Latin Catholicism on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Latin Church () is the largest autonomous ()

For Augustine, the

For Augustine, the

"Saint Augustine in the Greek Orthodox Tradition"

goarch.org was rejected by the Orthodox Church as heretical. Other disputed teachings include his views on original sin, the doctrine of grace, and

Saint

Saint

''Gregory Palamas – The Triads''

p. xi. Paulist Press, 1983, , although that attitude has never been universally prevalent in the Catholic Church and has been even more widely criticised in the catholic theology for the last century (see section 3 of this article). Retrieved on 12 September 2014."No doubt the leaders of the party held aloof from these vulgar practices of the more ignorant monks, but on the other hand they scattered broadcast perilous theological theories. Palamas taught that by asceticism one could attain a corporal, i.e. a sense view, or perception, of the Divinity. He also held that in God there was a real distinction between the Divine Essence and Its attributes, and he identified grace as one of the Divine propria making it something uncreated and infinite. These monstrous errors were denounced by the Calabrian Barlaam, by Nicephorus Gregoras, and by Acthyndinus. The conflict began in 1338 and ended only in 1368, with the solemn canonization of Palamas and the official recognition of his heresies. He was declared the 'holy doctor' and 'one of the greatest among the Fathers of the Church', and his writings were proclaimed 'the infallible guide of the Christian Faith'. Thirty years of incessant controversy and discordant councils ended with a resurrection of polytheism" Further, the associated practice of

Simon Vailhé, "Greek Church" in ''Catholic Encyclopedia'' (New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1909)

/ref> More recently, some Roman Catholic thinkers have taken a positive view of Palamas's teachings, including the essence-energies distinction, arguing that it does not represent an insurmountable theological division between Roman Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy,Michael J. Christensen, Jeffery A. Wittung (editors), ''Partakers of the Divine Nature''(Associated University Presses 2007 ), pp. 243–244 and his feast day as a saint is celebrated by some

/ref> interpolation in the Creed at the

an

same document on another site

/ref>Ρωμαϊκό Λειτουργικό (Roman Missal), Συνοδική Επιτροπή για τη θεία Λατρεία 2005, I, p. 347 although it was never adopted by Eastern Catholic Churches.Article 1 of the Treaty of Brest

/ref>

Another doctrine of Latin Christianity is

Another doctrine of Latin Christianity is

2 Macc 12:46

The idea of purgatory has roots that date back into antiquity. A sort of proto-purgatory called the "celestial

in Encyclopædia Britannica Among other reasons, Western Catholic teaching of purgatory is based on the pre-Christian (Judaic) practice of Specific examples of belief in a purification after death and of the communion of the living with the dead through prayer are found in many of the

Specific examples of belief in a purification after death and of the communion of the living with the dead through prayer are found in many of the

Some Catholic saints and theologians have had sometimes conflicting ideas about purgatory beyond those adopted by the Catholic Church, reflecting or contributing to the popular image, which includes the notions of purification by actual fire, in a determined place and for a precise length of time. Paul J. Griffiths notes: "Recent Catholic thought on purgatory typically preserves the essentials of the basic doctrine while also offering second-hand speculative interpretations of these elements." Thus

Some Catholic saints and theologians have had sometimes conflicting ideas about purgatory beyond those adopted by the Catholic Church, reflecting or contributing to the popular image, which includes the notions of purification by actual fire, in a determined place and for a precise length of time. Paul J. Griffiths notes: "Recent Catholic thought on purgatory typically preserves the essentials of the basic doctrine while also offering second-hand speculative interpretations of these elements." Thus

In the medieval Western tradition,

In the medieval Western tradition,

St. Mary Magdalen

in The

, From East to West. But since Vatican II there has been development in Catholic thinking. Some warn against taking Genesis 3 too literally. They take into account that "God had the church in mind before the foundation of the world" (as in Ephesians 1:4). as also in 2 Timothy 1:9: ". . . his own purpose and grace, which was given us in Christ Jesus ''before'' the world began." And

/ref> But it is claimed that the doctrine is implicitly contained in the teaching of the Fathers. Their expressions on the subject of the sinlessness of Mary are, it is pointed out, so ample and so absolute that they must be taken to include original sin as well as actual. Thus in the first five centuries, such epithets as "in every respect holy", "in all things unstained", "super-innocent", and "singularly holy" are applied to her; she is compared to Eve before the fall, as ancestress of a redeemed people; she is "the earth before it was accursed". The well-known words of St.

The Blessed

The Blessed

The

The  The point of her bodily death has not been infallibly defined by any pope. Many Catholics believe that she did not die at all, but was assumed directly into Heaven. The dogmatic definition within the Apostolic Constitution which, according to Roman Catholic dogma, infallibly proclaims the doctrine of the Assumption leaves open the question of whether, in connection with her departure, Mary underwent bodily death. It does not dogmatically define the point one way or the other, as shown by the words "having completed the course of her earthly life".

Before the dogmatic definition in ''

The point of her bodily death has not been infallibly defined by any pope. Many Catholics believe that she did not die at all, but was assumed directly into Heaven. The dogmatic definition within the Apostolic Constitution which, according to Roman Catholic dogma, infallibly proclaims the doctrine of the Assumption leaves open the question of whether, in connection with her departure, Mary underwent bodily death. It does not dogmatically define the point one way or the other, as shown by the words "having completed the course of her earthly life".

Before the dogmatic definition in ''

Many Catholics also believe that Mary first died before being assumed, but they believe that she was miraculously resurrected before being assumed. Others believe she was assumed bodily into Heaven without first dying. Either understanding may be legitimately held by Catholics, with

Many Catholics also believe that Mary first died before being assumed, but they believe that she was miraculously resurrected before being assumed. Others believe she was assumed bodily into Heaven without first dying. Either understanding may be legitimately held by Catholics, with

Artistic depictions of God the Father were uncontroversial in Catholic art thereafter, but less common depictions of the

Artistic depictions of God the Father were uncontroversial in Catholic art thereafter, but less common depictions of the

Official website of the Holy See

(in the ''

particular church

In metaphysics, particulars or individuals are usually contrasted with ''universals''. Universals concern features that can be exemplified by various different particulars. Particulars are often seen as concrete, spatiotemporal entities as opposed ...

within the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

, whose members constitute the vast majority of the 1.3 billion Catholics. The Latin Church is one of 24 ''sui iuris'' churches in full communion

Full communion is a communion or relationship of full agreement among different Christian denominations or Christian individuals that share certain essential principles of Christian theology. Views vary among denominations on exactly what constit ...

with the pope

The pope is the bishop of Rome and the Head of the Church#Catholic Church, visible head of the worldwide Catholic Church. He is also known as the supreme pontiff, Roman pontiff, or sovereign pontiff. From the 8th century until 1870, the po ...

; the other 23 are collectively referred to as the Eastern Catholic Churches

The Eastern Catholic Churches or Oriental Catholic Churches, also known as the Eastern-Rite Catholic Churches, Eastern Rite Catholicism, or simply the Eastern Churches, are 23 Eastern Christian autonomous (''sui iuris'') particular churches of ...

, and they have approximately 18 million members combined.

The Latin Church is directly headed by the pope in his role as the bishop of Rome

The pope is the bishop of Rome and the visible head of the worldwide Catholic Church. He is also known as the supreme pontiff, Roman pontiff, or sovereign pontiff. From the 8th century until 1870, the pope was the sovereign or head of sta ...

, whose ''cathedra

A ''cathedra'' is the throne of a bishop in the early Christian basilica. When used with this meaning, it may also be called the bishop's throne. With time, the related term ''cathedral'' became synonymous with the "seat", or principa ...

'' as a bishop is located in the Archbasilica of Saint John Lateran

The Archbasilica of Saint John Lateran (officially the ''Major Papal, Patriarchal and Roman Archbasilica, Metropolitan and Primatial Cathedral of the Most Holy Savior and Saints John the Baptist and the Evangelist in Lateran, Mother and Head of A ...

in Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

, Italy. The Latin Church both developed within and strongly influenced Western culture

Western culture, also known as Western civilization, European civilization, Occidental culture, Western society, or simply the West, refers to the Cultural heritage, internally diverse culture of the Western world. The term "Western" encompas ...

; as such, it is sometimes called the Western Church (), which is reflected in one of the pope's traditional titles in some eras and contexts, the Patriarch of the West

Patriarch of the West () is one of the official titles of the Bishop of Rome, as patriarch and highest authority of the Latin Church.

History

The origin of the definition of the patriarch of the West is linked to the disestablishment of the ...

. It is also known as the Roman Church (), the Latin Catholic Church, and in some contexts as the Roman Catholic Church (though this name can also refer to the Catholic Church as a whole).

The Latin Church was in full communion with what is referred to as the Eastern Orthodox Church

The Eastern Orthodox Church, officially the Orthodox Catholic Church, and also called the Greek Orthodox Church or simply the Orthodox Church, is List of Christian denominations by number of members, one of the three major doctrinal and ...

until the East–West Schism

The East–West Schism, also known as the Great Schism or the Schism of 1054, is the break of communion (Christian), communion between the Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox Church. A series of Eastern Orthodox – Roman Catholic eccle ...

of Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

and Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

in 1054. From that time, but also before it, it became common to refer to Western Christians as ''Latins

The term Latins has been used throughout history to refer to various peoples, ethnicities and religious groups using Latin or the Latin-derived Romance languages, as part of the legacy of the Roman Empire. In the Ancient World, it referred to th ...

'' in contrast to Byzantines or Greeks.

The Latin Church employs the Latin liturgical rites

Latin liturgical rites, or Western liturgical rites, is a large family of ritual family, liturgical rites and Use (liturgy), uses of public worship employed by the Latin Church, the largest particular church ''sui iuris'' of the Catholic Church ...

, which since the mid-20th century are very often translated into the vernacular

Vernacular is the ordinary, informal, spoken language, spoken form of language, particularly when perceptual dialectology, perceived as having lower social status or less Prestige (sociolinguistics), prestige than standard language, which is mor ...

. The predominant liturgical rite

Rites (), liturgical rites, and ritual families within Christian liturgy refer to the families of liturgies, rituals, prayers, and other practices historically connected to a place, denomination, or group. Rites often interact with one another, ...

is the Roman Rite

The Roman Rite () is the most common ritual family for performing the ecclesiastical services of the Latin Church, the largest of the ''sui iuris'' particular churches that comprise the Catholic Church. The Roman Rite governs Rite (Christianity) ...

, elements of which have been practiced since the fourth century. There exist and have existed since ancient times additional Latin liturgical rites and uses, including the currently used Mozarabic Rite in restricted use in Spain, the Ambrosian Rite

The Ambrosian Rite () is a Latin liturgical rites, Latin liturgical rite of the Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox Church (specifically The Divine Liturgy of Saint Ambrose). The ritual family, rite is named after Ambrose, Saint Ambrose, a b ...

in parts of Italy, and the Anglican Use

The Anglican Use, also known as ''Divine Worship'', is a use of the Roman Rite celebrated by the personal ordinariates, originally created for former Anglicans who converted to Catholicism while wishing to maintain "aspects of the Anglican p ...

in the personal ordinariate

A personal ordinariate for former Anglicans, shortened as personal ordinariate or Anglican ordinariate,"Bishop Stephen Lopes of the Anglican Ordinariate of the Chair of St Peter..." is a canonical structure within the Catholic Church establis ...

s.

In the early modern period

The early modern period is a Periodization, historical period that is defined either as part of or as immediately preceding the modern period, with divisions based primarily on the history of Europe and the broader concept of modernity. There i ...

and subsequently, the Latin Church carried out evangelizing missions to the Americas

The Americas, sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North America and South America.''Webster's New World College Dictionary'', 2010 by Wiley Publishing, Inc., Cleveland, Ohio. When viewed as a sing ...

, and from the late modern period

In many periodizations of human history, the late modern period followed the early modern period. It began around 1800 and, depending on the author, either ended with the beginning of contemporary history in 1945, or includes the contemporary h ...

to Sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa is the area and regions of the continent of Africa that lie south of the Sahara. These include Central Africa, East Africa, Southern Africa, and West Africa. Geopolitically, in addition to the list of sovereign states and ...

and East Asia

East Asia is a geocultural region of Asia. It includes China, Japan, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea, and Taiwan, plus two special administrative regions of China, Hong Kong and Macau. The economies of Economy of China, China, Economy of Ja ...

. The Protestant Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the papacy and ...

in the 16th century resulted in Protestantism

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

breaking away, resulting in the fragmentation of Western Christianity

Western Christianity is one of two subdivisions of Christianity (Eastern Christianity being the other). Western Christianity is composed of the Latin Church and Protestantism, Western Protestantism, together with their offshoots such as the O ...

, including not only Protestant offshoots of the Latin Church, but also smaller groups of 19th-century break-away Independent Catholic denominations

This is a list of Independent Catholic denominations, current and defunct, which identify as Catholic but are not in communion with the Holy See.

Denominations of Roman Catholic tradition

* Apostolic Catholic Church

* Apostles of Infinite ...

.

Terminology

Name

The historical part of the Catholic Church in the West is called the Latin Church to distinguish itself from the Eastern Catholic Churches which are also under the pope's primacy. In historical context, before theEast–West Schism

The East–West Schism, also known as the Great Schism or the Schism of 1054, is the break of communion (Christian), communion between the Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox Church. A series of Eastern Orthodox – Roman Catholic eccle ...

in 1054 the Latin Church is sometimes referred to as the ''Western Church''. Writers belonging to various Protestant denominations sometime use the term ''Western Church'' as an implicit claim to legitimacy.

The term ''Latin Catholic'' refers to followers of the Latin liturgical rites

Latin liturgical rites, or Western liturgical rites, is a large family of ritual family, liturgical rites and Use (liturgy), uses of public worship employed by the Latin Church, the largest particular church ''sui iuris'' of the Catholic Church ...

, of which the Roman Rite

The Roman Rite () is the most common ritual family for performing the ecclesiastical services of the Latin Church, the largest of the ''sui iuris'' particular churches that comprise the Catholic Church. The Roman Rite governs Rite (Christianity) ...

is predominant. The Latin liturgical rites are contrasted with the liturgical rites of the Eastern Catholic Churches.

"Church" and "rite"

The 1990Code of Canons of the Eastern Churches

The ''Code of Canons of the Eastern Churches'' (CCEC; , abbreviated CCEO) is the title of the 1990 work which is a codification of the common portions of the canon law for the 23 Eastern Catholic Churches in the Catholic Church. It is divided i ...

defines the use within that code of the words "church" and "rite". In accordance with these definitions of usage within the code that governs the Eastern Catholic Churches

The Eastern Catholic Churches or Oriental Catholic Churches, also known as the Eastern-Rite Catholic Churches, Eastern Rite Catholicism, or simply the Eastern Churches, are 23 Eastern Christian autonomous (''sui iuris'') particular churches of ...

, the Latin Church is one such group of Christian faithful united by a hierarchy and recognized by the supreme authority of the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

as a ''sui iuris'' particular Church. The "Latin Rite" is the whole of the patrimony of that distinct particular church, by which it manifests its own manner of living the faith, including its own liturgy, its theology, its spiritual practices and traditions and its canon law. A Catholic, as an individual person, is necessarily a member of a particular church. A person also inherits, or "is of", a particular patrimony or rite. Since the rite has liturgical, theological, spiritual and disciplinary elements, a person is also to worship, to be catechized, to pray and to be governed according to a particular rite.

Particular churches that inherit and perpetuate a particular patrimony are identified by the metonymy

Metonymy () is a figure of speech in which a concept is referred to by the name of something associated with that thing or concept. For example, the word " suit" may refer to a person from groups commonly wearing business attire, such as sales ...

"church" or "rite". Accordingly, "Rite" has been defined as "a division of the Christian Church using a distinctive liturgy", or simply as "a Christian Church". In this sense, "Rite" and "Church" are treated as synonymous, as in the glossary prepared by the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops and revised in 1999, which states that each "Eastern-rite (Oriental) Church ... is considered equal to the Latin rite within the Church". The Second Vatican Council likewise stated that "it is the mind of the Catholic Church that each individual Church or Rite should retain its traditions whole and entire and likewise that it should adapt its way of life to the different needs of time and place" and spoke of patriarchs and of "major archbishops, who rule the whole of some individual Church or Rite". It thus used the word "Rite" as "a technical designation of what may now be called a particular Church". "Church or rite" is also used as a single heading in the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

Library of Congress classification of works.

History

Historically, the governing entity of the Latin Church (i.e. theHoly See

The Holy See (, ; ), also called the See of Rome, the Petrine See or the Apostolic See, is the central governing body of the Catholic Church and Vatican City. It encompasses the office of the pope as the Bishops in the Catholic Church, bishop ...

) has been viewed as one of the five patriarchates

Patriarchate (, ; , ''patriarcheîon'') is an ecclesiological term in Christianity, referring to the office and jurisdiction of a patriarch.

According to Christian tradition, three patriarchates—Rome, Antioch, and Alexandria—were establish ...

of the Pentarchy

Pentarchy (, ) was a model of Church organization formulated in the laws of Emperor Justinian I () of the Roman Empire. In this model, the Christian Church is governed by the heads (patriarchs) of the five major episcopal sees of the Roman Em ...

of early Christianity

Early Christianity, otherwise called the Early Church or Paleo-Christianity, describes the History of Christianity, historical era of the Christianity, Christian religion up to the First Council of Nicaea in 325. Spread of Christianity, Christian ...

, along with the patriarchates of Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

, Alexandria

Alexandria ( ; ) is the List of cities and towns in Egypt#Largest cities, second largest city in Egypt and the List of coastal settlements of the Mediterranean Sea, largest city on the Mediterranean coast. It lies at the western edge of the Nile ...

, Antioch

Antioch on the Orontes (; , ) "Antioch on Daphne"; or "Antioch the Great"; ; ; ; ; ; ; . was a Hellenistic Greek city founded by Seleucus I Nicator in 300 BC. One of the most important Greek cities of the Hellenistic period, it served as ...

, and Jerusalem

Jerusalem is a city in the Southern Levant, on a plateau in the Judaean Mountains between the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and the Dead Sea. It is one of the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest cities in the world, and ...

. Due to geographic and cultural considerations, the latter patriarchates developed into churches with distinct Eastern Christian

Eastern Christianity comprises Christianity, Christian traditions and Christian denomination, church families that originally developed during Classical antiquity, classical and late antiquity in the Eastern Mediterranean region or locations fu ...

traditions. This scheme, tacitly at least accepted by Rome, is constructed from the viewpoint of Greek Christianity and does not take into consideration other churches of great antiquity which developed in the East outside the frontiers of the Roman Empire. The majority of Eastern Christian Churches broke full communion with the Bishop of Rome and the Latin Church, following various theological and jurisdictional disputes in the centuries following the Council of Chalcedon

The Council of Chalcedon (; ) was the fourth ecumenical council of the Christian Church. It was convoked by the Roman emperor Marcian. The council convened in the city of Chalcedon, Bithynia (modern-day Kadıköy, Istanbul, Turkey) from 8 Oct ...

in AD 451. These included notably the Nestorian Schism (431–544) (Church of the East

The Church of the East ( ) or the East Syriac Church, also called the Church of Seleucia-Ctesiphon, the Persian Church, the Assyrian Church, the Babylonian Church, the Chaldean Church or the Nestorian Church, is one of three major branches o ...

), Chalcedonian Schism (451) (Oriental Orthodoxy

The Oriental Orthodox Churches are Eastern Christian churches adhering to Miaphysite Christology, with approximately 50 million members worldwide. The Oriental Orthodox Churches adhere to the Nicene Christian tradition. Oriental Orthodoxy is ...

), and the East-West Schism

East West (or East and West) may refer to:

*East–West dichotomy, the contrast between Eastern and Western society or culture

Arts and entertainment

Books, journals and magazines

*'' East, West'', an anthology of short stories written by Salm ...

(1054) (Eastern Orthodoxy

Eastern Orthodoxy, otherwise known as Eastern Orthodox Christianity or Byzantine Christianity, is one of the three main Branches of Christianity, branches of Chalcedonian Christianity, alongside Catholic Church, Catholicism and Protestantism ...

). The Protestant Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the papacy and ...

of the 16th century saw a schism which was not analogous since it was not based upon the same historical factors and involved far more profound theological dissent from the teaching of the totality of previously existing historical Christian churches. Until 2006, the pope claimed the title "patriarch of the West

Patriarch of the West () is one of the official titles of the Bishop of Rome, as patriarch and highest authority of the Latin Church.

History

The origin of the definition of the patriarch of the West is linked to the disestablishment of the ...

"; Benedict XVI

Pope BenedictXVI (born Joseph Alois Ratzinger; 16 April 1927 – 31 December 2022) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 19 April 2005 until resignation of Pope Benedict XVI, his resignation on 28 Februar ...

set aside this title. In 2024, Pope Francis

Pope Francis (born Jorge Mario Bergoglio; 17 December 1936 – 21 April 2025) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 13 March 2013 until Death and funeral of Pope Francis, his death in 2025. He was the fi ...

reinstated patriarch of the West as one of the official papal titles

The titles of the Bishop of Rome, more often referred to as the papal titles, refer to the various titles used by Etiquette, protocol, as a Style (form of address), form of addressing or designating a theological or secular reality of the Pope, ...

.

Following the Islamic conquests

The early Muslim conquests or early Islamic conquests (), also known as the Arab conquests, were initiated in the 7th century by Muhammad, the founder of Islam. He established the first Islamic state in Medina, Arabia that expanded rapidly un ...

, the Crusades

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and at times directed by the Papacy during the Middle Ages. The most prominent of these were the campaigns to the Holy Land aimed at reclaiming Jerusalem and its surrounding t ...

were launched by the West from 1095 to 1291 in order to defend Christians and their properties in the Holy Land

The term "Holy Land" is used to collectively denote areas of the Southern Levant that hold great significance in the Abrahamic religions, primarily because of their association with people and events featured in the Bible. It is traditionall ...

against persecution

Persecution is the systematic mistreatment of an individual or group by another individual or group. The most common forms are religious persecution, racism, and political persecution, though there is naturally some overlap between these term ...

. In the long term the Crusaders did not succeed in re-establishing political and military control of Palestine, which like former Christian North Africa and the rest of the Middle East remained under Islamic control. The names of many former Christian dioceses of this vast area are still used by the Catholic Church as the names of Catholic titular sees, irrespective of the question of liturgical families.

In the High Middle Ages

The High Middle Ages, or High Medieval Period, was the periodization, period of European history between and ; it was preceded by the Early Middle Ages and followed by the Late Middle Ages, which ended according to historiographical convention ...

began the development of Scholasticism

Scholasticism was a medieval European philosophical movement or methodology that was the predominant education in Europe from about 1100 to 1700. It is known for employing logically precise analyses and reconciling classical philosophy and Ca ...

in the Latin Church, which saw to reconcile the rediscovery of Classial Greek works such as those of Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

with Christianity. Under that came new theologians such as Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas ( ; ; – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican Order, Dominican friar and Catholic priest, priest, the foremost Scholasticism, Scholastic thinker, as well as one of the most influential philosophers and theologians in the W ...

and Anselm of Canterbury

Anselm of Canterbury OSB (; 1033/4–1109), also known as (, ) after his birthplace and () after his monastery, was an Italian Benedictine monk, abbot, philosopher, and theologian of the Catholic Church, who served as Archbishop of Canterb ...

who believed that faith and reason could exist without any contradiction.

During the Age of Discovery, the Latin Church spread to the Americas and the Philippines under the colonial powers of Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

and Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic, is a country on the Iberian Peninsula in Southwestern Europe. Featuring Cabo da Roca, the westernmost point in continental Europe, Portugal borders Spain to its north and east, with which it share ...

, which Pope Alexander VI

Pope Alexander VI (, , ; born Roderic Llançol i de Borja; epithet: ''Valentinus'' ("The Valencian"); – 18 August 1503) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 11 August 1492 until his death in 1503.

Born into t ...

in the papal bull

A papal bull is a type of public decree, letters patent, or charter issued by the pope of the Catholic Church. It is named after the leaden Seal (emblem), seal (''bulla (seal), bulla'') traditionally appended to authenticate it.

History

Papal ...

Inter caetera

''Inter caetera'' ('Among other

awarded colonial rights to. Koschorke, K. ''A History of Christianity in Asia, Africa, and Latin America'' (2007), pp. 13, 283 The orks

Ork or ORK may refer to:

* Ork (folklore), a mountain demon of Tyrol folklore

* ''Ork'' (video game), a 1991 game for the Amiga and Atari ST systems

* Ork (''Warhammer 40,000''), a fictional species in the ''Warhammer 40,000'' universe

* '' Ork!' ...

) was a papal bull issued by Pope Alexander VI on the 4 May 1493, which granted to the Catholic Monarchs Ferdinand II of Aragon, King Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile, Queen Isabella I of ...French colonization of the Americas

France began colonizing America in the 16th century and continued into the following centuries as it established a colonial empire in the Western Hemisphere. France established colonies in much of eastern North America, on several Caribbean is ...

beginning in the 16th century established the French Latin Church in Quebec

Quebec is Canada's List of Canadian provinces and territories by area, largest province by area. Located in Central Canada, the province shares borders with the provinces of Ontario to the west, Newfoundland and Labrador to the northeast, ...

.

Membership

In the Catholic Church, in addition to the Latin Churchdirectly headed by the pope as Latin patriarch and notable withinWestern Christianity

Western Christianity is one of two subdivisions of Christianity (Eastern Christianity being the other). Western Christianity is composed of the Latin Church and Protestantism, Western Protestantism, together with their offshoots such as the O ...

for its sacred tradition

Sacred tradition, also called holy tradition, Anno Domini tradition or apostolic tradition, is a theological term used in Christian theology. According to this theological position, sacred Tradition and Scripture form one ''deposit'', so sacred T ...

and seven sacraments The expression seven sacraments mainly refers to:

* Sacrament

** Sacraments of the Catholic Church

** Eastern Orthodox Church § Holy mysteries (sacraments)

** Anglican sacraments

** Sacrament § Hussite Church and Moravian Church

It can also ref ...

there are 23 Eastern Catholic Churches

The Eastern Catholic Churches or Oriental Catholic Churches, also known as the Eastern-Rite Catholic Churches, Eastern Rite Catholicism, or simply the Eastern Churches, are 23 Eastern Christian autonomous (''sui iuris'') particular churches of ...

, self-governing particular church

In metaphysics, particulars or individuals are usually contrasted with ''universals''. Universals concern features that can be exemplified by various different particulars. Particulars are often seen as concrete, spatiotemporal entities as opposed ...

es sui iuris

''Sui iuris'' (), also spelled ''sui juris'', is a Latin phrase that literally means "of one's own right". It is used in both the Catholic Church's canon law and secular law. The term church ''sui iuris'' is used in the Catholic ''Code of Canon ...

with their own hierarchies. Most of these churches trace their origins to the other four patriarchates of the ancient pentarchy

Pentarchy (, ) was a model of Church organization formulated in the laws of Emperor Justinian I () of the Roman Empire. In this model, the Christian Church is governed by the heads (patriarchs) of the five major episcopal sees of the Roman Em ...

, but either never historically broke full communion or returned to it with the Papacy at some time. These differ from each other in liturgical rite

Rites (), liturgical rites, and ritual families within Christian liturgy refer to the families of liturgies, rituals, prayers, and other practices historically connected to a place, denomination, or group. Rites often interact with one another, ...

(ceremonies, vestments, chants, language), devotional traditions, theology

Theology is the study of religious belief from a Religion, religious perspective, with a focus on the nature of divinity. It is taught as an Discipline (academia), academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itse ...

, canon law

Canon law (from , , a 'straight measuring rod, ruler') is a set of ordinances and regulations made by ecclesiastical jurisdiction, ecclesiastical authority (church leadership) for the government of a Christian organization or church and its membe ...

, and clergy

Clergy are formal leaders within established religions. Their roles and functions vary in different religious traditions, but usually involve presiding over specific rituals and teaching their religion's doctrines and practices. Some of the ter ...

, but all maintain the same faith, and all see full communion with the pope as bishop of Rome

The pope is the bishop of Rome and the visible head of the worldwide Catholic Church. He is also known as the supreme pontiff, Roman pontiff, or sovereign pontiff. From the 8th century until 1870, the pope was the sovereign or head of sta ...

as essential to being Catholic as well as part of the one true church

The expression "one true church" refers to an ecclesiological position asserting that Jesus gave his authority in the Great Commission solely to a particular visible Christian institutional church—what is commonly called a denomination. This ...

as defined by the Four Marks of the Church

The Four Marks of the Church, also known as the Attributes of the Church, describes four distinctive adjectives of traditional Christian ecclesiology as expressed in the Nicene Creed completed at the First Council of Constantinople in AD 381: " e ...

in Catholic ecclesiology

Catholic ecclesiology is the theological study of the Catholic Church, its nature, organization and its "distinctive place in the economy of salvation through Christ". Such study shows a progressive development over time being further described ...

.

The approximately 18 million Eastern Catholics represent a minority of Christians in communion with the pope, compared to well over 1 billion Latin Catholics. Additionally, there are roughly 250 million Eastern Orthodox

Eastern Orthodoxy, otherwise known as Eastern Orthodox Christianity or Byzantine Christianity, is one of the three main Branches of Christianity, branches of Chalcedonian Christianity, alongside Catholic Church, Catholicism and Protestantism ...

and 86 million Oriental Orthodox

The Oriental Orthodox Churches are Eastern Christianity, Eastern Christian churches adhering to Miaphysitism, Miaphysite Christology, with approximately 50 million members worldwide. The Oriental Orthodox Churches adhere to the Nicene Christian ...

around the world that are not in union with Rome. Unlike the Latin Church, the pope does not exercise a direct patriarchal role over the Eastern Catholic churches and their faithful, instead encouraging their internal hierarchies, which while separate from that of the Latin Church and function analogously to it, and follow the traditions shared with the corresponding Eastern Christian churches in Eastern and Oriental Orthodoxy.

Organisation

Liturgical patrimony

Cardinal

Cardinal or The Cardinal most commonly refers to

* Cardinalidae, a family of North and South American birds

**''Cardinalis'', genus of three species in the family Cardinalidae

***Northern cardinal, ''Cardinalis cardinalis'', the common cardinal of ...

Joseph Ratzinger

Pope BenedictXVI (born Joseph Alois Ratzinger; 16 April 1927 – 31 December 2022) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 19 April 2005 until his resignation on 28 February 2013. Benedict's election as po ...

(later Pope Benedict XVI) described the Latin liturgical rites

Latin liturgical rites, or Western liturgical rites, is a large family of ritual family, liturgical rites and Use (liturgy), uses of public worship employed by the Latin Church, the largest particular church ''sui iuris'' of the Catholic Church ...

on 24 October 1998:

Today, the most common Latin liturgical rites are the Roman Rite

The Roman Rite () is the most common ritual family for performing the ecclesiastical services of the Latin Church, the largest of the ''sui iuris'' particular churches that comprise the Catholic Church. The Roman Rite governs Rite (Christianity) ...

—either the post-Vatican II

The Second Ecumenical Council of the Vatican, commonly known as the or , was the 21st and most recent Catholic ecumenical councils, ecumenical council of the Catholic Church. The council met each autumn from 1962 to 1965 in St. Peter's Basilic ...

Mass promulgated by Pope Paul VI

Pope Paul VI (born Giovanni Battista Enrico Antonio Maria Montini; 26 September 18976 August 1978) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 21 June 1963 until his death on 6 August 1978. Succeeding John XXII ...

in 1969 and revised by Pope John Paul II

Pope John Paul II (born Karol Józef Wojtyła; 18 May 19202 April 2005) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 16 October 1978 until Death and funeral of Pope John Paul II, his death in 2005.

In his you ...

in 2002 (the "Ordinary Form"), or the 1962 form of the Tridentine Mass

The Tridentine Mass, also known as the Extraordinary Form of the Roman Rite or ''usus antiquior'' (), Vetus Ordo or the Traditional Latin Mass (TLM) or the Traditional Rite, is the liturgy in the Roman Missal of the Catholic Church codified in ...

(the "Extraordinary Form"); the Ambrosian Rite

The Ambrosian Rite () is a Latin liturgical rites, Latin liturgical rite of the Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox Church (specifically The Divine Liturgy of Saint Ambrose). The ritual family, rite is named after Ambrose, Saint Ambrose, a b ...

; the Mozarabic Rite; and variations of the Roman Rite (such as the Anglican Use

The Anglican Use, also known as ''Divine Worship'', is a use of the Roman Rite celebrated by the personal ordinariates, originally created for former Anglicans who converted to Catholicism while wishing to maintain "aspects of the Anglican p ...

). The 23 Eastern Catholic Churches

The Eastern Catholic Churches or Oriental Catholic Churches, also known as the Eastern-Rite Catholic Churches, Eastern Rite Catholicism, or simply the Eastern Churches, are 23 Eastern Christian autonomous (''sui iuris'') particular churches of ...

employ five different families of liturgical rites. The Latin liturgical rites are used only in a single ''sui iuris

''Sui iuris'' (), also spelled ''sui juris'', is a Latin phrase that literally means "of one's own right". It is used in both the Catholic Church's canon law and secular law. The term church ''sui iuris'' is used in the Catholic ''Code of Canon ...

'' particular church.

Of other liturgical families, the main survivors are what is now referred to officially as the Hispano-Mozarabic Rite, still in restricted use in Spain; the Ambrosian Rite

The Ambrosian Rite () is a Latin liturgical rites, Latin liturgical rite of the Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox Church (specifically The Divine Liturgy of Saint Ambrose). The ritual family, rite is named after Ambrose, Saint Ambrose, a b ...

, centred geographically on the Archdiocese of Milan

The Archdiocese of Milan (; ) is a Latin Church ecclesiastical territory or archdiocese of the Catholic Church in Italy which covers the areas of Milan, Monza, Lecco and Varese. It has long maintained its own Latin liturgical rite usage, the Ambr ...

, in Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

, and much closer in form, though not specific content, to the Roman Rite; and the Carthusian Rite

Latin liturgical rites, or Western liturgical rites, is a large family of liturgical rites and uses of public worship employed by the Latin Church, the largest particular church ''sui iuris'' of the Catholic Church, that originated in Europe wh ...

, practised within the strict Carthusian monastic Order, which also employs in general terms forms similar to the Roman Rite, but with a number of significant divergences which have adapted it to the distinctive way of life of the Carthusians.

There once existed what is referred to as the Gallican Rite, used in Gaulish or Frankish territories. This was a conglomeration of varying forms, not unlike the present Hispano-Mozarabic Rite in its general structures, but never strictly codified and which from at least the seventh century was gradually infiltrated, and then eventually for the most part replaced, by liturgical texts and forms which had their origin in the diocese of Rome. Other former "Rites" in past times practised in certain religious orders and important cities were in truth usually partial variants upon the Roman Rite

The Roman Rite () is the most common ritual family for performing the ecclesiastical services of the Latin Church, the largest of the ''sui iuris'' particular churches that comprise the Catholic Church. The Roman Rite governs Rite (Christianity) ...

and have almost entirely disappeared from current use, despite limited nostalgic efforts at revival of some of them and a certain indulgence by the Roman authorities.

Disciplinary patrimony

Canon law for the Latin Church is codified in the ''Code of Canon Law Code of Canon Law () may refer to:

* '' Corpus Juris Canonici'' ('Body of Canon Law'), a collection of sources of canon law of the Catholic Church applicable to the Latin Church until 1918

* 1917 ''Code of Canon Law'', code of canon law for the Ca ...

'', of which there have been two codifications, the first promulgated by Pope Benedict XV

Pope Benedict XV (; ; born Giacomo Paolo Giovanni Battista della Chiesa, ; 21 November 1854 – 22 January 1922) was head of the Catholic Church from 1914 until his death in January 1922. His pontificate was largely overshadowed by World War I a ...

in 1917 and the second by Pope John Paul II

Pope John Paul II (born Karol Józef Wojtyła; 18 May 19202 April 2005) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 16 October 1978 until Death and funeral of Pope John Paul II, his death in 2005.

In his you ...

in 1983.

In the Latin Church, the norm for administration of confirmation

In Christian denominations that practice infant baptism, confirmation is seen as the sealing of the covenant (religion), covenant created in baptism. Those being confirmed are known as confirmands. The ceremony typically involves laying on o ...

is that, except when in danger of death, the person to be confirmed should "have the use of reason, be suitably instructed, properly disposed, and able to renew the baptismal promises", and "the administration of the Most Holy Eucharist

The Eucharist ( ; from , ), also called Holy Communion, the Blessed Sacrament or the Lord's Supper, is a Christianity, Christian Rite (Christianity), rite, considered a sacrament in most churches and an Ordinance (Christianity), ordinance in ...

to children requires that they have sufficient knowledge and careful preparation so that they understand the mystery of Christ according to their capacity and are able to receive the body of Christ with faith and devotion." In the Eastern Churches these sacraments are usually administered immediately after baptism

Baptism (from ) is a Christians, Christian sacrament of initiation almost invariably with the use of water. It may be performed by aspersion, sprinkling or affusion, pouring water on the head, or by immersion baptism, immersing in water eit ...

, even for an infant.

Celibacy

Celibacy (from Latin ''caelibatus'') is the state of voluntarily being unmarried, sexually abstinent, or both. It is often in association with the role of a religious official or devotee. In its narrow sense, the term ''celibacy'' is applied ...

, as a consequence of the duty to observe perfect continence, is obligatory for priest

A priest is a religious leader authorized to perform the sacred rituals of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and one or more deity, deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in parti ...

s in the Latin Church. An exception is made for married clergy from other churches, who join the Catholic Church; they may continue as married priests. In the Latin Church, a married man may not be admitted even to the diaconate unless he is legitimately destined to remain a deacon and not become a priest. Marriage after ordination is not possible, and attempting it can result in canonical penalties. The Eastern Catholic Churches, unlike the Latin Church, have a married clergy.

At the present time, Bishop

A bishop is an ordained member of the clergy who is entrusted with a position of Episcopal polity, authority and oversight in a religious institution. In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance and administration of di ...

s in the Latin Church are generally appointed by the pope

The pope is the bishop of Rome and the Head of the Church#Catholic Church, visible head of the worldwide Catholic Church. He is also known as the supreme pontiff, Roman pontiff, or sovereign pontiff. From the 8th century until 1870, the po ...

after hearing the advice of the various dicasteries

A dicastery (; ; from ) is the name of some departments in the Roman Curia of the Catholic Church.

''Pastor bonus''

'' Pastor bonus'' (1988) includes this definition:

''Praedicate evangelium''

Under the new structure of the Roman Curia cr ...

of the Roman Curia

The Roman Curia () comprises the administrative institutions of the Holy See and the central body through which the affairs of the Catholic Church are conducted. The Roman Curia is the institution of which the Roman Pontiff ordinarily makes use ...

, specifically the Congregation for Bishops

The Dicastery for Bishops, formerly named Congregation for Bishops (), is the department of the Roman Curia of the Catholic Church that oversees the selection of most new bishops. Its proposals require papal approval to take effect, but are usu ...

, the Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples

The Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples (CEP; ) was a congregation (Roman Curia), congregation of the Roman Curia of the Catholic Church in Rome, responsible for Catholic missions, missionary work and related activities. It is also kn ...

(for countries in its care), the Section for Relations with States

The Section for Relations with States or Second Section of the Secretariat of State is the body within the Roman Curia charged with dealing with matters that involve relations with civil governments. It has been part of the Vatican Secretariat of ...

of the Secretariat of State (for appointments that require the consent or prior notification of civil governments), and the Congregation for the Oriental Churches

The Dicastery for the Eastern Churches (also called the Dicastery for the Oriental Churches), previously named the Congregation for the Oriental Churches or Congregation for the Eastern Churches (), is a dicastery of the Roman Curia responsible f ...

(in the areas in its charge, even for the appointment of Latin bishops). The Congregations generally work from a "terna" or list of three names advanced to them by the local church, most often through the Apostolic Nuncio or the Cathedral Chapter in those places where the Chapter retains the right to nominate bishops.

Theology and philosophy

Augustinianism

Augustine of Hippo

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; ; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430) was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Africa. His writings deeply influenced the development of Western philosop ...

was a Roman African, philosopher

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

and bishop in the Catholic Church

In the Catholic Church, a bishop is an ordained minister who holds the fullness of the sacrament of holy orders and is responsible for teaching doctrine, governing Catholics in his jurisdiction, sanctifying the world and representing the c ...

. He helped shape Latin Christianity

The Latin Church () is the largest autonomous () particular church within the Catholic Church, whose members constitute the vast majority of the 1.3 billion Catholics. The Latin Church is one of 24 ''sui iuris'' churches in full communion wi ...

, and is viewed as one of the most important Church Fathers

The Church Fathers, Early Church Fathers, Christian Fathers, or Fathers of the Church were ancient and influential Christian theologians and writers who established the intellectual and doctrinal foundations of Christianity. The historical peri ...

in the Latin Church for his writings in the Patristic Period. Among his works are ''The City of God

''On the City of God Against the Pagans'' (), often called ''The City of God'', is a book of Christian philosophy written in Latin by Augustine of Hippo in the early 5th century AD. Augustine wrote the book to refute allegations that Christian ...

'', '' De doctrina Christiana'', and '' Confessions''.

In his youth he was drawn to Manichaeism

Manichaeism (; in ; ) is an endangered former major world religion currently only practiced in China around Cao'an,R. van den Broek, Wouter J. Hanegraaff ''Gnosis and Hermeticism from Antiquity to Modern Times''. SUNY Press, 1998 p. 37 found ...

and later to neoplatonism

Neoplatonism is a version of Platonic philosophy that emerged in the 3rd century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and religion. The term does not encapsulate a set of ideas as much as a series of thinkers. Among the common id ...

. After his baptism and conversion in 386, Augustine developed his own approach to philosophy and theology, accommodating a variety of methods and perspectives. Believing that the grace of Christ was indispensable to human freedom, he helped formulate the doctrine of original sin

Original sin () in Christian theology refers to the condition of sinfulness that all humans share, which is inherited from Adam and Eve due to the Fall of man, Fall, involving the loss of original righteousness and the distortion of the Image ...

and made seminal contributions to the development of just war theory

The just war theory () is a doctrine, also referred to as a tradition, of military ethics that aims to ensure that a war is morally justifiable through a series of #Criteria, criteria, all of which must be met for a war to be considered just. I ...

. His thoughts profoundly influenced the medieval worldview. The segment of the church that adhered to the concept of the Trinity

The Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the Christian doctrine concerning the nature of God, which defines one God existing in three, , consubstantial divine persons: God the Father, God the Son (Jesus Christ) and God the Holy Spirit, thr ...

as defined by the Council of Nicaea and the Council of Constantinople closely identified with Augustine's ''On the Trinity

''On the Trinity'' () is a Latin book written by Augustine of Hippo to discuss the Trinity in context of the Logos. Although not as well known as some of his other works, some scholars have seen it as his masterpiece, of more doctrinal importance ...

''

When the Western Roman Empire

In modern historiography, the Western Roman Empire was the western provinces of the Roman Empire, collectively, during any period in which they were administered separately from the eastern provinces by a separate, independent imperial court. ...

began to disintegrate, Augustine imagined the church as a spiritual City of God, distinct from the material Earthly City. in his book ''On the city of God against the pagans'', often called ''The City of God

''On the City of God Against the Pagans'' (), often called ''The City of God'', is a book of Christian philosophy written in Latin by Augustine of Hippo in the early 5th century AD. Augustine wrote the book to refute allegations that Christian ...

'', Augustine declared its message to be spiritual rather than political. Christianity, he argued, should be concerned with the mystical, heavenly city, the New Jerusalem

In the Book of Ezekiel in the Hebrew Bible, New Jerusalem (, ''YHWH šāmmā'', YHWH sthere") is Ezekiel's prophetic vision of a city centered on the rebuilt Holy Temple, to be established in Jerusalem, which would be the capital of the ...

, rather than with earthly politics.

''The City of God'' presents human history

History is the systematic study of the past, focusing primarily on the Human history, human past. As an academic discipline, it analyses and interprets evidence to construct narratives about what happened and explain why it happened. Some t ...

as a conflict between what Augustine calls the Earthly City (often colloquially referred to as the City of Man, but never by Augustine) and the City of God, a conflict that is destined to end in victory for the latter. The City of God is marked by people who forego earthly pleasure to dedicate themselves to the eternal truths of God, now revealed fully in the Christian faith. The Earthly City, on the other hand, consists of people who have immersed themselves in the cares and pleasures of the present, passing world.

For Augustine, the

For Augustine, the Logos

''Logos'' (, ; ) is a term used in Western philosophy, psychology and rhetoric, as well as religion (notably Logos (Christianity), Christianity); among its connotations is that of a rationality, rational form of discourse that relies on inducti ...

"took on flesh" in Christ, in whom the logos was present as in no other man. He strongly influenced Early Medieval Christian Philosophy.Handboek Geschiedenis van de Wijsbegeerte I, Article by Douwe Runia

Like other Church Fathers such as Athenagoras, Tertullian

Tertullian (; ; 155 – 220 AD) was a prolific Early Christianity, early Christian author from Roman Carthage, Carthage in the Africa (Roman province), Roman province of Africa. He was the first Christian author to produce an extensive co ...

, Clement of Alexandria

Titus Flavius Clemens, also known as Clement of Alexandria (; – ), was a Christian theology, Christian theologian and philosopher who taught at the Catechetical School of Alexandria. Among his pupils were Origen and Alexander of Jerusalem. A ...

and Basil of Caesarea

Basil of Caesarea, also called Saint Basil the Great (330 – 1 or 2 January 379) was an early Roman Christian prelate who served as Bishop of Caesarea in Cappadocia from 370 until his death in 379. He was an influential theologian who suppor ...

, Augustine "vigorously condemned the practice of induced abortion

Abortion is the early termination of a pregnancy by removal or expulsion of an embryo or fetus. Abortions that occur without intervention are known as miscarriages or "spontaneous abortions", and occur in roughly 30–40% of all pregnan ...

", and although he disapproved of an abortion during any stage of pregnancy, he made a distinction between early abortions and later ones. He acknowledged the distinction between "formed" and "unformed" fetuses mentioned in the Septuagint

The Septuagint ( ), sometimes referred to as the Greek Old Testament or The Translation of the Seventy (), and abbreviated as LXX, is the earliest extant Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible from the original Biblical Hebrew. The full Greek ...

translation of , which is considered as wrong translation of the word "harm" from the original Hebrew text as "form" in the Greek Septuagint and based in Aristotelian distinction "between the fetus before and after its supposed 'vivification'", and did not classify as murder the abortion of an "unformed" fetus since he thought that it could not be said with certainty that the fetus had already received a soul.

Augustine also used the term "Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

" to distinguish the "true

True most commonly refers to truth, the state of being in congruence with fact or reality.

True may also refer to:

Places

* True, West Virginia, an unincorporated community in the United States

* True, Wisconsin, a town in the United States

* ...

" church from heretical groups:

In the Catholic Church, there are many other things which most justly keep me in her bosom. The consent of peoples and nations keeps me in the Church; so does her authority, inaugurated by miracles, nourished by hope, enlarged by love, established by age. The succession of priests keeps me, beginning from the very seat of theApostle Peter An apostle (), in its literal sense, is an emissary. The word is derived from Ancient Greek ἀπόστολος (''apóstolos''), literally "one who is sent off", itself derived from the verb ἀποστέλλειν (''apostéllein''), "to se ..., to whom the Lord, after His resurrection, gave it in charge to feed His sheep (Jn 21:15–19), down to the presentepiscopate A bishop is an ordained member of the clergy who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution. In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance and administration of dioceses. The role ....

And so, lastly, does the very name of Catholic, which, not without reason, amid so many heresies, the Church has thus retained; so that, though all heretics wish to be called Catholics, yet when a stranger asks where the Catholic Church meets, no heretic will venture to point to his own chapel or house.

Such then in number and importance are the precious ties belonging to the Christian name which keep a believer in the Catholic Church, as it is right they should. ...With you, there is none of these things to attract or keep me. ...No one shall move me from the faith which binds my mind with ties so many and so strong to the Christian religion. ...For my part, I should not believe the gospel except as moved by the authority of the Catholic Church. :— St. Augustine (354–430): ''Against the Epistle of Manichaeus called Fundamental'', chapter 4: Proofs of the Catholic Faith.In both his philosophical and theological reasoning, Augustine was greatly influenced by

Stoicism

Stoicism is a school of Hellenistic philosophy that flourished in ancient Greece and Rome. The Stoics believed that the universe operated according to reason, ''i.e.'' by a God which is immersed in nature itself. Of all the schools of ancient ...

, Platonism

Platonism is the philosophy of Plato and philosophical systems closely derived from it, though contemporary Platonists do not necessarily accept all doctrines of Plato. Platonism has had a profound effect on Western thought. At the most fundam ...

and Neoplatonism

Neoplatonism is a version of Platonic philosophy that emerged in the 3rd century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and religion. The term does not encapsulate a set of ideas as much as a series of thinkers. Among the common id ...

, particularly by the work of Plotinus

Plotinus (; , ''Plōtînos''; – 270 CE) was a Greek Platonist philosopher, born and raised in Roman Egypt. Plotinus is regarded by modern scholarship as the founder of Neoplatonism. His teacher was the self-taught philosopher Ammonius ...

, author of the ''Enneads

The ''Enneads'' (; ), fully ''The Six Enneads'', is the collection of writings of the philosopher Plotinus, edited and compiled by his student Porphyry (270). Plotinus was a student of Ammonius Saccas, and together they were founders of Neopla ...

'', probably through the mediation of Porphyry and Victorinus

Marcus Piavonius VictorinusSome of the inscriptions record his name as M. Piavvonius Victorinus, as does the first release of coins from the Colonia mint. A mosaic from Augusta Treverorum (Trier) lists him as Piaonius. was Gallic Empire, emperor ...

(as Pierre Hadot

Pierre Hadot (; ; 21 February 1922 – 24 April 2010) was a French philosopher and historian of philosophy specializing in ancient philosophy, particularly Neoplatonism, Epicureanism and Stoicism.

Life

In 1944, Hadot was ordained, but follow ...

has argued). Although he later abandoned Neoplatonism, some ideas are still visible in his early writings. His early and influential writing on the human will, a central topic in ethics

Ethics is the philosophy, philosophical study of Morality, moral phenomena. Also called moral philosophy, it investigates Normativity, normative questions about what people ought to do or which behavior is morally right. Its main branches inclu ...

, would become a focus for later philosophers such as Schopenhauer

Arthur Schopenhauer ( ; ; 22 February 1788 – 21 September 1860) was a German philosopher. He is known for his 1818 work '' The World as Will and Representation'' (expanded in 1844), which characterizes the phenomenal world as the manife ...

, Kierkegaard, and Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher. He began his career as a classical philologist, turning to philosophy early in his academic career. In 1869, aged 24, Nietzsche became the youngest pro ...

. He was also influenced by the works of Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; 15 October 70 BC21 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Rome, ancient Roman poet of the Augustan literature (ancient Rome), Augustan period. He composed three of the most fa ...

(known for his teaching on language), and Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, orator, writer and Academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises tha ...

(known for his teaching on argument).

In the East, his teachings are more disputed, and were notably attacked by John Romanides. But other theologians and figures of the Eastern Orthodox Church have shown significant approbation of his writings, chiefly Georges Florovsky

Georges Vasilievich Florovsky (; – August 11, 1979) was a Russian Orthodox priest, theologian, and historian.

Born in the Russian Empire, he spent his working life in Paris (1920–1949) and New York (1949–1979). With Sergei Bulgakov, V ...

. The most controversial doctrine associated with him, the filioque,Papademetriou, George C"Saint Augustine in the Greek Orthodox Tradition"

goarch.org was rejected by the Orthodox Church as heretical. Other disputed teachings include his views on original sin, the doctrine of grace, and

predestination

Predestination, in theology, is the doctrine that all events have been willed by God, usually with reference to the eventual fate of the individual soul. Explanations of predestination often seek to address the paradox of free will, whereby Go ...

. Nevertheless, though considered to be mistaken on some points, he is still considered a saint, and has even had influence on some Eastern Church Fathers, most notably the Greek theologian Gregory Palamas. In the Orthodox Church his feast day is celebrated on 15 June. Historian Diarmaid MacCulloch

Diarmaid Ninian John MacCulloch (; born 31 October 1951) is an English academic and historian, specialising in ecclesiastical history and the history of Christianity. Since 1995, he has been a fellow of St Cross College, Oxford; he was former ...

has written: " ugustine'simpact on Western Christian thought can hardly be overstated; only his beloved example Paul of Tarsus

Paul, also named Saul of Tarsus, commonly known as Paul the Apostle and Saint Paul, was a Apostles in the New Testament, Christian apostle ( AD) who spread the Ministry of Jesus, teachings of Jesus in the Christianity in the 1st century, first ...

has been more influential, and Westerners have generally seen Paul through Augustine's eyes."

In his autobiographical book ''Milestones'', Pope Benedict XVI

Pope BenedictXVI (born Joseph Alois Ratzinger; 16 April 1927 – 31 December 2022) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 19 April 2005 until his resignation on 28 February 2013. Benedict's election as p ...

claims Augustine as one of the deepest influences in his thought.

Scholasticism

Scholasticism

Scholasticism was a medieval European philosophical movement or methodology that was the predominant education in Europe from about 1100 to 1700. It is known for employing logically precise analyses and reconciling classical philosophy and Ca ...

is a method of critical thought

In their most common sense, the terms thought and thinking refer to cognitive processes that can happen independently of sensory stimulation. Their most paradigmatic forms are judging, reasoning, concept formation, problem solving, and de ...

which dominated teaching by the academics

Academic means of or related to an academy, an institution learning.

Academic or academics may also refer to:

* Academic staff, or faculty, teachers or research staff

* school of philosophers associated with the Platonic Academy in ancient Greece ...

("scholastics", or "schoolmen") of medieval universities

A medieval university was a Corporation#History, corporation organized during the Middle Ages for the purposes of higher education. The first Western European institutions generally considered to be University, universities were established in p ...

in Europe from about 1100 to 1700, The 13th and early 14th centuries are generally seen as the high period of scholasticism. The early 13th century witnessed the culmination of the recovery of Greek philosophy. Schools of translation grew up in Italy and Sicily, and eventually in the rest of Europe. Powerful Norman kings gathered men of knowledge from Italy and other areas into their courts as a sign of their prestige. William of Moerbeke

William of Moerbeke, Dominican Order, O.P. (; ; 1215–35 – 1286), was a prolific medieval translator of philosophical, medical, and scientific texts from Greek into Latin, enabled by the period of Latin Empire, Latin rule of the Byzanti ...

's translations and editions of Greek philosophical texts in the middle half of the thirteenth century helped form a clearer picture of Greek philosophy, particularly of Aristotle, than was given by the Arabic versions on which they had previously relied. Edward Grant

Edward Grant (April 6, 1926 – June 21, 2020) was an American historian of medieval science. He was named a distinguished professor in 1983. Other honors include the 1992 George Sarton Medal, for "a lifetime scholarly achievement" as an histor ...

writes: "Not only was the structure of the Arabic language radically different from that of Latin, but some Arabic versions had been derived from earlier Syriac translations and were thus twice removed from the original Greek text. Word-for-word translations of such Arabic texts could produce tortured readings. By contrast, the structural closeness of Latin to Greek permitted literal, but intelligible, word-for-word translations."Grant, Edward, and Emeritus Edward Grant. The foundations of modern science in the Middle Ages: their religious, institutional and intellectual contexts. Cambridge University Press, 1996, 23–28

Universities

A university () is an educational institution, institution of tertiary education and research which awards academic degrees in several Discipline (academia), academic disciplines. ''University'' is derived from the Latin phrase , which roughly ...

developed in the large cities of Europe during this period, and rival clerical orders within the church began to battle for political and intellectual control over these centers of educational life. The two main orders founded in this period were the Franciscans

The Franciscans are a group of related organizations in the Catholic Church, founded or inspired by the Italian saint Francis of Assisi. They include three independent religious orders for men (the Order of Friars Minor being the largest conte ...

and the Dominicans

Dominicans () also known as Quisqueyans () are an ethnic group, ethno-nationality, national people, a people of shared ancestry and culture, who have ancestral roots in the Dominican Republic.

The Dominican ethnic group was born out of a fusio ...

. The Franciscans were founded by Francis of Assisi

Giovanni di Pietro di Bernardone ( 1181 – 3 October 1226), known as Francis of Assisi, was an Italians, Italian Mysticism, mystic, poet and Friar, Catholic friar who founded the religious order of the Franciscans. Inspired to lead a Chris ...

in 1209. Their leader in the middle of the century was Bonaventure

Bonaventure ( ; ; ; born Giovanni di Fidanza; 1221 – 15 July 1274) was an Italian Catholic Franciscan bishop, Cardinal (Catholic Church), cardinal, Scholasticism, scholastic theologian and philosopher.

The seventh Minister General ( ...

, a traditionalist who defended the theology of Augustine

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; ; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430) was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Africa. His writings deeply influenced the development of Western philosop ...

and the philosophy of Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

, incorporating only a little of Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

in with the more neoplatonist elements. Following Anselm, Bonaventure supposed that reason can only discover truth when philosophy is illuminated by religious faith. Other important Franciscan scholastics were Duns Scotus

John Duns Scotus ( ; , "Duns the Scot"; – 8 November 1308) was a Scottish Catholic priest and Franciscan friar, university professor, philosopher and theologian. He is considered one of the four most important Christian philosopher-t ...

, Peter Auriol and William of Ockham

William of Ockham or Occam ( ; ; 9/10 April 1347) was an English Franciscan friar, scholastic philosopher, apologist, and theologian, who was born in Ockham, a small village in Surrey. He is considered to be one of the major figures of medie ...

.

Thomism

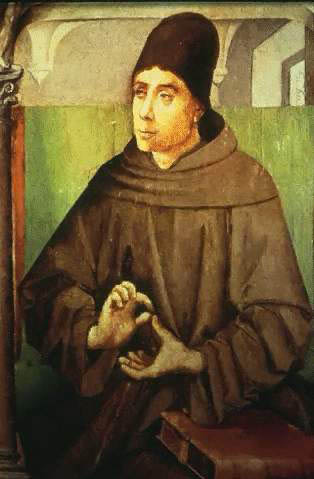

Saint

Saint Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas ( ; ; – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican Order, Dominican friar and Catholic priest, priest, the foremost Scholasticism, Scholastic thinker, as well as one of the most influential philosophers and theologians in the W ...

, an Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, a Romance ethnic group related to or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance languag ...

Dominican friar

A friar is a member of one of the mendicant orders in the Catholic Church. There are also friars outside of the Catholic Church, such as within the Anglican Communion. The term, first used in the 12th or 13th century, distinguishes the mendi ...

, philosopher

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

and priest

A priest is a religious leader authorized to perform the sacred rituals of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and one or more deity, deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in parti ...

, was immensely influential in the tradition of scholasticism, within which he is also known as the ''Doctor Angelicus'' and the ''Doctor Communis''.

Aquinas emphasized that "Synderesis