Lajos Kossuth de Udvard et Kossuthfalva (; ; ; ; 19 September 1802 – 20 March 1894) was a Hungarian nobleman, lawyer, journalist, politician, statesman and governor-president of the

Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from 1000 to 1946 and was a key part of the Habsburg monarchy from 1526-1918. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the Coro ...

during the

revolution of 1848–1849.

[

With the help of his talent in oratory in political debates and public speeches, Kossuth emerged from a poor gentry family into regent-president of the Kingdom of Hungary. As the influential contemporary American journalist ]Horace Greeley

Horace Greeley (February 3, 1811 – November 29, 1872) was an American newspaper editor and publisher who was the founder and newspaper editor, editor of the ''New-York Tribune''. Long active in politics, he served briefly as a congres ...

said of Kossuth: "Among the orators, patriots, statesmen, exiles, he has, living or dead, no superior."

Kossuth's powerful English and American speeches so impressed and touched the famous contemporary American orator Daniel Webster

Daniel Webster (January 18, 1782 – October 24, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented New Hampshire and Massachusetts in the U.S. Congress and served as the 14th and 19th United States Secretary of State, U.S. secretary o ...

, that he wrote a book about Kossuth's life.freedom fighter

A freedom fighter is a person engaged in a struggle to achieve political freedom, particularly against an established government. The term is typically reserved for those who are actively involved in armed or otherwise violent rebellion.

Termi ...

and bellwether

A bellwether is a leader or an indicator of trends.[bellwether]

" ''Cambridge Dictionary''. Re ...

of democracy in Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

. Kossuth's bronze bust can be found in the United States Capitol

The United States Capitol, often called the Capitol or the Capitol Building, is the Seat of government, seat of the United States Congress, the United States Congress, legislative branch of the Federal government of the United States, federal g ...

with the inscription: ''Father of Hungarian Democracy, Hungarian Statesman, Freedom Fighter, 1848–1849''. Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels ( ;["Engels"](_blank)

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''.[Danton

Georges Jacques Danton (; ; 26 October 1759 – 5 April 1794) was a leading figure of the French Revolution. A modest and unknown lawyer on the eve of the Revolution, Danton became a famous orator of the Cordeliers Club and was raised to gover ...]

and Carnot in one person...".

Early years

Lajos Kossuth was born into an untitled lower noble (gentry) family in Monok

Monok is a village in Borsod-Abaúj-Zemplén, Hungary and is part of the Tokaj wine region.

Geography

The nearest town is Szerencs away. Neighbouring villages are Golop away, Legyesbénye away and Tállya away.

The Zemplén Mountains h ...

, Kingdom of Hungary, a small town in the county of Zemplén in modern-day Borsod-Abaúj-Zemplén County of Northern Hungary

Northern Hungary (, ) is a region in Hungary. As a statistical region it includes the counties Borsod-Abaúj-Zemplén, Heves and Nógrád, but in colloquial speech it usually also refers to Szabolcs-Szatmár-Bereg county. The region is in the ...

. He was the eldest of five children in a Lutheran

Lutheranism is a major branch of Protestantism that emerged under the work of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German friar and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practices of the Catholic Church launched ...

noble family of Slovak origin. His father, László Kossuth (1762–1839), belonged to the lower nobility

The minor or petty nobility is the lower nobility classes.

Finland

Petty nobility in Finland is dated at least back to the 13th century and was formed by nobles around their strategic interests. The idea was more capable peasants with leader role ...

, had a small estate and was a lawyer by profession. László had two brothers ( Simon Kossuth and György Kossuth) and one sister, Zsuzsanna

Zsuzsanna is the Hungarian form of the feminine given name Susanna.

Notable bearers

*Zsuzsanna Budapest (born 1940), American author of Hungarian origin who writes on feminist spirituality

* Zsuzsanna Csobánki (born 1983), female Hungarian swim ...

.

The family moved from Monok to Olaszliszka in 1803, and then to Sátoraljaújhely

Sátoraljaújhely (German language, German: ''Neustadt am Zeltberg''; Slovak language, Slovak: ''Nové Mesto pod Šiatrom;'' Yiddish: ''איהעל'') is a border town located in Borsod–Abaúj–Zemplén County, Borsod-Abaúj-Zemplén County, Hu ...

in 1808. Lajos had four younger sisters.

Lajos' mother, Karolina, raised her children as strict Lutherans. As a result of their mixed ancestry, and as was quite common during his era, her children spoke three languages – Hungarian, German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany, the country of the Germans and German things

**Germania (Roman era)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizenship in Germany, see also Ge ...

and Slovak – even in their early childhood.

Lajos studied at the Piarist

The Piarists (), officially named the Order of Poor Clerics Regular of the Mother of God of the Pious Schools (), abbreviated SchP, is a religious order of clerics regular of the Catholic Church founded in 1617 by Spanish priest Joseph Calasanz ...

college of Sátoraljaújhely

Sátoraljaújhely (German language, German: ''Neustadt am Zeltberg''; Slovak language, Slovak: ''Nové Mesto pod Šiatrom;'' Yiddish: ''איהעל'') is a border town located in Borsod–Abaúj–Zemplén County, Borsod-Abaúj-Zemplén County, Hu ...

and the Calvinist

Reformed Christianity, also called Calvinism, is a major branch of Protestantism that began during the 16th-century Protestant Reformation. In the modern day, it is largely represented by the Continental Reformed Protestantism, Continenta ...

college of Sárospatak

Sárospatak (; ; Serbian language, Serbian: Муд Стреам; Slovak language, Slovakian: ''Šarišský Potok, Blatný Potok)''

History

The area has been inhabited since ancient times. Sárospatak was granted town status in 1201 by Emeric ...

(for one year) and the University of Pest

A university () is an institution of tertiary education and research which awards academic degrees in several academic disciplines. ''University'' is derived from the Latin phrase , which roughly means "community of teachers and scholars". Univ ...

(now Budapest

Budapest is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns of Hungary, most populous city of Hungary. It is the List of cities in the European Union by population within city limits, tenth-largest city in the European Union by popul ...

). At nineteen he entered his father's legal practice. Between 1824 and 1832 he practiced law in his native Zemplén County. His career quickly took off, thanks also to his father, who was a lawyer for several higher aristocratic families, and thus involved his son in the administration, and his son soon took over some of his father's work. He first became a lawyer in the Lutheran parish of Sátoraljaújhely, in 1827 he became a judge, and later he became a prosecutor in Sátoraljaújhely. During this time, in addition to his office work, he made historical chronologies and translations. In the national census of 1828, in which taxpayers were counted in order to eliminate tax disparities, Kossuth assisted in the organization of the census of Zemplén county. He was popular locally, and having been appointed steward to the countess Szapáry, a widow with large estates, he became her voting representative in the county assembly and settled in Pest. He was subsequently dismissed on the grounds of some misunderstanding in regards to estate funds.

Ancestry

The House of Kossuth, into which Lajos was born, originated from the county of Turóc (now partially

The House of Kossuth, into which Lajos was born, originated from the county of Turóc (now partially Turiec

Turiec is a region in central Slovakia, one of the 21 official tourism regions. The region is not an administrative division today, but between the late 11th century and 1920 it was the Turóc County in the Kingdom of Hungary.

Etymology

The re ...

region, Košúty, north-central Slovakia

Slovakia, officially the Slovak Republic, is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the west, and the Czech Republic to the northwest. Slovakia's m ...

). They acquired the rank of nobility in 1263 from King Béla IV

Béla may refer to:

* Béla (crater), an elongated lunar crater

* Béla (given name), a common Hungarian male given name

See also

* Bela (disambiguation)

* Belá (disambiguation)

* Bělá (disambiguation) Bělá may refer to:

Places in the Cze ...

.Upper Hungary

Upper Hungary (, "Upland"), is the area that was historically the northern part of the Kingdom of Hungary, now mostly present-day Slovakia. The region has also been called ''Felső-Magyarország'' ( literally: "Upper Hungary"; ).

During the ...

(today partially Slovakia).

Family-tree

Entry into national politics

Shortly after his dismissal by Countess Szapáry, Kossuth was appointed as deputy to Count Hunyady at the Diet of Hungary

The Diet of Hungary or originally: Parlamentum Publicum / Parlamentum Generale () was the most important political assembly in Hungary since the 12th century, which emerged to the position of the supreme legislative institution in the Kingdom ...

. The Diet met during 1825–27 and 1832–36 in Pressburg

Bratislava (German: ''Pressburg'', Hungarian: ''Pozsony'') is the Capital city, capital and largest city of the Slovakia, Slovak Republic and the fourth largest of all List of cities and towns on the river Danube, cities on the river Danube. ...

(Pozsony, present Bratislava), then capital of Hungary.

Only the upper aristocracy could vote in the House of Magnates

The House of Magnates (; ; ; ) was the upper chamber of the Diet of Hungary. This chamber was operational from 1867 to 1918 and subsequently from 1927 to 1945.

The house was, like the current House of Lords in the United Kingdom, composed of ...

(similar to the British House of Lords

The House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the lower house, the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England. One of the oldest ext ...

) and Kossuth took little part in the debates as a deputy of Count Hunyady. At the time, a struggle to reassert a Hungarian national identity was beginning to emerge under leaders such as Miklós Wesselényi

Baron Miklós Wesselényi de Hadad (; archaically English: Nicholas Wesselényi;Robert J. Hunter : Racing Calendar - Page xxv 1842 20 December 179621 April 1850) was a Hungarian statesman, leader of the upper house of the Diet, member of the Bo ...

and the Széchenyis. In part, it was also a struggle for fundamental economic and political and societal reforms against the stagnant and conservative Austrian

Austrian may refer to:

* Austrians, someone from Austria or of Austrian descent

** Someone who is considered an Austrian citizen

* Austrian German dialect

* Something associated with the country Austria, for example:

** Austria-Hungary

** Austria ...

government. Kossuth's duties to Count Hunyady included reporting on Diet proceedings in writing, as the Austrian government, fearing popular dissent, had banned published reports.

The high quality of Kossuth's letters led to their being circulated in manuscript among other liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* Generally, a supporter of the political philosophy liberalism. Liberals may be politically left or right but tend to be centrist.

* An adherent of a Liberal Party (See also Liberal parties by country ...

magnates. Readership demands led him to edit an organized parliamentary gazette (''Országgyűlési tudósítások''); spreading his name and influence further. Orders from the Official Censor halted circulation by lithograph

Lithography () is a planographic method of printing originally based on the miscibility, immiscibility of oil and water. The printing is from a stone (lithographic limestone) or a metal plate with a smooth surface. It was invented in 1796 by ...

printing. Distribution in manuscript by post was forbidden by the government, although circulation by hand continued.

In 1836, the Diet was dissolved. Kossuth continued to report (in letter form), covering the debates of the county assemblies. The newfound publicity gave the assemblies national political prominence. Previously, they had had little idea of each other's proceedings. His embellishment of the speeches from the liberals and reformers enhanced the impact of his newsletters. After the prohibition of his parliamentary gazette, Kossuth loudly demanded the legal declaration of freedom of the press

Freedom of the press or freedom of the media is the fundamental principle that communication and expression through various media, including printed and electronic Media (communication), media, especially publication, published materials, shoul ...

and of speech in Hungary and in the entire Habsburg Empire. The government attempted in vain to suppress the letters, and, other means having failed, he was arrested in May 1837, with Wesselényi and several others, on a charge of high treason.

After spending a year in prison at Buda

Buda (, ) is the part of Budapest, the capital city of Hungary, that lies on the western bank of the Danube. Historically, “Buda” referred only to the royal walled city on Castle Hill (), which was constructed by Béla IV between 1247 and ...

awaiting trial, he was condemned to four more years' imprisonment. Kossuth and his friend Count Miklós Wesselényi

Baron Miklós Wesselényi de Hadad (; archaically English: Nicholas Wesselényi;Robert J. Hunter : Racing Calendar - Page xxv 1842 20 December 179621 April 1850) was a Hungarian statesman, leader of the upper house of the Diet, member of the Bo ...

were placed in separated solitary cells. Count Wesselényi's cell did not have even a window, and he went blind in the darkness. Kossuth, however, had a small window and with the help of a politically well-informed young woman, Theresa Meszlényi, he remained informed about political events. Meszlényi lied to the prison commander, telling him she and Kossuth were engaged. In reality, Kossuth did not know Meszlényi before his imprisonment, but this permitted her to visit. Meszlényi also provided books. Strict confinement damaged Kossuth's health, but he spent much time reading. He greatly increased his political knowledge and acquired fluency in English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Culture, language and peoples

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

* ''English'', an Amish ter ...

from study of the King James Version

The King James Version (KJV), also the King James Bible (KJB) and the Authorized Version (AV), is an Early Modern English Bible translations, Early Modern English translation of the Christianity, Christian Bible for the Church of England, wh ...

of the Bible

The Bible is a collection of religious texts that are central to Christianity and Judaism, and esteemed in other Abrahamic religions such as Islam. The Bible is an anthology (a compilation of texts of a variety of forms) originally writt ...

and William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 23 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

which he henceforth always spoke with a certain archaic eloquence. While Wesselényi was broken mentally, Kossuth, supported by Terézia Meszlényi's frequent visits, emerged from prison in much better condition. His arrest had caused great controversy. The Diet, which reconvened in 1839, demanded the release of the political prisoners and refused to pass any government measures. Austrian chancellor Metternich

Klemens Wenzel Nepomuk Lothar, Prince of Metternich-Winneburg zu Beilstein ( ; 15 May 1773 – 11 June 1859), known as Klemens von Metternich () or Prince Metternich, was a Germans, German statesman and diplomat in the service of the Austrian ...

long remained obdurate, but the danger of war in 1840 obliged him to give way.

Marriage and children

On the day of his release from the prison, Kossuth and Meszlényi were married, and she remained a firm supporter of his politics. She was a Catholic and her Church refused to bless the marriage since Kossuth, a proud Protestant, would not convert. At the time of their marriage it was unheard of that people of different religions married. According to the traditional practice, the bride or more rarely the fiancé had to convert to the religion of his or her spouse before the wedding ceremony. However Kossuth refused to convert to Roman Catholicism, and Meszlényi also refused to convert to Lutheranism. Their mixed religious marriage caused a great scandal at the time. This experience influenced Kossuth's firm defense of mixed marriages. The couple had three children: Ferenc Lajos Ákos (1841–1914), Minister for Trade between 1906 and 1910; Vilma (1843–1862); and Lajos Tódor Károly (1844–1918).

Journalist and political leader

Kossuth had now become a national icon. He regained full health in January 1841. In January 1841 he became editor of the Pesti Hírlap. The job was offered to him by Lajos Landerer, the owner of a big printing house company in Pest (in fact, Landerer was an undercover agent of the Vienna secret police).

The government circles and the secret police believed that censorship and financial interests would curtail Kossuth's opposition, and they did not consider the small circulation of the paper to be dangerous anyway. However, Kossuth created modern Hungarian political journalism. His editorials dealt with the pressing problems of the economy, the social injustices and the existing legal inequality of the common people. The articles combined a critique of the present with an outline of the future, combining and supplementing the reform ideas that had emerged up to that point into a coherent programme.

The paper achieved unprecedented success, soon reaching the then immense circulation of 7000 copies. A competing pro-government newspaper, ''Világ''(World), started up, but despite its attacks against Kossuth's ideas, it became counterproductive, and it only served to increase Kossuth's visibility and add to the general political fervor.

Kossuth's ideas stand on the enlightened Western European type liberal nationalism

Civic nationalism, otherwise known as democratic nationalism, is a form of nationalism that adheres to traditional liberal values of freedom, tolerance, equality, and individual rights, and is not based on ethnocentrism. Civic nationalists of ...

(based on the "jus soli

''Jus soli'' ( or , ), meaning 'right of soil', is the right of anyone born in the territory of a state to nationality or citizenship. ''Jus soli'' was part of the English common law, in contrast to ''jus sanguinis'' ('right of blood') ass ...

" principle, that is the complete opposition of the typical Eastern European ethnic nationalism

Ethnic nationalism, also known as ethnonationalism, is a form of nationalism wherein the nation and nationality are defined in terms of ethnicity, with emphasis on an ethnocentric (and in some cases an ethnostate/ethnocratic) approach to variou ...

, which based on "jus sanguinis

( or , ), meaning 'right of blood', is a principle of nationality law by which nationality is determined or acquired by the nationality of one or both parents. Children at birth may be nationals of a particular state if either or both of thei ...

").

Kossuth followed the ideas of the French nation state ideology, which was a ruling liberal idea of his era. Accordingly, he considered and regarded automatically everybody as "Hungarian" – regardless of their mother tongue and ethnic ancestry – who were born and lived in the territory of Hungary. He even quoted King Stephen I of Hungary

Stephen I, also known as King Saint Stephen ( ; ; ; 975 – 15 August 1038), was the last grand prince of the Hungarians between 997 and 1000 or 1001, and the first king of Hungary from 1000 or 1001 until his death in 1038. The year of his bi ...

's admonition: "A nation of one language and the same customs is weak and fragile."

Kossuth pleaded in the newspaper ''Pesti Hírlap'' for rapid Magyarization

Magyarization ( , also Hungarianization; ), after "Magyar"—the Hungarian autonym—was an assimilation or acculturation process by which non-Hungarian nationals living in the Kingdom of Hungary, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, adop ...

: "Let us hurry, let us hurry to Magyarize the Croats

The Croats (; , ) are a South Slavs, South Slavic ethnic group native to Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and other neighboring countries in Central Europe, Central and Southeastern Europe who share a common Croatian Cultural heritage, ancest ...

, the Romanians

Romanians (, ; dated Endonym and exonym, exonym ''Vlachs'') are a Romance languages, Romance-speaking ethnic group and nation native to Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. Sharing a Culture of Romania, ...

, and the Saxons

The Saxons, sometimes called the Old Saxons or Continental Saxons, were a Germanic people of early medieval "Old" Saxony () which became a Carolingian " stem duchy" in 804, in what is now northern Germany. Many of their neighbours were, like th ...

, for otherwise we shall perish". In 1842 he argued that Hungarian had to be the exclusive language in public life. He also stated that "in one country it is impossible to speak in a hundred different languages. There must be one language and in Hungary this must be Hungarian".

Kossuth's assimilatory ambitions were disapproved by Zsigmond Kemény

Baron Zsigmond Kemény (June 12, 1814December 22, 1875) was a writer from the Austrian Empire.

Life and work

Kemény was born in Alvincz, Principality of Transylvania, Austrian Empire (today Vințu de Jos, Romania) to a distinguished noble fam ...

, though he supported a multinational state led by Hungarians. István Széchenyi

Count István Széchenyi de Sárvár-Felsővidék (, ; archaically English: Stephen Széchenyi; 21 September 1791 – 8 April 1860) was a Hungarian politician, political theorist, and writer. Widely considered one of the greatest statesme ...

criticized Kossuth for "pitting one nationality against another". He publicly warned Kossuth that his appeals to the passions of the people would lead the nation to revolution. Kossuth, undaunted, did not stop at the publicly reasoned reforms demanded by all Liberals: the abolition of entail

In English common law, fee tail or entail is a form of trust, established by deed or settlement, that restricts the sale or inheritance of an estate in real property and prevents that property from being sold, devised by will, or otherwise ali ...

, the abolition of feudal

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was a combination of legal, economic, military, cultural, and political customs that flourished in Middle Ages, medieval Europe from the 9th to 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of struc ...

burdens and taxation of the nobles. He went on to broach the possibility of separating from the House of Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (; ), also known as the House of Austria, was one of the most powerful Dynasty, dynasties in the history of Europe and Western civilization. They were best known for their inbreeding and for ruling vast realms throughout ...

. By combining this nationalism with an insistence on the superiority of the Hungarian culture Hungarian may refer to:

* Hungary, a country in Central Europe

* Kingdom of Hungary, state of Hungary, existing between 1000 and 1946

* Hungarians/Magyars, ethnic groups in Hungary

* Hungarian algorithm, a polynomial time algorithm for solving the ...

to the culture of Slavonic inhabitants of Hungary, he sowed the seeds of both the collapse of Hungary in 1849 and his own political demise.

In 1844, Kossuth was dismissed from ''Pesti Hírlap'' after a dispute with the proprietor over salary. It is believed that the dispute was rooted in government intrigue. Kossuth was unable to obtain permission to start his own newspaper. In a personal interview, Metternich offered to take him into the government service. Kossuth refused and spent the next three years without a regular position. He continued to agitate on behalf of both political and commercial independence for Hungary. He adopted the economic principles of Friedrich List

Daniel Friedrich List (6 August 1789 – 30 November 1846) was a German entrepreneur, diplomat, economist and political theory, political theorist who developed the Economic nationalism, nationalist theory of political economy in both Europe and t ...

, and was the founder of the popular whose members consumed only Hungarian industrial products. He also argued for the creation of a Hungarian port at Fiume

Rijeka (;

Fiume ( �fjuːme in Italian and in Fiuman Venetian) is the principal seaport and the third-largest city in Croatia. It is located in Primorje-Gorski Kotar County on Kvarner Bay, an inlet of the Adriatic Sea and in 2021 had a po ...

.

Kossuth played a major role in the formation of the Opposition Party in 1847, whose programme was essentially formulated by him.

In autumn 1847, Kossuth was able to take his final key step. The support of Lajos Batthyány

Count Lajos Batthyány de Németújvár (; ; 10 February 1807 – 6 October 1849) was the first Prime Minister of Hungary. He was born in Pozsony (modern-day Bratislava) on 10 February 1807, and was executed by firing squad in Pest, Hungary, Pe ...

during a keenly fought campaign made him be elected to the new Diet as member for Pest. He proclaimed: "Now that I am a deputy, I will cease to be an agitator." He immediately became chief leader of the Opposition Party. Ferenc Deák was absent. As Headlam noted, his political rivals, Batthyány, István Széchenyi

Count István Széchenyi de Sárvár-Felsővidék (, ; archaically English: Stephen Széchenyi; 21 September 1791 – 8 April 1860) was a Hungarian politician, political theorist, and writer. Widely considered one of the greatest statesme ...

, Szemere, and József Eötvös

Baron József Eötvös de Vásárosnamény (pronunciation: jɔ:ʒef 'øtvøʃ dɛ 'va:ʃa:rɔʃnɒme:ɲ 3 September 1813 – 2 February 1871) was a Hungarian writer and statesman, the son of Ignác baron Eötvös de Vásárosnamény and ...

, believed:

The "long debate" of reformers in the press

Count Széchenyi judged the reform system of Kossuth in a pamphlet, ''Kelet Népe'' from 1841. According to Széchenyi, economic, political and social reforms must be instituted slowly and carefully so that Hungary would avoid the violent interference of the Habsburg dynasty. Széchenyi was listening to the spread of the expansion of Kossuth's ideas in Hungarian society, which did not consider good relations with the Habsburg dynasty. Kossuth believed that society could not be forced into a passive role by any reason through social change. According to Kossuth, the wider social movements can not be continually excluded from political life. Behind Kossuth's conception of society was a notion of freedom that emphasized the unitary origin of rights, which he saw manifested in universal suffrage. In exercising political rights, Széchenyi took into account wealth and education of the citizens, thus he supported only limited suffrage similar to the Western European (British, French and Belgian) limited suffrage of the era. In 1885, Kossuth called Széchenyi a liberal elitist aristocrat while Széchenyi considered himself to be a democrat.

Széchenyi was an isolationist politician while, according to Kossuth, strong relations and collaboration with international liberal and progressive movements are essential for the success of liberty. Regarding foreign policy, Kossuth and his followers refused the isolationist policy of Széchenyi, thus they stood on the ground of the liberal internationalism

Liberal internationalism is a foreign policy doctrine that supports international institutions, open markets, cooperative security, and liberal democracy. At its core, it holds that states should participate in international institutions that up ...

: They supported countries and political forces that aligned with their moral and political standards. They also believed that governments and political movements sharing the same modern liberal values should form an alliance against the "feudal type" of monarchies.

Széchenyi's economic policy based on Anglo-Saxon

The Anglo-Saxons, in some contexts simply called Saxons or the English, were a Cultural identity, cultural group who spoke Old English and inhabited much of what is now England and south-eastern Scotland in the Early Middle Ages. They traced t ...

free-market principles, while Kossuth supported the protective tariffs due to the weaker Hungarian industrial sector. Kossuth wanted to build a rapidly industrialized country in his vision while Széchenyi wanted to preserve the traditionally strong agricultural sector as the main character of the economy.

Work in the government

Minister of Finance

The crisis came, and he used it to the full. On 3 March 1848, shortly after the news of the revolution in Paris had arrived, in a speech of surpassing power he demanded parliamentary government for Hungary and constitutional government for the rest of Austria.

He appealed to the hope of the Habsburgs, "our beloved Archduke Franz Joseph

Franz Joseph I or Francis Joseph I ( ; ; 18 August 1830 – 21 November 1916) was Emperor of Austria, King of Hungary, and the ruler of the Grand title of the emperor of Austria, other states of the Habsburg monarchy from 1848 until his death ...

" (then seventeen years old), to perpetuate the ancient glory of the dynasty by meeting half-way the aspirations of a free people. He at once became the leader of the European revolution; his speech was read aloud in the streets of Vienna

Vienna ( ; ; ) is the capital city, capital, List of largest cities in Austria, most populous city, and one of Federal states of Austria, nine federal states of Austria. It is Austria's primate city, with just over two million inhabitants. ...

to the mob which overthrew Metternich (13 March); when a deputation from the Diet visited Vienna to receive the assent of Emperor Ferdinand

Ferdinand is a Germanic name composed of the elements "journey, travel", Proto-Germanic , abstract noun from root "to fare, travel" (PIE , "to lead, pass over"), and "courage" or "ready, prepared" related to Old High German "to risk, ventu ...

to their petition, Kossuth received the chief ovation. While Viennese masses celebrated Kossuth (and from the Diet in Pressburg a delegation went to Buda and sent the news of the Austrian Revolution) as their hero, revolution broke out in Buda on 15 March; Kossuth traveled home immediately. On 17 March 1848 the Emperor assented and Lajos Batthyány

Count Lajos Batthyány de Németújvár (; ; 10 February 1807 – 6 October 1849) was the first Prime Minister of Hungary. He was born in Pozsony (modern-day Bratislava) on 10 February 1807, and was executed by firing squad in Pest, Hungary, Pe ...

created the first Hungarian government, that was not anymore responsible to the King, but to the elected members of the Diet

Diet may refer to:

Food

* Diet (nutrition), the sum of the food consumed by an organism or group

* Dieting, the deliberate selection of food to control body weight or nutrient intake

** Diet food, foods that aid in creating a diet for weight loss ...

. On 23 March 1848, Pm. Batthyány commended his government to the Diet. In the new government Kossuth was appointed as the Minister of Finance.

He began developing the internal resources of the country: re-establishing a separate Hungarian coinage, and using every means to increase national self-consciousness. Characteristically, the new Hungarian bank notes had Kossuth's name as the most prominent inscription; making reference to "Kossuth Notes" a future byword.

A new paper was started, to which was given the name of ''Kossuth Hirlapja'', so that from the first it was Kossuth rather than the Palatine

A palatine or palatinus (Latin; : ''palatini''; cf. derivative spellings below) is a high-level official attached to imperial or royal courts in Europe since Roman Empire, Roman times. or prime minister Batthyány whose name was in the minds of the people associated with the new government. Much more was this the case when, in the summer, the dangers from the Croats, Serbs and the reaction at Vienna increased.

In a speech on 11 July he asked that the nation should arm in self-defense, and demanded 200,000 men; amid a scene of wild enthusiasm this was granted by acclamation. However the danger had been exacerbated by Kossuth himself through appealing exclusively to the Magyar notables rather than including the other subject minorities of the Habsburg empire too. The Austrians, meanwhile, successfully used the other minorities as allies against the Magyar uprising.

While Croatian ban Josip Jelačić

Count Josip Jelačić von Bužim (16 October 180120 May 1859; also spelled ''Jellachich'', ''Jellačić'' or ''Jellasics''; ; ) was a Croatian lieutenant field marshal in the Imperial Austrian Army and politician. He was the Ban of Croatia betw ...

was marching on Pest, the Hungarian government was in serious military crisis due to the lack of soldiers, Kossuth used his popularity, he went from town to town rousing the people to the defense of the country, and the popular force of the Honvéd was his creation. When Batthyány resigned he was appointed with Szemere to carry on the government provisionally, and at the end of September he was made President of the Committee of National Defense.

Prime minister Lajos Batthyány

Count Lajos Batthyány de Németújvár (; ; 10 February 1807 – 6 October 1849) was the first Prime Minister of Hungary. He was born in Pozsony (modern-day Bratislava) on 10 February 1807, and was executed by firing squad in Pest, Hungary, Pe ...

's desperate attempts to mediate with the Viennese royal court to achieve reconciliation and restore peace were no longer successful. Due to his unsuccessful peace missions, Batthyány slowly began to become politically isolated and increasingly lost the support of the parliament.

On 6 September, Kossuth ordered the first Hungarian banknotes to be issued to cover defence expenses.

In early September 1848, after the Habsburg King of Hungary, Ferdinand V, compelled the Batthyány government to resign, the nation found itself once more bereft of executive authority.[Hermann Róbert]

Magyarország története 14.

Kossuth Kiadó, 2009 Budapest, p. 54

The government meeting of 11 September, under Kossuth's leadership, adopted revolutionary decisions on finance and the military to defend the invaded homeland. Another attempt by Batthyány to form a cabinet failed, and Kossuth declared that until another government was appointed, he would retain his position as finance minister.

According to legend, it was in this year that Kossuth was attacked by the country's most famous betyár

The betyárs (Hungarian language, Hungarian: ''betyár'' (singular) or ''betyárok'' (plural)) were the highwayman, highwaymen of the 19th century Kingdom of Hungary. The "betyár" word is the Hungarian version of "Social Bandit".Shingo Minamiz ...

, Sándor Rózsa

Sándor Rózsa (July 10, 1813 – November 22, 1878) was a Hungarian outlaw (in Hungarian: ''betyár'') from the Great Hungarian Plain. He is the best-known Hungarian highwayman; his life inspired numerous writers, notably Zsigmond Móricz and ...

. According to the story, Kossuth was on his way to Cegléd

Cegléd (; ) is a city in Pest County, Pest county, Hungary, approximately southeast of the Hungarian capital, Budapest.

Name

The name of the town is of disputed origin. The name may be derived from the word "szeglet" (meaning "corner") due to i ...

in a horse-drawn carriage when the bandit leader attacked him, but he kept his temper and persuaded him to join the national cause and stop robbing. The story might even be true, as Kossuth granted amnesty to the criminal on 23 October, who inturn launched an independent rebel group with 150 armed horsemen. Both men inspired legends in their time that are still alive today. In popular poetry, Rózsa is seen as a Robin Hood

Robin Hood is a legendary noble outlaw, heroic outlaw originally depicted in English folklore and subsequently featured in literature, theatre, and cinema. According to legend, he was a highly skilled archer and swordsman. In some versions o ...

-like character, while Kossuth was the personification of the nation. Also, the Serbs referred to him as King Kossuth, whose carriage was said to be drawn by 600 horses.

Regent-President of Hungary

On 7 December 1848, the Diet of Hungary

The Diet of Hungary or originally: Parlamentum Publicum / Parlamentum Generale () was the most important political assembly in Hungary since the 12th century, which emerged to the position of the supreme legislative institution in the Kingdom ...

formally refused to acknowledge the title of the new king, Franz Joseph I, "as without the knowledge and consent of the diet no one could sit on the Hungarian throne" and called the nation to arms.King of Hungary

The King of Hungary () was the Monarchy, ruling head of state of the Kingdom of Hungary from 1000 (or 1001) to 1918. The style of title "Apostolic King of Hungary" (''Magyarország apostoli királya'') was endorsed by Pope Clement XIII in 1758 ...

. If there was no possibility to inherit the throne automatically due to the death of the predecessor king (as Ferdinand was still alive), but the monarch wanted to relinquish his throne and appoint another king before his death, technically only one legal solution remained: the Diet had the power to depose the king and elect his successor as the new King of Hungary. Due to the legal and military tensions, the Hungarian parliament did not make that decision for Franz Joseph.

This event gave to the revolt an excuse of legality. Actually, from this time until the collapse of the revolution, Lajos Kossuth (as elected regent-president) became the de facto and de jure ruler of Hungary.[

]

President of the OHB

Subsequent to 28 September, the National Defence Committee (Országos Honvédelmi Bizottmány, or OHB) assumed the reins of power, initially in a provisional capacity and then, upon a parliamentary decree issued on 8 October, in a permanent manner for wartime. Lajos Kossuth was elected president of the OHB, which operated as the de facto government.

Already on 14 September, a rapidly growing number of his supporters called in parliament for Kossuth to be given temporary dictatorial powers because of the critical and desperate war situation.

From this time he had increased amounts of power. The direction of the whole government was in his hands. Without military experience, he had to control and direct the movements of armies; he was unable to keep control over the generals or to establish that military co-operation so essential to success. Arthur Görgey

Arthur is a masculine given name of uncertain etymology. Its popularity derives from it being the name of the legendary hero King Arthur.

A common spelling variant used in many Slavic, Romance, and Germanic languages is Artur. In Spanish and Ital ...

in particular, whose great abilities Kossuth was the first to recognize, refused obedience; the two men were very different personalities. Twice Kossuth removed him from command; twice he had to restore him.

Declaration of Independence

Minority rights

Despite appealing exclusively to the Hungarian nobility

The Kingdom of Hungary held a Nobility, noble class of individuals, most of whom owned landed property, from the 11th century until the mid-20th century. Initially, a diverse body of people were described as noblemen, but from the lat ...

in his speeches, Kossuth played an important part in the shaping of the law of minority rights

Minority rights are the normal individual rights as applied to members of racial, ethnic, class, religious, linguistic or gender and sexual minorities, and also the collective rights accorded to any minority group.

Civil-rights movements oft ...

in 1849. It was the first law which recognized minority rights in Europe. It gave minorities the freedom to use their mother tongue within the local administration and courts, in schools, in community life and even within the national guard of non-Magyar councils.

However, he did not support any kind of regional administration within Hungary based on the nationality principle. Kossuth accepted some national demands of the Vlach

Vlach ( ), also Wallachian and many other variants, is a term and exonym used from the Middle Ages until the Modern Era to designate speakers of Eastern Romance languages living in Southeast Europe—south of the Danube (the Balkan peninsula) ...

(like the independence of the Vlach clergy) and the Croats, but he showed no understanding for the requests of the Slovaks

The Slovaks ( (historical Sloveni ), singular: ''Slovák'' (historical: ''Sloven'' ), feminine: ''Slovenka'' , plural: ''Slovenky'') are a West Slavic ethnic group and nation native to Slovakia who share a common ancestry, culture, history ...

. Despite his father's Slovak origin and the fact that his uncle György Kossuth was the main supporter of Slovak national movement, Kossuth considered himself Hungarian and went so far as to reject the very notion of a Slovak nation in the Kingdom of Hungary.

According to Oszkár Jászi

Oszkár Jászi (born Oszkár Jakubovits; 2 March 1875 – 13 February 1957), also known in English as Oscar Jászi, was a Hungarian social scientist, historian, and politician.

Early life

Oszkár Jászi was born in Nagykároly on March 2, 18 ...

, a huge part of the reason as to why Kossuth opposed giving large-scale autonomy

In developmental psychology and moral, political, and bioethical philosophy, autonomy is the capacity to make an informed, uncoerced decision. Autonomous organizations or institutions are independent or self-governing. Autonomy can also be ...

(such as a separate parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

) to various ethnic groups in Hungary (such as the Romanians

Romanians (, ; dated Endonym and exonym, exonym ''Vlachs'') are a Romance languages, Romance-speaking ethnic group and nation native to Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. Sharing a Culture of Romania, ...

, Slovaks, Ruthenians

A ''Ruthenian'' and ''Ruthene'' are exonyms of Latin language, Latin origin, formerly used in Eastern and Central Europe as common Ethnonym, ethnonyms for East Slavs, particularly during the late medieval and early modern periods. The Latin term ...

, and Germans

Germans (, ) are the natives or inhabitants of Germany, or sometimes more broadly any people who are of German descent or native speakers of the German language. The Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany, constitution of Germany, imple ...

) is because he was afraid that this would be the first step towards a fragmentation and break-up of Hungary.ethnic

An ethnicity or ethnic group is a group of people with shared attributes, which they collectively believe to have, and long-term endogamy. Ethnicities share attributes like language, culture, common sets of ancestry, traditions, society, re ...

or linguistic borders would actually be a viable state.

Russian intervention and failure

During all the terrible winter that followed, Kossuth overcame the reluctance of the army to march to the relief of Vienna

Vienna ( ; ; ) is the capital city, capital, List of largest cities in Austria, most populous city, and one of Federal states of Austria, nine federal states of Austria. It is Austria's primate city, with just over two million inhabitants. ...

; after the defeat at the Battle of Schwechat

The Battle of Schwechat was a battle in the Hungarian Revolution of 1848, Hungarian war of Independence of 1848-1849, fought on 30 October 1848 between the revolutionary Hungary, Hungarian Army led by Lieutenant General János Móga against the ...

, at which he was present, he sent Józef Bem

Józef Zachariasz Bem (, ; 14 March 1794 – 10 December 1850) was a Polish engineer and general, an Ottoman pasha and a national hero of Poland and Hungary, and a figure intertwined with other European patriotic movements. Like Tadeusz Kościus ...

to carry on the war in Transylvania

Transylvania ( or ; ; or ; Transylvanian Saxon dialect, Transylvanian Saxon: ''Siweberjen'') is a List of historical regions of Central Europe, historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and ...

.

At the end of the year, when the Austrians were approaching Pest, he asked for the mediation of William Henry Stiles, the American envoy. Alfred I, Prince of Windisch-Grätz

General Alfred Candidus Ferdinand, Prince of Windischgrätz (; 11 May 178721 March 1862), a member of an old Austro- Bohemian House of Windischgrätz, was a Field Marshal in the Austrian army. He is most noted for his service during the Napo ...

, however, refused all terms, and the Diet and government fled to Debrecen

Debrecen ( ; ; ; ) is Hungary's cities of Hungary, second-largest city, after Budapest, the regional centre of the Northern Great Plain Regions of Hungary, region and the seat of Hajdú-Bihar County. A city with county rights, it was the large ...

, Kossuth taking with him the Crown of St Stephen, the sacred emblem of the Hungarian nation. In November 1848, Emperor Ferdinand abdicated in favour of Franz Joseph. The new Emperor revoked all the concessions granted in March and outlawed Kossuth and the Hungarian government, set up lawfully on the basis of the April laws

The April Laws, also called March Laws, were a collection of laws legislated by Lajos Kossuth with the aim of modernizing the Kingdom of Hungary into a parliamentary democracy, nation state. The laws were passed by the Hungarian Diet in March 1 ...

.

By April 1849, when the Hungarians had won many successes, after sounding the army, he issued the celebrated Hungarian Declaration of Independence

The Hungarian Declaration of Independence declared the independence of Hungary from the Habsburg monarchy during the Hungarian Revolution of 1848. The declaration of Hungarian independence was made possible by the positive mood created by the mil ...

, in which he declared that "the House of Habsburg-Lorraine

The House of Habsburg-Lorraine () originated from the marriage in 1736 of Francis I, Holy Roman Emperor, Francis III, Duke of Lorraine and Bar, and Maria Theresa of Habsburg monarchy, Austria, later successively List of Bohemian monarchs, Queen ...

, perjured in the sight of God and man, had forfeited the Hungarian throne." It was a step characteristic of his love for extreme and dramatic action, but it added to the dissensions between him and those who wished only for autonomy under the old dynasty, and his enemies did not scruple to accuse him of aiming for kingship. The dethronement also made any compromise with the Habsburgs practically impossible.

For the time the future form of government was left undecided, and Kossuth was appointed regent-president (to satisfy both royalists and republicans). Kossuth played a key role in tying down the Hungarian army for weeks for the siege and recapture of Buda castle

Buda Castle (, ), formerly also called the Royal Palace () and the Royal Castle (, ), is the historical castle and palace complex of the King of Hungary, Hungarian kings in Budapest. First completed in 1265, the Baroque architecture, Baroque pa ...

, finally successful on 4 May 1849. The hopes of ultimate success were, however, frustrated by the intervention of Tsar Nicholas I of Russia

Nicholas I, group=pron (Russian language, Russian: Николай I Павлович; – ) was Emperor of Russia, List of rulers of Partitioned Poland#Kings of the Kingdom of Poland, King of Congress Poland, and Grand Duke of Finland from 18 ...

, who acted as the protector of ruling legitimism and as guardian against revolution; all appeals to the western powers were vain, and on 11 August Kossuth abdicated in favor of Görgey, on the ground that in the last extremity, the general alone could save the nation. Görgey capitulated at Világos (now Şiria, Romania) to the Russians, who handed over the army to the Austrians. Görgey was spared, at the insistence of the Russians. Reprisals were taken on the rest of the Hungarian army, including the execution of the 13 Martyrs of Arad

The Thirteen Martyrs of Arad () were the thirteen Hungarian rebel generals who were executed by the Austrian Empire on 6 October 1849 in the city of Arad, then part of the Kingdom of Hungary (now in Romania), after the Hungarian Revolution ( ...

. Kossuth steadfastly maintained until his death that Görgey alone was responsible for the humiliation.

Kossuth's calls for independence and cut off ties with the Habsburgs did not become British policy. Foreign Secretary Lord Palmerston

Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston (20 October 1784 – 18 October 1865), known as Lord Palmerston, was a British statesman and politician who served as prime minister of the United Kingdom from 1855 to 1858 and from 1859 to 1865. A m ...

told parliament that Britain would consider it a great misfortune to Europe if Hungary became independent. He argued that a united Austrian Empire was a European necessity and a natural ally of Britain.

During this period, Hungarian lawyer George Lichtenstein served as Kossuth's private secretary. After the revolution, Lichtenstein fled to Königsberg

Königsberg (; ; ; ; ; ; , ) is the historic Germany, German and Prussian name of the city now called Kaliningrad, Russia. The city was founded in 1255 on the site of the small Old Prussians, Old Prussian settlement ''Twangste'' by the Teuton ...

and eventually settled in Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. The city is located in southeast Scotland and is bounded to the north by the Firth of Forth and to the south by the Pentland Hills. Edinburgh ...

, where he became noted as a musician and influence on musical culture of the city.

Escape and tour of Britain and United States

Kossuth's time in power was at an end. A solitary fugitive, he crossed the Ottoman frontier. He was hospitably received by the Ottoman authorities, who were supported by the

Kossuth's time in power was at an end. A solitary fugitive, he crossed the Ottoman frontier. He was hospitably received by the Ottoman authorities, who were supported by the British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and culture ...

. The Ottomans refused to surrender him and other fugitives to Austria, notwithstanding the threats of the allied emperors. In January 1850, he was removed from Vidin

Vidin (, ) is a port city on the southern bank of the Danube in north-western Bulgaria. It is close to the borders with Romania and Serbia, and is also the administrative centre of Vidin Province, as well as of the Metropolitan of Vidin (since ...

, where he had been kept under house arrest, to Shumen

Shumen (, also Romanization of Bulgarian, romanized as ''Shoumen'' or ''Šumen'', ) is the List of cities and towns in Bulgaria, tenth-largest city in Bulgaria and the administrative and economic capital of Shumen Province.

Etymology

The city ...

, and thence to Kütahya

Kütahya (; historically, Cotyaeum or Kotyaion; Ancient Greek, Greek: Κοτύαιον) is a city in western Turkey which lies on the Porsuk River, at 969 metres above sea level. It is the seat of Kütahya Province and Kütahya District. In 19 ...

in Asia Minor

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

. There, he was joined by his children, who had been confined at Pressburg; his wife (a price had been set on her head) had joined him earlier, having escaped in disguise.

On 10 August 1851 the release of Kossuth was decided by the Sublime Porte

The Sublime Porte, also known as the Ottoman Porte or High Porte ( or ''Babıali''; ), was a synecdoche or metaphor used to refer collectively to the central government of the Ottoman Empire in Istanbul. It is particularly referred to the buildi ...

, in spite of threats by Austria and Russia. The United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature, legislative branch of the federal government of the United States. It is a Bicameralism, bicameral legislature, including a Lower house, lower body, the United States House of Representatives, ...

approved having Kossuth come there, and on 1 September 1851, he boarded the ship USS ''Mississippi'' at Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; , or ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean Sea, Aegean coast of Anatolia, Turkey. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna ...

, with his family and fifty exiled followers.

The Hungarian asked the crew of ''Mississippi'' to leave the shipboard at Gibraltar

Gibraltar ( , ) is a British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory and British overseas cities, city located at the southern tip of the Iberian Peninsula, on the Bay of Gibraltar, near the exit of the Mediterranean Sea into the A ...

. During his journey on board the American frigate Mississippi on his way to London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

, an enormous French

French may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France

** French people, a nation and ethnic group

** French cuisine, cooking traditions and practices

Arts and media

* The French (band), ...

crowd waited to welcome Kossuth at the port of Marseille

Marseille (; ; see #Name, below) is a city in southern France, the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Bouches-du-Rhône and of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur Regions of France, region. Situated in the ...

. However the French authorities did not allow the dangerous revolutionary to come ashore. At Marseille, Kossuth sought permission to travel through France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

to England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

, but Prince-President Louis Napoleon

Napoleon III (Charles-Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was President of France from 1848 to 1852 and then Emperor of the French from 1852 until his deposition in 1870. He was the first president, second emperor, and last ...

denied the request. Kossuth protested publicly, and officials saw that as a blatant disregard for the neutral position of the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

.

Great Britain

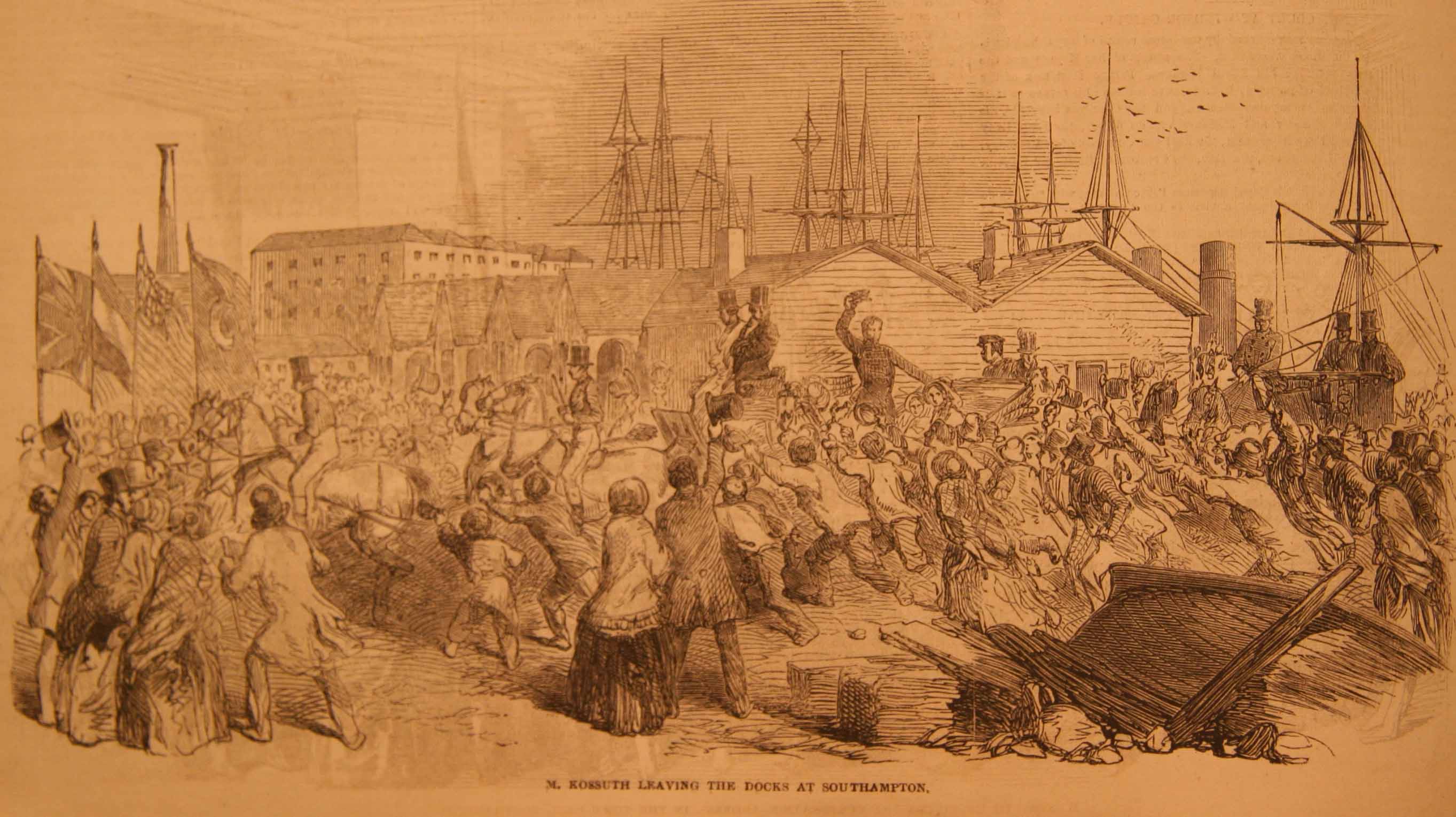

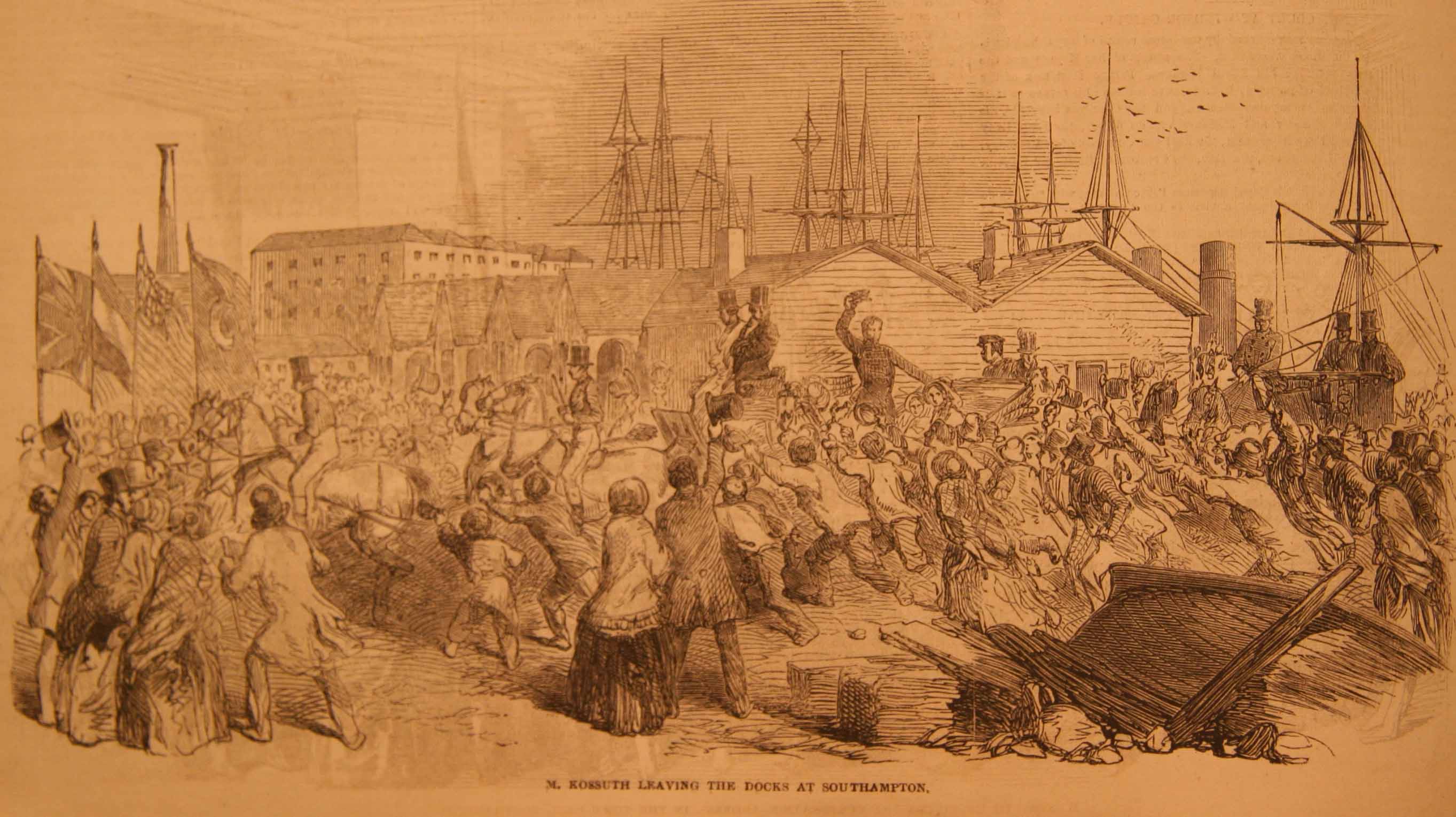

On 23 October, Kossuth landed at

On 23 October, Kossuth landed at Southampton

Southampton is a port City status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Hampshire, England. It is located approximately southwest of London, west of Portsmouth, and southeast of Salisbury. Southampton had a population of 253, ...

and spent three weeks in England, where he was generally feted. After his arrival, the press characterized the atmosphere of the streets of London as this: "It had seemed like a coronation day of Kings". Contemporary reports noticed: "Trafalgar Square was 'black with people' and Nelson's Monument peopled 'up to the fluted shaft.'"

Addresses were presented to him at Southampton, Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands (county), West Midlands, within the wider West Midlands (region), West Midlands region, in England. It is the Lis ...

and other towns; he was officially entertained by the Lord Mayor of the City of London

Lord is an appellation for a person or deity who has authority, control, or power over others, acting as a master, chief, or ruler. The appellation can also denote certain persons who hold a title of the peerage in the United Kingdom, or are ...

; at each place, he spoke eloquently in English for the Hungarian cause; and he indirectly caused Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in January 1901. Her reign of 63 year ...

to stretch the limits of her constitutional power over her Ministers to avoid embarrassment and eventually helped cause the fall of the government in power.

Having learned English during an earlier political imprisonment with the aid of a volume of Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 23 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's natio ...

, his spoken English was "wonderfully archaic" and theatrical. ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British Newspaper#Daily, daily Newspaper#National, national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its modern name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its si ...

'', generally cool towards the revolutionaries of 1848 in general and Kossuth in particular, nevertheless reported that his speeches were "clear" and that a three-hour talk was not unusual for him; and also, that if he was occasionally overcome by emotion when describing the defeat of Hungarian aspirations, "it did not at all reduce his effectiveness".

At Southampton, he was greeted by a crowd of thousands outside the Mayor's balcony, who presented him with a flag of the Hungarian Republic. The City of London Corporation

The City of London Corporation, officially and legally the Mayor and Commonalty and Citizens of the City of London, is the local authority of the City of London, the historic centre of London and the location of much of the United Kingdom's f ...

accompanied him in procession through the city, and the way to the Guildhall

A guildhall, also known as a guild hall or guild house, is a historical building originally used for tax collecting by municipalities or merchants in Europe, with many surviving today in Great Britain and the Low Countries. These buildings commo ...

was lined by thousands of cheering people. He went thereafter to Winchester

Winchester (, ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city in Hampshire, England. The city lies at the heart of the wider City of Winchester, a local government Districts of England, district, at the western end of the South Downs N ...

, Liverpool

Liverpool is a port City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. It is situated on the eastern side of the River Mersey, Mersey Estuary, near the Irish Sea, north-west of London. With a population ...

, Manchester

Manchester () is a city and the metropolitan borough of Greater Manchester, England. It had an estimated population of in . Greater Manchester is the third-most populous metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, with a population of 2.92&nbs ...

and Birmingham; at Birmingham the crowd that gathered to see him ride under the triumphal arches erected for his visit was described, even by his severest critics, as 75,000 individuals.

Many leading British politicians tried to suppress the so-called "Kossuth mania" in Britain without any success, the Kossuth mania proved to be unstoppable. When ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British Newspaper#Daily, daily Newspaper#National, national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its modern name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its si ...

'' tried to fiercely attack Kossuth, the copies of the newspaper were publicly burned in public houses, coffee houses, and in other public spaces throughout the country.

Back in London, he addressed the Trades Unions at Copenhagen Fields in Islington

Islington ( ) is an inner-city area of north London, England, within the wider London Borough of Islington. It is a mainly residential district of Inner London, extending from Islington's #Islington High Street, High Street to Highbury Fields ...

. Some twelve thousand "respectable artisans" formed a parade at Russell Square

Russell Square is a large garden square in Bloomsbury, in the London Borough of Camden, built predominantly by the firm of James Burton (property developer), James Burton. It is near the University of London's main buildings and the British Mus ...

and marched out to meet him. At the Fields themselves, the crowd was enormous; but the hostile newspaper ''The Times'' estimated it conservatively at 25,000, while the ''Morning Chronicle

''The Morning Chronicle'' was a newspaper founded in 1769 in London. It was notable for having been the first steady employer of essayist William Hazlitt as a political reporter and the first steady employer of Charles Dickens as a journalist. It ...

'' described it as 50,000, and the demonstrators themselves 100,000.

The Foreign Secretary, Lord Palmerston

Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston (20 October 1784 – 18 October 1865), known as Lord Palmerston, was a British statesman and politician who served as prime minister of the United Kingdom from 1855 to 1858 and from 1859 to 1865. A m ...

, who had already proved himself a friend of the losing sides in several of the failed revolutions of 1848, was determined to receive him at his country house, Broadlands

Broadlands is a country house located in the civil parish of Romsey Extra, near the town of Romsey in the Test Valley district of Hampshire, England. Its formal gardens and historic landscape are Grade II* listed on the Register of Histori ...

. The Cabinet had to vote to prevent it; Victoria reputedly was so incensed by the possibility of her Foreign Secretary supporting an outspoken republican that she asked the Prime Minister, Lord John Russell

John Russell, 1st Earl Russell (18 August 1792 – 28 May 1878), known as Lord John Russell before 1861, was a British Whig and Liberal statesman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1846 to 1852 and again from 1865 to 186 ...

for Palmerston's resignation, but Russell claimed that such a dismissal would be drastically unpopular at that time and over that issue. When Palmerston upped the ante by receiving at his house, instead of Kossuth, a delegation of Trade Unionists from Islington and Finsbury

Finsbury is a district of Central London, forming the southeastern part of the London Borough of Islington. It borders the City of London.

The Manorialism, Manor of Finsbury is first recorded as ''Vinisbir'' (1231) and means "manor of a man c ...

and listened sympathetically as they read an address that praised Kossuth and declared the Emperors of Austria and Russia "despots, tyrants and odious assassins", it was noted as a mark of indifference to royal displeasure. That, together with Palmerston's support of Louis Napoleon, eventually caused the Russell government to fall.

Due to Kossuth activity, the anti-Austrian sentiment became strong in Britain, when Austrian general Julius Jacob von Haynau

Julius Jakob Freiherr von Haynau (14 October 1786 – 14 March 1853) was an Austrian general who suppressed insurrectionary movements in Italy and Hungary in 1848 and later. While a hugely effective military leader, he also gained renown as an agg ...

was recognized on the street, he was attacked by British draymen on his journey in England. In 1856, Kossuth toured Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

extensively, giving lectures in major cities and small towns alike.

In addition, the indignation that he aroused against Russian

Russian(s) may refer to:

*Russians (), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*A citizen of Russia

*Russian language, the most widely spoken of the Slavic languages

*''The Russians'', a b ...

policy had much to do with the strong anti-Russian feeling, which made the Crimean War

The Crimean War was fought between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the Ottoman Empire, the Second French Empire, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and the Kingdom of Sardinia (1720–1861), Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont fro ...

possible. During the Crimean War, the activism of Kossuth also intensified in London, but since Austria did not side with Russia, there was no chance of Hungarian independence being achieved with Anglo-French military help. In the following years, Kossuth hoped that the conflicts between the great powers would allow the liberation of Hungary after all, and so he contacted the French Emperor Napoleon III. When Napoleon III and the Prime Minister of Sardinia, Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour

Camillo Paolo Filippo Giulio Benso, Count of Cavour, Isolabella and Leri (; 10 August 1810 – 6 June 1861), generally known as the Count of Cavour ( ; ) or simply Cavour, was an Italian politician, statesman, businessman, economist, and no ...

, promised to help liberate Hungary in the run-up to the Franco-Sardinian-Austrian war of 1859, Lajos Kossuth founded the Hungarian National Directorate with László Teleki and György Klapka and began to organise the Hungarian Legion. Following Napoleon III's unexpected peace with Austria after his brilliant victory at Solferino

Solferino ( Upper Mantovano: ) is a small town and municipality in the province of Mantua, Lombardy, northern Italy, approximately south of Lake Garda.

It is best known as being close to the site of the Battle of Solferino on 24 June 1859, part ...

, Kossuth sought to link the liberation of Hungary more and more clearly to the movement of the peoples fighting for their independence. However, Giuseppe Garibaldi

Giuseppe Maria Garibaldi ( , ;In his native Ligurian language, he is known as (). In his particular Niçard dialect of Ligurian, he was known as () or (). 4 July 1807 – 2 June 1882) was an Italian general, revolutionary and republican. H ...

's invasion of Sicily

Sicily (Italian language, Italian and ), officially the Sicilian Region (), is an island in the central Mediterranean Sea, south of the Italian Peninsula in continental Europe and is one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. With 4. ...

in 1860 raised new hopes. Many Hungarians fought among his Redshirts, and his successes could have led to another Italo-Austrian war. In the event, the Hungarian Legion was re-established, and Kossuth negotiated cooperation with the Italians. But the war was not fought. Although Hungary remained under Austrian rule, the decline of Habsburg power increasingly forced compromise on the Austrian government. Hungarian passive resistance and the foreign activities of the Kossuth group reinforced each other. Kossuth and the émigré movement's armed preparations and negotiations with the great powers, on the other hand, were backed by the political backdrop of a silent and passively resistant country.

United States

From Britain Kossuth went to the United States of America aboard the Humboldt postal vessel. He was warmly welcomed since the Congress in a letter inviting him to the country as the 'guest of the nation'. On 6 December 1851, this revolutionary hero arrived in

From Britain Kossuth went to the United States of America aboard the Humboldt postal vessel. He was warmly welcomed since the Congress in a letter inviting him to the country as the 'guest of the nation'. On 6 December 1851, this revolutionary hero arrived in New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

to a reception that only Washington

Washington most commonly refers to:

* George Washington (1732–1799), the first president of the United States

* Washington (state), a state in the Pacific Northwest of the United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A ...

and Lafayette had received before. The mayor of New York City introduced him as "a champion of human progress, an eloquent proclaimer of universal freedom". On the posters and in the news, he appeared as an ambassador of the European nations yearning for freedom and democracy, an implacable opponent of the tyranny embodied by the Habsburgs and the Russian Romanovs

The House of Romanov (also transliterated as Romanoff; , ) was the reigning imperial house of Russia from 1613 to 1917. They achieved prominence after Anastasia Romanovna married Ivan the Terrible, the first crowned tsar of all Russia. Nic ...

. Like the more than 600 other speeches he has given in America, it as well ended with applause.

The report of ''The Sun'' about the arrival of Kossuth in New York:

President Millard Fillmore

Millard Fillmore (January 7, 1800 – March 8, 1874) was the 13th president of the United States, serving from 1850 to 1853. He was the last president to be a member of the Whig Party while in the White House, and the last to be neither a De ...

entertained Kossuth at the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. Located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue Northwest (Washington, D.C.), NW in Washington, D.C., it has served as the residence of every U.S. president ...

on 31 December 1851 and 3 January 1852. The US Congress organized a banquet for Kossuth, which was supported by all political parties.

In early 1852, Kossuth, accompanied by his wife, his son Ferenc, and Theresa Pulszky

Theresa Pulszky (7 January 1819 – 4 September 1866), also known as Terézia Pulszky, was an Austro-Hungarian author and translator. Born in a Viennese family, she moved to Pest, Hungary after marrying her husband Ferenc Pulszky. Her experiences ...

, toured the American Midwest, South, and New England

New England is a region consisting of six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the ...

. Kossuth was the second foreigner after the Marquis de Lafayette to address a Joint Meeting of the United States Congress. He gave a speech before the Ohio General Assembly

The Ohio General Assembly is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Ohio. It consists of the 99-member Ohio House of Representatives and the 33-member Ohio Senate. Both houses of the General Assembly meet at the Ohio Statehouse in Colu ...

in February 1852 that probably influenced Lincoln

Lincoln most commonly refers to:

* Abraham Lincoln (1809–1865), the 16th president of the United States

* Lincoln, England, cathedral city and county town of Lincolnshire, England

* Lincoln, Nebraska, the capital of Nebraska, U.S.

* Lincoln (na ...

's Gettysburg Address

The Gettysburg Address is a Public speaking, speech delivered by Abraham Lincoln, the 16th President of the United States, U.S. president, following the Battle of Gettysburg during the American Civil War. The speech has come to be viewed as one ...

: "The spirit of our age is Democracy. All for the people, and all by the people. Nothing about the people without the peopleThat is Democracy!..."

Kossuth's cult spread far and wide across the continent. Even babies were named after him during his American tour. At the same time, dozens of books, hundreds of pamphlets, articles, and essays, as well as about 250 poems were written to, for, or about him in the 1850s.

Queen Victoria had a negative remark about the American version of Kossuth fever too:

"the popular Kossuth fever of the time to ignorance of the man in whom they (the Americans) see a second Washington, when the fact is that he is an ambitious and rapacious humbug."

There is no evidence that Kossuth ever met Abraham Lincoln, although Lincoln did organize a celebration in Kossuth's honor in Springfield, Illinois

Springfield is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the U.S. state of Illinois. Its population was 114,394 at the 2020 United States census, which makes it the state's List of cities in Illinois, seventh-most populous cit ...

, calling him a "most worthy and distinguished representative of the cause of civil and religious liberty on the continent of Europe". Kossuth believed that by appealing directly to European immigrants in the American heartland that he could rally them behind the cause of a free and democratic Hungary. United States officials feared that Kossuth's efforts to elicit support for a failed revolution were fraught with mischief. He would not denounce slavery

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

or stand up for the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

, and when Kossuth declared George Washington had never intended for the policy of non-interference to serve as constitutional dogma, he caused further defection. Luckily for him, it was unknown then that he entertained a proposal to raise 1,500 mercenaries, who would overthrow Haiti with officers from the United States Army, US Army and United States Navy, Navy. Ralph Waldo Emerson praised Kossuth: "You have earned your own nobility at home. We admit you ad eundem (as they say at College). We admit you to the same degree, without new trial. We suspend all rules before so paramount a merit. You may well sit a doctor in the college of liberty. You have achieved your right to interpret our Washington."

However, the issue of slavery was tearing America apart. Kossuth infuriated the Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionists by refusing to say anything offensive to the pro-slavery establishment, which, however, did not give him much support. Abolitionists said that Kossuth's "hands off" position regarding Slavery in the United States, American slavery was unacceptable. Wm. Lloyd Garrison, on behalf of the American Anti-Slavery Society, published a pamphlet "exposing the Hungarian as a self-seeking toady." Kossuth left the U.S. with only a fraction of the money he had hoped to earn on his tour.

London

Attempted leadership in exile