Judas Maccabeus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Judas Maccabaeus or Maccabeus ( ), also known as Judah Maccabee (), was a

Mindful of the superiority of Seleucid forces during the first two years of the revolt, Judah's strategy was to avoid any engagement with their regular army and resort to

Mindful of the superiority of Seleucid forces during the first two years of the revolt, Judah's strategy was to avoid any engagement with their regular army and resort to

Upon hearing the news that the Jewish communities in

Upon hearing the news that the Jewish communities in

When war against the external enemy ended, an internal struggle broke out between the party led by Judah and the Hellenist party. The influence of the Hellenizers all but collapsed in the wake of the Seleucid defeat. The Hellenizing

When war against the external enemy ended, an internal struggle broke out between the party led by Judah and the Hellenist party. The influence of the Hellenizers all but collapsed in the wake of the Seleucid defeat. The Hellenizing

There has been interest in Judah in every century. ''Giuda Macabeo, ossia la morte di Nicanore...'' (1839) is an Italian " azione sacra" based on which Vallicella composed an

There has been interest in Judah in every century. ''Giuda Macabeo, ossia la morte di Nicanore...'' (1839) is an Italian " azione sacra" based on which Vallicella composed an

In the

In the

The Hasmoneans on the web

Judas Maccabeus on the Web (pictures and directory)

Jewish Encyclopedia

"Under the Influence: Hellenism in Ancient Jewish Life"

Biblical Archaeology Society

Who Was Judah Maccabee?

by Dr. Henry Abramson *

Lions of Judea

', novel series by Amit Arad {{DEFAULTSORT:Maccabeus, Judas 160 BC deaths 2nd-century BCE high priests of Israel 2nd-century BC Hasmonean monarchs Military personnel killed in action People in the deuterocanonical books Year of birth unknown Maccabees 2nd-century BCE Jews Jewish priests Gilead 2nd-century BC rebels Military personnel from Jerusalem

Jew

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, religion, and community are highly inte ...

ish priest (''kohen

Kohen (, ; , ، Arabic كاهن , Kahen) is the Hebrew word for "priest", used in reference to the Aaronic Priest#Judaism, priesthood, also called Aaronites or Aaronides. They are traditionally believed, and halakha, halakhically required, to ...

'') and a son of the priest Mattathias

Mattathias ben Johanan (, ''Mattīṯyāhū haKōhēn ben Yōḥānān''; died 166–165 BCE) was a Kohen (Jewish priest) who helped spark the Maccabean Revolt against the Hellenistic Seleucid Empire. Mattathias's story is related in the deuter ...

. He led the Maccabean Revolt

The Maccabean Revolt () was a Jewish rebellion led by the Maccabees against the Seleucid Empire and against Hellenistic influence on Jewish life. The main phase of the revolt lasted from 167 to 160 BCE and ended with the Seleucids in control of ...

against the Seleucid Empire

The Seleucid Empire ( ) was a Greek state in West Asia during the Hellenistic period. It was founded in 312 BC by the Macedonian general Seleucus I Nicator, following the division of the Macedonian Empire founded by Alexander the Great ...

(167–160 BCE).

The Jewish holiday of Hanukkah

Hanukkah (, ; ''Ḥănukkā'' ) is a Jewish holidays, Jewish festival commemorating the recovery of Jerusalem and subsequent rededication of the Second Temple at the beginning of the Maccabean Revolt against the Seleucid Empire in the 2nd ce ...

("Dedication") commemorates the restoration of Jewish worship at the Second Temple

The Second Temple () was the Temple in Jerusalem that replaced Solomon's Temple, which was destroyed during the Siege of Jerusalem (587 BC), Babylonian siege of Jerusalem in 587 BCE. It was constructed around 516 BCE and later enhanced by Herod ...

in Jerusalem in 164 BCE after Judah Maccabee removed all of the statues depicting Greek gods and goddesses and purified it.

Life

Early life

Judah was the third son ofMattathias

Mattathias ben Johanan (, ''Mattīṯyāhū haKōhēn ben Yōḥānān''; died 166–165 BCE) was a Kohen (Jewish priest) who helped spark the Maccabean Revolt against the Hellenistic Seleucid Empire. Mattathias's story is related in the deuter ...

, the Hasmonean, a Jewish priest from the village of Modi'in

Modi'in-Maccabim-Re'ut ( ''Mōdīʿīn-Makkabbīm-Rēʿūt'') is a city located in central Israel, about southeast of Tel Aviv and west of Jerusalem, and is connected to those two cities via Route 443 (Israel), Highway 443. In the population ...

. In 167 BCE, Mattathias, together with his sons Judah, Eleazar

Eleazar (; ) or Elazar was a priest in the Hebrew Bible, the second High Priest, succeeding his father Aaron after he died. He was a nephew of Moses.

Biblical narrative

Eleazar played a number of roles during the course of the Exodus, from ...

, Simon, John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Second E ...

, and Jonathan, started a revolt against the Seleucid ruler Antiochus IV Epiphanes

Antiochus IV Epiphanes ( 215 BC–November/December 164 BC) was king of the Seleucid Empire from 175 BC until his death in 164 BC. Notable events during Antiochus' reign include his near-conquest of Ptolemaic Egypt, his persecution of the Jews of ...

, who since 169/8 BCE had issued decrees that forbade Jewish

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

religious practices. After Mattathias died in 166 BCE, Judah assumed leadership of the revolt per the deathbed disposition of his father. The First Book of Maccabees praises Judah's valor and military talent, suggesting that those qualities made Judah a natural choice for the new commander.

Origin of the name "The Hammer"

In the early days of the rebellion, Judah received the surname Maccabee. It is not known whether this name should be understood in Greek, Hebrew, or Aramaic. Several explanations have been put forward for this name. One suggestion is that the name derives from theAramaic

Aramaic (; ) is a Northwest Semitic language that originated in the ancient region of Syria and quickly spread to Mesopotamia, the southern Levant, Sinai, southeastern Anatolia, and Eastern Arabia, where it has been continually written a ...

''maqqaba'' ("makebet" in modern Hebrew

Hebrew (; ''ʿÎbrit'') is a Northwest Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic language within the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family. A regional dialect of the Canaanite languages, it was natively spoken by the Israelites and ...

), "hammer" or "sledgehammer" (cf.

The abbreviation cf. (short for either Latin or , both meaning 'compare') is generally used in writing to refer the reader to other material to make a comparison with the topic being discussed. However some sources offer differing or even contr ...

the cognomen of Charles Martel

Charles Martel (; – 22 October 741), ''Martel'' being a sobriquet in Old French for "The Hammer", was a Franks, Frankish political and military leader who, as Duke and Prince of the Franks and Mayor of the Palace, was the de facto ruler of ...

, the 8th century Frankish leader), in recognition of his ferocity in battle.

According to Jewish folklore, the name ''Maccabee'' is an acronym

An acronym is a type of abbreviation consisting of a phrase whose only pronounced elements are the initial letters or initial sounds of words inside that phrase. Acronyms are often spelled with the initial Letter (alphabet), letter of each wor ...

of the verse ''Mi kamokha ba'elim Adonai ( YHWH)'', "Who is like you, O God, among the gods that are worshiped?", the Maccabean battle-cry to motivate troops ( Exodus 15:11) as well as a part of daily Jewish prayers (see Mi Chamocha). Some scholars maintain that the name is a shortened form of the Hebrew ''maqqab-Yahu'' (from ''naqab'', "to mark, to designate"), meaning "the one designated by God." Although contextualized as a modern-day "surname" (Jews didn't start having surnames until the Middle Ages) exclusive to Judah, Maccabee came to signify all the Hasmoneans who fought during the Maccabean revolt.

Early victories

Mindful of the superiority of Seleucid forces during the first two years of the revolt, Judah's strategy was to avoid any engagement with their regular army and resort to

Mindful of the superiority of Seleucid forces during the first two years of the revolt, Judah's strategy was to avoid any engagement with their regular army and resort to guerrilla warfare

Guerrilla warfare is a form of unconventional warfare in which small groups of irregular military, such as rebels, partisans, paramilitary personnel or armed civilians, which may include recruited children, use ambushes, sabotage, terrori ...

to give them a feeling of insecurity. The strategy enabled Judah to win a string of victories. At the battle of Nahal el-Haramiah (wadi haramia), he defeated a small Seleucid force under the command of Apollonius, governor of Samaria

Samaria (), the Hellenized form of the Hebrew name Shomron (), is used as a historical and Hebrew Bible, biblical name for the central region of the Land of Israel. It is bordered by Judea to the south and Galilee to the north. The region is ...

, who was killed. Judah took possession of Apollonius's sword and used it until his death as a symbol of vengeance. After Nahal el-Haramiah, recruits flocked to the Jewish cause.

Shortly after that, Judah routed a larger Seleucid army under the command of Seron near Beth-Horon, largely thanks to a good choice of battlefield. Then, in the Battle of Emmaus, Judah proceeded to defeat the Seleucid forces led by generals Nicanor and Gorgias

Gorgias ( ; ; – ) was an ancient Greek sophist, pre-Socratic philosopher, and rhetorician who was a native of Leontinoi in Sicily. Several doxographers report that he was a pupil of Empedocles, although he would only have been a few years ...

. This force was dispatched by Lysias

Lysias (; ; c. 445 – c. 380 BC) was a Logographer (legal), logographer (speech writer) in ancient Greece. He was one of the ten Attic orators included in the "Alexandrian Canon" compiled by Aristophanes of Byzantium and Aristarchus of Samothrac ...

, whom Antiochus left as viceroy

A viceroy () is an official who reigns over a polity in the name of and as the representative of the monarch of the territory.

The term derives from the Latin prefix ''vice-'', meaning "in the place of" and the Anglo-Norman ''roy'' (Old Frenc ...

after departing on a campaign against the Parthians. By a forced night march, Judah succeeded in eluding Gorgias, who had intended to attack and destroy the Jewish forces in their camp with his cavalry. While Gorgias was searching for him in the mountains, Judah surprisedly attacked the Seleucid camp and defeated the Seleucids at the Battle of Emmaus. The Seleucid commander had no alternative but to withdraw to the coast.

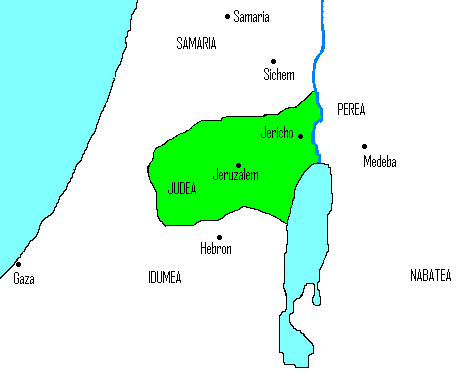

The defeat at Emmaus convinced Lysias that he must prepare for a serious and prolonged war. He accordingly assembled a new and larger army and marched with it on Judea

Judea or Judaea (; ; , ; ) is a mountainous region of the Levant. Traditionally dominated by the city of Jerusalem, it is now part of Palestine and Israel. The name's usage is historic, having been used in antiquity and still into the pres ...

from the south via Idumea. After several years of conflict, Judah drove out his foes from Jerusalem, except for the garrison in the citadel of Acra. He purified the defiled Temple of Jerusalem and, on the 25th of Kislev

Kislev or Chislev (Hebrew language, Hebrew: , Hebrew language#Modern Hebrew, Standard ''Kīslev'' Tiberian vocalization, Tiberian ''Kīslēw''), is the third month of the civil year and the ninth month of the ecclesiastical year on the Hebrew c ...

(December 14, 164 BCE), restored the service in the Temple. The reconsecration of the Temple became a permanent Jewish holiday, Hanukkah

Hanukkah (, ; ''Ḥănukkā'' ) is a Jewish holidays, Jewish festival commemorating the recovery of Jerusalem and subsequent rededication of the Second Temple at the beginning of the Maccabean Revolt against the Seleucid Empire in the 2nd ce ...

, which continued even after the Temple was destroyed in 70 CE. Hanukkah is still celebrated annually. The liberation of Jerusalem was the first step on the road to ultimate independence.

After Jerusalem

Gilead

Gilead or Gilad (, ; ''Gilʿāḏ'', , ''Jalʻād'') is the ancient, historic, biblical name of the mountainous northern part of the region of Transjordan.''Easton's Bible Dictionary'Galeed''/ref> The region is bounded in the west by the J ...

, Transjordan, and Galilee

Galilee (; ; ; ) is a region located in northern Israel and southern Lebanon consisting of two parts: the Upper Galilee (, ; , ) and the Lower Galilee (, ; , ).

''Galilee'' encompasses the area north of the Mount Carmel-Mount Gilboa ridge and ...

were under attack by neighboring Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

cities, Judah immediately went to their aid. Judah sent his brother, Simeon, to Galilee at the head of 3,000 men; Simeon was successful, achieving numerous victories. He transplanted a substantial portion of the Jewish settlements, including women and children, to Judea. Judah led the campaign in Transjordan, taking his brother Jonathan with him. After fierce fighting, he defeated the Transjordanian tribes and rescued the Jews concentrated in fortified towns in Gilead. The Jewish population of the areas taken by the Maccabees was evacuated to Judea. After the fighting in Transjordan, Judah turned against the Edomites

Edom (; Edomite: ; , lit.: "red"; Akkadian: , ; Ancient Egyptian: ) was an ancient kingdom that stretched across areas in the south of present-day Jordan and Israel. Edom and the Edomites appear in several written sources relating to the ...

in the south, captured and destroyed Hebron

Hebron (; , or ; , ) is a Palestinian city in the southern West Bank, south of Jerusalem. Hebron is capital of the Hebron Governorate, the largest Governorates of Palestine, governorate in the West Bank. With a population of 201,063 in ...

and Maresha

Maresha was an Iron Age city mentioned in the Hebrew Bible, whose remains have been excavated at Tell Sandahanna (Arabic name), an Tell (archaeology), archaeological mound or 'tell' renamed after its identification to Tel Maresha (). The ancient ...

. He then marched on the coast of the Mediterranean, destroyed the altars and statues of the pagan gods in Ashdod

Ashdod (, ; , , or ; Philistine language, Philistine: , romanized: *''ʾašdūd'') is the List of Israeli cities, sixth-largest city in Israel. Located in the country's Southern District (Israel), Southern District, it lies on the Mediterranean ...

, and returned to Judea with many spoils.

Judah then laid siege to the Seleucid garrison at the Acra, the Seleucid citadel of Jerusalem. The besieged, who included not only Syrian-Greek troops but also Hellenistic

In classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Greek history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the death of Cleopatra VII in 30 BC, which was followed by the ascendancy of the R ...

Jews, appealed for help to Lysias, who effectively became the regent of the young king Antiochus V Eupator after the death of Antiochus Epiphanes at the end of 164 BCE during the Parthia

Parthia ( ''Parθava''; ''Parθaw''; ''Pahlaw'') is a historical region located in northeastern Greater Iran. It was conquered and subjugated by the empire of the Medes during the 7th century BC, was incorporated into the subsequent Achaemeni ...

n campaign. Lysias and Eupator set out for a new campaign in Judea. Lysias skirted Judea as he had done in his first campaign, entering it from the south and besieging Beth-Zur. Judah raised the siege of the Acra and went to meet Lysias. In the Battle of Beth-zechariah, south of Bethlehem

Bethlehem is a city in the West Bank, Palestine, located about south of Jerusalem, and the capital of the Bethlehem Governorate. It had a population of people, as of . The city's economy is strongly linked to Tourism in the State of Palesti ...

, the Seleucids achieved their first major victory over the Maccabees, and Judah was forced to withdraw to Jerusalem. Beth-Zur was compelled to surrender, and Lysias reached Jerusalem and laid siege on the city. The defenders found themselves in a precarious situation because their provisions were exhausted; it was a sabbatical year during which the fields were left uncultivated. However, just as capitulation seemed imminent, Lysias and Eupator had to withdraw when Antiochus Epiphanes's commander-in-chief Philip, whom the late ruler appointed regent before his death, rebelled against Lysias and was about to enter Antioch

Antioch on the Orontes (; , ) "Antioch on Daphne"; or "Antioch the Great"; ; ; ; ; ; ; . was a Hellenistic Greek city founded by Seleucus I Nicator in 300 BC. One of the most important Greek cities of the Hellenistic period, it served as ...

and seize power. Lysias proposed a peaceful settlement, which was concluded at the end of 163 BCE. The peace terms were based on the restoration of religious freedom, the permission for the Jews to live per their own laws, and the official return of the Temple to the Jews. Lysias defeated Philip, only to be overthrown by Demetrius

Demetrius is the Latinization of names, Latinized form of the Ancient Greek male name, male Greek given names, given name ''Dēmḗtrios'' (), meaning "devoted to goddess Demeter".

Alternate forms include Demetrios, Dimitrios, Dimitris, Dmytro, ...

, son of the late Seleucus IV Philopator

Seleucus IV Philopator ( Greek: Σέλευκος Φιλοπάτωρ, ''Séleukos philopátо̄r'', meaning "Seleucus the father-loving"; 218 – 3 September 175 BC), ruler of the Hellenistic Seleucid Empire, reigned from 187 BC to 175 BC over a ...

, who returned from years as a hostage in Rome. Demetrius appointed Alcimus (Jakim), a Hellenistic Jew, as high priest, a choice the Hasidim (Pietists) might have accepted since he was of priestly descent.

Internal conflict

When war against the external enemy ended, an internal struggle broke out between the party led by Judah and the Hellenist party. The influence of the Hellenizers all but collapsed in the wake of the Seleucid defeat. The Hellenizing

When war against the external enemy ended, an internal struggle broke out between the party led by Judah and the Hellenist party. The influence of the Hellenizers all but collapsed in the wake of the Seleucid defeat. The Hellenizing High Priest

The term "high priest" usually refers either to an individual who holds the office of ruler-priest, or to one who is the head of a religious organisation.

Ancient Egypt

In ancient Egypt, a high priest was the chief priest of any of the many god ...

Menelaus

In Greek mythology, Menelaus (; ) was a Greek king of Mycenaean (pre- Dorian) Sparta. According to the ''Iliad'', the Trojan war began as a result of Menelaus's wife, Helen, fleeing to Troy with the Trojan prince Paris. Menelaus was a central ...

was removed from office and executed. His successor was another Hellenizer Alcimus. When Alcimus executed sixty priests who were opposed to him, he found himself in open conflict with the Maccabees. Alcimus fled from Jerusalem and went to the Seleucid king, asking for help.

Meanwhile, Demetrius I Soter

Demetrius I Soter (, ''Dēmḗtrios ho Sōtḗr,'' "Demetrius the Saviour"; 185 – June 150 BC) reigned as king of the Hellenistic Seleucid Empire from November 162 to June 150 BC. Demetrius grew up in Rome as a hostage, but returned to Greek S ...

, son of Seleucus IV Philopator

Seleucus IV Philopator ( Greek: Σέλευκος Φιλοπάτωρ, ''Séleukos philopátо̄r'', meaning "Seleucus the father-loving"; 218 – 3 September 175 BC), ruler of the Hellenistic Seleucid Empire, reigned from 187 BC to 175 BC over a ...

and nephew of the late Antiochus IV Epiphanes, fled from Rome in defiance of the Roman Senate

The Roman Senate () was the highest and constituting assembly of ancient Rome and its aristocracy. With different powers throughout its existence it lasted from the first days of the city of Rome (traditionally founded in 753 BC) as the Sena ...

and arrived in Syria. Declaring himself the rightful king, he captured and killed Lysias and Antiochus Eupator, taking the throne. It was thus Demetrius to whom the delegation, led by Alcimus, complained of the persecution of the Hellenist party in Judea. Demetrius granted Alcimus's request to be appointed High Priest under the protection of the king's army and sent to Judea an army led by Bacchides. The weaker Jewish army could not oppose the enemy and withdrew from Jerusalem, so Judah returned to wage guerrilla warfare. Soon after, the Seleucid Army needed to return to Antioch

Antioch on the Orontes (; , ) "Antioch on Daphne"; or "Antioch the Great"; ; ; ; ; ; ; . was a Hellenistic Greek city founded by Seleucus I Nicator in 300 BC. One of the most important Greek cities of the Hellenistic period, it served as ...

because of the turbulent political situation. Judah's forces returned to Jerusalem, and the Seleucids dispatched another army led by Nicanor. In a battle near Adasa, on the 13th Adar

Adar (Hebrew: , ; from Akkadian ''adaru'') is the sixth month of the civil year and the twelfth month of the religious year on the Hebrew calendar, roughly corresponding to the month of March in the Gregorian calendar. It is a month of 29 days. ...

161 BCE, the Seleucid army was destroyed, and Nicanor was killed. The annual "Day of Nicanor" was instituted to commemorate this victory.

Agreement with Rome and death

The Roman–Jewish Treaty was an agreement made between Judah Maccabee and theRoman Republic

The Roman Republic ( ) was the era of Ancient Rome, classical Roman civilisation beginning with Overthrow of the Roman monarchy, the overthrow of the Roman Kingdom (traditionally dated to 509 BC) and ending in 27 BC with the establis ...

in 161 BCE according to and Josephus

Flavius Josephus (; , ; ), born Yosef ben Mattityahu (), was a Roman–Jewish historian and military leader. Best known for writing '' The Jewish War'', he was born in Jerusalem—then part of the Roman province of Judea—to a father of pr ...

. It was the first recorded contract between the Jewish

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

people and the Romans.

The agreement with Rome failed to affect Demetrius' policy. On receiving the news of Nicanor's defeat, he dispatched a new army, again commanded by Bacchides. This time, the Seleucid forces of 20,000 men were numerically so superior that most of Judah's men left the battlefield and advised their leader to do likewise and await a more favorable opportunity. However, Judah decided to stand his ground.

In the Battle of Elasa, Judah and those who remained faithful to him were killed. His body was taken by his brothers from the battlefield and buried in the family sepulcher at Modiin. The death of Judah Maccabee (d. 160 BCE) stirred the Jews to renewed resistance. After several additional years of war under the leadership of two of Mattathias' other sons (Jonathan and Simon), the Jews finally achieved independence and the liberty to worship freely.

In the arts

Pre-19th century

As a warrior hero and national liberator, Judah Maccabee has inspired many writers, and several artists and composers. In the ''Divine Comedy

The ''Divine Comedy'' (, ) is an Italian narrative poetry, narrative poem by Dante Alighieri, begun and completed around 1321, shortly before the author's death. It is widely considered the pre-eminent work in Italian literature and one of ...

'', Dante

Dante Alighieri (; most likely baptized Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri; – September 14, 1321), widely known mononymously as Dante, was an Italian Italian poetry, poet, writer, and philosopher. His ''Divine Comedy'', originally called ...

sees his spirit in the Heaven of Mars with the other "heroes of the true faith". In Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 23 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's natio ...

's ''Love's Labour's Lost

''Love's Labour's Lost'' is one of William Shakespeare's early comedies, believed to have been written in the mid-1590s for a performance at the Inns of Court before Queen Elizabeth I. It follows the King of Navarre and his three companions as ...

'', he is enacted along with the other Nine Worthies

The Nine Worthies are nine historical, scriptural, and legendary men of distinction who personify the ideals of chivalry established in the Middle Ages, whose lives were deemed a valuable study for aspirants to chivalric status. All were commonly ...

, but heckled for sharing a name with Judas Iscariot

Judas Iscariot (; ; died AD) was, according to Christianity's four canonical gospels, one of the original Twelve Apostles of Jesus Christ. Judas betrayed Jesus to the Sanhedrin in the Garden of Gethsemane, in exchange for thirty pieces of sil ...

. Most significant works dedicated solely to him date from the 17th century onwards. William Houghton's ''Judas Maccabaeus'', performed in about 1601 but now lost, is thought to have been the first drama on the theme; however, ''Judas Macabeo'', an early ''comedia'' by crucial Spanish playwright Pedro Calderón de la Barca

Pedro Calderón de la Barca y Barreda González de Henao Ruiz de Blasco y Riaño (17 January 160025 May 1681) (, ; ) was a Spanish dramatist, poet, and writer. He is known as one of the most distinguished Spanish Baroque literature, poets and ...

, is extant. Fernando Rodríguez-Gallego details its history in his critical edition: the play was performed in the 1620s in different versions and finally published as part of an anthology by Vera Tassis in 1637. Following on its heels is ''El Macabeo'' (Naples

Naples ( ; ; ) is the Regions of Italy, regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 908,082 within the city's administrative limits as of 2025, while its Metropolitan City of N ...

, 1638), a Castilian epic by the Portuguese Marrano

''Marranos'' is a term for Spanish and Portuguese Jews, as well as Navarrese jews, who converted to Christianity, either voluntarily or by Spanish or Portuguese royal coercion, during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, but who continued t ...

Miguel de Silveyra. Two other 17th-century works are ''La chevalerie de Judas Macabé'', by French poet Pierre Du Ries, and the anonymous Neo-Latin

Neo-LatinSidwell, Keith ''Classical Latin-Medieval Latin-Neo Latin'' in ; others, throughout. (also known as New Latin and Modern Latin) is the style of written Latin used in original literary, scholarly, and scientific works, first in Italy d ...

work ''Judas Machabaeus'' (Rome, 1695). Handel

George Frideric (or Frederick) Handel ( ; baptised , ; 23 February 1685 – 14 April 1759) was a German-British Baroque composer well-known for his operas, oratorios, anthems, concerti grossi, and organ concerti.

Born in Halle, Germany, H ...

wrote his ''Judas Maccabaeus'' oratorio (1746) on the subject.

19th century

There has been interest in Judah in every century. ''Giuda Macabeo, ossia la morte di Nicanore...'' (1839) is an Italian " azione sacra" based on which Vallicella composed an

There has been interest in Judah in every century. ''Giuda Macabeo, ossia la morte di Nicanore...'' (1839) is an Italian " azione sacra" based on which Vallicella composed an oratorio

An oratorio () is a musical composition with dramatic or narrative text for choir, soloists and orchestra or other ensemble.

Similar to opera, an oratorio includes the use of a choir, soloists, an instrumental ensemble, various distinguisha ...

. One of the best-known literary works on the theme is ''Judas Maccabaeus'' (1872), a five-act verse tragedy by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (February 27, 1807 – March 24, 1882) was an American poet and educator. His original works include the poems " Paul Revere's Ride", '' The Song of Hiawatha'', and '' Evangeline''. He was the first American to comp ...

. A Hebrew version of Longfellow's play was published in 1900. Two later 19th-century interpretations of the story are ''Judas Makkabaeus'', a novella by the German writer Josef Eduard Konrad Bischoff, which appeared in ''Der Gefangene von Kuestrin'' (1885), and ''The Hammer'' (1890), a book by Alfred J. Church and Richmond Seeley.

20th century

Several 20th-century Jewish authors have also written works devoted to Judah Maccabee and the Maccabean Revolt. Jacob Benjamin Katznelson (1855–1930) wrote the poem, "Alilot Gibbor ha-Yehudim Yehudah ha-Makkabi le-Veit ha-Hashmona'im" (1922); theYiddish

Yiddish, historically Judeo-German, is a West Germanic language historically spoken by Ashkenazi Jews. It originated in 9th-century Central Europe, and provided the nascent Ashkenazi community with a vernacular based on High German fused with ...

writer Moses Schulstein wrote the dramatic poem, "Yehudah ha-Makkabi" (in ''A Layter tsu der Zun'', 1954); Jacob Fichman's "Yehudah ha-Makkabi" is one of the heroic tales included in ''Sippurim le-Mofet'' (1954). Amit Arad's historical novel "Lions of Judea – The miraculous story of the Maccabees" (2014). Many children's plays have also been written on the theme by various Jewish authors.

In addition, the American writer Howard Fast penned the historical novel

Historical fiction is a literary genre in which a fictional plot takes place in the setting of particular real historical events. Although the term is commonly used as a synonym for historical fiction literature, it can also be applied to oth ...

, '' My Glorious Brothers'', which was published in 1948, during the 1947–1949 Palestine war.

During World War II the Swiss-German writer Karl Boxler published his novel ''Judas Makkabaeus; ein Kleinvolk kaempft um Glaube und Heimat'' (1943), the subtitle of which suggests that Swiss democrats then drew a parallel between their own national hero, William Tell

William Tell (, ; ; ; ) is a legendary folk hero of Switzerland. He is known for shooting an apple off his son's head.

According to the legend, Tell was an expert mountain climber and marksman with a crossbow who assassinated Albrecht Gessler, ...

, and the leader of the Maccabean revolt against foreign tyranny.

The modern play ''Playing Dreidel with Judah Maccabee'' by Edward Einhorn is about a contemporary boy who meets the historical figure.

Visual arts

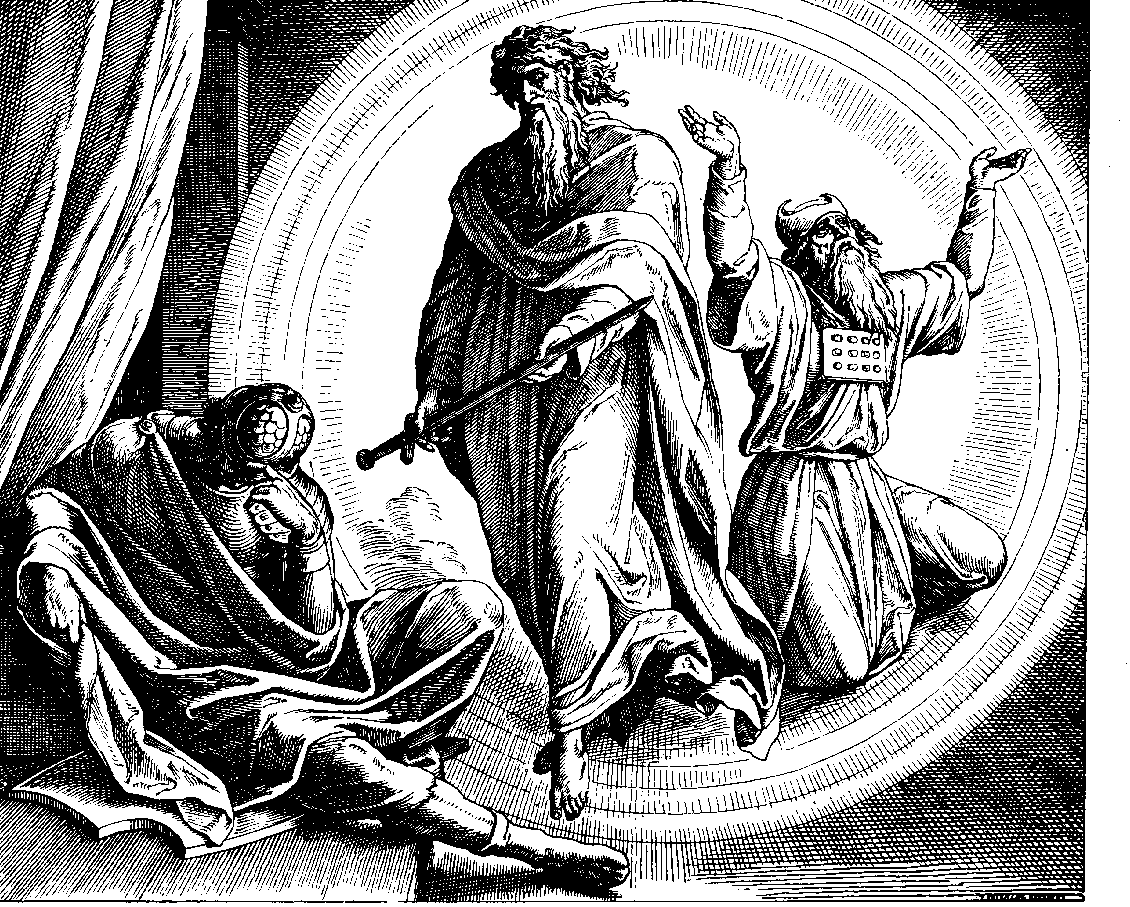

In the

In the medieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of World history (field), global history. It began with the fall of the West ...

Christian

A Christian () is a person who follows or adheres to Christianity, a Monotheism, monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus Christ. Christians form the largest religious community in the wo ...

art, Judah Maccabee was regarded as one of the heroes of the Old Testament

The Old Testament (OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible, or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew and occasionally Aramaic writings by the Isr ...

. He figures in a tenth-century illustrated manuscript ''Libri Maccabaeorum''. The late medieval French artist Jean Fouquet painted an illustration of Judah triumphing over his enemies for his famous manuscript of Josephus. Rubens

Sir Peter Paul Rubens ( ; ; 28 June 1577 – 30 May 1640) was a Flemish artist and diplomat. He is considered the most influential artist of the Flemish Baroque tradition. Rubens' highly charged compositions reference erudite aspects of clas ...

painted Judah Maccabee praying for the dead; the painting illustrates an episode from 2 Maccabees 12:39–48 in which Judah's troops find stolen idolatrous charms on the corpses of Jewish warriors slain on the battlefield. He therefore offers prayers and an expiatory sacrifice for these warriors who have died in a state of sin. During the Counter-Reformation

The Counter-Reformation (), also sometimes called the Catholic Revival, was the period of Catholic resurgence that was initiated in response to, and as an alternative to or from similar insights as, the Protestant Reformations at the time. It w ...

the passage was used by Catholics

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

against Protestants

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

in order to justify the doctrine of purgatory

In Christianity, Purgatory (, borrowed into English language, English via Anglo-Norman language, Anglo-Norman and Old French) is a passing Intermediate state (Christianity), intermediate state after physical death for purifying or purging a soul ...

. Accordingly, Rubens painted the scene for the Chapel of the Dead in Tournai

Tournai ( , ; ; ; , sometimes Anglicisation (linguistics), anglicised in older sources as "Tournay") is a city and Municipalities in Belgium, municipality of Wallonia located in the Hainaut Province, Province of Hainaut, Belgium. It lies by ...

cathedral. In the 19th century, Paul Gustave Doré executed an engraving of Judah Maccabee victoriously pursuing the shattered troops of the Syrian enemy.

Music

In music, almost all the compositions inspired by the Hasmonean rebellion revolve around Judah. In 1746, the composerGeorge Frideric Handel

George Frideric (or Frederick) Handel ( ; baptised , ; 23 February 1685 – 14 April 1759) was a German-British Baroque composer well-known for his operas, oratorios, anthems, concerti grossi, and organ concerti.

Born in Halle, Germany, H ...

composed his oratorio

An oratorio () is a musical composition with dramatic or narrative text for choir, soloists and orchestra or other ensemble.

Similar to opera, an oratorio includes the use of a choir, soloists, an instrumental ensemble, various distinguisha ...

''Judas Maccabeus

Judas Maccabaeus or Maccabeus ( ), also known as Judah Maccabee (), was a Jewish priest (''kohen'') and a son of the priest Mattathias. He led the Maccabean Revolt against the Seleucid Empire (167–160 BCE).

The Jewish holiday of Hanukkah ("Ded ...

,'' putting the biblical story in the context of the Jacobite rising of 1745

The Jacobite rising of 1745 was an attempt by Charles Edward Stuart to regain the Monarchy of Great Britain, British throne for his father, James Francis Edward Stuart. It took place during the War of the Austrian Succession, when the bulk of t ...

. This work, with libretto by Thomas Morell, had been written for the celebrations following the Duke of Cumberland

Duke of Cumberland is a peerage title that was conferred upon junior members of the British royal family, named after the historic county of Cumberland.

History

The Earldom of Cumberland, created in 1525, became extinct in 1643. The dukedom w ...

's victory over the Scottish Jacobite rebels at the Battle of Culloden

The Battle of Culloden took place on 16 April 1746, near Inverness in the Scottish Highlands. A Jacobite army under Charles Edward Stuart was decisively defeated by a British government force commanded by the Duke of Cumberland, thereby endi ...

in 1746. The oratorio's most famous chorus is "See, the conqu'ring hero comes". The tune of this chorus was later adopted as a Christian

A Christian () is a person who follows or adheres to Christianity, a Monotheism, monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus Christ. Christians form the largest religious community in the wo ...

Easter

Easter, also called Pascha ( Aramaic: פַּסְחָא , ''paskha''; Greek: πάσχα, ''páskha'') or Resurrection Sunday, is a Christian festival and cultural holiday commemorating the resurrection of Jesus from the dead, described in t ...

hymn tune ''Thine Be The Glory, Risen Conquering Son''. A Hebrew translation of Handel's ''Judas Maccabee'' was prepared for the 1932 Maccabiah Games

The Maccabiah Games (, or משחקי המכביה העולמית; sometimes referred to as the "Jewish Olympics") is an international multi-sport event with summer and winter sports competitions featuring Jews and Israelis regardless of religion ...

and is now popular in Israel

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan to the east, Egypt to the south-west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Isr ...

with the motif of "conqu'ring hero" becoming a Hanukkah

Hanukkah (, ; ''Ḥănukkā'' ) is a Jewish holidays, Jewish festival commemorating the recovery of Jerusalem and subsequent rededication of the Second Temple at the beginning of the Maccabean Revolt against the Seleucid Empire in the 2nd ce ...

song. Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven (baptised 17 December 177026 March 1827) was a German composer and pianist. He is one of the most revered figures in the history of Western music; his works rank among the most performed of the classical music repertoire ...

composed a set of theme and variations 12 Variations on ''Tom Lehrer

Thomas Andrew Lehrer (; born April 9, 1928) is an American musician, singer-songwriter, satirist, and mathematician, who later taught mathematics and musical theater. He recorded pithy and humorous, often Music and politics, political songs that ...

refers to Judas Maccabeus in his song "Hanukkah in Santa Monica".

Mirah refers to Judah Maccabee in her song "Jerusalem".

In " The Goldbergs Mixtape", a parody song is named "Judah Macabee".

See also

* Jewish leadership * List of Hasmonean and Herodian rulers *Nine Worthies

The Nine Worthies are nine historical, scriptural, and legendary men of distinction who personify the ideals of chivalry established in the Middle Ages, whose lives were deemed a valuable study for aspirants to chivalric status. All were commonly ...

Notes

References

Further reading

* Schalit, Abraham (1997). "Judah Maccabee". ''Encyclopaedia Judaica

The ''Encyclopaedia Judaica'' is a multi-volume English-language encyclopedia of the Jewish people, Judaism, and Israel. It covers diverse areas of the Jewish world and civilization, including Jewish history of all eras, culture, Jewish holida ...

'' (CD-ROM Edition Version 1.0). Ed. Cecil Roth

Cecil Roth (5 March 1899 – 21 June 1970) was an English historian.

He was editor-in-chief of the ''Encyclopaedia Judaica''.

Life

Roth was born in Dalston, London, on 5 March 1899. His parents were Etty and Joseph Roth, and Cecil was the younge ...

. Keter Publishing House.

* Schäfer, Peter (2003). ''The History of the Jews in the Greco-Roman World''. Routledge.

External links

The Hasmoneans on the web

Judas Maccabeus on the Web (pictures and directory)

Jewish Encyclopedia

"Under the Influence: Hellenism in Ancient Jewish Life"

Biblical Archaeology Society

Who Was Judah Maccabee?

by Dr. Henry Abramson *

Lions of Judea

', novel series by Amit Arad {{DEFAULTSORT:Maccabeus, Judas 160 BC deaths 2nd-century BCE high priests of Israel 2nd-century BC Hasmonean monarchs Military personnel killed in action People in the deuterocanonical books Year of birth unknown Maccabees 2nd-century BCE Jews Jewish priests Gilead 2nd-century BC rebels Military personnel from Jerusalem