Locomotion In Animals on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In

In

In water, staying afloat is possible using buoyancy. If an animal's body is less dense than water, it can stay afloat. This requires little energy to maintain a vertical position, but requires more energy for locomotion in the horizontal plane compared to less buoyant animals. The drag encountered in water is much greater than in air. Morphology is therefore important for efficient locomotion, which is in most cases essential for basic functions such as catching prey. A fusiform,

In water, staying afloat is possible using buoyancy. If an animal's body is less dense than water, it can stay afloat. This requires little energy to maintain a vertical position, but requires more energy for locomotion in the horizontal plane compared to less buoyant animals. The drag encountered in water is much greater than in air. Morphology is therefore important for efficient locomotion, which is in most cases essential for basic functions such as catching prey. A fusiform,

''

''

Gravity is the primary obstacle to

Gravity is the primary obstacle to

Some aquatic animals also regularly use gliding, for example,

Some aquatic animals also regularly use gliding, for example,

Many familiar animals are

Many familiar animals are

File:Ostrich running.ogv, Bipedal ostrich

File:2013-05-09 15-20-00-Extatosoma-tiaratum.ogv, Hexapedal stick-insect

File:Evarcha arcuata (female), Wollenberg, Hesse, Germany - 20110429.ogv, Octopedal locomotion by a spider

File:Red millipede crawling on a wall.webm, Multi-legged millipede

The

The

When swimming, several marine mammals such as dolphins, porpoises and pinnipeds, frequently leap above the water surface whilst maintaining horizontal locomotion. This is done for various reasons. When travelling, jumping can save dolphins and porpoises energy as there is less friction while in the air. This type of travel is known as "porpoising". Other reasons for dolphins and porpoises performing porpoising include orientation, social displays, fighting,

When swimming, several marine mammals such as dolphins, porpoises and pinnipeds, frequently leap above the water surface whilst maintaining horizontal locomotion. This is done for various reasons. When travelling, jumping can save dolphins and porpoises energy as there is less friction while in the air. This type of travel is known as "porpoising". Other reasons for dolphins and porpoises performing porpoising include orientation, social displays, fighting,

Beetle Orientation

{{Authority control Ethology Zoology Animals Articles containing video clips

In

In ethology

Ethology is a branch of zoology that studies the behavior, behaviour of non-human animals. It has its scientific roots in the work of Charles Darwin and of American and German ornithology, ornithologists of the late 19th and early 20th cen ...

, animal locomotion is any of a variety of methods that animal

Animals are multicellular, eukaryotic organisms in the Biology, biological Kingdom (biology), kingdom Animalia (). With few exceptions, animals heterotroph, consume organic material, Cellular respiration#Aerobic respiration, breathe oxygen, ...

s use to move from one place to another. Some modes of locomotion are (initially) self-propelled, e.g., running

Running is a method of terrestrial locomotion by which humans and other animals move quickly on foot. Running is a gait with an aerial phase in which all feet are above the ground (though there are exceptions). This is in contrast to walkin ...

, swimming

Swimming is the self-propulsion of a person through water, such as saltwater or freshwater environments, usually for recreation, sport, exercise, or survival. Swimmers achieve locomotion by coordinating limb and body movements to achieve hydrody ...

, jumping

Jumping or leaping is a form of locomotion or movement in which an organism or non-living (e.g., robotic) mechanical system propels itself through the air along a ballistic trajectory. Jumping can be distinguished from running, galloping and ...

, flying

Flying may refer to:

* Flight, the process of flying

* Aviation, the creation and operation of aircraft

Music

Albums

* '' Flying (Cody Fry album)'', 2017

* ''Flying'' (Grammatrain album), 1997

* ''Flying'' (Jonathan Fagerlund album), 2008

* ...

, hopping, soaring and gliding

Gliding is a recreational activity and competitive air sports, air sport in which pilots fly glider aircraft, unpowered aircraft known as Glider (sailplane), gliders or sailplanes using naturally occurring currents of rising air in the atmospher ...

. There are also many animal species that depend on their environment for transportation, a type of mobility called passive locomotion, e.g., sailing (some jellyfish

Jellyfish, also known as sea jellies or simply jellies, are the #Life cycle, medusa-phase of certain gelatinous members of the subphylum Medusozoa, which is a major part of the phylum Cnidaria. Jellyfish are mainly free-swimming marine animal ...

), kiting (spider

Spiders (order (biology), order Araneae) are air-breathing arthropods that have eight limbs, chelicerae with fangs generally able to inject venom, and spinnerets that extrude spider silk, silk. They are the largest order of arachnids and ran ...

s), rolling

Rolling is a Motion (physics)#Types of motion, type of motion that combines rotation (commonly, of an Axial symmetry, axially symmetric object) and Translation (geometry), translation of that object with respect to a surface (either one or the ot ...

(some beetle

Beetles are insects that form the Taxonomic rank, order Coleoptera (), in the superorder Holometabola. Their front pair of wings are hardened into wing-cases, elytra, distinguishing them from most other insects. The Coleoptera, with about 40 ...

s and spiders) or riding other animals (phoresis

Phoresis or phoresy is a temporary commensalistic relationship when an organism (a phoront or phoretic) attaches itself to a host organism solely for travel. It has been seen in ticks and mites since the 18th century, and in fossils 320 ...

).

Animals move for a variety of reasons, such as to find food, a mate

Mate may refer to:

Science

* Mate, one of a pair of animals involved in:

** Mate choice, intersexual selection

*** Mate choice in humans

** Mating

* Multi-antimicrobial extrusion protein, or MATE, an efflux transporter family of proteins

Pers ...

, a suitable microhabitat

In ecology, habitat refers to the array of resources, biotic factors that are present in an area, such as to support the survival and reproduction of a particular species. A species' habitat can be seen as the physical manifestation of its ...

, or to escape predators. For many animals, the ability to move is essential for survival and, as a result, natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the Heredity, heritable traits characteristic of a population over generation ...

has shaped the locomotion methods and mechanisms used by moving organisms. For example, migratory animals that travel vast distances (such as the Arctic tern

The Arctic tern (''Sterna paradisaea'') is a tern in the family Laridae. This bird has a circumpolar breeding distribution covering the Arctic and sub-Arctic regions of Europe (as far south as Brittany), Asia, and North America (as far south ...

) typically have a locomotion mechanism that costs very little energy per unit distance, whereas non-migratory animals that must frequently move quickly to escape predators are likely to have energetically costly, but very fast, locomotion.

The anatomical structures that animals use for movement, including cilia

The cilium (: cilia; ; in Medieval Latin and in anatomy, ''cilium'') is a short hair-like membrane protrusion from many types of eukaryotic cell. (Cilia are absent in bacteria and archaea.) The cilium has the shape of a slender threadlike proj ...

, leg

A leg is a weight-bearing and locomotive anatomical structure, usually having a columnar shape. During locomotion, legs function as "extensible struts". The combination of movements at all joints can be modeled as a single, linear element cap ...

s, wing

A wing is a type of fin that produces both Lift (force), lift and drag while moving through air. Wings are defined by two shape characteristics, an airfoil section and a planform (aeronautics), planform. Wing efficiency is expressed as lift-to-d ...

s, arm

In human anatomy, the arm refers to the upper limb in common usage, although academically the term specifically means the upper arm between the glenohumeral joint (shoulder joint) and the elbow joint. The distal part of the upper limb between ...

s, fin

A fin is a thin component or appendage attached to a larger body or structure. Fins typically function as foils that produce lift or thrust, or provide the ability to steer or stabilize motion while traveling in water, air, or other fluids. F ...

s, or tail

The tail is the elongated section at the rear end of a bilaterian animal's body; in general, the term refers to a distinct, flexible appendage extending backwards from the midline of the torso. In vertebrate animals that evolution, evolved to los ...

s are sometimes referred to as ''locomotory organs'' or ''locomotory structures''.

Etymology

The term "locomotion" is formed in English from Latin ''loco'' "from a place" (ablative of ''locus'' "place") + ''motio'' "motion, a moving". The movement of whole body is called locomotionAquatic

Swimming

In water, staying afloat is possible using buoyancy. If an animal's body is less dense than water, it can stay afloat. This requires little energy to maintain a vertical position, but requires more energy for locomotion in the horizontal plane compared to less buoyant animals. The drag encountered in water is much greater than in air. Morphology is therefore important for efficient locomotion, which is in most cases essential for basic functions such as catching prey. A fusiform,

In water, staying afloat is possible using buoyancy. If an animal's body is less dense than water, it can stay afloat. This requires little energy to maintain a vertical position, but requires more energy for locomotion in the horizontal plane compared to less buoyant animals. The drag encountered in water is much greater than in air. Morphology is therefore important for efficient locomotion, which is in most cases essential for basic functions such as catching prey. A fusiform, torpedo

A modern torpedo is an underwater ranged weapon launched above or below the water surface, self-propelled towards a target, with an explosive warhead designed to detonate either on contact with or in proximity to the target. Historically, such ...

-like body form is seen in many aquatic animals, though the mechanisms they use for locomotion are diverse.

The primary means by which fish

A fish (: fish or fishes) is an aquatic animal, aquatic, Anamniotes, anamniotic, gill-bearing vertebrate animal with swimming fish fin, fins and craniate, a hard skull, but lacking limb (anatomy), limbs with digit (anatomy), digits. Fish can ...

generate thrust

Thrust is a reaction force described quantitatively by Newton's third law. When a system expels or accelerates mass in one direction, the accelerated mass will cause a force of equal magnitude but opposite direction to be applied to that ...

is by oscillating the body from side-to-side, the resulting wave motion ending at a large tail fin. Finer control, such as for slow movements, is often achieved with thrust from pectoral fins

Fins are moving appendages protruding from the body of fish that interact with water to generate thrust and help the fish swim. Apart from the tail or caudal fin, fish fins have no direct connection with the back bone and are supported only b ...

(or front limbs in marine mammals). Some fish, e.g. the spotted ratfish (''Hydrolagus colliei'') and batiform fish (electric rays, sawfishes, guitarfishes, skates and stingrays) use their pectoral fins as the primary means of locomotion, sometimes termed labriform swimming. Marine mammal

Marine mammals are mammals that rely on marine ecosystems for their existence. They include animals such as cetaceans, pinnipeds, sirenians, sea otters and polar bears. They are an informal group, unified only by their reliance on marine enviro ...

s oscillate their body in an up-and-down (dorso-ventral) direction.

Other animals, e.g. penguins, diving ducks, move underwater in a manner which has been termed "aquatic flying". Some fish propel themselves without a wave motion of the body, as in the slow-moving seahorses and ''Gymnotus

''Gymnotus'' is a genus of Neotropical freshwater fish in the family Gymnotidae found widely in South America, Central America and southern Mexico ( 36th parallel south to 18th parallel north). The greatest species richness is found in the Amaz ...

''.

Other animals, such as cephalopods

A cephalopod is any member of the molluscan Taxonomic rank, class Cephalopoda (Greek language, Greek plural , ; "head-feet") such as a squid, octopus, cuttlefish, or nautilus. These exclusively marine animals are characterized by bilateral symm ...

, use jet propulsion to travel fast, taking in water then squirting it back out in an explosive burst. Other swimming animals may rely predominantly on their limbs, much as humans do when swimming. Though life on land originated from the seas, terrestrial animals have returned to an aquatic lifestyle on several occasions, such as the fully aquatic cetacean

Cetacea (; , ) is an infraorder of aquatic mammals belonging to the order Artiodactyla that includes whales, dolphins and porpoises. Key characteristics are their fully aquatic lifestyle, streamlined body shape, often large size and exclusively c ...

s, now very distinct from their terrestrial ancestors.

Dolphins sometimes ride on the bow wave

A bow wave is the wave that forms at the bow (watercraft), bow of a ship when it moves through the water. As the bow wave spreads out, it defines the outer limits of a ship's Wake (physics), wake. A large bow wave slows the ship down, is a risk t ...

s created by boats or surf on naturally breaking waves.

Benthic

Benthic

The benthic zone is the ecological region at the lowest level of a body of water such as an ocean, lake, or stream, including the sediment surface and some sub-surface layers. The name comes from the Ancient Greek word (), meaning "the depths". ...

locomotion is movement by animals that live on, in, or near the bottom of aquatic environments. In the sea, many animals walk over the seabed. Echinoderms

An echinoderm () is any animal of the phylum Echinodermata (), which includes starfish, brittle stars, sea urchins, sand dollars and sea cucumbers, as well as the sessile sea lilies or "stone lilies". While bilaterally symmetrical as larv ...

primarily use their tube feet

Tube or tubes may refer to:

* Tube (2003 film), ''Tube'' (2003 film), a 2003 Korean film

* "Tubes" (Peter Dale), performer on the Soccer AM#Tubes, Soccer AM television show

* Tube (band), a Japanese rock band

* Tube & Berger, the alias of dance/e ...

to move about. The tube feet typically have a tip shaped like a suction pad that can create a vacuum through contraction of muscles. This, along with some stickiness from the secretion of mucus

Mucus (, ) is a slippery aqueous secretion produced by, and covering, mucous membranes. It is typically produced from cells found in mucous glands, although it may also originate from mixed glands, which contain both Serous fluid, serous and muc ...

, provides adhesion. Waves of tube feet contractions and relaxations move along the adherent surface and the animal moves slowly along. Some sea urchins also use their spines for benthic locomotion.

Crabs typically walk sideways (a behaviour that gives us the word ''crabwise''). This is because of the articulation of the legs, which makes a sidelong gait more efficient. However, some crabs walk forwards or backwards, including raninids, ''Libinia emarginata

''Libinia emarginata'', the portly spider crab, common spider crab or nine-spined spider crab, is a species of stenohaline crab that lives on the Atlantic coast of North America.

Distribution

''Libinia emarginata'' occurs from Nova Scotia to th ...

'' and ''Mictyris platycheles

''Mictyris platycheles'' is a species of crab found on mudflats on the east coast of Australia from Tasmania and Victoria to Queensland

Queensland ( , commonly abbreviated as Qld) is a States and territories of Australia, state in northea ...

''. Some crabs, notably the Portunidae

Portunidae is a family of crabs which contains the swimming crabs. Its members include well-known shoreline crabs such as the blue crab (''Callinectes sapidus'') and velvet crab ('' Necora puber'').

Description

Portunid crabs are characterised b ...

and Matutidae

Matutidae is a family (biology), family of crabs, sometimes called ''moon crabs'', adaptation, adapted for swimming or digging. They differ from the swimming crabs of the family Portunidae in that all five pairs of arthropod leg, legs are flatten ...

, are also capable of swimming, the Portunidae

Portunidae is a family of crabs which contains the swimming crabs. Its members include well-known shoreline crabs such as the blue crab (''Callinectes sapidus'') and velvet crab ('' Necora puber'').

Description

Portunid crabs are characterised b ...

especially so as their last pair of walking legs are flattened into swimming paddles.

A stomatopod, '' Nannosquilla decemspinosa'', can escape by rolling itself into a self-propelled wheel and somersault backwards at a speed of 72 rpm. They can travel more than 2 m using this unusual method of locomotion.

Aquatic surface

''

''Velella

''Velella'' is a monospecific genus of hydrozoa in the family Porpitidae. Its only known species is ''Velella velella'', a cosmopolitan (widely distributed) free-floating hydrozoan that lives on the surface of the open ocean. It is commonly kn ...

'', the by-the-wind sailor, is a cnidarian with no means of propulsion other than sailing

Sailing employs the wind—acting on sails, wingsails or kites—to propel a craft on the surface of the ''water'' (sailing ship, sailboat, raft, Windsurfing, windsurfer, or Kitesurfing, kitesurfer), on ''ice'' (iceboat) or on ''land'' (Land sa ...

. A small rigid sail projects into the air and catches the wind. ''Velella'' sails always align along the direction of the wind where the sail may act as an aerofoil

An airfoil (American English) or aerofoil (British English) is a streamlined body that is capable of generating significantly more lift than drag. Wings, sails and propeller blades are examples of airfoils. Foils of similar function designed ...

, so that the animals tend to sail downwind at a small angle to the wind.

While larger animals such as ducks can move on water by floating, some small animals move across it without breaking through the surface. This surface locomotion takes advantage of the surface tension

Surface tension is the tendency of liquid surfaces at rest to shrink into the minimum surface area possible. Surface tension (physics), tension is what allows objects with a higher density than water such as razor blades and insects (e.g. Ge ...

of water. Animals that move in such a way include the water strider

The Gerridae are a family of insects in the order Hemiptera, commonly known as water striders, water skeeters, water scooters, water bugs, pond skaters, water skippers, water gliders, water skimmers or puddle flies. They are true bugs of the ...

. Water striders have legs that are hydrophobic

In chemistry, hydrophobicity is the chemical property of a molecule (called a hydrophobe) that is seemingly repelled from a mass of water. In contrast, hydrophiles are attracted to water.

Hydrophobic molecules tend to be nonpolar and, thu ...

, preventing them from interfering with the structure of water. Another form of locomotion (in which the surface layer is broken) is used by the basilisk lizard

''Basiliscus'' is a genus of large corytophanid lizards, commonly known as basilisks, which are endemic to southern Mexico, Central America, and northern South America. The genus contains four species, which are commonly known as the Jesus Chr ...

.

Aerial

Active flight

Gravity is the primary obstacle to

Gravity is the primary obstacle to flight

Flight or flying is the motion (physics), motion of an Physical object, object through an atmosphere, or through the vacuum of Outer space, space, without contacting any planetary surface. This can be achieved by generating aerodynamic lift ass ...

. Because it is impossible for any organism to have a density as low as that of air, flying animals must generate enough lift

Lift or LIFT may refer to:

Physical devices

* Elevator, or lift, a device used for raising and lowering people or goods

** Paternoster lift, a type of lift using a continuous chain of cars which do not stop

** Patient lift, or Hoyer lift, mobile ...

to ascend and remain airborne. One way to achieve this is with wing

A wing is a type of fin that produces both Lift (force), lift and drag while moving through air. Wings are defined by two shape characteristics, an airfoil section and a planform (aeronautics), planform. Wing efficiency is expressed as lift-to-d ...

s, which when moved through the air generate an upward lift force

When a fluid flows around an object, the fluid exerts a force on the object. Lift is the component of this force that is perpendicular to the oncoming flow direction. It contrasts with the drag force, which is the component of the force parall ...

on the animal's body. Flying animals must be very light to achieve flight, the largest living flying animals being birds of around 20 kilograms. Other structural adaptations of flying animals include reduced and redistributed body weight, fusiform shape and powerful flight muscles; there may also be physiological adaptations. Active flight has independently evolved at least four times, in the insect

Insects (from Latin ') are Hexapoda, hexapod invertebrates of the class (biology), class Insecta. They are the largest group within the arthropod phylum. Insects have a chitinous exoskeleton, a three-part body (Insect morphology#Head, head, ...

s, pterosaur

Pterosaurs are an extinct clade of flying reptiles in the order Pterosauria. They existed during most of the Mesozoic: from the Late Triassic to the end of the Cretaceous (228 million to 66 million years ago). Pterosaurs are the earli ...

s, bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class (biology), class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the Oviparity, laying of Eggshell, hard-shelled eggs, a high Metabolism, metabolic rate, a fou ...

s, and bat

Bats are flying mammals of the order Chiroptera (). With their forelimbs adapted as wings, they are the only mammals capable of true and sustained flight. Bats are more agile in flight than most birds, flying with their very long spread-out ...

s. Insects were the first taxon to evolve flight, approximately 400 million years ago (mya), followed by pterosaurs approximately 220 mya, birds approximately 160 mya, then bats about 60 mya.

Gliding

Rather than active flight, some (semi-) arboreal animals reduce their rate of falling bygliding

Gliding is a recreational activity and competitive air sports, air sport in which pilots fly glider aircraft, unpowered aircraft known as Glider (sailplane), gliders or sailplanes using naturally occurring currents of rising air in the atmospher ...

. Gliding is heavier-than-air flight without the use of thrust

Thrust is a reaction force described quantitatively by Newton's third law. When a system expels or accelerates mass in one direction, the accelerated mass will cause a force of equal magnitude but opposite direction to be applied to that ...

; the term "volplaning" also refers to this mode of flight in animals. This mode of flight involves flying a greater distance horizontally than vertically and therefore can be distinguished from a simple descent like a parachute. Gliding has evolved on more occasions than active flight. There are examples of gliding animals in several major taxonomic classes such as the invertebrates (e.g., gliding ant

Gliding ants are arboreal ants of several different genera that are able to control the direction of their descent when falling from a tree. Living in the rainforest canopy like many other gliders, gliding ants use their gliding to return to the ...

s), reptiles (e.g., banded flying snake), amphibians (e.g., flying frog

A flying frog (also called a gliding frog) is a frog that has the ability to achieve gliding flight. This means it can descend at an angle less than 45° relative to the horizontal. Other nonflying arboreal frogs can also descend, but only at an ...

), mammals (e.g., sugar glider

The sugar glider (''Petaurus breviceps'') is a small, omnivorous, arboreal, and nocturnal gliding possum. The common name refers to its predilection for sugary foods such as sap and nectar and its ability to glide through the air, much lik ...

, squirrel glider

The squirrel glider (''Petaurus norfolcensis'') is a nocturnal gliding possum. The squirrel glider is one of the wrist-winged gliders of the genus '' Petaurus''.

Habitat

This species' home range extends from Bordertown near the South Austral ...

).

Some aquatic animals also regularly use gliding, for example,

Some aquatic animals also regularly use gliding, for example, flying fish

The Exocoetidae are a family (biology), family of Saltwater fish, marine Actinopterygii, ray-finned fish in the order (biology), order Beloniformes, known colloquially as flying fish or flying cod. About 64 species are grouped in seven genus, ge ...

, octopus and squid. The flights of flying fish are typically around 50 meters (160 ft),Ross Piper

Ross Piper is a British zoologist, entomologist, and explorer.

Biography

Piper's fascination by animals began at a young age through early encounters with a violet ground beetle and the caterpillar of an elephant hawk moth. This early interest ...

(2007), ''Extraordinary Animals: An Encyclopedia of Curious and Unusual Animals'', Greenwood Press

Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. (GPG) was an educational and academic publisher (middle school through university level) which was part of ABC-Clio. Since 2021, ABC-Clio and its suite of imprints, including GPG, are collectively imprints of B ...

. though they can use updrafts at the leading edge of waves to cover distances of up to . To glide upward out of the water, a flying fish moves its tail up to 70 times per second.

Several oceanic squid

A squid (: squid) is a mollusc with an elongated soft body, large eyes, eight cephalopod limb, arms, and two tentacles in the orders Myopsida, Oegopsida, and Bathyteuthida (though many other molluscs within the broader Neocoleoidea are also ...

, such as the Pacific flying squid, leap out of the water to escape predators, an adaptation similar to that of flying fish. Smaller squids fly in shoals, and have been observed to cover distances as long as 50 m. Small fins towards the back of the mantle help stabilize the motion of flight. They exit the water by expelling water out of their funnel, indeed some squid have been observed to continue jetting water while airborne providing thrust even after leaving the water. This may make flying squid the only animals with jet-propelled aerial locomotion. The neon flying squid has been observed to glide for distances over , at speeds of up to .

Soaring

Soaring birds can maintain flight without wing flapping, using rising air currents. Many gliding birds are able to "lock" their extended wings by means of a specialized tendon. Soaring birds may alternate glides with periods of soaring in rising air. Five principal types of lift are used:thermal

A thermal column (or thermal) is a rising mass of buoyant air, a convective current in the atmosphere, that transfers heat energy vertically. Thermals are created by the uneven heating of Earth's surface from solar radiation, and are an example ...

s, ridge lift

__NOTOC__

Ridge lift (or slope lift) is created when a wind strikes an obstacle, usually a mountain ridge or cliff, that is large and steep enough to deflect the wind upward.

If the wind is strong enough, the ridge lift provides enough upward f ...

, lee waves

In meteorology, lee waves are Earth's atmosphere, atmospheric stationary waves. The most common form is mountain waves, which are atmospheric internal gravity waves. These were discovered in 1933 by two German glider pilots, :de:Hans_Deutschmann ...

, convergences and dynamic soaring

Dynamic soaring is a flying technique used to gain energy by repeatedly crossing the boundary between air masses of different velocity. Such zones of wind gradient are generally found close to obstacles and close to the surface, so the technique is ...

.

Examples of soaring flight by birds are the use of:

*Thermals and convergences by raptor

Raptor(s) or RAPTOR may refer to:

Animals

The word "raptor" refers to several groups of avian and non-avian dinosaurs which primarily capture and subdue/kill prey with their talons.

* Raptor (bird) or bird of prey, a bird that primarily hunt ...

s such as vulture

A vulture is a bird of prey that scavenges on carrion. There are 23 extant species of vulture (including condors). Old World vultures include 16 living species native to Europe, Africa, and Asia; New World vultures are restricted to Nort ...

s

*Ridge lift by gull

Gulls, or colloquially seagulls, are seabirds of the subfamily Larinae. They are most closely related to terns and skimmers, distantly related to auks, and even more distantly related to waders. Until the 21st century, most gulls were placed ...

s near cliffs

*Wave lift by migrating birds

*Dynamic effects near the surface of the sea by albatross

Albatrosses, of the biological family Diomedeidae, are large seabirds related to the procellariids, storm petrels, and diving petrels in the order Procellariiformes (the tubenoses). They range widely in the Southern Ocean and the North Paci ...

es

Ballooning

Ballooning Ballooning may refer to:

* Hot air ballooning

* Balloon (aeronautics)

* Ballooning (spider)

* Ballooning degeneration, a disease

* Memory ballooning

In computing, memory ballooning is a technique that is used to eliminate the need to overcommit ...

is a method of locomotion used by spiders. Certain silk-producing arthropod

Arthropods ( ) are invertebrates in the phylum Arthropoda. They possess an arthropod exoskeleton, exoskeleton with a cuticle made of chitin, often Mineralization (biology), mineralised with calcium carbonate, a body with differentiated (Metam ...

s, mostly small or young spiders, secrete a special light-weight gossamer silk for ballooning, sometimes traveling great distances at high altitude.

Terrestrial

Forms of locomotion on land include walking, running, hopping orjumping

Jumping or leaping is a form of locomotion or movement in which an organism or non-living (e.g., robotic) mechanical system propels itself through the air along a ballistic trajectory. Jumping can be distinguished from running, galloping and ...

, dragging and crawling or slithering. Here friction and buoyancy are no longer an issue, but a strong skeletal

A skeleton is the structural frame that supports the body of most animals. There are several types of skeletons, including the exoskeleton, which is a rigid outer shell that holds up an organism's shape; the endoskeleton, a rigid internal fram ...

and muscular

MUSCULAR (DS-200B), located in the United Kingdom, is the name of a surveillance program jointly operated by Britain's Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) and the U.S. National Security Agency (NSA) that was revealed by documents release ...

framework are required in most terrestrial animals for structural support. Each step also requires much energy to overcome inertia

Inertia is the natural tendency of objects in motion to stay in motion and objects at rest to stay at rest, unless a force causes the velocity to change. It is one of the fundamental principles in classical physics, and described by Isaac Newto ...

, and animals can store elastic potential energy

Elastic energy is the mechanical potential energy stored in the configuration of a material or physical system as it is subjected to elastic deformation by work performed upon it. Elastic energy occurs when objects are impermanently compressed, s ...

in their tendon

A tendon or sinew is a tough band of fibrous connective tissue, dense fibrous connective tissue that connects skeletal muscle, muscle to bone. It sends the mechanical forces of muscle contraction to the skeletal system, while withstanding tensi ...

s to help overcome this. Balance

Balance may refer to:

Common meanings

* Balance (ability) in biomechanics

* Balance (accounting)

* Balance or weighing scale

* Balance, as in equality (mathematics) or equilibrium

Arts and entertainment Film

* Balance (1983 film), ''Balance'' ( ...

is also required for movement on land. Human infant

In common terminology, a baby is the very young offspring of adult human beings, while infant (from the Latin word ''infans'', meaning 'baby' or 'child') is a formal or specialised synonym. The terms may also be used to refer to juveniles of ...

s learn to crawl

Crawl, The Crawl, or crawling may refer to:

Biology

* Crawling, any type of tetrapod quadrupedal locomotion with the torso persistently touching or very close to the ground.

** Crawling (human), any of several types of human quadrupedal gait

* L ...

first before they are able to stand on two feet, which requires good coordination as well as physical development. Humans are bipedal

Bipedalism is a form of terrestrial locomotion where an animal moves by means of its two rear (or lower) limbs or legs. An animal or machine that usually moves in a bipedal manner is known as a biped , meaning 'two feet' (from Latin ''bis'' ...

animals, standing on two feet and keeping one on the ground at all times while walking

Walking (also known as ambulation) is one of the main gaits of terrestrial locomotion among legged animals. Walking is typically slower than running and other gaits. Walking is defined as an " inverted pendulum" gait in which the body vaults o ...

. When running

Running is a method of terrestrial locomotion by which humans and other animals move quickly on foot. Running is a gait with an aerial phase in which all feet are above the ground (though there are exceptions). This is in contrast to walkin ...

, only one foot

The foot (: feet) is an anatomical structure found in many vertebrates. It is the terminal portion of a limb which bears weight and allows locomotion. In many animals with feet, the foot is an organ at the terminal part of the leg made up o ...

is on the ground at any one time at most, and both leave the ground briefly. At higher speeds momentum

In Newtonian mechanics, momentum (: momenta or momentums; more specifically linear momentum or translational momentum) is the product of the mass and velocity of an object. It is a vector quantity, possessing a magnitude and a direction. ...

helps keep the body upright, so more energy can be used in movement.

Jumping

Jumping (saltation) can be distinguished from running, galloping, and other gaits where the entire body is temporarily airborne by the relatively long duration of the aerial phase and high angle of initial launch. Many terrestrial animals use jumping (including hopping or leaping) to escape predators or catch prey—however, relatively few animals use this as a primary mode of locomotion. Those that do include thekangaroo

Kangaroos are marsupials from the family Macropodidae (macropods, meaning "large foot"). In common use, the term is used to describe the largest species from this family, the red kangaroo, as well as the antilopine kangaroo, eastern gre ...

and other macropods, rabbit

Rabbits are small mammals in the family Leporidae (which also includes the hares), which is in the order Lagomorpha (which also includes pikas). They are familiar throughout the world as a small herbivore, a prey animal, a domesticated ...

, hare

Hares and jackrabbits are mammals belonging to the genus ''Lepus''. They are herbivores and live Solitary animal, solitarily or in pairs. They nest in slight depressions called forms, and their young are precociality, able to fend for themselves ...

, jerboa

Jerboas () are the members of the family Dipodidae. They are hopping desert rodents found throughout North Africa and Asia. They tend to live in hot deserts.

When chased, jerboas can run at up to . Some species are preyed on by little owls (''A ...

, hopping mouse

A hopping mouse is any of about ten different Australian native mice in the genus ''Notomys''. They are rodents, not marsupials, and their ancestors are thought to have arrived from Asia about 5 million years ago.

All are brown or fawn, fading t ...

, and kangaroo rat

Kangaroo rats, small mostly nocturnal rodents of genus ''Dipodomys'', are native to arid areas of western North America. The common name derives from their bipedal form. They hop in a manner similar to the much larger kangaroo, but developed thi ...

. Kangaroo rats often leap 2 m and reportedly up to 2.75 m at speeds up to almost . They can quickly change their direction between jumps. The rapid locomotion of the banner-tailed kangaroo rat may minimize energy cost and predation risk. Its use of a "move-freeze" mode may also make it less conspicuous to nocturnal predators. Frogs are, relative to their size, the best jumpers of all vertebrates. The Australian rocket frog, '' Litoria nasuta'', can leap over , more than fifty times its body length.

Peristalsis and looping

Other animals move in terrestrial habitats without the aid of legs.Earthworm

An earthworm is a soil-dwelling terrestrial invertebrate that belongs to the phylum Annelida. The term is the common name for the largest members of the class (or subclass, depending on the author) Oligochaeta. In classical systems, they we ...

s crawl by a peristalsis

Peristalsis ( , ) is a type of intestinal motility, characterized by symmetry in biology#Radial symmetry, radially symmetrical contraction and relaxation of muscles that propagate in a wave down a tube, in an wikt:anterograde, anterograde dir ...

, the same rhythmic contractions that propel food through the digestive tract.

Leech

Leeches are segmented parasitism, parasitic or Predation, predatory worms that comprise the Class (biology), subclass Hirudinea within the phylum Annelida. They are closely related to the Oligochaeta, oligochaetes, which include the earthwor ...

es and geometer moth

The geometer moths are moths belonging to the family Geometridae of the insect order Lepidoptera, the moths and butterflies. Their scientific name derives from the Ancient Greek (derivative form of or "the earth"), and "measure" in referen ...

caterpillars move by looping or inching (measuring off a length with each movement), using their paired circular and longitudinal muscles (as for peristalsis) along with the ability to attach to a surface at both anterior and posterior ends. One end is attached, often the thicker end, and the other end, often thinner, is projected forward peristaltically until it touches down, as far as it can reach; then the first end is released, pulled forward, and reattached; and the cycle repeats. In the case of leeches, attachment is by a sucker at each end of the body.

Sliding

Due to its low coefficient of friction, ice provides the opportunity for other modes of locomotion. Penguins either waddle on their feet or slide on their bellies across the snow, a movement called ''tobogganing'', which conserves energy while moving quickly. Some pinnipeds perform a similar behaviour called ''sledding''.Climbing

Some animals are specialized for moving on non-horizontal surfaces. One common habitat for such climbing animals is in trees; for example, thegibbon

Gibbons () are apes in the family Hylobatidae (). The family historically contained one genus, but now is split into four extant genera and 20 species. Gibbons live in subtropical and tropical forests from eastern Bangladesh and Northeast Indi ...

is specialized for arboreal

Arboreal locomotion is the locomotion of animals in trees. In habitats in which trees are present, animals have evolved to move in them. Some animals may scale trees only occasionally (scansorial), but others are exclusively arboreal. The hab ...

movement, travelling rapidly by brachiation

Brachiation (from "brachium", Latin for "arm"), or arm swinging, is a form of arboreal locomotion in which primates swing from tree limb to tree limb using only their arms. During brachiation, the body is alternately supported under each forelimb ...

(see below

Below may refer to:

*Earth

*Ground (disambiguation)

*Soil

*Floor

* Bottom (disambiguation)

*Less than

*Temperatures below freezing

*Hell or underworld

People with the surname

* Ernst von Below (1863–1955), German World War I general

* Fred Belo ...

).

Others living on rock faces such as in mountain

A mountain is an elevated portion of the Earth's crust, generally with steep sides that show significant exposed bedrock. Although definitions vary, a mountain may differ from a plateau in having a limited summit area, and is usually higher t ...

s move on steep or even near-vertical surfaces by careful balancing and leaping. Perhaps the most exceptional are the various types of mountain-dwelling caprids

The subfamily Caprinae, also sometimes referred to as the tribe Caprini, is part of the ruminant family Bovidae, and consists of mostly medium-sized bovids. A member of this subfamily is called a caprine.

Prominent members include sheep and go ...

(e.g., Barbary sheep

The Barbary sheep (''Ammotragus lervia''), also known as aoudad (pronounced �ɑʊdæd, is a species of caprine native to rocky mountains in North Africa and parts of West Africa. While this is the only species in genus ''Ammotragus'', six sub ...

, yak

The yak (''Bos grunniens''), also known as the Tartary ox, grunting ox, hairy cattle, or domestic yak, is a species of long-haired domesticated cattle found throughout the Himalayan region, the Tibetan Plateau, Tajikistan, the Pamir Mountains ...

, ibex

An ibex ( : ibex, ibexes or ibices) is any of several species of wild goat (genus ''Capra''), distinguished by the male's large recurved horns, which are transversely ridged in front. Ibex are found in Eurasia, North Africa and East Africa.

T ...

, rocky mountain goat

The mountain goat (''Oreamnos americanus''), also known as the Rocky Mountain goat, is a cloven-footed mammal that is endemic to the remote and rugged mountainous areas of western North America. A subalpine to truly alpine species, it is a s ...

, etc.), whose adaptations can include a soft rubbery pad between their hooves for grip, hooves with sharp keratin rims for lodging in small footholds, and prominent dew claws. Another case is the snow leopard

The snow leopard (''Panthera uncia'') is a species of large cat in the genus ''Panthera'' of the family Felidae. The species is native to the mountain ranges of Central and South Asia. It is listed as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List because ...

, which being a predator of such caprids also has spectacular balance and leaping abilities, such as ability to leap up to 17m (50ft).

Some light animals are able to climb up smooth sheer surfaces or hang upside down by adhesion

Adhesion is the tendency of dissimilar particles or interface (matter), surfaces to cling to one another. (Cohesion (chemistry), Cohesion refers to the tendency of similar or identical particles and surfaces to cling to one another.)

The ...

using suckers. Many insects can do this, though much larger animals such as gecko

Geckos are small, mostly carnivorous lizards that have a wide distribution, found on every continent except Antarctica. Belonging to the infraorder Gekkota, geckos are found in warm climates. They range from .

Geckos are unique among lizards ...

s can also perform similar feats.

Walking and running

Species have different numbers of legs resulting in large differences in locomotion. Modern birds, though classified astetrapod

A tetrapod (; from Ancient Greek :wiktionary:τετρα-#Ancient Greek, τετρα- ''(tetra-)'' 'four' and :wiktionary:πούς#Ancient Greek, πούς ''(poús)'' 'foot') is any four-Limb (anatomy), limbed vertebrate animal of the clade Tetr ...

s, usually have only two functional legs, which some (e.g., ostrich, emu, kiwi) use as their primary, Bipedal

Bipedalism is a form of terrestrial locomotion where an animal moves by means of its two rear (or lower) limbs or legs. An animal or machine that usually moves in a bipedal manner is known as a biped , meaning 'two feet' (from Latin ''bis'' ...

, mode of locomotion. A few modern mammalian species are habitual bipeds, i.e., whose normal method of locomotion is two-legged. These include the macropods

Macropod may refer to:

* Macropodidae, a marsupial family which includes kangaroos, wallabies, tree-kangaroos, pademelons, and several others

* Macropodiformes

The Macropodiformes , also known as macropods, are one of the three suborders of the ...

, kangaroo rats and mice, springhare

''Pedetes'' is a genus of rodent, the springhares, in the family Pedetidae. Members of the genus are distributed across southern and Eastern Africa.

Species

A number of species both extant and extinct are classified in the genus ''Pedetes''. ...

, hopping mice

A hopping mouse is any of about ten different Australian native mice in the genus ''Notomys''. They are rodents, not marsupials, and their ancestors are thought to have arrived from Asia about 5 million years ago.

All are brown or fawn, fading t ...

, pangolin

Pangolins, sometimes known as scaly anteaters, are mammals of the order Pholidota (). The one extant family, the Manidae, has three genera: '' Manis'', '' Phataginus'', and '' Smutsia''. ''Manis'' comprises four species found in Asia, while ' ...

s and hominina

The australopithecines (), formally Australopithecina or Hominina, are generally any species in the related genera of ''Australopithecus'' and ''Paranthropus''. It may also include members of ''Kenyanthropus'', ''Ardipithecus'', and '' Praeanth ...

n apes. Bipedalism is rarely found outside terrestrial animal

Terrestrial animals are animals that live predominantly or entirely on land (e.g. cats, chickens, ants, most spiders), as compared with aquatic animals, which live predominantly or entirely in the water (e.g. fish, lobsters, octopuses), ...

s—though at least two types of octopus

An octopus (: octopuses or octopodes) is a soft-bodied, eight-limbed mollusc of the order Octopoda (, ). The order consists of some 300 species and is grouped within the class Cephalopoda with squids, cuttlefish, and nautiloids. Like oth ...

walk bipedally on the sea floor using two of their arms, so they can use the remaining arms to camouflage themselves as a mat of algae or floating coconut.

There are no three-legged animals—though some macropods, such as kangaroos, that alternate between resting their weight on their muscular tails and their two hind legs could be looked at as an example of tripedal locomotion in animals.

quadrupedal

Quadrupedalism is a form of Animal locomotion, locomotion in which animals have four legs that are used to weight-bearing, bear weight and move around. An animal or machine that usually maintains a four-legged posture and moves using all four l ...

, walking or running on four legs. A few birds use quadrupedal movement in some circumstances. For example, the shoebill

The shoebill (''Balaeniceps rex''), also known as the whale-headed stork, and shoe-billed stork, is a large long-legged wading bird. It derives its name from its enormous shoe-shaped bill. It has a somewhat stork-like overall form and has pre ...

sometimes uses its wings to right itself after lunging at prey. The newly hatched hoatzin

The hoatzin ( ) or hoactzin ( ) (''Opisthocomus hoazin'') is a species of tropical bird found in swamps, riparian forests, and mangroves of the Amazon and the Orinoco basins in South America. It is the only extant species in the genus ''Opisthoco ...

bird has claws on its thumb and first finger enabling it to dexterously climb tree branches until its wings are strong enough for sustained flight. These claws are gone by the time the bird reaches adulthood.

A relatively few animals use five limbs for locomotion. Prehensile

Prehensility is the quality of an appendage or organ that has adapted for grasping or holding. The word is derived from the Latin term ''prehendere'', meaning "to grasp". The ability to grasp is likely derived from a number of different origin ...

quadrupeds may use their tail to assist in locomotion and when grazing, the kangaroos and other macropods use their tail to propel themselves forward with the four legs used to maintain balance.

Insects generally walk with six legs—though some insects such as nymphalid butterflies do not use the front legs for walking.

Arachnid

Arachnids are arthropods in the Class (biology), class Arachnida () of the subphylum Chelicerata. Arachnida includes, among others, spiders, scorpions, ticks, mites, pseudoscorpions, opiliones, harvestmen, Solifugae, camel spiders, Amblypygi, wh ...

s have eight legs. Most arachnids lack extensor

In anatomy, extension is a movement of a joint that increases the angle between two bones or body surfaces at a joint. Extension usually results in straightening of the bones or body surfaces involved. For example, extension is produced by extend ...

muscles in the distal

Standard anatomical terms of location are used to describe unambiguously the anatomy of humans and other animals. The terms, typically derived from Latin or Greek roots, describe something in its standard anatomical position. This position provi ...

joints of their appendages. Spiders and whipscorpions extend their limbs hydraulically using the pressure of their hemolymph

Hemolymph, or haemolymph, is a fluid, similar to the blood in invertebrates, that circulates in the inside of the arthropod's body, remaining in direct contact with the animal's tissues. It is composed of a fluid plasma in which hemolymph c ...

. Solifuge

Solifugae is an order of arachnids known variously as solifuges, sun spiders, camel spiders, and wind scorpions. The order includes more than 1,000 described species in about 147 genera. Despite the common names, they are neither true spiders (or ...

s and some harvestmen

The Opiliones (formerly Phalangida) are an Order (biology), order of arachnids,

Common name, colloquially known as harvestmen, harvesters, harvest spiders, or daddy longlegs (see below). , over 6,650 species of harvestmen have been discovered w ...

extend their knees by the use of highly elastic thickenings in the joint cuticle. Scorpion

Scorpions are predatory arachnids of the Order (biology), order Scorpiones. They have eight legs and are easily recognized by a pair of Chela (organ), grasping pincers and a narrow, segmented tail, often carried in a characteristic forward cur ...

s, pseudoscorpion

Pseudoscorpions, also known as false scorpions or book scorpions, are small, scorpion-like arachnids belonging to the order Pseudoscorpiones, also known as Pseudoscorpionida or Chelonethida.

Pseudoscorpions are generally beneficial to humans bec ...

s and some harvestmen have evolved muscles that extend two leg joints (the femur-patella and patella-tibia joints) at once.

The scorpion ''Hadrurus arizonensis

''Hadrurus arizonensis'', the giant desert hairy scorpion, giant hairy scorpion, or Arizona Desert hairy scorpion is a large scorpion found in North America.

Description

''H. arizonensis'' is the largest scorpion in North America, and one of th ...

'' walks by using two groups of legs (left 1, right 2, Left 3, Right 4 and Right 1, Left 2, Right 3, Left 4) in a reciprocating fashion. This alternating tetrapod coordination is used over all walking speeds.

Centipedes and millipedes have many sets of legs that move in metachronal rhythm

A metachronal rhythm or metachronal wave refers to wavy movements produced by the sequential action (as opposed to synchronized) of structures such as cilia, segments of worms, or legs. These movements produce the appearance of a travelling wave ...

. Some echinoderms locomote using the many tube feet

Tube or tubes may refer to:

* Tube (2003 film), ''Tube'' (2003 film), a 2003 Korean film

* "Tubes" (Peter Dale), performer on the Soccer AM#Tubes, Soccer AM television show

* Tube (band), a Japanese rock band

* Tube & Berger, the alias of dance/e ...

on the underside of their arms. Although the tube feet resemble suction cups in appearance, the gripping action is a function of adhesive chemicals rather than suction. Other chemicals and relaxation of the ampullae allow for release from the substrate. The tube feet latch on to surfaces and move in a wave, with one arm section attaching to the surface as another releases. Some multi-armed, fast-moving starfish such as the sunflower seastar (''Pycnopodia helianthoides'') pull themselves along with some of their arms while letting others trail behind. Other starfish turn up the tips of their arms while moving, which exposes the sensory tube feet and eyespot to external stimuli. Most starfish cannot move quickly, a typical speed being that of the leather star

The leather star (''Dermasterias imbricata'') is a starfish, sea star in the Family (biology), family Asteropseidae found at depths to off the western seaboard of North America. It was first species description, described to science by Adolph Ed ...

(''Dermasterias imbricata''), which can manage just in a minute. Some burrowing species from the genera ''Astropecten

''Astropecten'' is a genus of sea stars of the family Astropectinidae.

Identification

These sea stars are similar one to each other and it can be difficult to determine with certainty the species only from a photograph. To have a certain de ...

'' and ''Luidia

''Luidia'' is a genus of starfish in the family Luidiidae in which it is the only genus. Species of the family have a cosmopolitan distribution.

Characteristics

Members of the genus are characterised by having long arms with pointed tips frin ...

'' have points rather than suckers on their long tube feet and are capable of much more rapid motion, "gliding" across the ocean floor. The sand star (''Luidia foliolata

''Luidia foliolata'', the sand star, is a species of starfish in the family Luidiidae found in the northeastern Pacific Ocean on sandy and muddy seabeds at depths to about .

Description

The sand star has a small disc and five long, flattened ar ...

'') can travel at a speed of per minute. Sunflower starfish are quick, efficient hunters, moving at a speed of using 15,000 tube feet.

Many animals temporarily change the number of legs they use for locomotion in different circumstances. For example, many quadrupedal animals switch to bipedalism to reach low-level browse on trees. The genus of ''Basiliscus

Basiliscus (; died 476/477) was Eastern Roman emperor from 9 January 475 to August 476. He became in 464, under his brother-in-law, Emperor Leo I (457–474). Basiliscus commanded the army for an invasion of the Vandal Kingdom in 468, which ...

'' are arboreal lizards that usually use quadrupedalism in the trees. When frightened, they can drop to water below and run across the surface on their hind limbs at about 1.5 m/s for a distance of approximately before they sink to all fours and swim. They can also sustain themselves on all fours while "water-walking" to increase the distance travelled above the surface by about 1.3 m. When cockroaches run rapidly, they rear up on their two hind legs like bipedal humans; this allows them to run at speeds up to 50 body lengths per second, equivalent to a "couple hundred miles per hour, if you scale up to the size of humans." When grazing, kangaroos use a form of pentapedalism (four legs plus the tail) but switch to hopping (bipedalism) when they wish to move at a greater speed.

Powered cartwheeling

The Moroccan flic-flac spider (''Cebrennus rechenbergi

''Cebrennus rechenbergi'', also known as the Moroccan flic-flac spider and cartwheeling spider, is a species of huntsman spider indigenous to the sand dunes of the Erg Chebbi desert in Morocco. If provoked or threatened it can escape by doubling ...

'') uses a series of rapid, acrobatic flic-flac

Because ballet became formalized in France, a significant part of ballet terminology is in the French language.

A

À la seconde

() (Literally "to second") If a step is done "à la seconde", it is done to the side. 'Second position'. It can also ...

movements of its legs similar to those used by gymnasts, to actively propel itself off the ground, allowing it to move both down and uphill, even at a 40 percent incline. This behaviour is different than other huntsman spiders, such as '' Carparachne aureoflava'' from the Namib Desert

The Namib ( ; ) is a coastal desert in Southern Africa. According to the broadest definition, the Namib stretches for more than along the Atlantic coasts of Angola, Namibia, and northwest South Africa, extending southward from the Carunjamba Ri ...

, which uses passive cartwheeling

A cartwheel is a sideways rotary movement of the body. It is performed by bringing the hands to the floor one at a time while the body inverts. The legs travel over the body trunk while one or both hands are on the floor, and then the feet retu ...

as a form of locomotion. The flic-flac spider can reach speeds of up to 2 m/s using forward or back flips to evade threats.

Subterranean

Some animals move through solids such as soil by burrowing usingperistalsis

Peristalsis ( , ) is a type of intestinal motility, characterized by symmetry in biology#Radial symmetry, radially symmetrical contraction and relaxation of muscles that propagate in a wave down a tube, in an wikt:anterograde, anterograde dir ...

, as in earthworms

An earthworm is a soil-dwelling terrestrial animal, terrestrial invertebrate that belongs to the phylum Annelida. The term is the common name for the largest members of the class (biology), class (or subclass (biology), subclass, depending on ...

, or other methods. In loose solids such as sand some animals, such as the golden mole

Golden moles are small insectivorous burrowing mammals endemic to Sub-Saharan Africa. They comprise the family Chrysochloridae (the only family in the suborder Chrysochloridea) and as such they are taxonomically distinct from the true moles, f ...

, marsupial mole

Marsupial moles, the Notoryctidae family, are two species of highly specialized marsupial mammals that are found in the Australian interior.

They are small burrowing marsupials that anatomically converge on fossorial placental mammals, such as ...

, and the pink fairy armadillo

The pink fairy armadillo (''Chlamyphorus truncatus'') is the smallest species of armadillo, first described by Richard Harlan in 1825. The pink fairy armadillo is long, and typically weighs about . This solitary, desert-adapted animal is ende ...

, are able to move more rapidly, "swimming" through the loose substrate. Burrowing animals include moles, ground squirrels

Ground squirrels are rodents of the squirrel family (Sciuridae) that generally live on the ground or in burrows, rather than in trees like the tree squirrels. The term is most often used for the medium-sized ground squirrels, as the larger ones ar ...

, naked mole-rat

The naked mole-rat (''Heterocephalus glaber''), also known as the sand puppy, is a burrowing rodent native to the Horn of Africa and parts of Kenya, notably in Somali regions. It is closely related to the blesmols and is the only species in th ...

s, tilefish

file:Malacanthus latovittatus.jpg, 250px, Blue blanquillo, ''Malacanthus latovittatus''

Tilefishes are mostly small perciform marine fish comprising the family (biology), family Malacanthidae. They are usually found in sandy areas, especially n ...

, and mole cricket

Mole (or Molé) may refer to:

Animals

* Mole (animal) or "true mole"

* Golden mole, southern African mammals

* Marsupial mole, Australian mammals

Other common meanings

* Nevus, a growth on human skin

** Melanocytic nevus, a specific type of ...

s.

Arboreal locomotion

Arboreal locomotion is the locomotion of animals in trees. Some animals may only scale trees occasionally, while others are exclusively arboreal. These habitats pose numerous mechanical challenges to animals moving through them, leading to a variety of anatomical, behavioural and ecological consequences as well as variations throughout different species. Furthermore, many of these same principles may be applied to climbing without trees, such as on rock piles or mountains. The earliest knowntetrapod

A tetrapod (; from Ancient Greek :wiktionary:τετρα-#Ancient Greek, τετρα- ''(tetra-)'' 'four' and :wiktionary:πούς#Ancient Greek, πούς ''(poús)'' 'foot') is any four-Limb (anatomy), limbed vertebrate animal of the clade Tetr ...

with specializations that adapted it for climbing trees was ''Suminia

''Suminia'' is an extinct genus of basal anomodont that lived during the Tatarian age of the late Permian, spanning approximately from 268–252 Ma.Rybczynski N. 2000. Cranial anatomy and phylogenetic position of Suminia getmanovi, a basal anomod ...

'', a synapsid

Synapsida is a diverse group of tetrapod vertebrates that includes all mammals and their extinct relatives. It is one of the two major clades of the group Amniota, the other being the more diverse group Sauropsida (which includes all extant rept ...

of the late Permian

The Permian ( ) is a geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigraphic system which spans 47 million years, from the end of the Carboniferous Period million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Triassic Period 251.902 Mya. It is the s ...

, about 260 million years ago. Some invertebrate animals are exclusively arboreal in habitat, for example, the tree snail

Tree snail is a common name that is applied to various kinds of tropical air-breathing land snails, pulmonate gastropod mollusks that have shells, and that live in trees, in other words, are exclusively arboreal in habitat.

Some other species of ...

.

Brachiation

Brachiation (from "brachium", Latin for "arm"), or arm swinging, is a form of arboreal locomotion in which primates swing from tree limb to tree limb using only their arms. During brachiation, the body is alternately supported under each forelimb ...

(from ''brachium'', Latin for "arm") is a form of arboreal locomotion in which primates swing from tree limb to tree limb using only their arms. During brachiation, the body is alternately supported under each forelimb. This is the primary means of locomotion for the small gibbon

Gibbons () are apes in the family Hylobatidae (). The family historically contained one genus, but now is split into four extant genera and 20 species. Gibbons live in subtropical and tropical forests from eastern Bangladesh and Northeast Indi ...

s and siamang

The siamang (, ; ''Symphalangus syndactylus'') is an endangered arboreal, black-furred gibbon native to the forests of Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand. The largest of the gibbons, the siamang can be twice the size of other gibbons, reaching i ...

s of southeast Asia. Some New World monkeys such as spider monkeys and muriquis are "semibrachiators" and move through the trees with a combination of leaping and brachiation. Some New World species also practice suspensory behavior Suspensory behaviour is a form of arboreal locomotion or a feeding behavior that involves hanging or suspension of the body below or among tree branches. This behavior enables faster travel while reducing path lengths to cover more ground when trave ...

s by using their prehensile tail

A prehensile tail is the tail of an animal that has Adaptation (biology), adapted to grasp or hold objects. Fully Prehensility, prehensile tails can be used to hold and manipulate objects, and in particular to aid arboreal creatures in finding and ...

, which acts as a fifth grasping hand.

Pandas are known to swig their heads laterally as they ascend vertical surfaces astonishingly utilizing their head as a propulsive limb in an anatomical way that was thought to only be practiced by certain species of birds.

Energetics

Animal locomotion requiresenergy

Energy () is the physical quantity, quantitative physical property, property that is transferred to a physical body, body or to a physical system, recognizable in the performance of Work (thermodynamics), work and in the form of heat and l ...

to overcome various forces including friction

Friction is the force resisting the relative motion of solid surfaces, fluid layers, and material elements sliding against each other. Types of friction include dry, fluid, lubricated, skin, and internal -- an incomplete list. The study of t ...

, drag, inertia

Inertia is the natural tendency of objects in motion to stay in motion and objects at rest to stay at rest, unless a force causes the velocity to change. It is one of the fundamental principles in classical physics, and described by Isaac Newto ...

and gravity

In physics, gravity (), also known as gravitation or a gravitational interaction, is a fundamental interaction, a mutual attraction between all massive particles. On Earth, gravity takes a slightly different meaning: the observed force b ...

, although the influence of these depends on the circumstances. In terrestrial

Terrestrial refers to things related to land or the planet Earth, as opposed to extraterrestrial.

Terrestrial may also refer to:

* Terrestrial animal, an animal that lives on land opposed to living in water, or sometimes an animal that lives on o ...

environments, gravity must be overcome whereas the drag of air has little influence. In aqueous environments, friction (or drag) becomes the major energetic challenge with gravity being less of an influence. Remaining in the aqueous environment, animals with natural buoyancy

Buoyancy (), or upthrust, is the force exerted by a fluid opposing the weight of a partially or fully immersed object (which may be also be a parcel of fluid). In a column of fluid, pressure increases with depth as a result of the weight of t ...

expend little energy to maintain a vertical position in a water column. Others naturally sink, and must spend energy to remain afloat. Drag is also an energetic influence in flight

Flight or flying is the motion (physics), motion of an Physical object, object through an atmosphere, or through the vacuum of Outer space, space, without contacting any planetary surface. This can be achieved by generating aerodynamic lift ass ...

, and the aerodynamic

Aerodynamics () is the study of the motion of atmosphere of Earth, air, particularly when affected by a solid object, such as an airplane wing. It involves topics covered in the field of fluid dynamics and its subfield of gas dynamics, and is an ...

ally efficient body shapes of flying bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class (biology), class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the Oviparity, laying of Eggshell, hard-shelled eggs, a high Metabolism, metabolic rate, a fou ...

s indicate how they have evolved to cope with this. Limbless organisms moving on land must energetically overcome surface friction, however, they do not usually need to expend significant energy to counteract gravity.

Newton's third law of motion

Newton's laws of motion are three physical laws that describe the relationship between the motion of an object and the forces acting on it. These laws, which provide the basis for Newtonian mechanics, can be paraphrased as follows:

# A body r ...

is widely used in the study of animal locomotion: if at rest, to move forwards an animal must push backwards against something. Terrestrial animals must push the solid ground, swimming and flying animals must push against a fluid

In physics, a fluid is a liquid, gas, or other material that may continuously motion, move and Deformation (physics), deform (''flow'') under an applied shear stress, or external force. They have zero shear modulus, or, in simpler terms, are M ...

(either water

Water is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula . It is a transparent, tasteless, odorless, and Color of water, nearly colorless chemical substance. It is the main constituent of Earth's hydrosphere and the fluids of all known liv ...

or air

An atmosphere () is a layer of gases that envelop an astronomical object, held in place by the gravity of the object. A planet retains an atmosphere when the gravity is great and the temperature of the atmosphere is low. A stellar atmosph ...

). The effect of forces during locomotion on the design of the skeletal system is also important, as is the interaction between locomotion and muscle physiology, in determining how the structures and effectors of locomotion enable or limit animal movement. The energetics Energetics is the study of energy, and may refer to:

* Thermodynamics, branch of physics and chemistry that deals with energy, work and heat

* Bioenergetics, field in biochemistry that concerns energy flow through living systems and cells

* Energy ...

of locomotion involves the energy expenditure by animals in moving. Energy consumed in locomotion is not available for other efforts, so animals typically have evolved to use the minimum energy possible during movement. However, in the case of certain behaviors, such as locomotion to escape a predator, performance (such as speed or maneuverability) is more crucial, and such movements may be energetically expensive. Furthermore, animals may use energetically expensive methods of locomotion when environmental conditions (such as being within a burrow) preclude other modes.

The most common metric of energy use during locomotion is the net (also termed "incremental") cost of transport, defined as the amount of energy (e.g., Joules

The joule ( , or ; symbol: J) is the unit of energy in the International System of Units (SI). In terms of SI base units, one joule corresponds to one kilogram- metre squared per second squared One joule is equal to the amount of work don ...

) needed above baseline metabolic rate to move a given distance. For aerobic locomotion, most animals have a nearly constant cost of transport—moving a given distance requires the same caloric expenditure, regardless of speed. This constancy is usually accomplished by changes in gait

Gait is the pattern of Motion (physics), movement of the limb (anatomy), limbs of animals, including Gait (human), humans, during Animal locomotion, locomotion over a solid substrate. Most animals use a variety of gaits, selecting gait based on s ...

. The net cost of transport of swimming is lowest, followed by flight, with terrestrial limbed locomotion being the most expensive per unit distance. However, because of the speeds involved, flight requires the most energy per unit time. This does not mean that an animal that normally moves by running would be a more efficient swimmer; however, these comparisons assume an animal is specialized for that form of motion. Another consideration here is body mass

Human body weight is a person's mass or weight.

Strictly speaking, body weight is the measurement of mass without items located on the person. Practically though, body weight may be measured with clothes on, but without shoes or heavy accessori ...

—heavier animals, though using more total energy, require less energy ''per unit mass'' to move. Physiologists

Physiology (; ) is the scientific study of functions and mechanisms in a living system. As a subdiscipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ systems, individual organs, cells, and biomolecules carry out chemical and ...

generally measure energy use by the amount of oxygen

Oxygen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group (periodic table), group in the periodic table, a highly reactivity (chemistry), reactive nonmetal (chemistry), non ...

consumed, or the amount of carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . It is made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalent bond, covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in a gas state at room temperature and at norma ...

produced, in an animal's respiration

Respiration may refer to:

Biology

* Cellular respiration, the process in which nutrients are converted into useful energy in a cell

** Anaerobic respiration, cellular respiration without oxygen

** Maintenance respiration, the amount of cellul ...

. In terrestrial animals, the cost of transport is typically measured while they walk or run on a motorized treadmill, either wearing a mask to capture gas exchange or with the entire treadmill enclosed in a metabolic chamber. For small rodents

Rodents (from Latin , 'to gnaw') are mammals of the order Rodentia ( ), which are characterized by a single pair of continuously growing incisors in each of the upper and lower jaws. About 40% of all mammal species are rodents. They are n ...

, such as deer mice

''Peromyscus'' is a genus of rodents. They are commonly referred to as deer mice or deermice, not to be confused with the chevrotain or "mouse deer". They are New World mice only distantly related to the common house and laboratory mouse, ''M ...

, the cost of transport has also been measured during voluntary wheel running.

Energetics is important for explaining the evolution of foraging economic decisions in organisms; for example, a study of the African honey bee, ''A. m. scutellata'', has shown that honey bees may trade the high sucrose

Sucrose, a disaccharide, is a sugar composed of glucose and fructose subunits. It is produced naturally in plants and is the main constituent of white sugar. It has the molecular formula .

For human consumption, sucrose is extracted and refined ...

content of viscous nectar

Nectar is a viscous, sugar-rich liquid produced by Plant, plants in glands called nectaries, either within the flowers with which it attracts pollination, pollinating animals, or by extrafloral nectaries, which provide a nutrient source to an ...

off for the energetic benefits of warmer, less concentrated nectar, which also reduces their consumption and flight time.

Passive locomotion

Passive locomotion in animals is a type of mobility in which the animal depends on their environment for transportation; such animals are vagile but notmotile

Motility is the ability of an organism to move independently using metabolic energy. This biological concept encompasses movement at various levels, from whole organisms to cells and subcellular components.

Motility is observed in animals, mi ...

.

Hydrozoans

The

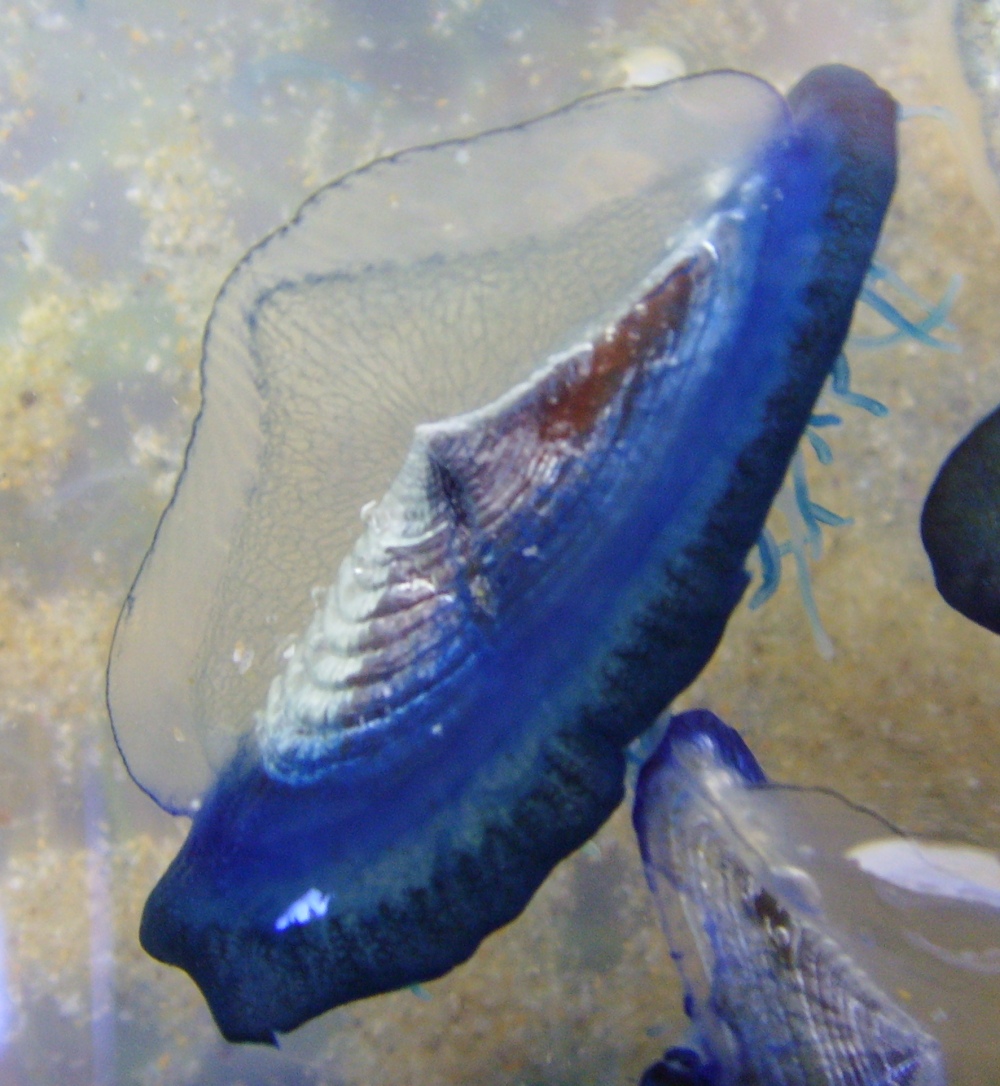

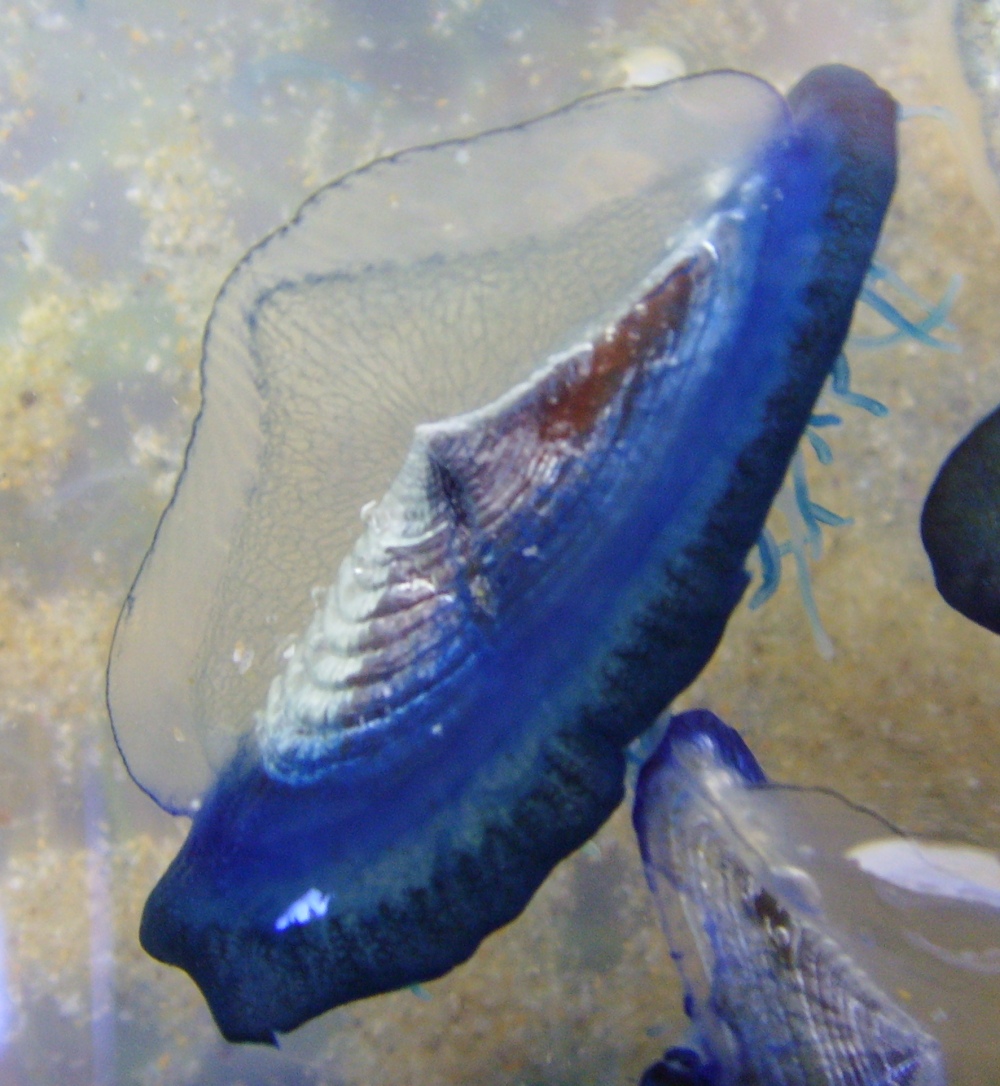

The Portuguese man o' war

The Portuguese war (''Physalia physalis''), also known as the man-of-war or bluebottle, is a marine hydrozoan found in the Atlantic Ocean and the Indian Ocean. It is the only species in the genus ''Physalia'', which in turn is the only genus in ...

(''Physalia physalis'') lives at the surface of the ocean. The gas-filled bladder, or pneumatophore (sometimes called a "sail"), remains at the surface, while the remainder is submerged. Because the Portuguese man o' war has no means of propulsion, it is moved by a combination of winds, currents, and tides. The sail is equipped with a siphon. In the event of a surface attack, the sail can be deflated, allowing the organism to briefly submerge.

Mollusca

The violet sea-snail (''Janthina janthina'') uses a buoyant foam raft stabilized byamphiphilic

In chemistry, an amphiphile (), or amphipath, is a chemical compound possessing both hydrophilic (''water-loving'', polar) and lipophilic (''fat-loving'', nonpolar) properties. Such a compound is called amphiphilic or amphipathic. Amphiphilic c ...

mucins

Mucins () are a family of high molecular weight, heavily glycosylation, glycosylated proteins (glycoconjugates) produced by epithelial tissues in most animals. Mucins' key characteristic is their ability to form gels; therefore they are a key com ...