Linguistic rights are the

human

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') or modern humans are the most common and widespread species of primate, and the last surviving species of the genus ''Homo''. They are Hominidae, great apes characterized by their Prehistory of nakedness and clothing ...

and

civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' political freedom, freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and ...

concerning the individual and collective

right

Rights are law, legal, social, or ethics, ethical principles of freedom or Entitlement (fair division), entitlement; that is, rights are the fundamental normative rules about what is allowed of people or owed to people according to some legal sy ...

to choose the language or languages for

communication

Communication is commonly defined as the transmission of information. Its precise definition is disputed and there are disagreements about whether Intention, unintentional or failed transmissions are included and whether communication not onl ...

in a private or public atmosphere. Other parameters for analyzing linguistic rights include the degree of territoriality, amount of positivity, orientation in terms of assimilation or maintenance, and overtness.

Linguistic rights include, among others, the right to one's own language in legal, administrative and judicial acts,

language education

Language education refers to the processes and practices of teaching a second language, second or foreign language. Its study reflects interdisciplinarity, interdisciplinary approaches, usually including some applied linguistics. There are f ...

, and media in a language understood and freely chosen by those concerned.

Linguistic rights in international law are usually dealt in the broader framework of

cultural

Culture ( ) is a concept that encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and Social norm, norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, Social norm, customs, capabilities, Attitude (psychology), attitudes ...

and

educational rights.

Important documents for linguistic rights include the

Universal Declaration of Linguistic Rights

The Universal Declaration of Linguistic Rights (known also as the Barcelona Declaration) is a document signed by the International PEN Club, and several non-governmental organizations in 1996 to support linguistic rights, especially those of endan ...

(1996), the

European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages

The European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages (ECRML) is a European treaty (CETS 148) adopted in 1992 under the auspices of the Council of Europe to protect and promote historical regional and minority languages in Europe. However, t ...

(1992), the

Convention on the Rights of the Child

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (commonly abbreviated as the CRC or UNCRC) is an international international human rights treaty which sets out the civil, political, economic, social, health and cultural rights of ch ...

(1989) and the

Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities

The Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities (FCNM) is a multilateral treaty of the Council of Europe aimed at protecting the minority rights, rights of minorities. It came into effect in 1998 and by 2009 it had been ratif ...

(1988), as well as

Convention against Discrimination in Education and the

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) is a multilateral treaty that commits nations to respect the civil and political rights of individuals, including the right to life, freedom of religion, freedom of speech, freedom ...

(1966).

History

Linguistic rights became more and more prominent throughout the course of history as language came to be increasingly seen as a part of nationhood. Although policies and legislation involving language have been in effect in early European history, these were often cases where a language was being imposed upon people while other languages or dialects were neglected. Most of the initial literature on linguistic rights came from countries where linguistic and/or national divisions grounded in linguistic diversity have resulted in linguistic rights playing a vital role in maintaining stability. However, it was not until the 1900s that linguistic rights gained official status in politics and international accords.

Linguistic rights were first included as an international human right in the

Universal Declaration of Human Rights

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) is an international document adopted by the United Nations General Assembly that enshrines the Human rights, rights and freedoms of all human beings. Drafted by a UN Drafting of the Universal D ...

in 1948.

Formal treaty-based language rights are mostly concerned with

minority rights

Minority rights are the normal individual rights as applied to members of racial, ethnic, class, religious, linguistic or gender and sexual minorities, and also the collective rights accorded to any minority group.

Civil-rights movements oft ...

. The history of such language rights can be split into five phases.

[ Skutnabb-Kangas, Tove, Phillipson, Robert, and Rannut, Mart. (1994). "Linguistic human rights: overcoming linguistic discrimination." Walter de Gruyter.]

# Pre-1815. Language rights are covered in bilateral agreements, but not in international treaties, e.g.

Treaty of Lausanne

The Treaty of Lausanne (, ) is a peace treaty negotiated during the Lausanne Conference of 1922–1923 and signed in the Palais de Rumine in Lausanne, Switzerland, on 24 July 1923. The treaty officially resolved the conflict that had initially ...

(1923).

# Final Act of the

Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon, Napol ...

(1815). The conclusion to

Napoleon I

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

's empire-building was signed by 7 European major powers. It granted the right to use Polish to Poles in Poznan alongside German for official business. Also, some national constitutions protects the language rights of national minorities, e.g. Austrian Constitutional Law of 1867 grants ethnic minorities the right to develop their nationality and language.

# Between World I and World War II. Under the aegis of the

League of Nations

The League of Nations (LN or LoN; , SdN) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace ...

, Peace Treaties and major multilateral and international conventions carried clauses protecting minorities in Central and Eastern Europe, e.g., the right to private use of any language, and provision for instruction in primary schools through medium of own language.

[Caporti, Francesco. (1979). "Study of the Rights of Persons Belonging to Ethnic, Religious and Linguistic Minorities." New York: United Nations.] Many national constitutions followed this trend. But not all signatories provided rights to minority groups within their own borders such as United Kingdom, France, and US. Treaties also provided right of complaint to League of Nations and

International Court of Justice

The International Court of Justice (ICJ; , CIJ), or colloquially the World Court, is the only international court that Adjudication, adjudicates general disputes between nations, and gives advisory opinions on International law, internation ...

.

# 1945–1970s. International legislation for protection of human rights was undertaken within infrastructure of

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

. Mainly for individual rights and collective rights to oppressed groups for

self-determination

Self-determination refers to a people's right to form its own political entity, and internal self-determination is the right to representative government with full suffrage.

Self-determination is a cardinal principle in modern international la ...

.

# Early 1970s onwards, there was a renewed interest in

rights of minorities, including language rights of minorities. e.g. UN Declaration on the Rights of Persons Belonging to National or Ethnic, Religious and Linguistic Minorities.

Theoretical discussion

Language rights + human rights = linguistic human rights (LHR)

Some make a distinction between language rights and linguistic human rights because the former concept covers a much wider scope.

Thus, not all language rights are LHR, although all LHR are language rights. One way of distinguishing language rights from LHR is between what is necessary, and what is enrichment-oriented.

Necessary rights, as in human rights, are those needed for basic needs and for living a dignified life, e.g. language-related identity, access to mother tongue(s), right of access to an official language, no enforced language shift, access to formal primary education based on language, and the right for minority groups to perpetuate as a distinct group, with own languages. Enrichment rights are above basic needs, e.g. right to learn foreign languages.

Individual linguistic rights

The most basic definition of linguistic rights is the right of individuals to use their language with other members of their linguistic group, regardless of the status of their language. They evolve from general human rights, in particular: non-discrimination, freedom of expression, right to private life, and the right of members of a linguistic minority to use their language with other members of their community.

[Varennes, Fernand de. (2007). "Language Rights as an Integral Part of Human Rights – A Legal Perspective". In Koenig, Matthias, Guchteneire, Paul F. A. (eds), ''Democracy and human rights in multicultural societies'' (pp 115–125): Ashgate Publishing Ltd.]

Individual linguistic rights are provided for in the

Universal Declaration of Human Rights

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) is an international document adopted by the United Nations General Assembly that enshrines the Human rights, rights and freedoms of all human beings. Drafted by a UN Drafting of the Universal D ...

:

* Article 2 – all individuals are entitled to the rights declared without discrimination based on

language

Language is a structured system of communication that consists of grammar and vocabulary. It is the primary means by which humans convey meaning, both in spoken and signed language, signed forms, and may also be conveyed through writing syste ...

.

* Article 10 – individuals are entitled to a fair trial, and this is generally recognized to involve the right to an interpreter if an individual does not understand the language used in criminal court proceedings, or in a criminal accusation. The individual has the right to have the interpreter translate the proceedings, including court documents.

* Article 19 – individuals have the right to

freedom of expression

Freedom of speech is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or a community to articulate their opinions and ideas without fear of retaliation, censorship, or legal sanction. The rights, right to freedom of expression has been r ...

, including the right to choose any language as the medium of expression.

* Article 26 – everyone has the

right to education

The right to education has been recognized as a human rights, human right in a number of international conventions, including the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights which recognizes a right to free education, free, pr ...

, with relevance to the language of medium of instruction.

Linguistic rights can be applied to the private arena and the public domain.

Private use of language

Most treaties or language rights documents distinguish between the private use of a language by individuals and the use of a language by public authorities.

Existing international human rights mandate that all individuals have the right to private and family life, freedom of expression, non-discrimination and/or the right of persons belonging to a linguistic minority to use their language with other members of their group. The

United Nations Human Rights Committee

The United Nations Human Rights Committee is a treaty body composed of 18 experts, established by a 1966 human rights treaty, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). The Committee meets for three four-week sessions per yea ...

defines privacy as:

... the sphere of a person's life in which he or she can freely express his or her identity, be it by entering into relationships with others or alone. The Committee is of the view that a person's surname nd nameconstitutes an important component of one's identity and that the protection against arbitrary or unlawful interference with one's privacy includes the protection against arbitrary or unlawful interference with the right to choose and change one's own name.

This means that individuals have the right to have their name or surname in their own language, regardless of whether the language is official or recognised, and state or public authorities cannot interfere with this right arbitrarily or unlawfully.

Linguistic rights in the public domain

The public domain, with respect to language use, can be divided into judicial proceedings and general use by public officials.

According to Article 10 of the

Universal Declaration of Human Rights

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) is an international document adopted by the United Nations General Assembly that enshrines the Human rights, rights and freedoms of all human beings. Drafted by a UN Drafting of the Universal D ...

, individuals have the right to a fair trial. Therefore, in the name of fairness of judicial proceedings, it is an established linguistic right of an individual to an interpreter when he or she does not understand the language used in criminal court proceedings, or in a criminal accusation. The public authorities must either use the language which the individual understands, or hire an interpreter to translate the proceedings, including court cases.

General use by public officials can cover matters including public education, public radio and television broadcasting, the provision of services to the public, and so on. It is often accepted to be reasonable and justified for public officials to use the

language of minorities, to an appropriate degree and level in their activities, when the numbers and geographic concentration of the speakers of a minority language are substantial enough. However, this is a contentious topic as the decision of substantiation is often arbitrary. The

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) is a multilateral treaty that commits nations to respect the civil and political rights of individuals, including the right to life, freedom of religion, freedom of speech, freedom ...

, Article 26, does promise to protect all individuals from discrimination on the grounds of language. Following that, Article 27 declares, "

minorities

The term "minority group" has different meanings, depending on the context. According to common usage, it can be defined simply as a group in society with the least number of individuals, or less than half of a population. Usually a minority g ...

shall not be denied the right... to use their own language".

[Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. "International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights". March 23, 1976] The

Convention against Discrimination in Education, Article 5, also does declares the rights for minorities to "use or teach their own language".

Collective linguistic rights

Collective linguistic rights are linguistic rights of a group, notably a language group or a

state

State most commonly refers to:

* State (polity), a centralized political organization that regulates law and society within a territory

**Sovereign state, a sovereign polity in international law, commonly referred to as a country

**Nation state, a ...

. Collective rights mean "the right of a linguistic group to ensure the survival of its language and to transmit the language to future generations".

[Chen, Albert H. Y. "The Philosophy of Language Rights." Language Sciences, 20(1), 45–54.] Language groups are complex and more difficult to demarcate than states.

[Coulmas, Florian. (1998). "Language Rights – Interests of State, Language Groups and the Individual." Language Sciences,20(1), 63–72.] Part of this difficulty is that members within language groups assign different roles to their language, and there are also difficulties in defining a language.

Some states have legal provisions for the safeguard of collective linguistic rights because there are clear-cut situations under particular historical and social circumstances.

Collective linguistic rights apply to states because they express themselves in one or more languages.

Generally, the language régime of states, which is communicated through allocation of statuses to languages used within its boundaries, qualifies linguistic rights claimed by groups and individuals in the name of efficient governance, in the best interest of the

common good

In philosophy, Common good (economics), economics, and political science, the common good (also commonwealth, common weal, general welfare, or public benefit) is either what is shared and beneficial for all or most members of a given community, o ...

.

States are held in check by international conventions and the demands of the citizens. Linguistic rights translate to laws differently from country to country, as there is no generally accepted standard legal definition.

[Paulston, Christina Bratt. "Language Policies and Language Rights". Annual Review Anthropology, 26, 73–85.]

Territoriality vs. personality principles

The principle of territoriality refers to linguistic rights being focused solely within a territory, whereas the principle of personality depends on the linguistic status of the person(s) involved.

An example of the application of territoriality is the case of

Switzerland

Switzerland, officially the Swiss Confederation, is a landlocked country located in west-central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the south, France to the west, Germany to the north, and Austria and Liechtenstein to the east. Switzerland ...

, where linguistic rights are defined within clearly divided language-based cantons. An example of the application of personality is in federal

Canadian legislation, which grants the right to services in French or English regardless of territory.

Negative vs. positive rights

Negative linguistic rights mean the right for the exercise of language without the interference of the

State

State most commonly refers to:

* State (polity), a centralized political organization that regulates law and society within a territory

**Sovereign state, a sovereign polity in international law, commonly referred to as a country

**Nation state, a ...

.

Positive linguistic rights require positive action by the State involving the use of public money, such as public education in a specific language, or state-provided services in a particular language.

Assimilation-oriented vs. maintenance-oriented

Assimilation-oriented types of language rights refer to the aim of the law to assimilate all citizens within the country, and range from prohibition to toleration.

An example of prohibition type laws is the treatment of

Kurds

Kurds (), or the Kurdish people, are an Iranian peoples, Iranic ethnic group from West Asia. They are indigenous to Kurdistan, which is a geographic region spanning southeastern Turkey, northwestern Iran, northern Iraq, and northeastern Syri ...

in

Turkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

where they had been forbidden to use the Kurdish language. Assimilation-oriented approaches to language rights can also be seen as a form of focus on the individuals right to communicate with others inside a system. Many policies of linguistic assimilation being tied to the concept of nation building and facilitating communication between various groups inside of a singular state system.

Maintenance-oriented types of language rights refer to laws aiming to enable the maintenance of all languages within a country, and range from permission to promotion. An example of laws that promote language rights is the Basque Normalization Law, where the Basque language is promoted. Many maintenance-oriented approaches require both a framework of collective and positive rights and significant government funding in order to produce the desired outcomes of linguistic maintenance. In Wales and Quebec, for example, there is significant debate over funding and the use of collective rights in building an effective maintenance framework.

The neutral point between assimilation-orientation and maintenance-orientation is non-discrimination prescription, which forbids discrimination based on language. However the non-discrimination position has also been seen as just another form of assimilationist policy as its primarily just leads to a more extended period of assimilation into the majority language rather than a perpetual continuation of the minority language.

Overt vs. covert

Another dimension for analyzing language rights is with degree of overtness and covertness.

Degree of overtness refers to the extent laws or covenants are explicit with respect to language rights, and covertness the reverse. For example, Indian laws are overt in promoting language rights, whereas the English Language Amendments to the US Constitution are overt prohibition. The

Charter of the United Nations

The Charter of the United Nations is the foundational treaty of the United Nations (UN). It establishes the purposes, governing structure, and overall framework of the UN system, including its six principal organs: the Secretariat, the G ...

, the

Universal Declaration of Human Rights

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) is an international document adopted by the United Nations General Assembly that enshrines the Human rights, rights and freedoms of all human beings. Drafted by a UN Drafting of the Universal D ...

, the

International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights

The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) is a multilateral treaty adopted by the United Nations General Assembly (GA) on 16 December 1966 through GA. Resolution 2200A (XXI), and came into force on 3 January 197 ...

, the

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) is a multilateral treaty that commits nations to respect the civil and political rights of individuals, including the right to life, freedom of religion, freedom of speech, freedom ...

, and the UN

Convention on the Rights of the Child

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (commonly abbreviated as the CRC or UNCRC) is an international international human rights treaty which sets out the civil, political, economic, social, health and cultural rights of ch ...

all fall under covert toleration.

Criticisms of the framework of linguistic human rights

Some have criticized linguistic rights proponents for taking language to be a single coherent construct, pointing out instead the difference between language and speech communities, and putting too much concern on inter-language discrimination rather than intra-language discrimination.

Other issues pointed out are the assumptions that the collective aims of linguistic minority groups are uniform, and that the concept of collective rights is not without its problems.

There is also the protest against the framework of Linguistic Human Rights singling out minority languages for special treatment, causing limited resources to be distributed unfairly. This has led to a call for deeper ethnographic and historiographic study into the relationship between speakers' attitudes, speakers' meaning, language, power, and speech communities.

Practical application

Linguistic rights manifest as legislation (the passing of a law), subsequently becoming a statute to be enforced.

[Siegel, Lawrence. (2006). "The Argument for a Constitutional Right to Communication and Language". Sign Language Studies,6(1),255–272.][Christina Bratt Paulston. (1997). "Language Policies and Language Rights". Annual Review Anthropology,26,73–85.] Language legislation delimiting official usage can by grouped into official, institutionalizing, standardizing, and liberal language legislation, based on its function:

[ Skutnabb-Kangas, Tove. (2000). "Linguistic Genocide in Education – or Worldwide Diversity and Human Rights?" Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc.] Official legislation makes languages official in the domains of legislation, justice, public administration, and education, ommonly according to territoriality and personality Various combinations of both principles are also used.... Institutionalizing legislation covers the unofficial domains of labour, communications, culture, commerce, and business....

In relation to legislation, a causal effect of linguistic rights is

language policy

Language policy is both an interdisciplinary academic field and implementation of ideas about language use.

Some scholars such as Joshua Fishman and Ofelia García consider it as part of sociolinguistics. On the other hand, other scholars such as ...

. The field of

language planning

In sociolinguistics, language planning (also known as language engineering) is a deliberate effort to influence the function, structure or acquisition of languages or language varieties within a speech community.Kaplan B., Robert, and Rich ...

falls under language policy. There are three types of language planning: status planning (uses of language), acquisition planning (users of language), and corpus planning (language itself).

Language rights at international and regional levels

International platform

The Universal Declaration of Linguistic Rights was approved on 6 June 1996 in Barcelona, Spain. It was the culmination of work by a committee of 50 experts under the auspices of

UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO ) is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) with the aim of promoting world peace and International secur ...

. Signatories were 220 persons from over 90 states, representing NGOs and International PEN Clubs Centres. This Declaration was drawn up in response to calls for linguistic rights as a fundamental human right at the 12th Seminar of the International Association for the Development of Intercultural Communication and the Final Declaration of the General Assembly of the International Federation of Modern Language Teachers. Linguistic rights in this Declaration stems from the language community, i.e., collective rights, and explicitly includes both regional and immigrant minority languages.

Overall, this document is divided into sections including: Concepts, General Principles, Overall linguistic regime (which covers Public administration and official bodies, Education, Proper names, Communications media and new technologies, Culture, and The socioeconomic sphere), Additional Dispositions, and Final Dispositions. So for instance, linguistic rights are granted equally to all language communities under Article 10, and to everyone, the right to use any language of choice in the private and family sphere under Article 12. Other Articles details the right to use or choice of languages in education, public, and legal arenas.

There are a number of other documents on the international level granting linguistic rights. The UN International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, adopted by the UN General Assembly in 1966 makes international law provision for protection of minorities. Article 27 states that individuals of linguistic minorities cannot be denied the right to use their own language.

The UN

was adopted by the UN General Assembly in 1992. Article 4 makes "certain modest obligations on states".

[Extra, G., and Yağmur, K. (2004). "Language rights perspectives". In Extra, G. and Yağmur, K. (Eds.), Urban Multilingualism in Europe: Immigrant Minority Languages at Home and School (pp. 73–92): Multilingual Matters Ltd.] It states that states should provide individuals belonging to minority groups with sufficient opportunities for education in their mother tongue, or instruction with their mother tongue as the medium of instruction. However, this Declaration is non-binding.

A third document adopted by the UN General Assembly in 1989, which makes provisions for linguistic rights is the Convention on the Rights of the Child. In this convention, Articles 29 and 30 declare respect for the child's own cultural identity, language and values, even when those are different from the country of residence, and the right for the child to use his or her own language, in spite of the child's minority or immigrant status.

Regional platform

=Africa

=

Linguistic rights in Africa have only come into focus in recent years. In 1963, the

Organisation of African Unity

The Organisation of African Unity (OAU; , OUA) was an African intergovernmental organization established on 25 May 1963 in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, with 33 signatory governments. Some of the key aims of the OAU were to encourage political and ec ...

(OAU) was formed to help defend the fundamental human rights of all Africans. It adopted in 1981 the

African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights

The African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights (also known as the Banjul Charter) is an international human rights instrument that is intended to promote and protect human rights and basic freedoms in the African continent.

It emerged under ...

, which aims to promote and protect fundamental human rights, including language rights, in Africa. In 2004, fifteen member states ratified the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights Establishing the African Court on Human and Peoples' Rights. The Court is a regional, legal platform that monitors and promotes the AU states' compliance with the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights. It is currently pending a merger with the

Court of Justice of the African Union.

In 2001 the President of the Republic of Mali, in conjunction with the OAU, set up the foundation for the

African Academy of Languages

The African Academy of Languages (ACALAN; ; or ) is a Pan-African organization founded in 2001 by Mali's then-president Alpha Oumar Konaré for the development and promotion of African languages. First established as the Mission for the Africa ...

(ACALAN) to "work for the promotion and harmonisation of languages in Africa". Along with the inauguration of the Interim Governing Board of the ACALAN, the

African Union

The African Union (AU) is a continental union of 55 member states located on the continent of Africa. The AU was announced in the Sirte Declaration in Sirte, Libya, on 9 September 1999, calling for the establishment of the African Union. The b ...

declared 2006 as the

Year of African Languages (YOAL).

In 2002, the OAU was disbanded and replaced by the African Union (AU). The AU adopted the Constitutive Act previously drawn up by the OAU in 2000. In Article 25, it is stated that the working languages of the Union and its institutions are Arabic, English, French and Portuguese, and if possible, all African languages. The AU also recognizes the national languages of each of its member institutions as stated in their national constitutions. In 2003, the AU adopted a protocol amending the Act such that working languages shall be renamed as official languages, and would encompass Spanish, Kiswahili and "any other African language" in addition to the four aforementioned languages . However, this Amendment has yet to be put into force, and the AU continues to use only the four working languages for its publications.

=Europe

=

The

Council of Europe

The Council of Europe (CoE; , CdE) is an international organisation with the goal of upholding human rights, democracy and the Law in Europe, rule of law in Europe. Founded in 1949, it is Europe's oldest intergovernmental organisation, represe ...

adopted the

European Convention on Human Rights

The European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR; formally the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms) is a Supranational law, supranational convention to protect human rights and political freedoms in Europe. Draf ...

in 1950, which makes some reference to linguistic rights. In Article 5.2, reasons for arrest and charges have to be communicated in a language understood by the person. Secondly, Article 6.3 grants an interpreter for free in a court, if the language used cannot be spoken or understood.

The Council for Local and Regional Authorities, part of the Council of Europe, formulated the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages in 1992. This Charter grants recognition, protection, and promotion to regional and/or minority languages in European states, though explicitly not immigrant languages, in domains of "education, judicial authorities, administrative and public services, media, cultural activities, and socio-economic life"

in Articles 8 to 13. Provisions under this Charter are enforced every three years by a committee. States choose which regional and/or minority languages to include.

The Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities was implemented by the Council of Europe in 1995 as a "parallel activity"

to the Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. This Framework makes provisions for the right of national minorities to preserve their language in Article 5, for the encouragement of "mutual respect and understanding and co-operation among all persons living on their territory", regardless of language, especially in "fields of education, culture and the media"

in Article 6. Article 6 also aims to protect persons from discrimination based on language.

Another document adopted by the Council of Europe's Parliamentary Assembly in 1998 is the Recommendation 1383 on Linguistic Diversification. It encourages a wider variety of languages taught in Council of Europe member states in Article 5. It also recommends

language education

Language education refers to the processes and practices of teaching a second language, second or foreign language. Its study reflects interdisciplinarity, interdisciplinary approaches, usually including some applied linguistics. There are f ...

to include languages of non-native groups in Article 8.

Language rights in different countries

Australia

Zuckermann

Zuckermann or Zuckerman is a Yiddish or German surname meaning "sugar man".

Zuckermann

* Ariel Zuckermann (born 1973), Israeli conductor

* Benedict Zuckermann (1818–1891), German scientist

* Ghil'ad Zuckermann (born 1971), Israeli/Italian/Briti ...

et al. (2014) proposed the enactment of "

Native Tongue Title", an ex gratia compensation scheme for the loss of indigenous languages in Australia: "Although some Australian states have enacted ex gratia compensation schemes for the victims of the

Stolen Generations

The Stolen Generations (also known as Stolen Children) were the children of Aboriginal Australians, Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, Torres Strait Islander descent who were removed from their families by the Australian Gover ...

policies, the victims of

linguicide

In linguistics, language death occurs when a language loses its last native speaker. By extension, language extinction is when the language is no longer known, including by second-language speakers, when it becomes known as an extinct language. ...

(language killing) are largely overlooked ... Existing grant schemes to support Aboriginal languages ... should be complemented with compensation schemes, which are based on a claim of right. The proposed compensation scheme for the loss of Aboriginal languages should support the effort to reclaim and revive the lost languages.

On October 11, 2017, the

New South Wales

New South Wales (commonly abbreviated as NSW) is a States and territories of Australia, state on the Eastern states of Australia, east coast of :Australia. It borders Queensland to the north, Victoria (state), Victoria to the south, and South ...

(NSW) parliament passed a legislation that recognises and revives indigenous languages for the first time in Australia's history. "The NSW Government will appoint independent panel of Aboriginal language experts" and "establish languages centres".

Austria

Under the Austrian Constitutional Law (1867), Article 8(2) grants the right to maintenance and development of nationality and language to all ethnic minorities, equal rights to all languages used within the regions in domains of education, administration and public life, as well as the right to education in their own language for ethnic communities, without the necessity of acquiring a second language used in the province.

[Federal Assembly. (2000). Austrian Federal Constitutional Laws (selection).Herausgegeben vom Bundespressedienst.]

Canada

The

Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms

The ''Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms'' (), often simply referred to as the ''Charter'' in Canada, is a bill of rights entrenched in the Constitution of Canada, forming the first part of the '' Constitution Act, 1982''. The ''Char ...

(1982) grants positive linguistic rights, by guaranteeing state responsibility to the French and English language communities. Section 23 declares three types of rights for Canadian citizens speaking French or English as their mother tongue and are minorities in a region.

The first accords right of access to instruction in the medium of the mother tongue. The second assures educational facilities for minority languages. The third endows French and English language minorities the right to maintain and develop their own educational facilities. This control can take the form of "exclusive decision-making authority over the expenditure of funds, the appointment and direction of the administration, instructional programs, the recruitment of teachers and personnel, and the making of agreements for education and services".

[Martel, Angéline. (1999). Heroes, Rebels, Communities and States in Language Rights Activism and Litigation. In Robert Phillipson, Miklós Kontra, ]Tove Skutnabb-Kangas

Tove Anita Skutnabb-Kangas (6 July 1940 – 29 May 2023) was a Finnish linguist and educator. She is known for coining the term linguicism to refer to discrimination based on language.

Life

Skutnabb-Kangas was born in Helsinki, Finland, and ...

, Tibor Várady (Eds.), Language: A Right and a Resource – Approaching Linguistic Human Rights (pp. 47–80). Hungary: Central European University Press. All of these rights apply to primary and secondary education, sustained on public funds, and depend on the numbers and circumstances.

China

Standard Chinese

Standard Chinese ( zh, s=现代标准汉语, t=現代標準漢語, p=Xiàndài biāozhǔn hànyǔ, l=modern standard Han speech) is a modern standard form of Mandarin Chinese that was first codified during the republican era (1912–1949). ...

is

promoted,

which has been seen as damaging to the

varieties of Chinese

There are hundreds of local Chinese language varieties forming a branch of the Sino-Tibetan languages, Sino-Tibetan language family, many of which are not Mutual intelligibility, mutually intelligible. Variation is particularly strong in the m ...

by some of the speakers of those languages.

Efforts to protect the varieties of Chinese have been made.

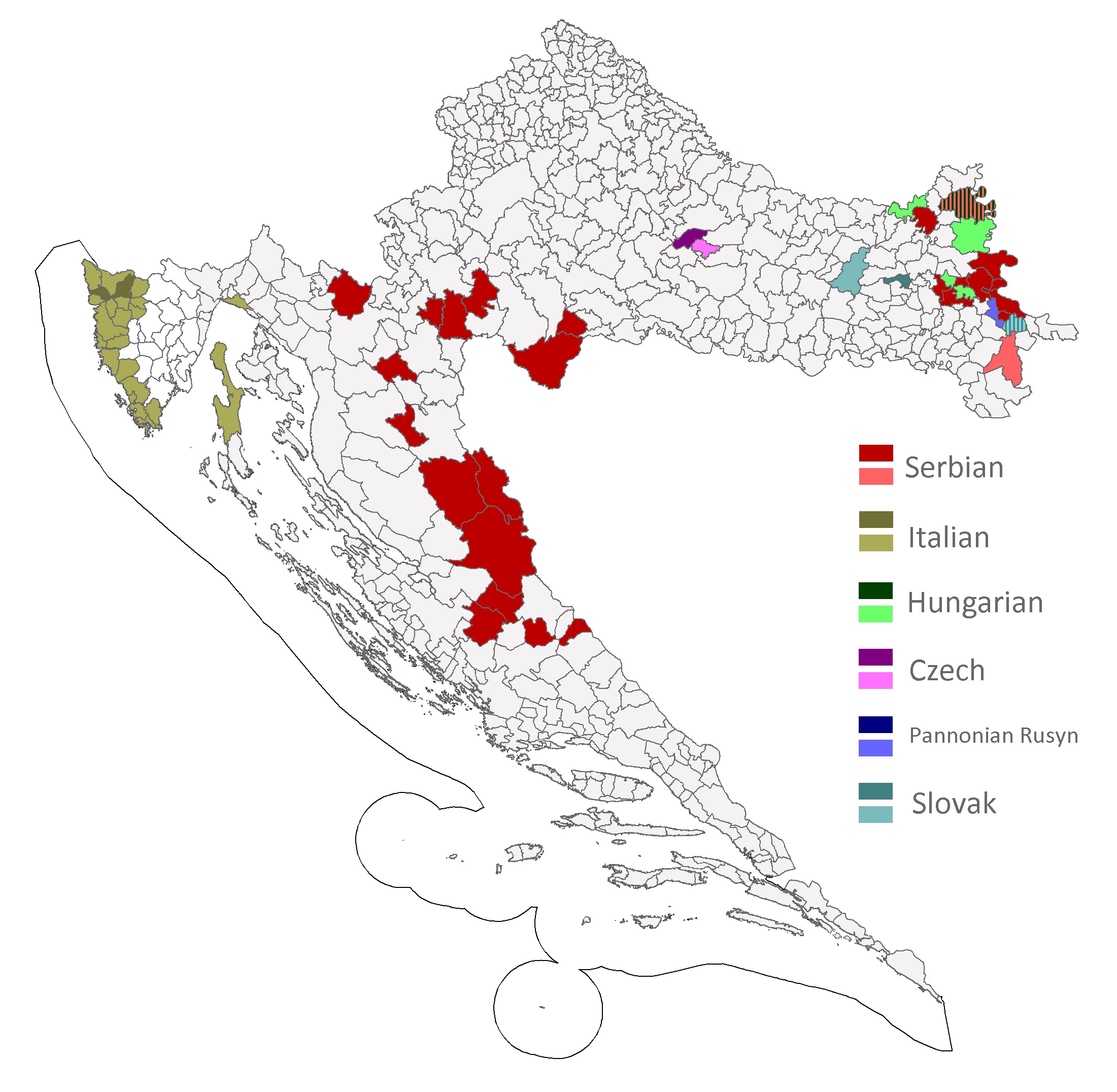

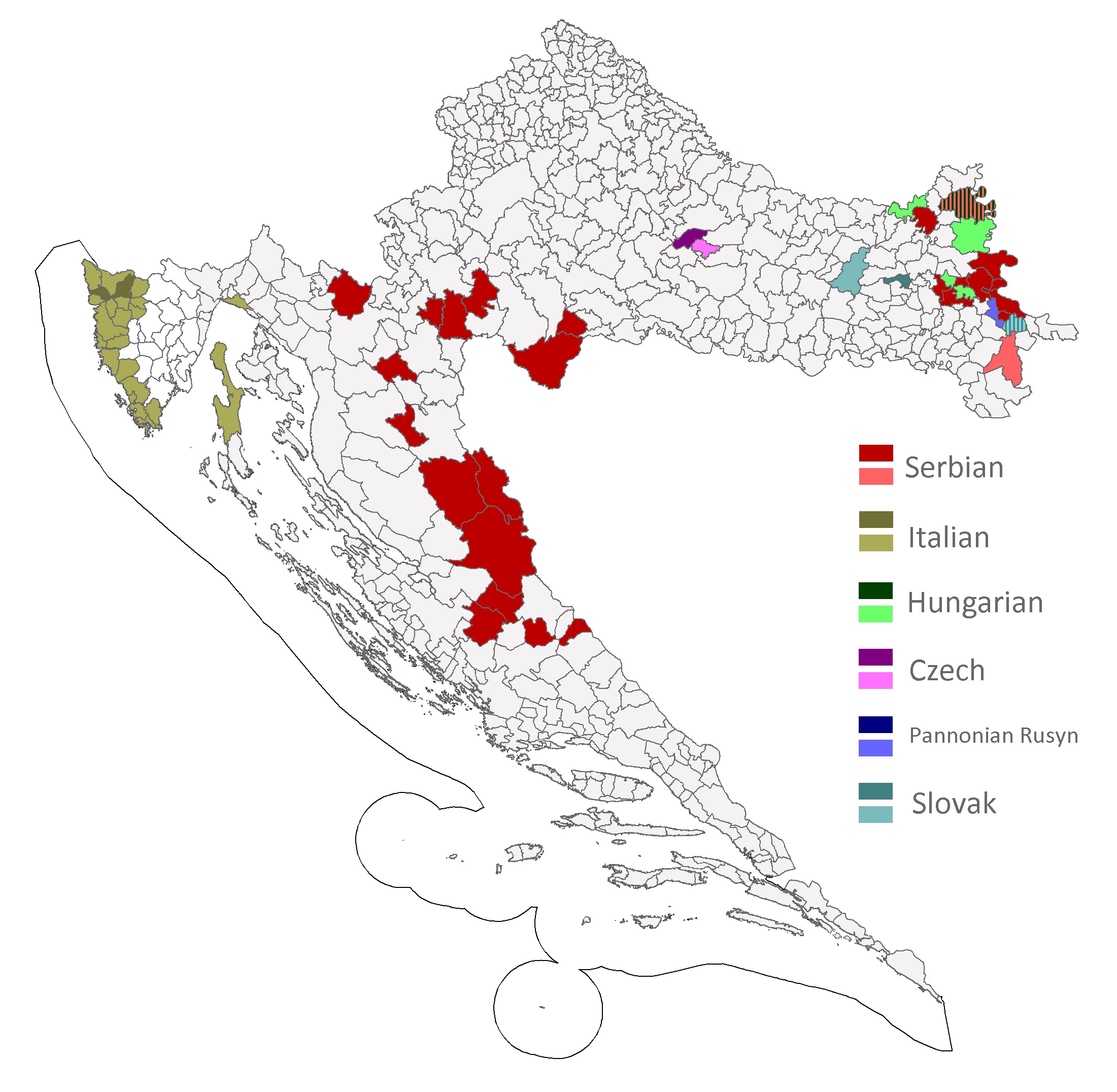

Croatia

Croatian language

Croatian (; ) is the standard language, standardised Variety (linguistics)#Standard varieties, variety of the Serbo-Croatian pluricentric language mainly used by Croats. It is the national official language and literary standard of Croatia, o ...

is stated to be the official language of Croatia in Article 3 of the

Croatian constitution

The Constitution of the Republic of Croatia () is promulgated by the Croatian Parliament.

History

While it was part of the socialist Yugoslavia, the Socialist Republic of Croatia had its own Constitution under the Constitution of Yugoslavia ...

. The same Article of Constitution stipulates that in some of local units, with the Croatian language and

Latin script

The Latin script, also known as the Roman script, is a writing system based on the letters of the classical Latin alphabet, derived from a form of the Greek alphabet which was in use in the ancient Greek city of Cumae in Magna Graecia. The Gree ...

, in official use may be introduced another language or another writing script under the conditions prescribed by law. The only example of the use of minority language at the regional level currently is

Istria County

Istria County (; ; , "Istrian Region") is the westernmost Counties of Croatia, county of Croatia which includes the majority of the Istrian peninsula.

Administrative centers in the county are Pazin, Pula and Poreč. Istria County has the larg ...

where official languages are Croatian and

Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, a Romance ethnic group related to or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance languag ...

. In eastern Croatia, in

Joint Council of Municipalities

The Joint Council of Municipalities in Croatia (; ; abbr. ЗВО, ZVO) is an elected consultative sui generis body which constitutes a form of cultural Self-governance, self-government of Serbs of Croatia, Serbs in the eastern Croatian Podunav ...

, at local (municipal) level is introduced

Serbian

Serbian may refer to:

* Pertaining to Serbia in Southeast Europe; in particular

**Serbs, a South Slavic ethnic group native to the Balkans

** Serbian language

** Serbian culture

**Demographics of Serbia, includes other ethnic groups within the co ...

and its

Cyrillic script

The Cyrillic script ( ) is a writing system used for various languages across Eurasia. It is the designated national script in various Slavic languages, Slavic, Turkic languages, Turkic, Mongolic languages, Mongolic, Uralic languages, Uralic, C ...

as a co-official language. Each municipality, where a certain minority has more than one third of the population, can if it wants to introduce a minority language in official use.

The only currently excluded minority language in the country is

Romani

Romani may refer to:

Ethnic groups

* Romani people, or Roma, an ethnic group of Indo-Aryan origin

** Romani language, an Indo-Aryan macrolanguage of the Romani communities

** Romanichal, Romani subgroup in the United Kingdom

* Romanians (Romanian ...

, a non-territorial language, although the reservation is said to be in a process of withdrawal.

Finland

Finland has one of the most overt linguistic rights frameworks.

Discrimination based on language is forbidden under the basic rights for all citizens in

Finland

Finland, officially the Republic of Finland, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe. It borders Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east, with the Gulf of Bothnia to the west and the Gulf of Finland to the south, ...

. Section 17 of the Constitution of Finland explicitly details the right to one's language and culture, although these languages are stated as either Finnish or Swedish. This right applies to in courts of law and other authorities, as well as translated official documents. There is also overt obligation of the state to provide for the "cultural and societal needs of the Finnish-speaking and Swedish-speaking populations of the country on an equal basis".

[Parliament of Finland. (1999). The Constitution of Finland.] In addition, the Sámi, as an indigenous group, the Roma, and other language communities have the right to maintain and develop their own language. The deaf community is also granted the right to sign language and interpretation or translation. The linguistic rights of the Sámi, the deaf community, and immigrants is further described in separate acts for each group.

Regulations regarding the rights of linguistic minorities in Finland, insist on the forming of a district for the first 9 years of comprehensive school education in each language, in municipalities with both Finnish- and Swedish-speaking children, as long as there is a minimum of 13 students from the language community of that mother tongue.

[Svenska Finlands Folkting. (1991). Vad säger lagarna om språkliga rättigheter (What do the laws say about linguistic rights). Finlandssvensk Rapport nr 16. Helsingfors: Svenska Finlands Folkting.]

India

The constitution of India was first drafted on January 26, 1950. It is estimated that there are about 1500 languages in India. Article 343–345 declared that the official languages of India for communication with centre will be Hindi and English. There are 22 official languages identified by constitution. Article 345 states that "the Legislature of a state may by law adopt any one or more of the languages in use in the State or Hindi as the language or languages to be used for all or any of the official purposes of that State: Provided that, until the Legislature of the State otherwise provides by law, the English language shall continue to be used for those official purposes within the State for which it was being used immediately before the commencement of this Constitution".

Ireland

Language rights in

Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

are recognised in the

Constitution of Ireland

The Constitution of Ireland (, ) is the constitution, fundamental law of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It asserts the national sovereignty of the Irish people. It guarantees certain fundamental rights, along with a popularly elected non-executi ...

and in the Official Languages Act.

Irish is the national and first official language according to the Constitution (with English being a second official language). The Constitution permits the public to conduct its business – and every part of its business – with the state solely through Irish.

On 14 July 2003, the

President of Ireland

The president of Ireland () is the head of state of Republic of Ireland, Ireland and the supreme commander of the Defence Forces (Ireland), Irish Defence Forces. The presidency is a predominantly figurehead, ceremonial institution, serving as ...

signed the

Official Languages Act 2003

The Official Languages Act 2003 () is an Act of the Oireachtas of Ireland. The Act sets out rules regarding use of the Irish language by public bodies; established the office of to monitor and enforce compliance by public bodies with the pro ...

into law and the provisions of the Act were gradually brought into force over a three-year period. The Act sets out the duties of public bodies regarding the provision of services in Irish and the rights of the public to avail of those services.

The use of Irish on the country's traffic signs is the most visible illustration of the state's policy regarding the official languages. It is a statutory requirement that placenames on signs be in both Irish and English except in the

Gaeltacht

A ( , , ) is a district of Ireland, either individually or collectively, where the Irish government recognises that the Irish language is the predominant vernacular, or language of the home.

The districts were first officially recognised ...

, where signs are in Irish only.

Mexico

Language rights were recognized in Mexico in 2003 with the

General Law of Linguistic Rights for the Indigenous Peoples which established a framework for the conservation, nurturing and development of indigenous languages. It recognizes the countries Many indigenous languages as coofficial National languages, and obligates government to offer all public services in indigenous languages.

[Margarita Hidalgo (ed.) . Mexican Indigenous Languages at the Dawn of the Twenty-First Century (Contributions to the Sociology of Language, 91) . 2006 . Berlin , Germany : Mouton de Gruyter] As of 2014 the goal of offering most public services in indigenous languages has not been met.

Pakistan

Pakistan uses English (

Pakistani English

Pakistani English (Paklish, Pinglish, PakEng, en-PK) is a group of English-language varieties spoken in Pakistan and among the Pakistani diaspora. English is the primary language used by the government of Pakistan, alongside Urdu, on the na ...

) and

Urdu

Urdu (; , , ) is an Indo-Aryan languages, Indo-Aryan language spoken chiefly in South Asia. It is the Languages of Pakistan, national language and ''lingua franca'' of Pakistan. In India, it is an Eighth Schedule to the Constitution of Indi ...

as official languages. Although Urdu serves as the national language and lingua franca and is understood by most of the population, it is natively spoken by only 8% of the population. English is not natively used as a first language, but, for official purposes, about 49% of the population is able to communicate in some form of English. However, major regional languages like

Punjabi

Punjabi, or Panjabi, most often refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to Punjab, a region in India and Pakistan

* Punjabi language

* Punjabis, Punjabi people

* Punjabi dialects and languages

Punjabi may also refer to:

* Punjabi (horse), a ...

(spoken by the majority of the population),

Sindhi,

Pashto

Pashto ( , ; , ) is an eastern Iranian language in the Indo-European language family, natively spoken in northwestern Pakistan and southern and eastern Afghanistan. It has official status in Afghanistan and the Pakistani province of Khyb ...

,

Saraiki,

Hindko

Hindko (, , ) is an Indo-Aryan languages, Indo-Aryan language spoken by several million people of various ethnic backgrounds in northwestern Pakistan, primarily in the provinces of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Police, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and northern Pun ...

,

Balochi,

Brahui and

Shina have no official status at the federal level.

Philippines

Article XIV, Sections 6–9 of the 1987 Philippine constitution mandate the following:

:*SECTION 6. The national language of the Philippines is Filipino. As it evolves, it shall be further developed and enriched on the basis of existing Philippine and other languages.

::Subject to provisions of law and as the Congress may deem appropriate, the Government shall take steps to initiate and sustain the use of Filipino as a medium of official communication and as language of instruction in the educational system.

:*SECTION 7. For purposes of communication and instruction, the official languages of the Philippines are Filipino and, until otherwise provided by law, English.

::The regional languages are the auxiliary official languages in the regions and shall serve as auxiliary media of instruction therein.

::Spanish and Arabic shall be promoted on a voluntary and optional basis.

:*SECTION 8. This Constitution shall be promulgated in Filipino and English and shall be translated into major regional languages, Arabic, and Spanish.

:*SECTION 9. The Congress shall establish a national language commission composed of representatives of various regions and disciplines which shall undertake, coordinate, and promote researches for the development, propagation, and preservation of Filipino and other languages.

Spain

The Spanish language is the stated to be the official language of Spain in Article 3 of the Spanish constitution, being the learning of this language compulsory by this same article. However, the constitution makes provisions for other languages of Spain to be official in their respective communities. An example would be the use of the Basque language in the

Basque Autonomous Community (BAC).

Apart from Spanish, the other co-official languages are Basque, Catalan and Galician.

Sweden

In ratifying the

European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages

The European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages (ECRML) is a European treaty (CETS 148) adopted in 1992 under the auspices of the Council of Europe to protect and promote historical regional and minority languages in Europe. However, t ...

, Sweden declared five national minority languages:

Saami

The Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers' Institute (SAAMI, pronounced "Sammy") is an association of American manufacturers of firearms, ammunition, and components. SAAMI is an accredited standards developer that publishes several A ...

,

Finnish,

Meänkieli

(literally 'our language'), or Tornedalian is a Finnic language or a group of distinct Finnish dialects spoken in the northernmost part of Sweden, particularly along the Torne River Valley. It is officially recognized in Sweden as one of the ...

,

Romani

Romani may refer to:

Ethnic groups

* Romani people, or Roma, an ethnic group of Indo-Aryan origin

** Romani language, an Indo-Aryan macrolanguage of the Romani communities

** Romanichal, Romani subgroup in the United Kingdom

* Romanians (Romanian ...

, and

Yiddish

Yiddish, historically Judeo-German, is a West Germanic language historically spoken by Ashkenazi Jews. It originated in 9th-century Central Europe, and provided the nascent Ashkenazi community with a vernacular based on High German fused with ...

.

Romani and Yiddish are non-territorial minority languages in Sweden and thus their speakers were granted more limited rights than speakers of the other three. After a decade of political debate, Sweden declared Swedish the main language of Sweden with its 2009 Language Act.

United States

Language rights in the

United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

are usually derived from the

Fourteenth Amendment, with its Equal Protection and Due Process Clauses, because they forbid racial and ethnic discrimination, allowing language minorities to use this Amendment to claim their language rights.

[Del Valle, Sandra. (2003). "Language Rights and the Law in the United States: Finding our Voices." Multilingual Matters Ltd.] One example of use of the Due Process Clauses is the ''

Meyer v. Nebraska

''Meyer v. Nebraska'', 262 U.S. 390 (1923), was a List of landmark court decisions in the United States, landmark decision by the U.S. Supreme Court, United States Supreme Court that held that the "Siman Act", a 1919 Nebraska law prohibiting min ...

'' case which held that a 1919 Nebraska law restricting foreign-language education violated the Due Process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Two other cases of major importance to linguistic rights were the ''

Yu Cong Eng v. Trinidad'' case, which overturned a language-restrictive legislation in the

Philippines

The Philippines, officially the Republic of the Philippines, is an Archipelagic state, archipelagic country in Southeast Asia. Located in the western Pacific Ocean, it consists of List of islands of the Philippines, 7,641 islands, with a tot ...

, declaring that piece of legislation to be "violative of the Due Process and Equal Protection Clauses of the Philippine Autonomy Act of Congress",

as well as the ''

Farrington v. Tokushige

''Farrington v. Tokushige'', 273 U.S. 284 (1927), was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States unanimously struck down the Territory of Hawaii's law, making it illegal for schools to teach foreign languages without a permit, as it v ...

'' case, which ruled that the governmental regulation of private schools, particularly to restrict the teaching of languages other than English and

Hawaiian, as damaging to the migrant population of

Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; ) is an island U.S. state, state of the United States, in the Pacific Ocean about southwest of the U.S. mainland. One of the two Non-contiguous United States, non-contiguous U.S. states (along with Alaska), it is the only sta ...

. Both of these cases were influenced by the Meyer case, which was a precedent.

Disputes over linguistic rights

Basque, Spain

The linguistic situation for Basque is a precarious one. The Basque language is considered to be a low language in

Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

, where, until about 1982, the Basque language was not used in administration.

[Urla, J. (1988). Ethnic Protest and Social Planning: A Look at Basque Language Revival. Cultural Anthropology , 379–394.] In 1978, a law was passed allowing for Basque to be used in administration side by side with Spanish in the Basque autonomous communities.

Between 1936/39 and 1975, the period of

Franco's régime, the use of Basque was strictly prohibited, and thus language decline begun to occur as well.

[Gardner, N. (2002). BASQUE IN EDUCATION: IN THE BASQUE AUTONOMOUS COMMUNITY. Department of Culture Basque Government. Euskal Autonomia Erkidegoko Administrazioa Hezkuntza, Unibertsitate eta Ikerketa Saila.] However, following the death of Franco, many Basque nationalists demanded that the Basque language be recognized.

One of these groups was Euskadi Ta Askatasun (

ETA

Eta ( ; uppercase , lowercase ; ''ē̂ta'' or ''ita'' ) is the seventh letter of the Greek alphabet, representing the close front unrounded vowel, . Originally denoting the voiceless glottal fricative, , in most dialects of Ancient Greek, it ...

). ETA had initially begun as a nonviolent group to promote Basque language and culture.

However, when its demands were not met, it turned violent and evolved into violent separatist groups. Today, ETA's demands for a separate state stem partially from the problem of perceived linguistic discrimination.

However, ETA called a permanent cease-fire in October 2011.

Faroe Islands

The

Faroese language

Faroese ( ; ) is a North Germanic languages, North Germanic language spoken as a first language by about 69,000 Faroe Islanders, of whom 21,000 reside mainly in Denmark and elsewhere.

It is one of five languages descended from Old Norse#Old West ...

conflict, which occurred roughly between 1908 and 1938, has been described as political and cultural in nature. The two languages competing to become the official language of the Faroe Islands were Faroese and Danish. In the late 19th and early 20th century, the language of the government, education and Church was Danish, whereas Faroese was the language of the people. The movement towards Faroese language rights and preservation was begun in the 1880s by a group of students. This spread from 1920 onwards to a movement towards using Faroese in the religious and government sector. Faroese and Danish are now both official languages in the Faroe Islands.

Nepal

The

Newar

Newar (; , endonym: Newa; , Pracalit script: ), or Nepami, are primarily inhabitants in Kathmandu Valley of Nepal and its surrounding areas, and the creators of its historic heritage and civilisation. Page 15. Newars are a distinct linguisti ...

s of

Nepal

Nepal, officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal, is a landlocked country in South Asia. It is mainly situated in the Himalayas, but also includes parts of the Indo-Gangetic Plain. It borders the Tibet Autonomous Region of China Ch ...

have been struggling to save their

Nepal Bhasa

Newar (; , ) is a Sino-Tibetan language spoken by the Newar people, the indigenous inhabitants of Nepal Mandala, which consists of the Kathmandu Valley and surrounding regions in Nepal. The language is known officially in Nepal as Nepal Bhas ...

language, culture and identity since the 1920s. Nepal Bhasa was suppressed during the

Rana

Rana may refer to:

Astronomy

* Rana (crater), a crater on Mars

* Delta Eridani or Rana, a star

Films

* Rana (2012 film), an Indian Kannada-language action drama

* Rana, a 1998 Telugu-language action film directed by A. Kodandarami Reddy

* R ...

(1846–1951) and

Panchayat (1960–1990) regimes leading to language decline. The Ranas forbade writing in Nepal Bhasa and authors were jailed or exiled. Beginning in 1965, the Panchayat system eased out regional languages from the radio and educational institutions, and protestors were put in prison.

After the reinstatement of democracy in 1990, restrictions on publishing were relaxed; but attempts to gain usage in local state entities side by side with

Nepali failed. On 1 June 1999, the Supreme Court forbade

Kathmandu

Kathmandu () is the capital and largest city of Nepal, situated in the central part of the country within the Kathmandu Valley. As per the 2021 Nepal census, it has a population of 845,767 residing in 105,649 households, with approximately 4 mi ...

Metropolitan City from giving official recognition to Nepal Bhasa, and

Rajbiraj

Rajbiraj () is a mid-sized municipality located in the south-eastern part of Madhesh Province of Nepal. The city is also called the "Pink City of Nepal" because the township was designed in 1938 based on influence from the "Indian Pink City" Ja ...

Municipality and

Dhanusa District Development Committee from recognizing

Maithili.

The Interim Constitution of Nepal 2007 recognizes all the languages spoken as mother tongues in Nepal as the national languages of Nepal. It says that Nepali in

Devanagari

Devanagari ( ; in script: , , ) is an Indic script used in the Indian subcontinent. It is a left-to-right abugida (a type of segmental Writing systems#Segmental systems: alphabets, writing system), based on the ancient ''Brāhmī script, Brā ...

script shall be the language of official business, however, the use of mother tongues in local bodies or offices shall not be considered a barrier. The use of national languages in local government bodies has not happened in practice, and discouragement in their use and discrimination in allocation of resources persist. Some analysts have stated that one of the chief causes of the Maoist insurgency, or the

Nepalese Civil War

The Nepalese Civil War was a protracted armed conflict that took place in the then Kingdom of Nepal from 1996 to 2006. It saw countrywide fighting between the Kingdom rulers and the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist), with the latter making ...

(1996–2006), was the denial of language rights and marginalization of ethnic groups.

Sri Lanka

The start of the conflict regarding languages in

Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka, officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, also known historically as Ceylon, is an island country in South Asia. It lies in the Indian Ocean, southwest of the Bay of Bengal, separated from the Indian subcontinent, ...

goes as far back as the rule of the British. During the colonial period, English had a special and powerful position in Sri Lanka. The British ruled in Sri Lanka from the late eighteenth century to 1948. English was the official language of administration then. Just before the departure of the British, a "swabhasha" (your own language) movement was launched in a bid to phase out English slowly, replacing it with

Sinhala or

Tamil

Tamil may refer to:

People, culture and language

* Tamils, an ethno-linguistic group native to India, Sri Lanka, and some other parts of Asia

**Sri Lankan Tamils, Tamil people native to Sri Lanka

** Myanmar or Burmese Tamils, Tamil people of Ind ...

. However, shortly after the departure of the British the campaign, for various political reasons, evolved from advocating Sinhala and Tamil replacing English to just Sinhala replacing English.

In 1956, the first election after independence, the opposition won and the official language was declared to be Sinhala. The Tamil people were unhappy, feeling that they were greatly disadvantaged. Because Sinhala was now the official language, it made it easier for the people whose mother tongue was Sinhala to enter into government sector and also provided them with an unfair advantage in the education system. Tamils who also did not understand Sinhala felt greatly inconvenienced as they had to depend on others to translate official documents for them.

Both the Tamil and Sinhala-speaking people felt that language was crucial to their identity. The Sinhala people associated the language with their rich heritage. They were also afraid that, given that there were only 9 million speakers of the language at that time, if Sinhala was not the only official language it would eventually be slowly lost.

The Tamil people felt that the Sinhala-only policy would assert the dominance of the Sinhalese people and as such they might lose their language, culture and identity.

Despite the unhappiness of the Tamil people, no big political movement was undertaken till the early 1970s. Eventually in May 1976, there was a public demand for a Tamil state. During the 1956 election the Federal party had replaced the Tamil congress. The party was bent on "the attainment of freedom for the Tamil-speaking people of Ceylon by the establishment of an autonomous Tamil state on the linguistic basis within the framework of a Federal Union of Ceylon".

However it did not have much success. Thus in 1972, the Federal Party, Tamil Congress and other organizations banded together into a new party called the "Tamil United Front".

One of the catalysts for Tamil separation arose in 1972 when the Sinhala government made amendments to the constitution. The Sinhala government decided to promote Buddhism as the official religion, claiming that "it shall be the duty of the State to protect and foster Buddhism".

Given that the majority of the Tamils were Hindus, this created unease. There was then a fear among the Tamils that people belonging to the "untouchable castes" would be encouraged to convert to Buddhism and then "brainwashed" to learn Sinhala as well.

Another spur was also the impatience of Tamil youth in Sri Lanka. Veteran politicians noted that current youths were more ready to engage in violence, and some of them even had ties to certain rebel groups in South India. Also in 1974, there was conference of Tamil studies organized in

Jaffna

Jaffna (, ; , ) is the capital city of the Northern Province, Sri Lanka, Northern Province of Sri Lanka. It is the administrative headquarters of the Jaffna District located on a Jaffna Peninsula, peninsula of the same name. With a population o ...

. The conference turned violent. This resulted in the deaths of seven people. Consequently, about 40 – 50 Tamil youths in between the years of 1972 and 1975 were detained without being properly charged, further increasing tension.

A third stimulus was the changes in the criteria for University examinations in the early 1970s. The government decided that they wanted to standardize the university admission criteria, based on the language the entrance exams were taken in. It was noted that students who took the exams in Tamil scored better than the students who took it in Sinhala. Thus the government decided that Tamil students had to achieve a higher score than the students who took the exam in Sinhala to enter the universities. As a result, the number of Tamil students entering universities fell.

After the July 1977 election, relations between the Sinhalese and the Ceylon Tamil people became worse. There was flash violence in parts of the country. It is estimated about 100 people were killed and thousands of people fled from their homes. Among all these tensions, the call for a separate state among Tamil people grew louder.

[Kearney, R. (1978). Language and the Rise of Tamil Separatism in Sri Lanka. Asian Survey, 18(5), 521–534.]

Quebec, Canada

In

Quebec

Quebec is Canada's List of Canadian provinces and territories by area, largest province by area. Located in Central Canada, the province shares borders with the provinces of Ontario to the west, Newfoundland and Labrador to the northeast, ...

, the Charter of the French Language (Bill 101) declares French as the province’s official language, impacting government, commerce, and education. It aims to promote French while protecting indigenous languages. However, it has sparked controversy, particularly among

anglophones

The English-speaking world comprises the 88 countries and territories in which English is an official, administrative, or cultural language. In the early 2000s, between one and two billion people spoke English, making it the largest language ...

and businesses, over restrictions on English usage, leading to amendments and legal challenges since its introduction in 1977. The most recent modification is Bill 96 (2022), which strengthens the role of French in various sectors.

"Quebec Language"

''The Canadian Encyclopedia'' May 19, 2008

See also

*''Ballantyne, Davidson, McIntyre v. Canada

''Ballantyne, Davidson, McIntyre v. Canada'' (Communications Nos. 359/1989 and 385/1989) was a case on Quebec's language law submitted in 1989 and decided by the Human Rights Committee of the United Nations in 1993.

Facts

Three English-speaking Q ...

''

* Belgian linguistic case

*'' Diergaardt v. Namibia''

*Freedom of speech

Freedom of speech is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or a community to articulate their opinions and ideas without fear of retaliation, censorship, or legal sanction. The rights, right to freedom of expression has been r ...

*International Mother Language Day

International Mother Language Day is a worldwide annual observance held on 21 February to promote awareness of linguistic and cultural diversity and to promote multilingualism. First announced by UNESCO on 17 November 1999, it was formally reco ...

*Language geography

Language geography is the branch of human geography that studies the geographic distribution of language(s) or its constituent elements. Linguistic geography can also refer to studies of how people talk about the landscape. For example, toponym ...

*Language ideology

Language ideology (also known as linguistic ideology) is, within anthropology (especially linguistic anthropology), sociolinguistics, and cross-cultural studies, any set of beliefs about languages as they are used in their social worlds. Langua ...

*Language policy

Language policy is both an interdisciplinary academic field and implementation of ideas about language use.

Some scholars such as Joshua Fishman and Ofelia García consider it as part of sociolinguistics. On the other hand, other scholars such as ...

*'' Lau v. Nichols''

*Legal recognition of sign languages

The legal recognition of signed languages differs widely. In some jurisdictions (countries, states, provinces or regions), a signed language is recognised as an official language; in others, it has a protected status in certain areas (such as educ ...

*Linguistic ecology

Linguistic ecology or language ecology is the study of how languages interact with each other and the places they are spoken in, and frequently argues for the preservation of endangered languages as an analogy of the preservation of biological spec ...

* Yukio Tsuda (professor)

* Minae Mizumura

*Linguistic purism

Linguistic purism or linguistic protectionism is a concept with two common meanings: one with respect to foreign languages and the other with respect to the internal variants of a language (dialects).

The first meaning is the historical trend ...

* List of linguistic rights in African constitutions

* List of linguistic rights in European constitutions

*List of multilingual countries and regions

This is an incomplete list of areas with either multilingualism at the community level or at the personal level.

There is a distinction between social and personal bilingualism. Many countries, such as Belarus, Belgium, Canada, Finland, India, ...

*Minoritized language

In sociolinguistics, a minoritized language is a language that is marginalized, persecuted, or banned. Language minoritization stems from the tendency of large nations to establish a common language for commerce and government, or to establish ...

s

*Minority language

A minority language is a language spoken by a minority of the population of a territory. Such people are termed linguistic minorities or language minorities. With a total number of 196 sovereign states recognized internationally (as of 2019) and ...

*Multilingualism

Multilingualism is the use of more than one language, either by an individual speaker or by a group of speakers. When the languages are just two, it is usually called bilingualism. It is believed that multilingual speakers outnumber monolin ...

*Raciolinguistics

Raciolinguistics examines how language is used to construct race and how ideas of race influence language and language use. Although sociolinguists and linguistic anthropologists have previously studied the intersections of language, race, and cul ...

*''R. v. Beaulac

''R v Beaulac'' 9991 S.C.R. 768 is a decision by the Supreme Court of Canada on language rights. Notably, the majority adopted a liberal and purposive interpretation of language rights in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, overturning co ...

''

*Territorial principle

The territorial principle (also territoriality principle) is a principle of public international law which enables a sovereign state to exercise exclusive jurisdiction over individuals and other legal persons within its territory. It includes both ...

References

Sources

* May, S. (2012) ''Language and Minority Rights: Ethnicity, nationalism and the politics of language'', New York: Routledge.

* Skutnabb-Kangas, T. & Phillipson, R.,

Linguistic Human Rights: Overcoming Linguistic Discrimination

', Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 1994.

* Faingold, E. D. (2004). "Language rights and language justice in the constitutions of the world." ''Language Problems & Language Planning'' 28(1): 11–24.

* Alexander, N. 2002. Linguistic rights, language planning and democracy in post- apartheid South Africa. In Baker, S. (ed.), ''Language Policy: Lessons from Global Models''. Monterey, CA.: Monterey Institute of International Studies.

* Hult, F.M. (2004). Planning for multilingualism and minority language rights in Sweden. ''Language Policy'', 3(2), 181–201.

*Bamgbose, A. 2000. ''Language and Exclusion''. Hamburg: LIT-Verlag.

*Myers-Scotton, C. 1990. Elite closure as boundary maintenance. The case of Africa. In B. Weinstein (ed.), ''Language Policy and Political Development''. Norwood, NJ.: Ablex Publishing Corporation.

*Tollefson, J. 1991. ''Planning Language, Planning Inequality. Language Policy in the Community''. Longman: London and New York.

*Miller D, Branson J (2002). Nationalism and the Linguistic Rights of Deaf Communities: Linguistic Imperialism and the Recognition and Development of Sign Languages. ''Journal of Sociolinguistics''. 2(1), 3–34.

*Asbjorn, Eide (1999). The Oslo Recommendations regarding the Linguistic Rights of National Minorities: An Overview. ''International Journal on Minority and Group Rights'', 319–328. ISSN 1385-4879

*Woehrling, J (1999). Minority Cultural and Linguistic Rights and Equality Rights in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. ''McGill Law Journal''.