MV Empire Windrush on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

HMT ''Empire Windrush'' was a

Windrush had a set of four

Windrush had a set of four

At 0623 hrs the Radio Officer broadcast the first

At 0623 hrs the Radio Officer broadcast the first

About 26 hours after ''Empire Windrush'' was abandoned, of the

About 26 hours after ''Empire Windrush'' was abandoned, of the

In October 1954, one of the military personnel on ''Empire Windrush'' during her final voyage was awarded the

In October 1954, one of the military personnel on ''Empire Windrush'' during her final voyage was awarded the

passenger

A passenger is a person who travels in a vehicle, but does not bear any responsibility for the tasks required for that vehicle to arrive at its destination or otherwise operate the vehicle, and is not a steward. The vehicles may be bicycles, ...

motor ship

A motor ship or motor vessel is a ship propelled by an internal combustion engine, usually a diesel engine. The names of motor ships are often prefixed with MS, M/S, MV or M/V.

Engines for motorships were developed during the 1890s, and by th ...

that was launched in Germany in 1930 as the MV ''Monte Rosa''. She was built as an ocean liner

An ocean liner is a type of passenger ship primarily used for transportation across seas or oceans. Ocean liners may also carry cargo or mail, and may sometimes be used for other purposes (such as for pleasure cruises or as hospital ships). The ...

for the German shipping company Hamburg Süd

Hamburg Südamerikanische Dampfschifffahrts-Gesellschaft A/S & Co KG, widely known as Hamburg Süd, was a German container shipping company. Founded in 1871, Hamburg Süd was among the market leaders in the North–South trade. It also served a ...

. They used the ship to carry German emigrants to South America, and as a cruise ship

Cruise ships are large passenger ships used mainly for vacationing. Unlike ocean liners, which are used for transport, cruise ships typically embark on round-trip voyages to various ports of call, where passengers may go on Tourism, tours k ...

. During World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, she was taken over by the German navy

The German Navy (, ) is part of the unified (Federal Defense), the German Armed Forces. The German Navy was originally known as the ''Bundesmarine'' (Federal Navy) from 1956 to 1995, when ''Deutsche Marine'' (German Navy) became the official ...

and used as a troopship

A troopship (also troop ship or troop transport or trooper) is a ship used to carry soldiers, either in peacetime or wartime. Troopships were often drafted from commercial shipping fleets, and were unable to land troops directly on shore, typic ...

. During the war, she survived two Allied

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not an explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are calle ...

attempts to sink her.

After World War II, the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

seized the ship as a prize of war

A prize of war (also called spoils of war, bounty or booty) is a piece of enemy property or land seized by a belligerent party during or after a war or battle. This term was used nearly exclusively in terms of captured ships during the 18th and 1 ...

and renamed her HMT ''Empire Windrush''. She remained in British service as a troopship until 1954.

In 1948, ''Empire Windrush'' arrived at the Port of Tilbury

The Port of Tilbury is a port located on the River Thames at Tilbury in Essex, England. It serves as the principal port for London, as well as being the main United Kingdom port for handling the importation of paper. There are extensive facili ...

coast near London, carrying 1,027 passengers and two stowaway

A stowaway or clandestine traveller is a person who secretly boards a vehicle, such as a ship, an aircraft, a train, cargo truck or bus.

Sometimes, the purpose is to get from one place to another without paying for transportation. In other c ...

s who embarked at Trinidad

Trinidad is the larger, more populous island of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago, the country. The island lies off the northeastern coast of Venezuela and sits on the continental shelf of South America. It is the southernmost island in ...

, Jamaica

Jamaica is an island country in the Caribbean Sea and the West Indies. At , it is the third-largest island—after Cuba and Hispaniola—of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean. Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, west of Hispaniola (the is ...

, Mexico

Mexico, officially the United Mexican States, is a country in North America. It is the northernmost country in Latin America, and borders the United States to the north, and Guatemala and Belize to the southeast; while having maritime boundar ...

and Bermuda

Bermuda is a British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean. The closest land outside the territory is in the American state of North Carolina, about to the west-northwest.

Bermuda is an ...

. While the passengers included people from many parts of the world, the great majority were West Indian

A West Indian is a native or inhabitant of the West Indies (the Antilles and the Lucayan Archipelago). According to the ''Oxford English Dictionary'' (''OED''), the term ''West Indian'' in 1597 described the indigenous inhabitants of the West In ...

.

''Empire Windrush'' was not the first ship to carry a large group of West Indian people to the United Kingdom, as two other ships (the SS ''Ormonde'' and the SS ''Almanzora'') had arrived the previous year. But her 1948 voyage became very well-known and a symbol of post-war migration to Britain. British Caribbean people

British African-Caribbean people or British Afro-Caribbean people are an ethnic group in the United Kingdom. They are British citizens or residents of recent Caribbean heritage who further trace much of their ancestry to West and Central Africa. ...

who came to the United Kingdom in the period after World War II, including those who came on other ships, are often referred to as the Windrush generation

British African-Caribbean people or British Afro-Caribbean people are an ethnic group in the United Kingdom. They are British citizens or residents of recent Caribbean heritage who further trace much of their ancestry to West and Central Africa. ...

.

On 28 March 1954, while in the western Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern Eur ...

, an explosion and fire in the engine room killed four people. The fire could not be controlled and the ship was abandoned; the other 1494 passengers and crew were all rescued. The empty ship remained afloat and on-fire for nearly two days, eventually sinking during an attempt to salvage her.

Background and description

''Monte Rosa'', was the last of five almost identical s that were built between 1924 and 1931 byBlohm & Voss

Blohm+Voss (B+V), also written historically as Blohm & Voss, Blohm und Voß etc., is a German shipbuilding and engineering company. Founded in Hamburg in 1877 to specialise in steel-hulled ships, its most famous product was the World War II battle ...

in Hamburg

Hamburg (, ; ), officially the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg,. is the List of cities in Germany by population, second-largest city in Germany after Berlin and List of cities in the European Union by population within city limits, 7th-lar ...

for (Hamburg South American Steam Shipping Company).

In the 1920s Hamburg Süd believed there would be a lucrative business in carrying German emigrants to South America. (See "German Argentines

German Argentines (, ) are Argentine people, Argentines of German ancestry as well as German citizens living in Argentina.

They are descendants of Germans who immigrated to Argentina from Germany and most notably from other places in Europe ...

".) The first two ships, ''Monte Sarmiento'' and ''Monte Olivia'', were built for that trade with single-class passenger accommodation of 1,150 passengers in cabins, and 1,350 in dormitories. However, the number of emigrants was less than expected so the two ships were repurposed as cruise ship

Cruise ships are large passenger ships used mainly for vacationing. Unlike ocean liners, which are used for transport, cruise ships typically embark on round-trip voyages to various ports of call, where passengers may go on Tourism, tours k ...

s, operating in Northern European waters, the Mediterranean and around South America. This venture became a great success.

Until the 1920s, cruise holidays had been the preserve of the very wealthy. But by providing modestly-priced cruises, Hamburg Süd could profitably attract a large new clientele. The company commissioned another ship, , to meet the increased demand. But she sank after only two years' service when she struck an uncharted rock in the Beagle Channel

Beagle Channel (; Yahgan language, Yahgan: ''Onašaga'') is a strait in the Tierra del Fuego, Tierra del Fuego Archipelago, on the extreme southern tip of South America between Chile and Argentina. The channel separates the larger main island of I ...

. Hamburg Süd then ordered two more ships: and ''Monte Rosa''.

''Monte Rosa''s registered length was , her beam

Beam may refer to:

Streams of particles or energy

*Light beam, or beam of light, a directional projection of light energy

**Laser beam

*Radio beam

*Particle beam, a stream of charged or neutral particles

**Charged particle beam, a spatially lo ...

was , her depth was , and her draught was . Her tonnage

Tonnage is a measure of the capacity of a ship, and is commonly used to assess fees on commercial shipping. The term derives from the taxation paid on '' tuns'' or casks of wine. In modern maritime usage, "tonnage" specifically refers to a cal ...

s were and .

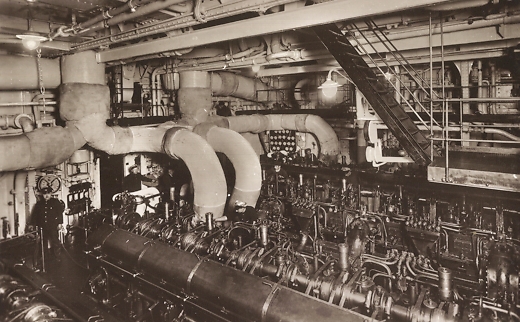

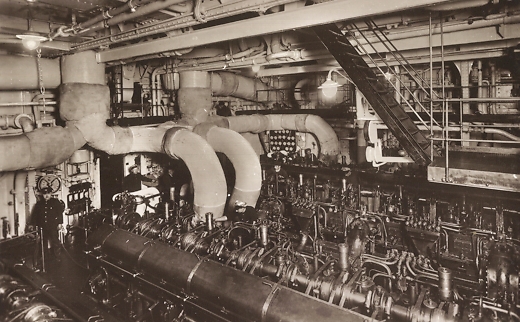

Engines and machinery

All five ''Monte''-class ships were motor ships. The first two to be launched, ''Monte Sarmiento'' and ''Monte Olivia'', were the first large Diesel-powered passenger ships to serve with a German operator. The use of diesel engines drew on the experience Blohm & Voss had gained by building diesel-poweredU-boat

U-boats are Submarine#Military, naval submarines operated by Germany, including during the World War I, First and Second World Wars. The term is an Anglicization#Loanwords, anglicized form of the German word , a shortening of (), though the G ...

s in World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

.

Windrush had a set of four

Windrush had a set of four four-stroke

A four-stroke (also four-cycle) engine is an internal combustion (IC) engine in which the piston completes four separate strokes while turning the crankshaft. A stroke refers to the full travel of the piston along the cylinder, in either directio ...

, six-cylinder, single-acting MAN

A man is an adult male human. Before adulthood, a male child or adolescent is referred to as a boy.

Like most other male mammals, a man's genome usually inherits an X chromosome from the mother and a Y chromosome from the f ...

Diesel engines. She had two screw propeller

A propeller (often called a screw if on a ship or an airscrew if on an aircraft) is a device with a rotating hub and radiating blades that are set at a pitch to form a helical spiral which, when rotated, exerts linear thrust upon a working flu ...

s, each of which was driven by one pair of engines via single-reduction gearing. Her engines' combined output was rated at , and gave her a speed of . This was slower than Hamburg Süd's flagship , but more economical for the emigrant trade, and for pleasure cruises.

Electric power was supplied by a set of DC electric generator

In electricity generation, a generator, also called an ''electric generator'', ''electrical generator'', and ''electromagnetic generator'' is an electromechanical device that converts mechanical energy to electrical energy for use in an externa ...

s, powered by internal combustion engines in the engine room. As built, ''Monte Rosa'' had three 350 kW generators. A fourth generator was added in 1949. She had also an emergency generator outside the engine room. The ship also carried two Scotch marine boiler

A "Scotch" marine boiler (or simply Scotch boiler) is a design of steam boiler best known for its use on ships.

The general layout is that of a short horizontal cylinder. One or more large cylindrical furnaces are in the lower part of the boiler ...

s to produce high-pressure steam for some auxiliary machinery. These could be heated either by burning diesel fuel, or by using the hot exhaust gases from her main engines.

Naming and registration

The ''Monte''-class ships were named after mountains in Europe or South America. ''Monte Rosa'' was named afterMonte Rosa

Monte Rosa (; ; ; or ; ) is a mountain massif in the eastern part of the Pennine Alps, on the border between Italy (Piedmont and Aosta Valley) and Switzerland (Valais). The highest peak of the massif, amongst several peaks of over , is the D ...

, which is a mountain massif

A massif () is a principal mountain mass, such as a compact portion of a mountain range, containing one or more summits (e.g. France's Massif Central). In mountaineering literature, ''massif'' is frequently used to denote the main mass of an ...

on the Swiss-Italian border, and is the second-highest mountain in the Alps. Hamburg Süd registered

Registered may refer to:

* Registered mail, letters, packets or other postal documents considered valuable and in need of a chain of custody

* Registered trademark symbol, symbol ® that provides notice that the preceding is a trademark or service ...

her at Hamburg. Her German official number was 1640, and her code letters

Code letters or ship's call sign (or callsign) Mtide Taurus - IMO 7626853"> SHIPSPOTTING.COM >> Mtide Taurus - IMO 7626853/ref> were a method of identifying ships before the introduction of modern navigation aids. Later, with the introduction of ...

were RHWF. By 1934 her call sign

In broadcasting and radio communications, a call sign (also known as a call name or call letters—and historically as a call signal—or abbreviated as a call) is a unique identifier for a transmitter station. A call sign can be formally as ...

was DIDU, and this had superseded her code letters.

Under UK ownership she became one of about 1,300 Empire ship

An Empire ship is a merchant ship that was given a name beginning with "Empire" in the service of the Government of the United Kingdom during and after World War II. Most were used by the Ministry of War Transport (MoWT), which owned them and c ...

s. About 60 Empire ships were named after British rivers.Adur, Arun, Blackwater

Blackwater or Black Water may refer to:

Health and ecology

* Blackwater (coal), liquid waste from coal preparation

* Black water (drink), a health drink

* Blackwater (waste), wastewater containing feces, urine, and flushwater from flush toilets

* ...

, Bure, Calder, Chelmer, Cherwell, Clyde, Colne

Colne () is a market town and civil parishes in England, civil parish in the Borough of Pendle in Lancashire, England. The town is northeast of Nelson, Lancashire, Nelson, northeast of Burnley and east of Preston, Lancashire, Preston.

The ...

, Crouch, Dart

Dart or DART may refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media

* Dart, the equipment in the game of darts

* Dart (comics), an Image Comics superhero

* Dart, a character from ''G.I. Joe''

* Dart, a ''Thomas & Friends'' railway engine character

* Dart ...

, Dee, Derwent, Don

Don, don or DON and variants may refer to:

Places

*Don (river), a river in European Russia

*Don River (disambiguation), several other rivers with the name

* Don, Benin, a town in Benin

* Don, Dang, a village and hill station in Dang district, Gu ...

, Dovey, Evenlode

Evenlode is a village and civil parish (ONS Code 23UC051) in the Cotswold District of eastern Gloucestershire in England.

Evenlode is bordered by the Gloucestershire parishes of Moreton-in-Marsh to the northwest, Longborough and Donnington t ...

, Exe, Fal, Frome, Hamble, Humber, Kennet, Lune, Nene, Nidd, Orwell, Ouse, Otter, Ribble, Roden, Roding, Rother, Severn, Soar, Spey, Stour, Swale, Taff, Tamar, Taw, Tern, Teviot, Thames, Torridge, Trent, Tweed, Tyne, Usk, Wandle, Wansbeck, Waveney, Weaver, Welland, Wensum, Wey, Wharfe, Windrush, Witham, Wye, Yare. Her namesake, the River Windrush

The River Windrush is a tributary of the River Thames in central England. It rises near Snowshill in Gloucestershire and flows south east for via Burford and Witney to meet the Thames at Newbridge, River Thames, Newbridge in Oxfordshire.

The ri ...

, rises in the Cotswolds

The Cotswolds ( ) is a region of central South West England, along a range of rolling hills that rise from the meadows of the upper River Thames to an escarpment above the Severn Valley and the Vale of Evesham. The area is defined by the bedroc ...

, and joins the River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the The Isis, River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the Longest rivers of the United Kingdom, s ...

a few miles upstream of Oxford

Oxford () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and non-metropolitan district in Oxfordshire, England, of which it is the county town.

The city is home to the University of Oxford, the List of oldest universities in continuou ...

. The Ministry of Transport registered her at London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

. Her UK official number was 181561, and her call sign was GYSF.

In UK service, her name had the prefix "HMT" which could stand for "His Majesty's Troopship", "His Majesty's Transport" or "Hired Military Transport".Royal Navy armed trawlers also used the prefix HMT, in this case meaning "His/Her Majesty's Trawler". Some official documents, including the enquiry report into the ship's loss, use "MV" (which stands for Motor Vessel

A motor ship or motor vessel is a ship Marine propulsion, propelled by an internal combustion engine, usually a diesel engine. The names of motor ships are often Ship prefix, prefixed with MS, M/S, MV or M/V.

Engines for motorships were develo ...

), instead of "HMT".

German merchant service

Blohm & Voss launched ''Monte Rosa'' on 13 December 1930. Early in 1931 she made hersea trial

A sea trial or trial trip is the testing phase of a watercraft (including boats, ships, and submarines). It is also referred to as a "shakedown cruise" by many naval personnel. It is usually the last phase of construction and takes place on op ...

s and was delivered to Hamburg Süd. Her maiden voyage was from Hamburg to Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires, controlled by the government of the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires, is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Argentina. It is located on the southwest of the Río de la Plata. Buenos Aires is classified as an Alpha− glob ...

. She left Hamburg on 28 March 1931, and got back on 22 June. For the remainder of 1931, all four ''Monte'' sisters were scheduled to sail between Hamburg and Buenos Aires. They were scheduled to call at A Coruña

A Coruña (; ; also informally called just Coruña; historical English: Corunna or The Groyne) is a city and municipality in Galicia, Spain. It is Galicia's second largest city, behind Vigo. The city is the provincial capital of the province ...

and Vigo

Vigo (, ; ) is a city and Municipalities in Spain, municipality in the province of province of Pontevedra, Pontevedra, within the Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Galicia (Spain), Galicia, Spain. Located in the northwest ...

on outward voyages only; and to call at Las Palmas

Las Palmas (, ; ), officially Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, is a Spanish city and capital of Gran Canaria, in the Canary Islands, in the Atlantic Ocean.

It is the capital city of the Canary Islands (jointly with Santa Cruz de Tenerife) and the m ...

, Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro, or simply Rio, is the capital of the Rio de Janeiro (state), state of Rio de Janeiro. It is the List of cities in Brazil by population, second-most-populous city in Brazil (after São Paulo) and the Largest cities in the America ...

, Santos

Santos may refer to:

People

*Santos (surname)

* Santos Balmori Picazo (1899–1992), Spanish-Mexican painter

* Santos Benavides (1823–1891), Confederate general in the American Civil War

Places

*Santos, São Paulo, a municipality in São Paulo ...

, São Francisco do Sul

São Francisco do Sul is a municipality in the Brazilian state of Santa Catarina. It covers an area of 540 km2 (208 miles2) and had an estimated population of 53,746 in 2020.

Location

It was founded as a village by the Portuguese in 1658. ...

, Rio Grande

The Rio Grande ( or ) in the United States or the Río Bravo (del Norte) in Mexico (), also known as Tó Ba'áadi in Navajo language, Navajo, is one of the principal rivers (along with the Colorado River) in the Southwestern United States a ...

, and Montevideo

Montevideo (, ; ) is the capital city, capital and List of cities in Uruguay, largest city of Uruguay. According to the 2023 census, the city proper has a population of 1,302,954 (about 37.2% of the country's total population) in an area of . M ...

in both directions.

''Monte Rosa'' entered service just as the Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

was causing a global slump in shipping, including Hamburg Süd's passenger business. In 1933 trade began to recover, so Hamburg Süd returned the older ships, ''Monte Sarmiento'' and ''Monte Olivia'', to their original role of taking emigrants to South America; and put ''Monte Pascoal'' and ''Monte Rosa'' mainly on cruises to Norway and the UK. By 1935 ''Monte Rosa'' was back on her route between Hamburg and Buenos Aires. She made more than 20 round trips on the route before the outbreak of World War II.

After coming to power in Germany in 1933, the Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party ( or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported the ideology of Nazism. Its precursor ...

used ships including ''Monte Rosa'' to further its ideology. In 1937 the Nazi government chartered ''Monte Olivia'', ''Monte Rosa'', and ''Monte Sarmiento'' to provide cruise holidays for the state-owned ("Strength through Joy") programme. This provided concerts, lectures, sports activities and cheap holidays as a means of strengthening support for the Nazi regime and indoctrinating people in its ideology. The cruises ranged from eight to 20 days in duration. One route went north from Hamburg, along the Norwegian coast and travelling as far as Svalbard

Svalbard ( , ), previously known as Spitsbergen or Spitzbergen, is a Norway, Norwegian archipelago that lies at the convergence of the Arctic Ocean with the Atlantic Ocean. North of continental Europe, mainland Europe, it lies about midway be ...

. Another was through the Mediterranean, stopping in Italy and Libya, and travelling as far east as Port Said

Port Said ( , , ) is a port city that lies in the northeast Egypt extending about along the coast of the Mediterranean Sea, straddling the west bank of the northern mouth of the Suez Canal. The city is the capital city, capital of the Port S ...

. Each voyage included a number of undercover Gestapo

The (, ), Syllabic abbreviation, abbreviated Gestapo (), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of F ...

officers, tasked with spying on the passengers.

When visiting South America, the ship was used to spread Nazi ideology among the German-speaking community there. When in port in Argentina, she hosted Nazi rallies for German Argentines

German Argentines (, ) are Argentine people, Argentines of German ancestry as well as German citizens living in Argentina.

They are descendants of Germans who immigrated to Argentina from Germany and most notably from other places in Europe ...

. In 1933, the new German ambassador, Baron , sailed to Argentina aboard ''Monte Rosa''. He disembarked wearing an SS uniform in front of an enthusiastic crowd. He spent his time in office promoting Nazi ideology. The ship was also a venue for Nazi gatherings when docked in London.

On 23 July 1934 ''Monte Rosa'' ran aground off Thorshavn in the Faroe Islands

The Faroe Islands ( ) (alt. the Faroes) are an archipelago in the North Atlantic Ocean and an autonomous territory of the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark. Located between Iceland, Norway, and the United Kingdom, the islands have a populat ...

. She was refloated the next day. In 1936 she rendezvoused at sea with the airship , and a bottle of Champagne was hoisted from her deck to the airship.

World War II service

When World War II began, ''Monte Rosa'' was in Hamburg. From 11 January 1940 she was abarracks ship

A barracks ship or barracks barge or berthing barge, or in civilian use accommodation vessel or accommodation ship, is a ship or a non-self-propelled barge containing a superstructure of a type suitable for use as a temporary barracks for sai ...

at Stettin (now Szczecin

Szczecin ( , , ; ; ; or ) is the capital city, capital and largest city of the West Pomeranian Voivodeship in northwestern Poland. Located near the Baltic Sea and the Poland-Germany border, German border, it is a major port, seaport, the la ...

), and in April 1940 she was a troopship for the invasion of Norway Invasion of Norway may refer to:

*1033 invasion by Tryggvi the Pretender

*1567 Swedish invasion during the Northern Seven Years' War

*1658 Swedish invasion during the Second Northern War

*1716 Swedish invasion during the Great Northern War

*1808 S ...

, mainly sailing to Oslo

Oslo ( or ; ) is the capital and most populous city of Norway. It constitutes both a county and a municipality. The municipality of Oslo had a population of in 2022, while the city's greater urban area had a population of 1,064,235 in 2022 ...

.

She was one of two ships used in 1942 to deport Norwegian Jews. She made two trips from Oslo to Denmark on 19 and 26 November, carrying a total of 46 people, including the Polish-Norwegian businessman and humanitarian Moritz Rabinowitz

Moritz Moses Rabinowitz (20 September 1887 – 27 February 1942) was a retail merchant based in the city of Haugesund, Norway. Rabinowitz was active in the Jewish community in Norway and was an early opponent of Nazism. After Nazi Germany invade ...

. All but two were murdered at Auschwitz concentration camp

Auschwitz, or Oświęcim, was a complex of over 40 Nazi concentration camps, concentration and extermination camps operated by Nazi Germany in Polish areas annexed by Nazi Germany, occupied Poland (in a portion annexed into Germany in 1939) d ...

. In September 1943 she was to be used for the deportation of Danish Jews. The German chief of sea transport at Aarhus

Aarhus (, , ; officially spelled Århus from 1948 until 1 January 2011) is the second-largest city in Denmark and the seat of Aarhus municipality, Aarhus Municipality. It is located on the eastern shore of Jutland in the Kattegat sea and app ...

in Denmark, together with ''Monte Rosa''s captain, , conspired to prevent this by falsely reporting serious engine trouble to the German High Command. This action may have helped the rescue of the Danish Jews

The Danish resistance movement, with the assistance of many Danish citizens, managed to evacuate 7,500 of Denmark's 8,000 Jews, plus 686 non-Jewish spouses, by sea to nearby Sweden during World War II, neutral Sweden during the Second World War. ...

.

In September 1943, Royal Navy s in Operation Source

Operation Source was a series of attacks to neutralise the heavy German warships – ''Tirpitz'', ''Scharnhorst'', and ''Lützow'' – based in northern Norway, using X-class midget submarines.

The attacks took place in September 1943 at K� ...

badly damaged the battleship

A battleship is a large, heavily naval armour, armored warship with a main battery consisting of large naval gun, guns, designed to serve as a capital ship. From their advent in the late 1880s, battleships were among the largest and most form ...

in Altafjord in Norway. Germany was unwilling to risk moving the ship to a German dockyard for repair, so in October ''Monte Rosa'' was used to take hundreds of civilian workers and engineers to Altafjord, where they repaired ''Tirpitz'' in situ. ''Monte Rosa'' was docked alongside ''Tirpitz'' as an accommodation ship for the workers, and as a repair ship

A repair ship is a naval auxiliary ship designed to provide maintenance support to warships. Repair ships provide similar services to destroyer, submarine and seaplane tenders or depot ships, but may offer a broader range of repair capability incl ...

.

Air attack

During the winter of 1943–1944, ''Monte Rosa'' continued to sail between Norway and Germany. On 30 March 1944, British and CanadianBristol Beaufighter

The Bristol Type 156 Beaufighter (often called the Beau) is a British multi-role aircraft developed during the Second World War by the Bristol Aeroplane Company. It was originally conceived as a heavy fighter variant of the Bristol Beaufor ...

s attacked her. The strike was planned to sink her, after a reconnaissance aircraft of 333 (Norwegian) Squadron had tracked her movements. The ship was sailing south, escorted by two flak ships

''Vorpostenboot'' (plural ''Vorpostenboote''), also referred to as VP-Boats, flakships or outpost boats, were German patrol boats which served during both World Wars. They were used around coastal areas and in coastal operations, and were tasked w ...

; a destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, maneuverable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy, or carrier battle group and defend them against a wide range of general threats. They were conceived i ...

; and German fighter aircraft. The attacking force comprised nine aircraft of Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the Air force, air and space force of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies. It was formed towards the end of the World War I, First World War on 1 April 1918, on the merger of t ...

(RAF) 144 Squadron, five of which carried torpedoes; and nine aircraft of Royal Canadian Air Force

The Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF; ) is the air and space force of Canada. Its role is to "provide the Canadian Forces with relevant, responsive and effective airpower". The RCAF is one of three environmental commands within the unified Can ...

(RCAF) 404 Squadron

4 (four) is a number, numeral and digit. It is the natural number following 3 and preceding 5. It is a square number, the smallest semiprime and composite number, and is considered unlucky in many East Asian cultures.

Evolution of the Hi ...

, all armed with armour-piercing RP-3 rockets.

The attack was near the Norwegian island of Utsira

Utsira () is the least populous municipality in Norway. The island municipality is located in northwestern Rogaland county, just off the western coast of Norway. Utsira is part of the traditional district of Haugaland.

The municipality consist ...

. The RCAF and RAF crews claimed two torpedo hits on ''Monte Rosa''. Cannon fire and eight rockets also hit her. One German Messerschmitt Bf 110

The Messerschmitt Bf 110, often known unofficially as the Me 110,Because it was built before ''Bayerische Flugzeugwerke'' became Messerschmitt AG in July 1938, the Bf 110 was never officially given the designation Me 110. is a twin-engined (de ...

fighter was shot down, and 404 Squadron lost two Beaufighters. The two crew of one aircraft were killed; the crew of the other (one of whom was the squadron commanding officer) survived and were made prisoners of war. Despite her damage, ''Monte Rosa'' reached Aarhus

Aarhus (, , ; officially spelled Århus from 1948 until 1 January 2011) is the second-largest city in Denmark and the seat of Aarhus municipality, Aarhus Municipality. It is located on the eastern shore of Jutland in the Kattegat sea and app ...

in Denmark on 3 April.

Sabotage attack

In June 1944,Max Manus

Maximo Guillermo Manus DSO, MC & Bar (9 December 1914 – 20 September 1996) was a Norwegian resistance fighter during World War II, specialising in sabotage in occupied Norway. After the war he wrote several books about his adventures and ...

and Gregers Gram

Gregers Winther Wulfsberg Gram (15 December 1917 – 13 November 1944) was a Norwegian resistance fighter and saboteur. A corporal and later second lieutenant in the Norwegian Independent Company 1 () during the Second World War, he was kil ...

, members of Norwegian Independent Company 1

Norwegian Independent Company 1 (NOR.I.C.1, pronounced ''Norisén'' (approx. "noor-ee-sehn") in Norwegian) was a British Special Operations Executive (SOE) group formed in March 1941 originally for the purpose of performing commando raids during ...

(a British Army sabotage and resistance unit composed of Norwegians), attached limpet mines to ''Monte Rosa''s hull while she was in Oslo harbour. The British had learned the ship was to take 3,000 German troops back to Germany. The raid's purpose was to sink her during the voyage. The pair twice bluffed their way into the dock area by posing as electricians, then hid for three days as they waited for the ship to arrive. After she docked, they paddled out to her in an inflatable rubber boat and attached their mines. The mines detonated when the ship was near Øresund

Øresund or Öresund (, ; ; ), commonly known in English as the Sound, is a strait which forms the Denmark–Sweden border, Danish–Swedish border, separating Zealand (Denmark) from Scania (Sweden). The strait has a length of ; its width var ...

. They damaged her hull, but she stayed afloat, and returned to harbour under her own power.

Further war damage

In September 1944 another explosion, possibly by a mine, damaged ''Monte Rosa''. , a Norwegian boy with German parents who was being forcibly taken to Germany, was one of those aboard when it happened. In his memoirs, published on 2008, he wrote that the ship was carrying German troops, plus Norwegian women with young children, who were being taken to Germany as part of the programme. The explosion was at 0500 hrs, and about 200 people aboard were trapped and drowned as the ship's captain closed the watertight bulkhead doors to limit flooding and keep the ship afloat. On 16 February 1945 a mine explosion near theHel Peninsula

Hel Peninsula (; ; ; or ''Putziger Nehrung'') is a sand bar peninsula in northern Poland separating the Bay of Puck from the open Baltic Sea. It is located in Puck County of the Pomeranian Voivodeship.

Name

The name of the peninsula ...

in the Baltic damaged ''Monte Rosa'', flooding her engine room. She was towed to Gdynia

Gdynia is a city in northern Poland and a seaport on the Baltic Sea coast. With an estimated population of 257,000, it is the List of cities in Poland, 12th-largest city in Poland and the second-largest in the Pomeranian Voivodeship after Gdańsk ...

for temporary repairs. She was then towed to Copenhagen, carrying 5,000 German refugees fleeing from the advancing Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

. She was then taken to Kiel

Kiel ( ; ) is the capital and most populous city in the northern Germany, German state of Schleswig-Holstein. With a population of around 250,000, it is Germany's largest city on the Baltic Sea. It is located on the Kieler Förde inlet of the Ba ...

, where on 10 May 1945 British forces captured her.

UK service

In summer 1945 a Danish dockyard repaired ''Monte Rosa''s war damage. On 18 November 1945, ownership was transferred to the UK as aprize of war

A prize of war (also called spoils of war, bounty or booty) is a piece of enemy property or land seized by a belligerent party during or after a war or battle. This term was used nearly exclusively in terms of captured ships during the 18th and 1 ...

. In 1946 she was refitted at South Shields

South Shields () is a coastal town in South Tyneside, Tyne and Wear, England; it is on the south bank of the mouth of the River Tyne. The town was once known in Roman Britain, Roman times as ''Arbeia'' and as ''Caer Urfa'' by the Early Middle Ag ...

as a troopship. On 21 January 1947 she was renamed HMT ''Empire Windrush''. She was registered as a UK merchant ship

A merchant ship, merchant vessel, trading vessel, or merchantman is a watercraft that transports cargo or carries passengers for hire. This is in contrast to pleasure craft, which are used for personal recreation, and naval ships, which are ...

, and assigned to the UK Ministry of Transport, who contracted The New Zealand Shipping Company

The New Zealand Shipping Company (NZSC) was a shipping company whose ships ran passenger and cargo services between Great Britain and New Zealand between 1873 and 1973.

A group of Christchurch businessmen founded the company in 1873, similar ...

to manage her.

By then she was the only survivor of the five ''Monte''-class ships. ''Monte Cervantes'' sank near Tierra del Fuego

Tierra del Fuego (, ; Spanish for "Land of Fire", rarely also Fireland in English) is an archipelago off the southernmost tip of the South America, South American mainland, across the Strait of Magellan.

The archipelago consists of the main is ...

in 1930. Two members of the class were sunk in Kiel

Kiel ( ; ) is the capital and most populous city in the northern Germany, German state of Schleswig-Holstein. With a population of around 250,000, it is Germany's largest city on the Baltic Sea. It is located on the Kieler Förde inlet of the Ba ...

harbour by separate wartime air-raids, ''Monte Sarmiento'' in February 1942 and ''Monte Olivia'' in April 1945. ''Monte Pascoal'' was damaged by an air raid on Wilhelmshaven

Wilhelmshaven (, ''Wilhelm's Harbour''; Northern Low Saxon: ''Willemshaven'') is a coastal town in Lower Saxony, Germany. It is situated on the western side of the Jade Bight, a bay of the North Sea, and has a population of 76,089. Wilhelmsha ...

in February 1944. In 1946 she was filled with chemical bombs, and the British scuttled

Scuttling is the act of deliberately sinking a ship by allowing water to flow into the hull, typically by its crew opening holes in its hull.

Scuttling may be performed to dispose of an abandoned, old, or captured vessel; to prevent the vesse ...

her in the Skagerrak

The Skagerrak (; , , ) is a strait running between the North Jutlandic Island of Denmark, the east coast of Norway and the west coast of Sweden, connecting the North Sea and the Kattegat sea.

The Skagerrak contains some of the busiest shipping ...

.

As a troopship, ''Empire Windrush'' made 13 round trips between Britain and the Far East. Her route was between Southampton

Southampton is a port City status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Hampshire, England. It is located approximately southwest of London, west of Portsmouth, and southeast of Salisbury. Southampton had a population of 253, ...

and Hong Kong

Hong Kong)., Legally Hong Kong, China in international treaties and organizations. is a special administrative region of China. With 7.5 million residents in a territory, Hong Kong is the fourth most densely populated region in the wor ...

, via Gibraltar

Gibraltar ( , ) is a British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory and British overseas cities, city located at the southern tip of the Iberian Peninsula, on the Bay of Gibraltar, near the exit of the Mediterranean Sea into the A ...

; Suez

Suez (, , , ) is a Port#Seaport, seaport city with a population of about 800,000 in north-eastern Egypt, located on the north coast of the Gulf of Suez on the Red Sea, near the southern terminus of the Suez Canal. It is the capital and largest c ...

; Aden

Aden () is a port city located in Yemen in the southern part of the Arabian peninsula, on the north coast of the Gulf of Aden, positioned near the eastern approach to the Red Sea. It is situated approximately 170 km (110 mi) east of ...

; Colombo

Colombo, ( ; , ; , ), is the executive and judicial capital and largest city of Sri Lanka by population. The Colombo metropolitan area is estimated to have a population of 5.6 million, and 752,993 within the municipal limits. It is the ...

; and Singapore

Singapore, officially the Republic of Singapore, is an island country and city-state in Southeast Asia. The country's territory comprises one main island, 63 satellite islands and islets, and one outlying islet. It is about one degree ...

. Her route was extended to Kure

is a city in the Hiroshima Prefecture, Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 208,024 in 106,616 households and a population density of 590 persons per km2. The total area of the city is . With a strong industrial and naval heritage, ...

in Japan during the Korean War

The Korean War (25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953) was an armed conflict on the Korean Peninsula fought between North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea; DPRK) and South Korea (Republic of Korea; ROK) and their allies. North Korea was s ...

. She also made ten round trips to the Mediterranean; four to India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

; and one to the West Indies.

West Indian migrants

In 1948, ''Empire Windrush'' travelled from the United Kingdom to the Caribbean, to repatriate around 500 West Indians who had served in the Royal Air Force during World War II. She was also carrying 257 civilians, including women and children. The officer in charge of the servicemen wasSierra Leonean

The demographics of Sierra Leone are made up of an indigenous population from 18 ethnic groups. The Temne in the north and the Mende in the south are the largest. About 60,000 are Krio, the descendants of freed slaves who returned to Sierra L ...

Flight Lieutenant John Henry Clavell Smythe. He later became Attorney General of Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone, officially the Republic of Sierra Leone, is a country on the southwest coast of West Africa. It is bordered to the southeast by Liberia and by Guinea to the north. Sierra Leone's land area is . It has a tropical climate and envi ...

. With him on the voyage was Flight Lieutenant John Jellicoe Blair from Jamaica. The ship departed from Southampton

Southampton is a port City status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Hampshire, England. It is located approximately southwest of London, west of Portsmouth, and southeast of Salisbury. Southampton had a population of 253, ...

on 7 May and arrived in Trinidad

Trinidad is the larger, more populous island of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago, the country. The island lies off the northeastern coast of Venezuela and sits on the continental shelf of South America. It is the southernmost island in ...

on 20 May. She then stopped at Kingston

Kingston may refer to:

Places

* List of places called Kingston, including the six most populated:

** Kingston, Jamaica

** Kingston upon Hull, England

** City of Kingston, Victoria, Australia

** Kingston, Ontario, Canada

** Kingston upon Thames, ...

, Jamaica, Tampico

Tampico is a city and port in the southeastern part of the Mexican state of Tamaulipas. It is located on the north bank of the Pánuco River, about inland from the Gulf of Mexico, and directly north of the state of Veracruz. Tampico is the fif ...

, Mexico, Havana

Havana (; ) is the capital and largest city of Cuba. The heart of La Habana Province, Havana is the country's main port and commercial center.Bermuda

Bermuda is a British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean. The closest land outside the territory is in the American state of North Carolina, about to the west-northwest.

Bermuda is an ...

, before returning to the United Kingdom.

Several weeks before the ship left the United Kingdom, opportunistic advertisements had been placed in a Jamaican newspaper, ''The Daily Gleaner

''The Daily Gleaner'' is a morning daily newspaper serving the city of Fredericton, New Brunswick, and the upper Saint John River Valley. The paper was printed Monday through Saturday, until dropping to Tuesday through Saturday in 2022 and anno ...

'', offering cheap passage on the ship's return voyage; advertisements were also placed in newspapers in British Honduras

British Honduras was a Crown colony on the east coast of Central America — specifically located on the southern edge of the Yucatan Peninsula from 1783 to 1964, then a self-governing colony — renamed Belize from June 1973

, British Guiana, Trinidad and Tobago

Trinidad and Tobago, officially the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago, is the southernmost island country in the Caribbean, comprising the main islands of Trinidad and Tobago, along with several List of islands of Trinidad and Tobago, smaller i ...

and other places. However, the cheapest fares were only available to men, who were accommodated in the large, dormitory areas usually allocated to troops. Women were required to travel in the ship's two and four-berth cabins, that cost considerably more.

Many former servicemen took this opportunity to return to Britain in hope of finding better employment. Some wished to rejoin the RAF. Others decided to make the journey just to see what the "mother country" was like. One passenger later recalled that demand for tickets far exceeded supply, and there was a long queue to buy one.

The British Nationality Bill to give the status of citizenship of the United Kingdom and Colonies (CUKC status) to all British subjects connected with the United Kingdom or a British colony, was going through Parliament. Some Caribbean migrants decided to embark in anticipation that the bill would become an Act of Parliament. Until 1962, the UK had no immigration control for CUKCs. They could settle in the UK indefinitely, without restriction.

Passengers aboard

A figure often given for the number ofWest Indian

A West Indian is a native or inhabitant of the West Indies (the Antilles and the Lucayan Archipelago). According to the ''Oxford English Dictionary'' (''OED''), the term ''West Indian'' in 1597 described the indigenous inhabitants of the West In ...

migrants aboard ''Empire Windrush'' is 492, based on news reports in the media at the time, which variously announced that "more than 400", "430" or "500" Jamaican men had arrived in Britain. However, the ship's manifest

Manifest may refer to:

Computing

* Manifest file, a metadata file that enumerates files in a program or package

* Manifest (CLI), a metadata text file for CLI assemblies

Events

* Manifest (convention), a defunct anime festival in Melbourne, Au ...

, kept in the United Kingdom National Archives, shows that 802 passengers gave their last place of residence as a country in the Caribbean.

Among Caribbean passengers was Jamaican-born Sam Beaver King, who was travelling to the UK to rejoin the RAF. He later helped to found the Notting Hill Carnival

The Notting Hill Carnival is an annual Caribbean Carnival event that has taken place in London since 1966

, and became the first black Mayor of Southwark

The London Borough of Southwark ( ) in South London forms part of Inner London and is connected by bridges across the River Thames to the City of London and the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It was created in 1965 when three smaller council ...

. The Jamaican artist and master

Master, master's or masters may refer to:

Ranks or titles

In education:

*Master (college), head of a college

*Master's degree, a postgraduate or sometimes undergraduate degree in the specified discipline

*Schoolmaster or master, presiding office ...

potter

A potter is someone who makes pottery.

Potter may also refer to:

Places United States

*Potter, originally a section on the Alaska Railroad, currently a neighborhood of Anchorage, Alaska, US

*Potter, Arkansas

*Potter, Nebraska

*Potters, New Jerse ...

Cecil Baugh

Cecil Archibald Baugh (November 22, 1908 – June 28, 2005), was a Jamaican master potter and artist.

Early life

Baugh was born on November 22, 1908, in Bangor Ridge, Portland Parish, Jamaica to Isaac Baugh, a sawyer, and Emma Cobran-Baugh, ...

was also aboard. There were a number of musicians who were later to become well known. These included the Calypso music

Calypso is a style of Caribbean music that originated in Trinidad and Tobago from Afro-Trinidadians during the early- to mid-19th century and spread to the rest of the Caribbean Antilles by the mid-20th century. Its rhythms can be traced back ...

ians Lord Kitchener, Lord Beginner

Egbert Moore (1904–1981), known as Lord Beginner, was a popular calypsonian.

Biography

Moore was born in Port-of-Spain in Trinidad. According to AllMusic: "After attracting attention with his soulful singing in Trinidad and Tobago, Lord Begin ...

and Lord Woodbine

Harold Adolphus Phillips (15 January 1929 – 5 July 2000), known as Lord Woodbine, was a Trinidadian calypsonian and music promoter. He is regarded by some as the musical mentor of the Beatles, and has been called the "sixth Beatle".Alan Clays ...

, all from Trinidad; the Jamaican jazz trumpeter Dizzy Reece

Alphonso Son "Dizzy" Reece (born 5 January 1931) is a Jamaican-born jazz trumpeter. Reece emerged within London's burgeoning bebop jazz scene during the 1950s and went on to become a leading proponent of hard bop jazz in New York City.

He l ...

and the Trinidadian singer Mona Baptiste

Mona Baptiste (21 June 1926 – 25 June 1993) was a Trinidad and Tobago-born singer and actress in London and Germany. She was largely popular from songs such as "Calypso Blues" and "There's Something in the Air". She also acted in multiple musi ...

, one of the few women on the ship, who travelled first class. A small number of the Caribbean people aboard were Indo-Caribbeans

Indo-Caribbean or Indian-Caribbean people are people from the Caribbean who trace their ancestry to the Indian subcontinent. They are descendants of the Girmityas, Jahaji Indian indenture system, indentured laborers from British Raj, British India ...

. One of whom, Sikaram Gopthal, was the father of the record-label owner Lee Gopthal

Lehman Serikeesna Gopthal (1 March 1938 – 29 August 1997), known as Lee Gopthal, was a Jamaican-British record label owner and promoter, the co-founder of Trojan Records.

Life and career

He was born in Constant Spring, Jamaica, into a family ...

.

There were also 66 Polish passengers who embarked when the ship called at Tampico, Mexico. They were women and children whom the Soviets had deported to Siberia after the Soviet invasion of Poland

The Soviet invasion of Poland was a military conflict by the Soviet Union without a formal declaration of war. On 17 September 1939, the Soviet Union invaded Second Polish Republic, Poland from the east, 16 days after Nazi Germany invaded Polan ...

in 1939, but who had escaped and travelled via India and the Pacific to Mexico. About 1,400 had been living at a refugee camp at Santa Rosa near León, Guanajuato

León (), officially León de Los Aldama, is the most populous city and municipal seat of the municipality of León in the Mexican state of Guanajuato. In the 2020 census, INEGI reported 1,579,803 people living in the city of León and 1,721,21 ...

since 1943. They were granted permission to settle in the UK under the Polish Resettlement Act 1947

The Polish Resettlement Act 1947 ( 10 & 11 Geo. 6. c. 19) was the first ever mass immigration legislation of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It offered British citizenship to over 250,000 displaced Polish troops on British soil who had foug ...

. One of them later recalled that they were given cabins below the waterline, allowed on deck only in escorted groups, and kept segregated from the other passengers.

Of the other passengers, 119 were from the UK, and 40 from elsewhere in the world. Non-Caribbean people aboard included Nancy Cunard

Nancy Clara Cunard (10 March 1896 – 17 March 1965) was a British writer, heiress and political activist. She was born into the British upper class, and devoted much of her life to fighting racism and fascism. She became a muse to some of the ...

, English writer and heiress to the Cunard

The Cunard Line ( ) is a British shipping and an international cruise line based at Carnival House at Southampton, England, operated by Carnival UK and owned by Carnival Corporation & plc. Since 2011, Cunard and its four ships have been r ...

shipping fortune; the travel writer Freya Stark

Dame Freya Madeline Stark (31 January 18939 May 1993) was a British-Italian explorer and travel writer. She wrote more than two dozen books on her travels in the Middle East and Afghanistan as well as several autobiographical works and essays. ...

(who shared a cabin with Cunard); Lady Ivy Woolley, the wife of Sir Charles Woolley, the governor of British Guiana; Gertrude Whitelaw, the wealthy widow of the former Member of Parliament William Whitelaw

William Stephen Ian Whitelaw, 1st Viscount Whitelaw (28 June 1918 – 1 July 1999) was a British Conservative Party politician who served in a wide number of Cabinet positions, most notably as Home Secretary from 1979 to 1983 and as '' de fac ...

. and Peter Jonas, who was only two years old and travelling with his mother and older-sister. He would be later well known as an arts administrator

Arts administration (alternatively arts management) is a field in the arts sector that facilitates programming within cultural organizations. Arts administrators are responsible for facilitating the day-to-day operations of the organization as we ...

and opera company director.

One of the stowaways was a woman called Evelyn Wauchope, a 27-year-old dressmaker. She was discovered seven days out of Kingston. Some of the musicians on-board organized a benefit concert that raised enough money for her fare, and £4 spending money.

Arrival

''Empire Windrush''s arrival became a news event. When she was in the English Channel, the ''Evening Standard

The ''London Standard'', formerly the ''Evening Standard'' (1904–2024) and originally ''The Standard'' (1827–1904), is a long-established regional newspaper published weekly and distributed free newspaper, free of charge in London, Engl ...

'' sent an aircraft to photograph her from the air, and published the story on its front page. She docked at Tilbury

Tilbury is a port town in the borough of Thurrock, Essex, England. The present town was established as separate settlement in the late 19th century, on land that was mainly part of Chadwell St Mary. It contains a Tilbury Fort, 16th century fort ...

, downriver from London, on 21 June 1948, and the 1,027 passengers began disembarking the next day. This was covered by newspaper reporters and by Pathé News

Pathé News was a producer of newsreels and documentaries from 1910 to 1970 in the United Kingdom. Its founder, Charles Pathé, was a pioneer of moving pictures in the silent era. The Pathé News archive is known today as "British Pathé". I ...

newsreel

A newsreel is a form of short documentary film, containing news, news stories and items of topical interest, that was prevalent between the 1910s and the mid 1970s. Typically presented in a Movie theater, cinema, newsreels were a source of cu ...

cameras. The name Windrush, as a result, has come to be used as shorthand for West Indian migration, and, by extension, for the beginning of modern British multiracial society.

The purpose of ''Empire Windrush''s voyage to the Caribbean had been to repatriate service personnel. The UK government neither expected nor welcomed her return with civilian, West Indian migrants. Three days before the ship arrived, Arthur Creech Jones

Arthur Creech Jones (15 May 1891 – 23 October 1964) was a British trade union official and politician. Originally a civil servant, his imprisonment as a conscientious objector during the First World War forced him to change careers. He was e ...

, the Secretary of State for the Colonies

The secretary of state for the colonies or colonial secretary was the Cabinet of the United Kingdom's government minister, minister in charge of managing certain parts of the British Empire.

The colonial secretary never had responsibility for t ...

, wrote a Cabinet

Cabinet or The Cabinet may refer to:

Furniture

* Cabinetry, a box-shaped piece of furniture with doors and/or drawers

* Display cabinet, a piece of furniture with one or more transparent glass sheets or transparent polycarbonate sheets

* Filin ...

memorandum noting that the Jamaican Government could not legally stop people from leaving, and the UK government could not legally stop them from landing. However, he stated that the Government was opposed to this migration, and both the Colonial Office

The Colonial Office was a government department of the Kingdom of Great Britain and later of the United Kingdom, first created in 1768 from the Southern Department to deal with colonial affairs in North America (particularly the Thirteen Colo ...

and the Jamaican government would take all possible steps to discourage it.

The day after arrival, several MPs, including James Dixon Murray

James Dixon Murray (17 September 1887 – 24 January 1965) was a British coal miner and Labour Party politician in the United Kingdom.

Early life and education

Murray was born in East Howle, County Durham, on 17 September 1887 to William Murray ...

, warned the Prime Minister that such an " argosy of Jamaicans", might "cause discord and unhappiness among all concerned". George Isaacs

George Alfred Isaacs JP DL (28 May 1883 – 26 April 1979) was a British politician and trades unionist who served in the government of Clement Attlee.

Isaacs was born in Finsbury to a Methodist family. He married Flora Beasley (1884–19 ...

, the Minister of Labour Minister of labour (in British English) or labor (in American English) is typically a cabinet-level position with portfolio responsibility for setting national labour standards, labour dispute mechanisms, employment, workforce participation, traini ...

, stated in Parliament that there would be no encouragement for others to follow their example. Despite this, Parliament did not pass the first legislation controlling immigration from the Commonwealth until 1962.

Passengers who had not already arranged accommodation were temporarily housed in the Clapham South

Clapham South () is a London Underground station. It is on the Northern line between and Balham stations, and is in both Travelcard Zone 2 and Travelcard Zone 3. The station is located at the corner of Balham Hill (A24) and Nightingale Lane, ...

deep shelter in southwest London, less than a mile away from the Coldharbour Lane

Coldharbour Lane is a road in south London, England, that leads south-westwards from Camberwell to Brixton. The road is over long with a mixture of residential, business and retail buildings – the stretch of Coldharbour Lane near Brixton Ma ...

Employment Exchange in Brixton

Brixton is an area of South London, part of the London Borough of Lambeth, England. The area is identified in the London Plan as one of 35 major centres in Greater London. Brixton experienced a rapid rise in population during the 19th century ...

, where some of the arrivals sought work. The stowaways were given brief prison sentences, but were allowed to remain in the UK after their release.

Many of ''Empire Windrush''s passengers intended to stay for only a few years. A number did return to the Caribbean, but a majority settled permanently in the UK. Those born in the West Indies who settled in the UK in this migration movement over the following years are now typically referred to as the "Windrush Generation".

Previous Caribbean migrant arrivals

While the 1948 voyage of the ''Empire Windrush'' is well-known, she was not the first ship to bring West Indians to the UK after World War II. On 31 March 1947,Orient Line

The Orient Steam Navigation Company, also known as the Orient Line, was a UK, British shipping company with roots going back to the late 18th century. From the early 20th century onwards, an association began with P&O (company), P&O which bec ...

's ''Ormonde'' reached Liverpool

Liverpool is a port City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. It is situated on the eastern side of the River Mersey, Mersey Estuary, near the Irish Sea, north-west of London. With a population ...

from Jamaica with 241 passengers, including 11 stowaways. They included Ralph Lowe, who became the father of the author and poet Hannah Lowe

Hannah Lowe (born 1976) is a British writer, known for her collection of poetry ''Chick'' (2013), her family memoir ''Long Time, No See'' (2015) and her research into the historicising of the HMT ''Empire Windrush'' and postwar Caribbean migrat ...

. Liverpool Magistrates Court tried the stowaways and sentenced them to one day in prison, which effectively meant their immediate release.

On 21 December 1947, Royal Mail Line's ''Almanzora'' reached Southampton with 200 passengers aboard. As with ''Empire Windrush'', many were former service personnel who had served in the RAF in World War II. 30 adult stowaways and one boy were arrested when the ship docked; they were jailed for 28 days.

Final years

In May 1949, ''Empire Windrush'' was en route from Gibraltar toPort Said

Port Said ( , , ) is a port city that lies in the northeast Egypt extending about along the coast of the Mediterranean Sea, straddling the west bank of the northern mouth of the Suez Canal. The city is the capital city, capital of the Port S ...

when fire broke out aboard. Four ships were put on standby to assist if she had to be abandoned. The passengers were placed in the lifeboats

Lifeboat may refer to:

Rescue vessels

* Lifeboat (shipboard), a small craft aboard a ship to allow for emergency escape

* Lifeboat (rescue), a boat designed for sea rescues

* Airborne lifeboat, an air-dropped boat used to save downed airmen

...

, but the boats were not launched, and the ship was subsequently towed back to Gibraltar.

In February 1950, ''Empire Windrush'' repatriated the last British troops stationed in Greece, embarking the First Battalion of the Bedfordshire and Hertfordshire Regiment

The Bedfordshire and Hertfordshire Regiment was the final title of a line infantry regiment of the British Army that was originally formed in 1688. After centuries of service in many conflicts and wars, including both the First and Second World W ...

at Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki (; ), also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, Salonika, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece (with slightly over one million inhabitants in its Thessaloniki metropolitan area, metropolitan area) and the capital cit ...

on 5 February, and other troops and their families at Piraeus

Piraeus ( ; ; , Ancient: , Katharevousa: ) is a port city within the Athens urban area ("Greater Athens"), in the Attica region of Greece. It is located southwest of Athens city centre along the east coast of the Saronic Gulf in the Ath ...

. British troops had been in Greece since 1944, fighting for the Kingdom of Greece

The Kingdom of Greece (, Romanization, romanized: ''Vasíleion tis Elládos'', pronounced ) was the Greece, Greek Nation state, nation-state established in 1832 and was the successor state to the First Hellenic Republic. It was internationally ...

in the Greek Civil War

The Greek Civil War () took place from 1946 to 1949. The conflict, which erupted shortly after the end of World War II, consisted of a Communism, Communist-led uprising against the established government of the Kingdom of Greece. The rebels decl ...

.

On 7 February 1953, around south of the Nicobar Islands

The Nicobar Islands are an archipelago, archipelagic island chain in the eastern Indian Ocean. They are located in Southeast Asia, northwest of Aceh on Sumatra, and separated from Thailand to the east by the Andaman Sea. Located southeast of t ...

, ''Empire Windrush'' sighted a small cargo

In transportation, cargo refers to goods transported by land, water or air, while freight refers to its conveyance. In economics, freight refers to goods transported at a freight rate for commercial gain. The term cargo is also used in cas ...

motor ship, ''Holchu'', adrift with a broken mast. ''Empire Windrush'' broadcast a general warning by wireless. A British cargo steamship

A steamship, often referred to as a steamer, is a type of steam-powered vessel, typically ocean-faring and seaworthy, that is propelled by one or more steam engines that typically move (turn) propellers or paddlewheels. The first steamships ...

, ''Ranee'', responded by changing course to investigate. ''Ranee'' found no trace of ''Holchu''s five crew, and towed the vessel to Colombo. ''Holchu'' was carrying a cargo of bagged rice and was in good condition apart from her broken mast; the vessel was not short of food, water or fuel. A meal was found prepared in the ship's galley. The fate of her crew remains unknown, and the incident is cited in several works on Ufology

Ufology, sometimes written UFOlogy ( or ), is the investigation of unidentified flying objects (UFOs) by people who believe that they may be of extraordinary claims, extraordinary origins (most frequently of extraterrestrial hypothesis, extrate ...

and the Bermuda Triangle

The Bermuda Triangle, also known as the Devil's Triangle, is a loosely defined region in the North Atlantic Ocean, roughly bounded by Florida, Bermuda, and Puerto Rico. Since the mid-20th century, it has been the focus of an urban legend sug ...

.

In June 1953 ''Empire Windrush'' took part in the Fleet review to commemorate the Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II

The Coronation of the British monarch, coronation of Elizabeth II as queen of the United Kingdom and the other Commonwealth realms took place on 2 June 1953 at Westminster Abbey in London. Elizabeth acceded to the throne at the age of 25 upon th ...

.

Final voyage and loss

In February 1954 ''Empire Windrush'' leftYokohama

is the List of cities in Japan, second-largest city in Japan by population as well as by area, and the country's most populous Municipalities of Japan, municipality. It is the capital and most populous city in Kanagawa Prefecture, with a popu ...

for the UK. She called at Kure; Hong Kong; Singapore; Colombo; Aden; and Port Said. Her passengers included recovering wounded United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

servicemen from the Korean War

The Korean War (25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953) was an armed conflict on the Korean Peninsula fought between North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea; DPRK) and South Korea (Republic of Korea; ROK) and their allies. North Korea was s ...

, including members of the Duke of Wellington's Regiment

The Duke of Wellington's Regiment (West Riding) was a line infantry regiment of the British Army, forming part of the King's Division.

In 1702, Colonel George Hastings, 8th Earl of Huntingdon, was authorised to raise a new regiment, which he di ...

who had been wounded at the Third Battle of the Hook

The Third Battle of the Hook () was a battle of the Korean War that took place between a United Nations Command (UN) force, consisting mostly of British troops, supported on their flanks by American, Canadian and Turkish units against a predom ...

in May 1953.

The voyage was beset by engine breakdowns and other defects, including a fire after the leaving Hong Kong. She took ten weeks to reach Port Said, where a party of 50 Royal Marines

The Royal Marines provide the United Kingdom's amphibious warfare, amphibious special operations capable commando force, one of the :Fighting Arms of the Royal Navy, five fighting arms of the Royal Navy, a Company (military unit), company str ...

from 3 Commando Brigade

United Kingdom Commando Force (UKCF), previously called 3 Commando Brigade (3 Cdo Bde), is the UK's special operations-capable commando formation of the Royal Marines. It is composed of Royal Marine Commandos and commando qualified personnel f ...

embarked aboard her.

Aboard were 222 crew and 1,276 passengers, including military personnel, and some women and children who were dependents of some of the military personnel. Certified to carry 1,541 people, the ship was almost completely full, with 1,498 people aboard.

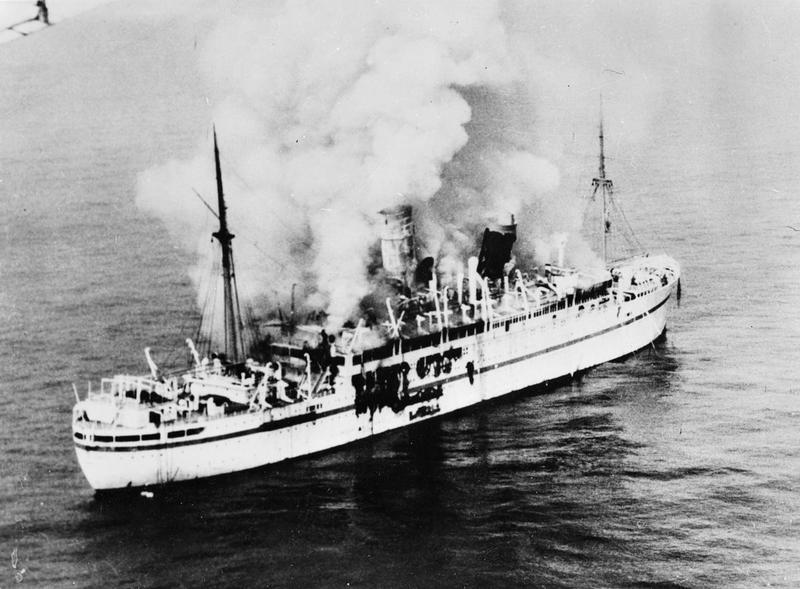

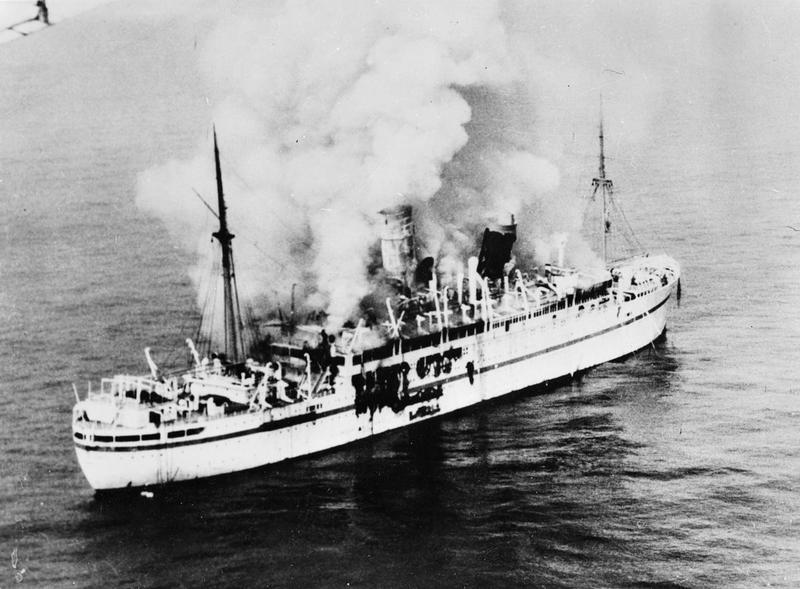

Fire

At around 0617 hrs on 28 March, ''Windrush'' was in the western Mediterranean, off the coast of Algeria, about northwest ofCape Caxine

Cap Caxine is a cape located in Algeria

Algeria, officially the People's Democratic Republic of Algeria, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It is bordered to Algeria–Tunisia border, the northeast by Tunisia; to Algeria� ...

. A sudden explosion in the engine room killed the Third

Third or 3rd may refer to:

Numbers

* 3rd, the ordinal form of the cardinal number 3

* , a fraction of one third

* 1⁄60 of a ''second'', i.e., the third in a series of fractional parts in a sexagesimal number system

Places

* 3rd Street (di ...

; Seventh; and Eighth engineers

Engineers, as practitioners of engineering, are professionals who invent, design, build, maintain and test machines, complex systems, structures, gadgets and materials. They aim to fulfill functional objectives and requirements while consider ...

and the First Electrician, and started a fierce fire. Two greasers; one who was the fifth man in the engine room; and another who was in the boiler room, managed to escape.

Both the Chief Officer

A chief mate (C/M) or chief officer, usually also synonymous with the first mate or first officer, is a licensed mariner and head of the deck department of a merchant ship. The chief mate is customarily a watchstander and is in charge of the ship ...

and the Master

Master, master's or masters may refer to:

Ranks or titles

In education:

*Master (college), head of a college

*Master's degree, a postgraduate or sometimes undergraduate degree in the specified discipline

*Schoolmaster or master, presiding office ...

were on the bridge

A bridge is a structure built to Span (engineering), span a physical obstacle (such as a body of water, valley, road, or railway) without blocking the path underneath. It is constructed for the purpose of providing passage over the obstacle, whi ...

. They heard the explosion, and saw black smoke and flames coming from the funnel. Attempts were made to contact the engine room by telephone—it was heard ringing but was not answered. The Chief Officer immediately mustered the ship's firefighting squad, who happened to be on deck at the time doing routine work, and went with them to the engine room. They were able to fight the fire for only a few minutes before the ship's electricity supply failed, stopping the water pumps that fed the fire hoses (all four main generators were inside the burning engine room). The emergency generator was started; this was supposed to power the ship's emergency lighting, bilge pump, fire pump, and radio. But problems with the main circuit breakers made its electricity supply unusable.

The Chief engineer

A chief engineer, commonly referred to as "Chief" or "ChEng", is the most senior licensed mariner (engine officer) of an engine department on a ship, typically a merchant ship, and holds overall leadership and the responsibility of that departmen ...

and the Second Engineer

A second engineer or first assistant engineer is a licensed member of the engineering department on a merchant vessel. This title is used for the person on a ship responsible for supervising the daily maintenance and operation of the engine depa ...

were unable to enter the engine room due to dense black smoke. The Second Engineer tried again after obtaining a smoke hood

A smoke hood, also called an Air-Purifying Respiratory Protective Smoke Escape Device (RPED), is a hood wherein a transparent airtight bag seals around the head of the wearer while an air filter held in the mouth connects to the outside atmosphe ...

, but could not see because of the smoke. He was unable to close a watertight door that might have contained the fire. Attempts to close all watertight doors using the controls on the bridge also failed.

Rescue

At 0623 hrs the Radio Officer broadcast the first

At 0623 hrs the Radio Officer broadcast the first distress signal

A distress signal, also known as a distress call, is an internationally recognized means for obtaining help. Distress signals are communicated by transmitting radio signals, displaying a visually observable item or illumination, or making a sou ...

. This was acknowledged by two French ships, and by radio stations at Gibraltar

Gibraltar ( , ) is a British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory and British overseas cities, city located at the southern tip of the Iberian Peninsula, on the Bay of Gibraltar, near the exit of the Mediterranean Sea into the A ...

, Oran

Oran () is a major coastal city located in the northwest of Algeria. It is considered the second most important city of Algeria, after the capital, Algiers, because of its population and commercial, industrial and cultural importance. It is w ...

and Algiers

Algiers is the capital city of Algeria as well as the capital of the Algiers Province; it extends over many Communes of Algeria, communes without having its own separate governing body. With 2,988,145 residents in 2008Census 14 April 2008: Offi ...

. After the electric power supply failed, radio signals continued to be sent via the emergency transmitter until 0645 hrs, when the fire stopped the Radio Officer from making further transmissions.

The order was given to wake the passengers and crew and muster them at their boat stations. The order was passed by word of mouth, as the loss of electric power had disabled the ship's public address system

A public address system (or PA system) is an electronic system comprising microphones, amplifiers, loudspeakers, and related equipment. It increases the apparent volume (loudness) of a human voice, musical instrument, or other acoustic sound sou ...

, electric alarm bells, and air

An atmosphere () is a layer of gases that envelop an astronomical object, held in place by the gravity of the object. A planet retains an atmosphere when the gravity is great and the temperature of the atmosphere is low. A stellar atmosph ...

and steam whistle

A steam whistle is a device used to produce sound in the form of a whistle using live steam, which creates, projects, and amplifies its sound by acting as a vibrating system.

Operation