Loyalism (American Revolution) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Loyalists were refugee colonists from

Loyalists were refugee colonists from

Before Calhoon's work, estimates of the Loyalist share of the population were somewhat higher, at about one-third, but these estimates are now rejected as too high by most scholars. In 1968 historian Paul H. Smith estimated there were about 400,000 Loyalists, or 16% of the white population of 2.25 million in 1780.

Historian

Before Calhoon's work, estimates of the Loyalist share of the population were somewhat higher, at about one-third, but these estimates are now rejected as too high by most scholars. In 1968 historian Paul H. Smith estimated there were about 400,000 Loyalists, or 16% of the white population of 2.25 million in 1780.

Historian

As a result of the looming crisis in 1775, Royal

As a result of the looming crisis in 1775, Royal

Patriot agents were active in

Patriot agents were active in

. from 1779 to 1782, despite the presence of Patriot forces in the northern part of Georgia. Essentially, the British were only able to maintain power in areas where they had a strong military presence. Black Loyalists helped rout the Virginia militia at the

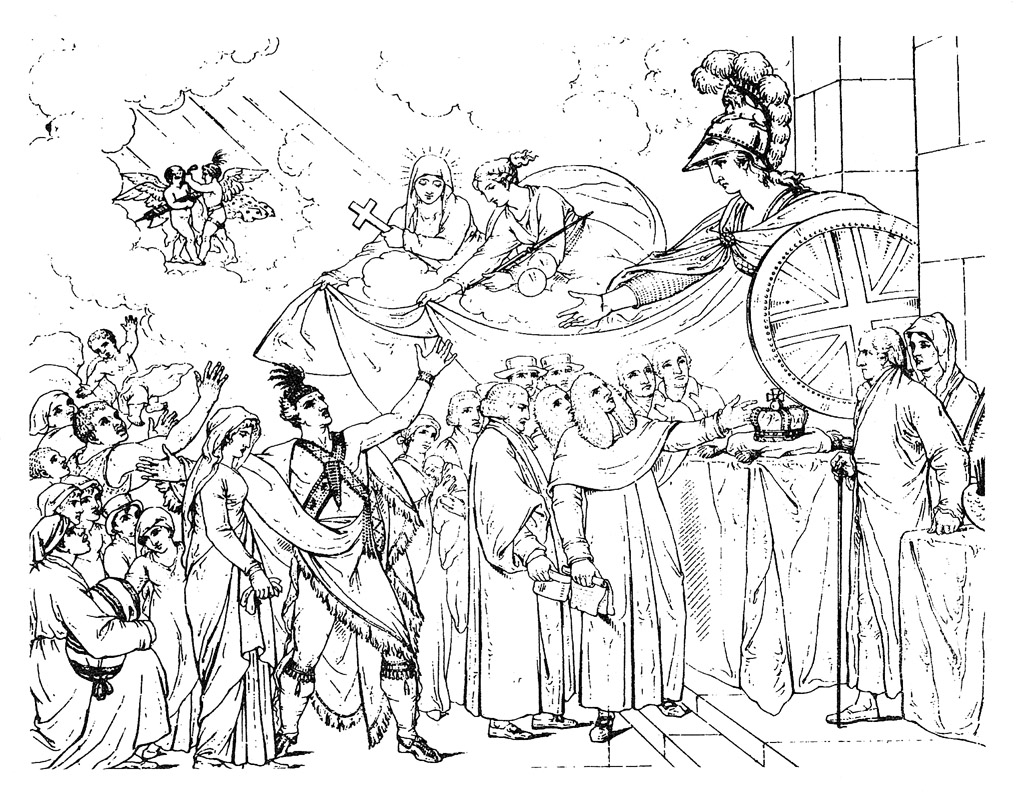

File:John Singleton Copley 001.jpg, John Copley's ''The Death of Major Pierson''

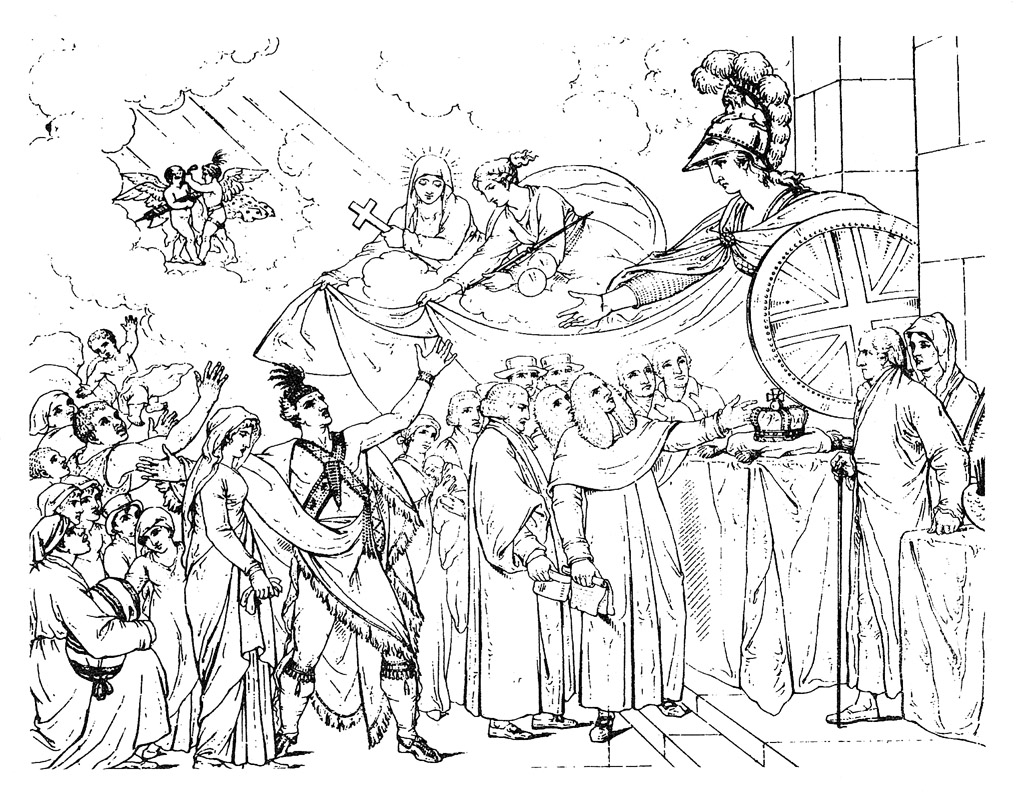

File:Benjamin West - John Eardley Wilmot - Google Art Project.jpg, Benjamin West's ''Reception'' as a detail of ''John Eardley Wilmot''

* ''The Adventures of Jonathan Corncob, Loyal American Refugee'' (1787) by Jonathan Corncob. According to Maya Jasanoff, "traveling to London to file a claim served as the opening gambit" for this "

collection

filling 115 microfilm reels of documents, letters, etc. reflecting the Loyalist experience in Canada.

to this collection may be found on the Queens University Archives website. * Godfrey–Milliken Bill, proposed Canadian law demanding compensation from the US for Loyalist claims after its independence. * Lorenzo Sabine (1803–1877), early historian and chronicler of the Loyalist experience * ''

online

* Frazer, Gregg L. ''God Against the Revolution: The Loyalist Clergy's Case against the American Revolution'' Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2018. * Gould, Philip. ''Writing the Rebellion: Loyalists and the Literature of Politics in British America'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016). * Jasanoff, Maya. ''Liberty's Exiles: American Loyalists in the Revolutionary World'' (2011), a comprehensive treatment, winner of the 2011

full text online

273 pp * Lennox, Jeffers. ''North of America: Loyalists, Indigenous Nations, and the Borders of the Long American Revolution'' (Yale University Press, 2022

online review

* Middlekauff, Robert. "The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763–1789." (2005 edition) * Moore, Christopher. ''The Loyalist: Revolution Exile Settlement''. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart (1994). * Mason, Keith. "The American Loyalist Diaspora and the Reconfiguration of the British Atlantic World." In ''Empire and Nation: The American Revolution and the Atlantic World'', ed. Eliga H. Gould and Peter S. Onuf (2005). * Minty, Christopher F

''Unfriendly to Liberty: Loyalist Networks and the Coming of the American Revolution in New York City''. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2023

* Nelson, William H. ''The American Tory'' (1961) * Norton, Mary Beth. ''The British-Americans: The Loyalist Exiles in England, 1774–1789''. Boston: Little, Brown, 1972. * ———. ''Liberty's Daughters: The Revolutionary Experience of American Women, 1750–1800'' (1996) * ———. "The Problem of the Loyalist – and the Problems of Loyalist Historians," ''Reviews in American History'' June 1974 v. 2 #2 pp 226–231 * Peck, Epaphroditus; ''The Loyalists of Connecticut'' (Yale University Press, 1934) * Potter, Janice. ''The Liberty We Seek: Loyalist Ideology in Colonial New York and Massachusetts'' (1983). * Quarles, Benjamin; ''Black Mosaic: Essays in Afro-American History and Historiography''

in JSTOR

* Van Tyne, Claude Halstead. ''The Loyalists in the American Revolution'' (1902) * Wade, Mason. ''The French Canadians: 1760–1945'' (1955) 2 vol. ::Compiled volumes of biographical sketches * Palmer, Gregory. ''Biographical Sketches of Loyalists of the American Revolution''. Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc., 1983. 998 pp. * Sabine, Lorenzo. ''The American Loyalists, or Biographical Sketches of Adherents to the British Crown in The War of the Revolution; Alphabetically Arranged; with a Preliminary Historical Essay.'' Boston: Charles C. Little and James Brown, 1847

Google Books vi, 733 pp.

* ———. ''Biographical Sketches of Loyalists of the American Revolution, with an Historical Essay''. 2 volumes. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1864

Google Books Volume 1, vi, 608 pp. Google Books Volume 2, 600 pp.

::Studies of individual Loyalists * *Bailyn, Bernard. ''The Ordeal of Thomas Hutchinson: Loyalism and the Destruction of the First British Empire'' (1974), full scale biography of the most prominent Loyalist * Gainey, Joseph R. "Rev. Charles Woodmason (''c''. 1720–1789): Author, Loyalist, Missionary, and Psalmodist." ''West Gallery: The Newsletter of the West Gallery Music Association'' (), Issue No. 59 (Autumn 2011), pp. 18–25. This undocumented article is the first publication to identify Woodmason's parents, background, baptism, marriage, and burial dates and places and contains much previously unavailable information. * Hill, James Riley, III. ''An exercise in futility: the pre-Revolutionary career and influence of loyalist James Simpson''. M. A. Thesis. University of South Carolina, Columbia, 1992. viii, 109 leaves ; 28 cm. * Hooker, Richard J., ed. ''The Carolina Backcountry on the Eve of the Revolution: The Journal and Other Writings of Charles Woodmason, Anglican Itinerant''. 1953. * Lohrenz, Otto; "The Advantage of Rank and Status: Thomas Price, a Loyalist Parson of Revolutionary Virginia." ''The Historian.'' 60#3 (1998) pp 561+. * Randall, Willard Sterne. ''A Little Revenge: Benjamin Franklin & His Son'' Little, Brown & Co, 1984. * Skemp, Sheila. ''William Franklin: Son of a Patriot, Servant of a King'' Oxford University Press, 1990. * Wright, J. Leitch. ''William Augusutus Bowles: Director General of the Creek Nation''. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1967. * Zimmer, Anne Y. ''Jonathan Boucher, loyalist in exile''. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 1978. ::Primary sources and guides to manuscripts and the literature * Allen, Robert S. ''Loyalist Literature: An Annotated Bibliographic Guide to the Writings on the Loyalists of the American Revolution''. Issue 2 of Dundurn Canadian historical document series, 1982. * Brown, Wallace. "Loyalist Historiography." ''Acadiensis'', Vol. 4, No. 1 (Autumn 1974), pp. 133–138. Link t

downloadable pdf

of this article. * ———

"The View at Two Hundred Years: The Loyalists of the American Revolution"

''Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society'', Vol. 80, Part 1 (April 1970), pp. 25–47. * Crary, Catherine S., ed. ''Price of Loyalty: Tory Writings from the Revolutionary Era'' (1973) * Egerton, Hugh Edward, ed. ''The Royal commission on the losses and services of American loyalists, 1783 to 1785, being the notes of Mr. Daniel Parker Coke, M. P., one of the commissioners during that period''. Oxford: The Roxburghe Club, 1915

Link to downloadable pdf

* Galloway, Joseph. ''The claim of the American loyalists: reviewed and maintained upon incontrovertible principles of law and justice''. G. and T. Wilkie, 1788. Downloadabl

Google Books pdf 138 pages

website, Harriet Irving Library, Fredericton campus,

Guide to the New York Public Library Loyalist Collection

(19 pdfs) * Palmer, Gregory S. ''A Bibliography of Loyalist Source Material in the United States, Canada, and Great Britain''. Westport, CT, 1982. * ''The Particular Case of the Georgia Loyalists: in Addition to the General Case and Claim of the American Loyalists, which was Lately Published by Order of Their Agents. February 1783''. n.p., 1783. 16 pp

Google Books pdf

The American Loyalists: Or, Biographical Sketches of Adherents to the ... (1847) by Lorenzo Sabine

Complete text of the first of two editions (the second appeared in 1864 in two volumes) of Sabine's ''magnum opus'' in pdf format.

Benjamin Franklin to Baron Francis Maseres, June 26, 1785

(Opinion of

Bibliography of the Loyalist Participation in the American Revolution

compiled by the

"Black Loyalists: Our History, Our People"

Haldimand Collection

The main source for historians in the study of the settlement of the American Loyalists in Canada. More than 20,000 letters and documents, now fully indexed, and free on the Web.

Story of Loyalist Privateer "Vengeance"

* ttp://www.royalprovincial.com/military/facts/ofrdecl.htm The Loyalist Declaration of Independencepublished in ''The Royal Gazette'' (New York) on November 17, 1781 (Transcription provided by Bruce Wallace and posted on The On-Line Institute for Advanced Loyalist Studies.)

The Loyalist Link: The Forest and The Sea – Port Roseway Loyalists

The Loyalist Research Network (LRN)

This website focuses on Canadian Loyalists, but, the links and bibliographies are extremely helpful to all serious Loyalist researchers.

The On-Line Institute for Advanced Loyalist Studies

* [https://books.google.com/books?id=LxKCmTq3cZwC&dq=Joseph+Blaney+married+Abigail+Browne&pg=PA244 "Salem Loyalists-unpublished letters" ''The New-England Historical and Geuealogical Register and Antiquarian Journal 1872'' pp. 243–248]

"A Short History of the United Empire Loyalists" Ann Mackenzie

* Originally published in 1987. 272 pages, available online in PDF format.

United Empire Loyalists' Association of Canada (UELAC)

"What is a Loyalist? The American Revolution as civil war"

by Edward Larkin, published in common-place, Vol. 8, No. 1 (October 2007). *

, The SCGenWeb Project Videos * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Loyalist, American Revolution Loyalists in the American Revolution Conservatism in the United States Toryism Monarchism in the United States

Loyalists were refugee colonists from

Loyalists were refugee colonists from thirteen

Thirteen or 13 may refer to:

* 13 (number)

* Any of the years 13 BC, AD 13, 1913, or 2013

Music Albums

* ''13'' (Black Sabbath album), 2013

* ''13'' (Blur album), 1999

* ''13'' (Borgeous album), 2016

* ''13'' (Brian Setzer album), 2006

* ...

of the 20 British American colonies who remained loyal to the British crown

The Crown is a political concept used in Commonwealth realms. Depending on the context used, it generally refers to the entirety of the State (polity), state (or in federal realms, the relevant level of government in that state), the executive ...

during the American Revolution

The American Revolution (1765–1783) was a colonial rebellion and war of independence in which the Thirteen Colonies broke from British America, British rule to form the United States of America. The revolution culminated in the American ...

, often referred to as Tories, Royalists, or King's Men at the time. They were opposed by the Patriots

A patriot is a person with the quality of patriotism.

Patriot(s) or The Patriot(s) may also refer to:

Political and military groups United States

* Patriot (American Revolution), those who supported the cause of independence in the American R ...

or Whigs, who supported the revolution and considered them "persons inimical to the liberties of America."

Prominent Loyalists repeatedly assured the British government

His Majesty's Government, abbreviated to HM Government or otherwise UK Government, is the central government, central executive authority of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

that many thousands of them would spring to arms and fight for the Crown. The British government acted in expectation of that, especially during the Southern campaigns of 1780 and 1781. Britain was able to effectively protect the people only in areas where they had military control, thus the number of military Loyalists was significantly lower than what had been expected. Loyalists were often under suspicion of those in the British military, who did not know whom they could fully trust in such a conflicted situation; they were often looked down upon.

Patriots watched suspected Loyalists very closely and would not tolerate any organized Loyalist opposition. Many outspoken or militarily active Loyalists were forced to flee, especially to their stronghold of New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

. William Franklin

William Franklin (22 February 1730 – 17 November 1813) was an American-born attorney, soldier, politician, and colonial administrator. He was the acknowledged extra-marital son of Benjamin Franklin. William Franklin was the last colonial G ...

, the royal governor of New Jersey

New Jersey is a U.S. state, state located in both the Mid-Atlantic States, Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern United States, Northeastern regions of the United States. Located at the geographic hub of the urban area, heavily urbanized Northeas ...

and son of Patriot leader Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin (April 17, 1790) was an American polymath: a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher and Political philosophy, political philosopher.#britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the m ...

, became the leader of the Loyalists after his release from a Patriot prison in 1778. He worked to build Loyalist military units to fight in the war. Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

writes: "there had been no less than twenty-five thousand loyalists enlisted in the British service during the five years of the fighting. At one time (1779) they had actually outnumbered the whole of the continental muster under the personal command of Washington."When their cause was defeated, about 15 percent of the Loyalists (65,000–70,000 people) fled to other parts of the

British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

; especially to the Kingdom of Great Britain

Great Britain, also known as the Kingdom of Great Britain, was a sovereign state in Western Europe from 1707 to the end of 1800. The state was created by the 1706 Treaty of Union and ratified by the Acts of Union 1707, which united the Kingd ...

or to British North America

British North America comprised the colonial territories of the British Empire in North America from 1783 onwards. English colonisation of North America began in the 16th century in Newfoundland, then further south at Roanoke and Jamestown, ...

and became known as United Empire Loyalist

United Empire Loyalist (UEL; or simply Loyalist) is an honorific title which was first given by the 1st Lord Dorchester, the governor of Quebec and governor general of the Canadas, to American Loyalists who resettled in British North Ameri ...

s. Most were compensated with Canadian land or British cash distributed through formal claims procedures. The southern Loyalists moved mostly to East

East is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from west and is the direction from which the Sun rises on the Earth.

Etymology

As in other languages, the word is formed from the fact that ea ...

or West Florida

West Florida () was a region on the northern coast of the Gulf of Mexico that underwent several boundary and sovereignty changes during its history. Great Britain established West and East Florida in 1763 out of land acquired from France and S ...

or to British Caribbean

The British West Indies (BWI) were the territories in the West Indies under British rule, including Anguilla, the Cayman Islands, the Turks and Caicos Islands, Montserrat, the British Virgin Islands, Bermuda, Antigua and Barbuda, the Bahamas ...

possessions. Loyalists who left the US received over £3 million or about 37% of their losses from the British government. Loyalists who stayed in the US were generally able to retain their property and become American citizens. Many Loyalists eventually returned to the US after the war and after discriminatory laws had been repealed. Historians have estimated that between 15% and 20% (300,000 to 400,000) of the 2,000,000 whites in the colonies in 1775 were Loyalists.

Background

Families were often divided during theAmerican Revolution

The American Revolution (1765–1783) was a colonial rebellion and war of independence in which the Thirteen Colonies broke from British America, British rule to form the United States of America. The revolution culminated in the American ...

, and many felt themselves to be both American and British, still owing loyalty to the mother country. Maryland lawyer Daniel Dulaney the Younger

Daniel Dulany the Younger (June 28, 1722 – March 17, 1797) was a Maryland Loyalist politician, Mayor of Annapolis, and an influential American lawyer in the period immediately before the American Revolution. His pamphlet ''Considerations on the ...

opposed taxation without representation but would not break his oath to the king or take up arms against him. He wrote: "There may be a time when redress may not be obtained. Till then, I shall recommend a legal, orderly, and prudent resentment". Most Americans hoped for a peaceful reconciliation but were forced to choose sides by the Patriots

A patriot is a person with the quality of patriotism.

Patriot(s) or The Patriot(s) may also refer to:

Political and military groups United States

* Patriot (American Revolution), those who supported the cause of independence in the American R ...

who took control nearly everywhere in the Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies were the British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America which broke away from the British Crown in the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783), and joined to form the United States of America.

The Thirteen C ...

in 1775–76.

Motives for loyalism

In 1948, Yale historianLeonard Woods Larabee

Leonard or ''Leo'' is a common English masculine given name and a surname.

The given name and surname originate from the Old High German '' Leonhard'' containing the prefix ''levon'' ("lion") from the Greek Λέων ("lion") through the Latin '' ...

identified eight characteristics of the Loyalists that made them essentially conservative and loyal to the king and to Britain:

* They were older, better established, and resisted radical change.

* They felt that rebellion against the Crown—the legitimate government—was morally wrong. They saw themselves as "British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and culture ...

born in the colonies" loyal to the British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

and saw a rebellion against the metropole

A metropole () is the homeland, central territory or the state exercising power over a colonial empire.

From the 19th century, the English term ''metropole'' was mainly used in the scope of the British, Spanish, French, Dutch, Portugu ...

(Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-west coast of continental Europe, consisting of the countries England, Scotland, and Wales. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the List of European ...

) as a betrayal to the empire. At the time the national identity

National identity is a person's identity or sense of belonging to one or more states or one or more nations. It is the sense of "a nation as a cohesive whole, as represented by distinctive traditions, culture, and language".

National identity ...

of the Americans was still in formation, and the very idea of two separate peoples (nationalities) with their own sovereign states (the Kingdom of Great Britain

Great Britain, also known as the Kingdom of Great Britain, was a sovereign state in Western Europe from 1707 to the end of 1800. The state was created by the 1706 Treaty of Union and ratified by the Acts of Union 1707, which united the Kingd ...

and the United States of America

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 contiguo ...

) was itself revolutionary. Eventually and gradually, as the war progressed and it became clear that the United States and Great Britain would become two separate countries, the Loyalists who remained in the United States adopted the national identity as Americans.

* They felt alienated when the Patriots (seen by them as separatist

Separatism is the advocacy of cultural, ethnic, tribal, religious, racial, regional, governmental, or gender separation from the larger group. As with secession, separatism conventionally refers to full political separation. Groups simply seekin ...

s who rebelled against the Crown) resorted to violence, such as burning down houses and tarring and feathering

Tarring and feathering is a form of public torture where a victim is stripped naked, or stripped to the waist, while wood tar (sometimes hot) is either poured or painted onto the person. The victim then either has feathers thrown on them or is r ...

.

* They wanted to take a middle-of-the-road position and were not pleased when forced by Patriots to declare their opposition.

* They had business and family links with Britain, and being a part of the British Empire was crucial in terms of commerce and their business operations.

* They felt that independence from Britain would come eventually but wanted it to come about organically.

* They were wary that chaos, corruption, and mob rule would come about as a result of revolution.

* Some were "pessimists" who did not display the same belief in the future that the Patriots did. Others recalled the dreadful experiences of many Jacobites after the failure of their 1715

Events

For dates within Great Britain and the British Empire, as well as in the Russian Empire, the "old style" Julian calendar was used in 1715, and can be converted to the "new style" Gregorian calendar (adopted in the British Empire in ...

and 1745

Events

January–March

* January 7 – War of the Austrian Succession: The Austrian Army, under the command of Field Marshal Károly József Batthyány, makes a surprise attack at Amberg and the winter quarters of the Bav ...

rebellions, who often had their lands confiscated by the Hanoverian

The adjective Hanoverian is used to describe:

* British monarchs or supporters of the House of Hanover, the dynasty which ruled the United Kingdom from 1714 to 1901

* things relating to;

** Electorate of Hanover

** Kingdom of Hanover

** Province of ...

government.

Other motives of the Loyalists included:

* They felt a need for order and believed that Parliament was the legitimate authority.

* In New York, powerful families had assembled colony-wide coalitions of supporters; the de Lancey family

The de Lancey family was a distinguished colonial American and British political and military family.

History

Of French origin, the de Lancey family was a Huguenot cadet branch of the House of Lancy, recognized in 1697 as part of the '' noblesse ...

(of Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , ; ) are a Religious denomination, religious group of French people, French Protestants who held to the Reformed (Calvinist) tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, ...

and New York Dutch

New Netherlanders were residents of New Netherland, the seventeenth-century colonial outpost of the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands on the northeastern coast of North America, centered around New York Harbor, the Hudson Valley, and New ...

ancestry) formed De Lancey's Brigade

De Lancey's Brigade, also known as De Lancey's Volunteers, De Lancey's Corps, De Lancey's Provincial Corps, De Lancey's Refugees, and the "Cowboys" or "Cow-boys", was a Loyalist British provincial military unit, raised for service during the Ame ...

with support from its associates.

* They felt weak or threatened within American society and in need of an outside defender such as the British Crown and Parliament.

* Black Loyalist

Black Loyalists were people of African descent who sided with Loyalists during the American Revolutionary War. In particular, the term referred to men enslaved by Patriots who served on the Loyalist side because of the Crown's guarantee of fr ...

s were promised freedom from slavery by the British.

Demographics

Historian Robert Calhoon wrote in 2000, concerning the proportion of Loyalists to Patriots in the Thirteen Colonies: Before Calhoon's work, estimates of the Loyalist share of the population were somewhat higher, at about one-third, but these estimates are now rejected as too high by most scholars. In 1968 historian Paul H. Smith estimated there were about 400,000 Loyalists, or 16% of the white population of 2.25 million in 1780.

Historian

Before Calhoon's work, estimates of the Loyalist share of the population were somewhat higher, at about one-third, but these estimates are now rejected as too high by most scholars. In 1968 historian Paul H. Smith estimated there were about 400,000 Loyalists, or 16% of the white population of 2.25 million in 1780.

Historian Robert Middlekauff

Robert Lawrence Middlekauff (July 5, 1929 – March 10, 2021) was a professor of colonial and early United States history at the University of California, Berkeley.

Career

In 1983, Middlekauff became the President of Huntington Library, Art ...

summarizes scholarly research on the nature of Loyalist support as follows:

The largest number of loyalists were found in theAfter the British military capture of New York City and Long Island it became the British military and political base of operations in North America from 1776 to 1783, prompting revolutionaries to flee and resulting in a large concentration of Loyalists, many of whom were refugees from other states.Calhoon (1973) According to Calhoon, Loyalists tended to be older and wealthier, but there were also many Loyalists of humble means. Many activemiddle colonies The Middle Colonies were a subset of the Thirteen Colonies in British America, located between the New England Colonies and the Southern Colonies. Along with the Chesapeake Colonies, this area now roughly makes up the Mid-Atlantic states. Muc ...: manytenant farmer A tenant farmer is a farmer or farmworker who resides and works on land owned by a landlord, while tenant farming is an agricultural production system in which landowners contribute their land and often a measure of operating capital and ma ...s of New York supported the king, for example, as did many of theDutch Dutch or Nederlands commonly refers to: * Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands ** Dutch people as an ethnic group () ** Dutch nationality law, history and regulations of Dutch citizenship () ** Dutch language () * In specific terms, i ...in the colony and inNew Jersey New Jersey is a U.S. state, state located in both the Mid-Atlantic States, Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern United States, Northeastern regions of the United States. Located at the geographic hub of the urban area, heavily urbanized Northeas .... TheGermans Germans (, ) are the natives or inhabitants of Germany, or sometimes more broadly any people who are of German descent or native speakers of the German language. The Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany, constitution of Germany, imple ...inPennsylvania Pennsylvania, officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a U.S. state, state spanning the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern United States, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes region, Great Lakes regions o ...tried to stay out of the Revolution, just as manyQuakers Quakers are people who belong to the Religious Society of Friends, a historically Protestantism, Protestant Christian set of Christian denomination, denominations. Members refer to each other as Friends after in the Bible, and originally ...did, and when that failed, clung to the familiar connection rather than embrace the new. Highland Scots in theCarolinas The Carolinas, also known simply as Carolina, are the U.S. states of North Carolina and South Carolina considered collectively. They are bordered by Virginia to the north, Tennessee to the west, and Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the southwes ..., a fair number of Anglican clergy and their parishioners inConnecticut Connecticut ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York (state), New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. ...and New York, a fewPresbyterians Presbyterianism is a historically Reformed Protestant tradition named for its form of church government by representative assemblies of elders, known as "presbyters". Though other Reformed churches are structurally similar, the word ''Pr ...in thesouthern colonies The Southern Colonies within British America consisted of the Province of Maryland, the Colony of Virginia, the Province of Carolina (in 1712 split into North and South Carolina), and the Province of Georgia. In 1763, the newly created colonies ..., and a large number of theIroquois The Iroquois ( ), also known as the Five Nations, and later as the Six Nations from 1722 onwards; alternatively referred to by the Endonym and exonym, endonym Haudenosaunee ( ; ) are an Iroquoian languages, Iroquoian-speaking Confederation#Ind ...stayed loyal to the king.

Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the State religion#State churches, established List of Christian denominations, Christian church in England and the Crown Dependencies. It is the mother church of the Anglicanism, Anglican Christian tradition, ...

members became Loyalists. Some recent arrivals from Britain, especially those from Scotland, had a high Loyalist proportion. Loyalists in the southern colonies were suppressed by the local Patriots, who controlled local and state government. Many people—including former Regulators in North Carolina—refused to join the rebellion, as they had earlier protested against corruption by local authorities who later became Revolutionary leaders. The oppression by the local Whigs during the Regulation led to many of the residents of backcountry North Carolina sitting out the Revolution or siding with the Loyalists.

In areas under Patriot control, Loyalists were subject to confiscation

Confiscation (from the Latin ''confiscatio'' "to consign to the ''fiscus'', i.e. transfer to the treasury") is a legal form of search and seizure, seizure by a government or other public authority. The word is also used, popularly, of Tampering w ...

of property, and outspoken supporters of the king were threatened with public humiliation such as tarring and feathering

Tarring and feathering is a form of public torture where a victim is stripped naked, or stripped to the waist, while wood tar (sometimes hot) is either poured or painted onto the person. The victim then either has feathers thrown on them or is r ...

or physical attack. It is not known how many Loyalist civilians were harassed by the Patriots, but the treatment was a warning to other Loyalists not to take up arms. In September 1775, William Drayton

William Drayton (December 30, 1776May 24, 1846) was an American politician, banker, and writer who grew up in Charleston, South Carolina. He was the son of William Drayton Sr., who served as justice of the Province of East Florida (1765–1780 ...

and Loyalist leader Colonel Thomas Fletchall signed a treaty of neutrality in the interior community of Ninety Six, South Carolina

Ninety Six is a town in Greenwood County, South Carolina, United States, located approximately 9 miles northeast of the county seat, Greenwood, South Carolina, Greenwood. As of the 2020 census, the town had a population of 2,076, making it the ...

. For actively aiding the British army when it occupied Philadelphia, two residents of the city were tried for treason, convicted, and executed by returning Patriot forces.

Black Loyalists

As a result of the looming crisis in 1775, Royal

As a result of the looming crisis in 1775, Royal Governor of Virginia

The governor of the Commonwealth of Virginia is the head of government of the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Virginia. The Governor (United States), governor is head of the Government_of_Virginia#Executive_branch, executive branch ...

Lord Dunmore

Earl of Dunmore is a title in the Peerage of Scotland.

The title Earl of Dunmore was created in 1686 for Lord Charles Murray, son of John Murray, 1st Marquess of Atholl. The title passed down through generations, with various earls serving ...

issued a proclamation that promised freedom to indentured servants and slaves who were able to bear arms and join his Loyalist Ethiopian Regiment

The Royal Ethiopian Regiment, also known as Lord Dunmore's Ethiopian Regiment, was a British military unit formed of "indentured servants, negros or others" organized after the April 1775 outbreak of the American Revolution by the Earl of Dunmor ...

. Many of the slaves in the South joined the Loyalists with intentions of gaining freedom and escaping the South. African-Americans

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from any of the Black racial groups of Africa. ...

were often the first to come forward to volunteer, and a total of 12,000 African Americans served with the British from 1775 to 1783. This forced the Patriots to also offer freedom to those who would serve in the Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies representing the Thirteen Colonies and later the United States during the American Revolutionary War. It was formed on June 14, 1775, by a resolution passed by the Second Continental Co ...

, with thousands of Black Patriot

Black Patriots were African Americans who sided with the colonists who opposed British rule during the American Revolution. The term ''Black Patriots'' includes, but is not limited to, the 5,000 or more African Americans who served in the Contin ...

s serving.

Women

While men were out fighting for the Crown, women served at home protecting their land and property. At the end of the war, many Loyalist men left America for the shelter of England, leaving their wives and daughters to protect their land. The main punishment for Loyalist families was the expropriation of property, but married women were protected under "feme covert

Coverture was a legal doctrine in English common law under which a married woman's legal existence was considered to be merged with that of her husband. Upon marriage, she had no independent legal existence of her own, in keeping with society's ...

", which meant that they had no political identity and their legal rights were absorbed by their husbands. This created an awkward dilemma for the confiscation committees: confiscating the land of such a woman would punish her for her husband's actions. In many cases, the women did not get a choice on if they were labeled a Loyalist or a Patriot; the label was dependent on their husband's political association. However, some women showed their loyalty to the Crown by continually purchasing British goods, writing it down, and showing resistance to the Patriots. Grace Growden Galloway recorded the experience in her diary. Her writings show the difficulties that her family faced during the revolution. Galloway's property was seized by the Patriots, and she spent the rest of her life fighting to regain it. It was returned to her heirs in 1783, after she and her husband had died.

Patriots allowed women to become involved in politics in a larger scale than the Loyalists. Some women involved in political activity include Catharine Macaulay and Mercy Otis Warren who were both writers. Both women maintained a 20-year friendship although they wrote about different sides of the war; Macaulay wrote from a Loyalist British perspective whereas Warren wrote about her support for the American Revolution. Macaulay's work include ''History of England'' and Warren wrote ''History of the Rise'', ''Progress'', and ''Termination of the American Revolution.'' Although both women's works were unpopular during this time, it pushed them to learn from social critique.

Canada and Nova Scotia

Patriot agents were active in

Patriot agents were active in Quebec

Quebec is Canada's List of Canadian provinces and territories by area, largest province by area. Located in Central Canada, the province shares borders with the provinces of Ontario to the west, Newfoundland and Labrador to the northeast, ...

(which was then frequently called "Canada", the name of the earlier French province) in the months leading to the outbreak of active hostilities. John Brown John Brown most often refers to:

*John Brown (abolitionist) (1800–1859), American who led an anti-slavery raid on Harpers Ferry, Virginia, in 1859

John Brown or Johnny Brown may also refer to:

Academia

* John Brown (educator) (1763–1842), Ir ...

, an agent of the Boston Committee of Correspondence, worked with Canadian merchant Thomas Walker and other Patriot sympathisers during the winter of 1774–75 to convince inhabitants to support the actions of the First Continental Congress

The First Continental Congress was a meeting of delegates of twelve of the Thirteen Colonies held from September 5 to October 26, 1774, at Carpenters' Hall in Philadelphia at the beginning of the American Revolution. The meeting was organized b ...

. However, many of Quebec's inhabitants remained neutral, resisting service to either the British or the Americans.

Although some Canadians took up arms in support of the revolution, the majority remained loyal to the king. French Canadians

French Canadians, referred to as Canadiens mainly before the nineteenth century, are an ethnic group descended from French colonists first arriving in France's colony of Canada in 1608. The vast majority of French Canadians live in the provi ...

had been satisfied by the British government's Quebec Act

The Quebec Act 1774 ( 14 Geo. 3. c. 83) () was an act of the Parliament of Great Britain which set procedures of governance in the Province of Quebec. One of the principal components of the act was the expansion of the province's territory t ...

of 1774, which offered religious and linguistic toleration; in general, they did not sympathize with a revolution that they saw as being led by Protestants from New England, who were their commercial rivals and hereditary enemies. Most of the English-speaking settlers had arrived following the British conquest of Canada

The conquest of New France () was the military conquest of New France by Great Britain during the French and Indian War. It started with a British campaign in 1758 and ended with the region being put under a British military regime between 1760 ...

in 1759–60 and were unlikely to support separation from Britain. The older British colonies, Newfoundland and Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada, located on its east coast. It is one of the three Maritime Canada, Maritime provinces and Population of Canada by province and territory, most populous province in Atlan ...

(including what is now New Brunswick) also remained loyal and contributed military forces in support of the Crown.

In late 1775 the Continental Army sent a force into Quebec, led by General Richard Montgomery

Richard Montgomery (2 December 1738 – 31 December 1775) was an Irish-born American military officer who first served in the British Army. He later became a major general in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War, and ...

and Colonel Benedict Arnold

Benedict Arnold (#Brandt, Brandt (1994), p. 4June 14, 1801) was an American-born British military officer who served during the American Revolutionary War. He fought with distinction for the American Continental Army and rose to the rank of ...

, with the goal of convincing the residents of Quebec to join the revolution. Although only a minority of Canadians openly expressed loyalty to King George, about 1,500 militia fought for the king in the siege of Fort St. Jean

The siege of Fort St. Jean (September 17 – November 3, 1775 ) was conducted by American Brigadier General Richard Montgomery on the town and fort of Saint-Jean, also called ''St. John'', ''St. Johns'', or ''St. John's'', in the British provi ...

. In the region south of Montreal

Montreal is the List of towns in Quebec, largest city in the Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Quebec, the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, second-largest in Canada, and the List of North American cit ...

which was occupied by the Continentals, some inhabitants supported the revolution and raised two regiments to join the Patriot forces.Mason Wade, ''The French Canadians'' (1955) 1:67–69.

In Nova Scotia, there were many Yankee

The term ''Yankee'' and its contracted form ''Yank'' have several interrelated meanings, all referring to people from the United States. Their various meanings depend on the context, and may refer to New Englanders, the Northeastern United Stat ...

settlers originally from New England, and they generally supported the principles of the revolution. The allegiance toward the revolution waned as American privateers raided Nova Scotia communities throughout the war. The Nova Scotia government used the law to convict people for sedition and treason for supporting the Patriot cause. There was also the influence of an influx of recent immigration from the British isles, and they remained neutral during the war, and the influx was greatest in Halifax. Britain in any case built up powerful forces at the naval base of Halifax after the failure of Jonathan Eddy

Jonathan Eddy (–1804) was an American military officer and politician who served in the French and Indian War and the American Revolutionary War. After the French and Indian War, he settled in Nova Scotia as a New England Planter, becoming a m ...

to capture Fort Cumberland in 1776.

Military operations

The Loyalists rarely attempted any political organization. They were often passive unless regular British army units were in the area. The British, however, assumed a highly activist Loyalist community was ready to mobilize and planned much of their strategy around raising Loyalist regiments. The British provincial line, consisting of Americans enlisted on a regular army status, enrolled 19,000 Loyalists (50 units and 312 companies). The maximum strength of the Loyalist provincial line was 9,700 in December 1780.Calhoon 502. In all about 19,000 at one time or another were soldiers or militia in British forces. In the opening months of the Revolutionary War, the Patriots laid siege toBoston

Boston is the capital and most populous city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. The city serves as the cultural and Financial centre, financial center of New England, a region of the Northeas ...

, where most of the British forces were stationed. Elsewhere there were few British troops, and the Patriots seized control of all levels of government, as well as supplies of arms and gunpowder. Vocal Loyalists recruited people to their side, often with the encouragement and assistance of royal governors. In the South Carolina backcountry, Loyalist recruitment outstripped that of Patriots. A brief siege at Ninety Six, South Carolina

Ninety Six is a town in Greenwood County, South Carolina, United States, located approximately 9 miles northeast of the county seat, Greenwood, South Carolina, Greenwood. As of the 2020 census, the town had a population of 2,076, making it the ...

in the fall of 1775 was followed by a rapid rise in Patriot recruiting. In what became known as the Snow Campaign

The Snow Campaign was one of the first major military operations of the American Revolutionary War in the southern colonies. An army of up to 3,000 Patriot militia under Colonel Richard Richardson marched against Loyalist recruiting centers in ...

, partisan militia arrested or drove out most of the backcountry Loyalist leadership. North Carolina backcountry Scots and former Regulators

Regulator may refer to:

Technology

* Regulator (automatic control), a device that maintains a designated characteristic, as in:

** Battery regulator

** Pressure regulator

** Diving regulator

** Voltage regulator

* Regulator (sewer), a control de ...

joined forces in early 1776, but they were broken as a force at the Battle of Moore's Creek Bridge

The Battle of Moore's Creek Bridge was a minor conflict of the American Revolutionary War fought near Wilmington, North Carolina, Wilmington (present-day Pender County, North Carolina, Pender County), North Carolina, on February 27, 1776. The v ...

. Loyalists from South Carolina fought for the British in the Battle of Camden

The Battle of Camden (August 16, 1780), also known as the Battle of Camden Court House, was a major victory for the Kingdom of Great Britain, British in the Southern theater of the American Revolutionary War. On August 16, 1780, British forces ...

. The British forces at the Battle of Monck's Corner

The Battle of Monck's Corner was fought on April 14, 1780, outside of Charleston, South Carolina, which was under siege by British forces under the command of General Sir Henry Clinton in the American Revolutionary War. The British Legion, un ...

and the Battle of Lenud's Ferry

The Battle of Lenud's Ferry () was a battle of the American Revolutionary War that was fought on May 6, 1780 in present-day Berkeley County, South Carolina.

All of the British soldiers who took part in the Battle of Lenud's Ferry were in fact Lo ...

consisted entirely of Loyalists with the exception of their commanding officer Banastre Tarleton

General Sir Banastre Tarleton, 1st Baronet (21 August 175415 January 1833) was a British military officer and politician. He is best known as the lieutenant colonel leading the British Legion at the end of the American Revolutionary War. He lat ...

. Both white and black Loyalists fought for the British at the Battle of Kemp's Landing

The Battle of Kemp's Landing, also known as the Skirmish of Kempsville, was a skirmish in the American Revolutionary War that occurred on November 15, 1775. Militia companies from Princess Anne County in the Province of Virginia assembled at K ...

in Virginia.

By July 4, 1776, the Patriots had gained control of virtually all territory in the Thirteen Colonies and had expelled all royal officials. No one who openly proclaimed their loyalty to the Crown was allowed to remain, so Loyalists fled or kept quiet. Some of those who remained later gave aid to invading British armies or joined uniformed Loyalist regiments. The British were forced out of Boston by March 17, 1776. They regrouped at Halifax and attacked New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

New York may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* ...

in August, defeating George Washington

George Washington (, 1799) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the first president of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797. As commander of the Continental Army, Washington led Patriot (American Revoluti ...

's army at Long Island

Long Island is a densely populated continental island in southeastern New York (state), New York state, extending into the Atlantic Ocean. It constitutes a significant share of the New York metropolitan area in both population and land are ...

and capturing New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

and its vicinity, and they occupied the mouth of the Hudson River

The Hudson River, historically the North River, is a river that flows from north to south largely through eastern New York (state), New York state. It originates in the Adirondack Mountains at Henderson Lake (New York), Henderson Lake in the ...

until 1783. British forces seized control of other cities, including Philadelphia

Philadelphia ( ), colloquially referred to as Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, most populous city in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania and the List of United States cities by population, sixth-most populous city in the Unit ...

(1777), Savannah, Georgia

Savannah ( ) is the oldest city in the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia and the county seat of Chatham County, Georgia, Chatham County. Established in 1733 on the Savannah River, the city of Savannah became the Kingdom of Great Brita ...

(1778–83), and Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston is the List of municipalities in South Carolina, most populous city in the U.S. state of South Carolina. The city lies just south of the geographical midpoint of South Carolina's coastline on Charleston Harbor, an inlet of the Atla ...

(1780–82). But 90% of the colonial population lived outside the cities, with the effective result that Congress represented 80 to 90 percent of the population. The British removed their governors from colonies where the Patriots were in control, but Loyalist civilian government was re-established in coastal Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the South Caucasus

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the southeastern United States

Georgia may also refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Georgia (name), a list of pe ...

Georgia Encyclopædia. from 1779 to 1782, despite the presence of Patriot forces in the northern part of Georgia. Essentially, the British were only able to maintain power in areas where they had a strong military presence. Black Loyalists helped rout the Virginia militia at the

Battle of Kemp's Landing

The Battle of Kemp's Landing, also known as the Skirmish of Kempsville, was a skirmish in the American Revolutionary War that occurred on November 15, 1775. Militia companies from Princess Anne County in the Province of Virginia assembled at K ...

and fought in the Battle of Great Bridge

The Battle of Great Bridge was fought December 9, 1775, in the area of Great Bridge, Virginia, early in the American Revolutionary War. The refusal by colonial Virginia militia forces led to the departure of Royal Governor Lord Dunmore and any ...

on the Elizabeth River, wearing the motto "Liberty to Slaves", but this time they were defeated. The remnants of their regiment were then involved in the evacuation of Norfolk

Norfolk ( ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in England, located in East Anglia and officially part of the East of England region. It borders Lincolnshire and The Wash to the north-west, the North Sea to the north and eas ...

, after which they served in the Chesapeake Chesapeake most often refers to:

*Chesapeake people, a Native American tribe also known as the Chesepian

*Chesapeake Bay

*Delmarva Peninsula, also known as the Chesapeake Peninsula

Chesapeake may also refer to:

Populated places In Virginia

* ...

area. Eventually the camp that they had set up there suffered an outbreak of smallpox and other diseases. This took a heavy toll, putting many of them out of action for some time. The survivors joined other Loyalist units and continued to serve throughout the war.

In Canada, although the Continentals captured Montreal in November 1775, they were turned back a month later at Quebec City

Quebec City is the capital city of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Quebec. As of July 2021, the city had a population of 549,459, and the Census Metropolitan Area (including surrounding communities) had a populati ...

by a combination of the British military under Governor Guy Carleton, the difficult terrain and weather, and an indifferent local response. The Continental forces would be driven from Quebec in 1776, after the breakup of ice on the St. Lawrence River

The St. Lawrence River (, ) is a large international river in the middle latitudes of North America connecting the Great Lakes to the North Atlantic Ocean. Its waters flow in a northeasterly direction from Lake Ontario to the Gulf of St. Lawren ...

and the arrival of British transports in May and June. There would be no further serious attempt to challenge British control of present-day Canada until the War of 1812

The War of 1812 was fought by the United States and its allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom and its allies in North America. It began when the United States United States declaration of war on the Uni ...

. In 1777, 1,500 Loyalist militia took part in the Saratoga campaign

The Saratoga campaign in 1777 was an attempt by the British to gain military control of the strategically important Hudson River valley during the American Revolutionary War. It ended in the surrender of a British army, which historian Edmund M ...

in New York, and surrendered with General Burgoyne after the Battles of Saratoga

The Battles of Saratoga (September 19 and October 7, 1777) were two battles between the American Continental Army and the British Army fought near Saratoga, New York, concluding the Saratoga campaign in the American Revolutionary War. The seco ...

in October. For the rest of the war, Quebec acted as a base for raiding expeditions, conducted primarily by Loyalists and Indians, against frontier communities.

Aftermath of the American Revolution

Emigration

Estimates for how many Loyalists emigrated after the war differ. HistorianMaya Jasanoff

Maya R. Jasanoff (born 1974) is an American scholar of history studies who serves as Coolidge Professor of History at Harvard University, where she focuses on the history of Britain and the British Empire.

Early life

Jasanoff grew up in Ithaca ...

calculates 60,000 in total went to British North America, including about 50,000 whites. Philip Ranlet estimates 20,000 adult white Loyalists went to Canada, while Wallace Brown cites about 80,000 Loyalists in total permanently left the United States.

According to Jasanoff, about 36,000 Loyalists went to New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, while about 6,600 went to Quebec and 2,000 to Prince Edward Island

Prince Edward Island is an island Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada. While it is the smallest province by land area and population, it is the most densely populated. The island has several nicknames: "Garden of the Gulf", ...

. About 5,090 white Loyalists went to Florida, bringing along their slaves who numbered about 8,285 (421 whites and 2,561 blacks returned to the US from Florida). When Florida was returned to Spain, however, very few Loyalists remained there. Approximately 6,000 whites went to Jamaica and other Caribbean islands, notably the Bahama Islands, and about 13,000 went to Britain (including 5,000 free blacks).

A precise figure cannot be known because the records were incomplete and inaccurate, and small numbers continued to leave after 1783. The 50,000 or so white departures represented about 10% of the Loyalists (at 20–25% of the white population). Loyalists (especially soldiers and former officials) could choose evacuation. Loyalists whose roots were not yet deeply embedded in the United States were more likely to leave; older people who had familial bonds and had acquired friends, property, and a degree of social respectability were more likely to remain in the US. The vast majority of the half-million white Loyalists, about 20–25% of the total number of whites, remained in the US. Starting in the mid-1780s a small percentage of those who had left returned to the United States. The exiles amounted to about 2% of the total US population of 3 million at the end of the war in 1783.

After 1783 some former Loyalists, especially Germans from Pennsylvania, emigrated to Canada to take advantage of the British government's offer of free land. Many departed the fledgling United States because they faced continuing hostility. In another migration-motivated mainly by economic rather than political reasons- more than 20,000 and perhaps as many as 30,000 "Late Loyalists" arrived in Ontario in the 1790s attracted by Lieutenant-Governor Simcoe's policy of land and low taxes, one-fifth those in the US and swearing an oath of allegiance to the king.

The 36,000 or so who went to Nova Scotia were not well received by the 17,000 Nova Scotians, who were mostly descendants of New Englanders settled there before the Revolution. "They he Loyalists, Colonel Thomas Dundas wrote in 1786, "have experienced every possible injury from the old inhabitants of Nova Scotia, who are even more disaffected towards the British Government than any of the new States ever were. This makes me much doubt their remaining long dependent." In response, the colony of New Brunswick

New Brunswick is a Provinces and Territories of Canada, province of Canada, bordering Quebec to the north, Nova Scotia to the east, the Gulf of Saint Lawrence to the northeast, the Bay of Fundy to the southeast, and the U.S. state of Maine to ...

, until 1784 part of Nova Scotia, was created for the 14,000 who had settled in those parts. Of the 46,000 who went to Canada, 10,000 went to Quebec, especially what is now modern-day Ontario

Ontario is the southernmost Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada. Located in Central Canada, Ontario is the Population of Canada by province and territory, country's most populous province. As of the 2021 Canadian census, it ...

, the rest to Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island.

Realizing the importance of some type of consideration, on November 9, 1789, Governor of Quebec Lord Dorchester

Guy Carleton, 1st Baron Dorchester (3 September 1724 – 10 November 1808), known between 1776 and 1786 as Sir Guy Carleton, was a British Army officer and colonial administrator. He twice served as Governor of the Province of Quebec, from 176 ...

declared that it was his wish to "put the mark of Honour upon the Families who had adhered to the Unity of the Empire." As a result of Dorchester's statement, the printed militia rolls carried the notation:

Those Loyalists who have adhered to the Unity of the Empire, and joined the Royal Standard before the Treaty of Separation in the year 1783, and all their Children and their Descendants by either sex, are to be distinguished by the following Capitals, affixed to their names: U.E. Alluding to their great principle The Unity of the Empire.The

post-nominals

Post-nominal letters, also called post-nominal initials, post-nominal titles, designatory letters, or simply post-nominals, are letters placed after a person's name to indicate that the individual holds a position, an academic degree, accreditation ...

"U.E." are rarely seen today, but the influence of the Loyalists on the evolution of Canada remains. Their ties to Britain and/or their antipathy to the United States provided the strength needed to keep Canada independent and distinct in North America. The Loyalists' basic distrust of republicanism

Republicanism is a political ideology that encompasses a range of ideas from civic virtue, political participation, harms of corruption, positives of mixed constitution, rule of law, and others. Historically, it emphasizes the idea of self ...

and "mob rule

Mob rule or ochlocracy or mobocracy is a pejorative term describing an oppressive majoritarian form of government controlled by the common people through the intimidation of authorities. Ochlocracy is distinguished from democracy or similarl ...

" influenced Canada's gradual path to independence. The new British North American provinces of Upper Canada

The Province of Upper Canada () was a Province, part of The Canadas, British Canada established in 1791 by the Kingdom of Great Britain, to govern the central third of the lands in British North America, formerly part of the Province of Queb ...

(the forerunner of Ontario) and New Brunswick

New Brunswick is a Provinces and Territories of Canada, province of Canada, bordering Quebec to the north, Nova Scotia to the east, the Gulf of Saint Lawrence to the northeast, the Bay of Fundy to the southeast, and the U.S. state of Maine to ...

were founded as places of refuge for the United Empire Loyalists.

In an interesting historical twist Peter Matthews, a son of Loyalists, participated in the Upper Canada Rebellion

The Upper Canada Rebellion was an insurrection against the Oligarchy, oligarchic government of the British colony of Upper Canada (present-day Ontario) in December 1837. While public grievances had existed for years, it was the Lower Canada Rebe ...

which sought relief from oligarchic British colonial government and pursued American style republicanism. He was arrested, tried and executed in Toronto

Toronto ( , locally pronounced or ) is the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, most populous city in Canada. It is the capital city of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Ontario. With a p ...

, and later became heralded as a patriot to the movement which led to Canadian self-governance.

The wealthiest and most prominent Loyalist exiles went to Great Britain to rebuild their careers; many received pensions. Many Southern Loyalists, taking along their slaves, went to the West Indies

The West Indies is an island subregion of the Americas, surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea, which comprises 13 independent island country, island countries and 19 dependent territory, dependencies in thr ...

, particularly to the Abaco Islands

The Abaco Islands lie in the north of Bahamas, The Bahamas, about 193 miles (167.7 nautical miles or 310.6 km) east of Miami, Florida, US. The main islands are Great Abaco and Little Abaco, which is just west of Great Abaco's northern tip.

T ...

in the Bahamas

The Bahamas, officially the Commonwealth of The Bahamas, is an archipelagic and island country within the Lucayan Archipelago of the Atlantic Ocean. It contains 97 per cent of the archipelago's land area and 88 per cent of its population. ...

. Certain Loyalists who fled the United States brought their slaves with them to Canada (mostly to areas that later became Ontario and New Brunswick) where slavery was legal. An imperial law in 1790 assured prospective immigrants to Canada that their slaves would remain their property. However, a law enacted by eminent British lieutenant general and founder of modern Toronto

Toronto ( , locally pronounced or ) is the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, most populous city in Canada. It is the capital city of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Ontario. With a p ...

John Graves Simcoe

Lieutenant-General (United Kingdom), Lieutenant-General John Graves Simcoe (25 February 1752 – 26 October 1806) was a British army officer, politician and colonial administrator who served as the lieutenant governor of Upper Canada from 1791 u ...

in 1793 entitled the Act Against Slavery

The ''Act Against Slavery'' was an anti-slavery law passed on July 9, 1793, in the second legislative session of Upper Canada, the colonial division of British North America that would eventually become Ontario. It banned the importation of s ...

tried to suppress slavery in Upper Canada by halting the sale of slaves to the United States, and by freeing slaves upon their escape from the latter into Canada. Simcoe desired to demonstrate the merits of loyalism

Loyalism, in the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and its former colonies, refers to the allegiance to the British crown or the United Kingdom. In North America, the most common usage of the term refers to loyalty to the British Cr ...

and abolitionism

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was France in 1315, but it was later used in its colonies. ...

in Upper Canada in contrast to the nascent republicanism and prominence of slavery in the United States

The legal institution of human chattel slavery, comprising the enslavement primarily of List of ethnic groups of Africa, Africans and African Americans, was prevalent in the United States of America from its founding in 1776 until 1865 ...

, and, according to historian Stanley R. Mealing:

However the actual law was a compromise. According to historian Afua Cooper, Simcoe's law required children in slavery to be freed when they reached age 25 and:

Thousands of Iroquois

The Iroquois ( ), also known as the Five Nations, and later as the Six Nations from 1722 onwards; alternatively referred to by the Endonym and exonym, endonym Haudenosaunee ( ; ) are an Iroquoian languages, Iroquoian-speaking Confederation#Ind ...

and other Native Americans were expelled from New York and other states and resettled in Canada. The descendants of one such group of Iroquois, led by Joseph Brant

Thayendanegea or Joseph Brant (March 1743 – November 24, 1807) was a Mohawk military and political leader, based in present-day New York and, later, Brantford, in what is today Ontario, who was closely associated with Great Britain du ...

(Thayendenegea), settled at Six Nations of the Grand River

Six Nations (or Six Nations of the Grand River) is demographically the largest First Nations reserve in Canada. As of the end of 2017, it has a total of 27,276 members, 12,848 of whom live on the reserve. The six nations of the Iroquois Confederacy ...

, the largest First Nations

First nations are indigenous settlers or bands.

First Nations, first nations, or first peoples may also refer to:

Indigenous groups

*List of Indigenous peoples

*First Nations in Canada, Indigenous peoples of Canada who are neither Inuit nor Mé ...

reserve

Reserve or reserves may refer to:

Places

* Reserve, Kansas, a US city

* Reserve, Louisiana, a census-designated place in St. John the Baptist Parish

* Reserve, Montana, a census-designated place in Sheridan County

* Reserve, New Mexico, a US v ...

in Canada. (The remainder, under the leadership of Cornplanter

John Abeel III (–February 18, 1836) known as Gaiänt'wakê (''Gyantwachia'' – "the planter") or Kaiiontwa'kon (''Kaintwakon'' – "By What One Plants") in the Seneca language and thus generally known as Cornplanter, was a Dutch- Seneca ch ...

(John Abeel) and members of his family, stayed in New York.) A group of African-American Loyalists settled in Nova Scotia but emigrated again for Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone, officially the Republic of Sierra Leone, is a country on the southwest coast of West Africa. It is bordered to the southeast by Liberia and by Guinea to the north. Sierra Leone's land area is . It has a tropical climate and envi ...

after facing discrimination there.

Many of the Loyalists were forced to abandon substantial properties to America restoration of or compensation for these lost properties, which was a major issue during the negotiation of the Jay Treaty

The Treaty of Amity, Commerce, and Navigation, Between His Britannic Majesty and the United States of America, commonly known as the Jay Treaty, and also as Jay's Treaty, was a 1794 treaty between the United States and Great Britain that averted ...

in 1794. Two successive boards were formed, and under a new convention signed in 1802 by the United States and Great Britain for the mutual payment of claims, the US paid the sum of £600,000, while only £1,420,000 of nearly £5 million in claims considered by commissioners in Britain were judged to be good.

For the Black Loyalists, the British honored the pledge of freedom in New York City through the efforts of General Guy Carleton, who recorded the names of African Americans who had supported the British in a document called the Book of Negroes, which granted freedom to slaves who had escaped and assisted the British. About 4,000 Black Loyalists went to the British colonies of Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada, located on its east coast. It is one of the three Maritime Canada, Maritime provinces and Population of Canada by province and territory, most populous province in Atlan ...

and New Brunswick

New Brunswick is a Provinces and Territories of Canada, province of Canada, bordering Quebec to the north, Nova Scotia to the east, the Gulf of Saint Lawrence to the northeast, the Bay of Fundy to the southeast, and the U.S. state of Maine to ...

, where they were promised land grants. They founded communities across the two provinces, many of which still exist today. Over 2,500 settled in Birchtown, Nova Scotia

Birchtown is a community and National Historic Site in the Canadian province of Nova Scotia, located near Shelburne in the Municipal District of Shelburne County. Founded in 1783, the village was the largest settlement of Black Loyalists and ...

, instantly making it the largest free black community in North America. However, the long period of waiting time to be officially given land grants that were given to them and the prejudices of white Loyalists in nearby Shelburne who regularly harassed the settlement in events such as the Shelburne riots

The Shelburne riots were attacks in July 1784 by landless Loyalist veterans of the American War of Independence against Black Loyalists and government officials in the town of Shelburne, Nova Scotia, and the nearby village of Birchtown. They ha ...

in 1784, made life very difficult for the community. In 1791 the Sierra Leone Company

The Sierra Leone Company was the corporate body involved in founding the Freetown, second British colony in Africa on 11 March 1792 through the resettlement of Black Loyalists who had initially been settled in Nova Scotia (the Nova Scotian Settler ...

offered to transport dissatisfied black Loyalists to the nascent colony of Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone, officially the Republic of Sierra Leone, is a country on the southwest coast of West Africa. It is bordered to the southeast by Liberia and by Guinea to the north. Sierra Leone's land area is . It has a tropical climate and envi ...

in West Africa, with the promise of better land and more equality. About 1,200 left Nova Scotia for Sierra Leone, where they named the capital Freetown

Freetown () is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Sierra Leone. It is a major port city on the Atlantic Ocean and is located in the Western Area of the country. Freetown is Sierra Leone's major urban, economic, financial, cultural, e ...

. After 1787 they became Sierra Leone's ruling elite during the colonial era and their descendants, the Sierra Leone Creoles

The Sierra Leone Creole people () are an ethnic group of Sierra Leone. The Sierra Leone Creole people are descendants of freed African-American, Afro-Caribbean, and Liberated African slaves who settled in the Western Area of Sierra Leone betwe ...

, are the cultural elites of the nation. About 400 to 1,000 free blacks who joined the British side in the Revolution went to London and joined the free black community of about 10,000 there.

United States citizens

The great majority of Loyalists never left the United States; they stayed on and were allowed to be citizens of the new country, retaining for a time the earlier designation of "Tories". Some became nationally prominent leaders, includingSamuel Seabury

Samuel Seabury (November 30, 1729February 25, 1796) was the first American Episcopal bishop, the second Presiding Bishop of the Episcopal Church in the United States of America, and the first Bishop of Connecticut. He was a leading Loyalis ...

, who was the first Bishop of the Episcopal Church, and Tench Coxe

Tench Coxe (May 22, 1755July 17, 1824) was an American political economist and a delegate for Pennsylvania to the Continental Congress in 1788–1789. He wrote under the pseudonym "A Pennsylvanian," and was known to his political enemies as ...

. There was a small but significant trickle of returnees who found life in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick too difficult. Perhaps 10% of the refugees to New Brunswick returned to the States as did an unknown number from Nova Scotia. Some Massachusetts Tories settled in the Maine District. Nevertheless, the vast majority never returned. Captain Benjamin Hallowell, who as Mandamus Councilor in Massachusetts served as the direct representative of the Crown, was considered by the insurgents as one of the most hated men in the Colony, but as a token of compensation when he returned from England in 1796, his son was allowed to regain the family house.

In many states, moderate Whigs, who had not been in favor of separation from Britain but preferred a negotiated settlement which would have maintained ties to the Mother Country, aligned with Tories to block radicals. Among these was Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton (January 11, 1755 or 1757July 12, 1804) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the first U.S. secretary of the treasury from 1789 to 1795 dur ...

in 1782–85, to wrest control of New York State from the faction of the George Clinton. Most states had rescinded anti-Tory laws by 1787, although the accusation of being a Tory was heard for another generation. Several hundred who had left for Florida returned to Georgia in 1783–84.

South Carolina, which had seen a bitter bloody internal civil war in 1780–82, adopted a policy of reconciliation that proved more moderate than any other state. About 4,500 white Loyalists left when the war ended, but the majority remained. The state government successfully and quickly reincorporated the vast majority. During the war, pardons were offered to Loyalists who switched sides and joined the Patriot forces. Others were required to pay a 10% fine of the value of the property. The legislature named 232 Loyalists liable for the confiscation of their property, but most appealed and were forgiven.

In Connecticut, much to the disgust of the radical Whigs, the moderate Whigs were advertising in New York newspapers in 1782–83 that Tories who would make no trouble would be welcome on the grounds that their skills and money would help the state's economy. The moderates prevailed; all anti-Tory laws were repealed in early 1783 except for the law relating to confiscated Tory estates: "... the problem of the loyalists after 1783 was resolved in their favor after the War of Independence ended." In 1787 the last of any discriminatory laws were rescinded.

Effect of the departure of Loyalist leaders