London Pact on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Treaty of London (; ) or the Pact of London (, ) was a secret agreement concluded on 26 April 1915 by the

The Treaty of London (; ) or the Pact of London (, ) was a secret agreement concluded on 26 April 1915 by the

The August–September 1914 negotiations between the Entente and Italy were conducted on Russian initiative. On 4 August, only a day after Italy , its ambassador to Russia said that Italy might join the Entente in return for

The August–September 1914 negotiations between the Entente and Italy were conducted on Russian initiative. On 4 August, only a day after Italy , its ambassador to Russia said that Italy might join the Entente in return for

In late October, there was an attempt to get Italy to intervene against an expected Turkish attack against the

In late October, there was an attempt to get Italy to intervene against an expected Turkish attack against the

Grey noted that the Italian claims were excessive, but also that they did not conflict with British interests. He also thought that recent Russian stubborn objections against Greek attack to capture Constantinople could be overcome by addition of Italian troops, and that Italian participation in the war would expedite a decision from Bulgaria and Romania, still waiting to commit to the war.

Sazonov objected to any Italian role regarding Constantinople, seeing it as a threat to Russian control of the city promised by the allies in return for Russian losses in the war. This led Grey to obtain formal recognition of the Russian claim to the city by the Committee of Imperial Defence and by France, leading Sazonov to acquiesce to an agreement with Italy, except he would not consent to Italy taking the Adriatic coast south of the city of

Grey noted that the Italian claims were excessive, but also that they did not conflict with British interests. He also thought that recent Russian stubborn objections against Greek attack to capture Constantinople could be overcome by addition of Italian troops, and that Italian participation in the war would expedite a decision from Bulgaria and Romania, still waiting to commit to the war.

Sazonov objected to any Italian role regarding Constantinople, seeing it as a threat to Russian control of the city promised by the allies in return for Russian losses in the war. This led Grey to obtain formal recognition of the Russian claim to the city by the Committee of Imperial Defence and by France, leading Sazonov to acquiesce to an agreement with Italy, except he would not consent to Italy taking the Adriatic coast south of the city of

Article 1 of the treaty determined that a military agreement shall be concluded to guarantee the number of troops committed by Russia against Austria-Hungary to prevent it from concentrating all its forces against Italy. Article 2 required Italy to enter the war against all enemies of the United Kingdom, Russia, and France, and Article 3 obliged the French and British navies from supporting the Italian war effort by destroying Austro-Hungarian fleet.

Article 4 of the treaty determined that Italy shall receive Trentino, and the

Article 1 of the treaty determined that a military agreement shall be concluded to guarantee the number of troops committed by Russia against Austria-Hungary to prevent it from concentrating all its forces against Italy. Article 2 required Italy to enter the war against all enemies of the United Kingdom, Russia, and France, and Article 3 obliged the French and British navies from supporting the Italian war effort by destroying Austro-Hungarian fleet.

Article 4 of the treaty determined that Italy shall receive Trentino, and the

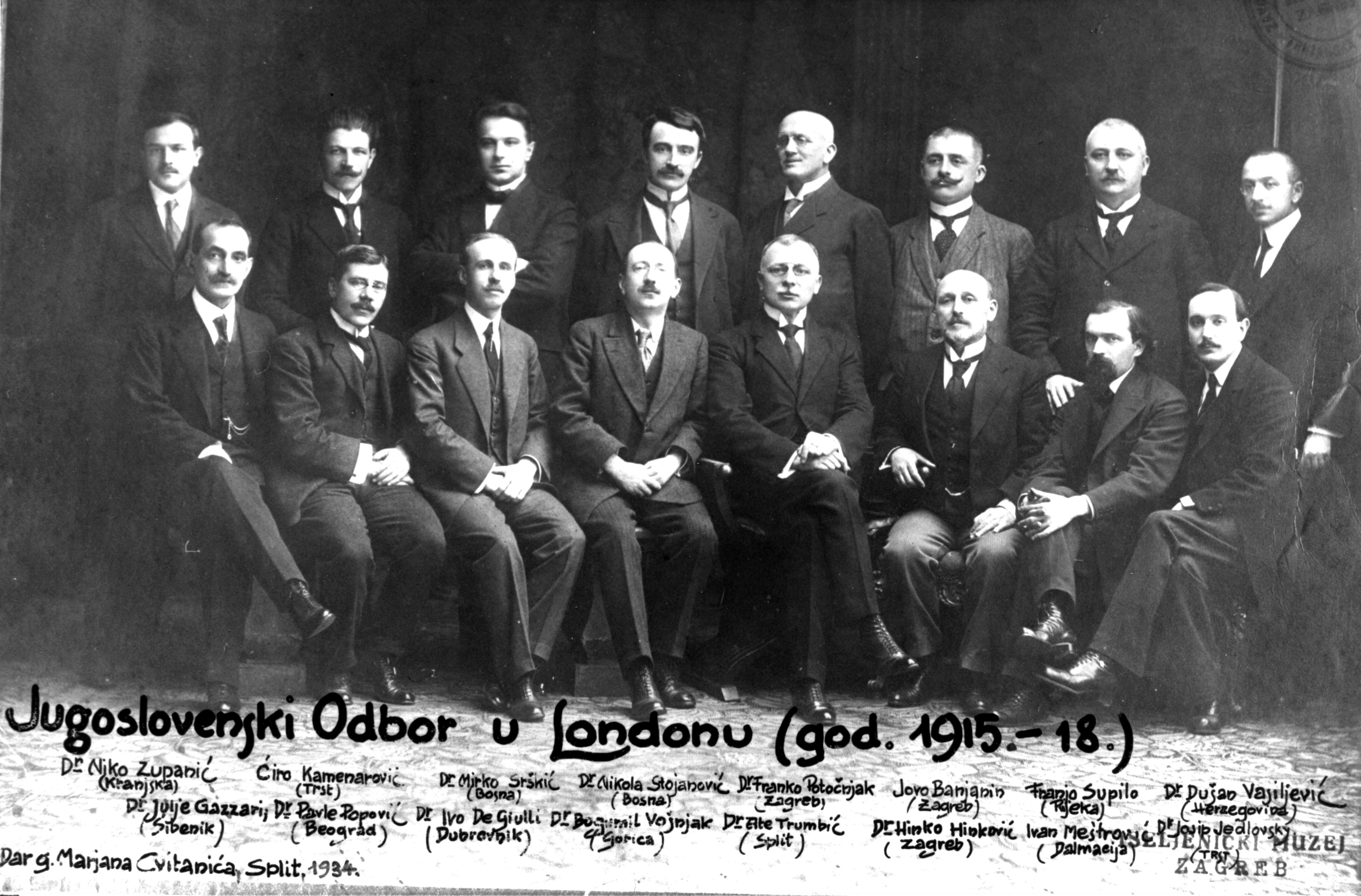

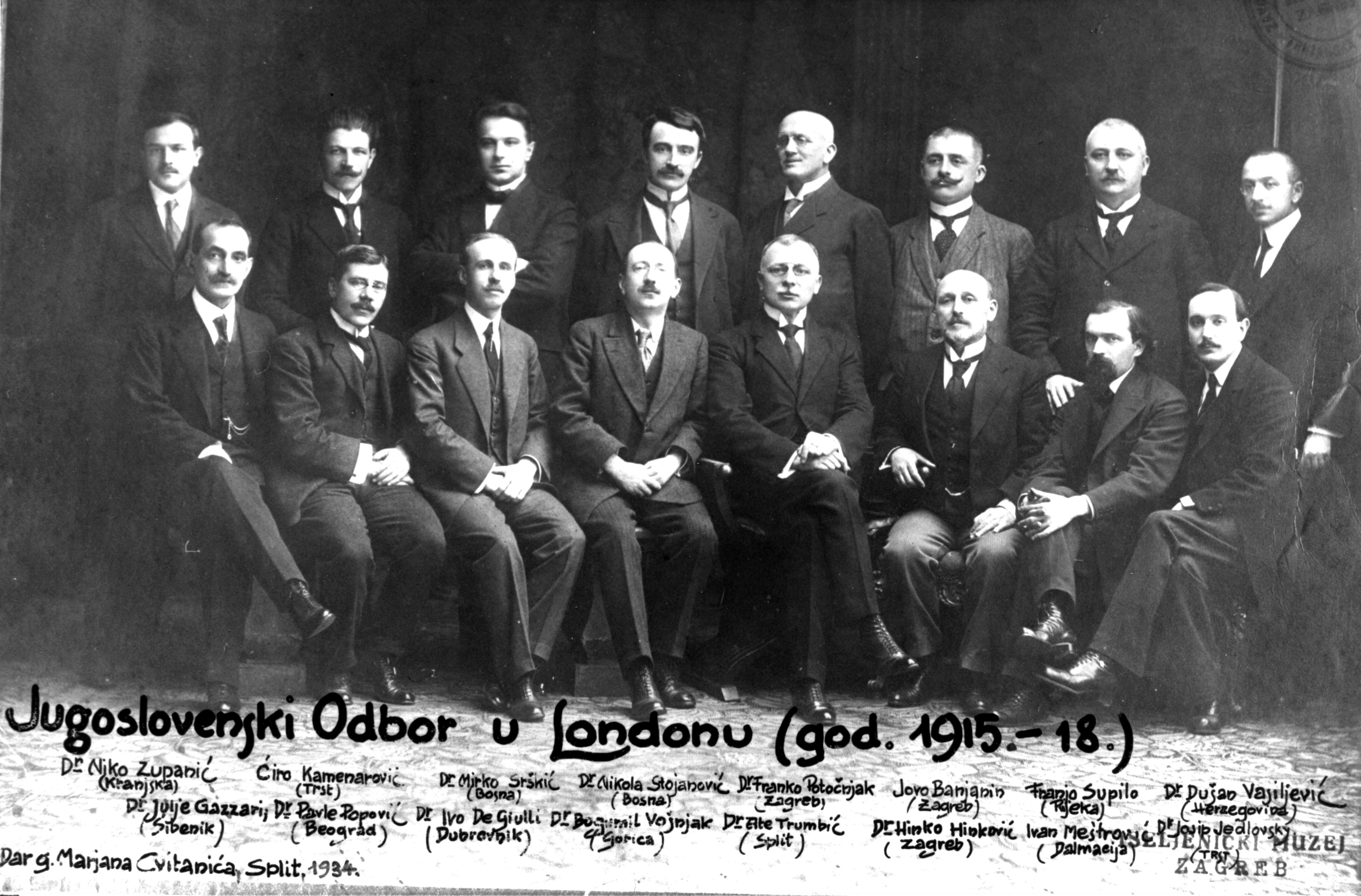

Even though the treaty was meant to be secret, an outline of its provisions became known to the Yugoslav Committee and its supporters in London in late April 1915. Serbia and the Yugoslav Committee protested it in strong terms in Entente capitals. Pašić condemned the disregard for the self-determination principle on which the Niš Declaration rested and the lack of consultations with Serbia. He demanded the Entente refrain from treaties with Hungary or Romania on borders of interest to Croatia without conferring with Serbia first, as well as requesting assurances of future political union of the Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes. Pašić telegraphed his proposal to Grey from the provisional wartime capital of

Even though the treaty was meant to be secret, an outline of its provisions became known to the Yugoslav Committee and its supporters in London in late April 1915. Serbia and the Yugoslav Committee protested it in strong terms in Entente capitals. Pašić condemned the disregard for the self-determination principle on which the Niš Declaration rested and the lack of consultations with Serbia. He demanded the Entente refrain from treaties with Hungary or Romania on borders of interest to Croatia without conferring with Serbia first, as well as requesting assurances of future political union of the Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes. Pašić telegraphed his proposal to Grey from the provisional wartime capital of

In the final weeks before entering the war, internal struggle took place in Italy. National fervour was whipped up by speeches of Gabriele D'Annunzio, who called for war as a measure of national worth and inciting violence against neutralists and the former Prime Minister

In the final weeks before entering the war, internal struggle took place in Italy. National fervour was whipped up by speeches of Gabriele D'Annunzio, who called for war as a measure of national worth and inciting violence against neutralists and the former Prime Minister

Provisions of the Treaty of London were a major point of dispute between Italy and the remaining Entente powers at the Paris Peace Conference. The chief Italian representatives, Prime Minister

Provisions of the Treaty of London were a major point of dispute between Italy and the remaining Entente powers at the Paris Peace Conference. The chief Italian representatives, Prime Minister

The Treaty of London (; ) or the Pact of London (, ) was a secret agreement concluded on 26 April 1915 by the

The Treaty of London (; ) or the Pact of London (, ) was a secret agreement concluded on 26 April 1915 by the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

, France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

, and Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

on the one part, and Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

on the other, in order to entice the last to enter the Great War on the side of the Triple Entente

The Triple Entente (from French meaning "friendship, understanding, agreement") describes the informal understanding between the Russian Empire, the French Third Republic, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was built upon th ...

. The agreement involved promises of Italian territorial expansion against Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe#Before World War I, Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military ...

, the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

and in Africa where it was promised enlargement of its colonies. The Entente countries hoped to force the Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,; ; , ; were one of the two main coalitions that fought in World War I (1914–1918). It consisted of the German Empire, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Bulga ...

– particularly Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

and Austria-Hungary – to divert some of their forces away from existing battlefields. The Entente also hoped that Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to ...

and Bulgaria

Bulgaria, officially the Republic of Bulgaria, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern portion of the Balkans directly south of the Danube river and west of the Black Sea. Bulgaria is bordered by Greece and Turkey t ...

would be encouraged to join them after Italy did the same.

In May 1915, Italy declared war on Austria-Hungary but waited a year before declaring war on Germany, leading France and the UK to resent the delay. At the Paris Peace Conference after the war, the United States of America

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 contiguo ...

applied pressure to void the treaty as contrary to the principle of self-determination

Self-determination refers to a people's right to form its own political entity, and internal self-determination is the right to representative government with full suffrage.

Self-determination is a cardinal principle in modern international la ...

. A new agreement produced at the conference reduced the territorial gains promised by the treaty: Italy received Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol

Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol ( ; ; ), often known in English as Trentino-South Tyrol or by its shorter Italian name Trentino-Alto Adige, is an Regions of Italy#Autonomous regions with special statute, autonomous region of Italy, located in the ...

and the Julian March in addition to the occupation of the city of Vlorë

Vlorë ( ; ; sq-definite, Vlora) is the List of cities and towns in Albania, third most populous city of Albania and seat of Vlorë County and Vlorë Municipality. Located in southwestern Albania, Vlorë sprawls on the Bay of Vlorë and is surr ...

and the Dodecanese Islands. Italy was compelled to settle its eastern border with the new Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes through the bilateral Treaty of Rapallo. Italy thus received Istria

Istria ( ; Croatian language, Croatian and Slovene language, Slovene: ; Italian language, Italian and Venetian language, Venetian: ; ; Istro-Romanian language, Istro-Romanian: ; ; ) is the largest peninsula within the Adriatic Sea. Located at th ...

and the city of Zadar

Zadar ( , ), historically known as Zara (from Venetian and Italian, ; see also other names), is the oldest continuously inhabited city in Croatia. It is situated on the Adriatic Sea, at the northwestern part of Ravni Kotari region. Zadar ...

as an enclave in Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; ; ) is a historical region located in modern-day Croatia and Montenegro, on the eastern shore of the Adriatic Sea. Through time it formed part of several historical states, most notably the Roman Empire, the Kingdom of Croatia (925 ...

, along with several islands along the eastern Adriatic Sea

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkans, Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Se ...

shore. The Entente went back on its promises to provide Italy with expanded colonies and a part of Asia Minor

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

.

The results of the Paris Peace Conference transformed wartime national fervour in Italy into nationalistic resentment championed by Gabriele D'Annunzio by declaring that the outcome of Italy's war was a mutilated victory

Mutilated victory () is a term coined by Gabriele D'Annunzio at the end of World War I, used by a part of Italian nationalists to denounce the partial infringement (and request the full application) of the 1915 pact of London concerning territori ...

. He led a successful march of veterans and disgruntled soldiers to capture the port of Rijeka

Rijeka (;

Fiume ( �fjuːme in Italian and in Fiuman dialect, Fiuman Venetian) is the principal seaport and the List of cities and towns in Croatia, third-largest city in Croatia. It is located in Primorje-Gorski Kotar County on Kvarner Ba ...

, which was claimed by Italy and denied by the Entente powers. The move became known as the '' Impresa di Fiume'', and D'Annunzio proclaimed the short-lived Italian Regency of Carnaro

The Italian Regency of Carnaro () was a self-proclaimed state in the city of Fiume (now Rijeka, Croatia) led by Gabriele d'Annunzio between 1919 and 1920.

During World War I (1914–1918), which the Kingdom of Italy entered on the side of t ...

in the city before being forced out by the Italian military so that the Free State of Fiume

The Free State of Fiume () was an independent free state that existed from 1920 to 1924. Its territory of comprised the city of Fiume (today Rijeka, Croatia) and rural areas to its north, with a corridor to its west connecting it to the Kingdo ...

could be established instead. The Regency of Carnaro was significant in the development of Italian fascism

Italian fascism (), also called classical fascism and Fascism, is the original fascist ideology, which Giovanni Gentile and Benito Mussolini developed in Italy. The ideology of Italian fascism is associated with a series of political parties le ...

.

Background

Soon after the outbreak ofWorld War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, the Triple Entente

The Triple Entente (from French meaning "friendship, understanding, agreement") describes the informal understanding between the Russian Empire, the French Third Republic, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was built upon th ...

powers – the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

, France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

, and Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

– sought to attract more allies to their side. The first attempt to bring in Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

(a part of the Triple Alliance) as an ally of the Entente was in August–September 1914. The matter became closely related to contemporary efforts to obtain an alliance with Bulgaria, or at least secure its neutrality, in return for territorial gains against Entente-allied Serbia

, image_flag = Flag of Serbia.svg

, national_motto =

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Serbia.svg

, national_anthem = ()

, image_map =

, map_caption = Location of Serbia (gree ...

. As compensation, Serbia was promised territories which were parts of Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe#Before World War I, Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military ...

at the time, specifically Bosnia and Herzegovina

Bosnia and Herzegovina, sometimes known as Bosnia-Herzegovina and informally as Bosnia, is a country in Southeast Europe. Situated on the Balkans, Balkan Peninsula, it borders Serbia to the east, Montenegro to the southeast, and Croatia to th ...

and an outlet to the Adriatic Sea

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkans, Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Se ...

in Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; ; ) is a historical region located in modern-day Croatia and Montenegro, on the eastern shore of the Adriatic Sea. Through time it formed part of several historical states, most notably the Roman Empire, the Kingdom of Croatia (925 ...

.

Negotiations

First offers

Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol

Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol ( ; ; ), often known in English as Trentino-South Tyrol or by its shorter Italian name Trentino-Alto Adige, is an Regions of Italy#Autonomous regions with special statute, autonomous region of Italy, located in the ...

, Vlorë

Vlorë ( ; ; sq-definite, Vlora) is the List of cities and towns in Albania, third most populous city of Albania and seat of Vlorë County and Vlorë Municipality. Located in southwestern Albania, Vlorë sprawls on the Bay of Vlorë and is surr ...

, and a dominant position in the Adriatic. Believing that such a move by Italy would prompt Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to ...

to join the Entente as well against Austria-Hungary, Russian foreign minister Sergey Sazonov pursued the matter. British Foreign Minister Edward Grey supported the idea; he said that Trieste

Trieste ( , ; ) is a city and seaport in northeastern Italy. It is the capital and largest city of the Regions of Italy#Autonomous regions with special statute, autonomous region of Friuli-Venezia Giulia, as well as of the Province of Trieste, ...

should be added to the claim as potentially important to win over Italian public opinion on joining the war.

The Italian ambassador to the United Kingdom, Guglielmo Imperiali, presented Grey with Italy's conditions, but Grey did not consider the talks could produce any practical results. He told Imperiali that Britain would not consider the matter any further until Italy committed itself to joining the Entente. On Grey's instructions, Rennell Rodd, British ambassador to Italy, asked Italian Prime Minister Antonio Salandra

Antonio Salandra (; 13 August 1853 – 9 December 1931) was a conservative Italian politician, journalist, and writer who served as the 21st prime minister of Italy between 1914 and 1916. He ensured the entry of Italy in World War I on the side o ...

if Italy could enter the war. Salandra informed Rodd that this was impossible at the time and that any premature attempt to abandon neutrality would jeopardise any prospect of a future alliance. Sazonov was informed accordingly, and Russia abandoned the matter.

The motives for the Entente's overture to Italy and Italian consideration of entering the war were entirely opportunistic. The Entente saw Germany as the principal enemy and wanted to force it to divert some of its forces away from the existing battlefields. Italy had basically different interests from the Entente powers. It saw opportunities to fulfil Italian irredentist objectives in Austria-Hungary, to gain a dominant position in the Adriatic basin and to expand its colonial empire. Initially, the majority of the Italian public favoured neutrality, but groups favouring an expansionist war against Austria-Hungary formed in every part of the political spectrum. The most ardent supporters of war became irredentist groups such as ''Trento e Trieste'' (Trento

Trento ( or ; Ladin language, Ladin and ; ; ; ; ; ), also known in English as Trent, is a city on the Adige, Adige River in Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol in Italy. It is the capital of the Trentino, autonomous province of Trento. In the 16th ...

and Trieste) led by Giovanni Giuriati or Alfredo Rocco

Alfredo Rocco (9 September 1875 – 28 August 1935) was an Italian politician and jurist. He was Professor of Commercial Law at the University of Urbino (1899–1902) and in Macerata (1902–1905), then Professor of Civil Procedure in Parma, of ...

who saw the war as an opportunity for ethnic struggle against neighbouring South Slavic populations.

Occupation of Vlorë

Salandra and his foreign minister Antonino Paternò Castello did not break off the negotiations completely. They used the subsequent months to wait for a chance to increase Italian demands to the maximum at an opportune time. There was an attempt to relaunch the negotiations in London on 16 September when Castello told Rodd that the British and Italians shared interests in preventing westward spread of Slavic domains under Russian influence, specifically by preventing Slavic influence in the Adriatic, where irredentists claimed Dalmatia. While Castello instructed Imperiali to tell the British that Italy would not decide to abandon its neutrality before the Entente accepted their conditions, Grey insisted on Italy first committing to joining the Entente and the talks collapsed again. Particular opposition to the Italian claim against Dalmatia came from thePermanent Under-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs

This is a list of Permanent Under-Secretary of State, Permanent Under-Secretaries in the British Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (and its predecessors) since 1790.

Not to be confused with Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State f ...

Arthur Nicolson who remarked that Sazonov was right to claim that Dalmatia wished to unite with Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia

The Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia (; or ; ) was a nominally autonomous kingdom and constitutionally defined separate political nation within the Austro-Hungarian Empire. It was created in 1868 by merging the kingdoms of Kingdom of Croatia (Habs ...

. He added that if Dalmatia were annexed by Italy, it would inherit a problem from Austria-Hungary, that of having a large South Slavic population looking for greater independence.

Nonetheless, Castello managed to obtain British endorsement for Italian occupation of Vlorë. The move was made as a preparation for Italian intervention and designed to lend some prestige to the Italian government. Expecting opposition from Sazonov, Castello asked Grey to get the Russians to let him have this without making any concessions in return as a necessary evil to attract Italy to join the Entente.

Sonnino replaces Castello

In late October, there was an attempt to get Italy to intervene against an expected Turkish attack against the

In late October, there was an attempt to get Italy to intervene against an expected Turkish attack against the Suez Canal

The Suez Canal (; , ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, Indo-Mediterranean, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia (and by extension, the Sinai Peninsula from the rest ...

. Sazonov warned Grey not to offer Dalmatia in exchange and the latter replied that no such offer was made as the canal remaining open was in Italian interests too.

The matter of an Italian alliance was taken up by Castello's successor Sidney Sonnino

Sidney Costantino, Baron Sonnino (; 11 March 1847 – 24 November 1922) was an Italian statesman, 19th prime minister of Italy and twice served briefly as one, in 1906 and again from 1909 to 1910. In 1901, he founded a new major newspaper, '' Il ...

and Rodd in November. Sonnino proposed a non-binding agreement which could be turned into a binding one at an opportune time. Even though similar proposals by his predecessor were turned down, Rodd was informed through his contacts in the Italian government that the Italian Armed Forces

The Italian Armed Forces (, ) encompass the Italian Army, the Italian Navy and the Italian Air Force. A fourth Military branch, branch of the armed forces, known as the Carabinieri, take on the role as the nation's Gendarmerie, military police an ...

were prepared to intervene by February 1915, prompting Rodd to urge Grey to consider the proposal. However, Grey declined the idea as a hypothetical bargain as he appeared indifferent to an Italian alliance at this point.

Following this, Salandra and Sonnino conducted negotiations with the Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,; ; , ; were one of the two main coalitions that fought in World War I (1914–1918). It consisted of the German Empire, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Bulga ...

in an apparent attempt to keep the Central Powers at bay until further negotiations were possible with the Entente. These talks collapsed on 15 February 1915. The following day, Sonnino sent Imperiali a specific list of conditions set out in sixteen points necessary for Italy to enter the war.

Seeking Bulgarian alliance

While the Entente Powers were negotiating with Italy, they led a concurrent diplomatic effort aimed at obtaining Bulgarian alliance (or at least friendly neutrality). This situation led to a conflict of territorial claims staked by Italy and Serbia. Namely, awarding Italy Dalmatia would largely block the Adriatic outlet offered to Serbia (in addition to Bosnia and Herzegovina) as compensation to Serbia's cession of much ofVardar Macedonia

Vardar Macedonia (Macedonian language, Macedonian and ) is a historical term referring to the central part of the broader Macedonian region, roughly corresponding to present-day North Macedonia. The name derives from the Vardar, Vardar River and i ...

to Bulgaria requested by the Entente as enticement to Bulgaria. Sazonov wanted to strengthen his offer to Serbia and indirectly to Bulgaria by guaranteeing such an outlet to Serbia, but Grey blocked the initiative, arguing that an Italian alliance was more important.

In mid-February, following the start of the Gallipoli campaign, the British were convinced that Bulgaria would enter the war on the side of the Entente within weeks, certain of its victory. Even though it worked to bring Bulgaria on board, Russia was anxious that Bulgarian and Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

forces might occupy Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

to push Russia out of the region despite being promised control of the city by the Entente. Sonnino saw the combined Bulgarian and Greek entry into the war likely to assure Entente victory in the Balkans. On 4 March, Imperiali informed Grey that Italy would enter the war and presented him with the 16 conditions insisting on curtailing Slavic westward advance.

Russian claim over Constantinople

Grey noted that the Italian claims were excessive, but also that they did not conflict with British interests. He also thought that recent Russian stubborn objections against Greek attack to capture Constantinople could be overcome by addition of Italian troops, and that Italian participation in the war would expedite a decision from Bulgaria and Romania, still waiting to commit to the war.

Sazonov objected to any Italian role regarding Constantinople, seeing it as a threat to Russian control of the city promised by the allies in return for Russian losses in the war. This led Grey to obtain formal recognition of the Russian claim to the city by the Committee of Imperial Defence and by France, leading Sazonov to acquiesce to an agreement with Italy, except he would not consent to Italy taking the Adriatic coast south of the city of

Grey noted that the Italian claims were excessive, but also that they did not conflict with British interests. He also thought that recent Russian stubborn objections against Greek attack to capture Constantinople could be overcome by addition of Italian troops, and that Italian participation in the war would expedite a decision from Bulgaria and Romania, still waiting to commit to the war.

Sazonov objected to any Italian role regarding Constantinople, seeing it as a threat to Russian control of the city promised by the allies in return for Russian losses in the war. This led Grey to obtain formal recognition of the Russian claim to the city by the Committee of Imperial Defence and by France, leading Sazonov to acquiesce to an agreement with Italy, except he would not consent to Italy taking the Adriatic coast south of the city of Split

Split(s) or The Split may refer to:

Places

* Split, Croatia, the largest coastal city in Croatia

* Split Island, Canada, an island in the Hudson Bay

* Split Island, Falkland Islands

* Split Island, Fiji, better known as Hạfliua

Arts, enter ...

and as long as the Italian troops did not participate in the capture of the Turkish Straits

The Turkish Straits () are two internationally significant waterways in northwestern Turkey. The Straits create a series of international passages that connect the Aegean and Mediterranean seas to the Black Sea. They consist of the Dardanelles ...

.

The request concerning the Turkish Straits was found acceptable by Grey since the British never anticipated Italy would take part in the campaign against Constantinople. The bulk of the Italian claim, concerning acquisition of Trentino, Trieste, and Istria

Istria ( ; Croatian language, Croatian and Slovene language, Slovene: ; Italian language, Italian and Venetian language, Venetian: ; ; Istro-Romanian language, Istro-Romanian: ; ; ) is the largest peninsula within the Adriatic Sea. Located at th ...

was likely to attract protests against handing predominantly Slav-populated territories to Italy from Frano Supilo

Frano Supilo (30 November 1870 – 25 September 1917) was a Croatian politician and journalist. He opposed the Austro-Hungarian domination of Europe prior to World War I. He participated in the debates leading to the formation of Yugoslavia as ...

– a dominant figure in the nascent Yugoslav Committee advocating interests of South Slavs living in Austria-Hungary. On the other hand, the Serbian Prime Minister Nikola Pašić

Nikola Pašić ( sr-Cyrl, Никола Пашић, ; 18 December 1845 – 10 December 1926) was a Serbian and Yugoslav politician and diplomat. During his political career, which spanned almost five decades, he served five times as prime minis ...

and Sazonov found it acceptable. Even though Serbian Niš Declaration of war objectives called for the struggle to liberate and unify "unliberated brothers", referring to "three tribes of one people" meaning the Serbs, the Croats

The Croats (; , ) are a South Slavs, South Slavic ethnic group native to Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and other neighboring countries in Central Europe, Central and Southeastern Europe who share a common Croatian Cultural heritage, ancest ...

, and the Slovenes

The Slovenes, also known as Slovenians ( ), are a South Slavs, South Slavic ethnic group native to Slovenia and adjacent regions in Italy, Austria and Hungary. Slovenes share a common ancestry, Slovenian culture, culture, and History of Slove ...

, as means to attract support from South Slavs living in Austria-Hungary, Pašić was primarily concerned with achieving a Greater Serbia

The term Greater Serbia or Great Serbia () describes the Serbian nationalist and irredentist ideology of the creation of a Serb state which would incorporate all regions of traditional significance to Serbs, a South Slavic ethnic group, inclu ...

. Sazonov acquiesced, adding that he has nothing to say on behalf of the Croats and the Slovenes and would not approve Russian forces to fight "half a day" for liberty of the Slovenes.

Final six weeks of talks

Nonetheless, negotiations extended for six weeks over disagreements as the extent of Italian territorial gains in Dalmatia was still objected to by Sazonov. The Italian claim of Dalmatia to theNeretva

The Neretva (, sr-Cyrl, Неретва), also known as Narenta, is one of the largest rivers of the eastern part of the Adriatic basin. Four Hydroelectricity, hydroelectric power plants with Dam, large dams (higher than 15 metres) provide flood ...

River, including the Pelješac

Pelješac (; Chakavian: ; ) is a peninsula in southern Dalmatia in Croatia. The peninsula is part of the Dubrovnik-Neretva County and is the second largest peninsula in Croatia. From the isthmus that begins at Ston, to the top of Cape Loviš ...

Peninsula and all Adriatic islands was not based on self-determination

Self-determination refers to a people's right to form its own political entity, and internal self-determination is the right to representative government with full suffrage.

Self-determination is a cardinal principle in modern international la ...

, but on security concerns in a future war, as the Italian negotiators alleged that Russia might occupy the Austrian-controlled coast while Italy had no defensible port on the western shore of the Adriatic. The Committee of Imperial Defence was concerned about rising Russian naval power in the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern ...

and it is possible, although there is no direct evidence, that this influenced the British support for the Italian claims in the Adriatic, as means to deny it to Russia.

Hoping to achieve the diplomatic breakthrough in securing alliances with Bulgaria, Romania, and Greece, Grey turned Sonnino's 16 points into a draft agreement and forwarded it to Russia against protests by the Yugoslav Committee. Sazonov objected to the draft agreement and dismissed an Italian offer of Dubrovnik

Dubrovnik, historically known as Ragusa, is a city in southern Dalmatia, Croatia, by the Adriatic Sea. It is one of the most prominent tourist destinations in the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean, a Port, seaport and the centre of the Dubrovni ...

as a port for South Slavs as it lacked inland transport routes. Sazonov demanded Split in addition as a better port and objected to the requested demilitarisation of the coast belonging to the Kingdom of Montenegro

The Kingdom of Montenegro was a monarchy in southeastern Europe, present-day Montenegro, during the tumultuous period of time on the Balkan Peninsula leading up to and during World War I. Officially it was a constitutional monarchy, but absolu ...

. Grey drew up a document taking into consideration the Russian objections and forwarded it to Imperiali, but Sonnino threatened to end the negotiations over the differences.

The deadlock was broken by French Foreign Minister Théophile Delcassé

Théophile Delcassé (; 1 March 185222 February 1923) was a French politician who served as foreign minister from 1898 to 1905. He is best known for his hatred of German Empire, Germany and efforts to secure alliances with Russian Empire, Russ ...

who was ready to pay any price to obtain an alliance with Italy believing it would bring about alliances with Bulgaria, Greece, and Romania as well. Delcassé proposed a reduction in the Italian claim in Dalmatia to favour Serbia in exchange for unrestricted possession of the Dodecanese

The Dodecanese (, ; , ''Dodekánisa'' , ) are a group of 15 larger and 150 smaller Greek islands in the southeastern Aegean Sea and Eastern Mediterranean, off the coast of Anatolia, of which 26 are inhabited. This island group generally define ...

Islands. The initiative succeeded because the Russian Imperial Army

The Imperial Russian Army () was the army of the Russian Empire, active from 1721 until the Russian Revolution of 1917. It was organized into a standing army and a state militia. The standing army consisted of Regular army, regular troops and ...

lost initiative in the Carpathians

The Carpathian Mountains or Carpathians () are a range of mountains forming an arc across Central Europe and Southeast Europe. Roughly long, it is the third-longest European mountain range after the Urals at and the Scandinavian Mountains ...

and its commander in chief, Grand Duke Nicholas, informed Sazonov that Italian and Romanian support would be needed urgently to regain the initiative. In response, Sazonov accepted the proposal put forward by Delcassé, insisting that Italy enter the war by the end of April and leaving all treaty-related demilitarisation matters to the British Prime Minister H. H. Asquith

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith (12 September 1852 – 15 February 1928) was a British statesman and Liberal Party (UK), Liberal politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1908 to 1916. He was the last ...

to decide. Asquith produced a draft agreement on 9 April and it was accepted by Sonnino with minor amendments five days later. The agreement was signed on 26 April by Grey and ambassadors Paul Cambon, Imperiali, and Alexander von Benckendorff, behalf of the United Kingdom, France, Italy, and Russia.

Terms

Article 1 of the treaty determined that a military agreement shall be concluded to guarantee the number of troops committed by Russia against Austria-Hungary to prevent it from concentrating all its forces against Italy. Article 2 required Italy to enter the war against all enemies of the United Kingdom, Russia, and France, and Article 3 obliged the French and British navies from supporting the Italian war effort by destroying Austro-Hungarian fleet.

Article 4 of the treaty determined that Italy shall receive Trentino, and the

Article 1 of the treaty determined that a military agreement shall be concluded to guarantee the number of troops committed by Russia against Austria-Hungary to prevent it from concentrating all its forces against Italy. Article 2 required Italy to enter the war against all enemies of the United Kingdom, Russia, and France, and Article 3 obliged the French and British navies from supporting the Italian war effort by destroying Austro-Hungarian fleet.

Article 4 of the treaty determined that Italy shall receive Trentino, and the South Tyrol

South Tyrol ( , ; ; ), officially the Autonomous Province of Bolzano – South Tyrol, is an autonomous administrative division, autonomous provinces of Italy, province in northern Italy. Together with Trentino, South Tyrol forms the autonomo ...

by defining a new Italian–Austrian frontier line between the Piz Umbrail and Toblach, and a new eastern Italian frontier running from Tarvisio in the north to the coast in the Kvarner Gulf leaving Rijeka

Rijeka (;

Fiume ( �fjuːme in Italian and in Fiuman dialect, Fiuman Venetian) is the principal seaport and the List of cities and towns in Croatia, third-largest city in Croatia. It is located in Primorje-Gorski Kotar County on Kvarner Ba ...

just outside the Italian territory.

Article 5 awarded Dalmatia to Italy – specifically the part north of a line running northeast from Cape Planka – including cities of Zadar

Zadar ( , ), historically known as Zara (from Venetian and Italian, ; see also other names), is the oldest continuously inhabited city in Croatia. It is situated on the Adriatic Sea, at the northwestern part of Ravni Kotari region. Zadar ...

and Šibenik

Šibenik (), historically known as Sebenico (), is a historic town in Croatia, located in central Dalmatia, where the river Krka (Croatia), Krka flows into the Adriatic Sea. Šibenik is one of the oldest Croatia, Croatian self-governing cities ...

, as well as the basin of the Krka River and its tributaries in the Italian territory. The article also awarded Italy all Austro-Hungarian Adriatic islands except Brač

Brač is a Croatian island in the Adriatic Sea, with an area of ,

making it the largest island in Dalmatia, and the third largest in the Adriatic. It is separated from the mainland by the Brač Channel, which is wide.Šolta

Šolta (; ; ) is an island in Croatia. It is situated in the Adriatic Sea in the central Dalmatian archipelago.

Geography

Šolta is located west of the island of Brač, south of Split (city), Split (separated by Split Channel) and east of the D ...

, Čiovo

Čiovo (pronounced ) is an island located off the Adriatic coast in Croatia with an area of (length , width up to ),

population of 5,908 inhabitants (2011). Its highest peak is the 218 m Rudine.

The centre of the island has geographical coord ...

, Drvenik Mali, Drvenik Veli

Drvenik Veli is a Croatian island in the Adriatic Sea. It is situated in the middle of the Dalmatian archipelago, northwest of Šolta, from the mainland.

, Krk

Krk (; ; ; ; archaic German: ''Vegl'', ; ) is a Croatian island in the northern Adriatic Sea, located near Rijeka in the Bay of Kvarner and part of Primorje-Gorski Kotar county. Krk is tied with Cres as the largest Adriatic island, depending o ...

, Rab, Prvić, Sveti Grgur

Sveti Grgur (; lit. ''Saint Gregory'') is an uninhabited island in Croatia, on the Adriatic Sea between Rab and Krk. The island was the site of a women's prison in SFR Yugoslavia

The Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (commonly abbrevia ...

, Goli Otok, Jakljan, and Koločep

Koločep (; locally known as Kalamota () from ) is one of the three inhabited Elaphiti Islands situated near the city of Dubrovnik with an area of . Koločep is the southernmost inhabited island in Croatia. According to the 2021 census, its popul ...

. The article specified that the remaining coast between Rijeka and the Drin River

The Drin (; or ; ) is a river in Southeastern Europe with two major tributaries – the White Drin and the Black Drin and two distributary, distributaries – one discharging into the Adriatic Sea, in the Gulf of Drin and the other into the ...

is awarded to Croatia, Serbia, and Montenegro.

Furthermore, Article 5 required demilitarisation of the coast between the Cape Planka and the Aoös

The Vjosa (; indefinite form: ) or Aoös () is a river in northwestern Greece and southwestern Albania. Its total length is about , of which the first are in Greece, and the remaining in Albania. Its drainage basin is and its average dischar ...

River with exception of the strip between Pelješac and a point southeast of Dubrovnik and in Montenegrin territory where military bases were allowed through prewar arrangements. The demilitarisation was meant to assure Italy of military dominance in the region. The coast between the point 10 kilometres southeast of Dubrovnik and the Drin River was to be divided between Serbia and Montenegro. Articles 4 and 5 thus added to Italy's population 200,000 speakers of German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany, the country of the Germans and German things

**Germania (Roman era)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizenship in Germany, see also Ge ...

, and 600,000 South Slavs.

Articles 6 and 7 gave Italy full sovereignty over Vlorë, the Sazan Island, and surrounding territory necessary for defence, requiring it to leave a strip of land west of the Lake Ohrid

Lake Ohrid is a lake which straddles the mountainous border between the southwestern part of North Macedonia and eastern Albania. It is one of Europe's deepest and oldest lakes, with a unique aquatic ecosystem of worldwide importance, with more th ...

to allow a border between Serbia and Greece. Italy was to represent Albania

Albania ( ; or ), officially the Republic of Albania (), is a country in Southeast Europe. It is located in the Balkans, on the Adriatic Sea, Adriatic and Ionian Seas within the Mediterranean Sea, and shares land borders with Montenegro to ...

in foreign relations, but it was also required to acquiesce to its partition between Serbia, Montenegro, and Greece if the United Kingdom, France, and Russia decided so. Article 8 gave Italy full sovereignty over the Dodecanese Islands.

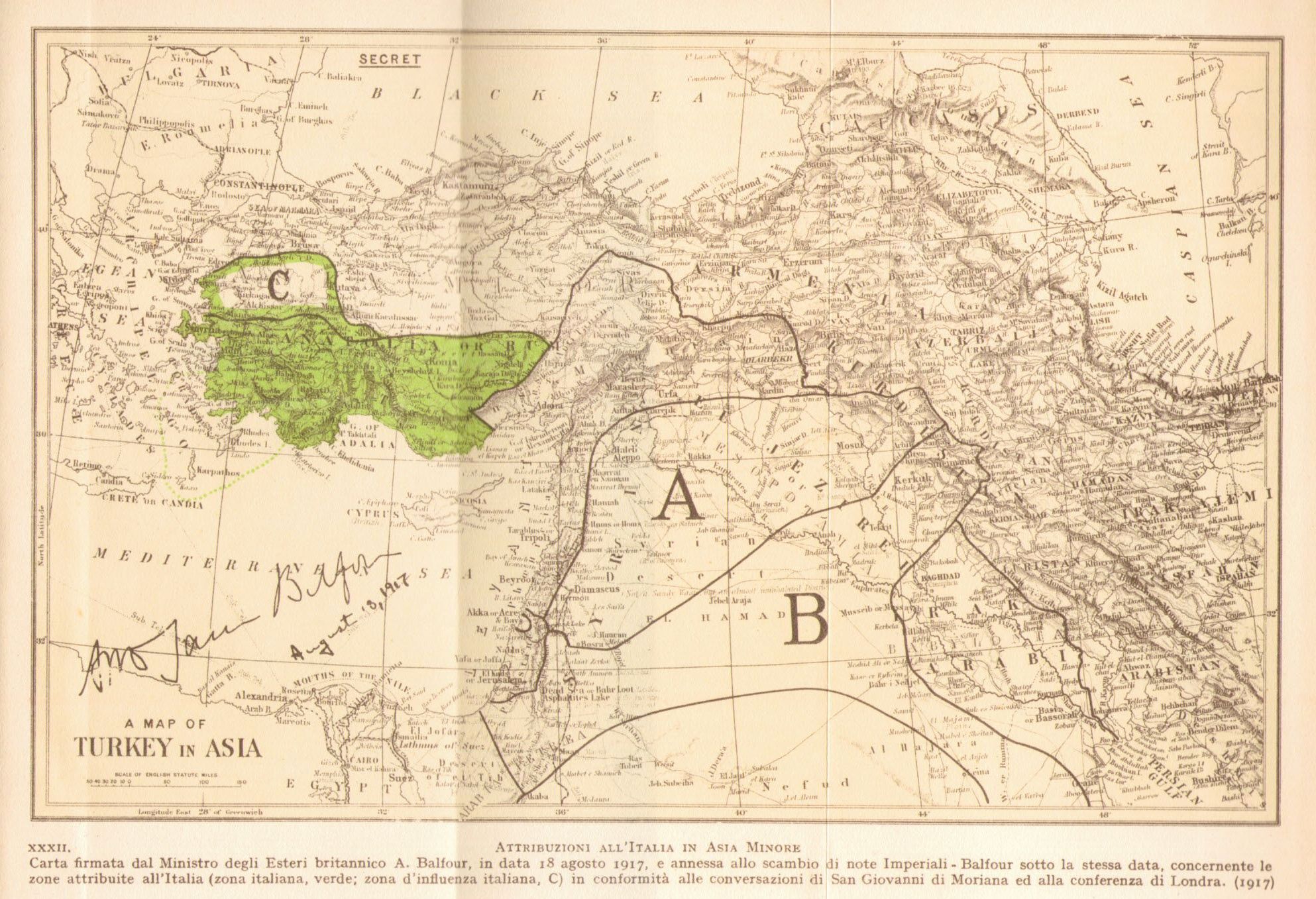

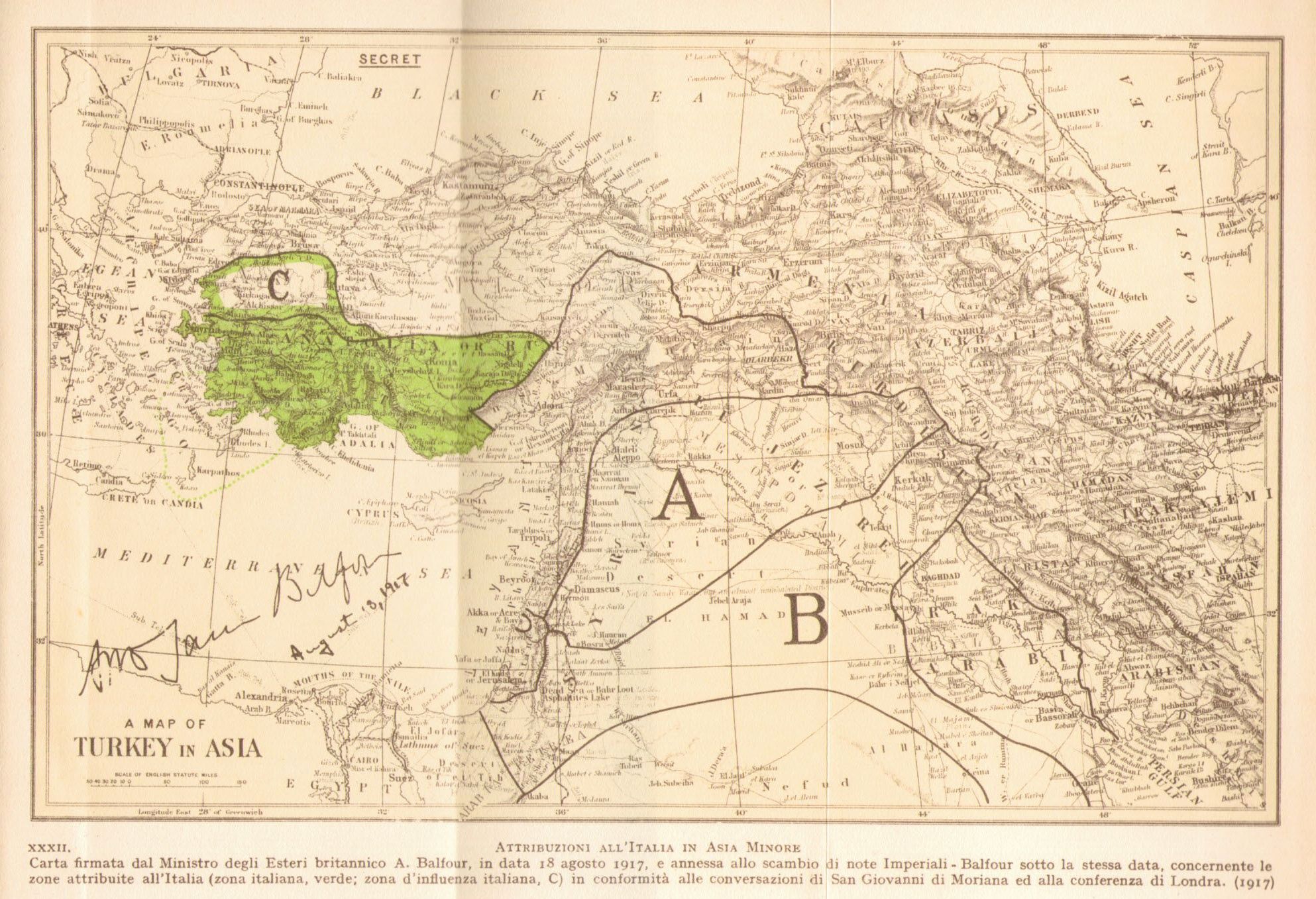

Provisions detailing territorial gains beyond Europe were comparably vaguely written. Article 9 promised Italy territory in the area of Antalya

Antalya is the fifth-most populous city in Turkey and the capital of Antalya Province. Recognized as the "capital of tourism" in Turkey and a pivotal part of the Turkish Riviera, Antalya sits on Anatolia's southwest coast, flanked by the Tau ...

in a potential Partition of the Ottoman Empire

The partition of the Ottoman Empire (30 October 19181 November 1922) was a geopolitical event that occurred after World War I and the occupation of Constantinople by British, French, and Italian troops in November 1918. The partitioning was ...

, while Article 10 gave it rights belonging to the Sultan

Sultan (; ', ) is a position with several historical meanings. Originally, it was an Arabic abstract noun meaning "strength", "authority", "rulership", derived from the verbal noun ', meaning "authority" or "power". Later, it came to be use ...

in Libya

Libya, officially the State of Libya, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to Egypt–Libya border, the east, Sudan to Libya–Sudan border, the southeast, Chad to Chad–L ...

under the Treaty of Ouchy. Article 13 promised Italy compensation if the French or British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and culture ...

colonial empires made territorial gains against the German colonial empire

The German colonial empire () constituted the overseas colonies, dependencies, and territories of the German Empire. Unified in 1871, the chancellor of this time period was Otto von Bismarck. Short-lived attempts at colonization by Kleinstaat ...

in Africa. In Article 12, Italy upheld the Entente powers in support of future control of Mecca

Mecca, officially Makkah al-Mukarramah, is the capital of Mecca Province in the Hejaz region of western Saudi Arabia; it is the Holiest sites in Islam, holiest city in Islam. It is inland from Jeddah on the Red Sea, in a narrow valley above ...

and Medina

Medina, officially al-Madinah al-Munawwarah (, ), also known as Taybah () and known in pre-Islamic times as Yathrib (), is the capital of Medina Province (Saudi Arabia), Medina Province in the Hejaz region of western Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, ...

by an independent Muslim state.

Articles 11 and 14 promised a share in any war indemnity and a loan to Italy in the amount of 50 million pounds sterling

Sterling (Currency symbol, symbol: Pound sign, £; ISO 4217, currency code: GBP) is the currency of the United Kingdom and nine of its associated territories. The pound is the main unit of account, unit of sterling, and the word ''Pound (cu ...

respectively. Article 15 promised Entente support to Italian opposition to inclusion of the Holy See

The Holy See (, ; ), also called the See of Rome, the Petrine See or the Apostolic See, is the central governing body of the Catholic Church and Vatican City. It encompasses the office of the pope as the Bishops in the Catholic Church, bishop ...

in any settlement of questions raised by the war, and Article 16 stipulated that the treaty was to be kept secret.

Aftermath

Response

Even though the treaty was meant to be secret, an outline of its provisions became known to the Yugoslav Committee and its supporters in London in late April 1915. Serbia and the Yugoslav Committee protested it in strong terms in Entente capitals. Pašić condemned the disregard for the self-determination principle on which the Niš Declaration rested and the lack of consultations with Serbia. He demanded the Entente refrain from treaties with Hungary or Romania on borders of interest to Croatia without conferring with Serbia first, as well as requesting assurances of future political union of the Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes. Pašić telegraphed his proposal to Grey from the provisional wartime capital of

Even though the treaty was meant to be secret, an outline of its provisions became known to the Yugoslav Committee and its supporters in London in late April 1915. Serbia and the Yugoslav Committee protested it in strong terms in Entente capitals. Pašić condemned the disregard for the self-determination principle on which the Niš Declaration rested and the lack of consultations with Serbia. He demanded the Entente refrain from treaties with Hungary or Romania on borders of interest to Croatia without conferring with Serbia first, as well as requesting assurances of future political union of the Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes. Pašić telegraphed his proposal to Grey from the provisional wartime capital of Niš

Niš (; sr-Cyrl, Ниш, ; names of European cities in different languages (M–P)#N, names in other languages), less often spelled in English as Nish, is the list of cities in Serbia, third largest city in Serbia and the administrative cente ...

through British ambassador Charles Louis des Graz. However, Grey declined both requests. The Yugoslav Committee president Ante Trumbić

Ante Trumbić (17 May 1864 – 17 November 1938) was a Yugoslav and Croatian lawyer and politician in the early 20th century.

Biography

Trumbić was born in Split in the Austrian crownland of Dalmatia and studied law at Zagreb, Vienna and G ...

met with Lord Crewe, a senior member of the British Cabinet, demanding support for unification of Croatia, Istria, and Dalmatia and then for a political union with Serbia. News of the treaty also compelled the Yugoslav Committee to adopt a less critical view of Serbian demands concerning the method of political unification of the South Slavs as it became clear that the unity of the Croats and the unity of the Slovenes would depend on success of Serbia. Full text of the treaty text was published by the Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

after the October Revolution

The October Revolution, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (in Historiography in the Soviet Union, Soviet historiography), October coup, Bolshevik coup, or Bolshevik revolution, was the second of Russian Revolution, two r ...

. In 1917, Pašić and Trumbić negotiated and agreed upon the Corfu Declaration setting out a plan for post-war unification of South Slavs to counter the Italian territorial claims outlined in the Treaty of London.

Grey's policy and the treaty were criticised in British press. An early example of such critique was "The National Union of South Slavs and the Adriatic Question" written by Arthur Evans

Sir Arthur John Evans (8 July 1851 – 11 July 1941) was a British archaeologist and pioneer in the study of Aegean civilization in the Bronze Age.

The first excavations at the Minoan palace of Knossos on the List of islands of Greece, Gree ...

and published in April 1915. Evans described the treaty as a manifestation of Italian chauvinistic ambitions against Dalmatia causing a crisis. Evans expanded on his criticism in article "Italy and Dalmatia" published by ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British Newspaper#Daily, daily Newspaper#National, national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its modern name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its si ...

'' on 27 April. Evans was joined by historians Robert Seton-Watson and Wickham Steed

Henry Wickham Steed (10 October 1871 – 13 January 1956) was an English journalist and historian. He was editor of ''The Times'' from 1919 to 1922.

Early life

Born in Long Melford, England, Steed was educated at Sudbury Grammar School ...

by describing the Italian claims as absurd and Grey's policies as unjust. Grey responded by reiterating that in the event of victory in the war, Serbia would receive territories from Austria-Hungary allowing its enlargement.

Further course of the war

In the final weeks before entering the war, internal struggle took place in Italy. National fervour was whipped up by speeches of Gabriele D'Annunzio, who called for war as a measure of national worth and inciting violence against neutralists and the former Prime Minister

In the final weeks before entering the war, internal struggle took place in Italy. National fervour was whipped up by speeches of Gabriele D'Annunzio, who called for war as a measure of national worth and inciting violence against neutralists and the former Prime Minister Giovanni Giolitti

Giovanni Giolitti (; 27 October 1842 – 17 July 1928) was an Italian statesman. He was the prime minister of Italy five times between 1892 and 1921. He is the longest-serving democratically elected prime minister in Italian history, and the sec ...

who favoured neutrality. This period became known as the ''radiant days''.

On 22 May 1915, the Italian government decided to launch the Alpine Front by declaring war against Austria-Hungary alone. This ignored the requirement set out in Article 2 to wage war against all the Central Powers. France accused Italy of violating the Treaty of London, and Russia speculated on the potential existence of a non-aggression agreement between Italy and Germany. Lack of preparation of the army was cited as the decision for the non-compliance with the treaty. Failure to declare war on other Central Powers, especially Germany, led to isolation of Italy among the Entente powers. Following pressure from the Entente and internal political struggle, war was declared on the Ottoman Empire on 20 August. Italy did not declare war on Germany until 27 August 1916. Italy was nearly militarily defeated by the Central Powers in 1917, at the Battle of Caporetto

The Battle of Kobarid (also known as the Twelfth Battle of the Isonzo, the Battle of Caporetto or the Battle of Karfreit) took place on the Italian front of World War I.

The battle was fought between the Kingdom of Italy and the Central P ...

. Following a major retreat, the Italian forces managed to recover and mount a comeback a year later in the Battle of Vittorio Veneto at the cost of 600,000 dead, social unrest in the country and a badly damaged economy. Under the provisions of the Armistice of Villa Giusti

The Armistice of Villa Giusti or Padua Armistice was an armistice convention with Austria-Hungary which de facto ended warfare between Allies and Associated Powers and Austria-Hungary during World War I. Italy represented the Allies and Associat ...

, Italy was allowed to occupy Austro-Hungarian territory promised to her under the Treaty of London – parts of which were also claimed by the diplomatically unrecognised State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs

The State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs ( / ; ) was a political entity that was constituted in October 1918, at the end of World War I, by Slovenes, Croats and Serbs (Prečani (Serbs), Prečani) residing in what were the southernmost parts of th ...

. Italian troops began to move into those areas on 3 November 1918, entered Rijeka on 17 November and were stopped before Ljubljana

{{Infobox settlement

, name = Ljubljana

, official_name =

, settlement_type = Capital city

, image_skyline = {{multiple image

, border = infobox

, perrow = 1/2/2/1

, total_widt ...

by city-organised defence including a battalion of Serbian prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of war for a ...

.

The entry of Italy into the war did not entice Bulgaria to join the Entente as it became more cautious regarding further developments after early British and French setbacks at Gallipoli. Following the German capture of Kaunas

Kaunas (; ) is the second-largest city in Lithuania after Vilnius, the fourth largest List of cities in the Baltic states by population, city in the Baltic States and an important centre of Lithuanian economic, academic, and cultural life. Kaun ...

in Lithuania in late June during the Russian retreat, Bulgaria became convinced the Entente would lose the war. In August, the Entente powers sent a note to Pašić, promising territorial gains in exchange for territorial concessions in Vardar Macedonia to Bulgaria. The note promised Bosnia and Herzegovina, Syrmia

Syrmia (Ekavian sh-Latn-Cyrl, Srem, Срем, separator=" / " or Ijekavian sh-Latn-Cyrl, Srijem, Сријем, label=none, separator=" / ") is a region of the southern Pannonian Plain, which lies between the Danube and Sava rivers. It is div ...

, Bačka

Bačka ( sr-Cyrl, Бачка, ) or Bácska (), is a geographical and historical area within the Pannonian Plain bordered by the river Danube to the west and south, and by the river Tisza to the east. It is divided between Serbia and Hungary. ...

, the Adriatic Coast from Cape Planka to the point 10 kilometres southeast from Dubrovnik, Dalmatian islands not assigned to Italy, and Slavonia

Slavonia (; ) is, with Dalmatia, Croatia proper, and Istria County, Istria, one of the four Regions of Croatia, historical regions of Croatia. Located in the Pannonian Plain and taking up the east of the country, it roughly corresponds with f ...

if it was captured by the Entente militarily. On Sonnino's request, Pašić was not offered Central Croatia

In contemporary geography, the terms Central Croatia () and Mountainous Croatia () are used to describe most of the area sometimes historically known as Croatia or Croatia proper (), one of the four historical regions of the Republic of Cro ...

. Pašić agreed, offering to cede to Bulgaria a part of Vardar Macedonia largely along the lines agreed in 1912 at the end of the First Balkan War

The First Balkan War lasted from October 1912 to May 1913 and involved actions of the Balkan League (the Kingdoms of Kingdom of Bulgaria, Bulgaria, Kingdom of Serbia, Serbia, Kingdom of Greece, Greece and Kingdom of Montenegro, Montenegro) agai ...

but asked for further territorial gains by the addition of Central Croatia and Banat

Banat ( , ; ; ; ) is a geographical and Historical regions of Central Europe, historical region located in the Pannonian Basin that straddles Central Europe, Central and Eastern Europe. It is divided among three countries: the eastern part lie ...

. The Slovene Lands not promised to Italy appeared to be meant to remain in Austria-Hungary. On 6 October, Bulgaria joined the Central Powers and attacked Serbia five days later.

Agreement of Saint-Jean-de-Maurienne

Partition of the Ottoman Empire was discussed by the Entente powers at two conferences in London in January and February 1917, and inSaint-Jean-de-Maurienne

Saint-Jean-de-Maurienne (; or ''Sant-Jian-de-Môrièna''; ) is a Subprefectures in France, subprefecture of the Savoie Departments of France, department, in the regions of France, region of Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes (formerly Rhône-Alpes), in south ...

in April 1917. While it was apparent that the Italian interests were clashing with the British and the French, Italian representatives insisted on fulfilment of the promise given under the 1915 Treaty of London in the region of Antalya. To reinforce proportionality of Italian gains to those of their allies, the Italians added Konya

Konya is a major city in central Turkey, on the southwestern edge of the Central Anatolian Plateau, and is the capital of Konya Province. During antiquity and into Seljuk times it was known as Iconium. In 19th-century accounts of the city in En ...

and Adana

Adana is a large city in southern Turkey. The city is situated on the Seyhan River, inland from the northeastern shores of the Mediterranean Sea. It is the administrative seat of the Adana Province, Adana province, and has a population of 1 81 ...

vilayets to the claim. Most of the Italian demands were accepted in the Agreement of Saint-Jean-de-Maurienne. The French required that the Russia confirm the agreement though, which proved impossible following the Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of Political revolution (Trotskyism), political and social revolution, social change in Russian Empire, Russia, starting in 1917. This period saw Russia Dissolution of the Russian Empire, abolish its mona ...

.

Paris Peace Conference

Provisions of the Treaty of London were a major point of dispute between Italy and the remaining Entente powers at the Paris Peace Conference. The chief Italian representatives, Prime Minister

Provisions of the Treaty of London were a major point of dispute between Italy and the remaining Entente powers at the Paris Peace Conference. The chief Italian representatives, Prime Minister Vittorio Emanuele Orlando

Vittorio Emanuele Orlando (; 19 May 1860 – 1 December 1952) was an Italian statesman, who served as the prime minister of Italy from October 1917 to June 1919. Orlando is best known for representing Italy in the 1919 Paris Peace Conference with ...

and Sonnino demanded enforcement of the Treaty of London relying on application of the security principle, and annexation of Rijeka on the basis of self-determination. The British and the French would not publicly endorse any claims exceeding those afforded by the treaty while privately holding Italy deserved little because of its reserved attitude towards Germany in early stages of the war.

The French and the British let the President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal government of t ...

, Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

, hold Italian ambitions in check in the Adriatic by advocating self-determination of the area in accordance with point nine of his Fourteen Points

The Fourteen Points was a statement of principles for peace that was to be used for peace negotiations in order to end World War I. The principles were outlined in a January 8, 1918 speech on war aims and peace terms to the United States Congress ...

. Wilson deemed the Treaty of London a symbol of perfidy

In the context of war, perfidy is a form of deceptive tactic where one side pretends to act in good faith, such as signaling a truce (e.g., raising a white flag), but does so with the deliberate intention of breaking that promise. The goal is t ...

of European diplomacy. He held the treaty invalid by application of the legal doctrine of clausula rebus sic stantibus on account of fundamental changes of circumstances following the breakup of Austria-Hungary. While the British and the French representatives remained passive on the issue, Wilson published a manifesto explaining his principles and appealing for sense of justice among Italians on 24 April 1919. Orlando and Sonnino left Paris in protest and were celebrated in Italy as champions of national honour. Even after their return on 7 May, they refused to take any initiative expecting a conciliatory offer from the Allies. In absence of the Italian delegation, the French and the British decided to annul the Agreement of Saint-Jean-de-Maurienne for lack of Russian consent and not to honour any Italian claims in Asia Minor

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

or Africa.

Orlando and Sonnino held different positions regarding the eastern Adriatic shore claims. Orlando was prepared to give up on Dalmatia except Zadar and Šibenik while insisting on annexing Rijeka. Sonnino held the opposite view. This led to adoption of a widely publicised slogan of "Pact of London plus Fiume" and demanding the London Treaty promises and Rijeka becoming the matter of Italian national honour. Ultimately, Italian gains on the eastern Adriatic shore were limited to the Julian March, Istria, and several islands. Rijeka was assigned the status of an independent city, following negotiations between Orlando and Trumbić. Italian gains included corrections of the Treaty of London borders around Tarvisio to give Italy a direct rail link with Austria. In Dalmatia, the British Prime Minister David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. A Liberal Party (United Kingdom), Liberal Party politician from Wales, he was known for leadi ...

only supported a free-city status for Zadar and Šibenik, while French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau

Georges Benjamin Clemenceau (28 September 1841 – 24 November 1929) was a French statesman who was Prime Minister of France from 1906 to 1909 and again from 1917 until 1920. A physician turned journalist, he played a central role in the poli ...

only supported such a status for Zadar. In the secret Venizelos–Tittoni agreement, Italy renounced its claims over the Dodecanese Islands except for Rhodes

Rhodes (; ) is the largest of the Dodecanese islands of Greece and is their historical capital; it is the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, ninth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea. Administratively, the island forms a separ ...

in favour of Greece while the two countries agreed to support each other's claims in partition of Albania.

Mutilated victory

Orlando's and Sonnino's inability to secure all the territory promised by the Treaty of London or the city ofRijeka

Rijeka (;

Fiume ( �fjuːme in Italian and in Fiuman dialect, Fiuman Venetian) is the principal seaport and the List of cities and towns in Croatia, third-largest city in Croatia. It is located in Primorje-Gorski Kotar County on Kvarner Ba ...

produced a sense that Italy was losing the peace. Patriotic fervour gave way to nationalistic grievance and the government was seen as incapable of defending national interests. Orlando's successor as Prime Minister, Francesco Saverio Nitti

Francesco Saverio Vincenzo de Paola Nitti (; 19 July 1868 – 20 February 1953) was an Italian economist and statesman. A member of the Italian Radical Party, Nitti served as Prime Minister of Italy between 1919 and 1920. An opponent of the ...

, decided to pull out occupying Italian troops from Rijeka and hand the city over to the inter-Allied military command. That prompted D'Annunzio to lead a force consisting of veterans and rebelling soldiers (with the support of regular troops deployed in the border area) in what became known as the '' Impresa di Fiume'' to the successful capture of Rijeka. D'Annunzio declared the Italian Regency of Carnaro

The Italian Regency of Carnaro () was a self-proclaimed state in the city of Fiume (now Rijeka, Croatia) led by Gabriele d'Annunzio between 1919 and 1920.

During World War I (1914–1918), which the Kingdom of Italy entered on the side of t ...

in the city; its system of government influenced the development of Fascism

Fascism ( ) is a far-right, authoritarian, and ultranationalist political ideology and movement. It is characterized by a dictatorial leader, centralized autocracy, militarism, forcible suppression of opposition, belief in a natural social hie ...

. It became a model for an alternative parliamentary order sought by the Fascists.

The ''Impresa di Fiume'' brought about the fall of the Nitti government under pressure from the Italian Socialist Party

The Italian Socialist Party (, PSI) was a Social democracy, social democratic and Democratic socialism, democratic socialist political party in Italy, whose history stretched for longer than a century, making it one of the longest-living parti ...

, D'Annunzio, and Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

. Nitti's successor Giolitti and "democratic renouncers" of Dalmatian heritage were next criticised by the nationalists. D'Annunzio formulated the charge in the slogan "Victory of ours, you shall not be mutilated", referencing the promise of Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; ; ) is a historical region located in modern-day Croatia and Montenegro, on the eastern shore of the Adriatic Sea. Through time it formed part of several historical states, most notably the Roman Empire, the Kingdom of Croatia (925 ...

given in the Treaty of London, failure to annex the "utterly Italian" city of Rijeka, and elusive Adriatic domination as rendering Italian participation in the war meaningless. His position thus gave rise to the myth of the mutilated victory

Mutilated victory () is a term coined by Gabriele D'Annunzio at the end of World War I, used by a part of Italian nationalists to denounce the partial infringement (and request the full application) of the 1915 pact of London concerning territori ...

.

Following the , in what is termed the 1920 Vlora War, Albanian forces forced out the Italian garrison deployed to Vlorë; the latter retained Sazan Island. On 22 July, Italy renounced the Venizelos–Tittoni agreement and guaranteed Albanian independence within its 1913 borders instead. Italy directly contacted the newly established Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes

The Kingdom of Yugoslavia was a country in Southeast and Central Europe that existed from 1918 until 1941. From 1918 to 1929, it was officially called the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, but the term "Yugoslavia" () has been its colloq ...

for a compromise on their borders on the eastern Adriatic shores. The border was settled by the Treaty of Rapallo, conceding a little of the hoped for northern gains (within today's largely Slovene Littoral

The Slovene Littoral, or simply Littoral (, ; ; ), is one of the traditional regions of Slovenia. The littoral in its name – for a coastal-adjacent area – recalls the former Austrian Littoral (''Avstrijsko Primorje''), the Habsburg possess ...

(also called Austrian Littoral

The Austrian Littoral (, , , , ) was a crown land (''Kronland'') of the Austrian Empire, established in 1849. It consisted of three regions: the Margraviate of Istria in the south, Gorizia and Gradisca in the north, and the Imperial Free City ...

, coast or Julian March)) but gaining Istria

Istria ( ; Croatian language, Croatian and Slovene language, Slovene: ; Italian language, Italian and Venetian language, Venetian: ; ; Istro-Romanian language, Istro-Romanian: ; ; ) is the largest peninsula within the Adriatic Sea. Located at th ...

and the city-enclave of Zadar

Zadar ( , ), historically known as Zara (from Venetian and Italian, ; see also other names), is the oldest continuously inhabited city in Croatia. It is situated on the Adriatic Sea, at the northwestern part of Ravni Kotari region. Zadar ...

and several islands. Giolitti had the Italian Navy

The Italian Navy (; abbreviated as MM) is one of the four branches of Italian Armed Forces and was formed in 1946 from what remained of the ''Regia Marina'' (Royal Navy) after World War II. , the Italian Navy had a strength of 30,923 active per ...

drive D'Annunzio from Rijeka, and the city became the Free State of Fiume

The Free State of Fiume () was an independent free state that existed from 1920 to 1924. Its territory of comprised the city of Fiume (today Rijeka, Croatia) and rural areas to its north, with a corridor to its west connecting it to the Kingdo ...

under provisions of the Treaty of Rapallo. It comprised settlement of the border awarding Italy territory on the Snežnik Plateau north of Rijeka and a strip of land between the city and Italian-controlled Istria. The Treaty of Rapallo nonetheless added 350,000 Slovenes and Croats to the population of Italy.

See also

*Treaties of Rome

The Treaty of Rome, or EEC Treaty (officially the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community), brought about the creation of the European Economic Community (EEC), the best known of the European Communities (EC). The treaty was signe ...

– 1941 treaties agreed with states under the effective control of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

awarding Italy the unfulfilled parts of Dalmatia and small parts of adjacent shores.

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Treaty Of London (1915) 1915 in London 1915 in Italy Modern history of Italy 1915 in Croatia Partition (politics) London (1915), Treaty of Treaties concluded in 1915 London (1915), Treaty of London (1915), Treaty of London (1915), Treaty of London (1915), Treaty of London (1915), Treaty of Political history of Slovenia 20th century in Slovenia France–Italy relations Italy–United Kingdom relations Italy–Russia relations Konya vilayet History of the Slovene Littoral Kingdom of Serbia Kingdom of Montenegro Adriatic question April 1915 in Europe H. H. Asquith London in World War I