Leloir Cardini on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Luis Federico Leloir (September 6, 1906 – December 2, 1987) was an Argentine

After returning again to

After returning again to

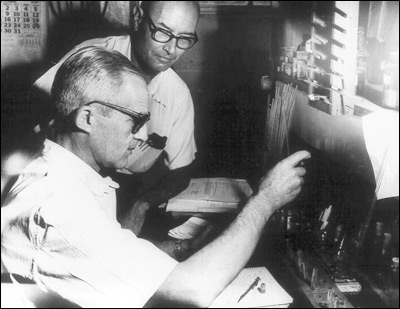

In 1945, Leloir ended his exile and returned to Argentina to work under Houssay at the Instituto de Investigaciones Bioquímicas de la Fundación Campomar, which Leloir would direct from its creation in 1947 by businessman and patron Jaime Campomar. Initially, the institute was composed of five rooms, a bathroom, central hall, patio, kitchen, and changing room.Ariel Barrios Medina, "Luis Federico Leloir (1906-1987): un esbozo biográfico" web: During the final years of the 1940s, although lacking financial resources and operating with very low-cost teams, Leloir's successful experiments would reveal the chemical origins of sugar synthesis in

In 1945, Leloir ended his exile and returned to Argentina to work under Houssay at the Instituto de Investigaciones Bioquímicas de la Fundación Campomar, which Leloir would direct from its creation in 1947 by businessman and patron Jaime Campomar. Initially, the institute was composed of five rooms, a bathroom, central hall, patio, kitchen, and changing room.Ariel Barrios Medina, "Luis Federico Leloir (1906-1987): un esbozo biográfico" web: During the final years of the 1940s, although lacking financial resources and operating with very low-cost teams, Leloir's successful experiments would reveal the chemical origins of sugar synthesis in

At the beginning of 1948, Leloir and his team identified the sugar nucleotides that were fundamental to the metabolism of carbohydrates, turning the Instituto Campomar into a biochemistry institution well known throughout the world. Immediately thereafter, Leloir received the Argentine Scientific Society Prize, one of the many awards he would receive both in Argentina and internationally. During this time, his team dedicated itself to the study of

At the beginning of 1948, Leloir and his team identified the sugar nucleotides that were fundamental to the metabolism of carbohydrates, turning the Instituto Campomar into a biochemistry institution well known throughout the world. Immediately thereafter, Leloir received the Argentine Scientific Society Prize, one of the many awards he would receive both in Argentina and internationally. During this time, his team dedicated itself to the study of

As his work in the laboratory was coming to an end, Leloir continued his teaching position in the Department of Natural Sciences at the University of Buenos Aires, taking a hiatus only to complete his studies at Cambridge and at the Enzyme Research Laboratory in the United States.

In 1983, Leloir became one of the founding members of the Third World Academy of Sciences, later renamed the

As his work in the laboratory was coming to an end, Leloir continued his teaching position in the Department of Natural Sciences at the University of Buenos Aires, taking a hiatus only to complete his studies at Cambridge and at the Enzyme Research Laboratory in the United States.

In 1983, Leloir became one of the founding members of the Third World Academy of Sciences, later renamed the

Leloir Institute

Fundación Instituto Leloir

The Official Site of Louisa Gross Horwitz Prize

{{DEFAULTSORT:Leloir, Luis Federico 1906 births 1987 deaths Physicians from Buenos Aires Argentine biochemists Argentine Nobel laureates Columbia University faculty Illustrious Citizens of Buenos Aires Nobel laureates in Chemistry Foreign members of the Royal Society Foreign associates of the National Academy of Sciences Washington University in St. Louis faculty University of Buenos Aires alumni Burials at La Recoleta Cemetery TWAS fellows 20th-century Argentine biologists International members of the American Philosophical Society 20th-century Argentine physicians

physician

A physician, medical practitioner (British English), medical doctor, or simply doctor is a health professional who practices medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring health through the Medical education, study, Med ...

and biochemist

Biochemists are scientists who are trained in biochemistry. They study chemical processes and chemical transformations in living organisms. Biochemists study DNA, proteins and Cell (biology), cell parts. The word "biochemist" is a portmanteau of ...

who received the 1970 Nobel Prize in Chemistry

The Nobel Prize in Chemistry () is awarded annually by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences to scientists in the various fields of chemistry. It is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Alfred Nobel in 1895, awarded for outst ...

for his discovery of the metabolic pathway

In biochemistry, a metabolic pathway is a linked series of chemical reactions occurring within a cell (biology), cell. The reactants, products, and Metabolic intermediate, intermediates of an enzymatic reaction are known as metabolites, which are ...

s by which carbohydrates

A carbohydrate () is a biomolecule composed of carbon (C), hydrogen (H), and oxygen (O) atoms. The typical hydrogen-to-oxygen atomic ratio is 2:1, analogous to that of water, and is represented by the empirical formula (where ''m'' and ''n'' ma ...

are synthesized and converted into energy in the body. Although born in France, Leloir received the majority of his education at the University of Buenos Aires

The University of Buenos Aires (, UBA) is a public university, public research university in Buenos Aires, Argentina. It is the second-oldest university in the country, and the largest university of the country by enrollment. Established in 1821 ...

and was director of the private research group Fundación Instituto Campomar until his death in 1987. His research into sugar nucleotide

Nucleotides are Organic compound, organic molecules composed of a nitrogenous base, a pentose sugar and a phosphate. They serve as monomeric units of the nucleic acid polymers – deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA), both o ...

s, carbohydrate

A carbohydrate () is a biomolecule composed of carbon (C), hydrogen (H), and oxygen (O) atoms. The typical hydrogen-to-oxygen atomic ratio is 2:1, analogous to that of water, and is represented by the empirical formula (where ''m'' and ''n'' ...

metabolism, and renal

In humans, the kidneys are two reddish-brown bean-shaped blood-filtering organs that are a multilobar, multipapillary form of mammalian kidneys, usually without signs of external lobulation. They are located on the left and right in the retrop ...

hypertension

Hypertension, also known as high blood pressure, is a Chronic condition, long-term Disease, medical condition in which the blood pressure in the artery, arteries is persistently elevated. High blood pressure usually does not cause symptoms i ...

garnered international attention and led to significant progress in understanding, diagnosing and treating the congenital disease galactosemia

Galactosemia (British galactosaemia, from Greek γαλακτόζη + αίμα, meaning galactose + blood, accumulation of galactose in blood) is a rare genetics, genetic Metabolism, metabolic Disease, disorder that affects an individual's ability t ...

. Leloir is buried in La Recoleta Cemetery

La Recoleta Cemetery () is a cemetery located in the Recoleta, Buenos Aires, Recoleta Barrios and Communes of Buenos Aires, neighbourhood of Buenos Aires, Argentina. It contains the graves of notable people, including Eva Perón, President of Ar ...

, Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires, controlled by the government of the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires, is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Argentina. It is located on the southwest of the Río de la Plata. Buenos Aires is classified as an Alpha− glob ...

.

Biography

Early years

Leloir's parents, Federico Augusto Rufino and Hortencia Aguirre de Leloir, traveled from Buenos Aires to Paris in the middle of 1906 with the intention of treating Federico's illness. However, Federico died in late August, and a week later Luis was born in an old house at 81 Víctor Hugo Road in Paris, a few blocks away from theArc de Triomphe

The Arc de Triomphe de l'Étoile, often called simply the Arc de Triomphe, is one of the most famous monuments in Paris, France, standing at the western end of the Champs-Élysées at the centre of Place Charles de Gaulle, formerly named Plac ...

. After returning to Argentina in 1908, Leloir lived together with his eight siblings on their family's extensive property ''El Tuyú'' that his grandparents had purchased after their immigration from the Basque Country of northern Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

: El Tuyú comprises 400 km2 of sandy land along the coastline from San Clemente del Tuyú

San Clemente del Tuyú is an Argentina, Argentine town in the ''La Costa Partido, Partido de la Costa'' district of the Province of Buenos Aires.

History

Noticed by Ferdinand Magellan in 1520, who gave nearby Cape San Antonio, Argentina, Cape S ...

to Mar de Ajó

Mar de Ajó is a coastal city in Buenos Aires Province, Argentina, and is located in the southern end of the seaside La Costa Partido (the Coast District). The region is known as the Tuju Corner (Rincón del Tuyú). Etymology

It owes its name to ...

which has since become a popular tourist attraction.

During his childhood, the future Nobel Prize winner found himself observing natural phenomena with particular interest; his schoolwork and readings highlighted the connections between the natural sciences and biology. His education was divided between Escuela General San Martín (primary school), Colegio Lacordaire

Colegio Lacordaire is a school in Cali, Colombia, that was established in 1956 by the Dominicans. It currently has offerings from infancy through grade eleven, with special emphasis on English language to prepare students to study abroad.

History ...

(secondary school), and for a few months at Beaumont College

Beaumont College was between 1861 and 1967 a Public school (UK), public school in Old Windsor, Old Windsor in Berkshire. Founded and run by the Society of Jesus, it offered a Roman Catholic public school education in rural surroundings, while l ...

in England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

. His grades were unspectacular, and his first stint in college ended quickly when he abandoned his architectural studies that he had begun in Paris' .

It was during the 1920s that Leloir invented '' salsa golf'' (golf sauce). After being served prawns with the usual sauce during lunch with a group of friends at the Ocean Club in Mar del Plata, Leloir came up with a peculiar combination of ketchup and mayonnaise to spice up his meal. With the financial difficulties that later plagued Leloir's laboratories and research, he would joke, "If I had patented that sauce, we'd have a lot more money for research right now."

Career

Buenos Aires

After returning again to

After returning again to Argentina

Argentina, officially the Argentine Republic, is a country in the southern half of South America. It covers an area of , making it the List of South American countries by area, second-largest country in South America after Brazil, the fourt ...

, Leloir obtained his Argentine citizenship and joined the Department of Medicine at the University of Buenos Aires

The University of Buenos Aires (, UBA) is a public university, public research university in Buenos Aires, Argentina. It is the second-oldest university in the country, and the largest university of the country by enrollment. Established in 1821 ...

in hopes of receiving his doctorate. However, he got off to a rocky start, requiring four attempts to pass his anatomy exam.Valeria Roman, "A cien años del nacimiento de Luis Federico Leloir" web:http://www.clarin.com/diario/2006/08/27/sociedad/s-01259864.htm He finally received his diploma in 1932 and began his residency in the Hospital de Clínicas and his medical internship in Ramos Mejía hospital. After some initial conflicts with colleagues and complications in his method of treating patients, Leloir decided to dedicate himself to research in the laboratory, claiming that "we could do little for our patients... antibiotics, psychoactive drugs, and all the new therapeutic agents were unknown t the time"

In 1933, he met Bernardo Houssay, who pointed Leloir towards investigating in his doctoral thesis the suprarenal glands and carbohydrate metabolism. Houssay happened to be friends with Carlos Bonorino Udaondo, the brother-in-law of Victoria Ocampo

Ramona Victoria Epifanía Rufina Ocampo (7 April 1890 – 27 January 1979) was an Argentine writer and intellectual. Best known as an advocate for others and as publisher of the literary magazine '' Sur'', she was also a writer and critic in he ...

, one of Leloir's cousins. Following the recommendation of Udaondo, Leloir began working with Houssay, who in 1947 would later win the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine () is awarded yearly by the Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute, Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute for outstanding discoveries in physiology or medicine. The Nobel Prize is not a single ...

. The two would develop a close relationship, collaborating on various projects until Houssay's death in 1971; in his lecture after winning the Nobel Prize, Leloir claimed that his "whole research career has been influenced by one person, Prof. Bernardo A. Houssay".

Cambridge

After only two years, Leloir received recognition from the medical department at the University of Buenos Aires for having produced the best doctoral thesis. Feeling that his knowledge in fields such asphysics

Physics is the scientific study of matter, its Elementary particle, fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge whi ...

, mathematics

Mathematics is a field of study that discovers and organizes methods, Mathematical theory, theories and theorems that are developed and Mathematical proof, proved for the needs of empirical sciences and mathematics itself. There are many ar ...

, chemistry

Chemistry is the scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter. It is a physical science within the natural sciences that studies the chemical elements that make up matter and chemical compound, compounds made of atoms, molecules a ...

, and biology

Biology is the scientific study of life and living organisms. It is a broad natural science that encompasses a wide range of fields and unifying principles that explain the structure, function, growth, History of life, origin, evolution, and ...

is lacking, he continued attending classes at the university as a part-time student. In 1936 he traveled to England to begin advanced studies at the University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a Public university, public collegiate university, collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209, the University of Cambridge is the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, wo ...

, under the supervision of another Nobel Prize winner, Sir Frederick Gowland Hopkins

Sir Frederick Gowland Hopkins (20 June 1861 – 16 May 1947) was an English biochemist who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1929, with Christiaan Eijkman, for the discovery of vitamins. He also discovered the amino ...

, who had obtained that distinction in 1929 for his work in physiology

Physiology (; ) is the science, scientific study of function (biology), functions and mechanism (biology), mechanisms in a life, living system. As a branches of science, subdiscipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ syst ...

and in revealing the critical role of vitamins

Vitamins are organic molecules (or a set of closely related molecules called vitamers) that are essential to an organism in small quantities for proper metabolic function. Essential nutrients cannot be synthesized in the organism in suff ...

in maintaining good health. Leloir's research in the Biochemical Laboratory of Cambridge centered around enzymes

An enzyme () is a protein that acts as a biological catalyst by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecules known as pro ...

, more specifically the effects of cyanide

In chemistry, cyanide () is an inorganic chemical compound that contains a functional group. This group, known as the cyano group, consists of a carbon atom triple-bonded to a nitrogen atom.

Ionic cyanides contain the cyanide anion . This a ...

and pyrophosphate

In chemistry, pyrophosphates are phosphorus oxyanions that contain two phosphorus atoms in a linkage. A number of pyrophosphate salts exist, such as disodium pyrophosphate () and tetrasodium pyrophosphate (), among others. Often pyrophosphates a ...

on succinic dehydrogenase; from this moment Leloir began to specialize in researching carbohydrate metabolism.

United States

Leloir returned to Buenos Aires in 1937 after his brief stay at Cambridge. 1943 saw Leloir marry; Luis Leloir and Amelia Zuberbuhler (1920-2013) would later have a daughter also named Amelia. However, his return to Argentina was amidst conflict and strife; Houssay had been expelled from the University of Buenos Aires for signing a public petition opposing theNazi

Nazism (), formally named National Socialism (NS; , ), is the far-right politics, far-right Totalitarianism, totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During H ...

regime in Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

and the military government led by Pedro Pablo Ramírez

Pedro Pablo Ramírez Menchaca (30 January 1884 – 12 May 1962) was President of Argentina from 7 June 1943, to 9 March 1944. He was the founder and leader of ''Guardia Nacional'', Argentina's fascist militia.

Life and career

After graduati ...

. Leloir fled to the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

, where he assumed the position of associate professor in the Department of Pharmacology

Pharmacology is the science of drugs and medications, including a substance's origin, composition, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, therapeutic use, and toxicology. More specifically, it is the study of the interactions that occur betwee ...

at Washington University in St. Louis

Washington University in St. Louis (WashU) is a private research university in St. Louis, Missouri, United States. Founded in 1853 by a group of civic leaders and named for George Washington, the university spans 355 acres across its Danforth ...

, collaborating with Carl Cori

Carl Ferdinand Cori, ForMemRS (December 5, 1896 – October 20, 1984) was a Czech-American biochemist and pharmacologist. He, together with his wife Gerty Cori and Argentine physiologist Bernardo Houssay, received a Nobel Prize in 1947 for ...

and Gerty Cori

Gerty Theresa Cori (; August 15, 1896 – October 26, 1957) was a Bohemian-Austrian and American biochemist who in 1947 was the third woman to win a Nobel Prize in science, and the first woman to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Me ...

and thereafter worked with David E. Green

David Ezra Green (August 5, 1910 – July 8, 1983) was an American biochemist who made significant contributions to the study of enzymes, particularly the electron transport chain and oxidative phosphorylation.

Life and career

Green was born in ...

at the College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University

Columbia University in the City of New York, commonly referred to as Columbia University, is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Churc ...

as a research assistant. Leloir would later credit Green with instilling within him the initiative to establish his own research in Argentina.

Fundación Instituto Campomar

yeast

Yeasts are eukaryotic, single-celled microorganisms classified as members of the fungus kingdom (biology), kingdom. The first yeast originated hundreds of millions of years ago, and at least 1,500 species are currently recognized. They are est ...

as well as the oxidation

Redox ( , , reduction–oxidation or oxidation–reduction) is a type of chemical reaction in which the oxidation states of the reactants change. Oxidation is the loss of electrons or an increase in the oxidation state, while reduction is ...

of fatty acid

In chemistry, in particular in biochemistry, a fatty acid is a carboxylic acid with an aliphatic chain, which is either saturated and unsaturated compounds#Organic chemistry, saturated or unsaturated. Most naturally occurring fatty acids have an ...

s in the liver; together with J. M. Muñoz, he produced an active cell-free system, a first in scientific research. It had initially been assumed that in order to study a cell, scientists could not separate it from its host organism, as oxidation could only occur in intact cells. Along the way, Muñoz and Leloir, unable to procure the costly refrigerated centrifuge needed to separate cell contents, improvised by spinning a tire stuffed with salt and ice.

By 1947 he had formed a team that included

Ranwel Caputto, Enrico Cabib, Raúl Trucco, Alejandro Paladini, Carlos Cardini and José Luis Reissig, with whom he investigated and discovered why a malfunctioning kidney and angiotensin

Angiotensin is a peptide hormone that causes vasoconstriction and an increase in blood pressure. It is part of the renin–angiotensin system, which regulates blood pressure. Angiotensin also stimulates the release of aldosterone from the adr ...

helped cause hypertension

Hypertension, also known as high blood pressure, is a Chronic condition, long-term Disease, medical condition in which the blood pressure in the artery, arteries is persistently elevated. High blood pressure usually does not cause symptoms i ...

. That same year, his colleague Caputto, in his investigations of the mammary gland

A mammary gland is an exocrine gland that produces milk in humans and other mammals. Mammals get their name from the Latin word ''mamma'', "breast". The mammary glands are arranged in organs such as the breasts in primates (for example, human ...

, made discoveries regarding carbohydrate storage and its subsequent transformation into a reserve energy form in organisms.

Sugar nucleotides

At the beginning of 1948, Leloir and his team identified the sugar nucleotides that were fundamental to the metabolism of carbohydrates, turning the Instituto Campomar into a biochemistry institution well known throughout the world. Immediately thereafter, Leloir received the Argentine Scientific Society Prize, one of the many awards he would receive both in Argentina and internationally. During this time, his team dedicated itself to the study of

At the beginning of 1948, Leloir and his team identified the sugar nucleotides that were fundamental to the metabolism of carbohydrates, turning the Instituto Campomar into a biochemistry institution well known throughout the world. Immediately thereafter, Leloir received the Argentine Scientific Society Prize, one of the many awards he would receive both in Argentina and internationally. During this time, his team dedicated itself to the study of glycoproteins

Glycoproteins are proteins which contain oligosaccharide (sugar) chains covalently attached to amino acid side-chains. The carbohydrate is attached to the protein in a cotranslational or posttranslational modification. This process is known a ...

; Leloir and his colleagues elucidated the primary mechanisms of galactose metabolism

(now called the Leloir pathway The Leloir pathway is a metabolic pathway for the catabolism of D-galactose. It is named after Luis Federico Leloir, who first described it.

In the first step, galactose mutarotase facilitates the conversion of β-D-galactose to α-D-galactose s ...

) and determined the cause of galactosemia, a serious genetic disorder

A genetic disorder is a health problem caused by one or more abnormalities in the genome. It can be caused by a mutation in a single gene (monogenic) or multiple genes (polygenic) or by a chromosome abnormality. Although polygenic disorders ...

that resulted in lactose intolerance

Lactose intolerance is caused by a lessened ability or a complete inability to digest lactose, a sugar found in dairy products. Humans vary in the amount of lactose they can tolerate before symptoms develop. Symptoms may include abdominal pain ...

.

The following year, he reached an agreement with Rolando García, dean of the Faculty of Exact and Natural Sciences

The Faculty of Exact and Natural Sciences (''Facultad de Ciencias Exactas y Naturales''; FCEN), commonly and informally known as Exactas, is the natural science school of the University of Buenos Aires, the largest university in Argentina.

It oc ...

at the University of Buenos Aires, which named Leloir, Carlos Eugenio Cardini and Enrico Cabib as titular professors in the university's newly founded Biochemical Institute. The institute would help develop scientific programs in budding Argentine universities as well as attract researchers and scholars from the United States, Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

, England, France, Spain, and other Latin American countries.

Following Jaime Campomar's death in 1957, Leloir and his team applied to the National Institutes of Health

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) is the primary agency of the United States government responsible for biomedical and public health research. It was founded in 1887 and is part of the United States Department of Health and Human Service ...

in the United States desperate for funding, and surprisingly was accepted. In 1958, the institute found a new home in a former all-girls school, a donation from the Argentine government. As Leloir and his research gained greater prominence, further research came from the Argentine Research Council, and the institute would later become associated with the University of Buenos Aires.''World of Scientific Discovery'', Thomas Gale, Thomson Corporation, 2005-2006

Later years

In his later years Leloir continued to study glycogen and other aspects of carbohydrate metabolism. As his work in the laboratory was coming to an end, Leloir continued his teaching position in the Department of Natural Sciences at the University of Buenos Aires, taking a hiatus only to complete his studies at Cambridge and at the Enzyme Research Laboratory in the United States.

In 1983, Leloir became one of the founding members of the Third World Academy of Sciences, later renamed the

As his work in the laboratory was coming to an end, Leloir continued his teaching position in the Department of Natural Sciences at the University of Buenos Aires, taking a hiatus only to complete his studies at Cambridge and at the Enzyme Research Laboratory in the United States.

In 1983, Leloir became one of the founding members of the Third World Academy of Sciences, later renamed the TWAS

The World Academy of Sciences for the advancement of science in developing countries (TWAS) is a merit-based science academy established for developing countries, uniting more than 1,400 scientists in some 100 countries. Its principal aim is t ...

.

Nobel Prize

On December 2, 1970, Leloir received the Nobel Prize for Chemistry from the King ofSweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. It borders Norway to the west and north, and Finland to the east. At , Sweden is the largest Nordic count ...

for his discovery of the metabolic pathway

In biochemistry, a metabolic pathway is a linked series of chemical reactions occurring within a cell (biology), cell. The reactants, products, and Metabolic intermediate, intermediates of an enzymatic reaction are known as metabolites, which are ...

s in lactose

Lactose is a disaccharide composed of galactose and glucose and has the molecular formula C12H22O11. Lactose makes up around 2–8% of milk (by mass). The name comes from (Genitive case, gen. ), the Latin word for milk, plus the suffix ''-o ...

, becoming only the third Argentine to receive the prestigious honor in any field at the time. In his acceptance speech at Stockholm

Stockholm (; ) is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in Sweden by population, most populous city of Sweden, as well as the List of urban areas in the Nordic countries, largest urban area in the Nordic countries. Approximately ...

, he borrowed from Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

's famous 1940 speech to the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the Bicameralism, bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of ...

and remarked, "never have I received so much for so little". Leloir and his team reportedly celebrated by drinking champagne from test tubes, a rare departure from the humility and frugality that characterized the atmosphere of Fundación Instituto Campomar under Leloir's direction. The $80,000 prize money was spent directly on research, and when asked about the significance of his achievement, Leloir responded:

Legacy

Leloir published a short autobiography, entitled "Long Ago and Far Away" in the 1983 ''Annual Review of Biochemistry''. The title, Leloir claims, is derived from one ofWilliam Henry Hudson

William Henry Hudson (4 August 1841 – 18 August 1922), known in Argentina as Guillermo Enrique Hudson, was an English Argentines, Anglo-Argentine author, natural history, naturalist and ornithology, ornithologist. Born in the Argentine pampas w ...

's novels that depicted the country wildlife and scenery of Leloir's childhood.

He died in Buenos Aires on December 2, 1987, of a heart attack soon after returning to his home from the laboratory, and is buried in La Recoleta Cemetery

La Recoleta Cemetery () is a cemetery located in the Recoleta, Buenos Aires, Recoleta Barrios and Communes of Buenos Aires, neighbourhood of Buenos Aires, Argentina. It contains the graves of notable people, including Eva Perón, President of Ar ...

. Mario Bunge

Mario Augusto Bunge ( ; ; September 21, 1919 – February 24, 2020) was an Argentine-Canadian philosopher and physicist. His philosophical writings combined scientific realism, systemism, materialism, emergentism, and other principles.

He was a ...

, a friend and colleague of Leloir, claims that his lasting legacy was proving that "scientific research on an international level, although precarious, was possible in an underdeveloped country in the middle of political strife" and credits Leloir's vigilance and will for his ultimate success. With his research in dire financial straits, Leloir often resorted to homemade gadgets and contraptions to continue his work in the laboratory. In one instance, Leloir reportedly used waterproof cardboard to create makeshift gutters in order to protect his laboratory's library from the rain.

Leloir was known for his humility, focus and consistency, described by many as a "true monk in science". Every morning his wife Amelia would drive him in their Fiat 600

The Fiat 600 (, ) is a small, rear-engined city car and Economy car, economy family car made by Italian carmaker Fiat Automobiles, Fiat from 1955 to 1969 — offered in two-door fastback sedan and four-door Multipla mini MPV body styles. The 60 ...

and drop him off at 1719 Julián Alvarez Street, location of Fundación Instituto Campomar, with Leloir wearing the same worn out, gray overalls. He worked sitting on the same straw seat for decades and encouraged colleagues to eat lunch in the laboratory to save time, bringing enough meat stew to share with everyone. Indeed, despite Leloir's frugality and extreme dedication to his research, he was a sociable man, claiming not to like working alone.

The Fundación Instituto Campomar has since been renamed Fundación Instituto Leloir, and has grown to become a building with 20 senior researchers, 42 technicians and administrative personnel, 8 post doctorate fellows, and 20 Ph.D. candidates. The institute conducts research in a variety of fields, including Alzheimer's disease

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disease and the cause of 60–70% of cases of dementia. The most common early symptom is difficulty in remembering recent events. As the disease advances, symptoms can include problems wit ...

, Parkinson's disease

Parkinson's disease (PD), or simply Parkinson's, is a neurodegenerative disease primarily of the central nervous system, affecting both motor system, motor and non-motor systems. Symptoms typically develop gradually and non-motor issues become ...

, and multiple sclerosis

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an autoimmune disease resulting in damage to myelinthe insulating covers of nerve cellsin the brain and spinal cord. As a demyelinating disease, MS disrupts the nervous system's ability to Action potential, transmit ...

.Awards and distinctions

Bibliography

* Lorenzano, Julio César. Por los caminos de Leloir. Editorial Biblos; 1a edition, July 1994. ISBN 9-5078-6063-0 * Zuberbuhler de Leloir, Amelia. Retrato personal de Leloir. Vol. 8, No. 25, pp. 45–46, 1983. * Nachón, Carlos Alberto. Luis Federico Leloir: ensayo de una biografía. Bank Foundation of Boston, 1994.References

External links

Fundación Instituto Leloir

The Official Site of Louisa Gross Horwitz Prize

{{DEFAULTSORT:Leloir, Luis Federico 1906 births 1987 deaths Physicians from Buenos Aires Argentine biochemists Argentine Nobel laureates Columbia University faculty Illustrious Citizens of Buenos Aires Nobel laureates in Chemistry Foreign members of the Royal Society Foreign associates of the National Academy of Sciences Washington University in St. Louis faculty University of Buenos Aires alumni Burials at La Recoleta Cemetery TWAS fellows 20th-century Argentine biologists International members of the American Philosophical Society 20th-century Argentine physicians