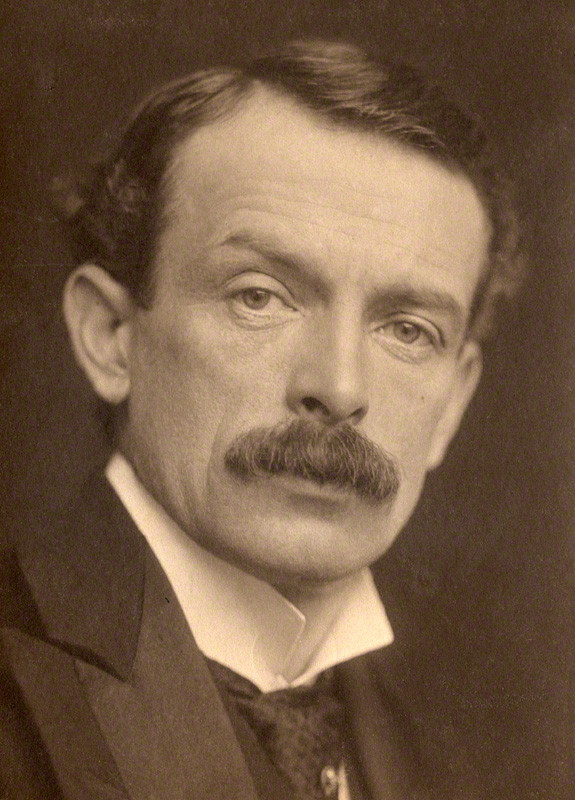

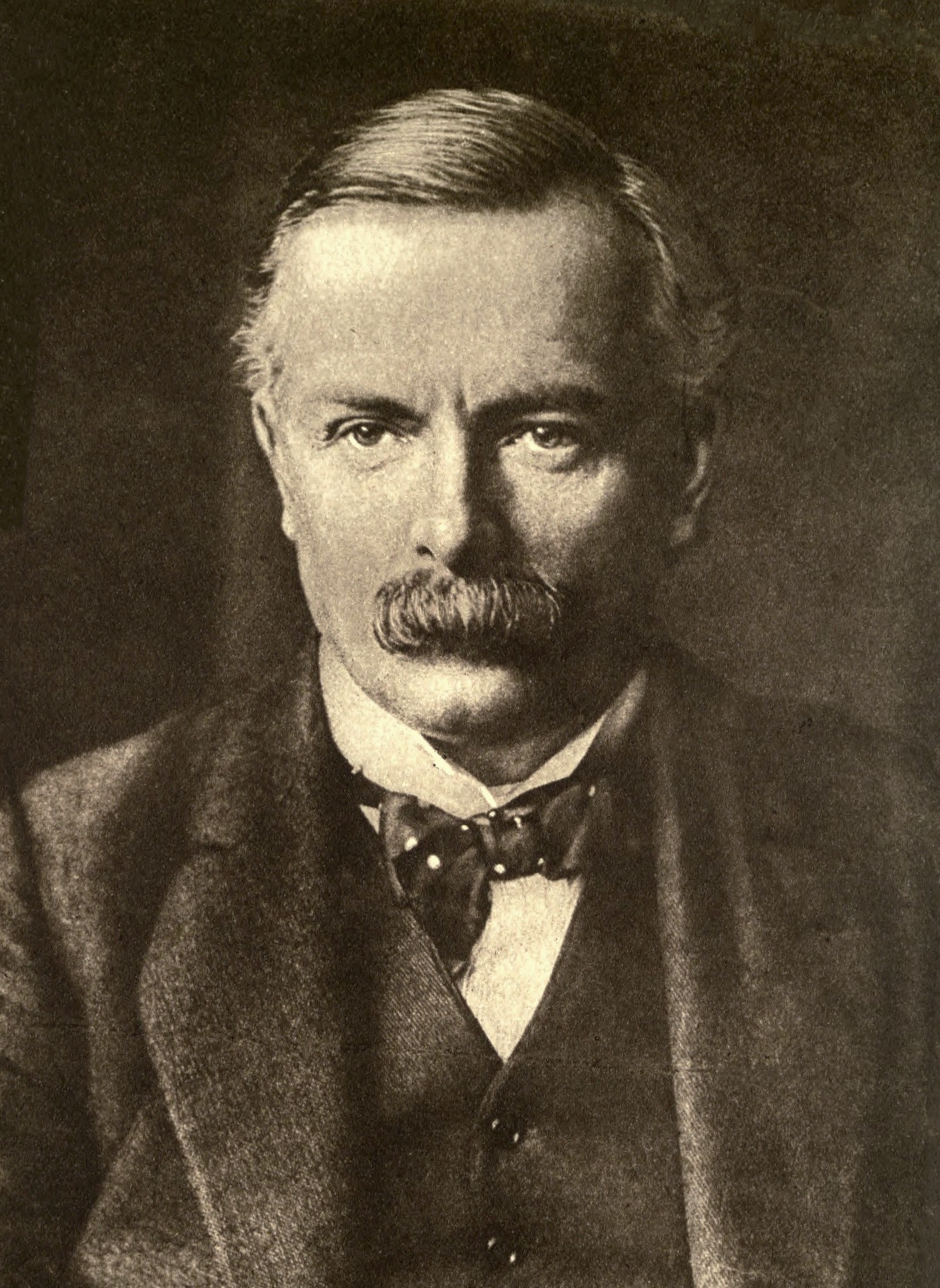

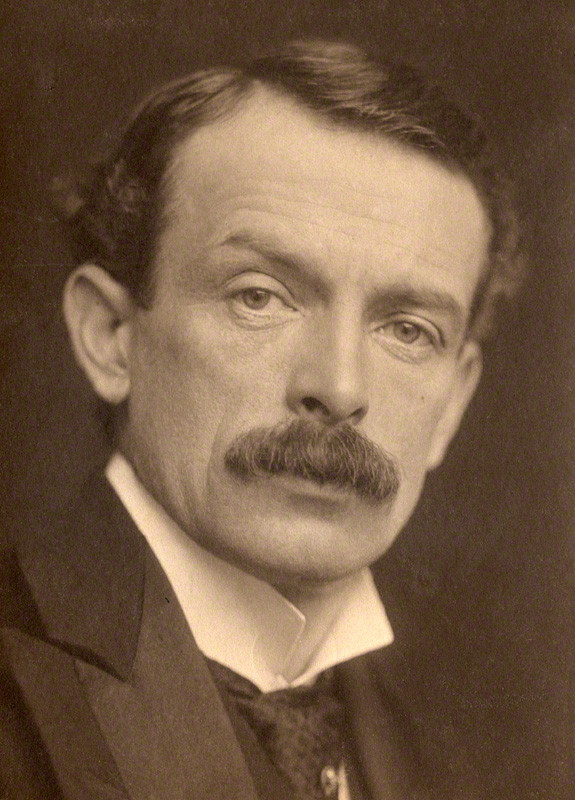

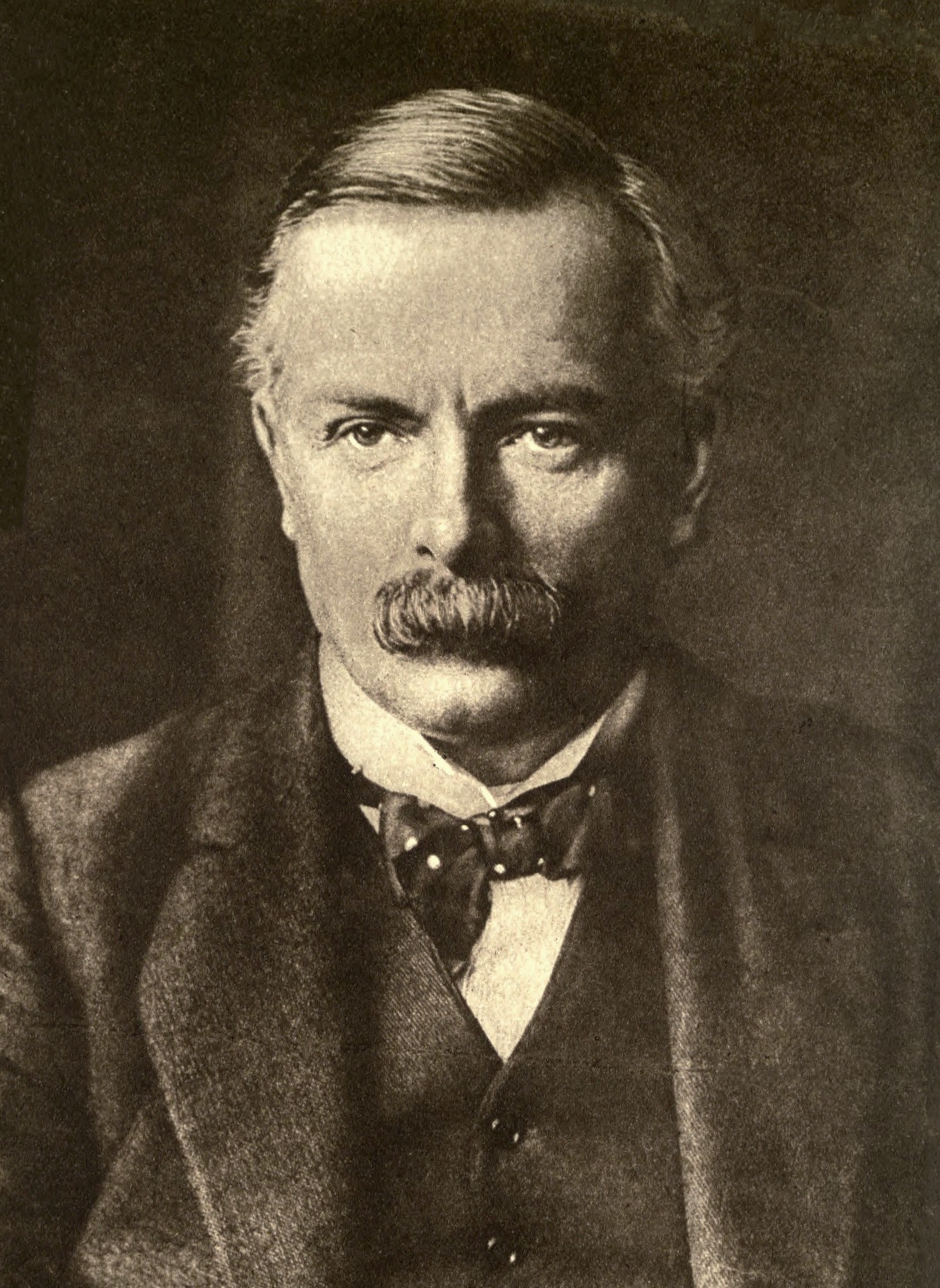

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was

Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister Advice (constitutional law), advises the Monarchy of the United Kingdom, sovereign on the exercise of much of the Royal prerogative ...

from 1916 to 1922. A

Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world.

The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left. For example, while the political systems ...

politician from Wales, he was known for leading the

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

during the

First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, for social-reform policies, for his role in the

Paris Peace Conference, and for negotiating the establishment of the

Irish Free State

The Irish Free State (6 December 192229 December 1937), also known by its Irish-language, Irish name ( , ), was a State (polity), state established in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. The treaty ended the three-ye ...

.

Born in

Chorlton-on-Medlock

Chorlton-on-Medlock is an inner city area of Manchester, England.

Historic counties of England, Historically in Lancashire, Chorlton-on-Medlock is bordered to the north by the River Medlock, which runs immediately south of Manchester city cen ...

, Manchester, and raised in

Llanystumdwy, Lloyd George gained a reputation as an orator and proponent of a Welsh blend of radical Liberal ideas that included support for

Welsh devolution

Welsh devolution is the Devolution in the United Kingdom, transfer of legislative powers for self-governance to Wales by the Parliament of the United Kingdom. The current system of devolution began following the enactment of the Government of Wa ...

, the

disestablishment of the Church of England in Wales, equality for labourers and tenant farmers, and reform of land ownership. He won

an 1890 by-election to become the Member of Parliament for

Caernarvon Boroughs, and was continuously re-elected to the role for 55 years. He served in

Henry Campbell-Bannerman's cabinet from 1905. After

H. H. Asquith

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith (12 September 1852 – 15 February 1928) was a British statesman and Liberal Party (UK), Liberal politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1908 to 1916. He was the last ...

succeeded to the premiership in 1908, Lloyd George replaced him as

Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and the head of HM Treasury, His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, t ...

. To fund extensive

welfare reforms, he proposed taxes on land ownership and high incomes in the 1909

People's Budget

The 1909/1910 People's Budget was a proposal of the Liberal government that introduced unprecedented taxes on the lands and incomes of Britain's wealthy to fund new social welfare programmes, such as non-contributary old age pensions under Ol ...

, which the

Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civiliza ...

-dominated

House of Lords

The House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the lower house, the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England. One of the oldest ext ...

rejected. The resulting

constitutional crisis

In political science, a constitutional crisis is a problem or conflict in the function of a government that the constitution, political constitution or other fundamental governing law is perceived to be unable to resolve. There are several variat ...

was only resolved after elections in 1910 and passage of the

Parliament Act 1911. His budget was enacted in 1910, with the

National Insurance Act 1911

The National Insurance Act 1911 (1 & 2 Geo. 5. c. 55) created National Insurance, originally a system of health insurance for industrial workers in Great Britain based on contributions from employers, the government, and the workers themselves. ...

and other measures helping to establish the modern

welfare state

A welfare state is a form of government in which the State (polity), state (or a well-established network of social institutions) protects and promotes the economic and social well-being of its citizens, based upon the principles of equal oppor ...

. He was embroiled in the 1913

Marconi scandal but remained in office and secured the disestablishment of the Church of England in Wales.

In 1915, Lloyd George became

Minister of Munitions

The Minister of Munitions was a British government position created during the First World War to oversee and co-ordinate the production and distribution of munitions for the war effort. The position was created in response to the Shell Crisis o ...

and expanded artillery shell production for the war. In 1916, he was appointed

Secretary of State for War

The secretary of state for war, commonly called the war secretary, was a secretary of state in the Government of the United Kingdom, which existed from 1794 to 1801 and from 1854 to 1964. The secretary of state for war headed the War Offic ...

but was frustrated by his limited power and clashes with Army commanders over strategy. Asquith proved ineffective as prime minister and was replaced by Lloyd George in December 1916. He centralised authority by creating a smaller

war cabinet. To combat food shortages caused by

u-boat

U-boats are Submarine#Military, naval submarines operated by Germany, including during the World War I, First and Second World Wars. The term is an Anglicization#Loanwords, anglicized form of the German word , a shortening of (), though the G ...

s, he implemented the convoy system, established rationing, and stimulated farming. After supporting the disastrous French

Nivelle Offensive in 1917, he had to reluctantly approve

Field Marshal Haig's plans for the

Battle of Passchendaele, which resulted in huge casualties with little strategic benefit. Against British military commanders, he was finally able to see the Allies brought under one command in March 1918. The war effort turned in Allied favour and was won in November. Following the December 1918

"Coupon" election, he and the Conservatives maintained their coalition with popular support.

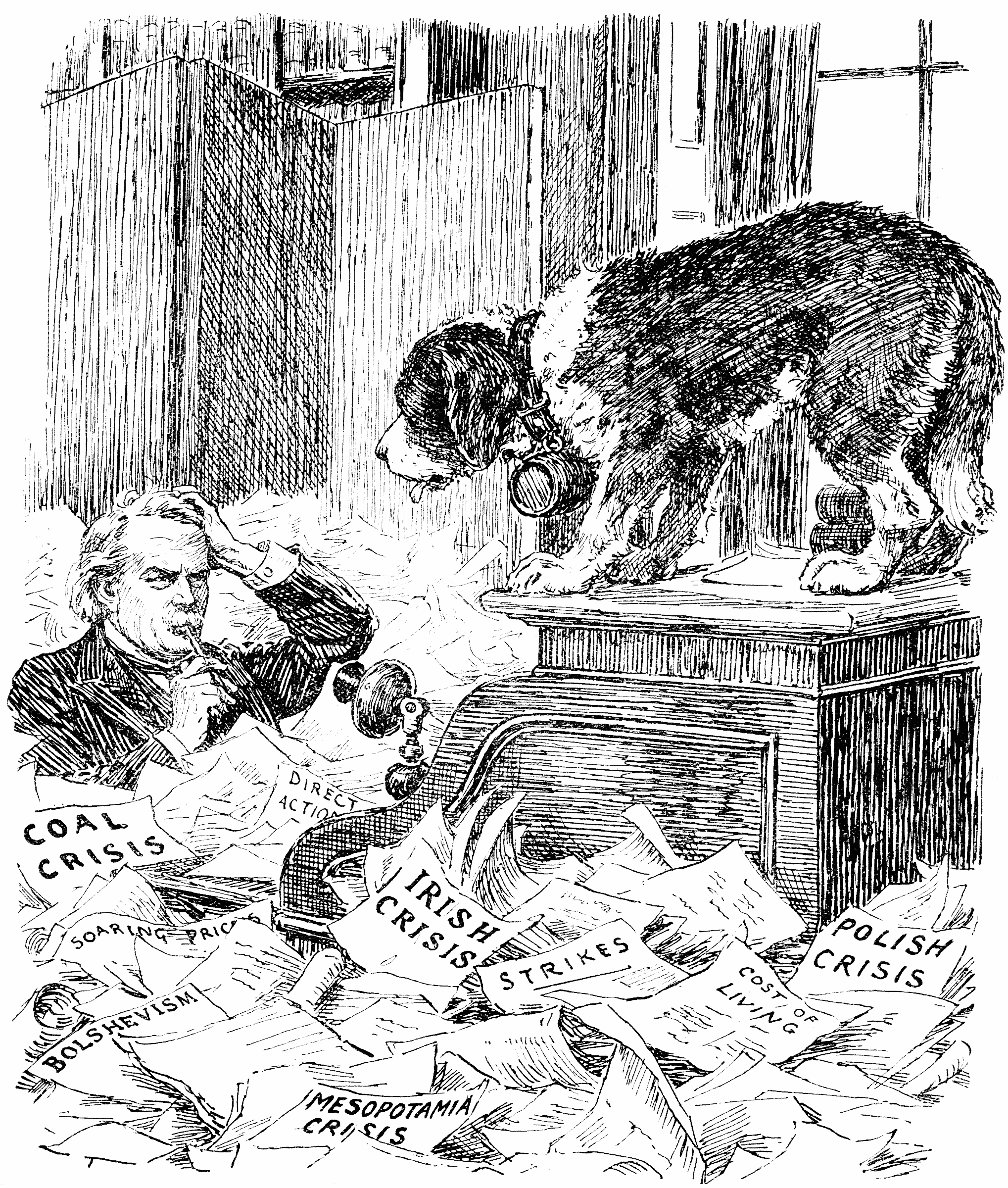

Lloyd George was a leading proponent at the

Paris Peace Conference of 1919, but the situation in Ireland worsened, erupting into the

Irish War of Independence

The Irish War of Independence (), also known as the Anglo-Irish War, was a guerrilla war fought in Ireland from 1919 to 1921 between the Irish Republican Army (1919–1922), Irish Republican Army (IRA, the army of the Irish Republic) and Unite ...

, which lasted until Lloyd George negotiated independence for the

Irish Free State

The Irish Free State (6 December 192229 December 1937), also known by its Irish-language, Irish name ( , ), was a State (polity), state established in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. The treaty ended the three-ye ...

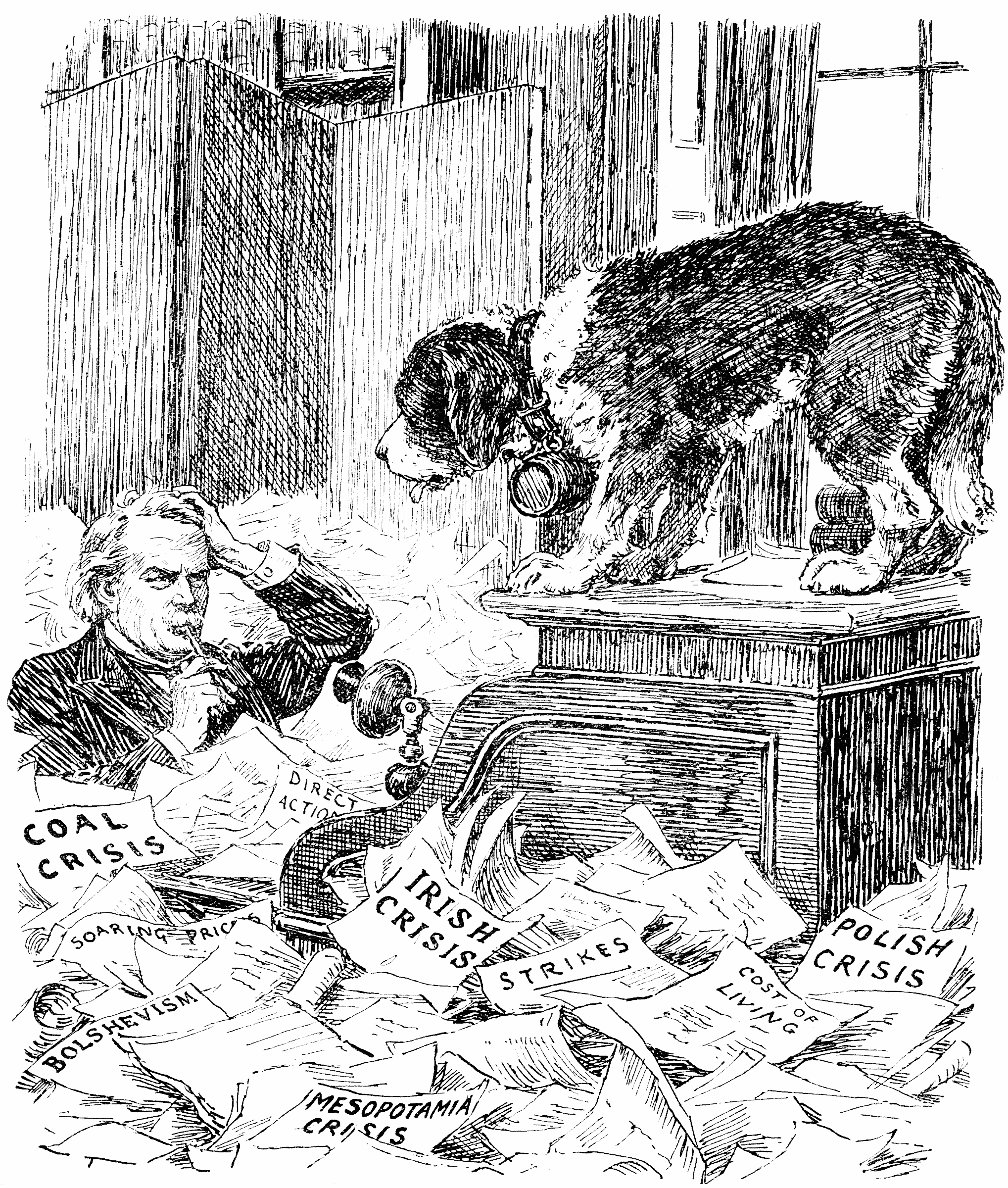

in 1921. At home, he initiated education and housing reforms, but trade-union militancy rose to record levels, the economy

became depressed in 1920 and unemployment rose;

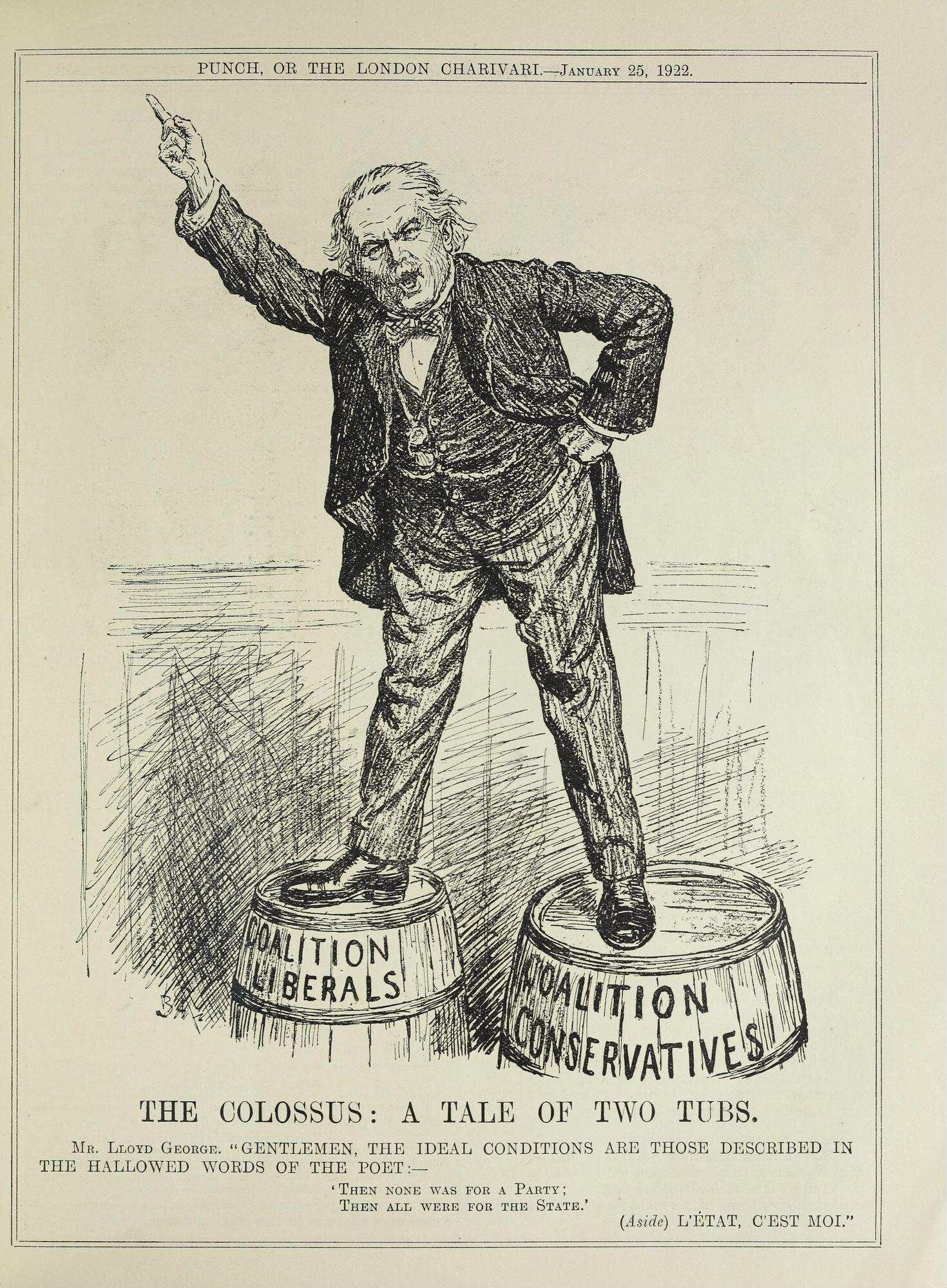

spending cuts followed in 1921–22, and in 1922 he became embroiled in a scandal over the sale of honours and the

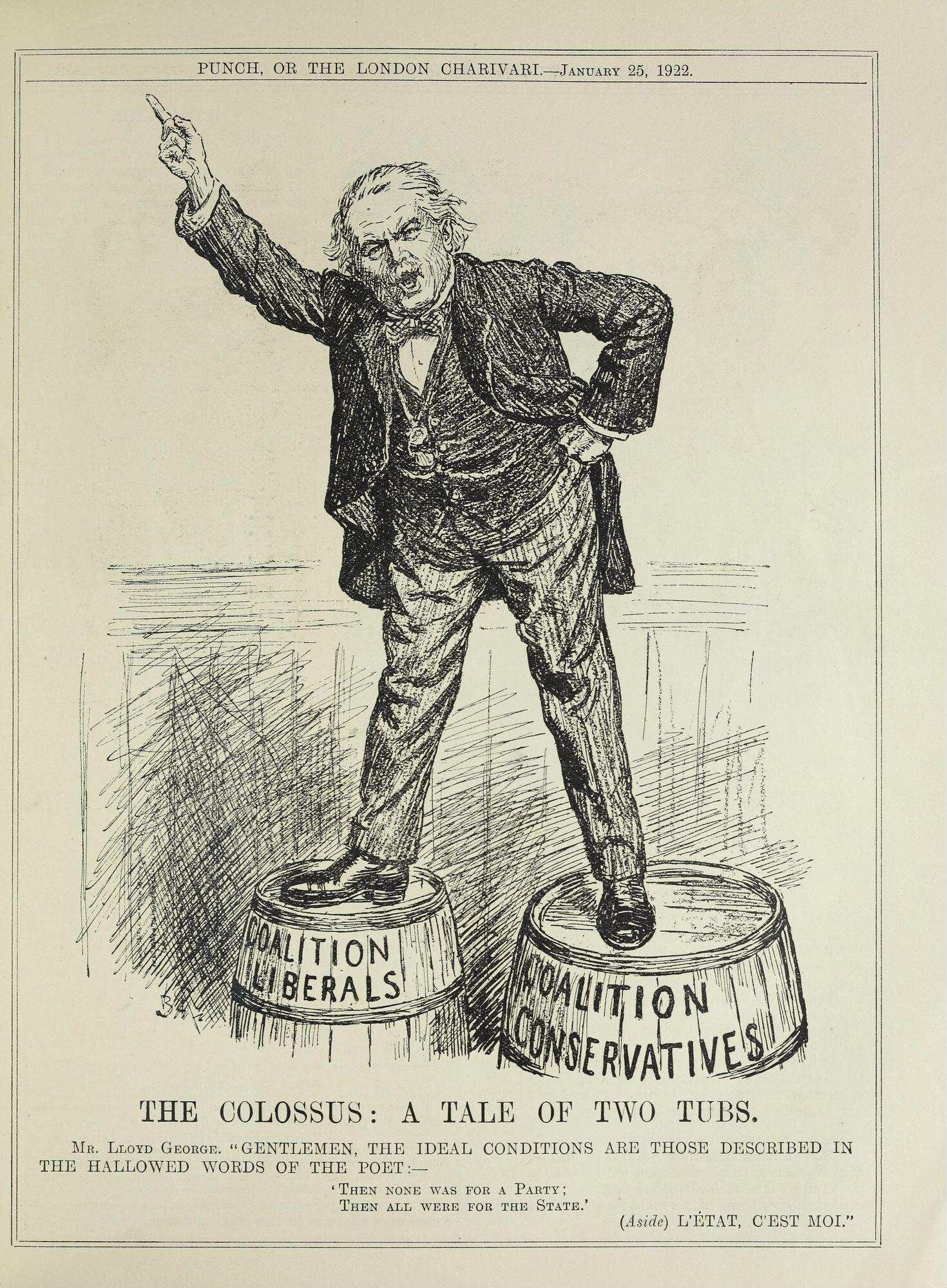

Chanak Crisis. The

Carlton Club meeting decided the Conservatives should end the coalition and contest the next election alone. Lloyd George resigned as prime minister, but continued as the leader of a Liberal faction. After an awkward reunion with Asquith's faction in 1923, Lloyd George led the weak Liberal Party from 1926 to 1931. He proposed innovative schemes for public works and other reforms, but made only modest gains in the

1929 election. After 1931, he was a mistrusted figure heading a small rump of breakaway Liberals opposed to the

National Government. In 1940, he refused to serve in

Churchill's War Cabinet. He was elevated to the peerage in 1945 but died before he could take his seat in the

House of Lords

The House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the lower house, the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England. One of the oldest ext ...

.

Early life

David George was born on 17 January 1863 in

Chorlton-on-Medlock

Chorlton-on-Medlock is an inner city area of Manchester, England.

Historic counties of England, Historically in Lancashire, Chorlton-on-Medlock is bordered to the north by the River Medlock, which runs immediately south of Manchester city cen ...

, Manchester, to

Welsh parents William George and Elizabeth Lloyd George. William died in June 1864 of pneumonia, aged 44. David was just over one year old. Elizabeth George moved with her children to her native

Llanystumdwy in Caernarfonshire, where she lived in a cottage known as Highgate with her brother Richard, a shoemaker, lay minister and a strong Liberal. Richard Lloyd was a towering influence on his nephew and David adopted his uncle's surname to become "Lloyd George". Lloyd George was educated at the local

Anglican

Anglicanism, also known as Episcopalianism in some countries, is a Western Christianity, Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the ...

school, Llanystumdwy

National School, and later under tutors.

He was brought up with

Welsh as his first language;

Roy Jenkins

Roy Harris Jenkins, Baron Jenkins of Hillhead (11 November 1920 – 5 January 2003) was a British politician and writer who served as the sixth President of the European Commission from 1977 to 1981. At various times a Member of Parliamen ...

, another Welsh politician, notes that, "Lloyd George was Welsh, that his whole culture, his whole outlook, his language was Welsh."

Though brought up a devout evangelical, Lloyd George privately lost his religious faith as a young man. Biographer Don Cregier says he became "a Deist and perhaps an agnostic, though he remained a chapel-goer and connoisseur of good preaching all his life." He was nevertheless, according to

Frank Owen, "one of the foremost fighting leaders of a fanatical Welsh

Nonconformity" for a quarter of a century.

Legal practice and early politics

Lloyd George qualified as a solicitor in 1884 after being

articled to a firm in

Porthmadog

Porthmadog (), originally Portmadoc until 1972 and known locally as "Port", is a coastal town and community (Wales), community in the Eifionydd area of Gwynedd, Wales, and the historic counties of Wales, historic county of Caernarfonshire. It li ...

and taking Honours in his final law examination. He set up his own practice in the back parlour of his uncle's house in 1885.

Although many prime ministers have been

barrister

A barrister is a type of lawyer in common law jurisdiction (area), jurisdictions. Barristers mostly specialise in courtroom advocacy and litigation. Their tasks include arguing cases in courts and tribunals, drafting legal pleadings, jurisprud ...

s, Lloyd George is, as of , the only solicitor to have held that office.

As a solicitor, Lloyd George was politically active from the start, campaigning for his uncle's

Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world.

The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left. For example, while the political systems ...

in the

1885 election. He was attracted by

Joseph Chamberlain

Joseph Chamberlain (8 July 1836 – 2 July 1914) was a British statesman who was first a radical Liberal Party (UK), Liberal, then a Liberal Unionist after opposing home rule for Ireland, and eventually was a leading New Imperialism, imperial ...

's "unauthorised programme" of

Radical reform. After the election, Chamberlain split with Gladstone in opposition to Irish

Home Rule

Home rule is the government of a colony, dependent country, or region by its own citizens. It is thus the power of a part (administrative division) of a state or an external dependent country to exercise such of the state's powers of governan ...

, and Lloyd George moved to join the

Liberal Unionists

The Liberal Unionist Party was a British political party that was formed in 1886 by a faction that broke away from the Liberal Party. Led by Lord Hartington (later the Duke of Devonshire) and Joseph Chamberlain, the party established a political ...

. Uncertain of which wing to follow, he moved a resolution in support of Chamberlain at a local Liberal club and travelled to

Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands (county), West Midlands, within the wider West Midlands (region), West Midlands region, in England. It is the Lis ...

to attend the first meeting of Chamberlain's new National Radical Union, but arrived a week too early. In 1907 Lloyd George would tell

Herbert Lewis that he had thought Chamberlain's plan for a federal solution to the Home Rule Question correct in 1886 and still thought so, and that "If Henry Richmond, Osborne Morgan and the Welsh members had stood by Chamberlain on an agreement as regards the

elshdisestablishment, they would have carried Wales with them"

His legal practice quickly flourished; he established branch offices in surrounding towns and took his brother

William

William is a masculine given name of Germanic languages, Germanic origin. It became popular in England after the Norman Conquest, Norman conquest in 1066,All Things William"Meaning & Origin of the Name"/ref> and remained so throughout the Middle ...

into partnership in 1887.

Lloyd George's legal and political triumph came in the

Llanfrothen

Llanfrothen () is a hamlet and Community (Wales), community in the county of Gwynedd, Wales, between the towns of Porthmadog and Blaenau Ffestiniog and is 108.1 miles (174.0 km) from Cardiff. In 2011 the population of Llanfrothen was 437 wi ...

burial case, which established the right of

Nonconformists to be buried according to denominational rites in parish burial grounds, as given by the

Burial Laws Amendment Act 1880 but theretofore ignored by the

Anglican

Anglicanism, also known as Episcopalianism in some countries, is a Western Christianity, Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the ...

clergy. On Lloyd George's advice, a Baptist burial party broke open a gate to a cemetery that had been locked against them by the vicar. The vicar sued them for trespass and although the jury returned a verdict for the party, the local judge misrecorded the jury's verdict and found in the vicar's favour. Suspecting bias, Lloyd George's clients won on appeal to the Divisional Court of Queen's Bench in London, where Lord Chief Justice

Coleridge found in their favour.

The case was hailed as a great victory throughout Wales and led to Lloyd George's adoption as the Liberal candidate for

Carnarvon Boroughs on 27 December 1888.

The same year, he and other young Welsh Liberals founded a monthly paper, ''Udgorn Rhyddid'' (Bugle of Freedom).

In 1889, Lloyd George became an

alderman

An alderman is a member of a Municipal government, municipal assembly or council in many jurisdictions founded upon English law with similar officials existing in the Netherlands (wethouder) and Belgium (schepen). The term may be titular, denotin ...

on

Carnarvonshire County Council

A county council is the elected administrative body governing an area known as a county. This term has slightly different meanings in different countries.

Australia

In the Australian state of New South Wales, county councils are special purpose ...

(a new body which had been created by the

Local Government Act 1888

The Local Government Act 1888 (51 & 52 Vict. c. 41) was an Act of Parliament (United Kingdom), act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom which established county councils and county borough councils in England and Wales. It came into effect ...

) and would remain so for the rest of his life.

Lloyd George would also serve the county as a

Justice of the Peace (1910), chairman of

Quarter Sessions

The courts of quarter sessions or quarter sessions were local courts that were traditionally held at four set times each year in the Kingdom of England from 1388; they were extended to Wales following the Laws in Wales Act 1535. Scotland establ ...

(1929–38), and

Deputy Lieutenant in 1921.

Marriage

Lloyd George married

Margaret Owen, the daughter of a well-to-do local farming family, on 24 January 1888.

They had five children, see later.

Early years as a member of Parliament (1890–1905)

Lloyd George's career as a member of parliament began when he was returned as a Liberal MP for

Caernarfon Boroughs (now

Caernarfon

Caernarfon (; ) is a List of place names with royal patronage in the United Kingdom, royal town, Community (Wales), community and port in Gwynedd, Wales. It has a population of 9,852 (with Caeathro). It lies along the A487 road, on the easter ...

), narrowly winning the

by-election on 10 April 1890, following the death of the Conservative member

Edmund Swetenham. He would remain an MP for the same constituency until 1945, 55 years later.

Lloyd George's early beginnings in Westminster may have proven difficult for him as a radical liberal and "a great outsider".

Backbench members of the House of Commons were not paid at that time, so Lloyd George supported himself and his growing family by continuing to practise as a solicitor. He opened an office in London under the name of "Lloyd George and Co." and continued in partnership with William George in

Criccieth

Criccieth, also spelled Cricieth (), is a town and community (Wales), community in Gwynedd, Wales, on the boundary between the Llŷn Peninsula and Eifionydd. The town is west of Porthmadog, east of Pwllheli and south of Caernarfon. It had a ...

. In 1897, he merged his growing London practice with that of Arthur Rhys Roberts (who was to become

Official Solicitor) under the name of "Lloyd George, Roberts and Co."

Welsh affairs

Kenneth O. Morgan describes Lloyd George as a "lifelong Welsh nationalist" and suggests that between 1880 and 1914 he was "the symbol and tribune of the

national reawakening of Wales", although he is also clear that from the early 1900s his main focus gradually shifted to UK-wide issues.

He also became an associate of

Tom Ellis, MP for Meirionydd, having previously told a Caernarfon friend in 1888 that he was a "Welsh Nationalist of the Ellis type".

Decentralisation and Welsh disestablishment

One of Lloyd George's first acts as an MP was to organise an informal grouping of Welsh Liberal members with a programme that included; disestablishing and disendowing the

Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the State religion#State churches, established List of Christian denominations, Christian church in England and the Crown Dependencies. It is the mother church of the Anglicanism, Anglican Christian tradition, ...

in Wales,

temperance reform, and establishing

Welsh home rule.

He was keen on

decentralisation and thus

Welsh devolution

Welsh devolution is the Devolution in the United Kingdom, transfer of legislative powers for self-governance to Wales by the Parliament of the United Kingdom. The current system of devolution began following the enactment of the Government of Wa ...

, starting with the devolution of the

Church in Wales

The Church in Wales () is an Anglican church in Wales, composed of six dioceses.

The Archbishop of Wales does not have a fixed archiepiscopal see, but serves concurrently as one of the six diocesan bishops. The position is currently held b ...

saying in 1890: "I am deeply impressed with the fact that Wales has wants and inspirations of her own which have too long been ignored, but which must no longer be neglected. First and foremost amongst these stands the cause of Religious Liberty and Equality in Wales. If returned to Parliament by you, it shall be my earnest endeavour to labour for the triumph of this great cause. I believe in a liberal extension of the principle of Decentralization."

During the next decade, Lloyd George campaigned in Parliament largely on Welsh issues, in particular for disestablishment and disendowment of the Church of England. When Gladstone retired in 1894 after the defeat of the

second Home Rule Bill, the Welsh Liberal members chose him to serve on a deputation to

William Harcourt to press for specific assurances on Welsh issues. When those assurances were not provided, they resolved to take independent action if the government did not bring a bill for disestablishment. When a bill was not forthcoming, he and three other Welsh Liberals (

D. A. Thomas,

Herbert Lewis and

Frank Edwards) refused the

whip

A whip is a blunt weapon or implement used in a striking motion to create sound or pain. Whips can be used for flagellation against humans or animals to exert control through pain compliance or fear of pain, or be used as an audible cue thro ...

on 14 April 1894, but accepted

Lord Rosebery's assurance and rejoined the official Liberals on 29 May.

Cymru Fydd and Welsh devolution

Historian

Emyr Price referred to Lloyd George as "the first architect of Welsh devolution and its most famous advocate" as well as "the pioneering advocate of a powerful parliament for the Welsh people". Lloyd George himself stated in 1890, "the Imperial Parliament is so overweighted with the concerns of a large empire that it cannot possibly devote the time and trouble necessary to legislate for the peculiar and domestic requirements of each and every separate province". These statements would later be used to advocate for a Welsh assembly in the

1979 Welsh devolution referendum. Lloyd George felt that disestablishment, land reform and other forms of Welsh devolution could only be achieved if Wales formed its own government within a federal imperial system.

In 1895, in a failed Church in Wales Bill, Lloyd George added an amendment in a discreet attempt at forming a sort of Welsh home rule, a national council for appointment of the Welsh Church commissioners. Although not condemned by

Tom Ellis MP, this was to the annoyance of

J. Bryn Roberts MP and the Home Secretary

H. H. Asquith

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith (12 September 1852 – 15 February 1928) was a British statesman and Liberal Party (UK), Liberal politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1908 to 1916. He was the last ...

MP.

He was also a co-leader of , a national Welsh party with liberal values with the goals of promoting a "stronger Welsh identity" and establishing a Welsh government. He hoped that would become a force like the

Irish National Party. He abandoned this idea after being criticised in Welsh newspapers for bringing about the defeat of the

Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world.

The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left. For example, while the political systems ...

in the

1895 election. In an AGM meeting in

Newport on 16 January 1896 of the South Wales Liberal Federation, led by

D. A. Thomas, a proposal was made to unite the North and South Liberal Federations with to form The Welsh National Federation. This was a proposal which the North Wales Liberal Federation had already agreed to. However, the South Wales Liberal Federation rejected this. According to Lloyd George, he was shouted down by "Newport Englishmen" in the meeting, although the ''

South Wales Argus'' suggested the poor crowd behaviour came from Lloyd George's supporters.

Following difficulty in uniting the Liberal federations along with in the South East and thus, difficulty in gaining support for Home Rule for Wales, Lloyd George shifted his focus to improving the socio-economic environment of Wales as part of the

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

and the

British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

. Although Lloyd George considered himself a "Welshman first", he saw the opportunities for Wales within the UK.

Uniting Welsh Liberals

In 1898, Lloyd George created the Welsh National Liberal Council, a loose umbrella organisation covering the two federations, but with very little power. In time, it became known as the Liberal Party of Wales.

Support of Welsh institutions

Lloyd George had a connection to or promoted the establishment of the

National Library of Wales

The National Library of Wales (, ) in Aberystwyth is the national legal deposit library of Wales and is one of the Welsh Government sponsored bodies. It is the biggest library in Wales, holding over 6.5 million books and periodicals, and the l ...

, the

National Museum of Wales

National may refer to:

Common uses

* Nation or country

** Nationality – a ''national'' is a person who is subject to a nation, regardless of whether the person has full rights as a citizen

Places in the United States

* National, Maryland, c ...

and the Welsh Department of the

Board of Education

A board of education, school committee or school board is the board of directors or board of trustees of a school, local school district or an equivalent institution.

The elected council determines the educational policy in a small regional area, ...

.

He also showed considerable support for the

University of Wales

The University of Wales () is a confederal university based in Cardiff, Wales. Founded by royal charter in 1893 as a federal university with three constituent colleges – Aberystwyth, Bangor and Cardiff – the university was the first universit ...

, that its establishment raised the status of Welsh people and that the university deserved greater funding by the UK government.

Opposition to the Boer War

Lloyd George had been impressed by his journey to Canada in 1899. Although sometimes wrongly supposed—both at the time and subsequently—to be a

Little Englander

The Little Englanders were a British political movement who opposed empire-building and advocated complete independence for Britain's existing colonies. The ideas of Little Englandism first began to gain popularity in the late 18th century after ...

, he was not an opponent of the British Empire ''per se'', but in a speech at Birkenhead (21 November 1901) he stressed that it needed to be based on freedom, including for India, not "racial arrogance".

Consequently, he gained national fame by displaying vehement opposition to the

Second Boer War

The Second Boer War (, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, Transvaal War, Anglo–Boer War, or South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer republics (the South African Republic and ...

.

Following Rosebery's lead, he based his attack firstly on what were supposed to be Britain's war aims—remedying the grievances of the and in particular the claim that they were wrongly denied the right to vote, saying "I do not believe the war has any connection with the franchise. It is a question of 45% dividends" and that England (which did not then have universal male suffrage) was more in need of franchise reform than the Boer republics. A second attack came on the cost of the war, which, he argued, prevented overdue social reform in England, such as old-age pensions and workmen's cottages. As the fighting continued his attacks moved to its conduct by the generals, who, he said (basing his words on reports by

William Burdett-Coutts in ''

The Times

''The Times'' is a British Newspaper#Daily, daily Newspaper#National, national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its modern name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its si ...

''), were not providing for the sick or wounded soldiers and were starving Boer women and children in concentration camps. But his major thrusts were reserved for the Chamberlains, accusing them of

war profiteering

A war profiteer is any person or organization that derives unreasonable profit (economics), profit from warfare or by selling weapons and other goods to parties at war. The term typically carries strong negative connotations. General profiteerin ...

through the family company

Kynoch

Kynoch was a manufacturer of ammunition that was later incorporated into ICI, but remained as a brand name for sporting cartridges.

History

The firm of Pursall and Phillips operated a 'percussion cap manufactory' at Whittall Street, in Birmin ...

Ltd, of which Chamberlain's brother was chairman. The firm had won tenders to the

War Office

The War Office has referred to several British government organisations throughout history, all relating to the army. It was a department of the British Government responsible for the administration of the British Army between 1857 and 1964, at ...

, though its prices were higher than some of its competitors. After speaking at a meeting in Birmingham Lloyd George had to be smuggled out disguised as a policeman, as his life was in danger from the mob. At this time the Liberal Party was badly split as

H. H. Asquith

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith (12 September 1852 – 15 February 1928) was a British statesman and Liberal Party (UK), Liberal politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1908 to 1916. He was the last ...

,

R. B. Haldane and others were supporters of the war and formed the

Liberal Imperial League.

Opposition to the Education Act 1902

On 24 March

Arthur Balfour

Arthur James Balfour, 1st Earl of Balfour (; 25 July 184819 March 1930) was a British statesman and Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician who served as the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1902 to 1905. As Foreign Secretary ...

, just about to take office as Prime Minister, introduced a bill which was to become the

Education Act 1902

The Education Act 1902 ( 2 Edw. 7. c. 42), also known as the Balfour Act, was a highly controversial act of Parliament that set the pattern of elementary education in England and Wales for four decades. It was brought to Parliament by a Conserva ...

. Lloyd George supported the bill's proposals to bring voluntary schools (i.e. religious schools—mainly Church of England, and some Roman Catholic schools in certain inner city areas) in England and Wales under the control of local school boards, who would conduct inspections and appoint two out of each school's six managers. However, other measures were more contentious: the majority-religious school managers would retain the power to employ or sack teachers on religious grounds and would receive money from the

rates

Rate or rates may refer to:

Finance

* Rate (company), an American residential mortgage company formerly known as Guaranteed Rate

* Rates (tax), a type of taxation system in the United Kingdom used to fund local government

* Exchange rate, rate ...

(local property taxes). This offended nonconformist opinion, then in a period of revival, as it seemed like a return to the hated

church rates (which had been compulsory until 1868), and inspired a large grassroots campaign against the bill.

Within days of the bill's unveiling (27 March), Lloyd George denounced "priestcraft" in a speech to his constituents, and he began an active campaign of speaking against the bill, both in public in Wales (with a few speeches in England) and in the House of Commons. On 12 November, Balfour accepted an amendment (willingly, but a rare case of him doing so), ostensibly from

Alfred Thomas, chairman of the Welsh Parliamentary Liberal Party, but in reality instigated by Lloyd George, transferring control of Welsh schools from appointed boards to the elected county councils. The Education Act became law on 20 December 1902.

Lloyd George now announced the real purpose of the amendment, described as a "booby trap" by his biographer John Grigg. The Welsh National Liberal Council soon adopted his proposal that county councils should refuse funding unless repairs were carried out to schools (many were in a poor state), and should also demand control of school governing bodies and a ban on religious tests for teachers; "no control, no cash" was Lloyd George's slogan. Lloyd George negotiated with

A. G. Edwards, Anglican

Bishop of St Asaph

The Bishop of St Asaph heads the Church in Wales diocese of St Asaph.

The diocese covers the counties of Conwy county borough, Conwy and Flintshire, Wrexham county borough, the eastern part of Merioneth in Gwynedd and part of northern Powys. The ...

, and was prepared to settle on an "agreed religious syllabus" or even to allow Anglican teaching in schools, provided the county councils retained control of teacher appointments, but this compromise failed after opposition from other Anglican Welsh bishops. A well-attended meeting at Park Hall Cardiff (3 June 1903) passed a number of resolutions by acclamation: county council control of schools, withholding money from schools or even withholding rates from unsupportive county councils. The Liberals soon gained control of all thirteen Welsh County Councils. Lloyd George continued to speak in England against the bill, but the campaign there was less aggressively led, taking the form of passive resistance to rate paying.

In August 1904 the government brought in the Education (Local Authority Default) Act giving the Board of Education power to take charge of schools, which Lloyd George immediately nicknamed the "Coercion of Wales Act". He addressed another convention in Cardiff on 6 October 1904, during which he proclaimed that the Welsh flag was "a dragon rampant, not a sheep recumbent". Under his leadership, the convention pledged not to maintain elementary schools, or to withdraw children from elementary schools altogether so that they could be taught privately by the nonconformist churches. In Travis Crosbie's words, public resistance to the Education Act had caused a "perfect impasse".

There was no progress between Welsh counties and Westminster until 1905.

Having already gained national recognition for his anti-Boer War campaigns, Lloyd George's leadership of the attacks on the Education Act gave him a strong parliamentary reputation and marked him as a likely future cabinet member. The Act served to reunify the Liberals after their divisions over the Boer War and to increase Nonconformist influence in the party, which then included educational reform as policy in the

1906 election, which resulted in a Liberal landslide.

All 34 Welsh seats returned a Liberal, except for one Labour seat in Merthyr Tydfil.

Other stances

Lloyd George also supported the

romantic nationalist idea of

Pan-Celtic unity and gave a speech at the 1904

Pan-Celtic Congress in

Caernarfon

Caernarfon (; ) is a List of place names with royal patronage in the United Kingdom, royal town, Community (Wales), community and port in Gwynedd, Wales. It has a population of 9,852 (with Caeathro). It lies along the A487 road, on the easter ...

.

During his second-ever speech in the House of Commons, Lloyd George criticised the grandeur of the monarchy.

Lloyd George wrote extensively for Liberal-supporting papers such as the ''

Manchester Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in Manchester in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'' and changed its name in 1959, followed by a move to London. Along with its sister paper, ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardi ...

'' and spoke on Liberal issues (particularly temperance—the "

local option"—and national as opposed to denominational education) throughout England and Wales.

He served as the legal adviser of

Theodor Herzl

Theodor Herzl (2 May 1860 – 3 July 1904) was an Austria-Hungary, Austro-Hungarian Jewish journalist and lawyer who was the father of Types of Zionism, modern political Zionism. Herzl formed the World Zionist Organization, Zionist Organizat ...

in his negotiations with the British government regarding the

Uganda Scheme, proposed as an alternative homeland for the Jews due to Turkish refusal to grant a charter for Jewish settlement in Palestine.

President of the Board of Trade (1905–1908)

In 1905, Lloyd George entered the new Liberal Cabinet of

Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman

Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman (né Campbell; 7 September 183622 April 1908) was a British statesman and Liberal Party (UK), Liberal Party politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1905 to 1908 and Liberal Party (UK)#Liberal le ...

as

President of the Board of Trade

The president of the Board of Trade is head of the Board of Trade. A committee of the His Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council, Privy Council of the United Kingdom, it was first established as a temporary committee of inquiry in the 17th centur ...

.

The first priority on taking office was the repeal of the

Education Act 1902

The Education Act 1902 ( 2 Edw. 7. c. 42), also known as the Balfour Act, was a highly controversial act of Parliament that set the pattern of elementary education in England and Wales for four decades. It was brought to Parliament by a Conserva ...

. Lloyd George took the lead along with

Augustine Birrell, President of the Board of Education. Lloyd George appears to have been the dominant figure on the committee drawing up the bill in its later stages and insisted that the bill create a separate education committee for Wales. Birrell complained privately that the bill, introduced in the Commons on 9 April 1906, owed more to Lloyd George and that he himself had had little say in its contents.

The bill passed the House of Commons greatly amended but was completely mangled by the House of Lords.

For the rest of the year Lloyd George made numerous public speeches attacking the House of Lords for mutilating the bill with wrecking amendments, in defiance of the Liberals' electoral mandate to reform the 1902 Act. Lloyd George was rebuked by King

Edward VII

Edward VII (Albert Edward; 9 November 1841 – 6 May 1910) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 22 January 1901 until Death and state funeral of Edward VII, his death in 1910.

The second child ...

for these speeches: the Prime Minister defended him to the King's secretary

Francis Knollys, stating that his behaviour in Parliament was more constructive but that in speeches to the public "the combative spirit seems to get the better of him".

No compromise was possible and the bill was abandoned, allowing the 1902 Act to continue in effect.

As a result of Lloyd George's lobbying, a separate department for Wales was created within the Board of Education.

Nonconformists were bitterly upset by the failure of the Liberal Party to reform the 1902 Education Act, its most important promise to them, and over time their support for the Liberal Party slowly fell away.

At the Board of Trade Lloyd George introduced legislation on many topics, from

merchant shipping and the

Port of London to

companies

A company, abbreviated as co., is a legal entity representing an association of legal people, whether natural, juridical or a mixture of both, with a specific objective. Company members share a common purpose and unite to achieve specifi ...

and railway regulation. His main achievement was in stopping a proposed national strike of the railway unions by brokering an agreement between the unions and the railway companies. While almost all the companies refused to recognise the unions, Lloyd George persuaded the companies to recognise elected representatives of the workers who sat with the company representatives on conciliation boards—one for each company. If those boards failed to agree then an arbitrator would be called upon.

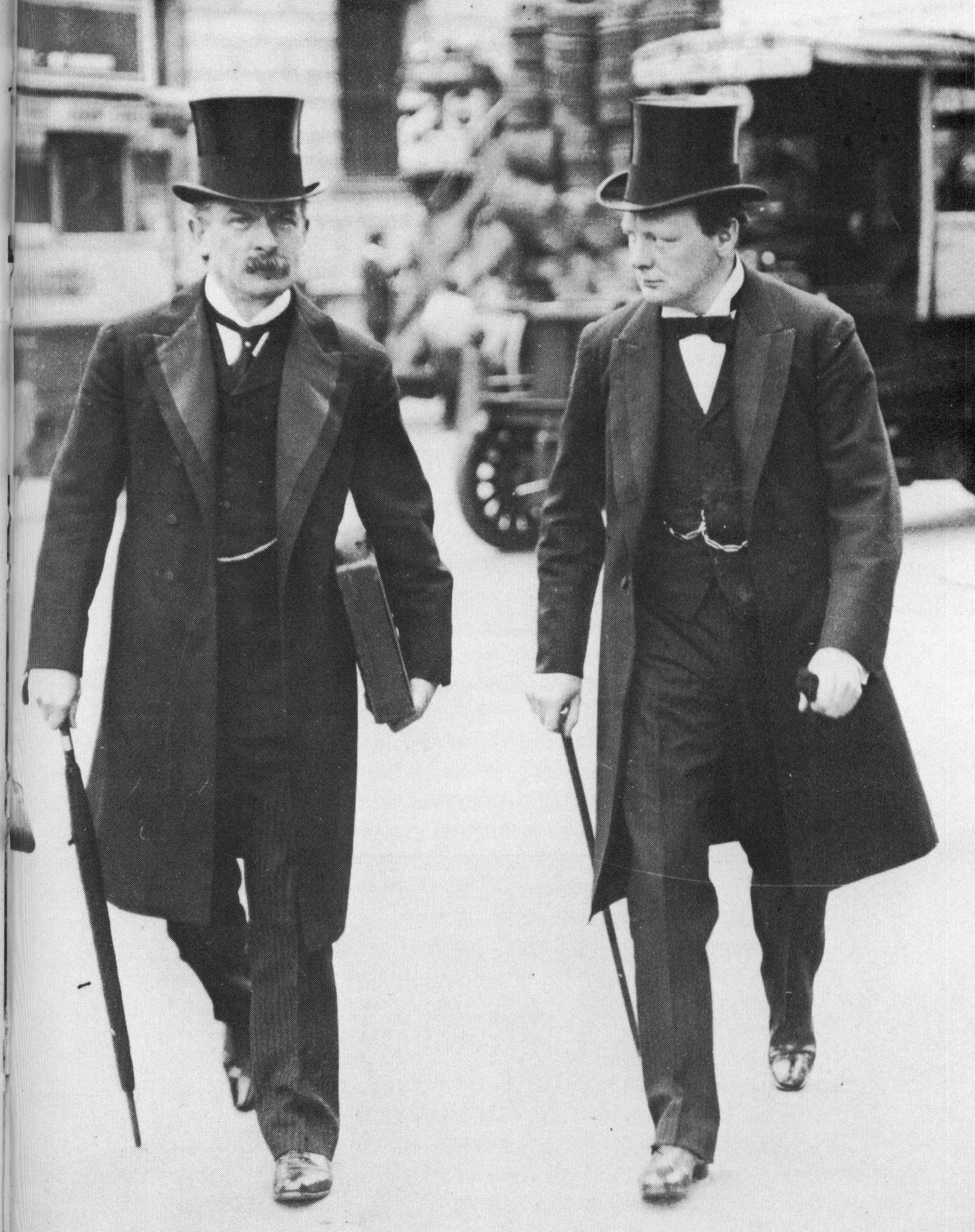

Chancellor of the Exchequer (1908–1915)

On Campbell-Bannerman's death, he succeeded Asquith, who had become prime minister, as

Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and the head of HM Treasury, His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, t ...

from 1908 to 1915.

While he continued some work from the Board of Trade—for example, legislation to establish the

Port of London Authority

The Port of London Authority (PLA) is a self-funding public trust established on 31 March 1909 in accordance with the Port of London Act 1908 to govern the Port of London. Its responsibility extends over the Tideway of the River Thames and its ...

and to pursue traditional Liberal programmes such as licensing law reforms—his first major trial in this role was over the 1909–1910 Naval Estimates. The Liberal manifesto at the

1906 general election included a commitment to reduce military expenditure. Lloyd George strongly supported this, writing to

Reginald McKenna, First Lord of the Admiralty, of "the emphatic pledges given by all of us at the last general election to reduce the gigantic expenditure on armaments built up by the recklessness of our predecessors." He then proposed the programme be reduced from six to four

dreadnoughts. This was adopted by the government, but there was a public storm when the Conservatives, with covert support from the First Sea Lord, Admiral

Jackie Fisher, campaigned for more with the slogan "We want eight and we won't wait". This resulted in Lloyd George's defeat in Cabinet and the adoption of estimates including provision for eight dreadnoughts. During this period he was also a target of protest by the women's suffrage movement, for he professed personal support for extension of the suffrage but did not move for changes within the Parliament process.

People's Budget, 1909

In 1909, Lloyd George introduced his

People's Budget

The 1909/1910 People's Budget was a proposal of the Liberal government that introduced unprecedented taxes on the lands and incomes of Britain's wealthy to fund new social welfare programmes, such as non-contributary old age pensions under Ol ...

, imposing a 20%

tax on the unearned increase in the value of land, payable at the death of the owner or sale of the land, and d. on undeveloped land and minerals, increased death duties, a rise in income tax, and the introduction of

Supertax on income over £3,000. There were taxes also on luxuries,

alcohol

Alcohol may refer to:

Common uses

* Alcohol (chemistry), a class of compounds

* Ethanol, one of several alcohols, commonly known as alcohol in everyday life

** Alcohol (drug), intoxicant found in alcoholic beverages

** Alcoholic beverage, an alco ...

and tobacco, so that money could be made available for the new welfare programmes as well as new battleships. The nation's landowners (well represented in the House of Lords) were intensely angry at the new taxes, mostly at the proposed very high tax on land values, but also because the instrumental redistribution of wealth could be used to detract from an argument for protective tariffs.

The immediate consequences included the end of the

Liberal League, and Rosebery breaking friendship with the Liberal Party, which in itself was for Lloyd George a triumph. He had won the case of social reform without losing the debate on Free Trade.

Arthur Balfour

Arthur James Balfour, 1st Earl of Balfour (; 25 July 184819 March 1930) was a British statesman and Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician who served as the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1902 to 1905. As Foreign Secretary ...

denounced the budget as "vindictive, inequitable, based on no principles, and injurious to the productive capacity of the country."

Roy Jenkins

Roy Harris Jenkins, Baron Jenkins of Hillhead (11 November 1920 – 5 January 2003) was a British politician and writer who served as the sixth President of the European Commission from 1977 to 1981. At various times a Member of Parliamen ...

described it as the most reverberating since Gladstone's in 1860.

In the House of Commons, Lloyd George gave a brilliant account of the budget, which was attacked by the Conservatives. On the stump, notably at his Limehouse speech in 1909, he denounced the Conservatives and the wealthy classes with all his very considerable oratorical power. Excoriating the House of Lords in another speech, Lloyd George said, "should 500 men, ordinary men, chosen accidentally from among the unemployed, override the judgement—the deliberate judgement—of millions of people who are engaged in the industry which makes the wealth of the country?". In a break with

convention, the budget was defeated by the Conservative majority in the House of Lords. The elections of 1910 narrowly upheld the Liberal government. The 1909 budget was passed on 28 April 1910 by the Lords and received the

Royal Assent

Royal assent is the method by which a monarch formally approves an act of the legislature, either directly or through an official acting on the monarch's behalf. In some jurisdictions, royal assent is equivalent to promulgation, while in othe ...

on the 29th. Subsequently, the

Parliament Act 1911 removed the House of Lords' power to block money bills, and with a few exceptions replaced their veto power over most bills with a power to delay them for up to two years.

Although old-age pensions had already been introduced by Asquith as Chancellor, Lloyd George was largely responsible for the introduction of state financial support for the sick and infirm (known colloquially as "going on the Lloyd George" for decades afterwards)—legislation referred to as the

Liberal Reforms. Lloyd George also succeeded in putting through Parliament his

National Insurance Act 1911

The National Insurance Act 1911 (1 & 2 Geo. 5. c. 55) created National Insurance, originally a system of health insurance for industrial workers in Great Britain based on contributions from employers, the government, and the workers themselves. ...

, making provision for sickness and invalidism, and a system of unemployment insurance. He was helped in his endeavours by forty or so backbenchers who regularly pushed for new social measures, often voted with Labour MPs. These social reforms in Britain were the beginnings of a

welfare state

A welfare state is a form of government in which the State (polity), state (or a well-established network of social institutions) protects and promotes the economic and social well-being of its citizens, based upon the principles of equal oppor ...

and fulfilled the aim of dampening down the demands of the growing working class for rather more radical solutions to their impoverishment.

Under his leadership, after 1909 the Liberals extended minimum wages to farmworkers.

Mansion House Speech, 1911

Lloyd George was an opponent of warfare but he paid little attention to foreign affairs until the

Agadir Crisis

The Agadir Crisis, Agadir Incident, or Second Moroccan Crisis, was a brief crisis sparked by the deployment of a substantial force of French troops in the interior of Morocco in July 1911 and the deployment of the German gunboat to Agadir, ...

of 1911. After consulting Edward Grey (the foreign minister) and H.H. Asquith (the prime minister) he gave a stirring and patriotic speech at

Mansion House on 21 July 1911, during that year's annual white tie dinner at the official residence of the Lord Mayor of London, where the Chancellor of the Exchequer delivers a speech known as the "Mansion House Speech". He stated:

But if a situation were to be forced upon us in which peace could only be preserved by the surrender of the great and beneficent position Britain has won by centuries of heroism and achievement, by allowing Britain to be treated where her interests were vitally affected as if she were of no account in the Cabinet of nations, then I say emphatically that peace at that price would be a humiliation intolerable for a great country like ours to endure. National honour is no party question. The security of our great international trade is no party question.

He was warning both France and Germany, but the public response cheered solidarity with France and hostility toward Germany. Berlin was outraged, blaming Lloyd George for doing "untold harm both with regard to German public opinion and the negotiations."

Count Metternich, Germany's ambassador in London, said, "Mr Lloyd George's speech came upon us like a thunderbolt".

Marconi scandal 1913

In 1913, Lloyd George, along with

Rufus Isaacs, the Attorney General, was involved in the

Marconi scandal. Accused of speculating in Marconi shares on the inside information that they were about to be awarded a key government contract (which would have caused them to increase in value), he told the House of Commons that he had not speculated in the shares of "that company". He had in fact bought shares in the American Marconi Company.

Welsh disestablishment

Lloyd George was instrumental in fulfilling a long-standing aspiration to disestablish the

Anglican Church

Anglicanism, also known as Episcopalianism in some countries, is a Western Christianity, Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the ...

of Wales. As with

Irish Home Rule, previous attempts to enact this had failed in the 1892–1895 Governments, and were now made possible by the removal of the Lords' veto in 1911, and as with Home Rule the initial bill (1912) was delayed for two years by the Lords, becoming

law in 1914, only to be

suspended for the duration of the war. After the

Welsh Church (Temporalities) Act 1919 was passed, Welsh Disestablishment finally

came into force in 1920. This Act also removed the right of the six Welsh Bishops in the new

Church in Wales

The Church in Wales () is an Anglican church in Wales, composed of six dioceses.

The Archbishop of Wales does not have a fixed archiepiscopal see, but serves concurrently as one of the six diocesan bishops. The position is currently held b ...

to sit in the House of Lords and removed (disendowed) certain pre-1662 property rights.

First World War

Lloyd George was as surprised as almost everyone else by the

outbreak of the First World War. On 23 July 1914, almost a month after the assassination of

Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria

Archduke Franz Ferdinand Carl Ludwig Joseph Maria of Austria (18 December 1863 – 28 June 1914) was the heir presumptive to the throne of Austria-Hungary. His Assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, assassination in Sarajevo was the ...

and on the eve of the Austro-Hungarian ultimatum to Serbia, he made a speech advocating "economy" in the House of Commons, saying that Britain's relations with Germany were better than for many years. On 27 July he told

C. P. Scott of the ''

Manchester Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in Manchester in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'' and changed its name in 1959, followed by a move to London. Along with its sister paper, ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardi ...

'' that Britain would keep out of the impending war. With the Cabinet divided, and most ministers reluctant for Britain to get involved, he struck Asquith as "statesmanlike" at the Cabinet meeting on 1 August, favouring keeping Britain's options open. The next day he seemed likely to resign if Britain intervened, but he held back at Cabinet on Monday 3 August, moved by the news that Belgium would resist Germany's demand of passage for her army across her soil. He was seen as a key figure whose stance helped to persuade almost the entire Cabinet to support British intervention. He was able to give the more pacifist members of the cabinet and the Liberal Party a principle—the rights of small nations—which meant they could support the war and maintain united political and popular support.

Lloyd George remained in office as Chancellor of the Exchequer for the first year of the Great War. The budget of 17 November 1914 had to allow for lower taxation receipts because of the reduction in world trade. The

Crimean

Crimea ( ) is a peninsula in Eastern Europe, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, almost entirely surrounded by the Black Sea and the smaller Sea of Azov. The Isthmus of Perekop connects the peninsula to Kherson Oblast in mainland Ukrai ...

and

Boer

Boers ( ; ; ) are the descendants of the proto Afrikaans-speaking Free Burghers of the eastern Cape frontier in Southern Africa during the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. From 1652 to 1795, the Dutch East India Company controlled the Dutch ...

Wars had largely been paid for out of taxation, but Lloyd George raised

debt financing

Debt is an obligation that requires one party, the debtor, to pay money borrowed or otherwise withheld from another party, the creditor. Debt may be owed by a sovereign state or country, local government, company, or an individual. Commer ...

of £321 million. Large (but deferred) increases in Supertax and income tax rates were accompanied by increases in excise duties, and the budget produced a tax increase of £63 million in a full year. His last budget, on 4 May 1915, showed a growing concern for the effects of alcohol on the war effort, with large increases in duties, and a scheme of state control of alcohol sales in specified areas. The excise proposals were opposed by the Irish Nationalists and the Conservatives, and were abandoned.

Minister of Munitions

Lloyd George gained a heroic reputation with his energetic work as Minister of Munitions in 1915 and 1916, setting the stage for his move up to the height of power. After a long struggle with the War Office, he wrested responsibility for arms production away from the generals, making it a purely industrial department, with considerable expert assistance from

Walter Runciman.

The two men gained the respect of Liberal cabinet colleagues for improving administrative capabilities, and increasing outputs.

When the

Shell Crisis of 1915

The Shell Crisis of 1915 was a shortage of artillery shells on the front lines in the First World War that led to a political crisis in the United Kingdom. Previous military experience led to an over-reliance on shrapnel to attack infantry in th ...

dismayed public opinion with the news that the Army was running short of artillery shells, demands rose for a strong leader to take charge of munitions. In the

first coalition ministry, formed in May 1915, Lloyd George was made

Minister of Munitions

The Minister of Munitions was a British government position created during the First World War to oversee and co-ordinate the production and distribution of munitions for the war effort. The position was created in response to the Shell Crisis o ...

, heading a new department. In this position, he won great acclaim, which formed the basis for his political ascent. All historians agree that he boosted national morale and focussed attention on the urgent need for greater output, but many also say the increase in munitions output in 1915–16 was due largely to reforms already underway, though not yet effective before he had even arrived. The Ministry broke through the cumbersome bureaucracy of the War Office, resolved labour problems, rationalised the supply system and dramatically increased production. Within a year it became the largest buyer, seller and employer in Britain.

Lloyd George was not at all satisfied with the progress of the war. He wanted to "knock away the props", by attacking Germany's allies—from early in 1915 he argued for the sending of British troops to the Balkans to assist Serbia and bring Greece and other Balkan countries onto the side of the Allies (this was eventually done—the

Salonika expedition—although not on the scale that Lloyd George had wanted, and mountain ranges made his suggestions of grand Balkan offensives impractical); in 1916, he wanted to send machine guns to

Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to ...

(insufficient amounts were available for this to be feasible). These suggestions began a period of poor relations with the

Chief of the Imperial General Staff,

General Robertson, who was "brusque to the point of rudeness" and "barely concealed his contempt for Lloyd George's military opinions", to which he was in the habit of retorting "I've 'eard different".

Lloyd George persuaded

Kitchener, the

Secretary of State for War

The secretary of state for war, commonly called the war secretary, was a secretary of state in the Government of the United Kingdom, which existed from 1794 to 1801 and from 1854 to 1964. The secretary of state for war headed the War Offic ...

, to raise a

Welsh Division

The 53rd (Welsh) Infantry Division was an infantry Division (military), division of the British Army that fought in both the World War I, First and World War II, Second World Wars. Originally raised in 1908 as the Welsh Division, part of the Ter ...

, and, despite Kitchener's threat of resignation, to recognise nonconformist chaplains in the Army.

Late in 1915, Lloyd George became a strong supporter of general conscription, an issue that divided Liberals, and helped the passage of several

conscription acts from January 1916 onwards. In spring 1916

Alfred Milner

Alfred Milner, 1st Viscount Milner, (23 March 1854 – 13 May 1925) was a British politician, statesman and colonial administrator who played a very important role in the formulation of British foreign and domestic policy between the mid-189 ...

hoped Lloyd George could be persuaded to bring down the coalition government by resigning, but this did not happen.

Secretary of State for War

In June 1916 Lloyd George succeeded

Lord Kitchener (who died when the ship

HMS ''Hampshire'' was sunk taking him on a mission to Russia) as

Secretary of State for War

The secretary of state for war, commonly called the war secretary, was a secretary of state in the Government of the United Kingdom, which existed from 1794 to 1801 and from 1854 to 1964. The secretary of state for war headed the War Offic ...

, although he had little control over strategy, as General Robertson had been given direct right of access to the Cabinet so as to bypass Kitchener. He did succeed in securing the appointment of Sir

Eric Geddes to take charge of military railways behind British lines in France, with the honorary rank of major-general. Lloyd George told a journalist,

Roy W. Howard, in late September that "the fight must be to a finish—to a knockout", a rejection of President

Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

's offer to mediate.

Lloyd George was increasingly frustrated at the limited gains of the

Somme Offensive, criticising

General Haig to

Ferdinand Foch

Ferdinand Foch ( , ; 2 October 1851 – 20 March 1929) was a French general, Marshal of France and a member of the Académie Française and French Academy of Sciences, Académie des Sciences. He distinguished himself as Supreme Allied Commander ...

on a visit to the Western Front in September (British casualty ratios were worse than those of the French, who were more experienced and had more artillery), proposing sending Robertson on a mission to Russia (he refused to go), and demanding that more troops be sent to Salonika to help Romania. Robertson eventually threatened to resign.

Much of the press still argued that the professional leadership of Haig and Robertson was preferable to civilian interference that had led to disasters like

Gallipoli

The Gallipoli Peninsula (; ; ) is located in the southern part of East Thrace, the European part of Turkey, with the Aegean Sea to the west and the Dardanelles strait to the east.

Gallipoli is the Italian form of the Greek name (), meaning ' ...

and

Kut.

Lord Northcliffe, owner of ''

The Times

''The Times'' is a British Newspaper#Daily, daily Newspaper#National, national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its modern name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its si ...

'', stormed into Lloyd George's office and, finding him unavailable, told his secretary "You can tell him that I hear he has been interfering with Strategy and that if he goes on I will break him", and the same day (11 October) Lloyd George also received a warning letter from

H. A. Gwynne, editor of the ''

Morning Post''. He was obliged to give his "word of honour" to Asquith that he had complete confidence in Haig and Robertson and thought them irreplaceable, but he wrote to Robertson wanting to know how their differences had been leaked to the press (affecting to believe that Robertson had not personally "authorised such a breach of confidence & discipline"). He asserted his right to express his opinions about strategy in November, by which time ministers had taken to holding meetings to which Robertson was not invited.

The weakness of Asquith as a planner and organiser was increasingly apparent to senior officials. After Asquith had refused, then agreed to, and then refused again Lloyd George's demand to be allowed to chair a small committee to manage the war, he resigned in December 1916. Grey was among leading Asquithians who had identified Lloyd George's intentions the previous month. Lloyd George became prime minister, with the nation demanding he take vigorous charge of the war.

Although during the political crisis Robertson had advised Lloyd George to "stick to it" and form a small War Council, Lloyd George had planned if necessary to appeal to the country. His Military Secretary Colonel

Arthur Lee prepared a memo blaming Robertson and the General Staff for the loss of Serbia and Romania. Lloyd George was restricted by his promise to the Unionists to keep Haig as Commander-in-Chief and the press support for the generals, although

Milner and

Curzon were also sympathetic to campaigns to increase British power in the Middle East. After Germany's offer (12 December 1916) of a negotiated peace, Lloyd George rebuffed President Wilson's request for the belligerents to state their war aims by demanding terms tantamount to German defeat.

Prime Minister (1916–1922)

Lloyd George's tenure as wartime prime minister from 1916 to 1918, remains a subject of intense historical scrutiny, primarily due to its military success and his restructuring of the office along presidential lines. His ascent to the premiership marked a significant departure from traditional norms, as he was the first Welshman to hold the office. Once in office his leadership style diverged markedly from his predecessors, characterized by a more dynamic and interventionist approach to governance. Lloyd George relied on his political background: rooted in Liberalism, advocating for social reforms and challenging the established aristocratic order, he had made his mark through his persuasive oratory and political acumen.

War leader (1916–1918)

Forming a government

The fall of Asquith as prime minister split the Liberal Party into two factions: those who supported him and those who supported the coalition government. In his ''War Memoirs'', Lloyd George compared himself with Asquith:

There are certain indispensable qualities essential to the Chief Minister of the Crown in a great war. ... Such a minister must have courage, composure, and judgment. All this Mr. Asquith possessed in a superlative degree. ... But a war minister must also have vision, imagination and initiative—he must show untiring assiduity, must exercise constant oversight and supervision of every sphere of war activity, must possess driving force to energize this activity, must be in continuous consultation with experts, official and unofficial, as to the best means of using the resources of the country in conjunction with the Allies for the achievement of victory. If to this can be added a flair for conducting a great fight, then you have an ideal War Minister.

After December 1916 Lloyd George relied on the support of Conservatives and of the press baron

Lord Northcliffe (who owned both ''

The Times

''The Times'' is a British Newspaper#Daily, daily Newspaper#National, national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its modern name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its si ...

'' and the ''

Daily Mail

The ''Daily Mail'' is a British daily Middle-market newspaper, middle-market Tabloid journalism, tabloid conservative newspaper founded in 1896 and published in London. , it has the List of newspapers in the United Kingdom by circulation, h ...

''). Besides the Prime Minister, the five-member

War Cabinet contained three Conservatives (Lord President of the Council and Leader of the House of Lords

Lord Curzon

George Nathaniel Curzon, 1st Marquess Curzon of Kedleston (11 January 1859 – 20 March 1925), known as Lord Curzon (), was a British statesman, Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician, explorer and writer who served as Viceroy of India ...

, Chancellor of the Exchequer and Leader of the House of Commons

Bonar Law

Andrew Bonar Law (; 16 September 1858 – 30 October 1923) was a British statesman and politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from October 1922 to May 1923.

Law was born in the British colony of New Brunswick (now a Canadi ...

, and

Minister without Portfolio

A minister without portfolio is a government minister without specific responsibility as head of a government department. The sinecure is particularly common in countries ruled by coalition governments and a cabinet with decision-making authorit ...

Lord Milner) and

Arthur Henderson

Arthur Henderson (13 September 1863 – 20 October 1935) was a British iron moulder and Labour Party (UK), Labour politician. He was the first Labour Cabinet of the United Kingdom, cabinet minister, won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1934 and, uniqu ...

, unofficially representing

Labour.

Edward Carson

Edward Henry Carson, Baron Carson, Privy Council (United Kingdom), PC, Privy Council of Ireland, PC (Ire), King's Counsel, KC (9 February 1854 – 22 October 1935), from 1900 to 1921 known as Sir Edward Carson, was an Irish unionist politician ...

was appointed

First Lord of the Admiralty

First Lord of the Admiralty, or formally the Office of the First Lord of the Admiralty, was the title of the political head of the English and later British Royal Navy. He was the government's senior adviser on all naval affairs, responsible f ...

, as had been widely touted during the intrigues of the previous month, but excluded from the War Cabinet. Amongst the few Liberal frontbenchers to support Lloyd George were

Christopher Addison (who had played an important role in drumming up some backbench Liberal support for Lloyd George),

H. A. L. Fisher,

Lord Rhondda and

Sir Albert Stanley.

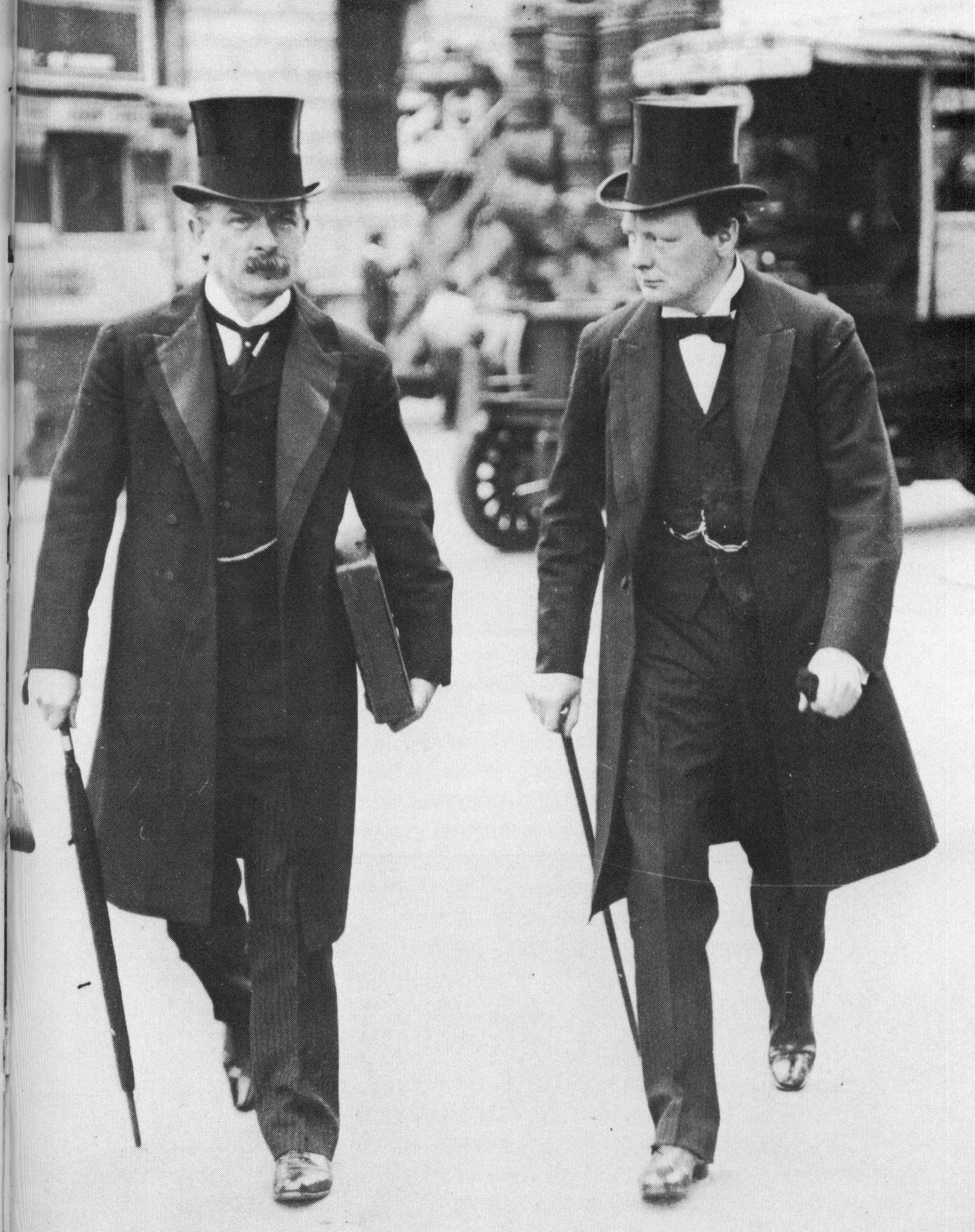

Edwin Montagu and Churchill joined the government in the summer of 1917.

Lloyd George's Secretariat, popularly known as Downing Street's "

Garden Suburb", assisted him in discharging his responsibilities within the constraints of the war cabinet system. Its function was to maintain contact with the numerous departments of government, to collect information, and to report on matters of special concern. Its leading members were

George Adams and

Philip Kerr, and the other secretaries included

David Davies,

Joseph Davies,

Waldorf Astor and, later,

Cecil Harmsworth.

Lloyd George wanted to make the destruction of the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

a major British war aim, and two days after taking office told Robertson that he wanted a major victory, preferably the capture of

Jerusalem

Jerusalem is a city in the Southern Levant, on a plateau in the Judaean Mountains between the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and the Dead Sea. It is one of the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest cities in the world, and ...

, to impress British public opinion.

At the Rome Conference (5–6 January 1917) Lloyd George was discreetly quiet about plans to take Jerusalem, an object which advanced British interests rather than doing much to win the war. Lloyd George proposed sending heavy guns to Italy with a view to defeating Austria-Hungary, possibly to be balanced by a transfer of Italian troops to Salonika but was unable to obtain the support of the French or Italians, and Robertson talked of resigning.

Nivelle affair

Lloyd George engaged almost constantly in intrigues calculated to reduce the power of the generals, including trying to subordinate British forces in France to the French

General Nivelle. He backed Nivelle because he thought he had "proved himself to be a Man" by his successful counterattacks at

Verdun

Verdun ( , ; ; ; official name before 1970: Verdun-sur-Meuse) is a city in the Meuse (department), Meuse departments of France, department in Grand Est, northeastern France. It is an arrondissement of the department.

In 843, the Treaty of V ...

, and because of his promises that he could break the German lines in 48 hours. Nivelle increasingly complained of Haig's dragging his feet rather than cooperating with their plans for the offensive.

The plan was to put British forces under Nivelle's direct command for the great 1917 offensive. The British would attack first, thereby tying down the German reserves. Then the French would strike and score an overwhelming victory in two days. It was announced at a War Cabinet meeting on 24 February, to which neither Robertson nor

Lord Derby (Secretary of State for War) had been invited. Ministers felt that the French generals and staff had shown themselves more skilful than the British in 1916, whilst politically Britain had to give wholehearted support to what would probably be the last major French effort of the war. The Nivelle proposal was then given to Robertson and Haig without warning on 26–27 February at the

Calais Conference (minutes from the War Cabinet meeting were not sent to

the King until 28 February, so that he did not have a prior chance to object). Robertson in particular protested vehemently. Finally, a compromise was reached whereby Haig would be under Nivelle's orders but would retain operational control of British forces and keep a right of appeal to London "if he saw good reason". After further argument the ''status quo'', that Haig was an ally of the French but was expected to defer to their wishes, was largely restored in mid-March.

The British attack at the

Battle of Arras (9–14 April 1917) was partly successful but with much higher casualties than the Germans suffered. There had been many delays and the Germans, suspecting an attack, had shortened their lines to the strong

Hindenburg Line

The Hindenburg Line (, Siegfried Position) was a German Defense line, defensive position built during the winter of 1916–1917 on the Western Front (World War I), Western Front in France during the First World War. The line ran from Arras to ...

. The

French attack on the Aisne River in mid-April gained some tactically important high ground but failed to achieve the promised decisive breakthrough, pushing the French Army to the point of

mutiny

Mutiny is a revolt among a group of people (typically of a military or a crew) to oppose, change, or remove superiors or their orders. The term is commonly used for insubordination by members of the military against an officer or superior, ...

. While Haig gained prestige, Lloyd George lost credibility, and the affair further poisoned relations between himself and the "Brasshats".

U-boat war

= Shipping

=

In early 1917 the Germans had resumed

unrestricted submarine warfare in a bid to achieve victory on the

Western Approaches. Lloyd George set up a Ministry of Shipping under

Sir Joseph Maclay, a Glasgow shipowner who was not, until after he left office, a member of either House of Parliament, and housed in a wooden building in a specially drained lake in

St James's Park

St James's Park is a urban park in the City of Westminster, central London. A Royal Park, it is at the southernmost end of the St James's area, which was named after a once isolated medieval hospital dedicated to St James the Less, now the ...

, within a few minutes' walk from the

Admiralty. The Junior Minister and House of Commons spokesman was

Leo Chiozza Money, with whom Maclay did not get on, but on whose appointment Lloyd George insisted, feeling that their qualities would complement one another. The Civil Service staff was headed by the highly able

John Anderson (then only thirty-four years old) and included

Arthur Salter. A number of shipping magnates were persuaded, like Maclay himself, to work unpaid for the ministry (as had a number of industrialists for the Ministry of Munitions), who were also able to obtain ideas privately from junior naval officers who were reluctant to argue with their superiors in meetings. The ministers heading the Board of Trade, for Munitions (

Addison) and for Agriculture and Food (

Lord Rhondda), were also expected to co-operate with Maclay.

[

In accordance with a pledge Lloyd George had given in December 1916 nearly 90% of Britain's merchant shipping tonnage was soon brought under state control (previously less than half had been controlled by the Admiralty), whilst remaining privately owned (similar measures were in force at the time for the railways). Merchant shipping was concentrated, largely on Chiozza Money's initiative, on the transatlantic route where it could more easily be protected, instead of being spread out all over the globe (this relied on imports coming first into North America). Maclay began the process of increasing ship construction, although he was hampered by shortages of steel and labour, and ships under construction in the United States were confiscated by the Americans when she entered the war. In May 1917 Eric Geddes, based at the Admiralty, was put in charge of shipbuilding, and in July he became ]First Lord of the Admiralty

First Lord of the Admiralty, or formally the Office of the First Lord of the Admiralty, was the title of the political head of the English and later British Royal Navy. He was the government's senior adviser on all naval affairs, responsible f ...

.[ Later the German U-boats were defeated in 1918.

]

= Convoys

=

Lloyd George had raised the matter of convoy