King Darius I on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Darius I ( ; – 486 BCE), commonly known as Darius the Great, was the third

There are different accounts of the rise of Darius to the throne from both Darius himself and Greek historians. The oldest records report a convoluted sequence of events in which Cambyses II lost his mind, had his brother

There are different accounts of the rise of Darius to the throne from both Darius himself and Greek historians. The oldest records report a convoluted sequence of events in which Cambyses II lost his mind, had his brother

Following his coronation at

Following his coronation at

In 516 BCE, Darius embarked on a campaign to Central Asia,

In 516 BCE, Darius embarked on a campaign to Central Asia,

Darius's European expedition was a major event in his reign, which began with the invasion of

Darius's European expedition was a major event in his reign, which began with the invasion of

"A companion to Ancient Macedonia"

John Wiley & Sons, 2011. pp. 135–138, 343 He then left

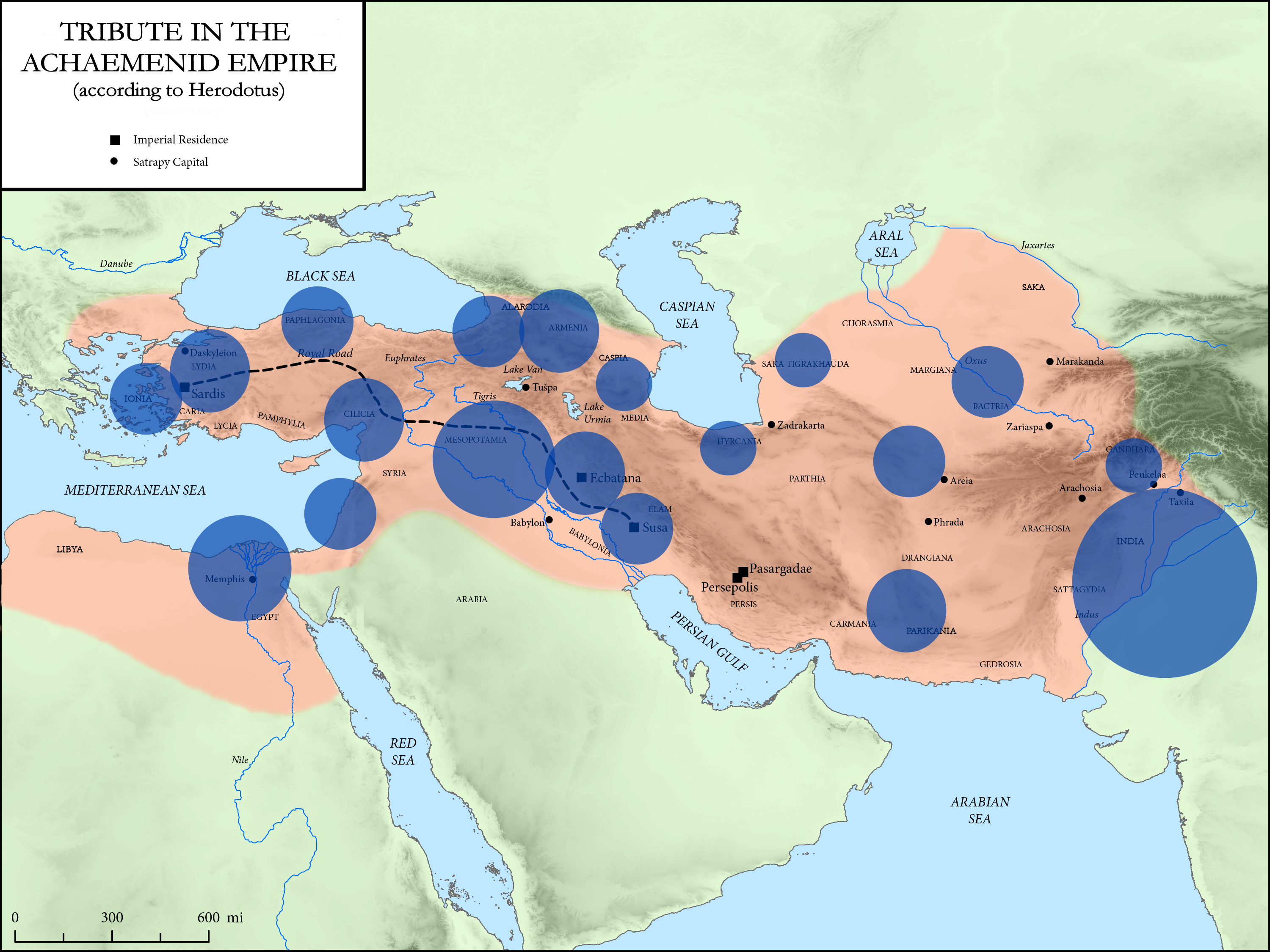

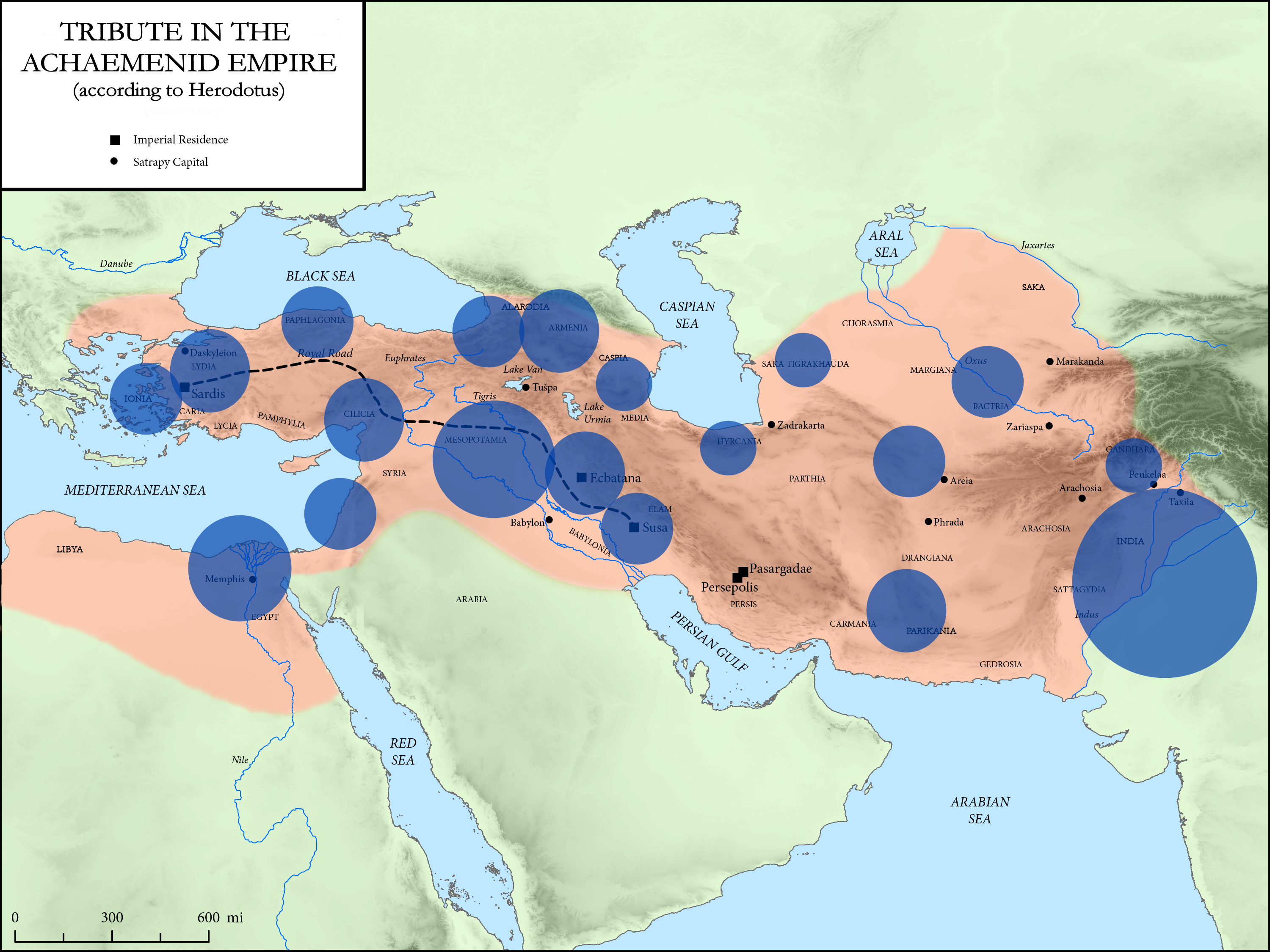

Early in his reign, Darius wanted to reorganize the structure of the empire and reform the system of taxation he inherited from Cyrus and Cambyses. To do this, Darius created twenty provinces called

Early in his reign, Darius wanted to reorganize the structure of the empire and reform the system of taxation he inherited from Cyrus and Cambyses. To do this, Darius created twenty provinces called

File:National Meusem Darafsh 6 (42).JPG, Egyptian statue of Darius I, as Pharaoh of the

King of Kings

King of Kings, ''Mepet mepe''; , group="n" was a ruling title employed primarily by monarchs based in the Middle East and the Indian subcontinent. Commonly associated with History of Iran, Iran (historically known as name of Iran, Persia ...

of the Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire, also known as the Persian Empire or First Persian Empire (; , , ), was an Iranian peoples, Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great of the Achaemenid dynasty in 550 BC. Based in modern-day Iran, i ...

, reigning from 522 BCE until his death in 486 BCE. He ruled the empire at its territorial peak, when it included much of West Asia

West Asia (also called Western Asia or Southwest Asia) is the westernmost region of Asia. As defined by most academics, UN bodies and other institutions, the subregion consists of Anatolia, the Arabian Peninsula, Iran, Mesopotamia, the Armenian ...

, parts of the Balkans

The Balkans ( , ), corresponding partially with the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throug ...

(Thrace

Thrace (, ; ; ; ) is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe roughly corresponding to the province of Thrace in the Roman Empire. Bounded by the Balkan Mountains to the north, the Aegean Sea to the south, and the Black Se ...

–Macedonia

Macedonia (, , , ), most commonly refers to:

* North Macedonia, a country in southeastern Europe, known until 2019 as the Republic of Macedonia

* Macedonia (ancient kingdom), a kingdom in Greek antiquity

* Macedonia (Greece), a former administr ...

and Paeonia) and the Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region spanning Eastern Europe and Western Asia. It is situated between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, comprising parts of Southern Russia, Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan. The Caucasus Mountains, i ...

, most of the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal sea, marginal Mediterranean sea (oceanography), mediterranean sea lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bound ...

's coastal regions, Central Asia

Central Asia is a region of Asia consisting of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. The countries as a group are also colloquially referred to as the "-stans" as all have names ending with the Persian language, Pers ...

, the Indus Valley

The Indus ( ) is a transboundary river of Asia and a trans- Himalayan river of South and Central Asia. The river rises in mountain springs northeast of Mount Kailash in the Western Tibet region of China, flows northwest through the disp ...

in the far east, and portions of North Africa

North Africa (sometimes Northern Africa) is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region. However, it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of t ...

and Northeast Africa

Northeast Africa, or Northeastern Africa, or Northern East Africa as it was known in the past, encompasses the countries of Africa situated in and around the Red Sea. The region is intermediate between North Africa and East Africa, and encompasses ...

including Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

(), eastern Libya

Libya, officially the State of Libya, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to Egypt–Libya border, the east, Sudan to Libya–Sudan border, the southeast, Chad to Chad–L ...

, and coastal Sudan

Sudan, officially the Republic of the Sudan, is a country in Northeast Africa. It borders the Central African Republic to the southwest, Chad to the west, Libya to the northwest, Egypt to the north, the Red Sea to the east, Eritrea and Ethiopi ...

.

Darius ascended the throne by overthrowing the Achaemenid monarch Bardiya

Bardiya or Smerdis ( ; ; possibly died 522 BCE), also named as Tanyoxarces (; ) by Ctesias, was a son of Cyrus the Great and the younger brother of Cambyses II, both Persian kings. There are sharply divided views on his life. Bardiya eithe ...

(or ''Smerdis''), who he claimed was in fact an imposter named Gaumata

Bardiya or Smerdis ( ; ; possibly died 522 BCE), also named as Tanyoxarces (; ) by Ctesias, was a son of Cyrus the Great and the younger brother of Cambyses II, both Persian kings. There are sharply divided views on his life. Bardiya either ...

. The new king met with rebellions throughout the empire but quelled each of them; a major event in Darius's life was his expedition to subjugate Greece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

and punish Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

and Eretria

Eretria (; , , , , literally 'city of the rowers') is a town in Euboea, Greece, facing the coast of Attica across the narrow South Euboean Gulf. It was an important Greek polis in the 6th and 5th century BC, mentioned by many famous writers ...

for their participation in the Ionian Revolt

The Ionian Revolt, and associated revolts in Aeolis, Doris (Asia Minor), Doris, Ancient history of Cyprus, Cyprus and Caria, were military rebellions by several Greek regions of Asia Minor against Achaemenid Empire, Persian rule, lasting from 499 ...

. Although his campaign ultimately resulted in failure at the Battle of Marathon

The Battle of Marathon took place in 490 BC during the first Persian invasion of Greece. It was fought between the citizens of Athens (polis), Athens, aided by Plataea, and a Achaemenid Empire, Persian force commanded by Datis and Artaph ...

, he succeeded in the re-subjugation of Thrace

Thrace (, ; ; ; ) is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe roughly corresponding to the province of Thrace in the Roman Empire. Bounded by the Balkan Mountains to the north, the Aegean Sea to the south, and the Black Se ...

and expanded the Achaemenid Empire through his conquests of Macedonia

Macedonia (, , , ), most commonly refers to:

* North Macedonia, a country in southeastern Europe, known until 2019 as the Republic of Macedonia

* Macedonia (ancient kingdom), a kingdom in Greek antiquity

* Macedonia (Greece), a former administr ...

, the Cyclades

The CYCLADES computer network () was a French research network created in the early 1970s. It was one of the pioneering networks experimenting with the concept of packet switching and, unlike the ARPANET, was explicitly designed to facilitate i ...

, and the island of Naxos

Naxos (; , ) is a Greek island belonging to the Cyclades island group. It is the largest island in the group. It was an important centre during the Bronze Age Cycladic Culture and in the Ancient Greek Archaic Period. The island is famous as ...

.

Darius organized the empire by dividing it into administrative provinces, each governed by a satrap

A satrap () was a governor of the provinces of the ancient Median kingdom, Median and Achaemenid Empire, Persian (Achaemenid) Empires and in several of their successors, such as in the Sasanian Empire and the Hellenistic period, Hellenistic empi ...

. He organized Achaemenid coinage

The Achaemenid Empire issued coins from 520 BC–450 BC to 330 BC. The Persian daric was the first gold coin which, along with a similar silver coin, the siglos (from , , '' shékel'') represented the first bimetallic monetary standard.Michael A ...

as a new uniform monetary system, and he made Aramaic

Aramaic (; ) is a Northwest Semitic language that originated in the ancient region of Syria and quickly spread to Mesopotamia, the southern Levant, Sinai, southeastern Anatolia, and Eastern Arabia, where it has been continually written a ...

a co-official language of the empire alongside Persian

Persian may refer to:

* People and things from Iran, historically called ''Persia'' in the English language

** Persians, the majority ethnic group in Iran, not to be conflated with the Iranic peoples

** Persian language, an Iranian language of the ...

. He also put the empire in better standing by building roads and introducing standard weights and measures

A unit of measurement, or unit of measure, is a definite magnitude (mathematics), magnitude of a quantity, defined and adopted by convention or by law, that is used as a standard for measurement of the same kind of quantity. Any other qua ...

. Through these changes, the Achaemenid Empire became centralized and unified. Darius undertook other construction projects throughout his realm, primarily focusing on Susa

Susa ( ) was an ancient city in the lower Zagros Mountains about east of the Tigris, between the Karkheh River, Karkheh and Dez River, Dez Rivers in Iran. One of the most important cities of the Ancient Near East, Susa served as the capital o ...

, Pasargadae

Pasargadae (; ) was the capital of the Achaemenid Empire under Cyrus the Great (559–530 BC), located just north of the town of Madar-e-Soleyman and about to the northeast of the city of Shiraz. It is one of Iran's UNESCO World Heritage Site ...

, Persepolis

Persepolis (; ; ) was the ceremonial capital of the Achaemenid Empire (). It is situated in the plains of Marvdasht, encircled by the southern Zagros mountains, Fars province of Iran. It is one of the key Iranian cultural heritage sites and ...

, Babylon

Babylon ( ) was an ancient city located on the lower Euphrates river in southern Mesopotamia, within modern-day Hillah, Iraq, about south of modern-day Baghdad. Babylon functioned as the main cultural and political centre of the Akkadian-s ...

, and Egypt. He had an inscription

Epigraphy () is the study of inscriptions, or epigraphs, as writing; it is the science of identifying graphemes, clarifying their meanings, classifying their uses according to dates and cultural contexts, and drawing conclusions about the wr ...

carved upon a cliff-face of Mount Behistun

Mount Bisotoun (or Behistun and Bisotun) is a mountain of the Zagros Mountains range, located in Kermanshah Province, western Iran. It is located west of Tehran.

Cultural history

Mount Bisotoun, aka ''Bīsitūn'' (referring to the mountain a ...

to record his conquests, which would later become important evidence of the Old Persian language.

Etymology

and are theLatin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

forms of the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

(), itself from Old Persian

Old Persian is one of two directly attested Old Iranian languages (the other being Avestan) and is the ancestor of Middle Persian (the language of the Sasanian Empire). Like other Old Iranian languages, it was known to its native speakers as (I ...

(, ; which is a shortened form of ''Dārayavaʰuš'' (, ). The longer Persian form is reflected in the Elamite

Elamite, also known as Hatamtite and formerly as Scythic, Median, Amardian, Anshanian and Susian, is an extinct language that was spoken by the ancient Elamites. It was recorded in what is now southwestern Iran from 2600 BC to 330 BC. Elamite i ...

, Babylonian , and Aramaic

Aramaic (; ) is a Northwest Semitic language that originated in the ancient region of Syria and quickly spread to Mesopotamia, the southern Levant, Sinai, southeastern Anatolia, and Eastern Arabia, where it has been continually written a ...

() forms, and possibly in the longer Greek form, (). The name in nominative form means "he who holds firm the good(ness)", which can be seen by the first part , meaning "holder", and the adverb , meaning "goodness".

Primary sources

At some time between hiscoronation

A coronation ceremony marks the formal investiture of a monarch with regal power using a crown. In addition to the crowning, this ceremony may include the presentation of other items of regalia, and other rituals such as the taking of special v ...

and his death, Darius left a tri-lingual monumental relief

Relief is a sculpture, sculptural method in which the sculpted pieces remain attached to a solid background of the same material. The term ''wikt:relief, relief'' is from the Latin verb , to raise (). To create a sculpture in relief is to give ...

on Mount Behistun

Mount Bisotoun (or Behistun and Bisotun) is a mountain of the Zagros Mountains range, located in Kermanshah Province, western Iran. It is located west of Tehran.

Cultural history

Mount Bisotoun, aka ''Bīsitūn'' (referring to the mountain a ...

, which was written in Elamite

Elamite, also known as Hatamtite and formerly as Scythic, Median, Amardian, Anshanian and Susian, is an extinct language that was spoken by the ancient Elamites. It was recorded in what is now southwestern Iran from 2600 BC to 330 BC. Elamite i ...

, Old Persian

Old Persian is one of two directly attested Old Iranian languages (the other being Avestan) and is the ancestor of Middle Persian (the language of the Sasanian Empire). Like other Old Iranian languages, it was known to its native speakers as (I ...

and Babylonian. The inscription begins with a brief autobiography including his ancestry

An ancestor, also known as a forefather, fore-elder, or a forebear, is a parent or ( recursively) the parent of an antecedent (i.e., a grandparent, great-grandparent, great-great-grandparent and so forth). ''Ancestor'' is "any person from ...

and lineage. To aid the presentation of his ancestry, Darius wrote down the sequence of events that occurred after the death of Cyrus the Great

Cyrus II of Persia ( ; 530 BC), commonly known as Cyrus the Great, was the founder of the Achaemenid Empire. Achaemenid dynasty (i. The clan and dynasty) Hailing from Persis, he brought the Achaemenid dynasty to power by defeating the Media ...

. Darius mentions several times that he is the rightful king by the grace of the supreme deity Ahura Mazda

Ahura Mazda (; ; or , ),The former is the New Persian rendering of the Avestan form, while the latter derives from Middle Persian. also known as Horomazes (),, is the only creator deity and Sky deity, god of the sky in the ancient Iranian ...

. In addition, further texts and monuments from Persepolis

Persepolis (; ; ) was the ceremonial capital of the Achaemenid Empire (). It is situated in the plains of Marvdasht, encircled by the southern Zagros mountains, Fars province of Iran. It is one of the key Iranian cultural heritage sites and ...

have been found, as well as a clay tablet containing an Old Persian cuneiform

Old Persian cuneiform is a semi-alphabetic cuneiform, cuneiform script that was the primary script for Old Persian. Texts written in this cuneiform have been found in Iran (Persepolis, Susa, Hamadan, Kharg Island), Armenia, Romania (Gherla), Turk ...

of Darius from Gherla

Gherla (; ; ) is a municipality in Cluj County, Romania (in the historical region of Transylvania). It is located from Cluj-Napoca on the river Someșul Mic, and has a population of 19,873 as of 2021. Three villages are administered by the city: ...

, Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to ...

(Harmatta) and a letter from Darius to Gadates, preserved in a Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

text of the Roman period

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

. In the foundation tablets of Apadana Palace

Persepolis (; ; ) was the ceremonial capital of the Achaemenid Empire (). It is situated in the plains of Marvdasht, encircled by the southern Zagros mountains, Fars province of Iran. It is one of the key Iranian cultural heritage sites and a ...

, Darius described in Old Persian cuneiform

Old Persian cuneiform is a semi-alphabetic cuneiform, cuneiform script that was the primary script for Old Persian. Texts written in this cuneiform have been found in Iran (Persepolis, Susa, Hamadan, Kharg Island), Armenia, Romania (Gherla), Turk ...

the extent of his Empire in broad geographical terms:

Herodotus

Herodotus (; BC) was a Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus (now Bodrum, Turkey), under Persian control in the 5th century BC, and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria, Italy. He wrote the '' Histori ...

, a Greek historian and author of '' The Histories'', provided an account of many Persian

Persian may refer to:

* People and things from Iran, historically called ''Persia'' in the English language

** Persians, the majority ethnic group in Iran, not to be conflated with the Iranic peoples

** Persian language, an Iranian language of the ...

kings and the Greco-Persian Wars

The Greco-Persian Wars (also often called the Persian Wars) were a series of conflicts between the Achaemenid Empire and Polis, Greek city-states that started in 499 BC and lasted until 449 BC. The collision between the fractious political world ...

. He wrote extensively on Darius, spanning half of Book 3 along with Books 4, 5 and 6. It begins with the removal of the alleged usurper

A usurper is an illegitimate or controversial claimant to power, often but not always in a monarchy. In other words, one who takes the power of a country, city, or established region for oneself, without any formal or legal right to claim it a ...

Gaumata

Bardiya or Smerdis ( ; ; possibly died 522 BCE), also named as Tanyoxarces (; ) by Ctesias, was a son of Cyrus the Great and the younger brother of Cambyses II, both Persian kings. There are sharply divided views on his life. Bardiya either ...

and continues to the end of Darius's reign.

Early life

Darius was the eldest of five sons to Hystaspes. The identity of his mother is uncertain. According to the modern historianAlireza Shapour Shahbazi

Alireza Shapour Shahbazi (4 September 1942 Shiraz - 15 July 2006 Walla Walla, Washington) () was a prominent Persian archaeologist, Iranologist and a world expert on Achaemenid archaeology. Shahbazi got a BA degree in and an MA degree in East As ...

(1994), Darius's mother was thought to have been a woman named Rhodogune. However, according to Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones (2013), recently uncovered texts in Persepolis indicate that his mother was Irdabama, an affluent landowner descended from a family of local Elamite rulers. Richard Stoneman likewise refers to Irdabama as the mother of Darius. The Behistun Inscription

The Behistun Inscription (also Bisotun, Bisitun or Bisutun; , Old Persian: Bagastana, meaning "the place of god") is a multilingual Achaemenid royal inscriptions, Achaemenid royal inscription and large rock relief on a cliff at Mount Behistun i ...

of Darius states that his father was satrap

A satrap () was a governor of the provinces of the ancient Median kingdom, Median and Achaemenid Empire, Persian (Achaemenid) Empires and in several of their successors, such as in the Sasanian Empire and the Hellenistic period, Hellenistic empi ...

of Bactria

Bactria (; Bactrian language, Bactrian: , ), or Bactriana, was an ancient Iranian peoples, Iranian civilization in Central Asia based in the area south of the Oxus River (modern Amu Darya) and north of the mountains of the Hindu Kush, an area ...

in 522 BCE. According to Herodotus (III.139), Darius, prior to seizing power and "of no consequence at the time", had served as a spearman (''doryphoros'') in the Egyptian campaign (528–525 BCE) of Cambyses II

Cambyses II () was the second King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, reigning 530 to 522 BCE. He was the son of and successor to Cyrus the Great (); his mother was Cassandane. His relatively brief reign was marked by his conquests in North Afric ...

, then the Persian Great King; this is often interpreted to mean he was the king's personal spear-carrier, an important role. Hystaspes was an officer in Cyrus

Cyrus () is a Persian-language masculine given name. It is historically best known as the name of several List of monarchs of Iran, Persian kings, most notably including Cyrus the Great, who founded the Achaemenid Empire in 550 BC. It remains wid ...

's army and a noble of his court.

Before Cyrus and his army crossed the river Araxes to battle with the Armenians, he installed his son Cambyses II

Cambyses II () was the second King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, reigning 530 to 522 BCE. He was the son of and successor to Cyrus the Great (); his mother was Cassandane. His relatively brief reign was marked by his conquests in North Afric ...

as king in case he should not return from battle. However, once Cyrus had crossed the Aras River, he had a vision in which Darius had wings atop his shoulders and stood upon the confines of Europe and Asia (the known world). When Cyrus awoke from the dream, he inferred it as a great danger to the future security of the empire, as it meant that Darius would one day rule the whole world. However, his son Cambyses was the heir to the throne, not Darius, causing Cyrus to wonder if Darius was forming treasonable and ambitious designs. This led Cyrus to order Hystaspes to go back to Persis

Persis (, ''Persís;'' Old Persian: 𐎱𐎠𐎼𐎿, ''Parsa''), also called Persia proper, is a historic region in southwestern Iran, roughly corresponding with Fars province. The Persian ethnic group are thought to have initially migrated ...

and watch over his son strictly, until Cyrus himself returned.

Accession

There are different accounts of the rise of Darius to the throne from both Darius himself and Greek historians. The oldest records report a convoluted sequence of events in which Cambyses II lost his mind, had his brother

There are different accounts of the rise of Darius to the throne from both Darius himself and Greek historians. The oldest records report a convoluted sequence of events in which Cambyses II lost his mind, had his brother Bardiya

Bardiya or Smerdis ( ; ; possibly died 522 BCE), also named as Tanyoxarces (; ) by Ctesias, was a son of Cyrus the Great and the younger brother of Cambyses II, both Persian kings. There are sharply divided views on his life. Bardiya eithe ...

murdered, and died from an infected leg wound. After this, Darius and a group of six nobles travelled to Sikayauvati to kill an usurper, Gaumata

Bardiya or Smerdis ( ; ; possibly died 522 BCE), also named as Tanyoxarces (; ) by Ctesias, was a son of Cyrus the Great and the younger brother of Cambyses II, both Persian kings. There are sharply divided views on his life. Bardiya either ...

, who had taken the throne by pretending to be Bardiya during the true king's absence.

Darius's account, written at the Behistun Inscription, states that Cambyses II killed his own brother Bardiya, but that this murder was not known among the Iranian people. A would-be usurper

A usurper is an illegitimate or controversial claimant to power, often but not always in a monarchy. In other words, one who takes the power of a country, city, or established region for oneself, without any formal or legal right to claim it a ...

named Gaumata came and lied to the people, stating that he was Bardiya. The Iranians had grown rebellious against Cambyses's rule and, on 11 March 522 BCE, a revolt against Cambyses broke out in his absence. On 1 July, the Iranian people chose to be under the leadership of Gaumata, as "Bardiya". No member of the Achaemenid family would rise against Gaumata for the safety of their own life. Darius, who had served Cambyses as his lance-bearer until the deposed ruler's death, prayed for aid and, in September 522 BCE, along with Otanes

Otanes (Old Persian: ''Utāna'', ) is a name given to several figures that appear in the ''Histories'' of Herodotus. One or more of these figures may be the same person.

In the ''Histories'' Otanes, son of Pharnaspes

He was regarded as a Per ...

, Intaphrenes

Intaphrenes (, ) (died c.520BCE) was one of the seven who in September 522 BCE helped Darius I usurp the throne from Bardiya, following Bardiya’s alleged usurping of the throne of the Achaemenid Empire from Cambyses II.Herodotus III, 70 Intaphre ...

, Gobryas Gobryas (; g-u-b-ru-u-v, reads as ''Gaub(a)ruva''?; Elamite: ''Kambarma'') was a common name of several Persian noblemen:

* Gobryas (general), a Cyrus II general who helped in the conquering of Babylon

* Gobryas (father of Mardonius), father of ...

, Hydarnes

Hydarnes (), also known as Hydarnes the Elder, was a Persian nobleman, who was one of the seven conspirators who overthrew the Pseudo-Smerdis. His name is the Greek transliteration of the Old Persian name , which may have meant "he who knows the ...

, Megabyzus

Megabyzus (, a folk-etymological alteration of Old Persian Bagabuxša, meaning "God saved") was an Achaemenid Persian general, son of Zopyrus, satrap of Babylonia, and grandson of Megabyzus I, one of the seven conspirators who had put Darius ...

and Aspathines

Aspathines ( ; ) (born and died sometime between 550 BC and 450BC) was a senior official under Darius the Great and Xerxes I of Persia.

Aspathines is illustrated on the tomb of Darius I at Naqsh-e Rostam, with a dedication:

The only other cou ...

, killed Gaumata in the fortress of Sikayauvati.

Herodotus provides a dubious account of Darius's ascension: Several days after Gaumata had been assassinated, Darius and the other six nobles discussed the fate of the empire. At first, the seven discussed the form of government: A democratic republic

A democratic republic is a form of government operating on principles adopted from a republic and a democracy. As a cross between two similar systems, democratic republics may function on principles shared by both republics and democracies.

Whil ...

(''Isonomia

''Isonomia'' (ἰσονομία "equality of political rights,"Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English LexiconThe Athenian Democracy in the Age of Demosthenes", Mogens Herman Hansen, , p. 81-84 from the Greek ἴσος ''isos'' ...

'') was strongly pushed by Otanes

Otanes (Old Persian: ''Utāna'', ) is a name given to several figures that appear in the ''Histories'' of Herodotus. One or more of these figures may be the same person.

In the ''Histories'' Otanes, son of Pharnaspes

He was regarded as a Per ...

, an oligarchy

Oligarchy (; ) is a form of government in which power rests with a small number of people. Members of this group, called oligarchs, generally hold usually hard, but sometimes soft power through nobility, fame, wealth, or education; or t ...

was pushed by Megabyzus, while Darius pushed for a monarchy. After stating that a republic would lead to corruption and internal fighting, while a monarchy would be led with a single-mindedness not possible in other governments, Darius was able to convince the other nobles.

To decide who would become the monarch, six of them decided on a test, with Otanes abstaining, as he had no interest in being king. They were to gather outside the palace, mounted on their horses at sunrise, and the man whose horse neighed first in recognition of the rising sun would become king. According to Herodotus, Darius had a slave, Oebares, who rubbed his hand over the genitals of a mare that Darius's horse favoured. When the six gathered, Oebares placed his hands beside the nostrils of Darius's horse, who became excited at the scent and neighed. This was followed by lightning and thunder, leading the others to dismount and kneel before Darius in recognition of his apparent divine providence

In theology, divine providence, or simply providence, is God's intervention in the universe. The term ''Divine Providence'' (usually capitalized) is also used as a names of God, title of God. A distinction is usually made between "general prov ...

. In this account, Darius himself claimed that he achieved the throne not through fraud, but cunning, even erecting a statue of himself mounted on his neighing horse with the inscription: "Darius, son of Hystaspes, obtained the sovereignty of Persia by the sagacity of his horse and the ingenious contrivance of Oebares, his groom."

According to the accounts of Greek historians, Cambyses II had left Patizeithes

Patizeithes () was a Persian magus (priest) who flourished in the second half of the 6th century BC. According to Herodotus, he persuaded his brother Smerdis (Gaumata) in 521 BC to rebel against Cambyses II (530–522 BC), who at the time ruled a ...

in charge of the kingdom when he headed for Egypt. He later sent Prexaspes

Prexaspes () was a prominent Persian during the reign of Cambyses II (530–522 BC), the second King of Kings of the Achaemenid Persian Empire. According to Herodotus, when Cambyses ordered his trusted counselor Prexaspes to kill Bardiya (also kno ...

to murder Bardiya. After the killing, Patizeithes put his brother Gaumata, a Magian

Magi (), or magus (), is the term for priests in Zoroastrianism and earlier Iranian religions. The earliest known use of the word ''magi'' is in the trilingual inscription written by Darius the Great, known as the Behistun Inscription. Old Per ...

who resembled Bardiya, on the throne and declared him the Great King. Otanes discovered that Gaumata was an impostor, and along with six other Iranian nobles, including Darius, created a plan to oust the pseudo-Bardiya. After killing the impostor along with his brother Patizeithes and other Magians, Darius was crowned king the following morning.

The details regarding Darius's rise to power is generally acknowledged as forgery and was in reality used as a concealment of his overthrow and murder of Cyrus's rightful successor, Bardiya.. To legitimize his rule, Darius had a common origin fabricated between himself and Cyrus by designating Achaemenes

Achaemenes ( ; ; ) was the progenitor ( apical ancestor) of the Achaemenid dynasty of rulers of Persia.

Other than his role as an apical ancestor, nothing is known of his life or actions. It is quite possible that Achaemenes was only the mythi ...

as the eponymous founder of their dynasty. In reality, Darius was not from the same house as Cyrus and his forebears, the rulers of Anshan

Anshan ( zh, s=鞍山, p=Ānshān, l=saddle mountain) is an inland prefecture-level city in central-southeast Liaoning province, People's Republic of China, about south of the provincial capital Shenyang. As of the 2020 census, it was Liaoning' ...

.

Early reign

Early revolts

Following his coronation at

Following his coronation at Pasargadae

Pasargadae (; ) was the capital of the Achaemenid Empire under Cyrus the Great (559–530 BC), located just north of the town of Madar-e-Soleyman and about to the northeast of the city of Shiraz. It is one of Iran's UNESCO World Heritage Site ...

, Darius moved to Ecbatana

Ecbatana () was an ancient city, the capital of the Median kingdom, and the first capital in History of Iran, Iranian history. It later became the summer capital of the Achaemenid Empire, Achaemenid and Parthian Empire, Parthian empires.Nardo, Do ...

. He soon learned that support for Bardiya

Bardiya or Smerdis ( ; ; possibly died 522 BCE), also named as Tanyoxarces (; ) by Ctesias, was a son of Cyrus the Great and the younger brother of Cambyses II, both Persian kings. There are sharply divided views on his life. Bardiya eithe ...

was strong, and revolts in Elam

Elam () was an ancient civilization centered in the far west and southwest of Iran, stretching from the lowlands of what is now Khuzestan and Ilam Province as well as a small part of modern-day southern Iraq. The modern name ''Elam'' stems fr ...

and Babylonia

Babylonia (; , ) was an Ancient history, ancient Akkadian language, Akkadian-speaking state and cultural area based in the city of Babylon in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq and parts of Kuwait, Syria and Iran). It emerged as a ...

had broken out. Darius ended the Elamite revolt when the revolutionary leader Aschina was captured and executed in Susa

Susa ( ) was an ancient city in the lower Zagros Mountains about east of the Tigris, between the Karkheh River, Karkheh and Dez River, Dez Rivers in Iran. One of the most important cities of the Ancient Near East, Susa served as the capital o ...

. After three months the revolt in Babylonia had ended. While in Babylonia, Darius learned a revolution had broken out in Bactria

Bactria (; Bactrian language, Bactrian: , ), or Bactriana, was an ancient Iranian peoples, Iranian civilization in Central Asia based in the area south of the Oxus River (modern Amu Darya) and north of the mountains of the Hindu Kush, an area ...

, a satrapy

A satrap () was a governor of the provinces of the ancient Median and Persian (Achaemenid) Empires and in several of their successors, such as in the Sasanian Empire and the Hellenistic empires. A satrapy is the territory governed by a satrap.

...

which had always been in favour of Darius, and had initially sent an army of soldiers to quell revolts. Following this, revolts broke out in Persis

Persis (, ''Persís;'' Old Persian: 𐎱𐎠𐎼𐎿, ''Parsa''), also called Persia proper, is a historic region in southwestern Iran, roughly corresponding with Fars province. The Persian ethnic group are thought to have initially migrated ...

, the homeland of the Persians and Darius and then in Elam and Babylonia, followed by in Media

Media may refer to:

Communication

* Means of communication, tools and channels used to deliver information or data

** Advertising media, various media, content, buying and placement for advertising

** Interactive media, media that is inter ...

, Parthia

Parthia ( ''Parθava''; ''Parθaw''; ''Pahlaw'') is a historical region located in northeastern Greater Iran. It was conquered and subjugated by the empire of the Medes during the 7th century BC, was incorporated into the subsequent Achaemeni ...

, Assyria

Assyria (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , ''māt Aššur'') was a major ancient Mesopotamian civilization that existed as a city-state from the 21st century BC to the 14th century BC and eventually expanded into an empire from the 14th century BC t ...

, and Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

.

By 522 BCE, there were revolts against Darius in most parts of the Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire, also known as the Persian Empire or First Persian Empire (; , , ), was an Iranian peoples, Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great of the Achaemenid dynasty in 550 BC. Based in modern-day Iran, i ...

leaving the empire in turmoil. Even though Darius did not seem to have the support of the populace

Population is a set of humans or other organisms in a given region or area. Governments conduct a census to quantify the resident population size within a given jurisdiction. The term is also applied to non-human animals, microorganisms, and pl ...

, Darius had a loyal army, led by close confidants and nobles (including the six nobles who had helped him remove Gaumata). With their support, Darius was able to suppress and quell all revolts within a year. In Darius's words, he had killed a total of nine "lying kings" through the quelling of revolutions. Darius left a detailed account of these revolutions in the Behistun Inscription

The Behistun Inscription (also Bisotun, Bisitun or Bisutun; , Old Persian: Bagastana, meaning "the place of god") is a multilingual Achaemenid royal inscriptions, Achaemenid royal inscription and large rock relief on a cliff at Mount Behistun i ...

.

Elimination of Intaphernes

One of the significant events of Darius's early reign was the slaying of Intaphernes, one of the seven noblemen who had deposed the previous ruler and installed Darius as the new monarch. The seven had made an agreement that they could all visit the new king whenever they pleased, except when he was with a woman. One evening, Intaphernes went to the palace to meet Darius, but was stopped by two officers who stated that Darius was with a woman. Becoming enraged and insulted, Intaphernes drew his sword and cut off the ears and noses of the two officers. While leaving the palace, he took thebridle

A bridle is a piece of equipment used to direct a horse. As defined in the ''Oxford English Dictionary'', the "bridle" includes both the that holds a bit that goes in the mouth of a horse, and the reins that are attached to the bit. It prov ...

from his horse, and tied the two officers together.

The officers went to the king and showed him what Intaphernes had done to them. Darius began to fear for his own safety; he thought that all seven noblemen had banded together to rebel against him and that the attack against his officers was the first sign of revolt. He sent a messenger to each of the noblemen, asking them if they approved of Intaphernes's actions. They denied and disavowed any connection with Intaphernes's actions, stating that they stood by their decision to appoint Darius as King of Kings. Darius's choice to ask the noblemen indicates that he was not yet completely sure of his authority.

Taking precautions against further resistance, Darius sent soldiers to seize Intaphernes, along with his son, family members, relatives and any friends who were capable of arming themselves. Darius believed that Intaphernes was planning a rebellion, but when he was brought to the court, there was no proof of any such plan. Nonetheless, Darius killed Intaphernes's entire family, excluding his wife's brother and son. She was asked to choose between her brother and son. She chose her brother to live. Her reasoning for doing so was that she could have another husband and another son, but she would always have but one brother. Darius was impressed by her response and spared both her brother's and her son's life.

Military campaigns

Egyptian campaign

After securing his authority over theempire

An empire is a political unit made up of several territories, military outpost (military), outposts, and peoples, "usually created by conquest, and divided between a hegemony, dominant center and subordinate peripheries". The center of the ...

, Darius embarked on a campaign to Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

where he defeated the rebel forces and secured the lands that Cambyses had conquered while incorporating a large portion of Egypt into the Achaemenid Empire. According to the Bisitun inscription, the Egyptian rebellion began while Darius was in Babylon dealing with the rebellion there. It has been suggested that the inclusion of Egypt among the list of rebelling provinces in this inscription was a scribal error, and various dates are possible for an actual rebellion. Likewise, the identity of the rebel leader is not known, but it has been suggested to be Petubastis III

Seheruibre Padibastet (Ancient Egyptian: ''shrw- jb- rꜥ pꜣ-dj-bꜣstt'') better known by his Hellenised name Petubastis III (or IV, depending on the scholars) was a native ancient Egyptian ruler (ruled c. 522 – 520 BC), who revolted aga ...

.

Through another series of campaigns, Darius I would eventually reign over the territorial apex of the empire, when it stretched from parts of the Balkans

The Balkans ( , ), corresponding partially with the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throug ...

(Thrace

Thrace (, ; ; ; ) is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe roughly corresponding to the province of Thrace in the Roman Empire. Bounded by the Balkan Mountains to the north, the Aegean Sea to the south, and the Black Se ...

-Macedon

Macedonia ( ; , ), also called Macedon ( ), was an ancient kingdom on the periphery of Archaic and Classical Greece, which later became the dominant state of Hellenistic Greece. The kingdom was founded and initially ruled by the royal ...

ia, Bulgaria

Bulgaria, officially the Republic of Bulgaria, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern portion of the Balkans directly south of the Danube river and west of the Black Sea. Bulgaria is bordered by Greece and Turkey t ...

- Paeonia) in the west, to the Indus Valley

The Indus ( ) is a transboundary river of Asia and a trans- Himalayan river of South and Central Asia. The river rises in mountain springs northeast of Mount Kailash in the Western Tibet region of China, flows northwest through the disp ...

in the east.

Invasion of the Indus Valley

In 516 BCE, Darius embarked on a campaign to Central Asia,

In 516 BCE, Darius embarked on a campaign to Central Asia, Aria

In music, an aria (, ; : , ; ''arias'' in common usage; diminutive form: arietta, ; : ariette; in English simply air (music), air) is a self-contained piece for one voice, with or without instrument (music), instrumental or orchestral accompan ...

and Bactria

Bactria (; Bactrian language, Bactrian: , ), or Bactriana, was an ancient Iranian peoples, Iranian civilization in Central Asia based in the area south of the Oxus River (modern Amu Darya) and north of the mountains of the Hindu Kush, an area ...

and then marched into Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. It is bordered by Pakistan to the Durand Line, east and south, Iran to the Afghanistan–Iran borde ...

to Taxila

Taxila or Takshashila () is a city in the Pothohar region of Punjab, Pakistan. Located in the Taxila Tehsil of Rawalpindi District, it lies approximately northwest of the Islamabad–Rawalpindi metropolitan area and is just south of the ...

in modern-day Pakistan

Pakistan, officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of over 241.5 million, having the Islam by country# ...

. Darius spent the winter of 516–515 BCE in Gandhara

Gandhara () was an ancient Indo-Aryan people, Indo-Aryan civilization in present-day northwest Pakistan and northeast Afghanistan. The core of the region of Gandhara was the Peshawar valley, Peshawar (Pushkalawati) and Swat valleys extending ...

, preparing to conquer the Indus Valley

The Indus ( ) is a transboundary river of Asia and a trans- Himalayan river of South and Central Asia. The river rises in mountain springs northeast of Mount Kailash in the Western Tibet region of China, flows northwest through the disp ...

. Darius conquered the lands surrounding the Indus River in 515 BCE. Darius I controlled the Indus Valley

The Indus ( ) is a transboundary river of Asia and a trans- Himalayan river of South and Central Asia. The river rises in mountain springs northeast of Mount Kailash in the Western Tibet region of China, flows northwest through the disp ...

from Gandhara

Gandhara () was an ancient Indo-Aryan people, Indo-Aryan civilization in present-day northwest Pakistan and northeast Afghanistan. The core of the region of Gandhara was the Peshawar valley, Peshawar (Pushkalawati) and Swat valleys extending ...

to modern Karachi

Karachi is the capital city of the Administrative units of Pakistan, province of Sindh, Pakistan. It is the List of cities in Pakistan by population, largest city in Pakistan and 12th List of largest cities, largest in the world, with a popul ...

and appointed the Greek Scylax of Caryanda

Scylax of Caryanda (; ) was a Greek explorer and writer during the late 6th and early 5th centuries BCE of the Achaemenid Empire. His own writings are lost, though occasionally cited or quoted by later Greek and Roman authors. The periplus sometim ...

to explore the Indian Ocean from the mouth of the Indus

The Indus ( ) is a transboundary river of Asia and a trans- Himalayan river of South and Central Asia. The river rises in mountain springs northeast of Mount Kailash in the Western Tibet region of China, flows northwest through the dis ...

to Suez

Suez (, , , ) is a Port#Seaport, seaport city with a population of about 800,000 in north-eastern Egypt, located on the north coast of the Gulf of Suez on the Red Sea, near the southern terminus of the Suez Canal. It is the capital and largest c ...

. Darius then marched through the Bolan Pass

Bolan Pass () is a valley and a natural gateway through the Toba Kakar range in Balochistan province of Pakistan. It is situated south of Pakistan's border with Afghanistan. The pass is an stretch of the Bolan River valley from Rindli in the ...

and returned through Arachosia

Arachosia (; ), or Harauvatis ( ), was a satrapy of the Achaemenid Empire. Mainly centred around the Arghandab River, a tributary of the Helmand River, it extended as far east as the Indus River. The satrapy's Persian-language name is the et ...

and Drangiana

Drangiana or Zarangiana (, ''Drangianē''; also attested in Old Western Iranian as 𐏀𐎼𐎣, ''Zraka'' or ''Zranka'', was a historical region and administrative division of the Achaemenid Empire. This region comprises territory around Ham ...

back to Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

.

Babylonian revolt

AfterBardiya

Bardiya or Smerdis ( ; ; possibly died 522 BCE), also named as Tanyoxarces (; ) by Ctesias, was a son of Cyrus the Great and the younger brother of Cambyses II, both Persian kings. There are sharply divided views on his life. Bardiya eithe ...

was murdered, widespread revolts occurred throughout the empire, especially on the eastern side. Darius asserted his position as king by force, taking his armies throughout the empire, suppressing each revolt individually. The most notable of all these revolts was the Babylonian revolt which was led by Nebuchadnezzar III

Nebuchadnezzar III ( Babylonian cuneiform: ''Nabû-kudurri-uṣur'', meaning "Nabu, watch over my heir", Old Persian: ''Nabukudracara''), alternatively spelled Nebuchadrezzar III and also known by his original name Nidintu-Bêl (Old Persian: ''Na ...

. This revolt occurred when Otanes withdrew much of the army from Babylon

Babylon ( ) was an ancient city located on the lower Euphrates river in southern Mesopotamia, within modern-day Hillah, Iraq, about south of modern-day Baghdad. Babylon functioned as the main cultural and political centre of the Akkadian-s ...

to aid Darius in suppressing other revolts. Darius felt that the Babylonian people had taken advantage of him and deceived him, which resulted in Darius gathering a large army and marching to Babylon

Babylon ( ) was an ancient city located on the lower Euphrates river in southern Mesopotamia, within modern-day Hillah, Iraq, about south of modern-day Baghdad. Babylon functioned as the main cultural and political centre of the Akkadian-s ...

. At Babylon, Darius was met with closed gates and a series of defences to keep him and his armies out.

Darius encountered mockery and taunting from the rebels, including the famous saying "Oh yes, you will capture our city, when mules shall have foals." For a year and a half, Darius and his armies were unable to retake the city, though he attempted many tricks and strategies—even copying that which Cyrus the Great

Cyrus II of Persia ( ; 530 BC), commonly known as Cyrus the Great, was the founder of the Achaemenid Empire. Achaemenid dynasty (i. The clan and dynasty) Hailing from Persis, he brought the Achaemenid dynasty to power by defeating the Media ...

had employed when he captured Babylon. However, the situation changed in Darius's favour when, according to the story, a mule owned by Zopyrus

Zopyrus (; ) (died 484/3 BC) was a Persian nobleman mentioned in Herodotus' '' Histories''.

He was son of Megabyzus I, who helped Darius I in his ascension. According to Herodotus, when Babylon revolted against the rule of Darius I, Zopyrus ...

, a high-ranking soldier, foaled. Following this, a plan was hatched for Zopyrus to pretend to be a deserter, enter the Babylonian camp, and gain the trust of the Babylonians. The plan was successful and Darius's army eventually surrounded the city and overcame the rebels.

During this revolt, Scythian

The Scythians ( or ) or Scyths (, but note Scytho- () in composition) and sometimes also referred to as the Pontic Scythians, were an ancient Eastern Iranian equestrian nomadic people who had migrated during the 9th to 8th centuries BC fr ...

nomads took advantage of the disorder and chaos and invaded Persia. Darius first finished defeating the rebels in Elam, Assyria, and Babylon and then attacked the Scythian invaders. He pursued the invaders, who led him to a marsh; there he found no known enemies but an enigmatic Scythian tribe.

European Scythian campaign

TheScythians

The Scythians ( or ) or Scyths (, but note Scytho- () in composition) and sometimes also referred to as the Pontic Scythians, were an Ancient Iranian peoples, ancient Eastern Iranian languages, Eastern Iranian peoples, Iranian Eurasian noma ...

were a group of north Iranian nomadic tribes, speaking an Eastern Iranian language

Eastern or Easterns may refer to:

Transportation

Airlines

*China Eastern Airlines, a current Chinese airline based in Shanghai

* Eastern Air, former name of Zambia Skyways

*Eastern Air Lines, a defunct American airline that operated from 192 ...

(Scythian languages

The Scythian languages are a group of Eastern Iranic languages of the classical and late antique period (the Middle Iranic period), spoken in a vast region of Eurasia by the populations belonging to the Scythian cultures and their desce ...

) who had invaded Media

Media may refer to:

Communication

* Means of communication, tools and channels used to deliver information or data

** Advertising media, various media, content, buying and placement for advertising

** Interactive media, media that is inter ...

, killed Cyrus

Cyrus () is a Persian-language masculine given name. It is historically best known as the name of several List of monarchs of Iran, Persian kings, most notably including Cyrus the Great, who founded the Achaemenid Empire in 550 BC. It remains wid ...

in battle, revolted against Darius and threatened to disrupt trade between Central Asia and the shores of the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal sea, marginal Mediterranean sea (oceanography), mediterranean sea lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bound ...

as they lived between the Danube

The Danube ( ; see also #Names and etymology, other names) is the List of rivers of Europe#Longest rivers, second-longest river in Europe, after the Volga in Russia. It flows through Central and Southeastern Europe, from the Black Forest sou ...

River, River Don

Don, don or DON and variants may refer to:

Places

*Don (river), a river in European Russia

*Don River (disambiguation), several other rivers with the name

* Don, Benin, a town in Benin

* Don, Dang, a village and hill station in Dang district, Gu ...

and the Black Sea.

Darius crossed the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal sea, marginal Mediterranean sea (oceanography), mediterranean sea lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bound ...

at the Bosphorus

The Bosporus or Bosphorus Strait ( ; , colloquially ) is a natural strait and an internationally significant waterway located in Istanbul, Turkey. The Bosporus connects the Black Sea to the Sea of Marmara and forms one of the continental bo ...

Straits using a bridge of boats. Darius conquered large portions of Eastern Europe, even crossing the Danube

The Danube ( ; see also #Names and etymology, other names) is the List of rivers of Europe#Longest rivers, second-longest river in Europe, after the Volga in Russia. It flows through Central and Southeastern Europe, from the Black Forest sou ...

to wage war on the Scythians

The Scythians ( or ) or Scyths (, but note Scytho- () in composition) and sometimes also referred to as the Pontic Scythians, were an Ancient Iranian peoples, ancient Eastern Iranian languages, Eastern Iranian peoples, Iranian Eurasian noma ...

. Darius invaded European Scythia

Scythia (, ) or Scythica (, ) was a geographic region defined in the ancient Graeco-Roman world that encompassed the Pontic steppe. It was inhabited by Scythians, an ancient Eastern Iranian equestrian nomadic people.

Etymology

The names ...

in 513 BCE, where the Scythians evaded Darius's army, using feints and retreating eastwards while laying waste to the countryside, by blocking wells, intercepting convoys, destroying pastures and continuous skirmishes against Darius's army. Seeking to fight with the Scythians, Darius's army chased the Scythian army deep into Scythian lands, where there were no cities to conquer and no supplies to forage. In frustration Darius sent a letter to the Scythian ruler Idanthyrsus

Idanthyrsus (; ) is the name of a Scythian king who lived in the 6th century BCE, when he faced an invasion of his country by the Persian Achaemenid Empire.

Name and etymology

The name () is the Hellenized form of a Scythian name whose origina ...

to fight or surrender. The ruler replied that he would not stand and fight with Darius until they found the graves of their fathers and tried to destroy them. Until then, they would continue their strategy as they had no cities or cultivated lands to lose.

Despite the evading tactics of the Scythians, Darius's campaign was so far relatively successful. As presented by Herodotus

Herodotus (; BC) was a Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus (now Bodrum, Turkey), under Persian control in the 5th century BC, and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria, Italy. He wrote the '' Histori ...

, the tactics used by the Scythians resulted in the loss of their best lands and of damage to their loyal allies. This gave Darius the initiative. As he moved eastwards in the cultivated lands of the Scythians in Eastern Europe proper, he remained resupplied by his fleet and lived to an extent off the land. While moving eastwards in the European Scythian lands, he captured the large fortified city of the Budini

The Budini () were an ancient Scythian tribe whose existence was recorded by ancient Graeco-Roman authors.

The Budini were closely related to the Androphagi and the Melanchlaeni.

Location

The Budini lived alongside the Gelonians in the valley ...

, one of the allies of the Scythians, and burnt it.

Darius eventually ordered a halt at the banks of Oarus, where he built "eight great forts, some distant from each other", no doubt as a frontier defence. In his ''Histories

Histories or, in Latin, Historiae may refer to:

* the plural of history

* ''Histories'' (Herodotus), by Herodotus

* ''The Histories'', by Timaeus

* ''The Histories'' (Polybius), by Polybius

* ''Histories'' by Gaius Sallustius Crispus (Sallust) ...

'', Herodotus

Herodotus (; BC) was a Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus (now Bodrum, Turkey), under Persian control in the 5th century BC, and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria, Italy. He wrote the '' Histori ...

states that the ruins of the forts were still standing in his day. After chasing the Scythians for a month, Darius's army was suffering losses due to fatigue, privation and sickness. Concerned about losing more of his troops, Darius halted the march at the banks of the Volga River

The Volga (, ) is the longest river in Europe and the longest endorheic basin river in the world. Situated in Russia, it flows through Central Russia to Southern Russia and into the Caspian Sea. The Volga has a length of , and a catchment ...

and headed towards Thrace

Thrace (, ; ; ; ) is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe roughly corresponding to the province of Thrace in the Roman Empire. Bounded by the Balkan Mountains to the north, the Aegean Sea to the south, and the Black Se ...

. He had conquered enough Scythian territory to force the Scythians to respect the Persian forces.

Persian invasion of Greece

Thrace

Thrace (, ; ; ; ) is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe roughly corresponding to the province of Thrace in the Roman Empire. Bounded by the Balkan Mountains to the north, the Aegean Sea to the south, and the Black Se ...

. Darius also conquered many cities of the northern Aegean, Paeonia, while Macedonia

Macedonia (, , , ), most commonly refers to:

* North Macedonia, a country in southeastern Europe, known until 2019 as the Republic of Macedonia

* Macedonia (ancient kingdom), a kingdom in Greek antiquity

* Macedonia (Greece), a former administr ...

submitted voluntarily, after the demand of earth and water

"Earth and water" (; ) is a phrase that represents the demand by the Achaemenid Empire for formal tribute from surrendered cities and nations. It appears in the writings of the Greek historian and geographer Herodotus, particularly with regard t ...

, becoming a vassal

A vassal or liege subject is a person regarded as having a mutual obligation to a lord or monarch, in the context of the feudal system in medieval Europe. While the subordinate party is called a vassal, the dominant party is called a suzerain ...

kingdom.Joseph Roisman, Ian Worthington"A companion to Ancient Macedonia"

John Wiley & Sons, 2011. pp. 135–138, 343 He then left

Megabyzus

Megabyzus (, a folk-etymological alteration of Old Persian Bagabuxša, meaning "God saved") was an Achaemenid Persian general, son of Zopyrus, satrap of Babylonia, and grandson of Megabyzus I, one of the seven conspirators who had put Darius ...

to conquer Thrace, returning to Sardis

Sardis ( ) or Sardes ( ; Lydian language, Lydian: , romanized: ; ; ) was an ancient city best known as the capital of the Lydian Empire. After the fall of the Lydian Empire, it became the capital of the Achaemenid Empire, Persian Lydia (satrapy) ...

to spend the winter. The Greeks living in Asia Minor

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

and some of the Greek islands had submitted to Persian rule already by 510 BCE. Nonetheless, there were certain Greeks who were pro-Persian, although these were largely based in Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

. To improve Greek-Persian relations, Darius opened his court and treasuries to those Greeks who wanted to serve him. These Greeks served as soldiers, artisans, statesmen and mariners for Darius. However, the increasing concerns among the Greeks over the strength of Darius's kingdom along with the constant interference by the Greeks in Ionia

Ionia ( ) was an ancient region encompassing the central part of the western coast of Anatolia. It consisted of the northernmost territories of the Ionian League of Greek settlements. Never a unified state, it was named after the Ionians who ...

and Lydia

Lydia (; ) was an Iron Age Monarchy, kingdom situated in western Anatolia, in modern-day Turkey. Later, it became an important province of the Achaemenid Empire and then the Roman Empire. Its capital was Sardis.

At some point before 800 BC, ...

were stepping stones towards the conflict that was yet to come between Persia and certain of the leading Greek city states.

When Aristagoras

Aristagoras of Miletus (), d. 497/496 BC, was the tyrant of the Ionian city of Miletus in the late 6th century BC and early 5th century BC. He acted as one of the instigators of the Ionian Revolt against the Persian Achaemenid Empire. He was ...

organized the Ionian Revolt

The Ionian Revolt, and associated revolts in Aeolis, Doris (Asia Minor), Doris, Ancient history of Cyprus, Cyprus and Caria, were military rebellions by several Greek regions of Asia Minor against Achaemenid Empire, Persian rule, lasting from 499 ...

, Eretria

Eretria (; , , , , literally 'city of the rowers') is a town in Euboea, Greece, facing the coast of Attica across the narrow South Euboean Gulf. It was an important Greek polis in the 6th and 5th century BC, mentioned by many famous writers ...

and Athens supported him by sending ships and troops to Ionia and by burning Sardis

Sardis ( ) or Sardes ( ; Lydian language, Lydian: , romanized: ; ; ) was an ancient city best known as the capital of the Lydian Empire. After the fall of the Lydian Empire, it became the capital of the Achaemenid Empire, Persian Lydia (satrapy) ...

. Persian military and naval operations to quell the revolt ended in the Persian reoccupation of Ionian and Greek islands, as well as the re-subjugation of Thrace and the conquering of Macedonia in 492 BCE under Mardonius. Macedon had been a vassal kingdom of the Persians since the late 6th century BCE, but retained autonomy. Mardonius's 492 campaign made it a fully subordinate part of the Persian kingdom. These military actions, coming as a direct response to the revolt in Ionia, were the beginning of the first Persian invasion of mainland Greece. At the same time, anti-Persian parties gained more power in Athens, and pro-Persian aristocrats were exiled from Athens and Sparta.

Darius responded by sending troops led by his son-in-law across the Hellespont

The Dardanelles ( ; ; ), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli (after the Gallipoli peninsula) and in classical antiquity as the Hellespont ( ; ), is a narrow, natural strait and internationally significant waterway in northwestern Turkey t ...

. However, a violent storm and harassment by the Thracians

The Thracians (; ; ) were an Indo-European languages, Indo-European speaking people who inhabited large parts of Southeast Europe in ancient history.. "The Thracians were an Indo-European people who occupied the area that today is shared betwee ...

forced the troops to return to Persia. Seeking revenge on Athens and Eretria, Darius assembled another army of 20,000 men under his Admiral, Datis

Datis or Datus (, Old Iranian: *''Dātiya''-, Achaemenid Elamite: ''Da-ti-ya'') was a Median noble and admiral who served the Persian Empire during the reign of Darius the Great (522–486 BC). He is known for his role in leading the Persian amp ...

, and his nephew Artaphernes

Artaphernes (Greek language, Greek: Ἀρταφέρνης, Old Persian language, Old Persian: Artafarna, from Median language, Median ''Rtafarnah''), was influential circa 513–492 BC and was a brother of the Achaemenid king of Persia, Darius I. ...

, who met success when they captured Eretria and advanced to Marathon. In 490 BCE, at the Battle of Marathon

The Battle of Marathon took place in 490 BC during the first Persian invasion of Greece. It was fought between the citizens of Athens (polis), Athens, aided by Plataea, and a Achaemenid Empire, Persian force commanded by Datis and Artaph ...

, the Persian army was defeated by a heavily armed Athenian army, with 9,000 men who were supported by 600 Plataea

Plataea (; , ''Plátaia'') was an ancient Greek city-state situated in Boeotia near the frontier with Attica at the foot of Mt. Cithaeron, between the mountain and the river Asopus, which divided its territory from that of Thebes. Its inhab ...

ns and 10,000 lightly armed soldiers led by Miltiades

Miltiades (; ; c. 550 – 489 BC), also known as Miltiades the Younger, was a Greek Athenian statesman known mostly for his role in the Battle of Marathon, as well as for his downfall afterwards. He was the son of Cimon Coalemos, a renowned ...

. The defeat at Marathon marked the end of the first Persian invasion of Greece. Darius began preparations for a second force which he would command, instead of his generals; however, before the preparations were complete, Darius died, thus leaving the task to his son Xerxes.

Family

Darius was the son of Hystaspes and the grandson ofArsames

Arsames ( Aršāma, modern Persian:،آرسام، آرشام Arshām, Greek: ) was the son of Ariaramnes and the grandfather of Darius I. He was traditionally claimed to have briefly been king of Persia during the Achaemenid dynasty, an ...

. Darius married Atossa

Atossa (Old Persian: ''Utauθa'', or Old Iranian: ''Hutauθa''; 550–475 BC) was an Achaemenid empress. She was the daughter of Cyrus the Great, the sister of Cambyses II, the wife of Darius the Great, the mother of Xerxes the Great and the gr ...

, daughter of Cyrus

Cyrus () is a Persian-language masculine given name. It is historically best known as the name of several List of monarchs of Iran, Persian kings, most notably including Cyrus the Great, who founded the Achaemenid Empire in 550 BC. It remains wid ...

, with whom he had four sons: Xerxes, Achaemenes

Achaemenes ( ; ; ) was the progenitor ( apical ancestor) of the Achaemenid dynasty of rulers of Persia.

Other than his role as an apical ancestor, nothing is known of his life or actions. It is quite possible that Achaemenes was only the mythi ...

, Masistes

Masistes (Old Persian 𐎶𐎰𐎡𐏁𐎫, ''Maθišta''; Greek Μασίστης, ''Masístēs''; Old Iranian *''Masišta''; died 478 BC) was a Persian prince of the Achaemenid Dynasty, son of king Darius I (reign: 520-486 BC) and of his wi ...

and Hystaspes. He also married Artystone

Artystone (; ; Elamite , ) also known as ''Irtašduna'' in the Fortification tablets, was a Achaemenid princess, daughter of king Cyrus the Great, and sister of Cambyses II, Atossa and Smerdis. Along with Atossa and her niece Parmys, Artystone ...

, another daughter of Cyrus, with whom he had two known sons, Arsames

Arsames ( Aršāma, modern Persian:،آرسام، آرشام Arshām, Greek: ) was the son of Ariaramnes and the grandfather of Darius I. He was traditionally claimed to have briefly been king of Persia during the Achaemenid dynasty, an ...

and Gobryas. Darius married Parmys

Parmys (Old Persian: ''(H)uparviyā'', Elamite: ''Uparmiya'') was a Achaemenid Empire, Persian princess, the only daughter of Bardiya (Smerdis), son of Cyrus the Great.

Once Darius the Great seized the Achaemenid thrones, he married two daughter ...

, the daughter of Bardiya, with whom he had a son, Ariomardus

Ariomardus was the name of a number of people from classical antiquity:

* A son of the Persian King Darius I and his wife Parmys.Lendering, J:Parmys, in http://www.livius.org He attended Xerxes I into Greece, being in command of the Moschi and Ti ...

. Furthermore, Darius married his niece Phratagune

Phratagune (or Phratagone) was a princess of ancient Persia, the only daughter of Artanes, who lived around the 5th century BCE.

Phratagune's father gave her in marriage to his brother, her uncle, Darius the Great. This was ostensibly because A ...

, with whom he had two sons, Abrokomas and Hyperantes. He also married another woman of the nobility, Phaidyme, the daughter of Otanes

Otanes (Old Persian: ''Utāna'', ) is a name given to several figures that appear in the ''Histories'' of Herodotus. One or more of these figures may be the same person.

In the ''Histories'' Otanes, son of Pharnaspes

He was regarded as a Per ...

. It is unknown if he had any children with her. Before these royal marriages, Darius had married an unknown daughter of his good friend and lance carrier Gobryas Gobryas (; g-u-b-ru-u-v, reads as ''Gaub(a)ruva''?; Elamite: ''Kambarma'') was a common name of several Persian noblemen:

* Gobryas (general), a Cyrus II general who helped in the conquering of Babylon

* Gobryas (father of Mardonius), father of ...

from an early marriage, with whom he had three sons, Artobazanes, Ariabignes

Ariabignes (, ) was one of the sons of the Persian king Darius I and his mother was a daughter of Gobryas (). He participated in the Second Persian invasion of Greece, as one of the four admirals of the fleet of his brother Xerxes I, and was kill ...

and Arsamenes

Arsamenes () was a prince of ancient Persia, the son of Darius the Great. We know very little about him today other than that he was, according to the historian Herodotus, the commander of the Utians (or "Utii") and Mycae people (or "Myci") in t ...

. Any daughters he had with her are not known. Although Artobazanes was Darius's first-born, Xerxes became heir and the next king through the influence of Atossa

Atossa (Old Persian: ''Utauθa'', or Old Iranian: ''Hutauθa''; 550–475 BC) was an Achaemenid empress. She was the daughter of Cyrus the Great, the sister of Cambyses II, the wife of Darius the Great, the mother of Xerxes the Great and the gr ...

; she had great authority in the kingdom as Darius loved her the most of all his wives.

Death and succession

After becoming aware of the Persian defeat at theBattle of Marathon

The Battle of Marathon took place in 490 BC during the first Persian invasion of Greece. It was fought between the citizens of Athens (polis), Athens, aided by Plataea, and a Achaemenid Empire, Persian force commanded by Datis and Artaph ...

, Darius began planning another expedition against the Greek city-states

Polis (: poleis) means 'city' in Ancient Greek. The ancient word ''polis'' had socio-political connotations not possessed by modern usage. For example, Modern Greek πόλη (polē) is located within a (''khôra''), "country", which is a πατ ...

; this time, he, not Datis

Datis or Datus (, Old Iranian: *''Dātiya''-, Achaemenid Elamite: ''Da-ti-ya'') was a Median noble and admiral who served the Persian Empire during the reign of Darius the Great (522–486 BC). He is known for his role in leading the Persian amp ...

, would command the imperial armies. Darius had spent three years preparing men and ships for war when a revolt broke out in Egypt. This revolt in Egypt worsened his failing health and prevented the possibility of his leading another army. Soon afterwards, Darius died, after thirty days of suffering through an unidentified illness, partially due to his part in crushing the revolt, at about sixty-four years old. In October 486 BCE, his body was embalmed

Embalming is the art and science of preserving human remains by treating them with embalming chemicals in modern times to forestall decomposition. This is usually done to make the deceased suitable for viewing as part of the funeral ceremony or ...

and entombed in the rock-cut tomb at Naqsh-e Rostam

Naqsh-e Rostam (; , ) is an ancient archeological site and necropolis located about 13 km northwest of Persepolis, in Fars province, Iran. A collection of ancient Iranian rock reliefs are cut into the face of the mountain and the mount ...

, which he had been preparing. An inscription on his tomb introduces him as "Great King, King of Kings, King of countries containing all kinds of men, King in this great earth far and wide, son of Hystaspes, an Achaemenian, a Persian, son of a Persian, an Aryan

''Aryan'' (), or ''Arya'' (borrowed from Sanskrit ''ārya''), Oxford English Dictionary Online 2024, s.v. ''Aryan'' (adj. & n.); ''Arya'' (n.)''.'' is a term originating from the ethno-cultural self-designation of the Indo-Iranians. It stood ...

, having Aryan lineage." A relief under his tomb portraying equestrian combat was later carved during the reign of the Sasanian

The Sasanian Empire (), officially Eranshahr ( , "Empire of the Iranians"), was an Iranian empire that was founded and ruled by the House of Sasan from 224 to 651. Enduring for over four centuries, the length of the Sasanian dynasty's reign ...

King of Kings, Bahram II

Bahram II (also spelled Wahram II or Warahran II; ) was the fifth Sasanian King of Kings (''shahanshah'') of Iran, from 274 to 293. He was the son and successor of Bahram I (). Bahram II, while still in his teens, ascended the throne with the ai ...

().

Xerxes, the eldest son of Darius and Atossa

Atossa (Old Persian: ''Utauθa'', or Old Iranian: ''Hutauθa''; 550–475 BC) was an Achaemenid empress. She was the daughter of Cyrus the Great, the sister of Cambyses II, the wife of Darius the Great, the mother of Xerxes the Great and the gr ...

, succeeded to the throne as Xerxes I

Xerxes I ( – August 465 BC), commonly known as Xerxes the Great, was a List of monarchs of Persia, Persian ruler who served as the fourth King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, reigning from 486 BC until his assassination in 465 BC. He was ...

; before his accession, he had contested the succession with his elder half-brother Artobarzanes, Darius's eldest son, who was born to his first wife before Darius rose to power. With Xerxes's accession, the empire was again ruled by a member of the house of Cyrus.

Government

Organization

Early in his reign, Darius wanted to reorganize the structure of the empire and reform the system of taxation he inherited from Cyrus and Cambyses. To do this, Darius created twenty provinces called

Early in his reign, Darius wanted to reorganize the structure of the empire and reform the system of taxation he inherited from Cyrus and Cambyses. To do this, Darius created twenty provinces called satrapies

A satrap () was a governor of the provinces of the ancient Median and Persian (Achaemenid) Empires and in several of their successors, such as in the Sasanian Empire and the Hellenistic empires. A satrapy is the territory governed by a satrap.

...

(or ''archi'') which were each assigned to a satrap