Judith Lloyd on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Book of Judith is a

The Book of Judith is a

/ref> Speculated reasons for its exclusion include the possible lateness of its composition, possible Greek origin, apparent support of the

::C'. Judith and her maid return to Bethulia (13.10b–11)

:B'. Judith plans the destruction of Israel's enemy (13:12–16:20)

A'. Conclusion about Judith (16.1–25)

Similarly, parallels within Part II are noted in comments within the New American Bible Revised Edition: Judith summons a town meeting in Judith 8:10 in advance of her expedition and is acclaimed by such a meeting in Judith 13:12–13; Uzziah blesses Judith in advance in Judith 8:5 and afterwards in Judith 13:18–20.

::C'. Judith and her maid return to Bethulia (13.10b–11)

:B'. Judith plans the destruction of Israel's enemy (13:12–16:20)

A'. Conclusion about Judith (16.1–25)

Similarly, parallels within Part II are noted in comments within the New American Bible Revised Edition: Judith summons a town meeting in Judith 8:10 in advance of her expedition and is acclaimed by such a meeting in Judith 13:12–13; Uzziah blesses Judith in advance in Judith 8:5 and afterwards in Judith 13:18–20.

Judith 12: Notes & Commentary

accessed 31 October 2022 He brought in Judith to recline with Holofernes and was the first one who discovered his beheading. Uzziah or Oziah, governor of Bethulia; together with Cabri and Carmi, he rules over Judith's city. When the city is besieged by the Assyrians and the water supply dries up, he agrees to the people's call to surrender if God has not rescued them within five days, a decision challenged as "rash" by Judith.

The Oxford Bible Commentary

, p. 638 "loudly proclaimed" in advance of her actions in the following chapters. This runs to 14 verses in English versions, 19 verses in the Vulgate.

Today, it is generally accepted that the Book of Judith's

Today, it is generally accepted that the Book of Judith's

Arnold Bennett: "Judith"

Gutenberg Ed. In 1981, the play "Judith among the Lepers" by the Israeli (Hebrew) playwright

The Book of Judith

Full text (also available i

* Craven, Ton

Judith: Apocrypha

''The Shalvi/Hyman Encyclopedia of Jewish Women'' 31 December 1999 at

JUDITH, BOOK OF

at ''The Jewish Encyclopedia'', 1906 * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Judith, Book of Book of Judith Ancient Hebrew texts Ashurbanipal Biblical women in ancient warfare Deuterocanonical books Historical books Historical novels Jewish apocrypha

deuterocanonical

The deuterocanonical books, meaning 'of, pertaining to, or constituting a second Biblical canon, canon', collectively known as the Deuterocanon (DC), are certain books and passages considered to be Biblical canon, canonical books of the Old ...

book included in the Septuagint

The Septuagint ( ), sometimes referred to as the Greek Old Testament or The Translation of the Seventy (), and abbreviated as LXX, is the earliest extant Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible from the original Biblical Hebrew. The full Greek ...

and the Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

and Eastern Orthodox

Eastern Orthodoxy, otherwise known as Eastern Orthodox Christianity or Byzantine Christianity, is one of the three main Branches of Christianity, branches of Chalcedonian Christianity, alongside Catholic Church, Catholicism and Protestantism ...

Christian

A Christian () is a person who follows or adheres to Christianity, a Monotheism, monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus Christ. Christians form the largest religious community in the wo ...

Old Testament

The Old Testament (OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible, or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew and occasionally Aramaic writings by the Isr ...

of the Bible

The Bible is a collection of religious texts that are central to Christianity and Judaism, and esteemed in other Abrahamic religions such as Islam. The Bible is an anthology (a compilation of texts of a variety of forms) originally writt ...

but excluded from the Hebrew canon and assigned by Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

s to the apocrypha

Apocrypha () are biblical or related writings not forming part of the accepted canon of scripture, some of which might be of doubtful authorship or authenticity. In Christianity, the word ''apocryphal'' (ἀπόκρυφος) was first applied to ...

. It tells of a Jewish

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

widow, Judith, who uses her beauty and charm to kill an Assyria

Assyria (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , ''māt Aššur'') was a major ancient Mesopotamian civilization that existed as a city-state from the 21st century BC to the 14th century BC and eventually expanded into an empire from the 14th century BC t ...

n general who has besieged her city, Bethulia

Bethulia (, ''Baituloua''; Hebrew: wikt:בתוליה, בתוליה) is a biblical "city whose deliverance by Judith, when besieged by Holofernes, forms the subject of the ''Book of Judith''."

Etymology

The name "Bethulia" in Hebrew can be assoc ...

. With this act, she saves nearby Jerusalem

Jerusalem is a city in the Southern Levant, on a plateau in the Judaean Mountains between the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and the Dead Sea. It is one of the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest cities in the world, and ...

from total destruction. The name Judith (), meaning "praised" or "Jewess", is the feminine form of Judah.

The surviving manuscripts of Greek translations appear to contain several historical anachronism

An anachronism (from the Greek , 'against' and , 'time') is a chronological inconsistency in some arrangement, especially a juxtaposition of people, events, objects, language terms and customs from different time periods. The most common type ...

s, which is why some Protestant scholars now consider the book ahistorical. Instead, the book is classified as a parable

A parable is a succinct, didactic story, in prose or verse, that illustrates one or more instructive lessons or principles. It differs from a fable in that fables employ animals, plants, inanimate objects, or forces of nature as characters, whe ...

, theological novel, or even the first historical novel

Historical fiction is a literary genre in which a fictional plot takes place in the setting of particular real historical events. Although the term is commonly used as a synonym for historical fiction literature, it can also be applied to oth ...

. The Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

formerly maintained the book's historicity

Historicity is the historical actuality of persons and events, meaning the quality of being part of history instead of being a historical myth, legend, or fiction. The historicity of a claim about the past is its factual status. Historicity deno ...

, assigning its events to the reign of King Manasseh of Judah and that the names were changed in later centuries for an unknown reason. The ''Jewish Encyclopedia

''The Jewish Encyclopedia: A Descriptive Record of the History, Religion, Literature, and Customs of the Jewish People from the Earliest Times to the Present Day'' is an English-language encyclopedia containing over 15,000 articles on the ...

'' identifies Shechem

Shechem ( ; , ; ), also spelled Sichem ( ; ) and other variants, was an ancient city in the southern Levant. Mentioned as a Canaanite city in the Amarna Letters, it later appears in the Hebrew Bible as the first capital of the Kingdom of Israe ...

(modern day Nablus

Nablus ( ; , ) is a State of Palestine, Palestinian city in the West Bank, located approximately north of Jerusalem, with a population of 156,906. Located between Mount Ebal and Mount Gerizim, it is the capital of the Nablus Governorate and a ...

) as "Bethulia", and argues that the name was changed because of the feud between the Jews and Samaritans

Samaritans (; ; ; ), are an ethnoreligious group originating from the Hebrews and Israelites of the ancient Near East. They are indigenous to Samaria, a historical region of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah that ...

. If this is the case, it would explain why other names seem anachronistic as well.

Historical context

Original language

It is not clear whether the Book of Judith was originally written in Hebrew, Aramaic or Greek, as the oldest existing version is from theSeptuagint

The Septuagint ( ), sometimes referred to as the Greek Old Testament or The Translation of the Seventy (), and abbreviated as LXX, is the earliest extant Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible from the original Biblical Hebrew. The full Greek ...

, a Greek translation of the Hebrew scriptures. However, due to the large number of Hebraisms in the text, it is generally agreed that the book was written in a Semitic language

The Semitic languages are a branch of the Afroasiatic language family. They include Arabic,

Amharic, Tigrinya, Aramaic, Hebrew, Maltese, Modern South Arabian languages and numerous other ancient and modern languages. They are spoken by mo ...

, probably Hebrew

Hebrew (; ''ʿÎbrit'') is a Northwest Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic language within the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family. A regional dialect of the Canaanite languages, it was natively spoken by the Israelites and ...

or Aramaic

Aramaic (; ) is a Northwest Semitic language that originated in the ancient region of Syria and quickly spread to Mesopotamia, the southern Levant, Sinai, southeastern Anatolia, and Eastern Arabia, where it has been continually written a ...

, rather than Koine Greek

Koine Greek (, ), also variously known as Hellenistic Greek, common Attic, the Alexandrian dialect, Biblical Greek, Septuagint Greek or New Testament Greek, was the koiné language, common supra-regional form of Greek language, Greek spoken and ...

. When Jerome completed his Latin Vulgate

The Vulgate () is a late-4th-century Bible translations into Latin, Latin translation of the Bible. It is largely the work of Saint Jerome who, in 382, had been commissioned by Pope Damasus I to revise the Gospels used by the Diocese of ...

translation, he asserted his belief that the book was written "in Chaldean (Aramaic) words". Jerome's Latin translation was based on an Aramaic manuscript and was shorter because he omitted passages that he could not read or understand in the Aramaic that otherwise existed in the Septuagint. The Aramaic manuscript used by Jerome has long since been lost.

Carey A. Moore argued that the Greek text of Judith was a translation from a Hebrew original, and used many examples of conjectured translation errors, Hebraic idioms, and Hebraic syntax. The extant Hebrew manuscripts are very late and only date back to the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

. The two surviving Hebrew manuscripts of Judith are translated from the Greek Septuagint and the Latin Vulgate.

The Hebrew versions name important figures directly, such as the Seleucid

The Seleucid Empire ( ) was a Greek state in West Asia during the Hellenistic period. It was founded in 312 BC by the Macedonian general Seleucus I Nicator, following the division of the Macedonian Empire founded by Alexander the Great, a ...

king Antiochus IV Epiphanes

Antiochus IV Epiphanes ( 215 BC–November/December 164 BC) was king of the Seleucid Empire from 175 BC until his death in 164 BC. Notable events during Antiochus' reign include his near-conquest of Ptolemaic Egypt, his persecution of the Jews of ...

, and place the events during the Hellenistic period

In classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Greek history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the death of Cleopatra VII in 30 BC, which was followed by the ascendancy of the R ...

when the Maccabees

The Maccabees (), also spelled Machabees (, or , ; or ; , ), were a group of Jews, Jewish rebel warriors who took control of Judea, which at the time was part of the Seleucid Empire. Its leaders, the Hasmoneans, founded the Hasmonean dynasty ...

battled the Seleucid monarchs. However, because the Hebrew manuscripts mention kingdoms that had not existed for hundreds of years by the time of the Seleucids, it is unlikely that these were the original names in the text. Jeremy Corley argued that Judith was originally composed in Greek that was carefully modeled after Hebrew and pointed out "Septuagintalisms" in the vocabulary and phrasing of the Greek text.

Canonicity

In Judaism

While the author was likely Jewish, there is no evidence aside from its inclusion in theSeptuagint

The Septuagint ( ), sometimes referred to as the Greek Old Testament or The Translation of the Seventy (), and abbreviated as LXX, is the earliest extant Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible from the original Biblical Hebrew. The full Greek ...

that the Book of Judith was ever considered authoritative or a candidate for canonicity by any Jewish group. The Masoretic Text

The Masoretic Text (MT or 𝕸; ) is the authoritative Hebrew and Aramaic text of the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible (''Tanakh'') in Rabbinic Judaism. The Masoretic Text defines the Jewish canon and its precise letter-text, with its vocaliz ...

of the Hebrew Bible

The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh (;"Tanach"

. '' Dead Sea Scrolls The Dead Sea Scrolls, also called the Qumran Caves Scrolls, are a set of List of Hebrew Bible manuscripts, ancient Jewish manuscripts from the Second Temple period (516 BCE – 70 CE). They were discovered over a period of ten years, between ...

or any early Rabbinic literature.Flint, Peter & VanderKam, James, ''The Meaning of the Dead Sea Scrolls: Their Significance For Understanding the Bible, Judaism, Jesus, and Christianity'', Continuum International, 2010, p. 160 (Protestant Canon) and p. 209 (Judith not among Dead Sea Scrolls). '' Dead Sea Scrolls The Dead Sea Scrolls, also called the Qumran Caves Scrolls, are a set of List of Hebrew Bible manuscripts, ancient Jewish manuscripts from the Second Temple period (516 BCE – 70 CE). They were discovered over a period of ten years, between ...

/ref> Speculated reasons for its exclusion include the possible lateness of its composition, possible Greek origin, apparent support of the

Hasmonean dynasty

The Hasmonean dynasty (; ''Ḥašmōnāʾīm''; ) was a ruling dynasty of Judea and surrounding regions during the Hellenistic times of the Second Temple period (part of classical antiquity), from BC to 37 BC. Between and BC the dynasty rule ...

(to which the early rabbinate was opposed), and perhaps the brash and seductive character of Judith herself.

After disappearing from circulation among Jews for over a millennium, however, references to the Book of Judith and the figure of Judith herself resurfaced in the religious literature of crypto-Jews

Crypto-Judaism is the secret adherence to Judaism while publicly professing to be of another faith; practitioners are referred to as "crypto-Jews" (origin from Greek ''kryptos'' – , 'hidden').

The term is especially applied historically to Spani ...

who escaped Christian persecution after the capitulation of the Caliphate of Córdoba

A caliphate ( ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with Khalifa, the title of caliph (; , ), a person considered a political–religious successor to the Islamic prophet Muhammad and a leader of ...

. The renewed interest took the form of "tales of the heroine, liturgical poems, commentaries on the Talmud, and passages in Jewish legal codes." Although the text does not mention Hanukkah

Hanukkah (, ; ''Ḥănukkā'' ) is a Jewish holidays, Jewish festival commemorating the recovery of Jerusalem and subsequent rededication of the Second Temple at the beginning of the Maccabean Revolt against the Seleucid Empire in the 2nd ce ...

, it became customary for a Hebrew midrash

''Midrash'' (;"midrash"

. ''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. ; or ''midrashot' ...

ic variant of the Judith story to be read on the . ''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. ; or ''midrashot' ...

Shabbat

Shabbat (, , or ; , , ) or the Sabbath (), also called Shabbos (, ) by Ashkenazi Hebrew, Ashkenazim, is Judaism's day of rest on the seventh day of the seven-day week, week—i.e., Friday prayer, Friday–Saturday. On this day, religious Jews ...

of Hanukkah as the story of Hanukkah takes place during the time of the Hasmonean dynasty.

That midrash, whose heroine is portrayed as gorging the antagonist on cheese and wine before cutting off his head, may have formed the basis of the minor Jewish tradition to eat dairy products during Hanukkah. In that respect, the Jewry of Europe during the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

appear to have viewed Judith as the Maccabean- Hasmonean counterpart to Queen Esther, the heroine of the holiday of Purim

Purim (; , ) is a Jewish holidays, Jewish holiday that commemorates the saving of the Jews, Jewish people from Genocide, annihilation at the hands of an official of the Achaemenid Empire named Haman, as it is recounted in the Book of Esther (u ...

. The textual reliability of the Book of Judith was also taken for granted, to the extent that biblical commentator Nachmanides (Ramban) quoted several passages from a Peshitta

The Peshitta ( ''or'' ') is the standard Syriac edition of the Bible for Syriac Christian churches and traditions that follow the liturgies of the Syriac Rites.

The Peshitta is originally and traditionally written in the Classical Syriac d ...

(Syriac version) of Judith in support of his rendering of Deuteronomy

Deuteronomy (; ) is the fifth book of the Torah (in Judaism), where it is called () which makes it the fifth book of the Hebrew Bible and Christian Old Testament.

Chapters 1–30 of the book consist of three sermons or speeches delivered to ...

21:14.

In Christianity

Althoughearly Christians

Early Christianity, otherwise called the Early Church or Paleo-Christianity, describes the historical era of the Christian religion up to the First Council of Nicaea in 325. Christianity spread from the Levant, across the Roman Empire, and bey ...

, such as Clement of Rome

Clement of Rome (; ; died ), also known as Pope Clement I, was the Pope, Bishop of Rome in the Christianity in the 1st century, late first century AD. He is considered to be the first of the Apostolic Fathers of the Church.

Little is known about ...

, Tertullian

Tertullian (; ; 155 – 220 AD) was a prolific Early Christianity, early Christian author from Roman Carthage, Carthage in the Africa (Roman province), Roman province of Africa. He was the first Christian author to produce an extensive co ...

, and Clement of Alexandria

Titus Flavius Clemens, also known as Clement of Alexandria (; – ), was a Christian theology, Christian theologian and philosopher who taught at the Catechetical School of Alexandria. Among his pupils were Origen and Alexander of Jerusalem. A ...

, read and used the Book of Judith, some of the oldest Christian canons, including the Bryennios List

The Old Testament is the first section of the two-part Christian biblical canon; the second section is the New Testament. The Old Testament includes the books of the Hebrew Bible (Tanakh) or protocanon, and in various Christian denominations al ...

(1st/2nd century), that of Melito of Sardis

Melito of Sardis ( ''Melítōn Sárdeōn''; died ) was a Roman Christian prelate who served as Bishop of Sardis, near Smyrna in western Anatolia. He held a foremost place among the early Christian bishops in Roman Asia due to his personal infl ...

(2nd century), and Origen

Origen of Alexandria (), also known as Origen Adamantius, was an Early Christianity, early Christian scholar, Asceticism#Christianity, ascetic, and Christian theology, theologian who was born and spent the first half of his career in Early cent ...

(3rd century), do not include it. Jerome

Jerome (; ; ; – 30 September 420), also known as Jerome of Stridon, was an early Christian presbyter, priest, Confessor of the Faith, confessor, theologian, translator, and historian; he is commonly known as Saint Jerome.

He is best known ...

, when he produced his Latin translation of the Hebrew Bible, the Vulgate

The Vulgate () is a late-4th-century Bible translations into Latin, Latin translation of the Bible. It is largely the work of Saint Jerome who, in 382, had been commissioned by Pope Damasus I to revise the Gospels used by the Diocese of ...

, counted it among the apocrypha, (though he translated it and later seemed to quote it as scripture), as did Athanasius

Athanasius I of Alexandria ( – 2 May 373), also called Athanasius the Great, Athanasius the Confessor, or, among Coptic Christians, Athanasius the Apostolic, was a Christian theologian and the 20th patriarch of Alexandria (as Athanasius ...

, Cyril of Jerusalem

Cyril of Jerusalem (, ''Kýrillos A Ierosolýmon''; ; 386) was a theologian of the Early Church. About the end of AD 350, he succeeded Maximus as Bishop of Jerusalem, but was exiled on more than one occasion due to the enmity of Acacius of ...

, and Epiphanius of Salamis

Epiphanius of Salamis (; – 403) was the bishop of Salamis, Cyprus, at the end of the Christianity in the 4th century, 4th century. He is considered a saint and a Church Father by the Eastern Orthodox Church, Eastern Orthodox, Catholic Churche ...

.

Many influential fathers

A father is the male parent of a child. Besides the paternal bonds of a father to his children, the father may have a parental, legal, and social relationship with the child that carries with it certain rights and obligations. A biological fathe ...

and doctors

Doctor, Doctors, The Doctor or The Doctors may refer to:

Titles and occupations

* Physician, a medical practitioner

* Doctor (title), an academic title for the holder of a doctoral-level degree

** Doctorate

** List of doctoral degrees awarded b ...

of the Church, including Augustine

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; ; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430) was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Africa. His writings deeply influenced the development of Western philosop ...

, Basil of Caesarea

Basil of Caesarea, also called Saint Basil the Great (330 – 1 or 2 January 379) was an early Roman Christian prelate who served as Bishop of Caesarea in Cappadocia from 370 until his death in 379. He was an influential theologian who suppor ...

, Tertullian

Tertullian (; ; 155 – 220 AD) was a prolific Early Christianity, early Christian author from Roman Carthage, Carthage in the Africa (Roman province), Roman province of Africa. He was the first Christian author to produce an extensive co ...

, John Chrysostom

John Chrysostom (; ; – 14 September 407) was an important Church Father who served as archbishop of Constantinople. He is known for his preaching and public speaking, his denunciation of abuse of authority by both ecclesiastical and p ...

, Ambrose

Ambrose of Milan (; 4 April 397), venerated as Saint Ambrose, was a theologian and statesman who served as Bishop of Milan from 374 to 397. He expressed himself prominently as a public figure, fiercely promoting Roman Christianity against Ari ...

, Bede the Venerable and Hilary of Poitiers

Hilary of Poitiers (; ) was Bishop of Poitiers and a Doctor of the Church. He was sometimes referred to as the "Hammer of the Arians" () and the " Athanasius of the West". His name comes from the Latin word for happy or cheerful. In addition t ...

, considered the book sacred scripture both before and after councils that formally declared it part of the biblical canon. In a 405 letter, Pope Innocent I

Pope Innocent I () was the bishop of Rome from 401 to his death on 12 March 417. From the beginning of his papacy, he was seen as the general arbitrator of ecclesiastical disputes in both the East and the West. He confirmed the prerogatives of ...

declared it part of the Christian canon. In Jerome's ''Prologue to Judith'',: Canonicity: "..."the Synod of Nicaea is said to have accounted it as Sacred Scripture" (Praef. in Lib.). It is true that no documents about the canon survive in the Canons of Nicaea, and it is uncertain whether St. Jerome is referring to the use made of the book in the discussions of the council, or whether he was misled by some spurious canons attributed to that council" he claims that the Book of Judith was "found by the Nicene Council to have been counted among the number of the Sacred Scriptures". No such declaration has been found in the Canons of Nicaea, and it is uncertain whether Jerome was referring to the book's use during the council's discussion or spurious canons attributed to that council.

Regardless of Judith's status at Nicaea, the book was also accepted as scripture by the councils of Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

(382), Hippo

The hippopotamus (''Hippopotamus amphibius;'' ; : hippopotamuses), often shortened to hippo (: hippos), further qualified as the common hippopotamus, Nile hippopotamus and river hippopotamus, is a large semiaquatic Mammal, mammal native to su ...

(393), Carthage

Carthage was an ancient city in Northern Africa, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classic ...

(397), and Florence

Florence ( ; ) is the capital city of the Italy, Italian region of Tuscany. It is also the most populated city in Tuscany, with 362,353 inhabitants, and 989,460 in Metropolitan City of Florence, its metropolitan province as of 2025.

Florence ...

(1442) and eventually dogmatically defined as canonical by the Roman Catholic Church in 1546 in the Council of Trent

The Council of Trent (), held between 1545 and 1563 in Trent (or Trento), now in northern Italy, was the 19th ecumenical council of the Catholic Church. Prompted by the Protestant Reformation at the time, it has been described as the "most ...

. However, Rome, Hippo, and Carthage were all local councils (unlike Nicaea, an ecumenical council). The Eastern Orthodox Church also accepts Judith as inspired scripture; this was confirmed in the Synod of Jerusalem in 1672. The canonicity of Judith is typically rejected by Protestants, who accept as the Old Testament only those books that are found in the Jewish canon. Martin Luther

Martin Luther ( ; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, Theology, theologian, author, hymnwriter, professor, and former Order of Saint Augustine, Augustinian friar. Luther was the seminal figure of the Reformation, Pr ...

viewed the book as an allegory, but listed it as the first of the eight writings in his Apocrypha, which is located between the Old Testament and New Testament of the Luther Bible

The Luther Bible () is a German language Bible translation by the Protestant reformer Martin Luther. A New Testament translation by Luther was first published in September 1522; the completed Bible contained 75 books, including the Old Testament ...

. Though Lutheranism views the Book of Judith as non-canonical, it is deemed edifying for matters of morality, as well as devotional use. In Anglicanism

Anglicanism, also known as Episcopalianism in some countries, is a Western Christianity, Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the ...

, it has the intermediate authority of the Apocrypha of the Old Testament and is regarded as useful or edifying, but is not to be taken as a basis for establishing doctrine.

Judith is also referred to in chapter 28 of 1 Meqabyan, a book considered canonical in the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church

The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church () is the largest of the Oriental Orthodox Churches. One of the few Christian churches in Africa originating before European colonization of the continent, the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church dates bac ...

.

Contents

Plot summary

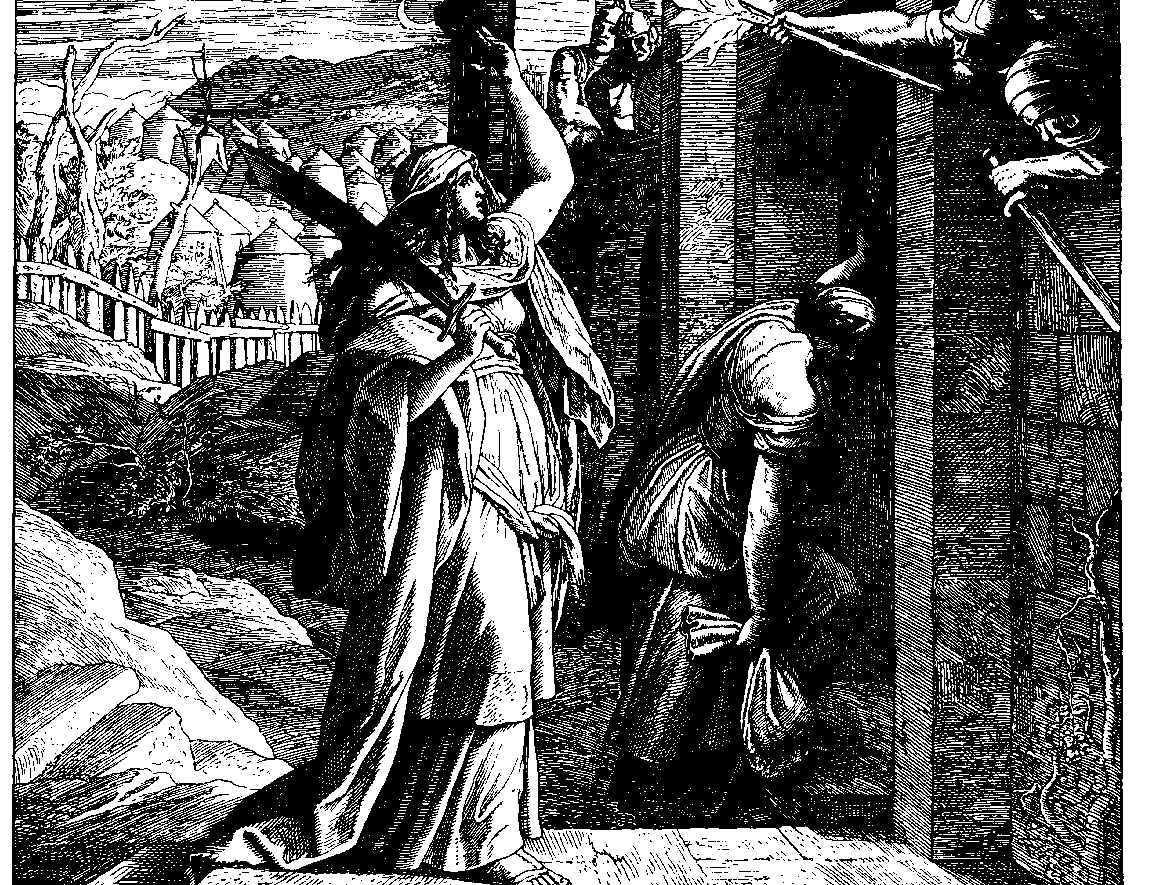

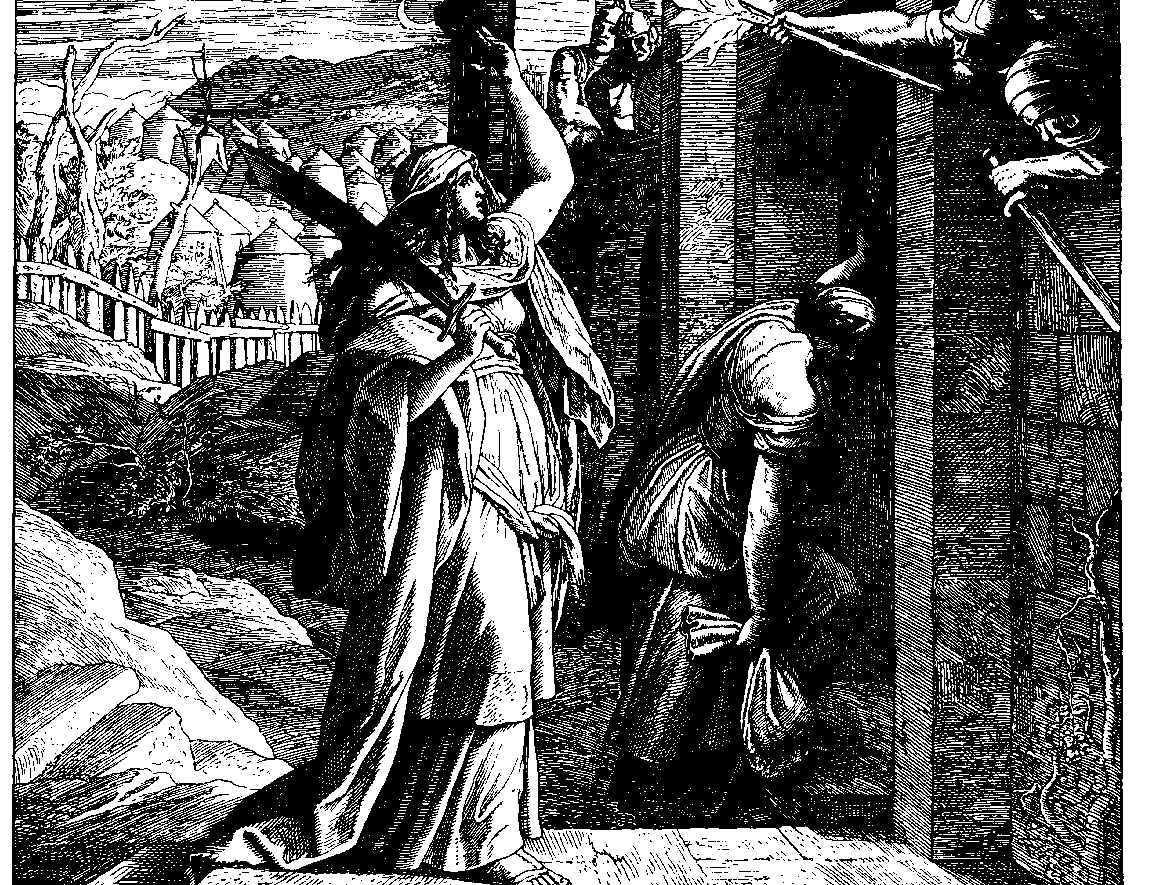

The story revolves around Judith, a daring and beautiful widow, who is upset with her Judean countrymen for not trusting God to deliver them from their foreign conquerors. She goes with her loyal maid to the camp of the Assyrian general,Holofernes

Holofernes (; ) was an invading Assyrian general in the Book of Judith, who was beheaded by Judith, who entered his camp and decapitated him while he was intoxicated.

Etymology

The name 'Holofernes' is derived from the Old Persian name , meanin ...

, with whom she slowly ingratiates herself, promising him information on the people of Israel

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

. Gaining his trust, she is allowed access to his tent one night as he lies in a drunken stupor. She decapitates him, then takes his head back to her fearful countrymen. The Assyrians

Assyrians (, ) are an ethnic group indigenous to Mesopotamia, a geographical region in West Asia. Modern Assyrians share descent directly from the ancient Assyrians, one of the key civilizations of Mesopotamia. While they are distinct from ot ...

, having lost their leader, disperse, and Israel is saved. Though she is courted by many, Judith remains unmarried for the rest of her life.

Literary structure

The Book of Judith can be split into two parts or "acts" of approximately equal length. Chapters 1–7 describe the rise of the threat to Israel, led by king Nebuchadnezzar and his general Holofernes, and is concluded as Holofernes' worldwide campaign has converged at the mountain pass where Judith's village,Bethulia

Bethulia (, ''Baituloua''; Hebrew: wikt:בתוליה, בתוליה) is a biblical "city whose deliverance by Judith, when besieged by Holofernes, forms the subject of the ''Book of Judith''."

Etymology

The name "Bethulia" in Hebrew can be assoc ...

, is located. Chapters 8–16 then introduce Judith and depict her heroic actions to save her people. The first part, although at times tedious in its description of the military developments, develops important themes by alternating battles with reflections and rousing action with rest. In contrast, the second half is devoted mainly to Judith's strength of character and the beheading scene.

The New Oxford Annotated Apocrypha identifies a clear chiastic pattern in both "acts", in which the order of events is reversed at a central moment in the narrative (i.e., abcc'b'a').

Part I (1:1–7:23)

A. Campaign against disobedient nations; the people surrender (1:1–2:13)

:B. Israel is "greatly terrified" (2:14–3:10)

::C. Joakim

Joakim or Joacim is a male given name primarily used in Scandinavian languages, Estonian and Finnish. It is derived from a transliteration of the Hebrew יהוֹיָקִים, and literally means "lifted by Jehovah".

In the Old Testament, Jehoi ...

prepares for war (4:1–15)

:::D. Holofernes talks with Achior (5:1–6.9)

::::E. Achior is expelled by Assyrians (6:10–13)

::::E'. Achior is received in the village of Bethulia (6:14–15)

:::D'. Achior talks with the people (6:16–21)

::C'. Holofernes prepares for war (7:1–3)

:B'. Israel is "greatly terrified" (7:4–5)

A'. Campaign against Bethulia; the people want to surrender (7:6–32)

Part II (8:1–16:25)

A. Introduction of Judith (8:1–8)

:B. Judith plans to save Israel

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan to the east, Egypt to the south-west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Isr ...

(8:9–10:8), including her extended prayer

File:Prayers-collage.png, 300px, alt=Collage of various religionists praying – Clickable Image, Collage of various religionists praying ''(Clickable image – use cursor to identify.)''

rect 0 0 1000 1000 Shinto festivalgoer praying in front ...

(9:1–14)

::C. Judith and her maid leave Bethulia (10:9–10)

:::D. Judith beheads Holofernes (10:11–13:10a)

::C'. Judith and her maid return to Bethulia (13.10b–11)

:B'. Judith plans the destruction of Israel's enemy (13:12–16:20)

A'. Conclusion about Judith (16.1–25)

Similarly, parallels within Part II are noted in comments within the New American Bible Revised Edition: Judith summons a town meeting in Judith 8:10 in advance of her expedition and is acclaimed by such a meeting in Judith 13:12–13; Uzziah blesses Judith in advance in Judith 8:5 and afterwards in Judith 13:18–20.

::C'. Judith and her maid return to Bethulia (13.10b–11)

:B'. Judith plans the destruction of Israel's enemy (13:12–16:20)

A'. Conclusion about Judith (16.1–25)

Similarly, parallels within Part II are noted in comments within the New American Bible Revised Edition: Judith summons a town meeting in Judith 8:10 in advance of her expedition and is acclaimed by such a meeting in Judith 13:12–13; Uzziah blesses Judith in advance in Judith 8:5 and afterwards in Judith 13:18–20.

Literary genre

Most contemporary exegetes, such as Biblical scholar Gianfranco Ravasi, generally tend to ascribe Judith to one of several contemporaneous literary genres, reading it as an extended parable in the form of ahistorical fiction

Historical fiction is a literary genre in which a fictional plot takes place in the Setting (narrative), setting of particular real past events, historical events. Although the term is commonly used as a synonym for historical fiction literatur ...

, or a propaganda

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loaded l ...

literary work from the days of the Seleucid oppression.

It has also been called "an example of the ancient Jewish novel in the Greco-Roman period". Other scholars note that Judith fits within and even incorporates the genre of "salvation traditions" from the Old Testament, particularly the story of Deborah

According to the Book of Judges, Deborah (, ''Dəḇōrā'') was a prophetess of Judaism, the fourth Judge of pre-monarchic Israel, and the only female judge mentioned in the Hebrew Bible. Many scholars contend that the phrase, "a woman of Lap ...

and Jael

Jael () or Yael (' ''Yāʿēl'') is a heroine of the Bible who aids the Israelites in their war with King Jabin of the city of Tel Hazor, Hazor in Canaan by killing Sisera, the commander of Jabin's army. This episode is depicted in Judges 4, cha ...

(Judges

A judge is an official who presides over a court.

Judge or Judges may also refer to:

Roles

*Judge, an alternative name for an adjudicator in a competition in theatre, music, sport, etc.

*Judge, an alternative name/aviator call sign for a membe ...

4–5), who seduced and inebriated the Canaanite commander Sisera

Sisera ( ''Sīsərāʾ'') was commander of the Canaanite army of King Jabin of Hazor, who is mentioned in of the Hebrew Bible. After being defeated by the forces of the Israelite tribes of Zebulun and Naphtali under the command of Barak and ...

before hammering a tent-peg into his forehead.

There are also thematic connections to the revenge of Simeon

Simeon () is a given name, from the Hebrew (Biblical Hebrew, Biblical ''Šimʿon'', Tiberian vocalization, Tiberian ''Šimʿôn''), usually transliterated in English as Shimon. In Greek, it is written Συμεών, hence the Latinized spelling Sy ...

and Levi

Levi ( ; ) was, according to the Book of Genesis, the third of the six sons of Jacob and Leah (Jacob's third son), and the founder of the Israelites, Israelite Tribe of Levi (the Levites, including the Kohanim) and the great-grandfather of Aaron ...

on Shechem after the rape of Dinah

In the Book of Genesis, Dinah (; ) was the seventh child and only named daughter of Leah and Jacob. The episode of her rape by Shechem, son of a Canaanite or Hivite prince, and the subsequent revenge of her brothers Simeon and Levi, commonly ...

in Genesis 34.

In the Christian West from the patristic

Patristics, also known as Patrology, is a branch of theological studies focused on the writings and teachings of the Church Fathers, between the 1st to 8th centuries CE. Scholars analyze texts from both orthodox and heretical authors. Patristics em ...

period on, Judith was invoked in a wide variety of texts as a multi-faceted allegorical figure. As a "''Mulier sancta''", she personified the Church and many virtues

A virtue () is a trait of excellence, including traits that may be moral, social, or intellectual. The cultivation and refinement of virtue is held to be the "good of humanity" and thus is valued as an end purpose of life or a foundational pri ...

– Humility

Humility is the quality of being humble. The Oxford Dictionary, in its 1998 edition, describes humility as a low self-regard and sense of unworthiness. However, humility involves having an accurate opinion of oneself and expressing oneself mode ...

, Justice

In its broadest sense, justice is the idea that individuals should be treated fairly. According to the ''Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy'', the most plausible candidate for a core definition comes from the ''Institutes (Justinian), Inst ...

, Fortitude, Chastity

Chastity, also known as purity, is a virtue related to temperance. Someone who is ''chaste'' refrains from sexual activity that is considered immoral or from any sexual activity, according to their state of life. In some contexts, for exampl ...

(the opposite of Holofernes' vices

A vice is a practice, behaviour, habit or item generally considered morally wrong in the associated society. In more minor usage, vice can refer to a fault, a negative character trait, a defect, an infirmity, or a bad or unhealthy habit. Vices a ...

Pride

Pride is a human Emotion, secondary emotion characterized by a sense of satisfaction with one's Identity (philosophy), identity, performance, or accomplishments. It is often considered the opposite of shame or of humility and, depending on conte ...

, Tyranny

A tyrant (), in the modern English language, English usage of the word, is an autocracy, absolute ruler who is unrestrained by law, or one who has usurper, usurped a legitimate ruler's sovereignty. Often portrayed as cruel, tyrants may defen ...

, Decadence

Decadence was a late-19th-century movement emphasizing the need for sensationalism, egocentricity, and bizarre, artificial, perverse, and exotic sensations and experiences. By extension, it may refer to a decline in art, literature, science, ...

, Lust

Lust is an intense desire for something. Lust can take any form such as the lust for sexuality (see libido), money, or power. It can take such mundane forms as the lust for food (see gluttony) as distinct from the need for food or lust for red ...

) – and she was, like the other heroic women of the Hebrew scriptural tradition, made into a typological prefiguration of the Virgin Mary

Mary may refer to:

People

* Mary (name), a female given name (includes a list of people with the name)

Religion

* New Testament people named Mary, overview article linking to many of those below

* Mary, mother of Jesus, also called the Blesse ...

. Her gender made her a natural example of the biblical paradox of "strength in weakness"; she is thus paired with David

David (; , "beloved one") was a king of ancient Israel and Judah and the third king of the United Monarchy, according to the Hebrew Bible and Old Testament.

The Tel Dan stele, an Aramaic-inscribed stone erected by a king of Aram-Dam ...

and her beheading of Holofernes paralleled with that of Goliath

Goliath ( ) was a Philistines, Philistine giant in the Book of Samuel. Descriptions of Goliath's giant, immense stature vary among biblical sources, with texts describing him as either or tall. According to the text, Goliath issued a challen ...

– both deeds saved the Covenant People from a militarily superior enemy.

Main characters

Judith, theprotagonist

A protagonist () is the main character of a story. The protagonist makes key decisions that affect the plot, primarily influencing the story and propelling it forward, and is often the character who faces the most significant obstacles. If a ...

of the book, introduced in chapter 8 as a God-fearing woman, she is the daughter of Merari, a Simeonite, and widow of a certain Manasseh

Manasseh () is both a given name and a surname. Its variants include Manasses and Manasse.

Notable people with the name include:

Surname

* Ezekiel Saleh Manasseh (died 1944), Singaporean rice and opium merchant and hotelier

* Jacob Manasseh ( ...

or Manasses, a wealthy farmer. She sends her maid or "waitingwoman" to summon Uzziah so she can challenge his decision to capitulate to the Assyrians if God has not rescued the people of Bethulia within five days, and she uses her charm to become an intimate friend of Holofernes, but beheads him allowing Israel to counter-attack the Assyrians. Judith's maid, not named in the story, remains with her throughout the narrative and is given her freedom as the story ends.

Holofernes

Holofernes (; ) was an invading Assyrian general in the Book of Judith, who was beheaded by Judith, who entered his camp and decapitated him while he was intoxicated.

Etymology

The name 'Holofernes' is derived from the Old Persian name , meanin ...

, the antagonist

An antagonist is a character in a story who is presented as the main enemy or rival of the protagonist and is often depicted as a villain.Nineveh

Nineveh ( ; , ''URUNI.NU.A, Ninua''; , ''Nīnəwē''; , ''Nīnawā''; , ''Nīnwē''), was an ancient Assyrian city of Upper Mesopotamia, located in the modern-day city of Mosul (itself built out of the Assyrian town of Mepsila) in northern ...

in his resistance against Cheleud and the king of Media, until Israel also becomes a target of his military campaign. Judith's courage and charm occasion his death.

Nebuchadnezzar

Nebuchadnezzar II, also Nebuchadrezzar II, meaning "Nabu, watch over my heir", was the second king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, ruling from the death of his father Nabopolassar in 605 BC to his own death in 562 BC. Often titled Nebuchadnezzar ...

, the king of Nineveh and Assyria. He is so proud that he wants to affirm his strength as a sort of divine power, although Holofernes, his Turtan (commanding general), goes beyond the king's orders when he calls on the western nations to "worship only Nebuchadnezzar, and ... invoke him as a god". Holofernes is ordered to take revenge on those who refused to ally themselves with Nebuchadnezzar.

Achior, an Ammon

Ammon (; Ammonite language, Ammonite: 𐤏𐤌𐤍 ''ʻAmān''; '; ) was an ancient Semitic languages, Semitic-speaking kingdom occupying the east of the Jordan River, between the torrent valleys of Wadi Mujib, Arnon and Jabbok, in present-d ...

ite leader at Nebuchadnezzar's court; in chapter 5 he summarises the history of Israel

The history of Israel covers an area of the Southern Levant also known as Canaan, Palestine (region), Palestine, or the Holy Land, which is the geographical location of the modern states of Israel and Palestine. From a prehistory as part ...

and warns the king of Assyria of the power of their God, the "God of heaven", but is mocked. He is protected by the people of Bethulia and is Judaized , and circumcised on hearing what Judith has accomplished.

Bagoas, or Vagao (Vulgate), the eunuch

A eunuch ( , ) is a male who has been castration, castrated. Throughout history, castration often served a specific social function. The earliest records for intentional castration to produce eunuchs are from the Sumerian city of Lagash in the 2 ...

who had charge over Holofernes' personal affairs. His name is Persian for a eunuch. Haydock, G. L.Judith 12: Notes & Commentary

accessed 31 October 2022 He brought in Judith to recline with Holofernes and was the first one who discovered his beheading. Uzziah or Oziah, governor of Bethulia; together with Cabri and Carmi, he rules over Judith's city. When the city is besieged by the Assyrians and the water supply dries up, he agrees to the people's call to surrender if God has not rescued them within five days, a decision challenged as "rash" by Judith.

Judith's prayer

Chapter 9 constitutes Judith's "extended prayer", Levine, A., ''41. Judith'', in Barton, J. and Muddiman, J. (2001)The Oxford Bible Commentary

, p. 638 "loudly proclaimed" in advance of her actions in the following chapters. This runs to 14 verses in English versions, 19 verses in the Vulgate.

Historicity of Judith

Today, it is generally accepted that the Book of Judith's

Today, it is generally accepted that the Book of Judith's historicity

Historicity is the historical actuality of persons and events, meaning the quality of being part of history instead of being a historical myth, legend, or fiction. The historicity of a claim about the past is its factual status. Historicity deno ...

is dubious. The fictional nature "is evident from its blending of history and fiction, beginning in the very first verse, and is too prevalent thereafter to be considered the result of mere historical mistakes." The names of people are either unknown to history or appear to be anachronistic, and many of the place names are also unknown. While the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops currently considers the book to be historical fiction, the Catholic Church long considered the book to be a historical document, and it is included with the other historical books in the Old Testament of Catholic Bibles. For this reason, there have been various attempts by both scholars and clergy to understand the characters and events in the Book as either an allegorical representation of actual events, or a historical document that had been altered or translated improperly. The practice of changing names has been observed in documents from the Second Temple period

The Second Temple period or post-exilic period in Jewish history denotes the approximately 600 years (516 BCE – 70 CE) during which the Second Temple stood in the city of Jerusalem. It began with the return to Zion and subsequent reconstructio ...

, such as the Damascus Document

The Damascus Document is an ancient Hebrew text known from both the Cairo Geniza and the Dead Sea Scrolls.Philip R. Davies, "Damascus Document", in Eric M. Meyers (ed.), ''The Oxford Encyclopedia of Archaeology in the Near East'' (Oxford Universit ...

, which apparently contains references to an uncertain location referred to by the pseudonym of "Damascus". The writings of the Jewish historian Flavius Josephus

Flavius Josephus (; , ; ), born Yosef ben Mattityahu (), was a History of the Jews in the Roman Empire, Roman–Jewish historian and military leader. Best known for writing ''The Jewish War'', he was born in Jerusalem—then part of the Judaea ...

also frequently differ from the Biblical record regarding the names of the high priests of Israel. Elsewhere in the Bible, there are also names of rulers that are unknown to history, such as Darius the Mede

Darius the Mede is mentioned in the Book of Daniel as King of Babylon between Belshazzar and Cyrus the Great, but he is not known to secular history and there is no space in the historical timeline between those two verified rulers. Belshazzar, w ...

from the Book of Daniel

The Book of Daniel is a 2nd-century BC biblical apocalypse with a 6th-century BC setting. It is ostensibly a narrative detailing the experiences and Prophecy, prophetic visions of Daniel, a Jewish Babylonian captivity, exile in Babylon ...

or Ahasuerus

Ahasuerus ( ; , commonly ''Achashverosh''; , in the Septuagint; in the Vulgate) is a name applied in the Hebrew Bible to three rulers of Ancient Persia and to a Babylonian official (or Median king) first appearing in the Tanakh in the Book of ...

from the Book of Esther

The Book of Esther (; ; ), also known in Hebrew language, Hebrew as "the Scroll" ("the wikt:מגילה, Megillah"), is a book in the third section (, "Writings") of the Hebrew Bible. It is one of the Five Megillot, Five Scrolls () in the Hebr ...

. The large size of the Assyrian army and the large size of the Median walls in the book have also been criticized, but both of these have been attested to elsewhere in the Bible and in secular historical records. The Assyrian army that besieged Jerusalem in 2 Kings 19 was said to have been 185,000 strong, a number several tens of thousands larger than the Assyrian army described in the book of Judith. Also, the Greek historian Herodotus

Herodotus (; BC) was a Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus (now Bodrum, Turkey), under Persian control in the 5th century BC, and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria, Italy. He wrote the '' Histori ...

described the walls of Babylon to have been similar in size and extravagance to the walls of Ecbatana in the book of Judith. Herodotus's account was corroborated by similar accounts of the scale of the walls of Babylon by the historians Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called "Gnaeus Pompeius Strabo, Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-si ...

, Ctesias

Ctesias ( ; ; ), also known as Ctesias of Cnidus, was a Greek physician and historian from the town of Cnidus in Caria, then part of the Achaemenid Empire.

Historical events

Ctesias, who lived in the fifth century BC, was physician to the Acha ...

, and Cleitarchus

Cleitarchus or Clitarchus () was one of the historians of Alexander the Great. Son of the historian Dinon of Colophon, he spent a considerable time at the court of Ptolemy Lagus. He was active in the mid to late 4th century BCE.

Quintilian ('' ...

. The identity of the "Nebuchadnezzar" in the book has been debated for thousands of years and various rulers have been proposed by scholars, including Ashurbanipal

Ashurbanipal (, meaning " Ashur is the creator of the heir")—or Osnappar ()—was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 669 BC to his death in 631. He is generally remembered as the last great king of Assyria. Ashurbanipal inherited the th ...

, Artaxerxes III

Ochus ( ), known by his dynastic name Artaxerxes III ( ; ), was King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire from 359/58 to 338 BC. He was the son and successor of Artaxerxes II and his mother was Stateira.

Before ascending the throne Artaxerxes was ...

, Tigranes the Great

Tigranes II, more commonly known as Tigranes the Great (''Tigran Mets'' in Armenian language, Armenian; 140–55 BC), was a king of Kingdom of Armenia (antiquity), Armenia. A member of the Artaxiad dynasty, he ruled from 95 BC to 55 BC. Under hi ...

, Antiochus IV Epiphanes

Antiochus IV Epiphanes ( 215 BC–November/December 164 BC) was king of the Seleucid Empire from 175 BC until his death in 164 BC. Notable events during Antiochus' reign include his near-conquest of Ptolemaic Egypt, his persecution of the Jews of ...

, Cambyses II

Cambyses II () was the second King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, reigning 530 to 522 BCE. He was the son of and successor to Cyrus the Great (); his mother was Cassandane. His relatively brief reign was marked by his conquests in North Afric ...

, Xerxes I

Xerxes I ( – August 465 BC), commonly known as Xerxes the Great, was a List of monarchs of Persia, Persian ruler who served as the fourth King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, reigning from 486 BC until his assassination in 465 BC. He was ...

, and Darius the Great

Darius I ( ; – 486 BCE), commonly known as Darius the Great, was the third King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, reigning from 522 BCE until his death in 486 BCE. He ruled the empire at its territorial peak, when it included much of West A ...

.

Identification of Nebuchadnezzar with Ashurbanipal

For hundreds of years, the most generally accepted view within the Catholic Church is that the book of Judith occurs during the reign ofAshurbanipal

Ashurbanipal (, meaning " Ashur is the creator of the heir")—or Osnappar ()—was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 669 BC to his death in 631. He is generally remembered as the last great king of Assyria. Ashurbanipal inherited the th ...

, a notoriously cruel and brutal Assyrian king whose reign was marked by various military campaigns and invasions. Ashurbanipal ruled the Neo-Assyrian Empire

The Neo-Assyrian Empire was the fourth and penultimate stage of ancient Assyrian history. Beginning with the accession of Adad-nirari II in 911 BC, the Neo-Assyrian Empire grew to dominate the ancient Near East and parts of South Caucasus, Nort ...

from Nineveh in 668 to 627 BCE. The Challoner Douay-Rheims Bible states that the events of the book begin in A.M. 3347, or Ante C. 657, which would be during the reign of Ashurbanipal. This would be the twelfth year of Ashurbanipal's reign, which lines up with the book of Judith beginning in the twelfth year of "Nebuchadnezzar". If the rest of the book occurs in the seventeenth and eighteenth years of Ashurbanipal, the years would be 653 and 652 BCE, corresponding to revolts and military campaigns across Ashurbanipal's empire. The traditional Catholic view that the book dates to the reign of Manasseh corresponds to Ashurbanipal's reign, and Ashurbanipal's records name Manasseh as one of a number of vassals who assisted his campaign against Egypt. The profanation of the temple described in ''Judith'' 4:3 might have been that under king Hezekiah

Hezekiah (; ), or Ezekias (born , sole ruler ), was the son of Ahaz and the thirteenth king of Kingdom of Judah, Judah according to the Hebrew Bible.Stephen L Harris, Harris, Stephen L., ''Understanding the Bible''. Palo Alto: Mayfield. 1985. "G ...

(see 2 Chronicles 33:18–19), who reigned between c. 715 and 686 BCE. And in that same verse, the return from the dispersion (often assumed to refer to the Babylonian captivity

The Babylonian captivity or Babylonian exile was the period in Jewish history during which a large number of Judeans from the ancient Kingdom of Judah were forcibly relocated to Babylonia by the Neo-Babylonian Empire. The deportations occurred ...

) might refer to the chaos that resulted in people fleeing Jerusalem after Manasseh was taken captive by the Assyrians. The reinforcement of the cities as described in ''Judith'' 4:5 matches up with the reinforcement that happened in response to the Assyrians under Manasseh. ''Judith'' 4:6 claims that the High Priest of Israel

In Judaism, the High Priest of Israel (, lit. ‘great priest’; Aramaic: ''Kahana Rabba'') was the head of the Israelite priesthood. He played a unique role in the worship conducted in the Tabernacle and later in the Temple in Jerusalem, ...

was in charge of the country at the time. However, it is generally assumed that the book takes place after Manasseh's return from captivity in Assyria and his subsequent repentance. Nicolaus Serarius, Giovanni Menochio and Thomas Worthington speculated that Manasseh was busy fortifying Jerusalem at the time (which also fits with 2 Chronicles 33) and left the matters of the rest of the Israelites to the high priest. Others, such as Houbigant and Haydock, speculate that the events of the book occurred while Manasseh was still captive in Babylon

Babylon ( ) was an ancient city located on the lower Euphrates river in southern Mesopotamia, within modern-day Hillah, Iraq, about south of modern-day Baghdad. Babylon functioned as the main cultural and political centre of the Akkadian-s ...

. Whatever the case, it was a typical policy of the time for the Israelites to follow the high priest if the king could not or would not lead. Manasseh is thought by most scholars to have joined a widespread rebellion against Ashurbanipal that was led by his brother, Šamaš-šuma-ukin. Contemporary sources make reference to the many allies of Chaldea

Chaldea () refers to a region probably located in the marshy land of southern Mesopotamia. It is mentioned, with varying meaning, in Neo-Assyrian cuneiform, the Hebrew Bible, and in classical Greek texts. The Hebrew Bible uses the term (''Ka� ...

(governed by Šamaš-šuma-ukin), including the Kingdom of Judah

The Kingdom of Judah was an Israelites, Israelite kingdom of the Southern Levant during the Iron Age. Centered in the highlands to the west of the Dead Sea, the kingdom's capital was Jerusalem. It was ruled by the Davidic line for four centuries ...

, which were subjects of Assyria and are mentioned in the Book of Judith as victims of Ashurbanipal's Western campaign. The ''Encyclopædia Britannica

The is a general knowledge, general-knowledge English-language encyclopaedia. It has been published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. since 1768, although the company has changed ownership seven times. The 2010 version of the 15th edition, ...

'' identified "Judah" as one of the vassal kingdoms in Šamaš-šuma-ukin's rebel coalition against Ashurbanipal. The Cambridge Ancient History

''The Cambridge Ancient History'' is a multi-volume work of ancient history from Prehistory to Late Antiquity, published by Cambridge University Press. The first series, consisting of 12 volumes, was planned in 1919 by Irish historian J. B. Bur ...

also confirms that "several princes of Palestine

Palestine, officially the State of Palestine, is a country in West Asia. Recognized by International recognition of Palestine, 147 of the UN's 193 member states, it encompasses the Israeli-occupied West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and th ...

" supported Šamaš-šuma-ukin in the revolt against Ashurbanipal, which seemingly confirms Manasseh's involvement in the revolt. This would explain the reinforcement of the cities described in this book and why the Israelites and other western kingdoms rejected "Nebuchadnezzar's" order for conscription, because many of the vassal rulers of the west supported Šamaš-šuma-ukin.

It is of further interest that Šamaš-šuma-ukin's civil war broke out in 652 BCE, the eighteenth year of Ashurbanipal's reign. The book of Judith states that "Nebuchadnezzar" ravaged the western part of the empire in the eighteenth year of his reign. If the events of this book did occur during Ashurbanipal's reign, it is possible that Assyrians did not record it because they were preoccupied with Šamaš-šuma-ukin's revolt, which was not crushed for years to come. Ashurbanipal's successful crushing of Šamaš-šuma-ukin's civil war also prevented the Assyrians from retaking Egypt, which gained independence from Assyria around 655 BCE. Numerous theologians, including Antoine Augustin Calmet

Antoine Augustin Calmet, (; 26 February 167225 October 1757), a French Benedictine abbot, was born at Ménil-la-Horgne, then in the Duchy of Bar, part of the Holy Roman Empire (now the French department of Meuse, located in the region of Lor ...

, suspect that the ultimate goal of the western campaign was for the Assyrians to sack Egypt, because Holofernes appeared to be heading directly towards Egypt on his campaign through the west. If Calmet and others are correct in suspecting that Holofernes was intending to sack Egypt, this would give further evidence to the theory that the book is set during the reign of Ashurbanipal, who had previously sacked Thebes in 663 BCE. The view that the book of Judith was written during the reigns of Manasseh and Ashurbanipal was held by a great number of Catholic scholars, including Calmet, George Leo Haydock, Thomas Worthington Thomas or Tom Worthington may refer to:

*Thomas Worthington (Douai) (1549–1627), English Catholic priest and third President of Douai College

*Thomas Worthington (Dominican) (1671–1754), English Dominican friar and writer

*Thomas Worthington (g ...

, Richard Challoner, Giovanni Stefano Menochio

Giovanni Stefano Menochio (9 December 15754 February 1655) was an Italian Jesuit biblical scholar.

Life

Menochio was born at Padua, and entered the Society of Jesus on 25 May 1594. After the usual years of training and teaching the classics, ...

, Sixtus of Siena, Robert Bellarmine

Robert Bellarmine (; ; 4 October 1542 – 17 September 1621) was an Italian Jesuit and a cardinal of the Catholic Church. He was canonized a saint in 1930 and named Doctor of the Church, one of only 37. He was one of the most important figure ...

, Charles François Houbigant, Nicolaus Serarius, Pierre Daniel Huet

P. D. Huetius

Pierre Daniel Huet (; ; 8 February 1630 – 26 January 1721) was a French churchman and scholar, editor of the Delphin Classics, founder of the Académie de Physique in Caen (1662–1672) and Bishop of Soissons from 1685 to 1689 ...

and Bernard de Montfaucon

Dom Bernard de Montfaucon, O.S.B. (; 13 January 1655 – 21 December 1741) was a French Benedictine monk of the Congregation of Saint Maur. He was an astute scholar who founded the discipline of palaeography, as well as being an editor of w ...

. Many of these theologians are cited and quoted by Calmet in his own commentary on Judith, the "Commentaire littéral sur tous les livres de l'ancien et du nouveau testament". Calmet listed all of "the main objections that can be made against the truth of Judith's Story" and spent the rest of his commentary on the book addressing them, stating: "But all this did not bother Catholic writers. There were a large number of them who answered it expertly, and who undertook to show that there is nothing incompatible in this history, neither with Scripture, nor even with profane (secular) history". There were other Catholic writers who held this view as well, such as Fulcran Vigouroux, who went even farther, identifying the battle between "Nebuchadnezzar, king of the Assyrians" and "Arphaxad, the king of the Medes" as the battle that occurred between Ashurbanipal and Phraortes

Phraortes, son of Deioces, was the second king of the Median kingdom.

Like his father Deioces, Phraortes started wars against Assyria, but was defeated and killed by the Assyrian king, probably Ashurbanipal (r. 669-631 BC).

Biography

All an ...

. This battle occurred during the seventeenth year of Ashurbanipal's reign, and the book of Judith states that this battle occurred in the seventeenth year of "Nebuchadnezzar's" reign. Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet

Jacques-Bénigne Lignel Bossuet (; 27 September 1627 – 12 April 1704) was a French Bishop (Catholic Church), bishop and theology, theologian. Renowned for his sermons, addresses and literary works, he is regarded as a brilliant orator and lit ...

expressed a similar view regarding this. The scholars used specific examples from the text that line up with Manasseh's reign. As argued by Vigouroux, the two battles mentioned in the Septuagint version of the Book of Judith are a reference to the clash of the two empires in 658–657 and to Phraortes' death in battle in 653, after which Ashurbanipal continued his military actions with a large campaign starting with the Battle of the Ulai River (653 BCE) in the eighteenth year of his reign. The King of the "Elymeans" ( Elamites), called "Arioch", is referenced in ''Judith'' 1:6. If the twelfth year of "Nebuchadnezzar" is to be identified as the twelfth year of Ashurbanipal, this Arioch would be identified as Teumman, who rebelled against Ashurbanipal on many occasions, eventually being killed at the Battle of the Ulai in 653 BCE, around the time Catholic theologians place "Nebuchadnezzar's" western campaign.

The identification of "Nebuchadnezzar" with Ashurbanipal was so widespread that it was the only identification in English Catholic Bibles for several hundred years. The 1738 Challoner revision of the Douay Rheims Bible and the Haydock Biblical Commentary specifically declare that "Nabuchodonosor" was "known as 'Saosduchin' to profane historians and succeeded 'Asarhaddan' in the kingdom of the Assyrians". This could only have been Ashurbanipal, as he was the successor of Esarhaddon, his father. It is unclear where the name "Saosduchin" came from, although it is possible that it was derived from the Canon of Kings The Canon of Kings was a dated list of kings used by ancient astronomers as a convenient means to date astronomical phenomena, such as eclipses. For a period, the Canon was preserved by the astronomer Claudius Ptolemy, and is thus known sometimes ...

by the astronomer Claudius Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; , ; ; – 160s/170s AD) was a Greco-Roman mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were important to later Byzantine, Islamic, and ...

, who wrote in Greek that " Saosdouchinos" followed " Asaradinos" as the king of Assyria. While influential, Ptolemy's record is not perfect, and Ptolemy likely got Ashurbanipal confused with his brother, Šamaš-šuma-ukin, who ruled over Babylon, not Assyria. This would be a plausible explanation for the origin of the Greek name "Saosduchin". However, while Nebuchadnezzar and Ashurbanipal's campaigns show clear and direct parallels, the main incident of Judith's intervention has not been found in any record aside from this book. An additional difficulty with this theory is that the reasons for the name changes are difficult to understand, unless the text was transmitted without character names before they were by a later copyist or translator, who lived centuries later. Catholic apologist Jimmy Akin argues the possibility that the book of Judith is a roman à clef

A ''roman à clef'' ( ; ; ) is a novel about real-life events that is overlaid with a façade of fiction. The fictitious names in the novel represent real people and the "key" is the relationship between the non-fiction and the fiction. This m ...

, a historical record with different names for people and places. Ashurbanipal is never referenced by name in the Bible, except perhaps for the corrupt form " Asenappar" in 2 Chronicles

The Book of Chronicles ( , "words of the days") is a book in the Hebrew Bible, found as two books (1–2 Chronicles) in the Christian Old Testament. Chronicles is the final book of the Hebrew Bible, concluding the third section of the Jewish Tan ...

and Ezra

Ezra ( fl. fifth or fourth century BCE) is the main character of the Book of Ezra. According to the Hebrew Bible, he was an important Jewish scribe (''sofer'') and priest (''kohen'') in the early Second Temple period. In the Greek Septuagint, t ...

4:10 or the anonymous title "The King of Assyria" in 2 Chronicles

The Book of Chronicles ( , "words of the days") is a book in the Hebrew Bible, found as two books (1–2 Chronicles) in the Christian Old Testament. Chronicles is the final book of the Hebrew Bible, concluding the third section of the Jewish Tan ...

( 33:11), which means his name might have never been recorded by Jewish historians, which could explain the lack of his name in the book of Judith.

Identification of Nebuchadnezzar with Artaxerxes III Ochus

The identity of Nebuchadnezzar was unknown to theChurch Fathers

The Church Fathers, Early Church Fathers, Christian Fathers, or Fathers of the Church were ancient and influential Christian theologians and writers who established the intellectual and doctrinal foundations of Christianity. The historical peri ...

, but some of them attempted an improbable identification with Artaxerxes III Ochus

Ochus ( ), known by his dynastic name Artaxerxes III ( ; ), was King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire from 359/58 to 338 BC. He was the son and successor of Artaxerxes II and his mother was Stateira.

Before ascending the throne Artaxerxes was ...

(359–338 BCE), not on the basis of the character of the two rulers, but due to the presence of a "Holofernes" and a "Bagoas" in Ochus' army.Noah Calvin Hirschy, ''Artaxerxes III Ochus and His Reign'', p. 81 (Univ. of Chicago Press 1909). This view also gained currency with scholarship in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. However, due to discrepancies between Artaxerxes's reign and the events in the book of Judith, this theory has largely been abandoned.

Identification of Nebuchadnezzar with Tigranes the Great

Modern scholars argue in favor of a 2nd–1st century context for the Book of Judith, understanding it as a sort of roman à clef—i.e., a literary fiction whose characters stand for some real historical figure, generally contemporary to the author. In the case of the Book of Judith, Biblical scholar Gabriele Boccaccini identified Nebuchadnezzar withTigranes the Great

Tigranes II, more commonly known as Tigranes the Great (''Tigran Mets'' in Armenian language, Armenian; 140–55 BC), was a king of Kingdom of Armenia (antiquity), Armenia. A member of the Artaxiad dynasty, he ruled from 95 BC to 55 BC. Under hi ...

(140–56 BCE), a powerful King of Armenia

This is a list of the monarchs of Armenia, rulers of the ancient Kingdom of Armenia (antiquity), Kingdom of Armenia (336 BC – AD 428), the medieval Bagratid Armenia, Kingdom of Armenia (884–1045), various lesser Armenian kingdoms (908–1170) ...

who, according to Josephus

Flavius Josephus (; , ; ), born Yosef ben Mattityahu (), was a Roman–Jewish historian and military leader. Best known for writing '' The Jewish War'', he was born in Jerusalem—then part of the Roman province of Judea—to a father of pr ...

and Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called "Gnaeus Pompeius Strabo, Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-si ...

, conquered all of the lands identified by the Biblical author in Judith. Under this theory, the story, although fictional, would be set in the time of Queen Salome Alexandra

Salome Alexandra, also ''Shlomtzion'', ''Shelamzion'' (; , ''Šəlōmṣīyyōn'', "peace of Zion"; 141–67 BC), was a regnant queen of Judaea, one of only three women in Jewish historical tradition to rule over the country, the other tw ...

, the only Jewish regnant queen, who reigned over Judea from 76 to 67 BCE.

Like Judith, the Queen had to face the menace of a foreign king who had a tendency to destroy the temples of other religions. Both women were widows whose strategical and diplomatic skills helped in the defeat of the invader. Both stories seem to be set at a time when the temple had recently been rededicated, which is the case after Judas Maccabee

Judas Maccabaeus or Maccabeus ( ), also known as Judah Maccabee (), was a Jewish priest (''kohen'') and a son of the priest Mattathias. He led the Maccabean Revolt against the Seleucid Empire (167–160 BCE).

The Jewish holiday of Hanukkah ("Ded ...

killed Nicanor and defeated the Seleucids

The Seleucid Empire ( ) was a Greek state in West Asia during the Hellenistic period. It was founded in 312 BC by the Macedonian general Seleucus I Nicator, following the division of the Macedonian Empire founded by Alexander the Great, ...

. The territory of Judean occupation includes the territory of Samaria

Samaria (), the Hellenized form of the Hebrew name Shomron (), is used as a historical and Hebrew Bible, biblical name for the central region of the Land of Israel. It is bordered by Judea to the south and Galilee to the north. The region is ...

, something which was possible in Maccabean times only after John Hyrcanus

John Hyrcanus (; ; ) was a Hasmonean (Maccabee, Maccabean) leader and Jewish High Priest of Israel of the 2nd century BCE (born 164 BCE, reigned from 134 BCE until he died in 104 BCE). In rabbinic literature he is often referred to as ''Yoḥana ...

reconquered those territories. Thus, the presumed Sadducee

The Sadducees (; ) were a sect of Jews active in Judea during the Second Temple period, from the second century BCE to the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE. The Sadducees are described in contemporary literary sources in contrast to ...

author of Judith would desire to honor the great (Pharisee) Queen who tried to keep both Sadducees and Pharisees

The Pharisees (; ) were a Jews, Jewish social movement and school of thought in the Levant during the time of Second Temple Judaism. Following the Siege of Jerusalem (AD 70), destruction of the Second Temple in 70 AD, Pharisaic beliefs became ...

united against the common menace.

Location of Bethulia

Although there is no historically recorded "Bethulia", the book of Judith gives an extremely precise location for where the city is located, and there are several possible candidates of ancient towns in that area that are now ruins. It has widely been speculated that, based on location descriptions in the book, that the most plausible historical site for Bethulia isShechem

Shechem ( ; , ; ), also spelled Sichem ( ; ) and other variants, was an ancient city in the southern Levant. Mentioned as a Canaanite city in the Amarna Letters, it later appears in the Hebrew Bible as the first capital of the Kingdom of Israe ...

. Shechem is a large city in the hill-country of Samaria, on the direct road from Jezreel to Jerusalem, lying in the path of the enemy, at the head of an important pass and is a few hours south of Geba. The Jewish Encyclopedia

''The Jewish Encyclopedia: A Descriptive Record of the History, Religion, Literature, and Customs of the Jewish People from the Earliest Times to the Present Day'' is an English-language encyclopedia containing over 15,000 articles on the ...

subscribes to the theory, suggesting that it was called by a pseudonym because of the historical animosity between the Jews and Samaritans. The Jewish Encyclopedia claims that Shechem is the only location that meets all the requirements for Bethulia's location, further stating: "The identity of Bethulia with Shechem is thus beyond all question". Charles Cutler Torrey pointed out that the description of water being brought to the city by means of an aqueduct from a spring above the city on the south side is a trait that can only belong to Shechem.

The Catholic Encyclopedia

''The'' ''Catholic Encyclopedia: An International Work of Reference on the Constitution, Doctrine, Discipline, and History of the Catholic Church'', also referred to as the ''Old Catholic Encyclopedia'' and the ''Original Catholic Encyclopedi ...

writes: "The city was situated on a mountain overlooking the plain of Jezrael, or Esdrelon, and commanding narrow passes to the south (); at the foot of the mountain there was an important spring, and other springs were in the neighborhood (). Moreover, it lay within investing lines which ran through Dothain

Dothan (Hebrew: ) (also Dotan) was a location mentioned twice in the Hebrew Bible. It has been identified with Tel Dothan (), also known as Tel al-Hafireh, located adjacent to the Palestinian town of Bir al-Basha, and ten kilometers (driving dist ...

, or Dothan, now Tell Dothân, to Belthem, or Belma, no doubt the same as the Belamon of , and thence to Kyamon, or Chelmon, "which lies over against Esdrelon" (). These data point to a site on the heights west of Jenin

Jenin ( ; , ) is a city in the West Bank, Palestine, and is the capital of the Jenin Governorate. It is a hub for the surrounding towns. Jenin came under Israeli occupied territories, Israeli occupation in 1967, and was put under the administra ...

(Engannim), between the plains of Esdrelon and Dothan, where Haraiq el-Mallah, Khirbet Sheikh Shibel and el-Bârid lie close together. Such a site best fulfills all requirements for the location of Bethulia.

The Madaba Map

The Madaba Map, also known as the Madaba Mosaic Map, is part of a floor mosaic in the early Byzantine church of Saint George in Madaba, Jordan.