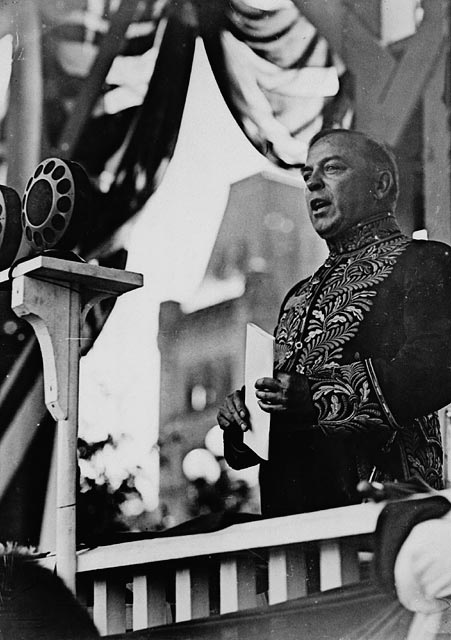

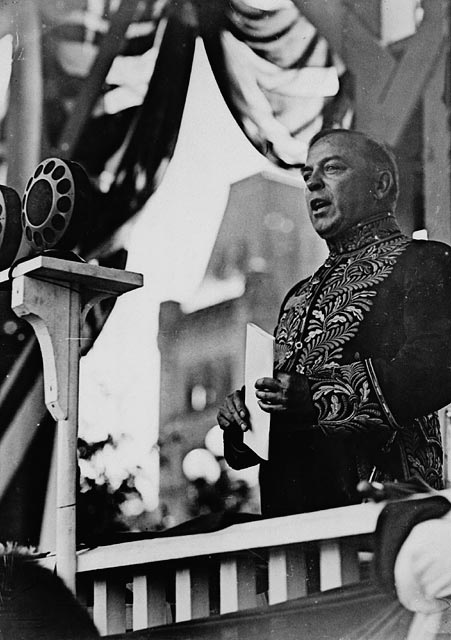

William Lyon Mackenzie King (December 17, 1874 – July 22, 1950) was a

Canadian

Canadians () are people identified with the country of Canada. This connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Canadians, many (or all) of these connections exist and are collectively the source of their being ''C ...

statesman and

politician

A politician is a person who participates in Public policy, policy-making processes, usually holding an elective position in government. Politicians represent the people, make decisions, and influence the formulation of public policy. The roles ...

who was the tenth

prime minister of Canada

The prime minister of Canada () is the head of government of Canada. Under the Westminster system, the prime minister governs with the Confidence and supply, confidence of a majority of the elected House of Commons of Canada, House of Commons ...

for three non-consecutive terms from 1921 to 1926, 1926 to 1930, and 1935 to 1948. A

Liberal, he was the dominant politician in Canada from the early 1920s to the late 1940s. King is best known for his leadership of Canada throughout the

Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

and the

Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. He played a major role in laying the foundations of the Canadian

welfare state

A welfare state is a form of government in which the State (polity), state (or a well-established network of social institutions) protects and promotes the economic and social well-being of its citizens, based upon the principles of equal oppor ...

and establishing Canada's international position as a

middle power. With a total of 21 years and 154 days in office, he remains the

longest-serving prime minister in Canadian history and as well as the longest-serving Liberal leader, holding the position for exactly 29 years.

King studied law and political economy in the 1890s and later obtained a PhD, the first of only two Canadian prime ministers to have done so. In 1900, he became deputy minister of the Canadian government's new Department of Labour. He entered the

House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the Bicameralism, bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of ...

in

1908 before becoming the federal

minister of labour in 1909 under Prime Minister

Wilfrid Laurier

Sir Henri Charles Wilfrid Laurier (November 20, 1841 – February 17, 1919) was a Canadian lawyer, statesman, and Liberal politician who served as the seventh prime minister of Canada from 1896 to 1911. The first French Canadians, French ...

. After losing his seat in the

1911 federal election, King worked for the

Rockefeller Foundation

The Rockefeller Foundation is an American private foundation and philanthropic medical research and arts funding organization based at 420 Fifth Avenue, New York City. The foundation was created by Standard Oil magnate John D. Rockefeller (" ...

before briefly working as an industrial consultant. Following the death of Laurier in 1919, King

acceded to the leadership of the Liberal Party. Taking the helm of a party torn apart by the

Conscription Crisis of 1917, he unified both the pro-

conscription

Conscription, also known as the draft in the United States and Israel, is the practice in which the compulsory enlistment in a national service, mainly a military service, is enforced by law. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it conti ...

and anti-conscription factions of the party, leading it to victory in the

1921 federal election.

King established a post-war agenda that lowered wartime taxes and tariffs. He strengthened Canadian autonomy by refusing to support Britain in the

Chanak Crisis without

Parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

's consent and negotiating the

Halibut Treaty with the United States without British interference. In the

1925 election, the

Conservatives won a plurality of seats, but the Liberals negotiated support from the

Progressive Party and stayed in office as a

minority government

A minority government, minority cabinet, minority administration, or a minority parliament is a government and cabinet formed in a parliamentary system when a political party or coalition of parties does not have a majority of overall seats in ...

. In 1926, facing a Commons vote that could force his government to resign, King asked

Governor General Lord Byng to

dissolve parliament

The dissolution of a legislative assembly (or parliament) is the simultaneous termination of service of all of its members, in anticipation that a successive legislative assembly will reconvene later with possibly different members. In a democrac ...

and call an election. Byng refused and instead invited the Conservatives to form government, who briefly held office but lost a

motion of no confidence

A motion or vote of no confidence (or the inverse, a motion or vote of confidence) is a motion and corresponding vote thereon in a deliberative assembly (usually a legislative body) as to whether an officer (typically an executive) is deemed fi ...

. This sequence of events triggered a major

constitutional crisis, the

King–Byng affair. King and the Liberals decisively won

the resulting election. After, King sought to make Canada's foreign policy more independent by expanding the

Department of External Affairs while recruiting more Canadian diplomats. His government also introduced

old-age pensions based on need. King's slow reaction to the

Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

led to

a defeat at the polls in 1930.

The Conservative government's response to the depression was unpopular and King returned to power in a

landslide victory in the

1935 election. Soon after, the economy was on an upswing. King negotiated the 1935

Reciprocal Trade Agreement with the United States, passed the 1938 ''

National Housing Act'' to improve housing affordability, introduced

unemployment insurance in 1940, and in 1944, introduced

family allowances – Canada's first universal

welfare program. The government also established

Trans-Canada Air Lines (the precursor to

Air Canada

Air Canada is the flag carrier and the largest airline of Canada, by size and passengers carried. Air Canada is headquartered in the borough of Saint-Laurent in the city of Montreal. The airline, founded in 1937, provides scheduled and cha ...

) and the

National Film Board

The National Film Board of Canada (NFB; ) is a Canadian public film and digital media producer and distributor. An agency of the Government of Canada, the NFB produces and distributes documentary films, animation, web documentaries, and altern ...

. King's government

deployed Canadian troops days after the Second World War

broke out. The Liberals' overwhelming triumph in the

1940 election allowed King to continue leading Canada through the war. He mobilized Canadian money, supplies, and volunteers to support Britain while boosting the economy and maintaining morale on the home front. To satisfy

French Canadians, King delayed introducing overseas conscription until

late 1944. That year, he also ordered the

displacement of Japanese Canadians out of the British Columbia Interior, mandating that they either resettle east of the Rocky Mountains or face deportation to Japan after the war.

The Allies'

victory in 1945 allowed King to call

a post-war election, in which the Liberals lost their

majority government

A majority government is a government by one or more governing parties that hold an absolute majority of seats in a legislature. Such a government can consist of one party that holds a majority on its own, or be a coalition government of multi ...

. In his final years in office, King and his government partnered Canada with other

Western nations to take part in the deepening

Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

,

introduced Canadian citizenship, and successfully negotiated

Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region of Labrador, having a total size of . As of 2025 the population ...

's

entry

Entry may refer to:

*Entry, West Virginia, an unincorporated community in the United States

*Entry (cards), a term used in trick-taking card-games

*Entry (economics), a term in connection with markets

*Entry (film), ''Entry'' (film), a 2013 Indian ...

into

Confederation

A confederation (also known as a confederacy or league) is a political union of sovereign states united for purposes of common action. Usually created by a treaty, confederations of states tend to be established for dealing with critical issu ...

.

After leading his party for 29 years, and leading the country for years, King retired from politics in late 1948. He died of pneumonia in July 1950. King's personality was complex; biographers agree on the personal characteristics that made him distinctive. He lacked the charisma of such contemporaries as

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

,

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

, or

Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French general and statesman who led the Free France, Free French Forces against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Government of the French Re ...

. Cold and tactless in human relations, he was said to have oratorical skill. He kept secret his beliefs in

spiritualism and use of

mediums to stay in contact with departed associates and particularly with his mother, and allowed his intense spirituality to distort his understanding of

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

throughout the late 1930s. Historian

Jack Granatstein notes, "the scholars expressed little admiration for King the man but offered unbounded admiration for his political skills and attention to Canadian unity." King is

ranked among the top three of Canadian prime ministers.

Early life (1874–1891)

King was born in a frame house rented by his parents at 43 Benton Street in Berlin (now

Kitchener), Ontario to John King and Isabel Grace Mackenzie.

His maternal grandfather was

William Lyon Mackenzie

William Lyon Mackenzie (March12, 1795 August28, 1861) was a Scottish-born Canadian-American journalist and politician. He founded newspapers critical of the Family Compact, a term used to identify the establishment of Upper Canada. He represe ...

, first mayor of

Toronto

Toronto ( , locally pronounced or ) is the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, most populous city in Canada. It is the capital city of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Ontario. With a p ...

and leader of the

Upper Canada Rebellion

The Upper Canada Rebellion was an insurrection against the Oligarchy, oligarchic government of the British colony of Upper Canada (present-day Ontario) in December 1837. While public grievances had existed for years, it was the Lower Canada Rebe ...

in 1837. His father was a lawyer and later a lecturer at

Osgoode Hall Law School. King had three siblings: older sister Isabel "Bella" Christina Grace (1873–1915), younger sister Janet "Jennie" Lindsey (1876–1962) and younger brother Dougall Macdougall "Max" (1878–1922). Within his family, he was known as Willie; during his university years, he adopted W. L. Mackenzie King as his signature and began using Mackenzie as his preferred name with those outside the family.

King's father was a lawyer with a struggling practice in a small city, and never enjoyed financial security. His parents lived a life of shabby gentility, employing servants and tutors they could scarcely afford, although their financial situation improved somewhat following a move to Toronto around 1890, where King lived with them for several years in a duplex on Beverley Street while studying at the University of Toronto.

King became a lifelong practising

Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a historically Reformed Protestant tradition named for its form of church government by representative assemblies of elders, known as "presbyters". Though other Reformed churches are structurally similar, the word ''Pr ...

with a dedication to social reform based on his Christian duty. He never favoured

socialism

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

.

University (1891–1900)

King enrolled at the

University of Toronto

The University of Toronto (UToronto or U of T) is a public university, public research university whose main campus is located on the grounds that surround Queen's Park (Toronto), Queen's Park in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. It was founded by ...

in 1891.

He obtained a

BA degree in 1895, an

LLB degree in 1896, and an

MA in 1897, all from the university. While studying in Toronto he met a wide circle of friends, many of whom became prominent. He was an early member and officer of the

Kappa Alpha Society, which included a number of these individuals (two future Ontario Supreme Court Justices and the future chairman of the university itself). It encouraged debate on political ideas. He also was simultaneously a part of the Literary Society with

Arthur Meighen, a future political rival.

King was especially concerned with issues of social welfare and was influenced by the

settlement house movement pioneered by

Toynbee Hall in London, England. He played a central role in fomenting a students' strike at the university in 1895. He was in close touch, behind the scenes, with Vice-Chancellor

William Mulock, for whom the strike provided a chance to embarrass his rivals Chancellor

Edward Blake and President

James Loudon. King failed to gain his immediate objective, a teaching position at the university but earned political credit with Mulock, the man who would invite him to

Ottawa

Ottawa is the capital city of Canada. It is located in the southern Ontario, southern portion of the province of Ontario, at the confluence of the Ottawa River and the Rideau River. Ottawa borders Gatineau, Gatineau, Quebec, and forms the cor ...

and make him a

deputy minister only five years later. While studying at the University of Toronto, King also contributed to the campus newspaper, ''

The Varsity,'' and served as president of the yearbook committee in 1896. King subsequently wrote for ''

The Globe'', ''

The Mail and Empire'', and the ''Toronto News''.

Fellow journalist

W. A. Hewitt recalled that, the city editor of the ''Toronto News'' left him in charge one afternoon with instructions to fire King if he showed up. When Hewitt sat at the editor's desk, King showed up a few minutes later and resigned before Hewitt could tell him he was fired.

After studying at the

University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, or UChi) is a Private university, private research university in Chicago, Illinois, United States. Its main campus is in the Hyde Park, Chicago, Hyde Park neighborhood on Chicago's South Side, Chic ...

and working with

Jane Addams

Laura Jane Addams (September 6, 1860May 21, 1935) was an American Settlement movement, settlement activist, Social reform, reformer, social worker, sociologist, public administrator, philosopher, and author. She was a leader in the history of s ...

at her settlement house,

Hull House, King proceeded to

Harvard University

Harvard University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the History of the Puritans in North America, Puritan clergyma ...

. While at the University of Chicago, he participated on their track team as a half-mile runner. He earned an MA in political economy from Harvard in 1898. In 1909, Harvard granted him a

PhD degree for a dissertation titled "Oriental Immigration to Canada." King and

Mark Carney are the only Canadian Prime Ministers to have earned a PhD.

Early career, civil servant (1900–1908)

In 1900, King became editor of the federal government-owned ''Labour Gazette'', a publication that explored complex labour issues. Later that year, he was appointed as deputy minister of the Canadian government's new Department of Labour, and became active in policy domains from Japanese immigration to railways, notably the ''Industrial Disputes Investigations Act'' (1907) which sought to avert labour strikes by prior conciliation.

In 1901, King's roommate and best friend,

Henry Albert Harper, died heroically during a skating party when a young woman fell through the ice of the partly frozen

Ottawa River

The Ottawa River (, ) is a river in the Canadian provinces of Ontario and Quebec. It is named after the Algonquin word "to trade", as it was the major trade route of Eastern Canada at the time. For most of its length, it defines the border betw ...

. Harper dove into the water to try to save her, and perished in the attempt. King led the effort to raise a memorial to Harper, which resulted in the erection of the

Sir Galahad statue on

Parliament Hill in 1905. In 1906, King published a memoir of Harper, entitled ''The Secret of Heroism''.

While deputy minister of labour, King was appointed to investigate the causes of and claims for compensation resulting from the 1907

anti-Oriental riots in

Vancouver's Chinatown and

Japantown. One of the claims for damages came from Chinese

opium

Opium (also known as poppy tears, or Lachryma papaveris) is the dried latex obtained from the seed Capsule (fruit), capsules of the opium poppy ''Papaver somniferum''. Approximately 12 percent of opium is made up of the analgesic alkaloid mor ...

dealers, which led King to investigate

narcotics

The term narcotic (, from ancient Greek ναρκῶ ''narkō'', "I make numb") originally referred medically to any psychoactive compound with numbing or paralyzing properties. In the United States, it has since become associated with opiates ...

use in

Vancouver

Vancouver is a major city in Western Canada, located in the Lower Mainland region of British Columbia. As the List of cities in British Columbia, most populous city in the province, the 2021 Canadian census recorded 662,248 people in the cit ...

, British Columbia. Following the investigation King reported that white women were also opium users, not just Chinese men, and the federal government used the report to justify the first legislation outlawing narcotics in Canada.

Early political career, minister of labour (1908–1911)

King was first elected to

Parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

as a

Liberal in the

1908 federal election, representing

Waterloo North. In 1909, King was appointed as the first-ever

minister of labour by Prime Minister

Wilfrid Laurier

Sir Henri Charles Wilfrid Laurier (November 20, 1841 – February 17, 1919) was a Canadian lawyer, statesman, and Liberal politician who served as the seventh prime minister of Canada from 1896 to 1911. The first French Canadians, French ...

.

King's term as minister of labour was marked by two significant achievements. He led the passage of the ''

Industrial Disputes Investigation Act'' and the ''

Combines Investigation Act'', which he had shaped during his civil and parliamentary service. The legislation significantly improved the financial situation for millions of Canadian workers. In 1910 Mackenzie King introduced a bill aimed at establishing an 8-hour day on public works but it was killed in the Senate. He lost his seat in the

1911 general election, which saw the

Conservatives defeat the Liberals and form government.

Out of politics (1911–1919)

Industrial consultant

After his defeat, King went on the lecture circuit on behalf of the Liberal Party. In June 1914

John D. Rockefeller Jr. hired him at the

Rockefeller Foundation

The Rockefeller Foundation is an American private foundation and philanthropic medical research and arts funding organization based at 420 Fifth Avenue, New York City. The foundation was created by Standard Oil magnate John D. Rockefeller (" ...

in New York City, to head its new Department of Industrial Research. It paid $12,000 per year, compared to the meagre $2,500 per year the Liberal Party was paying. He worked for the Foundation until 1918, forming a close working association and friendship with Rockefeller, advising him through the turbulent period of the 1913–1914 Strike and

Ludlow Massacre–in what is known as the

Colorado Coalfield War–at a family-owned coal company in

Colorado

Colorado is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States. It is one of the Mountain states, sharing the Four Corners region with Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah. It is also bordered by Wyoming to the north, Nebraska to the northeast, Kansas ...

, which subsequently set the stage for a new era in labour management in America. King became one of the earliest expert practitioners in the emerging field of

industrial relations

Industrial relations or employment relations is the multidisciplinary academic field that studies the employment relationship; that is, the complex interrelations between employers and employees, labor union, labor/trade

unions, employer organ ...

.

King was not a pacifist, but he showed little enthusiasm for the

Great War; he faced criticism for not serving in Canada's military and instead working for the Rockefellers. However, he was nearly 40 years old when the war began, and was not in good physical condition. He never gave up his Ottawa home, and travelled to the United States on an as-needed basis, performing service to the war effort by helping to keep war-related industries running smoothly.

In 1918, King, assisted by his friend F. A. McGregor, published ''Industry and Humanity: A Study in the Principles Underlying Industrial Reconstruction'', a dense, abstract book he wrote in response to the

Ludlow massacre. It went over the heads of most readers, but revealed the practical idealism behind King's political thinking. He argued that capital and labour were natural allies, not foes, and that the community at large (represented by the government) should be the third and decisive party in industrial disputes. He expressed derision for syndicates and trades unions, chastising them for aiming at the "destruction by force of existing organization, and the transfer of industrial capital from the present possessors" to themselves.

Quitting the Rockefeller Foundation in February 1918, King became an independent consultant on labour issues for the next two years, earning $1,000 per week from leading American corporations. Even so, he kept his official residence in Ottawa, hoping for a call to duty.

Wartime politics

In 1917, Canada was in crisis; King supported Liberal leader Wilfrid Laurier in his opposition to

conscription

Conscription, also known as the draft in the United States and Israel, is the practice in which the compulsory enlistment in a national service, mainly a military service, is enforced by law. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it conti ...

, which was violently opposed in the province of

Quebec

Quebec is Canada's List of Canadian provinces and territories by area, largest province by area. Located in Central Canada, the province shares borders with the provinces of Ontario to the west, Newfoundland and Labrador to the northeast, ...

. The Liberal party became deeply split, with several

Anglophones joining the pro-conscription

Union government, a coalition controlled by the Conservatives under Prime Minister

Robert Borden. King returned to Canada to run in the

1917 election, which focused almost entirely on the conscription issue. Unable to overcome a landslide against Laurier, King lost in the constituency of

York North, which his grandfather had once represented.

Opposition leader (1919–1921)

1919 leadership election

The Liberal Party was deeply divided by Quebec's opposition to conscription and the agrarian revolt in Ontario and the Prairies. Levin argues that when King returned to politics in 1919, he was a rusty outsider with a weak base facing a nation bitterly split by language, regionalism and class. He outmaneuvered more senior competitors by embracing Laurier's legacy, championing labour interests, calling for welfare reform, and offering solid opposition to the Conservative rivals. When Laurier died in 1919, King was elected leader in the first

Liberal leadership convention, defeating his three rivals on the fourth ballot. He won thanks to the support of the Quebec bloc, organized by

Ernest Lapointe (1876–1941), later King's long-time lieutenant in Quebec. King could not speak French, but in election after election for the next 20 years (save for 1930), Lapointe produced the critical seats to give the Liberals control of the Commons. When campaigning in Quebec, King portrayed Lapointe as co-prime minister.

Idealizes the Prairies

Once King became the Liberal leader in 1919 he paid closer attention to the

Prairies, a fast-developing region. Viewing a sunrise in

Alberta

Alberta is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province in Canada. It is a part of Western Canada and is one of the three Canadian Prairies, prairie provinces. Alberta is bordered by British Columbia to its west, Saskatchewan to its east, t ...

in 1920, he wrote in his diary, "I thought of the New Day, the New Social Order. It seems like Heaven's prophecy of the dawn of a new era, revealed to me." Pragmatism played a role as well, since his party depended for its survival on the votes of

Progressive Party Members of Parliament, many of whom who represented farmers in Ontario and the Prairies. He convinced many Progressives to return to the Liberal fold.

1921 federal election

In the

1921 election, King's Liberals defeated the

Conservatives led by Prime Minister

Arthur Meighen, winning a narrow majority of 118 out of 235 seats. The Conservatives won 50, the newly formed Progressive Party won 58 (but declined to form the official Opposition), and the remaining ten seats went to Labour MPs and Independents; most of these ten supported the Progressives. King became prime minister.

Prime Minister (1921–1926, 1926–1930)

As prime minister of Canada, King was appointed to the

Privy Council of the United Kingdom on 20 June 1922 and was sworn at Buckingham Palace on October 11, 1923, during the

1923 Imperial Conference

The 1923 Imperial Conference met in London in the autumn of 1923, the first attended by the new Irish Free State. While named the Imperial Economic Conference, the principal activity concerned the rights of the Dominions in regards to determinin ...

.

Balancing act

During his first term of office, from 1921 to 1926, King sought to lower wartime taxes and, especially, wartime ethnic and labour tensions. "The War is over", he argued, "and for a long time to come it is going to take all that the energies of man can do to bridge the chasm and heal the wounds which the War has made in our social life."

Despite prolonged negotiations, King was unable to attract the Progressives into his government, but once Parliament opened, he relied on their support to defeat

non-confidence motions from the Conservatives. King was opposed in some policies by the Progressives, who opposed the high

tariff

A tariff or import tax is a duty (tax), duty imposed by a national Government, government, customs territory, or supranational union on imports of goods and is paid by the importer. Exceptionally, an export tax may be levied on exports of goods ...

s of the

National Policy. King faced a delicate balancing act of reducing tariffs enough to please the Prairie-based Progressives, but not so much as to alienate his vital supporters in industrial Ontario and Quebec, who perceived tariffs were necessary to compete with American imports.

[ Hutchison (1952)]

Over time, the Progressives gradually weakened. Their effective and passionate leader,

Thomas Crerar, resigned to return to his grain business, and was replaced by the more placid

Robert Forke, who joined King's cabinet in 1926 as Minister of Immigration and Colonization after becoming a

Liberal-Progressive. Socialist reformer

J. S. Woodsworth gradually gained influence and power, and King was able to reach an accommodation with him on policy matters. In any event, the Progressive caucus lacked the party discipline that was traditionally enforced by the Liberals and Conservatives. The Progressives had campaigned on a promise that their MP's would represent their constituents first. King used this to his advantage, as he could always count on at least a handful of Progressive MPs to shore up his near-majority position for any crucial vote.

Immigration

In 1923, King's government passed the ''

Chinese Immigration Act, 1923'' banning most forms of

Chinese immigration to Canada. Immigration from most countries was controlled or restricted in some way, but only the Chinese were completely prohibited from immigrating. This was after various members of the federal and some provincial governments (especially

British Columbia

British Columbia is the westernmost Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada. Situated in the Pacific Northwest between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains, the province has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that ...

) put pressure on the federal government to discourage Chinese immigration.

Also in 1923, the government modified the ''

Immigration Act'' to allow former subjects of

Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe#Before World War I, Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military ...

to once again enter Canada. Ukrainian immigration resumed after restrictions were put in place during World War I.

City planning

King had a long-standing concern with city planning and the development of the national capital, since he had been trained in the settlement house movement and envisioned town planning and garden cities as a component of his broader program of social reform. He drew on four broad traditions in early North American planning: social planning, the Parks Movement, the City Scientific, and the

City Beautiful. King's greatest impact was as the political champion for the planning and development of Ottawa, Canada's national capital. His plans, much of which were completed in the two decades after his death, were part of a century of federal planning that repositioned Ottawa as a national space in the City Beautiful style.

Confederation Square, for example, was initially planned to be a civic plaza to balance the nearby federal presence of Parliament Hill and was turned into a war memorial. The Great War monument was not installed until the 1939 royal visit, and King intended that the replanning of the capital would be the World War I memorial. However, the symbolic meaning of the World War I monument gradually expanded to become the place of remembrance for all Canadian war sacrifices and includes a war memorial.

Corruption scandals

King called an

election in 1925, in which the

Conservatives won the most seats, but not a majority in the

House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the Bicameralism, bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of ...

. King held onto power with the support of the Progressives. A corruption scandal discovered late in his first term involved misdeeds around the expansion of the

Beauharnois Canal in Quebec; this led to extensive inquiries and eventually a

Royal Commission

A royal commission is a major ad-hoc formal public inquiry into a defined issue in some monarchies. They have been held in the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Norway, Malaysia, Mauritius and Saudi Arabia. In republics an equi ...

, which exposed the

Beauharnois Scandal. The resulting press coverage damaged King's party in the election. Early in his second term, another

corruption

Corruption is a form of dishonesty or a criminal offense that is undertaken by a person or an organization that is entrusted in a position of authority to acquire illicit benefits or abuse power for one's gain. Corruption may involve activities ...

scandal, this time in the Department of Customs, was revealed, which led to more support for the Conservatives and Progressives, and the possibility that King would be forced to resign, if he lost sufficient support in the Commons. King had no personal connection to this scandal, although one of his own appointees was at the heart of it. Opposition leader Meighen unleashed his fierce invective towards King, stating he was hanging onto power "like a lobster with lockjaw".`

King–Byng Affair

In June 1926, King, facing a House of Commons vote connected to the customs scandal that could force his government to resign, advised the

Governor General,

Lord Byng, to dissolve Parliament and call another election. Byng, however, declined the Prime Minister's request – the first time in

Canadian history that a request for dissolution was refused; and, to date, the only time the governor general of Canada has done so. Byng instead asked

Leader of the Opposition

The Leader of the Opposition is a title traditionally held by the leader of the Opposition (parliamentary), largest political party not in government, typical in countries utilizing the parliamentary system form of government. The leader of the ...

, Arthur Meighen, to form government. Although the Conservatives held more seats in the House than any other party, they did not control a majority. They were soon themselves defeated on a

motion of non-confidence on July 2. Meighen himself then requested a dissolution of Parliament, which Byng now granted.

King ran the

1926 Liberal election campaign largely on the issue of the right of Canadians to govern themselves and against the interference of the Crown. The Liberal Party was returned to power with a

minority government

A minority government, minority cabinet, minority administration, or a minority parliament is a government and cabinet formed in a parliamentary system when a political party or coalition of parties does not have a majority of overall seats in ...

, which bolstered King's position on the issue and the position of the Prime Minister generally. King later pushed for greater Canadian autonomy at the

1926 Imperial Conference which elicited the

Balfour Declaration stating that upon the granting of

dominion

A dominion was any of several largely self-governance, self-governing countries of the British Empire, once known collectively as the ''British Commonwealth of Nations''. Progressing from colonies, their degrees of self-governing colony, colon ...

status, Canada, Australia, New Zealand,

Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region of Labrador, having a total size of . As of 2025 the population ...

, South Africa, and the

Irish Free State

The Irish Free State (6 December 192229 December 1937), also known by its Irish-language, Irish name ( , ), was a State (polity), state established in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. The treaty ended the three-ye ...

, while still autonomous communities within the

British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

, ceased to be subordinate to the United Kingdom. Thus, the governor general ceased to represent the British government and was solely the personal representative of the sovereign while becoming a representative of

The Crown

The Crown is a political concept used in Commonwealth realms. Depending on the context used, it generally refers to the entirety of the State (polity), state (or in federal realms, the relevant level of government in that state), the executive ...

. This ultimately was formalized in the

Statute of Westminster 1931

The Statute of Westminster 1931 is an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that significantly increased the autonomy of the Dominions of the British Commonwealth.

Passed on 11 December 1931, the statute increased the sovereignty of t ...

. On September 14, King and his party won the election with a plurality of seats in the Commons: 116 seats to the Conservatives' 91 in a 245-member House.

Extending Canadian autonomy

During the

Chanak Crisis of 1922, King refused to support the British without first consulting

Parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

, while the Conservative leader, Arthur Meighen, supported Britain. King sought a Canadian voice independent of

London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

in foreign affairs. In September 1922 the British Prime Minister,

David Lloyd George, appealed repeatedly to King for Canadian support in the crisis. King coldly replied that the Canadian Parliament would decide what policy to follow, making clear it would not be bound by London's suggestions. King wrote in his diary of the British appeal: "I confess it annoyed me. It is drafted designedly to play the imperial game, to test out centralization versus autonomy as regards European wars...No

anadiancontingent will go without parliament being summoned in the first instance". The British were disappointed with King's response but the crisis was soon resolved, as King had anticipated.

After Chanak, King was concerned about the possibility that Canada might go to war because of its connections with Britain, writing to

Violet Markham:

Anything like centralization in London, to say nothing of a direct or indirect attempt on the part of those in office in Downing Street to tell the people of the Dominions what they should or should not do, and to dictate their duty in matters of foreign policy, is certain to prove just as injurious to the so-called 'imperial solidarity' as any attempt at interference in questions of purely domestic concern. If membership within the British Commonwealth means participation by the Dominions in any and every war in which Great Britain becomes involved, without consultation, conference, or agreement of any kind in advance, I can see no hope for an enduring relationship.

For years,

halibut stocks were depleting in Canadian and American fishing areas in the North

Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five Borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean, or, depending on the definition, to Antarctica in the south, and is ...

. In 1923, King's government negotiated the

Halibut Treaty with the United States. The treaty annually prohibited commercial fishing from November 16 to February 15; violation would result in seizure. The agreement was notable in that Canada negotiated it without a British delegate at the table and without ratification from the

British Parliament; though not official,

convention stated that the United Kingdom would have a seat at the table or be a signatory to any agreement Canada was part of. King argued the situation only concerned Canada and the United States. After, the British accepted King's intentions to send a separate Canadian diplomat to

Washington D.C. (to represent Canada's interests) rather than a British one. At the

1923 Imperial Conference

The 1923 Imperial Conference met in London in the autumn of 1923, the first attended by the new Irish Free State. While named the Imperial Economic Conference, the principal activity concerned the rights of the Dominions in regards to determinin ...

, Britain accepted the Halibut Treaty, arguing it set a new precedent for the role of

British Dominions.

King expanded the

Department of External Affairs, founded in 1909, to further promote Canadian autonomy from Britain. The new department took some time to develop, but over time it significantly increased the reach and projection of Canadian diplomacy. Prior to this, Canada had relied on British diplomats who owed their first loyalty to London. After the King–Byng episode, King recruited many high-calibre people for the new venture, including future prime minister

Lester Pearson and influential career administrators

Norman Robertson and

Hume Wrong. This project was a key element of his overall strategy, setting Canada on a course independent of Britain, of former colonizer

France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

, as well as of the neighbouring powerful United States.

Throughout his tenure, King led Canada from a dominion with responsible government to an autonomous nation within the

British Commonwealth

The Commonwealth of Nations, often referred to as the British Commonwealth or simply the Commonwealth, is an international association of 56 member states, the vast majority of which are former territories of the British Empire

The B ...

. King asserted Canadian autonomy against the British government's attempts to turn the Commonwealth into an alliance. His biographer asserts that "in this struggle Mackenzie King was the constant aggressor". The Canadian High Commissioner to Britain,

Vincent Massey, claimed that an "anti-British bias" was "one of the most powerful factors in his make-up".

Other reforms

In domestic affairs, King strengthened the Liberal policy of increasing the powers of the provincial governments by transferring to the governments of

Manitoba

Manitoba is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada at the Centre of Canada, longitudinal centre of the country. It is Canada's Population of Canada by province and territory, fifth-most populous province, with a population ...

,

Alberta

Alberta is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province in Canada. It is a part of Western Canada and is one of the three Canadian Prairies, prairie provinces. Alberta is bordered by British Columbia to its west, Saskatchewan to its east, t ...

, and

Saskatchewan

Saskatchewan is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province in Western Canada. It is bordered on the west by Alberta, on the north by the Northwest Territories, on the east by Manitoba, to the northeast by Nunavut, and to the south by the ...

the ownership of the crown lands within those provinces, as well as the subsoil rights; these in particular would become increasingly important, as petroleum and other natural resources proved very abundant. In collaboration with the provincial governments, he inaugurated a system of

old-age pensions based on need. In February 1930, he appointed

Cairine Wilson as the first female

senator

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or Legislative chamber, chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the Ancient Rome, ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior ...

in Canadian history.

Reductions in taxation were carried out such as exemptions under the sales tax on commodities and enlarged exemptions of income tax, while in 1929 taxes on cables, telegrams, and railway and steamship tickets were removed. In 1924, a Civil Service Superannuation Act was passed with the aim of providing public servants with a suitable income upon retirement from the public service. Under c.39 of 1922, civil servants who were unfit for further duty “may be retired even if they are under 65 years of age.” Under c.42 of 1922, various social provisions were introduced for returned soldiers and dependents. An Act of 1923 improved pension eligibility for returned soldiers. Entitlement to military pensions was also extended. In 1929, a previous Insurance Act was amended to enable fraternal societies to issue endowment policies for a period of twenty years or longer, and to increase their maximum policies to $10,000 under certain conditions.

Measures were also carried out to support farmers. In 1922, for instance, a measure was introduced and passed "restoring the Crow's Nest Pass railways rates on grain and flour moving eastwards from the prairie provinces." A Farm Loan Board was set up to provide rural credit; advancing funds to farmers "at rates of interest and under terms not obtainable from the usual sources," while other measures were carried out such as preventative measures against foot and mouth disease and the establishment of grading standards "to assist in the marketing of agricultural products" both at home and overseas. In addition, the ''Combines Investigation Act of 1923'' was aimed at safeguarding consumers and producers from exploitation.

Several measures affecting labour were also carried out. In July 1922, an Order in Council was adopted to secure a more effective observance of a fair wages policy. From 1924 onwards, the employment of young persons at sea was regulated in accordance with various international labour conventions. In 1927, the Government Employees' Compensation Act was amended by the Dominion Parliament to provide (as noted by one study) “that all employees of the Dominion government in Prince Edward Island should be eligible for compensation in the same manner and at the same rate as similar workers in New Brunswick.” An order of March 1930 entitled employees of the Dominion Government who worked more than 8 hours daily to an 8-hour workday with a half-holiday on Saturdays. That same year, a Fair Wages and Eight Hours Day Act was introduced.

Defeat in 1930

King's government was in power at the beginning of the

Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

, but was slow to respond to the mounting crisis. He felt that the crisis was a temporary swing of the business cycle and that the economy would soon recover without government intervention. Critics said he was out of touch. Just prior to the election, King carelessly remarked that he "would not give a five-cent piece" to Tory provincial governments for unemployment relief.

The opposition made this remark a catch-phrase; the main issue was the deterioration in the economy and whether the prime minister was out of touch with the hardships of ordinary people. The Liberals lost the

election of 1930 to the Conservative Party, led by

Richard Bedford Bennett. The popular vote was very close between the two parties, with the Liberals actually earning more votes than in 1926, but the Conservatives had a geographical advantage that turned into enough seats to give a majority.

Opposition leader (1930–1935)

After his 1930 election loss, King stayed on as Liberal leader, becoming the

leader of the Opposition

The Leader of the Opposition is a title traditionally held by the leader of the Opposition (parliamentary), largest political party not in government, typical in countries utilizing the parliamentary system form of government. The leader of the ...

for the second time. He began his years as Opposition leader convinced that his government did not deserve defeat and that its financial caution had helped the economy prosper. He blamed the financial crisis on the speculative excesses of businessmen and on the weather cycle. King argued that the worst mistake Canada could make in reacting to the Depression was to raise tariffs and restrict international trade. He believed that over time, voters would learn that Bennett had deceived them and they would come to appreciate the King government's policy of frugality and

free trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold Economic liberalism, economically liberal positions, while economic nationalist politica ...

.

King's policy was to refrain from offering advice or alternative policies to the Conservative government. Indeed, his policy preferences were not much different from Bennett's, and he let the government have its way. Though he gave the impression of sympathy with progressive and liberal causes, he had no enthusiasm for the

New Deal

The New Deal was a series of wide-reaching economic, social, and political reforms enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1938, in response to the Great Depression in the United States, Great Depressi ...

of U.S. President

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

(which Bennett eventually tried to emulate, after floundering without solutions for several years), and he never advocated massive government action to alleviate the Depression in Canada.

As Opposition leader, King denounced the Bennett government's

budget deficits as irresponsible, though he did not suggest his own idea of how budgets could be

balanced. King also denounced the "blank cheques" that Parliament was asked to approve for relief and delayed the passage of these bills despite the objections of some Liberals, who feared the public might conclude that the party had no sympathy for those struggling. Each year, after the throne speech and the budget, King introduced amendments that blamed the Depression on Bennett's policy of high tariffs.

By the time the

1935 election arrived, the Bennett government was heavily unpopular due to its handling of the Depression. Using the slogan "King or Chaos", the Liberals won a

landslide victory, winning 173 out of the Commons' 245 seats and reducing the Conservatives to a

rump of 40; this was the largest

majority government

A majority government is a government by one or more governing parties that hold an absolute majority of seats in a legislature. Such a government can consist of one party that holds a majority on its own, or be a coalition government of multi ...

at the time.

Prime Minister (1935–1948)

For the first time in his political career, King led an undisputed Liberal majority government. Upon his return to office in October 1935, he demonstrated a commitment (like his American counterpart Roosevelt) to the underprivileged, speaking of a new era where "poverty and adversity, want and misery are the enemies which liberalism will seek to banish from the land". Once again, King appointed himself as

secretary of state for external affairs; he held this post until 1946.

Economic reforms

Free trade

Promising a much-desired trade treaty with the U.S., the King government passed the 1935

Reciprocal Trade Agreement. It marked a turning point in Canadian-American economic relations, reversing the disastrous trade war of 1930–31, lowering tariffs, and yielding a dramatic increase in trade. More subtly, it revealed to the prime minister and President Roosevelt that they could work well together.

Social programs

King's government introduced the National Employment Commission in 1936. As for the unemployed, King was hostile to federal relief.

However, the first compulsory national

unemployment insurance program was instituted in August 1940 under the King government after a constitutional amendment was agreed to by all of the Canadian provinces, to concede to the federal government legislative power over unemployment insurance. New Brunswick, Alberta and Quebec had held out against the federal government's desire to amend the constitution but ultimately acceded to its request, Alberta being the last to do so. The ''

British North America Act

The British North America Acts, 1867–1975, are a series of acts of Parliament that were at the core of the Constitution of Canada. Most were enacted by the Parliament of the United Kingdom and some by the Parliament of Canada. Some of the a ...

'' Section 91 was amended by adding in a heading designated Number 2A simply in the words "Unemployment Insurance". As far back as February 1933, the Liberals had committed themselves to introducing unemployment insurance; with a declaration by Mackenzie King that was endorsed by all members of the parliamentary party and the National Liberal Federation in which he called for such a system to be put in place.

Over the next thirteen years, a wide range of reforms were realized during King's last period in office as prime minister. In 1937, the age for blind persons to qualify for old-age pensions was reduced to 40 in 1937, and later to 21 in 1947. In 1939, compulsory contributions for pensions for low-income widows and orphans were introduced (although these only covered the regularly employed) while depressed farmers were subsidized from that same year onwards. In 1944, family allowances were introduced. King had various arguments in favour of family allowances, one of which, as noted by one study, was that family allowances "would mean better food, clothing and medical and dental care for children in low-income families." These were approved after divisions in cabinet. From 1948 the federal government subsidized medical services in the provinces; a policy which led to developments in services such as dental care.

Spending management

The provincial governments faced declining revenues and higher welfare costs. They needed federal grants and loans to reduce their deficits. In a December 1935 conference with the premiers, King announced that the federal grants would be increased until the spring of 1936. At this stage, King's main goal was to have a federal system in which each level of government would pay for its programs out of its own tax sources.

King only reluctantly accepted a

Keynesian solution that involved federal

deficit spending

Within the budgetary process, deficit spending is the amount by which spending exceeds revenue over a particular period of time, also called simply deficit, or budget deficit, the opposite of budget surplus. The term may be applied to the budg ...

, tax cuts, and subsidies to the housing market.

King and his

finance minister,

Charles Avery Dunning, had planned to

balance the budget for 1938. However, some colleagues, to King's surprise, opposed that idea and instead favoured job creation to stimulate the economy, citing British economist

John Maynard Keynes

John Maynard Keynes, 1st Baron Keynes ( ; 5 June 1883 – 21 April 1946), was an English economist and philosopher whose ideas fundamentally changed the theory and practice of macroeconomics and the economic policies of governments. Originall ...

's theory that governments could increase employment by spending during times of low private investment. In a politically motivated move, King accepted their arguments and hence ran deficits in both 1938 and 1939.

Workers

Various reforms affecting working people were also introduced. The various provinces were assisted by the ''Federal Unemployment and Agricultural Assistance Act of 1938'' and the ''Youth Training Act of 1939'' to create training programs for young persons, while an amendment to the ''

Criminal Code

A criminal code or penal code is a document that compiles all, or a significant amount of, a particular jurisdiction's criminal law. Typically a criminal code will contain offences that are recognised in the jurisdiction, penalties that might ...

'' in May 1939 provided against refusal to hire, or dismissal, "solely because of a person's membership in a lawful trade-union or association".

The ''Vocational Training Co-ordination Act'' of 1942 provided an impetus to the provinces to set up facilities for postsecondary vocational training. Further, in 1948, the ''Industrial Relations and Disputes Investigation Act'' was passed; this act safeguarded the rights of workers to join unions while requiring employers to recognize unions chosen by their employees. A Fisheries Price Support Act was also introduced with the aim of providing fishermen with similar safeguards to industrial workers covered by minimum wage legislation.

Housing

The Federal Home Improvement Plan of 1937 provided subsidized rates of interest on rehabilitation loans to 66,900 homes, while the ''

National Housing Act'' of 1938 made provision for the building of low-rent housing. Another Housing Act was later passed in 1944 with the intention of providing federally guaranteed loans or mortgages to individuals who wished to repair or construct dwellings through their own initiative.

Agriculture

While King opposed Bennett's

Canadian Wheat Board in 1935, he accepted its operation. However, by 1938, the board had sold its holdings and King proposed returning to the open market. This angered

Western Canadian farmers, who favoured a board that would give them a guaranteed minimum price, with the federal government covering any losses. Facing a public campaign to keep the board, King and his

minister of agriculture,

James Garfield Gardiner, reluctantly extended the board's life and offered a minimum price that would protect the farmers from further declines.

Also, from 1935 onwards, measures were carried out to promote prairie farm rehabilitation. Also, in 1945 a Farm Improvement Loans Act was introduced that provided for bank loans for purposes such as land improvement and the repair and construction of farm buildings.

Crown corporations

In 1937, King's government established the

Trans-Canada Air Lines (the precursor to

Air Canada

Air Canada is the flag carrier and the largest airline of Canada, by size and passengers carried. Air Canada is headquartered in the borough of Saint-Laurent in the city of Montreal. The airline, founded in 1937, provides scheduled and cha ...

), as a subsidiary of the

crown corporation

Crown corporation ()

is the term used in Canada for organizations that are structured like private companies, but are directly and wholly owned by the government.

Crown corporations have a long-standing presence in the country, and have a sign ...

,

Canadian National Railways. It was created to provide air service to all regions of Canada.

In 1938, King's government

nationalized the

Bank of Canada

The Bank of Canada (BoC; ) is a Crown corporations of Canada, Crown corporation and Canada's central bank. Chartered in 1934 under the ''Bank of Canada Act'', it is responsible for formulating Canada's monetary policy,OECD. OECD Economic Surve ...

into a crown corporation.

Media reforms

In 1936, the

Canadian Radio Broadcasting Commission (CRBC) became the

Canadian Broadcasting Corporation

The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (), branded as CBC/Radio-Canada, is the Canadian Public broadcasting, public broadcaster for both radio and television. It is a Crown corporation that serves as the national public broadcaster, with its E ...

(CBC), a

crown corporation

Crown corporation ()

is the term used in Canada for organizations that are structured like private companies, but are directly and wholly owned by the government.

Crown corporations have a long-standing presence in the country, and have a sign ...

. The CBC had a better organizational structure, more secure funding through the use of a licence fee on receiving sets (initially set at $2.50), and less vulnerability to political pressure. When Bennett's Conservatives were governing and the Liberals were in Opposition, the Liberals accused the network of being biased towards the Conservatives. During the 1935 election campaign, the CRBC broadcast a series of 15 minutes soap operas called ''Mr. Sage'' which were critical of King and the Liberal Party. Decried as political propaganda, the incident was one factor in King's decision to replace the CRBC.

In 1938, King's government invited British documentary maker

John Grierson

John Grierson (26 April 1898 – 19 February 1972) was a Scottish documentary maker, often considered the father of British and Canadian documentary film. In 1926, Grierson coined the term "documentary" in a review of Robert J. Flaherty's '' ...

to study the situation of the government's film production (which at that time was the responsibility of the

Canadian Government Motion Picture Bureau). King believed that

Canadian cinema deserved an increased presence in Canadian theatres. This report prompted the ''National Film Act'', which created the

National Film Board of Canada

The National Film Board of Canada (NFB; ) is a Canadian public film and digital media producer and distributor. An agency of the Government of Canada, the NFB produces and distributes documentary films, animation, web documentaries, and altern ...

in 1939. It was created to produce and distribute films serving the national interest and was intended specifically to make Canada better known both domestically and internationally. Gierson was appointed the first film commissioner in October 1939.

Relationship with provinces

After 1936, the prime minister lost patience when

Western Canadians preferred radical alternatives such as the CCF (

Co-operative Commonwealth Federation

The Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF; , FCC) was a federal democratic socialism, democratic socialistThe following sources describe the CCF as a democratic socialist political party:

*

*

*

*

*

* and social democracy, social-democ ...

) and

Social Credit to his middle-of-the-road liberalism. Indeed, he came close to writing off the region with his comment that the prairie dust bowl was "part of the U.S. desert area. I doubt if it will be of any real use again."

Instead he paid more attention to the industrial regions and the needs of Ontario and Quebec, particularly with respect to the proposed

St. Lawrence Seaway project with the United States.

In 1937,

Maurice Duplessis, the

conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civiliza ...

Union Nationale premier of Quebec, passed the

Padlock Law (the ''Act to Protect the Province Against Communistic Propaganda''), which intimidated labour leaders by threatening to lock up their offices for any alleged communist activities. King's government, which had already repealed the section of the ''Criminal Code'' banning unlawful associations, considered disallowing this bill. However, King's cabinet minister,

Ernest Lapointe, believed this would harm the Liberal Party's electoral chances in Quebec. King and his English-Canadian ministers accepted Lapointe's view; as King wrote in his diary in July 1938, "we were prepared to accept what really should not, in the name of liberalism, be tolerated for one moment."

Germany and Hitler

In March 1936, in response to the German

remilitarization of the Rhineland, King had the

High Commission of Canada in the United Kingdom inform the British government that if Britain went to war with Germany over the

Rhineland

The Rhineland ( ; ; ; ) is a loosely defined area of Western Germany along the Rhine, chiefly Middle Rhine, its middle section. It is the main industrial heartland of Germany because of its many factories, and it has historic ties to the Holy ...

issue, Canada would remain neutral. In June 1937, during an

Imperial Conference

Imperial Conferences (Colonial Conferences before 1907) were periodic gatherings of government leaders from the self-governing colonies and dominions of the British Empire between 1887 and 1937, before the establishment of regular Meetings of ...

in London of the prime ministers of every dominion, King informed Britain's Prime Minister

Neville Chamberlain

Arthur Neville Chamberlain (; 18 March 18699 November 1940) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940 and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from ...

that Canada would only go to war if Britain were directly attacked, and that if the British were to become involved in a continental war then Chamberlain was not to expect Canadian support.

In 1937, King visited

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

and met with

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

.

Possessing a religious yearning for direct insight into the hidden mysteries of life and the universe, and strongly influenced by the operas of

Richard Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( ; ; 22 May 181313 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, essayist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most o ...

(who was also Hitler's favourite composer), King decided Hitler was akin to mythical

Wagnerian heroes within whom good and evil were struggling. He thought that good would eventually triumph and Hitler would redeem his people and lead them to a harmonious, uplifting future. These spiritual attitudes not only guided Canada's relations with Hitler but gave the prime minister the comforting sense of a higher mission, that of helping to lead Hitler to peace. King commented in his journal that "he is really one who truly loves his fellow-men, and his country, and would make any sacrifice for their good". King forecast that:

In late 1938, during the great crisis in Europe over

Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia ( ; Czech language, Czech and , ''Česko-Slovensko'') was a landlocked country in Central Europe, created in 1918, when it declared its independence from Austria-Hungary. In 1938, after the Munich Agreement, the Sudetenland beca ...

that culminated in the

Munich Agreement

The Munich Agreement was reached in Munich on 30 September 1938, by Nazi Germany, the United Kingdom, the French Third Republic, French Republic, and the Kingdom of Italy. The agreement provided for the Occupation of Czechoslovakia (1938–194 ...

, Canadians were divided. Francophones insisted on neutrality, as did some top advisers like

Oscar D. Skelton. Anglophones stood behind Britain and were willing to fight Germany. King, who served as his own secretary of state for external affairs (foreign minister), said privately that if he had to choose he would not be neutral, but he made no public statement. All of Canada was relieved that the Munich Agreement, while sacrificing the sovereignty of Czechoslovakia, seemed to bring peace.

Under King's administration, the Canadian government, responding to strong public opinion, especially in Quebec, refused to expand immigration opportunities for

Jewish

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

refugee

A refugee, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), is a person "forced to flee their own country and seek safety in another country. They are unable to return to their own country because of feared persecution as ...

s from Europe. In June 1939 Canada, along with

Cuba

Cuba, officially the Republic of Cuba, is an island country, comprising the island of Cuba (largest island), Isla de la Juventud, and List of islands of Cuba, 4,195 islands, islets and cays surrounding the main island. It is located where the ...

and the United States, refused to allow entry for the 900 Jewish refugees aboard the passenger ship . King's government was widely criticized for its antisemitic policies and refusal to admit Jewish refugees. Most famously, when

Frederick Blair, an immigration official in King's party, was asked how many Jewish refugees Canada would admit after

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, he replied "None is too many". This policy was wholly supported by King and his political allies.

Second World War

King accompanied the Royal Couple—King

George VI

George VI (Albert Frederick Arthur George; 14 December 1895 – 6 February 1952) was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 until Death and state funeral of George VI, his death in 1952 ...

and Queen Elizabeth—throughout their 1939 cross-Canada tour, as well as on their American visit, a few months before the start of World War II.

Declaration of war

According to historian

Norman Hillmer, as British Prime Minister

Neville Chamberlain

Arthur Neville Chamberlain (; 18 March 18699 November 1940) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940 and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from ...

"negotiated in Munich with Adolf Hitler in September 1938, Mackenzie King, Canada's Prime Minister, grew agitated." King realized the likelihood of

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

and began mobilizing on August 25, 1939, with full mobilization on September 1, 1939, the day Germany invaded Poland. In 1914, at the beginning of World War I, Canada had been at war by virtue of King

George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until Death and state funeral of George V, his death in 1936.

George w ...

's declaration, issued solely on the advice of the British government. In 1939, King asserted Canada's autonomy and convened the House of Commons on September 7, nearly a month ahead of schedule, to discuss the government's intention to enter the war. King affirmed Canadian autonomy by saying that the Canadian Parliament would make the final decision on the issue of going to war. He reassured the pro-British Canadians that Parliament would surely decide that Canada would be at Britain's side if Great Britain was drawn into a major war. At the same time, he reassured those who were suspicious of British influence in Canada by promising that Canada would not participate in British colonial wars. His

Quebec lieutenant,

Ernest Lapointe, promised French Canadians that the government would not introduce conscription for overseas service; individual participation would be voluntary. These promises made it possible for Parliament to agree almost unanimously to

declare war on September 9. On September 10, King, through his high commissioner in London, issued a request to King George VI, asking him, in his capacity as King of Canada, to

declare Canada at war against Germany.

Foreign policy

To re-arm Canada, King built the

Royal Canadian Air Force

The Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF; ) is the air and space force of Canada. Its role is to "provide the Canadian Forces with relevant, responsive and effective airpower". The RCAF is one of three environmental commands within the unified Can ...

as a viable military power, while at the same time keeping it separate from Britain's

Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the Air force, air and space force of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies. It was formed towards the end of the World War I, First World War on 1 April 1918, on the merger of t ...

. He was instrumental in obtaining the

British Commonwealth Air Training Plan Agreement, which was signed in Ottawa in December 1939, binding Canada, Britain, New Zealand and Australia to a program that eventually trained half the airmen from those four nations in the Second World War.

King linked Canada more and more closely to the United States, signing

an agreement with Roosevelt at

Ogdensburg, New York, in August 1940 that provided for the close cooperation of Canadian and American forces, despite the fact that the U.S. remained officially neutral until the bombing of

Pearl Harbor

Pearl Harbor is an American lagoon harbor on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, west of Honolulu. It was often visited by the naval fleet of the United States, before it was acquired from the Hawaiian Kingdom by the U.S. with the signing of the Reci ...

on December 7, 1941. During the war the Americans took virtual control of the

Yukon

Yukon () is a Provinces and territories of Canada, territory of Canada, bordering British Columbia to the south, the Northwest Territories to the east, the Beaufort Sea to the north, and the U.S. state of Alaska to the west. It is Canada’s we ...

in building the

Alaska Highway, and major airbases in

Newfoundland