Johann Bessler on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Johann Ernst Elias Bessler (''ca''. 1680 – 30 November 1745), known as Orffyreus or Orffyré, was a German entrepreneur who claimed to have built several

Bessler then constructed a still larger wheel in

Bessler then constructed a still larger wheel in

Perpetual Motion

, ''Chambers's encyclopædia: a dictionary of universal knowledge'', vol. 7, (London: W. and R. Chambers, 1868), pp. 412-415. If the maid's confession were true, the testimonies by Prince Karl, 's Gravesande, and others about the conditions under which the wheel was tested and exhibited must be flawed.

perpetual motion

Perpetual motion is the motion of bodies that continues forever in an unperturbed system. A perpetual motion machine is a hypothetical machine that can do work indefinitely without an external energy source. This kind of machine is impossible ...

machines. Those claims generated considerable interest and controversy among some of the leading natural philosophers

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe, while ignoring any supernatural influence. It was dominant before the developme ...

of the day, including Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (or Leibnitz; – 14 November 1716) was a German polymath active as a mathematician, philosopher, scientist and diplomat who is credited, alongside Sir Isaac Newton, with the creation of calculus in addition to ...

, Johann Bernoulli

Johann Bernoulli (also known as Jean in French or John in English; – 1 January 1748) was a Swiss people, Swiss mathematician and was one of the many prominent mathematicians in the Bernoulli family. He is known for his contributions to infin ...

, John Theophilus Desaguliers

John Theophilus Desaguliers (12 March 1683 – 29 February 1744) was a French-born British natural philosopher, clergyman, engineer and freemason who was elected to the Royal Society in 1714 as experimental assistant to Isaac Newton. He had stu ...

, and Willem 's Gravesande

Willem Jacob 's Gravesande (26 September 1688 – 28 February 1742) was a Dutch mathematician and natural philosopher, chiefly remembered for developing experimental demonstrations of the laws of classical mechanics and the first experimental m ...

. The modern scientific consensus is that Bessler perpetrated a deliberate fraud, although the details of this have not been satisfactorily explained.

Life and career

Bessler was born to a peasant family inUpper Lusatia

Upper Lusatia (, ; , ; ; or ''Milsko''; ) is a historical region in Germany and Poland. Along with Lower Lusatia to the north, it makes up the region of Lusatia, named after the Polabian Slavs, Slavic ''Lusici'' tribe. Both parts of Lusatia a ...

, in the German Electorate of Saxony

The Electorate of Saxony, also known as Electoral Saxony ( or ), was a territory of the Holy Roman Empire from 1356 to 1806 initially centred on Wittenberg that came to include areas around the cities of Dresden, Leipzig and Chemnitz. It was a ...

, ''circa'' 1680. He went to school in Zittau

Zittau (; ; ; ; ; Lusatian dialects, Upper Lusatian dialect: ''Sitte''; ) is the southeasternmost city in the Germany, German state of Saxony, and belongs to the Görlitz (district), district of Görlitz, Germany's easternmost Districts of Germ ...

, where (according to his own account) he excelled in his studies and became a favorite of Christian Weise

Christian Weise (30 April 1642 – 21 October 1708), also known under the pseudonyms Siegmund Gleichviel, Orontes, Catharinus Civilis and Tarquinius Eatullus, was a German writer, dramatist, poet, pedagogue and librarian of the Baroque era. He pro ...

, the rector of the local ''Gymnasium''. After he left school he began to travel widely, seeking his fortune. Having saved an alchemist

Alchemy (from the Arabic word , ) is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscientific tradition that was historically practised in China, India, the Muslim world, and Europe. In its Western form, alchemy is first ...

from drowning in a well, he was rewarded with instruction on the fabrication of elixirs. After that Bessler earned his living as a healer and an unlicensed physician. He was also an apprentice watchmaker, until his fortunes improved when he married the wealthy daughter of the physician and mayor of Annaberg, Dr. Christian Schuhmann.

Bessler adopted the pseudonym "Orffyreus" by writing the letters of the alphabet in a circle and selecting the letters diametrically opposite to those of his surname (what would modernly be called a ROT13

ROT13 is a simple letter substitution cipher that replaces a letter with the 13th letter after it in the Latin alphabet.

ROT13 is a special case of the Caesar cipher which was developed in ancient Rome, used by Julius Caesar in the 1st centur ...

cipher), thus obtaining ''Orffyre'', which he then Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

ized into ''Orffyreus''.Rupert T. Gould

Rupert Thomas Gould (16 November 1890 – 5 October 1948) was a lieutenant-commander in the British Royal Navy noted for his contributions to horology (the science and study of timekeeping devices). He was also an author and radio personality.

...

, "Orffyreus's Wheel," in ''Oddities: A Book of Unexplained Facts'', revised ed., (London: Geoffrey Bles, 1944), pp. 89-116. Reprinted by Kessinger Pub Co., 2003, . That was the name by which he was generally known thereafter.

Orffyreus's wheels

In 1712, Bessler appeared in the town ofGera

Gera () is a city in the German state of Thuringia. With around 93,000 inhabitants, it is the third-largest city in Thuringia after Erfurt and Jena as well as the easternmost city of the ''Thüringer Städtekette'', an almost straight string of ...

in the province of Reuss and exhibited a "self-moving wheel," which was about in diameter and thick. Once in motion it was capable of lifting several kilograms (pounds). Bessler then moved to Draschwitz, a village near Leipzig

Leipzig (, ; ; Upper Saxon: ; ) is the most populous city in the States of Germany, German state of Saxony. The city has a population of 628,718 inhabitants as of 2023. It is the List of cities in Germany by population, eighth-largest city in Ge ...

, where in 1713 he constructed an even larger wheel, a little over in diameter and in width. That wheel could turn at fifty revolutions a minute and raise a weight of .

The eminent mathematician Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (or Leibnitz; – 14 November 1716) was a German polymath active as a mathematician, philosopher, scientist and diplomat who is credited, alongside Sir Isaac Newton, with the creation of calculus in addition to ...

visited Draschwitz in 1714 and witnessed a demonstration of Bessler's wheel. In a letter to Robert Erskine, physician and advisor to Russian Tsar Peter the Great

Peter I (, ;

– ), better known as Peter the Great, was the Sovereign, Tsar and Grand Prince of all Russia, Tsar of all Russia from 1682 and the first Emperor of Russia, Emperor of all Russia from 1721 until his death in 1725. He reigned j ...

, Leibniz later wrote that Bessler was "one of my friends" and that he believed Bessler's wheel to be a valuable invention. Bessler also received support from other members of Leibniz's intellectual circle, including mathematician Johann Bernoulli

Johann Bernoulli (also known as Jean in French or John in English; – 1 January 1748) was a Swiss people, Swiss mathematician and was one of the many prominent mathematicians in the Bernoulli family. He is known for his contributions to infin ...

, philosopher Christian Wolff, and architect Joseph Emanuel Fischer von Erlach

Joseph Emanuel Fischer von Erlach, also ''Fischer von Erlach the Younger'' (13 September 1693 in Vienna – 29 June 1742 in Vienna) was an Austrian architect of the Baroque, Rococo, and Baroque- Neoclassical.

Biography

Joseph Emanuel was the son ...

.

Bessler then constructed a still larger wheel in

Bessler then constructed a still larger wheel in Merseburg

Merseburg () is a town in central Germany in southern Saxony-Anhalt, situated on the river Saale, and approximately 14 km south of Halle (Saale) and 30 km west of Leipzig. It is the capital of the Saalekreis district. It had a diocese ...

, before moving to the independent state of Hesse-Kassel

The Landgraviate of Hesse-Kassel (), spelled Hesse-Cassel during its entire existence, also known as the Hessian Palatinate (), was a state of the Holy Roman Empire. The state was created in 1567 when the Landgraviate of Hesse was divided upon t ...

, where Prince Karl, the reigning Landgrave

Landgrave (, , , ; , ', ', ', ', ') was a rank of nobility used in the Holy Roman Empire, and its former territories. The German titles of ', ' ("margrave"), and ' ("count palatine") are of roughly equal rank, subordinate to ' ("duke"), and su ...

and an enthusiastic patron of mechanical inventors, appointed him as a commercial councillor (''Kommerzialrat'') for the town of Kassel

Kassel (; in Germany, spelled Cassel until 1926) is a city on the Fulda River in North Hesse, northern Hesse, in Central Germany (geography), central Germany. It is the administrative seat of the Regierungsbezirk Kassel (region), Kassel and the d ...

and provided him with rooms in Weissenstein Castle. It was there that in 1717 he constructed his largest wheel so far, in diameter and thick.

The inventor demonstrated the operation of his wheel before various audiences, always taking care that the mechanism within the wheel should remain hidden from view, purportedly to prevent others from stealing his invention. The wheel was examined externally by several scientists, including Willem 's Gravesande

Willem Jacob 's Gravesande (26 September 1688 – 28 February 1742) was a Dutch mathematician and natural philosopher, chiefly remembered for developing experimental demonstrations of the laws of classical mechanics and the first experimental m ...

, professor of mathematics and astronomy at Leiden University

Leiden University (abbreviated as ''LEI''; ) is a Public university, public research university in Leiden, Netherlands. Established in 1575 by William the Silent, William, Prince of Orange as a Protestantism, Protestant institution, it holds the d ...

, who reported that he could not detect any fraud regarding its operation. On 12 November 1717 the wheel was locked in a room in the castle with the doors and windows sealed to prevent any interference. This was witnessed by the Landgrave and various officials. Two weeks later, the seals were broken and the room was opened, whereupon the wheel was found to be revolving. The door was resealed until 4 January 1718. The wheel was then found to be turning at twenty-six revolutions per minute.

Bessler demanded 100,000 Reichsthaler

The ''Reichsthaler'' (; modern spelling Reichstaler), or more specifically the ''Reichsthaler specie'', was a standard thaler silver coin introduced by the Holy Roman Empire in 1566 for use in all German states, minted in various versions for the ...

s (equivalent to £20,000) in exchange for revealing the secret of his machines. Peter the Great was interested in purchasing the invention and sought advice on the matter from Gravesande and others. Gravesande examined the axle of the wheel, concluding that he could see no way in which power could be transmitted to it from the outside. Bessler, however, then smashed the wheel, accusing 's Gravesande of trying to discover the secret of the wheel without paying for it, and declaring that the curiosity of the professor had provoked him.

Later life

Bessler and his machine then vanished into obscurity. It is known that he was rebuilding his machine in 1727 and that 's Gravesande had agreed to examine it again, but it is not known whether it was ever tested. Bessler was apparently arrested in 1733, but by 1738 he was again free and living in an estate inBad Karlshafen

Bad Karlshafen () is a baroque, thermal salt spa town in the Kassel (district), district of Kassel, in Hesse, Germany. It has 2300 inhabitants in the main ward of Bad Karlshafen, and a further 1900 in the medieval village of Helmarshausen. It is s ...

, near Kassel. Bessler died in 1745, aged sixty-five, when he fell to his death from a four-and-a-half-story windmill he was constructing in Fürstenburg.

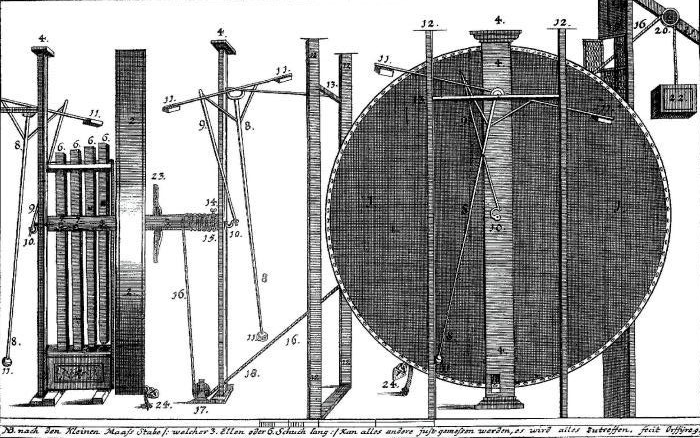

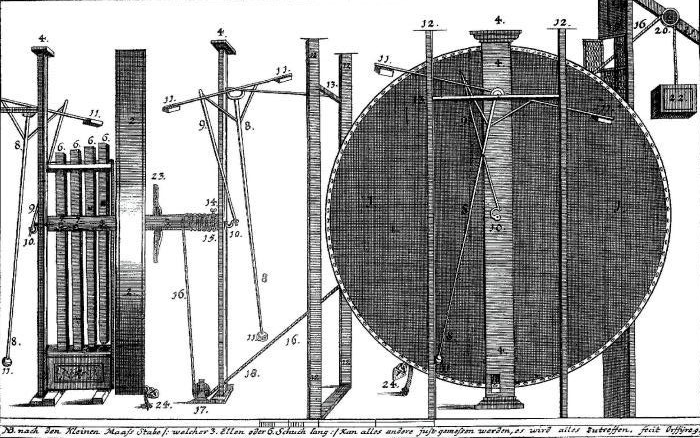

Mechanism of Orffyreus's Wheel

Bessler's devices were all hollow wheels, with canvas covering the internal mechanism, that turned on a horizontal axis supported by vertical wooden beams on either side of the wheel. Christian Wolff, who viewed the wheel in 1715, wrote that Bessler freely revealed that the device utilized weights of about . Fischer von Erlach, who viewed the wheel in 1721, reported: "At every turn of the wheel can be heard the sound of about eight weights, which fall gently on the side toward which the wheel turns." In a letter to SirIsaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton () was an English polymath active as a mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author. Newton was a key figure in the Scientific Revolution and the Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment that followed ...

, 's Gravesande reported that, when pushed, the wheel took two or three revolutions to reach a maximum speed of about 25 revolutions per minute. The wheels at Merseburg and Kassel were attached to three-bobbed pendula, one on either side, which presumably acted as regulators, limiting the maximum speed of revolution.

Bessler never revealed the mechanism that kept his wheel in motion and, according to surviving sources, the Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel was the only person whom he ever allowed to examine the inside of the wheel. In 1719 Bessler published a pamphlet in German and Latin, entitled ''The Triumphant Orffyrean Perpetual Motion'', which gives a very vague account of his principles. He indicated that the wheel depended upon weights placed so that they can "never attain equilibrium." This suggests that it was a kind of "overbalanced wheel," a hypothetical gravity-powered device which is now recognized by physicists as impossible (see perpetual motion

Perpetual motion is the motion of bodies that continues forever in an unperturbed system. A perpetual motion machine is a hypothetical machine that can do work indefinitely without an external energy source. This kind of machine is impossible ...

).

Allegations of fraud

Most of the people who met him, including supporters such as 's Gravesande, reported that Bessler was eccentric, ill-tempered, and perhaps even insane. From the beginning, Bessler's work generated accusations of fraud from various people, including mining engineer Johann Gottfried Borlach, mathematician Christian Wagner, model-maker Andreas Gärtner, Kassel court tutorJean-Pierre de Crousaz

Jean-Pierre de Crousaz (13 April 166322 March 1750) was a Swiss theologian and philosopher. He is now remembered more for his letters of commentary than his formal works.

Life

De Crousaz was born in Lausanne, Switzerland. He was a many-sided man, ...

, and others. Gärtner went on to gain employ as model-master in the court of Augustus II the Strong

Augustus II the Strong (12 May 1670 – 1 February 1733), was Elector of Saxony from 1694 as well as King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1697 to 1706 and from 1709 until his death in 1733. He belonged to the Albertine branch of the H ...

in Dresden

Dresden (; ; Upper Saxon German, Upper Saxon: ''Dräsdn''; , ) is the capital city of the States of Germany, German state of Saxony and its second most populous city after Leipzig. It is the List of cities in Germany by population, 12th most p ...

, and in that capacity he built several devices that reproduced some of the successes of Bessler's public demonstrations, including the locked-room test, but which Gärtner acknowledged as mere trickery.

In November 1727, Bessler's maid, Anne Rosine Mauersbergerin, ran away from Bessler's household and testified under oath that she had turned the machines manually from an adjoining room, alternating in that job with Bessler's wife, his brother Gottfried, and Bessler himself. 's Gravesande refused to accept the maid's testimony, writing that he paid "little attention to what a servant can say about machines". By then, 's Gravesande was embroiled in an academic dispute with members of Isaac Newton's circle about the possibility of gravity-powered perpetual motion, which 's Gravesande persistently defended based partly on his belief that Bessler, though "mad", was not a fraud.

The consensus view of modern scientists is that Bessler was perpetrating a deliberate fraud, though just how his wheel was powered is not entirely clear. According to the writers of ''Chambers's Encyclopaedia

''Chambers's Encyclopaedia'' was founded in 1859Chambers, W. & R"Concluding Notice"in ''Chambers's Encyclopaedia''. London: W. & R. Chambers, 1868, Vol. 10, pp. v–viii. by William and Robert Chambers of Edinburgh and became one of the most ...

'', Orffyreus's wheel, "but for its strange effect on 's Gravesande, would have been forgotten long ago"., ''Chambers's encyclopædia: a dictionary of universal knowledge'', vol. 7, (London: W. and R. Chambers, 1868), pp. 412-415. If the maid's confession were true, the testimonies by Prince Karl, 's Gravesande, and others about the conditions under which the wheel was tested and exhibited must be flawed.

References

External links

* List of works and e-texts at de.wikisource {{DEFAULTSORT:Bessler, Johann 1680s births 1745 deaths 18th-century German businesspeople 18th-century German inventors Perpetual motion