Johann Joachim Becher on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Johann Joachim Becher (; 6 May 1635 – October 1682) was a

Johann Joachim Becher-Preises

at uh.edu * {{DEFAULTSORT:Becher, Johann Joachim 1635 births 1682 deaths German alchemists 17th-century German chemists 17th-century German physicians 17th-century alchemists German scholars People from Speyer Academic staff of Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz 17th-century German male writers Cameralists

German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany, the country of the Germans and German things

**Germania (Roman era)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizenship in Germany, see also Ge ...

physician

A physician, medical practitioner (British English), medical doctor, or simply doctor is a health professional who practices medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring health through the Medical education, study, Med ...

, alchemist

Alchemy (from the Arabic word , ) is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscientific tradition that was historically practised in China, India, the Muslim world, and Europe. In its Western form, alchemy is first ...

, precursor of chemistry

Chemistry is the scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter. It is a physical science within the natural sciences that studies the chemical elements that make up matter and chemical compound, compounds made of atoms, molecules a ...

, scholar, polymath

A polymath or polyhistor is an individual whose knowledge spans many different subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific problems. Polymaths often prefer a specific context in which to explain their knowledge, ...

and adventurer, best known for his ''terra pinguis'' theory which became the phlogiston theory

The phlogiston theory, a superseded scientific theory, postulated the existence of a fire-like element dubbed phlogiston () contained within combustible bodies and released during combustion. The name comes from the Ancient Greek (''burnin ...

of combustion, and his advancement of Austrian cameralism

Cameralism ( German: ''Kameralismus'') was a German school of public finance, administration and economic management in the 18th and early 19th centuries that aimed at strong management of a centralized economy for the benefit mainly of the ...

.

Early life and education

Becher was born inSpeyer

Speyer (, older spelling ; ; ), historically known in English as Spires, is a city in Rhineland-Palatinate in the western part of the Germany, Federal Republic of Germany with approximately 50,000 inhabitants. Located on the left bank of the r ...

during the Thirty Years War. His father was a Lutheran

Lutheranism is a major branch of Protestantism that emerged under the work of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German friar and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practices of the Catholic Church launched ...

minister and died when Becher was a child. At the age of thirteen Becher found himself responsible not only for his own support but also for that of his mother and two brothers. He learned and practiced several small handicrafts, devoted his nights to study of the most miscellaneous description and earned a pittance by teaching.

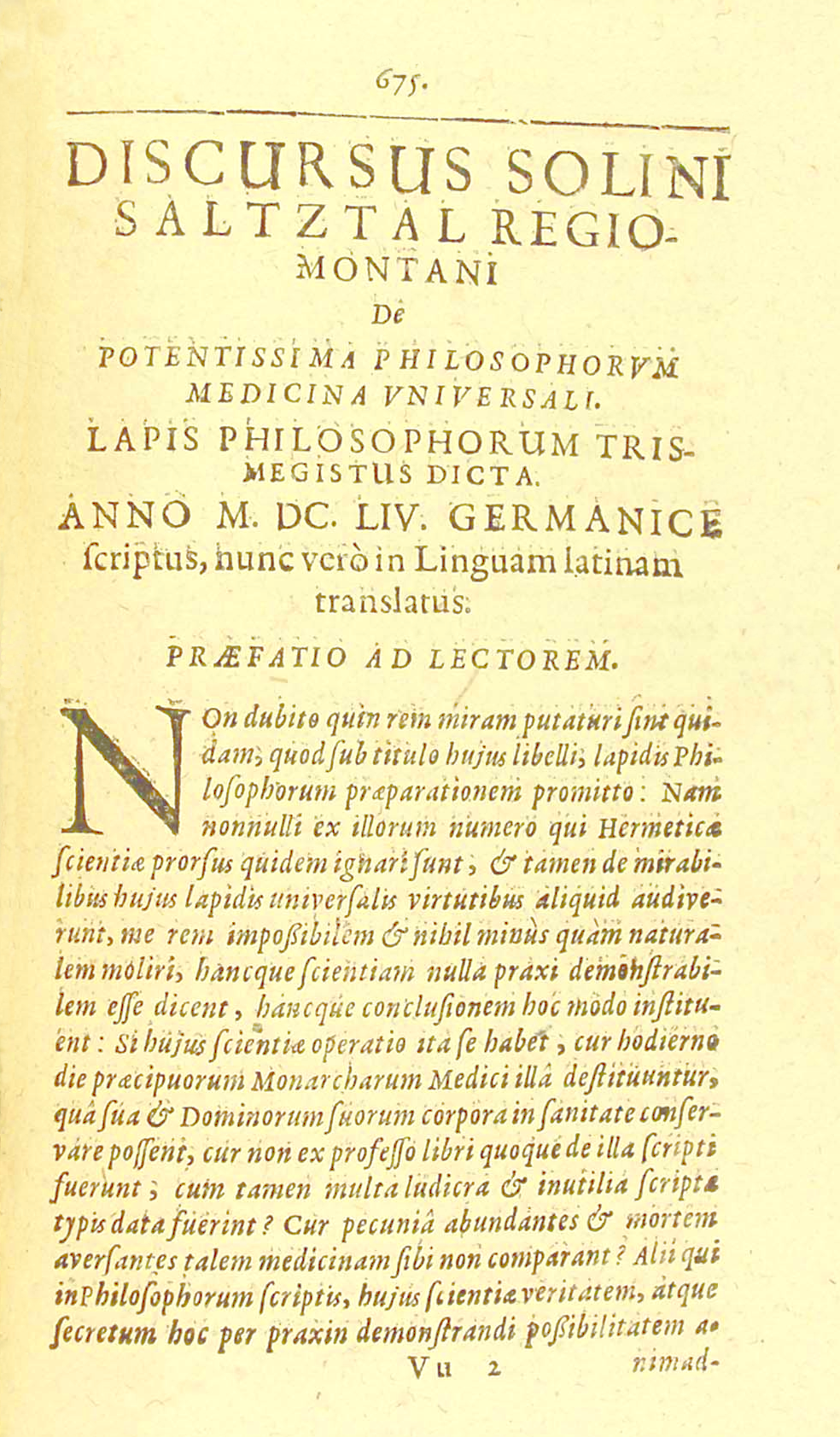

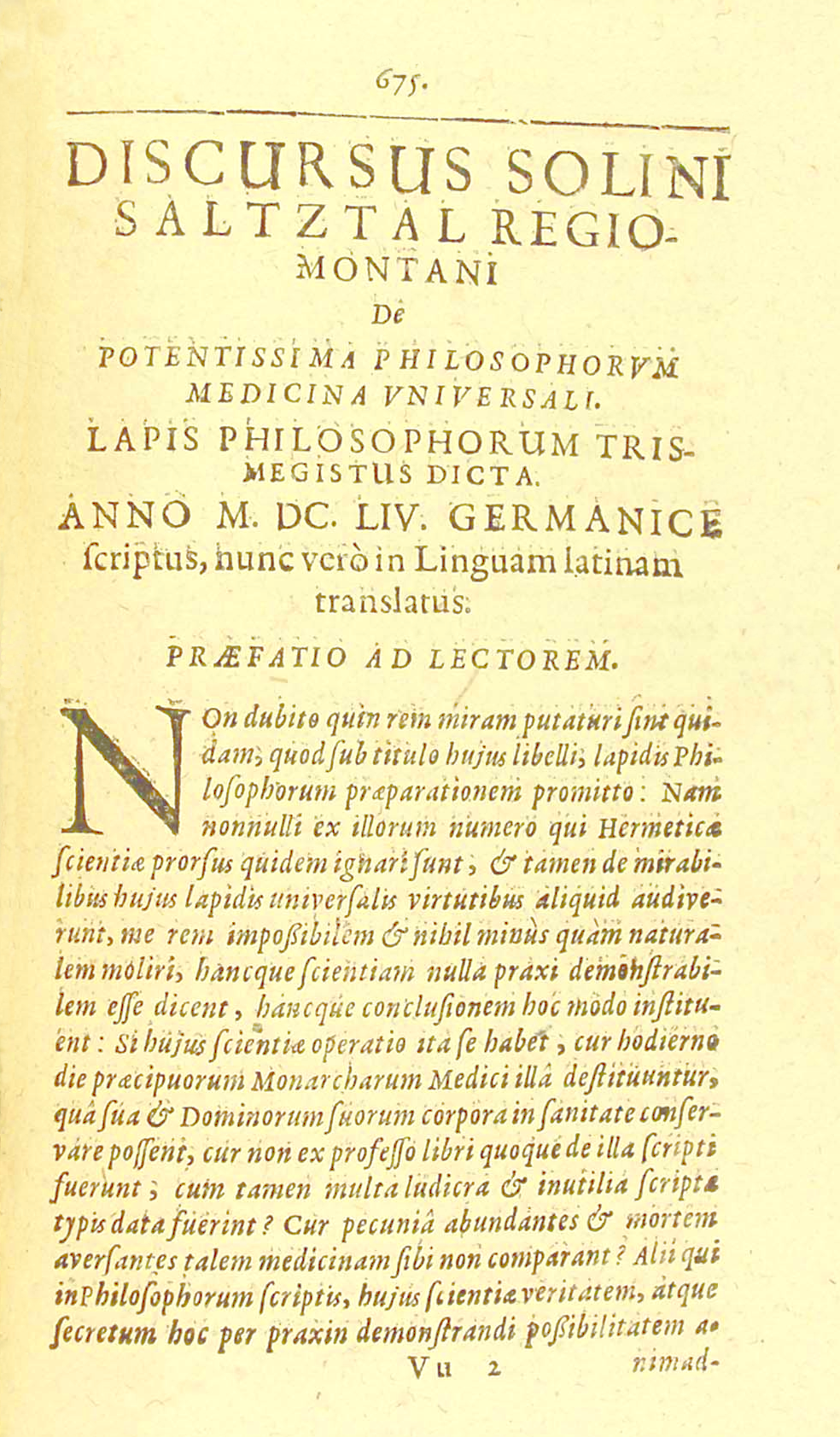

In 1654, at the age of nineteen, he published the ''Discurs von der Großmächtigen Philosophischen Universal-Artzney / von den Philosophis genannt Lapis Philosophorum Trismegistus'' (discourse about the almighty philosophical and universal medicine by the philosopher called Lapis Philosophorum Trismegistus) under the pseudonym 'Solinus Salzthal of Regiomontus.' (2016). ''The Business of Alchemy: Science and Culture in the Holy Roman Empire.'' Princeton: Princeton University Press. , p. 40/41; see also: 'The Emperor's Mercantile Alchemist' in: (2006) - ''From Alchemy to Chemistry in Picture and Story.'' Hoboken N.J. : John Wiley & Sons. . p. 231f. Chisholm writes in the 11th. ed. of the Encyclopædia Britannica that Becher "published an edition of Salzthal’s ''Tractatus de lapide trismegisto''." It was published in Latin in 1659 as ''Discursus Solini Saltztal Regiomontani De potentissima philosophorum medicina universali, lapis philosophorum trismegistus dicta'' (translated by Johannes Jacobus Heilmann) in vol. VI of the '' Theatrum Chemicum''.

Career

In 1657, he was appointed professor of medicine at theUniversity of Mainz

The Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz () is a public research university in Mainz, Rhineland Palatinate, Germany. It has been named after the printer Johannes Gutenberg since 1946. it had approximately 32,000 students enrolled in around 100 a ...

and physician to the archbishop- elector. His ''Metallurgia'' was published in 1660; and the next year appeared his ''Character pro notitia linguarum universali'', in which he gives 10,000 words for use as a universal language

Universal language may refer to a hypothetical or historical language spoken and understood by all or most of the world's people. In some contexts, it refers to a means of communication said to be understood by all humans. It may be the idea o ...

. In 1663, he published his ''Oedipum Chemicum'' and a book on animals, plants and minerals (''Thier- Kräuter- und Bergbuch'').

In 1666, he was made councillor of commerce () at Vienna

Vienna ( ; ; ) is the capital city, capital, List of largest cities in Austria, most populous city, and one of Federal states of Austria, nine federal states of Austria. It is Austria's primate city, with just over two million inhabitants. ...

, where he had gained the powerful support of the prime minister of Emperor Leopold I. Sent by the emperor on a mission to the Netherlands

, Terminology of the Low Countries, informally Holland, is a country in Northwestern Europe, with Caribbean Netherlands, overseas territories in the Caribbean. It is the largest of the four constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Nether ...

, he wrote there in ten days his ''Methodus Didactica'', which was followed by the ''Regeln der Christlichen Bundesgenossenschaft'' and the ''Politischer Discurs von den eigentlichen Ursachen des Auf- und Abblühens der Städte, Länder und Republiken''. In 1669, he published his ''Physica subterranea''; the same year, he was engaged with the count of Hanau in a scheme to acquire Dutch colonization of Guiana from the Dutch West India Company

The Dutch West India Company () was a Dutch chartered company that was founded in 1621 and went defunct in 1792. Among its founders were Reynier Pauw, Willem Usselincx (1567–1647), and Jessé de Forest (1576–1624). On 3 June 1621, it was gra ...

.

Meanwhile, he had been appointed physician to the elector of Bavaria

Bavaria, officially the Free State of Bavaria, is a States of Germany, state in the southeast of Germany. With an area of , it is the list of German states by area, largest German state by land area, comprising approximately 1/5 of the total l ...

; but in 1670 he was again in Vienna advising on the establishment of a silk factory and propounding schemes for a great company to trade with the Low Countries

The Low Countries (; ), historically also known as the Netherlands (), is a coastal lowland region in Northwestern Europe forming the lower Drainage basin, basin of the Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta and consisting today of the three modern "Bene ...

and for a canal to unite the Rhine

The Rhine ( ) is one of the List of rivers of Europe, major rivers in Europe. The river begins in the Swiss canton of Graubünden in the southeastern Swiss Alps. It forms part of the Swiss-Liechtenstein border, then part of the Austria–Swit ...

and Danube

The Danube ( ; see also #Names and etymology, other names) is the List of rivers of Europe#Longest rivers, second-longest river in Europe, after the Volga in Russia. It flows through Central and Southeastern Europe, from the Black Forest sou ...

.

In 1678, he crossed to England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

. He travelled to Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

where he visited the mines at the request of Prince Rupert

Prince Rupert of the Rhine, Duke of Cumberland, (17 December 1619 ( O.S.) 7 December 1619 (N.S.)– 29 November 1682 (O.S.) December 1682 (N.S) was an English-German army officer, admiral, scientist, and colonial governor. He first rose to ...

. He afterwards travelled for the same purpose to Cornwall

Cornwall (; or ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is also one of the Celtic nations and the homeland of the Cornish people. The county is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, ...

, and spent a year there. At the beginning of 1680, he presented a paper to the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

in which he attempted to deprive Christiaan Huygens

Christiaan Huygens, Halen, Lord of Zeelhem, ( , ; ; also spelled Huyghens; ; 14 April 1629 – 8 July 1695) was a Dutch mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and inventor who is regarded as a key figure in the Scientific Revolution ...

of the honour of applying the pendulum to the measurement of time. In 1682, he returned to London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

, where he wrote ''Närrische Weisheit und weise Narrheit'' (in which, according to Otto Mayr he made extensive references to temperature regulated furnaces), a book the ''Chymischer Glücks-Hafen, Oder Grosse Chymische Concordantz Und Collection, Von funffzehen hundert Chymischen Processen'' and died in October of the same year.

Legacy

Austrian Cameralist

Becher was the most original and influential theorist of Austriancameralism

Cameralism ( German: ''Kameralismus'') was a German school of public finance, administration and economic management in the 18th and early 19th centuries that aimed at strong management of a centralized economy for the benefit mainly of the ...

. He sought to balance between the need to reinstate postwar levels of population and production both in the countryside and the towns.Charles W. Ingrao, ''The Habsburg Monarchy: 1618-1815'', New York: Cambridge University Press, Second edition. ; p. 92-93. By leaning more seriously on trade and commerce, Austrian cameralism helped to transfer attention to the troubles of the monarchy's urban economies. Ferdinand II had already taken some corrective steps before he died by attempting to ease the debts of the Bohemian towns and to put limits on some of the land-holding nobility's commercial rights. Even though preceding Habsburgs

The House of Habsburg (; ), also known as the House of Austria, was one of the most powerful dynasties in the history of Europe and Western civilization. They were best known for their inbreeding and for ruling vast realms throughout Europe d ...

had held the guilds responsible for their restrictiveness, wastefulness, and the poor value of the merchandise they created, Ferdinand II ramped up the pressure by extending rights to private artisans who usually then earned the support of powerful local leaders such as seigneurs

A seigneur () or lord is an originally feudal title in France before the Revolution, in New France and British North America until 1854, and in the Channel Islands to this day. The seigneur owned a seigneurie, seigneury, or lordship—a form of ...

, military commanders, churches, and universities. An edict by Leopold I in 1689 had granted the government the right to monitor and control the number of masters and cut down on the monopoly effect of guild operations. Even previous to this, Becher, who was against all forms of monopoly

A monopoly (from Greek language, Greek and ) is a market in which one person or company is the only supplier of a particular good or service. A monopoly is characterized by a lack of economic Competition (economics), competition to produce ...

, surmised that a third of the Austrian lands’ 150,000 artisans were "Schwarzarbeiter" who were not in a guild.

Immediately after the Thirty Years’ War the Bohemian towns had petitioned Ferdinand to refine its own raw materials into more finished goods for export. Becher became the leading force in attempting this conversion. By 1666 he had inspired the creation of a Commerce Commission (Kommerzkollegium) in Vienna, as well as the reestablishment of the first postwar silk plantation on the Lower Austrian estates of Hofkammer President Sinzendorf. Becher then subsequently helped create a Kunst- und Werkhaus in which foreign masters trained non-guild artisans in the production of finished goods. By 1672 he had promoted the construction of a wool factory in Linz. Four years later he established a textile workhouse for vagabonds in the Boemian town of Tabor that eventually employed 186 spinners under his own directorship.

Some of Becher’s projects met with limited success. In time Linz’s new wool factory even became one of the largest and most important in Europe. Yet most of the government initiatives ended in failure. The Commerce Commission was doomed by Sinzendorf’s corruption and indifference. The Tabor workhouse nearly collapsed after just five years owing to the lack of government funding, and was then destroyed two years later during the Turkish invasion. The Oriental Company was fatally handicapped by a combination of poor management, government export prohibitions against Turkey, the opposition of Ottoman (principally Greek) merchants, and ultimately by the outbreak of war. The Kunst- und Werkhaus also folded during the 1680s, partly because of the regime’s unwillingness to import a significant number of foreign, Protestant teachers and skilled workers.

Chemist and alchemist

William Cullen

William Cullen (; 15 April 17105 February 1790) was a British physician, chemist and agriculturalist from Hamilton, Scotland, who also served as a professor at the Edinburgh Medical School. Cullen was a central figure in the Scottish Enli ...

considered Becher as a chemist of first importance and ''Physica Subterranea'' as the most considerable of Bechers writings.

Bill Bryson

William McGuire Bryson ( ; born 8 December 1951) is an American-British journalist and author. Bryson has written a number of nonfiction books on topics including travel, the English language, and science. Born in the United States, he has be ...

, in his '' A Short History of Nearly Everything'', notes:

Chemistry as an earnest and respectable science is often said to date from 1661, whenIn Becher's ''Physica Subterranea'', he proposes a model of matter based onRobert Boyle Robert Boyle (; 25 January 1627 – 31 December 1691) was an Anglo-Irish natural philosopher, chemist, physicist, Alchemy, alchemist and inventor. Boyle is largely regarded today as the first modern chemist, and therefore one of the foun ...of Oxford published ''The Sceptical Chymist ''The Sceptical Chymist: or Chymico-Physical Doubts & Paradoxes'' is the title of a book by Robert Boyle, published in London in 1661. In the form of a dialogue, the ''Sceptical Chymist'' presented Boyle's hypothesis that matter consisted of cor ...'' — the first work to distinguish between chemists and alchemists — but it was a slow and often erratic transition. Into the eighteenth century scholars could feel oddly comfortable in both camps — like the German Johann Becher, who produced sober and unexceptionable work onmineralogy Mineralogy is a subject of geology specializing in the scientific study of the chemistry, crystal structure, and physical (including optical mineralogy, optical) properties of minerals and mineralized artifact (archaeology), artifacts. Specific s ...called ''Physica Subterranea'', but who also was certain that, given the right materials, he could make himself invisible.Bill Bryson, ''A Short History of Nearly Everything'', London: Black Swan, 2003 edition. ; p. 130.

Paracelsus

Paracelsus (; ; 1493 – 24 September 1541), born Theophrastus von Hohenheim (full name Philippus Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim), was a Swiss physician, alchemist, lay theologian, and philosopher of the German Renaissance.

H ...

's ''tria prima'' (salt, mercury, sulphur). He proposes that all matter is composed of air, water and three earths: ''terra lapidea'' related to the fusibility, ''terra fluida'' related to the fluidity and volatility, and ''terra pinguis'' related to the combustibility and flammability

A combustible material is a material that can burn (i.e., sustain a flame) in air under certain conditions. A material is flammable if it ignites easily at ambient temperatures. In other words, a combustible material ignites with some effort a ...

. According to Becher, flammable objects burned because they contained ''terra pinguis''. Even metals had a bit of ''terra pinguis'', observed in the process of calcination

Calcination is thermal treatment of a solid chemical compound (e.g. mixed carbonate ores) whereby the compound is raised to high temperature without melting under restricted supply of ambient oxygen (i.e. gaseous O2 fraction of air), generally f ...

. The concept of ''terra pinguis'' was lated developed by Georg Ernst Stahl

Georg Ernst Stahl (22 October 1659Stahl's date of birth is often given erroneously as 1660. The correct date is recorded in the parish register of St. John's church, Ansbach. See – 24 May 1734) was a German chemist, physician and philosopher. ...

into phlogiston theory

The phlogiston theory, a superseded scientific theory, postulated the existence of a fire-like element dubbed phlogiston () contained within combustible bodies and released during combustion. The name comes from the Ancient Greek (''burnin ...

.

References

Sources

* * *Further reading

*Anthony Endres, ''Neoclassical Microeconomic Theory: the founding Austrian version'' (London: Routledge Press, 1997). *Erik Grimmer-Solem, ''The Rise of Historical Economics and Social Reform in Germany 1864–1894'' (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003).External links

*Johann Joachim Becher-Preises

at uh.edu * {{DEFAULTSORT:Becher, Johann Joachim 1635 births 1682 deaths German alchemists 17th-century German chemists 17th-century German physicians 17th-century alchemists German scholars People from Speyer Academic staff of Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz 17th-century German male writers Cameralists