Mabel Dwight on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Mabel Dwight (1875–1955) was an American artist whose

Born in

Born in

lithographs

Lithography () is a planographic method of printing originally based on the immiscibility of oil and water. The printing is from a stone ( lithographic limestone) or a metal plate with a smooth surface. It was invented in 1796 by the German ...

showed scenes of ordinary life with humor and tolerance. Carl Zigrosser

Carl Zigrosser (1891–1975) was an art dealer best known for founding and running the New York Weyhe Gallery in the 1920s and 1930s, and as Curator of Prints and Drawings at the Philadelphia Museum of Art between 1940 and 1963. In the 1910s, h ...

, who had studied it carefully, wrote that "Her work is imbued with pity and compassion, a sense of irony, and the understanding that comes of deep experience." Between the late 1920s and the early 1940s, she achieved both popularity and critical success. In 1936, ''Prints'' magazine named her one of the best living printmakers and a critic at the time said she was one of the foremost lithographers in the United States.

Early life and education

Born in

Born in Cincinnati

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state lin ...

and raised in New Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

The last years of the 1930s proved to be the high point of Dwight's career. In the early 1940s, her work continued to appear in New York group shows, including the Weyhe Gallery (1941, 1942), a collaborative dealers' show at the American Fine Arts Building (1941), and the National Academy of Design (1942), but after 1942 there were practically none. When a group of her lithographs appeared at the t. Louis Art Museum in 1947, a critic noted that they had been printed in the 1930s. Calling them ""saturated with mood" and "pleasing to the eye", the critic praised her ability to portray "comic aspects with gaiety rather than sarcasm" and said the human figures she showed were "solid and carefully built up psychologically as well as physically."

During the 1940s, Dwight made a watercolor called ''Farm House in the Fall'', shown here, Image No. 12. After turning to lithography in 1926, she had continued to make some watercolors and colored drawings. In 1933, a watercolor she called ''Listening In'' was included in the Whitney Museum's first biennial exhibition of contemporary American sculpture, watercolors, and prints. Unlike ''Chess on Deck'' (Image No. 3) and most of her other work, its setting is rural and it contains no human or animal figures. In that respect, it may fall into a category mentioned in her essay on satire, in that it appears to address compositional problems and technical difficulties but not what she called "discrepancies between the real and the ideal". From her earliest efforts onward, most her pictures were full either of human figures or subjects that evoked human emotions and were as one observer said, "probes into the depths of the drama of everyday human life". In them, as another said, Dwight's empathy for her subjects is apparent as well as her droll sense of humor. In a brief biography of Dwight, a curator at the Smithsonian American Art Museum characterized Dwight as "keen observer of the human comedy, which she depicted with humor and compassion in her work."

The last years of the 1930s proved to be the high point of Dwight's career. In the early 1940s, her work continued to appear in New York group shows, including the Weyhe Gallery (1941, 1942), a collaborative dealers' show at the American Fine Arts Building (1941), and the National Academy of Design (1942), but after 1942 there were practically none. When a group of her lithographs appeared at the t. Louis Art Museum in 1947, a critic noted that they had been printed in the 1930s. Calling them ""saturated with mood" and "pleasing to the eye", the critic praised her ability to portray "comic aspects with gaiety rather than sarcasm" and said the human figures she showed were "solid and carefully built up psychologically as well as physically."

During the 1940s, Dwight made a watercolor called ''Farm House in the Fall'', shown here, Image No. 12. After turning to lithography in 1926, she had continued to make some watercolors and colored drawings. In 1933, a watercolor she called ''Listening In'' was included in the Whitney Museum's first biennial exhibition of contemporary American sculpture, watercolors, and prints. Unlike ''Chess on Deck'' (Image No. 3) and most of her other work, its setting is rural and it contains no human or animal figures. In that respect, it may fall into a category mentioned in her essay on satire, in that it appears to address compositional problems and technical difficulties but not what she called "discrepancies between the real and the ideal". From her earliest efforts onward, most her pictures were full either of human figures or subjects that evoked human emotions and were as one observer said, "probes into the depths of the drama of everyday human life". In them, as another said, Dwight's empathy for her subjects is apparent as well as her droll sense of humor. In a brief biography of Dwight, a curator at the Smithsonian American Art Museum characterized Dwight as "keen observer of the human comedy, which she depicted with humor and compassion in her work."

San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish language, Spanish for "Francis of Assisi, Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the List of Ca ...

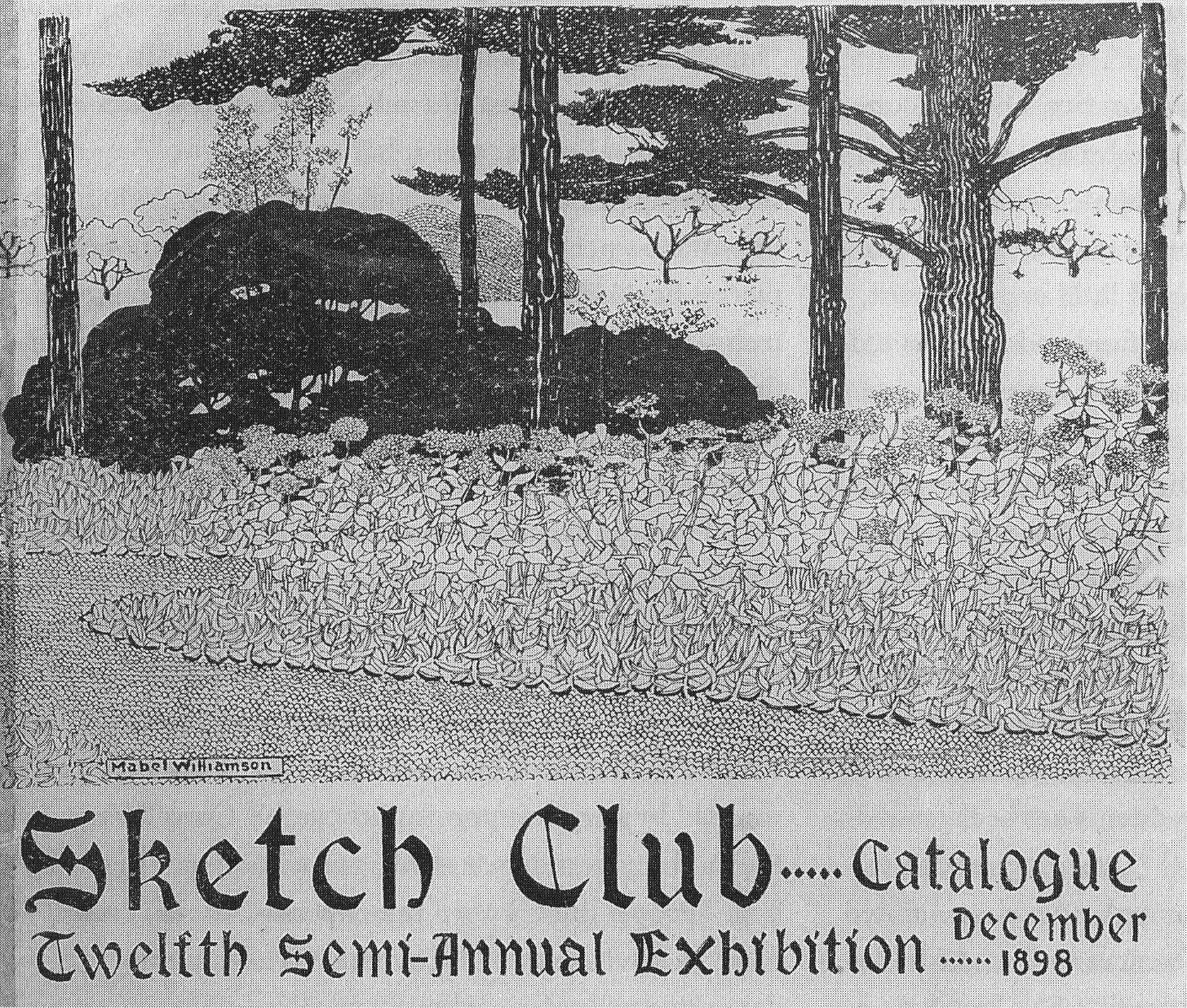

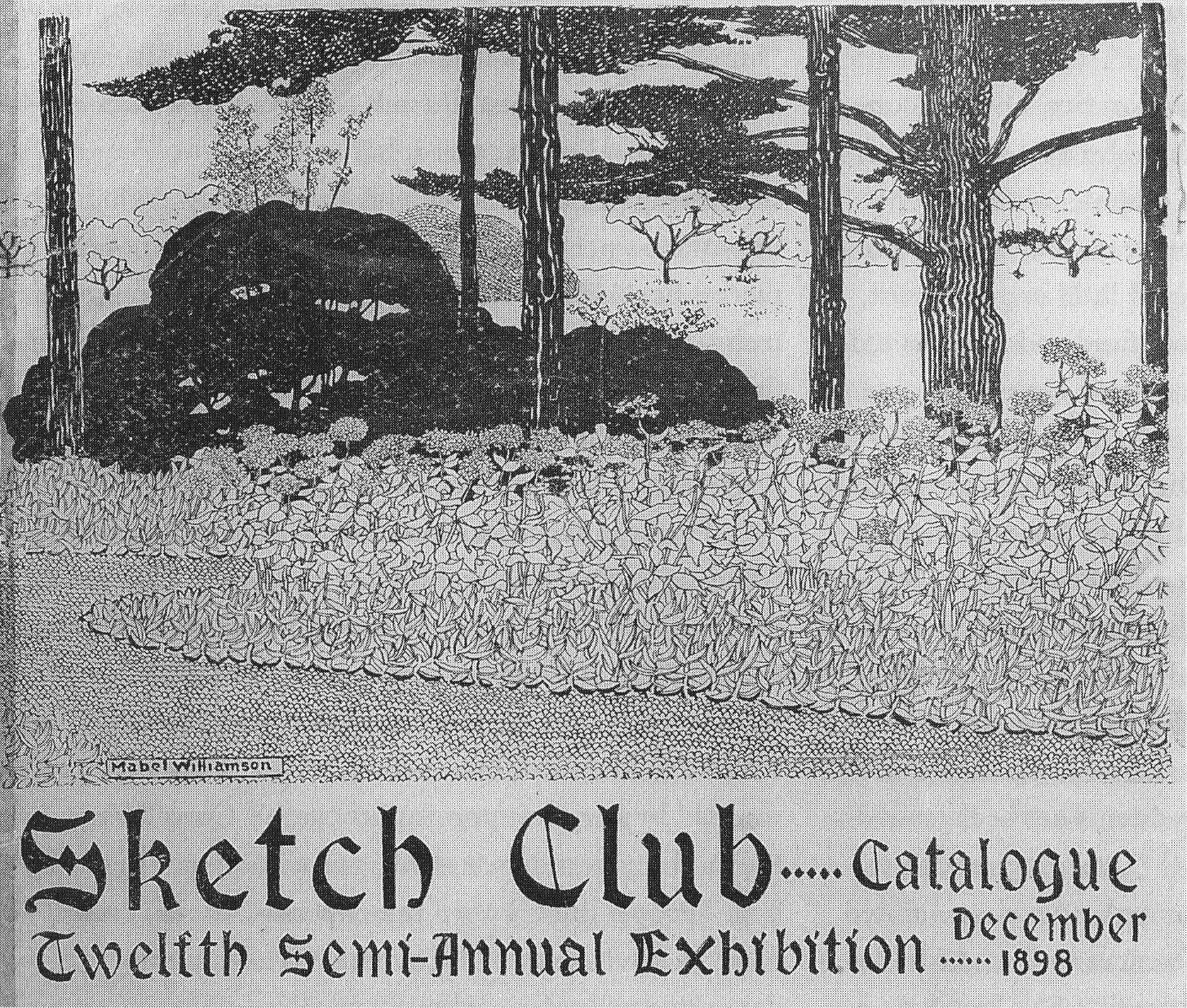

in the late 1880s. There, she studied with Arthur Mathews at the Mark Hopkins Institute. Early in 1899, a critic for a local weekly magazine called ''The Wave'' said her portraits were the best ones in the show, "being handled with a degree of delicacy and feeling characteristic of the true colorist." Later that year, she joined and became a director of the San Francisco Sketch Club. In 1898, she drew the illustration for the cover of the club's exhibition catalog, shown here, Image No. 1. Two years later, she received a commission for a portrait from a monthly review called ''The Critic''. At about the same time, still living with her parents, she moved to Manhattan, and there a publisher commissioned her to make illustrations for a book about animals in the western United States. Her thirteen drawings included a frontispiece of deer, shown here, Image No. 2. A critic called the pictures "delightful", adding that they would appeal to readers old and young.

In her mid-20s she accompanied Helen Bartlett Bridgman, wife of the explorer Herbert Lawrence Bridgman, on a world tour including stops in Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Med ...

, Ceylon

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

, India

India, officially the Republic of India ( Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the ...

, Java

Java (; id, Jawa, ; jv, ꦗꦮ; su, ) is one of the Greater Sunda Islands in Indonesia. It is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the south and the Java Sea to the north. With a population of 151.6 million people, Java is the world's mo ...

, and Great Britain. Returning to the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., federal district, five ma ...

in 1903, she rejoined her parents in Greenwich Village

Greenwich Village ( , , ) is a neighborhood on the west side of Lower Manhattan in New York City, bounded by 14th Street to the north, Broadway to the east, Houston Street to the south, and the Hudson River to the west. Greenwich Village ...

. For the next few years she continued her efforts to establish herself as a professional artist and, from 1903 to 1906, listed herself in the ''American Art Annual'' as a painter and illustrator. She met and in 1906 married fellow artist Eugene Patrick Higgins. Although they were both socialists

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

, and hence espoused equality of the sexes, Dwight fell into the role of helpmate and stopped painting.

Dwight and Higgins had no children. In 1917, they separated and she resumed her painting career. The following year, she joined Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney's newly founded Whitney Studio Club and became secretary to Juliana Force

Juliana R. Force (December 25, 1876August 28, 1948) was an American art museum administrator and director. Force started her career as a collector of folk art and as a secretary to socialite art collectors. She initiated the first display of ...

, the club's director. Over the next few years she attended life drawing sessions and showed at annual exhibitions that the club held. Although she made some experiments with etching, she worked mainly in watercolor at this time. When she showed a painting called ''Nocturne'' at a club exhibition in December 1918, a critic for ''American Art News'' called it a "black picture" that had "a nude female figure of uncommon line and tone." In 1923, she made a watercolor of a subject that would later reappear as one of her best-known lithographs. Showing people at a public aquarium, it was, a critic said, "both amusing and competently handled." The critic praised another of her paintings, called ''Portrait of a Man'', for its "fine characterization" and rich color that "functions definitely in the achievement of form." Reviewing another Whitney Club show, in 1926, a critic for the ''New York Sun'' said "Miss Dwight is a wit and in her paintings of subjects seized in the subway, the parks, and other public places weaves in a lot of insidious criticism of her fellow citizens."

Mature style

Dwight reached the age of 50 in 1925. She met the New York art print dealerCarl Zigrosser

Carl Zigrosser (1891–1975) was an art dealer best known for founding and running the New York Weyhe Gallery in the 1920s and 1930s, and as Curator of Prints and Drawings at the Philadelphia Museum of Art between 1940 and 1963. In the 1910s, h ...

some time before the outbreak of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, and, with his encouragement, traveled to Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. ...

in 1926 to spend a year studying lithographic art in the ''Atelier Duchatel''. While in Paris, she made sketches showing people engaged in everyday activities—watching puppet shows, sitting in cafés, worshiping, browsing stalls by the Seine

The Seine ( , ) is a river in northern France. Its drainage basin is in the Paris Basin (a geological relative lowland) covering most of northern France. It rises at Source-Seine, northwest of Dijon in northeastern France in the Langres plate ...

—and worked up the sketches into lithographic prints. In their posture and gestures as much as their facial expressions, the characters she depicted showed their personalities and individual foibles. A watercolor she called ''Chess on Deck'', shown here, Image No. 3, was probably made either on her outbound or inbound voyage. She made the lithograph called ''Basque Church'', shown here, Image No. 4, while she was abroad. When the Philadelphia Print Club showed Dwight's complete lithographic works in 1929, C.H. Bonte, a critic for the ''Philadelphia Inquirer'', drew attention to prints of French scenes such as this, saying "She is above all interested in people and their characters. Rich is the skill which has been employed in giving individual distinction to all the details of this human comedy, for it is surely comedy as Miss Dwight sees it."

Within a year of her return, the Paris prints and the ones she began to make in New York helped to establish her as one of America's best lithographic artists. In 1928, Zigrosser arranged for her to be given a first solo exhibit. That year, a critic for the ''Brooklyn Daily Eagle'' noted that she had a "flair for the fantastic and romantic and can stir the imagination". The critic added, "Mabel Dwight, whose exhibition is being held at the Weyhe Galleries, has already won considerable reputation for herself in this medium" adding that she was "apt to respond to the humorous aspect of life." In 1929 the Print Club of Philadelphia gave her a solo exhibition including all the prints she had made in Paris, Chartres, and New York through the end of the previous year. In a lengthy review, Margaret Breuning of the ''New York Evening Post'' wrote that the show contained "gay happy lithographs accomplished by a true artist, whose affectionate pulse is nicely attuned to the heart beats of those she so faithfully depicts."

A lithograph made in 1928 called ''Deserted Mansion'' was one of her first prints to attract substantial notice. The ''Brooklyn Daily Eagle'' critic called attention to it and her other "emotional pictures of deserted old houses". A critic for the ''Philadelphia Inquirer'' wrote that she had infused the subject with a "sensed spirit of mystery" and thereby accomplished an "emotional trick of picture making". Dwight later said the place reminded her of Jane Eyre

''Jane Eyre'' ( ; originally published as ''Jane Eyre: An Autobiography'') is a novel by the English writer Charlotte Brontë. It was published under her pen name "Currer Bell" on 19 October 1847 by Smith, Elder & Co. of London. The firs ...

, adding, "The upper windows were not boarded or shuttered, and they looked at one with that insane expression which windows of long empty houses acquire." This print is shown here, Image No. 5.

A lithograph Dwight made in 1929 called ''Ferry Boat'' was chosen by the Institute of Graphic Arts as one of its "Fifty Prints of the Year". In 1931, a critic said it was "highly amusing in its satire." Writing in the ''New York Times'', Edward Alden Jewell

Edward Alden Jewell (March 10, 1888 – October 11, 1947) was an American newspaper and magazine editor, art critic and novelist. He was the New York Times art editor from July 1936 until his death.

Early life

Born in Grand Rapids, Michigan, ...

considered it one of her notable works in 1932 and in 1937 said it was then considered to be "long familiar". A few years later, in a review of four contemporary printmakers, Zigrosser called this lithograph "immortal". In 1930, '' Fortune'' magazine commissioned her to illustrate an article called "To Make a Circus Pay". The illustration she made for the first two pages of the piece are shown here, Image No. 7. When, in 1932, she was given a second solo exhibition at the Weyhe Gallery, she showed watercolors and drawings as well as her prints. The show drew from Edward Alden Jewell an evaluation of her capacity to evoke a range of moods in her work. He wrote that she depicted mansions that had become "solemn ghosts" a along with graveyards and other somber subjects, but also presented "frankly carefree", even "hilarious" works showing circuses and rent parties. Between the extremes, he cited pictures, such as ''Ferry Boat'', that had become "more comfortable" to viewers.

A 1931 lithograph called ''Life Class'', shown here, Image No. 8, drew scant attention at the time but has more recently been analyzed in some detail. In 1952, a critic noticed in it Dwight's ability to personify specific events, employing a "sure and unflattering" touch. In 1990, Christine Temin, writing in the ''Boston Globe'' explained that the picture commemorated the time when women were first allowed to join men in drawing nude models at the Whitney Studio Club. She wrote, "The sheer harmlessness of the scene makes a mockery of the sexist art world." In 2014, an exhibition catalog pointed out that the model looks back at the artists just as they examine her and said the women sketchers in the picture could be seen "as representing the feminist idea of the male gaze." In 1942, Zigrosser compared the picture to a very similar one by Peggy Bacon saying Bacon's was caricature while Dwight's was "drama" and added that Dwight's was "an assemblage of individual studies of characters, which by the logic of situation also acquire a comic aspect."

By 1933, Dwight's reputation was firmly established. Her work had appeared in group exhibitions of the Whitney Studio Club, the Philadelphia Print Club, the Philadelphia Art Alliance and in solo exhibitions at the Weyhe Gallery and Duke University. Her work had been featured in Vanity Fair seven times between November 1928 and September 1930. By 1933, her paintings, drawings, and prints were present in collections of prominent museums including the Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Metropolitan Museum of Art of New York City, colloquially "the Met", is the largest art museum in the Americas. Its permanent collection contains over two million works, divided among 17 curatorial departments. The main building at 100 ...

, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

The Museum of Fine Arts (often abbreviated as MFA Boston or MFA) is an art museum in Boston, Massachusetts. It is the 20th-largest art museum in the world, measured by public gallery area. It contains 8,161 paintings and more than 450,000 works ...

, the Cleveland Museum of Art

The Cleveland Museum of Art (CMA) is an art museum in Cleveland, Ohio, located in the Wade Park District, in the University Circle neighborhood on the city's east side. Internationally renowned for its substantial holdings of Asian and Egypt ...

, the Art Institute of Chicago

The Art Institute of Chicago in Chicago's Grant Park, founded in 1879, is one of the oldest and largest art museums in the world. Recognized for its curatorial efforts and popularity among visitors, the museum hosts approximately 1.5 mil ...

, the Fogg Museum

The Harvard Art Museums are part of Harvard University and comprise three museums: the Fogg Museum (established in 1895), the Busch-Reisinger Museum (established in 1903), and the Arthur M. Sackler Museum (established in 1985), and four research ...

at Harvard University, the Victoria and Albert Museum

The Victoria and Albert Museum (often abbreviated as the V&A) in London is the world's largest museum of applied arts, decorative arts and design, housing a permanent collection of over 2.27 million objects. It was founded in 1852 and ...

, and the Bibliothèque nationale de France

The Bibliothèque nationale de France (, 'National Library of France'; BnF) is the national library of France, located in Paris on two main sites known respectively as ''Richelieu'' and ''François-Mitterrand''. It is the national reposito ...

. Writing in ''Publishers Weekly'', Walter Pach had noted simply that she had been "acclaimed in the past few years". Edward Alden Jewell had called her a "gifted American satirist".

In 1935, she made a portrait that received little or no public notice at the time. Shown here, Image No. 9, it and her self-portrait, shown at top in the info box, illustrate her skill at portraiture. Critics observed this skill first in 1899 and again in 1923, as noted above. In 1997, a critic for the ''New York Times'' pointed to a "classical mode" in her portrait style.

In 1936, she was listed as one of America's best printmakers in ''Prints'' magazine and, in a news article, was said to have "climbed to the top of a difficult and highly competitive field." That year, she made a lithograph called ''Queer Fish'' that received popular and critical acclaim and would eventually become her most popular print. Shown here, Image No. 10, it came from sketches she took at the New York Aquarium

The New York Aquarium is the oldest continually operating aquarium in the United States, located on the Riegelmann Boardwalk in Coney Island, Brooklyn, New York City. It was founded at Castle Garden in Battery Park, Manhattan in 1896, and move ...

in Battery Park

The Battery, formerly known as Battery Park, is a public park located at the southern tip of Manhattan Island in New York City facing New York Harbor. It is bounded by Battery Place on the north, State Street on the east, New York Harbor to ...

. When it was shown two years later, a critic said it was "already famous for its humor." Dwight herself later discussed it in some detail, saying:

It is dark under the balcony and the people are silhouetted black against the lighted tanks. ... People twist themselves into grotesque shapes as they lean on the rather low railing; posteriors loom large and long legs get tangled. One day I saw a huge Grouper fish and a fat man trying to out stare each other; it was a psychological moment. The fish's mouth was open and his telescopic eyes focused intently. The man, startled by the sudden apparition, ... dropped his jaw; ... they hypnotized each other for a moment, then both swam away. Queer Fish!!In 1934, Dwight joined the

Public Works of Art Project

The Public Works of Art Project (PWAP) was a New Deal program designed to employ artists that operated from 1933 to 1934. The program was headed by Edward Bruce, under the United States Treasury Department with funding from the Civil Works Admi ...

. One of her biographers, Carol Kort, reports that despite her professional success, she was at that time in dire financial straits. When that project disbanded, she joined the Federal Art Project

The Federal Art Project (1935–1943) was a New Deal program to fund the visual arts in the United States. Under national director Holger Cahill, it was one of five Federal Project Number One projects sponsored by the Works Progress Administr ...

of the Works Projects Administration and remained a federal employee until 1939. During these five years she continued to be productive turning out prints that, "in the tradition of Honoré Daumier

Honoré-Victorin Daumier (; February 26, 1808February 10, 1879) was a French painter, sculptor, and printmaker, whose many works offer commentary on the social and political life in France, from the Revolution of 1830 to the fall of the second N ...

", as one source says, "combined humor with political commentary." In addition to her financial difficulties, her health declined during these years. She suffered from asthma and became increasingly hard of hearing to the point of deafness.

In 1936, Dwight contributed an essay to a book that the Federal Art Project intended to publish in order to demonstrate the importance and quality of the program and its artists. The government declined to publish at that time, and in 1973 the New York Graphic Society finally brought it to press (''Art for the millions; essays from the 1930s by artists and administrators of the WPA Federal Art Project'', compiled by Francis V. O'Connor, Greenwich, Connecticut). In her essay, Dwight says aesthetic demands conflict with the satiric wish to show "the inevitable defects inherent in life". She names Francisco Goya

Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes (; ; 30 March 174616 April 1828) was a Spanish romantic painter and printmaker. He is considered the most important Spanish artist of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. His paintings, drawings, and e ...

and Honoré Daumier as two of a very few masters who were able to resolve this conflict. Of the social realist

Social realism is the term used for work produced by painters, printmakers, photographers, writers and filmmakers that aims to draw attention to the real socio-political conditions of the working class as a means to critique the power structure ...

art of her time, she writes, "Some of the young, class-conscious artists are too arrogantly vehement in their portrayals of vulgarity, ugliness, injustice, etc., and one is conscious of their agonized effort to twist the whole into a pattern of art. The result leaves the spectator indifferent." She notes that other artists of her time show people who are down and out, urban mean streets, and tawdry amusements without being satirists. "They frankly enjoy painting Coney Island, gasoline stations, hot-dog stands, cheap main streets, frame houses with jig-saw bands-all the Topsy-like growth of our cities." The essay ends with a statement that might apply to her own work. The artist, she says, should keep a "cool head and a warm heart". He or she does not need to exaggerate peoples' foibles since it is impossible to "rival nature, who herself has created beings so out of all reasonable proportion" ut"has only to look at these people with sympathy and translate them into art to be just as tragic or humorous as he may wish."

A decade after her first, Weyhe Gallery gave Dwight a third solo exhibition, this one encompassing some 93 works that, as a ''New York Times'' critic commented, spanned "from Paris scenes of 1927 to the mordant New York comments of succeeding years, to the ''Ferry Boat'' of 1930 and the much-admired ''Queer Fish'' of 1936. Citing her "rich, healthy human commentary", a reviewer wrote, "Wherever masses of people circulate, on the ferryboats and street corners, in the parks and movie houses, Miss Dwight has found seemingly inexhaustible material. Her work is a rich, healthy human commentary. It is full of friendly humor. But the artist does not hide her feelings behind satire. We know where her sympathies lie. It is with the heavily burdened banana men, not the swollen butter-and-egg men."

Of a showing of her Federal Art Project prints in Miami, a critic wrote, echoing Dwight's discussion of satire in art, "When distortion and exaggeration occur in these lithographs they are subtle, mature, and suggestive because they spring from sympathy rather than from arrogance and disdain." The critic added, "As a lithographer Mabel Dwight stands among the best in America, although she only began working in this medium in 1927 when she was past 50."

Later life and work

The last years of the 1930s proved to be the high point of Dwight's career. In the early 1940s, her work continued to appear in New York group shows, including the Weyhe Gallery (1941, 1942), a collaborative dealers' show at the American Fine Arts Building (1941), and the National Academy of Design (1942), but after 1942 there were practically none. When a group of her lithographs appeared at the t. Louis Art Museum in 1947, a critic noted that they had been printed in the 1930s. Calling them ""saturated with mood" and "pleasing to the eye", the critic praised her ability to portray "comic aspects with gaiety rather than sarcasm" and said the human figures she showed were "solid and carefully built up psychologically as well as physically."

During the 1940s, Dwight made a watercolor called ''Farm House in the Fall'', shown here, Image No. 12. After turning to lithography in 1926, she had continued to make some watercolors and colored drawings. In 1933, a watercolor she called ''Listening In'' was included in the Whitney Museum's first biennial exhibition of contemporary American sculpture, watercolors, and prints. Unlike ''Chess on Deck'' (Image No. 3) and most of her other work, its setting is rural and it contains no human or animal figures. In that respect, it may fall into a category mentioned in her essay on satire, in that it appears to address compositional problems and technical difficulties but not what she called "discrepancies between the real and the ideal". From her earliest efforts onward, most her pictures were full either of human figures or subjects that evoked human emotions and were as one observer said, "probes into the depths of the drama of everyday human life". In them, as another said, Dwight's empathy for her subjects is apparent as well as her droll sense of humor. In a brief biography of Dwight, a curator at the Smithsonian American Art Museum characterized Dwight as "keen observer of the human comedy, which she depicted with humor and compassion in her work."

The last years of the 1930s proved to be the high point of Dwight's career. In the early 1940s, her work continued to appear in New York group shows, including the Weyhe Gallery (1941, 1942), a collaborative dealers' show at the American Fine Arts Building (1941), and the National Academy of Design (1942), but after 1942 there were practically none. When a group of her lithographs appeared at the t. Louis Art Museum in 1947, a critic noted that they had been printed in the 1930s. Calling them ""saturated with mood" and "pleasing to the eye", the critic praised her ability to portray "comic aspects with gaiety rather than sarcasm" and said the human figures she showed were "solid and carefully built up psychologically as well as physically."

During the 1940s, Dwight made a watercolor called ''Farm House in the Fall'', shown here, Image No. 12. After turning to lithography in 1926, she had continued to make some watercolors and colored drawings. In 1933, a watercolor she called ''Listening In'' was included in the Whitney Museum's first biennial exhibition of contemporary American sculpture, watercolors, and prints. Unlike ''Chess on Deck'' (Image No. 3) and most of her other work, its setting is rural and it contains no human or animal figures. In that respect, it may fall into a category mentioned in her essay on satire, in that it appears to address compositional problems and technical difficulties but not what she called "discrepancies between the real and the ideal". From her earliest efforts onward, most her pictures were full either of human figures or subjects that evoked human emotions and were as one observer said, "probes into the depths of the drama of everyday human life". In them, as another said, Dwight's empathy for her subjects is apparent as well as her droll sense of humor. In a brief biography of Dwight, a curator at the Smithsonian American Art Museum characterized Dwight as "keen observer of the human comedy, which she depicted with humor and compassion in her work."

Politics

Dwight was a lifelong socialism, socialist whose views were primarily based, as she wrote in her 1936 essay, "Satire in Art", on hatred of the vast distance that separated the poor from the rich in the United States. In 1918, she joined with 49 other like-minded people in a pressure group called "Fifty Friends" that advocated clemency for men who were imprisoned for declaring themselves to be conscientious objectors during World War I. Living in Manhattan during the 1930s, she joined one of the Marxist John Reed Clubs and supported anotherPopular Front

A popular front is "any coalition of working-class and middle-class parties", including liberal and social democratic ones, "united for the defense of democratic forms" against "a presumed Fascist assault".

More generally, it is "a coalitio ...

organization, the American Artists' Congress

The American Artists' Congress (AAC) was an organization founded in February 1936 as part of the popular front of the Communist Party USA as a vehicle for uniting graphic artists in projects helping to combat the spread of fascism. During Worl ...

. Nonetheless, not wishing to become a propagandist and fearing she would lose sales that she needed to support her precarious existence, she rarely produced works of an overtly political character.

Family and personal life

Dwight was born on January 31, 1875, and named Mabel Jacque Williamson. She was the only child of Paul Huston Williamson (1837–sometime after 1910) and his wife Adelaide (or Ada) Jacque (born 1875). Paul Williamson owned a farm near Cincinnati in Colerain Township, Hamilton County, Ohio. While Dwight was still a child, the family moved toNew Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Carrollton, outside the city. In 1893, the Williamsons moved to

San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish language, Spanish for "Francis of Assisi, Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the List of Ca ...

where Dwight was privately tutored while attending high school. In the mid-1890s, Dwight completed her secondary education and, as noted above, began studies under Arthur Mathews at the Mark Hopkins Institute.

Before she separated from Higgins, Dwight's friend Carl Zigrosser introduced her to an architectural draftsman named Roderick Seidenberg. He was a conscientious objector and militant socialist fourteen years younger than her. Their relationship grew close and for some years they lived together. It ended in 1929 when he took a job in the Soviet Union and, on returning, fell in love with, and then married another woman. Dwight and Seidenberg became reconciled when Dwight suffered periods of illness during the 1930s and 1940s and Seidenberg and his wife Catherine took Dwight into their home to care for her.

Following her divorce from Higgins, she neither kept her married nor resumed her maiden name, but rather, for reasons she did not disclose, chose the surname Dwight. Her reticence about her name was not unusual in her. Even though she wrote an (unpublished) autobiography, much about her life is unknown. Her hearing loss is an example. Some biographic summaries do not mention a hearing disability. Some say she was deaf, but do not specify the degree of hearing loss. One source says she was nearly deaf and another says she was profoundly so.

In 1929 or 1930 she traveled to New Mexico and this appears to have been the first and only time she traveled outside the Mid-Atlantic states after her return from Paris. At about this time she moved from Greenwich Village to Staten Island

Staten Island ( ) is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Richmond County, in the U.S. state of New York. Located in the city's southwest portion, the borough is separated from New Jersey by the Arthur Kill and the Kill Van Kull an ...

and some time later moved to Pipersville, Pennsylvania

Pipersville is an unincorporated community in Bedminster and Plumstead Townships in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, United States. Pipersville is located at the intersection of Pennsylvania State Routes 413 and 611

__NOTOC__

Year 611 (Roman nu ...

. After Dwight turned 65 in 1940, her deafness, chronic asthma

Asthma is a long-term inflammatory disease of the airways of the lungs. It is characterized by variable and recurring symptoms, reversible airflow obstruction, and easily triggered bronchospasms. Symptoms include episodes of wheezing, c ...

, and poverty worsened. Although she continued to work, her output dwindled, and she was confined to nursing homes in the period before her death following a stroke in 1955.

Further reading

______________. ''A Century of Self-Expression: Modern American Art in The Collection of John and Joanne Payson'' (Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania, Bryn Mawr College, 2014) Dwight, Mabel, "Satire in Art," in ''Art for the Millions; Essays From the 1930s by Artists and Administrators of the WPA Federal Art Project'', edited byFrancis V. O'Connor

Francis Valentine O'Connor (February 14, 1937November 20, 2017) was an American art historian who was pioneering scholar of the visual art of the New Deal and an expert on the contemporary artist Jackson Pollock.

Life

O'Connor was born Brooklyn ...

(Boston, New York Graphic Society, 1975, pp. 151–154)

Henkes, Robert. ''American Women Painters of the 1930s and 1940s; The Lives and Work of Ten Artists'' (Jefferson, North Carolina, McFarland, 1991)

Kort, Carol, and Liz Sonneborn. ''A to Z of American Women in the Visual Arts'' (New York, Facts on File, 2002)

Robinson, Susan Barnes, and John Pirog. ''Mabel Dwight: A Catalogue Raisonné of the Lithographs'' (Washington, D.C., Smithsonian Institution Press, 1997)

Zigrosser, Carl. "Mabel Dwight: Master of Comédie Humaine" (''Artnews'', Vol. 6, No. 126, June 1949, pp. 42–45)

ibid. ''The Artist in America; Twenty-Four Close-Ups of Contemporary Printmakers'' (New York, A.A. Knopf, 1942)

Notes

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Dwight, Mabel 1875 births 1955 deaths Artists from New York City Artists from San Francisco 20th-century American artists Modern artists 20th-century American women artists American women printmakers Federal Art Project artists 20th-century American printmakers American lithographers 20th-century lithographers Women lithographers American expatriates in France