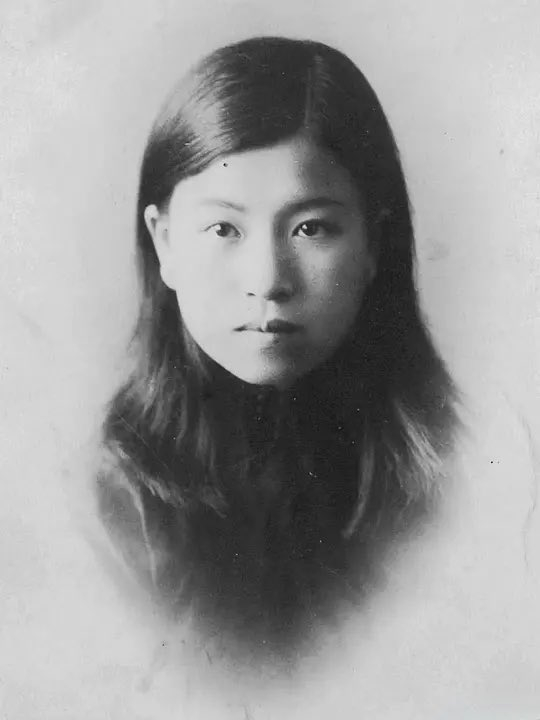

Jiang Qing (March 191414 May 1991), also known as Madame Mao, was a Chinese

communist

Communism () is a sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology within the socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a socioeconomic order centered on common ownership of the means of production, di ...

revolutionary

A revolutionary is a person who either participates in, or advocates for, a revolution. The term ''revolutionary'' can also be used as an adjective to describe something producing a major and sudden impact on society.

Definition

The term—bot ...

, actress, and political figure. She was the fourth wife of

Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; traditionally Romanization of Chinese, romanised as Mao Tse-tung. (26December 18939September 1976) was a Chinese politician, revolutionary, and political theorist who founded the People's Republic of China (PRC) in ...

, the

Chairman of the Communist Party and

Paramount leader

Paramount leader () is an informal term for the most important Supreme leader, political figure in the China, People's Republic of China (PRC). The paramount leader typically controls the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the People's Liberatio ...

of

China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

. Jiang was best known for playing a major role in the

Cultural Revolution

The Cultural Revolution, formally known as the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, was a Social movement, sociopolitical movement in the China, People's Republic of China (PRC). It was launched by Mao Zedong in 1966 and lasted until his de ...

as the leader of the radical

Gang of Four.

Born into a declining family with an

abusive father and a mother who worked as a

domestic servant and sometimes a

prostitute

Prostitution is a type of sex work that involves engaging in sexual activity in exchange for payment. The definition of "sexual activity" varies, and is often defined as an activity requiring physical contact (e.g., sexual intercourse, non-pe ...

, Jiang Qing became a renowned

actress

An actor (masculine/gender-neutral), or actress (feminine), is a person who portrays a character in a production. The actor performs "in the flesh" in the traditional medium of the theatre or in modern media such as film, radio, and television. ...

in

Shanghai

Shanghai, Shanghainese: , Standard Chinese pronunciation: is a direct-administered municipality and the most populous urban area in China. The city is located on the Chinese shoreline on the southern estuary of the Yangtze River, with the ...

, and later the wife of Mao Zedong in

Yan'an

Yan'an; ; Chinese postal romanization, alternatively spelled as Yenan is a prefecture-level city in the Shaanbei region of Shaanxi Province of China, province, China, bordering Shanxi to the east and Gansu to the west. It administers several c ...

, in the 1930s. In the 1940s, she worked as Mao Zedong's

personal secretary, and during the 1950s, she headed the Film Section of the

Publicity Department of the

Chinese Communist Party

The Communist Party of China (CPC), also translated into English as Chinese Communist Party (CCP), is the founding and One-party state, sole ruling party of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Founded in 1921, the CCP emerged victorious in the ...

(CCP).

Appointed deputy director of the

Central Cultural Revolution Group in 1966, Jiang played a pivotal role as Mao's emissary during the early stages of the

Cultural Revolution

The Cultural Revolution, formally known as the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, was a Social movement, sociopolitical movement in the China, People's Republic of China (PRC). It was launched by Mao Zedong in 1966 and lasted until his de ...

. Collaborating with

Lin Biao, she advanced Mao's ideology and promoted

his cult of personality. Jiang wielded considerable influence over state affairs, particularly in culture and the arts. Propaganda posters

idolised her as the "Great Flagbearer of the

Proletarian Revolution

A proletarian revolution or proletariat revolution is a social revolution in which the working class attempts to overthrow the bourgeoisie and change the previous political system. Proletarian revolutions are generally advocated by socialist ...

." In 1969, she secured a seat on the

Politburo

A politburo () or political bureau is the highest organ of the central committee in communist parties. The term is also sometimes used to refer to similar organs in socialist and Islamist parties, such as the UK Labour Party's NEC or the Poli ...

, cementing her power.

Following Mao's death, she was soon

arrested

An arrest is the act of apprehending and taking a person into custody (legal protection or control), usually because the person has been suspected of or observed committing a crime. After being taken into custody, the person can be Interroga ...

by

Hua Guofeng and his allies in 1976.

State media portrayed her as the "

White-Boned Demon," and she was widely blamed for instigating the Cultural Revolution, a period of upheaval that caused the deaths of hundreds of thousands of Chinese people. Initially sentenced to

death with a two-year reprieve in a

televised trial, Jiang's sentence was

commuted to

life imprisonment

Life imprisonment is any sentence (law), sentence of imprisonment under which the convicted individual is to remain incarcerated for the rest of their natural life (or until pardoned or commuted to a fixed term). Crimes that result in life impr ...

in 1983.

Released for medical treatment in the early 1990s, she committed

suicide

Suicide is the act of intentionally causing one's own death.

Risk factors for suicide include mental disorders, physical disorders, and substance abuse. Some suicides are impulsive acts driven by stress (such as from financial or ac ...

in May 1991.

Names

Chinese names

Jiang Qing was known by various names throughout her life. Before her birth, her father named the baby Li Jinnan, where Jinnan means the "coming boy." When she was born, her father changed the name to Li Jinhai, meaning the "coming child."

Therefore, Jiang Qing also called herself Li Jin.

Several other sources indicate her birth name Li Shumeng,

which means "pure and simple."

She adopted the name Li Yunhe during primary school.

She told her

biographer

Biographers are authors who write an account of another person's life, while autobiographers are authors who write their own biography.

Biographers

Countries of working life: Ab=Arabia, AG=Ancient Greece, Al=Australia, Am=Armenian, AR=Ancient Rome ...

Roxane Witke that she liked the name because "Yunhe," meaning "

crane in the cloud," sounded beautiful. In July 1933, during her first visit to Shanghai, she assumed the name Li He and worked as a teacher for local workers. On her second visit to Shanghai in June 1934, she used the alias Zhang Shuzhen. Later, when detained by the

Nationalist government

The Nationalist government, officially the National Government of the Republic of China, refers to the government of the Republic of China (1912–1949), Republic of China from 1 July 1925 to 20 May 1948, led by the nationalist Kuomintang (KMT ...

in October 1934, she identified herself as Li Yungu.

In 1935, when she entered the entertainment industry, she took on the

stage name

A stage name or professional name is a pseudonym used by performers, authors, and entertainers—such as actors, comedians, singers, and musicians. The equivalent concept among writers is called a ''nom de plume'' (pen name). Some performers ...

Lan Ping, which means "blue apple". Although the name had no particular meaning, its bluntness made it unique. However, Jiang Qing did not favour this name due to its association with her scandals in Shanghai. She became known as Jiang Qing upon arriving in

Yan'an

Yan'an; ; Chinese postal romanization, alternatively spelled as Yenan is a prefecture-level city in the Shaanbei region of Shaanxi Province of China, province, China, bordering Shanxi to the east and Gansu to the west. It administers several c ...

, where ''Jiang'' means ''river'' and ''Qing'' means ''

azure'' or "better than blue".

In 1991, when she was hospitalised in Beijing, she used the name Li Runqing. When she died in Beijing, her body was labelled with the

pseudonym

A pseudonym (; ) or alias () is a fictitious name that a person assumes for a particular purpose, which differs from their original or true meaning ( orthonym). This also differs from a new name that entirely or legally replaces an individual's o ...

Li Zi. In March 2002, she was buried in Beijing by her

school name Li Yunhe.

English names

In English, many contemporary articles used the

Wade–Giles

Wade–Giles ( ) is a romanization system for Mandarin Chinese. It developed from the system produced by Thomas Francis Wade during the mid-19th century, and was given completed form with Herbert Giles's '' A Chinese–English Dictionary'' ...

romanisation system to spell Chinese names. For this reason, some sources – especially older ones – spell her name "Chiang Ch'ing", while newer sources use

Pinyin

Hanyu Pinyin, or simply pinyin, officially the Chinese Phonetic Alphabet, is the most common romanization system for Standard Chinese. ''Hanyu'' () literally means 'Han Chinese, Han language'—that is, the Chinese language—while ''pinyin' ...

and spell her name "Jiang Qing". She was also known as Madame Mao, as the wife and widow of Mao Zedong. Yet, the Chinese usually keep their

maiden name after getting married, so her surname remains unchanged in Chinese.

Early life

Jiang Qing was born in

Zhucheng,

Shandong

Shandong is a coastal Provinces of China, province in East China. Shandong has played a major role in Chinese history since the beginning of Chinese civilization along the lower reaches of the Yellow River. It has served as a pivotal cultural ...

, in March 1914. She deliberately kept her exact birth date private to avoid receiving any gifts. Her father was Li Dewen, a carpenter, and her mother, whose name is unknown, was Li's subsidiary wife, or

concubine

Concubinage is an interpersonal relationship, interpersonal and Intimate relationship, sexual relationship between two people in which the couple does not want to, or cannot, enter into a full marriage. Concubinage and marriage are often regarde ...

. Her father had his own carpentry and cabinet making workshop.

Her parents were married after her father initially found his first wife unable to

conceive.

As a child, Jiang was deeply traumatised by the

domestic violence

Domestic violence is violence that occurs in a domestic setting, such as in a marriage

Marriage, also called matrimony or wedlock, is a culturally and often legally recognised union between people called spouses. It establishes r ...

inflicted by her father, who verbally and physically abused her mother almost every day. One

Lantern Festival

The Lantern Festival ( zh, t=wikt:元宵節, 元宵節, s=wikt:元宵节, 元宵节, first=t, hp=Yuánxiāo jié), also called Shangyuan Festival ( zh, t=上元節, s=上元节, first=t, hp=Shàngyuán jié) and Cap Go Meh ( zh, t=十五暝, ...

, after her father broke her mother's finger during an attack, her mother fled with Jiang under the cover of darkness. Her mother found work as a domestic servant that often blurred the lines with prostitution, and her husband separated from her.

Jiang eventually moved with her mother to her grandparents' home in Jinan. However, they soon returned to Zhucheng, as her mother continued to seek

inheritance rights, or financial support, from her husband's family, which proved extremely difficult. During this period, Jiang attended two primary schools with disruptions, where she was often mocked for wearing outdated, boyish clothing from her brothers. She became silent and not easy to open up.

Her mother, having fallen ill, eventually abandoned hope of obtaining further financial support from her husband. After selling some of her belongings, she purchased a train ticket, and together with Jiang, boarded a train from

Jiaoxian to

Jinan

Jinan is the capital of the province of Shandong in East China. With a population of 9.2 million, it is one of the largest cities in Shandong in terms of population. The area of present-day Jinan has played an important role in the history of ...

. There, Jiang was welcomed by her grandparents and resumed her primary education. In 1926–1927, her mother took her further north to Tianjin to stay with her half-sister. During this time, Jiang worked as a housekeeper in the household. She proposed taking a job rolling cigarettes, but the family disapproved. Later they returned to Jinan, where her mother died in 1928.

Entertainment career

Jinan

At 14, Jiang, now an orphan, joined a local underground theatre troupe, seeking independence. Her striking looks drew attention, but she remained sensitive about her poor upbringing. Alarmed by her undisclosed departure, her grandparents paid the troupe's boss to bring her back. She enrolled in the Experimental Arts Academy, which became less picky about the social class of new entrants due to the

May Fourth Movement

The May Fourth Movement was a Chinese cultural and anti-imperialist political movement which grew out of student protests in Beijing on May 4, 1919. Students gathered in front of Tiananmen to protest the Chinese government's weak response ...

. Despite her strong Shandong accent initially hindering her performances, she excelled during her year of training, in some traditional opera roles. When the academy closed in 1930, Jiang, though only half-trained, was chosen to join theatrical companies in

Beijing

Beijing, Chinese postal romanization, previously romanized as Peking, is the capital city of China. With more than 22 million residents, it is the world's List of national capitals by population, most populous national capital city as well as ...

. She returned to Jinan in May 1931 and married Pei Minglun,; According to the ''Revised Mandarin Chinese Dictionary'' by the

Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia. The main geography of Taiwan, island of Taiwan, also known as ''Formosa'', lies between the East China Sea, East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocea ...

ese

Ministry of Education

An education ministry is a national or subnational government agency politically responsible for education. Various other names are commonly used to identify such agencies, such as Ministry of Education, Department of Education, and Ministry of Pub ...

, the surname is pronounced Péi. However,

Hong Kong

Hong Kong)., Legally Hong Kong, China in international treaties and organizations. is a special administrative region of China. With 7.5 million residents in a territory, Hong Kong is the fourth most densely populated region in the wor ...

's Multi-function Chinese Character Database notes an additional pronunciation as Féi. (pp. 29–31) adopts the translation Fei. the wealthy son of a businessman, and soon divorced.

Qingdao

Following her divorce, Jiang reached out to

Zhao Taimou, the former director of the Arts Academy and dean of

Qingdao University. With the assistance of Zhao's wife,

Yu Shan

Yu Shan or Yushan, also known as Mount Jade, Jade Mountain, Tongku Saveq or Mount Niitaka during Taiwan under Japanese rule, Japanese rule, is the highest mountain in Taiwan at above sea level, giving Taiwan the List of islands by highest ...

, Jiang secured a position as a clerk in the university library. Yu Shan later introduced Jiang to her brother,

Yu Qiwei, an upper-class youth who had embraced the Communist cause and was connected to underground Communist organisations as well as literary and performing arts circles.

The

Mukden Incident in September ignited her

patriotism

Patriotism is the feeling of love, devotion, and a sense of attachment to one's country or state. This attachment can be a combination of different feelings for things such as the language of one's homeland, and its ethnic, cultural, politic ...

, leading her to develop a dislike for the

Kuomintang

The Kuomintang (KMT) is a major political party in the Republic of China (Taiwan). It was the one party state, sole ruling party of the country Republic of China (1912-1949), during its rule from 1927 to 1949 in Mainland China until Retreat ...

and its supporters. By the end of 1932, Jiang and Yu Qiwei fell in love and began living together, enabling Jiang to gain entry into the Communist Cultural Front. She became a member of the Seaside Drama Society, performing in plays such as ''

Lay Down Your Whip'', harnessing the influence of theatre to resist Japanese aggression. In February 1933, she officially joined the CCP.

The Communist activities at Qingdao University attracted significant attention from the Kuomintang's secret police, who arrested Yu Qiwei in July, forcing Jiang to leave Qingdao.

Shanghai

After the arrest of Yu Qiwei, Yu Shan arranged for Jiang to move to Shanghai. With a recommendation from

Tian Han

Tian Han ( zh, 田汉; 12 March 1898 – 10 December 1968), formerly romanized as T'ien Han, was a Chinese drama activist, playwright, a leader of revolutionary music and films, as well as a translator and poet. He emerged at the time of the ...

's younger brother, Tian Luan, she enrolled as a visiting student at the

Great China University in Shanghai. In July, with endorsements from Tian Han and his associates, Jiang became a teacher at the Chengeng Workers' School, an institution organised by

Tao Xingzhi. During this time, Yu Qiwei was released and visited her in Shanghai. In October, Jiang re-joined the Chinese Communist Youth League, became a member of the League of Left-Wing Educators, and resumed her career as a drama actress.

She performed in the Shanghai Work Study Troupe. Jiang was among the cast of a production of ''

Roar, China!'' which British authorities banned from being performed in

Shanghai's International Settlement.

In September 1934, Jiang was arrested and jailed for her political activities in Shanghai.

During her arrest in Shanghai, Jiang Qing was interrogated by a

Zhongtong agent, Zhao Yaoshan. Jiang had once revealed to Zhao that Tan Xiaoqing was a CCP member, leading to Tan's arrest.

She was released three months later, in December.

She then traveled to Beijing where she reunited with Yu Qiwei who had just been released following his prison sentence, and the two began living together again.

She returned to Shanghai in March 1935, and entered

Diantong Film Company. She became famous when featuring in

Ibsen

Henrik Johan Ibsen (; ; 20 March 1828 – 23 May 1906) was a Norwegian playwright, poet and actor. Ibsen is considered the world's pre-eminent dramatist of the 19th century and is often referred to as "the father of modern drama." He pioneered ...

's play ''

A Doll's House

''A Doll's House'' (Danish language, Danish and ; also translated as ''A Doll House'') is a three-act Play (theatre), play written by Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen. It premiered at the Royal Danish Theatre in Copenhagen, Denmark, on 21 De ...

'' as Nora. She later became an actress in ''

Goddess of Freedom'' and ''

Scenes of City Life'', during which she fell in love with

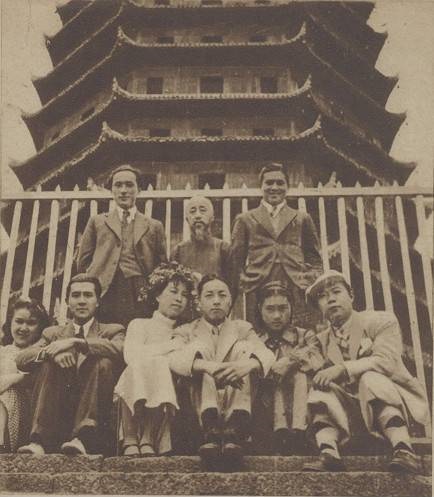

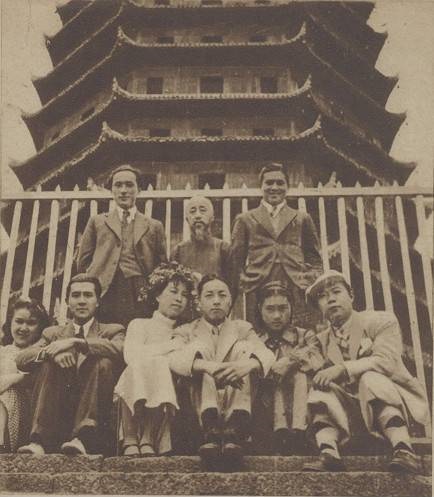

Tang Na, her colleague at Diantong. The two began living together in September 1935. However, Jiang lied to Tang, claiming her mother was ill, and returned to Tianjin to see Yu Qiwei. When Tang discovered the truth, he attempted suicide in Jinan but later reconciled with Jiang and returned with her to Shanghai in July 1935. Later they were married in a collective wedding ceremony at

Liuhe Pagoda in

Hangzhou

Hangzhou, , Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ; formerly romanized as Hangchow is a sub-provincial city in East China and the capital of Zhejiang province. With a population of 13 million, the municipality comprises ten districts, two counti ...

in April 1936.

In Shanghai, Jiang joined

Lianhua Film Company

The United Photoplay Service Company () was one of the three dominant production companies based in Shanghai, China during the 1930s, the other two being the Mingxing Film Company and the Tianyi Film Company, the forerunner of the Hong Kong–ba ...

, where she acted in ''

Blood on Wolf Mountain'' and ''

Lianhua Symphony''. During this period, she began an affair with film director Zhang Min, appeared in his production ''The Storm''. She also became an actress in ''

Wang Laowu''. However, during the second performance of ''

The Storm'' in May 1937, Tang attempted suicide again. Following this incident, Jiang divorced Tang and started living with Zhang Min, but the relationship cost her career as she was dismissed by Lianhua Film Company.

Jiang's widely publicised affair with Tang Na tarnished her reputation, making it difficult for her to continue her acting career in Shanghai.

Like many youths of her time, she was drawn to the

progressive ideals associated with

Yan'an

Yan'an; ; Chinese postal romanization, alternatively spelled as Yenan is a prefecture-level city in the Shaanbei region of Shaanxi Province of China, province, China, bordering Shanxi to the east and Gansu to the west. It administers several c ...

. The

Marco Polo Bridge Incident in July 1937, which marked the start of Japan's full-scale invasion of China, further galvanised young activists to advocate for a

united front

A united front is an alliance of groups against their common enemies, figuratively evoking unification of previously separate geographic fronts or unification of previously separate armies into a front. The name often refers to a political and/ ...

. Yan'an, promoted through

Communist propaganda, emerged as a symbol of democracy, freedom, and hope.

She left Shanghai in July, after which the Japanese invasion in Shanghai started on 13 August.

Early political activities

Yan'an

Drama teacher

She went first to

Xi'an

Xi'an is the list of capitals in China, capital of the Chinese province of Shaanxi. A sub-provincial city on the Guanzhong plain, the city is the third-most populous city in Western China after Chongqing and Chengdu, as well as the most populou ...

, then to

Yan'an

Yan'an; ; Chinese postal romanization, alternatively spelled as Yenan is a prefecture-level city in the Shaanbei region of Shaanxi Province of China, province, China, bordering Shanxi to the east and Gansu to the west. It administers several c ...

. In November, she enrolled in the

Counter-Japanese Military and Political University for study. The

Lu Xun Academy of Arts was newly founded in Yan'an on 10 April 1938, and Jiang became a drama department instructor, teaching and performing in college plays and

operas

Opera is a form of Western theatre in which music is a fundamental component and dramatic roles are taken by singers. Such a "work" (the literal translation of the Italian word "opera") is typically a collaboration between a composer and a li ...

.

The conditions in Yan'an were harsh, but Jiang was able to make it there and persist. Jiang was striking in appearance and had several talents; she could sing opera, write well, and her calligraphy was particularly impressive, especially in

regular script

The regular script is the newest of the major Chinese script styles, emerging during the Three Kingdoms period , and stylistically mature by the 7th century. It is the most common style used in modern text. In its traditional form it is the t ...

. On one hand, she was relatively quiet and reserved—she didn't enjoy shooting, but liked playing poker, knitting, and was skilled at creating various patterns. She was also adept at tailoring and made her own clothes beautifully. On the other hand, she had a lively and bold side—Jiang enjoyed horseback riding, especially taming wild horses; the more ferocious the horse, the more she liked to ride it. This combination of traits allowed her to excel as both a homemaker and adapt to the tough, military lifestyle, earning the admiration of revolutionary leaders.

Secret marriage

In the autumn of 1937,

He Zizhen, the wife of Mao Zedong, left Yan'an. When news of Jiang Qing's romance with Mao Zedong broke, it sparked significant opposition. The most vocal critic was

Zhang Wentian, who believed that He, as an outstanding CCP member, having endured the

Long March

The Long March ( zh, s=长征, p=Chángzhēng, l=Long Expedition) was a military retreat by the Chinese Red Army and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) from advancing Kuomintang forces during the Chinese Civil War, occurring between October 1934 and ...

and sustained multiple injuries, deserved respect. However, some felt that Mao Zedong's personal matters, including his choice of a wife, were his own business, and others should not interfere. Among those who supported Mao, the most vocal was

Kang Sheng

Kang Sheng (; 4 November 1898 – 16 December 1975), born Zhang Zongke (), was a Chinese Communist Party (CCP) official, politician and calligrapher best known for having overseen the work of the CCP's internal security and intelligence appara ...

.

Figures like

Zhou Enlai

Zhou Enlai ( zh, s=周恩来, p=Zhōu Ēnlái, w=Chou1 Ên1-lai2; 5 March 1898 – 8 January 1976) was a Chinese statesman, diplomat, and revolutionary who served as the first Premier of the People's Republic of China from September 1954 unti ...

and

Liu Shaoqi

Liu Shaoqi ( ; 24 November 189812 November 1969) was a Chinese revolutionary and politician. He was the chairman of the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress from 1954 to 1959, first-ranking Vice Chairman of the Chinese Communis ...

, however, were more cautious in their support of Jiang Qing. They sent telegrams to the Communist leadership in Shanghai, requesting them to clarify Jiang's conduct in Shanghai, where she was suspected of being a "secret agent" of the Kuomintang.

, a party leader in Shanghai, secretly written to Yan'an arguing that Jiang was unsuitable for marriage to Mao.

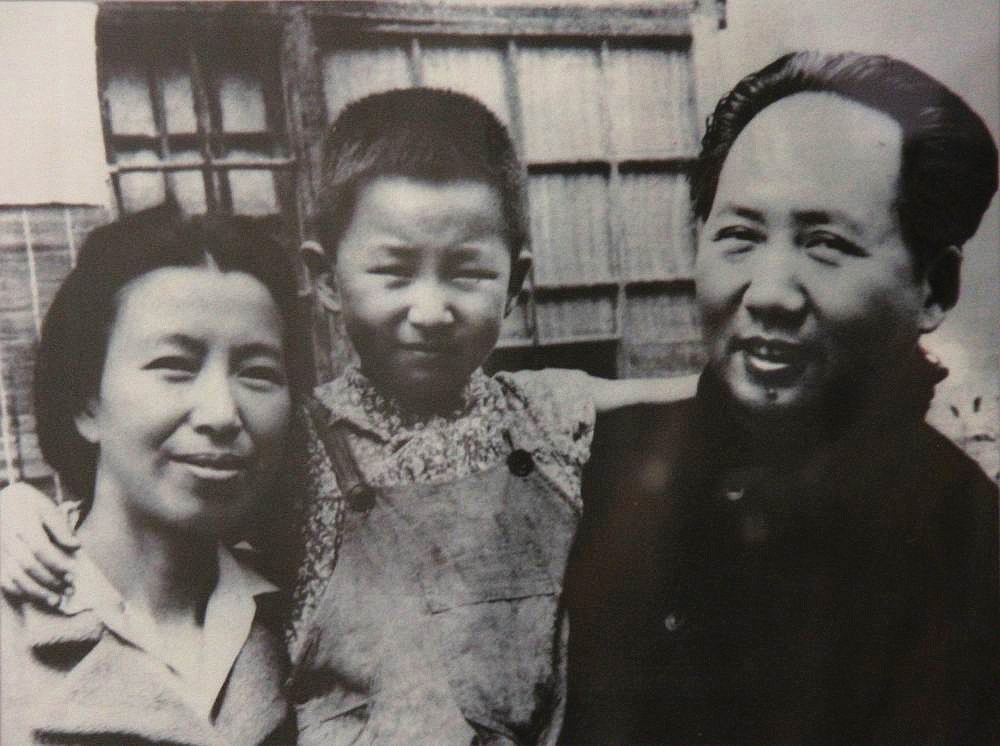

Nevertheless, on 28 November 1938, Jiang Qing married Mao Zedong with the eventual approval of the

Politburo

A politburo () or political bureau is the highest organ of the central committee in communist parties. The term is also sometimes used to refer to similar organs in socialist and Islamist parties, such as the UK Labour Party's NEC or the Poli ...

, but with three restrictions as follows:

# Since Mao and He Zizhen had not formally

dissolved their marriage, Jiang Qing was prohibited from publicly assuming the title of Mao Zedong's wife.

# Jiang Qing was tasked solely with caring for Mao Zedong's daily life and health, and no one else could make similar requests to the

Party Central Committee.

# Jiang Qing was restricted to managing Mao's private affairs. She was barred from holding any Party positions for 20 years and was prohibited from interfering in Party personnel matters or participating in political activities.

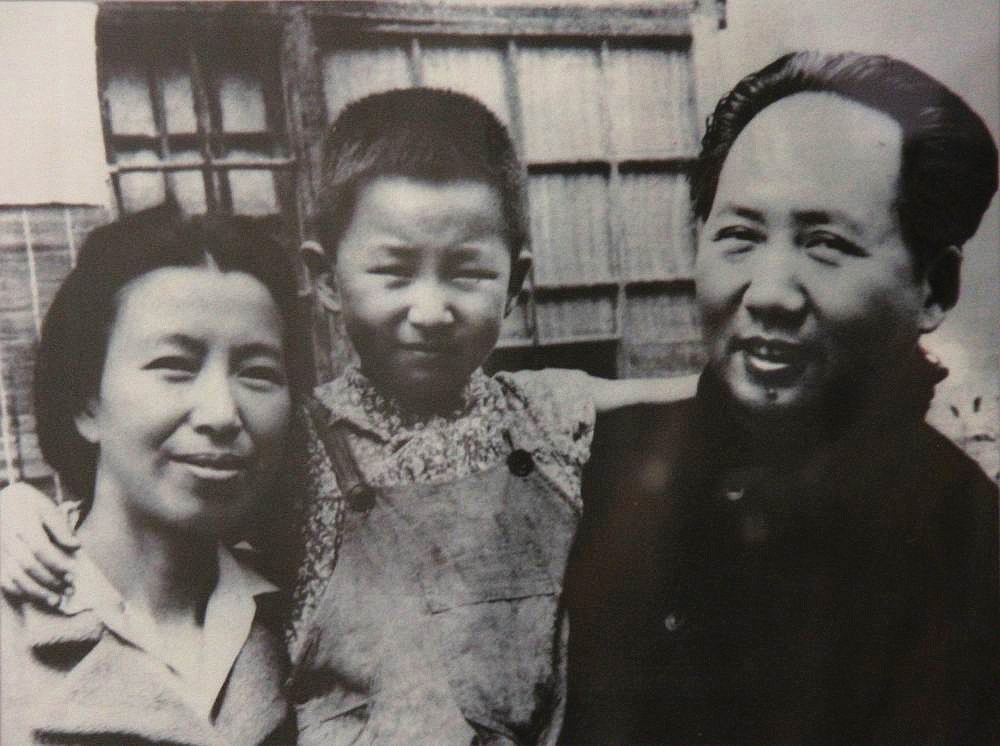

In the early years of their marriage, Mao Zedong and Jiang Qing shared a harmonious life. Jiang primarily took on the role of a homemaker, attending to Mao's daily needs. In 1940, she gave birth to their daughter,

Li Na. After Li Na's birth, Jiang Qing largely withdrew from the public eye.

Beijing and Moscow

First Lady

After the founding of the

People's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

in 1949, Jiang Qing became the nation's first lady. However, her role was concealed from the general public in China or beyond throughout the 1950s. During the 1950s, Jiang Qing left a generally favourable impression on those who interacted with her.

In 1949, after

Soong Ching-ling attended the founding ceremony in Beijing and returned to Shanghai, Mao Zedong sent Jiang Qing to see her off at the train station. It is said that Soong later remarked that Jiang was "polite and likeable." In 1956, Soong hosted

Indonesian President Sukarno

Sukarno (6 June 1901 – 21 June 1970) was an Indonesian statesman, orator, revolutionary, and nationalist who was the first president of Indonesia, serving from 1945 to 1967.

Sukarno was the leader of the Indonesian struggle for independenc ...

at a banquet in Shanghai, where Jiang and

Liu Shaoqi

Liu Shaoqi ( ; 24 November 189812 November 1969) was a Chinese revolutionary and politician. He was the chairman of the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress from 1954 to 1959, first-ranking Vice Chairman of the Chinese Communis ...

’s wife,

Wang Guangmei, were also present. Soong reportedly praised Jiang for her refined manners and tasteful attire. During their conversation, Jiang even asked Soong to encourage Mao to wear a

tie and suits, noting that

Sun Yat-sen

Sun Yat-senUsually known as Sun Zhongshan () in Chinese; also known by Names of Sun Yat-sen, several other names. (; 12 November 186612 March 1925) was a Chinese physician, revolutionary, statesman, and political philosopher who founded the Republ ...

often did so and suggesting that foreigners found the simplicity of Chinese officials' clothing too monotonous.

Film bureaucracy

She served as the deputy director of the

Film Guidance Committee, overseeing the evaluation of film projects from 1949 to 1951. In 1951, Jiang Qing was given a minor position of Film Bureau Chief. After her appointment, Jiang engaged in three attempts in establishing the standard for socialist art. Jiang's first attempt was her advice to ban the 1950

Hong Kong movie ''

Sorrows of the Forbidden City'', of which Jiang believed to be unpatriotic. Her opinion was not taken seriously by the communist leadership due to the minor political influence of her office and the movie was distributed in major cities like Beijing and Shanghai. Mao intervened to support her.

Later that year, Jiang critiqued and objected to the distribution of the movie ''

The Life of Wu Xun'' for glorifying the wealthy landed class while dismissing the peasantry. Again, Jiang's opinion was dismissed. Mao had to intervene to support her again.

Jiang's third attempt involved the role of literary criticism in the development of socialist art. She asked the editor of ''

People's Daily

The ''People's Daily'' ( zh, s=人民日报, p=Rénmín Rìbào) is the official newspaper of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). It provides direct information on the policies and viewpoints of the CCP in multiple lan ...

'' to republish the new literary interpretation of the classic novel ''

Dream of Red Mansions'' by two young scholars at Shandong University. The editor refused Jiang's request on the grounds that the party newspaper was not a forum for free debate. Again, Mao spoke up on Jiang's behalf.

Jiang was a member of the Ministry of Culture's steering committee for film production.

Medical treatment

Jiang was in poor health for much of the 1950s, leading her to step back from her official duties. As a result, she had to move back and forth between Beijing and

Moscow

Moscow is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Russia by population, largest city of Russia, standing on the Moskva (river), Moskva River in Central Russia. It has a population estimated at over 13 million residents with ...

. In 1949, she was diagnosed with cervical cancer and underwent four rounds of treatment in the Soviet Union.

In March 1949, she travelled to Moscow and

Yalta

Yalta (: ) is a resort town, resort city on the south coast of the Crimean Peninsula surrounded by the Black Sea. It serves as the administrative center of Yalta Municipality, one of the regions within Crimea. Yalta, along with the rest of Crime ...

, returning in the autumn. She visited Moscow again in 1952, staying until the autumn of 1953. Due to severe pain in her liver, while the Chinese doctors were unable to fulfil their duties due to the

Three-Antis Movement, the Soviet doctors explored her liver through surgery. Her life in the Soviet Union was rather reclusive, with only Russian doctors, nurses, bodyguards, and all reading materials only from the

Chinese diplomatic mission. In 1956, she made another trip to the Soviet Union for treatment and returned in 1957.

During this period, as a foreign dignitary, she gained access to a wide range of films banned in the

Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

, including many

Hollywood productions. This exposure allowed her to stay informed about Western art trends, which later influenced her transformation of the

Peking Opera

Peking opera, or Beijing opera (), is the most dominant form of Chinese opera, which combines instrumental music, vocal performance, mime, martial arts, dance and acrobatics. It arose in Beijing in the mid-Qing dynasty (1644–1912) and became ...

.

In 1957, Jiang recovered from cervical cancer, though she believed she was still unwell, contrary to her doctors’ assessment of her good health. Therefore, they recommended that she engage in therapeutic activities such as watching films, listening to music, and attending theatre and concerts.

Cover-up

During the

Campaign to Suppress Counterrevolutionaries, Zhao Yaoshan, the

Zhongtong agent who interrogated Jiang during her arrest in the 1930s, was executed.

In January 1953, , who had secretly written to Yan'an about Jiang's experiences in Shanghai, was imprisoned.

Pan Hannian, the Communist intelligence chief who defended Yang, was also jailed.

In December, Mao Zedong travelled to

Hangzhou

Hangzhou, , Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ; formerly romanized as Hangchow is a sub-provincial city in East China and the capital of Zhejiang province. With a population of 13 million, the municipality comprises ten districts, two counti ...

with Jiang Qing. After his departure on 14 March, Jiang received an anonymous letter from Shanghai later that month. Initially disturbed and then angered, she sought out Zhejiang party chief

Tan Qilong, asserting her revolutionary commitment and requesting an investigation. Despite extensive police efforts, the sender's identity remained unknown.

In 1958, while Mao attended a meeting in

Nanning

Nanning; is the capital of the Guangxi, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region in South China, southern China. It is known as the "Green City (绿城) " because of its abundance of lush subtropical foliage. Located in the South of Guangxi, Nanning ...

, he met

Yu Qiwei, who had a

romantic relationship

Romance or romantic love is a feeling of love for, or a strong attraction towards another person, and the courtship behaviors undertaken by an individual to express those overall feelings and resultant emotions.

The ''Wiley Blackwell En ...

with Jiang. After being criticised by Mao, Yu suffered severe mental and physical distress. Upon arriving at

Guangzhou Airport, he

kowtow

A kowtow () is the act of deep respect shown by prostration, that is, kneeling and bowing so low as to have one's head touching the ground. In East Asian cultural sphere, Sinospheric culture, the kowtow is the highest sign of reverence. It w ...

ed before

Li Fuchun, pleading to be "spared." Li then escorted him to a military hospital. There, Yu attempted suicide by jumping out of a window, resulting in a broken leg. Yu died a few months later, and Mao sent a

wreath in his name alone as a gesture of condolence.

In 1961, Zhu Ming, the widow of

Lin Boqu, wrote to the Party Central Committee regarding her late husband. Her handwriting matched that of the anonymous letter. When confronted, Zhu admitted to writing the letter and subsequently committed suicide.

Cultural Revolution

Prelude

Before 1962, the Chinese media never mentioned who Mao Zedong's wife was in its international propaganda. People close to Mao Zedong claimed that after the 1950s, Jiang Qing was rarely seen by his side, and their emotional relationship had essentially ended, leaving her feeling frustrated for a time. However, as the 1960s progressed, Mao became increasingly distrustful of the surrounding leaders and his judgment of the domestic political situation grew more severe. Jiang Qing capitalised on this shift, becoming more outspoken, which led Mao to view her as "politically sensitive" and start to trust her. As a result, her power grew steadily.

After Jiang's return to China in 1962, she frequently attended local opera performances.

In 1963, Jiang Qing enlisted A Jia to help modernise Beijing Opera with revolutionary socialist themes. She later instructed the

Beijing Municipal Opera Company to create ''

Shajiabang'', depicting the struggle between the Kuomintang and Communists during the

Second Sino-Japanese War

The Second Sino-Japanese War was fought between the Republic of China (1912–1949), Republic of China and the Empire of Japan between 1937 and 1945, following a period of war localized to Manchuria that started in 1931. It is considered part ...

, and tasked the

Shanghai Beijing Opera Company with producing ''

Taking Tiger Mountain by Strategy''.

In her first public speech in June 1964 at a

Peking Opera

Peking opera, or Beijing opera (), is the most dominant form of Chinese opera, which combines instrumental music, vocal performance, mime, martial arts, dance and acrobatics. It arose in Beijing in the mid-Qing dynasty (1644–1912) and became ...

convention, Jiang criticised regional opera troupes for glorifying emperors, generals, scholars, and other

ox-demons and snake-spirits.

Jiang's efforts to reform

Peking Opera

Peking opera, or Beijing opera (), is the most dominant form of Chinese opera, which combines instrumental music, vocal performance, mime, martial arts, dance and acrobatics. It arose in Beijing in the mid-Qing dynasty (1644–1912) and became ...

gained approval from the Communist leadership, especially during the 1964 Modern Beijing Opera Trial Performance Convention. She also formed a productive collaboration with

Yu Huiyong, to push the

yangbanxi (model drama) projects. Their shared vision focused on creating operas that reflected modern Chinese society and the lives of the working class, starting with ''

On the Docks'', which portrayed Communist-ruled Shanghai. Jiang's political influence helped ensure the success of these projects, which aimed to create revolutionary art that represented the reality of contemporary life.

Cultural reforms

From 1962 onwards, Jiang Qing began appearing publicly as Mao's wife and later gave frequent speeches in the cultural and propaganda sectors, criticizing and condemning various figures.

By late 1965, as Jiang Qing's influence grew, she rallied close allies such as

Zhang Chunqiao

Zhang Chunqiao (; 1 February 1917 – 21 April 2005) was a Chinese political theorist, writer, and politician. He came to the national spotlight during the late stages of the Cultural Revolution, and was a member of the ultra-Maoist group dub ...

and

Yao Wenyuan.

She organised a campaign to criticise the play ''

Hai Rui Dismissed from Office

''Hai Rui Dismissed from Office'' (; also called ''Dismissal of Hai Jui'' in English) is a stage play, written by Wu Han (1909–1969), notable for its involvement in Chinese politics during the Cultural Revolution. The play itself focused on ...

'', which marked the beginning of the Cultural Revolution.

In February 1966, Jiang hosted a forum with

PLA officers. The group studied writings by Mao, watched films and plays, and met with the cast and crew of an in-progress film production. The forum concluded that a "black line" of

bourgeois

The bourgeoisie ( , ) are a class of business owners, merchants and wealthy people, in general, which emerged in the Late Middle Ages, originally as a "middle class" between the peasantry and Aristocracy (class), aristocracy. They are tradition ...

thought dominated the arts since the PRC's founding. A summary of Jiang's analysis at the forum was later distributed widely during the Cultural Revolution and became a significant document.

Over April through June 1966, Jiang presided over the All-Army Artistic Creation Conference in Beijing. Conference attendees evaluated a total of 80 domestic and foreign films. Jiang approved of 7 as consistent with

Mao Zedong Thought

Maoism, officially Mao Zedong Thought, is a variety of Marxism–Leninism that Mao Zedong developed while trying to realize a socialist revolution in the agricultural, pre-industrial society of the Republic of China and later the People's Re ...

and criticised the other films. Backed by her husband, she was appointed deputy director of the

Central Cultural Revolution Group (CCRG) in 1966 and emerged as a serious political figure in the summer of that year.

Revolutionary operas

In 1967, at the beginning of the

Cultural Revolution

The Cultural Revolution, formally known as the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, was a Social movement, sociopolitical movement in the China, People's Republic of China (PRC). It was launched by Mao Zedong in 1966 and lasted until his de ...

, Jiang declared eight works of performance art to be the new models for proletarian literature and art. These "model operas", or "

revolutionary operas", were designed to glorify Mao Zedong, The People's Liberation Army, and the revolutionary struggles. The ballets

''White-Haired Girl'', ''

Red Detachment of Women'', and ''

Shajiabang'' ("Revolutionary Symphonic Music") were included in the list of eight, and were closely associated with Jiang, because of their inclusion of elements from Chinese and Western opera, dance, and music. The Red Guards condemned

Yu Huiyong to be a "bad element" for propagating feudalism through his utilisation of traditional Chinese music in operas. Yu was also tagged as "a democrat hiding under the banner of the Communist Party" due to his frequent absences in party meetings. In 1966, Yu was subsequently sent to a Cow Shed, a small room where the "bad elements" were confined. In October 1966, Yu was released after Jiang requested a meeting with Yu to stage the production of two operas in Beijing. Jiang seated Yu next to her, as a display of Yu's importance in the making of yangbanxi, during the showing of ''Taking Tiger Mountain by Strategy''.

During

Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 until Resignation of Richard Nixon, his resignation in 1974. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican ...

's famous

visit to China in February 1972, he watched ''Red Detachment of Women'', and was impressed by the opera. He famously asked Jiang who the writer, director, and composer were, to which she replied it was "created by the masses."

Fashion designs

In 1974, Jiang Qing directed the

Ministry of Culture Ministry of Culture may refer to:

* Ministry of Tourism, Cultural Affairs, Youth and Sports (Albania)

* Ministry of Culture (Algeria)

* Ministry of Culture (Argentina)

* Minister for the Arts (Australia)

* Ministry of Culture (Azerbaijan)Ministry o ...

to design a new dress for Chinese women, inspired by elements of women's clothing from the

Song dynasty

The Song dynasty ( ) was an Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 960 to 1279. The dynasty was founded by Emperor Taizu of Song, who usurped the throne of the Later Zhou dynasty and went on to conquer the rest of the Fiv ...

. The dress was called the Jiang Qing Dress. The dress featured a symmetrical V-neckline, differing slightly from the traditional Y-shaped neckline of

Hanfu

''Hanfu'' (, lit. "Han Chinese, Han clothing"), also known as ''Hanzhuang'' (), are the traditional styles of clothing worn by the Han Chinese since the 2nd millennium BCE. There are several representative styles of ''hanfu'', such as the (an ...

. Mockingly dubbed the "Nun's Robe," Jiang intended for female cadres to lead the way in wearing it, with the eventual goal of making it a nationwide standard.

Political activism

During this period, Mao galvanised students and young workers as his paramilitary organisation the

Red Guards

The Red Guards () were a mass, student-led, paramilitary social movement mobilized by Chairman Mao Zedong in 1966 until their abolition in 1968, during the first phase of the Cultural Revolution, which he had instituted.Teiwes

According to a ...

to attack what he termed as

revisionists in the party. Mao told them the revolution was in danger and that they must do all they could to stop the emergence of a

privileged class in China. He argued this is what had happened in the

Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

under

Khrushchev.

With time, Jiang began playing an increasingly active political role in the movement. She took part in most important Party and government activities.

Jiang took advantage of the Cultural Revolution to wreak vengeance on her personal enemies, including people who had slighted her during her acting career in the 1930s. She was supported by a radical coterie, dubbed, by Mao himself, the Gang of Four. She became a prominent member of the Central Cultural Revolution Group and a major player in Chinese politics from 1966 to 1976.

1966–1969

From 1962, Chairman

Liu Shaoqi

Liu Shaoqi ( ; 24 November 189812 November 1969) was a Chinese revolutionary and politician. He was the chairman of the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress from 1954 to 1959, first-ranking Vice Chairman of the Chinese Communis ...

and his wife

Wang Guangmei frequently appeared at diplomatic events, earning Wang the title of "First Lady," which reportedly made Jiang Qing jealous. Before Wang's overseas trips, Jiang advised her not to wear jewellery, claiming it looked better. However, upon seeing Wang on television wearing a necklace, Jiang criticised her for displaying "bourgeois style" in a talk with

Red Guards

The Red Guards () were a mass, student-led, paramilitary social movement mobilized by Chairman Mao Zedong in 1966 until their abolition in 1968, during the first phase of the Cultural Revolution, which he had instituted.Teiwes

According to a ...

.

On 13 December 1966, Liu Shaoqi voluntarily offered to resign from his positions as

President. He proposed moving with his wife and children to Yan’an or his hometown in Hunan to take up farming, hoping to bring the Cultural Revolution to an early conclusion and minimise the damage to the country. On 18 December,

Zhang Chunqiao

Zhang Chunqiao (; 1 February 1917 – 21 April 2005) was a Chinese political theorist, writer, and politician. He came to the national spotlight during the late stages of the Cultural Revolution, and was a member of the ultra-Maoist group dub ...

, deputy head of the Central Cultural Revolution Group, summoned

Kuai Dafu, a leader of the Red Guards at

Tsinghua University

Tsinghua University (THU) is a public university in Haidian, Beijing, China. It is affiliated with and funded by the Ministry of Education of China. The university is part of Project 211, Project 985, and the Double First-Class Constructio ...

, and instructed him to launch a campaign to overthrow Liu Shaoqi. On 25 December, Kuai Dafu led thousands of demonstrators in Tiananmen Square, where they publicly chanted the slogan “Down with Liu Shaoqi.”

The

Central Cultural Revolution Group was initially a small body under the

Standing Committee of the Politburo.

With the backing of Jiang Qing, Zhang Chunqiao and Yao Wenyuan initiated a coup in Shanghai in January 1967, consolidating power and gaining support from revolutionary factions like Wang Hongwen.

On 6 January 1967, Red Guards at Tsinghua University, with Jiang Qing's backing, lured Wang to the campus under the pretext of her daughter being in a car accident. Once there, Wang was detained and prosecuted.

Following the Red Guards' disruption of party structures in January 1967, this group replaced the Secretariat and became the central command for the party. Jiang Qing's role as the "First Deputy Head" of the group grew significantly, elevating her political power.

Chen Boda

Chen Boda (; 29 July 1904 – 20 September 1989), was a Chinese Communist journalist, professor and political theorist who rose to power as the chief interpreter of Maoism (or "Mao Zedong Thought") in the first 20 years of the People's Republi ...

, the nominal leader of the group, was repeatedly humiliated by Jiang Qing during this period. Fearing her power, he endured her mistreatment in silence. In one notable incident, after a middle school student scaled his wall, Chen's wife reported the event, sparking a "footprint incident" that enraged Jiang Qing. She demanded Chen move out of Zhongnanhai, and this further strained his relationship with her. Seizing the opportunity, Lin Biao and his wife, Ye Qun, aligned with Chen, who quietly defected to their faction.

On 18 July 1967, a public

struggle session

Struggle sessions (), or denunciation rallies or struggle meetings, were violent public spectacles in Maoist China where people accused of being "Five Black Categories, class enemies" were public humiliation, publicly humiliated, accused, beaten ...

against Liu Shaoqi was held in Zhongnanhai. On 5 August, the Central Cultural Revolution Group approved three separate struggle sessions targeting Liu Shaoqi and his wife, Deng Xiaoping and his wife, and Tao Zhu and his wife. From that point, Liu Shaoqi was completely stripped of his personal freedom. On 16 September 1968, under Jiang Qing's leadership, a special investigation team compiled three volumes of so-called evidence against Liu, largely extracted through torture and coercion. After being imprisoned in Zhongnanhai for over two years, Liu Shaoqi was transferred to Kaifeng, Henan Province, on 17 October 1969, where he subsequently died.

Meanwhile, Jiang's stature continued to rise, though she was still not a member of the Central Committee during the 11th Plenary Session of the 8th Central Committee. At the 9th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party in April 1969, Jiang was admitted to the Politburo after Mao Zedong shifted his stance, likely to balance the power of the Lin Biao faction. Mao also approved the entry of Lin Biao's wife, Ye Qun, into the Politburo, further consolidating their influence.

1969–1971

At the

9th National Congress of the Communist Party, Jiang condemned quotation songs, which had been promoted since September 1966 as mnemonic devices for the study of

''Quotations'' ''from Chairman Mao Zedong''.

Jiang had come to view the popular tunes as akin to

yellow music.

Jiang's rivalry with, and personal dislike of,

Zhou Enlai

Zhou Enlai ( zh, s=周恩来, p=Zhōu Ēnlái, w=Chou1 Ên1-lai2; 5 March 1898 – 8 January 1976) was a Chinese statesman, diplomat, and revolutionary who served as the first Premier of the People's Republic of China from September 1954 unti ...

led Jiang to hurt Zhou where he was most vulnerable. In 1968, Jiang had Zhou's adopted son (Sun Yang) and daughter (

Sun Weishi) tortured and murdered by Red Guards. Sun Yang was murdered in the basement of

Renmin University

The Renmin University of China (RUC) is a public university in Haidian, Beijing, Haidian, Beijing, China. The university is affiliated with the Ministry of Education (China), Ministry of Education, and co-funded by the Ministry of Education and ...

. After Sun Weishi died following seven months of torture in a

secret prison (at Jiang's direction), Jiang made sure that Sun's body was cremated and disposed of so that no autopsy could be performed and Sun's family could not have her ashes. In 1968, Jiang forced Zhou to sign an arrest warrant for his own brother. In 1973 and 1974, Jiang directed the "Criticise Lin, Criticise Confucius" campaign against premier Zhou because Zhou was viewed as one of Jiang's primary political opponents. In 1975, Jiang initiated a campaign named "Criticizing Song Jiang, Evaluating the Water Margin", which encouraged the use of Zhou as an example of a political loser. After Zhou Enlai died in 1976, Jiang initiated the "Five Nos" campaign in order to discourage and prohibit any public mourning for Zhou. When traditional landscape and bird-and-flower paintings re-emerged in the early 1970s, Jiang criticised these traditional forms as "

black paintings",

which in fact targeted Zhou Enlai.

1971–1973

Jiang first collaborated with then second-in-charge Lin Biao, but after Lin Biao's death in 1971, she turned against him publicly in the

Criticise Lin, Criticise Confucius Campaign.

After the

September 13 Incident in 1971, Jiang Qing saw the collapse of the Lin Biao faction and, with Mao Zedong's declining health, she became eager to seize the highest power in the country. In 1972, Jiang Qing enlisted American journalist Roxane Witke to write her autobiography. After 1972, Mao's health deteriorated. Though Mao was largely cut off from the outside world due to his illness, Zhu De sent Mao a letter informing him about Jiang Qing's biography. This revelation deeply angered Mao, who, in a fit of rage, even expressed his desire to expel Jiang Qing from the Politburo and sever their political ties.

By 1973, although unreported due to it being a personal matter, Mao and his wife Jiang had separated.

1973–1976

On 10 March 1973, Deng Xiaoping was reinstated as Vice Premier, serving as Zhou Enlai's deputy. During the 10th National Congress of the CCP, Deng remained a member of the Central Committee but he did not gain a seat on the Politburo. On 10 April 1974, Deng led the Chinese delegation to the

United Nations General Assembly

The United Nations General Assembly (UNGA or GA; , AGNU or AG) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN), serving as its main deliberative, policymaking, and representative organ. Currently in its Seventy-ninth session of th ...

. Although Jiang Qing strongly opposed Deng's appointment, Mao Zedong cautioned her in a letter to cease opposing his decision.

After Zhou Enlai was hospitalised, Wang Hongwen managed the Politburo, Deng Xiaoping oversaw the State Council, and Ye Jianying led the Central Military Commission.

On 4 October 1974, Mao Zedong proposed appointing Deng as First Vice Premier. Sensing that Deng might replace Zhou Enlai at the upcoming Fourth National People's Congress, Jiang Qing attempted to block Deng from taking charge of the State Council and the Party's central operations.

On 12 December, Mao reaffirmed his support for Deng by proposing his appointment as a member of both the Military Commission and the Politburo—a suggestion that gained majority approval from Politburo members.

On 23 December, despite his ill health, Zhou Enlai flew to Changsha to meet Mao and seek his endorsement of Deng Xiaoping, with Wang Hongwen also in attendance. Mao agreed and, while pointing at Wang, remarked that Deng's ''"politics'' is better than his.''"'' Mao spoke English for the word "politics." Wang was embarrassed as he did not understand.

Downfall

Protests

By the mid-1970s, Jiang spearheaded the campaign against

Deng Xiaoping

Deng Xiaoping also Romanization of Chinese, romanised as Teng Hsiao-p'ing; born Xiansheng (). (22 August 190419 February 1997) was a Chinese statesman, revolutionary, and political theorist who served as the paramount leader of the People's R ...

.

Yet, the Chinese public became intensely discontented at politics and chose to blame Jiang, a more accessible and easier target than Mao.

In January 1976, official news announced the death of Zhou Enlai. Zhou was highly respected in Chinese society, second only to Mao Zedong in influence. However, no official commemorative activities were organised following his death. On 5 March and 25 March, ''

Wenhui Daily'' published two reports criticising

Deng Xiaoping

Deng Xiaoping also Romanization of Chinese, romanised as Teng Hsiao-p'ing; born Xiansheng (). (22 August 190419 February 1997) was a Chinese statesman, revolutionary, and political theorist who served as the paramount leader of the People's R ...

, indirectly accusing Zhou Enlai of being the "biggest capitalist roader" who had supported and protected Deng. Starting on 21 March, students at

Nanjing University

Nanjing University (NJU) is a public university in Nanjing, Jiangsu, China. It is affiliated and sponsored by the Ministry of Education. The university is part of Project 211, Project 985, and the Double First-Class Construction. The univers ...

began questioning and condemning ''Wenhui Daily'' and the criticisms of Zhou in Shanghai. On 29 March, the students escalated their protests by writing large slogans on trains departing from Nanjing, spreading their message nationwide. On 30 March, members of the

All-China Federation of Trade Unions

The All-China Federation of Trade Unions (ACFTU) is the national trade union center and people's organization of the China, People's Republic of China. It is the largest trade union in the world with 302 million members in 1,713,000 primary tra ...

, including Cao Zhijie, posted signed wall posters in Beijing. These posters transformed the veiled political dissent into open protest, marking the beginning of the Tiananmen protests in Beijing.

Many Chinese instinctively believe that it was Jiang Qing who ordered the removal of the wreaths dedicated to Zhou Enlai from Tiananmen Square. In response, slogans appeared, such as "Down with the

Empress Dowager

Empress dowager (also dowager empress or empress mother; ) is the English language translation of the title given to the mother or widow of a monarch, especially in regards to Chinese, Japanese, Korean, or Vietnamese monarchs in the Chines ...

, down with

Indira Gandhi

Indira Priyadarshini Gandhi (Given name, ''née'' Nehru; 19 November 1917 – 31 October 1984) was an Indian politician and stateswoman who served as the Prime Minister of India, prime minister of India from 1966 to 1977 and again from 1980 un ...

." Another individual placed a wreath in honour of Mao's revered second wife,

Yang Kaihui, who had been executed by Chiang Kai-shek in 1930. Jiang Qing was often referred to obliquely as "that woman" or "three drops of water," a reference to part of the Chinese character for her name.

The protests eventually evolved into a riot, with cars ignited by angry protesters and militia intervention.

Coup d'état

On 5 September 1976, Jiang Qing was informed of the critical illness of Mao Zedong and soon returned to Beijing. On the evening of 8 September, she drove to

Xinhua News Agency

Xinhua News Agency (English pronunciation: ),J. C. Wells: Longman Pronunciation Dictionary, 3rd ed., for both British and American English or New China News Agency, is the official state news agency of the People's Republic of China. It is a ...

trying to find supporters, and returned to Zhongnanhai late in night, where high-rank Chinese officials and Mao's family members were present. Jiang could not fall asleep. She needed to confront two other factions within the party, Hua Guofeng who had received a note from Mao saying, "

With you in charge, I am at ease," and Deng Xiaoping who was being attacked by Jiang. She approached Hua secretly, proposing to expel Deng in the Politburo meeting before Mao's death, but she did not succeed.

Mao died on 9 September. The funeral services were hosted by Wang Hongwen, with a million people assembled at Tiananmen Square to mourn his death. Jiang sent a large wreath of chrysanthemums and greenery, as his student and comrade, rather than his widow. Hua was the designated successor of Mao and soon became the party chief and became embroiled in a power struggle with the Gang of Four.

Jiang went to Baoding to rally the

38th Army, preparing to replace Hua as a party chief. In response, both Ye Jianying, one of Deng's allies, and Hua mobilised their military forces in Beijing and Guangzhou.

Xu Shiyou warned a north expedition from Guangzhou, if Jiang had not been arrested in Beijing. In 4–5 October, Hua continued to negotiate with Jiang's allies on the personnel arrangement and agreed to continue the talk the following day.

On 6 October, Zhang Chunqiao and Wang Hongwen were arrested when they arrived at Zhongnanhai. Jiang Qing and Yao Wenyuan were arrested at their homes. Hua – supported by the military and state security – had Jiang and the rest of the Gang arrested and removed from their party positions. According to Zhang Yaoci, who carried out the arrest, Jiang did not say much when she was arrested. It was reported that one of her servants spat at her as she was being taken away under a flurry of blows by onlookers and police.

In May 1975, Mao Zedong once criticised the Gang of Four for leaning too heavily on

empiricism

In philosophy, empiricism is an epistemological view which holds that true knowledge or justification comes only or primarily from sensory experience and empirical evidence. It is one of several competing views within epistemology, along ...

. However, he downplayed the severity of their issue, stating that it was not a significant problem but needed to be addressed. Mao remarked,

The remark served as a justification for Hua Guofeng to arrest the Gang of Four.

Televised trial

Hua was later replaced by

Deng Xiaoping

Deng Xiaoping also Romanization of Chinese, romanised as Teng Hsiao-p'ing; born Xiansheng (). (22 August 190419 February 1997) was a Chinese statesman, revolutionary, and political theorist who served as the paramount leader of the People's R ...

, who proceeded with prosecuting Jiang.

At the time of her arrest, the country lacked the proper institutions for a legal trial.

As a result, she and the other members of the Gang of Four were held in a state of limbo for the first six months of their capture.

Following prompt legal modernisation, an indictment was brought forward, formally titled "Indictment of the Special Procuratorate under the

Supreme People's Procuratorate of the People’s Republic of China." The indictment contained 48 separate counts.

In November 1980, the government announced that Jiang and nine others would stand trial.

She was tried with the other three members of the Gang of Four and six associates.

She was accused of persecuting artists during the Cultural Revolution, and authorising the

burgling of the homes of writers and performers in Shanghai to destroy material related to Jiang's early career that could

harm her reputation.

Xinhua News Agency reported that Jiang initially sought to recruit her own lawyers but rejected those recommended by the special team after interviews. Meanwhile, five of the ten defendants agreed to be represented by government-appointed lawyers who would act as their defence counsel.

Jiang was defiant in the court.

She argued to the special prosecution teams that Mao should also be held accountable for her actions.

Whenever a witness took the stand, there was a chance the court proceedings would devolve into a shouting match.

She did not deny the accusations,

and insisted that she had been protecting Mao and following his instructions. Jiang remarked:

Her defence strategy was marked by attempts to transcend the court room and appeal to history and the logic of revolution.

Jiang sought to challenge Hua Guofeng's authority within the Party, with an appalling yet unverifiable claim,

The court announced its verdict after six weeks of testimony and debate and four weeks of deliberations. In early 1981, she was convicted and

sentenced to death with a two-year reprieve. She was assigned the highest level of criminal liability among the defendants as a "ringleader" of a

counterrevolutionary group.

Wu Xiuquan recounted in his memoir that the court room erupted into applause as the verdict was read and Jiang Qing was dragged out of the court room by two female guards while shouting revolutionary slogans.

Death and burial

Internment and illness

Following her arrest, Jiang Qing was held at

Qincheng Prison, where she occupied herself with activities such as reading newspapers, listening to radio broadcasts, watching television, knitting, studying books, and writing. Her daughter, Li Na, visited her

fortnight

A fortnight is a unit of time equal to 14 days (two weeks). The word derives from the Old English term , meaning "" (or "fourteen days", since the Anglo-Saxons counted by nights).

Astronomy and tides

In astronomy, a ''lunar fortnight'' is hal ...

ly.

She was treated well, unlike how she treated her enemies during the Cultural Revolution. The sentence was commuted to life imprisonment in 1983.

The

Supreme People's Court

The Supreme People's Court of the People's Republic of China (SPC) is the highest court of the People's Republic of China. It hears appeals of cases from the high people's courts and is the trial court for cases about matters of national ...

determined that both Jiang and her chief associate, Zhang, had demonstrated "sufficient repentance" during their two-year

reprieve, leading to their death sentences being commuted. However, senior Chinese officials stated that Jiang has not shown genuine remorse and remains as defiant as the day she was removed from a crowded courtroom, shouting, "Long Live the Revolution."

In 1984, Jiang was granted medical parole and relocated to a discreet residence arranged by the authorities. In December 1988, on the occasion of Mao Zedong's 95th birth anniversary, Jiang requested approval to hold a family gathering, but her petition was denied. Distressed, she attempted suicide by ingesting 50

sleeping pills she had secretly saved. The attempt failed. She was later sent back to Qincheng Prison in 1989 when her

medical parole concluded.

Jiang Qing believed that

Deng Xiaoping

Deng Xiaoping also Romanization of Chinese, romanised as Teng Hsiao-p'ing; born Xiansheng (). (22 August 190419 February 1997) was a Chinese statesman, revolutionary, and political theorist who served as the paramount leader of the People's R ...

should be held responsible for the

student movement (better known as the Tiananmen Square protests), as he tolerated Western ideologies. She also condemned the subsequent massacre that followed the protests, emphasising that Mao Zedong had never ordered the army to massacre crowds. While in custody, Jiang was diagnosed with

throat cancer, and doctors advised surgery. She refused, asserting that losing her voice was unacceptable.

Suicide

On 15 March 1991, Jiang Qing was transferred to the

Beijing Police Hospital from her residence at Jiuxianqiao due to a high fever. By 18 March, her fever had subsided. She was then moved to a ward within the hospital compound, which included a bedroom, bathroom, and living room. On 10 May 1991, she tore apart her memoir manuscript in front of others and expressed a wish to return to her home. Two days later, on 12 May, her daughter and son-in-law came to visit her in the hospital after learning about her condition, but Jiang declined to meet them. On 14 May 1991, Jiang Qing committed suicide. At 3:30 a.m., a nurse entered her room and found her hanging above the bathtub, having died. The

suicide note

A suicide note or death note is a message written by a person who intends to die by suicide.

A study examining Japanese suicide notes estimated that 25–30% of suicides are accompanied by a note. However, incidence rates may depend on ethnic ...

read,

That afternoon, Li Na, went to the hospital to sign the death certificate and agreed that no funeral or memorial service would be held. On 18 May, Jiang Qing's remains were cremated. Neither Li Na nor any of Jiang Qing's other relatives attended the cremation. Jiang Qing's ashes were entrusted to Li Na, who kept them at her home. The Chinese government confirmed that she had hanged herself on 4 June, withholding the announcement for two weeks to avoid its impact before the second anniversary of the

1989 Tiananmen protests.

However, He Diankui, a former staff of Qincheng Prison, later claimed that "Jiang Qing never left Qincheng Prison until her death." He suggested that she died in the prison from taking sleeping pills, which refuted the official report regarding her death.

Burial

While imprisoned, Jiang Qing expressed in her will a desire to be buried in her hometown of

Zhucheng, Shandong. In 1996, Yan Changgui, Jiang Qing's former secretary, visited Zhucheng, where the city's Party Secretary asked him to convey to Li Na that Jiang Qing could be buried there, pending her consent. However, after the

16th National Congress of the CCP,

Jiang Zemin

Jiang Zemin (17 August 1926 – 30 November 2022) was a Chinese politician who served as General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party, general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) from 1989 to 2002, as Chairman of the Central Mil ...

suggested to Li Na that Zhucheng might not be a secure burial site. Instead, Li Na inquired about the possibility of burial in Beijing, which Jiang Zemin approved. Li Na arranged the burial at her own expense. In March 2002, Jiang Qing's ashes were interred at the

Futian Cemetery in Beijing's

Western Hills scenic area. The tombstone reads: "The Grave of Mother Li Yunhe, 1914–1991, respectfully erected by

her daughter, son-in-law, and grandson."

Legacy

Public image

Jiang Qing was never a widely admired figure throughout her life. Her marriage to Mao in the 1930s scandalised many of the more puritanical comrades in Yan'an. During the Cultural Revolution, she did little to win the favour of other Chinese leaders.

Jiang Qing is often viewed as a figure of naked ambition, with many perceiving her as a typical power-hungry wife of an emperor, seeking to secure power for herself through questionable means. Her public image is largely shaped by her self-serving narrative, which portrays her as a central figure in the turbulent and cutthroat environment of Chinese leadership. She is seen as embodying the ruthless, unpredictable, and dangerous nature of life at the top. Her long-standing vendetta against former cultural-political rivals from her acting days in Shanghai has fueled her reputation for vindictiveness. Though she framed her conflicts with these men as ideological battles, it is widely believed that personal grudges and animosities were the true driving forces behind her actions.

According to Roxane Witke, Jiang's early life was marked by poverty, hunger, and violence, and later, as a woman in a male-dominated world, she faced numerous challenges. These experiences shaped her defensive and aggressive personality, fostering an opportunism that persisted even when she no longer needed to assert herself.

Jiang's televised trials and her defiance in court have softened hatred towards her among the younger generations, who became sceptical of China's Communist system.

Official historiography

After Jiang Qing's arrest in 1976, the Chinese government launched a massive propaganda campaign to vilify her and the other members of the so-called Gang of Four. Orchestrated under the authoritarian political culture of Mao's successor Hua Guofeng, this campaign aimed to discredit Jiang and her associates entirely. In the years leading to her trial in 1980, millions of posters and cartoons depicted the Gang of Four as class enemies and spies. Jiang herself became the primary target of ridicule, portrayed as an empress scheming to succeed Mao and as a prostitute, with references to her past as a Shanghai actress used to question her moral integrity. The propaganda also criticised her interest in Western pastimes, such as photography and poker, portraying them as evidence of her lack of communist values. Ultimately, she was branded the "white-boned demon," a gendered caricature symbolising destruction and chaos.

The 1980 Gang of Four trial solidified Jiang's image as a manipulative and villainous figure. The indictment held the Gang responsible for the violence of the Cultural Revolution, accusing Jiang of using political purges for personal vendettas and fostering large-scale chaos. Widely broadcast both within and outside China, the trial reinforced a clear dichotomy: Jiang as a symbol of the past's chaos, and Deng Xiaoping's administration as the harbinger of order and progress. This narrative was consistent with the CCP's

Resolution on History, which sought to redefine Mao Zedong's legacy. While Mao was criticised for "errors," he was not held directly accountable for the excesses of the Cultural Revolution. Instead, full blame was shifted to Jiang and the Gang of Four, allowing Mao Zedong Thought to remain ideologically valid under Deng's reforms.

Alternative views

Biographical literature on Jiang Qing has emerged as a tool to critique and reinterpret official Chinese historiography. These works challenge the one-dimensional vilification of Jiang, contributing to broader historical debates about the Cultural Revolution and its impact on shaping modern China. While factual biographies aim to deliver an accurate portrayal of their subject, fictional works take creative liberties, reimagining the life of a historical figure without strict adherence to facts. By rejecting the traditional authoritative biographical model—which presents a subject's life as a coherent narrative—works such as ''Jiang Qing and Her Husbands'' and ''Becoming Madame Mao'' instead question the validity of totalising narratives about Jiang. Ultimately, the private sphere in these narratives is used not to provide more intimate insights into the subject but as a means to deconstruct and challenge official Chinese historiography.

Comparisons

The 2013 trial of

Bo Xilai was regarded as the most dramatic courtroom event in China since Jiang Qing's trial in 1980. Bo's wife,

Gu Kailai, was frequently likened to Jiang Qing due to the nature of her crimes. In 2024, ''

Yomiuri Shimbun

The is a Japanese newspaper published in Tokyo, Osaka, Fukuoka, Fukuoka, Fukuoka, and other major Japanese cities. It is one of the five major newspapers in Japan; the other four are ''The Asahi Shimbun'', the ''Chunichi Shimbun'', the ''Ma ...

'' reported on

Peng Liyuan's influence over key personnel decisions within the CCP. The report highlighted her backing of

Dong Jun's appointment as Minister of Defence and

Li Ganjie's selection as head of the

CCP Organisation Department. Dong and Li were both from Shandong, where Peng was born. The report drew parallels between Xi Jinping's leadership in his later years and Mao Zedong's, likening Peng to Jiang Qing.

Memorials

Jiang Qing's grave remained undisclosed to the public until early 2009.

Each year during the

Tomb-Sweeping Festival, flower baskets are placed at Jiang's tomb. In 2015, leftist activists attempting to pay their respects faced resistance from dozens of security guards, with several taken to

Pingguoyuan Police Station for questioning. Frustrated

Maoist

Maoism, officially Mao Zedong Thought, is a variety of Marxism–Leninism that Mao Zedong developed while trying to realize a socialist revolution in the agricultural, pre-industrial society of the Republic of China (1912–1949), Republic o ...

supporters questioned why publicly honouring

Chiang Kai-shek was permitted while commemorating Jiang Qing was not, rhetorically asking if the

Republic of China

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia. The main geography of Taiwan, island of Taiwan, also known as ''Formosa'', lies between the East China Sea, East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocea ...

had somehow

reclaimed the mainland. Since 2018, such commemorations have proceeded without police interference. On 14 May 2021,

leftist activists held a panel discussion on "the Role of

Li Jin in the