John Norris (soldier) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir John Norris, or Norreys (''ca.'' 1547 – 3 September 1597), of Rycote, Oxfordshire, and of Yattendon and Notley in Berkshire, was an

Sir John Norris, or Norreys (''ca.'' 1547 – 3 September 1597), of Rycote, Oxfordshire, and of Yattendon and Notley in Berkshire, was an

In 1577, Norreys led a force of English volunteers to the

In 1577, Norreys led a force of English volunteers to the

Upon news of the siege of

Upon news of the siege of  On Wednesday 17 April 1589 (although another source gives the date of departure as 18 April), Norreys set out with Drake at the head of a 23,000 strong expeditionary force (which included 19,000 troops and is now termed the

On Wednesday 17 April 1589 (although another source gives the date of departure as 18 April), Norreys set out with Drake at the head of a 23,000 strong expeditionary force (which included 19,000 troops and is now termed the

Sir John Norris, or Norreys (''ca.'' 1547 – 3 September 1597), of Rycote, Oxfordshire, and of Yattendon and Notley in Berkshire, was an

Sir John Norris, or Norreys (''ca.'' 1547 – 3 September 1597), of Rycote, Oxfordshire, and of Yattendon and Notley in Berkshire, was an English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Culture, language and peoples

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

* ''English'', an Amish ter ...

soldier. The son of Henry Norris, 1st Baron Norreys

Henry Norris (or Norreys), 1st Baron Norreys ({{circa, 1525{{spaced ndash27 June 1601){{sfn, Fuidge, 1981 of Rycote in Oxfordshire, was an English people, English politician and diplomat, who belonged to an old Berkshire family, many members of wh ...

, he was a lifelong friend of Queen Elizabeth Queen Elizabeth, Queen Elisabeth or Elizabeth the Queen may refer to:

Queens regnant

* Elizabeth I (1533–1603; ), Queen of England and Ireland

* Elizabeth II (1926–2022; ), Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms

* Queen B ...

.

The most acclaimed English soldier of his day, Norreys participated in every Elizabethan theatre of war: in the Wars of Religion

A religious war or a war of religion, sometimes also known as a holy war (), is a war and conflict which is primarily caused or justified by differences in religion and beliefs. In the modern period, there are frequent debates over the extent ...

in France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

, in Flanders

Flanders ( or ; ) is the Dutch language, Dutch-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to culture, la ...

during the Eighty Years' War

The Eighty Years' War or Dutch Revolt (; 1566/1568–1648) was an armed conflict in the Habsburg Netherlands between disparate groups of rebels and the Spanish Empire, Spanish government. The Origins of the Eighty Years' War, causes of the w ...

of Dutch liberation from Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

, in the Anglo-Spanish War, and above all in the Tudor conquest of Ireland

Ireland was conquered by the Tudor monarchs of England in the 16th century. The Anglo-Normans had Anglo-Norman invasion of Ireland, conquered swathes of Ireland in the late 12th century, bringing it under Lordship of Ireland, English rule. In t ...

.

Early life

The eldest son of Henry Norreys by his marriage toMarjorie Williams

Marjorie Williams (January 13, 1958 – January 16, 2005) was an American writer, reporter, and columnist for '' Vanity Fair'' and ''The Washington Post'', writing about American society and profiling the American "political elite."

Life and ca ...

, Norreys was born at Yattendon Castle

Yattendon Castle was a fortified manor house located in the civil parish of Yattendon, in the Hundred (country subdivision), hundred of Faircross, in the England, English county of Berkshire.

History

The site upon which Yattendon castle stood ...

. His paternal grandfather had been executed after being found guilty of adultery with Queen Anne Boleyn

Anne Boleyn (; 1501 or 1507 – 19 May 1536) was List of English royal consorts, Queen of England from 1533 to 1536, as the Wives of Henry VIII, second wife of King Henry VIII. The circumstances of her marriage and execution, by beheading ...

, the mother of Queen Elizabeth Queen Elizabeth, Queen Elisabeth or Elizabeth the Queen may refer to:

Queens regnant

* Elizabeth I (1533–1603; ), Queen of England and Ireland

* Elizabeth II (1926–2022; ), Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms

* Queen B ...

. His maternal grandfather was John Williams, Lord Williams of Thame.

Norreys' great uncle had been a guardian of the young Elizabeth, who was well acquainted with the family. She had stayed at Yattendon Castle on her way to imprisonment at Woodstock

The Woodstock Music and Art Fair, commonly referred to as Woodstock, was a music festival held from August 15 to 18, 1969, on Max Yasgur's dairy farm in Bethel, New York, southwest of the town of Woodstock, New York, Woodstock. Billed as "a ...

. The future Queen was a great friend of Norreys' mother, whom she nicknamed "Black Crow" on account of her jet black hair. Norreys inherited his mother's hair colour so that he was known as "Black Jack" by his troops.

Norreys grew up with five brothers, several of whom were to serve alongside him during Elizabeth's wars. He may briefly have attended Magdalen College, Oxford

Magdalen College ( ) is a Colleges of the University of Oxford, constituent college of the University of Oxford. It was founded in 1458 by Bishop of Winchester William of Waynflete. It is one of the wealthiest Oxford colleges, as of 2022, and ...

.

In 1566, Norreys' father was posted as English ambassador to France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

, and in 1567, when he was about nineteen, Norreys and his elder brother William

William is a masculine given name of Germanic languages, Germanic origin. It became popular in England after the Norman Conquest, Norman conquest in 1066,All Things William"Meaning & Origin of the Name"/ref> and remained so throughout the Middle ...

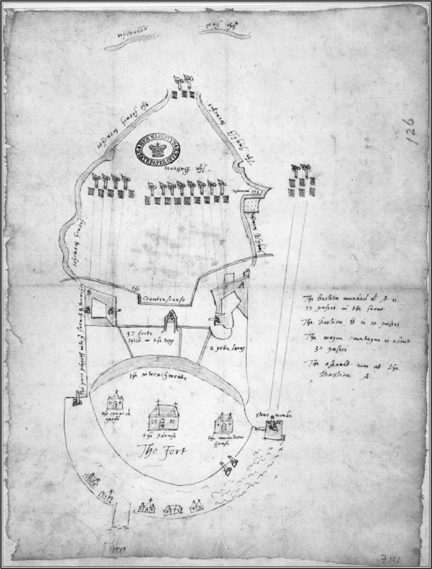

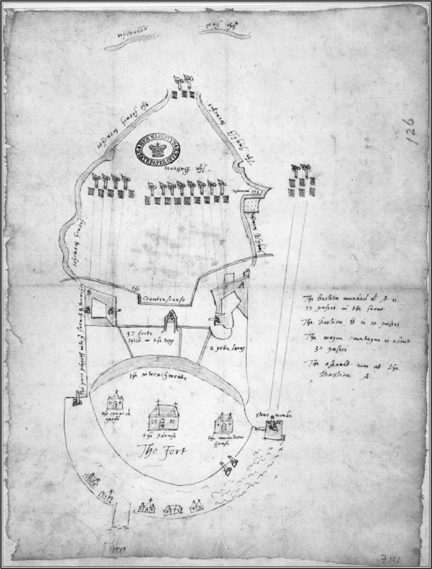

were present at the Battle of Saint Denis. They drew a map of the battle which formed part of their father's report to the Queen.

Early military career

When his father was recalled from France in January 1571, Norreys stayed behind and developed a friendship with the new ambassador,Francis Walsingham

Sir Francis Walsingham ( – 6 April 1590) was principal secretary to Queen Elizabeth I of England from 20 December 1573 until his death and is popularly remembered as her " spymaster".

Born to a well-connected family of gentry, Wa ...

. In 1571, Norreys served as a volunteer under Admiral Coligny, fighting on the Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , ; ) are a Religious denomination, religious group of French people, French Protestants who held to the Reformed (Calvinist) tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, ...

side during the French Wars of Religion

The French Wars of Religion were a series of civil wars between French Catholic Church, Catholics and Protestantism, Protestants (called Huguenots) from 1562 to 1598. Between two and four million people died from violence, famine or disease di ...

.

Two years later, Norreys served as a captain under Sir Walter Devereux, recently created first Earl of Essex

Earl of Essex is a title in the Peerage of England which was first created in the 12th century by King Stephen of England. The title has been recreated eight times from its original inception, beginning with a new first Earl upon each new cre ...

, who was attempting to establish a plantation

Plantations are farms specializing in cash crops, usually mainly planting a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. Plantations, centered on a plantation house, grow crops including cotton, cannabis, tob ...

in the Irish province of Ulster

Ulster (; or ; or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional or historic provinces of Ireland, Irish provinces. It is made up of nine Counties of Ireland, counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United Kingdom); t ...

as part of the Enterprise of Ulster

The Enterprise of Ulster was a programme launched in the 1570s where Queen Elizabeth I tried to get English entrepreneurs settled in areas of Ireland troubled by the activities of Ulster. Under this programme Nicholas Malby, Thomas Chatterton and ...

, from a base at Belfast

Belfast (, , , ; from ) is the capital city and principal port of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan and connected to the open sea through Belfast Lough and the North Channel (Great Britain and Ireland), North Channel ...

. He supported his elder brother William, Essex's chief lieutenant, who was in command of a troop of a hundred horse

The horse (''Equus ferus caballus'') is a domesticated, one-toed, hoofed mammal. It belongs to the taxonomic family Equidae and is one of two extant subspecies of ''Equus ferus''. The horse has evolved over the past 45 to 55 mi ...

which had been recruited by their father, then serving as Lord Lieutenant

A lord-lieutenant ( ) is the British monarch's personal representative in each lieutenancy area of the United Kingdom. Historically, each lieutenant was responsible for organising the county's militia. In 1871, the lieutenant's responsibility ov ...

of Berkshire. William was the first of Essex's commanders to be ambushed by Irish forces and when his horse was killed under him, near Massereene, east of Lough Neagh

Lough Neagh ( ; ) is a freshwater lake in Northern Ireland and is the largest lake on the island of Ireland and in the British Isles. It has a surface area of and is about long and wide. According to Northern Ireland Water, it supplies 4 ...

, John saved his brother from being slain. The Earl praised their actions in a letter to the queen.

While in Ulster Norreys took part in the arrest of Sir Brian McPhelim O'Neill

Sir Brian McPhelim Bacagh O'Neill (died 1574) was Chief of the Name of Clan O'Neill List of rulers of Clandeboye#Lords of Lower Clandeboye, 1556—1600, Lower Clandeboye, an Irish clan in north-eastern Ireland during the Tudor conquest of Ireland ...

, Chief of the Name

The Chief of the Name, or in older English usage Captain of his Nation, is the recognised head of a family or clan ( Irish and Scottish Gaelic: ''fine'') in Ireland and Scotland.

Ireland

There are instances where Norman lords of the time like ...

of Clan O'Neill and Lord

Lord is an appellation for a person or deity who has authority, control, or power (social and political), power over others, acting as a master, chief, or ruler. The appellation can also denote certain persons who hold a title of the Peerage o ...

of Lower Clandeboye, and what has become known as the Clandeboye massacre

The Clandeboye massacre in 1574 was a massacre of the O'Neills of Lower Clandeboye by the English forces of Walter Devereux, 1st Earl of Essex. It took place during an attempted English colonisation of Ulster as part of the Tudor conquest of I ...

. Lord Essex hosted The O'Neill and his clansmen at a banquet held at Belfast in October 1574. The O'Neill reciprocated by hosting Essex and his followers at a feast of his own, which lasted for three days; but on the third day, Norreys and his men slaughtered over 200 of O'Neill's unarmed clansmen. Essex took Sir Brian, his wife and others to Dublin where they were later executed.

When Lord Essex entered County Antrim

County Antrim (named after the town of Antrim, County Antrim, Antrim, ) is one of the six counties of Northern Ireland, located within the historic Provinces of Ireland, province of Ulster. Adjoined to the north-east shore of Lough Neagh, the c ...

, it was to Rathlin Island

Rathlin Island (, ; Local Irish dialect: ''Reachraidh'', ; Scots: ''Racherie'') is an island and civil parish off the coast of County Antrim (of which it is part) in Northern Ireland. It is Northern Ireland's northernmost point. As of the 2021 ...

that the Scots Highlanders of Clan MacDonald of Dunnyveg

Clan MacDonald of Dunnyveg, also known as Clan Donald South, ''Clan Iain Mor, Clan MacDonald of Islay and Kintyre, MacDonalds of the Glens (Antrim)'' and sometimes referred to as ''MacDonnells'', is a Scottish clan and a branch of Clan Donald. T ...

led by Somhairle Buidhe MacDonnell sent their wives and children, their aged and sick, for safety. Lord Essex, knowing that the Scots refugees were still on the island, sent orders to Norreys, who was in command at Carrickfergus

Carrickfergus ( , meaning " Fergus' rock") is a large town in County Antrim, Northern Ireland. It sits on the north shore of Belfast Lough, from Belfast. The town had a population of 28,141 at the 2021 census. It is County Antrim's oldest t ...

, to take a company of soldiers with him, cross over to Rathlin Island, and kill everyone he could find. Norreys had brought cannon with him, so that the weak defences were speedily destroyed after a fierce assault in which several of the garrison were killed. The Scots were obliged to surrender with no quarter

No quarter, during War, military conflict or piracy, implies that combatants would not be taken Prisoner of war, prisoner, but executed. Since the Hague Convention of 1899, it is considered a war crime; it is also prohibited in customary interna ...

and all fell victim to the Rathlin Island Massacre

The Rathlin Island massacre took place on Rathlin Island, off the coast of Ireland on 26 July 1575, when more than 600 Scots and Irish were killed.

Sanctuary attacked

Rathlin Island was used as a sanctuary because of its natural defences a ...

, except the chief

Chief may refer to:

Title or rank

Military and law enforcement

* Chief master sergeant, the ninth, and highest, enlisted rank in the U.S. Air Force and U.S. Space Force

* Chief of police, the head of a police department

* Chief of the boat ...

and his family, who were reserved for ransom. The death toll was two hundred. Then it was discovered that several hundred more, chiefly women and children, had been hidden in the caves about the shore, all of them were massacred, too.

A fort was erected on the island, but was evacuated by Norreys, and he was recalled with his troops to Dublin

Dublin is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. Situated on Dublin Bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, and is bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, pa ...

within 3 months, when it was clear that the colonisation would fail. William, his brother, died of fever in Newry, Christmas Day 1579 on returning to Ireland from England.

In 1577, Norreys led a force of English volunteers to the

In 1577, Norreys led a force of English volunteers to the Low Countries

The Low Countries (; ), historically also known as the Netherlands (), is a coastal lowland region in Northwestern Europe forming the lower Drainage basin, basin of the Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta and consisting today of the three modern "Bene ...

, where he fought for the States General, then in revolt against the rule of the Spanish King Philip II at the beginning of the Eighty Years' War

The Eighty Years' War or Dutch Revolt (; 1566/1568–1648) was an armed conflict in the Habsburg Netherlands between disparate groups of rebels and the Spanish Empire, Spanish government. The Origins of the Eighty Years' War, causes of the w ...

. At the battle of Rijmenam (2 August 1578), his force helped defeat the Spanish under the command of John of Austria

John of Austria (, ; 24 February 1547 – 1 October 1578) was the illegitimate son of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor. Charles V recognized him in a codicil to his will. John became a military leader in the service of his half-brother, King Phi ...

(''Don Juan de Austria''), the king's brother; Norreys had three horses shot from under him.

Throughout 1579, he co-operated with the French army under François de la Noue

François de la Noue (1531 – August 4, 1591), called Bras-de-Fer (Iron Arm), was one of the Huguenot captains of the 16th century. He was born near Nantes in 1531, of an ancient Breton family.

He served in Italy under Marshal Brissac, and in th ...

, and was put in charge of all English troops, about 150-foot and 450 mounted. He took part in the battle of Borgerhout

The Battle of Borgerhout was a battle during the Eighty Years' War, of the Spanish Army of Flanders led by Alexander Farnese, Prince of Parma, upon a fortified camp at the village of Borgerhout, near Antwerp, where several thousand French, En ...

, where the Spanish army under Alexander Farnese was victorious. Later, he went on to match the Spanish in operations around Meppel

Meppel (; Drents: ''Möppelt'') is a city and municipality in the Northeastern Netherlands. It constitutes the southwestern part of the province of Drenthe. Meppel is the smallest municipality in Drenthe, with a total area of about . As of 1 July ...

and on 9 April 1580, his troops conquered Mechelen

Mechelen (; ; historically known as ''Mechlin'' in EnglishMechelen has been known in English as ''Mechlin'', from where the adjective ''Mechlinian'' is derived. This name may still be used, especially in a traditional or historical context. T ...

and brutally sacked the city in what has become known as the ''English Fury at Mechelen

The English Fury at Mechelen or the Capture of Mechelen was an event in the Eighty Years' War and the Anglo–Spanish War on April 9, 1580. The city of Mechelen (known as ''Malines'' in French and historically in English) was conquered by Calvini ...

''. During the 16th century

The 16th century began with the Julian calendar, Julian year 1501 (represented by the Roman numerals MDI) and ended with either the Julian or the Gregorian calendar, Gregorian year 1600 (MDC), depending on the reckoning used (the Gregorian calend ...

, the usual laws and customs of war

The law of war is a component of international law that regulates the conditions for initiating war (''jus ad bellum'') and the conduct of hostilities (''jus in bello''). Laws of war define sovereignty and nationhood, states and territories, ...

permitted up to three days of sacking after the fall of a city, while the English mercenaries under Norreys' command continued looting and pillaging the city for nearly an entire month. Furthermore, the sacking of Mechelen by Norreys' troops was far more brutal and systematic that the infamous "Spanish fury" that had hit the same city in 1572.

On account of these successes, essentially as a mercenary, he boosted the morale in the Protestant armies and became famous in England. The morale of his own troops depended on prompt and regular payment by the States General for their campaign, and Norreys gained a reputation for forceful leadership.

In February 1581, he defeated the Count of Rennenburg by relieving Steenwijk under siege and in July inflicted a further defeat at Kollum near Groningen

Groningen ( , ; ; or ) is the capital city and main municipality of Groningen (province), Groningen province in the Netherlands. Dubbed the "capital of the north", Groningen is the largest place as well as the economic and cultural centre of ...

. In September 1581, however, he was dealt a serious defeat by a Spanish army under Colonel Francisco Verdugo

Francisco Verdugo (1537–1595), Spanish military commander in the Dutch Revolt, became ''Maestre de Campo General,'' in the Spanish Netherlands. He was also the last Spanish Stadtholder of Friesland, Groningen, Drenthe and Overijssel between 1581 ...

at the Battle of Noordhorn

The Battle of Noordhorn, fought on 30 September 1581, was a pitched battle of the Dutch Revolt, fought between a Spanish army commanded by Colonel Francisco Verdugo – consisting of Walloon people, Walloon, German people, German, Spanish peopl ...

, near Groningen

Groningen ( , ; ; or ) is the capital city and main municipality of Groningen (province), Groningen province in the Netherlands. Dubbed the "capital of the north", Groningen is the largest place as well as the economic and cultural centre of ...

. The following month Norris later checked Verdugo by repelling him at Niezijl. Later in the year, he along with the Count of Hohenlohe helped to relieve the city of Lochem

Lochem () is a city and municipality in the province of Gelderland in the Eastern Netherlands. In 2005, it merged with the municipality of Gorssel, retaining the name of Lochem. As of 2019, it had a population of 33,590.

Population centres

Th ...

which had been under siege by Verdugo.

After more campaigns in Flanders in support of François, Duke of Anjou

''Monsieur'' François, Duke of Anjou and Alençon (; 18 March 1555 – 10 June 1584) was the youngest son of King Henry II of France and Catherine de' Medici.

Early years

He was scarred by smallpox at age eight, and his pitted face and s ...

, Norreys was sent back to the Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, commonly referred to in historiography as the Dutch Republic, was a confederation that existed from 1579 until the Batavian Revolution in 1795. It was a predecessor state of the present-day Netherlands ...

as an unofficial ambassador of Elizabeth I.

In 1584, he returned to England to encourage an English declaration of war on Spain in order to support the States General's war against the House of Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (; ), also known as the House of Austria, was one of the most powerful Dynasty, dynasties in the history of Europe and Western civilization. They were best known for their inbreeding and for ruling vast realms throughout ...

.

Return to Ireland

In March 1584, Norreys departed the Low Countries and was sent toIreland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

in the following July, where he was appointed Lord President of Munster

The post of Lord President of Munster was the most important office in the English government of the Irish province of Munster from its introduction in the Elizabethan era for a century, to 1672, a period including the Desmond Rebellions in Munste ...

(at this time, his brother Edward was stationed there). Norris urged the Plantation of Munster

Plantations in 16th- and 17th-century Ireland () involved the confiscation of Irish-owned land by the English Crown and the colonisation of this land with settlers from Great Britain.

The main plantations took place from the 1550s to the 162 ...

with English Puritans (an aim adopted in the following years), but the situation proved so unbearably miserable that many of his soldiers deserted him for the Low Countries.

In September 1584 Norreys accompanied the Lord Deputy of Ireland

The Lord Deputy was the representative of the monarch and head of the Irish executive (government), executive under English rule, during the Lordship of Ireland and then the Kingdom of Ireland. He deputised prior to 1523 for the Viceroy of Ireland ...

, Sir John Perrot

Sir John Perrot (7 November 1528 – 3 November 1592) was a member of the Welsh gentry who served as Lord Deputy of Ireland under Queen Elizabeth I of England during the Tudor conquest of Ireland. It was formerly speculated that he was an ille ...

, and the earl of Ormonde into Ulster

Ulster (; or ; or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional or historic provinces of Ireland, Irish provinces. It is made up of nine Counties of Ireland, counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United Kingdom); t ...

. The purpose, once again, was to dislodge the Highlander Scots of Clan MacDonald of Dunnyveg

Clan MacDonald of Dunnyveg, also known as Clan Donald South, ''Clan Iain Mor, Clan MacDonald of Islay and Kintyre, MacDonalds of the Glens (Antrim)'' and sometimes referred to as ''MacDonnells'', is a Scottish clan and a branch of Clan Donald. T ...

, who, led by Somhairle Buidhe MacDonnell, had migrated into both the Route The Route may refer to:

* The Route (film), a Ugandan film

* The Route (TV series), a Spanish television series

* Route, County Antrim a medieval territory in Gaelic Ireland

See also

* Route (disambiguation)

Route or routes may refer to:

* A ...

and the Glens of Antrim

The Glens of Antrim ( Irish: ''Glinnte Aontroma''), known locally as simply The Glens, is a region of County Antrim, Northern Ireland. It comprises nine glens, that radiate from the Antrim Plateau to the coast. The Glens are an area of outstand ...

. Norreys helped rustle fifty thousand head of cattle from the woods of Glenconkyne in order to starve the Highlanders of their means of sustenance. The campaign was unsuccessful, as what is now called the Clan MacDonald of Antrim simply regrouped in Kintyre

Kintyre (, ) is a peninsula in western Scotland, in the southwest of Argyll and Bute. The peninsula stretches about , from the Mull of Kintyre in the south to East Loch Tarbert, Argyll, East and West Loch Tarbert, Argyll, West Loch Tarbert in t ...

before crossing back to Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

after the lord deputy had withdrawn south. Norreys returned to Munster

Munster ( or ) is the largest of the four provinces of Ireland, located in the south west of the island. In early Ireland, the Kingdom of Munster was one of the kingdoms of Gaelic Ireland ruled by a "king of over-kings" (). Following the Nor ...

, where he become unintentionally important to the history and martyrology of the Catholic Church in Ireland

The Catholic Church in Ireland, or Irish Catholic Church, is part of the worldwide Catholic Church in communion with the Holy See. With 3.5 million members (in the Republic of Ireland), it is the largest Christian church in Ireland. In ...

.

In April 1585, the jailer at Clonmel

Clonmel () is the county town and largest settlement of County Tipperary, Republic of Ireland, Ireland. The town is noted in Irish history for its resistance to the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland, Cromwellian army which sacked the towns of Dro ...

, County Tipperary

County Tipperary () is a Counties of Ireland, county in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Munster and the Southern Region, Ireland, Southern Region. The county is named after the town of Tipperary (tow ...

was bribed by Victor White, a leading townsman, to release imprisoned Roman Catholic priest

The priesthood is the office of the ministers of religion, who have been commissioned ("ordained") with the holy orders of the Catholic Church. Technically, bishops are a priestly order as well; however, in common English usage ''priest'' re ...

Fr. Muiris Mac Ionrachtaigh

Muiris Mac Ionrachtaigh, anglicised as Maurice MacKenraghty (died 30 April 1585), was an Irish Roman Catholic priest who was put to death, officially for high treason, but in reality as part of the religious persecution of the Catholic Church in ...

for one night to say Mass

Mass is an Intrinsic and extrinsic properties, intrinsic property of a physical body, body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the physical quantity, quantity of matter in a body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physi ...

and administer Holy Communion inside White's house on Easter Sunday

Easter, also called Pascha (Aramaic: פַּסְחָא , ''paskha''; Greek language, Greek: πάσχα, ''páskha'') or Resurrection Sunday, is a Christian festival and cultural holiday commemorating the resurrection of Jesus from the dead, de ...

(11 April 1585). Permission was granted and Fr. MacKenraghty spent the whole night hearing Confessions.

The jailer, however, had secretly tipped off Lord President of Munster

The post of Lord President of Munster was the most important office in the English government of the Irish province of Munster from its introduction in the Elizabethan era for a century, to 1672, a period including the Desmond Rebellions in Munste ...

Sir John Norreys, who had just arrived at Clonmel. According to historian James Coombes, "Norris (sic

The Latin adverb ''sic'' (; ''thus'', ''so'', and ''in this manner'') inserted after a quotation indicates that the quoted matter has been transcribed or translated as found in the source text, including erroneous, archaic, or unusual spelling ...

) arranged to have White's house surrounded by soldiers and raided. The raiding party entered it shortly before Mass was due to begin and naturally caused great panic. Some people tried to hide in the basement; others jumped through the windows; one woman broke her arm in an attempt to escape. The priest hid in a heap of straw and was wounded in the thigh by the probing sword of a soldier. Despite the pain, he remained silent and later escaped. The soldiers dismantled the altar and seized the sacred vessels."

Meanwhile, Victor White was arrested and threatened with execution unless he revealed where Fr. Muiris Mac Ionrachtaigh could be arrested. Upon hearing of the situation, Fr. Mac Ionrachtaigh sent an emissary to speak to White. Despite White's pleas that he preferred to lose his own life rather than have Fr. Mac Ionrachtaigh come to harm, the priest insisted upon giving himself up and was again thrown into Clonmel Gaol.

The trial of Fr. Mac Ionrachtaigh by martial law

Martial law is the replacement of civilian government by military rule and the suspension of civilian legal processes for military powers. Martial law can continue for a specified amount of time, or indefinitely, and standard civil liberties ...

involved merely an interrogation before Sir John Norreys and his assistants. Pardon and high preferment were offered for conforming to the Church of Ireland

The Church of Ireland (, ; , ) is a Christian church in Ireland, and an autonomy, autonomous province of the Anglican Communion. It is organised on an all-Ireland basis and is the Christianity in Ireland, second-largest Christian church on the ...

and taking the Oath of Supremacy

The Oath of Supremacy required any person taking public or church office in the Kingdom of England, or in its subordinate Kingdom of Ireland, to swear allegiance to the monarch as Supreme Governor of the Church. Failure to do so was to be trea ...

to accept the subservience of the Church to the State. Fr. Mac Ionrachtaigh, however, resolutely maintained the Roman Catholic faith and the Petrine Primacy

The primacy of Peter, also known as Petrine primacy (from the ), is the position of preeminence that is attributed to Saint Peter, Peter among the Twelve Apostles.

Primacy of Peter among the Apostles

The ''Evangelical Dictionary of Theology' ...

and was accordingly condemned by Sir John Norreys, "after much invective", to death for high treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its d ...

. After passing sentence, however, Norreys offered Fr. Mac Ionrachtaigh a full pardon in return for taking the Oath of Supremacy and naming those local Catholics who had attended his Mass or secretly received the Sacraments from him. A Protestant minister also attempted to convert the priest by engaging him in debate. All was in vain, and Fr. Mac Ionrachtaigh refused to conform. According to historian James Coombes, "Especially in trials by martial law, there was no fixed procedure or sequence of events. What is made perfectly clear is that Maurice MacKenraghty was condemned to death because he would not take the Oath of Supremacy."

On 30 April 1585, Fr. Muiris Mac Ionrachtaigh was dragged at the tail of a horse to be executed as a traitor. According to Bishop David Rothe

David Rothe (1573 – 20 April 1650) was a Roman Catholic Bishop of Ossory.

Life

David Rothe was born in 1573 in High Street Kilkenny. His maternal grandmother, Ellen Butler, was first cousin to Pierce the Red, Eighth Earl of Ormond.Ronan, Myle ...

, "When he came to the place of execution, he turned to the people and addressed them some pious words as far as time allowed; in the end he asked all Catholics to pray for him and he gave them his blessing."

He was hanged, cut down while still alive, and then executed by beheading

Decapitation is the total separation of the head from the body. Such an injury is invariably fatal to humans and all vertebrate animals, since it deprives the brain of oxygenated blood by way of severing through the jugular vein and common ...

. His head was spiked and displayed in the marketplace along with the four quarters of his torso.

Norreys was then summoned to Dublin Castle

Dublin Castle () is a major Government of Ireland, Irish government complex, conference centre, and tourist attraction. It is located off Dame Street in central Dublin.

It is a former motte-and-bailey castle and was chosen for its position at ...

in 1585 for the opening of Parliament. He sat as a Member of Parliament (MP) for County Cork

County Cork () is the largest and the southernmost Counties of Ireland, county of Republic of Ireland, Ireland, named after the city of Cork (city), Cork, the state's second-largest city. It is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Munster ...

and was forcefully eloquent on measures to confirm the Queen's authority over the whole country. He also complained that he was prevented from launching a fresh campaign against the rising of the Irish clan

Irish clans are traditional kinship groups sharing a common surname and heritage and existing in a lineage-based society, originating prior to the 17th century. A clan (or in Irish, plural ) included the chief and his patrilineal relatives; howe ...

s in Ulster

Ulster (; or ; or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional or historic provinces of Ireland, Irish provinces. It is made up of nine Counties of Ireland, counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United Kingdom); t ...

.

Anglo-Spanish War

Upon news of the siege of

Upon news of the siege of Antwerp

Antwerp (; ; ) is a City status in Belgium, city and a Municipalities of Belgium, municipality in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It is the capital and largest city of Antwerp Province, and the third-largest city in Belgium by area at , after ...

, Norreys urged support for the Dutch Protestants and, transferring the presidency of Munster to his brother, Thomas, he rushed to London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

in May 1585 to prepare for a campaign in the Low Countries. In August, he commanded an English army of 4400 men which Elizabeth had sent to support the States General against the Spaniards, in accordance with the Treaty of Nonsuch

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between sovereign states and/or international organizations that is governed by international law. A treaty may also be known as an international agreement, protocol, covenant, conventio ...

. He gallantly stormed a fort near Arnhem

Arnhem ( ; ; Central Dutch dialects, Ernems: ''Èrnem'') is a Cities of the Netherlands, city and List of municipalities of the Netherlands, municipality situated in the eastern part of the Netherlands, near the German border. It is the capita ...

; the queen, however, was unhappy at this aggression. Still, his army of untried English foot did repulse the Duke of Parma

The Duke of Parma and Piacenza () was the ruler of the Duchy of Parma and Piacenza, a List of historic states of Italy, historical state of Northern Italy. It was created by Pope Paul III (Alessandro Farnese) for his son Pier Luigi Farnese, Du ...

in a day-long fight at Aarschot

Aarschot () is a city and municipality in the province of Flemish Brabant, in Flanders, Belgium. The municipality comprises the city of Aarschot proper and the towns of Gelrode, Langdorp and Rillaar. On 1 January 2019, Aarschot had a total popu ...

and remained a threat, until supplies of clothing, food and money ran out. His men suffered an alarming mortality rate without support from home, but the aura of invincibility attaching to the Spanish troops had been dispelled, and Elizabeth finally made a full commitment of her forces to the States General.

In December 1585, the Earl of Leicester

Earl of Leicester is a title that has been created seven times. The first title was granted during the 12th century in the Peerage of England. The current title is in the Peerage of the United Kingdom and was created in 1837.

History

Earl ...

arrived with a new army and accepted the position of Governor-General

Governor-general (plural governors-general), or governor general (plural governors general), is the title of an official, most prominently associated with the British Empire. In the context of the governors-general and former British colonies, ...

of the Low Countries, as England went into open alliance. During an attack on Parma, Norreys received a pike wound in the breast, then managed to break through to relieve Grave, the last barrier to the Spanish advance into the north; Leicester knighted

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of a knighthood by a head of state (including the pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church, or the country, especially in a military capacity.

The concept of a knighthood ...

him for this victory during a great feast at Utrecht

Utrecht ( ; ; ) is the List of cities in the Netherlands by province, fourth-largest city of the Netherlands, as well as the capital and the most populous city of the Provinces of the Netherlands, province of Utrecht (province), Utrecht. The ...

on St George's Day

Saint George's Day is the Calendar of saints, feast day of Saint George, celebrated by Christian churches, countries, regions, and cities of which he is the Patronages of Saint George, patron saint, including Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bu ...

, along with his brothers Edward and Henry. But the Spanish were soon admitted to Grave by treachery, and Norreys advised against Leicester's order to have the traitor beheaded, apparently because he was in love with the traitor's aunt.

The two commanders quarrelled for the rest of the campaign, which turned out a failure. Leicester complained that Norreys was like the Earl of Sussex

Earl of Sussex is a title that has been created several times in the Peerages of England, Great Britain, and the United Kingdom. The early Earls of Arundel (up to 1243) were often also called Earls of Sussex.

The fifth creation came in the Pee ...

in his animosity. His main grievance, though, was the corruption of Norreys' uncle, the campaign's treasurer. Leicester's urgings to recall both Norreys and his uncle, were resisted by the Queen. Norreys continued his good service and was ordered by Leicester to protect Utrecht

Utrecht ( ; ; ) is the List of cities in the Netherlands by province, fourth-largest city of the Netherlands, as well as the capital and the most populous city of the Provinces of the Netherlands, province of Utrecht (province), Utrecht. The ...

in August 1586. The operation did not go smoothly because Leicester had omitted to put Sir William Stanley under Norreys' command. Norreys joined with Stanley in September in the Battle of Zutphen

The Battle of Zutphen was fought on 22 September 1586, near the village of Warnsveld and the town of Zutphen, the Netherlands, during the Eighty Years' War. It was fought between the forces of the United Provinces of the Netherlands, aided ...

, in which Sir Philip Sidney

Sir Philip Sidney (30 November 1554 – 17 October 1586) was an English poet, courtier, scholar and soldier who is remembered as one of the most prominent figures of the Elizabethan era, Elizabethan age.

His works include a sonnet sequence, ' ...

- commanding officer over Norreys' brother, Edward, who was lieutenant in the governorship of Flushing

Flushing may refer to:

Places

Netherlands

* Flushing, Netherlands, an English name for the city of Vlissingen, Netherlands

United Kingdom

* Flushing, Cornwall, a village in Cornwall, England

* The Flushing, a building in Suffolk, England ...

- was fatally wounded. At an officers' supper, Edward took offence at some remarks by Sir William Pelham, marshal of the army, which he thought reflected on the character of his older brother, and an argument with the Dutch host flared up, with Leicester having to mediate between the younger Norreys and his host to prevent a duel.

By the autumn of 1586 Leicester seems to have relented and was full of praise for Norreys, while at the same time the States General held golden opinions of him. But he was recalled in October, and the queen received him with disdain, apparently owing to his enmity for Leicester; within a year he had returned to the Low Countries, where the new commander, Willoughby, recognised that Norreys would be better for the job, with the comment, "''If I were sufficient, Norreys were superfluous''". Willoughby resented having Norris around and observed that he was, "''more happy than a caesar''".

At the beginning of 1588, Norreys returned to England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

, where he was presented with the degree of Master of Arts at the University of Oxford

The University of Oxford is a collegiate university, collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the List of oldest un ...

.

Later in the year, when the Spanish Armada

The Spanish Armada (often known as Invincible Armada, or the Enterprise of England, ) was a Spanish fleet that sailed from Lisbon in late May 1588, commanded by Alonso de Guzmán, Duke of Medina Sidonia, an aristocrat without previous naval ...

was expected, he was, under Leicester, marshal of the camp at West Tilbury

West Tilbury is a village and former civil parish in the Thurrock district, in the ceremonial county of Essex, England. It is on the top of and on the sides of a tall river terrace overlooking the River Thames. Part of the modern town of Tilbur ...

when Elizabeth delivered the Speech to the Troops at Tilbury

The Speech to the Troops at Tilbury was delivered on 9 August Old Style (19 August New Style) 1588 by Queen Elizabeth I of England to the land forces earlier assembled at Tilbury in Essex in preparation for repelling the expected invasion by th ...

. He inspected the fortification of Dover, and, in October, returned to the Low Countries as ambassador to the States-General. He oversaw a troop withdrawal in preparation for an expedition to Portugal designed to drive home the English advantage following the defeat of the Spanish Armada

The Spanish Armada (often known as Invincible Armada, or the Enterprise of England, ) was a Spanish fleet that sailed from Lisbon in late May 1588, commanded by Alonso de Guzmán, Duke of Medina Sidonia, an aristocrat without previous naval ...

, when the enemy's fleet was at its weakest.

On Wednesday 17 April 1589 (although another source gives the date of departure as 18 April), Norreys set out with Drake at the head of a 23,000 strong expeditionary force (which included 19,000 troops and is now termed the

On Wednesday 17 April 1589 (although another source gives the date of departure as 18 April), Norreys set out with Drake at the head of a 23,000 strong expeditionary force (which included 19,000 troops and is now termed the English Armada

The English Armada (), also known as the Counter Armada, Drake–Norris Expedition, Portugal Expedition, was an attack fleet sent against Spain by Queen Elizabeth I of England that sailed on 28 April 1589 during the undeclared Anglo-Spanish W ...

) on a mission to destroy the shipping on the coasts of Spain and to place the pretender to the crown of Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic, is a country on the Iberian Peninsula in Southwestern Europe. Featuring Cabo da Roca, the westernmost point in continental Europe, Portugal borders Spain to its north and east, with which it share ...

, the Prior of Crato, on the throne. Corunna was surprised, and the lower part of the town burned as Norreys' troops beat off a force of 8,000. Edward was badly wounded in an assault on O Burgo, and his life was only saved by the gallantry of his elder brother. Norreys then attacked Lisbon, but the enemy refused to engage with him, leaving him no option but to put back to sea. Running low on supplies and with his task force reduced by disease and death, Norreys abandoned the secondary objective of attacking the Azores, and the expeditionary force set out to return to England. By the start of July 1589 (Wingfield gives a date of 5 July) the taskforce had all arrived home, some landing back at Plymouth, some at Portsmouth and others London, having achieved little. This "English Armada

The English Armada (), also known as the Counter Armada, Drake–Norris Expedition, Portugal Expedition, was an attack fleet sent against Spain by Queen Elizabeth I of England that sailed on 28 April 1589 during the undeclared Anglo-Spanish W ...

", was thus an unsuccessful attempt to press home the defeat of the Spanish Armada

The Spanish Armada (often known as Invincible Armada, or the Enterprise of England, ) was a Spanish fleet that sailed from Lisbon in late May 1588, commanded by Alonso de Guzmán, Duke of Medina Sidonia, an aristocrat without previous naval ...

and bring the war to the ports of Spain's northern coast and to Lisbon

Lisbon ( ; ) is the capital and largest city of Portugal, with an estimated population of 567,131, as of 2023, within its administrative limits and 3,028,000 within the Lisbon Metropolitan Area, metropolis, as of 2025. Lisbon is mainlan ...

.

From 1591 to 1594, Norreys aided King Henri IV

Henry IV (; 13 December 1553 – 14 May 1610), also known by the epithets Good King Henry (''le Bon Roi Henri'') or Henry the Great (''Henri le Grand''), was King of Navarre (as Henry III) from 1572 and King of France from 1589 to 16 ...

in his struggle with the Catholic League, fighting for the Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , ; ) are a Religious denomination, religious group of French people, French Protestants who held to the Reformed (Calvinist) tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, ...

cause in Brittany

Brittany ( ) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the north-west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica in Roman Gaul. It became an Kingdom of Brittany, independent kingdom and then a Duch ...

at the head of 3000 troops. He took Guingamp

Guingamp (; ) is a commune in the Côtes-d'Armor department in Brittany in northwestern France. With a population of 7,115 as of 2020, Guingamp is one of the smallest towns in Europe to have a top-tier professional football team: En Avant Guin ...

and defeated the Breton Catholic League and their Spanish allies at Château-Laudran. Some of his troops transferred to the Earl of Essex's force in Normandy, and Norreys' campaign proved so indecisive that he left for England in February 1592 and did not return to the Duchy of Brittany

The Duchy of Brittany (, ; ) was a medieval feudal state that existed between approximately 939 and 1547. Its territory covered the northwestern peninsula of France, bordered by the Bay of Biscay to the west, and the English Channel to the north. ...

until September 1594.

He seized the town of Morlaix

Morlaix (; , ) is a commune in the Finistère department of Brittany in northwestern France. It is a sub-prefecture of the department.

History

The Battle of Morlaix, part of the Hundred Years' War, was fought near the town on 30 Septembe ...

after he had outmanoeuvred the Duke of Mercour and Juan del Águila

Juan Del Águila (d'Aguila) y Arellano (Ávila, Spain, Ávila, 1545 – A Coruña, August 1602) was a Habsburg Spain, Spanish general. He commanded the Spanish expeditionary Tercio troops in Kingdom of Sicily, Sicily then in Brittany (1584� ...

. Afterwards, he was part of the force that besieged and brutally assaulted and captured Fort Crozon outside Brest, defended by 400 Spanish troops, as well as foiling the relief army under Águila. This was his most notable military success, despite heavy casualties and suffering wounds himself. His youngest brother, Maximilian, was slain while serving under him in this year. Having fallen afoul of his French Protestant colleagues, Norreys returned from Brest at the end of 1594.

Return to Ulster

Norreys was selected as the military commander under the new lord deputy of Ireland, Sir William Russell, in April 1595. The waspish Russell had been governor of Flushing, but the two men were on bad terms. SirRobert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex

Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex (; 10 November 1565 – 25 February 1601) was an English nobleman and a favourite of Queen Elizabeth I. Politically ambitious, he was placed under house arrest following a poor campaign in Ireland during th ...

had wanted his men placed as Russell's subordinates, but Norreys rejected this and was issued with a special patent that made him independent of the lord deputy's authority in Ulster. It was expected that the terror of the reputation he had gained in combatting the Spanish would be sufficient to cause the rebellion to collapse.

Norreys arrived at Waterford

Waterford ( ) is a City status in Ireland, city in County Waterford in the South-East Region, Ireland, south-east of Ireland. It is located within the Provinces of Ireland, province of Munster. The city is situated at the head of Waterford H ...

in May 1595, but was struck with malaria

Malaria is a Mosquito-borne disease, mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects vertebrates and ''Anopheles'' mosquitoes. Human malaria causes Signs and symptoms, symptoms that typically include fever, Fatigue (medical), fatigue, vomitin ...

on disembarking. In June, he set out from Dublin with 2,900 men and artillery, with Russell trailing him through Dundalk. After flourishing his letters patent at Drogheda

Drogheda ( , ; , meaning "bridge at the ford") is an industrial and port town in County Louth on the east coast of Ireland, north of Dublin. It is located on the Dublin–Belfast corridor on the east coast of Ireland, mostly in County Louth ...

upon the proclamation of Aodh Mór Ó Néill

Hugh O'Neill, Earl of Tyrone (; – 20 July 1616) was an Irish lord and key figure of the Nine Years' War (Ireland), Nine Years' War. Known as the "Great Earl", he led the confederacy of Irish lords against the Crown, the English Crown in r ...

, Chief of the Name

The Chief of the Name, or in older English usage Captain of his Nation, is the recognised head of a family or clan ( Irish and Scottish Gaelic: ''fine'') in Ireland and Scotland.

Ireland

There are instances where Norman lords of the time like ...

of Clan O'Neill and Lord

Lord is an appellation for a person or deity who has authority, control, or power (social and political), power over others, acting as a master, chief, or ruler. The appellation can also denote certain persons who hold a title of the Peerage o ...

of Tír Eoghain

Tír Eoghain (), also known as Tyrone, was a kingdom and later earldom of Gaelic Ireland, comprising parts of present-day County Tyrone, County Armagh, County Londonderry and County Donegal (Raphoe). The kingdom represented the core homeland of ...

, as guilty of high treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its d ...

, Norreys made his headquarters at Newry

Newry (; ) is a City status in Ireland, city in Northern Ireland, standing on the Newry River, Clanrye river in counties County Down, Down and County Armagh, Armagh. It is near Republic of Ireland–United Kingdom border, the border with the ...

and fortified Armagh

Armagh ( ; , , " Macha's height") is a city and the county town of County Armagh, in Northern Ireland, as well as a civil parish. It is the ecclesiastical capital of Ireland – the seat of the Archbishops of Armagh, the Primates of All ...

cathedral. On learning that artillery was stored at Newry

Newry (; ) is a City status in Ireland, city in Northern Ireland, standing on the Newry River, Clanrye river in counties County Down, Down and County Armagh, Armagh. It is near Republic of Ireland–United Kingdom border, the border with the ...

, O'Neill dismantled his stronghold at Dungannon castle and entered the field. Norreys camped his troops along the River Blackwater, while Clan O'Neill roamed the far bank; a ford was secured but no crossing was attempted because there was no harvest to destroy and a raid within enemy territory would have been futile.

So long as Russell was with the army, Norreys refused to assume full responsibility, which prompted the lord deputy to return to Dublin in July 1595, leaving his commander a free hand in the conquest of Ulster. But already, Norreys had misgivings: he thought the task impossible without reinforcements and accused Russell of thwarting him and of concealing from the London government the imperfections of the army. He informed the queen's secretary, Sir William Cecil, that the Ulster Clans were far superior in strength, arms and munitions to any he had previously encountered, and that the English needed commensurate reinforcement.

So quickly did the situation deteriorate, that Norreys declined to risk marching his troops 10 miles through the Moyry Pass

The Moyry Pass is a geographical feature on the border between the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland. It is a mountain pass running along Slieve Gullion between Newry and Dundalk. It is also known as the Gap of the North.Spring p.105

The pa ...

, from Newry to Dundalk, choosing instead to move them by sea; but in a blow to his reputation, Russell confounded him later that summer by brazenly marching up to the Blackwater with little difficulty. More troops were shipped into Ireland, and the companies were ordered to take on 20 Irishmen apiece, which was admitted to be risky. But Norreys still complained that his units were made up of poor old ploughmen and rogues.

O'Neill presented Norreys with a written submission, but this was rejected on the advice of the Dublin council, owing to Aodh Mór O'Neill's demand for recognition of his supremacy over the Irish clan

Irish clans are traditional kinship groups sharing a common surname and heritage and existing in a lineage-based society, originating prior to the 17th century. A clan (or in Irish, plural ) included the chief and his patrilineal relatives; howe ...

s of Ulster. Norris could not draw his opponent out and decided to winter at Armagh, which he revictualled in September 1595. But a second trip was necessary because of a lack of draught horses, and on the return march, while fortifying a pass between Newry and Armagh, Norreys was wounded in the arm and side (and his brother too) at the Battle of Mullabrack near modern-day Markethill, where the Irish cavalry was noted to be more enterprising than Norreys had been expected. (Norreys had previously alleged that Irish cavalrymen were fit only to catch cows.) The rebels had also attacked in the Moyry pass upon the army's first arrival but had been repelled.

With approval from London, Norreys backed off Tyrone, for fear of Spanish and papal intervention, and a truce was arranged, to expire on 1 January 1596; this was extended to May. In the following year, a new arrangement was entered by Norreys at Dundalk, which Russell criticised since it allowed Tyrone to win time for outside intervention. To Russell's way of thinking, Norreys was too well affected to Tyrone, and his tendency to show mercy to the conquered was wholly unsuited to the circumstances. In May, Tyrone informed Norreys of his meeting with a Spaniard from a ship that had put into Killybegs, and assured him that he had refused such aid as had been offered by Philip II of Spain

Philip II (21 May 152713 September 1598), sometimes known in Spain as Philip the Prudent (), was King of Spain from 1556, King of Portugal from 1580, and King of Naples and List of Sicilian monarchs, Sicily from 1554 until his death in 1598. He ...

.

Owing to troubles in the province of Connaught, Norreys travelled there with Sir Geoffrey Fenton

Sir Geoffrey Fenton ( – 19 October 1608) was an English writer, Privy Councillor, and Principal Secretary of State in Ireland.

Early literary years

Geoffrey (spelt Jeffrey by Lodge) was born in 1539, the son of Henry Fenton of Sturton-le-Ste ...

in June 1596 to parley with the local lords. He censured the presidential government of Sir Richard Bingham for having stirred up the lords into rebellion - although the influence of Tyrone's ally, Hugh Roe O'Donnell

Hugh Roe O'Donnell II (; 20 October 1572 – 30 August 1602), also known as Red Hugh O'Donnell, was an Irish Chief of the Name, clan chief and senior leader of the Irish confederacy during the Nine Years' War (Ireland), Nine Years' War. He was ...

, in this respect was also recognised, especially since Sligo castle had lately fallen to the rebels. Bingham was suspended and detained in Dublin (he was later detained in the Fleet in London). However, during a campaign of six months, Norreys failed to restore peace to Connaught, and despite a nominal submission by the lords, hostilities broke out again as soon as he had returned north to Newry in December 1596.

At this point, Norreys was heartily sick of his situation. He sought to be recalled, citing poor health and the effect upon him of various controversies. As always, Russell weighed in with criticism and claimed that Norreys was feigning poor health in Athlone and seeking to have the lord deputy caught up in his failure. An analysis of this situation in October 1596, which was backed by the Earl of Essex, had it that Norreys' style was "''to invite to dance and be merry upon false hopes of a hollow peace''". This approach was in such contrast to Russell's instincts that there was a risk of collapse in the Irish government.

In the end, it was decided in late 1596 to remove both men from Ulster, sending Russell back to England and Norreys to Munster. Being unclear as to how Dublin wanted to deal with him, Norreys remained at Newry negotiating with Tyrone, while Russell was replaced as lord deputy by Thomas Burgh, 7th Baron Strabolgi. Burgh too had been on bad terms with Norreys during his tour of duty in the Low Countries, and was an Essex man to boot, a point which had grated with Cecil, who maintained his confidence in the experience command of Norreys. Although he did meet the new lord deputy at Dublin "''with much counterfeit kindness''", Norreys felt the new appointment as a disgrace upon himself.

Death

Norreys returned toMunster

Munster ( or ) is the largest of the four provinces of Ireland, located in the south west of the island. In early Ireland, the Kingdom of Munster was one of the kingdoms of Gaelic Ireland ruled by a "king of over-kings" (). Following the Nor ...

to serve as president, but his health was fragile and he soon sought leave to give up his responsibilities. He complained that he had "''lost more blood in her Majesty's service than any he knew''". At his brother's house in Mallow, he developed gangrene

Gangrene is a type of tissue death caused by a lack of blood supply. Symptoms may include a change in skin color to red or black, numbness, swelling, pain, skin breakdown, and coolness. The feet and hands are most commonly affected. If the ga ...

, owing to poor treatment of old wounds, and was also suffering from a settled melancholia

Melancholia or melancholy (from ',Burton, Bk. I, p. 147 meaning black bile) is a concept found throughout ancient, medieval, and premodern medicine in Europe that describes a condition characterized by markedly depressed mood, bodily complain ...

over the disregard by the crown of his 26 years’ service. On 3 September 1597 he went up to his chamber, where he died in the arms of his brother Thomas.

It was generally supposed that his death was caused by a broken heart. Another version, recounted by Philip O'Sullivan Beare

Philip O'Sullivan Beare (, –1636) was a military officer descended from the Gaelic nobility of Ireland, who became more famous as a writer. He fled to Habsburg Spain during the time of Tyrone's Rebellion, when the Irish clans and Gaelic Irelan ...

, states that a servant boy, on seeing Norreys go into the chamber in the company of a shadowy figure, had listened at the door and heard the soldier enter a pact with the Devil. At midnight the pact was enforced, and on breaking in the door the next morning the frightened servants found that Norreys' head and upper chest were facing backwards.

Norreys' body was embalmed, and the queen sent a letter of condolence to his parents, who had by now lost several of their sons in the Irish service. He was interred in Yattendon

Yattendon is a village and civil parish northeast of Newbury, Berkshire, Newbury in the county of Berkshire, England. The M4 motorway passes through the fields of the village which lie south and below the elevations of its nucleated village, c ...

Church, Berkshire

Berkshire ( ; abbreviated ), officially the Royal County of Berkshire, is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Oxfordshire to the north, Buckinghamshire to the north-east, Greater London ...

) - a monument

A monument is a type of structure that was explicitly created to commemorate a person or event, or which has become relevant to a social group as a part of their remembrance of historic times or cultural heritage, due to its artistic, historical ...

there has his helmet hanging above - and his effigy

An effigy is a sculptural representation, often life-size, of a specific person or a prototypical figure. The term is mostly used for the makeshift dummies used for symbolic punishment in political protests and for the figures burned in certain ...

(portrait by Zucchero, engraved by J. Thane.) was placed on the Norreys monument

A monument is a type of structure that was explicitly created to commemorate a person or event, or which has become relevant to a social group as a part of their remembrance of historic times or cultural heritage, due to its artistic, historical ...

in Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an Anglican church in the City of Westminster, London, England. Since 1066, it has been the location of the coronations of 40 English and British m ...

.

Legacy

In 1600, during the course of the Nine Years' War, Sir Charles Blount, Lord Mountjoy, the commander who eventually defeated Tyrone, built a double-ditch fort between Newry and Armagh, which he named Mountnorris in honour of Norreys. It was built on a round earthwork believed to have been constructed by the Norse-Gaels on a site that Norreys had once considered in the course of his northern campaign. Mountjoy referred to Norreys as his tutor in war, and took note of his former understanding thatGaelic Ireland

Gaelic Ireland () was the Gaelic political and social order, and associated culture, that existed in Ireland from the late Prehistory of Ireland, prehistoric era until the 17th century. It comprised the whole island before Anglo-Norman invasi ...

was not to be brought under the control of the Crown except by force and large permanent garrisons. Norreys' conduct at the start of the Nine Years' War

The Nine Years' War was a European great power conflict from 1688 to 1697 between Kingdom of France, France and the Grand Alliance (League of Augsburg), Grand Alliance. Although largely concentrated in Europe, fighting spread to colonial poss ...

, however, suggests a mellowing during his maturity. The aggressive Earl of Essex

Earl of Essex is a title in the Peerage of England which was first created in the 12th century by King Stephen of England. The title has been recreated eight times from its original inception, beginning with a new first Earl upon each new cre ...

– an equally ill-fated hero of the people – also chose to negotiate with Hugh Mór O'Neill, Lord of Tír Eoghain, and it was Norreys' original tactics that eventually succeeded in destroying the Irish clan

Irish clans are traditional kinship groups sharing a common surname and heritage and existing in a lineage-based society, originating prior to the 17th century. A clan (or in Irish, plural ) included the chief and his patrilineal relatives; howe ...

system under Lord Mountjoy.

The most significant legacy of Norreys' long military career lay in his support of the Dutch revolt

The Eighty Years' War or Dutch Revolt (; 1566/1568–1648) was an armed conflict in the Habsburg Netherlands between disparate groups of rebels and the Spanish government. The causes of the war included the Reformation, centralisation, exc ...

against the Habsburg forces, and later in keeping King Henri IV

Henry IV (; 13 December 1553 – 14 May 1610), also known by the epithets Good King Henry (''le Bon Roi Henri'') or Henry the Great (''Henri le Grand''), was King of Navarre (as Henry III) from 1572 and King of France from 1589 to 16 ...

from having to concede the political independence

Independence is a condition of a nation, country, or state, in which residents and population, or some portion thereof, exercise self-government, and usually sovereignty, over its territory. The opposite of independence is the status of a ...

of the Duchy of Brittany

The Duchy of Brittany (, ; ) was a medieval feudal state that existed between approximately 939 and 1547. Its territory covered the northwestern peninsula of France, bordered by the Bay of Biscay to the west, and the English Channel to the north. ...

to Breton Catholic League leader Philippe Emmanuel, Duke of Mercœur

Philippe-Emmanuel de Lorraine, Duke of Mercœur and of Penthièvre (9 September 1558, in Nomeny, Meurthe-et-Moselle – 19 February 1602, in Nürnberg) was a French soldier, a prince of the Holy Roman Empire and a prominent member of the Catholi ...

, who had the military backing of Habsburg Spain

Habsburg Spain refers to Spain and the Hispanic Monarchy (political entity), Hispanic Monarchy, also known as the Rex Catholicissimus, Catholic Monarchy, in the period from 1516 to 1700 when it was ruled by kings from the House of Habsburg. In t ...

.

In addition to his role in the destruction of both the Irish clan

Irish clans are traditional kinship groups sharing a common surname and heritage and existing in a lineage-based society, originating prior to the 17th century. A clan (or in Irish, plural ) included the chief and his patrilineal relatives; howe ...

s and Gaelic Ireland

Gaelic Ireland () was the Gaelic political and social order, and associated culture, that existed in Ireland from the late Prehistory of Ireland, prehistoric era until the 17th century. It comprised the whole island before Anglo-Norman invasi ...

, the legacy of Norreys to Irish history

The first evidence of human presence in Ireland dates to around 34,000 years ago, with further findings dating the presence of ''Homo sapiens'' to around 10,500 to 7,000 BC. The receding of the ice after the Younger Dryas cold phase of the Qua ...

was further cemented when the Roman Catholic priest

The priesthood is the office of the ministers of religion, who have been commissioned ("ordained") with the holy orders of the Catholic Church. Technically, bishops are a priestly order as well; however, in common English usage ''priest'' re ...

he condemned to death and executed at Clonmel

Clonmel () is the county town and largest settlement of County Tipperary, Republic of Ireland, Ireland. The town is noted in Irish history for its resistance to the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland, Cromwellian army which sacked the towns of Dro ...

in 1585, Fr. Muiris Mac Ionrachtaigh

Muiris Mac Ionrachtaigh, anglicised as Maurice MacKenraghty (died 30 April 1585), was an Irish Roman Catholic priest who was put to death, officially for high treason, but in reality as part of the religious persecution of the Catholic Church in ...

, was beatified

Beatification (from Latin , "blessed" and , "to make") is a recognition accorded by the Catholic Church of a deceased person's entrance into Heaven and capacity to intercede on behalf of individuals who pray in their name. ''Beati'' is the ...

by Pope John Paul II

Pope John Paul II (born Karol Józef Wojtyła; 18 May 19202 April 2005) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 16 October 1978 until Death and funeral of Pope John Paul II, his death in 2005.

In his you ...

, alongside 16 other Irish Catholic Martyrs

Irish Catholic Martyrs () were 24 Irish men and women who have been beatified or canonized for both a life of heroic virtue and for dying for their Catholic faith between the reign of King Henry VIII and Catholic Emancipation in 1829.

The more ...

of the Reformation in Ireland

The Reformation in Ireland was a movement for the reform of religious life and institutions that was introduced into Ireland by the English Crown at the behest of King Henry VIII of England. His desire for an annulment of his marriage was known ...

, on 27 September 1992.

Family

Norreys never married, and he had no children. Norreys is pronounced "Norr-iss".See also

*English Armada

The English Armada (), also known as the Counter Armada, Drake–Norris Expedition, Portugal Expedition, was an attack fleet sent against Spain by Queen Elizabeth I of England that sailed on 28 April 1589 during the undeclared Anglo-Spanish W ...

(Drake-Norris Expedition)

References

Bibliography

* John S Nolan, ''Sir John Norreys and the Elizabethan Military World'' (University of Exeter, 1997) * Richard Bagwell, ''Ireland under the Tudors'' 3 vols. (London, 1885–1890) * John O'Donovan (ed.) ''Annals of Ireland by the Four Masters'' (1851). * ''Calendar of State Papers: Carew MSS.'' 6 vols (London, 1867–1873). * ''Calendar of State Papers: Ireland'' (London) * Nicholas Canny ''The Elizabethan Conquest of Ireland'' (Dublin, 1976); ''Kingdom and Colony'' (2002). * Steven G. Ellis ''Tudor Ireland'' (London, 1985) . * Hiram Morgan ''Tyrone's War'' (1995). * Standish O'Grady (ed.) "''Pacata Hibernia''" 2 vols. (London, 1896). * Cyril Falls ''Elizabeth's Irish Wars'' (1950; reprint London, 1996) . * *External links

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Norreys, John 1540s births 1597 deaths Priest hunters People from Yattendon People of Elizabethan Ireland 16th-century English knights 16th-century English soldiersJohn

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Second E ...

Irish MPs 1585–1586

Members of the Parliament of Ireland (pre-1801) for County Cork constituencies

Knights Bachelor

Heirs apparent who never acceded

Military personnel from Berkshire