July 1927 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The following events occurred in July 1927:

The following events occurred in July 1927:

*

*

*

*

The following events occurred in July 1927:

The following events occurred in July 1927:

July 1, 1927 (Friday)

* The first coast-to-coast radio network hookup in Canada was made for the celebration of the 60th anniversary of the Dominion. * The airplane ''America'', along with CommanderRichard E. Byrd

Richard Evelyn Byrd Jr. (October 25, 1888 – March 11, 1957) was an American naval officer, and pioneering aviator, polar explorer, and organizer of polar logistics. Aircraft flights in which he served as a navigator and expedition leader cr ...

and its crew, Bert Acosta

Bertrand Blanchard Acosta (January 1, 1895 – September 1, 1954) was a record-setting aviator and test pilot. He and Clarence D. Chamberlin set an endurance record of 51 hours, 11 minutes, and 25 seconds in the air. He later flew in the Span ...

, George O. Noville

George Otto Noville (April 24, 1890 – January 1, 1963), also known as "Noville" and "Rex," was a pioneer in polar and trans-Atlantic aviation in the 1920s, and winner of the Distinguished Flying Cross (United States), Distinguished Flying C ...

and Bert Balchen, crashed into the sea as they attempted to duplicate Charles Lindbergh's flight from New York to Paris. Fortunately, the aviators were within 200 meters of the beach at Ver-sur-Mer

__NOTOC__

Ver-sur-Mer (, literally ''Ver on Sea'') is a Communes of France, commune in the Calvados (department), Calvados Departments of France, department and Normandy (administrative region), Normandy Regions of France, region of north-wester ...

when their plane ran out of fuel at 5:45 am, and they survived the ordeal.

* Born:

**Chandra Shekhar Singh

Chandra Shekhar (17 April 1927 – 8 July 2007), also known as Jananayak, was an Indian politician and the Prime Minister of India, prime minister of India, between 10 November 1990 and 21 June 1991. He headed a minority government of a breakaw ...

, Prime Minister of India

The prime minister of India (ISO 15919, ISO: ) is the head of government of the Republic of India. Executive authority is vested in the prime minister and his chosen Union Council of Ministers, Council of Ministers, despite the president of ...

in 1990 and 1991; in Ibrahimpatti, United Provinces of British India

The United Provinces of Agra and Oudh was a province of India under the British Raj, which existed from 22 March 1902 to 1937; the official name was shortened by the Government of India Act 1935 to United Provinces (UP), by which the province h ...

(d. 2007)

**Winfield Dunn

Bryant Winfield Culberson Dunn (July 1, 1927 – September 28, 2024) was an American businessman and politician who served as the 43rd governor of Tennessee from 1971 to 1975. He was the state's first Republican governor in fifty years.Phillip ...

, American politician, Governor of Tennessee from 1971 to 1975; in Meridian, Mississippi

Meridian is the List of municipalities in Mississippi, eighth most populous city in the U.S. state of Mississippi, with a population of 35,052 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. It is the county seat of Lauderdale County, Mississippi, ...

(d. 2024)

July 2, 1927 (Saturday)

* Jane Eads, reporter for the Chicago ''Herald and Examiner'' became the firstairline

An airline is a company that provides civil aviation, air transport services for traveling passengers or freight (cargo). Airlines use aircraft to supply these services and may form partnerships or Airline alliance, alliances with other airlines ...

passenger, completing a flight from Chicago to San Francisco, on a Boeing Air Transport

United Air Lines was formed in 1931 as a subsidiary of United Aircraft and Transport Corporation to manage its airlines that were originally acquired by William Boeing, including Boeing Air Transport, Pacific Air Transport, Varney Air Lines, and ...

Model 40 that was used to transport mail. The airline would later become United Airlines

United Airlines, Inc. is a Major airlines of the United States, major airline in the United States headquartered in Chicago, Chicago, Illinois that operates an extensive domestic and international route network across the United States and six ...

.

* Henri Cochet

Henri Jean Cochet (; 14 December 1901 – 1 April 1987) was a French tennis player. He was a world No. 1 ranked player, and a member of the famous " Four Musketeers" from France who dominated tennis in the late 1920s and early 1930s.

Born in ...

won the Wimbledon finals over fellow Frenchman Jean Borotra

Jean Laurent Robert Borotra (, ; 13 August 1898 – 17 July 1994) was a French tennis champion. He was one of the " Four Musketeers" from his country who dominated tennis in the late 1920s and early 1930s. Borotra was imprisoned in Itter Castle ...

after losing the first two sets, 4–6 and 4–6, then won the next two 6–3, 6–4, and took the match 7–5. The day before, Cochet had made the finals by defeating Bill Tilden

William Tatem Tilden II (February 10, 1893 – June 5, 1953), nicknamed "Big Bill", was an American tennis player. He was the world No. 1 amateur for six consecutive years, from 1920 to 1925, and was ranked as the world No. 1 professional by Ra ...

in the same come from behind fashion, losing the first 2 sets and winning the other three. Helen Wills

Helen Newington Wills (October 6, 1905 – January 1, 1998), also known by her married names Helen Wills Moody and Helen Wills Roark, was an American tennis player. She won 31 Grand Slam (tennis), Grand Slam tournament titles (singles, doubles, ...

became the first American player in 20 years to win the women's singles, beating Spanish champion Lili de Alvarez Lili may refer to:

People

* Lili (given name), for a list of people with the given name or nickname

Other uses

* ''Lili'' (1953 film), a musical starring Leslie Caron and Mel Ferrer

* Lili (Tekken), a character from the Tekken fighting game seri ...

in straight sets, 6–2, 6–4.

* Lord Norman, Governor of the Bank of England

The Bank of England is the central bank of the United Kingdom and the model on which most modern central banks have been based. Established in 1694 to act as the Kingdom of England, English Government's banker and debt manager, and still one ...

and Hjalmar Schacht

Horace Greeley Hjalmar Schacht (); 22 January 1877 – 3 June 1970) was a German economist, banker, politician, and co-founder of the German Democratic Party. He served as the Currency Commissioner and President of the Reichsbank during the ...

of the German Reichsbank

The ''Reichsbank'' (; ) was the central bank of the German Empire from 1876 until the end of Nazi Germany in 1945.

Background

The monetary institutions in Germany had been unsuited for its economic development for several decades before unifica ...

met at Long Island with U.S. Undersecretary of the Treasury Ogden L. Mills

Ogden Livingston Mills (August 23, 1884 – October 11, 1937) was an American lawyer, businessman and politician. He served as United States Secretary of the Treasury in President Herbert Hoover's cabinet, during which time Mills pushed for tax ...

to make plans to boost the American and world economies.

* Niels Bohr

Niels Henrik David Bohr (, ; ; 7 October 1885 – 18 November 1962) was a Danish theoretical physicist who made foundational contributions to understanding atomic structure and old quantum theory, quantum theory, for which he received the No ...

began working on his description of space-time in quantum and wave mechanics

* The Western film '' The Last Outlaw'' starring Gary Cooper

Gary Cooper (born Frank James Cooper; May 7, 1901May 13, 1961) was an American actor known for his strong, silent screen persona and understated acting style. He won the Academy Award for Best Actor twice and had a further three nominations, ...

was released.

July 3, 1927 (Sunday)

*

* Satchel Paige

Leroy Robert "Satchel" Paige (July 7, 1906 – June 8, 1982) was an American professional baseball pitcher who played in Negro league baseball and Major League Baseball (MLB). His career spanned five decades and culminated with his induction in ...

made his pro baseball debut in the Negro leagues

The Negro leagues were United States professional baseball leagues comprising teams of African Americans. The term may be used broadly to include professional black teams outside the leagues and it may be used narrowly for the seven relativel ...

, pitching for the Birmingham Black Barons

The Birmingham Black Barons were a Negro league baseball team that played from 1920 until 1960, including 18 seasons recognized as Major League by Major League Baseball. They shared their home field of Rickwood Field in Birmingham, Alabama, wi ...

in a game at Detroit. After twenty-one years, Paige would, at 42, become the oldest rookie in Major League Baseball

Major League Baseball (MLB) is a professional baseball league composed of 30 teams, divided equally between the National League (baseball), National League (NL) and the American League (AL), with 29 in the United States and 1 in Canada. MLB i ...

, joining the Cleveland Indians

The Cleveland Guardians are an American professional baseball team based in Cleveland. The Guardians compete in Major League Baseball (MLB) as a member club of the American League (AL) American League Central, Central Division. Since , the team ...

in 1948 after the integration of baseball. At 59, he would make his final appearance, pitching for the Kansas City A's

The Kansas City Athletics were a Major League Baseball team that played in Kansas City, Missouri, from 1955 to 1967, having previously played in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, as the Philadelphia Athletics. After moving in 1967, the team became the ...

.

* Born:

** Ken Russell

Henry Kenneth Alfred Russell (3 July 1927 – 27 November 2011) was a British film director, known for his pioneering work in television and film and for his flamboyant and controversial style. His films were mainly liberal adaptations of ...

, British film director known for ''Women in Love

''Women in Love'' is a 1920 novel by English author D. H. Lawrence. It is a sequel to his earlier novel, '' The Rainbow'' (1915), and follows the continuing loves and lives of the Brangwen sisters, Gudrun and Ursula. Gudrun Brangwen, an arti ...

'' and ''Altered States

''Altered States'' is a 1980 American science fiction horror film directed by Ken Russell, and adapted by playwright and screenwriter Paddy Chayefsky from his 1978 novel of the same name. The novel and the film are based in part on John C. Li ...

''; in Southampton

Southampton is a port City status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Hampshire, England. It is located approximately southwest of London, west of Portsmouth, and southeast of Salisbury. Southampton had a population of 253, ...

, Hampshire

Hampshire (, ; abbreviated to Hants.) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Berkshire to the north, Surrey and West Sussex to the east, the Isle of Wight across the Solent to the south, ...

(d. 2011)

** Salome Thorkelsdottir, Icelandic politician and the first woman (from 1991 to 1995) to have served as the Speaker of the House

The speaker of a deliberative assembly, especially a legislative body, is its presiding officer, or the chair. The title was first used in 1377 in England.

Usage

The title was first recorded in 1377 to describe the role of Thomas de Hung ...

in that nation's parliament, the ''Althing

The (; ), anglicised as Althingi or Althing, is the Parliamentary sovereignty, supreme Parliament, national parliament of Iceland. It is the oldest surviving parliament in the world. The Althing was founded in 930 at ('Thing (assembly), thing ...

''; in Reykjavík

Reykjavík is the Capital city, capital and largest city in Iceland. It is located in southwestern Iceland on the southern shore of Faxaflói, the Faxaflói Bay. With a latitude of 64°08′ N, the city is List of northernmost items, the worl ...

(alive in 2024)

July 4, 1927 (Monday)

*Sukarno

Sukarno (6 June 1901 – 21 June 1970) was an Indonesian statesman, orator, revolutionary, and nationalist who was the first president of Indonesia, serving from 1945 to 1967.

Sukarno was the leader of the Indonesian struggle for independenc ...

(born Kusno Sosrodihardjo) founded the Perserikatan Nasional Indonesia, seeking independence of the Dutch East Indies

The Dutch East Indies, also known as the Netherlands East Indies (; ), was a Dutch Empire, Dutch colony with territory mostly comprising the modern state of Indonesia, which Proclamation of Indonesian Independence, declared independence on 17 Au ...

colony from the Netherlands. In 1945, he would become the first President of Indonesia

The president of the Republic of Indonesia () is the head of state and head of government of the Republic of Indonesia. The president is the leader of the executive branch of the Indonesian government and the commander-in-chief of the ...

.

* The Lockheed Vega

The Lockheed Vega is an American five- to seven-seat high-wing monoplane airliner built by the Lockheed Corporation starting in 1927. It became famous for its use by a number of record-breaking pilots who were attracted to its high speed and lo ...

, first airplane manufactured by the Lockheed Corporation

The Lockheed Corporation was an American aerospace manufacturer. Lockheed was founded in 1926 and merged in 1995 with Martin Marietta to form Lockheed Martin. Its founder, Allan Lockheed, had earlier founded the similarly named but otherwise-u ...

, made its inaugural flight, with Eddie Belande taking the plane up from Mines Field in Los Angeles.

* Joseph Goebbels

Paul Joseph Goebbels (; 29 October 1897 – 1 May 1945) was a German Nazism, Nazi politician and philologist who was the ''Gauleiter'' (district leader) of Berlin, chief Propaganda in Nazi Germany, propagandist for the Nazi Party, and ...

published the first issue of the Nazi newspaper, ''Der Angriff

''Der Angriff'' (in English "The Attack") was the official newspaper of the Berlin ''Gau'' of the Nazi Party. Founded in 1927, the last edition of the newspaper was published on 24 April 1945.

History

The newspaper was set up by Joseph Goebb ...

'', which promoted Goebbels' views until its last issue in April 1945.

* Born:

** Neil Simon

Marvin Neil Simon (July 4, 1927 – August 26, 2018) was an American playwright, screenwriter and author. He wrote more than 30 plays and nearly the same number of movie screenplays, mostly film adaptations of his plays. He received three ...

, American playwright; in the Bronx, New York

The Bronx ( ) is the northernmost of the five Boroughs of New York City, boroughs of New York City, coextensive with Bronx County, in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York. It shares a land border with Westchester County, New York, West ...

(d. 2018)

** Gina Lollobrigida

Luigia "Gina" Lollobrigida (4 July 1927 – 16 January 2023) was an Italian actress, model, photojournalist, and sculptor. She was one of the highest-profile European actresses of the 1950s and 1960s, a period in which she was an international ...

, Italian and American film actress; in Subiaco (d. 2023)

July 5, 1927 (Tuesday)

* The Verein fur Raumschiffahrt (VfR, or Association for Space Travel) was founded at the ''Goldenes Zepter'' tavern in Breslau, Germany, (nowWrocław

Wrocław is a city in southwestern Poland, and the capital of the Lower Silesian Voivodeship. It is the largest city and historical capital of the region of Silesia. It lies on the banks of the Oder River in the Silesian Lowlands of Central Eu ...

, Poland) by various German rocket scientists including Hermann Oberth

Hermann Julius Oberth (; 25 June 1894 – 28 December 1989) was an Austria-Hungary, Austro-Hungarian-born German physicist and rocket pioneer of Transylvanian Saxons, Transylvanian Saxon descent. Oberth supported Nazi Germany's war effort and re ...

, Walter Hohmann

Walter Hohmann (; ; 18 March 1880 – 11 March 1945) was a German engineer who made an important contribution to the understanding of orbital dynamics. In a book published in 1925, Hohmann demonstrated a fuel-efficient path to move a spacecraft ...

and Johannes Winkler

Johannes Winkler (29 May 1897 – 27 December 1947) was a German rocket pioneer who co-founded with Max Valier of Opel RAK the first German rocket society "Verein für Raumschiffahrt" and launched, after Friedrich Wilhelm Sander's successful ...

,

* Northwest Airlines

Northwest Airlines (often abbreviated as NWA) was a major airline in the United States that operated from 1926 until it Delta Air Lines–Northwest Airlines merger, merged with Delta Air Lines in 2010. The merger made Delta the largest airline ...

began passenger service when businessman Byron Webster bought a ticket to fly from Minneapolis

Minneapolis is a city in Hennepin County, Minnesota, United States, and its county seat. With a population of 429,954 as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it is the state's List of cities in Minnesota, most populous city. Locat ...

to Chicago

Chicago is the List of municipalities in Illinois, most populous city in the U.S. state of Illinois and in the Midwestern United States. With a population of 2,746,388, as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it is the List of Unite ...

. The plane took more than 12 hours to complete its journey, after stops in the Wisconsin cities of LaCrosse, Madison and Milwaukee, and Webster arrived in Chicago the next morning at 2:30. Northwest would become one of the largest airlines in the United States, before being merged into Delta Air Lines in 2010.

* The S.S. ''Presidente Saavedra'', the only ship of the Bolivian Naval Force

The Bolivian Navy () is a branch of the Armed Forces of Bolivia. As of 2018, the Bolivian Navy had approximately 5,000 personnel. Although Bolivia has been landlocked since the War of the Pacific and the Treaty of Peace and Friendship (1904), B ...

, sank in the harbor outside of Buenos Aires, Argentina.

* Inventor Stanley S. Jenkins applied for the patent for the process that he used to create the corn dog

A corn dog (also spelled corndog and also known by #Name variations, several other names) is a hot dog on a stick that has been coated in a thick layer of cornmeal Batter (cooking), batter and Deep frying, deep fried. It originated in the Unite ...

and other deep-fried

Deep frying (also referred to as deep fat frying) is a cooking method in which food is submerged in hot fat, traditionally lard but today most commonly oil, as opposed to the shallow frying used in conventional frying done in a frying pan. N ...

foods that could be carried on a stick. Under the title "Combined Dipping, Cooking, and Article Holding Apparatus", Jenkins wrote in his application that his invention was for "an apparatus in which a new and novel edible food product may be deep fried... consisting of an article of food impaled on a stick and coated with batter," and added that "I have discovered that articles of food such, for instance, as wieners, boiled ham, hard boiled eggs, cheese, sliced peaches, pineapples, bananas and like fruit, and cherries, dates, figs, strawberries, etc., when impaled on sticks and dipped in a batter... the resultant food product on a stick for a handle is a clean, wholesome and tasty refreshment." U.S. Patent No. 1,706,491 was granted on March 26, 1929.

* Born: Thomas J. Fleming, American historian and novelist; in Jersey City, New Jersey

Jersey City is the List of municipalities in New Jersey, second-most populous

(d. 2017)

* Died: Albrecht Kossel

Ludwig Karl Martin Leonhard Albrecht Kossel (; 16 September 1853 – 5 July 1927) was a biochemist and pioneer in the study of genetics. He was awarded the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1910 for his work in determining the chemical ...

, 73, German physician and 1910 Nobel Prize laureate for his determination of the chemical composition of nucleic acids

Nucleic acids are large biomolecules that are crucial in all cells and viruses. They are composed of nucleotides, which are the monomer components: a 5-carbon sugar, a phosphate group and a nitrogenous base. The two main classes of nucleic a ...

July 6, 1927 (Wednesday)

* TheChurch of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the State religion#State churches, established List of Christian denominations, Christian church in England and the Crown Dependencies. It is the mother church of the Anglicanism, Anglican Christian tradition, ...

's governing assembly voted 517–133 in favor of the proposed revision of the Book of Common Prayer

The ''Book of Common Prayer'' (BCP) is the title given to a number of related prayer books used in the Anglican Communion and by other Christianity, Christian churches historically related to Anglicanism. The Book of Common Prayer (1549), fi ...

.

* The song " My Blue Heaven" was recorded for the first time, by Paul Whiteman

Paul Samuel Whiteman (March 28, 1890 – December 29, 1967) was an American Jazz bandleader, composer, orchestral director, and violinist.

As the leader of one of the most popular dance bands in the United States during the 1920s and early 193 ...

and his Orchestra, and became one of the year's top-selling records.

* Born:

** Janet Leigh

Jeanette Helen Morrison (July 6, 1927 – October 3, 2004), known professionally as Janet Leigh, was an American actress. Raised in Stockton, California, by working-class parents, Leigh was discovered at 18 by actress Norma Shearer, who helped he ...

(stage name for Jeanette Helen Morrison), American film actress known for '' Psycho'' and ''The Fog

''The Fog'' is a 1980 American independent supernatural horror film directed by John Carpenter, who also co-wrote the screenplay and created the music for the film. It stars Adrienne Barbeau, Jamie Lee Curtis, Tom Atkins, Janet Leigh and H ...

''; in Merced, California

Merced (; Spanish for "Mercy") is a city in, and the county seat of, Merced County, California, United States, in the San Joaquin Valley. As of the 2020 census, the city had a population of 86,333, up from 78,958 in 2010. Incorporated on Apri ...

(d. 2004)

** Pat Paulsen

Patrick Layton Paulsen (July 6, 1927 – April 25, 1997) was an American comedian and satirist notable for his roles on several of the Smothers Brothers television shows, and for his satirical campaigns for President of the United States between ...

, American comedian and perennial presidential candidate; in South Bend, Washington

South Bend is a city in and the county seat of Pacific County, Washington, Pacific County, Washington (state), Washington, United States. The population was 1,746 as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. The town is widely-known for its ...

(d. 1997)

** Alan Freeman

Alan Leslie Freeman MBE (6 July 1927 – 27 November 2006), nicknamed "Fluff", was an Australian-born British disc jockey and radio personality in the United Kingdom for 40 years, best known for presenting '' Pick of the Pops'' from 1961 to 20 ...

, Australian-born British disc jockey who was the long time host of ''Pick of the Pops

''Pick of the Pops'' is a long-running BBC Radio programme; it was based originally on the Top 20 from the UK singles chart and was first broadcast on the BBC Light Programme on 4 October 1955. It transferred to BBC Radio 1 (simulcast on BBC Rad ...

''; in Melbourne

Melbourne ( , ; Boonwurrung language, Boonwurrung/ or ) is the List of Australian capital cities, capital and List of cities in Australia by population, most populous city of the States and territories of Australia, Australian state of Victori ...

(d. 2006)

** Dolores Claman

Dolores Olga Claman (July 6, 1927July 17, 2021) was a Canadian composer and pianist. She is best known for having composed the 1968 theme song for Canadian Broadcasting Corporation's (CBC) ''Hockey Night In Canada'' show, known simply as "The ...

, Canadian composer who created the popular theme song for CBC's Hockey Night In Canada

''Hockey Night in Canada'' (often abbreviated ''Hockey Night'' or ''HNiC'') is a long-running program of broadcast ice hockey play-by-play coverage in Canada. With roots in pioneering hockey coverage on private radio stations as early as 1923, ...

; in Vancouver

Vancouver is a major city in Western Canada, located in the Lower Mainland region of British Columbia. As the List of cities in British Columbia, most populous city in the province, the 2021 Canadian census recorded 662,248 people in the cit ...

(d. 2021)

July 7, 1927 (Thursday)

* Portuguese neurosurgeon Egas Moniz first presented his discovery ofcerebral angiography

Cerebral angiography is a form of angiography which provides images of blood vessels in and around the brain, thereby allowing detection of abnormalities such as arteriovenous malformations and aneurysms.

It was pioneered in 1927 by the Portugues ...

arterial encephalography in a paper presented at the Societe de Neurologie in Paris. Moniz had discovered a safe method of detecting brain tumors by injecting contrast into the cervical carotid artery.

* In his weekly magazine, ''The Dearborn Independent

''The Dearborn Independent'', also known as ''The Ford International Weekly'', was a weekly newspaper established in 1901, and published by Henry Ford from 1919 through 1927. At its height during the mid-1920s it claimed a circulation of between ...

'', auto manufacturer Henry Ford

Henry Ford (July 30, 1863 – April 7, 1947) was an American Technological and industrial history of the United States, industrialist and business magnate. As the founder of the Ford Motor Company, he is credited as a pioneer in making automob ...

published an apology, widely reprinted, for his anti-Semitic views. The missive was part of a settlement of a libel lawsuit brought by Aaron Sapiro

Aaron Leland Sapiro (February 5, 1884 – November 23, 1959) was a Jewish American cooperative activist and lawyer for the farmers' movement during the 1920s. He became notable for suing Henry Ford the auto-magnate for libel as a result of an ar ...

.

* Under pressure from the victorious Allies of World War I, Germany's Reichstag voted 390–44 to pass a law prohibiting the import or export of war materials.

* Born:

** Doc Severinsen

Carl Hilding "Doc" Severinsen (born July 7, 1927) is an American retired jazz trumpeter who led the NBC Orchestra on ''The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson''.

Early life

Severinsen was born in Arlington, Oregon, to Minnie Mae (1897–1998) ...

(stage name for Carl Hilding Severinsen), American bandleader and jazz trumpeter who led the NBC Orchestra for Johnny Carson on ''The Tonight Show''; in Arlington, Oregon

Arlington is a city in Gilliam County, Oregon, Gilliam County, Oregon, United States. The city's population was 586 at the 2010 United States Census, 2010 census and has a 2019 estimate of 591.

History

The account of how the city received its n ...

** Martin Ransohoff

Martin Nelson Ransohoff (July 7, 1927 – December 13, 2017) was an American film and television producer, and member of the Ransohoff, Ransohoff family.

Early life and education

Ransohoff was born on July 7, 1927, in New Orleans, New Orleans, ...

, American film and television producer who founded the Filmways

Filmways, Inc. (also known as Filmways Pictures and Filmways Television) was a television and film production company founded by American film executive Martin Ransohoff and Edwin Kasper in 1952. It is probably best remembered as the production c ...

production company; in New Orleans

New Orleans (commonly known as NOLA or The Big Easy among other nicknames) is a Consolidated city-county, consolidated city-parish located along the Mississippi River in the U.S. state of Louisiana. With a population of 383,997 at the 2020 ...

(d. 2017)

* Died: Gösta Mittag-Leffler

Magnus Gustaf "Gösta" Mittag-Leffler (16 March 1846 – 7 July 1927) was a Sweden, Swedish mathematician. His mathematical contributions are connected chiefly with the theory of functions that today is called complex analysis. He founded the pre ...

, 81, Swedish mathematician known for Mittag-Leffler's theorem

In complex analysis, Mittag-Leffler's theorem concerns the existence of meromorphic functions with prescribed poles. Conversely, it can be used to express any meromorphic function as a sum of partial fractions. It is sister to the Weierstrass fa ...

July 8, 1927 (Friday)

*Charles Lindbergh

Charles Augustus Lindbergh (February 4, 1902 – August 26, 1974) was an American aviator, military officer, and author. On May 20–21, 1927, he made the first nonstop flight from New York (state), New York to Paris, a distance of . His aircra ...

inaugurated the Transcontinental Air Transport

Transcontinental Air Transport (T-A-T) was an airline founded in 1928 by Clement Melville Keys that merged in 1930 with Western Air Express to form what became TWA. Keys enlisted the help of Charles Lindbergh to design a transcontinental network t ...

airline with the first passenger flight from New York to Los Angeles. The trip would take 48 hours.

* Ban Johnson

Byron Bancroft "Ban" Johnson (January 5, 1864 – March 28, 1931) was an American executive in professional baseball who served as the founder and first president of the American League (AL).

Johnson developed the AL—a descendant of th ...

, founder of the American League

The American League of Professional Baseball Clubs, known simply as the American League (AL), is the younger of two sports leagues, leagues constituting Major League Baseball (MLB) in the United States and Canada. It developed from the Western L ...

and its president since 1901, was forced to resign by the owners of the eight teams.

* Died: Max Hoffmann

Carl Adolf Maximilian Hoffmann (25 January 1869 – 8 July 1927) was a German military officer and strategist. As a staff officer at the beginning of World War I, he was Deputy Chief of Staff of the 8th Army, soon promoted Chief of Staff. Hoff ...

, 58, German general who led the attack on Russia in World War I

July 9, 1927 (Saturday)

* Torrential rains inGermany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

swelled the Elbe River

The Elbe ( ; ; or ''Elv''; Upper and , ) is one of the major rivers of Central Europe. It rises in the Giant Mountains of the northern Czech Republic before traversing much of Bohemia (western half of the Czech Republic), then Germany and flo ...

and led to flash floods that killed hundreds in Saxony

Saxony, officially the Free State of Saxony, is a landlocked state of Germany, bordering the states of Brandenburg, Saxony-Anhalt, Thuringia, and Bavaria, as well as the countries of Poland and the Czech Republic. Its capital is Dresden, and ...

. In the village of Berggießhübel, 93 people drowned when a 7-foot-high wave swept through the town. At least 200 people were reported to have died.

* The Federal Trade Commission

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) is an independent agency of the United States government whose principal mission is the enforcement of civil (non-criminal) United States antitrust law, antitrust law and the promotion of consumer protection. It ...

outlawed the practice of "block booking" by film distributors, issuing a cease and desist order to Paramount Pictures

Paramount Pictures Corporation, commonly known as Paramount Pictures or simply Paramount, is an American film production company, production and Distribution (marketing), distribution company and the flagship namesake subsidiary of Paramount ...

. Until the FTC order, Paramount required cinemas to rent films as part of a block of movies, usually with the arrangement that a popular film had to be accepted along with several less attractive releases.

* Born:

** Ed Ames

Edmund Dantes Urick (July 9, 1927 – May 21, 2023), known professionally as Ed Ames or Eddie Ames, was an American pop singer and actor. He was known for playing Mingo in the television series ''Daniel Boone (1964 TV series), Daniel Boone'', and ...

(stage name for Edmund Dantes Urick), American singer for the Ames Brothers

The Ames Brothers were an American singing quartet, consisting of four siblings from Malden, Massachusetts, who were particularly famous in the 1950s for their traditional pop hits.

Biography

The Urick brothers were born in Malden, Massachus ...

and white actor known for portraying American Indian characters, most notably on the ''Daniel Boone'' television show; in Malden, Massachusetts

Malden is a city in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, Middlesex County, Massachusetts, United States. At the time of the 2020 United States census, 2020 U.S. Census, the population was 66,263 people.

History

Malden is a hilly woodland area no ...

(d 2023)

** Red Kelly

Leonard Patrick "Red" Kelly (July 9, 1927 – May 2, 2019) was a Canadian professional hockey player and coach. Kelly played on more Stanley Cup-winning teams (eight) than any other player who never played for the Montreal Canadiens; Henri R ...

(Leonard Patrick Kelly), Canadian NHL star and Hockey Hall of Fame

The Hockey Hall of Fame () is a museum and hall of fame located in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Dedicated to the history of ice hockey, it holds exhibits about players, teams, National Hockey League (NHL) records, memorabilia and National Hockey Le ...

inductee (d. 2019)

* Died:

** John Drew, Jr.

John Drew Jr. (November 13, 1853 – July 9, 1927), commonly known as John Drew during his life, was an American stage actor noted for his roles in Shakespearean comedy, society drama, and light comedies. He was the eldest son of John Drew Sr., ...

, 73, American stage actor

** Gregory Kelly Gregory or Greg Kelly may refer to:

* Gregory Kelly (bishop) (born 1956), American Catholic bishop

* Gregory Kelly (actor) (1892–1927), American stage actor

* Greg Kelly (born 1968), American television journalist

* Greg Kelly (Coronation Street), ...

, 36, American stage actor and husband of actress Ruth Gordon

Ruth Gordon Jones (October 30, 1896 – August 28, 1985) was an American actress, playwright and screenwriter. She began her career performing on Broadway at age 19. Known for her nasal voice and distinctive personality, Gordon gained internati ...

, who outlived him by 58 years.

July 10, 1927 (Sunday)

* Irish Vice-President and Minister of JusticeKevin O'Higgins

Kevin Christopher O'Higgins (; 7 June 1892 – 10 July 1927) was an Irish politician who served as Vice-President of the Executive Council and Minister for Justice from 1922 to 1927, Minister for External Affairs from June 1927 to July 1927 a ...

was assassinated while walking to mid-day Mass at Blackrock

BlackRock, Inc. is an American Multinational corporation, multinational investment company. Founded in 1988, initially as an enterprise risk management and fixed income institutional asset manager, BlackRock is the world's largest asset manager ...

in Dublin

Dublin is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. Situated on Dublin Bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, and is bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, pa ...

. O'Higgins, described as "the Irish Mussolini" and "probably the most respected and at the same time the most hated man in Ireland", had given his bodyguard the day off. A car pulled up beside him and three gunmen jumped out and began firing. Reportedly, he was shot six times, but remained conscious for several hours after being taken back to his home. In response to his murder, the Irish Dail passed legislation that effectively barred the Irish Republican Army from running candidates for office.

* General José Sanjurjo

José Sanjurjo y Sacanell (; 28 March 1872 – 20 July 1936) was a Spanish military officer who was one of the military leaders who plotted the July 1936 ''coup d'état'' that started the Spanish Civil War.

He was endowed the nobiliary title ...

declared the pacification of Spanish Morocco

The Spanish protectorate in Morocco was established on 27 November 1912 by a treaty between France and Spain that converted the Spanish sphere of influence in Morocco into a formal protectorate.

The Spanish protectorate consisted of a norther ...

and the end of the Moroccan War after 18 years.

* Born: David Dinkins

David Norman Dinkins (July 10, 1927 – November 23, 2020) was an American politician, lawyer, and author who served as the 106th mayor of New York City from 1990 to 1993.

Dinkins was among the more than 20,000 Montford Point Marine Associa ...

, first African-American mayor of New York City

The mayor of New York City, officially mayor of the City of New York, is head of the executive branch of the government of New York City and the chief executive of New York City. The Mayoralty in the United States, mayor's office administers all ...

(1990–1993); in Trenton, New Jersey

Trenton is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the U.S. state of New Jersey and the county seat of Mercer County, New Jersey, Mercer County. It was the federal capital, capital of the United States from November 1 until D ...

(d. 2020)

July 11, 1927 (Monday)

* The very first7-Eleven

7-Eleven, Inc. is an American convenience store chain, headquartered in Irving, Texas. It is a wholly owned subsidiary of Seven-Eleven Japan, which in turn is owned by the retail holdings company Seven & I Holdings.

The chain was founde ...

convenience store opened, on Edgefield and 12th Streets in Dallas, Texas, on 7/11/1927, with the new concept of staying open from 7:00 am to 11:00 pm.

* Striking at 2:10 in the afternoon, an earthquake in Palestine (now Israel) killed more than 200 people. Though initial reports set a higher death toll, a later report by the British Secretary of State for the Colonies put the death toll at 200 in Palestine and another eight in the neighboring Trans-Jordan (now Jordan). Hardest hit were Nablus

Nablus ( ; , ) is a State of Palestine, Palestinian city in the West Bank, located approximately north of Jerusalem, with a population of 156,906. Located between Mount Ebal and Mount Gerizim, it is the capital of the Nablus Governorate and a ...

, Ramallah

Ramallah ( , ; ) is a Palestinians, Palestinian city in the central West Bank, that serves as the administrative capital of the State of Palestine. It is situated on the Judaean Mountains, north of Jerusalem, at an average elevation of abov ...

and Lydda

Lod (, ), also known as Lydda () and Lidd (, or ), is a city southeast of Tel Aviv and northwest of Jerusalem in the Central District of Israel. It is situated between the lower Shephelah on the east and the coastal plain on the west. The ci ...

. The River Jordan

The Jordan River or River Jordan (, ''Nahr al-ʾUrdunn''; , ''Nəhar hayYardēn''), also known as ''Nahr Al-Sharieat'' (), is a endorheic basin, endorheic river in the Levant that flows roughly north to south through the Sea of Galilee and d ...

dried up, and remained that way for 21 hours.

* More than a century after her death, a sealed box, owned by Joanna Southcott

Joanna Southcott (or Southcote; April 1750 – 26 December 1814) was a British self-described religious prophetess from Devon. A "Southcottian" movement continued in various forms after her death.

Early life

Joanna Southcott was born in the h ...

and said to contain her final prophecies, was opened at Westminster. Inside the container was a pistol, a nightcap, some coins and other personal belongings, but nothing mysterious.

* African-American singer and actress Ethel Waters

Ethel Waters (October 31, 1896 – September 1, 1977) was an American singer and actress. Waters frequently performed jazz, swing, and pop music on the Broadway stage and in concerts. She began her career in the 1920s singing blues. Her no ...

made her Broadway debut, appearing in the production ''Africana''.

* Born: Theodore H. Maiman, American inventor and physicist who developed the laser

A laser is a device that emits light through a process of optical amplification based on the stimulated emission of electromagnetic radiation. The word ''laser'' originated as an acronym for light amplification by stimulated emission of radi ...

, patented in 1960; in Los Angeles

Los Angeles, often referred to by its initials L.A., is the List of municipalities in California, most populous city in the U.S. state of California, and the commercial, Financial District, Los Angeles, financial, and Culture of Los Angeles, ...

(d. 2007)

July 12, 1927 (Tuesday)

*

* Chen Duxiu

Chen Duxiu ( zh, t=陳獨秀, p=Chén Dúxiù, w=Ch'en Tu-hsiu; 9 October 1879 – 27 May 1942) was a Chinese revolutionary, writer, educator, and political philosopher who co-founded the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in 1921, serving as its fi ...

, who had been the first General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party

The general secretary of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party ( zh, s=中国共产党中央委员会总书记, p=Zhōngguó Gòngchǎndǎng Zhōngyāng Wěiyuánhuì Zǒngshūjì) is the leader of the Chinese Communist Part ...

, resigned from that position. In 1925, he had been succeeded as chairman by Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; traditionally Romanization of Chinese, romanised as Mao Tse-tung. (26December 18939September 1976) was a Chinese politician, revolutionary, and political theorist who founded the People's Republic of China (PRC) in ...

.

* The convention to create the International Relief Union was adopted at the League of Nations

The League of Nations (LN or LoN; , SdN) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace ...

by the 43 states in attendance, and entered into force on December 27, 1932. Intended as a unified organization for disaster relief, the I.R.U. had only limited success in assisting the International Red Cross

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) is a aid agency, humanitarian organization based in Geneva, Switzerland, and is a three-time Nobel Prize laureate. The organization has played an instrumental role in the development of Law of ...

.

* Born: Tom Benson

Thomas Milton Benson Jr. (July 12, 1927 – March 15, 2018) was an American businessman, philanthropist and sports franchise owner. He was the owner of several automobile dealerships before buying the New Orleans Saints of the National Football L ...

, American entrepreneur, philanthropist, and owner of the NFL's New Orleans Saints

The New Orleans Saints are a professional American football team based in New Orleans. The Saints compete in the National Football League (NFL) as a member of the National Football Conference (NFC) NFC South, South division. Since 1975, the team ...

and the NBA's New Orleans Pelicans

The New Orleans Pelicans are an American professional basketball team based in New Orleans. The Pelicans compete in the National Basketball Association (NBA) as a member of the Southwest Division (NBA), Southwest Division of the Western Confere ...

; in New Orleans

New Orleans (commonly known as NOLA or The Big Easy among other nicknames) is a Consolidated city-county, consolidated city-parish located along the Mississippi River in the U.S. state of Louisiana. With a population of 383,997 at the 2020 ...

(d. 2018)

July 13, 1927 (Wednesday)

* French Prime MinisterRaymond Poincaré

Raymond Nicolas Landry Poincaré (; 20 August 1860 – 15 October 1934) was a French statesman who served as President of France from 1913 to 1920, and three times as Prime Minister of France. He was a conservative leader, primarily committed to ...

, who was also the Finance Minister, received a vote of confidence in the Chamber of Deputies and an endorsement of his call to not add further spending to the budget. Informing the legislators that "Messieurs, the whole fate of French finances rests on your decision," Poincaré won his point by a margin of 347 to 200.

* Born: Simone Veil

Simone Veil (; ; 13 July 1927 – 30 June 2017) was a French magistrate, Holocaust survivor, and politician who served as health minister in several governments and was President of the European Parliament from 1979 to 1982, the first woman t ...

, President of the European Parliament (1979–1982), former French Minister of Health, and survivor of the Auschwitz concentration camp during the Holocaust; as Simone Annie Liline Jacob, in Nice

Nice ( ; ) is a city in and the prefecture of the Alpes-Maritimes department in France. The Nice agglomeration extends far beyond the administrative city limits, with a population of nearly one millionCzechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia ( ; Czech language, Czech and , ''Česko-Slovensko'') was a landlocked country in Central Europe, created in 1918, when it declared its independence from Austria-Hungary. In 1938, after the Munich Agreement, the Sudetenland beca ...

created the autonomous Slovak Province (''Slovenska Krajina'') in response to demands by the Slovak People's Party

Andrej Hlinka, Hlinka's Slovak People's Party (), also known as the Slovak People's Party (, SĽS) or the Hlinka Party, was a far-right Clerical fascism, clerico-fascist political party with a strong Catholic fundamentalism, Catholic fundamental ...

.

* Born:

** Peggy Parish

Margaret Cecile "Peggy" Parish (July 14, 1927 – November 19, 1988) was an American writer known best for the children's book series and fictional character '' Amelia Bedelia''. Parish was born in Manning, South Carolina, attended the Univers ...

, American author who created the ''Amelia Bedelia

''Amelia Bedelia'' is a series of American children's books that were written by Peggy Parish from 1963 until her death in 1988, and by her nephew, Herman, from 1995 to 2022. The stories follow Amelia Bedelia, a maid who repeatedly misunderstand ...

'' series of books; in Manning, South Carolina

Manning is a city in and the county seat of Clarendon County, South Carolina, Clarendon County, South Carolina, United States. The population was 3,245 as of the 2010 United States Census, 2010 census, with an estimated population in 2018 of 3,94 ...

(d. 1988)

** John Chancellor

John William Chancellor (July 14, 1927 – July 12, 1996) was an American journalist who spent most of his career with NBC News. He is considered a pioneer in television news. Chancellor served as anchor of the ''NBC Nightly News'' from 1970 to ...

, American news anchorman for NBC Nightly News

''NBC Nightly News'' (titled as ''NBC Nightly News with Tom Llamas'' for its weeknight broadcasts ) is the flagship daily evening News broadcasting#Television, television news program for NBC News, the news division of the NBC television network ...

from 1970 to 1982, and a commentator 1982 to 1993; in Chicago

Chicago is the List of municipalities in Illinois, most populous city in the U.S. state of Illinois and in the Midwestern United States. With a population of 2,746,388, as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it is the List of Unite ...

(d. 1996).

July 15, 1927 (Friday)

* Eighty-four protesters were killed in Vienna, and the Austrian capital's Palace of Justice (''Justizpalast'') was burned down, in the aftermath of a riot that followed the acquittal of three accused murderers. Vienna Police Chief Johannes Schober had ordered his men to fire into the crowd to disperse the mob. * InGreece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

, the government issued decrees directed against the Macedonian

Macedonian most often refers to someone or something from or related to Macedonia.

Macedonian(s) may refer to:

People Modern

* Macedonians (ethnic group), a nation and a South Slavic ethnic group primarily associated with North Macedonia

* Mac ...

minority of Slavic

Slavic, Slav or Slavonic may refer to:

Peoples

* Slavic peoples, an ethno-linguistic group living in Europe and Asia

** East Slavic peoples, eastern group of Slavic peoples

** South Slavic peoples, southern group of Slavic peoples

** West Slav ...

descent. The new rules banned use of Macedonian language

Macedonian ( ; , , ) is an Eastern South Slavic language. It is part of the Indo-European languages, Indo-European language family, and is one of the Slavic languages, which are part of a larger Balto-Slavic languages, Balto-Slavic branch. Sp ...

and decreed that Cyrillic inscriptions were to be removed from churches.

* Born:

** Ann Jellicoe

Patricia Ann Jellicoe (15 July 1927 – 31 August 2017) was an English playwright, theatre director and actress. Although her work covered many areas of theatre and film, she is best known for "pushing the envelope" of the stage play, devisin ...

, British playwright; in Middlesbrough

Middlesbrough ( ), colloquially known as Boro, is a port town in the Borough of Middlesbrough, North Yorkshire, England. Lying to the south of the River Tees, Middlesbrough forms part of the Teesside Built up area, built-up area and the Tees Va ...

, Yorkshire

Yorkshire ( ) is an area of Northern England which was History of Yorkshire, historically a county. Despite no longer being used for administration, Yorkshire retains a strong regional identity. The county was named after its county town, the ...

(d. 2017)

** Carmen Zapata

Carmen Margarita Zapata (July 15, 1927 – January 5, 2014) often referred to as "The First Lady of the Hispanic Theater" was an American actress best known for her role in the PBS bilingual children's program ''Villa Alegre''. Zapata was also ...

, American stage and film actress; in New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

(d. 2014)

* Died: Countess Markievicz

Constance Georgine Markievicz ( ; ' Gore-Booth; 4 February 1868 – 15 July 1927), also known as Countess Markievicz and Madame Markievicz, was an Irish politician, revolutionary, nationalist, suffragist, and socialist who was the first woman ...

( Constance Gore-Booth), 69, Irish politician who, in 1918, had become the first woman to be elected to the United Kingdom's House of Commons. After Ireland's independence from the United Kingdom, she was the Irish Free State

The Irish Free State (6 December 192229 December 1937), also known by its Irish-language, Irish name ( , ), was a State (polity), state established in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. The treaty ended the three-ye ...

's first Minister for Labour.

July 16, 1927 (Saturday)

* TheBattle of Ocotal

The Battle of Ocotal occurred in July 1927, during the American occupation of Nicaragua.

A large force of rebels loyal to Augusto César Sandino attacked the garrison of Ocotal, which was held by a small group of US Marines and Nicaraguan Natio ...

began at 1:15 a.m., when several hundred Nicaraguan rebels, led by Augusto César Sandino

Augusto César Sandino (; 18 May 1895 21 February 1934), full name Augusto Nicolás Calderón Sandino, was a Nicaraguan revolutionary, founder of the militant group EDSN, and leader of a rebellion between 1927 and 1933 against the United Sta ...

, attacked a barracks at Ocotal

Ocotal () is the capital of the Nueva Segovia Department in Nicaragua, Central America and the municipal seat of Ocotal Municipality.

History

The region occupied by the city of Ocotal was formerly occupied by different ethnic groups that had prob ...

, occupied by 38 U.S. Marines and 47 Nicaraguan civil guards. USMC Captain Gilbert Hatfield and his men withstood three charges. At mid-morning, rescue came from Major Ross E. Rowell

Ross Erastus Rowell (September 22, 1884 – September 6, 1947) was a highly decorated United States Marine Corps aviator who served as the Marine Corps' Director of Aviation from May 30, 1935, until March 10, 1939, and was one of the three senior ...

, who had gotten word of the attack and led "the first dive-bombing campaign in history". At battle's end, 300 rebels and one U.S. Marine had been killed.

* Cartoonist Theodor Geisel, 23, was published for the first time under the pen name

A pen name or nom-de-plume is a pseudonym (or, in some cases, a variant form of a real name) adopted by an author and printed on the title page or by-line of their works in place of their real name.

A pen name may be used to make the author's na ...

inspired by his mother's maiden name, "Seuss", in the July 16, 1927, ''Saturday Evening Post'', effectively beginning his career as illustrator and author Dr. Seuss

Theodor Seuss Geisel ( ;"Seuss"

'' Reichstag passed comprehensive

*

*

* King

* King

'' Reichstag passed comprehensive

unemployment insurance

Unemployment, according to the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), is the proportion of people above a specified age (usually 15) not being in paid employment or self-employment but currently available for work du ...

and maternity leave

Parental leave, or family leave, is an employee benefit available in almost all countries. The term "parental leave" may include maternity, paternity, and adoption leave; or may be used distinctively from "maternity leave" and "paternity leave ...

laws, by a margin of 356–47.

July 17, 1927 (Sunday)

* In furtherance of the Turkishnationalist movement

The Nationalist Movement is a Mississippi-founded white nationalist organization with headquarters in Georgia that advocates what it calls a "pro-majority" position. It has been called white supremacist by the Associated Press and Anti-Defamati ...

, Turkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

directed the relocation of 1,400 members of the Kurdish

Kurdish may refer to:

*Kurds or Kurdish people

*Kurdish language

** Northern Kurdish (Kurmanji)

**Central Kurdish (Sorani)

**Southern Kurdish

** Laki Kurdish

*Kurdish alphabets

*Kurdistan, the land of the Kurdish people which includes:

**Southern ...

minority from their homes in the southeast, to the far west. This was followed by deportation of Armenian and Syriac people from the same area.

July 18, 1927 (Monday)

*

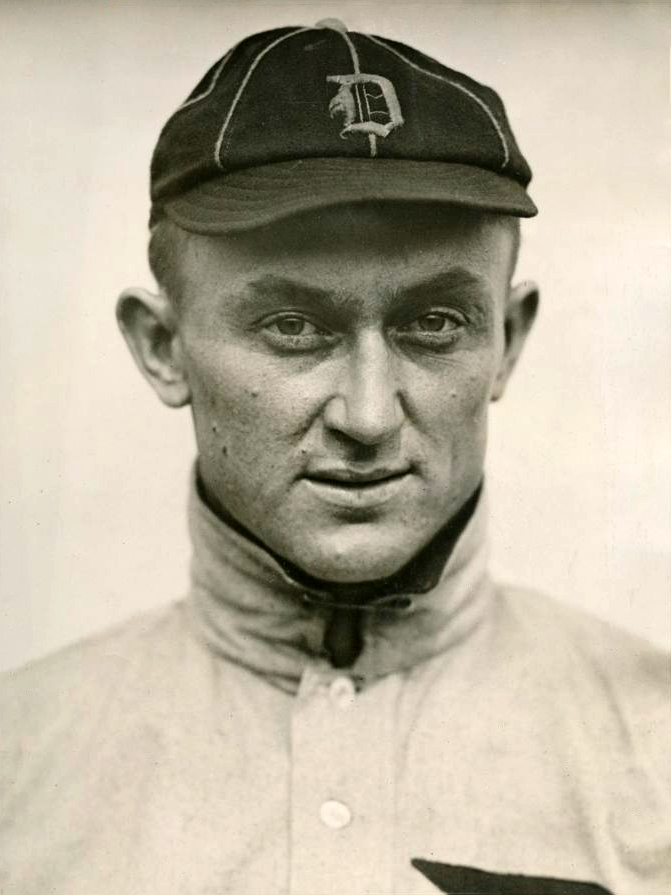

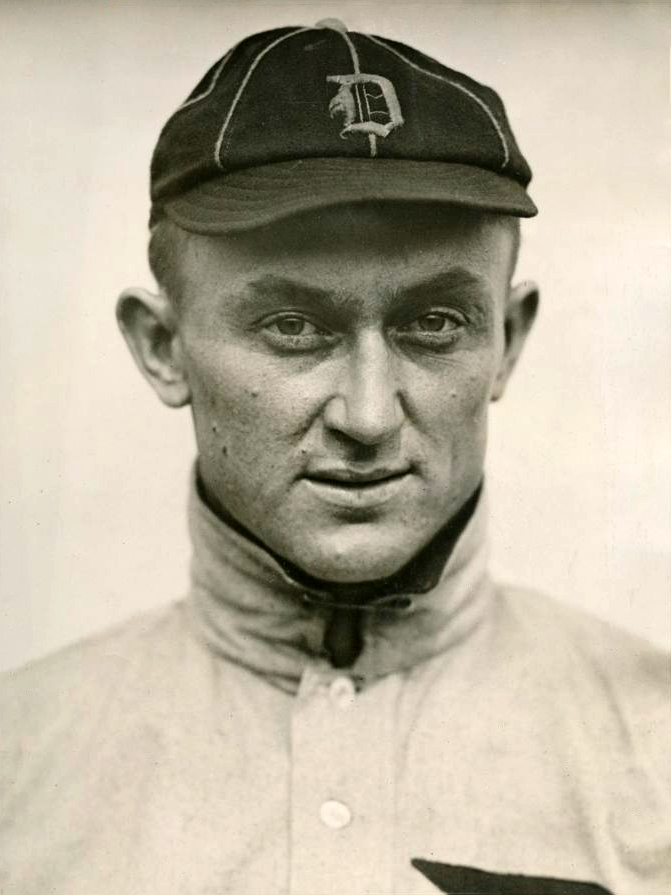

* Ty Cobb

Tyrus Raymond Cobb (December 18, 1886 – July 17, 1961), nicknamed "the Georgia Peach", was an American professional baseball center fielder. A native of rural Narrows, Georgia, Cobb played 24 seasons in Major League Baseball (MLB). He spent ...

got his 4,000th hit (and would finish with 4,191) playing for the Philadelphia A's at Detroit against his former team, the Tigers. As one commentator noted fifty years later, "the event went almost unnoticed". On the same day, future Hall of Famer Mel Ott

Melvin Thomas Ott (March 2, 1909 – November 21, 1958), nicknamed "Master Melvin", was an American professional baseball right fielder, who played in Major League Baseball (MLB) for the New York Giants, from through .

He batted left-handed ...

hit his first home run, an inside the park homer.

* Born: Kurt Masur

Kurt Masur (; 18 July 192719 December 2015) was a German Conducting, conductor. Called "one of the last old-style maestros", he directed many of the principal orchestras of his era. He had a long career as the Kapellmeister of the Leipzig Gewand ...

, East German conductor, who later conducted the London Philharmonic Orchestra

The London Philharmonic Orchestra (LPO) is a British orchestra based in London. One of five permanent symphony orchestras in London, the LPO was founded by the conductors Thomas Beecham, Sir Thomas Beecham and Malcolm Sargent in 1932 as a riv ...

; in Brieg, Prussia

Prussia (; ; Old Prussian: ''Prūsija'') was a Germans, German state centred on the North European Plain that originated from the 1525 secularization of the Prussia (region), Prussian part of the State of the Teutonic Order. For centuries, ...

(now Brzeg, Poland) (d. 2015)

July 19, 1927 (Tuesday)

*Pan American Airways

Pan American World Airways, originally founded as Pan American Airways and more commonly known as Pan Am, was an airline that was the principal and largest international air carrier and unofficial overseas flag carrier of the United States for ...

was awarded its first flight route, signing the contract to transport American mail between Key West

Key West is an island in the Straits of Florida, at the southern end of the U.S. state of Florida. Together with all or parts of the separate islands of Dredgers Key, Fleming Key, Sunset Key, and the northern part of Stock Island, it con ...

and Havana

Havana (; ) is the capital and largest city of Cuba. The heart of La Habana Province, Havana is the country's main port and commercial center.Amadou Bamba

Sheikh Amadou Bamba (1853–1927), also known to followers as the Servant of Muhammad, the Messenger () and Serigne Touba or "Sheikh of Touba", was a wali, Sufi saint and religious leader in Senegal and the founder of the Mouride Brotherh ...

, 74, Senegal

Senegal, officially the Republic of Senegal, is the westernmost country in West Africa, situated on the Atlantic Ocean coastline. It borders Mauritania to Mauritania–Senegal border, the north, Mali to Mali–Senegal border, the east, Guinea t ...

ese Muslim religious leader and founder of the Murid Order

** Zhao Shiyan

Zhao Shiyan (; 13 April 1901–19 July 1927) was a Chinese Communist revolutionary and former Chinese premier Li Peng's uncle.

Biography

Zhao was born in Youyang Zhou, Sichuan (now Youyang Tujia and Miao Autonomous County, Chongqing), on 13 ...

, 26, Chinese Communist official, was executed after being captured by Nationalist forces.

July 20, 1927 (Wednesday)

* King

* King Ferdinand of Romania

Ferdinand I (Ferdinand Viktor Albert Meinrad; 24 August 1865 – 20 July 1927), nicknamed ''Întregitorul'' ("the Unifier"), was King of Romania from 10 October 1914 until his death in 1927. Ferdinand was the second son of Leopold, Prince of Ho ...

, who had reigned since 1914, died at 2:15 am at his palace in Sinaia

Sinaia () is a town and a mountain resort in Prahova County, Romania. It is situated in the historical region of Muntenia. The town was named after the Sinaia Monastery of 1695, around which it was built. The monastery, in turn, is named after ...

after a battle with cancer. At 6:00 pm, his 5-year-old grandson, was proclaimed as the new monarch, King Michael I. A regency council, headed by Prince Nicholas, was appointed to act on the boy king's behalf during his childhood.

* The French Olympic Committee

The French National Olympic and Sports Committee (, CNOSF) is the National Olympic Committee of France. It is responsible for France's participation in the Olympic Games, as well as for all of France's overseas departments and territories.

Histo ...

, lacking funds, voted not to send a team to the 1928 games scheduled for Amsterdam. French perfume magnate François Coty

François Coty (; born Joseph Marie François Spoturno ; 3 May 1874 – 25 July 1934) was a French perfumer, businessman, newspaper publisher, politician and patron of the arts. He was the founder of the Coty, Coty perfume company, today a multin ...

would come to the team's rescue by loaning one million francs to the committee.

* Germany and Japan established closer ties by the signing of a trade treaty in Tokyo

Tokyo, officially the Tokyo Metropolis, is the capital of Japan, capital and List of cities in Japan, most populous city in Japan. With a population of over 14 million in the city proper in 2023, it is List of largest cities, one of the most ...

between the two nations, by Ambassador Wilhelm Solf

Wilhelm Heinrich Solf (5 October 1862 – 6 February 1936) was a German scholar, diplomat, jurist and statesman.

Early life

Solf was born into a wealthy and liberal family in Berlin. He attended secondary schools in Anklam, western Pomerania, a ...

and Japan's Prime Minister, Baron Tanaka.

* Born:

** Leon C. Hirsch, American inventor of the Auto Suture surgical stapler, and founder of United States Surgical Corporation; in the Bronx

The Bronx ( ) is the northernmost of the five Boroughs of New York City, boroughs of New York City, coextensive with Bronx County, in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York. It shares a land border with Westchester County, New York, West ...

, New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

** Barbara Bergmann

Barbara Rose Bergmann (20 July 1927 – 5 April 2015) was a feminist economist. Her work covers many topics from childcare and gender issues to poverty and Social Security. Bergmann was a co-founder and president of the International Association ...

, American economist; in the Bronx

The Bronx ( ) is the northernmost of the five Boroughs of New York City, boroughs of New York City, coextensive with Bronx County, in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York. It shares a land border with Westchester County, New York, West ...

, New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

(d. 2015)

** Lyudmila Alexeyeva

Lyudmila Mikhaylovna Alexeyeva (, ; 20 July 1927 – 8 December 2018) was a Russian historian and human-rights activist who was a founding member in 1976 of the Moscow Helsinki Watch Group and one of the last Soviet dissidents active in post-S ...

, Soviet dissident and Russian human rights activist; in Yevpatoria

Yevpatoria (; ; ; ) is a city in western Crimea, north of Kalamita Bay. Yevpatoria serves as the administrative center of Yevpatoria Municipality, one of the districts (''raions'') into which Crimea is divided. It had a population of

His ...

, Crimean ASSR

Several different governments controlled the Crimean Peninsula during the period of the Soviet Union, from the 1920s to 1991. The government of Crimea from 1921 to 1936 was the Crimean Autonomous Socialist Soviet Republic, which was an Autonomo ...

, Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

(d. 2018)

July 21, 1927 (Thursday)

* Before a crowd of 90,000 at New York's Yankee Stadium, former heavyweight boxing championJack Dempsey

William Harrison "Jack" Dempsey (June 24, 1895 – May 31, 1983), nicknamed Kid Blackie and The Manassa Mauler, was an American boxer who competed from 1914 to 1927, and world heavyweight champion from 1919 to 1926.

One of the most iconic athl ...

, 32, fought with Jack Sharkey

Jack Sharkey (born Joseph Paul Zukauskas, , October 26, 1902 – August 17, 1994) was a Lithuanian-American boxer who held the NYSAC, NBA, and ''The Ring'' heavyweight titles from 1932 to 1933.

Boxing career

He took his ring name from his ...

to determine who would be the challenger in a September bout against champion Gene Tunney

James Joseph Tunney (May 25, 1897 – November 7, 1978) was an American professional boxer who competed from 1915 to 1928. He held the world heavyweight title from 1926 to 1928, and the American light heavyweight title twice between 1922 and 1923 ...

. Sharkey was winning after six rounds. As the 7th began, Dempsey struck two low body blows to Sharkey, who turned toward referee Jack O'Sullivan to complain of a foul. When Sharkey turned his head, Dempsey struck him in the jaw with a short left hook and knocked him out.

* The Ford Motor Company

Ford Motor Company (commonly known as Ford) is an American multinational corporation, multinational automobile manufacturer headquartered in Dearborn, Michigan, United States. It was founded by Henry Ford and incorporated on June 16, 1903. T ...

took steps toward the creation of Fordlândia

Fordlândia (, ''Ford-land'') is a district and adjacent area of in the city of Aveiro, in the Brazilian state of Pará. It is located on the east banks of the Tapajós river roughly south of the city of Santarém.

It was established by ...

, by spending $8,000,000 to buy 1,000,000 hectares (2,470,000 acres or 3,861 square miles) of land in Brazil

Brazil, officially the Federative Republic of Brazil, is the largest country in South America. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by area, fifth-largest country by area and the List of countries and dependencies by population ...

's Pará

Pará () is a Federative units of Brazil, state of Brazil, located in northern Brazil and traversed by the lower Amazon River. It borders the Brazilian states of Amapá, Maranhão, Tocantins (state), Tocantins, Mato Grosso, Amazonas (Brazilian st ...

State, in return for a 50-year tax exemption and full legal jurisdiction rights.

* The day after his father's death, and the proclamation of his six-year-old son as King of Romania

The King of Romania () or King of the Romanians () was the title of the monarch of the Kingdom of Romania from 1881 until 1947, when the Romanian Workers' Party proclaimed the Romanian People's Republic following Michael I's forced abdication. ...

, former Crown Prince Carol, who had renounced his right of succession two years earlier, proclaimed from his villa near Paris that he planned to claim the throne.

July 22, 1927 (Friday)

* The merger of three clubs (Roman FC, SS Alba-Audace and Fortitudo-Pro Roma SGS) created the Italian soccer football teamA.S. Roma

Associazione Sportiva Roma (''Rome Sport Association''; Italian pronunciation: ) is a professional football club based in Rome, Italy. Founded by a merger in 1927, Roma has participated in the top tier of Italian football for all of its exis ...

, league champion in 1942, 1983 and 2001

July 23, 1927 (Saturday)

* The first regular radio broadcasts inIndia

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

began as the Indian Broadcasting Company

All India Radio (AIR), also known as Akashvani (), is India's state-owned public radio broadcaster. Founded in 1936, it operates under the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting and is one of the two divisions of Prasar Bharati. Headquarte ...

went on the air in Mumbai

Mumbai ( ; ), also known as Bombay ( ; its official name until 1995), is the capital city of the Indian state of Maharashtra. Mumbai is the financial capital and the most populous city proper of India with an estimated population of 12 ...

(Bombay). A second station began operation on August 26 in Kolkata

Kolkata, also known as Calcutta ( its official name until 2001), is the capital and largest city of the Indian state of West Bengal. It lies on the eastern bank of the Hooghly River, west of the border with Bangladesh. It is the primary ...

(Calcutta). The privately owned company was bought in 1930 by the publicly funded Indian Broadcasting Service, now All India Radio.

* Born: Elliot See

Elliot McKay See Jr. (July 23, 1927 – February 28, 1966) was an American engineer, United States naval aviator, naval aviator, test pilot and NASA astronaut.

See received an appointment to the United States Merchant Marine Academy in 1945. H ...

, American astronaut who was killed in a plane crash three months before he was scheduled to have commanded the Gemini 9

Gemini 9A (officially Gemini IX-A) With Gemini IV, NASA changed to Roman numerals for Gemini mission designations. was a 1966 crewed spaceflight in NASA's Gemini program. It was the seventh crewed Gemini flight, the 15th crewed American fligh ...

mission; in Dallas

Dallas () is a city in the U.S. state of Texas and the most populous city in the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex, the List of Texas metropolitan areas, most populous metropolitan area in Texas and the Metropolitan statistical area, fourth-most ...

(d. 1966)

* Died: Brigadier General Reginald Dyer

Colonel Reginald Edward Harry Dyer, (9 October 186423 July 1927) was a British military officer in the Bengal Army and later the newly constituted British Indian Army. His military career began in the regular British Army, but he soon transf ...

, 62, British officer whose troops fired into a crowd of protesters, killing hundreds of unarmed civilians during the Jallianwala Bagh massacre

The Jallianwala Bagh massacre (), also known as the Amritsar massacre, took place on 13 April 1919. A large crowd had gathered at the Jallianwala Bagh in Amritsar, Punjab, British India, during the annual Vaisakhi, Baisakhi fair to protest aga ...

of 1919; from a cerebral hemorrhage

July 24, 1927 (Sunday)

* TheMenin Gate

The Menin Gate (), officially the Menin Gate Memorial to the Missing, is a war memorial in Ypres, Belgium, dedicated to the British and Commonwealth soldiers who were killed in the Ypres Salient of World War I and whose graves are unknown. The m ...

Memorial to the Missing was dedicated in Ypres

Ypres ( ; ; ; ; ) is a Belgian city and municipality in the province of West Flanders. Though

the Dutch name is the official one, the city's French name is most commonly used in English. The municipality comprises the city of Ypres/Ieper ...

, Belgium, as a monument to nearly 90,000 soldiers of the British Empire who went missing in action

Missing in action (MIA) is a casualty (person), casualty classification assigned to combatants, military chaplains, combat medics, and prisoner of war, prisoners of war who are reported missing during wartime or ceasefire. They may have been ...

in the three Battles of Ypres in World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. The names of 54,900 soldiers who were missing in action were engraved on the available space, and another 34,888 were inscribed at a memorial at the nearby Tyne Cot

Tyne Cot Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery and Memorial to the Missing is a Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) burial ground for the dead of World War I in the Ypres Salient on the Western Front. It is the largest cemetery for Commonweal ...

cemetery. ''The Last Post

The "Last Post" is a British and Commonwealth bugle call used at military funerals, and at ceremonies commemorating those who have died in war.

Versions

The "Last Post" is either an A or a B♭ bugle call, primarily within British infantr ...

'' continues to be sounded each evening at 8:00 pm at the monument.

* Died:

** Maurice E. Crumpacker, 40, U.S. Representative for Oregon since 1925, killed himself by leaping into San Francisco Bay

San Francisco Bay (Chochenyo language, Chochenyo: 'ommu) is a large tidal estuary in the United States, U.S. state of California, and gives its name to the San Francisco Bay Area. It is dominated by the cities of San Francisco, California, San ...

** Ryūnosuke Akutagawa

, art name , was a Japanese writer active in the Taishō period in Japan. He is regarded as the "father of the Japanese short story", and Japan's premier literary award, the Akutagawa Prize, is named after him. He took his own life at the age ...

, 35, Japanese short story writer, killed himself with an overdose of barbiturates

July 25, 1927 (Monday)

* Centralized traffic control, now in use on railroads worldwide, was first implemented. The system for remote control of railroad signals from a central location was invented by Sedgwick N. Wight, and first used for a 40-mile stretch of theNew York Central Railroad

The New York Central Railroad was a railroad primarily operating in the Great Lakes region, Great Lakes and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States. The railroad primarily connected New York metropolitan area, gr ...

between Walbridge and Berwick, Ohio

Berwick is an unincorporated community in Seneca Township, Seneca County, Ohio, United States. It is located next to the intersection of East County Road 6 and State Route 587. The community is served by the New Riegel (44853) post office.

Hi ...

.

* July 25, 1927, is the date of the "Tanaka Memorial

The is an alleged Empire of Japan, Japanese strategic planning document from 1927 in which Prime Minister of Japan, Prime Minister Baron Tanaka Giichi laid out a strategy to take over the world for Emperor of Japan, Emperor Hirohito. The authent ...

", purported to be a report by the Prime Minister of Japan

The is the head of government of Japan. The prime minister chairs the Cabinet of Japan and has the ability to select and dismiss its ministers of state. The prime minister also serves as the commander-in-chief of the Japan Self-Defense Force ...

, Baron Tanaka Giichi

Baron was a Japanese general and politician who served as Prime Minister of Japan from 1927 to 1929.

Born to a ''samurai'' family in the Chōshū Domain, Tanaka became an officer in the Imperial Japanese Army and rose through the ranks. He se ...

, to the Emperor Hirohito

, Posthumous name, posthumously honored as , was the 124th emperor of Japan according to the traditional order of succession, from 25 December 1926 until Death and state funeral of Hirohito, his death in 1989. He remains Japan's longest-reigni ...

, summarizing a plan for world conquest that had been devised during a conference from June 27

Events Pre-1600

* 1358 – The Republic of Ragusa is founded.

* 1497 – Cornish rebels Michael An Gof and Thomas Flamank are executed at Tyburn, London, England.

* 1499 – Amerigo Vespucci sights what is now Amapá State in B ...

to July 7. "The document," notes one observer, "has never been found and is generally assumed to have been a Chinese forgery, if it ever existed."

July 26, 1927 (Tuesday)

* The Central Executive Committee of theKuomintang

The Kuomintang (KMT) is a major political party in the Republic of China (Taiwan). It was the one party state, sole ruling party of the country Republic of China (1912-1949), during its rule from 1927 to 1949 in Mainland China until Retreat ...

, China's ruling Nationalist Party, passed a resolution expelling Communists from its membership and calling for the outlawing of the Chinese Communist Party

The Communist Party of China (CPC), also translated into English as Chinese Communist Party (CCP), is the founding and One-party state, sole ruling party of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Founded in 1921, the CCP emerged victorious in the ...

.

* The Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party met to plan what would become the Nanchang uprising; present at the meeting was V. K. Bliuker, a Soviet representative for Comintern

The Communist International, abbreviated as Comintern and also known as the Third International, was a political international which existed from 1919 to 1943 and advocated world communism. Emerging from the collapse of the Second Internatio ...

, the Communist International organization, which was deciding whether to continue its support of Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; traditionally Romanization of Chinese, romanised as Mao Tse-tung. (26December 18939September 1976) was a Chinese politician, revolutionary, and political theorist who founded the People's Republic of China (PRC) in ...

as the person to lead the spread of communism to China.

* French Army General Georges Catroux