A lesbian is a

homosexual

Homosexuality is romantic attraction, sexual attraction, or sexual behavior between people of the same sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, homosexuality is "an enduring pattern of emotional, romantic, and/or sexual attractions" exc ...

woman or girl.

The word is also used for women in relation to their

sexual identity or

sexual behavior

Human sexual activity, human sexual practice or human sexual behaviour is the manner in which humans experience and express their sexuality. People engage in a variety of sexual acts, ranging from activities done alone (e.g., masturbation) t ...

, regardless of

sexual orientation

Sexual orientation is an enduring personal pattern of romantic attraction or sexual attraction (or a combination of these) to persons of the opposite sex or gender, the same sex or gender, or to both sexes or more than one gender. Patterns ar ...

, or as an adjective to characterize or associate nouns with female homosexuality or same-sex attraction.

Relatively little in history was documented to describe female homosexuality, though the earliest mentions date to at least the 500s BC. When early

sexologists

Sexology is the scientific study of human sexuality, including human sexual interests, behaviors, and functions. The term ''sexology'' does not generally refer to the non-scientific study of sexuality, such as social criticism.

Sexologists app ...

in the late 19th century began to categorize and describe homosexual behavior, hampered by a lack of knowledge about homosexuality or women's sexuality, they distinguished lesbians as women who did not adhere to female

gender roles

A gender role, or sex role, is a social norm deemed appropriate or desirable for individuals based on their gender or sex.

Gender roles are usually centered on conceptions of masculinity and femininity. The specifics regarding these gende ...

. They classified them as mentally ill—a designation which has been reversed since the late 20th century in the global scientific community.

Women in homosexual relationships in Europe and the United States responded to the discrimination and repression either by hiding their personal lives, or accepting the label of outcast and creating a subculture and

identity

Identity may refer to:

* Identity document

* Identity (philosophy)

* Identity (social science)

* Identity (mathematics)

Arts and entertainment Film and television

* ''Identity'' (1987 film), an Iranian film

* ''Identity'' (2003 film), an ...

. Following

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, during a period of social repression when governments actively persecuted homosexuals, women developed networks to socialize with and educate each other. Gaining greater economic and social freedom allowed them to determine how they could form relationships and families. With

second-wave feminism

Second-wave feminism was a period of feminist activity that began in the early 1960s and lasted roughly two decades, ending with the feminist sex wars in the early 1980s and being replaced by third-wave feminism in the early 1990s. It occurred ...

and the growth of scholarship in women's history and sexuality in the late 20th century, the definition of ''lesbian'' broadened, leading to debate about the term's use.

Lisa M. Diamond found that female same-sex sexuality is uniquely fluid even over short time spans but that lesbians display a more stable or core same-sex orientation.

Some women identify as simultaneously lesbian and

bisexual

Bisexuality is romantic attraction, sexual attraction, or sexual behavior toward both males and females. It may also be defined as the attraction to more than one gender, to people of both the same and different gender, or the attraction t ...

. One's sexual identity is not necessarily the same as one's sexual behavior. For example, lesbians may remain

closeted

''Closeted'' and ''in the closet'' are metaphors for LGBTQ people who have not disclosed their sexual orientation or gender identity and aspects thereof, including sexual identity and sexual behavior. This metaphor is associated and sometime ...

and identify as straight in order to avoid

homophobic

Homophobia encompasses a range of negative attitudes and feelings toward homosexuality or people who identify or are perceived as being lesbian, Gay men, gay or bisexual. It has been defined as contempt, prejudice, aversion, hatred, or ant ...

discrimination.

Etymology

The word ''lesbian'' is the

demonym

A demonym (; ) or 'gentilic' () is a word that identifies a group of people ( inhabitants, residents, natives) in relation to a particular place. Demonyms are usually derived from the name of the place ( hamlet, village, town, city, region, ...

of the Greek island of

Lesbos

Lesbos or Lesvos ( ) is a Greek island located in the northeastern Aegean Sea. It has an area of , with approximately of coastline, making it the third largest island in Greece and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, eighth largest ...

, home to the 6th-century BCE poet

Sappho

Sappho (; ''Sapphṓ'' ; Aeolic Greek ''Psápphō''; ) was an Ancient Greek poet from Eresos or Mytilene on the island of Lesbos. Sappho is known for her lyric poetry, written to be sung while accompanied by music. In ancient times, Sapph ...

.

From various ancient writings, historians gathered that a group of young women were left in Sappho's charge for their instruction or cultural edification.

[ Foster, Jeannette H. (1956). ''Sex Variant Women in Literature'', Naiad Press edition, 1985. ] Little of Sappho's poetry survives, but her remaining poetry reflects the topics she wrote about: women's daily lives, their relationships, and rituals. She focused on the beauty of women and proclaimed her love for girls.

Before the mid-19th century, the word ''lesbian'' referred to any derivative or aspect of Lesbos, including a

type of wine.

Use of the word ''lesbianism'' to describe erotic relationships between women had been documented in 1870.

In 1875, critic

George Saintsbury

George Edward Bateman Saintsbury, FBA (23 October 1845 – 28 January 1933), was an English critic, literary historian, editor, teacher, and wine connoisseur. He is regarded as a highly influential critic of the late 19th and early 20th cent ...

referred to

Baudelaire's poem "Delphine and Hippolyte" (a poem about love between two women and without reference to Lesbos) as "Lesbian".

[ (Document made available by ]Columbia University Libraries

Columbia University Libraries is the library system of Columbia University and one of the largest academic library systems in North America. With 15.0 million volumes and over 160,000 journals and serials, as well as extensive electronic resources ...

. PDF downloads automatically.) In 1890, the term ''lesbian'' was used in a medical dictionary as an adjective to describe

tribadism

Tribadism ( ) or tribbing, commonly known by its scissoring position, is a lesbian sexual practice involving vulva-to-vulva contact or rubbing the vulva against the partner's thigh, stomach, buttocks, arm, or other body parts (excluding the mouth) ...

(as "lesbian love"). The terms ''lesbian'', ''invert'' and ''homosexual'' were interchangeable with ''sapphist'' and ''

sapphism

''Sapphism'' is an umbrella term for any woman Interpersonal attraction, attracted to women or in a Interpersonal relationship, relationship with another woman, regardless of their sexual orientations, and encompassing the romantic love between ...

'' around the turn of the 20th century.

The use of ''lesbian'' in medical literature became prominent; by 1925, the word was recorded as a noun to mean the female equivalent of a

sodomite.

["Lesbian"]

Oxford English Dictionary

, Second Edition, 1989. Retrieved on January 7, 2009.

Sexuality and identity

Lesbian Identity Formation

More discussion on gender and

sexual orientation

Sexual orientation is an enduring personal pattern of romantic attraction or sexual attraction (or a combination of these) to persons of the opposite sex or gender, the same sex or gender, or to both sexes or more than one gender. Patterns ar ...

has affected how many women view themselves. Social norms generally support heterosexuality, and lesbians are a minority orientation. When a woman realizes her romantic and sexual attraction to another woman, it may cause an "existential crisis"; many who go through this adopt the identity of a lesbian. They challenge society's negative stereotypes about homosexuals to learn how to function in a lesbian subculture.

Lesbians in western cultures generally share an identity that parallels those built on ethnicity; they have a shared history and subculture, and similar experiences with discrimination which has caused many lesbians to reject heterosexual principles. This identity is unique from gay men and heterosexual women, and often creates tension with bisexual women.

Self-Identification vs Behavior

Researchers, including

social scientists

Social science (often rendered in the plural as the social sciences) is one of the branches of science, devoted to the study of societies and the relationships among members within those societies. The term was formerly used to refer to the f ...

, state that often behavior and identity do not match: women may label themselves heterosexual but have sexual relations with women, self-identified lesbians may have sex with men, or women may find that what they considered an immutable sexual identity has changed over time.

A study by

Lisa M. Diamond et al. applying

dynamical systems

In mathematics, a dynamical system is a system in which a Function (mathematics), function describes the time dependence of a Point (geometry), point in an ambient space, such as in a parametric curve. Examples include the mathematical models ...

modeling to daily diary data from 33

sexual minority

Sexual and gender minorities (SGM) comprise individuals whose sexual identity, sexual orientation, sexual behavior, or gender identity differ from the majority of the surrounding society. Sexual minorities include lesbians, gay men, bisexual peo ...

women over a 21-day period found that, despite considerable day-to-day variability in same-sex attractions and behaviors, participants exhibited a stable “core sexual orientation.”

Using linear oscillator models, researchers observed that this fluidity occurred across women identifying as lesbian, bisexual, or fluid.

The findings suggest that female same-sex sexuality is uniquely dynamic and that models of sexual orientation should account for its gender-specific patterns of variability and stability.

It found that "lesbian and fluid women were more exclusive than bisexual women in their sexual behaviors" and that "lesbian women appeared to lean toward exclusively same-sex attractions and behaviors."

It reported that lesbians "appeared to demonstrate a 'core' lesbian orientation."

One point of contention are lesbians who have had sex with men, while lesbians who have never had sex with men may be referred to as "

gold star lesbians". Those who have had sex with men may face ridicule from other lesbians or identity challenges with regard to defining what it means to be a lesbian.

A 2001 article on differentiating lesbians for medical studies and health research suggested identifying lesbians using the three characteristics of identity only, sexual behavior only, or both combined. The article declined to include desire or attraction as it rarely has bearing on measurable health or psychosocial issues.

Researchers state that there is no standard definition of ''lesbian'' because "The term has been used to describe women who have sex with women, either exclusively or in addition to sex with men (i.e., ''behavior''); women who self-identify as lesbian (i.e., ''identity''); and women whose sexual preference is for women (i.e., ''desire'' or ''attraction'')" ... "The lack of a standard definition of lesbian and of standard questions to assess who is lesbian has made it difficult to clearly define a population of lesbian women."

How and where study samples were obtained can also affect the definition.

The Importance of Sex

The notion that sexual activity between women is necessary to define a lesbian or lesbian relationship continues to be debated.

Some arguments are about the concept of

lesbian bed death and research by sexologists Philip Blumstein and

Pepper Schwartz. In their 1983 survey, they asked couples "About how often during the last year have you and your partner had sex relations?" and found that long-term lesbian couples named lower numbers than heterosexual or homosexual male couples, calling this "lesbian bed death".

Some arguments attested that the study was flawed and misrepresented accurate sexual contact between women. Other critiques suggest that the language "sex relations" could easily be misinterpreted to mean "heterosexual intercourse". Other critiques suggest that sexual contact between women has increased since 1983.

Some lesbians dispute the study's definition of sexual contact. Others introduced other factors such as deeper connections existing between women that make frequent sexual relations redundant. Others claimed that there is greater

sexual fluidity

Sexual fluidity is one or more changes in sexuality or sexual identity (sometimes known as sexual orientation identity). Sexual orientation is stable for the vast majority of people, but some research indicates that some people may experience ch ...

in women causing them to move from heterosexual to bisexual to lesbian numerous times through their lives—or reject the labels entirely.

Female homosexuality without identity in western culture

There has been extensive debate as to what qualifies a historic relationship as 'lesbian'. When considering past relationships within appropriate historic context, there were times when love and sex were separate and unrelated notions.

In 1989, an academic cohort named the Lesbian History Group wrote:

Because of society's reluctance to admit that lesbians exist, a high degree of certainty is expected before historians or biographers are allowed to use the label. Evidence that would suffice in any other situation is inadequate here... A woman who never married, who lived with another woman, whose friends were mostly women, or who moved in known lesbian or mixed gay circles, may well have been a lesbian. ... But this sort of evidence is not 'proof'. What our critics want is incontrovertible evidence of sexual activity between women. This is almost impossible to find.

Female sexuality is often not adequately represented in texts and documents. Until very recently, much of what has been documented about women's sexuality has been written by men, in the context of male understanding, and relevant to women's associations to men—as their wives, daughters, or mothers, for example.

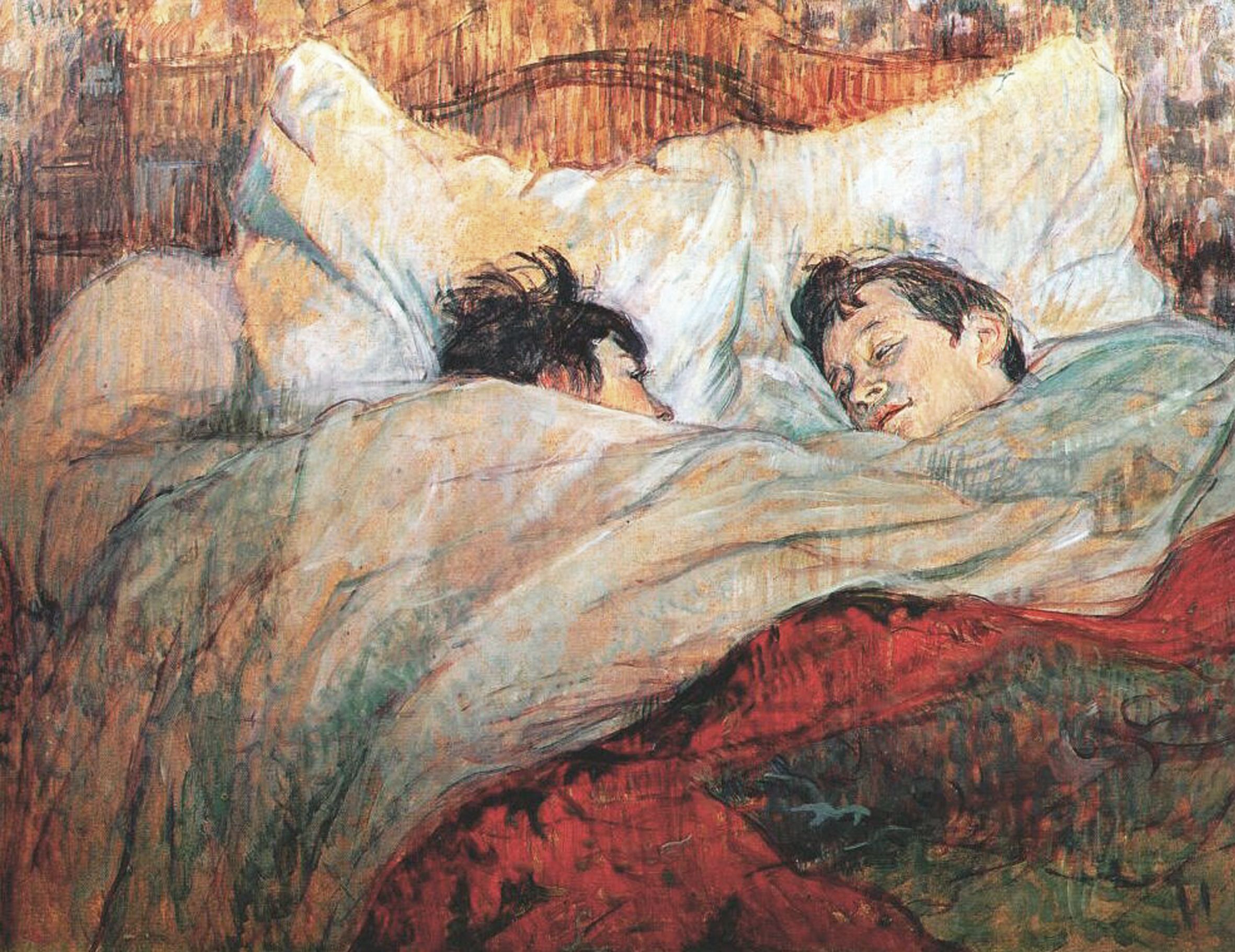

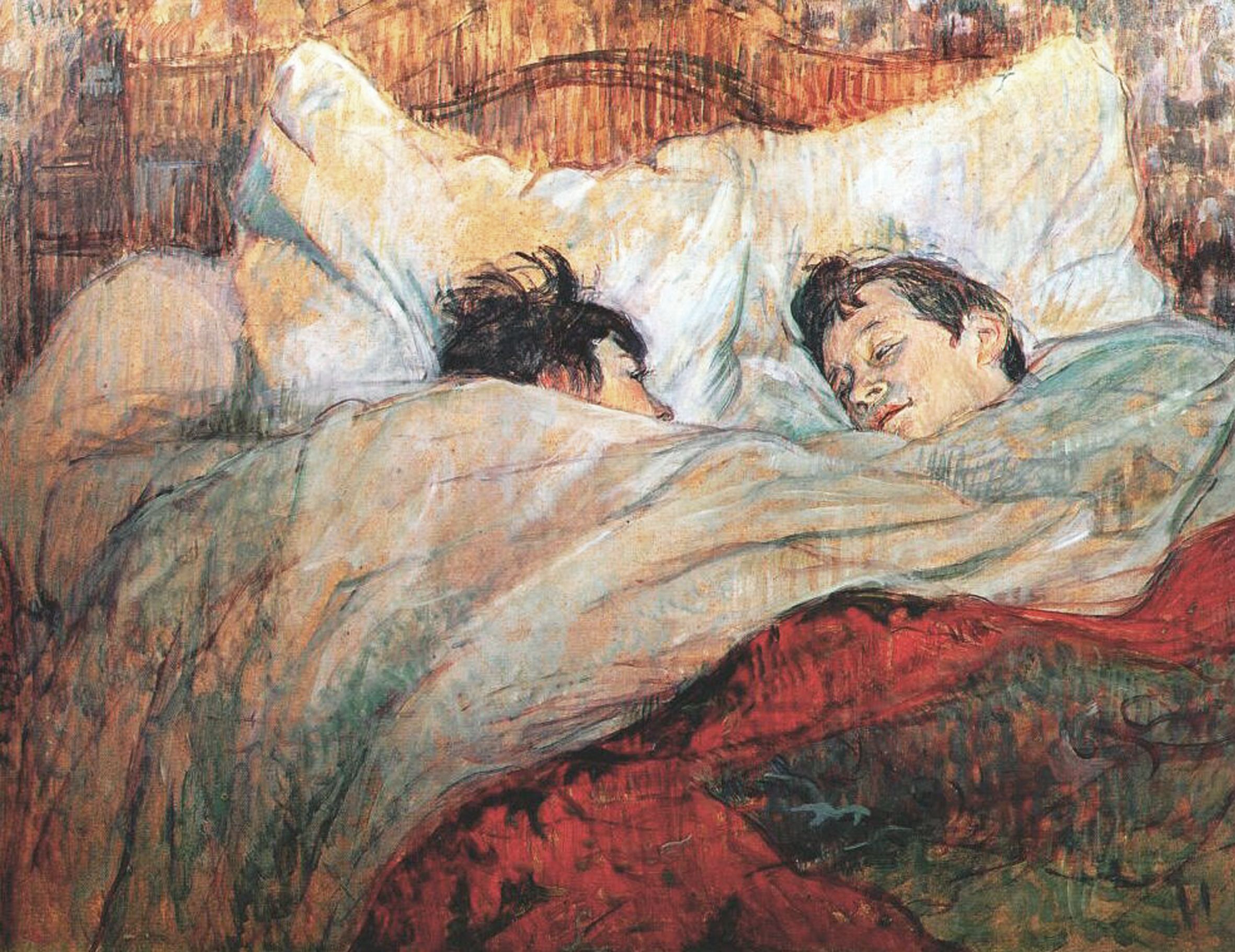

Often artistic representations of female sexuality suggest trends or ideas on broad scales, giving historians clues as to how widespread or accepted erotic relationships between women were.

Ancient Greece

Women in ancient Greece were sequestered with one another, and men were segregated likewise. In this homosocial environment, erotic and sexual relationships between males were frequently documented and recorded in literature, art, and philosophy. Very little was recorded about homosexual activity between Greek women. There is some speculation that similar relationships existed between women and girls. In the 700s BC, the poet

Alcman

Alcman (; ''Alkmán''; fl. 7th century BC) was an Ancient Greek choral lyric poet from Sparta. He is the earliest representative of the Alexandrian canon of the Nine Lyric Poets. He wrote six books of choral poetry, most of which is now lost; h ...

used the term ''aitis,'' as the feminine form of ''aites'' — which was the official term for the younger participant in a

pederastic

Pederasty or paederasty () is a sexual relationship between an adult man and an adolescent boy. It was a socially acknowledged practice in Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome, Rome and elsewhere in the world, such as Homosexuality in Japan#Pre-Mei ...

relationship.

In the 600s-500s BC, the female poet

Sappho

Sappho (; ''Sapphṓ'' ; Aeolic Greek ''Psápphō''; ) was an Ancient Greek poet from Eresos or Mytilene on the island of Lesbos. Sappho is known for her lyric poetry, written to be sung while accompanied by music. In ancient times, Sapph ...

wrote poetry longing for the love of women, fragments of which survive. In the 300s BC,

Aristophanes

Aristophanes (; ; ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek Ancient Greek comedy, comic playwright from Classical Athens, Athens. He wrote in total forty plays, of which eleven survive virtually complete today. The majority of his surviving play ...

, in

Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

's ''

Symposium

In Ancient Greece, the symposium (, ''sympósion'', from συμπίνειν, ''sympínein'', 'to drink together') was the part of a banquet that took place after the meal, when drinking for pleasure was accompanied by music, dancing, recitals, o ...

'', mentions women who are romantically attracted to other women, but uses the term ''trepesthai'' (to be focused on) instead of ''eros'', which was applied to other erotic relationships between men, and between men and women.

In the 100s A.D., in

Lucian's Dialogues of the Courtesans

Dialogue (sometimes spelled dialog in American English) is a written or spoken conversational exchange between two or more people, and a literary and theatrical form that depicts such an exchange. As a philosophical or didactic device, it is chi ...

, a female character admits to having lesbian sex, and talks about being pursued by two female characters.

Historian Nancy Rabinowitz argues that ancient Greek

red vase images which portray women with their arms around another woman's waist, or leaning on a woman's shoulders can be construed as expressions of romantic desire.

Women who appear on Greek pottery are depicted with affection, and in instances where women appear only with other women, their images are eroticized: bathing, touching one another, with

dildo

A dildo is a sex toy, often explicitly phallic in appearance, intended for sexual penetration or other sexual activity during masturbation or with sex partners. Dildos are made from a number of materials. The shape and size are typically t ...

s placed in and around such scenes, and sometimes with imagery also seen in depictions of heterosexual marriage or pederastic seduction.

The lives of ancient Greek women were in general little-documented; Rabinowitz writes that the lack of interest from 19th-century historians who specialized in

Greek studies

Hellenic studies (also Greek studies) is an interdisciplinary scholarly field that focuses on the language, literature, history and politics of post-classical Greece. In university, a wide range of courses expose students to viewpoints that help ...

regarding the daily lives and sexual inclinations of women in Greece was due to their social priorities. She postulates that this lack of interest led the field to become over male-centric and was partially responsible for the limited information available on female topics in ancient Greece.

Ancient Rome

In 8 CE, Book IX of

Ovid

Publius Ovidius Naso (; 20 March 43 BC – AD 17/18), known in English as Ovid ( ), was a Augustan literature (ancient Rome), Roman poet who lived during the reign of Augustus. He was a younger contemporary of Virgil and Horace, with whom he i ...

's the ''

Metamorphoses

The ''Metamorphoses'' (, , ) is a Latin Narrative poetry, narrative poem from 8 Common Era, CE by the Ancient Rome, Roman poet Ovid. It is considered his ''Masterpiece, magnum opus''. The poem chronicles the history of the world from its Cre ...

'' portrayed a lesbian love story between

Iphis

In Greek mythology, Greek and Roman mythology, Iphis ( or ; , Genitive case, gen. Ἴφιδος ''Íphidos'') was a child of Telethusa and Ligdus in Crete, born female and raised as male, who was later transformed by the goddess Isis into a m ...

and Ianthe. When Iphis' mother becomes pregnant, her husband declares that he will kill the child if it is a girl. She bears a girl conceals her sex by giving her a name that is of ambiguous gender: Iphis. When the "son" is thirteen, the father chooses a golden-haired maiden named Ianthe as the "boy's" bride. The love of the two girls is written sympathetically:

They were of equal age, they both were lovely,

Had learned the ABC from the same teachers,

And so love came to both of them together

In simple innocence, and filled their hearts

With equal longing.

As the marriage draws closer, Iphis recoils, calling her love "monstrous and unheard of", and fearing discovery. The gods hear the girl's moans and turn her into a man.

In the first century CE, the fabulist

Phaedrus explained lesbianism through a myth of his own making:

Prometheus

In Greek mythology, Prometheus (; , , possibly meaning "forethought")Smith"Prometheus". is a Titans, Titan. He is best known for defying the Olympian gods by taking theft of fire, fire from them and giving it to humanity in the form of technol ...

, coming home drunk from a party, had mistakenly exchanged the genitals of some women and some men. Phaedrus remarked: "Lust now enjoys perverted pleasure."

Modern scholarship indicates that ancient Roman men viewed female homosexuality with hostility. They considered women who engaged in sexual relations with other women to be biological oddities that would attempt to penetrate women—and sometimes men—with "monstrously enlarged"

clitoris

In amniotes, the clitoris ( or ; : clitorises or clitorides) is a female sex organ. In humans, it is the vulva's most erogenous zone, erogenous area and generally the primary anatomical source of female Human sexuality, sexual pleasure. Th ...

es.

[Verstraete, Beert; , Vernon (eds.) (2005). ''Same-Sex Desire and Love in Greco-Roman Antiquity and In the Classical Tradition of the West'', Harrington Park Press. . pp. 238–240.] According to scholar James Butrica, lesbianism "challenged not only the Roman male's view of himself as the exclusive giver of sexual pleasure but also the most basic foundations of Rome's male-dominated culture". No historical documentation exists of ancient Roman women who had other women as partners.

Early modern Europe

Female homosexuality did not receive the same negative response from religious or criminal authorities as male homosexuality or adultery did throughout history. Whereas sodomy between men, men and women, and men and animals was punishable by death in England, acknowledgment of sexual contact between women was nonexistent in medical and legal texts. The earliest law against female homosexuality appeared in France in 1270.

In Spain, Italy, and the Holy Roman Empire, sodomy between women was included in acts considered unnatural and punishable by burning to death, although few instances are recorded of this taking place.

The earliest such execution occurred in

Speier, Germany, in 1477. Forty days'

penance

Penance is any act or a set of actions done out of contrition for sins committed, as well as an alternative name for the Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, and Oriental Orthodox sacrament of Reconciliation or Confession.

The word ''penance'' derive ...

was demanded of nuns who "rode" each other or were discovered to have touched each other's breasts. An Italian nun named Sister

Benedetta Carlini

Benedetta Carlini (20 January 1590 – 7 August 1661) was an Italian Catholic nun. As abbess of the Convent of the Mother of God at Pescia, she was best known for her claims of experiencing mystic visions as well as a reported lesbian relations ...

was documented to have seduced many of her sisters when possessed by a Divine spirit named "Splenditello"; to end her relationships with other women, she was placed in solitary confinement for the last 40 years of her life.

Female homoeroticism was so common in English literature and theater that historians suggest it was fashionable for a period during the

Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

.

Englishwoman

Mary Frith

Mary Frith (c. 1584 – 26 July 1659), alias Moll (or Mal) Cutpurse, was a notorious English pickpocket and fence of the London underworld.

Meaning of nicknames

Moll, apart from being a nickname for Mary, was a common name in the 16th ...

has been described as lesbian in academic study.

Ideas about women's sexuality were linked to contemporary understanding of female physiology. The

vagina

In mammals and other animals, the vagina (: vaginas or vaginae) is the elastic, muscular sex organ, reproductive organ of the female genital tract. In humans, it extends from the vulval vestibule to the cervix (neck of the uterus). The #Vag ...

was considered an inward version of the penis; where nature's perfection created a man, often nature was thought to be trying to right itself by prolapsing the vagina to form a penis in some women.

These sex changes were later thought to be cases of

hermaphrodite

A hermaphrodite () is a sexually reproducing organism that produces both male and female gametes. Animal species in which individuals are either male or female are gonochoric, which is the opposite of hermaphroditic.

The individuals of many ...

s, and hermaphroditism became synonymous with female same-sex desire. Medical consideration of hermaphroditism depended upon measurements of the

clitoris

In amniotes, the clitoris ( or ; : clitorises or clitorides) is a female sex organ. In humans, it is the vulva's most erogenous zone, erogenous area and generally the primary anatomical source of female Human sexuality, sexual pleasure. Th ...

; a longer, engorged clitoris was thought to be used by women to penetrate other women. Penetration was the focus of concern in all sexual acts, and a woman who was thought to have uncontrollable desires because of her engorged clitoris was called a "tribade" (literally, one who rubs).

Not only was an abnormally engorged clitoris thought to create lusts in some women that led them to masturbate, but pamphlets warning women about

masturbation

Masturbation is a form of autoeroticism in which a person Sexual stimulation, sexually stimulates their own Sex organ, genitals for sexual arousal or other sexual pleasure, usually to the point of orgasm. Stimulation may involve the use of han ...

leading to such oversized organs were written as cautionary tales. For a while, masturbation and lesbian sex carried the same meaning.

Class distinction became linked as the fashion of female homoeroticism passed. Tribades were simultaneously considered members of the lower class trying to ruin virtuous women, and representatives of an aristocracy corrupt with debauchery. Satirical writers began to suggest that political rivals (or more often, their wives) engaged in tribadism in order to harm their reputations.

Queen Anne was rumored to have a passionate relationship with

Sarah Churchill, Duchess of Marlborough, her closest adviser and confidante. When Churchill was ousted as the queen's favorite, she purportedly spread allegations of the queen having affairs with her bedchamberwomen.

Marie Antoinette

Marie Antoinette (; ; Maria Antonia Josefa Johanna; 2 November 1755 – 16 October 1793) was the last List of French royal consorts, queen of France before the French Revolution and the establishment of the French First Republic. She was the ...

was also the subject of such speculation for some months between 1795 and 1796.

Female husbands

Hermaphroditism appeared in medical literature enough to be considered common knowledge, although cases were rare. Homoerotic elements in literature were pervasive, specifically the masquerade of one gender for another to fool an unsuspecting woman into being seduced. Such plot devices were used in

Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 23 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's natio ...

's ''

Twelfth Night

''Twelfth Night, or What You Will'' is a romantic comedy by William Shakespeare, believed to have been written around 1601–1602 as a Twelfth Night entertainment for the close of the Christmas season. The play centres on the twins Viola an ...

'' (1601), ''

The Faerie Queene

''The Faerie Queene'' is an English epic poem by Edmund Spenser. Books IIII were first published in 1590, then republished in 1596 together with books IVVI. ''The Faerie Queene'' is notable for its form: at over 36,000 lines and over 4,000 sta ...

'' by

Edmund Spenser

Edmund Spenser (; – 13 January 1599 Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.) was an English poet best known for ''The Faerie Queene'', an epic poem and fantastical allegory celebrating the House of Tudor, Tudor dynasty and Elizabeth I. He is re ...

in 1590, and

James Shirley

James Shirley (or Sherley) (September 1596 – October 1666) was an English dramatist.

He belonged to the great period of English dramatic literature, but, in Charles Lamb (writer), Charles Lamb's words, he "claims a place among the worthies of ...

's ''

The Bird in a Cage

''The Bird in a Cage, or The Beauties'' is a Caroline era comedy written by James Shirley, first published in 1633. The play is notable, even among Shirley's plays, for its lushness — what one critic has called "gay romanticism run mad."

...

'' (1633).

Cases during the Renaissance of women taking on male personae and going undetected for years or decades have been recorded, though whether these cases would be described as

transvestism

Cross-dressing is the act of wearing clothes traditionally or stereotypically associated with a different gender. From as early as pre-modern history, cross-dressing has been practiced in order to disguise, comfort, entertain, and express onesel ...

by homosexual women,

or in contemporary sociology characterised as

transgender

A transgender (often shortened to trans) person has a gender identity different from that typically associated with the sex they were sex assignment, assigned at birth.

The opposite of ''transgender'' is ''cisgender'', which describes perso ...

, is debated and depends on the individual details of each case.

If discovered, punishments ranged from death, to time in the

pillory

The pillory is a device made of a wooden or metal framework erected on a post, with holes for securing the head and hands, used during the medieval and renaissance periods for punishment by public humiliation and often further physical abuse. ...

, to being ordered never to dress as a man again.

Henry Fielding

Henry Fielding (22 April 1707 – 8 October 1754) was an English writer and magistrate known for the use of humour and satire in his works. His 1749 comic novel ''The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling'' was a seminal work in the genre. Along wi ...

wrote a pamphlet titled ''The Female Husband'' in 1746, based on the life of

Mary Hamilton

"Mary Hamilton", or "The Fower Maries" ("The Four Marys"), is a common name for a well-known sixteenth-century ballad from Scotland based on an apparently fictional incident about a lady-in-waiting to a Queen of Scotland. It is Child Ballads, C ...

, who was arrested after marrying a woman while masquerading as a man, and was sentenced to public whipping and six months in jail. Similar examples were procured of Catharine Linck in Prussia in 1717, executed in 1721; Swiss Anne Grandjean married and relocated with her wife to Lyons, but was exposed by a woman with whom she had had a previous affair and sentenced to time in the stocks and prison.

Queen

's tendency to dress as a man was well known during her time and excused because of her noble birth. She was brought up as a male and there was speculation at the time that she was a hermaphrodite. Even after Christina abdicated the throne in 1654 to avoid marriage, she was known to pursue romantic relationships with women.

Some historians view cases of cross-dressing women to be manifestations of women seizing power they would naturally be unable to enjoy in feminine attire, or their way of making sense out of their desire for women.

Lillian Faderman

Lillian Faderman (born July 18, 1940) is an American historian whose books on lesbian history and LGBT history have earned critical praise and awards. ''The New York Times'' named three of her books on its "Notable Books of the Year" list. In addi ...

argues that Western society was threatened by women who rejected their feminine roles. Catharine Linck and other women who were accused of using dildos, such as two nuns in 16th century Spain executed for using "material instruments", were punished more severely than those who did not.

Two marriages between women were recorded in

Cheshire

Cheshire ( ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in North West England. It is bordered by Merseyside to the north-west, Greater Manchester to the north-east, Derbyshire to the east, Staffordshire to the south-east, and Shrop ...

, England, in 1707 (between Hannah Wright and Anne Gaskill) and 1708 (between Ane Norton and Alice Pickford) with no comment about both parties being female.

Reports of clergymen with lax standards who performed weddings—and wrote their suspicions about one member of the wedding party—continued to appear for the next century.

Outside Europe, women were able to dress as men and go undetected.

Deborah Sampson

Deborah Sampson Gannett, also known as Deborah Samson or Deborah Sampson, (December 17, 1760 – April 29, 1827) was a Massachusetts woman who disguised herself as a man in order to serve in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary ...

fought in the

American Revolution

The American Revolution (1765–1783) was a colonial rebellion and war of independence in which the Thirteen Colonies broke from British America, British rule to form the United States of America. The revolution culminated in the American ...

under the name Robert Shurtlieff, and pursued relationships with women.

Edward De Lacy Evans

Edward De Lacy Evans ( – 25 August 1901) was a servant, blacksmith, and gold miner who immigrated from Ireland to Australia in 1856.

Evans gained international attention in 1879 when it was revealed that he was assigned female at birth.

Thr ...

was born female in Ireland, but took a male name during the voyage to Australia and lived as a man for 23 years in Victoria, marrying three times.

Percy Redwood created a scandal in New Zealand in 1909 when she was found to be

Amy Bock

Amy Maud Bock (18 May 1859 – 29 August 1943) was a Tasmanian-born New Zealand female confidence trickster. Her usual pattern involved making emotional claims to her employer or other acquaintances in order to obtain money or property, or comm ...

, who had married a woman from Port Molyneaux; newspapers argued whether it was a sign of insanity or an inherent character flaw.

Re-examining romantic friendships

During the 17th through 19th centuries, a woman expressing passionate love for another woman was fashionable, accepted, and encouraged.

These relationships were termed

romantic friendship

A romantic friendship (also passionate friendship or affectionate friendship) is a very close but typically non-sexual relationship between friends, often involving a degree of physical closeness beyond that which is common in contemporary West ...

s,

Boston marriage

A "Boston marriage" was, historically, the cohabitation of two women who were independent of financial support from a man. The term is said to have been in use in New England in the late 19th–early 20th century. Some of these relationships were ...

s, or "sentimental friends", and were common in the U.S., Europe, and especially in England. Documentation of these relationships is possible by a large volume of letters written between women. Whether the relationship included any genital component was not a matter for public discourse, but women could form strong and exclusive bonds with each other and still be considered virtuous, innocent, and chaste; a similar relationship with a man would have destroyed a woman's reputation. In fact, these relationships were promoted as alternatives to and practice for a woman's marriage to a man.

One such relationship was between

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (née Pierrepont; 15 May 168921 August 1762) was an English aristocrat, medical pioneer, writer, and poet. Born in 1689, Lady Mary spent her early life in England. In 1712, Lady Mary married Edward Wortley Montagu, ...

, who wrote to Anne Wortley in 1709: "Nobody was so entirely, so faithfully yours ... I put in your lovers, for I don't allow it possible for a man to be so sincere as I am."

Similarly, English poet

Anna Seward

Anna Seward (12 December 1742 ld style: 1 December 1742./ref>Often wrongly given as 1747.25 March 1809) was an English Romantic poet, often called the Swan of Lichfield. She benefited from her father's progressive views on female education.

L ...

had a devoted friendship to

Honora Sneyd

Honora Edgeworth (''née'' Sneyd; 1751 – 1 May 1780) was an eighteenth-century English writer, mainly known for her associations with literary figures of the day particularly Anna Seward and the Lunar Society, and for her work on children's ...

, who was the subject of many of Seward's sonnets and poems. When Sneyd married despite Seward's protest, Seward's poems became angry. Seward continued to write about Sneyd long after her death, extolling Sneyd's beauty and their affection and friendship.

As a young woman, writer and philosopher

Mary Wollstonecraft

Mary Wollstonecraft ( , ; 27 April 175910 September 1797) was an English writer and philosopher best known for her advocacy of women's rights. Until the late 20th century, Wollstonecraft's life, which encompassed several unconventional ...

was attached to a woman named

Fanny Blood

Frances "Fanny" Blood (1758 – 29 November 1785) was an English illustrator and educator, and longtime friend of Mary Wollstonecraft.

Early life

Blood was born in 1758, the daughter of Matthew Blood the Younger (1730–1794) and Caroline Roe ( ...

. Writing to another woman by whom she had recently felt betrayed, Wollstonecraft declared, "The roses will bloom when there's peace in the breast, and the prospect of living with my Fanny gladdens my heart:—You know not how I love her."

Perhaps the most famous of these romantic friendships was between Eleanor Butler and Sarah Ponsonby, nicknamed the

Ladies of Llangollen

The "Ladies of Llangollen", Eleanor Butler (1739–1829) and Sarah Ponsonby (1755–1831), were two Irish nobility, upper-class Irish women who lived together as a couple. Their relationship scandalised and fascinated their contemporaries. The ...

. Butler and Ponsonby eloped in 1778, to the relief of Ponsonby's family (concerned about their reputation had she run away with a man)

to live together in Wales for 51 years and be thought of as eccentrics.

Their story was considered "the epitome of virtuous romantic friendship" and inspired poetry by Anna Seward and

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (February 27, 1807 – March 24, 1882) was an American poet and educator. His original works include the poems " Paul Revere's Ride", '' The Song of Hiawatha'', and '' Evangeline''. He was the first American to comp ...

.

Diarist

Anne Lister

Anne Lister (3 April 1791 – 22 September 1840) was an English diarist, famous for revelations for which she was dubbed "the first modern lesbian".

Lister was from a minor landowning family at Shibden in Calderdale, West Riding of Yorkshir ...

, captivated by Butler and Ponsonby, recorded her affairs with women between 1817 and 1840. Some of it was written in code, detailing her sexual relationships with Marianna Belcombe and Maria Barlow.

Both Lister and Eleanor Butler were considered masculine by contemporary news reports, and though there were suspicions that these relationships were sapphist in nature, they were nonetheless praised in literature.

Romantic friendships were also popular in the U.S. Enigmatic poet

Emily Dickinson

Emily Elizabeth Dickinson (December 10, 1830 – May 15, 1886) was an American poet. Little-known during her life, she has since been regarded as one of the most important figures in American poetry. Dickinson was born in Amherst, Massac ...

wrote over 300 letters and poems to Susan Gilbert, who later became her sister-in-law, and engaged in another romantic correspondence with Kate Scott Anthon. Anthon broke off their relationship the same month Dickinson entered self-imposed lifelong seclusion.

Nearby in Hartford, Connecticut, African American freeborn women

Addie Brown and

Rebecca Primus left evidence of their passion in letters: "No ''kisses'' is like youres".

In Georgia, Alice Baldy wrote to Josie Varner in 1870, "Do you know that if you touch me, or speak to me there is not a nerve of fibre in my body that does not respond with a thrill of delight?"

Around the turn of the 20th century, the development of higher education provided opportunities for women. In all-female surroundings, a culture of romantic pursuit was fostered in women's colleges. Older students mentored younger ones, called on them socially, took them to all-women dances, and sent them flowers, cards, and poems that declared their undying love for each other.

These were called "smashes" or "spoons", and they were written about quite frankly in stories for girls aspiring to attend college in publications such as ''

Ladies Home Journal

''Ladies' Home Journal'' was an American magazine that ran until 2016 and was last published by the Meredith Corporation. It was first published on February 16, 1883, and eventually became one of the leading women's magazines of the 20th century ...

'', a children's magazine titled ''

St. Nicholas'', and a collection called ''Smith College Stories'', without negative views.

Enduring loyalty, devotion, and love were major components to these stories, and sexual acts beyond kissing were consistently absent.

Women who had the option of a career instead of marriage labeled themselves

New Women

''New Women'' () is a 1935 Chinese silent drama film produced by the United Photoplay Service. It is sometimes translated as ''New Woman''. The film starred Ruan Lingyu (in her penultimate film) and was directed by Cai Chusheng. This film beca ...

and took their new opportunities very seriously. Faderman calls this period "the last breath of innocence" before 1920 when characterizations of female affection were connected to sexuality, marking lesbians as a unique and often unflatteringly portrayed group.

Specifically, Faderman connects the growth of women's independence and their beginning to reject strictly prescribed roles in the Victorian era to the scientific designation of lesbianism as a type of aberrant sexual behavior.

Lesbians in western culture

History of Sexology (Late 1800s-Early 1900s)

In research on "

inversion

Inversion or inversions may refer to:

Arts

* ''Inversion'' (artwork), a 2005 temporary sculpture in Houston, Texas

* Inversion (music), a term with various meanings in music theory and musical set theory

* ''Inversions'' (novel) by Iain M. Bank ...

" by German sexologist

Magnus Hirschfeld

Magnus Hirschfeld (14 May 1868 – 14 May 1935) was a German physician, Sexology, sexologist and LGBTQ advocate, whose German citizenship was later revoked by the Nazi government.David A. Gerstner, ''Routledge International Encyclopedia of Queer ...

, researchers categorized what was normal sexual behavior for men and women, and therefore to what extent men and women varied from the "perfect male sexual type" and the "perfect female sexual type".

Sexologists

Richard von Krafft-Ebing from Germany and Britain's

Havelock Ellis

Henry Havelock Ellis (2 February 1859 – 8 July 1939) was an English physician, eugenicist, writer, Progressivism, progressive intellectual and social reformer who studied human sexuality. He co-wrote the first medical textbook in English on h ...

wrote some of the earliest and more enduring categorizations of female

same-sex attraction

This page lists common initialisms relating to LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer) people and the LGBTQ community.

Key

Variants of LGBTQ

* 2SLGBTQI+

* GBT or GBTQ – variant omitting "lesbian", typically when referring ...

, approaching it as a form of insanity.

Krafft-Ebing, who considered lesbianism a neurological disease, and Ellis, who was influenced by Krafft-Ebing's writings, disagreed about whether sexual inversion was generally a lifelong condition. Ellis believed that many women who professed love for other women changed their feelings about such relationships after they had experienced marriage and a "practical life".

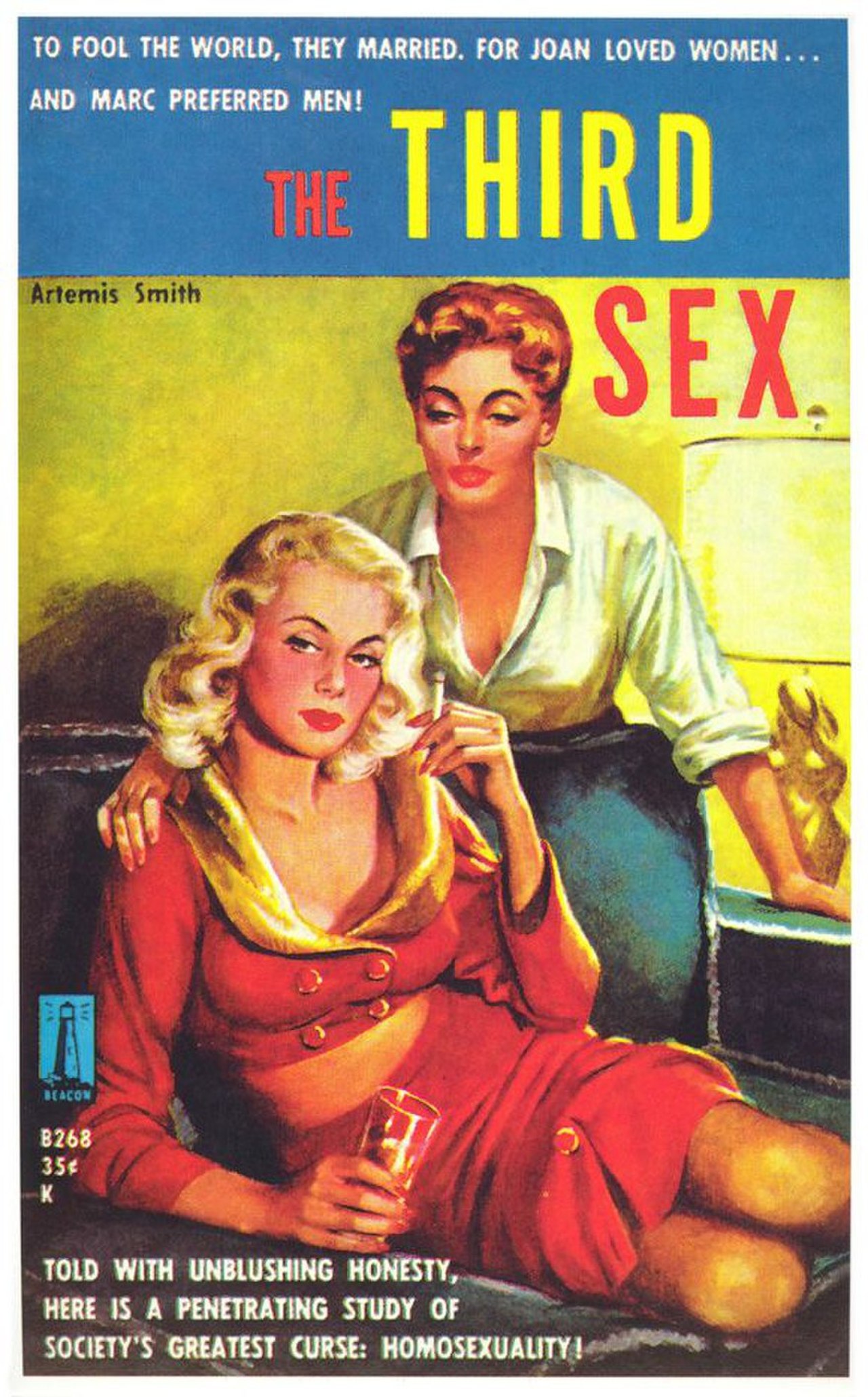

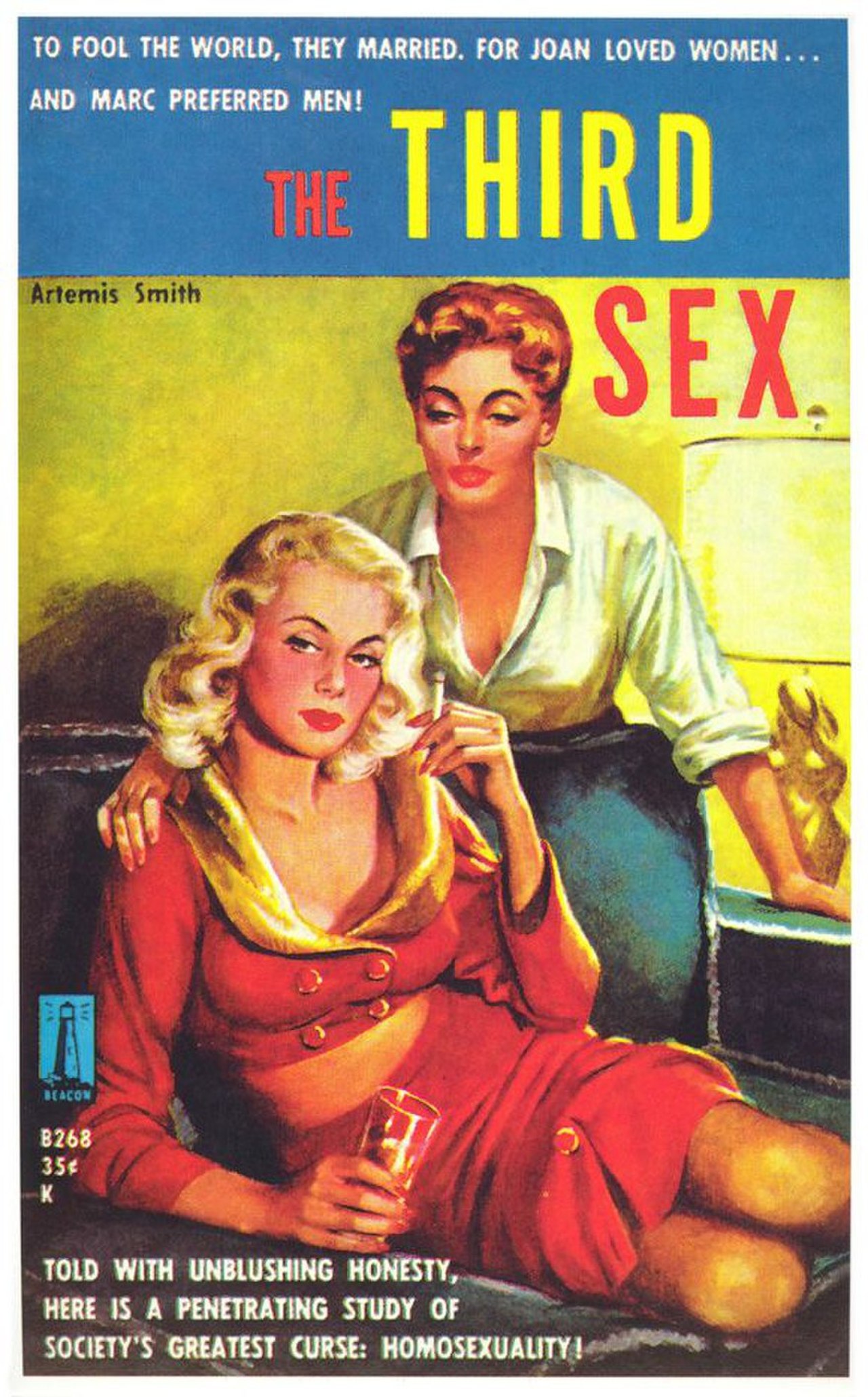

Ellis conceded that there were "true inverts" who would spend their lives pursuing erotic relationships with women. These were members of the "

third sex

Third gender or third sex is an identity recognizing individuals categorized, either by themselves or by society, as neither a man nor a woman. Many gender systems around the world include three or more genders, deriving the concept either from ...

" who rejected the roles of women to be subservient, feminine, and domestic.

''Invert'' described the opposite gender roles, and also the related attraction to women instead of men; since women in the

Victorian period

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the reign of Queen Victoria, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. Slightly different definitions are sometimes used. The era followed th ...

were considered unable to initiate sexual encounters, women who did so with other women were thought of as possessing masculine sexual desires.

The work of Krafft-Ebing and Ellis was widely read and helped to create public consciousness of female homosexuality. The sexologists' claims that homosexuality was a congenital anomaly were generally well-accepted by homosexual men; it indicated that their behavior was not inspired by nor should be considered a criminal vice, as was widely acknowledged. In the absence of any other material to describe their emotions, homosexuals accepted the designation of different or perverted, and used their outlaw status to form social circles in Paris and Berlin. ''Lesbian'' began to describe elements of a subculture.

Lesbians in Western cultures in particular often classify themselves as having an

identity

Identity may refer to:

* Identity document

* Identity (philosophy)

* Identity (social science)

* Identity (mathematics)

Arts and entertainment Film and television

* ''Identity'' (1987 film), an Iranian film

* ''Identity'' (2003 film), an ...

that defines their individual sexuality, as well as their membership to a group that shares common traits.

Women in many cultures throughout history have had sexual relations with other women, but they rarely were designated as part of a group of people based on whom they had physical relations with. As women have generally been political minorities in Western cultures, the added medical designation of homosexuality has been cause for the development of a subcultural identity.

Early 1900s Western Culture

In the early 1900s, some well-known women denied or concealed their lesbian behavior, such as the unmarried professor

Jeannette Augustus Marks at

Mount Holyoke College

Mount Holyoke College is a Private college, private Women's colleges in the United States, women's Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in South Hadley, Massachusetts, United States. It is the oldest member of the h ...

, who lived with the college president,

Mary Woolley, for 36 years. Marks discouraged young women from "abnormal" friendships and insisted happiness could only be attained with a man.

Other women embraced the distinction and used their uniqueness to set themselves apart from heterosexual women and gay men.

From the 1890s to the 1930s, American heiress

Natalie Clifford Barney

Natalie Clifford Barney (October 31, 1876 – February 2, 1972) was an American writer who hosted a salon (gathering), literary salon at her home in Paris that brought together French and international writers. She influenced other authors thro ...

held a weekly salon in Paris to which major artistic celebrities were invited and where lesbian topics were the focus. Combining Greek influences with contemporary French eroticism, she attempted to create an updated and idealized version of Lesbos in her salon.

Her contemporaries included artist

Romaine Brooks

Romaine Brooks (born Beatrice Romaine Goddard; May 1, 1874 – December 7, 1970) was an American painter who worked mostly in Paris and Capri. She specialized in portrait painting, portraiture and used a subdued tonal Palette (painting), palette ...

, who painted others in her circle; writers

Colette

Sidonie-Gabrielle Colette (; 28 January 1873 – 3 August 1954), known as Colette or Colette Willy, was a French author and woman of letters. She was also a Mime artist, mime, actress, and journalist. Colette is best known in the English-speaki ...

,

Djuna Barnes

Djuna Barnes ( ; June 12, 1892 – June 18, 1982) was an American artist, illustrator, journalist, and writer who is perhaps best known for her novel '' Nightwood'' (1936), a cult classic of lesbian fiction and an important work of modernist lite ...

, social host

Gertrude Stein

Gertrude Stein (February 3, 1874 – July 27, 1946) was an American novelist, poet, playwright, and art collector. Born in Allegheny, Pennsylvania (now part of Pittsburgh), and raised in Oakland, California, Stein moved to Paris in 1903, and ...

, and novelist

Radclyffe Hall

Marguerite Antonia Radclyffe-Hall (12 August 1880 – 7 October 1943), more known under her pen name Radclyffe Hall, was an English poet and author, best known for the novel ''The Well of Loneliness'', a groundbreaking work in lesbian literatur ...

.

Berlin

Berlin ( ; ) is the Capital of Germany, capital and largest city of Germany, by both area and List of cities in Germany by population, population. With 3.7 million inhabitants, it has the List of cities in the European Union by population withi ...

had a vibrant homosexual culture in the 1920s, and about 50 clubs catered to lesbians. (''The Girlfriend'') magazine, published between 1924 and 1933, targeted lesbians. ''

Garçonne'' (aka (''Woman Love'')) was aimed at lesbians and male

transvestites

Cross-dressing is the act of wearing clothes traditionally or stereotypically associated with a different gender. From as early as pre-modern history, cross-dressing has been practiced in order to disguise, comfort, entertain, and express onesel ...

.

These publications were controlled by men as owners, publishers, and writers. Around 1926,

Selli Engler

Selma "Selli" Engler (27 September 1899 – 30 April 1972) was a leading activist of the lesbian movement in Berlin from about 1924 to 1931.

In 1931, Engler withdrew from the movement and focused on her career as a writer. After the end of Worl ...

founded ''

Die BIF – Blätter Idealer Frauenfreundschaften'' (''The BIF – Papers on Ideal Women Friendships''), the first lesbian publication owned, published and written by women. In 1928, the lesbian bar and nightclub guide ''Berlins lesbische Frauen'' (''The Lesbians of Berlin'') by

Ruth Margarite Röllig further popularized the German capital as a center of lesbian activity. Clubs varied between large establishments that became tourist attractions, to small neighborhood cafes where local women went to meet other women. The cabaret song ("The Lavender Song") became an anthem to the lesbians of Berlin. Although it was sometimes tolerated, homosexuality was illegal in Germany and law enforcement used permitted gatherings as an opportunity to register the names of homosexuals for future reference.

Magnus Hirschfeld's

Scientific-Humanitarian Committee

The Scientific-Humanitarian Committee (, WhK) was founded by Magnus Hirschfeld in Berlin in May 1897, to campaign for social recognition of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people, and against their legal persecution. It was the first L ...

, which promoted tolerance for homosexuals in

Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

, welcomed lesbian participation, and a surge of lesbian-themed writing and political activism in the German feminist movement became evident.

In 1928, Radclyffe Hall published a novel titled ''

The Well of Loneliness

''The Well of Loneliness'' is a lesbian novel by British author Radclyffe Hall that was first published in 1928 by Jonathan Cape. It follows the life of Stephen Gordon, an Englishwoman from an upper-class family whose " sexual inversion" (hom ...

''. The novel's plot centers around Stephen Gordon, a woman who identifies herself as an invert after reading Krafft-Ebing's ''

Psychopathia Sexualis

'': '' (''Sexual Psychopathy: A Clinical-Forensic Study'', also known as '', with Especial Reference to the Antipathetic Sexual Instinct: A Medico-forensic Study'') is an 1886 book by and one of the first texts about sexual pathology. The boo ...

'', and lives within the homosexual subculture of Paris. The novel included a foreword by Havelock Ellis and was intended to be a call for tolerance for inverts by publicizing their disadvantages and accidents of being born inverted.

Hall subscribed to Ellis and Krafft-Ebing's theories and rejected

Freud

Sigmund Freud ( ; ; born Sigismund Schlomo Freud; 6 May 1856 – 23 September 1939) was an Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for evaluating and treating pathologies seen as originating from conflicts in t ...

's theory that

same-sex attraction

This page lists common initialisms relating to LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer) people and the LGBTQ community.

Key

Variants of LGBTQ

* 2SLGBTQI+

* GBT or GBTQ – variant omitting "lesbian", typically when referring ...

was caused by childhood trauma and was curable. The publicity Hall received was due to unintended consequences; the novel was tried for

obscenity

An obscenity is any utterance or act that strongly offends the prevalent morality of the time. It is derived from the Latin , , "boding ill; disgusting; indecent", of uncertain etymology. Generally, the term can be used to indicate strong moral ...

in London, a spectacularly scandalous event described as "''the'' crystallizing moment in the construction of a visible modern English lesbian subculture" by professor Laura Doan.

Newspaper stories frankly divulged that the book's content includes "sexual relations between Lesbian women", and photographs of Hall often accompanied details about lesbians in most major print outlets within a span of six months.

Hall reflected the appearance of a "mannish" woman in the 1920s:

short cropped hair, tailored suits (often with pants), and

monocle

A monocle is a type of corrective lens used to correct or enhance the visual perception in only one eye. It consists of a circular lens placed in front of the eye and held in place by the eye socket itself. Often, to avoid losing the monoc ...

that became widely recognized as a "uniform". When British women supported the war effort during the First World War, they became familiar with masculine clothing, and were considered patriotic for wearing uniforms and pants. Postwar masculinization of women's clothing became associated primarily with lesbianism.

In the United States, the 1920s was a decade of social experimentation, particularly with sex. This was heavily influenced by the writings of

Sigmund Freud

Sigmund Freud ( ; ; born Sigismund Schlomo Freud; 6 May 1856 – 23 September 1939) was an Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for evaluating and treating psychopathology, pathologies seen as originating fro ...

, who theorized that sexual desire would be sated unconsciously, despite an individual's wish to ignore it. Freud's theories were much more pervasive in the U.S. than in Europe. With the well-publicized notion that sexual acts were a part of lesbianism and their relationships, sexual experimentation was widespread. Large cities that provided a nightlife were immensely popular, and women began to seek out sexual adventure. Bisexuality became chic, particularly in America's first gay neighborhoods.

No location saw more visitors for its possibilities of homosexual nightlife than

Harlem

Harlem is a neighborhood in Upper Manhattan, New York City. It is bounded roughly by the Hudson River on the west; the Harlem River and 155th Street on the north; Fifth Avenue on the east; and Central Park North on the south. The greater ...

, the predominantly African American section of

New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

. White "slummers" enjoyed

jazz

Jazz is a music genre that originated in the African-American communities of New Orleans, Louisiana, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Its roots are in blues, ragtime, European harmony, African rhythmic rituals, spirituals, h ...

, nightclubs, and anything else they wished.

Blues

Blues is a music genre and musical form that originated among African Americans in the Deep South of the United States around the 1860s. Blues has incorporated spiritual (music), spirituals, work songs, field hollers, Ring shout, shouts, cha ...

singers

Ma Rainey

Gertrude "Ma" Rainey ( Pridgett; April 26, 1886 – December 22, 1939) was an American blues singer and influential early-blues recording artist. Dubbed the " Mother of the Blues", she bridged earlier vaudeville and the authentic expression of ...

,

Bessie Smith

Bessie Smith (April 15, 1892 – September 26, 1937) was an African-American blues singer widely renowned during the Jazz Age. Nicknamed the "Honorific nicknames in popular music, Empress of the Blues" and formerly Queen of the Blues, she was t ...

,

Ethel Waters

Ethel Waters (October 31, 1896 – September 1, 1977) was an American singer and actress. Waters frequently performed jazz, swing, and pop music on the Broadway stage and in concerts. She began her career in the 1920s singing blues. Her no ...

, and

Gladys Bentley

Gladys Alberta Bentley (August 12, 1907 – January 18, 1960) was an American blues singer, pianist, and entertainer during the Harlem Renaissance.

Her career skyrocketed when she appeared at Harry Hansberry's Clam House, a well-known gay speake ...

sang about affairs with women to visitors such as

Tallulah Bankhead

Tallulah Brockman Bankhead (January 31, 1902 – December 12, 1968) was an American actress. Primarily an actress of the stage, Bankhead also appeared in several films including an award-winning performance in Alfred Hitchcock's ''Lifeboat (194 ...

,

Beatrice Lillie

Beatrice Gladys Lillie, Lady Peel (29 May 1894 – 20 January 1989) was a Canadian-born British actress, singer and comedy performer.

She began to perform as a child with her mother and sister. She made her West End debut in 1914 and soon gain ...

, and the soon-to-be-named

Joan Crawford

Joan Crawford (born Lucille Fay LeSueur; March 23, 190? was an American actress. She started her career as a dancer in traveling theatrical companies before debuting on Broadway theatre, Broadway. Crawford was signed to a motion-picture cont ...

.

Homosexuals began to draw comparisons between their newly recognized minority status and that of African Americans.

Among African American residents of

Harlem

Harlem is a neighborhood in Upper Manhattan, New York City. It is bounded roughly by the Hudson River on the west; the Harlem River and 155th Street on the north; Fifth Avenue on the east; and Central Park North on the south. The greater ...

, lesbian relationships were common and tolerated, though not overtly embraced. Some women staged lavish wedding ceremonies, even filing licenses using masculine names with New York City.

Most homosexual women were married to men and participated in affairs with women regularly.

Across town,

Greenwich Village

Greenwich Village, or simply the Village, is a neighborhood on the west side of Lower Manhattan in New York City, bounded by 14th Street (Manhattan), 14th Street to the north, Broadway (Manhattan), Broadway to the east, Houston Street to the s ...

also saw a growing homosexual community; both Harlem and Greenwich Village provided furnished rooms for single men and women, which was a major factor in their development as centers for homosexual communities.

The tenor was different in Greenwich Village than Harlem.

Bohemians

Bohemian or Bohemians may refer to:

*Anything of or relating to Bohemia

Culture and arts

* Bohemianism, an unconventional lifestyle, originally practised by 19th–20th century European and American artists and writers.

* Bohemian style, a f ...

—intellectuals who rejected Victorian ideals—gathered in the Village. Homosexuals were predominantly male, although figures such as poet

Edna St. Vincent Millay

Edna St. Vincent Millay (February 22, 1892 – October 19, 1950) was an American lyric poetry, lyrical poet and playwright. Millay was a renowned social figure and noted Feminism, feminist in New York City during the Roaring Twenties and beyond. ...

and social host

Mabel Dodge

Mabel Evans Dodge Sterne Luhan (pronounced ''LOO-hahn''; née Ganson; February 26, 1879 – August 13, 1962) was an American patron of the arts, who was particularly associated with the Taos art colony.

Early life

Mabel Ganson was the heiress o ...

were known for their affairs with women and promotion of tolerance of homosexuality.

Women in the U.S. who could not visit Harlem or live in Greenwich Village for the first time were able to visit saloons in the 1920s without being considered prostitutes. The existence of a public space for women to socialize in

bars that were known to cater to lesbians "became the single most important public manifestation of the subculture for many decades", according to historian

Lillian Faderman

Lillian Faderman (born July 18, 1940) is an American historian whose books on lesbian history and LGBT history have earned critical praise and awards. ''The New York Times'' named three of her books on its "Notable Books of the Year" list. In addi ...

.

Great Depression

The primary component necessary to encourage lesbians to be public and seek other women was economic independence, which virtually disappeared in the 1930s with the

Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

. Independent women in the 1930s were generally seen as holding jobs that men should have. Most lesbians in the U.S. found it necessary to marry to a "

front

Front may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Films

* ''The Front'' (1943 film), a 1943 Soviet drama film

* '' The Front'', 1976 film

Music

* The Front (band), an American rock band signed to Columbia Records and active in the 1980s and ...

" such as a gay man where both could pursue homosexual relationships with public discretion, or to a man who expected a traditional wife.

The hostile social attitude made very small and close-knit communities in large cities that centered around bars. Women in other locales typically remained isolated. Speaking of homosexuality in any context was socially forbidden, and women rarely discussed lesbianism even amongst themselves; they referred to openly gay people as "in the Life".

Freudian psychoanalytic theory was pervasive in influencing doctors to consider homosexuality as a neurosis afflicting immature women.

Homosexual subculture disappeared in Germany with the rise of the Nazis in 1933.

World War II

The onset of

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

caused a massive upheaval in people's lives as military mobilization engaged millions of men. Women were also accepted into the military in the U.S.

Women's Army Corps

The Women's Army Corps (WAC; ) was the women's branch of the United States Army. It was created as an auxiliary unit, the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC), on 15 May 1942, and converted to an active duty status in the Army of the United S ...

(WACs) and U.S. Navy's

Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service

United States Naval Reserve (Women's Reserve), better known as the WAVES (for Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service), was the women's branch of the United States Naval Reserve during World War II. It was established on July 21, 1942, ...

(WAVES). Unlike processes to screen out male homosexuals, which had been in place since the creation of the American military, there were no methods to identify or screen for lesbians; they were put into place gradually during World War II. Despite common attitudes regarding women's traditional roles in the 1930s, independent and masculine women were directly recruited by the military in the 1940s, and frailty discouraged.

[ Berube, Allan (1990). ''Coming Out Under Fire: The History of Gay Men and Women in World War II'', The Free Press. ]

Some women arrived at the recruiting station in a man's suit, denied ever being in love with another woman, and were easily inducted.

Sexual activity was forbidden and

blue discharge

A blue discharge, also called blue ticket, was a form of administrative military discharge formerly issued by the United States beginning in 1916. It was neither honorable nor dishonorable. The blue ticket became the discharge of choice for comman ...

was almost certain if one identified oneself as a lesbian. As women found each other, they formed into tight groups on base, socialized at service clubs, and began to use code words. Historian

Allan Bérubé

Allan Bérubé (pronounced BEH-ruh-bay; December 3, 1946 – December 11, 2007) was a gay American historian, activist, independent scholar, self-described "community-based" researcher and college drop-out, and award-winning author, best know ...

documented that homosexuals in the armed forces either consciously or subconsciously refused to identify themselves as homosexual or lesbian, and also never spoke about others' orientation.

The most masculine women were not necessarily common, though they were visible, so they tended to attract women interested in finding other lesbians. Women had to broach the subject about their interest in other women carefully, sometimes taking days to develop a common understanding without asking or stating anything outright.

Women who did not enter the military were aggressively called upon to take industrial jobs left by men, in order to continue national productivity. The increased mobility, sophistication, and independence of many women during and after the war made it possible for women to live without husbands, something that would not have been feasible under different economic and social circumstances, further shaping lesbian networks and environments.

Lesbians were not included under

Paragraph 175

Paragraph 175, known formally a§175 StGBand also referred to as Section 175 in English language, English, was a provision of the Strafgesetzbuch, German Criminal Code from 15 May 1871 to 10 March 1994. It Criminalization of homosexuality, mad ...

of the

German Criminal Code

''Strafgesetzbuch'' (, literally "penal law book"), abbreviated to ''StGB'', is the German penal code.

History

In Germany the ''Strafgesetzbuch'' goes back to the Penal Code of the German Empire passed in the year 1871 on May 15 in Reichst ...

, which made homosexual acts between males a crime. The

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM) is the United States' official memorial to the Holocaust, dedicated to the documentation, study, and interpretation of the Holocaust. Opened in 1993, the museum explores the Holocaust through p ...

(USHMM) stipulates that this is because women were seen as subordinate to men, and the Nazi state feared lesbians less than gay men. Many lesbians were arrested and imprisoned for "asocial" behaviour, a label which was applied to women who did not conform to the ideal Nazi image of a woman (

child raising, kitchen work, churchgoing and passivity). These women were

identified with an

inverted black triangle.

Although lesbianism was not specifically criminalized by Paragraph 175, some lesbians reclaimed the black triangle symbol as gay men reclaimed the

pink triangle

A pink triangle is a symbol for the LGBT community. Initially intended as a badge of shame, it was later reappropriated as a positive symbol of self-identity. It originated in Nazi Germany in the 1930s and 1940s as one of the Nazi concentratio ...

, and many lesbians also reclaimed the pink triangle.

[ (. . .)]

Postwar

Following World War II, a nationwide movement pressed to return to pre-war society as quickly as possible in the U.S.

When combined with the increasing national paranoia about

communism

Communism () is a political sociology, sociopolitical, political philosophy, philosophical, and economic ideology, economic ideology within the history of socialism, socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a ...

and psychoanalytic theory that had become pervasive in medical knowledge, homosexuality became an undesired characteristic of employees working for the U.S. government in 1950. Homosexuals were thought to be vulnerable targets to

blackmail

Blackmail is a criminal act of coercion using a threat.

As a criminal offense, blackmail is defined in various ways in common law jurisdictions. In the United States, blackmail is generally defined as a crime of information, involving a thr ...

, and the government purged its employment ranks of open homosexuals, beginning a widespread effort to gather intelligence about employees' private lives.

State and local governments followed suit, arresting people for congregating in bars and parks, and enacting laws against

cross-dressing

Cross-dressing is the act of wearing clothes traditionally or stereotypically associated with a different gender. From as early as pre-modern history, cross-dressing has been practiced in order to disguise, comfort, entertain, and express onesel ...

for men and women.

The U.S. military and government conducted many interrogations, asking if women had ever had sexual relations with another woman and essentially equating even a one-time experience to a criminal identity, thereby severely delineating heterosexuals from homosexuals.

In 1952, homosexuality was listed as a pathological emotional disturbance in the

American Psychiatric Association

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) is the main professional organization of psychiatrists and trainee psychiatrists in the United States, and the largest psychiatric organization in the world. It has more than 39,200 members who are in ...

's ''

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual

The ''Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders'' (''DSM''; latest edition: ''DSM-5-TR'', published in March 2022) is a publication by the American Psychiatric Association (APA) for the classification of mental disorders using a com ...

''.

The view that homosexuality was a curable sickness was widely believed in the medical community, general population, and among many lesbians themselves.

Attitudes and practices to ferret out homosexuals in public service positions extended to Australia

and Canada.

A section to create an offence of "gross indecency" between females was added to a bill in the United Kingdom

House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the Bicameralism, bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of ...

and passed there in 1921, but was rejected in the

House of Lords

The House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the lower house, the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England. One of the oldest ext ...

, apparently because they were concerned any attention paid to sexual misconduct would also promote it.

Underground socializing

Very little information was available about homosexuality beyond medical and psychiatric texts. Community meeting places consisted of bars that were commonly raided by police once a month on average, with those arrested exposed in newspapers. In response, eight women in San Francisco met in their living rooms in 1955 to socialize and have a safe place to dance. When they decided to make it a regular meeting, they became the first organization for lesbians in the U.S., titled the

Daughters of Bilitis

The Daughters of Bilitis (), also called the DOB or the Daughters, was the first lesbian civil and political rights organization in the United States. The organization, formed in San Francisco in 1955, was initially conceived as a secret soc ...

(DOB). The DOB began publishing a magazine titled ''

The Ladder'' in 1956. Inside the front cover of every issue was their mission statement, the first of which stated was "Education of the variant". It was intended to provide women with knowledge about homosexuality—specifically relating to women and famous lesbians in history. By 1956, the term "lesbian" had such a negative meaning that the DOB refused to use it as a descriptor, choosing "variant" instead.

The DOB spread to Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles, and ''The Ladder'' was mailed to hundreds—eventually thousands—of DOB members discussing the nature of homosexuality, sometimes challenging the idea that it was a sickness, with readers offering their own reasons why they were lesbians and suggesting ways to cope with the condition or society's response to it.

British lesbians followed with the publication of ''

Arena Three'' beginning in 1964, with a similar mission.

Butch and femme dichotomy

As a reflection of categories of sexuality so sharply defined by the government and society at large, early lesbian subculture developed rigid gender roles between women, particularly among the

working class

The working class is a subset of employees who are compensated with wage or salary-based contracts, whose exact membership varies from definition to definition. Members of the working class rely primarily upon earnings from wage labour. Most c ...

in the United States and Canada. For working class lesbians who wanted to live as homosexuals, "A functioning couple ... meant dichotomous individuals, if not male and female, then butch and femme", and the only models they had to go by were "those of the traditional female-male

oles Oles may refer to:

*

** Oles Berdnyk (1926–2003), Ukrainian writer, philosopher, theologian and public figure