Maimonides on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Moses ben Maimon (1138–1204), commonly known as Maimonides (, ) and also referred to by the Hebrew acronym Rambam (), was a

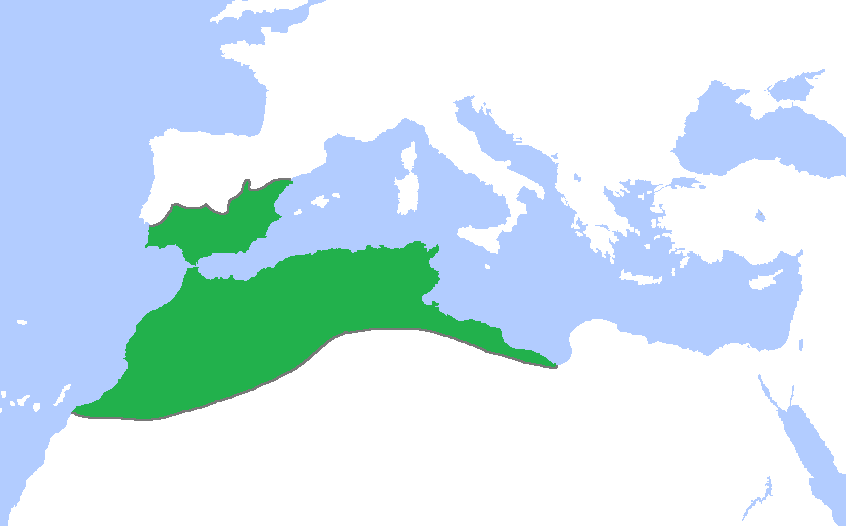

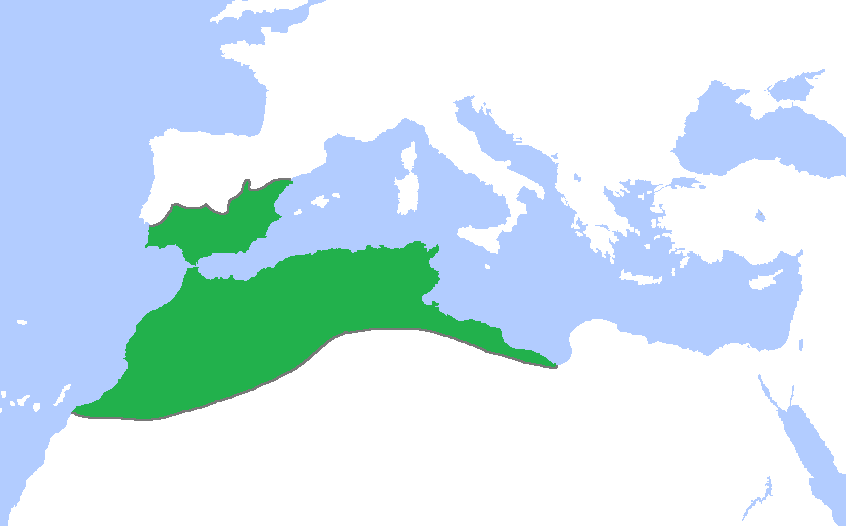

Maimonides was born 1138 (or 1135) in Córdoba in the

Maimonides was born 1138 (or 1135) in Córdoba in the

A

A

Around 1171, Maimonides was appointed the of the Egyptian Jewish community. Arabist Shelomo Dov Goitein believes the leadership he displayed during the ransoming of the Crusader captives led to this appointment. However he was replaced by Sar Shalom ben Moses in 1173. Over the controversial course of Sar Shalom's appointment, during which Sar Shalom was accused of tax farming, Maimonides excommunicated and fought with him for several years until Maimonides was appointed Nagid in 1195. A work known as "Megillat Zutta" was written by Abraham ben Hillel, who writes a scathing description of Sar Shalom while praising Maimonides as "the light of east and west and unique master and marvel of the generation."

Around 1171, Maimonides was appointed the of the Egyptian Jewish community. Arabist Shelomo Dov Goitein believes the leadership he displayed during the ransoming of the Crusader captives led to this appointment. However he was replaced by Sar Shalom ben Moses in 1173. Over the controversial course of Sar Shalom's appointment, during which Sar Shalom was accused of tax farming, Maimonides excommunicated and fought with him for several years until Maimonides was appointed Nagid in 1195. A work known as "Megillat Zutta" was written by Abraham ben Hillel, who writes a scathing description of Sar Shalom while praising Maimonides as "the light of east and west and unique master and marvel of the generation."

In his medical writings, Maimonides described many conditions, including

In his medical writings, Maimonides described many conditions, including

Maimonides died on 12 December 1204 (20th of Tevet 4965) in Fustat. A variety of medieval sources beginning with Al-Qifti maintain that his body was interred near Lake Tiberias, though there is no contemporary evidence for his removal from Egypt. Gedaliah ibn Yahya records that "He was buried in the Upper Galilee with elegies upon his gravestone. In the time of avidKimhi, when the sons of Belial rose up to besmirch aimonides. . . they did evil. They altered his gravestone, which previously had been inscribed 'choicest of the human race (מבחר המין האנושי)', so that instead it read 'the excommunicated heretic (מוחרם ומין)'. But later, after the provocateurs had repented of their act, and praised this great man, a student repaired the gravestone to read 'choicest of the Israelites (מבחר המין הישראלי)'". Today, Tiberias hosts the Tomb of Maimonides, on which is inscribed "From

Maimonides died on 12 December 1204 (20th of Tevet 4965) in Fustat. A variety of medieval sources beginning with Al-Qifti maintain that his body was interred near Lake Tiberias, though there is no contemporary evidence for his removal from Egypt. Gedaliah ibn Yahya records that "He was buried in the Upper Galilee with elegies upon his gravestone. In the time of avidKimhi, when the sons of Belial rose up to besmirch aimonides. . . they did evil. They altered his gravestone, which previously had been inscribed 'choicest of the human race (מבחר המין האנושי)', so that instead it read 'the excommunicated heretic (מוחרם ומין)'. But later, after the provocateurs had repented of their act, and praised this great man, a student repaired the gravestone to read 'choicest of the Israelites (מבחר המין הישראלי)'". Today, Tiberias hosts the Tomb of Maimonides, on which is inscribed "From

Maimonides composed works of Jewish scholarship, rabbinic law, philosophy, and medical texts. Most of Maimonides' works were written in

Maimonides composed works of Jewish scholarship, rabbinic law, philosophy, and medical texts. Most of Maimonides' works were written in

Maimonides equated the God of Abraham to what philosophers refer to as the Necessary Being. God is unique in the universe, and the Torah commands that one

Maimonides equated the God of Abraham to what philosophers refer to as the Necessary Being. God is unique in the universe, and the Torah commands that one

"Maimonides' Conception of God/"

''My Jewish Learning''. 30 April 2018. Maimonides argued adamantly that God is not corporeal. This was central to his thinking about the sin of

Weaning Away from Idolatry: Maimonides on the Purpose of Ritual Sacrifices

", ''Religions'' 12(5), 363. Maimonides also argued that God embodied

Maimonides' is considered by Jews even today as one of the chief authoritative codifications of Jewish law and ethics. It is exceptional for its logical construction, concise and clear expression and extraordinary learning, so that it became a standard against which other later codifications were often measured. It is still closely studied in rabbinic (seminaries). The first to compile a comprehensive lexicon containing an alphabetically arranged list of difficult words found in Maimonides' was Tanḥum ha-Yerushalmi (1220–1291). A popular medieval saying that also served as his

Maimonides' is considered by Jews even today as one of the chief authoritative codifications of Jewish law and ethics. It is exceptional for its logical construction, concise and clear expression and extraordinary learning, so that it became a standard against which other later codifications were often measured. It is still closely studied in rabbinic (seminaries). The first to compile a comprehensive lexicon containing an alphabetically arranged list of difficult words found in Maimonides' was Tanḥum ha-Yerushalmi (1220–1291). A popular medieval saying that also served as his

He is buried in HaRambam compound in

He is buried in HaRambam compound in

www.islamsci.mcgill.ca

* * * * * Dov Schwartz,

The Many Faces of Maimonides

', Boston: Academic Studies Press 2018.

Maimonides entry

in the ''Jewish Encyclopedia'' (1906)

Maimonides entry in the Encyclopædia Britannica

Maimonides entry

in the ''Encyclopaedia Judaica'', 2nd edition (2007) *

"Maimonides entry in the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy"

Video lecture on Maimonides

by Dr. Henry Abramson

Maimonides, a biography

— book by David Yellin and Israel Abrahams

Maimonides as a Philosopher

The Influence of Islamic Thought on Maimonides

Article from ''Policy Review''

Rambam and the Earth: Maimonides as a Proto-Ecological Thinker

nbsp;– reprint on neohasid.org from The Encyclopedia of Religion and Ecology

by Jose Faur, describing the controversy surrounding Maimonides' works * David Yellin and Israel Abrahams,

' (1903) (full text of a biography) *

PDF version

* Maimonides a

intellectualencounters.org

* * *

The Guide: An Explanatory Commentary on Each Chapter of Maimonides' Guide of The Perplexed

' by Scott Michael Alexander (covers all of Book I, currently) ;Maimonides' works

Steinberg The Rambam Mishneh Torah Codex on ''Amazon''

Steinberg The Rambam Chumash on ''Amazon''

Oral Readings of Mishne Torah

— Free listening and Download, site also had classes in Maimonides' '' Iggereth Teiman''

Maimonides 13 Principles

Intellectual Encounters – Main Thinkers – Moses Maimonides

i

intellectualencounters.org

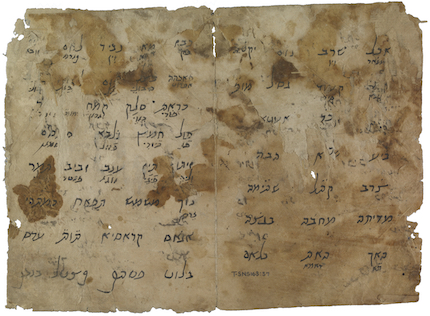

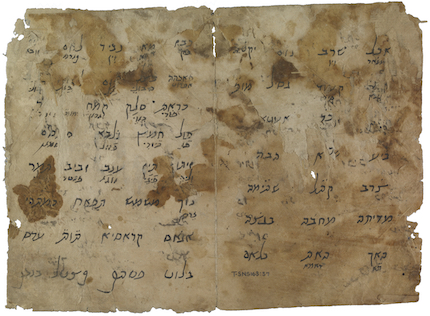

Maimonides, Mishneh Torah, Autograph Draft

, Egypt, 1180

Ilana Tahan * [https://search.cjh.org/primo-explore/search?query=creator,contains,Moses%20Maimonides,AND&tab=default_tab&search_scope=LBI&vid=lbi&facet=tlevel,include,online_resources&facet=creator,include,Maimonides,%20M&mode=advanced&offset=0 Digitized works by Maimonides] at the Leo Baeck Institute ;Texts by Maimonides

Siddur Mesorath Moshe

a prayerbook based on the early Jewish liturgy as found in Maimonides' Mishne Tora

)

* ttp://www.sacred-texts.com/jud/gfp/index.htm The Guide For the Perplexed by Moses Maimonides translated into English by Michael Friedländer

Writings of Maimonides; manuscripts and early print editions. Jewish National and University Library

Facsimile edition of Moreh Nevukhim/The Guide for the Perplexed (illuminated Hebrew manuscript, Barcelona, 1347–48). The Royal Library, Copenhagen

of Judeo-Arabic letters and manuscripts written by or to Maimonides. It includes the last letter his brother David sent him before drowning at sea. * A. Ashur

A newly discovered medical recipe written by Maimonides

* M.A Friedman and A. Ashur

A newly-discovered autograph responsum of Maimonides

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Maimonides 1130s births 1204 deaths 12th-century Arabic-language writers 12th-century Jewish theologians 12th-century Sephardi Jews 12th-century Egyptian physicians 12th-century philosophers 13th-century philosophers Aristotelian philosophers Egyptian philosophers Authors of books on Jewish law Commentaries on the Mishnah Court physicians Exponents of Jewish law Jewish astronomers Jewish ethicists Jewish legal scholars Jewish refugees Jews and Judaism in the Kingdom of Jerusalem Judeo-Arabic writers Medieval Jewish astronomers Medieval Jewish physicians of Spain Medieval Jewish physicians of Egypt Rabbis from Córdoba, Spain Philosophers from al-Andalus Philosophers of Judaism Medieval Jewish philosophers Sephardi rabbis University of al-Qarawiyyin alumni Physicians from the Ayyubid Sultanate Holy Land travellers Medieval Jewish scholars

Sephardic

Sephardic Jews, also known as Sephardi Jews or Sephardim, and rarely as Iberian Peninsular Jews, are a Jewish diaspora population associated with the historic Jewish communities of the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal) and their descendant ...

rabbi and philosopher

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

who became one of the most prolific and influential Torah

The Torah ( , "Instruction", "Teaching" or "Law") is the compilation of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, namely the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. The Torah is also known as the Pentateuch () ...

scholars of the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

. In his time, he was also a preeminent astronomer

An astronomer is a scientist in the field of astronomy who focuses on a specific question or field outside the scope of Earth. Astronomers observe astronomical objects, such as stars, planets, natural satellite, moons, comets and galaxy, galax ...

and physician

A physician, medical practitioner (British English), medical doctor, or simply doctor is a health professional who practices medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring health through the Medical education, study, Med ...

, serving as the personal physician of Saladin

Salah ad-Din Yusuf ibn Ayyub ( – 4 March 1193), commonly known as Saladin, was the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty. Hailing from a Kurdish family, he was the first sultan of both Egypt and Syria. An important figure of the Third Crusade, h ...

. He was born on Passover

Passover, also called Pesach (; ), is a major Jewish holidays, Jewish holiday and one of the Three Pilgrimage Festivals. It celebrates the Exodus of the Israelites from slavery in Biblical Egypt, Egypt.

According to the Book of Exodus, God in ...

eve 1138 or 1135, and lived in Córdoba in al-Andalus

Al-Andalus () was the Muslim-ruled area of the Iberian Peninsula. The name refers to the different Muslim states that controlled these territories at various times between 711 and 1492. At its greatest geographical extent, it occupied most o ...

(now in Spain) within the Almoravid Empire until his family was expelled for refusing to convert to Islam. Later, he lived in Morocco and Egypt and worked as a rabbi, physician and philosopher.

During his lifetime, most Jews greeted Maimonides' writings on Jewish law

''Halakha'' ( ; , ), also transliterated as ''halacha'', ''halakhah'', and ''halocho'' ( ), is the collective body of Jewish religious laws that are derived from the Written and Oral Torah. ''Halakha'' is based on biblical commandments ('' mit ...

and ethics

Ethics is the philosophy, philosophical study of Morality, moral phenomena. Also called moral philosophy, it investigates Normativity, normative questions about what people ought to do or which behavior is morally right. Its main branches inclu ...

with acclaim and gratitude, even as far away as Iraq and Yemen. Yet, while Maimonides rose to become the revered head of the Jewish community in Egypt, his writings also had vociferous critics, particularly in Spain. He died in Fustat, Egypt, and, according to Jewish tradition, was buried in Tiberias

Tiberias ( ; , ; ) is a city on the western shore of the Sea of Galilee in northern Israel. A major Jewish center during Late Antiquity, it has been considered since the 16th century one of Judaism's Four Holy Cities, along with Jerusalem, Heb ...

. His tomb in Tiberias is a popular pilgrimage and tourist site.

He was posthumously acknowledged as one of the foremost rabbinic decisors and philosophers in Jewish history

Jewish history is the history of the Jews, their Jewish peoplehood, nation, Judaism, religion, and Jewish culture, culture, as it developed and interacted with other peoples, religions and cultures.

Jews originated from the Israelites and H ...

, and his copious work comprises a cornerstone of Jewish scholarship. His fourteen-volume still carries significant canonical authority as a codification of ''halakha

''Halakha'' ( ; , ), also Romanization of Hebrew, transliterated as ''halacha'', ''halakhah'', and ''halocho'' ( ), is the collective body of Judaism, Jewish religious laws that are derived from the Torah, Written and Oral Torah. ''Halakha'' is ...

''.

Aside from being revered by Jewish historians, Maimonides also figures very prominently in the history of Islamic and Arab sciences. Influenced by Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

, Al-Farabi

file:A21-133 grande.webp, thumbnail, 200px, Postage stamp of the USSR, issued on the 1100th anniversary of the birth of Al-Farabi (1975)

Abu Nasr Muhammad al-Farabi (; – 14 December 950–12 January 951), known in the Greek East and Latin West ...

, Ibn Sina

Ibn Sina ( – 22 June 1037), commonly known in the West as Avicenna ( ), was a preeminent philosopher and physician of the Muslim world, flourishing during the Islamic Golden Age, serving in the courts of various Iranian peoples, Iranian ...

, and his contemporary Ibn Rushd, he became a prominent philosopher and polymath

A polymath or polyhistor is an individual whose knowledge spans many different subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific problems. Polymaths often prefer a specific context in which to explain their knowledge, ...

in both the Jewish and Islamic worlds.

Name

Maimonides referred to himself as "Moses, son of Rabbi Maimon the Spaniard" (). In Medieval Hebrew, he was usually called , short for "our Rabbi Moshe", but mostly he is called , short for "our Rabbi, Moshe son of Maimon" and pronounced ''Rambam''. In Arabic, he is sometimes called "Moses ' son ofAmram

In the Book of Exodus, Amram (; ) is the husband of Jochebed and father of Aaron, Moses and Miriam.

In the Holy Scriptures

In addition to being married to Jochebed, Amram is also described in the Bible as having been related to Jochebed ...

' son of Maimon, of Obadiah, the Cordoban" (, ''Abū ʿImrān Mūsā bin Maimūn bin ʿUbaydallāh al-Qurṭubī''), or more often simply "Moses, son of Maimon" ().

In Greek, the Hebrew ('son of') becomes the patronymic

A patronymic, or patronym, is a component of a personal name based on the given name of one's father, grandfather (more specifically an avonymic), or an earlier male ancestor. It is the male equivalent of a matronymic.

Patronymics are used, b ...

suffix '' -ides'', forming Μωησής Μαϊμονίδης "Moses Maimonides".

He is sometimes known as "The Great Eagle" ().

Biography

Early years

Maimonides was born 1138 (or 1135) in Córdoba in the

Maimonides was born 1138 (or 1135) in Córdoba in the Muslim

Muslims () are people who adhere to Islam, a Monotheism, monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God ...

-ruled Almoravid Caliphate, at the end of the golden age of Jewish culture in the Iberian Peninsula

The golden age of Jewish culture in Spain was a Muslim ruled era of Spain, with the state name of Al-Andalus, lasting 800 years, whose state lasted from 711 to 1492 A.D. This coincides with the Islamic Golden Age within Islamic empire, Muslim r ...

after the first centuries of Muslim rule. His father, Maimon ben Joseph, was a dayyan or rabbinic judge. Aaron ben Jacob ha-Kohen later wrote that he had traced Maimonides' descent back to Simeon ben Judah ha-Nasi from the Davidic line

The Davidic line refers to the descendants of David, who established the House of David ( ) in the Kingdom of Israel (united monarchy), Kingdom of Israel and the Kingdom of Judah. In Judaism, the lineage is based on texts from the Hebrew Bible ...

. His ancestry, going back four generations, is given in his '' Epistle to Yemen'' as Moses ben Maimon ben Joseph ben Isaac ben Obadiah. At the end of his commentary on the Mishnah

The Mishnah or the Mishna (; , from the verb ''šānā'', "to study and review", also "secondary") is the first written collection of the Jewish oral traditions that are known as the Oral Torah. Having been collected in the 3rd century CE, it is ...

, however, a longer, slightly different genealogy is given: Moses ben Maimon ben Joseph ben Isaac ben Joseph ben Obadiah ben Solomon ben Obadiah.

Maimonides studied Torah under his father, who had in turn studied under Joseph ibn Migash, a student of Isaac Alfasi

Isaac ben Jacob Alfasi (1013–1103) (, ), also known as the Alfasi or by his Hebrew acronym, the Rif (Rabbi Isaac al-Fasi), was a Maghrebi Talmudist and posek (decider in matters of halakha, Jewish law). He is best known for his work of '' ...

. At an early age, Maimonides developed an interest in sciences and philosophy. He read ancient Greek philosophy

Ancient Greek philosophy arose in the 6th century BC. Philosophy was used to make sense of the world using reason. It dealt with a wide variety of subjects, including astronomy, epistemology, mathematics, political philosophy, ethics, metaphysics ...

accessible via Arabic translations and was deeply immersed in the sciences and learning of Islamic culture

Islamic cultures or Muslim cultures refers to the historic cultural practices that developed among the various peoples living in the Muslim world. These practices, while not always religious in nature, are generally influenced by aspects of Islam ...

.

Maimonides, who was revered for his personality as well as for his writings, led a busy life, and wrote many of his works while travelling or in temporary accommodation.1954 ''Encyclopedia Americana'', vol. 18, p. 140.

Exile

Berber

Berber or Berbers may refer to:

Ethnic group

* Berbers, an ethnic group native to Northern Africa

* Berber languages, a family of Afro-Asiatic languages

Places

* Berber, Sudan, a town on the Nile

People with the surname

* Ady Berber (1913–196 ...

dynasty, the Almohads, conquered Córdoba in 1148 and abolished status (i.e., state protection of non-Muslims ensured through payment of a tax, the ) in some of their territories. The loss of this status forced the Jewish

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

and Christian communities to choose between conversion to Islam

Reversion to Islam, also known within Islam as reversion, is adopting Islam as a religion or faith. Conversion requires a formal statement of the '' shahādah'', the credo of Islam, whereby the prospective convert must state that "there is none w ...

, death

Death is the end of life; the irreversible cessation of all biological functions that sustain a living organism. Death eventually and inevitably occurs in all organisms. The remains of a former organism normally begin to decompose sh ...

, or exile

Exile or banishment is primarily penal expulsion from one's native country, and secondarily expatriation or prolonged absence from one's homeland under either the compulsion of circumstance or the rigors of some high purpose. Usually persons ...

. Many Jews were forced to convert, but due to suspicion by the authorities of fake conversions, the new converts had to wear identifying clothing that set them apart and made them subject to public scrutiny.

Maimonides' family, along with many other Jews

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

, chose exile. For the next ten years, Maimonides moved about in southern Spain and North Africa, eventually settling in Fez, Morocco

Fez () or Fes (; ) is a city in northern inland Morocco and the capital of the Fez-Meknes, Fez-Meknes administrative region. It is one of the List of cities in Morocco, largest cities in Morocco, with a population of 1.256 million, according to ...

. Some say that his teacher in Fez was Rabbi Yehuda Ha-Cohen Ibn Susan, until the latter was killed in 1165.

During this time, he composed his acclaimed commentary on the Mishnah

The Mishnah or the Mishna (; , from the verb ''šānā'', "to study and review", also "secondary") is the first written collection of the Jewish oral traditions that are known as the Oral Torah. Having been collected in the 3rd century CE, it is ...

, during the years 1166–1168.

Following this sojourn in Morocco, he lived in Acre

The acre ( ) is a Unit of measurement, unit of land area used in the Imperial units, British imperial and the United States customary units#Area, United States customary systems. It is traditionally defined as the area of one Chain (unit), ch ...

with his father and brother, before settling in Fustat in Fatimid Caliphate

The Fatimid Caliphate (; ), also known as the Fatimid Empire, was a caliphate extant from the tenth to the twelfth centuries CE under the rule of the Fatimids, an Isma'ili Shi'a dynasty. Spanning a large area of North Africa and West Asia, i ...

-controlled Egypt by 1168. There is mention that Maimonides first settled in Alexandria, and moved to Fustat only in 1171. While in Cairo

Cairo ( ; , ) is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Egypt and the Cairo Governorate, being home to more than 10 million people. It is also part of the List of urban agglomerations in Africa, largest urban agglomeration in Africa, L ...

, he studied in a yeshiva

A yeshiva (; ; pl. , or ) is a traditional Jewish educational institution focused on the study of Rabbinic literature, primarily the Talmud and halacha (Jewish law), while Torah and Jewish philosophy are studied in parallel. The stu ...

attached to a small synagogue

A synagogue, also called a shul or a temple, is a place of worship for Jews and Samaritans. It is a place for prayer (the main sanctuary and sometimes smaller chapels) where Jews attend religious services or special ceremonies such as wed ...

, which now bears his name. Goitein, S.D. ''Letters of Medieval Jewish Traders'', Princeton University Press, 1973 (), p. 208 In Jerusalem

Jerusalem is a city in the Southern Levant, on a plateau in the Judaean Mountains between the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and the Dead Sea. It is one of the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest cities in the world, and ...

, he prayed at the Temple Mount

The Temple Mount (), also known as the Noble Sanctuary (Arabic: الحرم الشريف, 'Haram al-Sharif'), and sometimes as Jerusalem's holy esplanade, is a hill in the Old City of Jerusalem, Old City of Jerusalem that has been venerated as a ...

. He wrote that this day of visiting the Temple Mount was a day of holiness for him and his descendants.

Maimonides shortly thereafter was instrumental in helping rescue Jews taken captive during the Christian Amalric of Jerusalem's siege of the southeastern Nile Delta

The Nile Delta (, or simply , ) is the River delta, delta formed in Lower Egypt where the Nile River spreads out and drains into the Mediterranean Sea. It is one of the world's larger deltas—from Alexandria in the west to Port Said in the eas ...

town of Bilbeis

Bilbeis ( ; Bohairic ' is an ancient fortress city on the eastern edge of the southern Nile Delta in Egypt, the site of the ancient city and former bishopric of Phelbes and a Latin Catholic titular see.

The city is small in size but dens ...

. He sent five letters to the Jewish communities of Lower Egypt

Lower Egypt ( ') is the northernmost region of Egypt, which consists of the fertile Nile Delta between Upper Egypt and the Mediterranean Sea, from El Aiyat, south of modern-day Cairo, and Dahshur. Historically, the Nile River split into sev ...

asking them to pool money together to pay the ransom

Ransom refers to the practice of holding a prisoner or item to extort money or property to secure their release. It also refers to the sum of money paid by the other party to secure a captive's freedom.

When ransom means "payment", the word ...

. The money was collected and then given to two judges sent to Palestine to negotiate with the Crusaders. The captives were eventually released.

Death of his brother

Following this success, the Maimonides family, hoping to increase their wealth, gave their savings to his brother, the youngest son David ben Maimon, a merchant. Maimonides directed his brother to procure goods only at theSudan

Sudan, officially the Republic of the Sudan, is a country in Northeast Africa. It borders the Central African Republic to the southwest, Chad to the west, Libya to the northwest, Egypt to the north, the Red Sea to the east, Eritrea and Ethiopi ...

ese port of ʿAydhab. After a long, arduous trip through the desert, however, David was unimpressed by the goods on offer there. Against his brother's wishes, David boarded a ship for India, since great wealth was to be found in the East. Before he could reach his destination, David drowned at sea sometime between 1169 and 1177. The death of his brother caused Maimonides to become sick with grief.

In a letter discovered in the Cairo Geniza

The Cairo Geniza, alternatively spelled the Cairo Genizah, is a collection of some 400,000 Judaism, Jewish manuscript fragments and Fatimid Caliphate, Fatimid administrative documents that were kept in the ''genizah'' or storeroom of the Ben Ezra ...

, he wrote:

Nagid

Around 1171, Maimonides was appointed the of the Egyptian Jewish community. Arabist Shelomo Dov Goitein believes the leadership he displayed during the ransoming of the Crusader captives led to this appointment. However he was replaced by Sar Shalom ben Moses in 1173. Over the controversial course of Sar Shalom's appointment, during which Sar Shalom was accused of tax farming, Maimonides excommunicated and fought with him for several years until Maimonides was appointed Nagid in 1195. A work known as "Megillat Zutta" was written by Abraham ben Hillel, who writes a scathing description of Sar Shalom while praising Maimonides as "the light of east and west and unique master and marvel of the generation."

Around 1171, Maimonides was appointed the of the Egyptian Jewish community. Arabist Shelomo Dov Goitein believes the leadership he displayed during the ransoming of the Crusader captives led to this appointment. However he was replaced by Sar Shalom ben Moses in 1173. Over the controversial course of Sar Shalom's appointment, during which Sar Shalom was accused of tax farming, Maimonides excommunicated and fought with him for several years until Maimonides was appointed Nagid in 1195. A work known as "Megillat Zutta" was written by Abraham ben Hillel, who writes a scathing description of Sar Shalom while praising Maimonides as "the light of east and west and unique master and marvel of the generation."

Physician

With the loss of the family funds tied up in David's business venture, Maimonides assumed the vocation of physician, for which he was to become famous. He had trained in medicine in both Spain and in Fez. Gaining widespread recognition, he was appointed court physician to al-Qadi al-Fadil, the chief secretary to SultanSaladin

Salah ad-Din Yusuf ibn Ayyub ( – 4 March 1193), commonly known as Saladin, was the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty. Hailing from a Kurdish family, he was the first sultan of both Egypt and Syria. An important figure of the Third Crusade, h ...

, then to Saladin himself; after whose death he remained a physician to the Ayyubid dynasty

The Ayyubid dynasty (), also known as the Ayyubid Sultanate, was the founding dynasty of the medieval Sultan of Egypt, Sultanate of Egypt established by Saladin in 1171, following his abolition of the Fatimid Caliphate, Fatimid Caliphate of Egyp ...

.

In his medical writings, Maimonides described many conditions, including

In his medical writings, Maimonides described many conditions, including asthma

Asthma is a common long-term inflammatory disease of the airways of the lungs. It is characterized by variable and recurring symptoms, reversible airflow obstruction, and easily triggered bronchospasms. Symptoms include episodes of wh ...

, diabetes

Diabetes mellitus, commonly known as diabetes, is a group of common endocrine diseases characterized by sustained high blood sugar levels. Diabetes is due to either the pancreas not producing enough of the hormone insulin, or the cells of th ...

, hepatitis

Hepatitis is inflammation of the liver parenchyma, liver tissue. Some people or animals with hepatitis have no symptoms, whereas others develop yellow discoloration of the skin and whites of the eyes (jaundice), Anorexia (symptom), poor appetite ...

, and pneumonia

Pneumonia is an Inflammation, inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as Pulmonary alveolus, alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of Cough#Classification, productive or dry cough, ches ...

, and he emphasized moderation and a healthy lifestyle. His treatises became influential for generations of physicians. He was knowledgeable about Greek and Arabic medicine, and followed the principles of humorism

Humorism, the humoral theory, or humoralism, was a system of medicine detailing a supposed makeup and workings of the human body, adopted by Ancient Greek and Roman physicians and philosophers.

Humorism began to fall out of favor in the 17th ce ...

in the tradition of Galen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus (; September 129 – AD), often Anglicization, anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Ancient Rome, Roman and Greeks, Greek physician, surgeon, and Philosophy, philosopher. Considered to be one o ...

. He did not blindly accept authority but used his own observation and experience. Julia Bess Frank indicates that Maimonides in his medical writings sought to interpret works of authorities so that they could become acceptable. Maimonides displayed in his interactions with patients attributes that today would be called intercultural awareness and respect for the patient's autonomy

In developmental psychology and moral, political, and bioethical philosophy, autonomy is the capacity to make an informed, uncoerced decision. Autonomous organizations or institutions are independent or self-governing. Autonomy can also be ...

. Although he frequently wrote of his longing for solitude in order to come closer to God and to extend his reflections—elements considered essential in his philosophy to the prophetic experience—he gave over most of his time to caring for others. In a famous letter, Maimonides describes his daily routine. After visiting the Sultan's palace, he would arrive home exhausted and hungry, where "I would find the antechambers filled with gentiles and Jews ..I would go to heal them, and write prescriptions for their illnesses ..until the evening ..and I would be extremely weak."

As he goes on to say in this letter, even on Shabbat

Shabbat (, , or ; , , ) or the Sabbath (), also called Shabbos (, ) by Ashkenazi Hebrew, Ashkenazim, is Judaism's day of rest on the seventh day of the seven-day week, week—i.e., Friday prayer, Friday–Saturday. On this day, religious Jews ...

he would receive members of the community. Still, he managed to write extended treatises, including not only medical and other scientific studies but some of the most systematically thought-through and influential treatises on halakha

''Halakha'' ( ; , ), also Romanization of Hebrew, transliterated as ''halacha'', ''halakhah'', and ''halocho'' ( ), is the collective body of Judaism, Jewish religious laws that are derived from the Torah, Written and Oral Torah. ''Halakha'' is ...

(rabbinic law) and Jewish philosophy of the Middle Ages.

In 1172–74, Maimonides wrote his famous '' Epistle to Yemen''. It has been suggested that his "incessant travail" undermined his own health and brought about his death at 69 (although this is a normal lifespan).

Death

Maimonides died on 12 December 1204 (20th of Tevet 4965) in Fustat. A variety of medieval sources beginning with Al-Qifti maintain that his body was interred near Lake Tiberias, though there is no contemporary evidence for his removal from Egypt. Gedaliah ibn Yahya records that "He was buried in the Upper Galilee with elegies upon his gravestone. In the time of avidKimhi, when the sons of Belial rose up to besmirch aimonides. . . they did evil. They altered his gravestone, which previously had been inscribed 'choicest of the human race (מבחר המין האנושי)', so that instead it read 'the excommunicated heretic (מוחרם ומין)'. But later, after the provocateurs had repented of their act, and praised this great man, a student repaired the gravestone to read 'choicest of the Israelites (מבחר המין הישראלי)'". Today, Tiberias hosts the Tomb of Maimonides, on which is inscribed "From

Maimonides died on 12 December 1204 (20th of Tevet 4965) in Fustat. A variety of medieval sources beginning with Al-Qifti maintain that his body was interred near Lake Tiberias, though there is no contemporary evidence for his removal from Egypt. Gedaliah ibn Yahya records that "He was buried in the Upper Galilee with elegies upon his gravestone. In the time of avidKimhi, when the sons of Belial rose up to besmirch aimonides. . . they did evil. They altered his gravestone, which previously had been inscribed 'choicest of the human race (מבחר המין האנושי)', so that instead it read 'the excommunicated heretic (מוחרם ומין)'. But later, after the provocateurs had repented of their act, and praised this great man, a student repaired the gravestone to read 'choicest of the Israelites (מבחר המין הישראלי)'". Today, Tiberias hosts the Tomb of Maimonides, on which is inscribed "From Moses

In Abrahamic religions, Moses was the Hebrews, Hebrew prophet who led the Israelites out of slavery in the The Exodus, Exodus from ancient Egypt, Egypt. He is considered the most important Prophets in Judaism, prophet in Judaism and Samaritani ...

to Moses arose none like Moses."

Maimonides and his wife, the daughter of Mishael ben Yeshayahu Halevi, had one child who survived into adulthood, Abraham Maimonides, who became recognized as a great scholar. He succeeded Maimonides as Nagid and as court physician

A physician, medical practitioner (British English), medical doctor, or simply doctor is a health professional who practices medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring health through the Medical education, study, Med ...

at the age of eighteen. Throughout his career, he defended his father's writings against all critics. The office of Nagid was held by the Maimonides family for four successive generations until the end of the 14th century.

A statue of Maimonides was erected near the Córdoba Synagogue.

Maimonides is sometimes said to be a descendant of King David

David (; , "beloved one") was a king of ancient Israel and Judah and the third king of the United Monarchy, according to the Hebrew Bible and Old Testament.

The Tel Dan stele, an Aramaic-inscribed stone erected by a king of Aram-Damas ...

, although he never made such a claim.

Works

Mishneh Torah

With , Maimonides composed a code ofJewish law

''Halakha'' ( ; , ), also transliterated as ''halacha'', ''halakhah'', and ''halocho'' ( ), is the collective body of Jewish religious laws that are derived from the Written and Oral Torah. ''Halakha'' is based on biblical commandments ('' mit ...

with the widest-possible scope and depth. The work gathers all the binding laws from the Talmud

The Talmud (; ) is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and the primary source of Jewish religious law (''halakha'') and Jewish theology. Until the advent of Haskalah#Effects, modernity, in nearly all Jewish communities, the Talmud was the cen ...

, and incorporates the positions of the Geonim

''Geonim'' (; ; also Romanization of Hebrew, transliterated Gaonim, singular Gaon) were the presidents of the two great Talmudic Academies in Babylonia, Babylonian Talmudic Academies of Sura Academy , Sura and Pumbedita Academy , Pumbedita, in t ...

(post-Talmudic early medieval scholars, mainly from Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia is a historical region of West Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the Fertile Crescent. Today, Mesopotamia is known as present-day Iraq and forms the eastern geographic boundary of ...

). It is also known as or simply () which has the numerical value 14, representing the 14 books of the work. The ''Mishneh Torah'' made following Jewish law easier for the Jews of his time, who were struggling to understand the complex nature of Jewish rules and regulations as they had adapted over the years.

Later codes of Jewish law, e.g. Arba'ah Turim

''Arba'ah Turim'' (), often called simply the ''Tur'', is an important Halakha#Codes of Jewish law, Halakhic code composed by Yaakov ben Asher (Cologne, 1270 – Toledo, Spain c. 1340, also referred to as ''Ba'al Ha-Turim''). The four-part stru ...

by Rabbi Jacob ben Asher and Shulchan Aruch

The ''Shulhan Arukh'' ( ),, often called "the Code of Jewish Law", is the most widely consulted of the various legal codes in Rabbinic Judaism. It was authored in the city of Safed in what is now Israel by Joseph Karo in 1563 and published in ...

by Rabbi Yosef Karo, draw heavily on : both often quote whole sections verbatim. However, it met initially with much opposition. There were two main reasons for this opposition. First, Maimonides had refrained from adding references to his work for the sake of brevity; second, in the introduction, he gave the impression of wanting to "cut out" study of the Talmud, to arrive at a conclusion in Jewish law, although Maimonides later wrote that this was not his intent. His most forceful opponents were the rabbis of Provence

Provence is a geographical region and historical province of southeastern France, which stretches from the left bank of the lower Rhône to the west to the France–Italy border, Italian border to the east; it is bordered by the Mediterrane ...

(Southern France), and a running critique by Rabbi Abraham ben David

Abraham ben David ( – 27 November 1198), also known by the abbreviation RABaD (for ''Rabbeinu'' Abraham ben David) Ravad or RABaD III, was a Provençal ḥakham, an important commentator on the Talmud, ''Sefer Halachot'' of Isaac Alfasi, an ...

(Raavad III) is printed in virtually all editions of . Nevertheless, Mishneh Torah was recognized as a monumental contribution to the systemized writing of halakha

''Halakha'' ( ; , ), also Romanization of Hebrew, transliterated as ''halacha'', ''halakhah'', and ''halocho'' ( ), is the collective body of Judaism, Jewish religious laws that are derived from the Torah, Written and Oral Torah. ''Halakha'' is ...

. Throughout the centuries, it has been widely studied and its halakhic decisions have weighed heavily in later rulings.

In response to those who would attempt to force followers of Maimonides and his to abide by the rulings of his own Shulchan Aruch

The ''Shulhan Arukh'' ( ),, often called "the Code of Jewish Law", is the most widely consulted of the various legal codes in Rabbinic Judaism. It was authored in the city of Safed in what is now Israel by Joseph Karo in 1563 and published in ...

or other later works, Rabbi Yosef Karo wrote: "Who would dare force communities who follow the Rambam to follow any other decisor f Jewish law early or late? ..The Rambam is the greatest of the decisors, and all the communities of the Land of Israel

The Land of Israel () is the traditional Jewish name for an area of the Southern Levant. Related biblical, religious and historical English terms include the Land of Canaan, the Promised Land, the Holy Land, and Palestine. The definition ...

and the Arabistan and the Maghreb

The Maghreb (; ), also known as the Arab Maghreb () and Northwest Africa, is the western part of the Arab world. The region comprises western and central North Africa, including Algeria, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco, and Tunisia. The Maghreb al ...

practice according to his word, and accepted him as their rabbi."

An oft-cited legal maxim from his pen is: " It is better and more satisfactory to acquit a thousand guilty persons than to put a single innocent one to death." He argued that executing a defendant on anything less than absolute certainty would lead to a slippery slope of decreasing burdens of proof, until defendants would be convicted merely according to the judge's caprice.

Other Judaic and philosophical works

Maimonides composed works of Jewish scholarship, rabbinic law, philosophy, and medical texts. Most of Maimonides' works were written in

Maimonides composed works of Jewish scholarship, rabbinic law, philosophy, and medical texts. Most of Maimonides' works were written in Judeo-Arabic

Judeo-Arabic (; ; ) sometimes referred as Sharh, are a group of different ethnolects within the branches of the Arabic language used by jewish communities. Although Jewish use of Arabic, which predates Islam, has been in some ways distinct ...

. However, the was written in Hebrew. In addition to Mishneh Torah, his Jewish texts were:

* '' Commentary on the Mishna'' (Arabic , translated into Hebrew as ), written in Classical Arabic

Classical Arabic or Quranic Arabic () is the standardized literary form of Arabic used from the 7th century and throughout the Middle Ages, most notably in Umayyad Caliphate, Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphate, Abbasid literary texts such as poetry, e ...

using the Hebrew alphabet

The Hebrew alphabet (, ), known variously by scholars as the Ktav Ashuri, Jewish script, square script and block script, is a unicase, unicameral abjad script used in the writing of the Hebrew language and other Jewish languages, most notably ...

. This was the first full commentary ever written on the entire Mishnah, which took Maimonides seven years to complete. It is considered one of the most important Mishnah commentaries, having enjoyed great popularity both in its Arabic original and its medieval Hebrew translation. The commentary includes three philosophical introductions which were also highly influential:

** The Introduction to the Mishnah deals with the nature of the oral law, the distinction between the prophet and the sage, and the organizational structure of the Mishnah.

** The Introduction to Mishnah Sanhedrin

The Sanhedrin (Hebrew and Middle Aramaic , a loanword from , 'assembly,' 'sitting together,' hence ' assembly' or 'council') was a Jewish legislative and judicial assembly of either 23 or 70 elders, existing at both a local and central level i ...

, chapter ten (), is an eschatological essay that concludes with Maimonides' famous creed ("the thirteen principles of faith").

** The Introduction to Pirkei Avot

Pirkei Avot (; also transliterated as ''Pirqei Avoth'' or ''Pirkei Avos'' or ''Pirke Aboth'', also ''Abhoth''), which translates into English as Chapters of the Fathers, is a compilation of the ethical teachings and maxims from Rabbinic Jewis ...

, popularly called ''The Eight Chapters'', is an ethical treatise.

* (''The Book of Commandments''). In this work, Maimonides lists all the 613 mitzvot

According to Jewish tradition, the Torah contains 613 commandments ().

Although the number 613 is mentioned in the Talmud, its real significance increased in later medieval rabbinic literature, including many works listing or arranged by the . Th ...

traditionally contained in the Torah (Pentateuch). He describes fourteen (roots or principles) to guide his selection.

* (''Letter of Martydom'')

* ''The Guide for the Perplexed

''The Guide for the Perplexed'' (; ; ) is a work of Jewish theology by Maimonides. It seeks to reconcile Aristotelianism with Rabbinical Jewish theology by finding rational explanations for many events in the text.

It was written in Judeo-Arabic ...

'', a philosophical work harmonising and differentiating Aristotle's philosophy and Jewish theology. Written in Judeo-Arabic under the title , and completed between 1186 and 1190. It has been suggested that the title is derived from the Arabic phrase ''dalīl al-mutaḥayyirin'' (guide of the perplexed) a name for God in a work by al-Ghazālī, echoes of whose work can be found elsewhere in Maimonides. The first translation of this work into Hebrew was done by Samuel ibn Tibbon

Samuel ben Judah ibn Tibbon ( – ), more commonly known as Samuel ibn Tibbon (, ), was a Jewish philosopher and doctor who lived and worked in Provence, later part of France. He was born about 1150 in Lunel, Hérault, Lunel (Languedoc), and die ...

in 1204 just prior to Maimonides' death.

* , collected correspondence and responsa

''Responsa'' (plural of Latin , 'answer') comprise a body of written decisions and rulings given by legal scholars in response to questions addressed to them. In the modern era, the term is used to describe decisions and rulings made by scholars i ...

, including a number of public letters (on resurrection and the afterlife

The afterlife or life after death is a purported existence in which the essential part of an individual's Stream of consciousness (psychology), stream of consciousness or Personal identity, identity continues to exist after the death of their ...

, on conversion to other faiths, and —addressed to the oppressed Jewry of Yemen).

* , a fragment of a commentary on the Jerusalem Talmud, identified and published by Saul Lieberman in 1947.

* Commentaries to the Babylonian Talmud

The Talmud (; ) is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and the primary source of Jewish religious law (''halakha'') and Jewish theology. Until the advent of modernity, in nearly all Jewish communities, the Talmud was the centerpiece of Jewi ...

, of which fragments survive.

Medical works

Maimonides' achievements in the medical field are well known, and are cited by many medieval authors. One of his more important medical works is his ''Guide to Good Health'' (), which he composed in Arabic for the Sultan al-Afdal, son ofSaladin

Salah ad-Din Yusuf ibn Ayyub ( – 4 March 1193), commonly known as Saladin, was the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty. Hailing from a Kurdish family, he was the first sultan of both Egypt and Syria. An important figure of the Third Crusade, h ...

, who suffered from depression. The work was translated into Latin, and published in Florence in 1477, becoming the first medical book to appear in print there. While his prescriptions may have become obsolete, "his ideas about preventive medicine, public hygiene, approach to the suffering patient, and the preservation of the health of the soul have not become obsolete." Maimonides wrote ten known medical works in Arabic

Arabic (, , or , ) is a Central Semitic languages, Central Semitic language of the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family spoken primarily in the Arab world. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) assigns lang ...

that have been translated by the Jewish medical ethicist Fred Rosner into contemporary English. Lectures, conferences and research on Maimonides, even recently in the 21st century, have been done at medical universities in Morocco

Morocco, officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It has coastlines on the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to Algeria–Morocc ...

.

*, Suessmann Muntner (ed.), Mossad Harav Kook: Jerusalem 1963 (translated into Hebrew by Moshe Ibn Tibbon) ()

* ''The Art of Cure – Extracts from Galen'' (Barzel, 1992, Vol. 5) is essentially an extract of Galen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus (; September 129 – AD), often Anglicization, anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Ancient Rome, Roman and Greeks, Greek physician, surgeon, and Philosophy, philosopher. Considered to be one o ...

's extensive writings.

* ''Commentary on the Aphorisms of Hippocrates'' (Rosner, 1987, Vol. 2; Hebrew: ) is interspersed with his own views.

* ''Medical Aphorisms of Moses'' (Rosner, 1989, Vol. 3) titled ''Fusul Musa'' in Arabic

Arabic (, , or , ) is a Central Semitic languages, Central Semitic language of the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family spoken primarily in the Arab world. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) assigns lang ...

("Chapters of Moses", Hebrew: ) contains 1500 aphorisms and many medical conditions are described.

* ''Treatise on Hemorrhoids'' (in Rosner, 1984, Vol. 1; Hebrew: ) discusses also digestion and food.

* ''Treatise on Cohabitation'' (in Rosner, 1984, Vol. 1) contains recipes as aphrodisiac

An aphrodisiac is a substance that increases libido, sexual desire, sexual attraction, sexual pleasure, or sexual behavior. These substances range from a variety of plants, spices, and foods to synthetic chemicals. Natural aphrodisiacs, such as ...

s and anti-aphrodisiacs.

* ''Treatise on Asthma'' (Rosner, 1994, Vol. 6) discusses climates and diets and their effect on asthma and emphasizes the need for clean air.

* ''Treatise on Poisons and Their Antidotes'' (in Rosner, 1984, Vol. 1) is an early toxicology

Toxicology is a scientific discipline, overlapping with biology, chemistry, pharmacology, and medicine, that involves the study of the adverse effects of chemical substances on living organisms and the practice of diagnosing and treating ex ...

textbook that remained popular for centuries.

* ''Regimen of Health'' (in Rosner, 1990, Vol. 4; Hebrew: ) is a discourse on healthy living and the mind-body connection.

* ''Discourse on the Explanation of Fits'' advocates healthy living and the avoidance of overabundance.

* ''Glossary of Drug Names'' (Rosner, 1992, Vol. 7) represents a pharmacopeia

A pharmacopoeia, pharmacopeia, or pharmacopoea (or the typographically obsolete rendering, ''pharmacopœia''), meaning "drug-making", in its modern technical sense, is a reference work containing directions for the identification of compound med ...

with 405 paragraphs with the names of drugs in Arabic, Greek, Syrian, Persian, Berber, and Spanish.

''The Oath of Maimonides''

The '' Oath of Maimonides'' is a document about the medical calling and recited as a substitute for the '' Hippocratic Oath''. It is not to be confused with a more lengthy ''Prayer of Maimonides''. These documents may not have been written by Maimonides, but later. The ''Prayer'' appeared first in print in 1793 and has been attributed toMarkus Herz

Markus Herz (; Berlin, 17 January 1747 – Berlin, 19 January 1803) was a German Jewish physician and lecturer on philosophy.

Biography

Born in Berlin to very poor parents, Herz was destined for a mercantile career, and in 1762 went to Köni ...

, a German physician, pupil of Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant (born Emanuel Kant; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German Philosophy, philosopher and one of the central Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works ...

.

Treatise on logic

The ''Treatise on Logic'' (Arabic: ) has been printed 17 times, including editions inLatin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

(1527), German (1805, 1822, 1833, 1828), French (1936) by Moïse Ventura and in 1996 by Rémi Brague, and English (1938) by Israel Efros, and in an abridged Hebrew form. The work illustrates the essentials of Aristotelian logic to be found in the teachings of the great Islamic philosophers such as Avicenna

Ibn Sina ( – 22 June 1037), commonly known in the West as Avicenna ( ), was a preeminent philosopher and physician of the Muslim world, flourishing during the Islamic Golden Age, serving in the courts of various Iranian peoples, Iranian ...

and, above all, Al-Farabi

file:A21-133 grande.webp, thumbnail, 200px, Postage stamp of the USSR, issued on the 1100th anniversary of the birth of Al-Farabi (1975)

Abu Nasr Muhammad al-Farabi (; – 14 December 950–12 January 951), known in the Greek East and Latin West ...

, "the Second Master," the "First Master" being Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

. In his work devoted to the Treatise, Rémi Brague stresses the fact that Al-Farabi is the only philosopher mentioned therein. This indicates a line of conduct for the reader, who must read the text keeping in mind Al-Farabi's works on logic. In the Hebrew versions, the Treatise is called ''The words of Logic'' which describes the bulk of the work. The author explains the technical meaning of the words used by logicians. The Treatise duly inventories the terms used by the logician and indicates what they refer to. The work proceeds rationally through a lexicon of philosophical terms to a summary of higher philosophical topics, in 14 chapters corresponding to Maimonides' birthdate of 14 Nissan. The number 14 recurs in many of Maimonides' works. Each chapter offers a cluster of associated notions. The meaning of the words is explained and illustrated with examples. At the end of each chapter, the author carefully draws up the list of words studied.

Until very recently, it was accepted that Maimonides wrote the ''Treatise on Logic'' in his twenties or even in his teen years. Herbert Davidson has raised questions about Maimonides' authorship of this short work (and of other short works traditionally attributed to Maimonides). He maintains that Maimonides was not the author at all, based on a report of two Arabic-language manuscripts, unavailable to Western investigators in Asia Minor. Rabbi Yosef Kafih maintained that it is by Maimonides and newly translated it to Hebrew (as ) from the Judeo-Arabic.

Philosophy

Through ''The Guide for the Perplexed

''The Guide for the Perplexed'' (; ; ) is a work of Jewish theology by Maimonides. It seeks to reconcile Aristotelianism with Rabbinical Jewish theology by finding rational explanations for many events in the text.

It was written in Judeo-Arabic ...

'' and the philosophical introductions to sections of his commentaries on the Mishna, Maimonides exerted an important influence on the Scholastic philosophers, especially on Albertus Magnus

Albertus Magnus ( 1200 – 15 November 1280), also known as Saint Albert the Great, Albert of Swabia, Albert von Bollstadt, or Albert of Cologne, was a German Dominican friar, philosopher, scientist, and bishop, considered one of the great ...

, Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas ( ; ; – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican Order, Dominican friar and Catholic priest, priest, the foremost Scholasticism, Scholastic thinker, as well as one of the most influential philosophers and theologians in the W ...

and Duns Scotus

John Duns Scotus ( ; , "Duns the Scot"; – 8 November 1308) was a Scottish Catholic priest and Franciscan friar, university professor, philosopher and theologian. He is considered one of the four most important Christian philosopher-t ...

. He was a Jewish Scholastic. Educated more by reading the works of Arab Muslim philosophers than by personal contact with Arabian teachers, he acquired an intimate acquaintance not only with Arab Muslim philosophy, but with the doctrines of Aristotle. Maimonides strove to reconcile Aristotelianism

Aristotelianism ( ) is a philosophical tradition inspired by the work of Aristotle, usually characterized by Prior Analytics, deductive logic and an Posterior Analytics, analytic inductive method in the study of natural philosophy and metaphysics ...

and science with the teachings of the Torah

The Torah ( , "Instruction", "Teaching" or "Law") is the compilation of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, namely the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. The Torah is also known as the Pentateuch () ...

. In his ''Guide for the Perplexed'', he often explains the function and purpose of the statutory provisions contained in the Torah against the backdrop of the historical conditions. The book was highly controversial in its day, and was banned by French rabbis, who burnt copies of the work in Montpellier

Montpellier (; ) is a city in southern France near the Mediterranean Sea. One of the largest urban centres in the region of Occitania (administrative region), Occitania, Montpellier is the prefecture of the Departments of France, department of ...

.

Thirteen principles of faith

In his commentary on the Mishnah ( Tractate Sanhedrin, chapter 10), Maimonides formulates his "13 principles of faith"; and that these principles summarized what he viewed as the required beliefs of Judaism: # Theexistence of God

The existence of God is a subject of debate in the philosophy of religion and theology. A wide variety of arguments for and against the existence of God (with the same or similar arguments also generally being used when talking about the exis ...

.

# God's unity and indivisibility into elements.

# God's spirituality

The meaning of ''spirituality'' has developed and expanded over time, and various meanings can be found alongside each other. Traditionally, spirituality referred to a religious process of re-formation which "aims to recover the original shape o ...

and incorporeality.

# God's eternity

Eternity, in common parlance, is an Infinity, infinite amount of time that never ends or the quality, condition or fact of being everlasting or eternal. Classical philosophy, however, defines eternity as what is timeless or exists outside tim ...

.

# God alone should be the object of worship

Worship is an act of religious devotion usually directed towards a deity or God. For many, worship is not about an emotion, it is more about a recognition of a God. An act of worship may be performed individually, in an informal or formal group, ...

.

# Revelation

Revelation, or divine revelation, is the disclosing of some form of Religious views on truth, truth or Knowledge#Religion, knowledge through communication with a deity (god) or other supernatural entity or entities in the view of religion and t ...

through God's prophet

In religion, a prophet or prophetess is an individual who is regarded as being in contact with a divinity, divine being and is said to speak on behalf of that being, serving as an intermediary with humanity by delivering messages or teachings ...

s.

# The preeminence of Moses

In Abrahamic religions, Moses was the Hebrews, Hebrew prophet who led the Israelites out of slavery in the The Exodus, Exodus from ancient Egypt, Egypt. He is considered the most important Prophets in Judaism, prophet in Judaism and Samaritani ...

among the prophets.

# That the entire Torah (both the Written and Oral law) are of Divine origin and were dictated to Moses by God on Mt. Sinai.

# The Torah

The Torah ( , "Instruction", "Teaching" or "Law") is the compilation of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, namely the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. The Torah is also known as the Pentateuch () ...

given by Moses is permanent and will not be replaced or changed.

# God's awareness of all human actions and thoughts.

# Reward of righteousness and punishment of evil.

# The coming of the Jewish Messiah.

# The resurrection of the dead

General resurrection or universal resurrection is the belief in a resurrection of the dead, or resurrection from the dead ( Koine: , ''anastasis onnekron''; literally: "standing up again of the dead") by which most or all people who have died ...

.

Maimonides is said to have compiled the principles from various Talmudic sources. These principles were controversial when first proposed, evoking criticism by Rabbis Hasdai Crescas and Joseph Albo, and were effectively ignored by much of the Jewish community for the next few centuries. However, these principles have become widely held and are considered to be the cardinal principles of faith for Orthodox Jews

Orthodox Judaism is a collective term for the traditionalist branches of contemporary Judaism. Theologically, it is chiefly defined by regarding the Torah, both Written and Oral, as literally revealed by God on Mount Sinai and faithfully tr ...

. Two poetic restatements of these principles ( and ) eventually became canonized in many editions of the Siddur

A siddur ( ''sīddūr'', ; plural siddurim ) is a Jewish prayer book containing a set order of daily prayers. The word comes from the Hebrew root , meaning 'order.'

Other terms for prayer books are ''tefillot'' () among Sephardi Jews, ''tef ...

(Jewish prayer book).

The omission of a list of these principles as such within his later works, the and ''The Guide for the Perplexed

''The Guide for the Perplexed'' (; ; ) is a work of Jewish theology by Maimonides. It seeks to reconcile Aristotelianism with Rabbinical Jewish theology by finding rational explanations for many events in the text.

It was written in Judeo-Arabic ...

'', has led some to suggest that either he retracted his earlier position, or that these principles are descriptive rather than prescriptive.

Theology

Maimonides equated the God of Abraham to what philosophers refer to as the Necessary Being. God is unique in the universe, and the Torah commands that one

Maimonides equated the God of Abraham to what philosophers refer to as the Necessary Being. God is unique in the universe, and the Torah commands that one love

Love is a feeling of strong attraction and emotional attachment (psychology), attachment to a person, animal, or thing. It is expressed in many forms, encompassing a range of strong and positive emotional and mental states, from the most su ...

and fear

Fear is an unpleasant emotion that arises in response to perception, perceived dangers or threats. Fear causes physiological and psychological changes. It may produce behavioral reactions such as mounting an aggressive response or fleeing the ...

God ( Deut 10:12) on account of that uniqueness. To Maimonides, this meant that one ought to contemplate God's works and to marvel at the order and wisdom that went into their creation. When one does this, one inevitably comes to love God and to sense how insignificant one is in comparison to God. This is the basis of the Torah.

The principle that inspired his philosophical activity was identical to a fundamental tenet of scholasticism

Scholasticism was a medieval European philosophical movement or methodology that was the predominant education in Europe from about 1100 to 1700. It is known for employing logically precise analyses and reconciling classical philosophy and Ca ...

: there can be no contradiction between the truths which God has revealed and the findings of the human mind in science and philosophy. Maimonides primarily relied upon the science of Aristotle and the teachings of the Talmud, commonly claiming to find a basis for the latter in the former.

Maimonides' admiration for the Neoplatonic commentators led him to doctrines which the later Scholastics did not accept. For instance, Maimonides was an adherent of apophatic theology

Apophatic theology, also known as negative theology, is a form of theology, theological thinking and religious practice which attempts to Problem of religious language, approach God, the Divine, by negation, to speak only in terms of what may no ...

. In this theology, one attempts to describe God through negative attributes. For example, one should not say that God exists in the usual sense of the term; it can be said that God is not non-existent. One should not say that "God is wise"; but it can be said that "God is not ignorant," i.e., in some way, God has some properties of knowledge. One should not say that "God is One," but it can be stated that "there is no multiplicity in God's being." In brief, the attempt is to gain and express knowledge of God by describing what God is not, rather than by describing what God "is."Robinson, George"Maimonides' Conception of God/"

''My Jewish Learning''. 30 April 2018. Maimonides argued adamantly that God is not corporeal. This was central to his thinking about the sin of

idolatry

Idolatry is the worship of an idol as though it were a deity. In Abrahamic religions (namely Judaism, Samaritanism, Christianity, Islam, and the Baháʼí Faith) idolatry connotes the worship of something or someone other than the Abrahamic ...

. Maimonides insisted that all of the anthropomorphic phrases pertaining to God in sacred texts are to be interpreted metaphor

A metaphor is a figure of speech that, for rhetorical effect, directly refers to one thing by mentioning another. It may provide, or obscure, clarity or identify hidden similarities between two different ideas. Metaphors are usually meant to cr ...

ically. A related tenet of Maimonidean theology is the notion that the commandments, especially those pertaining to sacrifices, are intended to help wean the Israelites away from idolatry.Reuven Chaim Klein,Weaning Away from Idolatry: Maimonides on the Purpose of Ritual Sacrifices

", ''Religions'' 12(5), 363. Maimonides also argued that God embodied

reason

Reason is the capacity of consciously applying logic by drawing valid conclusions from new or existing information, with the aim of seeking the truth. It is associated with such characteristically human activities as philosophy, religion, scien ...

, intellect

Intellect is a faculty of the human mind that enables reasoning, abstraction, conceptualization, and judgment. It enables the discernment of truth and falsehood, as well as higher-order thinking beyond immediate perception. Intellect is dis ...

, science

Science is a systematic discipline that builds and organises knowledge in the form of testable hypotheses and predictions about the universe. Modern science is typically divided into twoor threemajor branches: the natural sciences, which stu ...

, and nature

Nature is an inherent character or constitution, particularly of the Ecosphere (planetary), ecosphere or the universe as a whole. In this general sense nature refers to the Scientific law, laws, elements and phenomenon, phenomena of the physic ...

, and was omnipotent

Omnipotence is the property of possessing maximal power. Monotheistic religions generally attribute omnipotence only to the deity of their faith. In the monotheistic religious philosophy of Abrahamic religions, omnipotence is often listed as ...

and indescribable. He said that science, the growth of scientific fields, and discovery of the unknown by comprehension of nature was a way to appreciate God.

Character development

Maimonides taught about the developing of one'smoral character

Moral character or character (derived from ) is an analysis of an individual's steady Morality, moral qualities. The concept of ''character'' can express a variety of attributes, including the presence or lack of virtues such as empathy, courag ...

. Although his life predated the modern concept of a personality

Personality is any person's collection of interrelated behavioral, cognitive, and emotional patterns that comprise a person’s unique adjustment to life. These interrelated patterns are relatively stable, but can change over long time per ...

, Maimonides believed that each person has an innate disposition along an ethical and emotional spectrum. Although one's disposition is often determined by factors outside of one's control, human beings have free will

Free will is generally understood as the capacity or ability of people to (a) choice, choose between different possible courses of Action (philosophy), action, (b) exercise control over their actions in a way that is necessary for moral respon ...

to choose to behave in ways that build character. He wrote, "One is obligated to conduct his affairs with others in a gentle and pleasing manner." Maimonides advised that those with antisocial character traits should identify those traits and then make a conscious effort to behave in the opposite way. For example, an arrogant person should practice humility. If the circumstances of one's environment are such that it is impossible to behave ethically, one must move to a new location.

Prophecy

Maimonides agreed with "the Philosopher" (Aristotle) that the use of logic is the "right" way of thinking. He claimed that in order to understand how to know God, every human being must, by study, and meditation attain the degree of perfection required to reach theprophet

In religion, a prophet or prophetess is an individual who is regarded as being in contact with a divinity, divine being and is said to speak on behalf of that being, serving as an intermediary with humanity by delivering messages or teachings ...

ic state. Despite his rationalistic approach, he does not explicitly reject the previous ideas (as portrayed, for example, by Rabbi Yehuda Halevi in his ) that in order to become a prophet, God must intervene. Maimonides teaches that prophecy is the highest purpose of the most learned and refined individuals.

The problem of evil

Maimonides wrote ontheodicy

In the philosophy of religion, a theodicy (; meaning 'vindication of God', from Ancient Greek θεός ''theos'', "god" and δίκη ''dikē'', "justice") is an argument that attempts to resolve the problem of evil that arises when all powe ...

(the philosophical attempt to reconcile the existence of a God with the existence of evil). He took the premise that an omnipotent and good God exists. In ''The Guide for the Perplexed'', Maimonides writes that all the evil that exists within human beings stems from their individual attributes, while all good comes from a universally shared humanity (Guide 3:8). He says that there are people who are guided by higher purpose, and there are those who are guided by physicality and must strive to find the higher purpose with which to guide their actions.

To justify the existence of evil, assuming God is both omnipotent and omnibenevolent, Maimonides postulates that one who created something by causing its opposite not to exist is not the same as creating something that exists; so evil is merely the absence of good. God did not create evil, rather God created good, and evil exists where good is absent (Guide 3:10). Therefore, all good is divine invention, and evil both is not and comes secondarily.

Maimonides contests the common view that evil outweighs good in the world. He says that if one were to examine existence only in terms of humanity, then that person may observe evil to dominate good, but if one looks at the whole of the universe, then he sees good is significantly more common than evil (Guide 3:12). Man, he reasons, is too insignificant a figure in God's myriad works to be their primary characterizing force, and so when people see mostly evil in their lives, they are not taking into account the extent of positive Creation outside of themselves.

Maimonides believes that there are three types of evil in the world: evil caused by nature, evil that people bring upon others, and evil man brings upon himself (Guide 3:12). The first type of evil Maimonides states is the rarest form, but arguably of the most necessary—the balance of life and death in both the human and animal worlds itself, he recognizes, is essential to God's plan. Maimonides writes that the second type of evil is relatively rare, and that humanity brings it upon itself. The third type of evil humans bring upon themselves and is the source of most of the ills of the world. These are the result of people's falling victim to their physical desires. To prevent the majority of evil which stems from harm one does to oneself, one must learn how to respond to one's bodily urges.

Skepticism of astrology

Maimonides answered an inquiry concerning astrology, addressed to him fromMarseille

Marseille (; ; see #Name, below) is a city in southern France, the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Bouches-du-Rhône and of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur Regions of France, region. Situated in the ...

. He responded that man should believe only what can be supported either by rational proof, by the evidence of the senses, or by trustworthy authority. He affirms that he had studied astrology, and that it does not deserve to be described as a science. He ridicules the concept that the fate of a man could be dependent upon the constellations; he argues that such a theory would rob life of purpose, and would make man a slave of destiny.

Unlike some of his contemporaries, Maimonides did not believe that Greek knowledge had originated with the Jews originally, but he does believe that the sages and Solomon

Solomon (), also called Jedidiah, was the fourth monarch of the Kingdom of Israel (united monarchy), Kingdom of Israel and Judah, according to the Hebrew Bible. The successor of his father David, he is described as having been the penultimate ...

knew science and philosophy, however he does not believe those books have survived down to his time. He notes that rabbinical knowledge of mathematics was imperfect because it was learned from contemporary men of science, and not divinely inspired prophecy.

True beliefs versus necessary beliefs

In ''The Guide for the Perplexed'' Book III, Chapter 28, Maimonides draws a distinction between "true beliefs," which were beliefs about God that produced intellectual perfection, and "necessary beliefs," which were conducive to improving social order. Maimonides places anthropomorphic personification statements about God in the latter class. He uses as an example the notion that God becomes "angry" with people who do wrong. In the view of Maimonides (taken fromAvicenna

Ibn Sina ( – 22 June 1037), commonly known in the West as Avicenna ( ), was a preeminent philosopher and physician of the Muslim world, flourishing during the Islamic Golden Age, serving in the courts of various Iranian peoples, Iranian ...

), God does not become angry with people, as God has no human passions; but it is important for them to believe God does, so that they desist from doing wrong.

Righteousness and charity

Maimonides conceived of an eight-level hierarchy oftzedakah

''Tzedakah'' ( ''ṣədāqā'', ) is a Hebrew word meaning "righteousness", but commonly used to signify ''charity''. This concept of "charity" differs from the modern Western understanding of "charity". The latter is typically understood as ...

, where the highest form is to give a gift, loan, or partnership that will result in the recipient becoming self-sufficient instead of living upon others. In his view, the lowest form of ''tzedakah'' is to give begrudgingly. The eight levels are:

# Giving begrudgingly

# Giving less than you should, but giving it cheerfully

# Giving after being asked

# Giving before being asked

# Giving when you do not know the recipient's identity, but the recipient knows your identity

# Giving when you know the recipient's identity, but the recipient doesn't know your identity

# Giving when neither party knows the other's identity

# Enabling the recipient to become self-reliant

Eschatology

The Messianic era