The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

that produced the first

nuclear weapon

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions ( thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bom ...

s. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project was under the direction of Major General

Leslie Groves

Lieutenant General Leslie Richard Groves Jr. (17 August 1896 – 13 July 1970) was a United States Army Corps of Engineers officer who oversaw the construction of the Pentagon and directed the Manhattan Project, a top secret research project ...

of the

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

, colors =

, anniversaries = 16 June (Organization Day)

, battles =

, battles_label = Wars

, website =

, commander1 = ...

. Nuclear physicist

Robert Oppenheimer

J. Robert Oppenheimer (; April 22, 1904 – February 18, 1967) was an American theoretical physicist. A professor of physics at the University of California, Berkeley, Oppenheimer was the wartime head of the Los Alamos Laboratory and is often ...

was the director of the

Los Alamos Laboratory

The Los Alamos Laboratory, also known as Project Y, was a secret laboratory established by the Manhattan Project and operated by the University of California during World War II. Its mission was to design and build the first atomic bombs. Rob ...

that designed the actual bombs. The Army component of the project was designated the Manhattan District as its first headquarters were in

Manhattan

Manhattan (), known regionally as the City, is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the five Boroughs of New York City, boroughs of New York City. The borough is also coextensive with New York County, one of the List of co ...

; the placename gradually superseded the official codename, Development of Substitute Materials, for the entire project. Along the way, the project absorbed its earlier British counterpart,

Tube Alloys

Tube Alloys was the research and development programme authorised by the United Kingdom, with participation from Canada, to develop nuclear weapons during the Second World War. Starting before the Manhattan Project in the United States, the Bri ...

. The Manhattan Project began modestly in 1939, but grew to employ more than 130,000 people and cost nearly US$2 billion (equivalent to about $ billion in ). Over 90 percent of the cost was for building factories and to produce

fissile material

In nuclear engineering, fissile material is material capable of sustaining a nuclear fission chain reaction. By definition, fissile material can sustain a chain reaction with neutrons of thermal energy. The predominant neutron energy may be typi ...

, with less than 10 percent for development and production of the weapons. Research and production took place at more than thirty sites across the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada.

The project led to the development of two types of atomic bombs, both developed concurrently, during the war: a relatively simple

gun-type fission weapon

Gun-type fission weapons are fission-based nuclear weapons whose design assembles their fissile material into a supercritical mass by the use of the "gun" method: shooting one piece of sub-critical material into another. Although this is someti ...

and a more complex

implosion-type nuclear weapon

Nuclear weapon designs are physical, chemical, and engineering arrangements that cause the physics package of a nuclear weapon to detonate. There are three existing basic design types:

* pure fission weapons, the simplest and least technicall ...

. The

Thin Man gun-type design proved impractical to use with

plutonium

Plutonium is a radioactive chemical element with the symbol Pu and atomic number 94. It is an actinide metal of silvery-gray appearance that tarnishes when exposed to air, and forms a dull coating when oxidized. The element normally exhib ...

, so a simpler gun-type called

Little Boy

"Little Boy" was the type of atomic bomb dropped on the Japanese city of Hiroshima on 6 August 1945 during World War II, making it the first nuclear weapon used in warfare. The bomb was dropped by the Boeing B-29 Superfortress '' Enola Gay ...

was developed that used

uranium-235

Uranium-235 (235U or U-235) is an Isotopes of uranium, isotope of uranium making up about 0.72% of natural uranium. Unlike the predominant isotope uranium-238, it is fissile, i.e., it can sustain a nuclear chain reaction. It is the only fissile ...

, an

isotope

Isotopes are two or more types of atoms that have the same atomic number (number of protons in their nuclei) and position in the periodic table (and hence belong to the same chemical element), and that differ in nucleon numbers ( mass number ...

that makes up only 0.7 percent of natural

uranium

Uranium is a chemical element with the symbol U and atomic number 92. It is a silvery-grey metal in the actinide series of the periodic table. A uranium atom has 92 protons and 92 electrons, of which 6 are valence electrons. Uranium is weakly ...

. Because it is chemically identical to the most common isotope,

uranium-238

Uranium-238 (238U or U-238) is the most common isotope of uranium found in nature, with a relative abundance of 99%. Unlike uranium-235, it is non-fissile, which means it cannot sustain a chain reaction in a thermal-neutron reactor. However ...

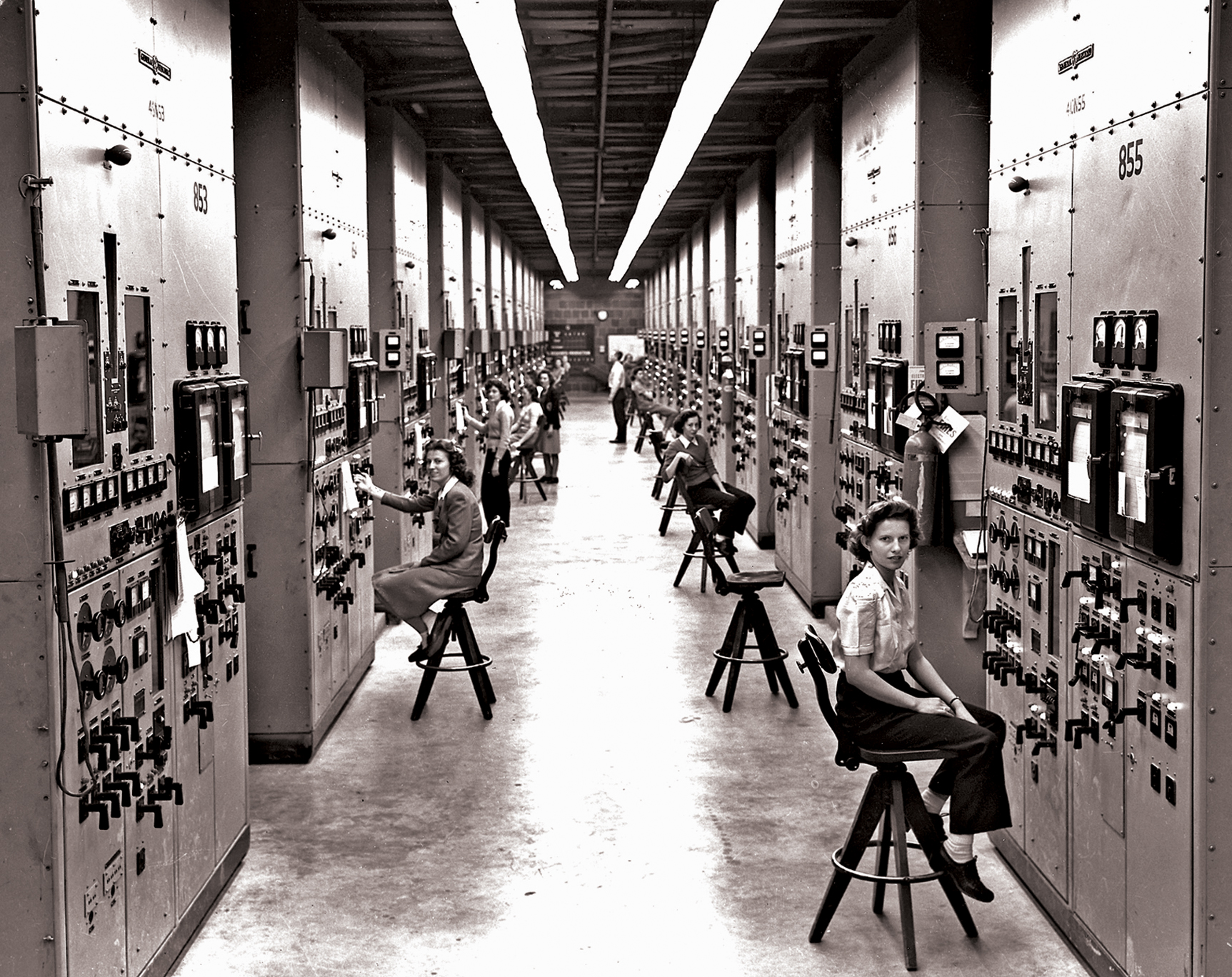

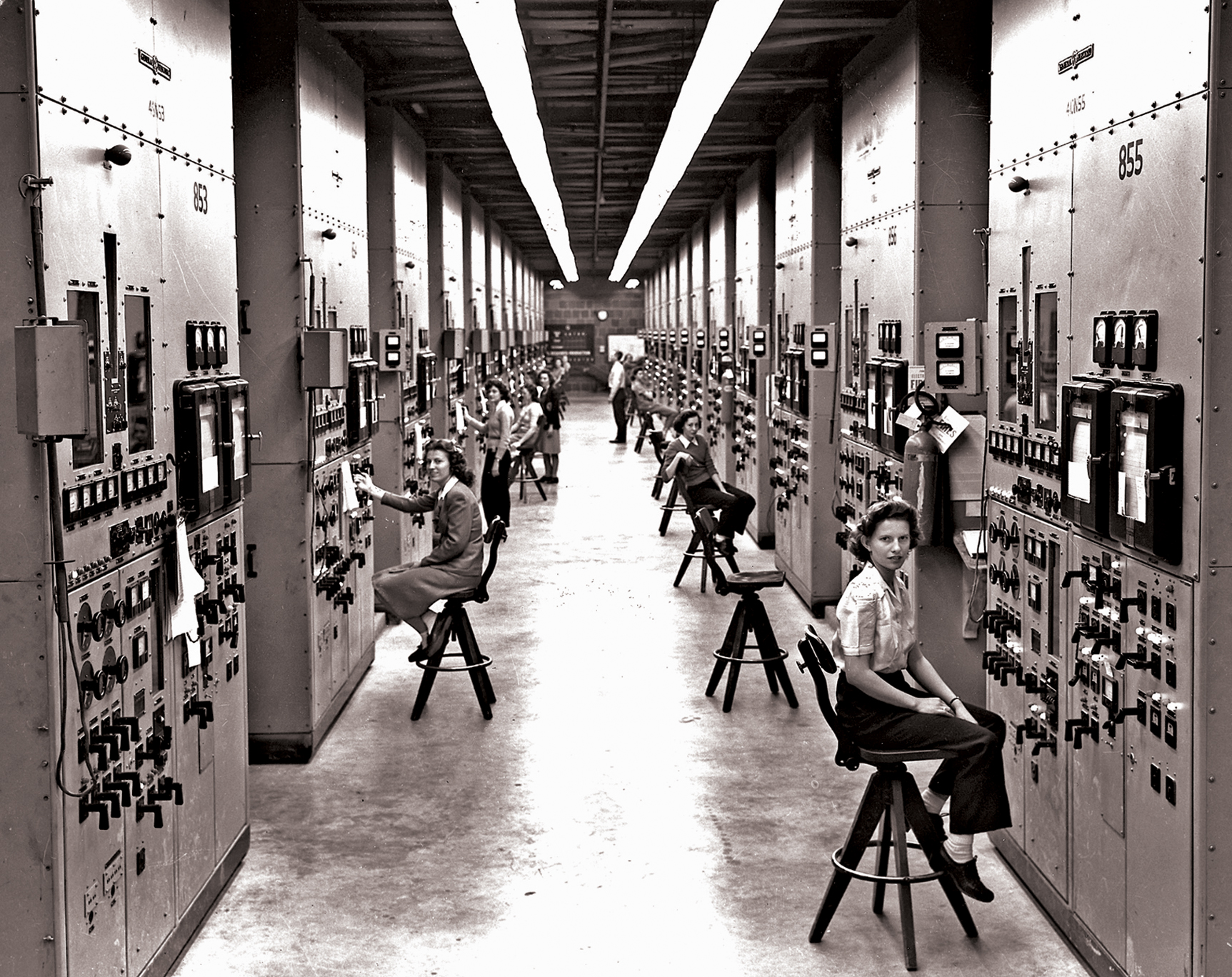

, and has almost the same mass, separating the two proved difficult. Three methods were employed for

uranium enrichment

Enriched uranium is a type of uranium in which the percent composition of uranium-235 (written 235U) has been increased through the process of isotope separation. Naturally occurring uranium is composed of three major isotopes: uranium-238 (238 ...

:

electromagnetic

In physics, electromagnetism is an interaction that occurs between particles with electric charge. It is the second-strongest of the four fundamental interactions, after the strong force, and it is the dominant force in the interactions of a ...

,

gaseous

Gas is one of the four fundamental states of matter (the others being solid, liquid, and plasma).

A pure gas may be made up of individual atoms (e.g. a noble gas like neon), elemental molecules made from one type of atom (e.g. oxygen), or c ...

and

thermal

A thermal column (or thermal) is a rising mass of buoyant air, a convective current in the atmosphere, that transfers heat energy vertically. Thermals are created by the uneven heating of Earth's surface from solar radiation, and are an example ...

. Scientists conducted most of this work at the

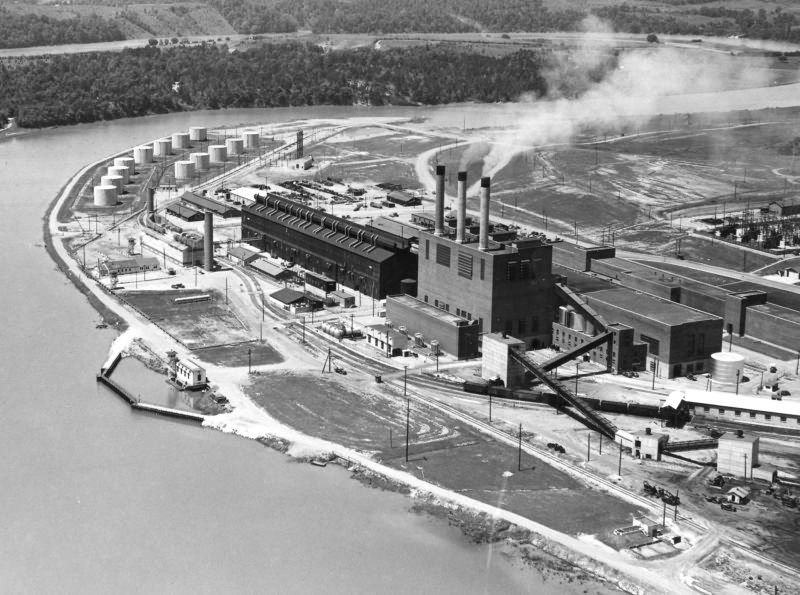

Clinton Engineer Works

The Clinton Engineer Works (CEW) was the production installation of the Manhattan Project that during World War II produced the enriched uranium used in the 1945 bombing of Hiroshima, as well as the first examples of reactor-produced pluton ...

at

Oak Ridge, Tennessee

Oak Ridge is a city in Anderson and Roane counties in the eastern part of the U.S. state of Tennessee, about west of downtown Knoxville. Oak Ridge's population was 31,402 at the 2020 census. It is part of the Knoxville Metropolitan Area. O ...

.

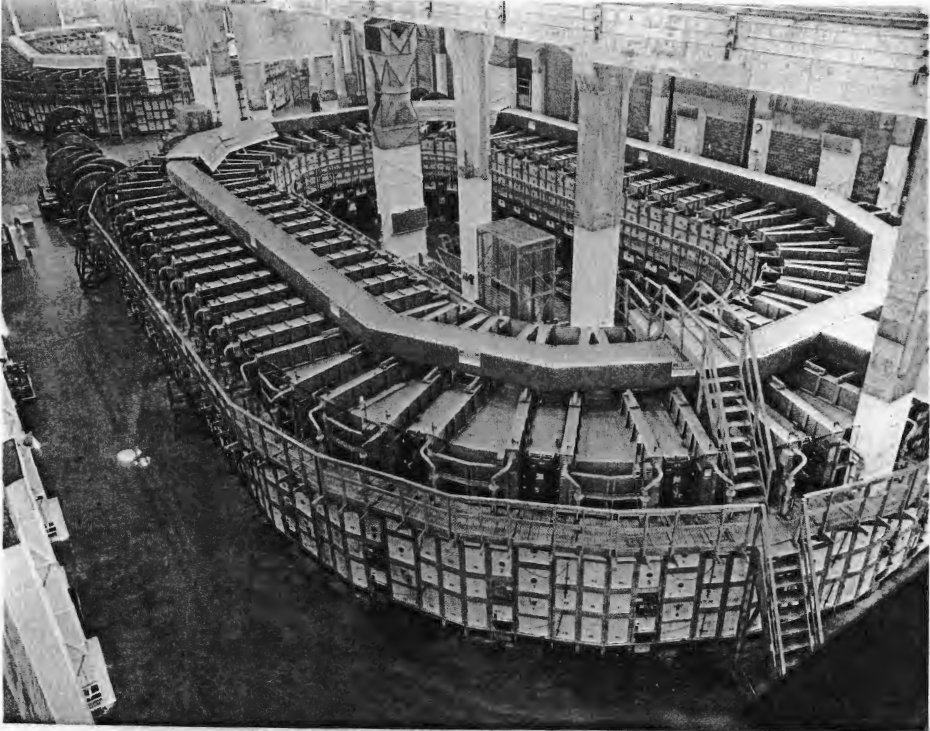

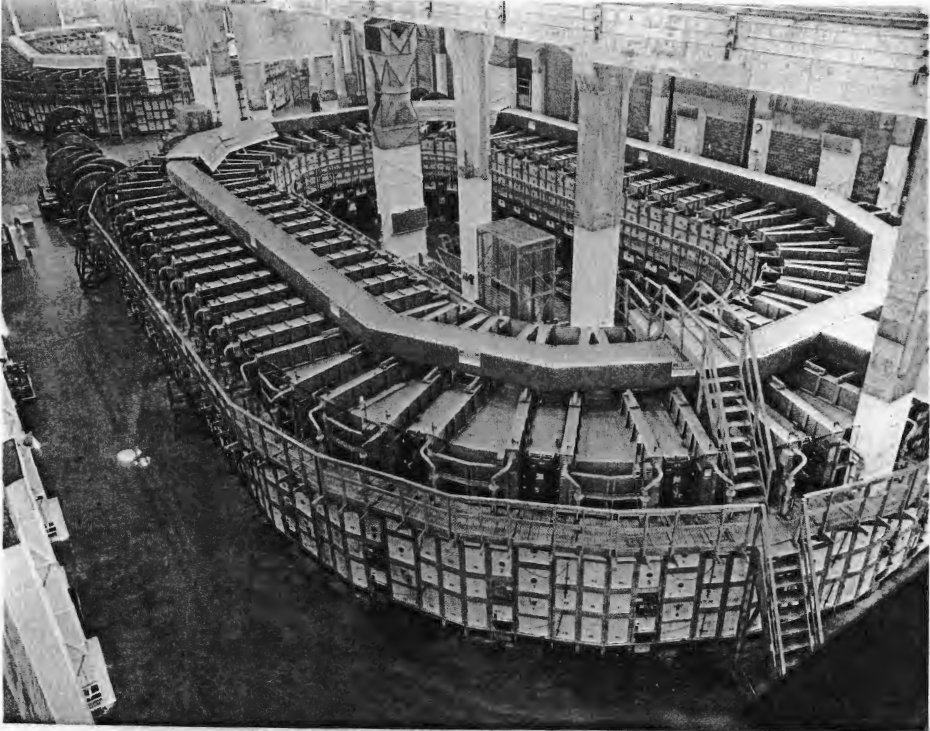

In parallel with the work on uranium was an effort to produce plutonium, which researchers at the

University of California, Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California) is a public land-grant research university in Berkeley, California. Established in 1868 as the University of California, it is the state's first land-grant u ...

, discovered in 1940. After the feasibility of the world's first artificial nuclear reactor, the

Chicago Pile-1

Chicago Pile-1 (CP-1) was the world's first artificial nuclear reactor. On 2 December 1942, the first human-made self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction was initiated in CP-1, during an experiment led by Enrico Fermi. The secret development of t ...

, was demonstrated in 1942 at the

Metallurgical Laboratory

The Metallurgical Laboratory (or Met Lab) was a scientific laboratory at the University of Chicago that was established in February 1942 to study and use the newly discovered chemical element plutonium. It researched plutonium's chemistry and m ...

in the

University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, U of C, or UChi) is a private university, private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Its main campus is located in Chicago's Hyde Park, Chicago, Hyde Park neighborhood. The University of Chic ...

, the project designed the

X-10 Graphite Reactor at Oak Ridge and the production reactors at the

Hanford Site

The Hanford Site is a decommissioned nuclear production complex operated by the United States federal government on the Columbia River in Benton County in the U.S. state of Washington. The site has been known by many names, including SiteW ...

in

Washington state

Washington (), officially the State of Washington, is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. Named for George Washington—the first U.S. president—the state was formed from the western part of the Washingto ...

, in which uranium was irradiated and

transmuted into plutonium. The plutonium was then chemically separated from the uranium, using the

bismuth phosphate process

The bismuth-phosphate process was used to extract plutonium from irradiated uranium taken from nuclear reactors. It was developed during World War II by Stanley G. Thompson, a chemist working for the Manhattan Project at the University of Califor ...

. The

Fat Man

"Fat Man" (also known as Mark III) is the codename for the type of nuclear bomb the United States Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki#Bombing of Nagasaki, detonated over the Japanese city of Nagasaki on 9 August 1945. It was the second ...

plutonium implosion-type weapon was developed in a concerted design and development effort by the Los Alamos Laboratory.

The project was also charged with gathering intelligence on the

German nuclear weapon project

The Uranverein ( en, "Uranium Club") or Uranprojekt ( en, "Uranium Project") was the name given to the project in Germany to research nuclear technology, including nuclear weapons and nuclear reactors, during World War II. It went through seve ...

. Through

Operation Alsos

The Alsos Mission was an organized effort by a team of British and United States military, scientific, and intelligence personnel to discover enemy scientific developments during World War II. Its chief focus was on the German nuclear energy pro ...

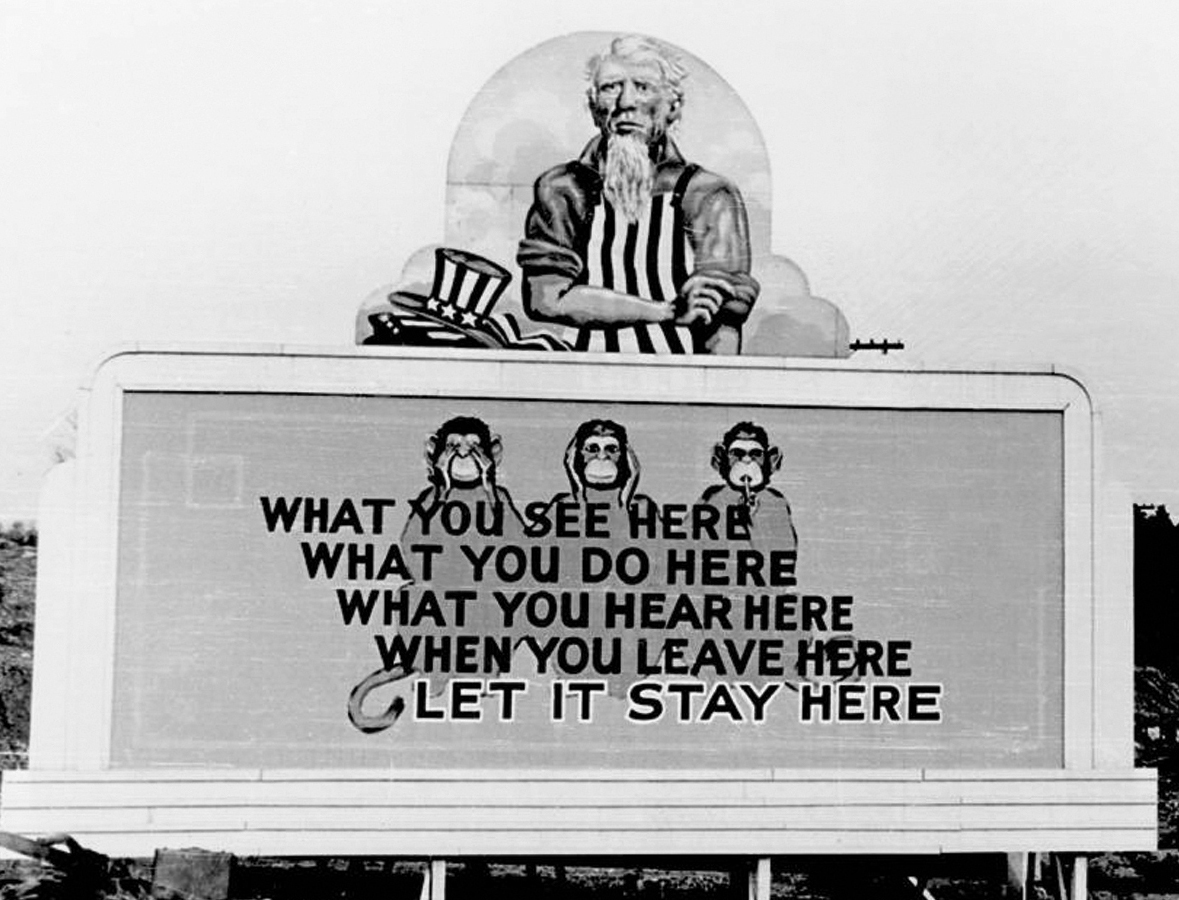

, Manhattan Project personnel served in Europe, sometimes behind enemy lines, where they gathered nuclear materials and documents, and rounded up German scientists. Despite the Manhattan Project's tight security, Soviet

atomic spies

Atomic spies or atom spies were people in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada who are known to have illicitly given information about nuclear weapons production or design to the Soviet Union during World War II and the early ...

successfully penetrated the program.

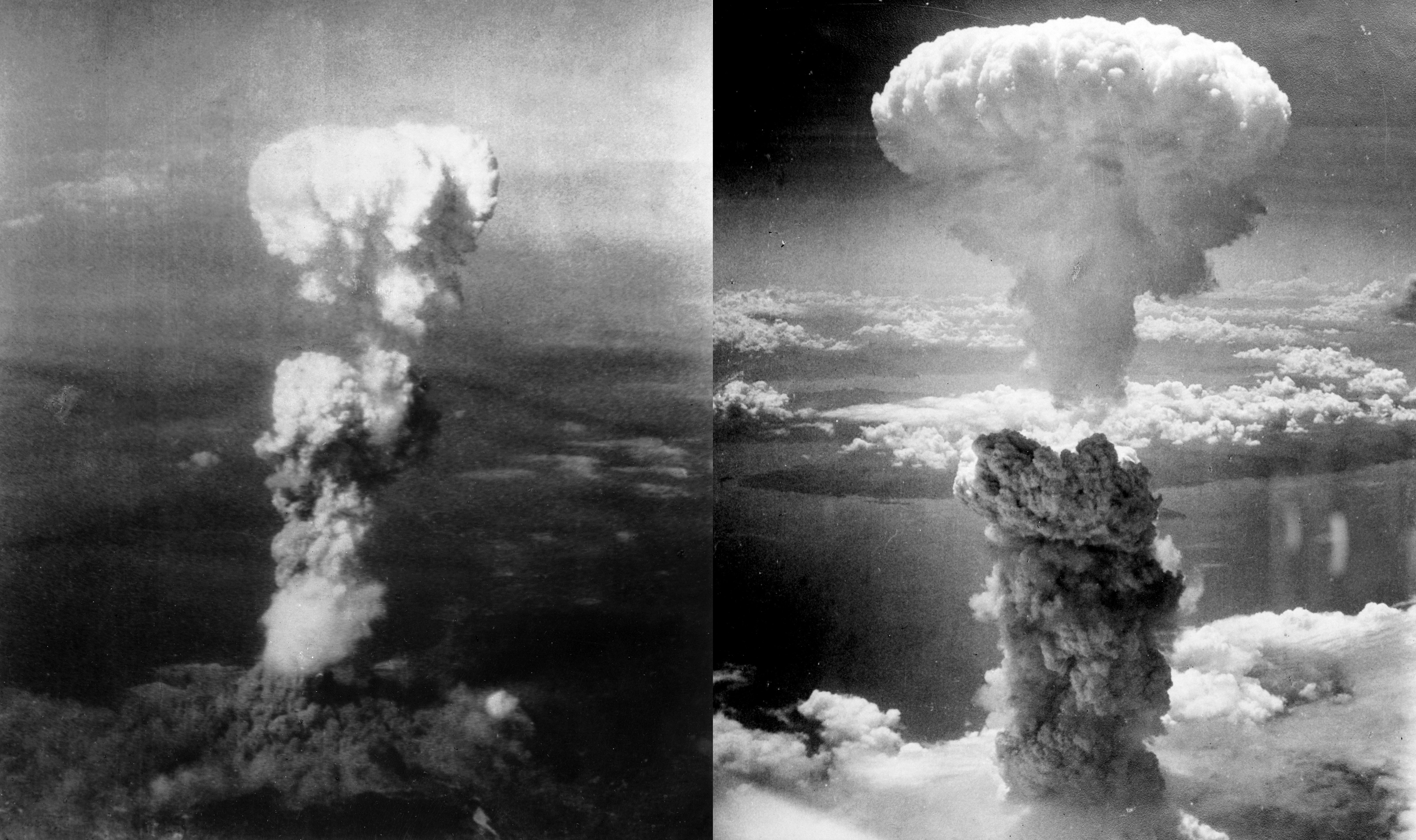

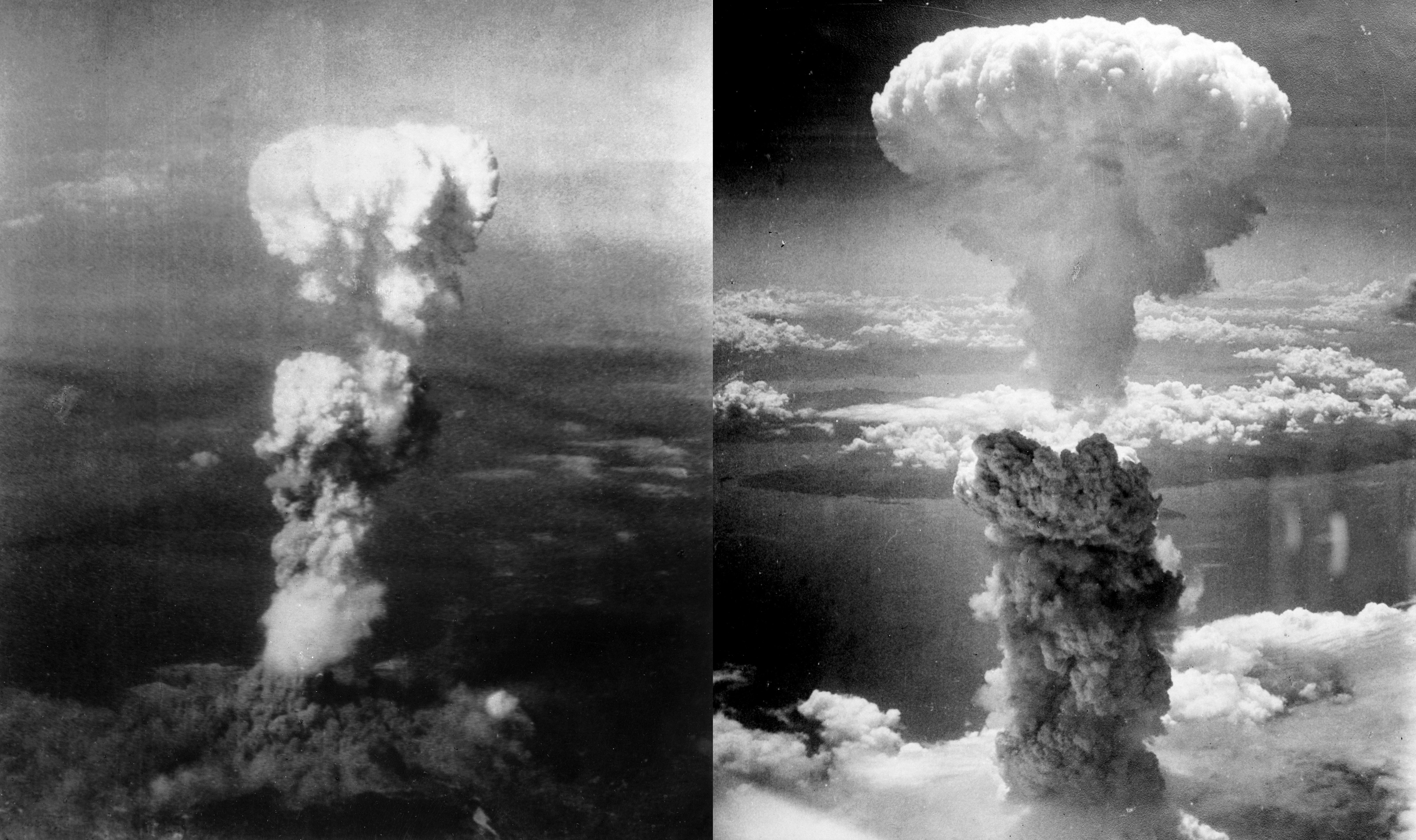

The first nuclear device ever detonated was an implosion-type bomb during the

Trinity test

Trinity was the code name of the first detonation of a nuclear weapon. It was conducted by the United States Army at 5:29 a.m. on July 16, 1945, as part of the Manhattan Project. The test was conducted in the Jornada del Muerto desert ab ...

, conducted at New Mexico's

Alamogordo Bombing and Gunnery Range

Alamogordo () is the seat of Otero County, New Mexico, United States. A city in the Tularosa Basin of the Chihuahuan Desert, it is bordered on the east by the Sacramento Mountains and to the west by Holloman Air Force Base. The population ...

on 16 July 1945. Little Boy and Fat Man bombs were used a month later in the

atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

The United States detonated two atomic bombs over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 6 and 9 August 1945, respectively. The two bombings killed between 129,000 and 226,000 people, most of whom were civilians, and remain the onl ...

, respectively, with Manhattan Project personnel serving as bomb assembly technicians and weaponeers on the attack aircraft. In the immediate postwar years, the Manhattan Project conducted weapons testing at

Bikini Atoll

Bikini Atoll ( or ; Marshallese: , , meaning "coconut place"), sometimes known as Eschscholtz Atoll between the 1800s and 1946 is a coral reef in the Marshall Islands consisting of 23 islands surrounding a central lagoon. After the Sec ...

as part of

Operation Crossroads

Operation Crossroads was a pair of nuclear weapon tests conducted by the United States at Bikini Atoll in mid-1946. They were the first nuclear weapon tests since Trinity in July 1945, and the first detonations of nuclear devices since the ...

, developed new weapons, promoted the development of the network of

national laboratories, supported medical research into

radiology

Radiology ( ) is the medical discipline that uses medical imaging to diagnose diseases and guide their treatment, within the bodies of humans and other animals. It began with radiography (which is why its name has a root referring to radiati ...

and laid the foundations for the

nuclear navy

A nuclear navy, or nuclear-powered navy, refers to the portion of a navy consisting of naval ships powered by nuclear marine propulsion. The concept was revolutionary for naval warfare when first proposed. Prior to nuclear power, submarines were ...

. It maintained control over American atomic weapons research and production until the formation of the

United States Atomic Energy Commission

The United States Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) was an agency of the United States government established after World War II by U.S. Congress to foster and control the peacetime development of atomic science and technology. President ...

in January 1947.

Origins

The

discovery of nuclear fission

Nuclear fission was discovered in December 1938 by chemists Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann and physicists Lise Meitner and Otto Robert Frisch. Fission is a nuclear reaction or radioactive decay process in which the nucleus of an atom splits ...

by German chemists

Otto Hahn

Otto Hahn (; 8 March 1879 – 28 July 1968) was a German chemist who was a pioneer in the fields of radioactivity and radiochemistry. He is referred to as the father of nuclear chemistry and father of nuclear fission. Hahn and Lise Meitner ...

and

Fritz Strassmann

Friedrich Wilhelm Strassmann (; 22 February 1902 – 22 April 1980) was a German chemist who, with Otto Hahn in December 1938, identified the element barium as a product of the bombardment of uranium with neutrons. Their observation was the key ...

in 1938, and its theoretical explanation by

Lise Meitner

Elise Meitner ( , ; 7 November 1878 – 27 October 1968) was an Austrian-Swedish physicist who was one of those responsible for the discovery of the element protactinium and nuclear fission. While working at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute on ra ...

and

Otto Frisch

Otto Robert Frisch FRS (1 October 1904 – 22 September 1979) was an Austrian-born British physicist who worked on nuclear physics. With Lise Meitner he advanced the first theoretical explanation of nuclear fission (coining the term) and first ...

, made the development of an

atomic bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions ( thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

a theoretical possibility. There were fears that a

German atomic bomb project

The Uranverein ( en, "Uranium Club") or Uranprojekt ( en, "Uranium Project") was the name given to the project in Germany to research nuclear technology, including nuclear weapons

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its ...

would develop one first, especially among scientists who were refugees from

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

and other

fascist

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy and the ...

countries. In August 1939, Hungarian-born physicists

Leo Szilard

Leo Szilard (; hu, Szilárd Leó, pronounced ; born Leó Spitz; February 11, 1898 – May 30, 1964) was a Hungarian-German-American physicist and inventor. He conceived the nuclear chain reaction in 1933, patented the idea of a nuclear ...

and

Eugene Wigner

Eugene Paul "E. P." Wigner ( hu, Wigner Jenő Pál, ; November 17, 1902 – January 1, 1995) was a Hungarian-American theoretical physicist who also contributed to mathematical physics. He received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1963 "for his con ...

drafted the

Einstein–Szilard letter, which warned of the potential development of "extremely powerful bombs of a new type". It urged the United States to take steps to acquire stockpiles of

uranium ore

Uranium ore deposits are economically recoverable concentrations of uranium within the Earth's crust. Uranium is one of the more common elements in the Earth's crust, being 40 times more common than silver and 500 times more common than gold. It ...

and accelerate the research of

Enrico Fermi

Enrico Fermi (; 29 September 1901 – 28 November 1954) was an Italian (later naturalized American) physicist and the creator of the world's first nuclear reactor, the Chicago Pile-1. He has been called the "architect of the nuclear age" an ...

and others into

nuclear chain reaction

In nuclear physics, a nuclear chain reaction occurs when one single nuclear reaction causes an average of one or more subsequent nuclear reactions, thus leading to the possibility of a self-propagating series of these reactions. The specific nu ...

s. They had it signed by

Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein ( ; ; 14 March 1879 – 18 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist, widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest and most influential physicists of all time. Einstein is best known for developing the theor ...

and delivered to President

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

. Roosevelt called on

Lyman Briggs

Lyman James Briggs (May 7, 1874 – March 25, 1963) was an American engineer, physicist and administrator. He was a director of the National Bureau of Standards during the Great Depression and chairman of the Uranium Committee before America en ...

of the

National Bureau of Standards

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) is an agency of the United States Department of Commerce whose mission is to promote American innovation and industrial competitiveness. NIST's activities are organized into physical sci ...

to head the

Advisory Committee on Uranium

The S-1 Executive Committee laid the groundwork for the Manhattan Project by initiating and coordinating the early research efforts in the United States, and liaising with the Tube Alloys Project in Britain.

In the wake of the discovery of nucle ...

to investigate the issues raised by the letter. Briggs held a meeting on 21 October 1939, which was attended by Szilárd, Wigner and

Edward Teller

Edward Teller ( hu, Teller Ede; January 15, 1908 – September 9, 2003) was a Hungarian-American theoretical physicist who is known colloquially as "the father of the hydrogen bomb" (see the Teller–Ulam design), although he did not care f ...

. The committee reported back to Roosevelt in November that uranium "would provide a possible source of bombs with a destructiveness vastly greater than anything now known."

In February 1940, the

U.S. Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage o ...

awarded

Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manha ...

$6,000 in funding, most of which

Enrico Fermi

Enrico Fermi (; 29 September 1901 – 28 November 1954) was an Italian (later naturalized American) physicist and the creator of the world's first nuclear reactor, the Chicago Pile-1. He has been called the "architect of the nuclear age" an ...

and Szilard spent on purchasing

graphite

Graphite () is a crystalline form of the element carbon. It consists of stacked layers of graphene. Graphite occurs naturally and is the most stable form of carbon under standard conditions. Synthetic and natural graphite are consumed on la ...

. A team of Columbia professors including Fermi, Szilard,

Eugene T. Booth

Eugene Theodore Booth, Jr. (28 September 1912 – 6 March 2004) was an American nuclear physicist. He was a member of the historic Columbia University team which made the first demonstration of nuclear fission in the United States. During the ...

and

John Dunning created the first nuclear fission reaction in the Americas, verifying the work of Hahn and Strassmann. The same team subsequently built a series of prototype

nuclear reactor

A nuclear reactor is a device used to initiate and control a fission nuclear chain reaction or nuclear fusion reactions. Nuclear reactors are used at nuclear power plants for electricity generation and in nuclear marine propulsion. Heat from nu ...

s (or "piles" as Fermi called them) in

Pupin Hall

Pupin Physics Laboratories , also known as Pupin Hall, is home to the physics and astronomy departments of Columbia University in New York City. The building is located on the south side of 120th Street, just east of Broadway. In 1965, Pupin was ...

at Columbia, but were not yet able to achieve a chain reaction. The Advisory Committee on Uranium became the

National Defense Research Committee

The National Defense Research Committee (NDRC) was an organization created "to coordinate, supervise, and conduct scientific research on the problems underlying the development, production, and use of mechanisms and devices of warfare" in the Un ...

(NDRC) on Uranium when that organization was formed on 27 June 1940. Briggs proposed spending $167,000 on research into uranium, particularly the

uranium-235

Uranium-235 (235U or U-235) is an Isotopes of uranium, isotope of uranium making up about 0.72% of natural uranium. Unlike the predominant isotope uranium-238, it is fissile, i.e., it can sustain a nuclear chain reaction. It is the only fissile ...

isotope, and

plutonium

Plutonium is a radioactive chemical element with the symbol Pu and atomic number 94. It is an actinide metal of silvery-gray appearance that tarnishes when exposed to air, and forms a dull coating when oxidized. The element normally exhib ...

, which was discovered in 1940 at the

University of California

The University of California (UC) is a public land-grant research university system in the U.S. state of California. The system is composed of the campuses at Berkeley, Davis, Irvine, Los Angeles, Merced, Riverside, San Diego, San Fran ...

.

On 28 June 1941, Roosevelt signed Executive Order 8807, which created the

Office of Scientific Research and Development

The Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD) was an agency of the United States federal government created to coordinate scientific research for military purposes during World War II. Arrangements were made for its creation during May ...

(OSRD), with

Vannevar Bush

Vannevar Bush ( ; March 11, 1890 – June 28, 1974) was an American engineer, inventor and science administrator, who during World War II headed the U.S. Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD), through which almost all wartim ...

as its director. The office was empowered to engage in large engineering projects in addition to research.

[.] The NDRC Committee on Uranium became the S-1 Section of the OSRD; the word "uranium" was dropped for security reasons.

In Britain, Frisch and

Rudolf Peierls

Sir Rudolf Ernst Peierls, (; ; 5 June 1907 – 19 September 1995) was a German-born British physicist who played a major role in Tube Alloys, Britain's nuclear weapon programme, as well as the subsequent Manhattan Project, the combined Allied ...

at the

University of Birmingham

The University of Birmingham (informally Birmingham University) is a Public university, public research university located in Edgbaston, Birmingham, United Kingdom. It received its royal charter in 1900 as a successor to Queen's College, Birmingha ...

had made a breakthrough investigating the

critical mass

In nuclear engineering, a critical mass is the smallest amount of fissile material needed for a sustained nuclear chain reaction. The critical mass of a fissionable material depends upon its nuclear properties (specifically, its nuclear fis ...

of uranium-235 in June 1939. Their calculations indicated that it was within an

order of magnitude

An order of magnitude is an approximation of the logarithm of a value relative to some contextually understood reference value, usually 10, interpreted as the base of the logarithm and the representative of values of magnitude one. Logarithmic di ...

of , which was small enough to be carried by a bomber of the day.

[.] Their March 1940

Frisch–Peierls memorandum

The Frisch–Peierls memorandum was the first technical exposition of a practical nuclear weapon. It was written by expatriate German-Jewish physicists Otto Frisch and Rudolf Peierls in March 1940 while they were both working for Mark Oliphant at ...

initiated the British atomic bomb project and its

MAUD Committee

The MAUD Committee was a British scientific working group formed during the Second World War. It was established to perform the research required to determine if an atomic bomb was feasible. The name MAUD came from a strange line in a telegram fro ...

, which unanimously recommended pursuing the development of an atomic bomb.

In July 1940, Britain had offered to give the United States access to its scientific research, and the

Tizard Mission

The Tizard Mission, officially the British Technical and Scientific Mission, was a British delegation that visited the United States during WWII to obtain the industrial resources to exploit the military potential of the research and development ( ...

's

John Cockcroft

Sir John Douglas Cockcroft, (27 May 1897 – 18 September 1967) was a British physicist who shared with Ernest Walton the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1951 for splitting the atomic nucleus, and was instrumental in the development of nuclea ...

briefed American scientists on British developments. He discovered that the American project was smaller than the British, and not as far advanced.

As part of the scientific exchange, the MAUD Committee's findings were conveyed to the United States. One of its members, the Australian physicist

Mark Oliphant

Sir Marcus Laurence Elwin Oliphant, (8 October 1901 – 14 July 2000) was an Australian physicist and humanitarian who played an important role in the first experimental demonstration of nuclear fusion and in the development of nuclear weapon ...

, flew to the United States in late August 1941 and discovered that data provided by the MAUD Committee had not reached key American physicists. Oliphant then set out to find out why the committee's findings were apparently being ignored. He met with the Uranium Committee and visited

Berkeley, California

Berkeley ( ) is a city on the eastern shore of San Francisco Bay in northern Alameda County, California, United States. It is named after the 18th-century Irish bishop and philosopher George Berkeley. It borders the cities of Oakland and Emer ...

, where he spoke persuasively to

Ernest O. Lawrence

Ernest Orlando Lawrence (August 8, 1901 – August 27, 1958) was an American nuclear physicist and winner of the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1939 for his invention of the cyclotron. He is known for his work on uranium-isotope separation fo ...

. Lawrence was sufficiently impressed to commence his own research into uranium. He in turn spoke to

James B. Conant

James Bryant Conant (March 26, 1893 – February 11, 1978) was an American chemist, a transformative President of Harvard University, and the first United States Ambassador to West Germany, U.S. Ambassador to West Germany. Conant obtained a ...

,

Arthur H. Compton

Arthur Holly Compton (September 10, 1892 – March 15, 1962) was an American physicist who won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1927 for his 1923 discovery of the Compton effect, which demonstrated the particle nature of electromagnetic r ...

and

George B. Pegram. Oliphant's mission was therefore a success; key American physicists were now aware of the potential power of an atomic bomb.

On 9 October 1941, President Roosevelt approved the atomic program after he convened a meeting with Vannevar Bush and Vice President

Henry A. Wallace

Henry Agard Wallace (October 7, 1888 – November 18, 1965) was an American politician, journalist, farmer, and businessman who served as the 33rd vice president of the United States, the 11th U.S. Secretary of Agriculture, and the 10th U.S. ...

. To control the program, he created a Top Policy Group consisting of himself—although he never attended a meeting—Wallace, Bush, Conant,

Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

Henry L. Stimson

Henry Lewis Stimson (September 21, 1867 – October 20, 1950) was an American statesman, lawyer, and Republican Party politician. Over his long career, he emerged as a leading figure in U.S. foreign policy by serving in both Republican and De ...

, and the

Chief of Staff of the Army,

General

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". O ...

George C. Marshall

George Catlett Marshall Jr. (December 31, 1880 – October 16, 1959) was an American army officer and statesman. He rose through the United States Army to become Chief of Staff of the US Army under Presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry S ...

. Roosevelt chose the Army to run the project rather than the Navy, because the Army had more experience with management of large-scale construction projects. He also agreed to coordinate the effort with that of the British, and on 11 October he sent a message to Prime Minister

Winston Churchill, suggesting that they correspond on atomic matters.

[.]

Feasibility

Proposals

The S-1 Committee held its meeting on 18 December 1941 "pervaded by an atmosphere of enthusiasm and urgency" in the wake of the

attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service upon the United States against the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Territory of Hawa ...

and the subsequent

United States declaration of war upon Japan

On December 8, 1941, the United States Congress declared war () on the Empire of Japan in response to that country's surprise attack on Pearl Harbor and declaration of war the prior day. The Joint Resolution Declaring that a state of war exis ...

and

then on Germany. Work was proceeding on three different techniques for

isotope separation

Isotope separation is the process of concentrating specific isotopes of a chemical element by removing other isotopes. The use of the nuclides produced is varied. The largest variety is used in research (e.g. in chemistry where atoms of "marker" ...

to separate uranium-235 from the more abundant

uranium-238

Uranium-238 (238U or U-238) is the most common isotope of uranium found in nature, with a relative abundance of 99%. Unlike uranium-235, it is non-fissile, which means it cannot sustain a chain reaction in a thermal-neutron reactor. However ...

. Lawrence and his team at the

University of California

The University of California (UC) is a public land-grant research university system in the U.S. state of California. The system is composed of the campuses at Berkeley, Davis, Irvine, Los Angeles, Merced, Riverside, San Diego, San Fran ...

investigated

electromagnetic separation

Isotope separation is the process of concentrating specific isotopes of a chemical element by removing other isotopes. The use of the nuclides produced is varied. The largest variety is used in research (e.g. in chemistry where atoms of "marker" ...

, while

Eger Murphree and

Jesse Wakefield Beams's team looked into

gaseous diffusion

Gaseous diffusion is a technology used to produce enriched uranium by forcing gaseous uranium hexafluoride (UF6) through semipermeable membranes. This produces a slight separation between the molecules containing uranium-235 (235U) and uranium-2 ...

at

Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manha ...

, and

Philip Abelson

Philip, also Phillip, is a male given name, derived from the Greek (''Philippos'', lit. "horse-loving" or "fond of horses"), from a compound of (''philos'', "dear", "loved", "loving") and (''hippos'', "horse"). Prominent Philips who popularize ...

directed research into

thermal diffusion Thermal diffusion may refer to:

* A thermal force on a gas due to a temperature gradient, also called ''thermal diffusion'' or Thermal transpiration.

** It is used to drive a gas pump with no moving parts called a Knudsen pump.

** It is the currentl ...

at the

Carnegie Institution of Washington

The Carnegie Institution of Washington (the organization's legal name), known also for public purposes as the Carnegie Institution for Science (CIS), is an organization in the United States established to fund and perform scientific research. Th ...

and later the

Naval Research Laboratory

The United States Naval Research Laboratory (NRL) is the corporate research laboratory for the United States Navy and the United States Marine Corps. It was founded in 1923 and conducts basic scientific research, applied research, technological ...

.

Murphree was also the head of an unsuccessful separation project using

gas centrifuge

A gas centrifuge is a device that performs isotope separation of gases. A centrifuge relies on the principles of centrifugal force accelerating molecules so that particles of different masses are physically separated in a gradient along the radi ...

s.

Meanwhile, there were two lines of research into

nuclear reactor technology

A nuclear reactor is a device used to initiate and control a fission nuclear chain reaction or nuclear fusion reactions. Nuclear reactors are used at nuclear power plants for electricity generation and in nuclear marine propulsion. Heat from nu ...

, with

Harold Urey

Harold Clayton Urey ( ; April 29, 1893 – January 5, 1981) was an American physical chemist whose pioneering work on isotopes earned him the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1934 for the discovery of deuterium. He played a significant role in the ...

continuing research into

heavy water at Columbia, while Arthur Compton brought the scientists working under his supervision from Columbia, California and

Princeton University

Princeton University is a private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and one of the n ...

to join his team at the

University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, U of C, or UChi) is a private university, private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Its main campus is located in Chicago's Hyde Park, Chicago, Hyde Park neighborhood. The University of Chic ...

, where he organized the

Metallurgical Laboratory

The Metallurgical Laboratory (or Met Lab) was a scientific laboratory at the University of Chicago that was established in February 1942 to study and use the newly discovered chemical element plutonium. It researched plutonium's chemistry and m ...

in early 1942 to study plutonium and reactors using

graphite

Graphite () is a crystalline form of the element carbon. It consists of stacked layers of graphene. Graphite occurs naturally and is the most stable form of carbon under standard conditions. Synthetic and natural graphite are consumed on la ...

as a

neutron moderator. Briggs, Compton, Lawrence, Murphree, and Urey met on 23 May 1942, to finalize the S-1 Committee recommendations, which called for all five technologies to be pursued. This was approved by Bush, Conant, and

Brigadier General

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed t ...

Wilhelm D. Styer, the chief of staff of

Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

Brehon B. Somervell

Brehon Burke Somervell (9 May 1892 – 13 February 1955) was a general in the United States Army and Commanding General of the Army Service Forces in World War II. As such he was responsible for the U.S. Army's logistics. Following his death, ' ...

's

Services of Supply

The Services of Supply or "SOS" branch of the Army of the USA was created on 28 February 1942 by Executive Order Number 9082 "Reorganizing the Army and the War Department" and War Department Circular No. 59, dated 2 March 1942. Services of Supp ...

, who had been designated the Army's representative on nuclear matters.

Bush and Conant then took the recommendation to the Top Policy Group with a budget proposal for $54 million for construction by the

, $31 million for research and development by OSRD and $5 million for contingencies in fiscal year 1943. The Top Policy Group in turn sent it on 17 June 1942, to the President, who approved it by writing "OK FDR" on the document.

[.]

Bomb design concepts

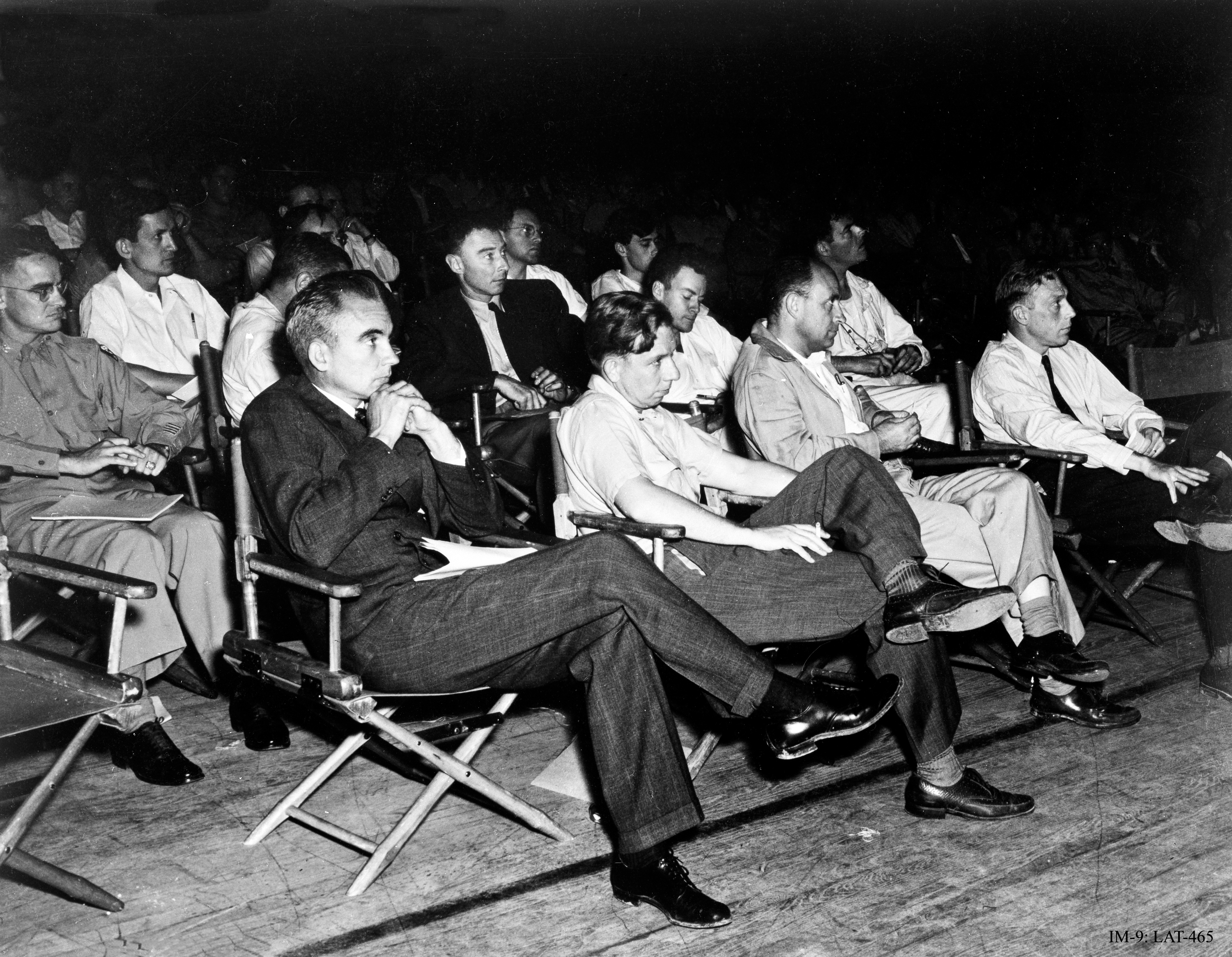

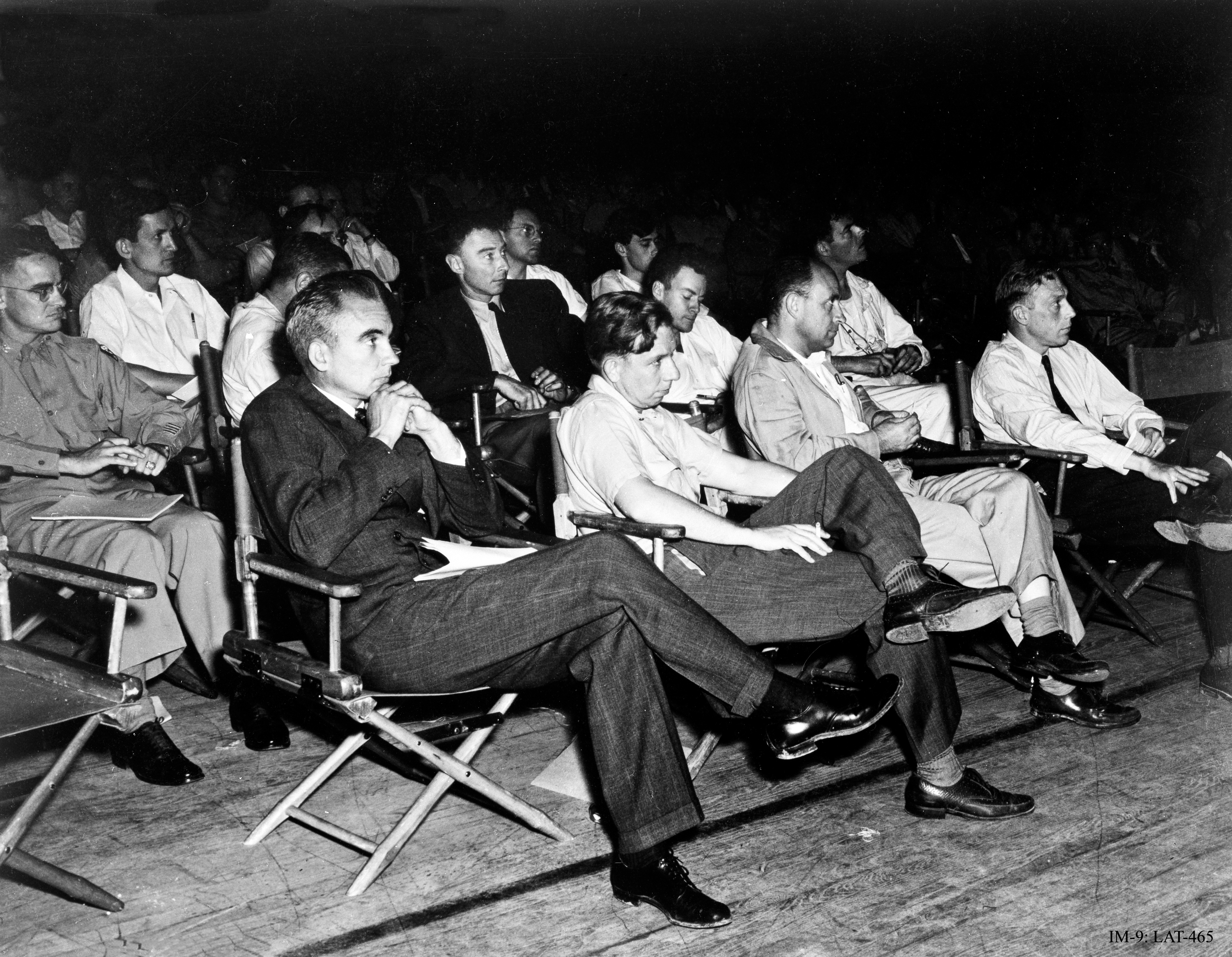

Compton asked theoretical physicist

J. Robert Oppenheimer

J. Robert Oppenheimer (; April 22, 1904 – February 18, 1967) was an American theoretical physicist. A professor of physics at the University of California, Berkeley, Oppenheimer was the wartime head of the Los Alamos Laboratory and is often ...

of the University of California to take over research into

fast neutron calculations—the key to calculations of critical mass and weapon detonation—from

Gregory Breit

Gregory Breit (russian: Григорий Альфредович Брейт-Шнайдер, ''Grigory Alfredovich Breit-Shneider''; July 14, 1899, Mykolaiv, Kherson Governorate – September 13, 1981, Salem, Oregon) was a Russian-born Jewish ...

, who had quit on 18 May 1942 because of concerns over lax operational security.

John H. Manley, a physicist at the Metallurgical Laboratory, was assigned to assist Oppenheimer by contacting and coordinating experimental physics groups scattered across the country. Oppenheimer and

Robert Serber

Robert Serber (March 14, 1909 – June 1, 1997) was an American physicist who participated in the Manhattan Project. Serber's lectures explaining the basic principles and goals of the project were printed and supplied to all incoming scientific st ...

of the

University of Illinois

The University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign (U of I, Illinois, University of Illinois, or UIUC) is a public land-grant research university in Illinois in the twin cities of Champaign and Urbana. It is the flagship institution of the Unive ...

examined the problems of

neutron

The neutron is a subatomic particle, symbol or , which has a neutral (not positive or negative) charge, and a mass slightly greater than that of a proton. Protons and neutrons constitute the nuclei of atoms. Since protons and neutrons behav ...

diffusion—how neutrons moved in a nuclear chain reaction—and

hydrodynamics—how the explosion produced by a chain reaction might behave. To review this work and the general theory of fission reactions, Oppenheimer and

Fermi

Enrico Fermi (; 29 September 1901 – 28 November 1954) was an Italian (later naturalized American) physicist and the creator of the world's first nuclear reactor, the Chicago Pile-1. He has been called the "architect of the nuclear age" and ...

convened meetings at the University of Chicago in June and at the University of California in July 1942 with theoretical physicists

Hans Bethe

Hans Albrecht Bethe (; July 2, 1906 – March 6, 2005) was a German-American theoretical physicist who made major contributions to nuclear physics, astrophysics, quantum electrodynamics, and solid-state physics, and who won the 1967 Nobel Prize ...

,

John Van Vleck

John Hasbrouck Van Vleck (March 13, 1899 – October 27, 1980) was an American physicist and mathematician. He was co-awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1977, for his contributions to the understanding of the behavior of electronic magnetism in ...

, Edward Teller,

Emil Konopinski, Robert Serber,

Stan Frankel

Stanley Phillips Frankel (1919 – May, 1978) was an American computer scientist. He worked in the Manhattan Project and developed various computers as a consultant.

Early life

He was born in Los Angeles, attended graduate school at the Univers ...

, and

Eldred C. (Carlyle) Nelson, the latter three former students of Oppenheimer, and

experimental physicist

Experimental physics is the category of disciplines and sub-disciplines in the field of physics that are concerned with the observation of physical phenomena and experiments. Methods vary from discipline to discipline, from simple experiments and o ...

s

Emilio Segrè

Emilio Gino Segrè (1 February 1905 – 22 April 1989) was an Italian-American physicist and Nobel laureate, who discovered the elements technetium and astatine, and the antiproton, a subatomic antiparticle, for which he was awarded the N ...

,

Felix Bloch

Felix Bloch (23 October 1905 – 10 September 1983) was a Swiss- American physicist and Nobel physics laureate who worked mainly in the U.S. He and Edward Mills Purcell were awarded the 1952 Nobel Prize for Physics for "their development of n ...

,

Franco Rasetti

Franco Dino Rasetti (August 10, 1901 – December 5, 2001) was an Italian (later naturalized American) physicist, paleontologist and botanist. Together with Enrico Fermi, he discovered key processes leading to nuclear fission. Rasetti refused ...

,

John Henry Manley

John Henry Manley (July 21, 1907 – June 11, 1990) was an American physicist who worked with J. Robert Oppenheimer at the University of California, Berkeley before becoming a group leader during the Manhattan Project.

Biography

He was born in ...

, and

Edwin McMillan

Edwin Mattison McMillan (September 18, 1907 – September 7, 1991) was an American physicist credited with being the first-ever to produce a transuranium element, neptunium. For this, he shared the 1951 Nobel Prize in Chemistry with Glenn Seabo ...

. They tentatively confirmed that a fission bomb was theoretically possible.

There were still many unknown factors. The properties of pure uranium-235 were relatively unknown, as were those of plutonium, an element that had only been discovered in February 1941 by

Glenn Seaborg

Glenn Theodore Seaborg (; April 19, 1912February 25, 1999) was an American chemist whose involvement in the synthesis, discovery and investigation of ten transuranium elements earned him a share of the 1951 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. His work in ...

and his team. The scientists at the (July 1942) Berkeley conference envisioned creating plutonium in nuclear reactors where uranium-238 atoms absorbed neutrons that had been emitted from fissioning uranium-235 atoms. At this point no reactor had been built, and only tiny quantities of plutonium were available from

cyclotron

A cyclotron is a type of particle accelerator invented by Ernest O. Lawrence in 1929–1930 at the University of California, Berkeley, and patented in 1932. Lawrence, Ernest O. ''Method and apparatus for the acceleration of ions'', filed: J ...

s at institutions such as

Washington University in St. Louis

Washington University in St. Louis (WashU or WUSTL) is a private research university with its main campus in St. Louis County, and Clayton, Missouri. Founded in 1853, the university is named after George Washington. Washington University i ...

. Even by December 1943, only two milligrams had been produced. There were many ways of arranging the fissile material into a critical mass. The simplest was shooting a "cylindrical plug" into a sphere of "active material" with a "tamper"—dense material that would focus neutrons inward and keep the reacting mass together to increase its efficiency. They also explored designs involving

spheroid

A spheroid, also known as an ellipsoid of revolution or rotational ellipsoid, is a quadric surface obtained by rotating an ellipse about one of its principal axes; in other words, an ellipsoid with two equal semi-diameters. A spheroid has ...

s, a primitive form of "

implosion" suggested by

Richard C. Tolman

Richard Chace Tolman (March 4, 1881 – September 5, 1948) was an American mathematical physicist and physical chemist who made many contributions to statistical mechanics. He also made important contributions to theoretical cosmology in ...

, and the possibility of

autocatalytic methods, which would increase the efficiency of the bomb as it exploded.

Considering the idea of the fission bomb theoretically settled—at least until more experimental data was available—the 1942 Berkeley conference then turned in a different direction. Edward Teller pushed for discussion of a more powerful bomb: the "super", now usually referred to as a "

hydrogen bomb", which would use the explosive force of a detonating fission bomb to ignite a

nuclear fusion

Nuclear fusion is a reaction in which two or more atomic nuclei are combined to form one or more different atomic nuclei and subatomic particles (neutrons or protons). The difference in mass between the reactants and products is manifest ...

reaction in

deuterium

Deuterium (or hydrogen-2, symbol or deuterium, also known as heavy hydrogen) is one of two Stable isotope ratio, stable isotopes of hydrogen (the other being Hydrogen atom, protium, or hydrogen-1). The atomic nucleus, nucleus of a deuterium ato ...

and

tritium

Tritium ( or , ) or hydrogen-3 (symbol T or H) is a rare and radioactive isotope of hydrogen with half-life about 12 years. The nucleus of tritium (t, sometimes called a ''triton'') contains one proton and two neutrons, whereas the nucleus ...

. Teller proposed scheme after scheme, but Bethe refused each one. The fusion idea was put aside to concentrate on producing fission bombs. Teller also raised the speculative possibility that an atomic bomb might "ignite" the atmosphere because of a hypothetical fusion reaction of nitrogen nuclei. Bethe calculated that it could not happen, and a report co-authored by Teller showed that "no self-propagating chain of nuclear reactions is likely to be started." In Serber's account, Oppenheimer mentioned the possibility of this scenario to

Arthur Compton

Arthur Holly Compton (September 10, 1892 – March 15, 1962) was an American physicist who won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1927 for his 1923 discovery of the Compton effect, which demonstrated the particle nature of electromagnetic radia ...

, who "didn't have enough sense to shut up about it. It somehow got into a document that went to Washington" and was "never laid to rest".

Organization

Manhattan District

The

Chief of Engineers

The Chief of Engineers is a principal United States Army staff officer at The Pentagon. The Chief advises the Army on engineering matters, and serves as the Army's topographer and proponent for real estate and other related engineering program ...

, Major General

Eugene Reybold

Eugene Reybold (February 13, 1884 – November 21, 1961) was distinguished as the World War II Chief of Engineers who directed the largest United States Army Corps of Engineers in the nation's history.

Reybold was born in Delaware City, Delaware ...

, selected Colonel

James C. Marshall to head the Army's part of the project in June 1942. Marshall created a liaison office in Washington, D.C., but established his temporary headquarters on the 18th floor of

270 Broadway

Tower 270 (also known as 270 Broadway, Arthur Levitt State Office Building, 80 Chambers Street, and 86 Chambers Street) is a 28-story mixed use building in the Civic Center and Tribeca neighborhoods of Manhattan, New York City. Completed in 1930 ...

in New York, where he could draw on administrative support from the Corps of Engineers'

North Atlantic Division. It was close to the Manhattan office of

Stone & Webster

Stone & Webster was an American engineering services company based in Stoughton, Massachusetts. It was founded as an electrical testing lab and consulting firm by electrical engineers Charles A. Stone and Edwin S. Webster in 1889. In the early ...

, the principal project contractor, and to Columbia University. He had permission to draw on his former command, the Syracuse District, for staff, and he started with

Lieutenant Colonel Kenneth Nichols

Major General Kenneth David Nichols CBE (13 November 1907 – 21 February 2000), also known by Nick, was an officer in the United States Army, and a civil engineer who worked on the secret Manhattan Project, which developed the atomic bomb du ...

, who became his deputy.

[.]

Because most of his task involved construction, Marshall worked in cooperation with the head of the Corps of Engineers Construction Division, Major General

Thomas M. Robbins, and his deputy, Colonel

Leslie Groves

Lieutenant General Leslie Richard Groves Jr. (17 August 1896 – 13 July 1970) was a United States Army Corps of Engineers officer who oversaw the construction of the Pentagon and directed the Manhattan Project, a top secret research project ...

. Reybold, Somervell, and Styer decided to call the project "Development of Substitute Materials", but Groves felt that this would draw attention. Since engineer districts normally carried the name of the city where they were located, Marshall and Groves agreed to name the Army's component of the project the Manhattan District. This became official on 13 August when Reybold issued the order creating the new district. Informally, it was known as the Manhattan Engineer District, or MED. Unlike other districts, it had no geographic boundaries, and Marshall had the authority of a division engineer. Development of Substitute Materials remained as the official codename of the project as a whole, but was supplanted over time by "Manhattan".

Marshall later conceded that, "I had never heard of atomic fission but I did know that you could not build much of a plant, much less four of them for $90 million." A single

TNT

Trinitrotoluene (), more commonly known as TNT, more specifically 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene, and by its preferred IUPAC name 2-methyl-1,3,5-trinitrobenzene, is a chemical compound with the formula C6H2(NO2)3CH3. TNT is occasionally used as a reage ...

plant that Nichols had recently built in Pennsylvania had cost $128 million. Nor were they impressed with estimates to the nearest order of magnitude, which Groves compared with telling a caterer to prepare for between ten and a thousand guests. A survey team from Stone & Webster had already scouted a site for the production plants. The

War Production Board

The War Production Board (WPB) was an agency of the United States government that supervised war production during World War II. President Franklin D. Roosevelt established it in January 1942, with Executive Order 9024. The WPB replaced the S ...

recommended sites around

Knoxville, Tennessee

Knoxville is a city in and the county seat of Knox County in the U.S. state of Tennessee. As of the 2020 United States census, Knoxville's population was 190,740, making it the largest city in the East Tennessee Grand Division and the state ...

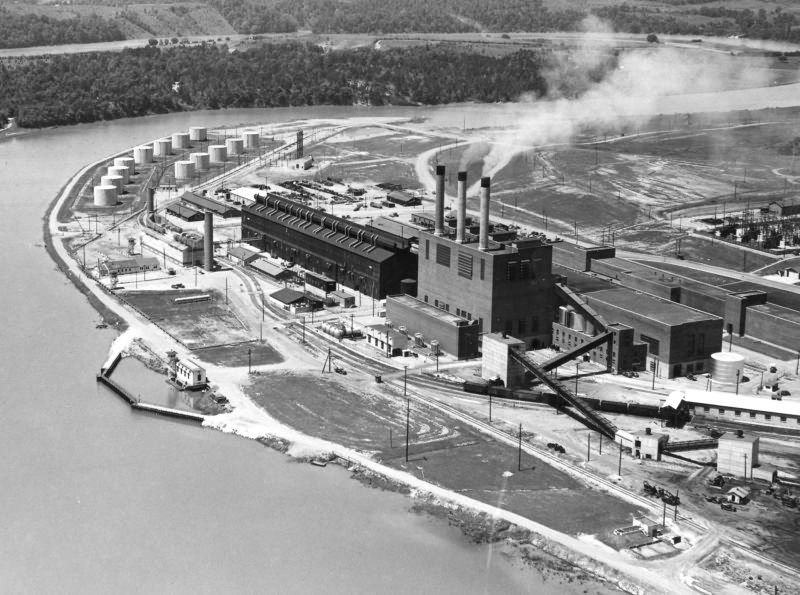

, an isolated area where the

Tennessee Valley Authority

The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) is a federally owned electric utility corporation in the United States. TVA's service area covers all of Tennessee, portions of Alabama, Mississippi, and Kentucky, and small areas of Georgia, North Carolina ...

could supply ample electric power and the rivers could provide cooling water for the reactors. After examining several sites, the survey team selected one near

Elza, Tennessee

Elza was a community in Anderson County, Tennessee, that existed before 1942, when the area was acquired for the Manhattan Project. Its site is now part of the city of Oak Ridge, Tennessee.

History

Elza formed around a flagstop on the Louisvil ...

. Conant advised that it be acquired at once and Styer agreed but Marshall temporized, awaiting the results of Conant's reactor experiments before taking action. Of the prospective processes, only Lawrence's electromagnetic separation appeared sufficiently advanced for construction to commence.

Marshall and Nichols began assembling the resources they would need. The first step was to obtain a high priority rating for the project. The top ratings were AA-1 through AA-4 in descending order, although there was also a special AAA rating reserved for emergencies. Ratings AA-1 and AA-2 were for essential weapons and equipment, so Colonel

Lucius D. Clay

General Lucius Dubignon Clay (April 23, 1898 – April 16, 1978) was a senior officer of the United States Army who was known for his administration of occupied Germany after World War II. He served as the deputy to General of the Army Dwight ...

, the deputy chief of staff at Services and Supply for requirements and resources, felt that the highest rating he could assign was AA-3, although he was willing to provide a AAA rating on request for critical materials if the need arose. Nichols and Marshall were disappointed; AA-3 was the same priority as Nichols' TNT plant in Pennsylvania.

[.]

Military Policy Committee

Vannevar Bush became dissatisfied with Colonel Marshall's failure to get the project moving forward expeditiously, specifically the failure to acquire the Tennessee site, the low priority allocated to the project by the Army and the location of his headquarters in New York City. Bush felt that more aggressive leadership was required, and spoke to

Harvey Bundy

Harvey Hollister Bundy Sr. (March 30, 1888 – October 7, 1963) was an American attorney who served as a special assistant to the Secretary of War during World War II. He was the father of William Bundy and McGeorge Bundy, who both served at high ...

and Generals Marshall, Somervell, and Styer about his concerns. He wanted the project placed under a senior policy committee, with a prestigious officer, preferably Styer, as overall director.

Somervell and Styer selected Groves for the post, informing him on 17 September of this decision, and that General Marshall ordered that he be promoted to brigadier general,

[.] as it was felt that the title "general" would hold more sway with the academic scientists working on the Manhattan Project.

[.] Groves' orders placed him directly under Somervell rather than Reybold, with Colonel Marshall now answerable to Groves. Groves established his headquarters in Washington, D.C., on the fifth floor of the

New War Department Building, where Colonel Marshall had his liaison office. He assumed command of the Manhattan Project on 23 September 1942. Later that day, he attended a meeting called by Stimson, which established a Military Policy Committee, responsible to the Top Policy Group, consisting of Bush (with Conant as an alternate), Styer and

Rear Admiral

Rear admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, equivalent to a major general and air vice marshal and above that of a commodore and captain, but below that of a vice admiral. It is regarded as a two star " admiral" rank. It is often rega ...

William R. Purnell

Rear Admiral (United States), Rear Admiral William Reynolds Purnell (6 September 1886 – 3 March 1955) was an officer in the United States Navy who served in World War I and World War II. A 1908 graduate of the United States Naval Academy, he c ...

.

Tolman and Conant were later appointed as Groves' scientific advisers.

On 19 September, Groves went to

Donald Nelson, the chairman of the War Production Board, and asked for broad authority to issue a AAA rating whenever it was required. Nelson initially balked but quickly caved in when Groves threatened to go to the President. Groves promised not to use the AAA rating unless it was necessary. It soon transpired that for the routine requirements of the project the AAA rating was too high but the AA-3 rating was too low. After a long campaign, Groves finally received AA-1 authority on 1 July 1944. According to Groves, "In Washington you became aware of the importance of top priority. Most everything proposed in the Roosevelt administration would have top priority. That would last for about a week or two and then something else would get top priority".

One of Groves' early problems was to find a director for

Project Y

The Los Alamos Laboratory, also known as Project Y, was a secret laboratory established by the Manhattan Project and operated by the University of California during World War II. Its mission was to design and build the first atomic bombs. Rob ...

, the group that would design and build the bomb. The obvious choice was one of the three laboratory heads, Urey, Lawrence, or Compton, but they could not be spared. Compton recommended Oppenheimer, who was already intimately familiar with the bomb design concepts. However, Oppenheimer had little administrative experience, and, unlike Urey, Lawrence, and Compton, had not won a Nobel Prize, which many scientists felt that the head of such an important laboratory should have. There were also concerns about Oppenheimer's security status, as many of his associates were

communists

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a ...

, including his wife,

Kitty (Katherine Oppenheimer); his girlfriend,

Jean Tatlock

Jean Frances Tatlock (February 21, 1914 – January 4, 1944) was an American psychiatrist and physician. She was a member of the Communist Party of the United States of America and was a reporter and writer for the party's publication ''Western ...

; and his brother,

Frank Oppenheimer

Frank Friedman Oppenheimer (August 14, 1912 – February 3, 1985) was an American particle physicist, cattle rancher, professor of physics at the University of Colorado, and the founder of the Exploratorium in San Francisco.

A younger brother ...

. A long conversation on a train in October 1942 convinced Groves and Nichols that Oppenheimer thoroughly understood the issues involved in setting up a laboratory in a remote area and should be appointed as its director. Groves personally waived the security requirements and issued Oppenheimer a clearance on 20 July 1943.

Collaboration with the United Kingdom

The British and Americans exchanged nuclear information but did not initially combine their efforts. Britain rebuffed attempts by Bush and Conant in 1941 to strengthen cooperation with its own project, codenamed

Tube Alloys

Tube Alloys was the research and development programme authorised by the United Kingdom, with participation from Canada, to develop nuclear weapons during the Second World War. Starting before the Manhattan Project in the United States, the Bri ...

, because it was reluctant to share its technological lead and help the United States develop its own atomic bomb.

[.] An American scientist who brought a personal letter from Roosevelt to Churchill offering to pay for all research and development in an Anglo-American project was poorly treated, and Churchill did not reply to the letter. The United States as a result decided as early as April 1942 that if its offer was rejected, they should proceed alone.

The British, who had made significant contributions early in the war, did not have the resources to carry through such a research program while fighting for their survival. As a result, Tube Alloys soon fell behind its American counterpart. and on 30 July 1942, Sir

John Anderson John Anderson may refer to:

Business

*John Anderson (Scottish businessman) (1747–1820), Scottish merchant and founder of Fermoy, Ireland

* John Byers Anderson (1817–1897), American educator, military officer and railroad executive, mentor of ...

, the minister responsible for Tube Alloys, advised Churchill that: "We must face the fact that ...

urpioneering work ... is a dwindling asset and that, unless we capitalise it quickly, we shall be outstripped. We now have a real contribution to make to a 'merger.' Soon we shall have little or none." That month Churchill and Roosevelt made an informal, unwritten agreement for atomic collaboration.

The opportunity for an equal partnership no longer existed, however, as shown in August 1942 when the British unsuccessfully demanded substantial control over the project while paying none of the costs. By 1943 the roles of the two countries had reversed from late 1941; in January Conant notified the British that they would no longer receive atomic information except in certain areas. While the British were shocked by the abrogation of the Churchill-Roosevelt agreement, head of the Canadian

National Research Council National Research Council may refer to:

* National Research Council (Canada), sponsoring research and development

* National Research Council (Italy), scientific and technological research, Rome

* National Research Council (United States), part of ...

C. J. Mackenzie was less surprised, writing "I can't help feeling that the United Kingdom group

ver Ver or VER may refer to:

* Voluntary Export Restraints, in international trade

* VER, the IATA airport code for General Heriberto Jara International Airport

* Volk's Electric Railway, Brighton, England

* VerPublishing, of the German group VDM Pub ...

emphasizes the importance of their contribution as compared with the Americans."

As Conant and Bush told the British, the order came "from the top".

The British bargaining position had worsened; the American scientists had decided that the United States no longer needed outside help, and they wanted to prevent Britain exploiting post-war commercial applications of atomic energy. The committee supported, and Roosevelt agreed to, restricting the flow of information to what Britain could use during the war—especially not bomb design—even if doing so slowed down the American project. By early 1943 the British stopped sending research and scientists to America, and as a result the Americans stopped all information sharing. The British considered ending the supply of Canadian uranium and heavy water to force the Americans to again share, but Canada needed American supplies to produce them. They investigated the possibility of an independent nuclear program, but determined that it could not be ready in time to affect the outcome of the

war in Europe.

By March 1943 Conant decided that British help would benefit some areas of the project.

James Chadwick

Sir James Chadwick, (20 October 1891 – 24 July 1974) was an English physicist who was awarded the 1935 Nobel Prize in Physics for his discovery of the neutron in 1932. In 1941, he wrote the final draft of the MAUD Report, which insp ...

and one or two other British scientists were important enough that the bomb design team at Los Alamos needed them, despite the risk of revealing weapon design secrets. In August 1943 Churchill and Roosevelt negotiated the

Quebec Agreement

The Quebec Agreement was a secret agreement between the United Kingdom and the United States outlining the terms for the coordinated development of the science and engineering related to nuclear energy and specifically nuclear weapons. It was s ...

, which resulted in a resumption of cooperation between scientists working on the same problem. Britain, however, agreed to restrictions on data on the building of large-scale production plants necessary for the bomb. The subsequent Hyde Park Agreement in September 1944 extended this cooperation to the postwar period. The Quebec Agreement established the

Combined Policy Committee

The Quebec Agreement was a secret agreement between the United Kingdom and the United States outlining the terms for the coordinated development of the science and engineering related to nuclear energy and specifically nuclear weapons. It was s ...

to coordinate the efforts of the United States, United Kingdom and Canada. Stimson, Bush and Conant served as the American members of the Combined Policy Committee, Field Marshal Sir

John Dill

Sir John Greer Dill, (25 December 1881 – 4 November 1944) was a senior British Army officer with service in both the First World War and the Second World War. From May 1940 to December 1941 he was the Chief of the Imperial General Staff (CIG ...

and Colonel

J. J. Llewellin were the British members, and

C. D. Howe was the Canadian member. Llewellin returned to the United Kingdom at the end of 1943 and was replaced on the committee by Sir

Ronald Ian Campbell

Sir Ronald Ian Campbell (7 June 1890 – 22 April 1983) was a British diplomat.

Campbell was the second son of Sir Guy Campbell, 3rd Baronet (see Campbell baronets), and Nina, daughter of Frederick Lehmann. He was educated at Eton and gradua ...

, who in turn was replaced by the British Ambassador to the United States,

Lord Halifax

Edward Frederick Lindley Wood, 1st Earl of Halifax, (16 April 1881 – 23 December 1959), known as The Lord Irwin from 1925 until 1934 and The Viscount Halifax from 1934 until 1944, was a senior British Conservative politician of the 193 ...

, in early 1945. Sir John Dill died in Washington, D.C., in November 1944 and was replaced both as Chief of the

British Joint Staff Mission

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English ...

and as a member of the Combined Policy Committee by Field Marshal Sir

Henry Maitland Wilson

Field Marshal Henry Maitland Wilson, 1st Baron Wilson, (5 September 1881 – 31 December 1964), also known as Jumbo Wilson, was a senior British Army officer of the 20th century. He saw active service in the Second Boer War and then during th ...

.

When cooperation resumed after the Quebec agreement, the Americans' progress and expenditures amazed the British. The United States had already spent more than $1 billion ($ billion today), while in 1943, the United Kingdom had spent about £0.5 million. Chadwick thus pressed for British involvement in the Manhattan Project to the fullest extent and abandoned any hopes of an independent British project during the war. With Churchill's backing, he attempted to ensure that every request from Groves for assistance was honored. The British Mission that arrived in the United States in December 1943 included

Niels Bohr

Niels Henrik David Bohr (; 7 October 1885 – 18 November 1962) was a Danish physicist who made foundational contributions to understanding atomic structure and quantum theory, for which he received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1922 ...

, Otto Frisch,

Klaus Fuchs

Klaus Emil Julius Fuchs (29 December 1911 – 28 January 1988) was a German theoretical physicist and atomic spy who supplied information from the American, British and Canadian Manhattan Project to the Soviet Union during and shortly a ...

, Rudolf Peierls, and

Ernest Titterton

Sir Ernest William Titterton (4 March 1916 – 8 February 1990) was a British nuclear physicist.

A graduate of the University of Birmingham, Titterton worked in a research position under Mark Oliphant, who recruited him to work on radar ...

. More scientists arrived in early 1944. While those assigned to gaseous diffusion left by the fall of 1944, the 35 working under Oliphant with Lawrence at Berkeley were assigned to existing laboratory groups and most stayed until the end of the war. The 19 sent to Los Alamos also joined existing groups, primarily related to implosion and bomb assembly, but not the plutonium-related ones. Part of the Quebec Agreement specified that nuclear weapons would not be used against another country without the mutual consent of the US and UK. In June 1945, Wilson agreed that the use of nuclear weapons against Japan would be recorded as a decision of the Combined Policy Committee.

The Combined Policy Committee created the

Combined Development Trust The Combined Development Agency (CDA), originally the Combined Development Trust (CDT), was a defense purchasing authority established in 1944 by the governments of the United States and the United Kingdom. Its role was to ensure adequate supplies ...

in June 1944, with Groves as its chairman, to procure uranium and

thorium ores on international markets. The

Belgian Congo

The Belgian Congo (french: Congo belge, ; nl, Belgisch-Congo) was a Belgian colony in Central Africa from 1908 until independence in 1960. The former colony adopted its present name, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), in 1964.

Colo ...

and Canada held much of the world's uranium outside Eastern Europe, and the

Belgian government in exile

The Belgian Government in London (french: Gouvernement belge à Londres, nl, Belgische regering in Londen), also known as the Pierlot IV Government, was the government in exile of Belgium between October 1940 and September 1944 during World W ...

was in London. Britain agreed to give the United States most of the Belgian ore, as it could not use most of the supply without restricted American research. In 1944, the Trust purchased of uranium oxide ore from companies operating mines in the Belgian Congo. In order to avoid briefing US Secretary of the Treasury

Henry Morgenthau Jr.

Henry Morgenthau Jr. (; May 11, 1891February 6, 1967) was the United States Secretary of the Treasury during most of the administration of Franklin D. Roosevelt. He played a major role in designing and financing the New Deal. After 1937, while ...

on the project, a special account not subject to the usual auditing and controls was used to hold Trust monies. Between 1944 and the time he resigned from the Trust in 1947, Groves deposited a total of $37.5 million into the Trust's account.

Groves appreciated the early British atomic research and the British scientists' contributions to the Manhattan Project, but stated that the United States would have succeeded without them. He also said that Churchill was "the best friend the atomic bomb project had

she kept Roosevelt's interest up ... He just stirred him up all the time by telling him how important he thought the project was."

The British wartime participation was crucial to the success of the United Kingdom's

independent nuclear weapons program after the war when the

McMahon Act

The Atomic Energy Act of 1946 (McMahon Act) determined how the United States would control and manage the nuclear technology it had jointly developed with its World War II allies, the United Kingdom and Canada. Most significantly, the Act rule ...

of 1946 temporarily ended American nuclear cooperation.

Project sites

Image:Manhattan Project US Canada Map 2.svg, upright=3.2, center, A selection of US and Canadian sites important to the Manhattan Project. Click on the location for more information., alt=Map of the United States and southern Canada with major project sites marked

circle 50 280 20 Berkeley, California

Berkeley ( ) is a city on the eastern shore of San Francisco Bay in northern Alameda County, California, United States. It is named after the 18th-century Irish bishop and philosopher George Berkeley. It borders the cities of Oakland and Emer ...

circle 140 400 20 Inyokern, California

Inyokern (formerly Siding 16 and Magnolia) is a census-designated place (CDP) in Kern County, California, United States. Its name derives from its location near the border between Inyo and Kern Counties. Inyokern is located west of Ridgecrest, at ...

circle 170 100 20 Richland, Washington

Richland () is a city in Benton County, Washington, United States. It is located in southeastern Washington at the confluence of the Yakima and the Columbia Rivers. As of the 2020 census, the city's population was 60,560. Along with the nearby c ...

circle 220 20 20 Trail, British Columbia

Trail is a city in the West Kootenay region of the Interior of British Columbia, Canada. It was named after the Dewdney Trail, which passed through the area. The town was first called Trail Creek or Trail Creek Landing, and the name was shorte ...

circle 230 270 20 Wendover, Utah

Wendover is a city on the western edge of Tooele County, Utah, United States. The population was 1,115 at the 2020 census.

Description

Wendover is on the western border of Utah and is contiguous with West Wendover, Nevada. Interstate 80 runs j ...

circle 290 360 20 Monticello, Utah

Monticello ( ) is a city located in San Juan County, Utah, United States and is the county seat. It is the second most populous city in San Juan County, with a population of 1,972 at the 2010 census. The Monticello area was settled in July 1887 ...

circle 320 360 20 Uravan, Colorado

Uravan (a contraction of uranium/vanadium) is a former uranium mining town in western Montrose County, Colorado, United States, which still appears on some maps. The town was a company town established by U. S. Vanadium Corporation in 1936 to ...

circle 340 440 20 Los Alamos, New Mexico

Los Alamos is an census-designated place in Los Alamos County, New Mexico, Los Alamos County, New Mexico, United States, that is recognized as the development and creation place of the Nuclear weapon, atomic bomb—the primary objective of the ...

circle 340 500 20 Alamogordo, New Mexico

circle 610 290 20 Ames, Iowa

Ames () is a city in Story County, Iowa, United States, located approximately north of Des Moines in central Iowa. It is best known as the home of Iowa State University (ISU), with leading agriculture, design, engineering, and veterinary med ...

circle 660 400 20 St Louis, Missouri

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the bi-state metropolitan area, which e ...

circle 710 310 20 Chicago, Illinois

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = List of sovereign states, Count ...