Kyiv Opera House on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Kyiv Opera House, officially the National Academic Opera and Ballet Theatre of Ukraine named after Taras Shevchenko (), is an

The first theatre to stage operas in Kyiv was built in 1804–1806 on Horse Square (), later known as , now European Square. Designed by

The first theatre to stage operas in Kyiv was built in 1804–1806 on Horse Square (), later known as , now European Square. Designed by

On the day of the opening, prayer were said by the clergy, the opera house was sprinkled with

On the day of the opening, prayer were said by the clergy, the opera house was sprinkled with

Drone footage of the National Opera of Ukraine

from ZBROY Films {{coord, 50, 26, 48, N, 30, 30, 45, E, type:landmark, display=title Opera houses in Ukraine Theatres in Kyiv Art Nouveau theatres Art Nouveau architecture in Kyiv Volodymyrska Street Theatres completed in 1803 Theatres completed in 1856 Theatres completed in 1901

opera house

An opera house is a theater building used for performances of opera. Like many theaters, it usually includes a stage, an orchestra pit, audience seating, backstage facilities for costumes and building sets, as well as offices for the institut ...

in Kyiv

Kyiv, also Kiev, is the capital and most populous List of cities in Ukraine, city of Ukraine. Located in the north-central part of the country, it straddles both sides of the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2022, its population was 2, ...

, Ukraine. It is the home of the National Opera of Ukraine

The Kyiv Opera group in Ukraine was formally established in the summer of 1867, and is the third oldest opera in Ukraine, after Odesa Opera and Lviv Opera.

The Kyiv Opera Company perform Kyiv Opera House, named after Taras Shevchenko.

Hist ...

.

The building is located at the junction between Volodymyrska Street

Volodymyrska Street () is a street in the center of Kyiv, the capital of Ukraine, which is named after the prince of Kievan Rus' Vladimir the Great. It is one of the oldest streets in the city, and arguably among the oldest constantly inhabited r ...

and . Designed by the Russian architect Victor Schröter

Victor Alexandrovich Schröter (; 1839–1901) was a Russian architect of German ethnicity.

Career

Schröter was born 27 April 1839, in St. Petersburg of Baltic Germans, Baltic German ancestry. His father was Alexander Gottlieb Schröter.

From ...

with an exterior in the Renaissance Revival

Renaissance Revival architecture (sometimes referred to as "Neo-Renaissance") is a group of 19th-century architectural revival styles which were neither Greek Revival nor Gothic Revival but which instead drew inspiration from a wide range of ...

style, it was opened in 1901, replacing an earlier structure, the , that had been established in 1856, but destroyed by fire in 1896.

On 1 September 1911, the Russian Prime Minister Pyotr Stolypin

Pyotr Arkadyevich Stolypin ( rus, Пётр Аркадьевич Столыпин, p=pʲɵtr ɐrˈkadʲjɪvʲɪtɕ stɐˈlɨpʲɪn; – ) was a Russian statesman who served as the third Prime Minister of Russia, prime minister and the Ministry ...

was mortally wounded in the opera house after an assailant shot him during a visit to the opera, and it was where the First Universal of the Ukrainian Central Council

The First Universals (Central Rada), Universal of the Ukrainian Central Rada (Council) () is a state-political act, the universal of the Central Rada, Central Rada (Council) of Ukraine, which proclaimed the autonomy of Ukraine. Accepted in Kyiv. T ...

on Ukraine's autonomy was proclaimed in June 1917.

Previous establishments

Kyiv's first opera theatre

The first theatre to stage operas in Kyiv was built in 1804–1806 on Horse Square (), later known as , now European Square. Designed by

The first theatre to stage operas in Kyiv was built in 1804–1806 on Horse Square (), later known as , now European Square. Designed by Andrey Melensky

Andrey Ivanovich Melensky (; 1766–1833) was a Russian Imperial Neoclassical architect from MoscowМ. М. Жербин. Украинские и зарубежные строители: краткий биографический справочн� ...

, it was a wooden two-storey building, designed in the Empire style

The Empire style (, ''style Empire'') is an early-nineteenth-century design movement in architecture, furniture, other decorative arts, and the visual arts, representing the second phase of Neoclassicism. It flourished between 1800 and 1815 duri ...

, and constructed from wood from demolished buildings originating from the Pecherskyi district of the city. The theatre entrance was decorated with a portico

A portico is a porch leading to the entrance of a building, or extended as a colonnade, with a roof structure over a walkway, supported by columns or enclosed by walls. This idea was widely used in ancient Greece and has influenced many cu ...

. The theatre had 32 boxes, a gallery, and a parterre

A ''parterre'' is a part of a formal garden constructed on a level substrate, consisting of symmetrical patterns, made up by plant beds, plats, low hedges or coloured gravels, which are separated and connected by paths. Typically it was the ...

that contained space 40 seats and a standing area. It apparently had good acoustics. It quickly became the cultural life of Kyiv.

In the middle of the 19th century, it was decided to demolish the old theatre building on , as it had become outdated. The final performance occurred on 30 July 1851. Prisoners were brought in to demolish the building. For five years, Kyiv

Kyiv, also Kiev, is the capital and most populous List of cities in Ukraine, city of Ukraine. Located in the north-central part of the country, it straddles both sides of the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2022, its population was 2, ...

had no permanent theatre. A group of artists founded a small theatre company and rented private premises on Khreshchatyk

Khreshchatyk (, ) is the main street of Kyiv, the capital city of Ukraine. The street is long, and runs in a northeast-southwest direction from European Square (Kyiv), European Square through the Maidan Nezalezhnosti, Maidan to Bessarabska Sq ...

, and later in a house in Lypky

Lypky () is an historic neighborhood of the Ukrainian capital Kyiv located in the administrative Pecherskyi District. The name is derived from a lime tree (Lypa). Lypky is the ''de facto'' government quarter of Ukraine hosting the buildings of th ...

.

Second City Theatre

The old theatre was eventually replaced by the , which was designed by the Russian architect . The City Theatre opened in 1856, and was until 1863 leased to Russian, Ukrainian, or Polish theatrical companies, before being used by an Italian opera company. The opera house was located at the junction betweenVolodymyrska Street

Volodymyrska Street () is a street in the center of Kyiv, the capital of Ukraine, which is named after the prince of Kievan Rus' Vladimir the Great. It is one of the oldest streets in the city, and arguably among the oldest constantly inhabited r ...

and .

The Russian Opera Theatre, the city's first permanent opera company, was formed in the summer of 1867, under the directorship of the singer and entrepreneur The company's first opera was Alexey Verstovsky

Alexey Nikolayevich Verstovsky () () was a Russian composer, musical bureaucrat and rival of Mikhail Glinka.

Biography

Alexey Verstovsky was born at Seliverstovo Estate, Kozlovsky Uyezd, Tambov Governorate. The grandson of General A. Selivers ...

’s ''Askold's Grave

Askold's Grave () is a historical park on the steep right bank of the Dnipro River in Kyiv between Mariinskyi Park and the Kyiv Pechersk Lavra complex. The park was created by the Soviets in the mid-1930s in place of an old graveyard around t ...

'', which was first performed on 6 November 1867 The opera company's most notable director was , who managed the theatre from 18741883, and again from 18921893). At first, only works by Russian composers, or occasionally operas from the Western European repertoire, were staged. In 1874, the opera house was the venue for the premiere of the first opera written in Ukrainian, Mykola Lysenko

Mykola Vitaliiovych Lysenko (; 22 March 1842 – 6 November 1912) was a Ukrainian composer, pianist, conductor and ethnomusicologist of the late Romantic period. In his time he was the central figure of Ukrainian music, with an ''oeuvre'' tha ...

's '. Other operas staged during this period were Mikhail Glinka

Mikhail Ivanovich Glinka ( rus, links=no, Михаил Иванович Глинка, Mikhail Ivanovich Glinka, mʲɪxɐˈil ɨˈvanəvʲɪdʑ ˈɡlʲinkə, Ru-Mikhail-Ivanovich-Glinka.ogg; ) was the first Russian composer to gain wide recognit ...

's operas ''A Life for the Tsar

''A Life for the Tsar'' ( ) is a "patriotic-heroic tragic" opera in four acts with an epilogue by Mikhail Glinka. During the Soviet era the opera was known under the name '' Ivan Susanin'' ( ), due to the anti-monarchist censorship.

The original ...

'', ''Ruslan and Ludmila

''Ruslan and Ludmila'' ( pre-reform Russian: ; post-reform ) is a poem by Alexander Pushkin, published in 1820. Written as an epic literary fairy tale consisting of a dedication (посвящение), six "cantos" ( песни), and an epilogue ( ...

'', by Alexander Dargomyzhsky

Alexander Sergeyevich Dargomyzhsky ( rus, links=no, Александр Сергеевич Даргомыжский, Aleksandr Sergeyevich Dargomyzhskiy, ɐlʲɪkˈsandr sʲɪrˈɡʲe(j)ɪvʲɪdʑ dərɡɐˈmɨʂskʲɪj, Ru-Aleksandr-Sergeevich- ...

, and ''Die Maccabäer

''Die Maccabäer'' (''German language, German, The Maccabees'') (sometimes spelt 'Die Makkabäer') is an opera in three acts by Anton Rubinstein to a libretto by Salomon Hermann Mosenthal. The opera is based on a play by Otto Ludwig (writer), Otto ...

'' by Anton Rubinstein

Anton Grigoryevich Rubinstein (; ) was a Russian pianist, composer and conductor who founded the Saint Petersburg Conservatory. He was the elder brother of Nikolai Rubinstein, who founded the Moscow Conservatory.

As a pianist, Rubinstein ran ...

. The Kyiv premieres of ''Aleko

The Moskvitch-2141, also known under the trade name Aleko (Russian: "АЛЕКО", derivative from the name of the automaker "Автомобильный завод имени Ленинского Комсомола", ''Avtomobilnyj zavod imeni Len ...

'' by Sergei Rachmaninoff

Sergei Vasilyevich Rachmaninoff; in Russian pre-revolutionary script. (28 March 1943) was a Russian composer, virtuoso pianist, and Conducting, conductor. Rachmaninoff is widely considered one of the finest pianists of his day and, as a compos ...

(1893) and ''The Snow Maiden

''The Snow Maiden: A Spring Fairy Tale'' ( rus, Снегурочка–весенняя сказка, Snegurochka–vesennyaya skazka, a=Ru-Snegurochka.ogg) is an opera in four acts with a prologue by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, composed d ...

'' by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov

Nikolai Andreyevich Rimsky-Korsakov. At the time, his name was spelled , which he romanized as Nicolas Rimsky-Korsakow; the BGN/PCGN transliteration of Russian is used for his name here; ALA-LC system: , ISO 9 system: .. (18 March 1844 – 2 ...

(1895) were performed at the opera house, under the direction of the composers.

In February 1896, following a performance of Tchaikovsky

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky ( ; 7 May 1840 – 6 November 1893) was a Russian composer during the Romantic period. He was the first Russian composer whose music made a lasting impression internationally. Tchaikovsky wrote some of the most popular ...

's opera ''Eugene Onegin

''Eugene Onegin, A Novel in Verse'' (, Reforms of Russian orthography, pre-reform Russian: Евгеній Онѣгинъ, романъ въ стихахъ, ) is a novel in verse written by Alexander Pushkin. ''Onegin'' is considered a classic of ...

'', a fire started in one of the City Theatre dressing rooms. The fire destroyed the building, along with one of the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

’s largest music libraries and collections of costume and stage prop

A prop, formally known as a (theatrical) property, is an object actors use on stage or screen during a performance or screen production. In practical terms, a prop is considered to be anything movable or portable on a stage or a set, distinct ...

s. Performances were then moved to the Bergogne Theatre, the Solovtsov Theatre, and at the Krutikov Circus.

Current opera house

Commission and construction

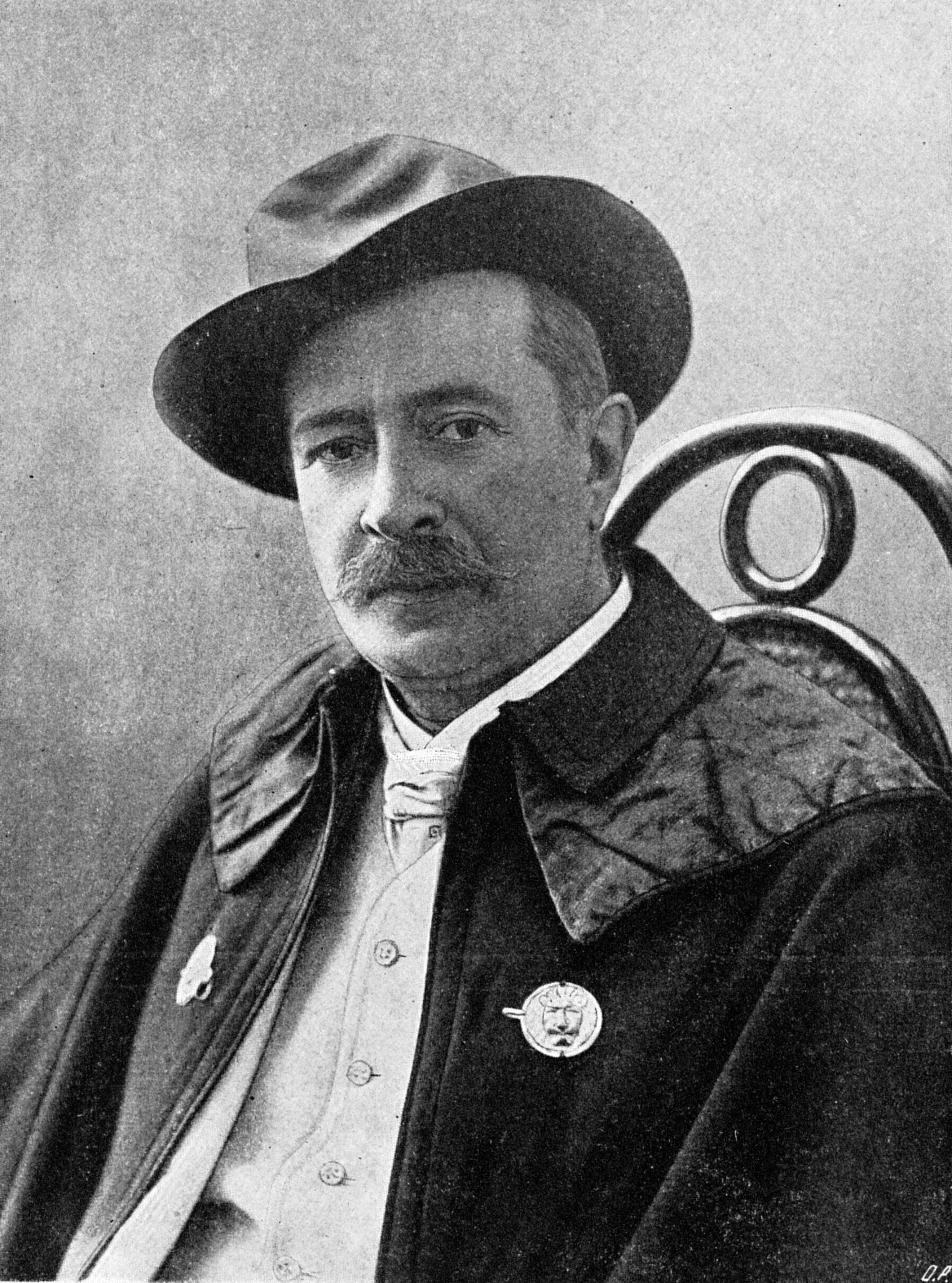

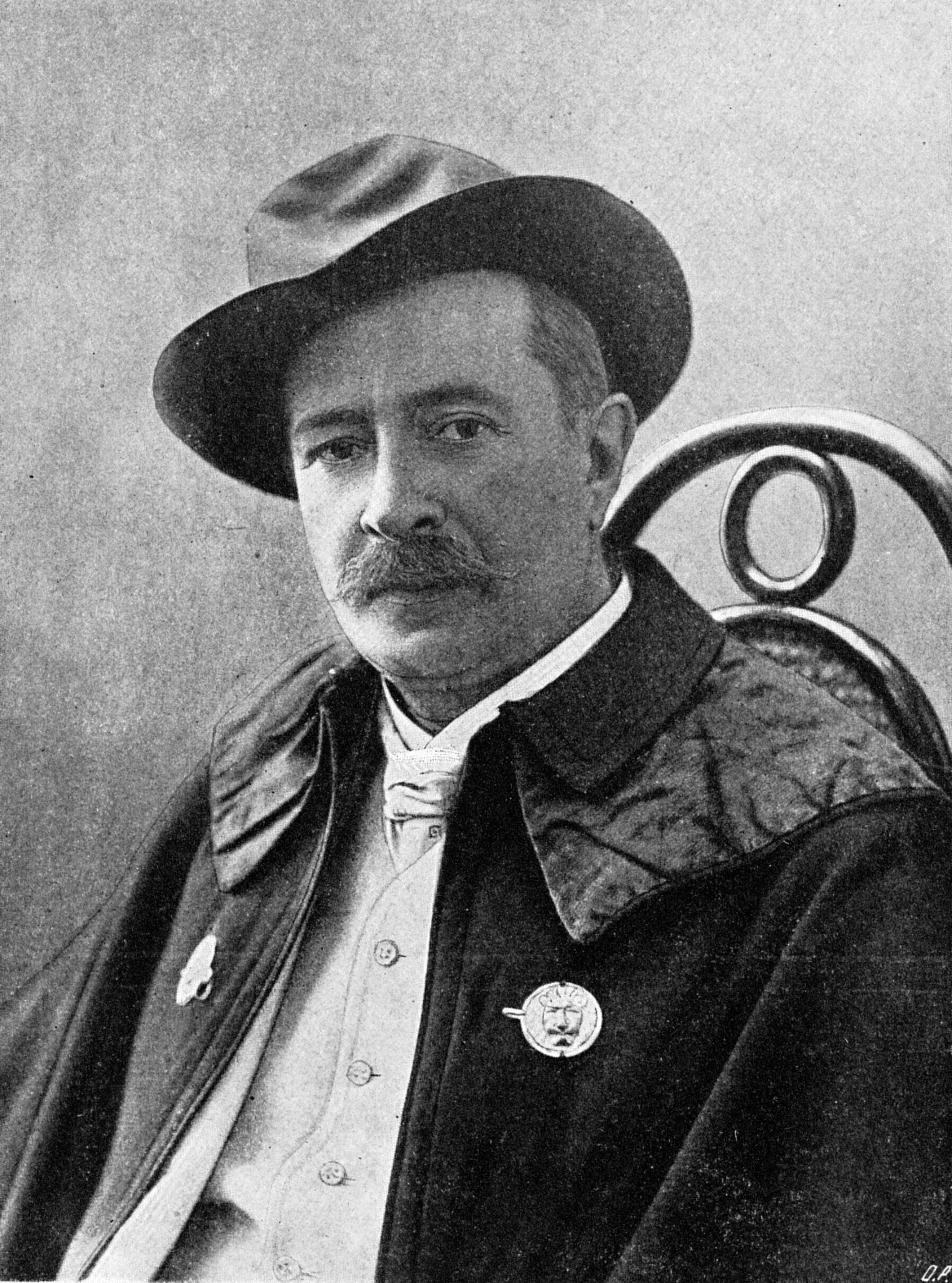

After the fire, the announced an international competition to design a new opera house, built in stone. Entries were received from about 30 architects from Ukraine, Russia, Germany, France, and Italy. The winning design, announced in February 1897, was by the Russian architectVictor Schröter

Victor Alexandrovich Schröter (; 1839–1901) was a Russian architect of German ethnicity.

Career

Schröter was born 27 April 1839, in St. Petersburg of Baltic Germans, Baltic German ancestry. His father was Alexander Gottlieb Schröter.

From ...

, then the chief architect of the Directorate of Imperial Theatres. The project received the approval of the on 24 May 1897.

Schröter produced over 250 design drawings for the new opera house. Construction began in August 1898, initially under the supervision of the city architect, . In 1899, Kryvosheev was replaced by the Ukrainian architect and his assistant . Up to 500 workers and 60 horses were engaged on the project at any one time, which was completed after three years, which included a delay of 12 months.

Imperial era and aftermath

The opera house was officially opened on , with a performance ofcantata

A cantata (; ; literally "sung", past participle feminine singular of the Italian language, Italian verb ''cantare'', "to sing") is a vocal music, vocal Musical composition, composition with an musical instrument, instrumental accompaniment, ty ...

''Kyiv'', especially composed by the Swedish Wilhelm Harteveld

Julius Napoleon Wilhelm Harteveld (5 April 1859 � ...

Julius Napoleon Wilhelm Harteveld (5 April 1859 � ...

, and a presentation of ''A Life for the Tsar''. Not all the responses to the new opera house were positive. One newspaper referred to the building as “quite unattractive”, comparing it to “a giant clumsy tortoise” in the middle of the square. The interior was criticised in an article for its simplicity, whilst at the same time having “moderate exquisiteness”. A  Julius Napoleon Wilhelm Harteveld (5 April 1859 � ...

Julius Napoleon Wilhelm Harteveld (5 April 1859 � ...critic

A critic is a person who communicates an assessment and an opinion of various forms of creative works such as Art criticism, art, Literary criticism, literature, Music journalism, music, Film criticism, cinema, Theater criticism, theater, Fas ...

writing in Kievlyanin

''Kievlyanin'' () was a conservative Russian newspaper, published in Kyiv in 1864–1919.

The newspaper was labeling Ukrainians as "Mazepinists" (precursor of Banderites). Ukrainian poet and statesman Pavlo Tychyna considered the publishing as "c ...

commented on the interior of the opera house, and the expense incurred in completing the new building: "The auditorium of the new theatre is quite comfortable, but most of the boxes are excessively narrow and uncomfortable. In total, the hall has 11 exits, but, gentlemen, they are impossible to find! And another question—860,000 rubles were spent on the construction of the theatre, which is 360,000 more than planned, why haven't the people of Kyiv been informed of the reasons for such outrageous overspends?" The opera house was one of the first theatres in Europe to operate the equipment with electricity. Another innovation for the time was the use of a safety curtain

A safety curtain (or fire curtain in America) is a passive fire protection feature used in large proscenium Theater (structure), theatres. It is usually a heavy fabric curtain located immediately behind the proscenium arch. Asbestos-based mate ...

.

On the day of the opening, prayer were said by the clergy, the opera house was sprinkled with

On the day of the opening, prayer were said by the clergy, the opera house was sprinkled with holy water

Holy water is water that has been blessed by a member of the clergy or a religious figure, or derived from a well or spring considered holy. The use for cleansing prior to a baptism and spiritual cleansing is common in several religions, from ...

. Guests were then invited on to the stage, and a group photograph was taken. The ' declared: “Today is a day of great celebration for Kyiv

Kyiv, also Kiev, is the capital and most populous List of cities in Ukraine, city of Ukraine. Located in the north-central part of the country, it straddles both sides of the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2022, its population was 2, ...

music lovers. No matter how much public figures complain about the fact that we have a lack of hospitals, a million-dollar theatre has been built—the music lover triumphs!"

Until 1918, a private Russian opera company rented the opera house from the city authorities.

On 1 September 1911, during a visit to the opera to see a performance given in honour of Tsar Nicholas II

Nicholas II (Nikolai Alexandrovich Romanov; 186817 July 1918) or Nikolai II was the last reigning Emperor of Russia, King of Congress Poland, and Grand Duke of Finland from 1 November 1894 until his abdication on 15 March 1917. He married ...

's visit to Kyiv

Kyiv, also Kiev, is the capital and most populous List of cities in Ukraine, city of Ukraine. Located in the north-central part of the country, it straddles both sides of the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2022, its population was 2, ...

, the Prime Minister and Minister of Internal Affairs of the Russian Empire, Pyotr Stolypin

Pyotr Arkadyevich Stolypin ( rus, Пётр Аркадьевич Столыпин, p=pʲɵtr ɐrˈkadʲjɪvʲɪtɕ stɐˈlɨpʲɪn; – ) was a Russian statesman who served as the third Prime Minister of Russia, prime minister and the Ministry ...

, was mortally wounded by an assassin, who fired two bullets at him. He died of his injuries four days later, and was buried on the territory of the Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra.

Between 1893 and 1919, a ballet company

A ballet company is a type of dance troupe that performs classical ballet, neoclassical ballet, and/or contemporary ballet in the European tradition, plus managerial and support staff. Most major ballet companies employ dancers on a year-rou ...

directed by Polish choreographer

Choreography is the art of designing sequences of movements of physical bodies (or their depictions) in which Motion (physics), motion or Visual appearance, form or both are specified. ''Choreography'' may also refer to the design itself. A chor ...

s was employed at the theatre. In June 1917, the First Universal of the Ukrainian Central Council

The First Universals (Central Rada), Universal of the Ukrainian Central Rada (Council) () is a state-political act, the universal of the Central Rada, Central Rada (Council) of Ukraine, which proclaimed the autonomy of Ukraine. Accepted in Kyiv. T ...

on Ukraine's autonomy was proclaimed at the session of the in the opera house. In 1918, the Hetmanate of Pavlo Skoropadskyi

Pavlo Petrovych Skoropadskyi (; – 26 April 1945) was a Ukrainian aristocrat, military and state leader, who served as the Hetman of all Ukraine, hetman of the Ukrainian State throughout 1918 following a 1918 Ukrainian coup d'état, coup d'éta ...

encouraged the opera's repertoire was translated into Ukrainian, and the opera house was renamed the Ukrainian Theatre of Drama and Opera.

Soviet era

After the Soviets came to power, development of Ukrainian national culture ceased, and there were demands to permanently close the opera house. Despite these demands, the efforts of cultural figures such as the Russian singerLeonid Sobinov

Leonid Vitalyevich Sobinov (, 7 June S 26 May1872 – 14 October 1934) was an Imperial Russian operatic tenor. His fame continued unabated into the Soviet Union, Soviet era, and he was made a People's Artist of the RSFSR in 1923. Sobinov's vo ...

meant that the opera company was saved. Between 1919 and 1939, the opera house received a succession of different names:

* the ''State Opera House named after K. Liebknecht'' (following nationalized

Nationalization (nationalisation in British English)

is the process of transforming privately owned assets into public assets by bringing them under the public ownership of a national government or state. Nationalization contrasts with priv ...

after the establishment of Soviet power, renamed on 15 March 1919);

* the ''Kyiv State Academic Ukrainian Opera'' (1926);

* the ''Academic Opera and Ballet Theatre of the Ukrainian SSR

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, abbreviated as the Ukrainian SSR, UkrSSR, and also known as Soviet Ukraine or just Ukraine, was one of the Republics of the Soviet Union, constituent republics of the Soviet Union from 1922 until 1991. ...

'' (1934)

* the ''Kyiv National Academic Theatre of Opera and Ballet named after T.G. Shevchenko'' (5 March 1939, the 125th anniversary of the poet's birth).

The first Ukrainian ballets, , by Mykhailo Verykivsky (1931), , by Borys Yanovsky

Borys Karlovych Yanovskyi or Janowsky () (31 December 1875, Moscow19 January 1933, Kharkiv) was a Russian/Ukrainian composer, music critic, conductor and teacher of German origin. His actual surname was Siegl. Yanovskyi lived and worked in St. Pe ...

(1932). During the 1930s, the Soviet government

The Government of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) was the executive and administrative organ of the highest body of state authority, the All-Union Supreme Soviet. It was formed on 30 December 1922 and abolished on 26 December 199 ...

made plans to alter the opera house which to give a more acceptable to the proletariat

The proletariat (; ) is the social class of wage-earners, those members of a society whose possession of significant economic value is their labour power (their capacity to work). A member of such a class is a proletarian or a . Marxist ph ...

. The plans were never implemented. When the capital of Ukraine was transferred to Kyiv

Kyiv, also Kiev, is the capital and most populous List of cities in Ukraine, city of Ukraine. Located in the north-central part of the country, it straddles both sides of the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2022, its population was 2, ...

in 1934, the opera company was reorganised. Soloists from the Kharkiv Opera joined the team, and the choir, orchestra, and ballet corps were enlarged.

On 15 June 1941, the opera house's regular season ended with a performance of Giuseppe Verdi

Giuseppe Fortunino Francesco Verdi ( ; ; 9 or 10 October 1813 – 27 January 1901) was an Italian composer best known for List of compositions by Giuseppe Verdi, his operas. He was born near Busseto, a small town in the province of Parma ...

's opera ''Otello

''Otello'' () is an opera in four acts by Giuseppe Verdi to an Italian libretto by Arrigo Boito, based on William Shakespeare, Shakespeare's play ''Othello''. It was Verdi's penultimate opera, first performed at the La Scala, Teatro alla Scala, M ...

'', a week before the start of the German invasion of the USSR

Operation Barbarossa was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and several of its European Axis powers, Axis allies starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during World War II. More than 3.8 million Axis troops invaded the western Soviet ...

on 22 June. Following the invasion, the theatre's employees were evacuated to the Russian cities of Ufa

Ufa is a city in Russia and the capital of the republic of Bashkortostan.

UFA or Ufa may also refer to:

Places

* Ufa (river), a river in Russia; a tributary of the Belaya

* Ufa International Airport, near the Russian city

* Ufa railway statio ...

(from 1941) and Irkutsk

Irkutsk ( ; rus, Иркутск, p=ɪrˈkutsk; Buryat language, Buryat and , ''Erhüü'', ) is the largest city and administrative center of Irkutsk Oblast, Russia. With a population of 587,891 Irkutsk is the List of cities and towns in Russ ...

(19421944). They continued to perform their Kyiv repertoire, but also staged new works, such as Verykivsky's opera .

Resistance fighters

During World War II, resistance movements operated in German-occupied Europe by a variety of means, ranging from non-cooperation to propaganda, hiding crashed pilots and even to outright warfare and the recapturing of towns. In many countries, r ...

in Kyiv

Kyiv, also Kiev, is the capital and most populous List of cities in Ukraine, city of Ukraine. Located in the north-central part of the country, it straddles both sides of the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2022, its population was 2, ...

planned to blow up the opera house to kill Nazi

Nazism (), formally named National Socialism (NS; , ), is the far-right politics, far-right Totalitarianism, totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During H ...

officers during a theatrical performance, and mined the basement. The Germans demined the basements, and re-opened the opera house, starting with a performance on 27 November 1941. The newly appointed German director replaced Russian works with German operas (sung in German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany, the country of the Germans and German things

**Germania (Roman era)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizenship in Germany, see also Ge ...

). He permitted the staging of Italian operas sung in Ukrainian, as well as Ukrainian works of the pre-Soviet period. Musicians were incarcerated in the opera house and forced to rehearse day and night in preparation for any new opera. In May 1943, the building was hit by a bomb, which came through both the roof and the floor, killing several German officers. It landed in the sand-filled basement, but didn't explode. During the war, the opera house's props and costumes were looted by the Germans. In 1945, they were discovered by the Soviets near Königsberg

Königsberg (; ; ; ; ; ; , ) is the historic Germany, German and Prussian name of the city now called Kaliningrad, Russia. The city was founded in 1255 on the site of the small Old Prussians, Old Prussian settlement ''Twangste'' by the Teuton ...

, and were returned to Kyiv

Kyiv, also Kiev, is the capital and most populous List of cities in Ukraine, city of Ukraine. Located in the north-central part of the country, it straddles both sides of the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2022, its population was 2, ...

.

Operas by Ukrainian composers staged during this the Soviet period included Borys Lyatoshynsky

Borys Mykolaiovych Lyatoshynsky, also known as Boris Nikolayevich Lyatoshinsky, (3 January 189515 April 1968) was a List of Ukrainian composers, Ukrainian composer, conductor, and teacher. A leading member of the new generation of 20th century ...

’s '' The Golden Ring'' (staged in 1930), Kostiantyn Dankevych’s ' (in 1951), ''Taras Bulba

''Taras Bulba'' (; ) is a romanticized historical novella set in the first half of the 17th century, written by Nikolai Gogol (1809–1852). It features elderly Zaporozhian Cossack Taras Bulba and his sons Andriy and Ostap. The sons study at th ...

'' by Lysenko (in 1955), and ''Taras Shevchenko'' by Heorhiy Maiboroda

Heorhiy Ilarionovych Maiboroda (6 December 1992) was a Soviet and Ukrainian composer. People's Artist of the USSR (1960).

Maiboroda, whose brother Platon Maiboroda was also a composer (mainly of songs), studied at the Glière College of Music ...

(in 1964).

Restoration in the 1980s

During the 1980s it became evident that the scenery operating mechanisms were obsolete, and that both the exterior and interior was in need of restoration.Subsidence

Subsidence is a general term for downward vertical movement of the Earth's surface, which can be caused by both natural processes and human activities. Subsidence involves little or no horizontal movement, which distinguishes it from slope mov ...

was discovered, and cracks were found in the foundations, caused by the building being erected on the site of the former ravine.

Between 1984 and 1987, a complete restoration was undertaken by the Dipromisto institute, managed by and , and experts from the . The interior design was retained and enriched. The foyer and the halls were renovated; the oak wardrobes were moved to the ground floor. Rehearsal and dressing rooms were added. The depth of the stage was increased to and its height was increased to. The original organ

Organ and organs may refer to:

Biology

* Organ (biology), a group of tissues organized to serve a common function

* Organ system, a collection of organs that function together to carry out specific functions within the body.

Musical instruments

...

was replaced and the orchestra pit

An orchestra pit is an area in a theatre (usually located in a lowered area in front of the stage) in which musicians perform. The orchestra plays mostly out of sight in the pit, rather than on the stage as for a concert, when providing music fo ...

enlarged to enable it to hold 100 instrumentalists. The opera house's internal area was also enlarged, allowing up to 1304 people to attend performances; the standing area in front of the stage was removed. A huge hole was excavated several stories deep in the square outside, in which a new power plant, ventilation machinery, and a wardrobe was installed.

The opera house reopened on 22 March 1988, with a performance of ''Taras Bulba''.

Post-independence

In 1994, the opera house was renamed as the National Academic Opera and Ballet Theatre of Ukraine named after Taras Shevchenko.Architecture

At the time of its opening in 1901, the stage of the Kyiv Opera House was the biggest in the Russian Empire, being wide, deep, and high. The ground level parterre could seat 384 people, and in total there were 1650 audience seats. The theatre building had a steam-heating system, and air conditioning.Exterior

The exterior of Kyiv Opera House was designed in theRenaissance Revival

Renaissance Revival architecture (sometimes referred to as "Neo-Renaissance") is a group of 19th-century architectural revival styles which were neither Greek Revival nor Gothic Revival but which instead drew inspiration from a wide range of ...

style. The main part of the building is built with brick, steel and reinforced concrete. The front steps are made of white marble

Marble is a metamorphic rock consisting of carbonate minerals (most commonly calcite (CaCO3) or Dolomite (mineral), dolomite (CaMg(CO3)2) that have recrystallized under the influence of heat and pressure. It has a crystalline texture, and is ty ...

, with other features being built in granite

Granite ( ) is a coarse-grained (phanerite, phaneritic) intrusive rock, intrusive igneous rock composed mostly of quartz, alkali feldspar, and plagioclase. It forms from magma with a high content of silica and alkali metal oxides that slowly coo ...

and artificial stone

Artificial stone is a name for various synthetic stone products produced from the 18th century onward. Uses include statuary, architectural details, fencing and rails, building construction, civil engineering work, and industrial applications su ...

. The interior plaster

Plaster is a building material used for the protective or decorative coating of walls and ceilings and for moulding and casting decorative elements. In English, "plaster" usually means a material used for the interiors of buildings, while "re ...

decorations are painted and gilded

Gilding is a decorative technique for applying a very thin coating of gold over solid surfaces such as metal (most common), wood, porcelain, or stone. A gilded object is also described as "gilt". Where metal is gilded, the metal below was tradi ...

. The building's location in Kyiv was carefully chosen to ensure that it fitted within the architectural and natural landscape.

The exterior is decorated with rosette

Rosette is the French diminutive of ''rose''. It may refer to:

Flower shaped designs

* Rosette (award), a mark awarded by an organisation

* Rosette (design), a small flower design

*hence, various flower-shaped or rotational symmetric forms:

** R ...

s and masks. The Greek muse

In ancient Greek religion and Greek mythology, mythology, the Muses (, ) were the Artistic inspiration, inspirational goddesses of literature, science, and the arts. They were considered the source of the knowledge embodied in the poetry, lyric p ...

s Melpomene

Melpomene (; ) is the Muse of tragedy in Greek mythology. She is described as the daughter of Zeus and Mnemosyne (and therefore of power and memory) along with the other Muses, and she is often portrayed with a tragic theatrical mask.

Etymolog ...

and Terpsichore

In Greek mythology, Terpsichore (; , "delight in dancing") is one of the nine Muses and goddess of dance and chorus. She lends her name to the word " terpsichorean", which means "of or relating to dance".

Appearance

Terpsichore is usually d ...

, made by the sculptor

Sculpture is the branch of the visual arts that operates in three dimensions. Sculpture is the three-dimensional art work which is physically presented in the dimensions of height, width and depth. It is one of the plastic arts. Durable sc ...

Emilio Sala, are above the entrance. The building has a curved façade

A façade or facade (; ) is generally the front part or exterior of a building. It is a loanword from the French language, French (), which means "frontage" or "face".

In architecture, the façade of a building is often the most important asp ...

decorated with stucco

Stucco or render is a construction material made of aggregates, a binder, and water. Stucco is applied wet and hardens to a very dense solid. It is used as a decorative coating for walls and ceilings, exterior walls, and as a sculptural and ...

work and narrow, deep arches. It was planned that Kyiv's coat of arms

A coat of arms is a heraldry, heraldic communication design, visual design on an escutcheon (heraldry), escutcheon (i.e., shield), surcoat, or tabard (the last two being outer garments), originating in Europe. The coat of arms on an escutcheon f ...

, along with the city's patron saint

A patron saint, patroness saint, patron hallow or heavenly protector is a saint who in Catholicism, Anglicanism, Eastern Orthodoxy or Oriental Orthodoxy is regarded as the heavenly advocate of a nation, place, craft, activity, class, clan, fa ...

, the Archangel Michael

Michael, also called Saint Michael the Archangel, Archangel Michael and Saint Michael the Taxiarch is an archangel and the warrior of God in Christianity, Judaism, and Islam. The earliest surviving mentions of his name are in third- and second ...

would be placed on the roof above the entrance. After protests from the Metropolitan of Kyiv, who declared that placing an image the saint would be blasphemy

Blasphemy refers to an insult that shows contempt, disrespect or lack of Reverence (emotion), reverence concerning a deity, an object considered sacred, or something considered Sanctity of life, inviolable. Some religions, especially Abrahamic o ...

., an allegoric composition consisting of griffin

The griffin, griffon, or gryphon (; Classical Latin: ''gryps'' or ''grypus''; Late and Medieval Latin: ''gryphes'', ''grypho'' etc.; Old French: ''griffon'') is a -4; we might wonder whether there's a point at which it's appropriate to talk ...

s holding a lyre

The lyre () (from Greek λύρα and Latin ''lyra)'' is a string instrument, stringed musical instrument that is classified by Hornbostel–Sachs as a member of the History of lute-family instruments, lute family of instruments. In organology, a ...

was used instead.

In 1905, busts of Glinka and the Russian composer Alexander Serov

Alexander Nikolayevich Serov (, – ) was a Russian composer and music critic. He is notable as one of the most important music critics in Russia during the 1850s and 1860s and as the most significant Russian composer in the period betwee ...

were donated by the , and installed on either side of the central arch. These were removed when the opera house was renovated in 1934. During the 1988 restoration, a bronze

Bronze is an alloy consisting primarily of copper, commonly with about 12–12.5% tin and often with the addition of other metals (including aluminium, manganese, nickel, or zinc) and sometimes non-metals (such as phosphorus) or metalloid ...

bust of Taras Shevchenko

Taras Hryhorovych Shevchenko (; ; 9 March 1814 – 10 March 1861) was a Ukrainian poet, writer, artist, public and political figure, folklorist, and ethnographer. He was a fellow of the Imperial Academy of Arts and a member of the Brotherhood o ...

by the sculptor was placed in the central arch above the entrance.

Interior

The interior of Kyiv Opera House is notable for its Italian Neoclassical interior design features, such as Venetian mirrors, gilding, stucco work on the walls and ceilings, marble stairways and mosaic floors; velvet armchairs, and subtle lighting. Soon after the opera house opened, both the artists and the audience praised itsacoustics

Acoustics is a branch of physics that deals with the study of mechanical waves in gases, liquids, and solids including topics such as vibration, sound, ultrasound and infrasound. A scientist who works in the field of acoustics is an acoustician ...

. They were considered to be excellent, in part due to the walls and columns of the auditorium having reeds

Reed or Reeds may refer to:

Science, technology, biology, and medicine

* Reed bird (disambiguation)

* Reed pen, writing implement in use since ancient times

* Reed (plant), one of several tall, grass-like wetland plants of the order Poales

* Re ...

embedded under the plaster.

The stage of the current theatre has a slope of about 5 degrees

Degree may refer to:

As a unit of measurement

* Degree (angle), a unit of angle measurement

** Degree of geographical latitude

** Degree of geographical longitude

* Degree symbol (°), a notation used in science, engineering, and mathematics

...

downwards, needed to create spatial perspective. Dancers and singers are trained to get used to this by being gradually transferred to rooms with increasingly sloped floors.

Notes

References

Sources

* * * *Further reading

* * *External links

Drone footage of the National Opera of Ukraine

from ZBROY Films {{coord, 50, 26, 48, N, 30, 30, 45, E, type:landmark, display=title Opera houses in Ukraine Theatres in Kyiv Art Nouveau theatres Art Nouveau architecture in Kyiv Volodymyrska Street Theatres completed in 1803 Theatres completed in 1856 Theatres completed in 1901