Madeleine Hamilton Smith on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Madeleine Hamilton Smith (29 March 1835 – 12 April 1928) was a 19th-century

Madeleine Hamilton Smith (29 March 1835 – 12 April 1928) was a 19th-century

Smith was the first child (of five) of an upper-middle-class family in

Smith was the first child (of five) of an upper-middle-class family in

At trial, Smith was defended by advocate John Inglis, the future Lord Glencorse. Toxicological evidence, confirming that the victim had died of arsenic poisoning, was given by

At trial, Smith was defended by advocate John Inglis, the future Lord Glencorse. Toxicological evidence, confirming that the victim had died of arsenic poisoning, was given by

The Madeleine Smith Story

at the

Madeleine Wardle in later lifeContemporary description of the accused; testimonyContemporary description of the accused; correspondence between her and the deceased

{{DEFAULTSORT:Smith, Madeleine 1835 births Anglo-Scots People associated with Glasgow Scottish socialites Trials in Scotland 1928 deaths Place of birth missing British people acquitted of murder Members of the Fabian Society

Madeleine Hamilton Smith (29 March 1835 – 12 April 1928) was a 19th-century

Madeleine Hamilton Smith (29 March 1835 – 12 April 1928) was a 19th-century Glasgow

Glasgow is the Cities of Scotland, most populous city in Scotland, located on the banks of the River Clyde in Strathclyde, west central Scotland. It is the List of cities in the United Kingdom, third-most-populous city in the United Kingdom ...

socialite

A socialite is a person, typically a woman from a wealthy or aristocratic background, who is prominent in high society. A socialite generally spends a significant amount of time attending various fashionable social gatherings, instead of having ...

who was the accused in a sensational murder trial in Scotland in 1857.

Background

Smith was the first child (of five) of an upper-middle-class family in

Smith was the first child (of five) of an upper-middle-class family in Glasgow

Glasgow is the Cities of Scotland, most populous city in Scotland, located on the banks of the River Clyde in Strathclyde, west central Scotland. It is the List of cities in the United Kingdom, third-most-populous city in the United Kingdom ...

; her father, James Smith (1808–1863), was a wealthy architect, and her mother, Elizabeth, was the daughter of leading neo-classical architect David Hamilton. She was born at the family home 81 Wellington Place in Glasgow.

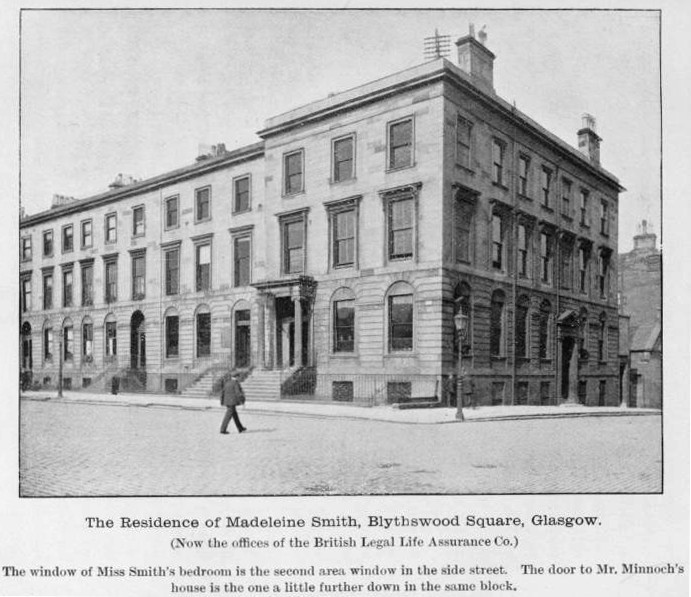

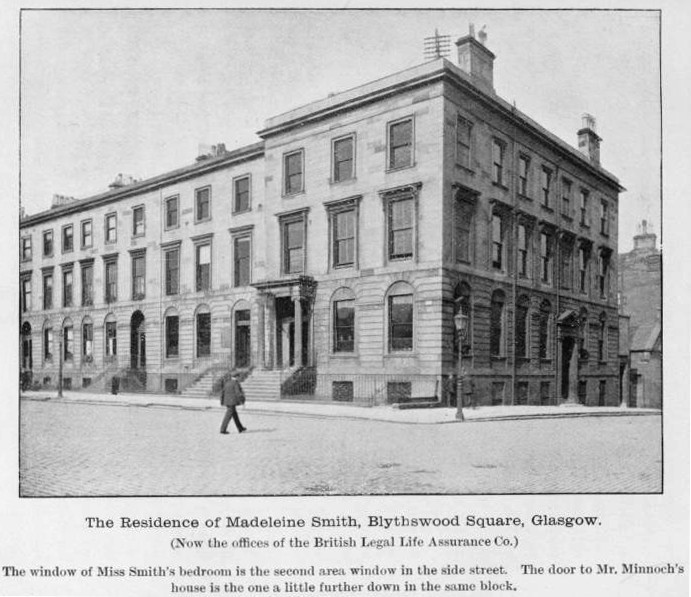

In 1855 the family moved from India Street to 7 Blythswood Square

Blythswood Square is the Georgian square on Blythswood Hill in the heart of the City of Glasgow, Scotland. The square is part of the 'Magnificent New Town of Blythswood' built in the 1800s on the rising empty ground west of a very new Buch ...

, Glasgow, living in the lower half of a house owned by her maternal uncle, David Hamilton, a yarn merchant. The house stands at the crown of the major development led by William Harley

William Harley (1767–1830) was a Scottish textile manufacturer and entrepreneur who is known for his early contributions to the city of Glasgow, including the development of the New Town of Blythswood, covering Blythswood Hill, and pioneering ...

on Blythswood Hill

Blythswood Hill, crowned by Blythswood Square, is an area of central Glasgow, Scotland. Its grid of streets extend from the length of the west side of Buchanan Street to Gordon Street and Bothwell Street, and to Charing Cross, Sauchiehall Street ...

, and they also had a country property, "Rowaleyn", near Helensburgh

Helensburgh ( ; ) is a town on the north side of the Firth of Clyde in Scotland, situated at the mouth of the Gareloch. Historically in Dunbartonshire, it became part of Argyll and Bute following local government reorganisation in 1996.

Histo ...

.

Smith broke the strict Victorian

Victorian or Victorians may refer to:

19th century

* Victorian era, British history during Queen Victoria's 19th-century reign

** Victorian architecture

** Victorian house

** Victorian decorative arts

** Victorian fashion

** Victorian literatur ...

conventions of the time when, as a young woman in early 1855, she began a secret love affair with Pierre Emile L'Angelier, some ten years her senior, an apprentice nurseryman who originally came from the Channel Islands

The Channel Islands are an archipelago in the English Channel, off the French coast of Normandy. They are divided into two Crown Dependencies: the Jersey, Bailiwick of Jersey, which is the largest of the islands; and the Bailiwick of Guernsey, ...

. He worked as a packing clerk in a warehouse at 10 Bothwell Street nearby.

The pair would meet late at night, at Smith's bedroom window and also engaged in voluminous correspondence. During one of their infrequent meetings alone, she lost her virginity to L'Angelier.

Smith's parents, unaware of the affair with L'Angelier (whom Smith had promised to marry), found a suitable fiancé for her within the Glasgow upper-middle class, William Harper Minnoch.

Smith attempted to break her connection with L'Angelier and, in February 1857, asked him to return the letters she had written to him. Instead, L'Angelier threatened to use the letters to expose her and force her to marry him. She was soon observed in a druggist's office, ordering arsenic

Arsenic is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol As and atomic number 33. It is a metalloid and one of the pnictogens, and therefore shares many properties with its group 15 neighbors phosphorus and antimony. Arsenic is not ...

, which she signed for as M. H. Smith.

Early on the morning of 23 March 1857, L'Angelier died from arsenic poisoning. He is buried in the Ramshorn Cemetery

The Ramshorn Cemetery is a cemetery in Scotland and one of Glasgow's older burial grounds, located within the Merchant City district, and along with its The Ramshorn, accompanying church, is owned by the University of Strathclyde. It has had v ...

on Ingram Street in Glasgow.

After his death, Smith's numerous letters were found in the house where he lodged, and she was arrested and charged with his murder.

Trial

At trial, Smith was defended by advocate John Inglis, the future Lord Glencorse. Toxicological evidence, confirming that the victim had died of arsenic poisoning, was given by

At trial, Smith was defended by advocate John Inglis, the future Lord Glencorse. Toxicological evidence, confirming that the victim had died of arsenic poisoning, was given by Andrew Douglas Maclagan

Sir Andrew Douglas Maclagan PRSE FRCPE FRCSE FCS FRSSA (17 April 1812, in Ayr – 5 April 1900, in Edinburgh) was a Scottish surgeon, toxicologist and scholar of medical jurisprudence. He served as president of 5 learned societies: the Royal ...

.

In the trial the two most positive elements in her defence were the two druggists both testifying that they coloured their arsenic to avoid accident (and the autopsy having not found this), and L'Angelier's valet testifying that L'Angelier had considered suicide at least once. There was therefore a strong suggestion of suicide.

Although the circumstantial evidence pointed towards her guilt (Smith had made purchases of arsenic in the weeks leading up to L'Angelier's death, and had a clear motive) the jury returned one verdict of not guilty on the first count and a verdict of "not proven

Not proven (, ) is a verdict available to a court of law in Scotland. Under Scots law, a criminal trial may end in one of three verdicts, one of conviction ("guilty") and two of acquittal ("not proven" and "not guilty").The Scottish criminal jur ...

" on the second count.

Crucial to the case was the chronology of certain letters from Smith to L'Angelier, and as the letters themselves were undated, the case hinged to some extent on the envelopes. One letter in particular depended on the correct interpretation of the date of the postmark, which was unfortunately illegible, and attracted some caustic comments from the judge; but the vast majority of these postmarks were quite clearly struck. It transpired that when the police searched L'Angelier's room, many of Smith's letters were found without their envelopes and were then hurriedly collected and stuck into whichever envelopes came to hand.

Later life

Following the scandal her family were forced to quit their Glasgow home and their country villa Rowaleyn inRhu

Rhu (; ) is a village and historic parish on the east shore of the Gare Loch in Argyll and Bute, Scotland.

The traditional spelling of its name was ''Row'', but it was changed in the 1920s so that outsiders would pronounce it correctly. The ...

and moved to Bridge of Allan

Bridge of Allan (, ), also known colloquially as ''Bofa'', is a former spa town in the Stirling (council area), Stirling council area in Scotland, just north of the city of Stirling.

Overlooked by the National Wallace Monument, it lies on th ...

in central Scotland. They moved again in 1860 to Old Polmont. Her father died in Polmont in 1863 aged 55, broken by the whole affair.

On 4 July 1861, she married an artist named George Wardle, William Morris

William Morris (24 March 1834 – 3 October 1896) was an English textile designer, poet, artist, writer, and socialist activist associated with the British Arts and Crafts movement. He was a major contributor to the revival of traditiona ...

's business manager. They had one son (Thomas, born 1864) and one daughter (Mary, called "Kitten", born 1863). For a time, she became involved with the Fabian Society

The Fabian Society () is a History of the socialist movement in the United Kingdom, British socialist organisation whose purpose is to advance the principles of social democracy and democratic socialism via gradualist and reformist effort in ...

in London, and was an enthusiastic organiser. Because she was known by her new married name, not everyone knew who she was, but a few did.Jack House, ''Square Mile of Murder''

After many years of marriage, she and her husband separated in 1889 and Madeleine moved to New York City. Around 1916, then 75, she married 49-year-old William A. Sheehy and this marriage lasted until his death in 1926.

She was buried in New York at Mount Hope Cemetery in Hastings-on-Hudson

Hastings-on-Hudson is a village in Westchester County located in the southwestern part of the town of Greenburgh in the state of New York, United States. It is a suburb of New York City, located approximately north of midtown Manhattan, and i ...

under the name of Lena Sheehy on 19 April 1928.

Later theories

As in the case ofLizzie Borden

Lizzie Andrew Borden (July 19, 1860 – June 1, 1927) was an American woman who was Trial, tried and Acquittal, acquitted of the August 4, 1892 axe murders of her Patricide, father and stepmother in Fall River, Massachusetts. No one else was c ...

, scholars and amateur criminologist

Criminology (from Latin , 'accusation', and Ancient Greek , ''-logia'', from λόγος ''logos'', 'word, reason') is the interdisciplinary study of crime and deviant behaviour. Criminology is a multidisciplinary field in both the behaviou ...

s have spent decades going over the details of the case.

Most modern scholars believe that Smith committed the crime and the only thing that saved her from a guilty verdict and a death sentence was that no eyewitness could prove that Smith and L'Angelier had met in the weeks before his death.

After the trial, ''The Scotsman

''The Scotsman'' is a Scottish compact (newspaper), compact newspaper and daily news website headquartered in Edinburgh. First established as a radical political paper in 1817, it began daily publication in 1855 and remained a broadsheet until ...

'' ran a small article stating that a witness had come forward claiming that a young male and female were seen outside Smith's house on the night of L'Angelier's death. However, the trial was already in progress, and the witness could not be questioned during it.

Dramatisations

Smith's story was the basis for several plays and the distinguishedDavid Lean

Sir David Lean (25 March 190816 April 1991) was an English film director, producer, screenwriter, and editor, widely considered one of the most important figures of Cinema of the United Kingdom, British cinema. He directed the large-scale epi ...

film '' Madeleine'' (1950), starring Ann Todd

Dorothy Ann Todd (24 January 1907 – 6 May 1993) was an English film, television and stage actress who achieved international fame when she starred in '' The Seventh Veil'' (1945). From 1949 to 1957 she was married to David Lean who directed ...

, Ivan Desny

Ivan Desny (born Ivan Nikolaevich Desnitsky; , 28 December 1922 – 13 April 2002) was a French actor of Russian Chinese origin. He had a lengthy career in French and German cinema, appearing in over 200 film and television roles over 50 year ...

and Leslie Banks

Leslie James Banks Commander of the Order of the British Empire, CBE (9 June 1890 – 21 April 1952) was an English stage and screen actor, director and producer, now best remembered for playing gruff, menacing characters in black-and-white fi ...

. Todd had previously played Smith in the 1944 West End play '' The Rest is Silence'' by Harold Purcell

Harold Purcell (1907–1977) was a British writer and musical lyricist who frequently collaborated with Harry Parr-Davies. They co-wrote the book for the 1952 Anna Neagle musical ''The Glorious Days''.Wearing p.216

Selected works

* '' Magyar Me ...

. A television play

A television play is a television programming genre which is a drama performance broadcast from a multi-camera television studio, usually live in the early days of television but later recorded to tape. This is in contrast to a television movi ...

based upon the case, ''Killer in Close-Up

''Killer in Close-Up'' was a blanket title covering four live television drama plays produced by the Australian Broadcasting Commission in 1957 and 1958. It could be seen as the first anthology series produced for Australian television.

Productio ...

: The Trial Of Madeleine Smith'', written by George F. Kerr

George F. Kerr (15 April 1918 – 29 October 1996) was an English writer best known for his work in TV. He worked for eight years in British TV as a writer and script editor.

He moved to Australia in 1957 and wrote several early TV dramas as wel ...

, was also produced by Sydney

Sydney is the capital city of the States and territories of Australia, state of New South Wales and the List of cities in Australia by population, most populous city in Australia. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Syd ...

television station ABN-2

ABC Television in New South Wales comprises national and local programming on the ABC television network in the Australian state of New South Wales, headquartered in Sydney.

ABN or ABN-2 was the historic call sign of the Australian Broadcasti ...

, broadcast on 13 August 1958. Jack House

John House (16 May 1906 – 11 April 1991) was a prolific and popular Scottish writer and broadcaster, with a significant attachment to the Glasgow, City of Glasgow.

Early life

East end

House was born in Tollcross, Glasgow, Tollcross, then in ...

's book ''Square Mile of Murder

The Square Mile of Murder relates to an area of west-central Glasgow, Scotland. The term was first coined by the Scottish journalist and author Jack House, whose 1961 book of the same name was based on the fact that four of Scotland's most infamou ...

'' (1961), which contains a section on Smith, formed the basis for a BBC

The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is a British public service broadcaster headquartered at Broadcasting House in London, England. Originally established in 1922 as the British Broadcasting Company, it evolved into its current sta ...

television version in 1980. In the Granada Television series The LadyKillers Smith was played by Elizabeth Richardson. In 1996, the fifth series of ''In Suspicious Circumstances

''In Suspicious Circumstances'' is a British true crime drama television series produced by Granada Television for ITV between 3 June 1991 and 11 October 1996. Re-enactments of historical crimes were introduced by Edward Woodward.

Granada's Hea ...

'' had an episode titled ''Dearest Pet'' that was a dramatisation of the Smith case. Geraldine O'Rawe

Geraldine O'Rawe (born 4 March 1971) is an Irish actress.Wilkie Collins

William Wilkie Collins (8 January 1824 – 23 September 1889) was an English novelist and playwright known especially for ''The Woman in White (novel), The Woman in White'' (1860), a mystery novel and early sensation novel, and for ''The Moonsto ...

' novel '' The Law and the Lady'' (1875), though the only main similar features were the problem of the Scottish "Not Proven" verdict and arsenic poisoning

Arsenic poisoning (or arsenicosis) is a medical condition that occurs due to elevated levels of arsenic in the body. If arsenic poisoning occurs over a brief period of time, symptoms may include vomiting, abdominal pain, encephalopathy, and water ...

as a means for murder.

Katharine Cornell

Katharine Cornell (February 16, 1893 – June 9, 1974) was an American stage actress, writer, theater owner and producer. She was born in Berlin to American parents and raised in Buffalo, New York.

Dubbed "The First Lady of the Theatre" by cri ...

portrayed Smith in the play ''Dishonored Lady.'' TCM gives the date of the play as 1928; the Internet Broadway Database has it opening on Broadway in 1930. In the early 1930s, MGM starred Joan Crawford

Joan Crawford (born Lucille Fay LeSueur; March 23, 190? was an American actress. She started her career as a dancer in traveling theatrical companies before debuting on Broadway theatre, Broadway. Crawford was signed to a motion-picture cont ...

, Nils Asther

Nils Anton Alfhild Asther (17 January 1897 – 19 October 1981)Swedi ...

and Robert Montgomery in a film called ''Letty Lynton

''Letty Lynton'' is a 1932 American pre-Code drama film starring Joan Crawford, Robert Montgomery and Nils Asther. The film was directed by Clarence Brown and based on the 1931 novel of the same name by Marie Adelaide Belloc Lowndes; the n ...

'', which was based on a 1931 novel of the same title by Marie Adelaide Belloc Lowndes

Marie Adelaide Elizabeth Rayner Lowndes (née Belloc; 5 August 1868 – 14 November 1947), who wrote as Marie Belloc Lowndes, was a prolific English novelist, and sister of author Hilaire Belloc.

Active from 1898 until her death, she had a re ...

. This film closely follows Madeleine's story, except that Crawford's character is never charged and, in an example of pre-code Hollywood

Pre-Code Hollywood was an era in the Cinema of the United States, American film industry that occurred between the widespread adoption of sound in film in the late 1920s and the enforcement of the Motion Picture Production Code censorship gui ...

, gets away with murder. The film is not presently available due to a suit filed shortly after the film's release in 1932. The suit successfully claimed that the film script bears too close a resemblance to the script of the play, ''Dishonored Lady''. In 1947, the play was adapted into a film of the same name starring Hedy Lamarr

Hedy Lamarr (; born Hedwig Eva Maria Kiesler; November 9, 1914 January 19, 2000) was an Austrian-born American actress and inventor. After a brief early film career in Czechoslovakia, including the controversial erotic romantic drama '' Ecstasy ...

.'

The case was again dramatised in 1952 for Mutual Radio in an episode of ''The Black Museum Black Museum may refer to:

* the Black Museum at New Scotland Yard, now known as the Crime Museum

* Black Museum (Southwark), a museum of engineering components gathered by David Kirkaldy

* ''Black Museum'' (Black Mirror), an episode of Black Mir ...

'' titled "The Small White Boxes".

Other novels based on the case include ''The House in Queen Anne's Square'' (1920) by William Darling Lyell, ''Lovers All Untrue'' (1970) by Norah Lofts

Norah Ethel Lofts (née Robinson; 27 August 190410 September 1983) was a 20th-century British writer. She also wrote under the pen names Peter Curtis and Juliet Astley. She wrote more than fifty books specialising in historical fiction, but she ...

, and ''Alas, for Her That Met Me!'' (1976) by Mary Ann Ashe (pseudonym of Christianna Brand

Mary Christianna Lewis (née Milne; 17 December 1907 – 11 March 1988), known professionally as Christianna Brand, was a British crime writer and children's literature, children's author born in British Malaya (now Malaysia).

Biography

...

). Alanna Knight's ''Murder in Paradise'' (2008) includes Smith, William Morris and George Wardle as peripheral characters, including a story of how Madeleine met George.

From 1976 to 1989 Smith was one of the figures in the Chamber of Horrors section in the Edinburgh Wax Museum on the Royal Mile

The Royal Mile () is the nickname of a series of streets forming the main thoroughfare of the Old Town, Edinburgh, Old Town of Edinburgh, Scotland. The term originated in the early 20th century and has since entered popular usage.

The Royal ...

.

The Madeleine Smith case was partly dramatised with actors reading her letters and a draft of a letter by Pierre Emile L'Angelier on an episode of the 2022 BBC Radio

BBC Radio is an operational business division and service of the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) which has operated in the United Kingdom under the terms of a royal charter since 1927. The service provides national radio stations cove ...

podcast series ''Lady Killers with Lucy Worsley

Dr. Lucy Worsley (born 18 December 1973) is an English historian, author, curator and television presenter. She was the joint chief curator at Historic Royal Palaces but is best known amongst UK television viewers as a presenter of BBC Televi ...

''.

References

Sources

* Campbell, Jimmy Powdrell. ''Rewriting The Madeleine Smith Story''. 2007 * Diamond, Michael (2003) ''Victorian Sensation'' London: Anthem. . pp. 172–176 * MacGowan, Douglas. ''The Strange Affair of Madeleine Smith: Victorian Scotland's Trial of the Century''. (Mercat Press, 2007). . * MacGowan, Douglas. ''Murder in Victorian Scotland: The Trial of Madeleine Smith''. (1999) * House, Jack (1961) ''Square Mile of Murder''. Edinburgh: W. & R. Chambers * Mackay, James. ''Scotland's Post'' (2000) GlasgowFurther reading

* Geary, Rick (2006) "A Treasury of Victorian Murder: The Case of Madeleine Smith". New York: NBM. * Gordon, Eleanor & Nair, Gwyneth (2009) ''Murder and morality in Victorian Britain: The Story of Madeleine Smith''. Manchester: Manchester University Press * Hartman, M. S. (1979) "Murder for respectability : The case of Madeleine Smith". ''Victorian Studies'', 16:4, 381–400. Publisher: Indiana University Press. * Morland, Nigel (US: 1988) "That Nice Miss Smith" * ''Glasgow's Blythswood'' by Graeme Smith, 2021 https://blythswoodsmith.co.uk/External links

*The Madeleine Smith Story

at the

Crime Library

Crime Library is a website documenting major crimes, criminals, trials, forensics, and criminal profiling from books. It was founded in 1998 and was most recently owned by truTV, a cable TV network that is part of Time Warner's Turner Broadcast ...

Madeleine Wardle in later life

{{DEFAULTSORT:Smith, Madeleine 1835 births Anglo-Scots People associated with Glasgow Scottish socialites Trials in Scotland 1928 deaths Place of birth missing British people acquitted of murder Members of the Fabian Society