. In January 2022, it had an estimated population of

Huliaipole was attacked by ...

, where she gave a speech advocating for an insurrection

Rebellion is an uprising that resists and is organized against one's government. A rebel is a person who engages in a rebellion. A rebel group is a consciously coordinated group that seeks to gain political control over an entire state or a ...

against the rule of the newly established Central Council of Ukraine

The Central Rada of Ukraine, also called the Central Council (), was the All-Ukrainian council that united deputies of soldiers, workers, and peasants deputies as well as few members of political, public, cultural and professional organizations o ...

, warning of a potential counter-revolution. Partway through Nikiforova's speech, the anarchists received news from Petrograd of an attempted coup by Lavr Kornilov and resolved to form a Committee for the Defence of the Revolution (CDR). When the CDR began making plans to seize weapons from the local bourgeoisie

The bourgeoisie ( , ) are a class of business owners, merchants and wealthy people, in general, which emerged in the Late Middle Ages, originally as a "middle class" between the peasantry and aristocracy. They are traditionally contrasted wi ...

, Nikiforova countered with a plan of her own: to raid the nearby garrison at Orikhiv. By 10 September, she had pulled together 200 fighters, armed only with only a few dozen weapons, and set out for Orikhiv by train. Upon arrival, the anarchist detachment surrounded and captured the Russian Army

The Russian Ground Forces (), also known as the Russian Army in English, are the Army, land forces of the Russian Armed Forces.

The primary responsibilities of the Russian Ground Forces are the protection of the state borders, combat on land, ...

regiments. Nikiforova ordered the execution of all officers and disarmed the rank-and-file soldiers before letting them return to their homes. She delivered the captured weapons back to the CDR in Huliaipole, then returned to Oleksandrivsk herself. In recognition of Nikiforova's help, Makhno named one of his commando

A commando is a combatant, or operative of an elite light infantry or special operations force, specially trained for carrying out raids and operating in small teams behind enemy lines.

Originally, "a commando" was a type of combat unit, as oppo ...

brigade

A brigade is a major tactical military unit, military formation that typically comprises three to six battalions plus supporting elements. It is roughly equivalent to an enlarged or reinforced regiment. Two or more brigades may constitute ...

s "Marusya" after her.

Huliaipole subsequently began to receive threats from the local organ of the Provisional Government in Oleksandrivsk, which was disturbed by the rising anarchist influence in the region. Makhno responded by traveling to the city with Nikiforova as a guide and speaking directly to the local workers' organizations. After Makhno left the city, the authorities swiftly arrested and imprisoned Nikiforova. News of her arrest quickly spread; a delegation of workers demanded her release the next day. After being rebuffed by the Provisional Government, the workers forcibly brought the leader of the soviet to the prison and secured her release, following which Nikiforova gave a speech to the crowd, calling for anarchy

Anarchy is a form of society without rulers. As a type of stateless society, it is commonly contrasted with states, which are centralized polities that claim a monopoly on violence over a permanent territory. Beyond a lack of government, it can ...

. Anarchists from Huliaipole, who had been dispatched to attack Oleksandrivsk and force Nikiforova's release, celebrated upon hearing that their work had already been carried out.

During the subsequent election to the Oleksandrivsk soviet, the composition of the new body was distinctly more left-wing

Left-wing politics describes the range of Ideology#Political ideologies, political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy either as a whole or of certain social ...

and included a number of anarchist delegates.

Battle for Oleksandrivsk

October Revolution

The October Revolution, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (in Historiography in the Soviet Union, Soviet historiography), October coup, Bolshevik coup, or Bolshevik revolution, was the second of Russian Revolution, two r ...

as another step towards the "withering away of the state

The withering away of the state is a Marxist concept coined by Friedrich Engels referring to the expectation that, with the realization of socialism, the state will eventually become obsolete and cease to exist as society will be able to gover ...

". She set about establishing armed detachments known as the " Black Guards" in Oleksandrivsk, preparing an organized anarchist response for a conflict that was rapidly escalating into civil war

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

. In November 1917, the Oleksandrivsk Soviet voted 147 to 95 in favor of joining the Ukrainian People's Republic

The Ukrainian People's Republic (UPR) was a short-lived state in Eastern Europe. Prior to its proclamation, the Central Council of Ukraine was elected in March 1917 Ukraine after the Russian Revolution, as a result of the February Revolution, ...

and refused to recognize the authority of the newly proclaimed Russian Soviet Republic

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (Russian SFSR or RSFSR), previously known as the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic and the Russian Soviet Republic, and unofficially as Soviet Russia,Declaration of Rights of the labo ...

. Nikiforova responded by allying with the local revolutionary socialists, securing a clandestine shipment of weaponry and the support of the local detachment of the Black Sea Fleet

The Black Sea Fleet () is the Naval fleet, fleet of the Russian Navy in the Black Sea, the Sea of Azov and the Mediterranean Sea. The Black Sea Fleet, along with other Russian ground and air forces on the Crimea, Crimean Peninsula, are subordin ...

. On 12 December, they launched their uprising

Rebellion is an uprising that resists and is organized against one's government. A rebel is a person who engages in a rebellion. A rebel group is a consciously coordinated group that seeks to gain political control over an entire state or a ...

, managing to overthrow the Soviet and reconstitute it with delegates from the Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

, Left SRs and anarchists

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that seeks to abolish all institutions that perpetuate authority, coercion, or hierarchy, primarily targeting the state and capitalism. Anarchism advocates for the replacement of the state w ...

.

On 25 December, Nikiforova and her detachment went to Kharkiv

Kharkiv, also known as Kharkov, is the second-largest List of cities in Ukraine, city in Ukraine.

, where they collaborated in the establishment of the Ukrainian People's Republic of Soviets

The Ukrainian People's Republic of Soviets (; ) was a short-lived (1917–1918) Soviet republic of the Russian SFSR that was created by the declaration of the Kharkiv All-Ukrainian Congress of Soviets "About the self-determination of Ukraine" ...

while also expropriating goods from the local shops and redistributing them to the population. A few days later, she led Black Guards into battle against the haydamaks at Katerynoslav, capturing the city for the Soviets and personally disarming 48 soldiers. Civil war became an inevitability following the dissolution of the Russian Constituent Assembly

The All Russian Constituent Assembly () was a constituent assembly convened in Russia after the February Revolution of 1917. It met for 13 hours, from 4 p.m. to 5 a.m., , whereupon it was dissolved by the Bolshevik-led All-Russian Central Ex ...

by the All-Russian Central Executive Committee

The All-Russian Central Executive Committee () was (June – November 1917) a permanent body formed by the First All-Russian Congress of Soviets of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies (held from June 16 to July 7, 1917 in Petrograd), then became the ...

, as the Bolsheviks began to look towards the anarchists around Nikiforova as a necessary base of support in Ukraine. While she had been away, her home city of Oleksandrivsk had fallen again under the control of the Central Council of Ukraine

The Central Rada of Ukraine, also called the Central Council (), was the All-Ukrainian council that united deputies of soldiers, workers, and peasants deputies as well as few members of political, public, cultural and professional organizations o ...

after three days of fighting, forcing the local anarchist detachments to withdraw. On 2 January 1918, the city was again recaptured after the arrival of Red Guards

The Red Guards () were a mass, student-led, paramilitary social movement mobilized by Chairman Mao Zedong in 1966 until their abolition in 1968, during the first phase of the Cultural Revolution, which he had instituted.Teiwes

According to a ...

from Russia and Black Guards from Huliaipole, forcing the haydamaks in turn to retreat to right-bank Ukraine

The Right-bank Ukraine is a historical and territorial name for a part of modern Ukraine on the right (west) bank of the Dnieper River, corresponding to the modern-day oblasts of Vinnytsia, Zhytomyr, Kirovohrad, as well as the western parts o ...

. Two days later, a revolutionary committee (Revkom) was constituted as the center of soviet power in Oleksandrivsk. Nikiforova was elected as its deputy leader

A deputy leader (in Scottish English, sometimes depute leader) in the Westminster system is the second-in-command of a political party, behind the party leader. Deputy leaders often become Deputy prime minister when their parties are elected to go ...

.

As the haymadaks fled, cossacks

The Cossacks are a predominantly East Slavic languages, East Slavic Eastern Christian people originating in the Pontic–Caspian steppe of eastern Ukraine and southern Russia. Cossacks played an important role in defending the southern borde ...

were already beginning to return from the external front in order to join up with Alexey Kaledin's Army

An army, ground force or land force is an armed force that fights primarily on land. In the broadest sense, it is the land-based military branch, service branch or armed service of a nation or country. It may also include aviation assets by ...

, and Oleksandrivsk was in the path towards their home regions of the Don and Kuban

Kuban ( Russian and Ukrainian: Кубань; ) is a historical and geographical region in the North Caucasus region of southern Russia surrounding the Kuban River, on the Black Sea between the Don Steppe, the Volga Delta and separated fr ...

. With the Black Guards scrambling to rally their defenses, a failed assault by the first wave of Cossacks ended in their disarmament by the Revkom. While the disarmament took place, the city politicians' speeches, attempting to rally the Cossacks to the cause of socialism

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

, were largely ignored and even mocked. When Nikiforova spoke, calling on the "butchers of the Russian workers" to renounce the old ways of Tsarism, many of the Cossacks began to display humility; some openly wept and others maintained contact with the local anarchists. When the Cossacks departed, Makhno and Nikiforova returned to their duties in the Revkom. After a dispute between the two regarding the sentencing of the prosecutor that had overseen Makhno's own imprisonment, Makhno decided to renounce his position and return to Huliaipole, leaving Nikiforova in place as the sole commander of Oleksandrivsk's Black Guards.

The Free Combat Druzhina

In a joint operation together with the Huliaipole anarchists, Nikiforova launched another raid against the garrison in Orikhiv, seizing a cache of arms and sending them on to Huliaipole, rather than handing them over to her nominal commander Semyon Bogdanov. As Nikiforova's Black Guards had helped to establish Soviet power in the eastern Ukrainian cities of Kharkiv, Katerynoslav and Oleksandrivsk, she enjoyed the unqualified support of the Ukrainian Soviet commander-in-chief,

In a joint operation together with the Huliaipole anarchists, Nikiforova launched another raid against the garrison in Orikhiv, seizing a cache of arms and sending them on to Huliaipole, rather than handing them over to her nominal commander Semyon Bogdanov. As Nikiforova's Black Guards had helped to establish Soviet power in the eastern Ukrainian cities of Kharkiv, Katerynoslav and Oleksandrivsk, she enjoyed the unqualified support of the Ukrainian Soviet commander-in-chief, Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko

Vladimir Alexandrovich Antonov-Ovseenko (; ; 9 March 1883 – 10 February 1938), real surname Ovseenko, party aliases 'Bayonet' () and 'Nikita' (), literary pseudonym A. Galsky (), was a prominent Bolshevik leader, Soviet statesman, mili ...

, who gave her funds to upgrade her detachment, which became known as the .

Reinforced by extra troops, the Druzhina was supplied with artillery cannons, armored cars, tachankas, warhorses and even an armored train

An armoured train (Commonwealth English) or armored train (American English) is a railway train protected with vehicle armour, heavy metal plating and which often includes railway wagons armed with artillery, machine guns, and autocannons. So ...

, which they decorated with a number of anarchist flags, leaving them better-equipped than even the units of the Red Guards. The militants of the Druzhina also largely rejected uniform

A uniform is a variety of costume worn by members of an organization while usually participating in that organization's activity. Modern uniforms are most often worn by armed forces and paramilitary organizations such as police, emergency serv ...

, in favor of their own individual senses of fashion

Fashion is a term used interchangeably to describe the creation of clothing, footwear, Fashion accessory, accessories, cosmetics, and jewellery of different cultural aesthetics and their mix and match into Clothing, outfits that depict distinct ...

. While the core of the group was personally loyal to Nikiforova, including a number of experienced veterans of the Black Sea Fleet, the larger section around them participated in the unit on a more ephemeral basis.

Travelling in echelon formation

An echelon formation () is a (usually military) formation in which its units are arranged diagonally. Each unit is stationed behind and to the right (a "right echelon"), or behind and to the left ("left echelon"), of the unit ahead. The name of ...

s, which the Left SR politician Isaac Steinberg compared to the mythical Flying Dutchman

The ''Flying Dutchman'' () is a legendary ghost ship, allegedly never able to make port, but doomed to sail the sea forever. The myths and ghost stories are likely to have originated from the 17th-century Golden Age of the Dutch East India C ...

, the Druzhina advanced against the forces of the White movement

The White movement,. The old spelling was retained by the Whites to differentiate from the Reds. also known as the Whites, was one of the main factions of the Russian Civil War of 1917–1922. It was led mainly by the Right-wing politics, right- ...

and the Ukrainian nationalists. The Druzhina pushed as far as Crimea, where they captured Yalta

Yalta (: ) is a resort town, resort city on the south coast of the Crimean Peninsula surrounded by the Black Sea. It serves as the administrative center of Yalta Municipality, one of the regions within Crimea. Yalta, along with the rest of Crime ...

, sacked Livadia Palace and liberated anarchist political prisoners in Sevastopol

Sevastopol ( ), sometimes written Sebastopol, is the largest city in Crimea and a major port on the Black Sea. Due to its strategic location and the navigability of the city's harbours, Sevastopol has been an important port and naval base th ...

. Having participated in the establishment of the Taurida Soviet Socialist Republic, Nikiforova was elected to head the Peasant Soviet in Feodosia

Feodosia (, ''Feodosiia, Teodosiia''; , ''Feodosiya''), also called in English Theodosia (from ), is a city on the Crimean coast of the Black Sea. Feodosia serves as the administrative center of Feodosia Municipality, one of the regions into ...

and used her new position to establish more detachments of the Black Guards.

Battle for Yelysavethrad

The Druzhina then moved on to the central Ukrainian city of Yelysavethrad, bloodlessly capturing the city from the Ukrainian nationalists and establishing a revolutionary committee to oversee its transition to Soviet power. While occupying the city, she assassinated a Russian officer, expropriated local stores and redistributed basic necessities to the population, and established abarter

In trade, barter (derived from ''bareter'') is a system of exchange (economics), exchange in which participants in a financial transaction, transaction directly exchange good (economics), goods or service (economics), services for other goods ...

economy for non-essential goods, all in open defiance the Bolshevik-controlled Revkom. Nikiforova accused the Revkom of being too tolerant towards the bourgeoisie and having constituted a new ruling class

In sociology, the ruling class of a society is the social class who set and decide the political and economic agenda of society.

In Marxist philosophy, the ruling class are the class who own the means of production in a given society and apply ...

, even threatening to disperse the organ and shoot its chairman, due to her opposition to all forms of government. The Revkom responded by ordering her to leave the city, which she did a few days later, after looting the city's military college of all their weapons, leaving behind a newly established local detachment of Black Guards.

The Central Council of Ukraine responded to the rapid Soviet advance by signing a Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (Ukraine–Central Powers), treaty with the Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,; ; , ; were one of the two main coalitions that fought in World War I (1914–1918). It consisted of the German Empire, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Bulga ...

. With the support of the Ukrainian haydamaks, the Austro-Hungarian Army and Imperial German Army launched an Operation Faustschlag, invasion of Ukraine, pushing the Soviet lines back again. When the German forces arrived at Yelysavethrad, the Revkom immediately evacuated, leaving a power vacuum in the city. While the occupying powers attempted to recruit men to its side, even conscripting the local peasantry into service, the Druzhina returned to occupy Yelysavethrad, taking over the local railway station and regularly touring the city to expropriate money from the bourgeoisie. After days of tense peace between the city's official government and the anarchists, a conflict broke out between the anarchists and local factory workers, giving the government forces an opportunity to move against the Druzhina. The anarchists managed to defend themselves against the assault, but they were far outnumbered, forcing them to withdraw to Kanatovo (air base), Kanatovo, where they discovered that a number of their soldiers had been taken prisoner.

Red Guards led by attempted to retake the city, but they were surrounded and wiped out within hours of arrival, prompting the city authorities to beginning executing their prisoner of war, prisoners of war. Nikiforova subsequently led the Druzhina in an assault by rail, digging in at the suburbs, where they were met by thousands of well-armed troops, who began spreading rumours to the local population that depicted Nikiforova as a sacrilegious bandit leader. The battle descended into a war of attrition, with constant artillery and machine gun fire exchanged between the trenches over the course of two days. On 26 February, the Druzhina was reinforced by a detachment of Red Guards from , but these troops were largely ineffective against the city's defenses. Under heavy bombardment, the Druzhina fell back to Znamianka, Kirovohrad Oblast, Znamianka, where they were reinforced by more Red Guards under the command of Mikhail Artemyevich Muravyov, Mikhail Muravyov, fresh from their victory in the Battle of Kiev (1918), Battle of Kyiv. The city's authorities had requested reinforcements from the Central Powers, but none arrived, leaving the city vulnerable to a Soviet assault. While the Ukrainian nationalists held off Nikiforova's advance from the north, led an assault against the largely undefended south, forcing the city to capitulate. The city's authorities complied with the Soviet demands and released Nikiforova's imprisoned soldiers, with the city ultimately remaining in Soviet hands until 19 March, when an Imperial German assault forced the Soviet forces to evacuate.

Retreat

The forces of the Ukrainian Soviet Republic were ultimately unable to withstand the combined assault of the Central Powers, with only sporadic resistance delaying the offensive. After leaving Yelysavethrad, the Druzhina stooped in Berezivka, where they came into conflict with another anarchist detachment led by Grigory Kotovsky, after Nikiforova had attempted to extort money from the town's inhabitants. The Druzhina subsequently abandoned their train and reformed as a cavalry detachment, arranging their horses by fur color, with Nikiforova herself riding at the head on a white horse. The Druzhina rendezvoused with other Soviet forces at , finding the local estate in the hands of the Bolshevik commander . Nikiforova immediately set about seizing the estate's goods and redistributing them to the local population, to the annoyance of Matveyev, who she was still formally subordinated to. Matveyev resolved to disarm the Druzhina before any more anarchists arrived at the rendezvous. He called a general meeting in which the principles of unity and discipline were to be discussed, but when Bolsheviks started making complaints about the anarchists, Nikiforova immediately understood the true purpose of the meeting and signalled her partisans to leave, escaping the village on horseback before they could be disarmed. When Antonov-Ovseenko learned of the planned disarmament of Nikiforova's forces, he rebuked the local Bolsheviks, telling them: "Instead of disarming such revolutionary fighting units, I would advise you to create them." The Druzhina subsequently moved towards Oleksandrivsk, hoping to defend it from the Central Powers. Upon arrival, they found the city's Red Guards were already organizing their retreat. On 13 April, the Ukrainian Sich Riflemen were able to capture the city, finding the dead body of a woman that they mistakenly believed to be Nikiforova. On 18 April, they were followed by the Imperial German Army, which forced out the remaining Soviet forces, with the Druzhina being one of the last Soviet detachments to leave. They subsequently linked up with Nestor Makhno's forces in Bilmak, Tsarekostyantynivka, where they found out that Huliaipole had also fallen to the Ukrainian nationalists. Nikiforova proposed a mission to rescue captured members of the town's revolutionary committee, but after a number of Red commanders refused to join and news came in of the continued German advance, she abandoned the plan and continued to retreat east.Trials

Following the Soviet defeat in Ukraine, the Bolsheviks no longer saw the use in their anarchist allies and Red Terror, repressions against the Anarchism in Russia, Russian anarchist movement began to be carried out by the Cheka. Upon Nikiforova's arrival in Taganrog, she was immediately arrested on charges of looting and desertion, while the Druzhina was finally disarmed, in an operation overseen by the Ukrainian Bolshevik leader Volodymyr Zatonsky. The local anarchists and Left SRs demanded an explanation for Nikiforova's arrest, with Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko himself sending a telegram in support of the anarchists, while further arrivals of Ukrainian anarchists to the city began to make the situation untenable. In April 1918, a Revolutionary tribunal (Russia), revolutionary tribunal was held by the Ukrainian Bolsheviks. With witnesses both for the prosecution and the defense in attendance, Nikiforova was confident that revolutionary justice would be upheld and she was ultimately acquitted on all charges. The anarchists in Taganrog subsequently held a conference about the situation in Ukraine, during which Makhno and the Huliaipole anarchists decided they would return to southern Ukraine and carry out a campaign of guerrilla warfare against the Central Powers. Other anarchists joined Nikiforova's Druzhina, but the continued German offensive forced them to retreat to Rostov-on-Don, where they looted the local banks and burned all the Bond (finance), bonds, deeds and loan agreements they found in a public bonfire. Here too, Nikiforova noticed that the Bolsheviks were closing in on them and decided to take the Druzhina north towards Voronezh, and over the following months they moved between a number of towns along the Ukrainian border. After the Armistice of 11 November 1918, defeat of the Central Powers forced them to withdraw from Ukraine, the Ukrainian State was overthrown by the Directorate of Ukraine under Symon Petliura, making room for the Druzhina to finally return to the country in late 1918. In the subsequent power struggle, the Druzhina managed to seize Odessa, Odesa from the White movement, demolishing the prison before an Southern Russia intervention, armed intervention by the Allies of World War I, Allied Powers forced them to quit the city. The Druzhina then moved on to Saratov, where it was again disarmed and Nikiforova herself was again arrested. The Cheka were reluctant to execute her without trial and had her transferred to Moscow, where she was briefly held in Butyrka prison. She was released on bail, posted by Apollon Karelin and Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko, and she was reunited with her husband, who had taken a job in the new Soviet government. After a spell of working for the artistic institution Proletkult, Nikiforova's trial by revolutionary tribunal began on 21 January 1919. She was presented with the same charges that the Taganrog tribunal had already acquitted her of, with Georgy Pyatakov accusing her again of looting and desertion. On 25 January, ''Pravda'' announced that she had been found guilty of insubordination, although she had again been acquitted on the charges of looting, and that her punishment was a ban on holding any public office for six months.Activities in Huliaipole

Almost immediately following the trial, Nikiforova set out for Huliaipole, now the center of an autonomous anarchist republic known as theMakhnovshchina

The Makhnovshchina (, ) was a Political movement#Mass movements, mass movement to establish anarchist communism in southern Ukraine, southern and eastern Ukraine during the Ukrainian War of Independence of 1917–1921. Named after Nestor Makhno, ...

, as part of an agreement between Nestor Makhno's Revolutionary Insurgent Army of Ukraine, Revolutionary Insurgent Army and the Ukrainian Bolsheviks. Upon her arrival, Makhno had Nikiforova put in charge of the anarchists' hospitals, nurseries and schools, forbidding her from participating in military activities due to the terms of her sentence. Nikiforova's anti-Bolshevik attitude became an immediate problem for the Makhnovists, who were more focused on fighting the White movement, with Makhno himself physically removing her from a stage after she publicly denounced the Bolsheviks during a Regional Congress of Peasants, Workers and Insurgents#Second Congress (February 1919), Regional Congress. When she briefly returned to Oleksandrivsk, any anarchists she met or stayed with were promptly arrested by the Cheka.

During the spring of 1919, Huliaipole was visited several times by a series of high-ranking Bolsheviks, during which Nikiforova acted as a hostess. Antonov-Ovseenko recalled meeting his "old acquaintance" on 28 April, while reviewing Makhno's troops and the city of Huliaipole. Seeking to clarify rumors of corruption and counter-revolutionary activity among Makhno's ranks and the soviet of the city, Antonov-Ovseenko wrote glowingly of his impression of Huliaipole. Ultimately, Antonov-Ovseenko's attempts to lobby for military support for the anarchists were unsuccessful and his political power declined. Within weeks of his visit, he was replaced as commander-in-chief by Jukums Vācietis.

Nevertheless, Antonov-Ovseenko's reports quickly attracted Lev Kamenev to himself visit Huliaipole the very next week. Nikiforova met Kamenev and his entourage at the train station, and offered to escort them into the city. After meeting Makhno and touring the city, Kamenev was impressed with Nikiforova, and upon returning to Dnipro, Katerynoslav, he telegraphed Moscow officials with an order that her sentence be reduced to half of its original term.

Capture and death

Following news of the reduction of her sentence, Nikiforova moved to Berdiansk and began work on establishing a new detachment of Black Guards, bringing together a number of former Makhnovists and anarchist refugees, including her husband Witold Brzostek. By June 1919, theMakhnovshchina

The Makhnovshchina (, ) was a Political movement#Mass movements, mass movement to establish anarchist communism in southern Ukraine, southern and eastern Ukraine during the Ukrainian War of Independence of 1917–1921. Named after Nestor Makhno, ...

had been outlawed by the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, Ukrainian Socialist Soviet Republic and the Red Army had launched an offensive against the Makhnovist rear, forcing the Ukrainian anarchists to regroup. While Makhno moved towards consolidating his military force, Nikiforova returned to her old ways, deciding to carry out a campaign of terrorism against all enemies of the Ukrainian anarchists. When the pair reunited at Tokmak, Ukraine, Tokmak, Nikiforova asked Makhno for money to fund her terrorist campaign. The meeting quickly devolved into a Mexican standoff as the two drew guns on each other, but Makhno ultimately decided to give her some of the insurgent army's funds.

Nikiforova subsequently split up her detachment into three and dispatched them to different fronts. She sent one group to Siberia

Siberia ( ; , ) is an extensive geographical region comprising all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has formed a part of the sovereign territory of Russia and its predecessor states ...

, where they were ordered to assassinate Alexander Kolchak

Admiral Alexander Vasilyevich Kolchak (; – 7 February 1920) was a Russian navy officer and polar explorer who led the White movement in the Russian Civil War. As he assumed the title of Supreme Ruler of Russia in 1918, Kolchak headed a mili ...

, the Supreme Ruler of Russia, Supreme Ruler of the Russian State (1918–1920), Russian State, but they were ultimately unable to locate him and instead decided to join the Great Siberian Ice March, anti-White partisans. The other group went to Kharkiv

Kharkiv, also known as Kharkov, is the second-largest List of cities in Ukraine, city in Ukraine.

, where they were ordered to free anarchist political prisoners and blow up the headquarters of the Cheka, but by the time they arrived the city had been evacuated and the prisoners had been shot. They decided to move on to Moscow, where they carried out a series of armed robberies to fund their planned operation to assassinate the Bolshevik Party leadership. On 25 September 1919, they managed to kill 12 and wound 55 other leading Bolsheviks in a bomb attack on a party meeting. The group was eventually wiped out during shoot outs with the Cheka, with the last remaining members blowing themselves up after being surrounded in a dacha.

Nikiforova and Brzostek themselves led the third group to Crimea, the headquarters of South Russia (1919–1920), South Russia, where they planned to assassinate the White commander-in-chief Anton Denikin

Anton Ivanovich Denikin (, ; – 7 August 1947) was a Russian military leader who served as the Supreme Ruler of Russia, acting supreme ruler of the Russian State and the commander-in-chief of the White movement–aligned armed forces of Sout ...

. On 11 August, the couple were recognized by a White officer in Sevastopol

Sevastopol ( ), sometimes written Sebastopol, is the largest city in Crimea and a major port on the Black Sea. Due to its strategic location and the navigability of the city's harbours, Sevastopol has been an important port and naval base th ...

and arrested, forcing the rest of the group to quit Crimea and flee to the Kuban People's Republic, where they joined the region's anti-White partisans. After spending a month gathering evidence, on 16 September, Nikiforova and Brzostek were court-martialed by , the Governor of Sevastopol (Russia), Governor of Sevastopol. Nikiforova was charged with having executed counter-revolutionaries, including White officers and the bourgeoisie, while Brzostek was charged simply with having been her husband during these events. Throughout the trial, Nikiforova displayed persistent contempt of court, swearing at the tribunal as her sentence was read. The couple were both found guilty and sentenced to execution by firing squad, with Nikiforova finally breaking down into tears as she said goodbye to her husband, before they were both shot.

On 20 September, the ''Oleksandrivsk Telegraph'' reported on Nikiforova's death, celebrating it as a victory for the White movement. Only two weeks later, the city was recaptured by the Makhnovshchina, definitively ending the White movement's control over southern Ukraine.

Political positions

Anarchism and revolution

In her youth, Nikiforova entered Anarchist communism, anarcho-communist politics and adopted militant tactics to pursue them. Widely known as an anarchist, she was said to constantly wear entirely black clothing as a symbol of her libertarian philosophy. Throughout her years of activism, Nikiforova gave numerous speeches espousing her anarchist political opinions. She favored immediate and complete Redistribution of wealth, redistribution of property owned by wealthy land owners, declaring, "The workers and peasants must, as quickly as possible, seize everything that was created by them over many centuries and use it for their own interests." She insisted that anarchists could not guarantee positive social change: "The anarchists are not promising anything to anyone." She cautioned, "The anarchists only want people to be conscious of their own situation and seize freedom for themselves."Conflicts with Soviet authority

Upon returning to Russia in 1917, Nikiforova was influenced by Apollon Karelin, a veteran anarchist who advocated a tactical strategy of "Soviet anarchism." Meeting her in Petrograd, Karelin's political tactics encouraged anarchist participation in Soviet institutions with the long-term plan of directing them towards an anarchist agenda, provided these institutions did not deviate from revolutionary goals. In the event that they deviated from a radical agenda, anarchists were to rebel against them. Such institutional cooperation was widely disliked among anarchists, as they were largely a minority within such institutions, rendering their activity ineffectual. Nikiforova agreed to ally with the Bolsheviks under special circumstances and negotiated to have herself appointed to a soviet institution, briefly becoming the Deputy leader of the Oleksandrivsk Revolutionary committee (Soviet Union), revkom. She would go on to help establish footholds for Soviet power in several Ukrainian cities, demanding material support from Bolshevik agents in return, which she then used to pursue her anarchist agenda. While she allied herself with the Red Army on multiple occasions, she was constantly at odds with their commanders and personally antagonized several, arguing against some their practices on revolutionary grounds. Upon discovering that a Soviet commander was hoarding luxury goods looted from an aristocrat's home, she angrily confronted him for his selfishness. "The property of the estate owners doesn't belong to any particular detachment," she declared "but to the people as a whole. Let the people take what they want."Legacy

Postmortem mythology

Rumours about her alleged survival persisted after Nikiforova's death. In the years following her death, Nikiforova was rumoured to have become a Soviet spy in Paris, where she was alleged to have been involved in the assassination of the Ukrainian nationalist leader Symon Petliura by the Ukrainian Jewish anarchist Sholom Schwartzbard. Her legacy also created an opportunity for copycats, with a number of partisan women adopting the name of "Marusya" as a Pseudonym#Military and paramilitary organizations, pseudonym throughout the remainder of theUkrainian War of Independence

The Ukrainian War of Independence, also referred to as the Ukrainian–Soviet War in Ukraine, lasted from March 1917 to November 1921 and was part of the wider Russian Civil War. It saw the establishment and development of an independent Ukr ...

. In 1919, a 25-year-old Ukrainian nationalist school teacher adopted the name Marusya Sokolovska and took command her late brother's cavalry detachment, before she was captured by the Reds and shot. In 1920–1921, Marusya Chernaya () was also commander of a cavalry regiment in the Revolutionary Insurgent Army of Ukraine, before dying in battle against the Red Army. During the Tambov Rebellion in Russia, one of the rebel commanders was a woman named Marusya Kosova, who disappeared after the suppression of the revolt.

Historiography

Nikiforova's illicit activities meant that she left very few records during her life, only emerging as a public figure during her final years as a military commander. Available accounts of her life have either come from her military service record or from the memoirs of her contemporaries, such asNestor Makhno

Nestor Ivanovych Makhno (, ; 7 November 1888 – 25 July 1934), also known as Bat'ko Makhno ( , ), was a Ukrainians, Ukrainian anarchist revolutionary and the commander of the Revolutionary Insurgent Army of Ukraine during the Ukrainian War o ...

and Viktor Bilash.

Nikiforova's biography was largely neglected by Soviet historiography, which focused its women's history largely on female Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

, only ever referencing Nikiforova briefly and using negative depictions. She has likewise been largely neglected in History of Ukraine#National historiography, Ukrainian historiography, as her staunch anti-nationalist positions directly contradicted the historical narratives of Ukrainian nationalism, as well as History of anarchism, anarchist historiography, which has focused most of its attention on Nestor Makhno. Nevertheless, following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, there has been a renewed interest in Nikiforova, with several essays and a biography about her life being published during the 21st century.

See also

;Lists *List of guerrillas *List of military commanders *List of UkrainiansReferences

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

* * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Nikiforova, Maria Hryhorivna 1885 births 1919 deaths 20th-century anarchists 20th-century executions by Russia 20th-century Ukrainian women politicians Anarcho-communists Anti-nationalists Executed anarchists Executed Ukrainian women Female revolutionaries French military personnel of World War I Intersex military personnel Intersex politicians Intersex women LGBTQ military personnel Makhnovists Military personnel from Zaporizhzhia People of the Russian Revolution People of the Russian Civil War People convicted on terrorism charges People executed by Russia by firing squad Prisoners sentenced to death by the Russian Empire Politicians from Zaporizhzhia Soviet people of the Ukrainian–Soviet War Ukrainian anarchists Ukrainian guerrillas Ukrainian rebels Ukrainian revolutionaries Ukrainian women in World War I Women in the Russian Civil War Women in the Russian Revolution Women in the Ukrainian–Soviet War