Lakumasaurus Antarcticus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Taniwhasaurus'' is an

The first known

The first known

In January 2000, paleontologist Juan M. Lirio discovered a remarkably well-preserved specimen of a mosasaur in the Gamma

In January 2000, paleontologist Juan M. Lirio discovered a remarkably well-preserved specimen of a mosasaur in the Gamma

Throughout the remainder of the 20th century, ''Tylosaurus capensis'' was generally viewed as a valid species within the genus, being identified primarily by the size of the parietal foramen and the suture between the frontal and

Throughout the remainder of the 20th century, ''Tylosaurus capensis'' was generally viewed as a valid species within the genus, being identified primarily by the size of the parietal foramen and the suture between the frontal and

In dorsal view, the skull of ''Taniwhasaurus'' is triangular in shape. Like other tylosaurines, the skull of is characterized by the presence of an edentulous

In dorsal view, the skull of ''Taniwhasaurus'' is triangular in shape. Like other tylosaurines, the skull of is characterized by the presence of an edentulous

The exact number of vertebrae in ''Taniwhasaurus'' is unknown, but the rare fossils concerning this part of the body include the cervical,

The exact number of vertebrae in ''Taniwhasaurus'' is unknown, but the rare fossils concerning this part of the body include the cervical,

A study published in 2020 based on

A study published in 2020 based on

Although the dorsal and caudal vertebrae of ''T. antarcticus'' are poorly preserved, they follow a very similar morphology to that of ''Tylosaurus'' and ''

Although the dorsal and caudal vertebrae of ''T. antarcticus'' are poorly preserved, they follow a very similar morphology to that of ''Tylosaurus'' and ''

''T. antarcticus'' is known from Late Campanian deposits of the

''T. antarcticus'' is known from Late Campanian deposits of the

extinct

Extinction is the termination of an organism by the death of its Endling, last member. A taxon may become Functional extinction, functionally extinct before the death of its last member if it loses the capacity to Reproduction, reproduce and ...

genus

Genus (; : genera ) is a taxonomic rank above species and below family (taxonomy), family as used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In bino ...

of mosasaur

Mosasaurs (from Latin ''Mosa'' meaning the 'Meuse', and Ancient Greek, Greek ' meaning 'lizard') are an extinct group of large aquatic reptiles within the family Mosasauridae that lived during the Late Cretaceous. Their first fossil remains wer ...

s (a group of extinct marine lizards) that lived during the Campanian

The Campanian is the fifth of six ages of the Late Cretaceous epoch on the geologic timescale of the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS). In chronostratigraphy, it is the fifth of six stages in the Upper Cretaceous Series. Campa ...

stage

Stage, stages, or staging may refer to:

Arts and media Acting

* Stage (theatre), a space for the performance of theatrical productions

* Theatre, a branch of the performing arts, often referred to as "the stage"

* ''The Stage'', a weekly Brit ...

of the Late Cretaceous

The Late Cretaceous (100.5–66 Ma) is the more recent of two epochs into which the Cretaceous Period is divided in the geologic time scale. Rock strata from this epoch form the Upper Cretaceous Series. The Cretaceous is named after ''cre ...

. It is a member of the subfamily

In biological classification, a subfamily (Latin: ', plural ') is an auxiliary (intermediate) taxonomic rank, next below family but more inclusive than genus. Standard nomenclature rules end botanical subfamily names with "-oideae", and zo ...

Tylosaurinae

The Tylosaurinae are a subfamily of mosasaurs,Williston, S. W. 1897. Range and distribution of the mosasaurs with remarks on synonymy. ''Kansas University Quarterly'' 4(4):177-185. a diverse group of Late Cretaceous marine squamates. Members of ...

, a lineage of mosasaurs characterized by a long toothless conical rostrum

Rostrum may refer to:

* Any kind of a platform for a speaker:

**dais

**pulpit

** podium

* Rostrum (anatomy), a beak, or anatomical structure resembling a beak, as in the mouthparts of many sucking insects

* Rostrum (ship), a form of bow on naval ...

. Two valid species

A species () is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate sexes or mating types can produce fertile offspring, typically by sexual reproduction. It is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), ...

are attached to the genus, ''T. oweni'' and ''T. antarcticus'', known respectively from the fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserve ...

record of present-day New Zealand

New Zealand () is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and List of islands of New Zealand, over 600 smaller islands. It is the List of isla ...

and Antarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean (also known as the Antarctic Ocean), it contains the geographic South Pole. ...

. ''T. capensis'' from present-day South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. Its Provinces of South Africa, nine provinces are bounded to the south by of coastline that stretches along the Atlantic O ...

represents a chimera

Chimera, Chimaera, or Chimaira (Greek for " she-goat") originally referred to:

* Chimera (mythology), a fire-breathing monster of ancient Lycia said to combine parts from multiple animals

* Mount Chimaera, a fire-spewing region of Lycia or Cilicia ...

of two different mosasaur genera, potentially ''Prognathodon

''Prognathodon'' is an extinct genus of marine lizard belonging to the mosasaur family. It is classified as part of the Mosasaurinae subfamily, alongside genera like ''Mosasaurus'' and ''Clidastes''. ''Prognathodon'' has been recovered from depos ...

'' and ''Taniwhasaurus'', but not identifiable at the species level. The other formerly assigned species, ''T. mikasaensis'' from present-day Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

, remains problematic due to the fragmentary state of the attributed fossils. The generic name literally means "taniwha

In Māori mythology, taniwha () are large supernatural beings that live in deep pools in rivers, dark caves, or in the sea, especially in places with dangerous currents or deceptive breakers (giant waves).

They may be considered highly respecte ...

lizard", referring to a supernatural aquatic creature from Māori mythology

Māori mythology and Māori traditions are two major categories into which the remote oral history of New Zealand's Māori people, Māori may be divided. Māori myths concern tales of supernatural events relating to the origins of what was the ...

.

''Taniwhasaurus'' is a medium-sized mosasaurid, with maximum size estimates putting it at around in length. The rare fossils of the axial skeleton

The axial skeleton is the core part of the endoskeleton made of the bones of the head and trunk of vertebrates. In the human skeleton, it consists of 80 bones and is composed of the skull (28 bones, including the cranium, mandible and the midd ...

indicate that the animal would have had great mobility in the vertebral column

The spinal column, also known as the vertebral column, spine or backbone, is the core part of the axial skeleton in vertebrates. The vertebral column is the defining and eponymous characteristic of the vertebrate. The spinal column is a segmente ...

, but the tail

The tail is the elongated section at the rear end of a bilaterian animal's body; in general, the term refers to a distinct, flexible appendage extending backwards from the midline of the torso. In vertebrate animals that evolution, evolved to los ...

would generate the main propulsive movement, a method of swimming proposed for other mosasaurids. The constitution of the forelimb

A forelimb or front limb is one of the paired articulated appendages ( limbs) attached on the cranial (anterior) end of a terrestrial tetrapod vertebrate's torso. With reference to quadrupeds, the term foreleg or front leg is often used inst ...

of ''Taniwhasaurus'' indicates that it would have had powerful paddles for swimming. CT scan

A computed tomography scan (CT scan), formerly called computed axial tomography scan (CAT scan), is a medical imaging technique used to obtain detailed internal images of the body. The personnel that perform CT scans are called radiographers or ...

s performed on the snout

A snout is the protruding portion of an animal's face, consisting of its nose, mouth, and jaw. In many animals, the structure is called a muzzle, Rostrum (anatomy), rostrum, beak or proboscis. The wet furless surface around the nostrils of the n ...

foramina

In anatomy and osteology, a foramen (; : foramina, or foramens ; ) is an opening or enclosed gap within the dense connective tissue (bones and deep fasciae) of extant and extinct amniote animals, typically to allow passage of nerves, arter ...

of ''T. antarcticus'' show that ''Taniwhasaurus'', like various aquatic predators today, would likely have had an electro-sensitive organ capable of detecting the movements of prey underwater.

The fossil record shows that both officially recognized species of ''Taniwhasaurus'' were endemic

Endemism is the state of a species being found only in a single defined geographic location, such as an island, state, nation, country or other defined zone; organisms that are indigenous to a place are not endemic to it if they are also foun ...

to the sea

A sea is a large body of salt water. There are particular seas and the sea. The sea commonly refers to the ocean, the interconnected body of seawaters that spans most of Earth. Particular seas are either marginal seas, second-order section ...

s of the ancient supercontinent

In geology, a supercontinent is the assembly of most or all of Earth's continent, continental blocks or cratons to form a single large landmass. However, some geologists use a different definition, "a grouping of formerly dispersed continents", ...

Gondwana

Gondwana ( ; ) was a large landmass, sometimes referred to as a supercontinent. The remnants of Gondwana make up around two-thirds of today's continental area, including South America, Africa, Antarctica, Australia (continent), Australia, Zea ...

, nevertheless living in different types of bodies of waterbodies

A body of water or waterbody is any significant accumulation of water on the surface of Earth or another planet. The term most often refers to oceans, seas, and lakes, but it includes smaller pools of water such as ponds, wetlands, or more ra ...

. Indeterminate specimens including the holotype of ''T. mikasaensis'' have also been found in Eurasia, but they are not diagnostic to the species level. The concerned geological formation

A geological formation, or simply formation, is a body of rock having a consistent set of physical characteristics (lithology) that distinguishes it from adjacent bodies of rock, and which occupies a particular position in the layers of rock expo ...

s shows that the genus shared its habitat with invertebrate

Invertebrates are animals that neither develop nor retain a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''spine'' or ''backbone''), which evolved from the notochord. It is a paraphyletic grouping including all animals excluding the chordata, chordate s ...

s, bony fish

Osteichthyes ( ; ), also known as osteichthyans or commonly referred to as the bony fish, is a Biodiversity, diverse clade of vertebrate animals that have endoskeletons primarily composed of bone tissue. They can be contrasted with the Chondricht ...

es, cartilaginous fish

Chondrichthyes (; ) is a class of jawed fish that contains the cartilaginous fish or chondrichthyans, which all have skeletons primarily composed of cartilage. They can be contrasted with the Osteichthyes or ''bony fish'', which have skeleto ...

es, and other marine reptile

Marine reptiles are reptiles which have become secondarily adapted for an aquatic or semiaquatic life in a marine environment. Only about 100 of the 12,000 extant reptile species and subspecies are classed as marine reptiles, including mari ...

s, including plesiosaur

The Plesiosauria or plesiosaurs are an Order (biology), order or clade of extinct Mesozoic marine reptiles, belonging to the Sauropterygia.

Plesiosaurs first appeared in the latest Triassic Period (geology), Period, possibly in the Rhaetian st ...

s and other mosasaurs.

Research history

Recognized species

''T. oweni''

The first known

The first known species

A species () is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate sexes or mating types can produce fertile offspring, typically by sexual reproduction. It is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), ...

, ''Taniwhasaurus oweni'', was discovered in the 1860s in the cliffs of Haumuri Bluff

Haumuri Bluff (also known as Amuri Bluff) is a headland on the coast of New Zealand's South Island on the south side of Piripaua (Spyglass Point), located several kilometres south of Oaro. It has been a major palaeontological site since the mid-1 ...

, located in the Conway Formation, eastern New Zealand

New Zealand () is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and List of islands of New Zealand, over 600 smaller islands. It is the List of isla ...

. This formation is dated from the Upper Cretaceous

The Late Cretaceous (100.5–66 Ma) is the more recent of two epochs into which the Cretaceous Period is divided in the geologic time scale. Rock strata from this epoch form the Upper Cretaceous Series. The Cretaceous is named after ''cret ...

, more precisely from the lower and middle Campanian

The Campanian is the fifth of six ages of the Late Cretaceous epoch on the geologic timescale of the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS). In chronostratigraphy, it is the fifth of six stages in the Upper Cretaceous Series. Campa ...

stage

Stage, stages, or staging may refer to:

Arts and media Acting

* Stage (theatre), a space for the performance of theatrical productions

* Theatre, a branch of the performing arts, often referred to as "the stage"

* ''The Stage'', a weekly Brit ...

. The first fossils formally attributed to this taxon

In biology, a taxon (back-formation from ''taxonomy''; : taxa) is a group of one or more populations of an organism or organisms seen by taxonomists to form a unit. Although neither is required, a taxon is usually known by a particular name and ...

were described by the Scottish

Scottish usually refers to something of, from, or related to Scotland, including:

*Scottish Gaelic, a Celtic Goidelic language of the Indo-European language family native to Scotland

*Scottish English

*Scottish national identity, the Scottish ide ...

naturalist James Hector

Sir James Hector (16 March 1834 – 6 November 1907) was a Scottish-New Zealand geologist, naturalist, and surgeon who accompanied the Palliser Expedition as a surgeon and geologist. He went on to have a lengthy career as a government employed ...

in 1874. The skeletal material of ''T. oweni'' consisted of a skull

The skull, or cranium, is typically a bony enclosure around the brain of a vertebrate. In some fish, and amphibians, the skull is of cartilage. The skull is at the head end of the vertebrate.

In the human, the skull comprises two prominent ...

, vertebrae

Each vertebra (: vertebrae) is an irregular bone with a complex structure composed of bone and some hyaline cartilage, that make up the vertebral column or spine, of vertebrates. The proportions of the vertebrae differ according to their spinal ...

and paddles

A paddle is a handheld tool with an elongated handle and a flat, widened end (the ''blade'') used as a lever to apply force onto the bladed end. It most commonly describes a completely handheld tool used to propel a human-powered watercraft by p ...

, divided into three distinct sections. In 1888, noting that the fossils are incomplete, Richard Lydekker

Richard Lydekker (; 25 July 1849 – 16 April 1915) was a British naturalist, geologist and writer of numerous books on natural history. He was known for his contributions to zoology, paleontology, and biogeography. He worked extensively in cata ...

uncertainly placed ''T. oweni'' within the genus ''Platecarpus

''Platecarpus'' ("oar wrist") is an extinct genus of aquatic lizards belonging to the mosasaur family, living around 84–81 million years ago during the middle Santonian to early Campanian, of the Late Cretaceous period. Fossils have been found ...

'', being renamed ''Platecarpus oweni''. In 1897, in his revision of the distribution of mosasaur

Mosasaurs (from Latin ''Mosa'' meaning the 'Meuse', and Ancient Greek, Greek ' meaning 'lizard') are an extinct group of large aquatic reptiles within the family Mosasauridae that lived during the Late Cretaceous. Their first fossil remains wer ...

s, Samuel Wendell Williston

Samuel Wendell Williston (July 10, 1852 – August 30, 1918) was an American educator, entomologist, and Paleontology, paleontologist who was the first to propose that birds developed flight Origin of birds#Origin of bird flight, cursorially (by ...

put ''Taniwhasaurus'' back as a separate genus, but considered it to still be close to ''Platecarpus''. As Hector did not designate a holotype fossil for this taxona, Samuel Paul Welles

Samuel Paul Welles (November 9, 1909 – August 6, 1997) was an American palaeontologist. Welles was a research associate at the Museum of Palaeontology, University of California, Berkeley. He took part in excavations at the Placerias Quarry in ...

and D. R. Gregg designate specimen NMNZ R1536, a fragmented skull consisting of frontal and parietal bone

The parietal bones ( ) are two bones in the skull which, when joined at a fibrous joint known as a cranial suture, form the sides and roof of the neurocranium. In humans, each bone is roughly quadrilateral in form, and has two surfaces, four bord ...

accompanied by partial dentary bone

In jawed vertebrates, the mandible (from the Latin ''mandibula'', 'for chewing'), lower jaw, or jawbone is a bone that makes up the lowerand typically more mobilecomponent of the mouth (the upper jaw being known as the maxilla).

The jawbone i ...

, as the lectotype of ''T. oweni'' in 1971. The genus name ''Taniwhasaurus'' is made up of the Māori

Māori or Maori can refer to:

Relating to the Māori people

* Māori people of New Zealand, or members of that group

* Māori language, the language of the Māori people of New Zealand

* Māori culture

* Cook Islanders, the Māori people of the Co ...

word ''Taniwha

In Māori mythology, taniwha () are large supernatural beings that live in deep pools in rivers, dark caves, or in the sea, especially in places with dangerous currents or deceptive breakers (giant waves).

They may be considered highly respecte ...

'', and the Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

word σαῦρος (''saûros'', "lizard"), all literally meaning "lizard of Taniwha", in reference to a supernatural aquatic creature from Māori mythology

Māori mythology and Māori traditions are two major categories into which the remote oral history of New Zealand's Māori people, Māori may be divided. Māori myths concern tales of supernatural events relating to the origins of what was the ...

. The specific epithet

In Taxonomy (biology), taxonomy, binomial nomenclature ("two-term naming system"), also called binary nomenclature, is a formal system of naming species of living things by giving each a name composed of two parts, both of which use Latin gramm ...

''oweni'' is named in honor of the famous English paleontologist Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomy, comparative anatomist and paleontology, palaeontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkabl ...

, who was the first to describe the Mesozoic

The Mesozoic Era is the Era (geology), era of Earth's Geologic time scale, geological history, lasting from about , comprising the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretaceous Period (geology), Periods. It is characterized by the dominance of archosaurian r ...

marine reptiles of New Zealand.

In his article, Hector describes several skeletal remains which he attributes to another mosasaur, which he names '' Leiodon haumuriensis''. In 1897, Williston suggested to transfer this taxon within the genus ''Tylosaurus

''Tylosaurus'' (; "knob lizard") is a genus of Russellosaurina, russellosaurine mosasaur (an extinct group of predatory marine Squamata, lizards) that lived about 92 to 66 million years ago during the Turonian to Maastrichtian stages of the Late ...

'', a proposal that was carried out in 1971, being renamed ''Tylosaurus haumuriensis''. Welles and Gregg also referred to specimen NMNZ R1532 as the lectotype of ''Tylosaurus haumuriensis'' in the article. Although most of these remains have been lost since the 1890s, it's in 1999 that new cranial and postcranial material was discovered in the cliffs of Haumuri Bluff and that these findings were formalized by Michael W. Caldwell and his colleagues in 2005. Based on extensive analyzes of these fossils, researchers found that there are in fact few morphological differences between the two mosasaur taxa from this locality, the differences being mainly due to the larger size of specimen NMNZ R1532, making ''Tylosaurus haumuriensis'' a junior synonym

In taxonomy, the scientific classification of living organisms, a synonym is an alternative scientific name for the accepted scientific name of a taxon. The botanical and zoological codes of nomenclature treat the concept of synonymy differently.

...

of ''T. oweni''.

''T. antarcticus''

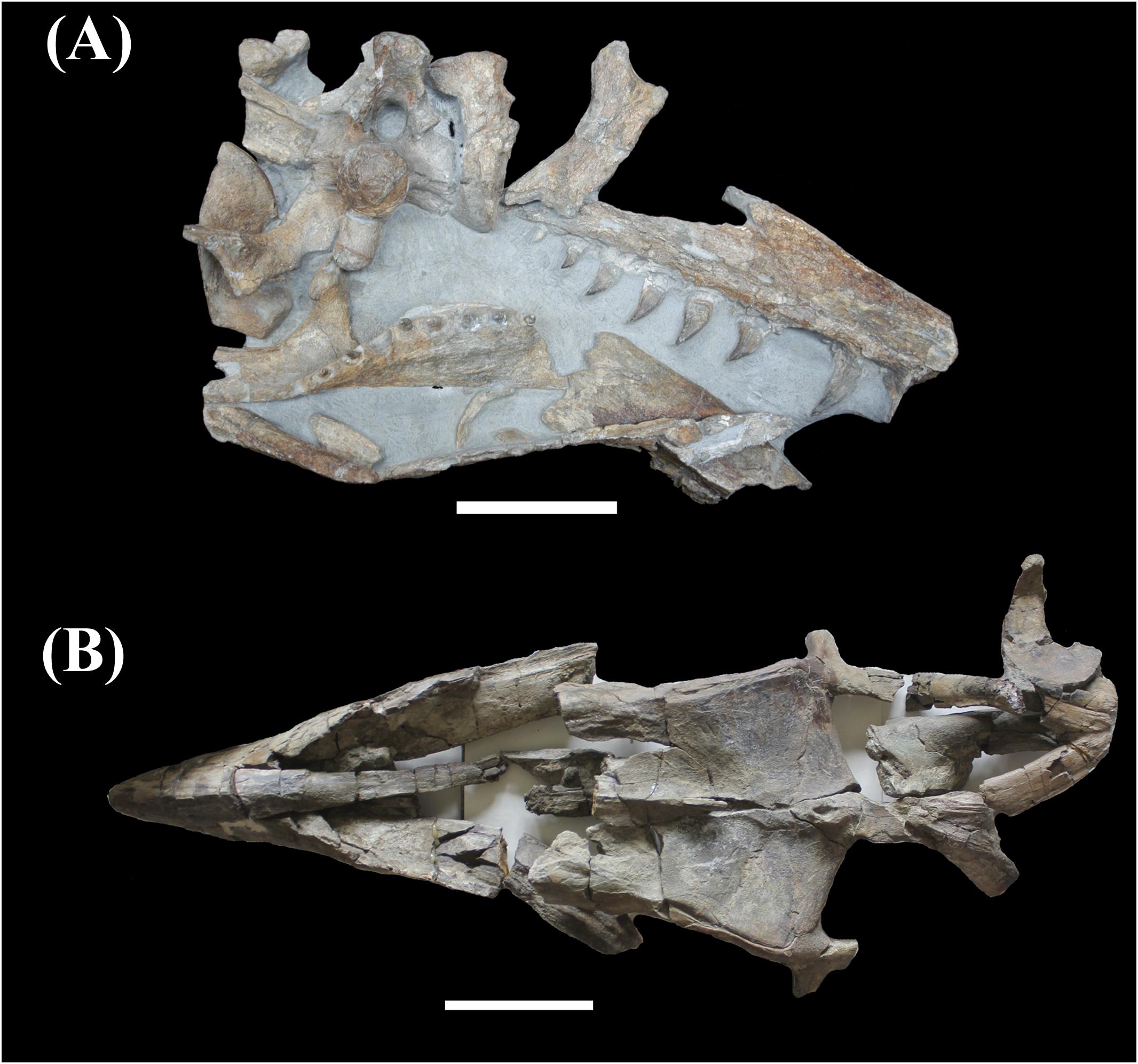

In January 2000, paleontologist Juan M. Lirio discovered a remarkably well-preserved specimen of a mosasaur in the Gamma

In January 2000, paleontologist Juan M. Lirio discovered a remarkably well-preserved specimen of a mosasaur in the Gamma Member

Member may refer to:

* Military jury, referred to as "Members" in military jargon

* Element (mathematics), an object that belongs to a mathematical set

* In object-oriented programming, a member of a class

** Field (computer science), entries in ...

of the Snow Hill Island Formation

The Snow Hill Island Formation is an Maastrichtian, Early Maastrichtian geologic Formation (geology), formation found on James Ross Island, James Ross Island group, Antarctica. Remains of a Paraves, paravian Theropoda, theropod ''Imperobator anta ...

, located on James Ross Island

James Ross Island () is a large island off the southeast side and near the northeastern extremity of the Antarctic Peninsula, from which it is separated by Prince Gustav Channel.

Rising to , it is irregularly shaped and extends in a north–so ...

in Antarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean (also known as the Antarctic Ocean), it contains the geographic South Pole. ...

. This geological member was originally misidentified as belonging to the neighboring Santa Marta Formation. The Gamma Member of the Snow Hill Island Formation is dated in the late Campanian to late Maastrichtian

The Maastrichtian ( ) is, in the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS) geologic timescale, the latest age (geology), age (uppermost stage (stratigraphy), stage) of the Late Cretaceous epoch (geology), Epoch or Upper Cretaceous series (s ...

stages of the Upper Cretaceous. This discovery concerns a tylosaurine

The Tylosaurinae are a subfamily of mosasaurs,Williston, S. W. 1897. Range and distribution of the mosasaurs with remarks on synonymy. ''Kansas University Quarterly'' 4(4):177-185. a diverse group of Late Cretaceous marine Squamata, squamates. Me ...

specimen which heve been discovered in the Upper Campanian fossil record, cataloged IAA 2000-JR-FSM-1, containing a skull measuring long, teeth, some vertebrae and rib

In vertebrate anatomy, ribs () are the long curved bones which form the rib cage, part of the axial skeleton. In most tetrapods, ribs surround the thoracic cavity, enabling the lungs to expand and thus facilitate breathing by expanding the ...

fragments. Unlike the majority of other Antarctic mosasaurs, which are primarily known from teeth and postcranial remains, the skull of this specimen is almost complete and articulated. After analyzing the material, Fernando E. Novas and his colleagues named it ''Lakumasaurus antarcticus''. The genus name ''Lakumasaurus'' comes from the Lakuma, a sea spirit from the mythology of the Yahgan people

The Yahgan (also called Yagán, Yaghan, Yámana, Yamana, or Tequenica) are a group of Indigenous peoples in the Southern Cone of South America. Their traditional territory includes the islands south of Isla Grande de Tierra del Fuego, extending ...

, and from the Ancient Greek term σαῦρος (''saûros'', "lizard"), to literally give "lizard of Lakuma". The specific epithet ''antarcticus'' refers to Antarctica, where the animal lived.

From 2006, James E. Martin questioned the validity of ''Lakumasaurus'' as a separate genus, noting that the cranial features are small enough to justify such a proposal. However, he state that there are enough differences to classify ''Lakumasaurus antarcticus'' as the second species in the genus ''Taniwhasaurus'', being renamed ''T. antarcticus'', a proposal that he would confirm the following year with his colleague Marta Fernández. The same year, Martin and his colleagues announced the discovery of a juvenile skull considered to belong to the same species and dating from the Maastrichtian

The Maastrichtian ( ) is, in the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS) geologic timescale, the latest age (geology), age (uppermost stage (stratigraphy), stage) of the Late Cretaceous epoch (geology), Epoch or Upper Cretaceous series (s ...

, but subsequent studies are skeptical of this claim. Less than two years later, in 2009, the same authors published an article that described in more detail the fossil material and the phylogenetic relationships between the species ''T. antarcticus'' and ''T. oweni'', a relationship that happens to be still recognized today.

Formerly assigned species

''T. capensis''

At the beginning of the 20th century, several fossils began to be collected in the region ofPondoland

Pondoland or Mpondoland (Mpondo: ''EmaMpondweni''), is a natural region on the South African shores of the Indian Ocean. It is located in the coastal belt of the Eastern Cape province. Its territory is the former Mpondo Kingdom of the Mpondo peopl ...

, in South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. Its Provinces of South Africa, nine provinces are bounded to the south by of coastline that stretches along the Atlantic O ...

. These fossils turn out to belong to squamate

Squamata (, Latin ''squamatus'', 'scaly, having scales') is the largest Order (biology), order of reptiles; most members of which are commonly known as Lizard, lizards, with the group also including Snake, snakes. With over 11,991 species, it i ...

s and sea turtle

Sea turtles (superfamily Chelonioidea), sometimes called marine turtles, are reptiles of the order Testudines and of the suborder Cryptodira. The seven existing species of sea turtles are the flatback, green, hawksbill, leatherback, loggerh ...

s dating from the Santonian

The Santonian is an age in the geologic timescale or a chronostratigraphic stage. It is a subdivision of the Late Cretaceous Epoch or Upper Cretaceous Series. It spans the time between 86.3 ± 0.7 mya ( million years ago) and 83.6 ± 0.7 m ...

stage of the Upper Cretaceous. In 1901, one of the sets of fossils discovered (catalogued as SAM-PK-5265), being a few fragmentary pieces of a jawbone

In jawed vertebrates, the mandible (from the Latin ''mandibula'', 'for chewing'), lower jaw, or jawbone is a bone that makes up the lowerand typically more mobilecomponent of the mouth (the upper jaw being known as the maxilla).

The jawbone ...

, was referred as belonging to a reptile considered close to the genus ''Mosasaurus

''Mosasaurus'' (; "lizard of the Meuse (river), Meuse River") is the type genus (defining example) of the mosasaurs, an extinct group of aquatic Squamata, squamate reptiles. It lived from about 82 to 66 million years ago during the Campanian an ...

''. This collection of fossils was later given to the Scottish paleontologist Robert Broom

Robert Broom Fellow of the Royal Society, FRS FRSE (30 November 1866 6 April 1951) was a British- South African medical doctor and palaeontologist. He qualified as a medical practitioner in 1895 and received his DSc in 1905 from the University ...

, who published in 1912 an article describing the same bones, along with a vertebra attributed to this specimen. He concludes that the fossils would belong to a large South African representative of the genus ''Tylosaurus'', naming it ''Tylosaurus capensis''.

Throughout the remainder of the 20th century, ''Tylosaurus capensis'' was generally viewed as a valid species within the genus, being identified primarily by the size of the parietal foramen and the suture between the frontal and

Throughout the remainder of the 20th century, ''Tylosaurus capensis'' was generally viewed as a valid species within the genus, being identified primarily by the size of the parietal foramen and the suture between the frontal and parietal bone

The parietal bones ( ) are two bones in the skull which, when joined at a fibrous joint known as a cranial suture, form the sides and roof of the neurocranium. In humans, each bone is roughly quadrilateral in form, and has two surfaces, four bord ...

s. However, both characteristics are highly variable within the genus ''Tylosaurus'' and are not considered diagnostic at the species level. In 2016, Paulina Jimenez-Huidobro published a thesis

A thesis (: theses), or dissertation (abbreviated diss.), is a document submitted in support of candidature for an academic degree or professional qualification presenting the author's research and findings.International Standard ISO 7144: D ...

which analyzes the deep relationships between the various tylosaurines. Based on observations of the specimen SAM-PK-5265, she proposes moving this species to ''Taniwhasaurus'', claiming that the characteristics found there are closer to this latter than to ''Tylosaurus''. In 2019, Jimenez-Huidobro and Caldwell reaffirm this proposition, but found that the fossils were too poorly preserved to identify definitively to the genus. In 2022, an anatomical review of South African mosasaurs analyzed SAM-PK-5265 and found the specimen to be a chimera

Chimera, Chimaera, or Chimaira (Greek for " she-goat") originally referred to:

* Chimera (mythology), a fire-breathing monster of ancient Lycia said to combine parts from multiple animals

* Mount Chimaera, a fire-spewing region of Lycia or Cilicia ...

of two different mosasaur genera, but not identifiable at the species level: the frontoparietal complex and the posterior dentary fragment without teeth represent cf. ''Prognathodon

''Prognathodon'' is an extinct genus of marine lizard belonging to the mosasaur family. It is classified as part of the Mosasaurinae subfamily, alongside genera like ''Mosasaurus'' and ''Clidastes''. ''Prognathodon'' has been recovered from depos ...

'', while the anterior dentary fragment with replacement teeth represents cf. ''Taniwhasaurus''.

''T. mikasaensis''

In June 1976, a large front part of a mosasaur skull was discovered on abank

A bank is a financial institution that accepts Deposit account, deposits from the public and creates a demand deposit while simultaneously making loans. Lending activities can be directly performed by the bank or indirectly through capital m ...

of the Ikushumbetsu River in Hokkaidō

is the second-largest island of Japan and comprises the largest and northernmost prefecture, making up its own region. The Tsugaru Strait separates Hokkaidō from Honshu; the two islands are connected by railway via the Seikan Tunnel.

The ...

, Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

. This specimen was found in a floating concretion

A concretion is a hard and compact mass formed by the precipitation of mineral cement within the spaces between particles, and is found in sedimentary rock or soil. Concretions are often ovoid or spherical in shape, although irregular shapes a ...

, and its formation of origin was identified with the Kashima Formation, in the Yezo Group

The Yezo Group is a stratigraphic group in Hokkaido, Japan and Sakhalin, Russia which is primarily Late Cretaceous in age (Aptian to Earliest Paleocene). It is exposed as roughly north–south trending belt extending 1,500 kilometres through centr ...

, the locality being the exposed area of this same place. Like the previously mentioned sites, the formation from which the animal was found is dated to the Santonian-Campanian stage. The specimen, cataloged MCM.M0009, was named ''Yezosaurus mikasaensis'' in a press release

A press release (also known as a media release) is an official statement delivered to members of the news media for the purpose of providing new information, creating an official statement, or making an announcement directed for public releas ...

issued by Kikuwo Muramoto and Ikuwo Obata on November 30, 1976, before being erroneously classified as a tyrannosauroid

Tyrannosauroidea (meaning 'tyrant lizard forms') is a superfamily (or clade) of coelurosaurian theropod dinosaurs that includes the family Tyrannosauridae as well as more basal relatives. Tyrannosauroids lived on the Laurasian supercontinen ...

dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic Geological period, period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the #Evolutio ...

in an article published by Muramoto in December of the same year. The genus name ''Yezosaurus'' comes from Yezo, the group containing the Kashima Formation from which the taxon was discovered, and from the Ancient Greek σαῦρος (''saûros'', "lizard"), all literally meaning "Yezo lizard". The specific epithet ''mikasaensis'' is named after the city of Mikasa, a place near the site of discovery. Although these two publications cannot be considered valid from the ICZN

The International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) is a widely accepted convention in zoology that rules the formal scientific naming of organisms treated as animals. It is also informally known as the ICZN Code, for its formal author, t ...

rules, Obata and Muramoto were indeed seen as the authors of the original description of ''Y. mikasaensis''. Also in the same year, and those even before the specimen was named, the Japanese Ministry of Education

The , also known as MEXT, is one of the eleven ministries of Japan that compose part of the executive branch of the government of Japan.

History

The Meiji government created the first Ministry of Education in 1871. In January 2001, the former ...

decided to consider the fossil as the country's national treasure

A national treasure is a structure, artifact, object or cultural work that is officially or popularly recognized as having particular value to the nation, or representing the ideals of the nation. The term has also been applied to individuals or ...

. The specimen would later be known as .

In 2008, the fossil was completely reidentified by Caldwell and colleagues as a mosasaur, and classified as a new species of ''Taniwhasaurus'', being renamed ''T. mikasaensis'', thus keeping the specific epithet of Obata and Muramoto. In the Jimenez-Huidobro thesis published in 2016, three sets of fossils discovered in the original locality were listed and attributed to this proposed species. These consist of additional cranial parts (MCM.A600), two dorsal vertebrae

In vertebrates, thoracic vertebrae compose the middle segment of the vertebral column, between the cervical vertebrae and the lumbar vertebrae. In humans, there are twelve thoracic vertebra (anatomy), vertebrae of intermediate size between the ce ...

(MCM.M10) and caudal vertebrae elements associated with an isolated dorsal vertebra (MCM.A1008). In 2019, the phylogenetic revision of tylosaurines conducted by Jimenez and Calwell still considers the specimen to be a representative of the genus ''Taniwhasaurus'', but the authors argued that the fossils are insufficient for a diagnosis to classify it as a distinct species, so they reclassified it as an indeterminate species of ''Taniwhasaurus''. In 2020, 3D scans were performed on replicas of the specimen, with the real fossil requiring special permission from the Japanese Ministry of Education.

Description

Size

Although fossils of ''Taniwhasaurus'' are incomplete, existing remains suggest the genus was among the shorter of the tylosaurines but nevertheless a medium-sized mosasaur. The largest known specimen is the ''T. oweni'' partial skull NMNZ R1532, which was estimated to have had a complete length of by Welles and Gregg (1971). When extrapolated with the proportions of a mature specimen of the closely related '' Tylosaurus proriger'' (FHSM VP-3), this yields a total length of . ''T. antarcticus'' represents a smaller species; scaling the long holotype skull to the same proportions approximates a total length of .Skull

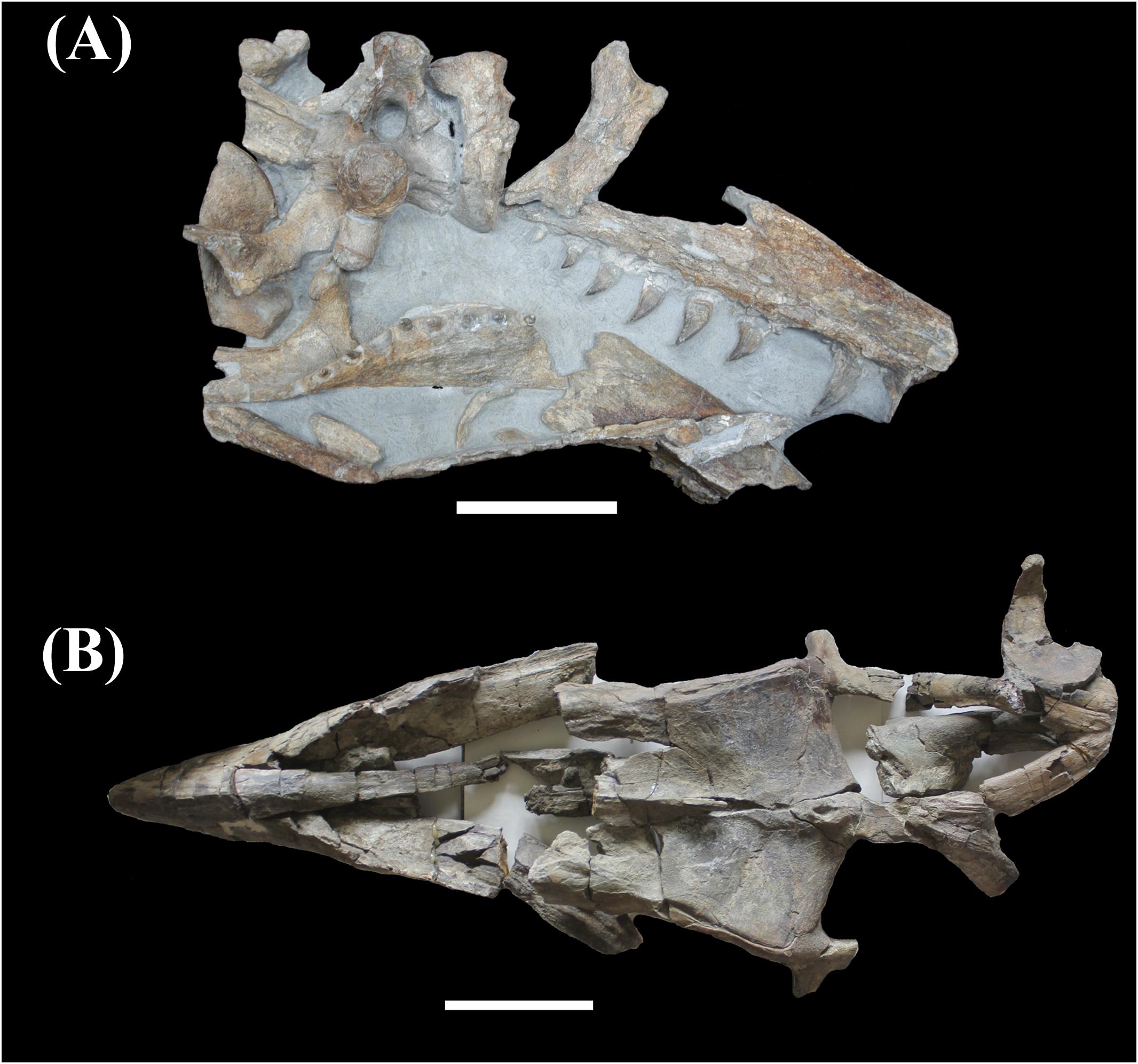

In dorsal view, the skull of ''Taniwhasaurus'' is triangular in shape. Like other tylosaurines, the skull of is characterized by the presence of an edentulous

In dorsal view, the skull of ''Taniwhasaurus'' is triangular in shape. Like other tylosaurines, the skull of is characterized by the presence of an edentulous rostrum

Rostrum may refer to:

* Any kind of a platform for a speaker:

**dais

**pulpit

** podium

* Rostrum (anatomy), a beak, or anatomical structure resembling a beak, as in the mouthparts of many sucking insects

* Rostrum (ship), a form of bow on naval ...

, an anterior process

A process is a series or set of activities that interact to produce a result; it may occur once-only or be recurrent or periodic.

Things called a process include:

Business and management

* Business process, activities that produce a specific s ...

to the dentary bone

In jawed vertebrates, the mandible (from the Latin ''mandibula'', 'for chewing'), lower jaw, or jawbone is a bone that makes up the lowerand typically more mobilecomponent of the mouth (the upper jaw being known as the maxilla).

The jawbone i ...

, and an exclusion of the frontal from the margin of the orbit

In celestial mechanics, an orbit (also known as orbital revolution) is the curved trajectory of an object such as the trajectory of a planet around a star, or of a natural satellite around a planet, or of an artificial satellite around an ...

. The snout

A snout is the protruding portion of an animal's face, consisting of its nose, mouth, and jaw. In many animals, the structure is called a muzzle, Rostrum (anatomy), rostrum, beak or proboscis. The wet furless surface around the nostrils of the n ...

of ''T. oweni'' is rather straight, while in ''T. antarcticus'' it is curved. The external nostrils turn out to be curved backwards. The rostrum of ''Taniwhasaurus'' has a dorsal crest and the frontal bone has a sagittal keel

In the human skull, a sagittal keel, or sagittal torus, is a thickening of part or all of the midline of the frontal bone, or parietal bones where they meet along the sagittal suture, or on both bones. Sagittal keels differ from sagittal crests, ...

. The lateral margins of the frontal are straight. The genus also has a quadrate bone

The quadrate bone is a skull bone in most tetrapods, including amphibians, sauropsids ( reptiles, birds), and early synapsids.

In most tetrapods, the quadrate bone connects to the quadratojugal and squamosal bones in the skull, and forms up ...

with the main diaphysis

The diaphysis (: diaphyses) is the main or midsection (shaft) of a long bone. It is made up of cortical bone and usually contains bone marrow and adipose tissue (fat).

It is a middle tubular part composed of compact bone which surrounds a centr ...

deviated laterally, as well as a pronounced, ventromedially directed process of the suprastapedial. These features essentially lock the posterior movement of the jaws to the maximum posterior rotation of the quadrate. The premaxilla

The premaxilla (or praemaxilla) is one of a pair of small cranial bones at the very tip of the upper jaw of many animals, usually, but not always, bearing teeth. In humans, they are fused with the maxilla. The "premaxilla" of therian mammals h ...

of ''Taniwhasaurus'' bears a longitudinal crest on the anterior half of its dorsal surface, unlike that of ''Tylosaurus'' in which the dorsal surface of the premaxilla is smooth. Like other tylosaurines, this process is extremely well developed, extending the equivalent distance of the two tooth bases of the maxilla

In vertebrates, the maxilla (: maxillae ) is the upper fixed (not fixed in Neopterygii) bone of the jaw formed from the fusion of two maxillary bones. In humans, the upper jaw includes the hard palate in the front of the mouth. The two maxil ...

e. The ascending process of the maxilla is relatively low and rounded, and the articulation with the prefrontal Prefrontal may refer to:

*Prefrontal bone, a skull bone in some tetrapods

*Prefrontal cortex, a region of the brain of a mammal

*Prefrontal scales

The prefrontal scales on snakes and other reptiles are the scales adjacent and anterior to the fr ...

is a long, gently sloping suture. Thus, the maxilla of ''Taniwhasaurus'' is largely excluded from contact with the frontal. The angle described by the descending and horizontal branches of the jugal bone

The jugal is a skull bone found in most reptiles, amphibians and birds. In mammals, the jugal is often called the malar or zygomatic bone, zygomatic. It is connected to the quadratojugal and maxilla, as well as other bones, which may vary by spe ...

is consistent with the angle observed in mosasaurs of the plioplatecarpine

Plioplatecarpinae is a subfamily of mosasaurs, a diverse group of Late Cretaceous marine squamates. Members of the subfamily are informally and collectively known as "plioplatecarpines" and have been recovered from all continents, though the occu ...

group. The mandible of ''Taniwhasaurus'' is characterized for having a slender structure and an unusually high coronoid process.

Teeth

Theteeth

A tooth (: teeth) is a hard, calcified structure found in the jaws (or mouths) of many vertebrates and used to break down food. Some animals, particularly carnivores and omnivores, also use teeth to help with capturing or wounding prey, tear ...

of ''Taniwhasaurus'' have vertical ridges that fade near their tips, and the anterior teeth lack posterior keels. The number of teeth present in ''T. oweni'' and ''T. antarcticus'' vary between the two. The other two species assigned to the genus, ''T. capensis'' and ''T. mikasaensis'', are only known from partial remains, so no conclusions can be drawn regarding their actual number of teeth. In the maxillary teeth, ''T. oweni'' has 14, while ''T. antarcticus'' has 12. At the level of the dentary bones, ''T. oweni'' has 15 teeth, while ''T. antarcticus'' has 13. In both species there are only 2 teeth in the premaxillae. The exact number of teeth in the pterygoid bone

The pterygoid is a paired bone forming part of the palate of many vertebrates, behind the palatine bone

In anatomy, the palatine bones (; derived from the Latin ''palatum'') are two irregular bones of the facial skeleton in many animal specie ...

s are unknown due to lack of complete fossil regarding this part.

Postcranial skeleton

The exact number of vertebrae in ''Taniwhasaurus'' is unknown, but the rare fossils concerning this part of the body include the cervical,

The exact number of vertebrae in ''Taniwhasaurus'' is unknown, but the rare fossils concerning this part of the body include the cervical, dorsal

Dorsal (from Latin ''dorsum'' ‘back’) may refer to:

* Dorsal (anatomy), an anatomical term of location referring to the back or upper side of an organism or parts of an organism

* Dorsal, positioned on top of an aircraft's fuselage

The fus ...

, lumbar

In tetrapod anatomy, lumbar is an adjective that means of or pertaining to the abdominal segment of the torso, between the diaphragm (anatomy), diaphragm and the sacrum.

Naming and location

The lumbar region is sometimes referred to as the lowe ...

and caudal vertebrae

Caudal vertebrae are the vertebrae of the tail in many vertebrates. In birds, the last few caudal vertebrae fuse into the pygostyle, and in apes, including humans, the caudal vertebrae are fused into the coccyx.

In many reptiles, some of the caud ...

. As in other tylosaurines, the articular condyle

A condyle (;Entry "condyle"

in

s of the cervical vertebrae of ''Taniwhasaurus'' are slightly depressed. The neural arch of the in

atlas

An atlas is a collection of maps; it is typically a bundle of world map, maps of Earth or of a continent or region of Earth. Advances in astronomy have also resulted in atlases of the celestial sphere or of other planets.

Atlases have traditio ...

has processes that would have ensured the protection of the spinal cord

The spinal cord is a long, thin, tubular structure made up of nervous tissue that extends from the medulla oblongata in the lower brainstem to the lumbar region of the vertebral column (backbone) of vertebrate animals. The center of the spinal c ...

and the fixation of the muscles that hold the head. The neural spine of the axis

An axis (: axes) may refer to:

Mathematics

*A specific line (often a directed line) that plays an important role in some contexts. In particular:

** Coordinate axis of a coordinate system

*** ''x''-axis, ''y''-axis, ''z''-axis, common names ...

is stout and elongated, culminating posterodorsally in a broad, flattened, incomplete spike that probably bore a cartilaginous cap. The dorsal vertebrae are proceles, and are characterized to have a greater diameter at the anterior level than posterior. The articular surfaces are placed obliquely posterior to the general axis of the spine. The neural arch is continuous with the anterior parts of the centra, and articulated by bold transverse processes. The condyle of the dorsal vertebrae is broad and circular while the robust parapophysis extends laterally for some distance.

The caudal vertebrae have tall, straight neural spines that lack any processes or zygosphene-zygantrum articulation, a joint found in most squamates. The caudal vertebrae have a small, triangular-shaped neural tube

In the developing chordate (including vertebrates), the neural tube is the embryonic precursor to the central nervous system, which is made up of the brain and spinal cord. The neural groove gradually deepens as the neural folds become elevated, ...

. The centrum is shortened on the rostro-caudal side but is elongated dorso-ventrally and compressed laterally, resulting in a ventrally oval rather than circular condyle as seen in presacral vertebrae. The caudal vertebrae of ''Taniwhasaurus'' have craniocaudal centra not fused to the hemal arch, which is a typical case in tylosaurines. Hemal arches articulate with deep hemapophyses but do not fuse with them. Distally, the right and left halves merge midway from the ventral tip of the element, creating a large anterior ridge on the vertebral column.

The rib

In vertebrate anatomy, ribs () are the long curved bones which form the rib cage, part of the axial skeleton. In most tetrapods, ribs surround the thoracic cavity, enabling the lungs to expand and thus facilitate breathing by expanding the ...

s of ''T. oweni'' are flattened and somewhat dilated at their insertion. The rare preserved ribs show convex articular surfaces and they appear to be articulated on a rough surface, placed on the anterior and superior parts of the vertebral centra. Although the shoulder girdle

The shoulder girdle or pectoral girdle is the set of bones in the appendicular skeleton which connects to the arm on each side. In humans, it consists of the clavicle and scapula; in those species with three bones in the shoulder, it consists o ...

is incompletely known in ''Taniwhasaurus'', it appears to be broadly similar in morphology to what is found in tylosaurines in general. The coracoid

A coracoid is a paired bone which is part of the shoulder assembly in all vertebrates except therian mammals (marsupials and placentals). In therian mammals (including humans), a coracoid process is present as part of the scapula, but this is n ...

is much larger than the scapula

The scapula (: scapulae or scapulas), also known as the shoulder blade, is the bone that connects the humerus (upper arm bone) with the clavicle (collar bone). Like their connected bones, the scapulae are paired, with each scapula on either side ...

, and both of these bones are convex in shape. The coracoid plate is thin and distal to the coracoid foramen, but there is no presence of emargination on the medial edge. The humerus

The humerus (; : humeri) is a long bone in the arm that runs from the shoulder to the elbow. It connects the scapula and the two bones of the lower arm, the radius (bone), radius and ulna, and consists of three sections. The humeral upper extrem ...

is very short in relation to its width, being flattened in shape and having a very recurved elbow joint. This same humerus has pronounced muscle ridges. The carp

The term carp (: carp) is a generic common name for numerous species of freshwater fish from the family (biology), family Cyprinidae, a very large clade of ray-finned fish mostly native to Eurasia. While carp are prized game fish, quarries and a ...

are remarkably flat and slender in shape, their edges being raised and rough. The rare fragments of phalanges

The phalanges (: phalanx ) are digit (anatomy), digital bones in the hands and foot, feet of most vertebrates. In primates, the Thumb, thumbs and Hallux, big toes have two phalanges while the other Digit (anatomy), digits have three phalanges. ...

indicate that they would have been cylindrical and elongated. This suggests that ''Taniwhasaurus'' would have had a muscular and powerful humerus that would have been short and wide, with paddle-shaped bones, indicating that it would have been an efficient swimmer.

Classification

''Taniwhasaurus'' was always classified within the mosasaurs, but the initial description published by Hector in 1874 does not attribute it to any subtaxon of this family. Indeed, Hector classifies ''Taniwhasaurus'' in a simplified manner in theorder

Order, ORDER or Orders may refer to:

* A socio-political or established or existing order, e.g. World order, Ancien Regime, Pax Britannica

* Categorization, the process in which ideas and objects are recognized, differentiated, and understood

...

Pythonomorpha

Mosasauria is a clade of Aquatic animal, aquatic and semiaquatic squamates that lived during the Cretaceous period. Fossils belonging to the group have been found in all continents around the world. Early mosasaurians like Dolichosauridae, dolich ...

, a proposed taxon

In biology, a taxon (back-formation from ''taxonomy''; : taxa) is a group of one or more populations of an organism or organisms seen by taxonomists to form a unit. Although neither is required, a taxon is usually known by a particular name and ...

including mosasaur

Mosasaurs (from Latin ''Mosa'' meaning the 'Meuse', and Ancient Greek, Greek ' meaning 'lizard') are an extinct group of large aquatic reptiles within the family Mosasauridae that lived during the Late Cretaceous. Their first fossil remains wer ...

s and snake

Snakes are elongated limbless reptiles of the suborder Serpentes (). Cladistically squamates, snakes are ectothermic, amniote vertebrates covered in overlapping scales much like other members of the group. Many species of snakes have s ...

s ancestors. In 1888, ''Taniwhasaurus'' was moved to the genus ''Platecarpus'' by Lydekker, considering it a junior synonym. In 1897, Williston named the subfamily Platercarpinae and placed ''Taniwhasaurus'' in this group, considering it as a close relative to ''Platecarpus'' and ''Plioplatecarpus''. In 1967, paleontologist Dale Russell

Dale Alan Russell (27 December 1937 – 21 December 2019)

was an American-Canadian geologist and palaeontologist. Throughout his career Russell worked as the Curator of Fossil Vertebrates at the Canadian Museum of Nature, Research Professor at ...

synonymized Platecarpinae with Plioplatecarpinae

Plioplatecarpinae is a subfamily of mosasaurs, a diverse group of Late Cretaceous marine Squamata, squamates. Members of the subfamily are informally and collectively known as "plioplatecarpines" and have been recovered from all continents, thoug ...

due to the principle of priority

Priority is a principle in Taxonomy (biology), biological taxonomy by which a valid scientific name is established based on the oldest available name. It is a decisive rule in Botanical nomenclature, botanical and zoological nomenclature to recogn ...

and their similar taxonomic definitions. Russell, however, classifies ''Taniwhasaurus'' within the subfamily

In biological classification, a subfamily (Latin: ', plural ') is an auxiliary (intermediate) taxonomic rank, next below family but more inclusive than genus. Standard nomenclature rules end botanical subfamily names with "-oideae", and zo ...

Mosasaurinae

The Mosasaurinae are a subfamily of mosasaurs, a diverse group of Late Cretaceous marine Squamata, squamates. Members of the subfamily are informally and collectively known as "mosasaurines" and their fossils have been recovered from every contin ...

, and more precisely in the tribe

The term tribe is used in many different contexts to refer to a category of human social group. The predominant worldwide use of the term in English is in the discipline of anthropology. The definition is contested, in part due to conflict ...

Plotosaurini

Mosasaurini is an extinct tribe of mosasaurine mosasaurs who lived during the Late Cretaceous and whose fossils have been found in North America, South America, Europe, Africa and Oceania, with questionable occurrences in Asia. They are highly d ...

. Russell, considering that the postcranial morphology of ''Taniwhasaurus'' would be similar to that of ''Plotosaurus

''Plotosaurus'' ("swimmer lizard") is an extinct genus of large mosasaurs which lived during the Upper Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) in what is now North America. The taxon was initially described by University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley pale ...

'', provisionally assigns it as its sister taxon

In phylogenetics, a sister group or sister taxon, also called an adelphotaxon, comprises the closest relative(s) of another given unit in an evolutionary tree.

Definition

The expression is most easily illustrated by a cladogram:

Taxon A and ...

.

It was in 1971 that ''Taniwhasaurus'' was moved within the Tylosaurinae

The Tylosaurinae are a subfamily of mosasaurs,Williston, S. W. 1897. Range and distribution of the mosasaurs with remarks on synonymy. ''Kansas University Quarterly'' 4(4):177-185. a diverse group of Late Cretaceous marine squamates. Members of ...

by Welles and Gregg, on the basis of cranial characteristics bringing it closer to the genus ''Tylosaurus''. Later discoveries of other tylosaurines, previously mentioned as belonging to distinct genera and which are now considered synonymous to ''Taniwhasaurus'', will confirm Welles and Gregg's proposal on the phylogenetic position of this genus. The members of this subfamily, including the related genus ''Tylosaurus'' and possibly ''Kaikaifilu'', are characterized by a conical, elongated rostrum

Rostrum may refer to:

* Any kind of a platform for a speaker:

**dais

**pulpit

** podium

* Rostrum (anatomy), a beak, or anatomical structure resembling a beak, as in the mouthparts of many sucking insects

* Rostrum (ship), a form of bow on naval ...

that lacks teeth. In 2019, in their phylogenetic review of this group, Jiménez-Huidobro and Caldwell believe that ''Taniwhasaurus'' cannot be considered with certainty to be monophyletic

In biological cladistics for the classification of organisms, monophyly is the condition of a taxonomic grouping being a clade – that is, a grouping of organisms which meets these criteria:

# the grouping contains its own most recent co ...

, because some named species have too fragmentary fossils to be assigned concretely to the genus. However, they consider that by ignoring the problematic material, ''Taniwhasaurus'' forms a taxon well and truly monophyletic and distinct from ''Tylosaurus''. A study published in 2020 by Daniel Madzia and Andrea Cau suggests a paraphyletic

Paraphyly is a taxonomic term describing a grouping that consists of the grouping's last common ancestor and some but not all of its descendant lineages. The grouping is said to be paraphyletic ''with respect to'' the excluded subgroups. In co ...

relationship of ''Tylosaurus'', considering that ''Taniwhasaurus'' would have evolved from this latter, around 84 million years ago. However, this claim does not appear to be consistent with previous phylogenetic analysis conducted on the two genera.

The following cladogram is modified from the phylogenetic analysis conducted by Jiménez-Huidobro & Caldwell (2019), based on tylosaurine species with materials known enough to model precise relationships:

Paleobiology

Rostral neurovascular system

A study published in 2020 based on

A study published in 2020 based on CT scan

A computed tomography scan (CT scan), formerly called computed axial tomography scan (CAT scan), is a medical imaging technique used to obtain detailed internal images of the body. The personnel that perform CT scans are called radiographers or ...

s of the rostrum of the holotype of ''T. antarcticus'' reveals the presence of several internal foramina

In anatomy and osteology, a foramen (; : foramina, or foramens ; ) is an opening or enclosed gap within the dense connective tissue (bones and deep fasciae) of extant and extinct amniote animals, typically to allow passage of nerves, arter ...

located in the most forward part of the snout

A snout is the protruding portion of an animal's face, consisting of its nose, mouth, and jaw. In many animals, the structure is called a muzzle, Rostrum (anatomy), rostrum, beak or proboscis. The wet furless surface around the nostrils of the n ...

. These foramina, the ''ramus maxillaris'' and ''ramus ophthalmicus'' are abundantly branched and have the particularity of being directly connected to the trigeminal nerve

In neuroanatomy, the trigeminal nerve (literal translation, lit. ''triplet'' nerve), also known as the fifth cranial nerve, cranial nerve V, or simply CN V, is a cranial nerve responsible for Sense, sensation in the face and motor functions ...

, indicating that they would have sent sensitive information from the skin

Skin is the layer of usually soft, flexible outer tissue covering the body of a vertebrate animal, with three main functions: protection, regulation, and sensation.

Other animal coverings, such as the arthropod exoskeleton, have different ...

of the snout to the brain

The brain is an organ (biology), organ that serves as the center of the nervous system in all vertebrate and most invertebrate animals. It consists of nervous tissue and is typically located in the head (cephalization), usually near organs for ...

. This means that ''Taniwhasaurus'' would have had an electro-sensitive organ capable of detecting the slightest movement of prey underwater. This neurovascular system is comparable to those present in various living and extinct aquatic tetrapod

A tetrapod (; from Ancient Greek :wiktionary:τετρα-#Ancient Greek, τετρα- ''(tetra-)'' 'four' and :wiktionary:πούς#Ancient Greek, πούς ''(poús)'' 'foot') is any four-Limb (anatomy), limbed vertebrate animal of the clade Tetr ...

s, such as cetacean

Cetacea (; , ) is an infraorder of aquatic mammals belonging to the order Artiodactyla that includes whales, dolphins and porpoises. Key characteristics are their fully aquatic lifestyle, streamlined body shape, often large size and exclusively c ...

s, crocodilian

Crocodilia () is an Order (biology), order of semiaquatic, predatory reptiles that are known as crocodilians. They first appeared during the Late Cretaceous and are the closest living relatives of birds. Crocodilians are a type of crocodylomorp ...

s, plesiosaur

The Plesiosauria or plesiosaurs are an Order (biology), order or clade of extinct Mesozoic marine reptiles, belonging to the Sauropterygia.

Plesiosaurs first appeared in the latest Triassic Period (geology), Period, possibly in the Rhaetian st ...

s and ichthyosaur

Ichthyosauria is an order of large extinct marine reptiles sometimes referred to as "ichthyosaurs", although the term is also used for wider clades in which the order resides.

Ichthyosaurians thrived during much of the Mesozoic era; based on fo ...

s, which are used to stalk prey in low light conditions.

The study mentions that ''T. antarcticus'' is the first mosasaur identified to have such structures that could explain this, but it is likely that this type of organ is present in related genera. Several mosasaurs have large foramina similar to those present in ''Taniwhasaurus'', which seems to indicate a widespread condition within the group. Additionally, tylosaurines appear to display the largest foramen at the snout among mosasaurs. This condition can be correlated with the toothless snout that characterizes the morphology of this subfamily, but further studies are needed to validate these two hypotheses.

Muscularity

Neck mechanics

The prezygapophyses of ''T. antarcticus'' are not as developed, which indicated that this musculature would be less pronounced than in other mosasaurs. The prezygapophyses of the cervical vertebrae mark the location of thelongissimus

The longissimus () is the muscle lateral to the semispinalis muscles. It is the longest subdivision of the erector spinae muscles that extends forward into the transverse processes of the posterior cervical vertebrae.

Structure

Longissimus th ...

and semispinalis muscles

The semispinalis muscles are a group of three muscles belonging to the transversospinales. These are the semispinalis capitis, the semispinalis cervicis and the semispinalis thoracis.

Location

The semispinalis capitis (''complexus'') is situate ...

, which partly produce the lateral flexions of the body in reptiles. The little development of crests in the cervical indicates that the gripping surface of the named muscles would consequently be smaller than in other mosasaurs, as well as the force produced by these muscles. ''T. antarcticus'' would therefore have had great capacity for lateral movement of the neck

The neck is the part of the body in many vertebrates that connects the head to the torso. It supports the weight of the head and protects the nerves that transmit sensory and motor information between the brain and the rest of the body. Addition ...

, although the muscles anchored there would not have had great strength. Along the same lines, the reduced prezygapophyses indicated that the cervical vertebrae had a looser connection to each other, as they exhibited a reduction in the area of articulation between them. The related genus ''Tylosaurus'' would not have had overly pronounced neck mobility due to backward-curving neural spines, which more closely attaches one vertebra to another by means of ligaments and axial musculature. Although vertebrae were not found with complete neural spines in ''Taniwhasaurus'', centra compression values indicate that although it may have had some restriction to lateral movement, it would have been more pronounced anyway.

Mobility

Although the dorsal and caudal vertebrae of ''T. antarcticus'' are poorly preserved, they follow a very similar morphology to that of ''Tylosaurus'' and ''

Although the dorsal and caudal vertebrae of ''T. antarcticus'' are poorly preserved, they follow a very similar morphology to that of ''Tylosaurus'' and ''Plotosaurus

''Plotosaurus'' ("swimmer lizard") is an extinct genus of large mosasaurs which lived during the Upper Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) in what is now North America. The taxon was initially described by University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley pale ...

''. The pygal vertebrae, which are derived caudal vertebrae, are interpreted as a bearing area that would have great flexibility. This part of the caudal vertebrae consists of a very similar in morphology to each other, and is represented in ''Taniwhasaurus'' only by intermediate caudal vertebrae.

The terminal caudal vertebrae would support the caudal fin and, as in ''Plotosaurus'', these have a subcircular section in the anterior region and turn into an ovoid shape compressed laterally posteriorly. However, this configuration does not allow one to assess whether or not there is a tendency for high numbers of pygal vertebrae at the expense of intermediate caudals, as seen in derived mosasaurines. It was suggested that Rusellosaurina, the clade including tylosaurines and related lineages, had a plesiomorphic axial skeleton

The axial skeleton is the core part of the endoskeleton made of the bones of the head and trunk of vertebrates. In the human skeleton, it consists of 80 bones and is composed of the skull (28 bones, including the cranium, mandible and the midd ...

and that therefore their swimming would be less developed, quite the opposite of mosasaurines, which would have had carangiform swimming, that is to say forms where the tail is the main source of propulsion, while the most anterior part of the body maintains restricted movement. However, a thesis published in 2017 proves that ''Tylosaurus'' had a powerful and fast swim, due in particular to the regionalization of the caudal vertebrae, although less marked than in more derived mosasaurines.

The analyzes concerning the dorsal and caudal vertebrae in ''Plotosaurus'' and ''Tylosaurus'' are similar to those found in modern cetaceans, and that therefore these would also have a carangiform swimming shape. The relative measurements of the vertebral centra, of the morphological and phylogenetic proximity with ''Tylosaurus'', seem to indicate that the tail

The tail is the elongated section at the rear end of a bilaterian animal's body; in general, the term refers to a distinct, flexible appendage extending backwards from the midline of the torso. In vertebrate animals that evolution, evolved to los ...

of ''T. antarcticus'' would also have a very important role in movement, confirming this hypothesis. However, the cervical vertebrae of ''Taniwhasaurus'' show an unusual range of motion in a carangiform swimmer, perhaps wider than in any other mosasaur due to the lateral compression of the vertebral centra in this area, but also at their length. Based on this evidence, it is accepted that although the entire vertebral column of ''T. antarcticus'' would have had great mobility, the tail would be the main source of propulsion, supporting the trend towards more carangiform forms, placing ''Taniwhasaurus'' somewhere between the forms eel-shaped basals and carangiform-derived forms. This is in agreement with the phylogenetic position of this taxon.

Paleoecology

Excluding the species ''T. mikasaensis'', the presence of ''T. oweni'' and ''T. antarcticus'' shows that the genus would have been endemic toGondwana

Gondwana ( ; ) was a large landmass, sometimes referred to as a supercontinent. The remnants of Gondwana make up around two-thirds of today's continental area, including South America, Africa, Antarctica, Australia (continent), Australia, Zea ...

, and more specifically in the Cretaceous Austral Fauna of the Weddellian Province, a geographic area including Antarctica, New Zealand and Patagonia

Patagonia () is a geographical region that includes parts of Argentina and Chile at the southern end of South America. The region includes the southern section of the Andes mountain chain with lakes, fjords, temperate rainforests, and glaciers ...

. It is notably the first mosasaur genus known to be endemic to this area. The chimeric ''T. capensis'' also partially supports that the genus is endemic to Gondwana, with the anterior dentary fragment representing cf. ''Taniwhasaurus''. However, the indeterminate tooth crown specimens identified as ''Taniwhasaurus'' sp. from the Santonian-aged strata of the Southern Ural

Southern Ural (, ) encompasses the south, the widest part of the Ural Mountains, stretches from the river Ufa (near the village of Lower Ufaley) to the Ural River. From the west and east the Southern Ural is limited to the East European Plain, W ...

s in European Russia challenge the proposed Gondwanan endemism of this genus.

New Zealand

''T. oweni'' is known from the Conway Formation, and more specifically from Haumuri Bluff, a locality containing Lower and Middle Campanian fossils. The specific part of the site reaches a maximum thickness of andlithologically

The lithology of a rock unit is a description of its physical characteristics visible at outcrop, in hand or core samples, or with low magnification microscopy. Physical characteristics include colour, texture, grain size, and composition. Lith ...

the unit is a loosely cement

A cement is a binder, a chemical substance used for construction that sets, hardens, and adheres to other materials to bind them together. Cement is seldom used on its own, but rather to bind sand and gravel ( aggregate) together. Cement mi ...

ed massive gray siltstone

Siltstone, also known as aleurolite, is a clastic sedimentary rock that is composed mostly of silt. It is a form of mudrock with a low clay mineral content, which can be distinguished from shale by its lack of fissility.

Although its permeabil ...

with locally limited interbeds of fine sandstone

Sandstone is a Clastic rock#Sedimentary clastic rocks, clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of grain size, sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) silicate mineral, silicate grains, Cementation (geology), cemented together by another mineral. Sand ...

. The cores of the concretion

A concretion is a hard and compact mass formed by the precipitation of mineral cement within the spaces between particles, and is found in sedimentary rock or soil. Concretions are often ovoid or spherical in shape, although irregular shapes a ...

s present in the formation appear to be fossilized bones, shell

Shell may refer to:

Architecture and design

* Shell (structure), a thin structure

** Concrete shell, a thin shell of concrete, usually with no interior columns or exterior buttresses

Science Biology

* Seashell, a hard outer layer of a marine ani ...

s or even wood

Wood is a structural tissue/material found as xylem in the stems and roots of trees and other woody plants. It is an organic materiala natural composite of cellulosic fibers that are strong in tension and embedded in a matrix of lignin t ...

, indicating that the environment of deposit would have been the lower zone of a foreshore

The intertidal zone or foreshore is the area above water level at low tide and underwater at high tide; in other words, it is the part of the littoral zone within the tidal range. This area can include several types of Marine habitat, habitats ...

. Mollusc

Mollusca is a phylum of protostome, protostomic invertebrate animals, whose members are known as molluscs or mollusks (). Around 76,000 extant taxon, extant species of molluscs are recognized, making it the second-largest animal phylum ...

s known from this area include the ammonite

Ammonoids are extinct, (typically) coiled-shelled cephalopods comprising the subclass Ammonoidea. They are more closely related to living octopuses, squid, and cuttlefish (which comprise the clade Coleoidea) than they are to nautiluses (family N ...

'' Kossmaticeras'' and the bivalve

Bivalvia () or bivalves, in previous centuries referred to as the Lamellibranchiata and Pelecypoda, is a class (biology), class of aquatic animal, aquatic molluscs (marine and freshwater) that have laterally compressed soft bodies enclosed b ...

''Inoceramus

''Inoceramus'' (Greek: translation "fibrous shell" for the fibrous structure of the mineral crystals in the shell) is an extinct genus of fossil marine pteriomorphian bivalves that superficially resembled the related winged pearly oysters of th ...

''. Many dinoflagellate

The Dinoflagellates (), also called Dinophytes, are a monophyletic group of single-celled eukaryotes constituting the phylum Dinoflagellata and are usually considered protists. Dinoflagellates are mostly marine plankton, but they are also commo ...

s are also known. Relatively few large fish

A fish (: fish or fishes) is an aquatic animal, aquatic, Anamniotes, anamniotic, gill-bearing vertebrate animal with swimming fish fin, fins and craniate, a hard skull, but lacking limb (anatomy), limbs with digit (anatomy), digits. Fish can ...

es are known within the site from sources, the only clearly identified being the great rajiform ray

Ray or RAY may refer to:

Fish

* Ray (fish), any cartilaginous fish of the superorder Batoidea

* Ray (fish fin anatomy), the bony or horny spine on ray-finned fish

Science and mathematics

* Half-line (geometry) or ray, half of a line split at an ...

''Australopristis

''Australopristis'' is an extinct genus of sclerorhynchoid fish from the late Cretaceous epoch. Its name is derived from the Latin for "southern" and the Greek for "saw". It is known from a single species, ''A. wiffeni'' named for the late promi ...

''. Other mosasaurs identified include ''Mosasaurus mokoroa''. Among the plesiosaurs, no precise genus has been determined with the exception of the elasmosaurid

Elasmosauridae, often called elasmosaurs or elasmosaurids, is an extinct family of plesiosaurs that lived from the Hauterivian stage of the Early Cretaceous to the Maastrichtian stage of the Late Cretaceous period (c. 130 to 66 mya). The taxo ...

''Mauisaurus

''Mauisaurus'' ("Māui lizard") is a dubious genus of plesiosaur that lived during the Late Cretaceous period in what is now New Zealand. Numerous specimens have been attributed to this genus in the past, but a 2017 paper restricts ''Mauisaurus' ...

'', which itself has been recognized as dubious since 2017. However, the fossils identified within the site come from plesiosaurids, elasmosaurids and polycotylids

Polycotylidae is a family of plesiosaurs from the Cretaceous, a sister group to Leptocleididae. They are known as false pliosaurs. Polycotylids first appeared during the Albian stage of the Early Cretaceous, before becoming abundant and widesprea ...

.

Antarctic

''T. antarcticus'' is known from Late Campanian deposits of the

''T. antarcticus'' is known from Late Campanian deposits of the Antarctic Peninsula

The Antarctic Peninsula, known as O'Higgins Land in Chile and Tierra de San Martin in Argentina, and originally as Graham Land in the United Kingdom and the Palmer Peninsula in the United States, is the northernmost part of mainland Antarctica.

...