John Redmond (educator) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

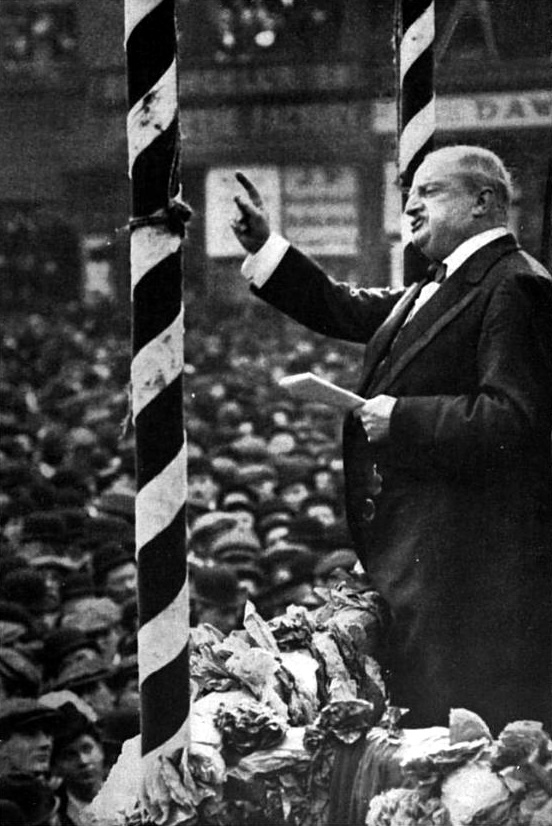

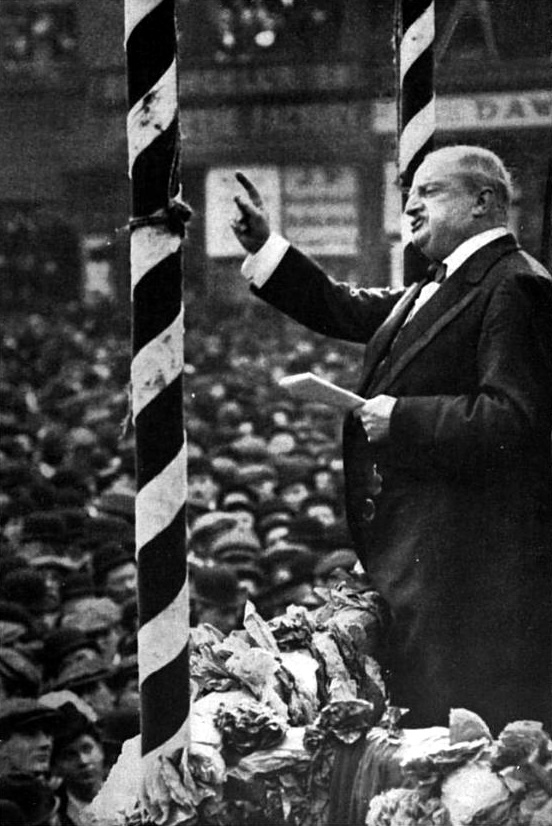

John Edward Redmond (1 September 1856 – 6 March 1918) was an

Irish nationalist

Irish nationalism is a nationalist political movement which, in its broadest sense, asserts that the people of Ireland should govern Ireland as a sovereign state. Since the mid-19th century, Irish nationalism has largely taken the form of cult ...

politician, barrister

A barrister is a type of lawyer in common law jurisdiction (area), jurisdictions. Barristers mostly specialise in courtroom advocacy and litigation. Their tasks include arguing cases in courts and tribunals, drafting legal pleadings, jurisprud ...

, and MP in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom

The House of Commons is the lower house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the upper house, the House of Lords, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England. The House of Commons is an elected body consisting of 650 memb ...

. He was best known as leader of the moderate Irish Parliamentary Party

The Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP; commonly called the Irish Party or the Home Rule Party) was formed in 1874 by Isaac Butt, the leader of the Nationalist Party, replacing the Home Rule League, as official parliamentary party for Irish nati ...

(IPP) from 1900 until his death in 1918. He was also the leader of the paramilitary organisation the Irish National Volunteers

The National Volunteers were the majority faction of the Irish Volunteers that sided with Irish Parliamentary Party leader John Redmond after the movement split over the question of the Volunteers' Ireland and World War I, role in World War I.

O ...

(INV).

He was born to an old prominent Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

family in rural Ireland; several relatives were politicians. He took over control of the minority IPP faction loyal to Charles Stewart Parnell

Charles Stewart Parnell (27 June 1846 – 6 October 1891) was an Irish nationalist politician who served as a Member of Parliament (United Kingdom), Member of Parliament (MP) in the United Kingdom from 1875 to 1891, Leader of the Home Rule Leag ...

when that leader died in 1891. Redmond was a conciliatory politician who achieved the two main objectives of his political life: party unity and, in September 1914, the passing of the Government of Ireland Act 1914

The Government of Ireland Act 1914 ( 4 & 5 Geo. 5. c. 90), also known as the Home Rule Act, and before enactment as the Third Home Rule Bill, was an Act passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom intended to provide home rule (self-gover ...

. The Act granted limited self-government to Ireland, within the United Kingdom. However, implementation of Home Rule was suspended on the outbreak of the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. Redmond called on the National Volunteers to join Irish regiments

The Irish military diaspora refers to the many people of either Irish birth or extraction (see Irish diaspora) who have served in overseas military forces, regardless of rank, duration of service, or success.

Many overseas military units were p ...

of the New British Army and support the British and Allied war effort to restore the "freedom of small nations" on the European continent, thereby to also ensure the implementation of Home Rule after a war that was expected to be of short duration. However, after the Easter Rising

The Easter Rising (), also known as the Easter Rebellion, was an armed insurrection in Ireland during Easter Week in April 1916. The Rising was launched by Irish republicans against British rule in Ireland with the aim of establishing an ind ...

of 1916, Irish public opinion shifted in favour of militant republicanism and full Irish independence, so that his party lost its dominance in Irish politics.

Family influences and background

John Edward Redmond (the younger) was born at Ballytrent House, Kilrane,County Wexford

County Wexford () is a Counties of Ireland, county in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster and is part of the Southern Region, Ireland, Southern Region. Named after the town of Wexford, it was ba ...

, his grandfather's old family mansion. He was the eldest son of William Archer Redmond, MP by Mary, daughter of General Hoey, the brother of Francis Hoey, heir of the Hoey seat, Dunganstown Castle, County Wicklow

County Wicklow ( ; ) is a Counties of Ireland, county in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. The last of the traditional 32 counties, having been formed as late as 1606 in Ireland, 1606, it is part of the Eastern and Midland Region and the Provinces ...

.

For over seven hundred years the Redmonds had been a prominent Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

gentry family in County Wexford and Wexford

Wexford ( ; archaic Yola dialect, Yola: ''Weiseforthe'') is the county town of County Wexford, Republic of Ireland, Ireland. Wexford lies on the south side of Wexford Harbour, the estuary of the River Slaney near the southeastern corner of the ...

town. They were one of the oldest Hiberno-Norman

Norman Irish or Hiberno-Normans (; ) is a modern term for the descendants of Norman settlers who arrived during the Anglo-Norman invasion of Ireland in the 12th century. Most came from England and Wales. They are distinguished from the native ...

families, and had for a long time been known as the Redmonds of 'The Hall', which is now known as Loftus Hall

Loftus Hall is a large country house on the Hook peninsula, County Wexford, Ireland. Built on the site of the original Redmond Hall, it is said to have been haunted by the devil and the ghost of a woman.

Loftus Hall has a long history of ow ...

. His more immediate family were a remarkable political dynasty themselves. Redmond's grand uncle, John Edward Redmond, was a prominent banker and businessman before entering Parliament as a member for Wexford constituency in 1859; his statue stands in Redmond Square, Wexford town. After his death in 1866, his nephew, William Archer Redmond, this John Redmond's father, was elected to the seat and soon emerged as a prominent supporter of Isaac Butt

Isaac Butt (6 September 1813 – 5 May 1879) was an Irish barrister, editor, politician, Member of Parliament in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, economist and the founder and first leader of a number of Irish nationalist par ...

's new policy for home rule. John Redmond was the brother of Willie Redmond

William Hoey Kearney Redmond (13 April 1861 – 7 June 1917) was an Irish Irish nationalism, nationalist politician who served as a Member of Parliament (United Kingdom), Member of Parliament (MP). He was also a lawyer and soldier Denman, Teren ...

, MP for Wexford and East Clare

East Clare was a UK Parliament constituency in Ireland, returning one Member of Parliament (MP) from 1885 to 1922.

Before the 1885 United Kingdom general election the area was part of the Clare constituency. From 1922, shortly before the es ...

, and the father of William Redmond a TD for Waterford

Waterford ( ) is a City status in Ireland, city in County Waterford in the South-East Region, Ireland, south-east of Ireland. It is located within the Provinces of Ireland, province of Munster. The city is situated at the head of Waterford H ...

, whose wife was Bridget Redmond, later also a TD for Waterford.

Redmond's family heritage was more complex than that of most of his nationalist political colleagues. His mother came from a Protestant and unionist family; although she had converted to Catholicism on marriage, she never converted to nationalism. His uncle General John Patrick Redmond, who had inherited the family estate, was created CB for his role during the Indian mutiny; he disapproved of his nephew's involvement in agrarian agitation of the 1880s. John Redmond boasted of his family involvement in the 1798 Wexford Rebellion

The Wexford Rebellion refers to the events of the Irish Rebellion of 1798 in County Wexford. From 27 May until 21 June 1798, Society of United Irishmen rebels revolted against British rule in the county, engaging in multiple confrontations wit ...

; a "Miss Redmond" had ridden in support of the rebels, a Father Redmond was hanged by the yeomanry

Yeomanry is a designation used by a number of units and sub-units in the British Army Reserve which are descended from volunteer cavalry regiments that now serve in a variety of different roles.

History

Origins

In the 1790s, following the ...

, as was a maternal ancestor, William Kearney.

Education and early career

As a student, young John exhibited the seriousness that many would soon come to associate with him. Educated by theJesuits

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

at Clongowes Wood College

Clongowes Wood College SJ is a Catholic voluntary boarding school for boys near Clane, County Kildare, Ireland, founded by the Jesuits in 1814. It features prominently in James Joyce's semi-autobiographical novel '' A Portrait of the Artist ...

, he was primarily interested in poetry and literature, played the lead in school theatricals and was regarded as the best speaker in the school's debating society. After finishing at Clongowes, Redmond attended Trinity College Dublin

Trinity College Dublin (), officially titled The College of the Holy and Undivided Trinity of Queen Elizabeth near Dublin, and legally incorporated as Trinity College, the University of Dublin (TCD), is the sole constituent college of the Unive ...

to study law, but his father's ill health led him to abandon his studies before taking a degree. In 1876 he left to live with his father in London, acting as his assistant in Westminster

Westminster is the main settlement of the City of Westminster in Central London, Central London, England. It extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street and has many famous landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Buckingham Palace, ...

, where he developed more fascination for politics than for law. He first came into contact with Michael Davitt

Michael Davitt (25 March 1846 – 30 May 1906) was an Irish republicanism, Irish republican activist for a variety of causes, especially Home Rule (Ireland), Home Rule and land reform. Following an eviction when he was four years old, Davitt's ...

on the occasion of a reception held in London to celebrate the release of the famous Fenian

The word ''Fenian'' () served as an umbrella term for the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) and their affiliate in the United States, the Fenian Brotherhood. They were secret political organisations in the late 19th and early 20th centuries ...

prisoner. As a clerk in the House of Commons, he increasingly identified himself with the fortunes of Charles Stewart Parnell

Charles Stewart Parnell (27 June 1846 – 6 October 1891) was an Irish nationalist politician who served as a Member of Parliament (United Kingdom), Member of Parliament (MP) in the United Kingdom from 1875 to 1891, Leader of the Home Rule Leag ...

, one of the founders of the Irish Land League

The Irish National Land League ( Irish: ''Conradh na Talún''), also known as the Land League, was an Irish political organisation of the late 19th century which organised tenant farmers in their resistance to exactions of landowners. Its prima ...

and a noted obstructionist in the Commons.

Political profession and marriage

Redmond first attended political meetings with Parnell in 1879. Upon his father's death later in 1880, he wrote to Parnell asking for adoption as the Nationalist Party (from 1882 theIrish Parliamentary Party

The Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP; commonly called the Irish Party or the Home Rule Party) was formed in 1874 by Isaac Butt, the leader of the Nationalist Party, replacing the Home Rule League, as official parliamentary party for Irish nati ...

) candidate in the by-election to fill the open seat, but was disappointed to learn that Parnell had already promised the next vacancy to his secretary Tim Healy. Nevertheless, Redmond supported Healy as the nominee, and when another vacancy arose, this time in New Ross

New Ross (, formerly ) is a town in southwest County Wexford, Republic of Ireland, Ireland, on the River Barrow on the border with County Kilkenny, northeast of Waterford. In 2022, it had a population of 8,610, making it the fourth-largest t ...

, he won the election unopposed as the Parnellite candidate for the seat. On election (31 January 1881), he rushed to the House of Commons, made his maiden speech the next day amid stormy scenes following the arrest of Michael Davitt, then a Land League leader, and was ejected from the Commons all on the same evening. He served as MP for New Ross from 1881 to 1885, for North Wexford from 1885 to 1891 and for Waterford City

Waterford ( ) is a city in County Waterford in the south-east of Ireland. It is located within the province of Munster. The city is situated at the head of Waterford Harbour. It is the oldestJames Dalton and whom he spent much of his time with. His marriage was short-lived but happy: his wife Johanna died early in 1889 after bearing him three children. He also travelled in 1884, 1886 and 1904 to the US, where he was to use more extreme language but found his contact with Irish-American extremism daunting. His Australian experience, on the other hand, had a strong influence on his political outlook, causing him to embrace an Irish version of Liberal Imperialism and to remain anxious to retain Irish representation and Ireland's voice at Westminster even after the implementation of home rule. During the debate which followed Gladstone's conversion to Home Rule in 1886, he declared:

campaigning constitutionally for

The first election of January 1910 changed everything to Redmond's advantage, returning a

The first election of January 1910 changed everything to Redmond's advantage, returning a

But like most leaders in the nationalist scene, not least his successors in the republican scene, he knew little of Ulster or the intensity of Unionist sentiment against home rule. His successor, John Dillon, claimed that Redmond had removed all the obstacles to Irish unity except those of the Ulster unionists. He had persuaded British public and political opinion of all hues of its merits. William O'Brien and his dissident

But like most leaders in the nationalist scene, not least his successors in the republican scene, he knew little of Ulster or the intensity of Unionist sentiment against home rule. His successor, John Dillon, claimed that Redmond had removed all the obstacles to Irish unity except those of the Ulster unionists. He had persuaded British public and political opinion of all hues of its merits. William O'Brien and his dissident

On the outbreak of

On the outbreak of

''

John Redmond Ireland's Forgotten Patriot

John Redmond Portrait Gallery: UCC Multitext Project in Irish History

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Redmond, John 1856 births 1918 deaths Home Rule League MPs Irish Parliamentary Party MPs Parnellite MPs United Irish League Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for County Waterford constituencies (1801–1922) Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for County Wexford constituencies (1801–1922) UK MPs 1886–1892 UK MPs 1892–1895 UK MPs 1895–1900 UK MPs 1900–1906 UK MPs 1906–1910 UK MPs 1910 UK MPs 1910–1918 Alumni of Trinity College Dublin Redmond, John Edward People educated at Clongowes Wood College

"As a Nationalist, I do not regard as entirely palatable the idea that forever and a day Ireland's voice should be excluded from the councils of an empire which the genius and valour of her sons have done so much to build up and of which she is to remain".In 1899 Redmond married his second wife, Ada Beesley, an English Protestant who, after his death, converted to Catholicism.

Leader of the Parnellite party

Having belatedly become a barrister by completing his terms at theKing's Inns

The Honorable Society of King's Inns () is the "Inn of Court" for the Bar of Ireland. Established in 1541, King's Inns is Ireland's oldest school of law and one of Ireland's significant historical environments.

The Benchers of King's Inns aw ...

, Dublin, being called to the Irish bar in 1887 (and to the English bar a year later), Redmond busied himself with agrarian cases during the Plan of Campaign

The Plan of Campaign was a strategy, stratagem adopted in Ireland between 1886 and 1891, co-ordinated by Irish politicians for the benefit of tenant farmers, against mainly absentee landlord, absentee and rack-rent landlords. It was launched to ...

. In 1888, following a strong and conceivably intimidatory speech, he received five weeks' imprisonment with hard labour. A loyal supporter of Parnell, Redmond—like Davitt—was deeply opposed to the use of physical force and was committed to political change by constitutional means,O'Riordan, Tomás: UCC The initialism UCC may stand for:

Law

* Uniform civil code of India, referring to proposed Civil code in the legal system of India, which would apply equally to all irrespective of their religion

* Uniform Commercial Code, a 1952 uniform act to ...

br>Multitext Project in Irish History John Redmondcampaigning constitutionally for

Home Rule

Home rule is the government of a colony, dependent country, or region by its own citizens. It is thus the power of a part (administrative division) of a state or an external dependent country to exercise such of the state's powers of governan ...

as an interim form of All-Ireland self-government within the United Kingdom.

In November 1890 the Irish Parliamentary Party split over Parnell's leadership when his long-standing adultery with Katharine O'Shea

Katharine Parnell (née Wood; 30 January 1846 – 5 February 1921), known before her second marriage as Katharine O'Shea and popularly as Kitty O'Shea, was an English woman of aristocratic background whose adulterous relationship with Irish ...

was revealed in a spectacular divorce case. Redmond stood by Parnell and worked to keep the minority faction active. When Parnell died in 1891, Redmond became MP for Waterford and took over leadership of the Parnellite faction of the split party. Redmond lacked Parnell's oratory and charisma but did demonstrate both his organisational ability and his considerable rhetorical skills. He raised funds for the Parnell Monument in Dublin.

The larger anti-Parnellite group formed the Irish National Federation

The Irish National Federation (INF) was a nationalist political party in Ireland. It was founded in 1891 by former members of the Irish National League (INL), after a split in the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) on the leadership of Charles ...

(INF) under John Dillon

John Dillon (4 September 1851 – 4 August 1927) was an Irish politician from Dublin, who served as a Member of Parliament (MP) for over 35 years and was the last leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party. By political disposition, Dillon was a ...

. After 1895 the Conservatives and Liberal Unionists, who were opposed to Home Rule, controlled Parliament. Redmond supported the Unionist Irish Secretary Gerald Balfour programme of Constructive Unionism, while advising the Tory Government that its self-declared policy of "killing Home Rule with kindness" would not achieve its objective. The Unionists bought out most of the Protestant landowners, thereby reducing rural unrest in Ireland. Redmond dropped all interest in agrarian radicalism and, unlike the mainstream nationalists, worked constructively alongside Unionists, such as Horace Plunkett

Sir Horace Curzon Plunkett (24 October 1854 – 26 March 1932), was an Anglo-Irish agricultural reformer, pioneer of agricultural cooperatives, Unionist MP, supporter of Home Rule, Irish Senator and author.

Plunkett, a younger brother of J ...

, in the Recess Committee of 1895. It led to the establishment of a department of agriculture in 1899. He further argued that the land reforms and democratisation of elected local government under the Local Government (Ireland) Act 1898

The Local Government (Ireland) Act 1898 ( 61 & 62 Vict. c. 37) was an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland that established a system of local government in Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots diale ...

would in fact stimulate demands for Home Rule rather than dampen them, as was the case.

Home Rule and the Liberals

When on 6 February 1900, through the initiative ofWilliam O'Brien

William O'Brien (2 October 1852 – 25 February 1928) was an Irish nationalist, journalist, agrarian agitator, social revolutionary, politician, party leader, newspaper publisher, author and Member of Parliament (MP) in the House of Commons of ...

and his United Irish League

The United Irish League (UIL) was a nationalist political party in Ireland, launched 23 January 1898 with the motto ''"The Land for the People"''. Its objective to be achieved through agrarian agitation and land reform, compelling larger grazi ...

(UIL), the INL and the INF re-united again within the Irish Parliamentary Party, Redmond was elected its chairman (leader), a position he held until his death in 1918—a longer period than any other nationalist leader, except Éamon de Valera

Éamon de Valera (; ; first registered as George de Valero; changed some time before 1901 to Edward de Valera; 14 October 1882 – 29 August 1975) was an American-born Irish statesman and political leader. He served as the 3rd President of Ire ...

and Daniel O'Connell

Daniel(I) O’Connell (; 6 August 1775 – 15 May 1847), hailed in his time as The Liberator, was the acknowledged political leader of Ireland's Roman Catholic majority in the first half of the 19th century. His mobilisation of Catholic Irelan ...

. However, Redmond, a Parnellite, was chosen as a compromise due to the personal rivalries between the anti-Parnellite Home Rule leaders. Therefore, he never had as much control over the party as his predecessor, his authority and leadership a balancing act having to contend with such powerful colleagues as John Dillon

John Dillon (4 September 1851 – 4 August 1927) was an Irish politician from Dublin, who served as a Member of Parliament (MP) for over 35 years and was the last leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party. By political disposition, Dillon was a ...

, William O'Brien

William O'Brien (2 October 1852 – 25 February 1928) was an Irish nationalist, journalist, agrarian agitator, social revolutionary, politician, party leader, newspaper publisher, author and Member of Parliament (MP) in the House of Commons of ...

, Timothy Healy and Joseph Devlin

Joseph Devlin (13 February 1871 – 18 January 1934) was an Irish journalist and influential nationalist politician. He was a Member of Parliament (MP) for the Irish Parliamentary Party in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom (1902-192 ...

. He nevertheless led the Party successfully through the September 1900 general election.

Then followed William O'Brien's amicable and conciliatory Land Conference The Land Conference was a successful conciliatory negotiation held in the Mansion House in Dublin, Ireland between 20 December 1902 and 4 January 1903. In a short period it produced a unanimously agreed report recommending an amiable solution to t ...

of 1902 involving leading landlords under Lord Dunraven and tenant representatives O'Brien, Redmond, Timothy Harrington

Timothy Charles Harrington (1851 – 12 March 1910) was an Irish journalist, barrister, Irish nationalism, nationalist politician and Member of Parliament (United Kingdom), Member of Parliament (MP) in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom ...

and T. W. Russell for the Ulster tenants. It resulted in the enactment of the unprecedented Land Purchase (Ireland) Act 1903

The Land Acts (officially Land Law (Ireland) Acts) were a series of measures to deal with the question of tenancy contracts and peasant proprietorship of land in Ireland in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Five such acts were introduced by ...

. Redmond first sided with O'Brien's new strategy of "conciliation plus business", but refused O'Brien's demand to rebuke Dillon for his criticism of the Act, leading to O'Brien's resignation from the party in November 1903.Maume, Patrick, ''Who's Who in The long Gestation'', p. 241, Gill & Macmillan (1999) Redmond approved of the unsuccessful 1904 devolution proposals of the Irish Reform Association

The Irish Reform Association (1904–1905) was an attempt to introduce limited Devolution, devolved self-government to Ireland by a group of reform oriented Unionism in Ireland, Irish unionist Protestant Ascendancy, land owners who proposed to i ...

. Despite their differences, Redmond and Dillon made a good team: Redmond, who was a fine speaker and liked the House of Commons, dealt with the British politicians, while Dillon, who disliked London, the Commons and their influence on Irish politicians, stayed in Ireland and kept Redmond in touch with national feelings.Collins, M.E., ''Movements for reform 1870–1914'', p. 127, Edco Publishing (2004)

Though government had been dominated by the Conservative Party for more than a decade, the new century saw much favourable legislation enacted in Ireland's interest. An electoral swing to the Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world.

The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left. For example, while the political systems ...

in the 1906 general election

The following elections occurred in the year 1906.

Asia

* 1906 Persian legislative election

Europe

* 1906 Belgian general election

* 1906 Croatian parliamentary election

* Denmark

** 1906 Danish Folketing election

** 1906 Danish Landsting e ...

renewed Redmond's opportunities for working with government policy. The Liberals, however, did not yet back his party's demands for full Home Rule, which contributed to a renewal of agrarian radicalism in the ranch wars of 1906–1910. Redmond's low-key and conciliatory style of leadership gave the impression of weakness but reflected the problem of keeping together a factionalised party. He grew in stature after 1906 and especially after 1910. As far as Redmond was concerned, the Home Rule movement was interested in promoting Irish nationality within the British Empire, but it was also a movement with a visceral antipathy to the English and their colonies.

Redmond initially supported the introduction of the Liberals' 1907 Irish Council Bill, which was also supported by O'Brien and IPP members who initially voted for the first reading. Redmond said, "if this measure fulfilled certain conditions I laid down we should consider it an aid to Home Rule". When this was rejected by Dillon and the UIL, Redmond, fearing another Party split, quietly endured Dillon's dictate of distancing the Irish Party from any understanding with the landlord class.

The first election of January 1910 changed everything to Redmond's advantage, returning a

The first election of January 1910 changed everything to Redmond's advantage, returning a hung parliament

A hung parliament is a term used in legislatures primarily under the Westminster system (typically employing Majoritarian representation, majoritarian electoral systems) to describe a situation in which no single political party or pre-existing ...

in which his parliamentary party held the balance of power at Westminster

Westminster is the main settlement of the City of Westminster in Central London, Central London, England. It extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street and has many famous landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Buckingham Palace, ...

; this marked a high point in his political career. The previous year, the Lords had blocked the budget of the Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and the head of HM Treasury, His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, t ...

, David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. A Liberal Party (United Kingdom), Liberal Party politician from Wales, he was known for leadi ...

. Redmond's party supported the Liberals in introducing a bill to curb the power of the House of Lords

The House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the lower house, the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England. One of the oldest ext ...

, which, after a second election in December 1910 had generated an almost identical result to the one in January, became the Parliament Act 1911

The Parliament Act 1911 ( 1 & 2 Geo. 5. c. 13) is an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It is constitutionally important and partly governs the relationship between the House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two Houses of Parl ...

. Irish Home Rule (which the Lords had blocked in 1893) now became a realistic possibility. Redmond used his leverage to persuade the Liberal government of H. H. Asquith

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith (12 September 1852 – 15 February 1928) was a British statesman and Liberal Party (UK), Liberal politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1908 to 1916. He was the last ...

to introduce the Third Home Rule Bill

The Government of Ireland Act 1914 ( 4 & 5 Geo. 5. c. 90), also known as the Home Rule Act, and before enactment as the Third Home Rule Bill, was an Act passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom intended to provide home rule (self-gover ...

in April 1912, to grant Ireland national self-government. The Lords no longer had the power to block such a bill, only to delay its enactment for two years. Home Rule had reached the pinnacle of its success and Redmond had gone much further than any of his predecessors in shaping British politics to the needs of the Irish.

Redmond was an opponent of votes for women and had abstained on votes regarding the topic. On 1 April 1912 he informed a delegation of the Irish Women's Franchise League

The Irish Women's Franchise League was an organisation for women's suffrage which was set up in Dublin in November 1908. Its founder members included Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington, Margaret Cousins, Francis Sheehy-Skeffington and James H. Cousins. Tho ...

that he would not support giving women the vote if home rule was granted. Redmond's opposition to female suffrage drew the ire of the suffragettes leading to the defacing of a statue of Redmond in 1913 by a suffragette protestor.

For all its reservations, the Home Rule Bill was for Redmond the fulfilment of a lifelong dream. "If I may say so reverently", he told the House of Commons, "I personally thank God that I have lived to see this day". But Asquith did not incorporate into the bill any significant concessions to Ulster Unionists

The Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) is a unionist political party in Northern Ireland. The party was founded as the Ulster Unionist Council in 1905, emerging from the Irish Unionist Alliance in Ulster. Under Edward Carson, it led unionist opposit ...

, who then campaigned relentlessly against it. Nonetheless, by 1914 Redmond had become a nationalist hero of Parnellite stature and could have had every expectation of becoming head of a new Irish government in Dublin

Dublin is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. Situated on Dublin Bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, and is bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, pa ...

.

Home rule passed

But like most leaders in the nationalist scene, not least his successors in the republican scene, he knew little of Ulster or the intensity of Unionist sentiment against home rule. His successor, John Dillon, claimed that Redmond had removed all the obstacles to Irish unity except those of the Ulster unionists. He had persuaded British public and political opinion of all hues of its merits. William O'Brien and his dissident

But like most leaders in the nationalist scene, not least his successors in the republican scene, he knew little of Ulster or the intensity of Unionist sentiment against home rule. His successor, John Dillon, claimed that Redmond had removed all the obstacles to Irish unity except those of the Ulster unionists. He had persuaded British public and political opinion of all hues of its merits. William O'Brien and his dissident All-for-Ireland League

The All-for-Ireland League (AFIL) was an Irish, Munster-based political party (1909–1918). Founded by William O'Brien Member of parliament, MP, it generated a new national movement to achieve agreement between the different parties concerned o ...

warned in similar vein, that the volatile Northern Ireland situation was left unresolved.

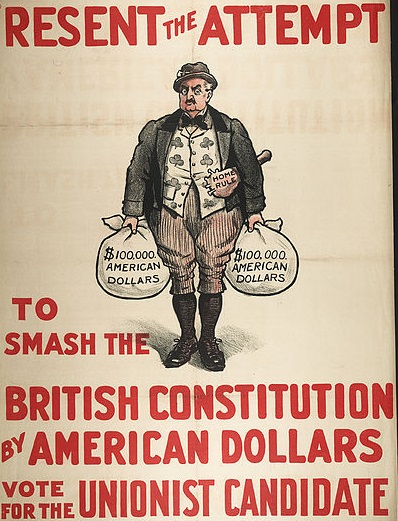

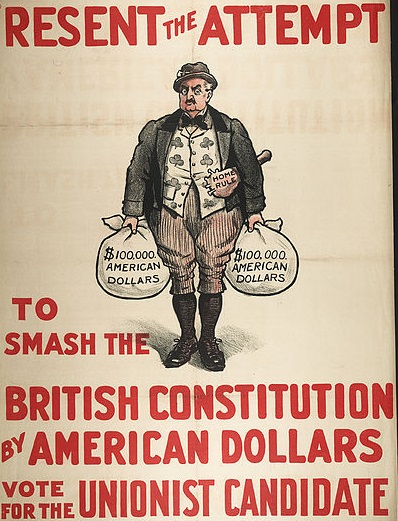

Home rule was vehemently opposed by many Irish Protestants

Protestantism is a Christianity, Christian community on the island of Ireland. In the 2011 census of Northern Ireland, 48% (883,768) described themselves as Protestant, which was a decline of approximately 5% from the 2001 census. In the 2011 ...

, the Irish Unionist Party

The Irish Unionist Alliance (IUA), also known as the Irish Unionist Party, Irish Unionists or simply the Unionists, was a unionist political party founded in Ireland in 1891 from a merger of the Irish Conservative Party and the Irish Loyal and ...

and Ulster's Orange Order

The Loyal Orange Institution, commonly known as the Orange Order, is an international Protestant fraternal order based in Northern Ireland and primarily associated with Ulster Protestants. It also has lodges in England, Grand Orange Lodge of ...

, who feared domination in an overwhelmingly Catholic state. Unionists also feared economic problems, namely that the predominantly agricultural Ireland would impose tariffs on British goods, leading to restrictions on the importation of industrial produce; the main location of Ireland's industrial development was Ulster

Ulster (; or ; or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional or historic provinces of Ireland, Irish provinces. It is made up of nine Counties of Ireland, counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United Kingdom); t ...

, the north-east of the island, the only part of Ireland dominated by unionists. Most unionist leaders, especially Sir Edward Carson

Edward Henry Carson, Baron Carson, Privy Council (United Kingdom), PC, Privy Council of Ireland, PC (Ire), King's Counsel, KC (9 February 1854 – 22 October 1935), from 1900 to 1921 known as Sir Edward Carson, was an Irish unionist politician ...

—with whom Redmond always had a good personal relationship, based on shared experiences at Trinity College Dublin

Trinity College Dublin (), officially titled The College of the Holy and Undivided Trinity of Queen Elizabeth near Dublin, and legally incorporated as Trinity College, the University of Dublin (TCD), is the sole constituent college of the Unive ...

and the Irish bar

The Bar of Ireland () is the professional association of barristers for Ireland, with over 2,000 members. It is based in the Law Library, with premises in Dublin and Cork. It is governed by the General Council of the Bar of Ireland, commonly c ...

—threatened the use of force to prevent home rule, helped by their supporters in the British Conservative Party. Redmond misjudged them as merely bluffing. Carson predicted that if any attempt to coerce any part of Ulster were made, "a united Ireland within the lifetime of anyone now living would be out of the question".

During negotiations early in 1914, two lines of concessions for the Carsonites were formulated: autonomy for Ulster in the form of 'Home Rule within Home Rule', which Redmond was inclined to, or alternatively the Lloyd George scheme of three years as the time limit for temporary exclusion. Redmond grudgingly acquiesced to this as "the price of peace". From the moment Carson spurned 'temporary' exclusion, the country began a plunge into anarchy. The situation took on an entirely new aspect in late March with the Curragh Mutiny together with the spectre of civil war on the part of the Ulster Covenant

Ulster's Solemn League and Covenant, commonly known as the Ulster Covenant, was signed by nearly 500,000 people on and before 28 September 1912, in protest against the Third Home Rule Bill introduced by the British Government in the same year.

...

ers, who formed the Ulster Volunteers

The Ulster Volunteers was an Irish unionist, loyalist paramilitary organisation founded in 1912 to block domestic self-government ("Home Rule") for Ireland, which was then part of the United Kingdom. The Ulster Volunteers were based in the ...

to oppose Home Rule, forcing Redmond to then in July take over control of their counterpart, the Irish Volunteers

The Irish Volunteers (), also known as the Irish Volunteer Force or the Irish Volunteer Army, was a paramilitary organisation established in 1913 by nationalists and republicans in Ireland. It was ostensibly formed in response to the format ...

, established in November 1913 to enforce Home Rule.

Asquith conceded to the Lords' demand to have the Government of Ireland Act 1914

The Government of Ireland Act 1914 ( 4 & 5 Geo. 5. c. 90), also known as the Home Rule Act, and before enactment as the Third Home Rule Bill, was an Act passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom intended to provide home rule (self-gover ...

, which had passed all stages in the Commons, amended to temporarily exclude the six counties of Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ; ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, part of the United Kingdom in the north-east of the island of Ireland. It has been #Descriptions, variously described as a country, province or region. Northern Ireland shares Repub ...

, which for a period would continue to be governed by London, not Dublin, and to later make some special provision for them. A Buckingham Palace Conference failed to resolve the entangled situation. Strongly opposed to the partition of Ireland

The Partition of Ireland () was the process by which the Government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland (UK) divided Ireland into two self-governing polities: Northern Ireland and Southern Ireland (the area today known as the R ...

in any form, Redmond and his party reluctantly agreed to what they understood would be a ''trial'' exclusion of now six years; under Redmond's aspiration that "Ulster will have to follow", he was belatedly prepared to concede a large measure of autonomy to it to come in.

Redmond's confidence was strong and communicated itself to Ireland. But whatever could be said to shake confidence was said by William O'Brien

William O'Brien (2 October 1852 – 25 February 1928) was an Irish nationalist, journalist, agrarian agitator, social revolutionary, politician, party leader, newspaper publisher, author and Member of Parliament (MP) in the House of Commons of ...

and Tim Healy, who denounced the Bill as worthless when linked to the plan of even temporary partition and declared that, whatever the Government might say at present, "we had not yet reached the end of their concessions". On the division, they and their All-for-Ireland League

The All-for-Ireland League (AFIL) was an Irish, Munster-based political party (1909–1918). Founded by William O'Brien Member of parliament, MP, it generated a new national movement to achieve agreement between the different parties concerned o ...

abstained, so that the majority dropped from 85 to 77. Using the Parliament Act, the Lords was deemed to have passed the Act; it received the Royal Assent

Royal assent is the method by which a monarch formally approves an act of the legislature, either directly or through an official acting on the monarch's behalf. In some jurisdictions, royal assent is equivalent to promulgation, while in othe ...

in September 1914.

European conflict intervenes

On the outbreak of

On the outbreak of World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

in August 1914, the Home Rule Act was suspended for the duration of the conflict. Judged from the perspective of that time, Redmond had won a form of triumph: he had secured the passing of Home Rule with the provision that the implementation of the measure would be delayed "not later than the end of the present war", which "would be bloody but short-lived". His Unionist opponents were confused and dismayed by the passing of the Home Rule Act and by the absence of any definite provisions for the exclusion of Ulster. In two speeches delivered by Redmond in August and September 1914, deemed as critical turning points in the Home Rule process, he stated: "Armed Nationalist Catholics in the South will be only too glad to join arms with the armed Protestant Ulstermen in the North. Is it too much to hope that out of this situation there may spring a result which will be good, not merely for the Empire, but good for the future welfare and integrity of the Irish nation?"Under these circumstances, any political bargaining might well have been disastrous to Home Rule. Redmond desperately wanted and needed a rapid enactment of the Home Rule Act, and undoubtedly his words were a means to that end. He called on the country to support the Allied and British war effort and Britain's commitment under the

Triple Entente

The Triple Entente (from French meaning "friendship, understanding, agreement") describes the informal understanding between the Russian Empire, the French Third Republic, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was built upon th ...

; this was a calculated response to the situation principally in the belief that the attained measure of self-government would be granted in full after the war and to be in a stronger position to stave off a final partition of Northern Ireland. His added hope was that the common sacrifice by Irish nationalists and Unionists would bring them closer together, but above all that nationalists could not afford to allow Ulster Unionists to reap the benefit of being the only Irish to support the war effort, when they spontaneously enlisted in their 36th (Ulster) Division

The 36th (Ulster) Division was an infantry division of the British Army, part of Lord Kitchener's New Army, formed in September 1914. Originally called the ''Ulster Division'', it was made up of mainly members of the Ulster Volunteers, who f ...

. He said Let Irishmen come together in the trenches and risk their lives together and spill their blood together, and I say there is no power on earth that when they come home can induce them to turn as enemies upon one another.Finnan, Joseph. ''John Redmond and Irish Unity: 1912 – 1918''. Syracuse University Press, 2004. pp.99–101Redmond also argued that "No people can be said to have rightly proved their nationhood and their power to maintain it until they have demonstrated their military prowess". He praised Irish soldiers, "with their astonishing courage and their beautiful faith, with their natural military genius ��offering up their supreme sacrifice of life with a smile on their lips because it was given for Ireland". Speaking at Maryborough on 16 August 1914, he addressed a 2,000-strong assembly of Irish Volunteers, some armed, saying he had told the British Parliament that:

for the first time in the history of the connection between England and Ireland, it was safe to-day for England to withdraw her armed troops from our country and that the sons of Ireland themselves, North and South, Catholic and Protestant, and whatever the origin of their race might have been – Williamite, Cromwellian, or old Celtic – standing shoulder to shoulder, would defend the good order and peace of Ireland, and defend her shores against any foreign foe.

Nationalists split

Redmond's appeal, however, to the Irish Volunteers to also enlist caused them to split; a large majority of 140,000 followed Redmond and formed theNational Volunteers

The National Volunteers were the majority faction of the Irish Volunteers that sided with Irish Parliamentary Party leader John Redmond after the movement split over the question of the Volunteers' Ireland and World War I, role in World War I.

O ...

, who enthusiastically enlisted in Irish regiment

The Irish military diaspora refers to the many people of either Irish birth or extraction (see Irish diaspora) who have served in overseas armed forces, military forces, regardless of rank, duration of service, or success.

Many overseas militar ...

s of the 10th and 16th (Irish) Division

The 16th (Irish) Division was an infantry division of the British Army, raised for service during World War I. The division was a voluntary 'Service' formation of Lord Kitchener's New Armies, created in Ireland from the 'National Volunteers', ...

s of the New British Army, while a minority of around 9,700 members remained as the original Irish Volunteers. Redmond believed that the German Empire

The German Empire (),; ; World Book, Inc. ''The World Book dictionary, Volume 1''. World Book, Inc., 2003. p. 572. States that Deutsches Reich translates as "German Realm" and was a former official name of Germany. also referred to as Imperia ...

's hegemony and military expansion threatened the freedom of Europe and that it was Ireland's duty, having achieved future self-government:

"to the best of her ability to go where ever the firing line extends, in defence of right, of freedom and of religion in this war. It would be a disgrace forever to our country otherwise". (Woodenbridge speech to the Irish Volunteers, 20 September 1914)Redmond requested the

War Office

The War Office has referred to several British government organisations throughout history, all relating to the army. It was a department of the British Government responsible for the administration of the British Army between 1857 and 1964, at ...

to allow the formation of a separate Irish Brigade as had been done for the Ulster Volunteers, but Britain was suspicious of Redmond. His plan was that post-war the Irish Brigade and National Volunteers would provide the basis for an Irish Army, capable of enforcing Home Rule on reluctant Ulster Unionists. Eventually he was granted the gesture of the 16th (Irish) Division which, with the exception of its Irish General William Hickie at first had mostly English officers, unlike the Ulster Division which had its own reserve militia officers, since most of the experienced officers in Ireland had already been posted to the 10th (Irish) Division and most Irish recruits enlisting in the new army lacked the military training to act as officers. Redmond's own son, William Redmond, enlisted, as did his own brother Major Willie Redmond

William Hoey Kearney Redmond (13 April 1861 – 7 June 1917) was an Irish Irish nationalism, nationalist politician who served as a Member of Parliament (United Kingdom), Member of Parliament (MP). He was also a lawyer and soldier Denman, Teren ...

MP, despite being aged over 50 years. They belonged to a group of five Irish MPs who enlisted, the others J. L. Esmonde, Stephen Gwynn

Stephen Lucius Gwynn (13 February 1864 – 11 June 1950) was an Irish journalist, biographer, author, poet and Protestant Nationalist politician. As a member of the Irish Parliamentary Party he represented Galway city as its Member of Parliamen ...

, and D. D. Sheehan as well as former MP Tom Kettle

Thomas Michael Kettle (9 February 1880 – 9 September 1916) was an Ireland, Irish economist, journalist, barrister, writer, war poet, soldier and Irish Home Rule Bill, Home Rule politician. As a member of the Irish Parliamentary Party, he was ...

.

Redmond was and is still criticised for having encouraged so many Irish to fight in the Great War. However the Irish historian J. J. Lee wrote: "Redmond could have tactically done nothing other than support the British war campaign; . . . nobody committed to Irish unity could have behaved other than Redmond did at the time. Otherwise, there would be no chance whatever of a united Ireland, in which Redmond passionately believed".

Easter Rising and aftermath

During 1915 Redmond felt secure in his course and that the path was already partly cleared for Home Rule to be achieved without bloodshed. He was supported by continued by-election successes of the IPP, and felt strong enough to turn down the offer of a cabinet seat, which would have offset Carson's appointment to the cabinet but would have been unpopular in Ireland. Even in 1916, he felt supremely confident and optimistic despite timely warnings fromBonar Law

Andrew Bonar Law (; 16 September 1858 – 30 October 1923) was a British statesman and politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from October 1922 to May 1923.

Law was born in the British colony of New Brunswick (now a Canadi ...

of an impending insurrection. Redmond did not expect the 1916 Easter Rising

The Easter Rising (), also known as the Easter Rebellion, was an armed insurrection in Ireland during Easter Week in April 1916. The Rising was launched by Irish republicans against British rule in Ireland with the aim of establishing an ind ...

, which was staged by the remaining Irish Volunteers and the Irish Citizen Army

The Irish Citizen Army (), or ICA, was a paramilitary group first formed in Dublin to defend the picket lines and street demonstrations of the Irish Transport and General Workers' Union (ITGWU) against the police during the Great Dublin Lock ...

, led by a number of influential republicans

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

, under Patrick Pearse

Patrick Henry Pearse (also known as Pádraig or Pádraic Pearse; ; 10 November 1879 – 3 May 1916) was an Irish teacher, barrister, Irish poetry, poet, writer, Irish nationalism, nationalist, Irish republicanism, republican political activist a ...

. Pearse, who had in 1913 stood with Redmond on the same platform where the Rising now took place, had at that time praised Redmond's efforts in achieving the promise of Home Rule. Redmond later acknowledged that the Rising was a shattering blow to his lifelong policy of constitutional action. It equally helped fuel republican sentiment, particularly when General Maxwell executed the leaders of the Rising, treating them as traitors in wartime.

On 3 May 1916, after three of the Rising's leaders had been executed—Pearse, Thomas MacDonagh

Thomas Stanislaus MacDonagh (; 1 February 1878 – 3 May 1916) was an Irish political activist, poet, playwright, educationalist and revolutionary leader. He was one of the seven leaders of the Easter Rising of 1916, a signatory of the Proclama ...

and Tom Clarke—Redmond said in the House of Commons: "This outbreak, happily, seems to be over. It has been dealt with firmness, which was not only right, but it was the duty of the Government to so deal with it".House of Commons debate, 3 May 1916''

Hansard

''Hansard'' is the transcripts of parliamentary debates in Britain and many Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth countries. It is named after Thomas Curson Hansard (1776–1833), a London printer and publisher, who was the first official printe ...

''. However, he urged the Government "not to show undue hardship or severity to the great masses of those who are implicated n the Rising. Redmond's plea, and John Dillon's, that the rebels be treated leniently were ignored.

There followed Asquith's attempt to introduce Home Rule in July 1916. David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. A Liberal Party (United Kingdom), Liberal Party politician from Wales, he was known for leadi ...

, recently appointed Secretary of State for War, was sent to Dublin to offer this to the leaders of the Irish Party, Redmond and Dillon. The scheme revolved around partition, officially a temporary arrangement, as understood by Redmond. Lloyd George, however, gave the Ulster leader Carson a written guarantee that Ulster would not be forced in. His tactic was to see that neither side would find out before a compromise was implemented. A modified Act of 1914 had been drawn up by the Cabinet on 17 June. The Act had two amendments enforced by Unionists on 19 July: permanent exclusion of Ulster, and a reduction of Ireland's representation in the Commons. Lloyd George informed Redmond of this on 22 July 1916, and Redmond accused the government of treachery. This was decisive to the future fortunes of the Home Rule movement; the Lloyd George debacle of 22 July finished the constitutional party, overthrew Redmond's power and left him utterly demoralised. It simultaneously discredited the politics of consent and created the space for radical alternatives. Redmond, after 1916 was increasingly eclipsed by ill-health, the rise of Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin ( ; ; ) is an Irish republican and democratic socialist political party active in both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

The History of Sinn Féin, original Sinn Féin organisation was founded in 1905 by Arthur Griffit ...

and the growing dominance of Dillon within the Irish Party.

June 1917 brought a severe personal blow to Redmond when his brother Willie

Willy or Willie is a masculine, male given name, often a diminutive form of William or Wilhelm, and occasionally a nickname. It may refer to:

People Given name or nickname

* Willie Allen (basketball) (born 1949), American basketball player and ...

died in action on the front at the onset of the Battle of Messines offensive in Flanders

Flanders ( or ; ) is the Dutch language, Dutch-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to culture, la ...

; his vacant seat in East Clare was then won in July by Éamon de Valera

Éamon de Valera (; ; first registered as George de Valero; changed some time before 1901 to Edward de Valera; 14 October 1882 – 29 August 1975) was an American-born Irish statesman and political leader. He served as the 3rd President of Ire ...

, the most senior surviving commandant of the Easter insurgents. It was one of three by-election gains by Sinn Féin, the small separatist party that had played no part in the Rising, but was wrongly blamed by Britain and the Irish media. It was then taken over by surviving Rising leaders, under de Valera and the IRB. Just at this time, Redmond made a desperate effort to broker a new compromise with Irish unionists, when he accepted Lloyd George's proposal for a national convention to resolve the problem of Home Rule and draft a constitution for Ireland.

Defeat and death

AnIrish Convention

The Irish Convention was an assembly which sat in Dublin, Ireland from July 1917 until March 1918 to address the '' Irish question'' and other constitutional problems relating to an early enactment of self-government for Ireland, to debate it ...

of around one hundred delegates sat from July and ended in March 1918. Up until December 1917, Redmond used his influence to have a plan which had been put forward by the Southern Unionist leader Lord Midleton, accepted. It foresaw All-Ireland Home Rule with partial fiscal autonomy (until after the war, without customs and excise). All sides, including most Ulster delegates, wavered towards favouring agreement. Already ailing while attending the convention, his health permanently affected by an accident in 1912, Redmond also suffered assault on the street in Dublin by a crowd of young Sinn Féin supporters on his way to the convention, which included Todd Andrews

Christopher Stephen "Todd" Andrews (6 October 1901 – 11 October 1985) was an Irish republican and later a public servant. He participated in the Irish War of Independence and the Civil War but never stood for election or held public office.

...

. On 15 January, just when he intended to move a motion on his proposal to have the Midleton plan agreed, some nationalist colleagues—the prominent Catholic Bishop O'Donnell and MP Joseph Devlin

Joseph Devlin (13 February 1871 – 18 January 1934) was an Irish journalist and influential nationalist politician. He was a Member of Parliament (MP) for the Irish Parliamentary Party in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom (1902-192 ...

—expressed doubts. Rather than split the nationalist side, he withdrew his motion. A vital chance was lost.

He ended his participation by saying that under the circumstances he felt he could be of no further use to the Convention in the matter. His final word in the convention was the tragic one – ''Better for us never to have met than to have met and failed.'' Late in February the malady from which he was suffering grew worse. He left Dublin for London knowing that a settlement from the convention was impossible. An operation in March 1918 to remove an intestinal obstruction appeared to progress well at first, but then he suffered heart failure. He died a few hours later at a London nursing home on 6 March 1918. One of the last things he said to the Jesuit Father who was with him to the end, was, ''Father, I am a broken-hearted man''. At the convention, his last move was an adoption of O’Brien's policy of accommodating Unionist opposition in the North and in the South. It was too late. Had he joined O’Brien ten years before and carried the Irish Party with him, it is possible that Ireland's destiny would have been settled by evolution.

Condolences and expressions of sympathy were widely expressed. After a funeral service in Westminster Cathedral

Westminster Cathedral, officially the Metropolitan Cathedral of the Most Precious Blood, is the largest Catholic Church in England and Wales, Roman Catholic church in England and Wales. The shrine is dedicated to the Blood of Jesus Ch ...

his remains were interred, as requested in a manner characteristic of the man, in the family vault at the old Knight Hospitallers churchyard of Saint John's Cemetery, Wexford

Wexford ( ; archaic Yola dialect, Yola: ''Weiseforthe'') is the county town of County Wexford, Republic of Ireland, Ireland. Wexford lies on the south side of Wexford Harbour, the estuary of the River Slaney near the southeastern corner of the ...

town, amongst his own people rather than in the traditional burial place for Irish statesmen and heroes in Glasnevin Cemetery

Glasnevin Cemetery () is a large cemetery in Glasnevin, Dublin, Ireland which opened in 1832. It holds the graves and memorials of several notable figures, and has a museum.

Location

The cemetery is located in Glasnevin, Dublin, in two part ...

. The small, neglected cemetery near the town centre is kept locked to the public – his vault, which had been in a dilapidated state, has been only partially restored by Wexford County Council

Wexford County Council () is the local authority of County Wexford, Ireland. As a county council, it is governed by the Local Government Act 2001. The council is responsible for housing and community, roads and transportation, urban planning an ...

.

Party's demise

Redmond was succeeded in the party leadership by John Dillon and spared the experience of further political setbacks when after theGerman spring offensive

The German spring offensive, also known as ''Kaiserschlacht'' ("Kaiser's Battle") or the Ludendorff offensive, was a series of German Empire, German attacks along the Western Front (World War I), Western Front during the World War I, First Wor ...

of April 1918, Britain, caught in a desperate war of attrition, attempted to introduce conscription in Ireland linked with implementation of Home Rule. The Irish Nationalists led by Dillon walked out of the House of Commons and returned to Ireland to join in the widespread resistance and protests during the resulting conscription crisis.

The crisis boosted Sinn Féin so that in the December general election it won the vast majority of seats, leaving the Nationalist Party with only six seats for the 220,837 votes cast (21.7%) (down from 84 seats out of 103 in 1910). The party did not win a proportionate share of seats because the election was not run under a proportional representation

Proportional representation (PR) refers to any electoral system under which subgroups of an electorate are reflected proportionately in the elected body. The concept applies mainly to political divisions (Political party, political parties) amon ...

system, but on the 'first past the post' British electoral system. Unionists, on the other hand, won 26 seats for 287,618 (28.3%) of votes, whereas Sinn Féin votes were 476,087 (or 46.9%) for 48 seats, plus 25 uncontested, totalling 73 seats. In January 1919 a Unilateral Declaration of Independence

A unilateral declaration of independence (UDI) or "unilateral secession" is a formal process leading to the establishment of a new state by a subnational entity which declares itself independent and sovereign without a formal agreement with the ...

by the First Dáil

First most commonly refers to:

* First, the ordinal form of the number 1

First or 1st may also refer to:

Acronyms

* Faint Images of the Radio Sky at Twenty-Centimeters, an astronomical survey carried out by the Very Large Array

* Far Infrared a ...

attended by twenty-seven Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin ( ; ; ) is an Irish republican and democratic socialist political party active in both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

The History of Sinn Féin, original Sinn Féin organisation was founded in 1905 by Arthur Griffit ...

members (others were in jail or unable to attend) proclaimed an Irish Republic

The Irish Republic ( or ) was a Revolutionary republic, revolutionary state that Irish Declaration of Independence, declared its independence from the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland in January 1919. The Republic claimed jurisdict ...

. The subsequent parliament of the Second Dail was superseded by the establishment of the Irish Free State

The Irish Free State (6 December 192229 December 1937), also known by its Irish-language, Irish name ( , ), was a State (polity), state established in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. The treaty ended the three-ye ...

. The Irish Civil War

The Irish Civil War (; 28 June 1922 – 24 May 1923) was a conflict that followed the Irish War of Independence and accompanied the establishment of the Irish Free State, an entity independent from the United Kingdom but within the British Emp ...

followed.

Home Rule was finally implemented in 1921 under the Government of Ireland Act 1920

The Government of Ireland Act 1920 ( 10 & 11 Geo. 5. c. 67) was an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. The Act's long title was "An Act to provide for the better government of Ireland"; it is also known as the Fourth Home Rule Bi ...

which introduced two Home Rule parliaments, although only adopted by the six counties forming Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ; ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, part of the United Kingdom in the north-east of the island of Ireland. It has been #Descriptions, variously described as a country, province or region. Northern Ireland shares Repub ...

.

Legacy and personal vision

John Redmond's home town of Wexford remained a strongly Redmondite area for decades afterwards. The seat of Waterford city was one of the few outside Ulster not to be won by Sinn Féin in the 1918 general election. Redmond's son William Redmond represented the city until his death in 1932. A later IrishTaoiseach

The Taoiseach (, ) is the head of government or prime minister of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. The office is appointed by the President of Ireland upon nomination by Dáil Éireann (the lower house of the Oireachtas, Ireland's national legisl ...

(prime minister), John Bruton

John Gerard Bruton (18 May 1947 – 6 February 2024) was an Irish Fine Gael politician who served as Taoiseach from 1994 to 1997 and Leader of Fine Gael from 1990 to 2001. He held cabinet positions between 1981 and 1987, including twice ...

, hung a painting of Redmond, whom he regarded as his hero because of his perceived commitment to non-violence in Ireland, in his office in Ireland's Leinster House

Leinster House () is the seat of the Oireachtas, the parliament of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. Originally, it was the ducal palace of the Duke of Leinster, Dukes of Leinster.

Since 1922, it has been a complex of buildings which houses Oirea ...

Government Buildings. However, his successor Bertie Ahern

Bartholomew Patrick "Bertie" Ahern (born 12 September 1951) is an Irish former Fianna Fáil politician who served as Taoiseach from 1997 to 2008, and as Leader of Fianna Fáil from 1994 to 2008. A Teachta Dála (TD) from 1977 to 2011, he served ...

replaced the painting with one of Patrick Pearse.

Redmond's personal vision did not encompass a wholly independent Ireland. He referred to:

"that brighter day when the grant of full self-government would reveal to Britain the open secret of making Ireland her friend and helpmate, the brightest jewel in her crown of Empire".He had above all a conciliatory agenda; in his final words in parliament he expressed "a plea for concord between the two races that providence has designed should work as neighbours together". For him, Home Rule was an interim step for All-Ireland autonomy:

"His reward was to be repudiated and denounced by a generation which had yet to learn, as they learned three years later when they were forced to accept Partition, that true freedom is rarely served by bloodshed and violence, and that in politics compromise is inevitable. Yet it can be said of John Redmond that none of Ireland's sons had ever served her with greater sincerity or nobler purpose". Horgan, John J.: ''Parnell to Pearse'' p.323, Brown and Nolan Dublin (1948)

Notes, sources and citations

Footnotes

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * (1919) * * * *Citations

External links

*John Redmond Ireland's Forgotten Patriot

John Redmond Portrait Gallery: UCC Multitext Project in Irish History

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Redmond, John 1856 births 1918 deaths Home Rule League MPs Irish Parliamentary Party MPs Parnellite MPs United Irish League Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for County Waterford constituencies (1801–1922) Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for County Wexford constituencies (1801–1922) UK MPs 1886–1892 UK MPs 1892–1895 UK MPs 1895–1900 UK MPs 1900–1906 UK MPs 1906–1910 UK MPs 1910 UK MPs 1910–1918 Alumni of Trinity College Dublin Redmond, John Edward People educated at Clongowes Wood College

John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Second E ...

Redmond, John Edward

Alumni of King's Inns

Lawyers from County Wexford

Lawyers from County Waterford

People on Irish postage stamps