Location Hypotheses Of Atlantis on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

There exist a variety of speculative proposals that real-world events could have inspired

There exist a variety of speculative proposals that real-world events could have inspired

Most proposals for the location of Atlantis center on the Mediterranean, influenced largely by the geographical location of

Most proposals for the location of Atlantis center on the Mediterranean, influenced largely by the geographical location of

The story of Atlantis has been argued since the early twentieth century to have preserved a cultural memory of the

The story of Atlantis has been argued since the early twentieth century to have preserved a cultural memory of the

"Geological framework of the Levant, Volume II: the Levantine Basin and Israel"

107 MB PDF version, Historical Productions-Hall, Jerusalem, Israel. 826 p. Additional PDF files of a related book and maps can be downloaded fro

/ref> in arguing that the closing of the Straits of Gibraltar; the

''Claimed Discovery of Atlantis Called 'Completely Bogus''

Live Science. Investigations by Dr. C. Hübscher of Geophysical Institute of

''ODP Leg 160 (Mediterranean I) Sites 963-973 ''

Proceedings Ocean Drilling Program Initial Reports no. 160. Ocean Drilling Program, Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas. For example, research conducted south of Cyprus as part of Leg 160 of the Ocean Drilling Project recovered from Sites 963, 965, and 966 cores of sediments underlying the bottom of the Mediterranean Sea at depths as shallow as 470, 1506, and 1044 meters (1540, 4940, and 3420 ft) below sea level. Thus, these cores came from parts of sea bottom of the eastern Mediterranean Sea that either lie above or at the depth of Sarmast's Atlantis, which lies at depths between below mean sea level. These cores provide a detailed and continuous record of sea level that demonstrates that for millions of years at least during the entire

The

The

It has been thought that when Plato wrote of the ''Sea of Atlantis'', he may have been speaking of the area now called the Atlantic Ocean. The ocean's name, derived from Greek mythology, means the "Sea of

It has been thought that when Plato wrote of the ''Sea of Atlantis'', he may have been speaking of the area now called the Atlantic Ocean. The ocean's name, derived from Greek mythology, means the "Sea of

The

The

In 1679

In 1679

Project Gutenbergalternative version

with commentary. *Plato, ''

Project Gutenbergalternative version

with commentary. {{DEFAULTSORT:Atlantis proposed locations Fringe theories Pseudohistory Pseudoarchaeology Pre-Columbian trans-oceanic contact

There exist a variety of speculative proposals that real-world events could have inspired

There exist a variety of speculative proposals that real-world events could have inspired Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

's fictional story of Atlantis

Atlantis () is a fictional island mentioned in Plato's works '' Timaeus'' and ''Critias'' as part of an allegory on the hubris of nations. In the story, Atlantis is described as a naval empire that ruled all Western parts of the known world ...

, told in the '' Timaeus'' and ''Critias

Critias (; , ''Kritias''; – 403 BC) was an ancient Athenian poet, philosopher and political leader. He is known today for being a student of Socrates, a writer of some regard, and for becoming the leader of the Thirty Tyrants, who ruled Athens ...

''. While Plato's story was not part of the Greek mythic tradition and his dialogues use it solely as an allegory

As a List of narrative techniques, literary device or artistic form, an allegory is a wikt:narrative, narrative or visual representation in which a character, place, or event can be interpreted to represent a meaning with moral or political signi ...

about hubris, speculation about real natural disasters that could have served as inspiration have been published in popular accounts and in a few academic contexts. Additionally, many works of pseudohistory

Pseudohistory is a form of pseudoscholarship that attempts to distort or misrepresent the historical record, often by employing methods resembling those used in scholarly historical research. The related term cryptohistory is applied to pseud ...

and pseudoarchaeology

Pseudoarchaeology (sometimes called fringe or alternative archaeology) consists of attempts to study, interpret, or teach about the subject-matter of archaeology while rejecting, ignoring, or misunderstanding the accepted Scientific method, data ...

treat the story as fact, offering reinterpretations that tie to national mysticism National mysticism (German: ''Nationalmystik'') or mystical nationalism is a form of nationalism that elevates the nation to the status of numen or divinity. Its best-known instance is Germanic mysticism, which gave rise to occultism under the Thir ...

or legends of ancient aliens

''Ancient Aliens'' is an American television series produced by Prometheus Entertainment that explores the pseudoscientific hypothesis of ancient astronauts in a non-critical, documentary format. Episodes also explore related pseudoscientific ...

. While Plato's story explicitly locates Atlantis in the Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions, with an area of about . It covers approximately 17% of Earth#Surface, Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the ...

beyond the Pillars of Hercules

The Pillars of Hercules are the promontory, promontories that flank the entrance to the Strait of Gibraltar. The northern Pillar, Calpe Mons, is the Rock of Gibraltar. A corresponding North African peak not being predominant, the identity of ...

, other proposed locations for Atlantis include Helike

Helike (; , pronounced , modern ) was an ancient Greek polis or city-state that was submerged by a tsunami in the winter of 373 BC.

It was located in the Regional units of Greece, regional unit of Achaea, northern Peloponnesos, two kilometres ( ...

, Thera

Santorini (, ), officially Thira (, ) or Thera, is a Greek island in the southern Aegean Sea, about southeast from the mainland. It is the largest island of a small, circular archipelago formed by the Santorini caldera. It is the southernmos ...

, Troy

Troy (/; ; ) or Ilion (; ) was an ancient city located in present-day Hisarlik, Turkey. It is best known as the setting for the Greek mythology, Greek myth of the Trojan War. The archaeological site is open to the public as a tourist destina ...

, and the North Pole

The North Pole, also known as the Geographic North Pole or Terrestrial North Pole, is the point in the Northern Hemisphere where the Earth's rotation, Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface. It is called the True North Pole to distingu ...

.

North-West of Egypt: From Greece to Spain

Most proposals for the location of Atlantis center on the Mediterranean, influenced largely by the geographical location of

Most proposals for the location of Atlantis center on the Mediterranean, influenced largely by the geographical location of Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

from which the story has literary antecedents.

Thera eruption

The story of Atlantis has been argued since the early twentieth century to have preserved a cultural memory of the

The story of Atlantis has been argued since the early twentieth century to have preserved a cultural memory of the Thera eruption

The Minoan eruption was a catastrophic volcanic eruption that devastated the Aegean island of Thera (also called Santorini) circa 1600 BCE. It destroyed the Minoan settlement at Akrotiri, as well as communities and agricultural areas on nea ...

, which destroyed the town of Akrotiri and affected some Minoan settlements on Crete

Crete ( ; , Modern Greek, Modern: , Ancient Greek, Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the List of islands by area, 88th largest island in the world and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fifth la ...

.

In mainland Greece

The classicist Robert L. Scranton argued in an article published in ''Archaeology

Archaeology or archeology is the study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of Artifact (archaeology), artifacts, architecture, biofact (archaeology), biofacts or ecofacts, ...

'' that Atlantis was the "Copaic drainage complex and its civilization" in Lake Copais

Lake Copais, also spelled Kopais or Kopaida (; ), was a lake in the centre of Boeotia, Greece, west of Thebes. It was first drained in the Bronze Age, and drained again in the late 19th century. It is now flat dry land and is still known as Kop ...

, Boeotia. Modern archaeological discoveries have revealed a Mycenaean-era drainage complex and subterranean channels in the lake.

Near Cyprus

An American architect, Robert Sarmast, claims that Atlantis lies at the bottom of the eastern Mediterranean within the Cyprus Basin.Sarmast, R., 2006, ''Discovery of Atlantis: The Startling Case for the Island of Cyprus''. Origin Press, San Rafael, California. 195 pp. In his book and on his web site, he argues that images prepared from sonar data of the sea bottom of the Cyprus Basin southeast ofCyprus

Cyprus (), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Situated in West Asia, its cultural identity and geopolitical orientation are overwhelmingly Southeast European. Cyprus is the List of isl ...

show features resembling man-made structures on it at depths of 1,500 meters. He interprets these features as being artificial structures that are part of the lost city of Atlantis as described by Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

. According to his ideas, several characteristics of Cyprus, including the presence of copper

Copper is a chemical element; it has symbol Cu (from Latin ) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkish-orang ...

and extinct Cyprus dwarf elephant

''Palaeoloxodon cypriotes'' is an extinct species of dwarf elephant that inhabited the island of Cyprus during the Late Pleistocene. A probable descendant of the large straight-tusked elephant of mainland Europe and West Asia, the species is amon ...

s and local place names and festivals (Kataklysmos), support his identification of Cyprus as once being part of Atlantis. As with many other proposals concerning the location of Atlantis, Sarmast speculates that its destruction by catastrophic flooding is reflected in the story of Noah's Flood in ''Genesis''.

In part, Sarmast bases his claim that Atlantis can be found offshore of Cyprus beneath of water on an abundance of evidence that the Mediterranean Sea dried up during the Messinian Salinity Crisis

In the Messinian salinity crisis (also referred to as the Messinian event, and in its latest stage as the Lago Mare event) the Mediterranean Sea went into a cycle of partial or nearly complete desiccation (drying-up) throughout the latter part of ...

when its level dropped by below the level of the Atlantic Ocean as the result of tectonic uplift blocking the inflow of water through the Strait of Gibraltar

Gibraltar ( , ) is a British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory and British overseas cities, city located at the southern tip of the Iberian Peninsula, on the Bay of Gibraltar, near the exit of the Mediterranean Sea into the A ...

. Separated from the Atlantic Ocean, the Mediterranean Sea either partly or completely dried up as the result of evaporation. As a result, its formerly submerged bottom turned into a desert with large saline and brackish lakes. This whole area was flooded when a ridge collapsed allowing the catastrophic flooding through the Straits of Gibraltar. However, Sarmast disagrees with mainstream geologists, oceanographers, and paleontologistsStanley, D.J., and F.-C. Wezel, 1985, "Geological Evolution of the Mediterranean Basin" Springer-Verlag, New York. 589 p. Hall, J.K., V.A. Krasheninnikov, F. Hirsch, C. Benjamini, and C. Flexer, eds., 2005"Geological framework of the Levant, Volume II: the Levantine Basin and Israel"

107 MB PDF version, Historical Productions-Hall, Jerusalem, Israel. 826 p. Additional PDF files of a related book and maps can be downloaded fro

/ref> in arguing that the closing of the Straits of Gibraltar; the

desiccation

Desiccation is the state of extreme dryness, or the process of extreme drying. A desiccant is a hygroscopic (attracts and holds water) substance that induces or sustains such a state in its local vicinity in a moderately sealed container. The ...

and subaerial exposure of the floor of the Mediterranean Sea; and its catastrophic flooding has occurred "forty times or more times in its long and turbulent existence" and that "the age of each of these events is unknown." In the same interview, he also contradicts what mainstream geologists, oceanographers, and paleontologists argue in claiming that "Scientists know that roughly 18,000 years ago, there was not just one Mediterranean Sea, but three." However, he does not specify who these scientists are; nor does he cite peer-reviewed scientific literature that supports this claim.

Marine and other geologists, who have also studied the bottom of the Cyprus basin, and professional archaeologists completely disagree with his interpretations.Britt, R.R., 2004''Claimed Discovery of Atlantis Called 'Completely Bogus''

Live Science. Investigations by Dr. C. Hübscher of Geophysical Institute of

University of Hamburg

The University of Hamburg (, also referred to as UHH) is a public university, public research university in Hamburg, Germany. It was founded on 28 March 1919 by combining the previous General Lecture System ('':de:Allgemeines Vorlesungswesen, ...

and others of the salt tectonics and mud volcanism within the Cyprus Basin, eastern Mediterranean Sea, demonstrated that the features which Sarmast interprets to be Atlantis consist only of a natural compressional fold caused by local salt tectonics and a slide scar with surficial compressional folds at the downslope end and sides of the slide. This research collaborates seismic data shown and discussed in the ''Atlantis: New Revelations 2-hour Special'' episode of '' Digging for the Truth'', a History Channel documentary television series. Using reflection seismology

Reflection seismology (or seismic reflection) is a method of exploration geophysics that uses the principles of seismology to estimate the properties of the Earth's subsurface from reflection (physics), reflected seismic waves. The method requir ...

, this documentary demonstrated techniques that what Sarmast interpreted to be artificial walls are natural tectonic landforms.

Furthermore, the interpretation of the age and stratigraphy of sediments blanketing the bottom of the Cyprus Basin from sea bottom cores containing Pleistocene and older marine sediments and thousands of kilometers of seismic lines from the Cyprus and adjacent basins clearly demonstrates that the Mediterranean Sea last dried up during the Messinian Salinity Crisis

In the Messinian salinity crisis (also referred to as the Messinian event, and in its latest stage as the Lago Mare event) the Mediterranean Sea went into a cycle of partial or nearly complete desiccation (drying-up) throughout the latter part of ...

between 5.59 and 5.33 million years ago.Emeis, K.-C., A.H.F. Robertson, C. Richter, and others, 1996''ODP Leg 160 (Mediterranean I) Sites 963-973 ''

Proceedings Ocean Drilling Program Initial Reports no. 160. Ocean Drilling Program, Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas. For example, research conducted south of Cyprus as part of Leg 160 of the Ocean Drilling Project recovered from Sites 963, 965, and 966 cores of sediments underlying the bottom of the Mediterranean Sea at depths as shallow as 470, 1506, and 1044 meters (1540, 4940, and 3420 ft) below sea level. Thus, these cores came from parts of sea bottom of the eastern Mediterranean Sea that either lie above or at the depth of Sarmast's Atlantis, which lies at depths between below mean sea level. These cores provide a detailed and continuous record of sea level that demonstrates that for millions of years at least during the entire

Pliocene

The Pliocene ( ; also Pleiocene) is the epoch (geology), epoch in the geologic time scale that extends from 5.33 to 2.58Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( ; referred to colloquially as the ''ice age, Ice Age'') is the geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was fin ...

, and Holocene

The Holocene () is the current geologic time scale, geological epoch, beginning approximately 11,700 years ago. It follows the Last Glacial Period, which concluded with the Holocene glacial retreat. The Holocene and the preceding Pleistocene to ...

epochs that the feature that Sarmast interprets to be Atlantis and its adjacent sea bottom were always submerged below sea level. Therefore, the entire Cyprus Basin, including the ridge where Sarmast claims that Atlantis is located, has been submerged beneath the Mediterranean Sea for millions of years. Since its formation, the sea bottom feature identified by Sarmast as "Atlantis" has always been submerged beneath over a kilometer of water.

Helike

A number of classical scholars have proposed that Plato's inspiration for the story came from the earthquake and tsunami which destroyedHelike

Helike (; , pronounced , modern ) was an ancient Greek polis or city-state that was submerged by a tsunami in the winter of 373 BC.

It was located in the Regional units of Greece, regional unit of Achaea, northern Peloponnesos, two kilometres ( ...

in 373 BC, just a few years before he wrote the relevant dialogues. The claim that Helike

Helike (; , pronounced , modern ) was an ancient Greek polis or city-state that was submerged by a tsunami in the winter of 373 BC.

It was located in the Regional units of Greece, regional unit of Achaea, northern Peloponnesos, two kilometres ( ...

is the inspiration for Plato's Atlantis is also supported by Dora Katsonopoulou and Steven Soter.

Sardinia

The concept of the identification of Atlantis with the island of Sardinia is the idea that the Italians were involved in theSea Peoples

The Sea Peoples were a group of tribes hypothesized to have attacked Ancient Egypt, Egypt and other Eastern Mediterranean regions around 1200 BC during the Late Bronze Age. The hypothesis was proposed by the 19th-century Egyptology, Egyptologis ...

movement (a similar story to Plato's account), that the name "Atlas" may have been derived from " Italos" via the Middle Egyptian language, and Plato's descriptions of the island and the city of Atlantis share several traits with Sardinia and its Bronze Age culture.

Luigi Usai has claimed Atlantis could be beneath Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; ; ) is the Mediterranean islands#By area, second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, and one of the Regions of Italy, twenty regions of Italy. It is located west of the Italian Peninsula, north of Tunisia an ...

and Corsica

Corsica ( , , ; ; ) is an island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the Regions of France, 18 regions of France. It is the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fourth-largest island in the Mediterranean and lies southeast of the Metro ...

. Atlantis would be the bathymetrically submerged island whose plateaus form what we know as the islands of Sardinia and Corsica outside the surface of the water. The capital would have its center on a hill near the small town of Santadi

Santadi is a ''comune'' (municipality) in the Province of South Sardinia in the Italy, Italian region Sardinia, located about southwest of Cagliari and about southeast of Carbonia, Italy, Carbonia.

Santadi borders the following municipalities: A ...

, in the province of Cagliari

Cagliari (, , ; ; ; Latin: ''Caralis'') is an Comune, Italian municipality and the capital and largest city of the island of Sardinia, an Regions of Italy#Autonomous regions with special statute, autonomous region of Italy. It has about 146,62 ...

. Starting from the hill next to Santadi, it's possible to see the perfectly circular development of all the town planning. He has also said there are also many toponymic references to the myth of Atlantis, including the two hot and cold water sources placed by Poseidon

Poseidon (; ) is one of the twelve Olympians in ancient Greek religion and mythology, presiding over the sea, storms, earthquakes and horses.Burkert 1985pp. 136–139 He was the protector of seafarers and the guardian of many Hellenic cit ...

: the cold water source of Zinnigas, which still remains today also in the name of the "Castello d'Acquafredda" di Siliqua

The siliqua (. siliquas or siliquae) is the modern namegiven without any ancient evidence to confirm the designationto small, thin, Roman silver coins produced in the 4th century and later. When the coins were in circulation, the Latin word wa ...

(Coldwater Castle), and the hot water source, present in the toponymy

Toponymy, toponymics, or toponomastics is the study of '' toponyms'' ( proper names of places, also known as place names and geographic names), including their origins, meanings, usage, and types. ''Toponym'' is the general term for a proper na ...

in three neighborhoods next to the small town of nuxis, still called " Acquacadda" (Hotwater), " S'Acqua Callenti de Susu" and " S'Acqua Callenti de Basciu" (Upper hotwater and Down hotwater), which are small villages next to Santadi

Santadi is a ''comune'' (municipality) in the Province of South Sardinia in the Italy, Italian region Sardinia, located about southwest of Cagliari and about southeast of Carbonia, Italy, Carbonia.

Santadi borders the following municipalities: A ...

.

Malta

Malta

Malta, officially the Republic of Malta, is an island country in Southern Europe located in the Mediterranean Sea, between Sicily and North Africa. It consists of an archipelago south of Italy, east of Tunisia, and north of Libya. The two ...

, being situated in the dividing line between the western and eastern Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern Eur ...

, and being home to some of the oldest man-made structures in the world, is considered a possible location of Atlantis both by some current researchers and by Maltese amateur enthusiasts.

In the 19th century, the antiquarian Giorgio Grognet de Vassé

Giorgio Grognet de Vassé (1774–1862) was a Maltese architect and antiquarian, who is mostly known for designing the Mosta Basilica, popularly known as the Rotunda of Mosta.

In the late 18th century, he studied at Frascati in the Papal States ...

published a short compendium arguing that Malta was the location of Atlantis. He was inspired by the discovery of the megalithic temples of Ġgantija

Ġgantija (; "place of giants") is a megalithic temple complex from the Neolithic era (–2500 BC), on the List of islands in the Mediterranean, Mediterranean island of Gozo in Malta. The Ġgantija temples are the earliest of the Megalithic Temp ...

and Ħaġar Qim

Ħaġar Qim (; "Standing/Worshipping Stones") is a megalithic temple complex found on the Mediterranean island of Malta, dating from the Ġgantija phase (3600–3200 BC). The Megalithic Temples of Malta are among the most ancient religio ...

during his lifetime.

In ''Malta fdal Atlantis'' (''Maltese remains of Atlantis'') (2002), Francis Galea writes about several older ideas, particularly that of Maltese architect Giorgio Grongnet, who in 1854 thought that the Maltese Islands are the remnants of Atlantis. However, in 1828, the same Giorgo Grongnet was involved in a scandal concerning forged findings which were intended to provide a "proof" for the claim that Malta was Atlantis.

North-East of Egypt: From Middle East to the Black Sea

Turkey

Peter James, in his book ''The Sunken Kingdom'', identifies Atlantis with the kingdom of Zippasla. He argues thatSolon

Solon (; ; BC) was an Archaic Greece#Athens, archaic History of Athens, Athenian statesman, lawmaker, political philosopher, and poet. He is one of the Seven Sages of Greece and credited with laying the foundations for Athenian democracy. ...

did indeed gather the story on his travels, but in Lydia

Lydia (; ) was an Iron Age Monarchy, kingdom situated in western Anatolia, in modern-day Turkey. Later, it became an important province of the Achaemenid Empire and then the Roman Empire. Its capital was Sardis.

At some point before 800 BC, ...

, not Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

as Plato states; that Atlantis is identical with Tantalis, the city of Tantalus

Tantalus ( ), also called Atys, was a Greek mythological figure, most famous for his punishment in Tartarus: for either revealing many secrets of the gods, for stealing ambrosia from them, or for trying to trick them into eating his son, he ...

in Asia Minor, which was (in a similar tradition known to the Greeks) said to have been destroyed by an earthquake; that the legend of Atlantis' conquests in the Mediterranean is based on the revolution by King Madduwattas of Zippasla against Hittite rule; that Zippasla is identical with Sipylus

Mount Spil (), the ancient Mount Sipylus () (elevation ), is a mountain rich in legends and history in Manisa Province, Turkey, in what used to be the heartland of the Lydians and what is now Turkey's Aegean Region.

Its summit towers over the m ...

, where Greek tradition placed Tantalis; and that the now vanished lake to the north of Mount Sipylus was the site of the city.

Troy

The geoarchaeologist Eberhard Zangger has proposed that Atlantis was in fact the city state ofTroy

Troy (/; ; ) or Ilion (; ) was an ancient city located in present-day Hisarlik, Turkey. It is best known as the setting for the Greek mythology, Greek myth of the Trojan War. The archaeological site is open to the public as a tourist destina ...

. He both agrees and disagrees with Rainer W. Kühne: He too believes that the Trojans-Atlanteans were the sea peoples, but only a minor part of them. He proposes that all Greek speaking city states of the Aegean civilization

Aegean civilization is a general term for the Bronze Age civilizations of Greece around the Aegean Sea. There are three distinct but communicating and interacting geographic regions covered by this term: Crete, the Cyclades and the Greek mainlan ...

or Mycenae

Mycenae ( ; ; or , ''Mykē̂nai'' or ''Mykḗnē'') is an archaeological site near Mykines, Greece, Mykines in Argolis, north-eastern Peloponnese, Greece. It is located about south-west of Athens; north of Argos, Peloponnese, Argos; and sou ...

constituted the sea peoples and that they destroyed each other's economies in a series of semi-fratricidal wars lasting several decades.

Black Sea

German researchers Siegfried and Christian Schoppe locate Atlantis in theBlack Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal sea, marginal Mediterranean sea (oceanography), mediterranean sea lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bound ...

. Before 5500 BC, a great plain lay in the northwest at a former freshwater-lake. In 5510 BC, rising sea level topped the barrier at today's Bosporus

The Bosporus or Bosphorus Strait ( ; , colloquially ) is a natural strait and an internationally significant waterway located in Istanbul, Turkey. The Bosporus connects the Black Sea to the Sea of Marmara and forms one of the continental bo ...

. They identify the Pillars of Hercules

The Pillars of Hercules are the promontory, promontories that flank the entrance to the Strait of Gibraltar. The northern Pillar, Calpe Mons, is the Rock of Gibraltar. A corresponding North African peak not being predominant, the identity of ...

with the Strait of Bosporus

The Bosporus or Bosphorus Strait ( ; , colloquially ) is a natural strait and an internationally significant waterway located in Istanbul, Turkey. The Bosporus connects the Black Sea to the Sea of Marmara and forms one of the continental bo ...

. They gave no explanation how the ships of the merchants coming from all over the world had arrived at the harbour of Atlantis when it was 350 feet below global sea-level.

They claim Oreichalcos means the obsidian

Obsidian ( ) is a naturally occurring volcanic glass formed when lava extrusive rock, extruded from a volcano cools rapidly with minimal crystal growth. It is an igneous rock. Produced from felsic lava, obsidian is rich in the lighter element ...

stone that used to be a cash equivalent at that time and was replaced by the spondylus

''Spondylus'' is a genus of bivalve molluscs, the only genus in the family Spondylidae and subfamily Spondylinae. They are known in English as spiny oysters or thorny oysters (although they are not, in fact, true oysters, but are related to sc ...

shell around 5500 BC, which would suit the red, white, black motif. The geocatastrophic event led to the Neolithic

The Neolithic or New Stone Age (from Ancient Greek, Greek 'new' and 'stone') is an archaeological period, the final division of the Stone Age in Mesopotamia, Asia, Europe and Africa (c. 10,000 BCE to c. 2,000 BCE). It saw the Neolithic Revo ...

diaspora in Europe, also beginning 5500 BC.

''The Great Atlantis Flood'', by Flying Eagle and Whispering Wind, locates Atlantis in the Sea of Azov

The Sea of Azov is an inland Continental shelf#Shelf seas, shelf sea in Eastern Europe connected to the Black Sea by the narrow (about ) Strait of Kerch, and sometimes regarded as a northern extension of the Black Sea. The sea is bounded by Ru ...

. These authors propose that the Dialogues of Plato present an accurate account of geological events, which occurred in 9,600 BC, in the Black Sea-Mediterranean Corridor. Glacial melt-waters, at the end of the Younger Dryas

The Younger Dryas (YD, Greenland Stadial GS-1) was a period in Earth's geologic history that occurred circa 12,900 to 11,700 years Before Present (BP). It is primarily known for the sudden or "abrupt" cooling in the Northern Hemisphere, when the ...

Ice Age caused a dramatic rise in the sea level of the Caspian Sea

The Caspian Sea is the world's largest inland body of water, described as the List of lakes by area, world's largest lake and usually referred to as a full-fledged sea. An endorheic basin, it lies between Europe and Asia: east of the Caucasus, ...

. An earthquake caused a fracture, which allowed the Caspian Sea to flood across the fertile plains of Atlantis. Simultaneously the earthquake caused the vast farmlands of Atlantis to sink, forming the present day Sea of Azov, the shallowest sea in the world.

Around Gibraltar: Near the Pillars of Hercules

Andalusia

Andalusia

Andalusia ( , ; , ) is the southernmost autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community in Peninsular Spain, located in the south of the Iberian Peninsula, in southwestern Europe. It is the most populous and the second-largest autonomou ...

is a region in modern-day southern Spain which once included the "lost" city of Tartessos

Tartessos () is, as defined by archaeological discoveries, a historical civilization settled in the southern Iberian Peninsula characterized by its mixture of local Prehistoric Iberia, Paleohispanic and Phoenician traits. It had a writing syste ...

, which disappeared in the 6th century BC. The Tartessians were traders known to the Ancient Greeks who knew of their legendary king Arganthonios

Arganthonios () was a king of ancient Tartessos (in Andalusia, southern Spain) who according to Herodotus, was visited by Colaeus, Kolaios of Samos. Given the legendary status of Geryon, Gargoris and Habis, Arganthonios is the earliest documente ...

. The proposal that Andalusia was Atlantis was originally developed by the Spanish author Juan de Mariana

Juan de Mariana (2 April 1536 – 17 February 1624), was a Spanish Jesuit priest, Scholastic, historian, and member of the Monarchomachs.

Life

Juan de Mariana was born in Talavera, Kingdom of Toledo. He studied at the Complutense University ...

and the Dutch author Johannes van Gorp (Johannes Goropius Becanus

Johannes Goropius Becanus (; 23 June 1519 – 28 June 1573), born Jan Gerartsen, was a Dutch physician, linguist, and humanist.

Life

He was born Jan Gerartsen van Gorp in the hamlet of Gorp, in the municipality of Hilvarenbeek. As was the fas ...

), both of the 16th century, later by José Pellicer de Ossau Salas y Tovar in 1673, who suggested that the metropolis of Atlantis was between the islands Mayor and Menor, located almost in the center of the Doñana Marshes, and expanded upon by Juan Fernández Amador y de los Ríos in 1919, who suggested that the metropolis of Atlantis was located precisely where today are the ' Marismas de Hinojo'. These claims were made again in 1922 by the German author Adolf Schulten

Adolf Schulten (27 May 1870 – 19 March 1960) was a German historian and archaeologist.

Schulten was born in Elberfeld, Rhine Province, and received a doctorate in geology from the University of Bonn in 1892. He studied in Italy, Africa an ...

, and further propagated by Otto Jessen, Richard Hennig, Victor Bérard

Victor Bérard (; Morez, 10 August 1864 – Paris, 13 November 1931) was a French diplomat and politician.

Today, he is still renowned for his works about Hellenistic studies and geography of the Odyssey

The locations mentioned in the narr ...

, and Elena Wishaw in the 1920s. The suggested locations in Andalusia lie outside the Pillars of Hercules, and therefore beyond but close to the Mediterranean itself.

In 2005, based upon the work of Adolf Schulten

Adolf Schulten (27 May 1870 – 19 March 1960) was a German historian and archaeologist.

Schulten was born in Elberfeld, Rhine Province, and received a doctorate in geology from the University of Bonn in 1892. He studied in Italy, Africa an ...

, the German teacher Werner Wickboldt also claimed this to be the location of Atlantis.Werner Wickboldt: Locating the capital of Atlantis by strict observation of the text by Plato. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on "The Atlantis Hypothesis: Searching for a Lost Land" (Milos island 2005) pp. 517-524 Wickboldt suggested that the war of the Atlanteans refers to the war of the Sea Peoples

The Sea Peoples were a group of tribes hypothesized to have attacked Ancient Egypt, Egypt and other Eastern Mediterranean regions around 1200 BC during the Late Bronze Age. The hypothesis was proposed by the 19th-century Egyptology, Egyptologis ...

who attacked the Eastern Mediterranean countries around 1200 BC and that the Iron Age

The Iron Age () is the final epoch of the three historical Metal Ages, after the Chalcolithic and Bronze Age. It has also been considered as the final age of the three-age division starting with prehistory (before recorded history) and progre ...

city of Tartessos may have been built at the site of the ruined Atlantis. In 2000, Georgeos Diaz-Montexano published an article arguing that Atlantis was located somewhere between Andalusia and Morocco.

An Andalusian location was also supported by Rainer Walter Kühne in his article that appeared in the journal ''Antiquity

Antiquity or Antiquities may refer to:

Historical objects or periods Artifacts

*Antiquities, objects or artifacts surviving from ancient cultures

Eras

Any period before the European Middle Ages (5th to 15th centuries) but still within the histo ...

''. "Kühne suggests that Plato has used three different historical elements for this tale. (i) Greek tradition on Mycenaean Athens for the description of ancient Athens, (ii) Egyptian records on the wars of the Sea Peoples for the description of the war of the Atlanteans, and (iii) oral tradition from Syracuse about Tartessos for the description of the city and geography of Atlantis." According to Wickboldt, Satellite image

Satellite images (also Earth observation imagery, spaceborne photography, or simply satellite photo) are images of Earth collected by imaging satellites operated by governments and businesses around the world. Satellite imaging companies sell i ...

s show two rectangular shapes on the tops of two small elevations inside the marsh of Doñana which he claims are the "temple of Poseidon

Poseidon (; ) is one of the twelve Olympians in ancient Greek religion and mythology, presiding over the sea, storms, earthquakes and horses.Burkert 1985pp. 136–139 He was the protector of seafarers and the guardian of many Hellenic cit ...

" and "the temple of Cleito and Poseidon".

On satellite images parts of several "rings" are recognizable, similar in their proportion with the ring system by Plato. It is not known if any of these shapes are natural or manmade and archaeological excavations are planned. Geologists have shown that the Doñana National Park

Doñana National Park or Parque Nacional y Natural de Doñana is a natural reserve in Andalusia, southern Spain, in the provinces of Huelva (most of its territory within the municipality of Almonte), Cádiz and Seville. It covers , of which are ...

experienced intense erosion from 4000 BC until the 9th century AD, where it became a marine environment. For thousands of years until the Medieval Age, all that occupied the area of the modern Marshes Doñana was a gulf or inland sea-arm, but there was not even a small island with sufficient space to house a small village.

Spartel Bank

Two proposals have put Spartel Bank, a submerged former island in theStrait of Gibraltar

The Strait of Gibraltar is a narrow strait that connects the Atlantic Ocean to the Mediterranean Sea and separates Europe from Africa.

The two continents are separated by 7.7 nautical miles (14.2 kilometers, 8.9 miles) at its narrowest point. Fe ...

, as the location of Atlantis. The more well-known claim was proposed in a September 2001 issue of ''Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences'' by French geologist

A geologist is a scientist who studies the structure, composition, and History of Earth, history of Earth. Geologists incorporate techniques from physics, chemistry, biology, mathematics, and geography to perform research in the Field research, ...

Jacques Collina-Girard. The lesser-known proposal was first published by Spanish-Cuban investigator Georgeos Díaz-Montexano in an April 2000 issue of Spanish magazine ''Más Allá de la Ciencia'' (Beyond Science), and later in August 2001 issues of Spanish magazines ''El Museo'' (The Museum) and ''Año Cero'' (Year Zero). The origin of Collina-Girard's idea is disputed, with Díaz-Montexano claiming it as plagiarism of his own earlier proposal, and Collina-Girard denying any plagiarism. Both individuals claim the other's arguments are pseudoscience

Pseudoscience consists of statements, beliefs, or practices that claim to be both scientific and factual but are incompatible with the scientific method. Pseudoscience is often characterized by contradictory, exaggerated or unfalsifiable cl ...

.

Collina-Girard states that during the most recent Glacial Maximum of the Ice Age

An ice age is a long period of reduction in the temperature of Earth's surface and atmosphere, resulting in the presence or expansion of continental and polar ice sheets and alpine glaciers. Earth's climate alternates between ice ages, and g ...

sea level was 135 m below its current level, narrowing the Gibraltar Strait and creating a small half-enclosed sea measuring 70 km by 20 km between the Mediterranean and Atlantic Ocean. The Spartel Bank formed an archipelago in this small sea with the largest island measuring about 10 to 12 kilometers across. With rising ocean levels the island began to slowly shrink, but then at around 9400 BC (11,400 years ago) there was an accelerated sea level rise

The sea level has been rising from the end of the last ice age, which was around 20,000 years ago. Between 1901 and 2018, the average sea level rose by , with an increase of per year since the 1970s. This was faster than the sea level had e ...

of 4 meters per century known as Meltwater pulse 1A

Meltwater pulse 1A (MWP1a) is the name used by Quaternary geologists, paleoclimatologists, and oceanographers for a period of rapid post-glacial sea level rise, between 14,700 and 13,500 years ago, during which the global sea level rose betwee ...

, which drowned the top of the main island. The occurrence of a great earthquake and tsunami in this region, similar to the 1755 Lisbon earthquake (magnitude 8.5-9) was proposed by marine geophysicist Marc-Andrè Gutscher as offering a possible explanation for the described catastrophic destruction (reference — Gutscher, M.-A., 2005. Destruction of Atlantis by a great earthquake and tsunami? A geological analysis of the Spartel Bank hypothesis. Geology, v. 33, p. 685-688.). Collina-Girard proposes that the disappearance of this island was recorded in prehistoric Egyptian tradition for 5,000 years until it was written down by the first Egyptian scribes around 4000-3000 BC, and the story then subsequently inspired Plato to write a fictionalized version interpreted to illustrate his own principles.

A detailed review in the Bryn Mawr Classical Review

''Bryn Mawr Classical Review'' (''BMCR''), founded in 1990, is an open access journal that as of 2008 published reviews of scholarly work in the field of classical studies including classical archaeology. The journal describes itself as the sec ...

comments on the discrepancies in Collina-Girard's dates and use of coincidences, concluding that he "has certainly succeeded in throwing some light upon some momentous developments in human prehistory in the area west of Gibraltar. Just as certainly, however, he has not found Plato's Atlantis."

Northwest Africa

Morocco

According to Michael Hübner, Atlantis' core region was located in South-West Morocco at the Atlantic Ocean. In his papers, an approach to the analysis of Plato's dialogues Timaeus and Critias is described. By means of a hierarchical constraint satisfaction procedure, a variety of geographically relevant indications from Plato's accounts are used to infer the most probable location of Plato's ''Atlantis Nesos''. The outcome of this is theSouss-Massa

Souss-Massa () is one of the twelve regions of Morocco, regions of Morocco. It covers an area of 51,642 km² and had a population of 2,676,847 as of the 2014 Moroccan census. The capital of the region is Agadir.

Geography

Souss-Massa bord ...

plain in today's South-West Morocco. This plain is surrounded by the High Atlas, the Anti-Atlas, the Sea of Atlas ( Atlantis Thalassa, today's Atlantic Ocean). Because of this isolated position, Hübner argued, this plain was called ''Atlantis Nesos'', the Island of Atlas, by ancient Greeks before the Greek Dark Ages

The Greek Dark Ages ( 1180–800 BC) were earlier regarded as two continuous periods of Greek history: the Postpalatial Bronze Age (c. 1180–1050 BC) and the Prehistoric Iron Age or Early Iron Age (c. 1050–800 BC). The last included all the ...

. The Amazigh

Berbers, or the Berber peoples, also known as Amazigh or Imazighen, are a diverse grouping of distinct ethnic groups indigenous to North Africa who predate the arrival of Arabs in the Maghreb. Their main connections are identified by their u ...

(Berber) people actually call the Souss-Massa plain ''island''. Of major archaeological interest is the fact that in the northwest of the Souss-Massa plain a large annular caldera-like geomorphologic structure was discovered. This structure has almost the dimensions of Plato's capital of Atlantis and is covered with hundreds of large and small prehistoric ruins of different types. These ruins were made out of rocks coloured red, white and black. Hübner also shows possible harbour remains, an unusually geomorphological structure, which applies to Plato's description of "roofed over docks, which were cut into red, white and black bedrock". These 'docks' are located close to the annular geomorphological structure and close to Cape Ghir, which was named Cape Heracles in antiquity. Hübner also argued that Agadir is etymologically related to the semitic ''g-d-r'' and probably to Plato's ''Gadir''. The semitic ''g-d-r'' means 'enclosure', ''

fortification' and 'sheep fold'. The meaning of 'enclosure', 'sheep fold' corresponds to the Greek translation of the name ''Gadeiros'' (Crit. 114b) which is ''Eumelos'' = 'rich in sheep'.

Richat Structure, Mauritania

The

The Richat Structure

The Richat Structure, or ''Guelb er Richât'' (, ), is a prominent circular geological feature in the Adrar Plateau of the Sahara

The Sahara (, ) is a desert spanning across North Africa. With an area of , it is the largest hot desert in ...

in Mauritania

Mauritania, officially the Islamic Republic of Mauritania, is a sovereign country in Maghreb, Northwest Africa. It is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the west, Western Sahara to Mauritania–Western Sahara border, the north and northwest, ...

has also been proposed as the site of Atlantis. This structure is generally considered to be a deeply eroded domal structure that overlies a still-buried alkaline igneous intrusion

In geology, an igneous intrusion (or intrusive body or simply intrusion) is a body of intrusive igneous rock that forms by crystallization of magma slowly cooling below the surface of the Earth. Intrusions have a wide variety of forms and com ...

. From 1974 onward, prehistoric artifacts of the area were mapped, finding an absence of prehistoric artifacts or Paleolithic or Neolithic stone tools from the structure's innermost depressions. Neither recognizable midden deposits nor manmade structures were found in the area, thus concluding that the area was used only for short-term hunting and stone tool manufacturing during prehistoric times.

Atlantic Ocean: East

It has been thought that when Plato wrote of the ''Sea of Atlantis'', he may have been speaking of the area now called the Atlantic Ocean. The ocean's name, derived from Greek mythology, means the "Sea of

It has been thought that when Plato wrote of the ''Sea of Atlantis'', he may have been speaking of the area now called the Atlantic Ocean. The ocean's name, derived from Greek mythology, means the "Sea of Atlas

An atlas is a collection of maps; it is typically a bundle of world map, maps of Earth or of a continent or region of Earth. Advances in astronomy have also resulted in atlases of the celestial sphere or of other planets.

Atlases have traditio ...

". Plato remarked that, in describing the origins of Atlantis, this area was allotted to Poseidon. In Ancient Greek times the terms "Ocean" and "Atlas" both referred to the 'Giant Water' which surrounded the main landmass known at that time by the Greeks, which could be described as Eurafrasia (although this whole supercontinent was far from completely known to the Ancient Greeks), and thus this water mass was considered to be the 'end of the (known) world', for the same reason the name "Atlas" was given to the mountains near the Ocean, the Atlas Mountains

The Atlas Mountains are a mountain range in the Maghreb in North Africa. They separate the Sahara Desert from the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean; the name "Atlantic" is derived from the mountain range, which stretches around through M ...

, as they also denoted the 'end of the (known) world'.

Azores Islands

One of the suggested places for Atlantis is around theAzores Islands

The Azores ( , , ; , ), officially the Autonomous Region of the Azores (), is one of the two autonomous regions of Portugal (along with Madeira). It is an archipelago composed of nine volcanic islands in the Macaronesia region of the North Atlant ...

, a group of islands belonging to Portugal located about west of the Portuguese coast. Some people believe the islands could be the mountain tops of Atlantis. Ignatius L. Donnelly

Ignatius Loyola Donnelly (November 3, 1831 – January 1, 1901) was an American Congressman, populist writer, and pseudoscientist. He is known primarily now for his fringe theories concerning Atlantis, Catastrophism (especially the idea of ...

, an American congressman

A member of congress (MOC), also known as a congressman or congresswoman, is a person who has been appointed or elected and inducted into an official body called a congress, typically to represent a particular constituency in a legislature. The t ...

, was perhaps the first one to talk about this possible location in his book ''Atlantis: The Antediluvian World'' (1882). Ignatius L. Donnelly also makes a connection to the mythical Aztlán

Aztlán (from or romanized ''Aztlán'', ) is the ancestral home of the Aztec peoples. The word "Aztec" was derived from the Nahuatl a''ztecah'', meaning "people from Aztlán." Aztlán is mentioned in several ethnohistorical sources dating from t ...

.

Charles Schuchert

Charles Schuchert (July 3, 1858 – November 20, 1942) was an American invertebrate paleontologist who was a leader in the development of paleogeography, the study of the distribution of lands and seas in the geological past.

Biography

He was ...

, in a paper called "Atlantis and the permanency of the North Atlantic Ocean bottom" (1917), discussed a lecture by Pierre-Marie Termier

Pierre-Marie Termier (3 July 1859 – 23 October 1930) was a French geologist.

He was born in Lyon, in Rhône, France, the son of Joseph François Termier and Jeanne Mollard. At the age of 18 he entered the Polytechnic School, then the Paris S ...

in which Termier suggested "that the entire region north of the Azores and perhaps the very region of the Azores, of which they may be only the visible ruins, was very recently submerged", reporting evidence that an area of 40,000 sq. mi and possibly as large as 200,000 sq. mi. had sunk 10,000 feet below the surface of the Atlantic Ocean. Schuchert's conclusion was:

: (1) "that the Azores are volcanic islands and are not the remnants of a more or less large continental mass, for they are not composed of rocks seen on the continents";

: (2) "that the tachylytes dredged up from the Atlantic to the north of the Azores were in all probability formed where they are now, at the bottom of the ocean"; and

: (3) "that there are no known geologic data that prove or even help to prove the existence of Plato's Atlantis in historic times."

The Azores are steep-sided volcanic seamounts that drop rapidly 1000 meters (about 3300 feet) to a plateau. Cores taken from the plateau and other evidence shows that this area has been an undersea plateau for millions of years. Ancient indicators, i.e. relict beaches, marine deposits, and wave cut-terraces, of Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( ; referred to colloquially as the ''ice age, Ice Age'') is the geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was fin ...

shorelines and sea level show that the Azores Islands have not subsided to any significant degree. Instead, they demonstrate that some of these islands have actually risen during the Late and Middle Pleistocene. This is evidenced by relict, Pleistocene wave-cut platforms and beach sediments that now lie well above current sea level. For example, they have been found on Flores Island at elevations of 15–20, 35–45, ~100, and ~250 meters above current sea level.

Three tectonic plates intersect among the Azores, the so-called Azores triple junction

The Azores triple junction (ATJ) is a geologic triple junction where the boundaries of three tectonic plates intersect: the North American plate, the Eurasian plate and the African plate. This triple junction is located along the Mid-Atlanti ...

.

Canary Islands, Madeira and Cape Verde

The Canary Islands have been identified as remnants of Atlantis by numerous authors. For example, in 1803,Bory de Saint-Vincent

Jean-Baptiste Geneviève Marcellin Bory de Saint-Vincent was a French naturalist, officer and politician. He was born on 6 July 1778 in Agen (Lot-et-Garonne) and died on 22 December 1846 in Paris. Biologist and geographer, he was particularly int ...

in his ''Essai sur les îles fortunées et l'antique Atlantide'' proposed that the Canary Islands

The Canary Islands (; ) or Canaries are an archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean and the southernmost Autonomous communities of Spain, Autonomous Community of Spain. They are located in the northwest of Africa, with the closest point to the cont ...

, along with the Madeira

Madeira ( ; ), officially the Autonomous Region of Madeira (), is an autonomous Regions of Portugal, autonomous region of Portugal. It is an archipelago situated in the North Atlantic Ocean, in the region of Macaronesia, just under north of ...

, and Azores

The Azores ( , , ; , ), officially the Autonomous Region of the Azores (), is one of the two autonomous regions of Portugal (along with Madeira). It is an archipelago composed of nine volcanic islands in the Macaronesia region of the North Atl ...

, are what remained after Atlantis broke up. Many later authors, i.e. Lewis Spence

James Lewis Thomas Chalmers Spence (25 November 1874 – 3 March 1955) was a Scottish journalist, poet, author, folklorist and occult scholar. Spence was a Fellow of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, and vice- ...

in his ''The Problem of Atlantis'', also identified the Canary Islands as part of Atlantis left over from when it sank.

Detailed geomorphic and geologic studies of the Canary Islands clearly demonstrate that over the last 4 million years, they have been steadily uplifted, without any significant periods of subsidence, by geologic processes such as erosional unloading, gravitational unloading, lithospheric flexure induced by adjacent islands, and volcanic underplating. For example, Pliocene

The Pliocene ( ; also Pleiocene) is the epoch (geology), epoch in the geologic time scale that extends from 5.33 to 2.58pillow lava

Pillow lavas are lavas that contain characteristic pillow-shaped structures that are attributed to the extrusion of the lava underwater, or ''subaqueous extrusion''. Pillow lavas in volcanic rock are characterized by thick sequences of discontinu ...

s, which solidified underwater and now exposed on the northeast flanks of Gran Canaria

Gran Canaria (, ; ), also Grand Canary Island, is the third-largest and second-most-populous island of the Canary Islands, a Spain, Spanish archipelago off the Atlantic coast of Northwest Africa. the island had a population of that constitut ...

, have been uplifted between 46 and 143 meters above sea level. Also, marine deposits associated with lavas dated as being 4.1 and 9.3 million years old in Gran Canaria, ca. 4.8 million years old in Fuerteventura

Fuerteventura () is one of the Canary Islands, in the Atlantic Ocean, geographically part of Macaronesia, and politically part of Spain. It is located away from the coast of North Africa. The island was declared a biosphere reserve by UNESCO i ...

, and ca. 9.8 million years old in Lanzarote

Lanzarote (, , ) is a Spanish island, the easternmost of the Canary Islands, off the north coast of Africa and from the Iberian Peninsula.

Covering , Lanzarote is the fourth-largest of the islands in the archipelago. With 163,230 inhabi ...

demonstrate that the Canary Islands have for millions of years undergone long term uplift without any significant, much less catastrophic, subsidence. A series of raised, Pleistocene marine terrace

A raised beach, coastal terrace,Pinter, N (2010): 'Coastal Terraces, Sealevel, and Active Tectonics' (educational exercise), from 2/04/2011or perched coastline is a relatively flat, horizontal or gently inclined surface of marine origin,Pir ...

s, which become progressively older with increasing elevation, on Fuerteventura indicate that it has risen in elevation at about 1.7 cm per thousand years for the past one million years. The elevation of the marine terrace for the highstand of sea level for the last interglacial period shows that this island has experienced neither subsidence nor significant uplift for the past 125,000 years. Within the Cape Verde Islands

Cape Verde or Cabo Verde, officially the Republic of Cabo Verde, is an island country and archipelagic state of West Africa in the central Atlantic Ocean, consisting of ten volcanic islands with a combined land area of about . These islands ...

, the detailed mapping and dating of 16 Pleistocene marine terraces and Pliocene marine conglomerate found that they have been uplifted throughout most of the Pleistocene and remained relatively stable without any significant subsidence since the last interglacial period. Finally, detailed studies of the sedimentary deposits surrounding the Canary Islands have demonstrated, except for a narrow rim around each island exposed during glacial

A glacier (; or ) is a persistent body of dense ice, a form of rock, that is constantly moving downhill under its own weight. A glacier forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its ablation over many years, often centuries. It acquires ...

lowstands of sea level, a complete lack of any evidence for the ocean floor surrounding the Canary Islands having ever been above water.Weaver, P.P.E., H.-U. Schmincke, J. V. Firth, and W. Duffield, eds., 1998, ''LEG 157—Scientific Results, Gran Canaria and Madeira Abyssal Plain Sites 950-956.'' Proceedings Ocean Drilling Project, Scientific Results. no. 157, College Station, Texas

Northern Spain

According to Jorge Maria Ribero-Meneses, Atlantis was in northern Spain. He specifically argues that Atlantis is theunderwater plateau

An oceanic or submarine plateau is a large, relatively flat elevation that is higher than the surrounding relief with one or more relatively steep sides.

There are 184 oceanic plateaus in the world, covering an area of or about 5.11% of the o ...

, known internationally as "Le Danois Bank" and locally as "The Cachucho". It is located about 25 kilometers from the continental shelf and about 60 km off the coast of Asturias, and Lastres between Ribadesella. Its top is now 425 meters below the sea. It is 50 kilometers from east to west and 18 km from north to south. Ribero-Meneses speculated that is part of the continental margin that broke off at least 12000 years ago as the result of tectonic processes that occurred at the end of the last ice age. He argues that they created a tsunami with waves with heights of hundreds of meters and that the few survivors had to start virtually from scratch.

Detailed studies of the geology of the Le Danois Bank region have refuted the proposal by Jorge Maria Ribero-Meneses that the Le Danois Bank was created by the collapse of the northern Cantabrian continental margin about 12,000 years ago. The Le Danois Bank represents part of the continental margin that have been uplifted by thrust faulting when the continental margin overrode oceanic crust during the Paleogene

The Paleogene Period ( ; also spelled Palaeogene or Palæogene) is a geologic period and system that spans 43 million years from the end of the Cretaceous Period Ma (million years ago) to the beginning of the Neogene Period Ma. It is the fir ...

and Neogene

The Neogene ( ,) is a geologic period and system that spans 20.45 million years from the end of the Paleogene Period million years ago ( Mya) to the beginning of the present Quaternary Period million years ago. It is the second period of th ...

periods. Along the northern edge of the Le Danois Bank, Precambrian

The Precambrian ( ; or pre-Cambrian, sometimes abbreviated pC, or Cryptozoic) is the earliest part of Earth's history, set before the current Phanerozoic Eon. The Precambrian is so named because it preceded the Cambrian, the first period of t ...

granulite

Granulites are a class of high-grade metamorphic rocks of the granulite facies that have experienced high-temperature and moderate-pressure metamorphism. They are medium to coarse–grained and mainly composed of feldspars sometimes associated ...

and Mesozoic

The Mesozoic Era is the Era (geology), era of Earth's Geologic time scale, geological history, lasting from about , comprising the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretaceous Period (geology), Periods. It is characterized by the dominance of archosaurian r ...

sedimentary rocks have been thrust northward over Miocene

The Miocene ( ) is the first epoch (geology), geological epoch of the Neogene Period and extends from about (Ma). The Miocene was named by Scottish geologist Charles Lyell; the name comes from the Greek words (', "less") and (', "new") and mea ...

and Oligocene

The Oligocene ( ) is a geologic epoch (geology), epoch of the Paleogene Geologic time scale, Period that extends from about 33.9 million to 23 million years before the present ( to ). As with other older geologic periods, the rock beds that defin ...

marine sediments. The basin separating the Le Danois Bank from the Cantabrian continental margin to the south is a graben

In geology, a graben () is a depression (geology), depressed block of the Crust (geology), crust of a planet or moon, bordered by parallel normal faults.

Etymology

''Graben'' is a loan word from German language, German, meaning 'ditch' or 't ...

that simultaneously formed as a result of normal faulting associated with the thrust faulting. In addition, marine sediment

Sediment is a solid material that is transported to a new location where it is deposited. It occurs naturally and, through the processes of weathering and erosion, is broken down and subsequently sediment transport, transported by the action of ...

s that range in age from lower Pliocene

The Pliocene ( ; also Pleiocene) is the epoch (geology), epoch in the geologic time scale that extends from 5.33 to 2.58Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( ; referred to colloquially as the ''ice age, Ice Age'') is the geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was fin ...

, cover large parts of Le Danois Bank, and fill the basin separating it from the Cantabrian continental margin demonstrate that this bank has been submerged beneath the Bay of Biscay for millions of years.

Atlantic Ocean: North

Irish Sea

In his book ''Atlantis of the West: The Case For Britain's Drowned Megalithic Civilization'' (2003), Paul Dunbavin argues that a large island once existed in theIrish Sea

The Irish Sea is a body of water that separates the islands of Ireland and Great Britain. It is linked to the Celtic Sea in the south by St George's Channel and to the Inner Seas off the West Coast of Scotland in the north by the North Ch ...

and that this island was Atlantis. He argues that this Neolithic civilization in Europe was partially drowned by rising sea levels caused by a comet

A comet is an icy, small Solar System body that warms and begins to release gases when passing close to the Sun, a process called outgassing. This produces an extended, gravitationally unbound atmosphere or Coma (cometary), coma surrounding ...

impact that caused a pole shift and changed the Earth's axis

In astronomy, axial tilt, also known as obliquity, is the angle between an object's rotational axis and its orbital axis, which is the line perpendicular to its orbital plane; equivalently, it is the angle between its equatorial plane and orbital ...

around 3100 BC. Such changes would be readily detectable to modern science, however, and Dunbavin's claims are considered pseudo-scientific at best within the scientific community.

Great Britain

William Comyns Beaumont

William Comyns Beaumont, also known as Comyns Beaumont and Appian Way (17 October 1873 – 30 December 1955),

Benny J Peise ...

believed that Great Britain was the location of Atlantis and the Scottish journalist Benny J Peise ...

Lewis Spence

James Lewis Thomas Chalmers Spence (25 November 1874 – 3 March 1955) was a Scottish journalist, poet, author, folklorist and occult scholar. Spence was a Fellow of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, and vice- ...

claimed that the ancient traditions of Britain and Ireland contain memories of Atlantis.

On December 29, 1997, the BBC reported that a team of Russian scientists believed they found Atlantis in the ocean 100 miles off of Land's End

Land's End ( or ''Pedn an Wlas'') is a headland and tourist and holiday complex in western Cornwall, England, United Kingdom, on the Penwith peninsula about west-south-west of Penzance at the western end of the A30 road. To the east of it is ...

, Cornwall

Cornwall (; or ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is also one of the Celtic nations and the homeland of the Cornish people. The county is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, ...

, Britain. The BBC stated that Little Sole Bank, a relatively shallow area, was believed by the team to be the capital of Atlantis. This may have been based on the myth of Lyonesse

Lyonesse ( /liːɒˈnɛs/ ''lee-uh-NESS'') is a kingdom which, according to legend, consisted of a long strand of land stretching from Land's End at the southwestern tip of Cornwall, England, to what is now the Isles of Scilly in the Celtic ...

.

Ireland

The idea of Atlantis being located in Ireland was presented in the book ''Atlantis from a Geographer's Perspective: Mapping the Fairy Land'' (2004) bySwedish

Swedish or ' may refer to:

Anything from or related to Sweden, a country in Northern Europe. Or, specifically:

* Swedish language, a North Germanic language spoken primarily in Sweden and Finland

** Swedish alphabet, the official alphabet used by ...

geographer

A geographer is a physical scientist, social scientist or humanist whose area of study is geography, the study of Earth's natural environment and human society, including how society and nature interacts. The Greek prefix "geo" means "earth" a ...

Dr. Ulf Erlingsson from Uppsala

Uppsala ( ; ; archaically spelled ''Upsala'') is the capital of Uppsala County and the List of urban areas in Sweden by population, fourth-largest city in Sweden, after Stockholm, Gothenburg, and Malmö. It had 177,074 inhabitants in 2019.

Loc ...

University. Erlingsson claimed that the empire of Atlantis refers to the Neolithic

The Neolithic or New Stone Age (from Ancient Greek, Greek 'new' and 'stone') is an archaeological period, the final division of the Stone Age in Mesopotamia, Asia, Europe and Africa (c. 10,000 BCE to c. 2,000 BCE). It saw the Neolithic Revo ...

Megalithic tomb

A megalith is a large stone that has been used to construct a prehistoric structure or monument, either alone or together with other stones. More than 35,000 megalithic structures have been identified across Europe, ranging geographically f ...

culture, based on their similar geographic extent, and deduced that the island of Atlantis then must correspond to Ireland.

North Sea

The

The North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Denmark, Norway, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France. A sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian Se ...

is known to contain lands that were once above water; the medieval town of Dunwich

Dunwich () is a village and civil parish in Suffolk, England. It is in the Suffolk & Essex Coast & Heaths National Landscape around north-east of London, south of Southwold and north of Leiston, on the North Sea coast.

In the Anglo-Saxon ...

in East Anglia

East Anglia is an area of the East of England, often defined as including the counties of Norfolk, Suffolk and Cambridgeshire, with parts of Essex sometimes also included.

The name derives from the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of the East Angles, ...

, for example, crumbled into the sea. The land area known as "Doggerland

Doggerland was a large area of land in Northern Europe, now submerged beneath the southern North Sea. This region was repeatedly exposed at various times during the Pleistocene epoch due to the lowering of sea levels during glacial periods. Howe ...

", between England and Denmark, was inundated by a tsunami

A tsunami ( ; from , ) is a series of waves in a water body caused by the displacement of a large volume of water, generally in an ocean or a large lake. Earthquakes, volcanic eruptions and underwater explosions (including detonations, ...

around 8200BP (6200BC), caused by a submarine landslide off the coast of Norway known as the Storegga Slide

The three Storegga Slides () are amongst the largest known submarine landslides. They occurred at the edge of Norway's continental shelf in the Norwegian Sea, approximately 6225–6170 BCE. The collapse involved an estimated length of coastal s ...

, and prehistoric human remains have been dredged up from the Dogger Bank

Dogger Bank ( Dutch: ''Doggersbank'', German: ''Doggerbank'', Danish: ''Doggerbanke'') is a large sandbank in a shallow area of the North Sea about off the east coast of England.

During the last ice age, the bank was part of a large landmass ...

. Atlantis itself has been identified besides Heligoland

Heligoland (; , ; Heligolandic Frisian: , , Mooring Frisian: , ) is a small archipelago in the North Sea. The islands were historically possessions of Denmark, then became possessions of the United Kingdom from 1807 to 1890. Since 1890, the ...

off the north-west German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany, the country of the Germans and German things

**Germania (Roman era)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizenship in Germany, see also Ge ...

coast by the author Jürgen Spanuth, who postulates that it was destroyed during the Bronze Age

The Bronze Age () was a historical period characterised principally by the use of bronze tools and the development of complex urban societies, as well as the adoption of writing in some areas. The Bronze Age is the middle principal period of ...

around 1200 BC, only to partially re-emerge during the Iron Age. Ulf Erlingsson believes that the island that sank referred to Dogger Bank, and the city itself referred to the Silverpit crater at the base of Dogger Bank. A book allegedly by Oera Linda claims that a land called Atland once existed in the North Sea, but was destroyed in 2194 BC.

Denmark

In his book ''The Celts: The People Who Came Out of the Darkness'' (1975), author Gerhard Herm links the origins of the Atlanteans to the end of the ice age and the flooding of eastern coastal Denmark.Finland

Finnish eccentricIor Bock

Ior Bock (; originally Bror Holger Svedlin; 17 January 1942 – 23 October 2010) was a Swedish-speaking Finnish tour guide, actor, mythologist and eccentric. Bock was a colourful media personality and became a very popular tour guide at the isl ...

located Atlantis in the Baltic sea, at southern part of Finland where he claimed a small community of people lived during the Ice Age

An ice age is a long period of reduction in the temperature of Earth's surface and atmosphere, resulting in the presence or expansion of continental and polar ice sheets and alpine glaciers. Earth's climate alternates between ice ages, and g ...

. According to Bock, this was possible due to Gulf Stream

The Gulf Stream is a warm and swift Atlantic ocean current that originates in the Gulf of Mexico and flows through the Straits of Florida and up the eastern coastline of the United States, then veers east near 36°N latitude (North Carolin ...

which brought warm water to the Finnish coast. This is a small part of a large "saga

Sagas are prose stories and histories, composed in Iceland and to a lesser extent elsewhere in Scandinavia.

The most famous saga-genre is the (sagas concerning Icelanders), which feature Viking voyages, migration to Iceland, and feuds between ...

" that he claimed had been told in his family through the ages, dating back to the development of language itself. The family saga

The family saga is a genre of literature which chronicles the lives and doings of a family or a number of related or interconnected families over a period of time. In novels (or sometimes sequences of novels) with a serious intent, this is often ...

tells the name Atlantis comes from Swedish words ''allt-land-is'' ("all-land-ice") and refers to the last Ice-Age. Thus in the Bock family saga it's more a time period than an exact geographical place. According to this the Atlantis disappeared in 8016 BC when the Ice-Age ended in Finland and the ice melted away.

Sweden

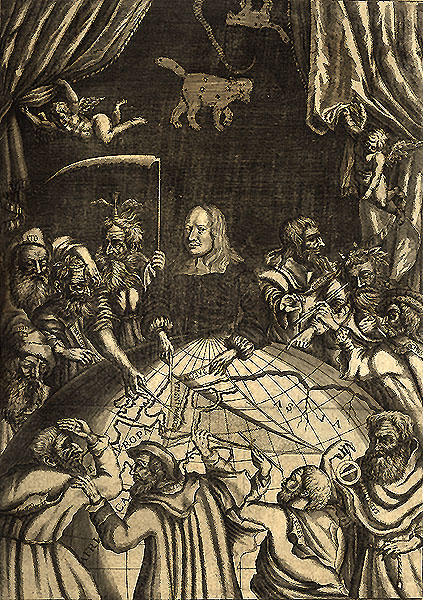

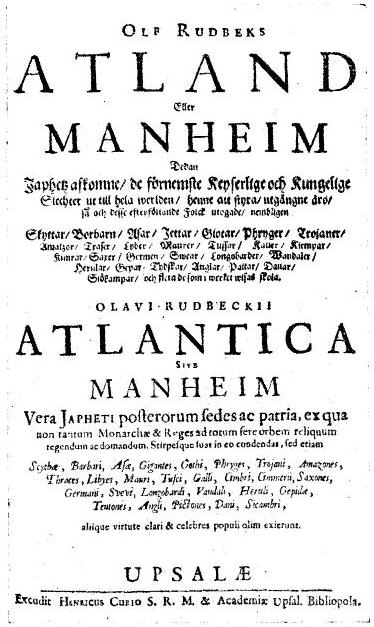

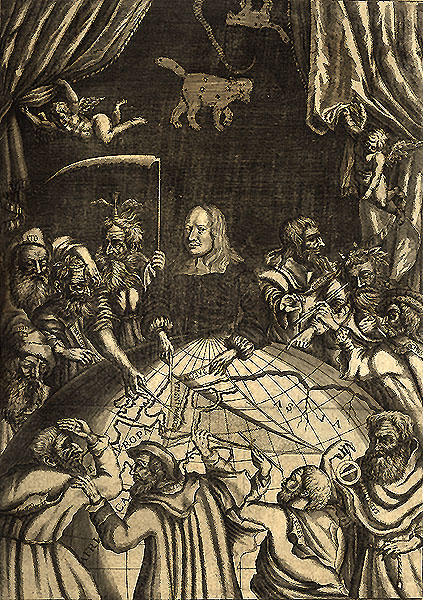

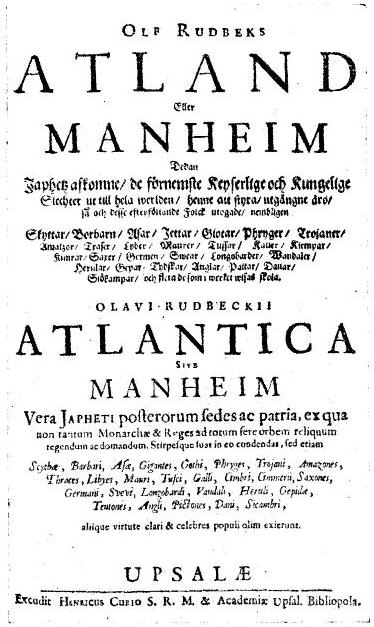

In 1679

In 1679 Olaus Rudbeck

Olaus Rudbeck (also known as Olof Rudbeck the Elder, to distinguish him from his son, and occasionally with the surname Latinized as ''Olaus Rudbeckius'') (13 September 1630 – 12 December 1702) was a Swedish scientist and writer, professor ...

wrote ''Atlantis'' (''Atlantica''), where he argues that Scandinavia, specifically Sweden, is identical with Atlantis. According to Rudbeck the capital city of Atlantis was identical to the ancient burial site of Swedish kings ''Gamla Uppsala

Gamla Uppsala (, ''Old Uppsala'') is a parish and a village outside Uppsala in Sweden. It had 17,973 inhabitants in 2016.

As early as the 3rd century AD and the 4th century AD and onwards, it was an important religious, economic and political c ...

''.

Americas

Until thediscovery of the New World

During the Age of Discovery, a large scale colonization of the Americas, involving a number of European countries, took place primarily between the late 15th century and the early 19th century. The Norse explored and colonized areas of Europe a ...

many scholars believed that Atlantis was either a metaphor for teaching philosophy, or just attributed the story to Plato without connecting the island with a real location. When Columbus returned from his voyage to the west historians began identifying the Americas with Atlantis. The first was Francisco López de Gómara

Francisco López de Gómara (February 2, 1511 – c. 1564) was a Spanish historian who worked in Seville, particularly noted for his works in which he described the early 16th century expedition undertaken by Hernán Cortés in the Spanish conqu ...

, who in 1552 thought that what Columbus had discovered was the Atlantic Island of Plato.

In 1556 Agustin de Zárate speculated that Atlantis once linked America and Europe and that it was as a result of Plato that the new continent was discovered. He also said it had all the attributes of the continent described by Plato yet at the same time mentioned that the ancient peoples crossed over by a route from the island of Atlantis. Zarate also mentions that the 9,000 "years" of Plato were 9,000 "months" (750 years).

This was also repeated and clarified by historian Pedro Sarmiento de Gamboa

Pedro Sarmiento de Gamboa (1532–1592) was a Spanish adventurer, author, historian, mathematician, and astronomer. He was named the governor of the Strait of Magellan by King Philip II of Spain, Philip II in 1580. His birthplace is not certain ...

in 1572 in his "History of the Incas", who by calculation of longitude stated that Atlantis must have stretched from within two leagues of the strait of Gibraltar westwards to include "all the rest of the land from the mouth of the Marañon (Amazon River) and Brazil to the South Sea, which is what they now call America." He thought the sunken part to be now in the Atlantic Ocean but that it was from this sunken part that the original Indians had come to populate Peru via one continuous land mass.

It first appeared as the Atlantic Island (Insula Atlantica) on a map of the New World by cartographer Sebastian Münster

Sebastian Münster (20 January 1488 – 26 May 1552) was a German cartographer and cosmographer. He also was a Christian Hebraist scholar who taught as a professor at the University of Basel. His well-known work, the highly accurate world map, ...

in 1540 and again on the map titled Atlantis Insula by Nicolas Sanson