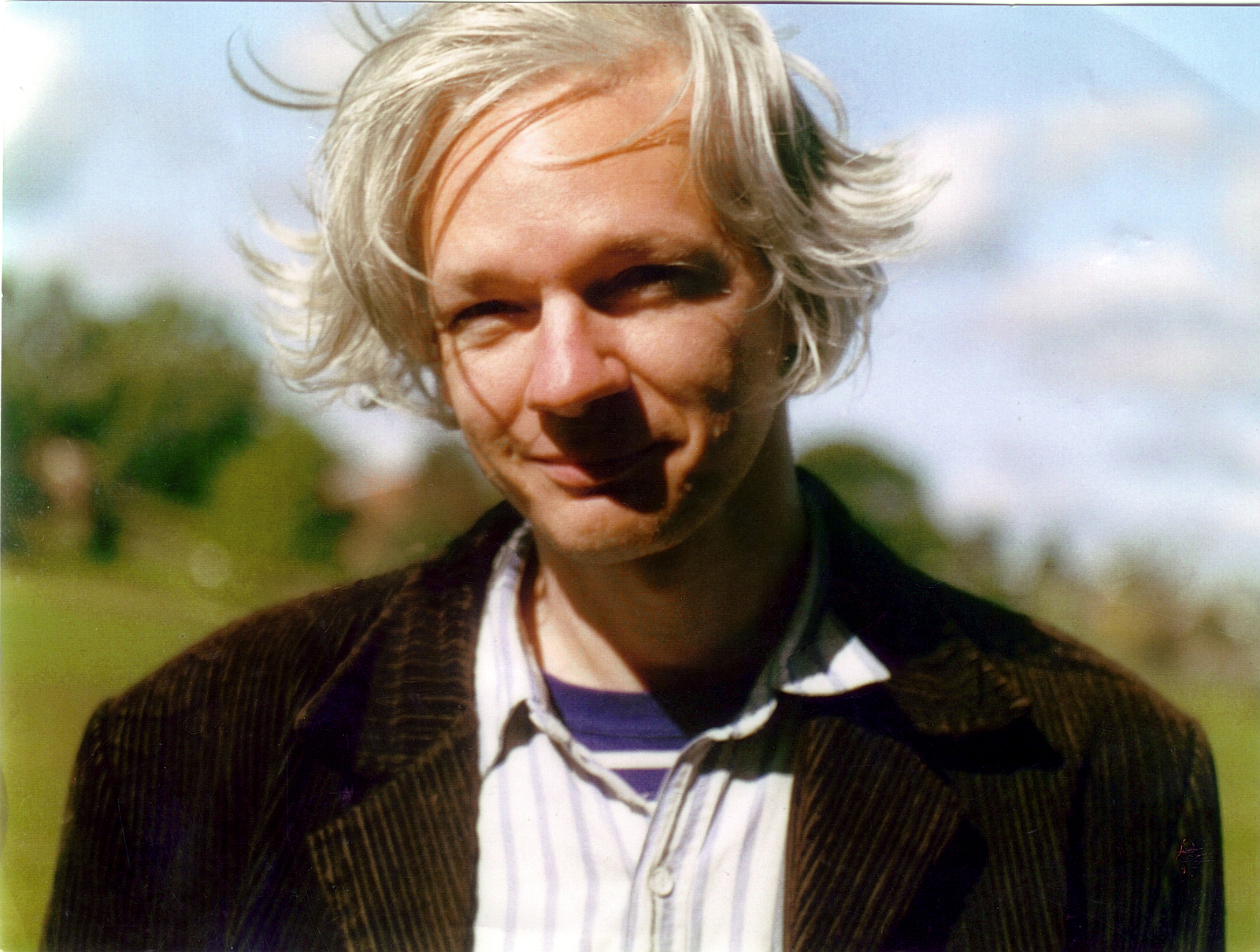

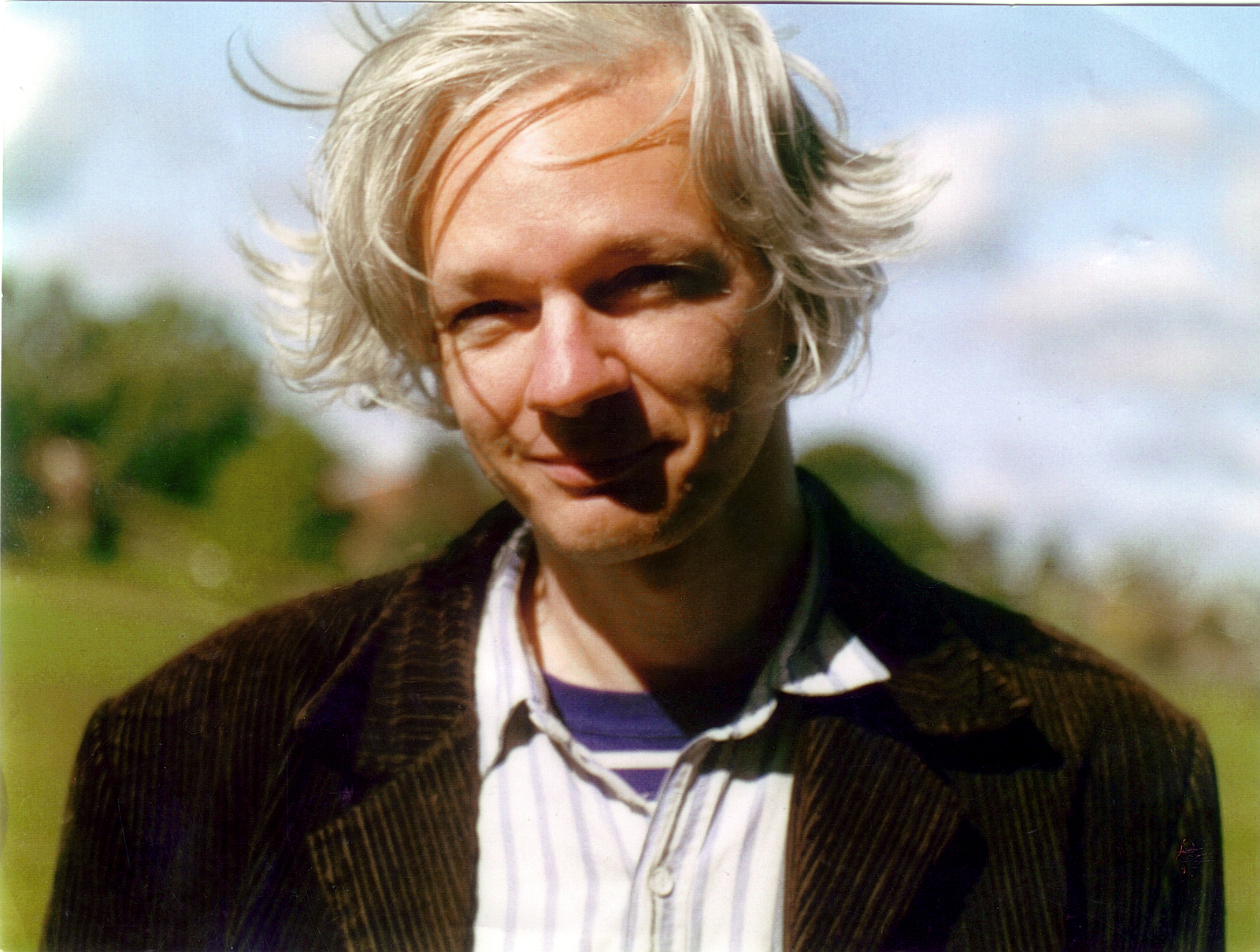

Julian Paul Assange ( ; Hawkins; born 3 July 1971) is an Australian editor, publisher, and activist who founded

WikiLeaks

WikiLeaks () is a non-profit media organisation and publisher of leaked documents. It is funded by donations and media partnerships. It has published classified documents and other media provided by anonymous sources. It was founded in 2006 by ...

in 2006. He came to international attention in 2010 after WikiLeaks published a series of

leaks from

Chelsea Manning

Chelsea Elizabeth Manning (born Bradley Edward Manning, December 17, 1987) is an American activist and whistleblower. She is a former United States Army soldier who was convicted by court-martial in July 2013 of violations of the Espionage ...

, a

United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary Land warfare, land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of th ...

intelligence analyst:

footage of a U.S. airstrike in

Baghdad

Baghdad ( or ; , ) is the capital and List of largest cities of Iraq, largest city of Iraq, located along the Tigris in the central part of the country. With a population exceeding 7 million, it ranks among the List of largest cities in the A ...

, U.S. military logs from the

Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. It is bordered by Pakistan to the Durand Line, east and south, Iran to the Afghanistan–Iran borde ...

and

Iraq

Iraq, officially the Republic of Iraq, is a country in West Asia. It is bordered by Saudi Arabia to Iraq–Saudi Arabia border, the south, Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq border, the east, the Persian Gulf and ...

wars, and

U.S. diplomatic cables. Assange has won over two dozen awards for publishing and human rights activism.

Assange was raised in various places around Australia until his family settled in

Melbourne

Melbourne ( , ; Boonwurrung language, Boonwurrung/ or ) is the List of Australian capital cities, capital and List of cities in Australia by population, most populous city of the States and territories of Australia, Australian state of Victori ...

in his middle teens. He became involved in the

hacker community and was convicted for

hacking in 1996.

Following the establishment of WikiLeaks, Assange was its editor when it published the

Bank Julius Baer documents, footage of the

2008 Tibetan unrest

The 2008 Tibetan unrest, also referred to as the 2008 Tibetan uprising in Tibetan media, was a series of protests and demonstrations over the Government of China, Chinese government's treatment and persecution of Tibetan people, Tibetans. Protes ...

, and a report on political killings in Kenya with ''

The Sunday Times

''The Sunday Times'' is a British Sunday newspaper whose circulation makes it the largest in Britain's quality press market category. It was founded in 1821 as ''The New Observer''. It is published by Times Newspapers Ltd, a subsidiary of N ...

''. Publication of the leaks from Manning started in February 2010.

In November 2010 Sweden wished to question Assange in an unrelated police investigation and

sought to extradite him from the UK. In June 2012, Assange breached his

bail

Bail is a set of pre-trial restrictions that are imposed on a suspect to ensure that they will not hamper the judicial process. Court bail may be offered to secure the conditional release of a defendant with the promise to appear in court when ...

and took refuge in the

Embassy of Ecuador in London. He was granted

asylum by

Ecuador

Ecuador, officially the Republic of Ecuador, is a country in northwestern South America, bordered by Colombia on the north, Peru on the east and south, and the Pacific Ocean on the west. It also includes the Galápagos Province which contain ...

in August 2012 on the grounds of

political persecution and fears he might be extradited to the United States. Swedish prosecutors dropped their investigation in 2019.

In 2013, Assange launched the

WikiLeaks Party and unsuccessfully stood for the

Australian Senate

The Senate is the upper house of the Bicameralism, bicameral Parliament of Australia, the lower house being the Australian House of Representatives, House of Representatives.

The powers, role and composition of the Senate are set out in Chap ...

while remaining in Ecuador’s embassy in London.

Also while in the embassy, the

Mueller report suggested that he interfered with the US presidential election; specifically he was alleged to have conspired with Russian agents to elect

Donald Trump

Donald John Trump (born June 14, 1946) is an American politician, media personality, and businessman who is the 47th president of the United States. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he served as the 45 ...

.

On 11 April 2019, Assange's asylum was withdrawn following a series of disputes with Ecuadorian authorities; the police were invited into the embassy and he was arrested.

He was found guilty of breaching the

United Kingdom Bail Act and sentenced to 50 weeks in prison.

The

U.S. government unsealed

an indictment charging Assange with

conspiracy

A conspiracy, also known as a plot, ploy, or scheme, is a secret plan or agreement between people (called conspirers or conspirators) for an unlawful or harmful purpose, such as murder, treason, or corruption, especially with a political motivat ...

to

commit computer intrusion related to the leaks provided by Manning. In May 2019 and June 2020, the U.S. government unsealed new indictments against Assange, charging him with violating the

Espionage Act of 1917 and alleging he had conspired with hackers.

The key witness for the new indictment, whom the justice department had given immunity in return for giving evidence, stated in 2021 that he had fabricated his testimony. Critics have described these charges as an unprecedented challenge to

press freedom

Freedom of the press or freedom of the media is the fundamental principle that communication and expression through various media, including printed and electronic media, especially published materials, should be considered a right to be exerc ...

with potential implications for

investigative journalism

Investigative journalism is a form of journalism in which reporters deeply investigate a single topic of interest, such as serious crimes, racial injustice, political corruption, or corporate wrongdoing. An investigative journalist may spend m ...

worldwide. Assange was incarcerated in

HM Prison Belmarsh in

London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

from April 2019 to June 2024, as the U.S. government's extradition effort was contested in the UK courts.

In 2022, the incoming Australian Labor government of

Anthony Albanese

Anthony Norman Albanese ( or ; born 2 March 1963) is an Australian politician serving as the 31st and current prime minister of Australia since 2022. He has been the Leaders of the Australian Labor Party#Leader, leader of the Labor Party si ...

reversed the position of previous governments and began to lobby for Assange's release. In 2024, following a

High Court ruling that granted Assange a full appeal to extradition, Assange and his lawyers negotiated a deal with US prosecutors. Assange agreed to a

plea deal in which he pleaded guilty in

Saipan

Saipan () is the largest island and capital of the Northern Mariana Islands, an unincorporated Territories of the United States, territory of the United States in the western Pacific Ocean. According to 2020 estimates by the United States Cens ...

to an Espionage Act charge of conspiring to obtain and disclose classified U.S. national defence documents in return for a sentence of

time served

In typical criminal law, time served is an informal term that describes the duration of pretrial detention (remand), the time period between when a defendant is arrested and when they are convicted. Time served does not include time served ...

.

Following the hearing Assange flew to Australia, arriving on 26 June.

Early life

Assange was born Julian Paul Hawkins on 3 July 1971 in

Townsville

The City of Townsville is a city on the north-eastern coast of Queensland, Australia. With a population of 201,313 as of 2024, it is the largest settlement in North Queensland and Northern Australia (specifically, the parts of Australia north of ...

, Queensland,

to Christine Ann Hawkins, a

visual artist

The visual arts are art forms such as painting, drawing, printmaking, sculpture, ceramics (art), ceramics, photography, video, image, filmmaking, design, crafts, and architecture. Many artistic disciplines such as performing arts, conceptual a ...

,

and

John Shipton, an

anti-war activist and builder.

The couple separated before their son was born.

When Julian was a year old his mother married Brett Assange,

an actor with whom she ran a small theatre company and whom Julian Assange regards as his father (choosing Assange as his surname).

Christine and Brett Assange divorced around 1979. Christine then became involved with Leif Meynell, also known as Leif Hamilton, whom Julian Assange later described as "a member of an Australian cult" called

The Family. Meynell and Christine Assange separated in 1982.

Julian Assange lived in more than thirty Australian towns and cities during his childhood.

He attended several schools, including

Goolmangar Primary School in

New South Wales

New South Wales (commonly abbreviated as NSW) is a States and territories of Australia, state on the Eastern states of Australia, east coast of :Australia. It borders Queensland to the north, Victoria (state), Victoria to the south, and South ...

(1979–1983)

and

Townsville State High School in Queensland as well as being schooled at home.

In his mid-teens, he settled with his mother and half-brother in

Melbourne

Melbourne ( , ; Boonwurrung language, Boonwurrung/ or ) is the List of Australian capital cities, capital and List of cities in Australia by population, most populous city of the States and territories of Australia, Australian state of Victori ...

. He moved in with his girlfriend at age 17.

Assange studied

programming,

mathematics

Mathematics is a field of study that discovers and organizes methods, Mathematical theory, theories and theorems that are developed and Mathematical proof, proved for the needs of empirical sciences and mathematics itself. There are many ar ...

, and

physics

Physics is the scientific study of matter, its Elementary particle, fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge whi ...

at

Central Queensland University (1994) and the

University of Melbourne

The University of Melbourne (colloquially known as Melbourne University) is a public university, public research university located in Melbourne, Australia. Founded in 1853, it is Australia's second oldest university and the oldest in the state ...

(2003–2006),

but did not complete a degree.

Assange started the Puzzle Hunt tradition at the University of Melbourne, which was modelled after the

MIT Mystery Hunt.

He was involved in the Melbourne

rave

A rave (from the verb: '' to rave'') is a dance party at a warehouse, club, or other public or private venue, typically featuring performances by DJs playing electronic dance music. The style is most associated with the early 1990s dance mus ...

scene, and assisted in installing an internet kiosk at

Ollie Olsen's

club night called "Psychic Harmony", which was held at Dream nightclub in Carlton (later called Illusion). Assange's nickname at the raves was "Prof".

Hacking

By 1987, aged 16, Assange had become a skilled

hacker

A hacker is a person skilled in information technology who achieves goals and solves problems by non-standard means. The term has become associated in popular culture with a security hackersomeone with knowledge of bug (computing), bugs or exp ...

under the name ''Mendax'',

taken from

Horace

Quintus Horatius Flaccus (; 8 December 65 BC – 27 November 8 BC), Suetonius, Life of Horace commonly known in the English-speaking world as Horace (), was the leading Roman lyric poet during the time of Augustus (also known as Octavian). Th ...

's ''splendide mendax'' (from Latin, "nobly untruthful").

Around this time, the police raided his mother's home and confiscated his equipment. According to Assange, "it involved some dodgy character who was alleging that we had stolen five hundred thousand dollars from Citibank". Ultimately, no charges were raised and his equipment was returned, but Assange "decided that it might be wise to be a bit more discreet".

In 1988 Assange used

social engineering to get the password to Australia's

Overseas Telecommunications Commission's mainframes.

Assange had a self-imposed set of ethics: he did not damage or

crash systems or data he hacked, and he shared information.

''

The Sydney Morning Herald

''The Sydney Morning Herald'' (''SMH'') is a daily Tabloid (newspaper format), tabloid newspaper published in Sydney, Australia, and owned by Nine Entertainment. Founded in 1831 as the ''Sydney Herald'', the ''Herald'' is the oldest continuous ...

'' later opined that he had become one of Australia's "most notorious hackers",

and ''

The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in Manchester in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'' and changed its name in 1959, followed by a move to London. Along with its sister paper, ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardi ...

'' said that by 1991 he was "probably Australia's most accomplished hacker".

Assange's official biography on

WikiLeaks

WikiLeaks () is a non-profit media organisation and publisher of leaked documents. It is funded by donations and media partnerships. It has published classified documents and other media provided by anonymous sources. It was founded in 2006 by ...

called him Australia's "most famous ethical computer hacker",

and the earliest version said he "hacked thousands of systems, including

the Pentagon

The Pentagon is the headquarters building of the United States Department of Defense, in Arlington County, Virginia, across the Potomac River from Washington, D.C. The building was constructed on an accelerated schedule during World War II. As ...

" when he was younger.

He and two others, known as "Trax" and "Prime Suspect", formed a

hacking group called "the International Subversives".

According to

NPR,

David Leigh, and

Luke Harding

Luke Daniel Harding (born 21 April 1968) is a British journalist who is a foreign correspondent for ''The Guardian''. He is known for his coverage of Russia under Vladimir Putin, WikiLeaks and Edward Snowden.

He was based in Russia for ''Th ...

, Assange may have been involved in the

WANK hack at

NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the federal government of the United States, US federal government responsible for the United States ...

in 1989, but this has never been proven.

Assange called it "the origin of

hacktivism", and the Swedish television documentary ''WikiRebels'', which was made with Assange's cooperation, also hinted he was involved.

In mid-1991 the three hackers began targeting

MILNET,

a data network used by the US military, where Assange found reports he said showed the US military was hacking other parts of itself.

Assange found a

backdoor and later said they "had control over it for two years."

In 2012, Ken Day, the former head of the Australian Federal Police computer crime team, said that there had been no evidence the International Subversives had hacked MILNET. In response to Assange's statements about accessing MILNET, Day said that "Assange may still be liable to prosecution for that act—if it can be proved."

Assange wrote a program called Sycophant that allowed the International Subversives to conduct "massive attacks on the US military".

The International Subversives regularly hacked into systems belonging to a "who's who of the U.S.

military-industrial complex"

and the network of

Australia National University.

Assange later said he had been "a famous teenage hacker in Australia, and I've been reading generals' emails since I was 17". Assange has attributed his motivation to this experience with power.

Arrest and trial

The

Australian Federal Police

The Australian Federal Police (AFP) is the principal Federal police, federal law enforcement agency of the Australian Government responsible for investigating Crime in Australia, crime and protecting the national security of the Commonwealth ...

(AFP) set up an investigation called Operation Weather targeting The International Subversives.

In September 1991, Assange was discovered hacking into the Melbourne master terminal of

Nortel

Nortel Networks Corporation (Nortel), formerly Northern Telecom Limited, was a Canadian Multinational corporation, multinational telecommunications and data networking equipment manufacturer headquartered in Ottawa, Ontario. It was founded in ...

, a Canadian

multinational telecommunications corporation.

Another member of the International Subversives turned himself and the others in,

and the AFP tapped Assange's phone line (he was using a

modem

The Democratic Movement (, ; MoDem ) is a centre to centre-right political party in France, whose main ideological trends are liberalism and Christian democracy, and that is characterised by a strong pro-Europeanist stance. MoDem was establis ...

) and raided his home at the end of October.

The earliest detailed reports about Assange are 1990s Australian press reports on him and print and TV news of his trial.

He was charged in 1994 with 31 counts of crimes related to hacking, including defrauding

Telecom Australia, fraudulent use of a telecommunications network, obtaining access to information, erasing data, and altering data.

According to Assange, the only data he inserted or deleted was his program.

The prosecution argued that a magazine written by the International Subversives would encourage others to hack, calling it a "hacker's manual" and alleging that Assange and the other hackers posted information online about how to hack into computers they had accessed.

His trial date was set in May 1995 and his case was presented to the

Supreme Court of Victoria

The Supreme Court of Victoria is the highest court in the Australian state of Victoria. Founded in 1852, it is a superior court of common law and equity, with unlimited and inherent jurisdiction within the state.

The Supreme Court compri ...

, but the court did not take the case, sending it back to the County Court. Assange fell into a deep depression while waiting for his trial and checked himself into a

psychiatric hospital

A psychiatric hospital, also known as a mental health hospital, a behavioral health hospital, or an asylum is a specialized medical facility that focuses on the treatment of severe Mental disorder, mental disorders. These institutions cater t ...

and then spent six months sleeping in the wilderness around Melbourne.

In December 1996, facing a theoretical sentence of 290 years in prison,

he struck a

plea deal and

pleaded guilty

In law, a plea is a defendant's response to a criminal charge. A defendant may plead guilty or not guilty. Depending on jurisdiction, additional pleas may be available, including '' nolo contendere'' (no contest), no case to answer (in the ...

to 24 hacking charges.

The judge called the charges "quite serious" and initially thought a jail term would be necessary

but ultimately sentenced Assange to a fine of A$2,100 and released him on a A$5,000

good behaviour bond because of his disrupted childhood and the absence of malicious or mercenary intent.

After his sentencing, Assange told the judge that he had "been misled by the prosecution in terms of the charges" and "a great misjustice has been done". The judge told Assange "you have pleaded guilty, the proceedings are over" and advised him to be quiet.

Assange has described the trial as a formative period and according to ''

The New Republic

''The New Republic'' (often abbreviated as ''TNR'') is an American magazine focused on domestic politics, news, culture, and the arts from a left-wing perspective. It publishes ten print magazines a year and a daily online platform. ''The New Y ...

'', "the experience set him on the intellectual path" leading him to found WikiLeaks.

In 1993, Assange provided technical advice and support to help the

Victoria Police

Victoria Police is the primary law enforcement agency of the Australian States and territories of Australia, state of Victoria (Australia), Victoria. It was formed in 1853 and currently operates under the ''Victoria Police Act 2013''.

, Victor ...

Child Exploitation Unit to prosecute individuals responsible for publishing and distributing child pornography.

His lawyers said he was pleased to assist, emphasising that he received no benefit for this and was not an informer. His role in helping the police was discussed during his 1996 sentencing on computer hacking charges. According to his mother, Assange also helped police "remove a book on the Internet about how to build a bomb".

Cypherpunks and programming

In the same year, he took over running one of the first public

Internet service provider

An Internet service provider (ISP) is an organization that provides a myriad of services related to accessing, using, managing, or participating in the Internet. ISPs can be organized in various forms, such as commercial, community-owned, no ...

s in Australia, Suburbia Public Access Network, when its original owner, Mark Dorset, moved to

Sydney

Sydney is the capital city of the States and territories of Australia, state of New South Wales and the List of cities in Australia by population, most populous city in Australia. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Syd ...

.

He joined the

cypherpunk mailing list in late 1993 or early 1994.

According to

Robert Manne, Assange's main political focus at this time seems to have been the information-sharing possibilities created by the internet and its threats.

He began programming in 1994, authoring or co-authoring network

and encryption programs, such as the Rubberhose

deniable encryption

In cryptography and steganography, plausibly deniable encryption describes encryption techniques where the existence of an encrypted file or message is deniable in the sense that an adversary cannot prove that the plaintext data exists.

The use ...

system.

Assange wrote other programs to make the Internet more accessible

and developed cyber warfare systems like the Strobe

port scanner which could look for weaknesses in hundreds of thousands of computers at any one time.

During this period of time he also moderated the AUCRYPTO forum,

ran a website that gave advice on computer security to 5,000 subscribers in 1996,

and contributed research to

Suelette Dreyfus's ''

Underground'' (1997), a book about Australian hackers including the International Subversives.

According to Assange, he "deliberately minimized" his role in ''Underground'' so it could "pull in the whole community".

In 1998 he co-founded with Trax the "

network intrusion detection technologies" company Earthmen Technology which developed

Linux kernel

The Linux kernel is a Free and open-source software, free and open source Unix-like kernel (operating system), kernel that is used in many computer systems worldwide. The kernel was created by Linus Torvalds in 1991 and was soon adopted as the k ...

hacking tools.

During this period he also earned a sizeable income working as a consultant for large corporations.

In October 1998, Assange decided to visit friends and announced on the

cypherpunks mailing list he would be "hopscotching" through

Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

,

Mongolia

Mongolia is a landlocked country in East Asia, bordered by Russia to the north and China to the south and southeast. It covers an area of , with a population of 3.5 million, making it the world's List of countries and dependencies by po ...

,

China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

,

Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

and

Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the Europe, European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural and socio-economic connotations. Its eastern boundary is marked by the Ural Mountain ...

.

Leaks

According to Assange, in the 1990s, he and Suburbia Public Access Network facilitated leaks for activists and lawyers. Assange told Suelette Dreyfus that he had "acted as a conduit for leaked documents" when fighting local corruption.

While awaiting trial and trying to get custody of his son, Assange and his mother formed the activist organisation Parent Inquiry Into Child Protection.

An article in the Canadian magazine ''

Maclean's

''Maclean's'' is a Canadian magazine founded in 1905 which reports on Canadian issues such as politics, pop culture, trends and current events. Its founder, publisher John Bayne Maclean, established the magazine to provide a uniquely Canadian ...

'' later referred to it as "a low-tech rehearsal for WikiLeaks".

The group used the

Australian Freedom of Information Act to obtain documents, and secretly recorded meetings with Health and Community Services. The group also used flyers to encourage insiders to anonymously come forward, and according to Assange they "had moles who were inside dissidents." An insider leaked a key internal departmental manual about the rules for custody disputes to the group.

In November 1996 Assange sent an email to lists he had created and mentioned a "LEAKS" project.

Assange stated that he registered the domain "leaks.org" in 1999, but did not use it.

He publicised a patent granted to the

National Security Agency

The National Security Agency (NSA) is an intelligence agency of the United States Department of Defense, under the authority of the director of national intelligence (DNI). The NSA is responsible for global monitoring, collection, and proces ...

in August 1999, for voice-data harvesting technology saying "This patent should worry people. Everyone's overseas phone calls are or may soon be tapped, transcribed and archived in the bowels of an unaccountable foreign spy agency."

WikiLeaks

Early publications

Assange and a group of other dissidents, mathematicians and activists established

WikiLeaks

WikiLeaks () is a non-profit media organisation and publisher of leaked documents. It is funded by donations and media partnerships. It has published classified documents and other media provided by anonymous sources. It was founded in 2006 by ...

in 2006.

Assange became a member of its advisory board. From 2007 to 2010, Assange travelled continuously on WikiLeaks business, visiting Africa, Asia, Europe, and North America.

In December 2006, the month WikiLeaks posted its first leak, Assange published a five-page essay that outlined the "thought experiment" behind the WikiLeaks strategy: use leaks to force organisations to reduce levels of abuse and dishonesty or pay "secrecy tax" to be secret but inefficient. Assange explained:

Assange found key supporters at the

Chaos Computer Club

The Chaos Computer Club (CCC) is Europe's largest association of Hacker (computer security), hackers with 7,700 registered members. Founded in 1981, the association is incorporated as an ''eingetragener Verein'' in Germany, with local chapters ...

conference in Berlin in December 2007, including

Daniel Domscheit-Berg and

Jacob Appelbaum

Jacob Appelbaum (born April 1, 1983) is an American independent journalist, computer security researcher, artist, Hacking (innovation), hacker and teacher. Appelbaum, who earned his PhD from the Eindhoven University of Technology, first became not ...

and the Swedish hosting company

PRQ.

During this period, Assange was WikiLeaks' editor-in-chief and one of four permanent staff.

The organisation maintained a larger group of volunteers, and Assange relied upon networks of others with expertise.

The organisation published internet censorship lists,

leaks, and classified media from anonymous

sources

Source may refer to:

Research

* Historical document

* Historical source

* Source (intelligence) or sub source, typically a confidential provider of non open-source intelligence

* Source (journalism), a person, publication, publishing institute ...

. The publications include revelations about

drone strikes in Yemen, corruption across the

Arab world

The Arab world ( '), formally the Arab homeland ( '), also known as the Arab nation ( '), the Arabsphere, or the Arab states, comprises a large group of countries, mainly located in West Asia and North Africa. While the majority of people in ...

,

extrajudicial executions by Kenyan police,

2008 Tibetan unrest

The 2008 Tibetan unrest, also referred to as the 2008 Tibetan uprising in Tibetan media, was a series of protests and demonstrations over the Government of China, Chinese government's treatment and persecution of Tibetan people, Tibetans. Protes ...

in China, and the

"Petrogate" oil scandal in Peru. From its inception, the website had a significant impact on political news in a large number of countries and across a wide range of issues.

From its inception, WikiLeaks sought to engage with the established professional media. It had good relations with parts of the German and British press. A collaboration with the ''

Sunday Times

''The Sunday Times'' is a British Sunday newspaper whose circulation makes it the largest in Britain's quality press market category. It was founded in 1821 as ''The New Observer''. It is published by Times Newspapers Ltd, a subsidiary of N ...

'' journalist

Jon Swain

Jon Anketell Brewer Swain (born 1948) is a British journalist and writer.

Swain's book ''River of Time: A Memoir of Vietnam ''chronicles his experiences from 1970 to 1975 during the Vietnam War, war in Indochina, including the Fall of Phnom Pen ...

on a report on political killings in Kenya led to increased public recognition of the WikiLeaks publication, and this collaboration won Assange the 2009

Amnesty International

Amnesty International (also referred to as Amnesty or AI) is an international non-governmental organization focused on human rights, with its headquarters in the United Kingdom. The organization says that it has more than ten million members a ...

New Media Award.

[ Assange said that six men with guns tried to attack the compound that he slept at in Kenya after the report was published, but were scared away when a guard shouted.] WikiLeaks' international profile increased in 2008 when a Swiss bank, Bank Julius Baer, tried via a Californian court injunction to prevent the site's publication of bank records. Assange commented that financial institutions ordinarily "operate outside the rule of law", and he received extensive legal support from free-speech and civil rights groups. Bank Julius Baer's attempt to prevent the publication via injunction backfired. As a result of the

WikiLeaks' international profile increased in 2008 when a Swiss bank, Bank Julius Baer, tried via a Californian court injunction to prevent the site's publication of bank records. Assange commented that financial institutions ordinarily "operate outside the rule of law", and he received extensive legal support from free-speech and civil rights groups. Bank Julius Baer's attempt to prevent the publication via injunction backfired. As a result of the Streisand effect

The Streisand effect is an unintended consequences, unintended consequence of attempts to hide, remove, or Censorship, censor information, where the effort instead increases public awareness of the information.

The term was coined in 2005 by ...

, the publicity drew global attention to WikiLeaks and the bank documents.[

By 2009 WikiLeaks had succeeded in Assange's intentions to expose the powerful, publish material beyond the control of states, and attract media support for its advocacy of ]freedom of speech

Freedom of speech is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or a community to articulate their opinions and ideas without fear of retaliation, censorship, or legal sanction. The rights, right to freedom of expression has been r ...

, though not as much as he hoped; his goal of crowd-sourcing analysis of the documents was unsuccessful and few of the leaks attracted mainstream media attention.[

In July 2009 Assange released through Wikileaks the full report of a commission of inquiry, set up by the British ]Foreign and Commonwealth Office

The Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) is the ministry of foreign affairs and a Departments of the Government of the United Kingdom, ministerial department of the government of the United Kingdom.

The office was created on 2 ...

, into corruption in the Turks and Caicos Islands

The Turks and Caicos Islands (abbreviated TCI; and ) are a British Overseas Territory consisting of the larger Caicos Islands and smaller Turks Islands, two groups of tropical islands in the Lucayan Archipelago of the Atlantic Ocean and no ...

.[

]

Manning leaks

The Cablegate as well as Iraq and Afghan War releases impacted diplomacy and public opinion globally, with responses varying by region.

Collateral murder video

In April 2010, WikiLeaks released video footage of the 12 July 2007, Baghdad airstrike, that have been regarded by several debaters as evidence of war crime

A war crime is a violation of the laws of war that gives rise to individual criminal responsibility for actions by combatants in action, such as intentionally killing civilians or intentionally killing prisoners of war, torture, taking hostage ...

s committed by the U.S. military.[ The news agency ]Reuters

Reuters ( ) is a news agency owned by Thomson Reuters. It employs around 2,500 journalists and 600 photojournalists in about 200 locations worldwide writing in 16 languages. Reuters is one of the largest news agencies in the world.

The agency ...

had earlier requested the footage through a US Freedom of Information Act request, but the request was denied. Assange and others worked for a week to break the U.S. military's encryption of the video, which they titled ''Collateral Murder'' and which Assange first presented at the U.S. National Press Club.Reuters

Reuters ( ) is a news agency owned by Thomson Reuters. It employs around 2,500 journalists and 600 photojournalists in about 200 locations worldwide writing in 16 languages. Reuters is one of the largest news agencies in the world.

The agency ...

journalists Namir Noor-Eldeen

Namir Noor-Eldeen (; September 1, 1984 – July 12, 2007) was an Iraqi war photographer for Reuters. Noor-Eldeen, his assistant, Saeed Chmagh, as well as eight others were fired upon by U.S. military forces in the New Baghdad district of ...

and his assistant Saeed Chmagh.

Iraq and Afghan War logs

WikiLeaks published the Afghan War logs in July 2010. It was described by the ''New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'' as "a six-year archive of classified military documents hat

A hat is a Headgear, head covering which is worn for various reasons, including protection against weather conditions, ceremonial reasons such as university graduation, religious reasons, safety, or as a fashion accessory. Hats which incorpor ...

offers an unvarnished and grim picture of the Afghan war".

In October 2010 WikiLeaks published the Iraq War logs, a collection of 391,832 United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary Land warfare, land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of th ...

field reports from the Iraq War

The Iraq War (), also referred to as the Second Gulf War, was a prolonged conflict in Iraq lasting from 2003 to 2011. It began with 2003 invasion of Iraq, the invasion by a Multi-National Force – Iraq, United States-led coalition, which ...

covering from 2004 to 2009. Assange said that he hoped the publication would "correct some of that attack on the truth that occurred before the war, during the war, and which has continued after the war".Luke Harding

Luke Daniel Harding (born 21 April 1968) is a British journalist who is a foreign correspondent for ''The Guardian''. He is known for his coverage of Russia under Vladimir Putin, WikiLeaks and Edward Snowden.

He was based in Russia for ''Th ...

they had to persuade Assange to redact the names of Afghani informants, expressing their fear that they could be killed if exposed. In their book '' WikiLeaks: Inside Julian Assange's War on Secrecy'' they say Declan Walsh heard Assange say at a dinner when asked about redaction "Well, they're informants, so if they get killed, they've got it coming to them. They deserve it."

Assange denies making this statement; speaking on PBS Frontline about the accusations he said "It is absolutely right to name names. It is not necessarily right to name every name." John Goetz of Der Spiegel, who was also at the dinner, says that Assange did not make such a statement.

Release of US diplomatic cables

In November 2010 WikiLeaks published a quarter of a million U.S. diplomatic cables, known as the "Cablegate" files. WikiLeaks initially worked with established Western media organisations, and later with smaller regional media organisations while also publishing the cables upon which their reporting was based.United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

and other world leaders,Arab Spring

The Arab Spring () was a series of Nonviolent resistance, anti-government protests, Rebellion, uprisings, and Insurgency, armed rebellions that spread across much of the Arab world in the early 2010s. It began Tunisian revolution, in Tunisia ...

.Chelsea Manning

Chelsea Elizabeth Manning (born Bradley Edward Manning, December 17, 1987) is an American activist and whistleblower. She is a former United States Army soldier who was convicted by court-martial in July 2013 of violations of the Espionage ...

by text chat while she was submitting leaks to WikiLeaks.Adrian Lamo

Adrián Alfonso Lamo Atwood (February 20, 1981 – March 14, 2018) was an American threat analyst and Hacker (computer security), hacker. Lamo first gained media attention for breaking into several high-profile computer networks, including those ...

.

= Release of unredacted cables

=

In 2011 a series of events compromised the security of a WikiLeaks file containing the leaked US diplomatic cables. In August 2010, Assange gave '' Guardian'' journalist David Leigh an encryption key

A key in cryptography is a piece of information, usually a string of numbers or letters that are stored in a file, which, when processed through a cryptographic algorithm, can encode or decode cryptographic data. Based on the used method, the key ...

and a URL where he could locate the full file. In February 2011 David Leigh and Luke Harding

Luke Daniel Harding (born 21 April 1968) is a British journalist who is a foreign correspondent for ''The Guardian''. He is known for his coverage of Russia under Vladimir Putin, WikiLeaks and Edward Snowden.

He was based in Russia for ''Th ...

of ''The Guardian'' published the encryption key in their book '' WikiLeaks: Inside Julian Assange's War on Secrecy''. Leigh said he believed the key was a temporary one that would expire within days. WikiLeaks supporters disseminated the encrypted files to mirror site

Mirror sites or mirrors are replicas of other websites. The concept of mirroring applies to network services accessible through any protocol, such as HTTP or FTP. Such sites have different URLs than the original site, but host identical or near-i ...

s in December 2010 after WikiLeaks experienced cyber-attacks. When WikiLeaks learned what had happened it notified the US State Department

The United States Department of State (DOS), or simply the State Department, is an executive department of the U.S. federal government responsible for the country's foreign policy and relations. Equivalent to the ministry of foreign affairs o ...

. On 25 August 2011, the German magazine '' Der Freitag'' published an article giving details which enabled people to piece the information together. On 1 September 2011, WikiLeaks announced they would make the unredacted cables public and searchable.[. Guardian. Retrieved 5 September 2011.]

''The Guardian'' wrote that the decision to publish the cables was made by Assange alone, a decision that it and its four previous media partners condemned.Glenn Greenwald

Glenn Edward Greenwald (born March 6, 1967) is an American journalist, author, and former lawyer.

In 1996, Greenwald founded a law firm concentrating on First Amendment to the United States Constitution, First Amendment litigation. He began blo ...

wrote that "WikiLeaks decided—quite reasonably—that the best and safest course was to release all the cables in full, so that not only the world's intelligence agencies but everyone had them, so that steps could be taken to protect the sources and so that the information in them was equally available".

The US established an Information Review Task Force (IRTF) to investigate the impact of WikiLeaks' publications. It involved as many as 125 people working over 10 months. According to IRTF reports, the leaks could cause "serious damage" and put foreign US sources at risk. The head of the IRTF, Brigadier General Robert Carr, testified under questioning at Chelsea Manning's sentencing hearing that the task force had found no examples of anyone who had lost their life due to WikiLeaks' publication of the documents.[ John Young, the owner and operator of the website Cryptome, testified at Assange's extradition hearing that the unredacted cables were published by Cryptome on 1 September, the day before WikiLeaks, and they remain on the Cryptome site. Lawyers for Assange gave evidence it said would show that Assange was careful to protect lives.

]

Later activities

In December 2010 PostFinance said it was closing Assange's Swiss bank account because he "provided false information regarding his place of residence during the account opening process" but that there would be "no criminal consequences" for misleading authorities. WikiLeaks said the account was used to "donate directly to the Julian Assange and other WikiLeaks Staff Defence Fund" and said the closing was part of a banking blockade against WikiLeaks.

According to the Associated Press

The Associated Press (AP) is an American not-for-profit organization, not-for-profit news agency headquartered in New York City.

Founded in 1846, it operates as a cooperative, unincorporated association, and produces news reports that are dist ...

, leaked documents from WikiLeaks include an unsigned letter from Julian Assange authorising Israel Shamir to seek a Russian visa on his behalf in 2010. WikiLeaks said Assange never applied for the visa or wrote the letter. According to the New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

, in November 2010 "Assange had mused about seeking refuge in Russia", and Russia issued Assange a visa in January 2011.

According to Andrew O'Hagan, during the 2011 Egyptian revolution when Mubarak tried to close the mobile phone networks, Assange and others at WikiLeaks "hacked into Nortel

Nortel Networks Corporation (Nortel), formerly Northern Telecom Limited, was a Canadian Multinational corporation, multinational telecommunications and data networking equipment manufacturer headquartered in Ottawa, Ontario. It was founded in ...

and fought against Mubarak's official hackers to reverse the process".

Legal issues

Swedish sexual assault allegations

Beginning in 2010, Assange contested legal proceedings in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

concerning the requested extradition of Julian Assange to Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. It borders Norway to the west and north, and Finland to the east. At , Sweden is the largest Nordic count ...

for a "preliminary investigation" into accusations of sexual offences made in August 2010. Assange left Sweden for UK on 27 September 2010; an international arrest warrant was issued the same day.bail

Bail is a set of pre-trial restrictions that are imposed on a suspect to ensure that they will not hamper the judicial process. Court bail may be offered to secure the conditional release of a defendant with the promise to appear in court when ...

and sought refuge at Ecuador's Embassy in London and was granted asylum. On 12 August 2015, Swedish prosecutors announced that the

On 12 August 2015, Swedish prosecutors announced that the statute of limitations

A statute of limitations, known in civil law systems as a prescriptive period, is a law passed by a legislative body to set the maximum time after an event within which legal proceedings may be initiated. ("Time for commencing proceedings") In ...

had expired for three of the allegations against Assange while he was in the Ecuadorian embassy. The investigation into the rape allegation was also dropped by Swedish authorities on 19 May 2017 because of Assange's asylum in the Ecuadorian embassy.

US criminal investigations

After WikiLeaks released the Manning material, United States authorities began investigating WikiLeaks and Assange to prosecute them under the Espionage Act of 1917.grand jury

A grand jury is a jury empowered by law to conduct legal proceedings, investigate potential criminal conduct, and determine whether criminal charges should be brought. A grand jury may subpoena physical evidence or a person to testify. A grand ju ...

in Alexandria, Virginia

Alexandria is an independent city (United States), independent city in Northern Virginia, United States. It lies on the western bank of the Potomac River approximately south of Washington, D.C., D.C. The city's population of 159,467 at the 2020 ...

and the administration urged allies to open criminal investigations of Assange. In 2010, the FBI told a lawyer for Assange that he wasn't the subject of an investigation. That year the NSA added Assange to its Manhunting Timeline, an annual account of efforts to capture or kill alleged terrorists and others.

In 2010, the FBI told a lawyer for Assange that he wasn't the subject of an investigation. That year the NSA added Assange to its Manhunting Timeline, an annual account of efforts to capture or kill alleged terrorists and others.FBI

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic Intelligence agency, intelligence and Security agency, security service of the United States and Federal law enforcement in the United States, its principal federal law enforcement ag ...

and became the first informant to work for the FBI from inside WikiLeaks. He gave the FBI several hard drives he had copied from Assange and core WikiLeaks members.The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'' said that court and other documents suggested that Assange was being examined by a grand jury and "several government agencies", including by the FBI

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic Intelligence agency, intelligence and Security agency, security service of the United States and Federal law enforcement in the United States, its principal federal law enforcement ag ...

.Obama Administration

Barack Obama's tenure as the 44th president of the United States began with his first inauguration on January 20, 2009, and ended on January 20, 2017. Obama, a Democrat from Illinois, took office following his victory over Republican nomine ...

, the Department of Justice did not indict Assange because it could not find evidence that his actions differed from those of a journalist.first Trump Administration

Donald Trump's first tenure as the president of the United States began on January 20, 2017, when Trump First inauguration of Donald Trump, was inaugurated as the List of presidents of the United States, 45th president, and ended on January ...

, CIA director Mike Pompeo

Michael Richard Pompeo (; born December 30, 1963) is an American retired politician who served in the First presidency of Donald Trump#Administration, first administration of Donald Trump as director of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) fr ...

and Attorney General Jeff Sessions stepped up pursuit of Assange. Law enforcement officials wanted to learn about Assange's knowledge of WikiLeaks's interactions with Russian intelligence and other actions. They had considered offering Assange some form of immunity from prosecution in exchange for his testimony and had reached out to Assange's lawyers. The negotiations were ended by the Vault 7 disclosures.

In April 2017 US officials were preparing to file formal charges against Assange. Assange's indictment was unsealed in 2019 and expanded on later that year and in 2020.statute of limitations

A statute of limitations, known in civil law systems as a prescriptive period, is a law passed by a legislative body to set the maximum time after an event within which legal proceedings may be initiated. ("Time for commencing proceedings") In ...

on Assange's largest leaks.

In early 2019 the Mueller report wrote the Special Counsel's office considered charging WikiLeaks or Assange "as conspirators in the computer-intrusion conspiracy" and that there were "factual uncertainties" about the role that Assange may have played in the hacks or their distribution that were "the subject of ongoing investigations" by the US Attorney's Office.

Legal issues in Australia

On 2 September 2011 Australia's attorney general, Robert McClelland released a statement that the US diplomatic cables published by Wikileaks had identified at least one ASIO officer, which was a crime in Australia. According to The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in Manchester in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'' and changed its name in 1959, followed by a move to London. Along with its sister paper, ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardi ...

and Al Jazeera, this meant Assange could face prosecution in Australia.

In 2014 WikiLeaks published information about political bribery allegations in Australia, violating a suppression order and meaning Assange could be charged if he returned to Australia.

Ecuadorian embassy period

Entering the embassy

On 19 June 2012, the Ecuadorian

On 19 June 2012, the Ecuadorian foreign minister

In many countries, the ministry of foreign affairs (abbreviated as MFA or MOFA) is the highest government department exclusively or primarily responsible for the state's foreign policy and relations, diplomacy, bilateral, and multilateral r ...

, Ricardo Patiño

Ricardo Armando Patiño Aroca (born 16 May 1954) is an Ecuadorian politician who has served as Minister of Foreign Affairs of Ecuador from 2010 until 2016, under the government of President Rafael Correa. Previously he was Minister of Financ ...

, announced that Assange had applied for political asylum

The right of asylum, sometimes called right of political asylum (''asylum'' ), is a juridical concept, under which people persecuted by their own rulers might be protected by another sovereignty, sovereign authority, such as a second country or ...

, that the Ecuadorian government was considering his request, and that Assange was at the Ecuadorian embassy in London. An office was converted into a studio apartment and equipped with a bed, telephone, sun lamp, computer, shower, treadmill, and kitchenette. The embassy removed the toilet in the women's bathroom at Assange's request so he could sleep. He was limited to roughly and ate a combination of takeaways and food prepared by the staff.satrap

A satrap () was a governor of the provinces of the ancient Median kingdom, Median and Achaemenid Empire, Persian (Achaemenid) Empires and in several of their successors, such as in the Sasanian Empire and the Hellenistic period, Hellenistic empi ...

y", he said.Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations

The Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations of 1961 is an international treaty that defines a framework for diplomatic relations between independent countries. Its aim is to facilitate "the development of friendly relations" among government ...

. Officers of the Metropolitan Police Service were stationed outside the embassy from June 2012 to October 2015 to arrest Assange if he left the embassy and compel him to attend the extradition appeal hearing. The police officers were withdrawn on grounds of cost in October 2015, but the police said they would still deploy "several overt and covert tactics to arrest him". The Metropolitan Police Service said the cost of the policing for the period was £12.6million.

The Australian attorney-general, Nicola Roxon, wrote to Jennifer Robinson, a lawyer acting for Assange, saying that the Australian government would not seek to involve itself in any diplomacy about Assange. Prime Minister Julia Gillard said her government had no evidence the US intended to charge and extradite Assange at that time, and Roxon suggested that if Assange was imprisoned in the US, he could apply for an international prisoner transfer to Australia. Assange's lawyers described the letter as a "declaration of abandonment". WikiLeaks insiders stated that Assange decided to seek asylum because he felt abandoned by the Australian government.Rafael Correa

Rafael Vicente Correa Delgado (; born 6 April 1963) is an Ecuadorian politician and economist who served as the 45th president of Ecuador from 2007 to 2017. The leader of the PAIS Alliance political movement from its foundation until 2017, Corr ...

confirmed on 18 August that Assange could stay at the embassy indefinitely. Documents released that month showed that Australia had no objection to a potential extradition to the US, and a spokesman for Foreign Minister Bob Carr said that Assange refused an offer for consular assistance. In December, Assange said he felt freer in the embassy despite being more confined because he was the author of his own confinement.

Helping Edward Snowden

In 2013, Assange and others in WikiLeaks helped whistleblower

Whistleblowing (also whistle-blowing or whistle blowing) is the activity of a person, often an employee, revealing information about activity within a private or public organization that is deemed illegal, immoral, illicit, unsafe, unethical or ...

Edward Snowden

Edward Joseph Snowden (born June 21, 1983) is a former National Security Agency (NSA) intelligence contractor and whistleblower who leaked classified documents revealing the existence of global surveillance programs.

Born in 1983 in Elizabeth ...

flee from US law enforcement. After the United States cancelled Snowden's passport, stranding him in Russia, they considered transporting him to South America on the presidential jet of a sympathetic South American leader. In order to throw the US off the scent, they spoke about the jet of the Bolivian president Evo Morales, instead of the jet they were considering.Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

, France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

, and Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

to deny the jet access to their airspace over false rumours Snowden was on board. Assange said the grounding "reveals the true nature of the relationship between Western Europe and the United States" as "a phone call from U.S. intelligence was enough to close the airspace to a booked presidential flight, which has immunity". Assange advised Snowden that he would be safest in Russia which was better able to protect its borders than Venezuela, Brazil, or Ecuador.

Australian Senate bid and WikiLeaks Party

Assange stood for the Australian Senate

The Senate is the upper house of the Bicameralism, bicameral Parliament of Australia, the lower house being the Australian House of Representatives, House of Representatives.

The powers, role and composition of the Senate are set out in Chap ...

in Victoria in the 2013 Australian federal election

The 2013 Australian federal election to elect the members of the 44th Parliament of Australia took place on Saturday, 7 September 2013. The centre-right Coalition (Australia), Liberal/National Coalition Opposition (Australia), opposition led by ...

, and launched the WikiLeaks Party, but failed to win a seat.

Campaigning for Kim Dotcom

Documents provided by Edward Snowden showed that in 2012 and 2013 the New Zealand

New Zealand () is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and List of islands of New Zealand, over 600 smaller islands. It is the List of isla ...

government worked to establish a secret mass surveillance programme which it called "Operation Speargun". On 15 September 2014 while campaigning for Internet entrepreneur Kim Dotcom, Assange appeared via remote video link on his town hall meeting held in Auckland

Auckland ( ; ) is a large metropolitan city in the North Island of New Zealand. It has an urban population of about It is located in the greater Auckland Region, the area governed by Auckland Council, which includes outlying rural areas and ...

, which discussed the programme. Assange said the Snowden documents showed that he had been a target of the programme and that "Operation Speargun" represented "an extreme, bizarre, Orwellian future that is being constructed secretly in New Zealand".

Other developments

In 2014 the company hired to monitor Assange warned Ecuador's government that he was "intercepting and gathering information from the embassy and the people who worked there" and that he had compromised the embassy's communications system, which WikiLeaks called "an anonymous libel aligned with the current UK-US government onslaught against Mr Assange". According to ''El País

(; ) is a Spanish-language daily newspaper in Spain. is based in the capital city of Madrid and it is owned by the Spanish media conglomerate PRISA.

It is the second-most circulated daily newspaper in Spain . is the most read newspaper in ...

'', a November 2014 UC Global report said that a briefcase with a listening device was found in a room occupied by Assange. The UC Global report said that proved "the suspicion that he is listening in on diplomatic personnel, in this case against the ambassador and the people around him, in an effort to obtain privileged information that could be used to maintain his status in the embassy." Ambassador Falconí said Assange was evasive when asked about the briefcase.Le Monde

(; ) is a mass media in France, French daily afternoon list of newspapers in France, newspaper. It is the main publication of Le Monde Group and reported an average print circulation, circulation of 480,000 copies per issue in 2022, including ...

'' published an open letter from Assange to French President François Hollande

François Gérard Georges Nicolas Hollande (; born 12 August 1954) is a French politician who served as President of France from 2012 to 2017. Before his presidency, he was First Secretary of the Socialist Party (France), First Secretary of th ...

in which Assange urged the French government to grant him refugee status.

2016 US presidential election

In February 2016 Assange wrote: " Hillary lacks judgment and will push the United States into endless, stupid wars which spread terrorism... she certainly should not become president of the United States." Before the election, WikiLeaks was approached by Cambridge Analytica CEO Alexander Nix about releasing missing Clinton emails. Assange rejected the request and the '' Daily Beast'' reported that he replied he preferred to do the work on his own. In an Election Day statement, Assange said that "The Democratic and Republican candidates have both expressed hostility towards whistleblowers".

On 22 July 2016, WikiLeaks released emails and documents from the Democratic National Committee

The Democratic National Committee (DNC) is the principal executive leadership board of the United States's Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party. According to the party charter, it has "general responsibility for the affairs of the ...

(DNC), in which the DNC presented ways of undercutting Clinton's competitor Bernie Sanders

Bernard Sanders (born September8, 1941) is an American politician and activist who is the Seniority in the United States Senate, senior United States Senate, United States senator from the state of Vermont. He is the longest-serving independ ...

and showed favouritism towards Clinton. The release led to the resignation of DNC chairwoman Debbie Wasserman Schultz

Deborah Wasserman Schultz ( Wasserman; ; born September 27, 1966) is an American politician serving as the United States House of Representatives, U.S. representative for , first elected to Congress in United States House of Representatives elec ...

and an apology to Sanders from the DNC. ''The New York Times'' wrote that Assange had timed the release to coincide with the 2016 Democratic National Convention

The 2016 Democratic National Convention was a presidential nominating convention, held at the Wells Fargo Center in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, from July 25 to 28, 2016. The convention gathered delegates of the Democratic Party, the maj ...

because he believed Clinton had pushed for his indictment and he regarded her as a "liberal war hawk".Jill Stein

Jill Ellen Stein (born May 14, 1950) is an American physician, activist, and perennial candidate who was the Green Party of the United States, Green Party's nominee for President of the United States in the Jill Stein 2012 presidential campaign ...

, or Gary Johnson's campaign.

Later years in the embassy

In March 2017, WikiLeaks began releasing the largest leak of CIA documents in history, codenamed Vault 7. The documents included details of the CIA's hacking capabilities and software tools used to break into smartphones, computers and other Internet-connected devices.

In March 2017, WikiLeaks began releasing the largest leak of CIA documents in history, codenamed Vault 7. The documents included details of the CIA's hacking capabilities and software tools used to break into smartphones, computers and other Internet-connected devices.Mike Pompeo

Michael Richard Pompeo (; born December 30, 1963) is an American retired politician who served in the First presidency of Donald Trump#Administration, first administration of Donald Trump as director of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) fr ...

called WikiLeaks "a non-state hostile intelligence service

An intelligence agency is a government agency responsible for the collection, analysis, and exploitation of information in support of law enforcement, national security, military, public safety, and foreign policy objectives.

Means of info ...

often abetted by state actors like Russia". Assange responded "The head of the CIA determining who is a publisher, who's not a publisher, who's a journalist, who's not a journalist, is totally out of line". According to former intelligence officials, in the wake of the Vault7 leaks, the CIA talked about kidnapping

Kidnapping or abduction is the unlawful abduction and confinement of a person against their will, and is a crime in many jurisdictions. Kidnapping may be accomplished by use of force or fear, or a victim may be enticed into confinement by frau ...

Assange from Ecuador's London embassy, and some senior officials discussed his potential assassination. Yahoo! News found "no indication that the most extreme measures targeting Assange were ever approved." Some of its sources said that they had alerted House

A house is a single-unit residential building. It may range in complexity from a rudimentary hut to a complex structure of wood, masonry, concrete or other material, outfitted with plumbing, electrical, and heating, ventilation, and air c ...

and Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

intelligence committees to the plans that Pompeo and others was suggesting.High Court of Justice

The High Court of Justice in London, known properly as His Majesty's High Court of Justice in England, together with the Court of Appeal (England and Wales), Court of Appeal and the Crown Court, are the Courts of England and Wales, Senior Cour ...

in London as it considered the U.S. appeal of a lower court's ruling that Assange could not be extradited to face charges in the U.S. In 2022 the Spanish courts summoned Pompeo as a witness to testify on the alleged plans.

On 6 June 2017 Assange supported NSA leaker Reality Winner, who had been arrested three days earlier, by tweeting "Acts of non-elite sources communicating knowledge should be strongly encouraged". On 16 August 2017, US Republican congressman Dana Rohrabacher

Dana Tyrone Rohrabacher ( ; born June 21, 1947) is an American former politician who served in the United States House of Representatives, U.S. House of Representatives from 1989 to 2019. Representing for the last three terms of his House tenure ...

visited Assange and told him that Trump would pardon him on condition that he would agree to say that Russia was not involved in the 2016 Democratic National Committee email leak

The 2016 Democratic National Committee email leak is a collection of Democratic National Committee (DNC) emails Democratic National Committee cyber attacks, stolen by one or more hackers operating under the pseudonym "Guccifer 2.0" who are allege ...

s.Fairfax Media

Fairfax Media was a media (communication), media company in Australia and New Zealand, with investments in newspaper, magazines, radio and digital properties. The company was founded by John Fairfax as John Fairfax and Sons, who purchased ''The ...

, he was responsible for more than 25% of all Twitter traffic under the hashtag #Catalonia before the 2017 Catalan independence referendum

An independence referendum was held on 1 October 2017 in the Spanish autonomous community of Catalonia, passed by the Parliament of Catalonia as the Law on the Referendum on Self-determination of Catalonia and called by the Generalitat de Catalun ...

.Catalonia

Catalonia is an autonomous community of Spain, designated as a ''nationalities and regions of Spain, nationality'' by its Statute of Autonomy of Catalonia of 2006, Statute of Autonomy. Most of its territory (except the Val d'Aran) is situate ...

confused people with each other or fictional characters, and others made distorted or exaggerated claims.Spanish government

The government of Spain () is the central government which leads the executive branch and the General State Administration of the Kingdom of Spain.

The Government consists of the Prime Minister and the Ministers; the prime minister has the o ...

.self-determination

Self-determination refers to a people's right to form its own political entity, and internal self-determination is the right to representative government with full suffrage.

Self-determination is a cardinal principle in modern international la ...

. In the lead up to the referendum, he provided Catalans instructions on how to communicate and organise through secure channels and historical background on the Catalan independence movement. When the Spanish Government disabled voting apps, Assange tweeted instructions on how Catalans could use other apps to find out information about voting. Assange's actions upset the Spanish government, leading to concerns in Ecuador, which soon after cut off Assange's internet and stopped his access to visitors. In January 2020, the Catalan Dignity Commission awarded Assange its 2019 Dignity Prize to " ecognisehis efforts to correct misreporting of events and to provide live video updates to the world of the peaceful Catalan protesters and the brutal crackdown on them by Spanish police".diplomat

A diplomat (from ; romanization, romanized ''diploma'') is a person appointed by a state (polity), state, International organization, intergovernmental, or Non-governmental organization, nongovernmental institution to conduct diplomacy with one ...

, and that he did not have "any type of privileges and immunities under the Vienna Convention." The citizenship was revoked in July 2021Mark Warner

Mark Robert Warner (born December 15, 1954) is an American businessman and politician serving as the senior United States senator from Virginia, a seat he has held since 2009. A member of the Democratic Party, Warner served as the 69th gove ...

, a senior Democrat senator investigating Trump-Russia links. Assange asked the fake Hannity to contact him about it on "other channels". In February 2018, after Sweden had suspended its investigation, Assange brought two legal actions, arguing that Britain should drop its arrest warrant for him as it was "no longer right or proportionate to pursue him" and the arrest warrant for breaching bail had lost its "purpose and its function". In both cases, Senior District Judge Emma Arbuthnot ruled that the arrest warrant should remain in place.The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in Manchester in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'' and changed its name in 1959, followed by a move to London. Along with its sister paper, ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardi ...

'' reported that Ecuador devised plans to help Assange escape should British police forcibly enter the embassy to seize him.USAID

The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) is an agency of the United States government that has been responsible for administering civilian United States foreign aid, foreign aid and development assistance.

Established in 19 ...

mission to Ecuador depended on Assange being handed over to the authorities.

On 19 October 2018 Assange sued the government of Ecuador for violating his "fundamental rights and freedoms" by threatening to remove his protection and cut off his access to the outside world, refusing him visits from journalists and human rights organisations and installing signal jammers to prevent phone calls and internet access.Inter-American Commission on Human Rights

The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (the IACHR or, in the three other official languages Spanish, French, and Portuguese language, Portuguese CIDH, ''Comisión Interamericana de los Derechos Humanos'', ''Commission Interaméricaine des ...

rejected a complaint submitted by Assange asking the Ecuadorian government to "ease the conditions that it had imposed on his residence" at the embassy and to protect him from extradition to the US. It also requested US prosecutors unseal criminal charges that had been filed against him. The commission rejected his complaint.

Surveillance of Assange in the embassy

After Julian Assange was granted asylum and entered the Ecuadorian embassy in London, new CCTV

Closed-circuit television (CCTV), also known as video surveillance, is the use of closed-circuit television cameras to transmit a signal to a specific place on a limited set of monitors. It differs from broadcast television in that the signa ...

cameras were installed. The Ecuadorian security service hired UC Global to provide security for the embassy. Without the knowledge of the Ecuadorian security service, employees of UC Global made detailed recordings of Assange's daily activities, interactions with embassy staff, and visits from his legal team and others.Ricardo Patiño

Ricardo Armando Patiño Aroca (born 16 May 1954) is an Ecuadorian politician who has served as Minister of Foreign Affairs of Ecuador from 2010 until 2016, under the government of President Rafael Correa. Previously he was Minister of Financ ...

had to explain the situation to the ambassador.Sheldon Adelson

Sheldon Gary Adelson (August 4, 1933 – January 11, 2021) was an American businessman, investor, and political donor. He was the founder, chairman and chief executive officer of Las Vegas Sands Corporation, which founded the Marina Bay Sa ...

, the owner of the Las Vegas Sands

Las Vegas Sands Corp. is an American casino and resort company with corporate headquarters in Las Vegas, Nevada, United States. It was founded by Sheldon Adelson, Sheldon G. Adelson and his partners out of the Sands Hotel and Casino on the Las ...

. According to court papers seen by the Associated Press, it was alleged that Morales had passed the recordings to Zohar Lahav, described by Assange's lawyers as a security officer at Las Vegas Sands. In 2022, four associates of Assange filed a lawsuit against the CIA alleging their civil rights were violated when they were recorded as part of the surveillance of Assange. In a December 2023 ruling allowing the lawsuit to proceed and rejecting a CIA motion to dismiss, the judge trimmed the scope of the suit by rejecting some portions.

Indictment and arrest

On 11 April 2019, Ecuador revoked Assange’s asylum, he was arrested for failing to appear in court, and he was carried out of the embassy by members of the London Metropolitan Police. Following his arrest, the US revealed a previously sealed 2018 US indictment in which Assange was charged with conspiracy

A conspiracy, also known as a plot, ploy, or scheme, is a secret plan or agreement between people (called conspirers or conspirators) for an unlawful or harmful purpose, such as murder, treason, or corruption, especially with a political motivat ...

to commit computer intrusion related to his involvement with Chelsea Manning and WikiLeaks