Marc Brunel on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir Marc Isambard Brunel (, ; 25 April 1769 – 12 December 1849) was a French-American engineer active in the United States and Britain, most famous for the

During the summer of 1799 Brunel was introduced to

During the summer of 1799 Brunel was introduced to

Work began in February 1825, by sinking a vertical shaft on the

Work began in February 1825, by sinking a vertical shaft on the

After the completion of the Thames Tunnel, his greatest achievement, Brunel was in poor health. He never again accepted major commissions, although he did help his son, Isambard, on various projects. He was proud of his son's achievements, and was present at the launch of the SS ''Great Britain'' in

After the completion of the Thames Tunnel, his greatest achievement, Brunel was in poor health. He never again accepted major commissions, although he did help his son, Isambard, on various projects. He was proud of his son's achievements, and was present at the launch of the SS ''Great Britain'' in

Ancient Places TV: HD Video of Brunel (father and son) and the SS Great BritainThe Brunel Institute

– Collaborative venture between the SS Great Britain Trust and the University of Bristol. Housed alongside the at Bristol it includes the National Brunel Collection.

The Brunel Museum

– Based in Rotherhithe, London the museum is housed in the building that contained the pumps to keep the Thames Tunnel dry. {{DEFAULTSORT:Brunel, Marc Isambard 1769 births 1849 deaths French emigrants Immigrants to the United States Immigrants to the Kingdom of Great Britain French civil engineers English civil engineers British mechanical engineers British steam engine engineers Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Fellows of the Royal Society Machine tool builders Members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences Burials at Kensal Green Cemetery People associated with transport in London English prisoners and detainees English theatre architects Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh French mechanical engineers People imprisoned for debt 19th-century British engineers Knights Bachelor Family of Isambard Kingdom Brunel People from Eure People of the Industrial Revolution

civil engineering

Civil engineering is a regulation and licensure in engineering, professional engineering discipline that deals with the design, construction, and maintenance of the physical and naturally built environment, including public works such as roads ...

work he did in the latter. He is known for having overseen the process for and construction of the Thames Tunnel, for his work for the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

, and as father of the British civil and mechanical engineer, Isambard Kingdom Brunel

Isambard Kingdom Brunel ( ; 9 April 1806 – 15 September 1859) was an English civil engineer and mechanical engineer who is considered "one of the most ingenious and prolific figures in engineering history", "one of the 19th-century engi ...

.

Born in France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

, Brunel preferred his given name Isambard (but is generally known to history as Marc, to avoid confusion with his famous son). Brunel fled to the United States during the French Revolution, and involved himself in engineering and architectural pursuits, including offering an impressive design for the new United States Capitol Building in Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

After being naturalized in 1796, he was appointed Chief Engineer of New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

, and went on to design military, commercial, and other buildings.

He moved to London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

in 1799, where he married Sophia Kingdom. In Britain, his work as a mechanical engineer included the design of machinery to automate the production of pulley blocks for the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

, and he went on to design and patent a "shield" to protect tunneling workers, and to oversee construction of the Thames Tunnel. The tunnel opened on 25 March 1843 (later passing to railway companies and the London Underground

The London Underground (also known simply as the Underground or as the Tube) is a rapid transit system serving Greater London and some parts of the adjacent home counties of Buckinghamshire, Essex and Hertfordshire in England.

The Undergro ...

), and remains in use today.

The events of Brunel's life spanned from a period of indebtedness and prison over failed business ventures, to his being knighted

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of a knighthood by a head of state (including the pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church, or the country, especially in a military capacity.

The concept of a knighthood ...

by the young Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in January 1901. Her reign of 63 year ...

(in 1841), in anticipation of his successful completion of the Thames Tunnel, recognition preceded by his being named, in sequence, beginning in 1814, to the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

(Fellow), the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences () is one of the Swedish Royal Academies, royal academies of Sweden. Founded on 2 June 1739, it is an independent, non-governmental scientific organization that takes special responsibility for promoting nat ...

, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (The Academy) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, and other ...

, and following the tunnel's completion, his being named an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh

The Royal Society of Edinburgh (RSE) is Scotland's national academy of science and letters. It is a registered charity that operates on a wholly independent and non-partisan basis and provides public benefit throughout Scotland. It was establis ...

(in 1845).

Early life in France

Brunel was the second son of Jean Charles Brunel and Marie-Victoire Lefebvre. Jean Charles was a prosperous farmer in Hacqueville, Normandy, and Marc was born on the family farm. It was customary in prosperous families for the first son to inherit the family land and the second son to enter the priesthood. His father therefore started Marc on a classical education, but he showed no liking for Greek or Latin and instead showed himself proficient in drawing and mathematics. He was also very musical from an early age. At the age of eleven he was sent to aseminary

A seminary, school of theology, theological college, or divinity school is an educational institution for educating students (sometimes called seminarians) in scripture and theology, generally to prepare them for ordination to serve as cle ...

in Rouen

Rouen (, ; or ) is a city on the River Seine, in northwestern France. It is in the prefecture of Regions of France, region of Normandy (administrative region), Normandy and the Departments of France, department of Seine-Maritime. Formerly one ...

. The superior of the seminary allowed him to learn carpentry, and he soon achieved the standards of a cabinetmaker. He also sketched ships in the local harbour. As he showed no desire to become a priest, his father sent him to stay with relatives in Rouen, where a family friend tutored him on naval matters. In 1786, as a result of this tuition, Marc became a naval cadet on a French frigate and during his service visited the West Indies several times. He made an octant for himself from brass and ivory, and used it during his service.

In 1789, during Brunel's service abroad, the French Revolution began. In January 1792 Brunel's frigate paid off its crew, and Brunel returned to live with his relatives in Rouen. He was a Royalist sympathiser, as were most of the inhabitants of Normandy. In January 1793, whilst visiting Paris during the trial of Louis XVI

Louis XVI (Louis-Auguste; ; 23 August 1754 – 21 January 1793) was the last king of France before the fall of the monarchy during the French Revolution. The son of Louis, Dauphin of France (1729–1765), Louis, Dauphin of France (son and heir- ...

, Brunel unwisely publicly predicted the demise of Robespierre

Maximilien François Marie Isidore de Robespierre (; ; 6 May 1758 – 28 July 1794) was a French lawyer and statesman, widely recognised as one of the most influential and controversial figures of the French Revolution. Robespierre fer ...

, one of the leaders of the Revolution. He was lucky to get out of Paris with his life, and returned to Rouen. However, it was evident that he would have to leave France. During his stay in Rouen, Brunel had met Sophia Kingdom, a young English woman who was an orphan and was working as a governess. He was forced to leave her behind when he fled to Le Havre

Le Havre is a major port city in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy (administrative region), Normandy region of northern France. It is situated on the right bank of the estuary of the Seine, river Seine on the English Channel, Channe ...

and boarded the American ship ''Liberty'', bound for New York.

United States

Per the account of R. Anthony Hyman,Brunel... a royalist... after service on a corvette escaped to the United States. There he worked for six years as architect and engineer, taking American citizenship.Hyman, p. 144Brunel arrived in New York on 6 September 1793, and he subsequently travelled to

Philadelphia

Philadelphia ( ), colloquially referred to as Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, most populous city in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania and the List of United States cities by population, sixth-most populous city in the Unit ...

and Albany. He got involved in a scheme to link the Hudson River

The Hudson River, historically the North River, is a river that flows from north to south largely through eastern New York (state), New York state. It originates in the Adirondack Mountains at Henderson Lake (New York), Henderson Lake in the ...

by canal with Lake Champlain

Lake Champlain ( ; , ) is a natural freshwater lake in North America. It mostly lies between the U.S. states of New York (state), New York and Vermont, but also extends north into the Canadian province of Quebec.

The cities of Burlington, Ve ...

, and also submitted a design for the new Capitol building to be built in Washington. The judges were very impressed with the design, but it was not selected.

In 1796, after taking citizenship, Brunel was appointed chief engineer of the city of New York. He designed various houses, docks, commercial buildings, an arsenal, and a cannon factory. No official records exist of the projects that he carried out in New York, as it seems likely that the documents were destroyed in the New York draft riots of 1863. In 1798, during a dinner conversation, Brunel learnt of the difficulties that the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

had in obtaining the 100,000 pulley blocks that it needed each year. Each of these was made by hand. Brunel quickly produced an outline design of a set of machines that would automate their production. He decided to sail to England and put his invention before the Admiralty. He sailed for England on 7 February 1799 with a letter of introduction to the Navy Minister, and on 7 March his ship, ''Halifax'', landed at Falmouth.

Britain

While Brunel was in the United States, Sophia Kingdom had remained in Rouen and during theReign of Terror

The Reign of Terror (French: ''La Terreur'', literally "The Terror") was a period of the French Revolution when, following the creation of the French First Republic, First Republic, a series of massacres and Capital punishment in France, nu ...

, she was arrested as an English spy and daily expected to be executed. She was only saved by the fall of Robespierre

Maximilien François Marie Isidore de Robespierre (; ; 6 May 1758 – 28 July 1794) was a French lawyer and statesman, widely recognised as one of the most influential and controversial figures of the French Revolution. Robespierre fer ...

in June 1794. In April 1795 Kingdom was able to leave France and travel to London.

When Brunel arrived from the United States, he immediately travelled to London and made contact with Kingdom. They were married on 1 November 1799 at St Andrew, Holborn. In 1801 she gave birth to their first child, a daughter, Sophia;Baptism Register accounts as baptism 27.1.01 in 1804 their second daughter Emma; and in 1806 their son Isambard Kingdom, who became a great engineer. Isambard Kingdom grew up in Lindsey House in Chelsea, London

Chelsea is an area in West London, England, due south-west of Kilometre zero#Great Britain, Charing Cross by approximately . It lies on the north bank of the River Thames and for postal purposes is part of the SW postcode area, south-western p ...

.

Henry Maudslay

Henry Maudslay ( pronunciation and spelling) (22 August 1771 – 14 February 1831) was an English machine tool innovator, tool and die maker, and inventor. He is considered a founding father of machine tool technology. His inventions were a ...

, a talented engineer who had worked for Joseph Bramah

Joseph Bramah (13 April 1748 – 9 December 1814) was an English inventor and locksmith. He is best known for having improved the flush toilet and inventing the hydraulic press. Along with William Armstrong, 1st Baron Armstrong, he can be cons ...

, and had recently started his own business. Maudslay made working models of the machines for making pulley

Sheave without a rope

A pulley is a wheel on an axle or shaft enabling a taut cable or belt passing over the wheel to move and change direction, or transfer power between itself and a shaft.

A pulley may have a groove or grooves between flan ...

blocks, and Brunel approached Samuel Bentham

Brigadier General Sir Samuel Bentham (11 January 1757 – 31 May 1831) was an England, English mechanical engineering, mechanical engineer and naval architect credited with numerous innovations, particularly related to naval architecture, incl ...

, the Inspector General of Naval Works. In April 1802 Bentham recommended the installation of Brunel's block-making machinery at Portsmouth Block Mills. Brunel's machine could be operated by unskilled workers, at ten times the previous rate of production. Altogether 45 machines were installed at Portsmouth, and by 1808 the plant was producing 130,000 blocks per year. Unfortunately for Brunel, the Admiralty vacillated over payment, despite the fact that Brunel had spent more than £2,000 of his own money on the project. In August 1808 they agreed to pay £1,000 on account, and two years later they consented to a payment of just over £17,000.

Brunel was a talented mechanical engineer, and did much to develop sawmill machinery, undertaking contracts for the British Government

His Majesty's Government, abbreviated to HM Government or otherwise UK Government, is the central government, central executive authority of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

at Chatham and Woolwich

Woolwich () is a town in South London, southeast London, England, within the Royal Borough of Greenwich.

The district's location on the River Thames led to its status as an important naval, military and industrial area; a role that was mainta ...

dockyards, building on his experience at the Portsmouth Block Mills. He built a sawmill at Battersea

Battersea is a large district in southwest London, part of the London Borough of Wandsworth, England. It is centred southwest of Charing Cross and also extends along the south bank of the Thames Tideway. It includes the Battersea Park.

Hist ...

, London (burnt down in 1814 and rebuilt by 1816), which was designed to produce veneers, and he also designed sawmills for entrepreneurs. He also developed machinery for mass-producing soldiers' boots, but before this could reach full production, demand ceased due to the end of the Napoleonic Wars. Brunel was made a Fellow of the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

in 1814. In 1828, he was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences () is one of the Swedish Royal Academies, royal academies of Sweden. Founded on 2 June 1739, it is an independent, non-governmental scientific organization that takes special responsibility for promoting nat ...

. Brunel was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (The Academy) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, and other ...

in 1834. In 1845 he was elected an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh

The Royal Society of Edinburgh (RSE) is Scotland's national academy of science and letters. It is a registered charity that operates on a wholly independent and non-partisan basis and provides public benefit throughout Scotland. It was establis ...

.

Debtors' prison

Despite an historically successful endeavor—a "pioneering enterprise in mass production"—in the automation of block manufacturing, and his recognition in 1814 as aRoyal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

Fellow, the payment difficulties experienced with the Admiralty and further unprofitable ventures led, by early 1821, to Burnel's being deeply in debt; in May of that year he was tried, and then committed to the King's Bench Prison

The King's Bench Prison was a prison in Southwark, south London, England, from the Middle Ages until it closed in 1880. It took its name from the King's Bench court of law in which cases of defamation, bankruptcy and other misdemeanours were he ...

(a debtors' prison

A debtors' prison is a prison for people who are unable to pay debt. Until the mid-19th century, debtors' prisons (usually similar in form to locked workhouses) were a common way to deal with unpaid debt in Western Europe.Cory, Lucinda"A Histor ...

) in Southwark

Southwark ( ) is a district of Central London situated on the south bank of the River Thames, forming the north-western part of the wider modern London Borough of Southwark. The district, which is the oldest part of South London, developed ...

. Prisoners in a debtors' prison were allowed to have their family with them, and Sophia accompanied him. Brunel spent 88 days incarcerated. As time passed with no prospect of gaining release, Brunel began to correspond with Alexander I of Russia

Alexander I (, ; – ), nicknamed "the Blessed", was Emperor of Russia from 1801, the first king of Congress Poland from 1815, and the grand duke of Finland from 1809 to his death in 1825. He ruled Russian Empire, Russia during the chaotic perio ...

about the possibility of moving with his family to St Petersburg

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the List of cities and towns in Russia by population, second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the Neva, River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland ...

to work for the Tsar

Tsar (; also spelled ''czar'', ''tzar'', or ''csar''; ; ; sr-Cyrl-Latn, цар, car) is a title historically used by Slavic monarchs. The term is derived from the Latin word '' caesar'', which was intended to mean ''emperor'' in the Euro ...

. As soon as it was learnt that Britain was likely to lose such an eminent engineer as Brunel, influential figures, such as the Duke of Wellington

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and above sovereign princes. As royalty or nobility, they ar ...

, began to press for government intervention. The government granted £5,000 to clear Brunel's debts on condition that he abandon any plans to go to Russia. As a result, Brunel was released from prison in August.

Thames Tunnel

In 1805 the Thames Archway Company was formed with the intention of driving a tunnel beneath the Thames betweenRotherhithe

Rotherhithe ( ) is a district of South London, England, and part of the London Borough of Southwark. It is on a peninsula on the south bank of the Thames, facing Wapping, Shadwell and Limehouse on the north bank, with the Isle of Dogs to the ea ...

and Limehouse

Limehouse is a district in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets in East London. It is east of Charing Cross, on the northern bank of the River Thames. Its proximity to the river has given it a strong maritime character, which it retains throu ...

. Richard Trevithick

Richard Trevithick (13 April 1771 – 22 April 1833) was a British inventor and mining engineer. The son of a mining captain, and born in the mining heartland of Cornwall, Trevithick was immersed in mining and engineering from an early age. He ...

was engaged by the company to construct the tunnel. He used Cornish miners to work on the tunnel. In 1807 the tunnel encountered quicksand and conditions became difficult and dangerous. Eventually the tunnel was abandoned after more than 1,000 feet had been completed, and expert opinion, led by William Jessop, was that such a tunnel was impracticable.

Brunel had already drawn up plans for a tunnel under the River Neva in Russia, but this scheme never came to fruition. In 1818 Brunel had patented a tunnelling shield. This was a reinforced shield of cast iron in which miners would work in separate compartments, digging at the tunnel-face. Periodically the shield would be driven forward by large jacks, and the tunnel surface behind it would be lined with brick. It is claimed that Brunel found the inspiration for his tunnelling shield from the shipworm

The shipworms, also called teredo worms or simply teredo (, via Latin ), are marine bivalve molluscs in the family Teredinidae, a group of saltwater clams with long, soft, naked bodies. They are notorious for boring into (and commonly eventual ...

, ''Teredo navalis

''Teredo navalis'', commonly called the naval shipworm or turu, is a species of saltwater clam, a marine bivalve mollusc in the family '' Teredinidae''. This species is the type species of the genus '' Teredo''. Like other species in this family ...

'', which has its head protected by a hard shell whilst it bores through ships' timbers.

Brunel's invention provided the basis for subsequent tunnelling shields used to build the London Underground

The London Underground (also known simply as the Underground or as the Tube) is a rapid transit system serving Greater London and some parts of the adjacent home counties of Buckinghamshire, Essex and Hertfordshire in England.

The Undergro ...

system and many other tunnels. Brunel was so convinced that he could use such a tunnelling shield to dig a tunnel under the Thames, that he wrote to every person of influence who might be interested. At last in February 1824 a meeting was held and 2,128 shares at £50 each were subscribed for. In June 1824 the Thames Tunnel Company was incorporated by royal assent. The tunnel was intended for horse-drawn traffic.

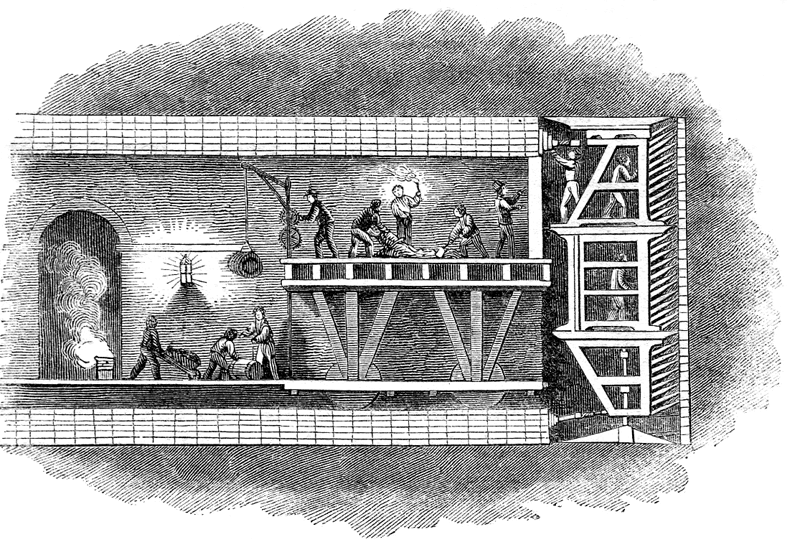

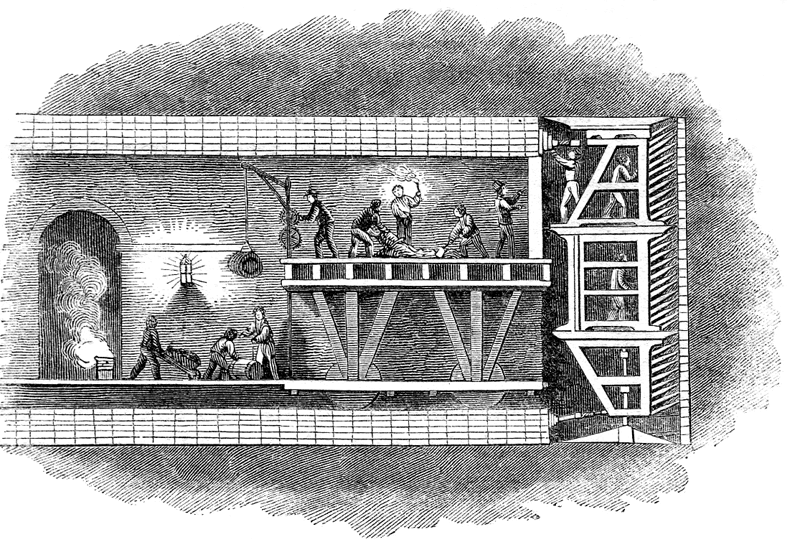

Work began in February 1825, by sinking a vertical shaft on the

Work began in February 1825, by sinking a vertical shaft on the Rotherhithe

Rotherhithe ( ) is a district of South London, England, and part of the London Borough of Southwark. It is on a peninsula on the south bank of the Thames, facing Wapping, Shadwell and Limehouse on the north bank, with the Isle of Dogs to the ea ...

bank. This was done by constructing a 50-foot-diameter metal ring, upon which a circular brick tower was built. As the tower rose in height, its weight forced the ring into the ground. At the same time, workmen excavated the earth in the centre of the ring. This vertical shaft was completed in November 1825, and the tunnelling shield, which had been manufactured at Lambeth

Lambeth () is a district in South London, England, which today also gives its name to the (much larger) London Borough of Lambeth. Lambeth itself was an ancient parish in the county of Surrey. It is situated 1 mile (1.6 km) south of Charin ...

by Henry Maudslay

Henry Maudslay ( pronunciation and spelling) (22 August 1771 – 14 February 1831) was an English machine tool innovator, tool and die maker, and inventor. He is considered a founding father of machine tool technology. His inventions were a ...

's company, was then assembled at the bottom. Maudslay also supplied the steam powered pumps for the project.

The shield was rectangular in cross section, and consisted of twelve frames, side by side, each of which could be moved forward independently of the others. Each frame contained three compartments, one above the other, each big enough for one man to excavate the tunnel face. The whole frame accommodated 36 miners. When enough material had been removed from the tunnel face, the frame was moved forward by large jacks. As the shield moved forward, bricklayers followed, lining the walls. The tunnel required over 7.5 million bricks.

Problems

Brunel was assisted in his work by his son,Isambard Kingdom Brunel

Isambard Kingdom Brunel ( ; 9 April 1806 – 15 September 1859) was an English civil engineer and mechanical engineer who is considered "one of the most ingenious and prolific figures in engineering history", "one of the 19th-century engi ...

, now 18 years old. Brunel had planned the tunnel to pass no more than fourteen feet below the riverbed at its lowest point. This caused problems later. Another problem that hindered Brunel was that William Smith, the chairman of the company, thought that the tunnelling shield was an unnecessary luxury, and that the tunnel could be made more cheaply by traditional methods. He wanted Brunel replaced as Chief Engineer and constantly tried to undermine his position. The shield quickly proved its worth. During the tunnelling both Brunel and his assistant engineer suffered ill health and for a while Isambard had to bear the whole burden of the work.

There were several instances of flooding at the tunnel face due to its nearness to the bed of the river. In May 1827 it was necessary to plug an enormous hole that appeared on the riverbed. The resources of the Thames Tunnel Company were consumed, and despite efforts to raise more money, the tunnel was sealed up in August 1828. Brunel resigned from his position, frustrated by the continued opposition from the chairman. He undertook various civil engineering projects, including helping his son, Isambard, with his design of the Clifton Suspension Bridge.

In March 1832 William Smith was deposed as chairman of the Thames Tunnel Company. He had been a thorn in Brunel's side throughout the project. In 1834 the government agreed a loan of £246,000 to the Thames Tunnel Company. The old 80-ton tunnelling shield was removed and replaced by a new improved 140-ton shield consisting of 9,000 parts that had to be fitted together underground. Tunnelling was resumed but there were still instances of flooding in which the pumps were overwhelmed. Miners were affected by the constant influx of polluted water, and many fell ill. As the tunnel approached the Wapping shore, work began on sinking a vertical shaft similar to the Rotherhithe one. This began in 1840 and took thirteen months to complete.

On 24 March 1841 Brunel was knighted

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of a knighthood by a head of state (including the pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church, or the country, especially in a military capacity.

The concept of a knighthood ...

by the young Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in January 1901. Her reign of 63 year ...

. This was at the suggestion of Prince Albert

Prince Albert most commonly refers to:

*Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (1819–1861), consort of Queen Victoria

*Albert II, Prince of Monaco (born 1958), present head of state of Monaco

Prince Albert may also refer to:

Royalty

* Alb ...

who had shown keen interest in the progress of the tunnel. The tunnel opened on the Wapping side of the river on 1 August 1842. On 7 November 1842 Brunel suffered a stroke that paralysed his right side for a time. The Thames Tunnel officially opened on 25 March 1843. Brunel, despite ill health, took part in the opening ceremony. Within 15 weeks of opening, one million people visited the tunnel. On 26 July 1843 Queen Victoria and Prince Albert visited. Although intended for horse-drawn traffic, the tunnel remained pedestrian only.

Later developments

In 1865 the East London Railway Company purchased the Thames Tunnel for £200,000 and four years later the first trains passed through it. The tunnel became part of theLondon Underground

The London Underground (also known simply as the Underground or as the Tube) is a rapid transit system serving Greater London and some parts of the adjacent home counties of Buckinghamshire, Essex and Hertfordshire in England.

The Undergro ...

system, and remains in use today, as part of the East London Line of London Overground

London Overground (also known simply as the Overground) is a Urban rail in the United Kingdom, suburban rail network serving London and its environs. Established in 2007 to take over Silverlink Metro routes, it now serves a large part of Greate ...

.

The engine house in Rotherhithe was taken over by a charitable trust in 1975 and transformed into the Brunel Museum in 2006.

Subsequent life

After the completion of the Thames Tunnel, his greatest achievement, Brunel was in poor health. He never again accepted major commissions, although he did help his son, Isambard, on various projects. He was proud of his son's achievements, and was present at the launch of the SS ''Great Britain'' in

After the completion of the Thames Tunnel, his greatest achievement, Brunel was in poor health. He never again accepted major commissions, although he did help his son, Isambard, on various projects. He was proud of his son's achievements, and was present at the launch of the SS ''Great Britain'' in Bristol

Bristol () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city, unitary authority area and ceremonial county in South West England, the most populous city in the region. Built around the River Avon, Bristol, River Avon, it is bordered by t ...

on 19 July 1843. In 1845 Brunel suffered another, more severe stroke and was almost totally paralysed on his right side. On 12 December 1849, Brunel died at the age of 80, and his remains were interred in Kensal Green Cemetery

Kensal Green Cemetery is a cemetery in the Kensal Green area of North Kensington in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea and the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham in London, England. Inspired by Père Lachaise Cemetery in P ...

in London. His wife, Sophia, was subsequently interred in the same plot, followed by their son, Isambard, just 10 years later.

References

Citations

Sources

* * * * * * * *Further reading

* * Reprinted byMcGraw-Hill

McGraw Hill is an American education science company that provides educational content, software, and services for students and educators across various levels—from K-12 to higher education and professional settings. They produce textbooks, ...

, New York and London, 1926 (); and by Lindsay Publications, Inc., Bradley, Illinois, ().

External links

Ancient Places TV: HD Video of Brunel (father and son) and the SS Great Britain

– Collaborative venture between the SS Great Britain Trust and the University of Bristol. Housed alongside the at Bristol it includes the National Brunel Collection.

The Brunel Museum

– Based in Rotherhithe, London the museum is housed in the building that contained the pumps to keep the Thames Tunnel dry. {{DEFAULTSORT:Brunel, Marc Isambard 1769 births 1849 deaths French emigrants Immigrants to the United States Immigrants to the Kingdom of Great Britain French civil engineers English civil engineers British mechanical engineers British steam engine engineers Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Fellows of the Royal Society Machine tool builders Members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences Burials at Kensal Green Cemetery People associated with transport in London English prisoners and detainees English theatre architects Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh French mechanical engineers People imprisoned for debt 19th-century British engineers Knights Bachelor Family of Isambard Kingdom Brunel People from Eure People of the Industrial Revolution