Lewisian complex on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Lewisian complex or Lewisian gneiss is a suite of

The main outcrops of the Lewisian complex are on the islands of the

The main outcrops of the Lewisian complex are on the islands of the

''Sea of the Hebrides''. Eds. P.Saundry & C.J.Cleveland. Encyclopedia of Earth. National Council for Science and the Environment. Washington DC

/ref> Basement rocks of similar type are found at the base of both the Morar Group and the overlying Loch Ness Supergroup, sometimes with well-preserved unconformable contacts, and these are generally accepted as forming part of the Lewisian, suggesting that the Lewisian complex extends at least as far southeast as the Great Glen Fault. Lewisian-like granitic gneisses of Paleoproterozoic age of the Rhinns complex are exposed on

Rocks of NW Scotland

at Oxford Earth Sciences:

Geology of Scotland Hebrides Gneiss

Precambrian

The Precambrian ( ; or pre-Cambrian, sometimes abbreviated pC, or Cryptozoic) is the earliest part of Earth's history, set before the current Phanerozoic Eon. The Precambrian is so named because it preceded the Cambrian, the first period of t ...

metamorphic rock

Metamorphic rocks arise from the transformation of existing rock to new types of rock in a process called metamorphism. The original rock ( protolith) is subjected to temperatures greater than and, often, elevated pressure of or more, caus ...

s that outcrop

An outcrop or rocky outcrop is a visible exposure of bedrock or ancient superficial deposits on the surface of the Earth and other terrestrial planets.

Features

Outcrops do not cover the majority of the Earth's land surface because in most p ...

in the northwestern part of Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

, forming part of the Hebridean terrane

The Hebridean terrane is one of the terranes that form part of the Caledonian orogenic belt in northwest Scotland. Its boundary with the neighbouring Northern Highland terrane is formed by the Moine Thrust Belt. The basement is formed by Archa ...

and the North Atlantic Craton. These rocks are of Archaean and Paleoproterozoic

The Paleoproterozoic Era (also spelled Palaeoproterozoic) is the first of the three sub-divisions ( eras) of the Proterozoic eon, and also the longest era of the Earth's geological history, spanning from (2.5–1.6 Ga). It is further sub ...

age, ranging from 3.0–1.7 billion years ( Ga). They form the basement

A basement is any Storey, floor of a building that is not above the grade plane. Especially in residential buildings, it often is used as a utility space for a building, where such items as the Furnace (house heating), furnace, water heating, ...

on which the Stoer Group, Wester Ross Supergroup and probably the Loch Ness Supergroup sediments were deposited. The Lewisian consists mainly of granitic

A granitoid is a broad term referring to a diverse group of coarse-grained igneous rocks that are widely distributed across the globe, covering a significant portion of the Earth's exposed surface and constituting a large part of the continental ...

gneiss

Gneiss (pronounced ) is a common and widely distributed type of metamorphic rock. It is formed by high-temperature and high-pressure metamorphic processes acting on formations composed of igneous or sedimentary rocks. This rock is formed under p ...

es with a minor amount of supracrustal rocks. Rocks of the Lewisian complex were caught up in the Caledonian orogeny

The Caledonian orogeny was a mountain-building cycle recorded in the northern parts of the British Isles, the Scandinavian Caledonides, Svalbard, eastern Greenland and parts of north-central Europe. The Caledonian orogeny encompasses events tha ...

, appearing in the hanging walls of many of the thrust fault

A thrust fault is a break in the Earth's crust, across which older rocks are pushed above younger rocks.

Thrust geometry and nomenclature

Reverse faults

A thrust fault is a type of reverse fault that has a dip of 45 degrees or less.

I ...

s formed during the late stages of this tectonic event.

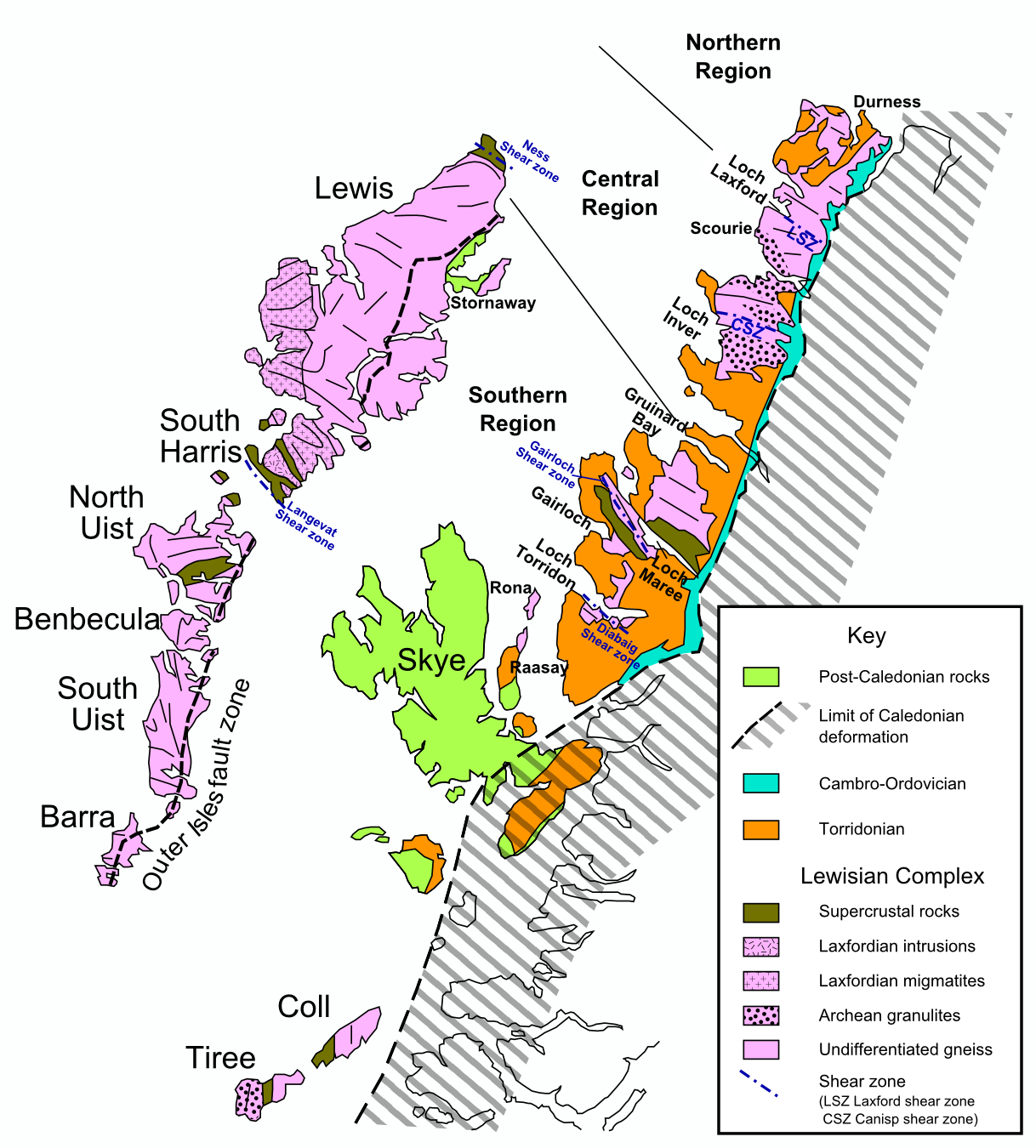

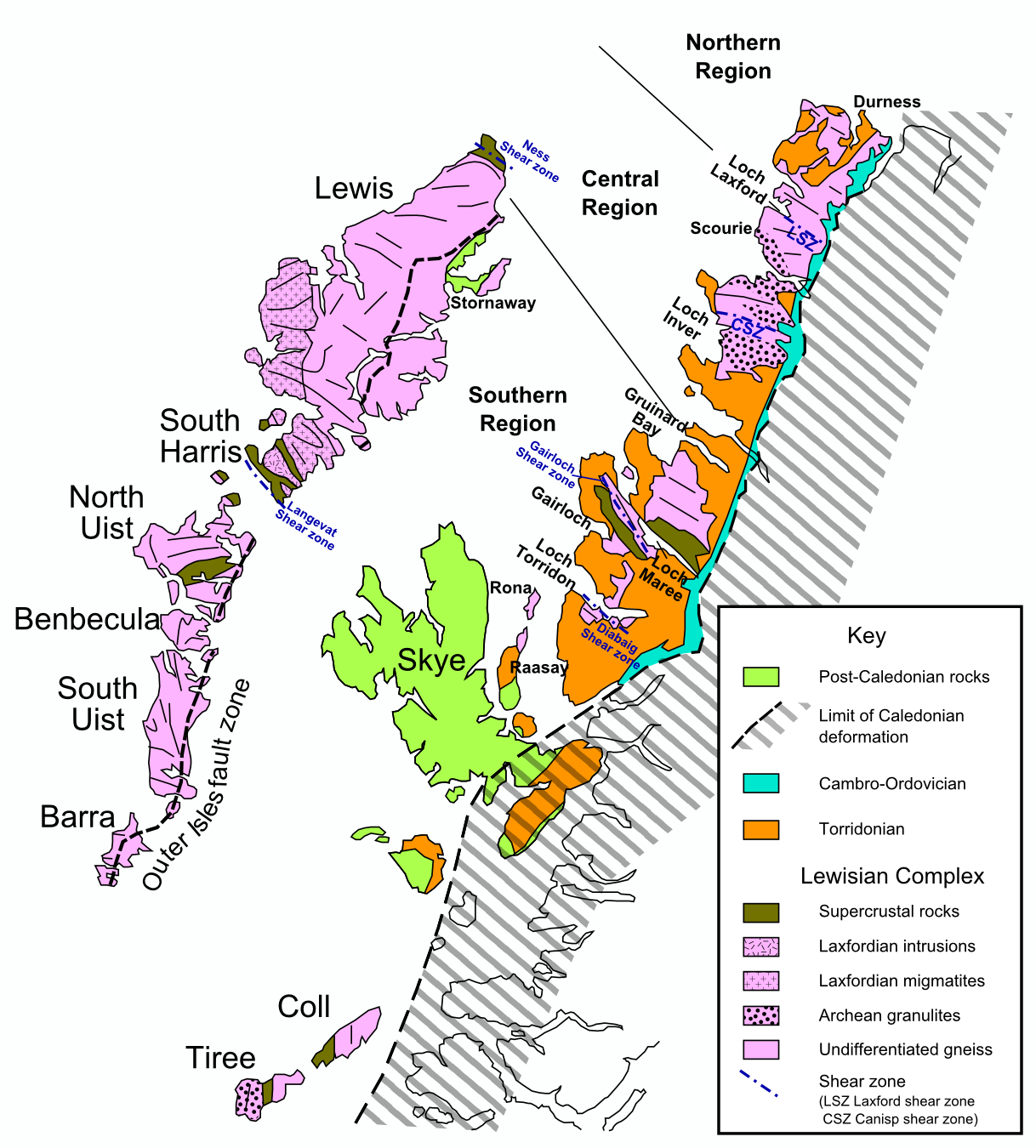

Distribution

The main outcrops of the Lewisian complex are on the islands of the

The main outcrops of the Lewisian complex are on the islands of the Outer Hebrides

The Outer Hebrides ( ) or Western Isles ( , or ), sometimes known as the Long Isle or Long Island (), is an Archipelago, island chain off the west coast of mainland Scotland.

It is the longest archipelago in the British Isles. The islan ...

, including Lewis, from which the complex takes its name. It is also exposed on several islands of the Inner Hebrides

The Inner Hebrides ( ; ) is an archipelago off the west coast of mainland Scotland, to the south east of the Outer Hebrides. Together these two island chains form the Hebrides, which experience a mild oceanic climate. The Inner Hebrides compri ...

, small islands north of the Scottish mainland and forms a coastal strip on the mainland from near Loch Torridon

Loch Torridon () is a sea loch on the west coast of Scotland in the Northwest Highlands. The loch was created by glacial processes and is in total around 15 miles (25 km) long. It has two sections: Upper Loch Torridon to landward, east of Ru ...

in the south to Cape Wrath

Cape Wrath (, known as ' in Lewis) is a cape in the Durness parish of the county of Sutherland in the Highlands of Scotland. It is the most north-westerly point in Great Britain.

The cape is separated from the rest of the mainland by the Ky ...

in the north. Its presence at seabed and beneath Paleozoic and Mesozoic sediments west of Shetland

Shetland (until 1975 spelled Zetland), also called the Shetland Islands, is an archipelago in Scotland lying between Orkney, the Faroe Islands, and Norway, marking the northernmost region of the United Kingdom. The islands lie about to the ...

and in the Minches and Sea of the Hebrides

The Sea of the Hebrides (, ) is a small and partly sheltered section of the North Atlantic Ocean, indirectly off the southern part of the north-west coast of Scotland. To the east are the mainland of Scotland and the northern Inner Hebrides (i ...

has been confirmed from the magnetic field, by shallow boreholes and hydrocarbon exploration

Hydrocarbon exploration (or oil and gas exploration) is the search by petroleum geologists and geophysicists for hydrocarbon deposits, particularly petroleum and natural gas, in the Earth's crust using petroleum geology.

Exploration methods

...

wells.C.Michael Hogan. 2011''Sea of the Hebrides''. Eds. P.Saundry & C.J.Cleveland. Encyclopedia of Earth. National Council for Science and the Environment. Washington DC

/ref> Basement rocks of similar type are found at the base of both the Morar Group and the overlying Loch Ness Supergroup, sometimes with well-preserved unconformable contacts, and these are generally accepted as forming part of the Lewisian, suggesting that the Lewisian complex extends at least as far southeast as the Great Glen Fault. Lewisian-like granitic gneisses of Paleoproterozoic age of the Rhinns complex are exposed on

Islay

Islay ( ; , ) is the southernmost island of the Inner Hebrides of Scotland. Known as "The Queen of the Hebrides", it lies in Argyll and Bute just south west of Jura, Scotland, Jura and around north of the Northern Irish coast. The island's cap ...

and Colonsay

Colonsay (; ; ) is an island in the Inner Hebrides of Scotland, located north of Islay and south of Isle of Mull, Mull. The ancestral home of Clan Macfie and the Colonsay branch of Clan MacNeil, it is in the council area of Argyll and Bute and ...

in the southern part of the Inner Hebrides. Similar rocks also outcrop on Inishtrahull off the north coast of County Donegal

County Donegal ( ; ) is a Counties of Ireland, county of the Republic of Ireland. It is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Ulster and is the northernmost county of Ireland. The county mostly borders Northern Ireland, sharing only a small b ...

and in County Mayo

County Mayo (; ) is a Counties of Ireland, county in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. In the West Region, Ireland, West of Ireland, in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Connacht, it is named after the village of Mayo, County Mayo, Mayo, now ge ...

where they are known as the 'Annagh Gneiss complex'.

History of study

The first comprehensive account of the Lewisian complex was published in 1907 as part of the Geological Survey memoir '' The Geological Structure of the North-West Highlands of Scotland''. In 1951 John Sutton and Janet Watson built on this work by interpreting the metamorphic and structural development of the Lewisian as a series of discrete orogenic events that could be discerned in the field. They used a swarm of dolerite dykes, known as the Scourie dykes, as markers to separate the tectonic and metamorphic events into a Scourian event that occurred before the intrusion of the dykes and a later Laxfordian event that deformed and metamorphosed members of the same dyke swarm. Subsequent fieldwork, metamorphic studies and radiometric dating has refined their chronology but supported their original hypothesis.Lewisian of the Scottish mainland

Scourie complex

The oldest part of the Lewisian complex is a group of gneisses of Archaean age that formed in the interval 3.0–2.7 Ga. These gneisses are found throughout the outcrop of the Lewisian complex in the mainland. The dominant lithology of the Scourie complex is banded grey gneisses, typically granodioritic, tonalitic or trondhjemitic in composition.Metasediment

In geology, metasedimentary rock is a type of metamorphic rock. Such a rock was first formed through the deposition and solidification of sediment

Sediment is a solid material that is transported to a new location where it is deposited. It occu ...

ary gneisses are relatively rare. The protolith

A protolith () is the original, unmetamorphosed rock from which a given metamorphic rock is formed.

For example, the protolith of a slate is a shale or mudstone. Metamorphic rocks can be derived from any other kind of non-metamorphic rock and ...

for the Scourian gneisses are thought to be granitic, with subsidiary mafic and ultramafic plutonic rocks giving an overall bimodal character. Some variation in the age of the protoliths from different parts of the complex and their subsequent tectonic and metamorphic history suggest that there are two or possibly three distinct crustal blocks within the mainland outcrop.

The main metamorphic event in the Central Region was the 2.5 Ga granulite facies Badcallian event. The Northern Region lacks evidence of granulite facies and in the Southern Region an earlier 2.73 Ga event is recognised locally.

Inverian event

This tectonic and metamorphic event postdates the main granulite facies metamorphic event in the Scourian complex but mostly predates intrusion of the Scourie dykes. This event deforms a suite of post-Badcallianpegmatite

A pegmatite is an igneous rock showing a very coarse texture, with large interlocking crystals usually greater in size than and sometimes greater than . Most pegmatites are composed of quartz, feldspar, and mica, having a similar silicic c ...

s dated at 2.49-2.48 Ga and predates most of the Scourie dykes, giving a possible age range of approximately 2.48 - 2.42 Ga. The deformation was accompanied by retrograde metamorphism down to amphibolite facies, similar to the later Laxfordian event. Distinguishing between these two events has proved difficult. Major Inverian shear zones have been identified in the Central and Southern Regions, including the Canisp Shear Zone.

Scourie dykes

This basic dyke swarm cuts the banding of the Scourie complex gneisses and therefore postdates the main igneous, tectonic and metamorphic events that created them. Due to the degree of later metamorphism and deformation in other parts of the mainland outcrop, the only reliableradiometric

Radiometry is a set of techniques for measuring electromagnetic radiation, including visible light. Radiometric techniques in optics characterize the distribution of the radiation's power in space, as opposed to photometric techniques, which ch ...

ages come from the Central Region, giving an age for the main part of the swarm as about 2.4 Ga. Some dykes, which appear to have been intruded into cooler Scourian crust give ages of about 2.0 Ga, the same age as undated sills within the Loch Maree Group. Some of the main dyke suite show evidence of intrusion into hot country rock

Country rock is a music genre that fuses rock and country. It was developed by rock musicians who began to record country-flavored records in the late 1960s and early 1970s. These musicians recorded rock records using country themes, vocal sty ...

. Most of the dykes are quartz-dolerite

Quartz dolerite or quartz diabase is an intrusive rock similar to dolerite (also called diabase), but with an excess of quartz. Dolerite is similar in composition to basalt, which is volcanic, and gabbro, which is plutonic. The differing crystal ...

s in terms of chemistry, with less common olivine

The mineral olivine () is a magnesium iron Silicate minerals, silicate with the chemical formula . It is a type of Nesosilicates, nesosilicate or orthosilicate. The primary component of the Earth's upper mantle (Earth), upper mantle, it is a com ...

gabbro

Gabbro ( ) is a phaneritic (coarse-grained and magnesium- and iron-rich), mafic intrusive igneous rock formed from the slow cooling magma into a holocrystalline mass deep beneath the Earth's surface. Slow-cooling, coarse-grained gabbro is ch ...

, norite

Norite is a mafic Intrusive rock, intrusive igneous rock composed largely of the calcium-rich plagioclase labradorite, orthopyroxene, and olivine. The name ''norite'' is derived from Norway, by its Norwegian name ''Norge''.

Norite, also known ...

and bronzite picrite

Picrite basalt or picrobasalt is a variety of high-magnesium olivine basalt that is very rich in the mineral olivine. It is dark with yellow-green olivine phenocrysts (20-50%) and black to dark brown pyroxene, mostly augite.

The olivine-rich ...

.

The Loch Maree Group

Supracrustal rocks of the Loch Maree Group form two large areas of outcrop nearLoch Maree

Loch Maree () is a loch in Wester Ross in the Northwest Highlands of Scotland. At long and with a maximum width of , it is the fourth-largest freshwater loch in Scotland; it is the largest north of Loch Ness. Its surface area is .

Loch Maree c ...

and Gairloch

Gairloch ( ; , meaning "Short Loch") is a village, civil parish and community on the shores of Loch Gairloch in Wester Ross, in the North-West Highlands of Scotland. A tourist destination in the summer months, Gairloch has a golf course, a ...

in the Southern Region. The group consists of metasediments with intercalated amphibolite

Amphibolite () is a metamorphic rock that contains amphibole, especially hornblende and actinolite, as well as plagioclase feldspar, but with little or no quartz. It is typically dark-colored and dense, with a weakly foliated or schistose ...

s, interpreted to be metavolcanics with some basic sills. They were probably deposited at about 2.0 Ga, as they contain detrital zircon

Zircon () is a mineral belonging to the group of nesosilicates and is a source of the metal zirconium. Its chemical name is zirconium(IV) silicate, and its corresponding chemical formula is Zr SiO4. An empirical formula showing some of th ...

s that give a mixture of Archaean and Paleoproterozoic ages.

Laxfordian events

The Laxfordian was originally recognised from the presence of deformation and metamorphism of the Scourie dykes. The Laxfordian can be divided into an early event before 1.7 Ga, associated with retrogression of the Scourie gneisses from granulite to amphibolite facies and a later event with local further retrogression togreenschist

Greenschists are metamorphic rocks that formed under the lowest temperatures and pressures usually produced by regional metamorphism, typically and 2–10 kilobars (). Greenschists commonly have an abundance of green minerals such as Chlorite ...

facies, part of which may be Grenvillian in age (about 1.1Ga). The early event is particularly associated with shear zones in which the deformed Scourie dykes form amphibolite sheets within the reworked gneisses. The original mineralogy of the dykes is also changed to an amphibolite facies assemblage, even where they remain undeformed. The early Laxfordian fabrics

Textile is an umbrella term that includes various fiber-based materials, including fibers, yarns, filaments, threads, and different types of fabric. At first, the word "textiles" only referred to woven fabrics. However, weaving is not ...

are cut by a series of granites and pegmatite

A pegmatite is an igneous rock showing a very coarse texture, with large interlocking crystals usually greater in size than and sometimes greater than . Most pegmatites are composed of quartz, feldspar, and mica, having a similar silicic c ...

s, particularly in the Northern and Southern Regions dated at 1.7 Ga.

Lewisian of the Outer Hebrides

Much of the Lewisian outcrop of the Outer Hebrides consist of rocks of the Scourie complex cut by post-Scourian granites. Laxfordian reworking is extensive and very little unmodified Scourian crust has survived. Amphibolite sheets, interpreted to be deformed members of the Scourie Dykes, are much less common than on the mainland. More of the outcrop area consists of supracrustal rocks, about 5% of the total. The relationship between the supreacrustal rocks and the Scourian gneisses remains unclear.South Harris igneous complex

The South Harris igneous complex consists mainly ofanorthosite

Anorthosite () is a phaneritic, intrusive rock, intrusive igneous rock characterized by its composition: mostly plagioclase feldspar (90–100%), with a minimal mafic component (0–10%). Pyroxene, ilmenite, magnetite, and olivine are the mafic ...

and metagabbro, with lesser amounts of tonalitic and pyroxene-granulite gneisses. These igneous rocks are intruded into the Leverburgh and Langevat supracrustals. Radiometric dating suggests that the complex was intruded over a period from about 2.2–1.9 Ga, comparable to the age of the Loch Maree Group. The Ness Anorthosite, exposed on the northeastern tip of Lewis, is also found associated with metasediments and yields a similar Sm-Nd model age of about 2.2 Ga. It is considered possible that the South Harris and Ness bodies once formed part of a continuous body, disrupted by Laxfordian deformation.

Langevat and Leverburgh metasediments

These two belts of metasediments flank the South Harris igneous complex, and form the largest outcrop of such rocks in the Outer Hebrides. Radiometric dating has shown these metasediments to be of Paleoproterozoic age, similar to the rocks of the Loch Maree Group. The relationship between these metasediments and Scourian gneisses remains unclear.Outer Isles fault zone

This fault zone stretches the entire length of the Outer Hebrides, a distance of about 200 km, dipping 20°–30° to the ESE. The fault rock within the fault zone shows a long and complex history of movement with the development of fault breccia,mylonite

Mylonite is a fine-grained, compact metamorphic rock produced by dynamic recrystallization of the constituent minerals resulting in a reduction of the grain size of the rock. Mylonites can have many different mineralogical compositions; it is a ...

and pseudotachylite

Pseudotachylyte (sometimes written as pseudotachylite) is an extremely fine-grained to glassy, dark, cohesive rock occurring as veinsTrouw, R.A.J., C.W. Passchier, and D.J. Wiersma (2010) ''Atlas of Mylonites- and related microstructures.'' Spring ...

, indicating faulting at a wide range of crustal levels.

Lewisian inliers within the Morar Group and Loch Ness Supergroup

Despite the multiple reworking that has affected Lewisian-like gneisses within the metasediments of these two sequences, they show evidence of a common history, although with some important differences. The largest, the Glenelg-Attadale inlier, shows evidence ofeclogite

Eclogite () is a metamorphic rock containing garnet ( almandine- pyrope) hosted in a matrix of sodium-rich pyroxene ( omphacite). Accessory minerals include kyanite, rutile, quartz, lawsonite, coesite, amphibole, phengite, paragonite, zoisit ...

facies metamorphism within both of the tectonically juxtaposed units that make up the inlier, thought to be associated with crustal thickening during a Paleoproterozoic event at about 1.7 Ga and the Grenvillian orogenic event respectively.

See also

*References

External links

{{Commons category, Lewisian GneissRocks of NW Scotland

at Oxford Earth Sciences:

Geology of Scotland Hebrides Gneiss